Instances of two verbs occurring in the same clause and sharing the same arguments are frequently found in colloquial Persian, but remain understudied. These verb + verb, or double verb, constructions consist of two verbs; one adds an aspectual meaning, and the other verb carries the lexical meaning and acts as the main element in the predicate. Normally the verb that acts as the aspectual verb comes before the main verb, although it sometimes follows. The verbs that act as aspectual verbs in these constructions compose a small class. The examples in (1) are formed with the verb gereftan (to take) as the aspectual verb, followed by the main verb. The verb + verb combinations are in bold.

In these sentences, although gereftan is a transitive verb in its lexical use, the combination of the two verbs has yielded an intransitive verb. Both of the verbs are inflected for tense and agreement. In (1a) the sentence is imperative, and in (1b) it is declarative. In both sentences gereftan acts as ingressive aspectual marker, focusing on the start and a sudden happening of the verb. In (2), the same aspectual verb is used with transitive verbs. Therefore, the transitivity of the sentences depends on the main verb, not the aspectual verb.

Although gereftan in the above examples appears before the main verb, raftan (to go) can appear in either the second position (3) or the first position (4). If in the second position, it adds completive aspect to the sentence, indicating that the action presented in the main verb is finished completely.

When raftan is used in the first position, it adds an ingressive aspect to the sentence, indicating that the agent is or was on the verge of starting an action.

Another verb used as ingressive aspectual verb is āmadan (to come), which always appears in the first position (5).

Two other verbs that appear in these constructions and mean a sudden and unexpected start of the second verb are gozāshtan (to put) (6) and bargashtan (to turn back) (7). Both of them appear in the first position.

Two posture verbs, neshastan (to sit) and istādan (colloquial: vāysādan, to stand up), also are used as aspectual verbs to mean that the action has a durative meaning. Although in (8a) the sentence is imperative, the action of writing a thesis is expected to take a while, and the aspectual verb has this duration in its application. This concept of duration is clearer in (8b).

In (9), the verb vāysādan is an aspectual verb that points to the ongoing process of crying:

These constructions have some peculiar characteristics. For example, not every verb can be found in these combinations; the verbs that participate compose a small class: gereftan (to take), raftan (to go), āmadan (to come), neshastan (to sit), vāysādan (to stand up), gozāshtan (to put), bargashtan (to come back), bardāshtan (to take), and zadan (to hit). This small class includes some motion and posture verbs. Another peculiarity is that the aspectual verbs can be omitted without affecting the grammaticality or the conditional truth of the sentences.

Although the double verb construction is frequently used in colloquial Persian, it is not explored properly. Windfuhr is among the few scholars who says that there is a pattern with gereftan in Persian, for example, gereft-and khābid-and (they took to sleeping/fell asleep), used mostly colloquially, with a pejorative or ironic meaning.Footnote 1 He provides examples of this construction in past tense and imperative form. However, Vafaeian writes that this construction also is used in present form and that it has a periphrastic pattern, among others, showing tense, aspect, and mood (TAM) in Persian. The present pattern is mi-V.PRS-PN, for example, mi-gir-and mi-khāb-and (they take to sleep), and the past pattern is V.PST-PN, as in gereft khāb-id (he took to sleep). She believes that this construction has not grammaticalized analogously to other periphrastic TAM constructions, but does not explain its idiosyncratic properties.Footnote 2 She also notes that this pattern may be negated by adding a negative marker to the TAM element, but, as far as I know, this construction is only able to be negated in imperative form in specific contexts, and cannot be negated in other forms.

Taleghani, writing on tense, aspect, and mood in Persian, has mentioned that there are instances of serial verb constructions (SVCs) in Persian. However, she has not referred to aspectual verb constructions.Footnote 3 Taleghani is one among the small group who argue that Persian has SVCs. In the same vein, Nematollahi argues that in Persian progressive construction with dāshtan, both the auxiliary and the main verb appear as finite verbs, that is, both of them are inflected for person and number, and this distinguishes them from other Persian periphrastic verbal constructions.Footnote 4 Lacking a proper term, she calls them SVCs. Anoushe is among those linguists who considers these sequences SVCs and argues that Persian SVCs are actually not limited to progressive but also are found with present and past perfect structures (e.g., u gerfte bud khābide bud; s/he had taken had slept).Footnote 5

Rasekh-Mahand has studied these constructions in Persian and emphasized that these constructions are not SVCs.Footnote 6 Some of his arguments are replicated and elaborated in the next section. Feiz studies āmadan (to come) and raftan (to go) and asserts that “beyond the expression of translational motion, āmadan and raftan encode aspect, subjectivity, and the speakers’ perspectives on certain elements of the events as the stories unfold in their memories.”Footnote 7

There have been some studies about Persian's TAM system, especially on the grammaticalization of auxiliaries. There have been some studies focusing on use of the progressive construction with dāshtan (to have), which argue that this construction is very new in Modern Persian, no more than a century old.Footnote 8 Jahani and Davari and Naghzguy-Kohan discuss the grammaticalization of khāstan (want) as a future tense marker,Footnote 9 and Jahani introduces the different ways of marking the prospective aspect using different auxiliaries.Footnote 10 Naghzguy-Kohan has written on grammaticalization of motion verbs in Persian, and also on auxiliary verbs and grammatical aspect in Persian.Footnote 11 There are some works dealing with grammaticalization of auxiliary verbs in Persian and with grammatical aspect and iconicity.Footnote 12 Davari also has studied the aspectual verb raftan (to go), showing that it is a completive aspect marker.Footnote 13 Korn and Nourzaei assert that in Balochi, another Iranian language, combinations of several verbs can be found. They refer to them as vector verbs. They rightly report that what they call vector verbs contain a lexical verb in combination with a verb of movement (go, come) or physical transfer (bring, seize).Footnote 14

In this paper, I have two goals. First, in the next section, I try to show that these double verb constructions in Persian are not instances of serial verb construction. Rather, these double verb constructions are aspectual verbs that mark ingressive, completive, or durative aspects. I will discuss the development of these aspectual verbs and the motivations for their emergence and grammaticalization in the third section. My second goal is to show that the usage of aspectual verbs in Persian and also the usage of dāshtan as a progressive marker have increased gradually over the last century, and that this can be seen as an ongoing change in the Modern Persian language. In the fourth section, I have used a body of work to elaborate my claim, as this corpus-based method remedies the errors of impressionistic observation.Footnote 15 The final section comprises the conclusion.

Double Verbs Are Not Serial Verb Constructions

Although some previous studies have argued that Persian is a serializing language,Footnote 16 we provide some arguments to show that the Persian double verb constructions referred to in the literature as SVCs are actually not eligible to be labeled as such. The first documentation of serialization (called by different names, such as combinations, compounds, multiple predicates, double verbs, etc.) goes back to the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries in West African languages, for instance, Akan, Ga, Ewe, and Yabem.Footnote 17 In the second half of the twentieth century, the terms “serialization” and “serial verb construction” gradually gained status and were used to refer to more or less similar constructions in different languages.Footnote 18 Although there appears to be consensus about terminology, there is not a widely accepted definition for SVCs.Footnote 19 The following are some prototypical examples of SVCs:

CantoneseFootnote 20

Bislama, English-lexified creoleFootnote 21

In spite of lack of agreement, there is a more or less standard set of criteria for identifying SVCs in the literature. Aikhenvald gives a definition for serial verbs that provides some definitive criteria: “They form one predicate, and contain no overt marker of coordination, subordination, or syntactic dependency of any other sort.Footnote 22 Such series of verbs are known as serial verb constructions, or serial verbs for short. Serial verbs describe what can be conceptualized as a single event. They are often pronounced as if they were one word. Serial verbs tend to share subjects and objects. They have just one tense, aspect, mood, and modality value—that is, one part cannot refer to past, and another to present. The components of serial verbs cannot be negated or questioned separately from the whole construction. Each component must be able to occur on its own. The individual verbs within the construction may have the same transitivity values; or the values may be different.”

The first criterion is that serialization involves two (or more) verbs in a single clause, and an SVC functions just as a monoverbal clause does in discourse.Footnote 23 It is argued that the verbs in an SVC must be independent verbs; that is, they should be able to occur on their own. Some people propose that an altered or reduced meaning of verbs in SVCs is predictable, and that the minor verb in an SVC could retain its lexical status in the language outside the SVC.Footnote 24 For these proponents, grammaticalized SVCs, for example, those that show aspectual meaning, also are considered SVCs.Footnote 25 Contrary to Aikhenvald, some linguists argue that auxiliary constructions and aspectual constructions are not SVCs.Footnote 26 Since it is widely believed that serialization exists in a cline of grammaticalization, sometimes the verbs in SVCs lose their original meaning, and they may even lose their independent status. The ability to be used independently remains as a criterion for prototypical SVCs. Haspelmath notes that an independent verb is a verb expressing a “dynamic event without any special coding in predication function and that occurs in a non-elliptical utterance without another verb.”Footnote 27 It means that auxiliaries like the English “will” in “will go” do not form SVCs. Still, Heine sees SVCs and auxiliary verb constructions as overlapping categories, and believes aspectual SVCs to be SVCs and auxiliary verb constructions at the same time.Footnote 28

The aspectual and main verbs in Persian double verb constructions can be used independently, however, although one of them keeps its original meaning, the other is semantically bleached or altered. For example, in gereft khābid ruye takht (s/he took to sleep on the bed), the second verb khābid (slept) is used in its original meaning, but the first verb gereft (took) does not have its main lexical meaning. Of course, it can be used independently with its original meaning in other utterances. Regarding the criterion of independence, it can be said that the verbs in these Persian constructions can be used independently, although one of them does not keep its original meaning in the double verb construction.

The second criterion is for an SVC to form a single clause; however, there appears to be no clear way to define just what a single clause is. A well-accepted test for this states that there is only one way to negate a clause with an SVC.Footnote 29 One of the main verbs is negated and usually has scope over all the other verbs. So, if a verb combination can be negated in only one way, it is a good SVC candidate. Persian double verb constructions show unpredictable behavior. Some of them cannot be negated most of the time (11)Footnote 30; some can be negated in imperative form (12a); and some of them cannot (12b). These differences related to negation are considered evidence that these verbs have two different roles: lexical and auxiliary.Footnote 31

Application of the negative marker as a test for singularity of clause shows that the Persian data have a mixed behavior and are negated in limited ways.

The third criterion for an SVC is the lack of any linking element (coordinator, subordinator, or complementizer) between the two verbs.Footnote 32 In some of the Persian double verb examples no linking element (coordination marker) is used (13):

However, in some other double verb constructions, a coordinator, =o (the clitic form of va [and]) can be added (14).

When the linking element is used, the sentence may refer to two successive events, in this case “take” and “tear.” When the linker is not used, the two actions do not refer to two successive actions. According to the third criterion, Persian double verb constructions are not SVCs.

The fourth criterion for SVCs is that they have no predicate-argument relation. This criterion excludes complement-clause constructions in which one of the verbs (the verb of the subordinate clause) is part of an argument of the main clause. This also excludes causative constructions (e.g., “he made her cry”), in which one of the verbs can be part of the argument of another verb. This criterion for SVCs is met by the Persian double verb constructions discussed here.

Another criterion for being an SVC is that it has only one value for tense, aspect, and mood and it is not limited to different TAM markings.Footnote 33 Persian double verb constructions share TAM values, but they have some idiosyncratic features regarding TAM marking. Although it is argued that SVCs have no tense limitation and can occur in all tenses,Footnote 34 there are some tense limitations for Persian constructions. For example, whereas some of the double verb constructions can be used in past, present, or future tense (15), some of them have limitations and cannot be used in all tenses (16):

In addition to tense limitations, there also are some aspect limitations in double verb constructions. Although some of them can be used with perfective or imperfective aspects, some of them are not used with the imperfective aspect (17):

The sixth and last criterion is that in SVCs two verbs imply a single event, which can be translated to a single verb in non-serializing languageFootnote 35, like the following example from Yoruba (18):

YorubaFootnote 36

In this example, there are two sub-events: mú (take) and wá (come). When added to each other, they form a single event (bring). However, in Persian examples, the two verbs do not make a single event; usually, one of them has the main meaning and the other one adds aspectual meaning to it. If the aspectual verb is deleted, the meaning of the main verb is not drastically altered. For example, in (19) the single event is “sleep”; in (19a) it is conceptualized by a double verb construction, and in (19b) it is conceptualized by a single verb.

In both of the sentences, the event, sleep, is the same. One verb, khābidam, shows the main event; the other verb, gereftam, adds ingressive meaning to it, but not as a sub-event.

In sum, Persian double verb construction cannot be considered a prototypical SVC. Of the six criteria, only one of them (the no predicate-argument relation) applies to Persian examples. The other five tests fail to approve the serial status of these verbs. The Persian double verb constructions are far from being examples of (prototypical) SVCs. In particular, they are not sub-events of a single event, which is the defining and intuitive criterion of an SVC.Footnote 37

Grammaticalization of Aspectual Verbs

In this section, I give an account of the morphosyntactic and semantic features of the aspectual verb construction in Persian, focusing on the aspectual meaning each verb adds to the sentence and its idiosyncratic features. This construction is compared with the established aspectual verb, dāshtan (to have), which marks the progressive aspect in Persian. The difference between double verb constructions and dāshtan constructions demonstrates that double verb constructions are on the path of grammaticalization, sometimes appearing in a context with two readings, lexical and aspectual, and sometimes appearing with only an aspectual meaning. This analysis provides another piece of evidence for one of the functionalists’ assumptions: that categories are less than discrete and categorization is an ongoing process.Footnote 38

There are idiosyncrasies of aspectual verb constructions, and the verbs participating in these constructions have different semantic and syntactic features. They also show different kinds of lexical aspects. In the first subsection, I describe these individual features and refer to their lexical counterparts in different texts, demonstrating how their meaning and grammar change when moving from lexical status to aspectual verb status. In the following subsection, I discuss the grammaticalization factors involved in aspectual verb constructions. Givón's cyclic wave from discourse pragmatics to zero (Discourse > Syntax > Morphology > Morphophonemics > Zero), is used to show how discourse leads to emergence of aspectual verb constructions over time.Footnote 39 We have tried to show that the semantics, frequency, and context of minor verbs in aspectual verb constructions are three main factors behind the grammaticalization of these periphrastic aspectual verbs.

Morphosyntactic and Semantic Features of Aspectual Verbs

The experts are not in full agreement on the definition of “auxiliaries” in a single language or among languages, however there is a consensus that their behavior differs from main verbs. Auxiliary verbs are neither clearly grammatical nor absolutely lexical, comprise a closed set of linguistic elements, and mainly express tense, mood, and aspect.Footnote 40 Although some verbs act solely as auxiliaries, most of them have lexical counterparts as well, making it more difficult to distinguish between their different functions.Footnote 41 In Persian, too, TAM categories are represented both morphologically (by bound morphemes or verb inflections) and periphrastically (by syntactic forms or auxiliaries).Footnote 42 Some of the periphrastic constructions are used to mark tense (khāstan, or to want); the passive case (shodan, or to become); the impersonal (bāyad, or should, and shodan or to become); and modality (bāyad or should, shāyad or might, and tavānestan or to be able to, can). However, there are some aspectual verbs, too. One of them is dāshtan (to have), which shows a progressive aspect.Footnote 43 I will show in this section that the double verb construction discussed in this paper also is a periphrastic aspectual verb, and that each of the minor verbs has morphosyntactic and semantic features.

The dāshtan construction shows different degrees of semantic bleaching and loss of syntactic independence. Originally, dāshtan meant “hold,” “keep,” or “dwell”; now, in its lexical use, it means “to have” (20).

However, dāshtan is semantically bleached and has grammaticalized into an auxiliary verb. It functions primarily as a progressive aspect marker in durative situations.Footnote 44 Estaji and Bubenik call it an “innovative construction” in written documents that go back to one hundred years ago “when writers felt free to enter the elements of colloquial Persian into their writings.”Footnote 45 Windfuhr and Perry believe that “the progressive is not yet fully integrated into literary Persian.”Footnote 46 This innovative progressive construction in Persian is formed by “the auxiliary verb dāshtan and a dynamic, non-punctual verb in the present or past tense marked with the imperfective or declarative marker mi-, as in (21).Footnote 47

Vafaeian argues that dār/dāshtan in present and past form, followed by the main verb in the imperfective, is a periphrastic progressive construction in colloquial Persian, which can occur only in the indicative and imperfective, cannot be negated, and can occur in passive construction.Footnote 48 The dāshtan always precedes the main verb, although objects or prepositional phrases may intervene between them. She adds that this verb is semantically completely bleached; and in the dāshtan construction both verbs are inflected for tense, person, and number, as shown in (21). It is an interesting point that dāshtan always occurs with the prefix mi- as an obligatory element, encoding progressive aspect. Vafaeian asserts that removal of dāshtan verb from examples like (21) leaves the sentences as present indicative and past imperfective, respectively.Footnote 49 However, it is argued that prefix mi- also can express the progressive aspect on its own, as in (22b):Footnote 50

What is the role of dāshtan in Persian progressive construction? Davari and Naghzguy-Kohan point out that there is ambiguity because of declarative and progressive uses of mi-, since mi- is a marker of declarative mood in Persian as well.Footnote 51 It means (22b) could be a factual statement on the speaker's ability to drive. Whenever dāshtan is used, it disambiguates the sentence in favor of a progressive interpretation. Out of context (22b) is used primarily to state a fact. But when dāshtan is used, it signals an incomplete action or state in progress. Vafaeian argues that this construction is mainly used to refer to a focalized point, that is, a specific time at which the event referred to is ongoing (mozāhem nasho, dāram film mibinam [do not disturb, I am watching a movie]).Footnote 52 But it also is used in other contexts: durative, that is, the event is related to an extended period of time (zamin dāre be dore khorshid migarde [the earth is moving around the sun]); proximative (ghatār dāre mire [the train is about to leave])Footnote 53 futurate (Maryam fardā dāre mire [Maryam is going tomorrow]); iterative (dāre mizanash [he is hitting him]), and absentive (–nimā khune ‘ast? –na, dāre varaghbāzi mikone [–Is Nima at home? –No, he is playing cards]). So, it could be concluded that dāshtan is a polyfunctional aspectual verb.

Now, if we consider double verb constructions, it can be observed that their behavior is not odd when compared to the dāshtan construction. First, the aspectual verbs participating in these constructions have lost their original lexical meaning and are semantically bleached. Second, it is not odd that some of them have agreement markers, since this is the normal trend in Persian auxiliaries, as observed with the dāshtan construction (and also with the khāstan construction).Footnote 54 Below, some features of double verb constructions are described.

The motion verb raftan (to go), appearing in the second position in double verb construction, implies a completed situation, which may be unexpected, unwanted, or done without the agent's volition (23).

The important point about raftan in this construction is that it has lost agreement with the subject and is used only in third person singular form, regardless of the subject of the sentence (here it is first plural), and it can only be used in past declarative sentences.Footnote 55 Therefore, this verb is not only semantically bleached but also is grammatically defective, showing a noticeable degree of grammaticalization. When omitted, the main meaning of the sentence remains untouched, but these secondary meanings are erased (24).

In some of these double verb constructions, the main verb can appear in infinitive form. In this case, the aspectual verb cannot be deleted since it carries the tense and agreement markers of the predicate.

The aspectual verbs in double verb constructions, apart from raftan, which in the second positions adds a completive aspect to the sentence, can be grouped into two classes: those which show a sudden, unexpected action, focusing on its start, and those which show an ongoing action for a period of time. Generally, the first group adds an ingressive aspectual meaning to the verb, and the second group a durative aspect.

Most of the minor verbs fall in the first group: gereftan (to take); raftan (to go, in the first position); āmadan (to come); gozāshtan (to put); bargashtan (to come back); bardāshtan (to pick up); and zadan (to hit). These verbs add an ingressive or inchoative aspect to the sentence in varying degrees. If the verb is omitted, this meaning is erased. For example, in (26a), the verb zadan shows that the action raftan has happened unexpectedly, emphasizing its beginning, whereas in (26b), by its omission, this unexpectedness is absent and the start of the action is not expressed.

Two posture verbs, neshastan (to sit) and vāysādan (to stand up), add a durative aspect to a sentence. The main verbs that appear with these verbs are durative and cannot be instantaneous. For example, in (27a) the verb neshast emphasizes the continuity and repetition of crying, but when it is omitted in (27b) this meaning is not clearly present.

We can conclude this section by summarizing the features of Persian periphrastic aspectual verbs. Among the periphrastic aspectual verbs, dāshtan (to have) has lost its original meaning in auxiliary construction, although it has kept its lexical meaning in other contexts. It has lost part of its syntactic independence but has kept its agreement markers and can be used with different verbs as an auxiliary, showing a progressive aspect. In the double verb construction, some variation is observed. The verb raftan has lost its lexical meaning and most of its grammatical conjugations in the final position, adding a completive aspect to the main verb. Some of the verbs can be used with an infinitive verb, and although they have lost part of their syntactic independence—e.g., a transitive verb, gereftan, is used intransitively in some contexts—they still receive agreement markers. Moreover, they are used as aspectual verbs selectively, not with all kinds of verbs or in different contexts, indicating that on their path to grammaticalization they have not lost their meaning or syntactic independence completely. In addition to a completive aspect, they broadly fall into two groups, one group showing an ingressive and the other a durative aspect.

Forces behind the Grammaticalization of Aspectual Verbs

There have been a lot of studies concerning the grammaticalization of auxiliary verbs, or auxiliation.Footnote 56 Heine emphasizes that “any explanatory model that does not take the dynamics of linguistic evolution into consideration is likely to miss important insights into the nature of auxiliaries.”Footnote 57 It is generally argued that auxiliaries lose some of their verbal features in the course of auxiliation, and some categorical indeterminacy arises because the auxiliary use often splits from the original lexical verb. Therefore, although a main verb retains its lexical meaning and function, it can coexist with a homonymous auxiliary verb (such as “do,” “be,” and “have” in English).Footnote 58

Heine asserts that there are different factors that push grammaticalization, such as context; frequency of use; reasoning processes (inferencing); mechanisms of transfer (metaphor, metonymy, etc.); directionality (abstraction or concretization); and semantic implications (bleaching, generalization).Footnote 59 He emphasizes that the process from A (source, lexical) to B (target, grammatical) is a continuous one, with a number of intermediate stages. Among these intermediate stages, there is a switch context stage, which is the product of an interaction of context and conceptualization that leads to the rise of new grammatical meanings. The switch contexts have two readings, one lexical and one grammatical, whereas the target form is primarily grammatical. Examples from the Persian language show that the aspectual verbs in double verb constructions are used as lexical verbs in other constructions (source context). Sometimes when the aspectual verb appears beside another verb two readings are possible, the original lexical meaning and a grammatical one. These contexts are switch contexts. When in target form, they are more grammaticalized, having lost their original meaning and much of their syntactic independence. This process shows that context can act as a grammaticalization factor in the development of aspectual verbs. For example, the sentences in (28) show that the verb gereftan is used in different contexts with different functions.

The verb gereftan, which in its lexical use is a transitive verb, appears as a single lexical verb in (28a), showing its lexical meaning and transitivity. It has kept its lexical meaning and transitivity in (28b), where it is used before another verb, borid (to cut), but its meaning is slightly bleached, and another weak reading has appeared, which could mean “he suddenly cut his head.” Additionally, gereftan could be omitted in this reading. This is the switch context, a context with two readings. In (28c), gereftan is not used as a transitive verb; there is a coordinate marker between this verb and the following verb, raftand. In this sentence, the coordinate marker does not show two separate actions, and it can be omitted. This is another step toward the target stage. Finally, in (28d), the verb gereftan has lost its lexical meaning, it is not used as a transitive verb, and there is no coordinate marker between the two verbs, showing that gereftan has turned into an aspectual verb. This is the target form. These examples demonstrate the existence of switch contexts and the importance of context in grammaticalization.

The examples in (29) demonstrate the same situation for the motion verb āmadan (to come). They also show that it moves from a lexical meaning to a grammatical meaning in a double verb construction.

The verb āmadan, an intransitive lexical verb, appears in (29a) as the source context. In (29b), it is used as the main verb of the matrix clause, connected to the subordinate clause with the complementizer ke (that), while at the same time it moves away from the lexical meaning and indicates intention. This is a switch context that has two readings. In (29c), āmadan appears with another verb in the same clause, with a prepositional phrase separating them, and in the last example (29d) āmadan is used to mean to begin or intend an action, adjacent to another verb, raghsidan (to dance). These examples show that, although this verb has kept its lexical meaning, it has moved away from its original meaning and has acquired a more grammatical function in other contexts.

We have examined a mini-corpus of some written stories from the last one hundred years of the Persian language in search of switch contexts and target meanings of aspectual verbs. We have selected three books from each decade from the 1920s to the 2020s, and from each book 3,000 words were selected, or 12,000 words from each decade and 120,000 words in sum (see the appendix for the list of books). Table 1 shows the percentage of switch contexts and aspectual function (target meaning) for some of the verbs.

Table 1. Aspectual function and switch contexts.

The data in Table 1 show that all tokens of dāshtan as a non-lexical verb are as an aspectual verb, and there are no switch contexts with two readings. Therefore, this verb has reached the target meaning. However, the other aspectual verbs appear in switch contexts to different degrees, such as gozāshtan appearing as an aspectual verb in 57 percent of the tokens, and raftan in 24 percent of the tokens. To summarize, in double verb constructions, the aspectual verbs are on the pathway to grammaticalization, showing switch contexts to different degrees.

To put the Persian aspectual verb construction into a wider typological, functional framework and provide explanations for its emergence, one can ask why some specific verbs take part in this construction, and what semantic or pragmatic peculiarities force them to be part of this construction. Heine clarifies that in the grammaticalization of auxiliaries, the linguistic expressions are derived from concrete entities that describe general notions like location, motion, activity, and posture.Footnote 60 As observed, aspectual verbs are related to semantic notions: motion and caused motion verbs (raftan [to go]; āmadan [to come]; bargashtan [to come back]; gereftan [to take]; gozāshtan [to put]; and zadan [to hit]) and posture verbs (neshastan [to sit] and istādan [to stand]).

Bybee and her colleagues argue that motion verbs like “go” and “come” are part of the grammaticalization process as they appear in much wider contexts and are not specific to the nature of movement, as “walk,” “stroll,” “swim,” or “walk” would be, for instance.Footnote 61 The Persian motion verbs that occur in aspectual verb construction also are limited to a general movement process. The more generalized motion verbs like raftan (to go) and āmadan (to come) lack specific features of movement and are appropriate in much wider contexts, and, at the same time, occur more frequently. After grammaticalization, the meaning that remains “is very general and is often characterized as abstract or relational.”Footnote 62 For example, although “go” in its lexical meaning needs a true subject that is moving on a path to a goal (e.g., “Jack goes to his office by bike”), in the case of “be going to,” the subject is moving toward a particular endpoint in future (e.g., “That milk is going to spoil if you leave it out”).Footnote 63 The same holds true in Persian. For example, āmadan (to come), in its lexical use, needs a subject that moves on a path toward the speaker (30a), but in its use in aspectual verb construction it does not imply a real movement, but instead means to begin a process or change a state (30b):

In fact, motion verbs are concrete verbs, referring to the relation between body and space (embodiment). In the grammaticalization process, the space dimension is deleted and the time dimension is kept.

A location schema is most commonly used for progressive aspects.Footnote 64 In Persian aspectual verb construction, two posture verbs (showing location), neshastan (to sit) and istādan (to stand), can be used to show progressive aspect as well, as in (31) and (32):

The sentence in (31) does not mean that “reading” is going on now, but it has the color of an ongoing action that the subject is doing nowadays. In (32), the event seems more related to the present time and has the color of an action that is done when it is unexpected. So, although these verbs are not the usual verbs used for the progressive aspect in Persian (dāshtan + verb is the usual method, as discussed in different sections of this paper), when used in aspectual verb construction they show a kind of progressive aspect. It can be concluded that one reason certain verbs participate in aspectual verb constructions is their semantics. Motion and posture verbs are among the typologically widespread verbs that grammaticalize frequently.

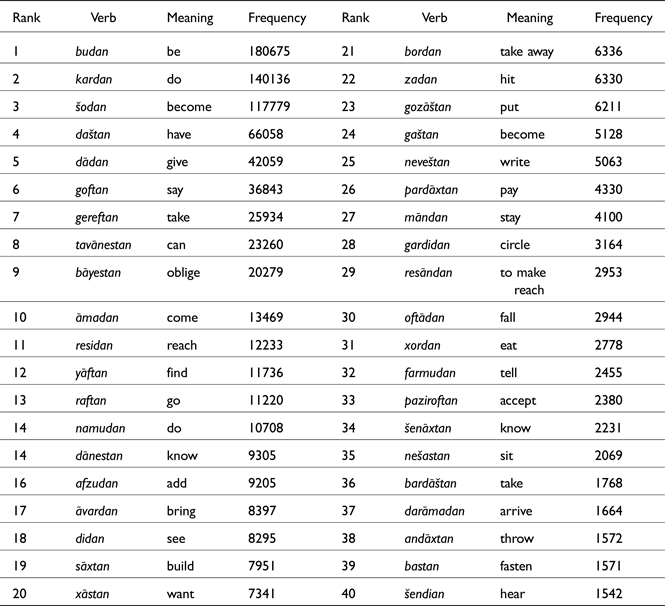

Apart from context and semantic classes of verbs in aspectual verb construction, their frequency can be another reason for grammaticalization. Frequency is not only the result of grammaticalization, but also acts as the initiator of grammaticalization.Footnote 65 Krug, studying the emergence of modal verbs in English, argues that “there is a tantalizing correlation between high frequency and auxiliary status: among the top thirty verbs almost half enjoy auxiliary status.”Footnote 66 Table 2 surveys the discourse frequency of the forty most common Persian lexical and auxiliary verbs, based on a corpus of one million words from different written and spoken texts:

Table 2. The forty most frequent verbs in Persian. Source of data: Bijankhan and Mohseni, Frequency Dictionary, 381.

Understanding the relationship between the discourse frequency and the grammatical status of the most frequently appearing verbs is of value. It is interesting that most of these verbs have lost a part (or all) of their syntactic independence and lexical meaning and have undergone grammaticalization. The verbs participating in aspectual verb construction (in bold in Table 2) also are among the most common Persian verbs: dashtan, gereftan, āmadan, raftan, zadan, gozāshtan, and neshastan. Therefore it can be argued that the discourse frequency of verbs participating in aspectual verb construction is another factor which pushes them to act as aspectual markers and become grammaticalized.

Conclusion

The double verb constructions studied in this paper are not serial verb constructions, but they are aspectual verb constructions in which an aspectual verb adds a completive, ingressive, or durative aspect to the main verb. These aspectual constructions have different morphosyntactic and semantic features, and some of them are more grammaticalized than others. Different factors push them toward being more grammatical, among which context of use, semantic classes of verbs, and frequency are notable. These verbs are motion and posture verbs that are among the most frequently used Persian verbs.

Appendix

Al-e Ahmad, Jalal. Modire Madrese [The headmaster]. Tehran: Majid, 2019.

Alavi, Bozorg. Chamedān [The suitcase]. Tehran: Negāh, 2020.

Alavi, Bozorg. Sālārihā [Salar family]. Tehran: Amirkabir, 1978.

Behrangi, Samad. Olduz va Kalāqhā [Oldouz and crows]. Tehran: Givā, 2021.

Chobak, Sadegh. Sange Sabur [A good listener]. Tehran: Javidān, 1976.

Dehkhoda, Ali Akbar. Charando Parand [Fiddle-faddle/nonsense]. Tehran: Niloofar, 2016.

Dolatabadi, Mahmoud. Āhuye bakhte man Guzal. [My beloved, Guzal]. Tehran: Cheshme, 1988.

Dolatabadi, Mahmoud. Bani Adam [Adam's Sons]. Tehran: Cheshme, 2021.

Dolatabadi, Mahmoud. Ruzegāre separi shodeye mardome sālkhorde [The days of old people]. Tehran: Cheshme, 1993.

Ebrahimi, Nāder. Masaba va Royāye Gājarāt [Gājarāt's dreams]. Tehran: Ruzbahān, 2012.

Etemadzade, Mahmoud. Dokhtare Ra'yat [Peasant girl]. Tehran: Donyāye no, 2005.

Golshiri, Houshang. Shāzde Ehtejāb [Prince Ehtejāb]. Tehran: Ghoghnus, 1978.

Hedayat, Sadegh. Parvin dokhtare sāsān [Parvin, daughter of Sasan]. Tehran: Amirkabir, 1962.

Hedayat, Sadegh. Sage Velgard [Stray dog]. Tehran: Amirkabir, 1942.

Jamalzade, Mohammad Ali. Rāh Āb Nāme [The fountain way]. Tehran: Maʾrefat, 1690.

Jamalzade, Mohammad Ali. Saro tah ye karbās [The same]. Tehran: Elm, 2020.

Kazemie, Eslam. Ghesehāye Shahre Khoshbakhti [Tales of the city of happiness]. Tehran: Roz, 1976.

Mahmoud, Ahmad. Hamsāyehā [The neighbors]. Tehran: Amirkabir, 1978.

Mahmoud, Ahmad. Madāre Sefr Daraje [The zero degree latitude]. Tehran: Moin, 2018.

Mastoor, Mostafa. Ruye Māhe Khodā rā bebus [Kiss the face of God]. Tehran: Markaz, 2020.

Mazinani, Mohammad Kazem. Shāhe bi Shin [The king without K]. Tehran: Sureye Mehr, 2017.

Mo'adabpoor, M. Parichehr [Parichehr]. Tehran: Nasle No Andish, 2020.

Nafisi, Sa'id. Setāregāne Siyāh [Black stars]. Tehran: Ferdous, 2012.

Nazerzade Kermani, Ahmad. Shirzād ya Gorge Jāde [Shirzad, or road wolf]. Tehran: Ebne Sinā, 1958.

Parsipoor, Shahrzad. Tubā va Ma'nāye Shab [Tuba and the meaning of night]. Tehran: Asparak, 1989.

Pirzad, Zoya. Cheraghhā rā man Khāmush mikonam [I turn off the lights]. Tehran: Markaz, 2020.

Roknzade Adamiyat, Mohammad Hossein. Dalirāne Tangestāni [Tangestanis braves]. Tehran: Eghbāl, 1973.

Shojaei, Mehdi. Keshti Pahlu Gerefte [The moored ship]. Tehran: Neyestān, 2020,

Taraghi, Goli. Do Donyā [Two worlds]. Tehran: Niloofar, 2018.

Yoshij, Nima. Marqade Āqā [The master's shrine]. Tehran: Marjān, 1970.

Mohammad Rasekh-Mahand is a professor in the Department of Linguistics, Bu-Ali Sina University, Hamedan. His research focuses on Persian syntax and typology of Iranian languages.

Mehdi Parizadeh is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Linguistics, Bu-Ali Sina University, Hamedan. His current research is on the morpho-syntactic changes of New Persian.