Introduction

Languages and dialects distributed across Iran have been the subject of interest and study for at least seventy years. Linguists have not taken on many of the older works. Instead, they were performed by anthropologists, folklore scholars and also literary figures with the intention of preserving proverbs or folk vocabulary; and they were not conducted using standard documentation methods. The 1960s should be considered as the beginning of the more serious activities in the field of dialectology in Iran. In 1961, with the help of George Redard, Ehsān Yāršāter founded Iran’s first Linguistic Atlas, but unfortunately it folded after five years.Footnote 1 At the present time, several activities have been devised to systematically gather the languages and dialects of Iran and produce Iranian language atlases, each of which is valuable in its own right.

The Iran Linguistic Atlas (the subject of this article) dates back to June 1974, when, in the form of a joint project by the then Iranian Academy of LanguageFootnote 2 (also known as the Second Academy) and the National Geography Organization, the documentation of the language varieties of all Iran’s villages started, based on the then universally accepted and attested standards.Footnote 3 The project was named “Farhangsāz,” a blend of the Persian names of the two organizations, namely “farhangestān-e zabān-e Ῑrān” and “sāzmān-e ǧog˚rāfī-ye kešvar,” roughly interpreted as “culture-propagator.”Footnote 4 The project aimed at recording the usage of words, phrases and sentences of every regional dialect spoken in rural areas of Iran. It followed roughly simultaneous data-gathering (on the field) and transcription of the audiotapes (at the headquarters).

The primary goal of “Farhangsāz” was to identify and record the language varieties of Iran’s rural areas. “Farhangsāz” remained active till October 1978,Footnote 5 and was stopped because of the social developments of the year in Iran. Before being suspended, the project had had a successful output of documenting the languages and dialects of around 14,000 of Iran’s villages,Footnote 6 including much of Iran’s eastern provinces. A good deal of what we know about the language diversity in Iran’s rural areas around the 1970s and the overall characteristics of the languages and dialects scattered around those areas comes from Farhangsāz and its valuable recorded interviews. Amazingly, all these interviews have been preserved; the tapes have not been recorded over.

All the recorded interviews along with the information booklets which were provided for each language variety in the field concerning the socio-geographical information about the village (discussed below) were handed over to several organizations and finally to the Cultural Heritage Organization in 2001. Since 2007, the Research Institute for Cultural Heritage and Tourism (RICHT) affiliated to the organization is authorized to take responsibility. The principal goal of the contemporary languages and dialects department of the Research Institute for Cultural Heritage and Tourism is the study of language and dialect varieties of Iran, including all the non-standard and regional varieties spread all over the country. Therefore, the Iran Linguistic Atlas, which should be considered as a continuing and modern phase of “Farhangsāz,” is the most important ongoing project of the institute to fulfill this goal.

“Farhangsāz” Project: The ILA’s Predecessor

In the early 1970s, Dr. Ṣādeq Kīyā, the then head of the Iranian Academy of Language, signed a contract with the National Geography Organization, according to which linguistically trained people would be dispatched to villages along with the National Geography mapping group, to gather Iran’s rural dialects.Footnote 7 The project was entitled “Farhangsāz.” Farhangsāz (June 1974–October 1978) was designed to fulfill some prominent goals, including:

- identifying the language varieties of Iran;

- preparing the Linguistic Atlas of Iran;

- finding the number of languages and dialects which are spoken within Iran’s political borders;Footnote 8

- measuring Iran’s languages and dialects’ relations in terms of mutual intelligibility.Footnote 9

It is worth mentioning here that the aims of Farhangsāz are merely stated based on what has been said in the mentioned references, and it is not clear to the present author why some of these goals should be included, and other important goals such as documentation and analysis of actual linguistic structures were excluded and had not been considered.

To achieve the mentioned goals, a section for “Dialectological Studies” was founded at the Iranian Academy of Language. The section established the criteria required and prepared the guidelines for the project.Footnote 10 Soon after, responsibility for the “Dialectological Studies” section was given to Dr. Yadollāh ![]() amareh. Conducting the field work, training the staff, and proposing the tools needed for accomplishing the project were done under his direction. Thirty young people, fifteen females and fifteen males, with at least a Bachelor of Arts degree were employed to carry out the work. They were all instructed in phonetics, working with tape-recorder and aural training; and men were also instructed for field work, selecting appropriate informants and working with them. These preliminaries lasted until February 1974, and the trained young men were dispatched to the villages a few months later.Footnote 11

amareh. Conducting the field work, training the staff, and proposing the tools needed for accomplishing the project were done under his direction. Thirty young people, fifteen females and fifteen males, with at least a Bachelor of Arts degree were employed to carry out the work. They were all instructed in phonetics, working with tape-recorder and aural training; and men were also instructed for field work, selecting appropriate informants and working with them. These preliminaries lasted until February 1974, and the trained young men were dispatched to the villages a few months later.Footnote 11

At first steps, the “Dialectological Studies” section compiled a questionnaire for systematically documenting the general features of languages and dialects of every village in Iran with ten or more households. The questionnaire was based on a book written by Dr. Ṣādeq Kīyā entitled A Guide to Documenting Dialects and was designed to elicit variation in vocabulary, pronunciation, and some grammatical points like verb forms, choices of prepositions and word order. Kīyā pointed out that he had tried to include in the questionnaire the words he thought all Iranian speakers knew and the sentences needed to examine various points of Iranian grammar. According to him, studying dialectal words and sentences could help to measure and classify Iranian dialects.Footnote 12 The questionnaire consisted of two separate parts: the first part was entitled ‘Āgāhīhā-ye guyešī” (Dialectal information), including some questions about geographical location and prosperity of the village and the language(s) or dialect(s) spoken there. The other part of the questionnaire concerned the actual words, phrases and sentences. The two parts will be introduced in detail later (see below).

The interviews were conducted with preferably older, uneducated male or female speakers of dialects in rural areas and the questionnaire was in Persian. Villages were chosen only concerning the number of households. In other words, the lower limit of the speech community was determined as a village having at least ten households. The “Field Group,” or “goruh-e ṣaḥrā” as they were called, were obliged to select one appropriate speaker in each village for each language variety as a representative of the community, usually because of lifelong residence there. Then they put the first part of the questionnaire to the chosen informant and wrote the responses down in the separate booklet, on which the name of the village, its geographical divisions, geographic coordinate, the language variety, the name of the interviewee, the date and some other relevant information had been written. After this session, the fieldworker explained the process to the informant, obtained their consent orally and turned on the recorder. The informant was asked to say the equivalent of each item in the dialect twice after the fieldworker had said it in Persian. After finishing the questionnaire’s items, the informant was asked to narrate a story, a memory or anything else in their language, if they wanted. The whole session was recorded on one side of a Sony tape and the village name and other distinguishing information (the same as the corresponding booklet) were written down on the label. The rest of the tape was left empty.

The field group then sent the recorded tapes (two interviews on each) and the corresponding booklets to the Iranian Academy of Language. Because of some problems the field group had had in registering the recorded tapes, the responsibility had been given to the “Transcription group” (“goruh-e āvānevīsī”), the members of which had been trained for this purpose. They also were responsible for providing a standard written record of the recorded interviews. The “Control group” (“goruh-e vārasī”) was another group in the structure of the section, with responsibility for ensuring the recorded materials were correct.Footnote 13 We only know the names of these two groups. No further information on them, concerning the number of people in each and the level of their education, has been mentioned in the sources. No map-making team was introduced since the data-gathering phase had not been completed.

“Farhangsāz” followed the descriptive tradition and was carried out within the context of dialectical geography (traditional dialectology), which is a systematic study of linguistic varieties spread around geographic areas and focuses on the variations in formal, semantic or pronunciation from region to region. In this approach, what was at stake was merely the distribution of population dots across a geographical area, and no distinction was made between the town and the village. Thus, in urban areas, as in rural areas, only one linguistic interview was recorded. Therefore, one could expect that at this stage the considerations and methods of urban dialectology had not been followed.

The successful beginning of “Farhangsāz” has led to coverage of several villages in large areas of Iran using the defined survey methods and guidelines (Table 1). The survey had been completed in the eastern provinces, including Ḫorāsān (nowadays divided into three provinces) and Sīstān va Balučestān. The project was stopped before completion because of the social developments in Iran in the year 1979. Until October of that year, 14,000 recorded interviews along with their information booklets were gathered from Iran’s villages and sent to the Iranian Academy of Language. Besides these, more than 2,000 information booklets were filled in the villages and sent to the Academy, but not accompanied by recorded interviews because of some problems regarding finding appropriate informants.Footnote 14

Table 1. Information regarding surveys done by Farhangsāz (1974–78)

1. The names of the cities in each province: Esfahān: Ardestān, Esfahān, Ḫānsār, Semīrom, Šahreżā, Faridan, Fereydūnšahr, Falāvarğān, Kāšān, Golpāyegān, Lenğān, Nāyīn, Naṭanz, Nağafābād; Īlām: Īlām, Dehlorān, Mehrān, Badreh; Būšehr: Daštestān, Būšehr, Borāzğān; Čahārmaḥāl va baḫtiyārī: Šahrekord, Borūğen; Ḫorāsān: Esfarāyen, Boğnord, Baḫzar, Birğand, Tāybād, Torbat-e ğām, Torbat-e ḥeydariyeh, Sabzevār, Kāšmar, Gonābād, Mašhad, Neyšābūr, Qūčān; Ḫūzestān: Ahvāz, Abādān, Ḫoramšahr, Dezfūl, Sūsangerd, Dašt-e šīyān, Rāmhormoz, Māhšahr Masğed soleymān, Šūštar; Semnān: Semnān, Šāhrūd, Dāmqān; Sīstān va Balučestān: Īrānšahr, Saravān, Čābahār, zābol, Ḫāš, zāhedān; Fārs: Ğahrom, Šīrāz, Ābādeh, Kāzerūn, Nūrābd, Neyrīz, Fīrūzābād, Rafsanğān, Marvdašt, Estahbānāt, Amasani, Fasā, Taft, Borāzğān, Ḫarāmeh; Kordestān: Sanandağ, Qorveh; Kermān: Ğīroft, Bam, Sabzevārān, Rafsanğān, Bāft, Zarand, Sīrğān, Kermān; Kermānšāh: Kermānšāh, Šāhābād-e qarb, Pāveh, Qasr-e Šīrīn, Sanqar; Lorestān: Ḫorramābād; Markazī: Qom, Maḥallāt; Hormozgān: Mīnāb; Hamedān: Hamedān, Nahāvand; Yazd: Ardakān, Taft, Bāfq, Yazd.

2. In the case of Esfahān province, the numbers show the sum of what was done during 1974–79 and also during 1988–89.

Farhangsāz’s surveys were conducted in seventeen provinces. Table 1 shows the names of provinces, the number of cities and villages covered in each, the number of information booklets, tapes, and interviews that exist in our physical database. It should be noted that according to the defined survey methods, the name of the language variety in each linguistic community was recorded on the basis of the informant’s self-expression, so the number indicated in the last column of the table roughly shows how the people in each province believed their language/dialect was distinguished from the other languages/dialects of other villages in the province or as a whole. Table 2 shows the expressed names for language varieties in each city within Eṣfahān province, as an example.

Table 2. Province, cities, names of language varieties and the number of villages covered

1 Two or three names separated by a dash indicates bilingual or trilingual villages.

Figure 1 shows the coverage of Iran’s provinces by Farhangsāz. It should be noted that in this figure and other following figures, map templates have been provided by © d-maps.com and completed by this author unless otherwise stated.

Figure 1. Coverage of Iran’s provinces by Farhangsāz.

Note: Yellow-colored areas had been surveyed, but not completely; purple-colored areas had been surveyed completely. Colour online.

The Questionnaire: Dialectal Information and Linguistic Data

As mentioned above, at the first steps of the Farhangsāz project, a questionnaire was compiled for systematically documenting the general features of languages and dialects of Iran. It is still respected in the new phases of the project. The questionnaire consists of two parts, Dialectal Information, and Linguistic Data. The original form of the questionnaire was in Persian and its English translation is presented here.Footnote 15

Dialectal Information

I. About the village

(1) Village name:

(2) Village’s natural situation:

(3) Roads passing through the village:

(4) Distance to the nearest road … … … … . kilometers

(5) Distance to the nearest village … … … … . kilometers

(6) Do vehicles come inside the village? Yes □ No □

(7) What communication is there between the village and the district?

II. Lifestyle

(1) People’s main occupation:

(2) People’s religion: … … … … . People’s sect: … … … … .

(3) Names of the village’s tribes

- Local tribes

- Immigrant tribes

(4) Are people in the village aboriginal? All □ Some □ None □

(5) Has there been emigration in the village? Yes □ No □

(6) Do villagers go outside the village for work? Yes □ No □

- If yes, where do they usually go?

- How many people or households work outside the village?

- In what season do they work outside the village? Spring □ Summer □ Autumn □ Winter □

Do these people stay where they are working? Yes □ No □

- Why do the villagers go out of the village?

- The name of the city or cities which the villagers go to most often:

III. The Dialect:

(1) The name of the village’s dialect(s):

(2) The date of the interview:

(3) The name of the village’s neighborhood:

(4) Location of the interview:

(5) Is the dialect of all the village’s neighborhood the same? Yes □ No □

(6) Which village’s neighborhood has a special dialect?

(7) In which neighborhood, lifestyle, and language is older?

(8) Do you know other villages that speak the same dialect as yours? Yes □ No □

- If yes, name them:

(9) Do neighboring villages speak different dialects?

- If yes, what are their names and their dialects?

(10) Have the village’s elderly people used different dialects in the past? Yes □ No □

- If yes, is there anybody who knows the language?

(11) Do certain groups of people (like gypsies) come to the village for a short stay? Yes □ No □

- If yes, what is the name of their group?

(12) Do the villagers sometimes speak another dialect not understood by others? Yes □ No □

- If yes, what is the name of the dialect?

(13) Do the villagers know special jargon? Yes □ No □

- If yes, do they use it?

- If yes, what is its name?

(14) Do the teenagers of the village know the village’s dialect? Yes □ No □

- If yes, to what extent can they speak the dialect? Little □ Moderately □ Well □

(15) Do the villagers understand the Persian language used on Iranian radio? All □ Some □ None □

(16) Can the villagers speak Persian? All □ Some □ None □

(17) Do the village’s teenagers understand Persian better than adults?

- If yes, can they also speak Persian better?

(18) How many dialects do the villagers understand?

(19) How many dialects are used in this village?

(20) What is the number of the population/households of each dialect?

(21) How many people are literate in this village?

(22) Which mass media are available to the villagers?

Radio □ Television □ Cinema □ Newspaper □ Book □ Others □

(23) Does the village have educational institutions? Mark it.

Old-fashioned school (maktabḫāneh) □ Sepāh-e dāneš elementary school □ Nomad elementary school □ Junior school □ High school □ Others □

(24) Is the passion play (taʾziyeh) or narrating of the tragedies of Karbalā (rozehḫānĪ) customary in this village? Yes □ No □

- If yes, in which language/dialect are they performed?

(25) Has anything been written in the village’s language/dialect?

- If yes, what are these written texts?

(26) Has another language/dialect been in use in this village in the past? Yes □ No □

- If yes, in which language/dialect?

- If yes, why and when was it forgotten?

IV. The informant

(1) Name:

(2) Family name:

(3) Occupation:

(4) The language(s)/dialect(s) he/she knows:

(5) Literacy rate:

(6) How many times and how long was he/she away from the village?

Linguistic Data

Resumption of Farhangsāz in the Cultural Heritage Organization: The Iran Linguistic Atlas

Three years after the suspension of Farhangsāz, all the recorded data, the information booklets and some equipment of the Dialectological Studies section were moved to the “Iranian Anthropology Center” (Markaz-e mardomšenāsī-ye Īrān) upon the approval of the academy. In 1988, after the foundation of the Cultural Heritage Organization, the Iranian Anthropology Center was merged into the organization and all the documented data and materials were delivered to it. The Cultural Heritage Organization accepted “The Identification of Iran’s Dialects” as one of its research programs and limited data gathering was carried out in Esfahān province (1988–89) to continue what had been done in that region. The results of research in Esfahān province was published in three books by the Cultural Heritage Organization in 1983, 1988 and 1995.Footnote 17 A few years after that, the project had not been followed up effectively.

In 2001, when the Languages and Dialects Research Center (Today: Linguistics, Inscriptions and Texts Research Center) was formed within the structure of the Cultural Heritage Organization, the Contemporary Languages and Dialects department affiliated to the center was given responsibility and all the documented materials were delivered to it. It was decided that the Farhangsāz project, with necessary adjustments (which will be discussed below), would be continued.

In 2007, the Research Institute for Cultural Heritage and Tourism as a research institute for the Cultural Heritage Organization was founded, and since then the department and research center with the same responsibility have been affiliated to it.

The efforts which have been made in the Cultural Heritage Organization—and from 2007 to the present in the Research Institute for Cultural Heritage and Tourism—for continuing the Farhangsāz Project, should be divided into two phases.

Phase 1 (2001–7). In 2001, a new and effective phase for continuing the Farhangsāz Project was defined in the Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran. At the outset, the goals of the previous project were revised, some unattainable goals (such as “Measuring Iran’s languages and dialects’ relations in terms of mutual intelligibility”) were set aside, and new goals were defined for the research. This phase guided the efforts to fulfill these goals:

- Preservation of the original 14,000 valuable interviews and written information about Iran’s linguistic diversity.

- Documentation of the regions not covered by Farhangsāz.

- Compiling a digital linguistic atlas of Iran.

- Benefiting from new achievements in computer technology for displaying the language variations and linguistic distributions by creating self-organizing colored maps.

In spite of the challenges, with a long gap between Farhangsāz as an initial phase of the project and the new phase, the project was revived under the title “Tarh-e Atlas-e zabāni-ye Īrān” (the Iran Linguistic Atlas Project) and my now retired colleague, Dr. Yadollāh Parmūn, was selected to make the necessary adjustments to render the old data usable in the new phase. This was done and the utilization of new technologies was foreseen. The earlier project was assigned the status of an initial step to be amended in future developments. Farhangsāz was equipped with the new theoretical, methodological and technological features which Parmūn listed.Footnote 18 To mention a few:

- digitizing previously gathered magnetic data;

- gathering new digital data;

- utilizing modern documentation techniques, informant selection, interviews, and data registration;Footnote 19

- paying special attention to the unique and/or endangered varieties, and planning for plenty of comprehensive data-gathering programs about them;

- encouraging new surveys on previously documented points, regarding population and language consideration.

To guarantee the uniformity of the whole project, some procedures and approaches continued to be followed, among those are:Footnote 20

- The original definition speech community (villages with at least ten households).

- The original executive measure of recording one interview per linguistic variety in each village.

- The original strategy for conducting the project solely in villages, postponing the modern “urban” consideration for future extensions.

- The original method of data gathering based on the old questionnaires.

So, in Phase 1, new documentation projects were followed using modern equipment, but following the same guidelines to guarantee the uniformity of the whole project. It was decided that the field workers employ the same questionnaire to prepare the relevant and comparable data from the remaining parts of Iran. Meanwhile, the old data available on magnetic tapes were sent to be digitized.

In this phase, the project began to acquire interviews from the provinces, as shown in Figure 2, although except for Kermān, none of them had been completed.

Figure 2. Data gathering in Phase 1.

Note: Data gathering was carried out the orange-colored provinces; in Kermān it has been completed. Colour online.

In Phase 1, the initial software program for the ILA had been developed by Hamīdreżā Šahrābī using Microsoft Access with the aim of utilizing computer technology in the project. After being tested for a small portion of the data, it paved the way for improving the software program. The first version of presently available software was composed by ḫane-ye tarrāhan’s software engineers, based on the original algorithm by Hamīdreżā Šahrābī.Footnote 21 It programmed in C # for windows and SQL Server 2008 database. As expected, the software functioned as a medium, translating the database into a graphic representation on different map sheets. The drastic change, from this point of view, was a redefinition of a linguistic atlas as dynamic software of infinite outcome per the operator’s preferences.

The software was compatible with the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) for transcribing the audio files, so a team—consisting of 15 members—of trained, competent linguists with an MA or PhD in linguistics began to transcribe the recorded interviews in the software. The transcribed data, after being controlled by the scientific director of the project, could be used by the software to produce automatic colored display linguistic maps according to the operator’s choices. About 5,000 interviews were transcribed in Phase 2, paving the way to produce a dynamic Linguistic Atlas of Iran.

Again, some changes in the structure of the Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran led the project to be suspended for more than eight years.

Phase 2 (2015 to the present). In 2015 the new phase of the Iran Linguistic Atlas began in RICHT under the present author’s direction.

In the current phase, referred to as Phase 2, we still face the challenge of preservation and display of massive amounts of survey data, gathered mainly in Farhangsāz and partly in Phase 1. We are also interested in fieldwork for the completion of the data gathering in the whole of Iran, using the same questionnaire and taking advantage of the baseline set by the earlier phases to ensure the uniformity of the project as a whole; and we also wish to carry out additional fieldwork in order to gather more linguistic data for each regional dialect. ILA’s software program has recently been updated and rewritten. It has been programmed in C# language for ASP.NET MVC, using SQL Server 2014 database to be a dynamic and interactive web-based software.

Here, the nature of the Iran Linguistic Atlas data, and the recent field methods; Iran Linguistic Atlas databases and Iran Linguistic Atlas software will be explained.

Recent Field Methods

In spite of all the developments which have occurred in dialectology, data gathering methods and language documentation in the last forty-five years—and that we are aware of—we decided to continue using the same questionnaire and the same basic guidelines in order to retain comparability with the older materials and not to lose the valuable data gathered in Farhangsāz and ILA’s Phase 1. We are aware that this questionnaire does not provide all the linguistic items required for a complete linguistic analysis, especially a typological one, but using it will ensure the uniformity of the project and will help us to sketch general characteristics of every spoken dialect of Iran in the same way. The questionnaire contains a set of words, phrases and example sentences of Persian language as the lingua franca to be asked one by one by the interviewer and translated into the target language by the interviewee; but in order to be less direct, and to reduce the formality of the interview, the fieldworkers try some innovative methods such as questioning the informant in a group of their family or friends so the outcome should be more normal and the effects of translation reduced.

To reduce the disadvantages of applying the old questionnaire, in the current phase it was decided to complete the gathered linguistic information by recording free speech in “every” village. Recording free speech had rarely been done previously in Farhangsāz and in Phase 1, whenever—after recording the questionnaire—the informant was eager to say or narrate something, that was welcomed. But today it is necessary to allow for better elicitation and to improve the chances of completing the survey. After recording the items on the questionnaire, the interviewer encourages the informant to talk about different aspects of daily life, food, weather, family and special customs of the village or to narrate a short story or a personal reminiscence.

All the interview session including the questionnaire and free speech are now digitally recorded. More recently, videos are also recorded in each village to capture social events and daily conversations. Although the software program of the ILA is not yet able to upload and analyze the audio- and video-recorded free speech, it was decided to gather more relevant data in each village. These data are saved in the database, waiting for the next update of the software program to be transcribed and analyzed. Figure 3 shows the data-gathering status in the current phase (ILA’s Phase 2).

Figure 3. Data-gathering underway (purple) and negotiated to begin (grey).

Note: Colour online.

Databases

The physical documents of the earlier recordings, including information booklets from each village provided by field workers, the transcriptions from audiotapes for a very small portion of the early interviews, as well as the corresponding audio tapes (14,000 interviews 1974–79 and some from Phase 1, before using digital-recorders) are held at the Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism library and documentation center. All the tape recordings from the early phases of the project have been preserved.

In the new phase, we began to create a digital audio archive, which offers a better chance for preservation through the retention of multiple copies stored on hard disc, and recently a database server was created in the Research Institute for Cultural Heritage and Tourism for this purpose.

The digitized files of all the old linguistic interviews along with recently digitally recorded interviews (approximately 11,000 interviews) are held in this archive in the Contemporary Languages and Dialects department of RICHT and also in the RICHT database server, and the ongoing ILA interviews will be added to both. The audio files are gradually uploaded to the Iran Linguistic Atlas system to be placed at each corresponding village location. All the information booklets corresponding to the interviews which specify metadata for each interview including biographical data about the informant, date of the interview, location of the interview, the name of the interviewer, the name of the dialect as the informant called it, along with other information (see questionnaire) have already been uploaded to the system.

A database of transcribed audio interviews is also being prepared to be utilized by the Atlas software program. All the transcriptions are being done by keyboarding, in the form of narrow transcriptions and directly to the computer by linguists who have been trained for this purpose. An updated procedure for transcription, to be executed by teams of trained competent linguists, was compiled in Phase 1 and is still respected and followed. According to this procedure, extract place and manner of articulation of consonants as well as extract vowel quality should be determined in the transcriptions.

Furthermore, some pronunciation details including aspiration, devoicing nasalization, labialization, incomplete articulation (including nasal release and lateral release) and vowel stress should be marked in the transcription using the correct diacritic in each case. In addition, it has been prescribed that transcriptions of compound words should also be decomposed into their composing morphemes by using a “plus” sign.Footnote 22 More than 7,000 interviews have been transcribed and uploaded to the system.

In the current phase, we decided to prepare the IPA transcriptions database for each province separately. So, each provincial project of the ILA is autonomous, while there is a central editorial and guiding resource at the Contemporary Languages and Dialects department of the Research Institute for Cultural Heritage and Tourism. From each province one or two preferably linguist representatives have been introduced as ILA members and have been trained to participate in a three-day workshop organized at the beginning of the new phase by RICHT. In every province which is now active in transcribing the audio interviews, a team consisting of two to five linguists has been formed for transcribing the data under the supervision of the faculty members of the Contemporary Languages and Dialects department and the scientific director of the ILA. Figure 4 shows the status of the provincial databases of phonetic transcriptions in the current phase.

Figure 4. Provincial databases in preparation (green).

Note: Colour online.

The status of Iran Linguistic Atlas databases on the hard disk and the server is shown in Table 3. Production of the databases is in progress.

Table 3. Status of Iran Linguistic Atlas databases on the hard disk and server

Analysis

The primary goal of the earlier phases of the Iran Linguistic Atlas was to prepare isoglossic and symbolic maps of Iran. More recently, we have been trying to subject the Atlas data to an appropriate software program to create self-organizing colored linguistic maps and to reveal basic distributional principles of language variation in geographical space. These maps and their characteristics are explained in the software session. Besides, based on the information acquired from data-gathering, maps of linguistic diversity can be drawn. Two samples of maps showing the geographic distribution of Iran linguistic varieties are presented. Figure 5 shows the distribution of linguistic varieties in Loretān province’s rural areas,Footnote 23 and Figure 6 shows the same information for southern parts of Ḫorāsān province.Footnote 24 In these maps, each dot represents one village. As noted earlier, the names of the language varieties represented here are based on informants’ self-expression.

Figure 5. Geographic distribution of linguistic varieties in Loretān province.

Source: Based on ILA’s data-gathering.

Figure 6. Geographic distribution of linguistic varieties in southern parts of Ḫorāsān province.

Source: Based on Farhangsāz data-gathering (1974–78).

The Software Program of the ILA

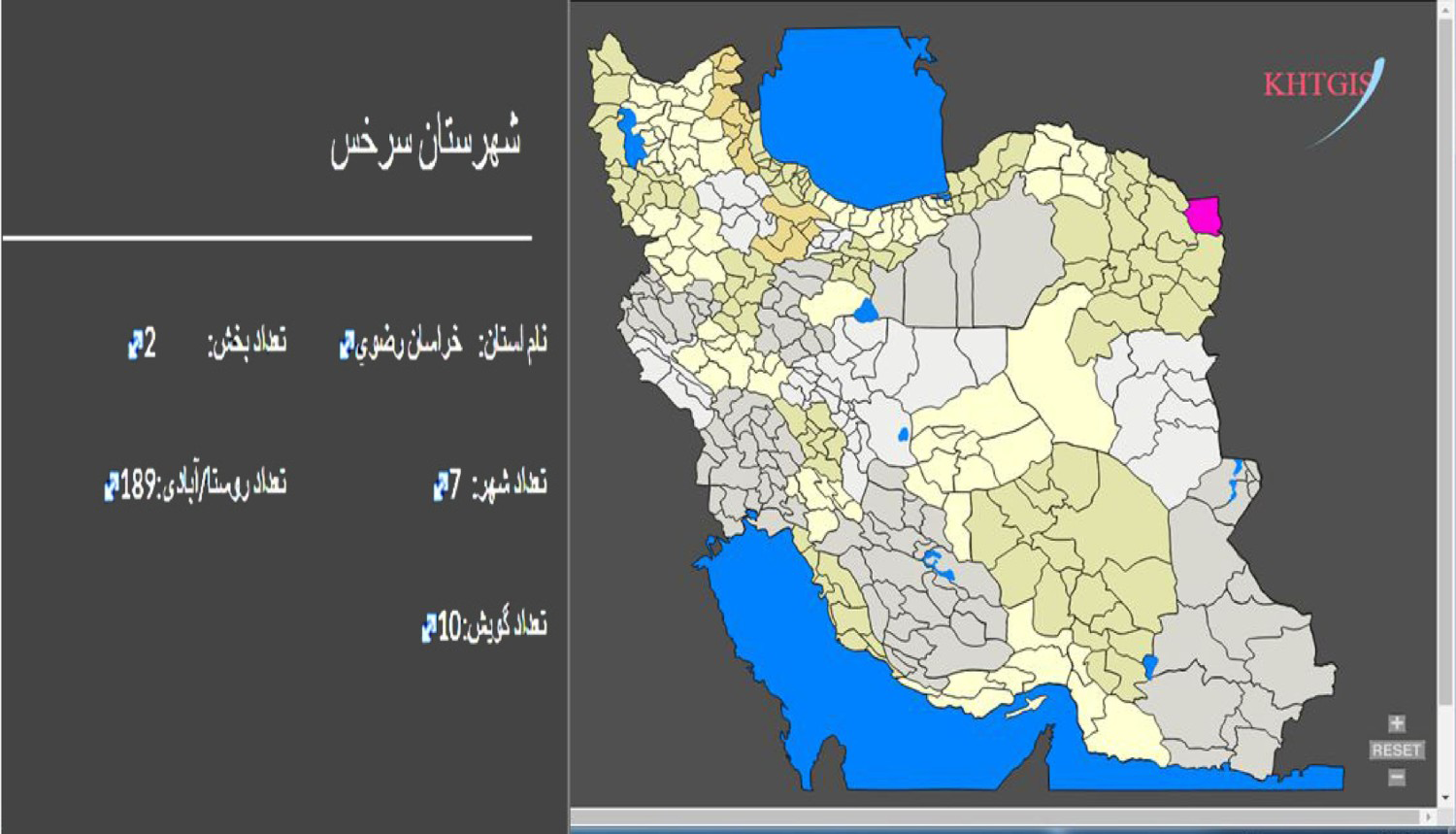

As stated before, the software program of the ILA has been revised and updated recently to fulfill the needs of the project. Linguistic data from villages of Saraḫs County (in Ḫorāsān-e razavī) was from the start prepared on the computer as a test phase of the dynamic Atlas. Today more information has been uploaded to the system and the software has proven its capability for drawing self-organized color maps.

The program was designed to use plotting systems for mapping and GIS systems. The responses of every informant to the questionnaire items produced with highly technical keyboarding in narrow IPA transcriptions are recorded in separate data tables for each item (105 words and phrases, 36 sentences).

Some pages of ILA software are introduced here to show how it works. The ILA software has four main parts: System, Questionnaire, Atlas, and Basic information. The most linguistically important parts are Questionnaire and Atlas.

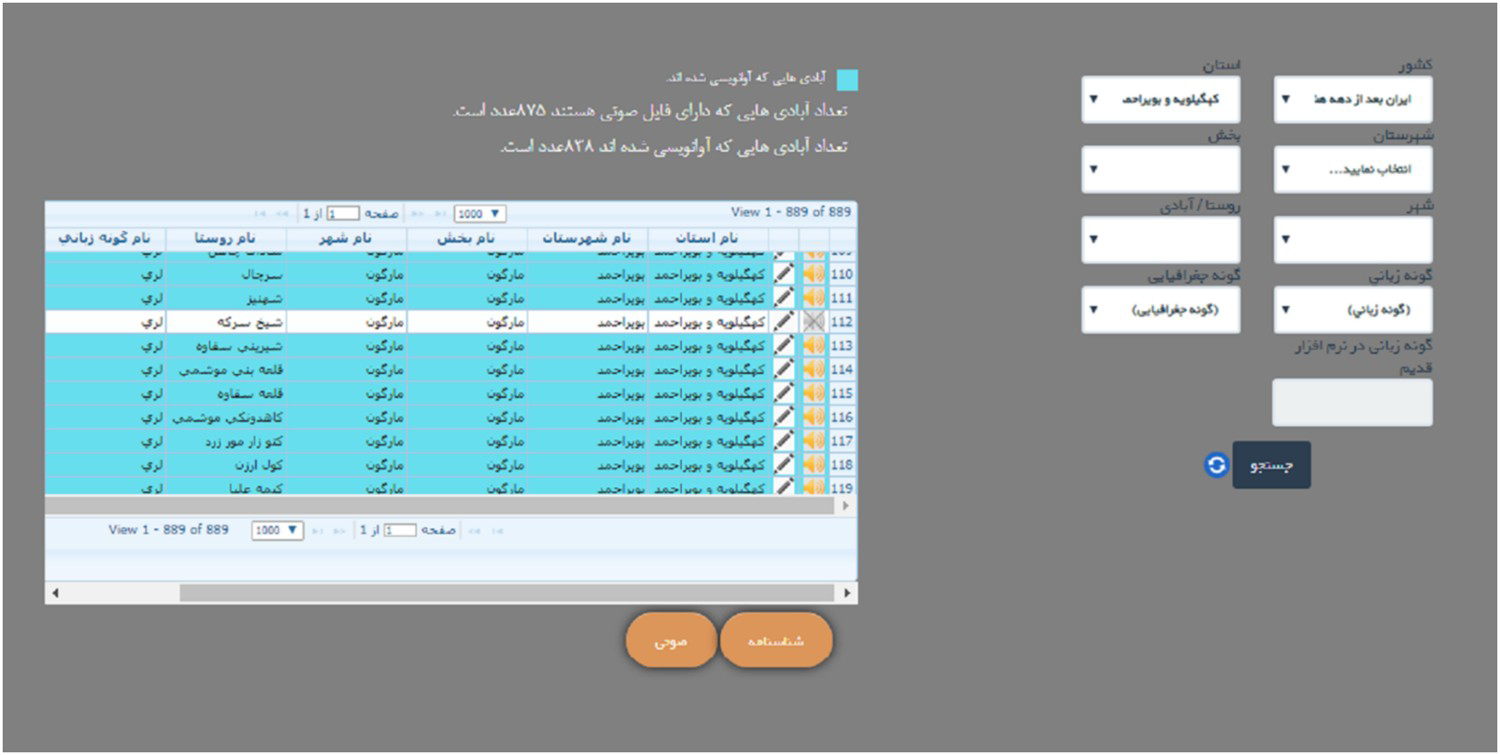

Figure shows a page for recalling a village or a language variety. By filling up each of the combos on the right, arranged from more comprehensive category to the least one (from province to county then to distinct and finally to the village and the language variety), the linear information appeared on the left side in the chart would be more specific. In this figure “Kohgīlūyeh va boyeraḥmad” has been selected as in the Province, and as a result only the information about this province is shown on the left. The loudspeaker icon (when it is not crossed) before each village’s divisions indicates that the audio file of the interview is available in the system and can be heard by clicking on it. Wherever a row is colored blue, it indicates that the linguistic interview of that village has been transcribed in IPA. The number of villages with transcriptions and the number of villages that their audio files are uploaded to the system is shown at the top of the chart. Choosing any of the language varieties—without choosing any province—on this page will have the result of showing all of the geographic distribution of that language variety throughout the country with the names of provinces and the related information.

Figure 7. The first page of ILA software for recalling the information for the requested village or language variety.

At the bottom of the page, two clickable boxes are shown: Information booklet and Audio. Whenever only one village is chosen either by clicking on its corresponding row or by filling up all its administrative divisions in the right combos, the Information booklet or the Audio can be selected at the bottom. When the Information booklet is selected, the metadata and the related information about the village and the language variety appears. By selecting Audio, the audio file—if it has been uploaded—can be heard and the transcriptions of the questionnaire items can be done or observed. Figure 8 shows the audio section.

Figure 8. The page of ILA program for transcribing the village’s audio file and observing the existing transcriptions.

In the Atlas section of the program, different choices are available for producing linguistic maps and obtaining visualized information. If it is chosen to view graphic layers of provinces, cities and villages, the Iran map would appear with those layers. In this case, each part in the map is clickable, with the information regarding the first administrative division and the number of smaller administrative divisions and the number of reported language varieties spoken there shown on the left. Figure 9 shows an example.

Figure 9. Saraḫs city is colored when it is clicked, the information regarding its administrative division and language varieties pops up on the left.

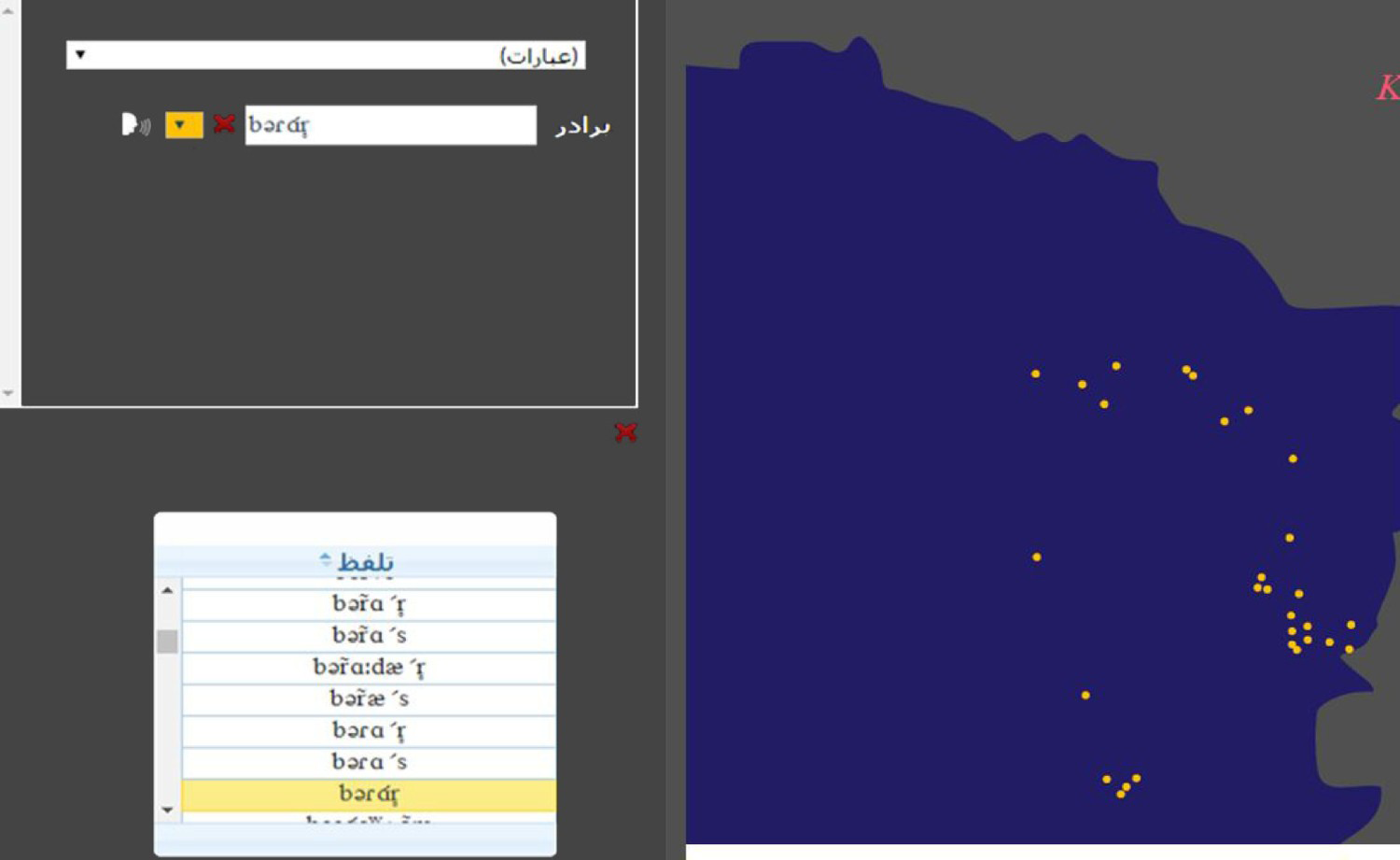

When it is chosen to see the layers of a county’s villages, by clicking on each one, the information box concerning the transcriptions of the standard name and its local pronunciation, the local name (if it exists) and its transcription, the administrative divisions and the number of language varieties—which is also clickable and the name(s) and total speakers of that variety appears—pop up on left. As Figure 10 shows, in Barzangān village two language varieties—Turkic (Torkī) and local Persian (Fārsī-ye maḥalli)—are used, with 200 and 600 speakers respectively. The number of speakers indicated here for each language variety is just what had been stated by the villagers and informants, probably based on the number of people whose mother language was Turkic or Persian. To observe the geographic distribution of language varieties, the program offers an opportunity to choose up to five language varieties at once and assign different colors to them. So, after clicking on the search button, the villages with the elected language varieties will be highlighted by the chosen color. If a village is bilingual or trilingual, it would have two or three chosen colors. Figure 11 shows the distribution of Blochi (Balučī) and local Persian (Fārsī-ye mahallī) in Saraḫs county.

Figure 10. Layers of the villages of Saraḫs, showing the information regarding Barzangān village and its language varieties on the left.

Figure 11. Showing different language varieties on the left that can be chosen and highlighted.

Note: Here, Balučī is highlighted green and Fārsī-ye mahallī is red. Colour online.

In the same way, any particular item on the questionnaire and different dialectal equivalents for it can be chosen to be shown in the geographical space. Figure 12 shows the different equivalents for “mother” in the same area. By clicking on each colored part, again, the name of the village and its information pops up.

Figure 12. Showing distribution of different dialectal equivalents for “mother” in Saraḫs county.

Note: Different dialectal equivalents for “mother” in Saraḫs county [næ'næ] green, [mɑs] yellow, [Ɂɑ'nɑ] blue and [mɑ'si] red. Colour online.

The program more recently began to use the GIS system for mapping with the same facilities for creating colored dots on maps. Figure 13 shows an example of mapping geographic distribution of language varieties (for now, only a small portion of the linguistic data has been converted to the GIS system). Again, if a village has two or more language varieties it will be marked by the two or three colors. Figures 14 and 15 show two other examples of linguistic mapping by the ILA software program.

Figure 13. GIS-based map showing geographic distribution of linguistic varieties.

Note: Balūčī white, Torkī blue, and Fārsī-ye mahallī red. Colour online.

Figure 14. By pointing to a dot on the map, the information about that particular village appears on the left.

Figure 15. Distribution of one of the dialectal equivalents for “brother” on the GIS-based map.

The software program is web-based and phonetic transcribers can access it by the activation of their permanent IP addresses and through passwords. The Atlas is not available online yet, but by the time of completion, with consideration of security matters, it would be accessible to the academician and the broader public.

Conclusion

This article introduced the Iran Linguistic Atlas, its background and the progress of its current phase. It has been over forty years since the innovative project for documenting Iran’s great linguistic diversity first launched under the name of Farhangsāz, and it has been continued—although not steadily—under the ILA. I hope to have shown that the ILA with the advantage of the precious data gathered by Farhangsāz—which remains to this day the most comprehensive linguistic data ever gathered from Iran’s rural areas—has a unique position among other projects conducted to compile a language atlas of Iran.

As mentioned, the ILA continued to gather data from Iran’s villages with the same guidelines as Farhangsāz, resulting in the largest number of audio files of Iran’s languages and dialects, containing more than 25,000 recorded interviews. More than 7,000 of these recorded interviews have been transcribed, making a valuable corpus for studying the languages and dialects of Iran. Although none of these audio files and transcriptions have been released or published on their own and were not been available to the public, they have been available to the PhD students and scholars; and many scientific works including PhD theses, published articles and conference papers have resulted from the data collected and transcribed in this project. The decision to create free access to Iran’s Linguistic Atlas as an interactive online Atlas should be made at high-level management; however, we are willing to give researchers and the public free access to each province’s Linguistic Atlas after completing, taking into account data security and confidentiality.

The project has also taken advantage of technological enhancements to create high quality, searchable digital archive for generating self-organizing colored maps. It can now present GIS visualization of language varieties in Iran and their linguistic characteristics .

Comparing Farhangsāz data, gathered over forty years ago, with more recent data gathered in the new phases of the ILA, helps the scientific society to achieve an overall picture of the transformation of spoken languages and dialects of each region as well as being a precious tool for analyzing the changes which have been occurred in each regional language variety over the time. This kind of study could be done whenever new data is collected from a region previously surveyed by Farhangsāz.

Moreover, rich sociodemographic, cultural and ethnological information gathered village by village in this project enables the Atlas to extend its analysis beyond the purely linguistic and offers insights into the relationship between language and society.

The ILA is now in progress. Current activities include the aims to improve the ILA and reduce its current limitations.

- Gathering data from those areas which have not been surveyed previously and adding them to the Atlas database. Although those areas have priority, we also aim to gather new linguistic data from previously surveyed areas, especially those surveyed by Farhangsāz over forty years ago.

- Creating phonetic databases or completing the existing ones for those provinces where the linguistic interviews have not been (completely) transcribed. We should also consider transcribing the audio- and more recently video-recorded free speech in the near future. The digital database should be improved for this purpose.

- Improving the capacity of the ILA software program, especially for transcribing, analyzing and representing linguistic features based on free speech.

- Foreseeing urban dialectological projects within its overall framework in the future versions of the ILA.

We believe that national and international joint projects for completing the data-gathering, databases of phonetic transcription and improving the ILA software program would certainly accelerate and improve the project, and so they would be welcomed.