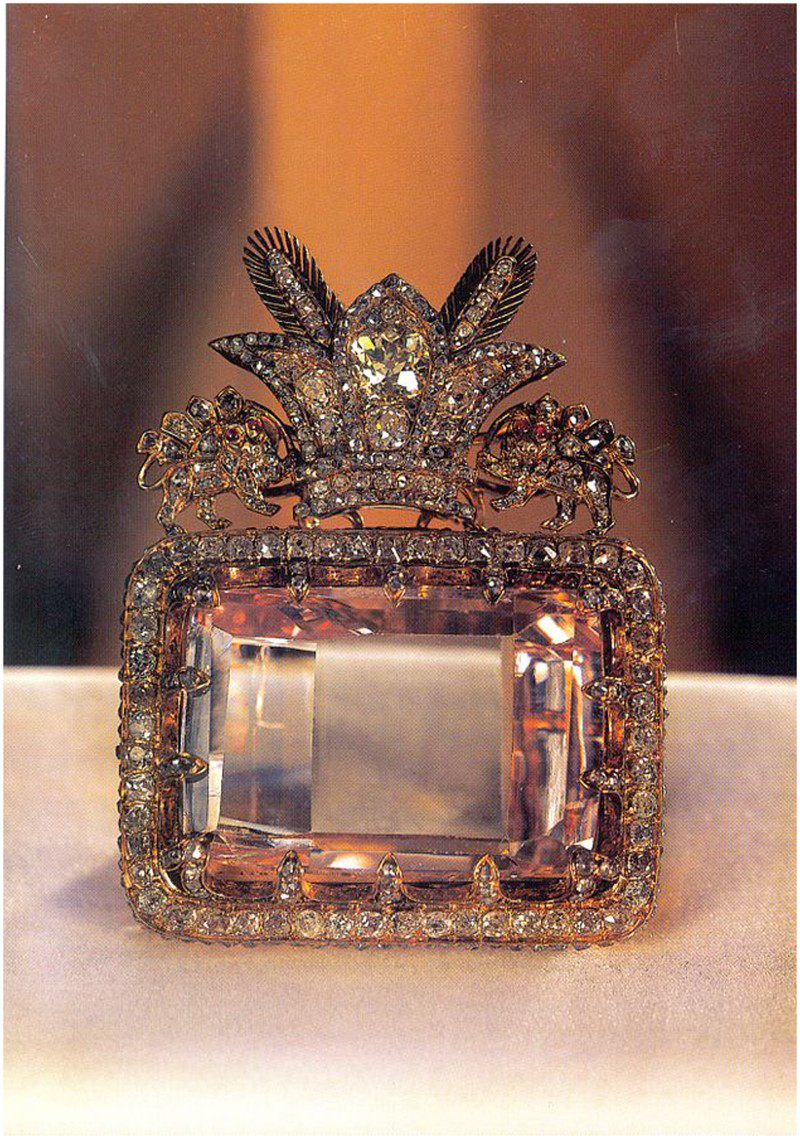

The vault of the Central Bank in Tehran houses Iran’s Treasury of National Jewels. Among the objects stored there is a diamond known as Daryā-ye Nur or the Sea of Light (case 34, no. 2). This flawless, step-cut tablet of extraordinary limpidity, measuring circa 41.40 by 29.50 by 12.15 millimeters and weighing around 182 metric carats, is the world’s largest known pink diamond (Figure 1). Several researchers have been interested in the history of the Daryā.Footnote 1 As far as I know, however, until now, no one has tried to present the detailed history of this stone or circulating tales about it based on primary sources, iconographic material, or gemological analysis. Such then is the main purpose of this paper. While reconstructing the history of the Daryā-ye Nur, I will try simultaneously to show how this diamond was perceived in the East over the centuries and the meaning attributed to it.

Figure 1. Darya-ye Nur diamond.

Source: Anonymous, Treasury of National Jewels, n.d. (out of copyright).

The History of the Daryā-ye Nur after 1739

The earliest mention pertaining to the diamond named Daryā-ye Nur, which I was able to find, is in a work from the times of Nader Shah (1736–47), in which this stone was listed among the jewels confiscated by this ruler from the Mughal Treasury during his invasion of India in 1739.Footnote 2

After the killing of Nader Shah in 1747, the Sea of Light passed into the hands of ʿAlam Khan ʿArab, one of Nader Shah’ s military commanders and the mighty viceroy of Khorasan (1748–54).Footnote 3 Owing to mediation of the emirs of Khorasan, the Daryā along with other jewels was then gifted to Mohammad Hasan Khan Qajar—father of Aqa Mohammad Khan (1789–97)—later first ruler of Iran from the Qajar dynasty. This gesture was most certainly to assure the Khorasanis of the goodwill of this mighty tribal leader. Mohammad Hasan Khan was defeated in battle by the army of the Zands and was killed in 1759. His political rival, Mohammad Karim Khan (1751–79), the first ruler of Iran from the Zand dynasty, also became the next owner of Daryā-ye Nur.Footnote 4

In 1791, desperately needing funds for the fight with the Qajars, the last monarch from the line of Zand, Lotf ʿAli Khan (1789–94), planned to sell the Sea of Light abroad, with the aid of Harford Jones, a British man who at that time was engaged, among other things, in the gem trade. He advised giving it a brilliant cut to make the stone more marketable in the West.Footnote 5 Fortunately, the idea of refashioning the diamond was not executed and in 1794 Lotf ʿAli Khan, who was jailed in the city of Bam by the local governor, decided to send it to Aqa Muhammad Khan who was winning the war against him. Daryā-ye Nur was in the possession of this ruler when in 1797, in Shusha in Nagorno-Karabakh, he was murdered by his servants. The perpetrators of the crime stole the stone—kept, as was customary with especially valuable jewels, in the women’s quarters—hoping to assure for themselves protection by sending it, along with other of the monarch’s precious objects, to the Kurdish emir,—Sādeq Khan Shaqaqi.Footnote 6 The emir initially did not believe in the death of the ruler, thinking undoubtedly that Aqa Mohammad Khan himself was putting his loyalty to the test, and accepted the jewels only after he became certain of the death of the shah. Then Sādeq Khan, who decided to contest Fath ʿAli Shah Qajar (1797–1834) for rule over Iran, went to Ganjeh in Azerbaijan, where the jewels also journeyed. The fight for the throne was lost by the emir; in August 1797, as a sign of subjection to the new ruler, he returned some of the jewels to him, among these was Daryā-ye Nur.Footnote 7

In 1834, FathʿAli Shah ordered an inscription to be engraved on the stone that, as in the case of Timur, described him as Lord of the (Auspicious) Conjunction (al-Soltan Sāheb Qerān FathʿAli Shah Qajar 1250). Since in the world of Islam gems with inscriptions usually had a smaller material value than those without them, it was thought that the shah’s decision halved the value of the Daryā, estimated previously by a westerner at £200,000.Footnote 8 Engraving the Sea of Light was commented on ironically by the author from the epoch of later Qajars, who stated that by placing his name on the stone Fath ʿAli Shah wished to define himself at least in some way, because during his entire rule he did not do anything exceptional.Footnote 9 According to legend, Daryā-ye Nur was also the last object on which this monarch gazed on his deathbed.Footnote 10

Among later Qajar rulers, the special attachment to Daryā-ye Nur was continued by Naser al-Din Shah (1848–96). This ruler attributed to it an ancient provenance, designated special keepers for the stone from among the court notables and believed in its medical and amuletic properties.Footnote 11 Naser al-Din Shah, when he felt weakened after an illness, had the Sea of Light brought to him hoping that the diamond would heal him; he did not part with the diamond even in the bath. Once when he was in the bath the stone fell out of his hand, and even though it was undamaged, the monarch was unhappy for three days because of this, saying: “What would I do if the diamond was damaged, what would I say to future rulers and foreigners?”Footnote 12

It should be made clear here that during the times of the Qajars some of the king’s guests, as well as foreigners visiting the Golestān Palace in Tehran, had the chance for a private viewing of crown jewels. During the reign of Naser al-Din Shah, the jewels were arranged on a table for this purpose. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the jewels were stored in boxes and later in glass cases, making it possible for visitors to view them. However, after a theft, or rather thefts during the 1880s–1890s, security was enhanced by locking some of the precious items away to prevent incidental viewing.Footnote 13 Among the jewels protected in this way was Daryā-ye Nur, enclosed in an iron box under the seat of one of the royal thrones and its viewing was possible only with special permission from the premier.Footnote 14

The exhibiting of the most precious royal jewels to important visitors, at the order of the Qajars, inscribed itself into a long tradition in the world of Islam. Such objects were described in the East by the term tuhaf or marvels—universally associated with “value and worth”—and were natural objects of “singularization,” which involved showing them by rulers or court officials to foreigners, mainly foreign envoys and merchants, and this was sometimes accompanied by tales of their history.Footnote 15 This was a way to show that the monarch’s riches translated into military might, widespread trade and diplomatic contacts, ancient origins of the dynasty, and also loyalty of subjects since dues to the ruler were often paid in gems. During the presentation of this type of “status goods” the visitors were asked if their monarchs had similar valuables; this information then was used to evaluate the fortune and thereby the capabilities of a given ruler.Footnote 16

Besides showing visitors to Tehran the gems he had, Naser al-Din Shah wore them on his person during travels abroad. He also organized exhibits of these stones to a select European public, which was usually under huge impression of the diamond spectacle despite occasional voices of criticism.Footnote 17 Presentations of this type took on the form of a kind of dialogue of power, as European monarchs also presented themselves to the shah adorned with exceptional diamonds and thus made it possible for him to view the historical stones in their possession. The jeweled dialogue was continued by the successor of Naser al-Din Shah—Mozaffar al-Din Shah (1896–1907)—who had decorated himself with important gems, including the Daryā, during his travels beyond Iran and allowed his jeweler to pass out information about them to the European press.Footnote 18

In 1909, during the Constitutional Revolution, Daryā-ye Nur almost left Iran permanently. At that time, Mohammad ʿAli Shah Qajar (1907–9), planning emigration, took some crown jewels, among them the Daryā, and took refuge with them in the building of the Russian legation. After negotiations with the Constitutionalists, he did however agree to return the objects to the Golestān Palace in exchange for an annual pension equivalent to £15,000.Footnote 19

An change in status of the royal jewels, including the Daryā, which until then had been in the disposition of the shahs, had begun in 1931. At that time, these were valued by the famous French jewelry firm of Boucheron, which made possible their use as collateral for the government’s obligations in connection with the issue of its banknotes.Footnote 20 Seven years later these precious items, no longer being the private property of the shahs, were transferred from the Golestān Palace to the National Bank of Iran, while in 1960 the Central Bank of Iran took over custody the jewels.Footnote 21

How Did the Rulers Wear the Daryā-ye Nur?

In Persianate cultures, luminosity was considered to be one of the symbols of kingship. In the Muslim period, luminosity was interpreted in certain contexts as visualization of the ancient Kayanid khvarenah—royal glory—and was described by the term farr-e izadi or divine glory. This glory was acknowledged as communicated from God to kings; then it was known as farr-e shāhi, kingly glory.Footnote 22 Shiny objects, including gems, were often regarded as physical images of this invisible perfection. For this reason, especially if they were exceptional specimens of huge value, gems were held as objects proper to rulers—shadows of God on earth.Footnote 23 Large gems were usually subject to monopoly of local monarchs. Also, each person who came to possess an important specimen in an area where these were not gathered, should offer it to the ruler.Footnote 24 At court, the ceremonial gifting of an important gem was deemed symbolic acknowledgment of the sovereign’s rule, while holding back a gem due to the rulers led to severe punishment. Exceptional, perfect stones, the possession of which was the subject of rivalry and envy, were as a rule excluded from normal market trading; their sale was considered only when the dynasty was in danger. If such stones changed hands, it was usually as booty or gifts, even though their voluntary transfer was as a rule equivalent to surrender of power.Footnote 25

Impressive gems, constituting the quintessence of perfection, also sometimes played the role of regalia. Possessing such stones, as well as jewels in general, to which ancient provenance was assigned, was to demonstrate wealth, antiquity, and continuity of the monarchy. In view of its uniqueness and value, Daryā-ye Nur was especially fitting for the role of relaying the glory of the olden rulers and the symbol of thousands of years of the Persian monarchy, as well as triumph over the fabled empire of the Great Mughals. In the epoch of the Qajars, a conviction was prevalent that without this sign of dominion belonging supposedly to ancient rulers of Iran, the Qajars could not call themselves rulers.Footnote 26

The Daryā was also a crown jewel perhaps worn most often by the shahs, who used it as their ornament in many ways. According to sources maintained among Iranian Jews, the way the diamond was worn was to be in relation to the power of the ruler holding it. The stronger the monarch, the more nonchalant was the way he exhibited the stone. It was said that Nader Shah had placed the Daryā in the rear part of his saddle; the rulers from the Zand and Qajar decorated, respectively, armlets and the crown with it; while later monarchs were to have modestly refrained from wearing this jewel.Footnote 27 In reality, though, the Sea of Light was most certainly placed on the headgear of Nader Shah, as shown in the ruler’s portrait from 1774 housed in the Saʿdābād Palace in Tehran (Figure 2). Successive kings of Iran decorated their armlets with this gem.

Figure 2. Portrait of Nader Shah by Abul Hasan, 1774, Saadabad Palace in Tehran (out of copyright).

Analysis of iconographic material allows for supposition that at the latest from the times of Fath ʿAli Shah Qajar,several such ornaments had been made. The Daryā would be placed in those armlets in a way that made possible its removal. Along with the armlet decorated with the Sea of Light, the rulers habitually wore an armlet with a diamond of 115.6 carats—the Tāj-e Māh or Crown of the Moon. This latter stone also came from the Delhi booty.Footnote 28 When after middle of the nineteenth century (most probably about 1855–60) the armlets went out of fashion, Naser al-Din Shah decorated his watch-chain and belt buckle with the Sea of Light, placing it there surrounded by eight large diamonds, most certainly Mughal-cut.Footnote 29

During the times of Naser al-Din Shah, the Daryā-ye Nur was most probably set in a way that made it possible to remove it from the setting and to use as a centerpiece in other decorations. At present, the Daryā is in a frame from which it is not possible to remove it without damaging it. This frame is studded with 457 diamonds and four rubies and is topped with a miniature of the Kayanid Crown—the primary symbol of the Qajar monarchy—flanked by two miniatures of Persia’s official emblem, the lion and the sun (Figure 1). It is logical to assume that this frame was made during Qajar times. The earliest image that I was able to find of a king of Persia wearing the Daryā in this setting is a photograph by Antoin Sevruguin dated 1890, which shows Naser al-Din Shah wearing headgear adorned with the stone.Footnote 30 It is known, however, that in 1892 this ruler allowed his French doctor to study the Daryā; he had described a stone carried by the shah in his pocket without mentioning its setting. This author gave the dimensions of the diamond, together with its thickness, which would have been difficult if it was set in a gold frame.Footnote 31

Diamond decorations with the Lion and the Sun motif were fashionable during the reign of Naser al-Din Shah, who decorated his headgear with them. It is known that such precious objects delivered to the Persian court about 1889 were the work of Parisian jewelers.Footnote 32 The style of the Daryā’s setting indicates that it also was made by or under the influence of specialists from the French capital. It is probable that during his stay in Paris in 1889, Naser al-Din Shah, who was interested in jewels, sketched designs of settings for “some valuable stones.” This ruler had then engaged, for a period of three years, two graduates from a jewelers’ school.Footnote 33 Even though in 1890 the Daryā’s setting must have been finished, as was customary in the case of this diamond it was set in a manner allowing for its repeated removal. It is known that Naser al-Din Shah’s successor, between about 1896 and 1899—maybe also during the time of Naser al-Din Shah—decorated his headgear with the Sea of Light set in a most likely locally made simple gold frame decorated with three probably rose-cut diamonds.Footnote 34 However, as Naser al-Din Shah’s successor, during his visit to Europe on the occasion of the World Exhibition 1900, wore the Sea of Light in its present setting, it is possible that prior to the trip the stone was safeguarded against the possibility of falling out by making impossible its removal from the brilliant frame.Footnote 35 This stone was worn in this way by other rulers till the end of the Persian monarchyFootnote 36 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Photograph of Reza Shah Pahlavi with Darya-ye Nur diamond on his headgear (out of copyright).

Sisterhood of Diamonds : Daryā-ye Nur and Kuh-e Nur

Even though in the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries the Daryā-ye Nur was often worn by the shahs together with the Tāj-e Māh diamond, it was not that stone but another one that the widespread tradition in Iran connected with the Sea of Light. Already in the eighteenth century, an English-language author claimed that the Daryā had its “fellow,” which was a 191.03 carat diamond, the Kuh-e Nur or the Mountain of Light, describing both these stones, undoubtedly in view of their size, as the “generals among diamonds.”Footnote 37

In Qajar Persia the view was widely popular that the Daryā and the Kuh were “sister stones.” The concept of being related, of brotherhood or more often sisterhood of gems, was known in the East many centuries earlier. In earlier ages of Islam, it referred to specimens almost identical in appearance, usually pearls, the price of which in a pair was significantly higher than in the case of specimens sold separately.Footnote 38

Besides the proximity in weight, the Daryā and Kuh do not demonstrate any similarities. Both diamonds were obtained by Nader Shah from the Mughal treasury, although the Kuh, directly after the murder of the king of Iran ended up in possession of the rulers of Afghanistan from the Dorrani dynasty. In later times this stone, mistakenly considered to be the largest diamond in the world, became the property of Ranjit Singh, maharaja of Punjab, and his descendants, and then as booty in 1849 was found in the possession of the British.Footnote 39

In nineteenth century, in the lands of the shahs, it was believed that the Kuh-e Nur and Daryā-ye Nur decorated the sword of the legendary Turanian king Afrasiyab, but the Persian hero Rostam was supposed to have taken them away from him. These stones were then set into the crown of the Kayanid and later kings of Iran; afterwards stolen by Timur and became the property of his Mughal descendants. These latter were deprived of them by Nader Shah as part of historical settlement of accounts.Footnote 40

Tales of the Daryā’s provenance in ancient times were popularized by Naser al-Din Shah, who told these stories to foreigners visiting his court.Footnote 41 It is not to be ruled out that this ruler was also the author of at least some of these tales. Exceptional gems in the world of Islam were associated with Kayanid rulers for many centuries before Naser al-Din Shah, and also customarily accompanied by fabrication of the past of such objects in order to underline the affiliation of their owners with “the global family of famous rulers.”Footnote 42 Even though similar overtures were not unknown to Naser al-Din Shah, during whose times popularity was gained by a story of the past of a 500-carat spinel of the Qajars as having had decorated the neck of the biblical golden calf, the Daryā was seen by this ruler not as a cross-cultural symbol of power but as connecting the Qajars to the rulers of ancient Iran.Footnote 43 This is known because Naser al-Din Shah, who most certainly was not especially proud of his Turkic ancestry, preferred tales according to which the Qajars had their origins in ancient Persian dynasties.Footnote 44

In the Muslim Persianate world, regalia were acknowledged as carriers of farr and the Qajars were described as holders of the farr of Iran’s mythical kings.Footnote 45 It is possible then that Naser al-Din Shah, by presenting the Daryā—a shiny stone with a “luminous name”—as belonging to his supposed ancient predecessors, and by underlining this through a new setting with the Kayanid Crown (despite the ubiquitous character of this image in Iran of that time) demonstrated in this way their khvarenah, which in the form of his farr-e shāhi was a visible sign of the Persian origin of the Qajars and continuation of the Persian kingly tradition.Footnote 46

The Kuh-e Nur was also perceived as a connection with the mythical past since according to Indian folklore it appeared on earth through the action of the Hindu sun god. Awareness of this connection was especially important after the stone was taken to Great Britain. In Iran at that same time, the Kuh was acknowledged, like the Daryā, as a genuinely Persian stone.Footnote 47 In this context, it becomes credible that several persons who in the nineteenth–twentieth centuries had viewed the Tāj-e Māh diamond in Tehran as part of the regalia of Iran were convinced that they were looking at the “King of Diamonds”—the Kuh-e Nur. Reports of this type are too many to have ensued from a simple mistake, especially since the name Kuh-e Nur was used in reference to Tāj-e Māh by the Qajars’ treasurer.Footnote 48 Most certainly, then, at the latest from the reign of the first Qajars the Tāj-e Māh was described at the Persian court by the name of Mountain of Light.Footnote 49

The cause of this state of affairs was the wish to create an impression that the Qajars possess this ancient Persian regalia. Since the regalia would only be missing from the treasury in case of a desperate economic situation or lost wars, which symbolized giving up the power to rule, such a well-known diamond as the Kuh-e Nur from the Persian treasury could have been viewed by some officials at the Iranian court as creating an image problem. Another stone of high quality was then named Kuh-e Nur to underline the possession of both of these ancient Persian regalia.

The Daryā-ye Nur and Kuh-e Nur were so famous that names of these stones, often in distorted form, were used in reference to diamonds found in the treasuries of various Muslim rulers, as well as to those offered for sale by traders. In this latter case, the reason for this state of affairs was often one of marketing. From the eighteenth century in the East, several Kuh-e Nurs appeared.Footnote 50 Among the most famous Daryā-ye Nurs, one should mention the 26-carat table stone which in the nineteenth century was the property of Nawab of Dhaka, at least two specimens found in the possession of the then royals of Afghanistan, and also the 85-carat Bornean diamond, which appeared on the Amsterdam market in 1763.Footnote 51

“Sister stones” Kuh and Daryā often were compared by Persians and also by the British. Each of the parties usually concluded that the “sister” in the possession of their rulers was more important and more valuable. Persians as a rule stated that the Daryā is priceless and illustrated this with the opinion of Nader Shah’s jeweler, according to whom the value of this stone would correspond to a mountain of gold heaped to the point where a coin would reach when thrown upward by a four-year-old child.Footnote 52 The price of the Kuh-e Nur was also determined in a similar way in the nineteenth century East.Footnote 53 The British were more objective when valuing the Daryā, before its inscription, at £200,000–296,000, while they assessed the value of the Mughal-cut Kuh-e Nur at £2 million.Footnote 54 In view of the fact that the Daryā is an exceptionally rare flawless pink stone, while the Mughal-cut Kuh had flaws, its valuation must have been dictated rather by considerations other than market value. Most certainly, it was connected with the symbolic significance of the Mountain of Light, seen by the British as a sign of their subjugation of India.Footnote 55

Market criteria were applied in the 1850s to estimate the value of Mountain of Light by the famous British mineralogist James Tennant when he valued it at £276,768, “if [it] was perfect.” He did state, however, that this diamond had no place among the perfect stones due to its imperfections and also its Mughal cut, deemed crude in the West, so that he recommended its re-cutting.Footnote 56 However, if the principles of seventeenth century India were applied in the valuation of the Kuh, its market value could be even about 30 percent lower as compared with the Daryā-ye Nur.Footnote 57

Daryā, Nur al-ʿAyn and the Great Table

Already towards the end of the eighteenth century, similarity was perceived between the Daryā and a diamond that merchants from Indian Golconda offered in 1642 to the famous French diamantaire Jean-Baptiste Tavernier for 500,000 rupees or about 5.6 tons of silver coinsFootnote 58 (Figure 4). This stone, weighing, according to the Frenchman, 176 1/8 mangelins or about 248 metric carats, through a Victorian jeweler and author Edwin Streeter, became known as the Great Table.Footnote 59

Figure 4. Drawing of the Great Table diamond by Jean-Baptiste Tavernier.

Source: Tavernier, Les six voyages, 1692, vol. 2 (out of copyright).

In the view of Canadian mineralogists, who during the reign of the last shah examined the treasury of Iran, the Great Table and Daryā-ye Nur, whose weight they were only able to estimate, because of the impossibility of removing the setting, at between 175 and 195 carats, were one and the same stone. The shahs’ jeweler, who in 1791 spoke with the abovementioned Harford Jones, described Daryā’s weight at somewhat over 176 Persian carats, or about 188 metric carats. Various Persian-language chroniclers maintained that the weight of the Sea of Light was: 180 local or about 192 metric carats; 8 ½ methqāl, corresponding then to over 196 carats; or finally 8 methqāls, the equivalent of almost 185 metric carats.Footnote 60 In publications pertaining to valuation of crown jewels by experts from the House of Boucheron, in respect of the Daryā-ye Nur the weight of 182 carats appears. This weight, in my view, should be acknowledged as the most probable.Footnote 61

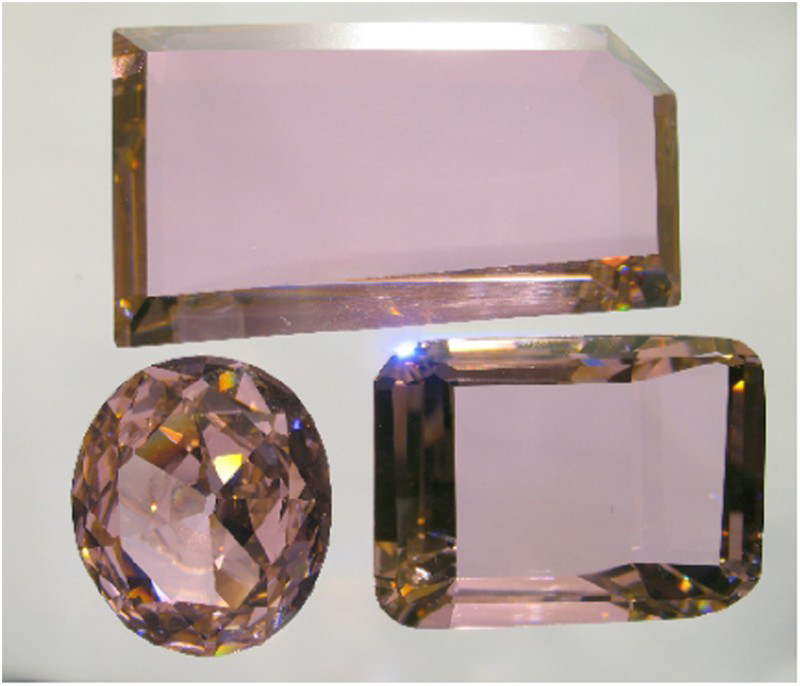

The Canadian experts claimed that after Harford Jones’ visit in 1791 and before 1834, because the latter date was engraved on the largest of the side pavilion facets, this stone “suffered an accident,” as a result of which its irregular part was cut off. They had also convincingly proven that the remaining part of the Table may be the pink brilliant named Nur al-ʿAyn or the Light of the Eye, adorning the wedding tiara of the wife of the last ruler of Iran, Farah; it also at present rests in the Tehran treasuryFootnote 62 (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Darya-ye Nur, the Great Table and Nur al-Ayn, replicas.

Source: by permission of Scott Sucher.

Figure 6. Naser al-Din Shah Qajar with the Shah of Persia diamond on his chest, photograph taken in 1889 in Germany (out of copyright).

After adding the 60 carats that this last stone was said to have weighed and the 182 carats of the Daryā we would have only a few carats from about 248 metric, which according to Tavernier was the size of the Great Table, from the unavoidable loss of material in cutting. Examiners of this problem, when discussing this issue, usually maintain that the Frenchman was mistaken regarding the weight of the stone.Footnote 63 In my view, one may wonder if the famous diamantaire did in fact have the opportunity to weigh this gem and, as he claimed, to make its lead model, or did he simply repeat from his informer, most probably a merchant, the description of the stone and information on its weight. A similar situation must have occurred for example in the case of the Bijapur ruler’s ruby, the image of which as well as the precise weight Tavernier had included in his work even though nothing indicates that he had the opportunity of viewing it.Footnote 64

Mineralogists who examined the Sea of Light in the treasury of the last shah claimed that for the Daryā and the Nur al-ʿAyn to be created, the weight of the Great Table should have been about 300 carats, while another contemporary expert engaged in this matter, Scott Sucher—an American master cutter who creates replicas of famous stones using computer modeling—calculated that the Great Table must have weighed around 350–450 carats.Footnote 65

Cutting off a fragment of the diamond could not have happened between 1791 and 1834 because this gem, as was said above, weighed over 180 carats in 1791, when Harford Jones saw it in the shah’s possession.Footnote 66 Also on the abovementioned painting from 1774 showing Nader Shah, the Daryā has a form, and thus also weight, identical to the present (Figure 2).

Perhaps key information for resolving the issue of the Great Table came from the work of a nineteenth century Turkish chronicler. This historian, citing a source from the previous century, maintained that Nader Shah brought the Nur al-ʿAyn diamond weighing almost 60 carats from the subcontinent.Footnote 67 Similarly to a note in the work of a Persian author of the eighteenth century, this tells us that the diamond named Nur al-ʿOyun or Light of the Eyes was the Delhi booty of the shah and allows us to determine that the Great Table was already cut by Mughal experts, who also most probably worked on the Daryā.Footnote 68 The Great Table could not have been cut during Nader Shah’s occupation of Delhi that lasted just over one month because the procedure would require at least twelve weeks of work. A cutter in the eighteenth century would have had to dedicate at least two years to preparing the Daryā.Footnote 69

It is possible that the working on the Sea of Light took place during the period 1713–39. In the collection of the British Museum there is a miniature portrait of the Mughal Emperor Farrokhsiyar (1713–19) wearing on his neck a medallion with a pinkish stone in a shape similar to the Great Table.Footnote 70 During the times of the Great Mughals, the Daryā-ye Nur must have had already borne its name under which, as is known, it was registered in sources from the epoch of Nader Shah as booty taken from Delhi.Footnote 71

Recorded history of the stone named Daryā-ye Nur in our disposition dates back to the period after 1739, whereas examination of the gemological material combined with analysis of written sources allows us to move its history back to the 1640s. In my view, it is possible also to make a reconstruction of the earlier history of this diamond.

Was the Great Table a Safavid Stone?

It is known already that after the Daryā appeared in Iran its mythology was being created to show this stone as historically Persian by ascribing to it possession by Cyrus, Rostam, or Timur. Communications about the Persian origins of the Daryā-ye Nur are also currently circulating in Iran. During my visits to the Tehran Museum of Royal Jewels in 2010, the guides informed visitors that the Daryā, belonging to Shah Abbas the Great (1588–1629), was stolen by the Afghans in 1722 during the “Sacco di Isfahan.” This stone was said to have then ended up in the Delhi treasury, and the Mughal’s persistent ignoring of demands for its return forced Nader Shah to organize an expedition in order to regain it.Footnote 72

Neither the history of the Great Table nor stories circulated on the topic of the Daryā-ye Nur in Qajar times mention Shah Abbas among its owners. According to primary sources, however, Abbas the Great did in fact possess a huge diamond with a weight close to that of this parent stone—the Great Table. Still, before considering the possibility that these two stones are identical, it is best to summarize the history of the Abbas stone.

According to the chronicler of the rulers of Bijapur, who completed his work in 1611/12, the monarchs of the Vijayanagar state, owners of a great wealth in diamond mines, had a colossal gem weighing about 300 carats.Footnote 73 At the center of the stone there was a black blemish, which led its owner to believe it bore bad luck, in line with the beliefs held on the subcontinent.Footnote 74

In his desire to rid himself of the ill-fated gem, and profit from it at the same time, the ruler took the decision to sell it. When he visited Vijayanagar in 1536, Ebrāhim ʿĀdelshāh I of Bijapur (1534–58), who clearly did not believe in the superstitions regarding flawed stones, bought the diamond for 800,000 huns, equivalent to over 2.7 tonnes of gold coins, due to a desire to use the diamond’s properties to treat the diseases which ailed him.Footnote 75

The stone did not, however, prove to be an effective remedy and after the monarch’s death it was sent back to Vijayanagar by Muslims of Bijapur who put their hopes in its malignant powers. The defeat suffered by the Hindu kingdom in a battle with followers of Islam in 1565 was ascribed by the people of Bijapur to the effects of the diamond wunderwaffe. After the fall of Vijayanagar, the gem found itself in Goa, where its five owners offered it for sale for 60,000 huns to a Portuguese. He could not make such a major purchase without consulting Lisbon, though, and Bijapur’s next ruler, ʿAli ʿĀdelshāh I (1558–79), took advantage of the time the Portuguese man spent waiting for a decision. This monarch sent a female agent to Goa, who, after the violent deaths of four of its owners, brought its last owner to Bijapur, where the sultan bought the stone from him.Footnote 76

The Shiite ʿAli ʿĀdelshāh I must have believed in the stories about the diamond’s nefarious properties, as he initially kept it at a safe distance from himself. Later, he sent the stone to a Shiite cleric to have its harmful powers neutralized. The gem was then presented to Shah Tahmasp of Persia (1524–76). When the gift arrived, however, the shah died and his successor Ismail only reigned for about a year. Both of these deaths were attributed in India to the influence of the diamond.Footnote 77 The next Persian ruler ordered the gem to be placed in the shrine of Imam Reza in Mashhad as the finial of a construction housed in it, made of gold and precious stones, with the height of one and a half lengths of a pike-staff.Footnote 78

Presentation of exceptional gems to shrines was of course widespread in the Islamic world and elsewhere. The donors set out large high-quality gems in the shrines and the public could view these, which in turn was an illustration of the wealth, munificence, and piety of the donors. Gems of this type were often hung like lamps as it was believed that they emanate exceptionally bright internal light that was interpreted as a manifestation of the divine.Footnote 79 Against this background, the sending by the Safavids of a flawed stone, to which lethal properties were ascribed, was exceptional. Circumstances preceding the sending of the diamond indicate that the Safavids wished to, at least for the time being, remove it from their surroundings while still exhibiting this ostentatious stone, and thereby displaying their own munificence and piety. Perhaps they also planned to remove the nefarious properties from the diamond through “sacred contamination” taking place as a result of its placement in a sacred environment, which imbued objects with barakah. Footnote 80 The sending by the Safavids of the diamond to a shrine did not necessarily have to mean permanently parting with it. There are known cases of rulers taking valuable objects from shrines, including diamonds, under the pretext of providing for their protection or benefiting from their sacred properties.Footnote 81

If the Safavids had any further plans regarding the Mashhad stone these were crossed by history. Under the reign of Abbas I, the diamond was stolen during plundering of the holy complex by the Uzbeks in 1589, and became the property of the ruler of Bokhara, ʿAbd al-Muʾmen Khan Shaybāni (d. 1598). Next, the stone found its way to Balkh in Afghanistan, from where it was taken by Uzbek dignitaries, who entrusted it to the Shaybanid Prince Mohammad Salim Soltan. In 1601, when Mashhad was already under the rule of Shah Abbas, the stone’s last owner paid tribute to the king of Iran by presenting the stolen diamond to him. The shah returned the stone to Mashhad. However, the ʿolamāʾ there did not want to keep the diamond and together with the officials responsible for waqfs decided that it should be sold, and for this purpose it was sent to Istanbul.

Commodification of desecrated shrine gems was not a customary modus operandi in the world of Islam. Other cases of this type are known; attempts were made to have the regained precious objects returned to their previous location.Footnote 82 The desecration act itself was then insufficient reason for the sale of such a stone, especially in view of restoration work at the shrine undertaken by Shah Abbas which required jewels.Footnote 83 It is known however that in Mashhad in the early 1600s the diamond still had the reputation of being a killer. It was said that because of its dreadful properties it was sold by Shah Abbas to his enemy, the ruler of Turkey.Footnote 84 I did not find information allowing for the belief that in Mashhad the stone was blamed for the Uzbek invasion, although the fact that this event occurred after the stone was placed in the shrine could have significance in the decision to remove it from the city and from Iran.

Most probably it was this stone that was described as “the largest diamond in the world”; it was offered in 1602 by the ambassador of the king of Persia for sale to Ottoman Sultan Mehmed III (1595–1603). This stone, worth according to Persians a million pieces of gold, was to have been valued by Mehmed at only an equivalent of 50,000 ecus. Since I did not find any mention in Ottoman sources of such a large diamond being in the possession of the Istanbul treasury, it most probably was not in the end purchased by the sultan, perhaps due to the excessive price demanded for the stone by the Persian side. It is known however that this stone was finally sold to an anonymous buyer for 30,000 methqāls or about 140 kilograms of gold, for which the land for the Mashhad shrine was acquired.Footnote 85

It should be mentioned that the fate of the stone in Istanbul was undoubtedly dictated by the rank held by the Ottoman capital in the gem trade. From the sixteenth century, this city was the most important center in the Middle East for trading in such valuables, including diamonds, with merchants seeking out the best specimens from as far afield as the subcontinent.Footnote 86 In Istanbul, Indians could buy large diamonds legally, while on the subcontinent such stones were, as it was said above, subject to a royal monopoly. As the Great Table is known to have been on the market in Golconda in 1642, it is possible that it reached India from Turkey.

Having sketched the story of the Abbas stone, which should really be called the Safavid diamond, it is time to return to the question of whether it was the Great Table. In my opinion, there are three factors which indicate that this is possible.

The first of these factors is its weight. According to the aforementioned sixteenth century historian of the rulers of Bijapur, the stone which later belonged to the Safavids weighed 15 methqāls, equivalent to 21 legal derhams. Footnote 87 Establishing the metric equivalent of the weight of a Bijapur methqāl of that time is a complex matter. However, due to the fact that in Bijapur the methqāl would have been used for the Arabian sea trade, it is not improbable that the Bijapuri units corresponded with the Ottoman. In such a case the methqāl would have been the equivalent of about 4.6 grams, and the legal derham about 3.36 grams.Footnote 88

This stone, then, would have weighed approximately 345–352 carats, which would place it within the weight range that, according to the aforementioned American master cutter, included the lower estimates of the Great Table. It should also be noted that the Muslim chroniclers were not, as a rule, particularly precise with regard to the mass of the diamonds they described, which could vary for the same specimen between several and even about a dozen carats, depending on the source.Footnote 89

Another problem to be considered is the matter of shape. While the weight of two similar diamonds is not sufficient reason to consider them to be one and the same stone even in the case of rare large specimens, clues concerning their shape provide much better possibilities. According to the chronicler of Bijapur, the Safavid diamond was the size of the palm of a hand and in the form of a square, a shape which Qajar sources also ascribe to the rectangular Daryā-ye Nur.Footnote 90 It should be stressed that the Mashhad stone, the Great Table, and the Daryā were also the only diamonds of this shape mentioned in the sources as weighing hundreds of carats.Footnote 91 The shape of the palm of a hand is of course arbitrary, but not dramatically different from the size of the Great Table, reconstructed by Scott Sucher, which measured 59.42 by 33.51 millimeters.Footnote 92

It follows from Tavernier’s accounts that when the Great Table was offered for sale in 1642, it had polished edges. This fact allows for the assumption that it was not a specimen delivered to the Golconda market straight from the mines. It is true that polishing workshops existed near diamond fields; however, it is most probable that in the seventeenth century only surface flaws were removed there, without drastic decrease of weight, as this was to make possible sale of the material at higher prices to the merchants coming to the mines.Footnote 93

The final question requiring scrutiny is the reason behind the decision to cut the Great Table. Contemporary researchers also accept as a certainty that the Great Table had no blemishes, which means that the existing literature takes for granted a supposition originating in the1960s that this stone must have suffered some mysterious “accident” necessitating the operation.Footnote 94 It should, however, be mentioned that Tavernier did not expressly describe the Great Table’s qualities. In my opinion, a more likely reason for cutting the stone was to remove the blemish which was believed to bring misfortune and lower its value. This flaw must surely have been positioned in such a way that it could not be removed by the polishing.

In my view, there are sufficient indications to conclude that the Great Table and the Safavid diamond are one and the same. This would make it possible to start the history of the Great Table, the parent stone of Daryā-ye Nur as much as two centuries earlier, and thereby allow for recognizing in this, the most important of the crown jewels of Iran, the only remaining large gem that belonged in the past to the Safavids.

Conclusions

The history of Daryā-ye Nur, from 1739 until now, is well documented; whereas reconstruction of its earlier course up to the early sixteenth century is possible through analysis of primary sources and gemological material. At present in the West and in India, this stone is not as well-known as its “sister,” the Kuh-e Nur. In the eighteenth century and at the beginning of nineteenth century, however, both diamonds were made famous through mention in the press and tales by travelers; specimens sold under their names were similarly popular both in the East and in the West. Especially after its appearance in Great Britain, the main object of interest of the western press and public was then the Kuh-e Nur, often falsely presented, of course, as the largest or the most precious diamond in the world. This promotion of the Indian trophy and in consequence the role that up to now is played by the Kuh in the debate pertaining to the colonial past reduced the interest of the western and Indian public in the Daryā-ye Nur.

Researchers engaged in the semiology of valuables, including jewels, state that of the meanings that were assigned to such objects, the most important was the change in their geographic and historical context.Footnote 95 This statement generally corresponds to reality. In the case of the Daryā, however, it was different. The key role for the perception of this diamond, which over the centuries was gifted, looted, and sold while circulating on the Indian subcontinent, in Turkey, and in Iran, was played by its appearance, interpreted, quite independently of the geographic location and context, in an identical way derived from Hindu beliefs. However, placement of the diamond in a religious context did not remove from it its supposed nefarious properties, while the radical improvement of its appearance made of it a perfect, and thereby beneficent, stone. Perfection, radiance, enormous size, and the ensuing rarity, inseparably connected with material value, was so great that it practically de-commodified the Daryā—making it a symbol of ultimate wealth, because almost permanently tied up, decided about its display as a regalium. In this role, this stone had the function of need-to-have “incarnated sign” of power, and in the time of the Qajars it was also situated in the context of dynastic propaganda; with the support of rhetoric, it became a legible instrument of political expression both in the East and in the West.Footnote 96 At that time, then, the Daryā-ye Nur began to be perceived as a symbol of millennia of the Persian monarchy and a source of national pride, which role, in my view, is still played by this most unusual of the historical Indian diamonds.