Management Implications

Lehmann lovegrass (Eragrostis lehmanniana Nees) presents a high risk to biodiversity, impacting rangeland productivity. This species is rapidly increasing its populations and plant density in the semiarid grasslands of Chihuahua. Even though some official institutions have undertaken a few rangeland rehabilitation actions, follow-up has been a component missing from these strategies, limiting their success. In the region, there exist large grassland areas where E. lehmanniana is the main species, covering more than 90% of the surface area. Although invasive species can generate enough vegetation cover, contributing to soil retention, these species replace native vegetation and cause changes in soil pH, nutrients, microorganisms, and loss of genetic diversity, among other negative effects in ecosystem services. Based on that, the recovery of these ecosystems is difficult to achieve by only ceasing cattle grazing. Thus, new research is needed to cope with the current situation of those rangelands of Chihuahua that are currently invaded by E. lehmanniana and to generate useful knowledge for rangeland restoration. In this study, seedbed preparation with unconventional tillage implements and the seeding of a grass mixture was proposed as an alternative to reduce E. lehmanniana populations and contribute to recovery of semiarid rangeland productivity. In Mexico, the efforts for ecological restoration of invaded grasslands are limited. This study aims to motivate the ranchers, the government, the researchers, and the rest of society involved in recovery efforts of semiarid grasslands to keep fighting against E. lehmanniana invasions either through mechanical or biological control.

Introduction

The grassland biome covers approximately 37% of the planet’s surface (O’Mara Reference O’Mara2012). However, most of it faces serious degradation problems. According to Gang et al. (Reference Gang, Zhou, Chen, Wang, Sun, Li and Odeh2014), 49.2% of worldwide grasslands are in poor condition, mainly due to overgrazing. The consequences of this practice have been loss of soil fertility, loss of native plant diversity, invasion by undesirable species, and a decrease in quantity and quality of feed for livestock and wildlife. In turn, the change in the vegetation structure has affected habitat quality for birds, small mammals, and invertebrates, among other fauna (Hickman et al. Reference Hickman, Farley, Channell and Steier2006; Scasta et al. Reference Scasta, Engle, Fuhlendorf, Redfearn and Bidwell2015). The grasslands of northern Mexico are no exception: land cover by high-quality forage grasses has been reduced, mainly due to overgrazing and inappropriate grassland management (Carbajal-Morón et al. Reference Carbajal-Morón, Manzano and Mata-González2017; Manzano et al. Reference Manzano, Navar and Pando-Moreno2000).

An exotic invasive species that has invaded large grassland areas in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico is Lehmann lovegrass (Eragrostis lehmanniana Nees) (Carrillo et al. Reference Carrillo, Arredondo, Huber-Sannwald and Flores2009; Flanders et al. Reference Flanders, Kuvlesky, Ruthven, Zaiglin, Bingham, Fulbright, Hernández and Brennan2006). According to Schussman et al. (Reference Schussman, Geiger, Mau-Crimmins and Ward2006), in southeastern Arizona and western New Mexico, this species covers around 71,843 km2, with high potential to invade all the central grasslands of Chihuahua Mexico. Eragrostis lehmanniana is established mainly in open grasslands, creating monotypic stands and displacing native grasses, thereby reducing diversity of flora and fauna and, consequently, rangeland productivity (Biedenbender and Roundy Reference Biedenbender and Roundy1996; González-García et al. Reference González-García, Sánchez-Maldonado, Sánchez-Muñoz, Orozco-Erives, Castillo-Castillo, Martínez-De la Rosa and González-Morita2017). Lands invaded with E. lehmanniana have experienced reductions in water infiltration and increments of evaporation (Moran et al. Reference Moran, Scott, Hamerlynck, Green, Emmerich and Collins2009). Once established, E. lehmanniana generates a disequilibrium in the food chain, ecological structure, and habitat quality for other organisms (Murray and Philips Reference Murray and Philips2010; Sánchez Reference Sánchez2009). Under such conditions, native grasses with a good forage value often fail to successfully revegetate areas where they have been displaced (Alpert Reference Alpert2006; Biedenbender and Roundy Reference Biedenbender and Roundy1996; Corrales-Lerma et al. Reference Corrales-Lerma, Morales-Nieto, Melgoza, Sierra, Gutiérrez and Zamora2016). In this sense, the invasion of E. lehmanniana is of great concern for environmentalists and land managers in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico.

The U.S. Soil Conservation Service introduced E. lehmanniana and weeping lovegrass [Eragrostis curvula (Schrad.) Nees var. Ermelo] for erosion control in Arizona. Eragrostis curvula was established for higher and colder areas (Crider Reference Crider1945). Currently, E. curvula is considered a noxious weed in the states of Arizona and New Mexico; however, this species is far from having the invasive capacity of E. lehmanniana, whereas the former is distributed in areas with altitudes between 1,500 and 2,000 m, the latter is better adapted to altitudes between 900 and 1,400 m (USDA 2014). Due to past adverse experiences with introduced grasses, there may be few arguments to recommend exotic species for the rehabilitation of degraded grasslands. One example may be some exotic species that do not show invasive behavior being used for biological control. This is the case of the Morpa, Ermelo, and Imperial varieties of E. curvula. In Mexico, these varieties are not considered invasive. The National Seed Inspection and Certification Service (SNICS) of Mexico accepted the registration of ‘Llorón Imperial’ as the first variety of E. curvula developed by the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Agricolas Forestales y Pecuarias (INIFAP). Some of the outstanding characteristics of this variety are drought tolerance, adaptation to saline soils, and good palatability for livestock (Beltrán et al. Reference Beltrán, García, Loredo, Urrutia, Hernández and Gámez2018). Other INIFAP researchers have also recommended the varieties Morpa and Ermelo for their use in rangeland revegetation (Bravo et al. Reference Bravo, Sáenz, Barrera, Medina, Mendoza, Prat and García2011). In Australia and Argentina, E. curvula has also been recommended for use in degraded grasslands (Guevara et al. Reference Guevara, Estevez, Stasi and Le Houérou2005; Silcock et al. Reference Silcock, Finlay, Loch and Harvey2015). Thus, E. curvula var. Ermelo could be used as a biological control to reduce plant density in semiarid grasslands of northern Mexico invaded with E. lehmanniana.

In recent years, some revegetation programs have been undertaken to rehabilitate degraded grasslands. For that, conventional shallow-tillage implements with a soil removal capacity of less than 35-cm depth have been commonly used. These include harrows, plows, dibblers, ridgers, subsoilers, and simple aerator rollers (Américo and Hossne Reference Américo and Hossne2004; Gruver and Wander Reference Gruver and Wander2020; Kukal Reference Kukal and Verheye2010; Loredo Reference Loredo2005; Sierra et al. Reference Sierra, Ramírez and Gutiérrez2014; Tagar et al. Reference Tagar, Adamowskib, Memona, Cuong, Mashoria, Soomrod and Bhayo2020). Each of these conventional tillage implements prepares a seedbed differently, with the processes of germination, development, or establishment of the species used for revegetation being favored (Butler et al. Reference Butler, Stein, Pittman and Interrante2016; Sadeghpour et al. Reference Sadeghpour, Hashemi, DaCosta, Jahanzad and Herbert2014). Regardless of their efficiency, farming implements were not designed to work on natural grasslands. However, the use of deep-tillage implements awakens biological activity due to aeration (Alzugaray et al. Reference Alzugaray, Vilche and Petenello2008). In addition, deep tillage on lands with low- or zero-humidity levels affects the deep roots of vegetation and reduces the possibility of their recovery. Thus, this action can be used to eliminate undesired grasses, which are difficult to eradicate. Tillage must be complemented with a mixture of seeds that can compete in the short term and gradually reduce or eliminate undesired vegetation (IMTA et al. 2007; Spain et al. Reference Spain, Navas, Lascano, Franco, Hayashi, Tothill and Mott1984; USDA 2014).

There is a need to generate new knowledge about the effects of preparing seedbeds with different tillage implements for the recovery of the invaded grasslands of northern Mexico and to restore their productivity. In addition, little is known about unconventional tillage implements that have been used in large areas of natural grasslands for their revegetation. Likewise, information about the grass species to use for decreasing E. lehmanniana populations in Chihuahua is limited. The grasses that are used for grassland revegetation must have an acceptable palatability for livestock and wildlife. This is especially important for introduced species, because consumption is the main inhibitor of plant invasion. The objective was to evaluate seedbeds prepared with unconventional tillage implements and seeded with a mixture of grasses to reduce the plant density of E. lehmanniana and increase the productivity of an invaded semiarid grassland of Chihuahua, Mexico.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

The study was conducted at La Campana experimental ranch, in Chihuahua, Mexico. The ranch in run by INIFAP and is located 80 km north of Chihuahua City (29.2669444°N, 106.3572222°W) at an altitude of 1,550 m. The mean annual temperature of the ranch fluctuates between 12 and 17 C, and its historic annual precipitation is 355 mm. The soils of the area are of alluvial origin with a sandy loam texture and a pH ranging from 5.3 to 6.6 (Royo and Lafón Reference Royo and Lafón2008; Royo and Melgoza Reference Royo and Melgoza2001). During the study (2012 to 2015), temperature and precipitation data were obtained from databases of the weather station located at the La Campana experimental ranch and the INIFAP R. Flores Magón weather station. The latter is the closest to the experimental ranch in a location having similar climatic characteristics. In addition, the monthly average precipitation in La Campana, estimated from records for 33 yr (1982 to 2015), was reported.

The study area was of approximately 125 ha with land cover lower than 50%. It had a grass population considered as homogeneous, dominated by E. lehmanniana (90%), presenting overgrazing issues and a scarce presence of native grasses. The whole area was divided into five plots of approximately 25 ha each, where the four treated seedbeds were randomly assigned and a fifth plot without tillage was designated as a control. These large plots served to simulate rehabilitation techniques in a real-world scenario, as it occurs in large expanses of semiarid regions of Chihuahua. Before the rainy season of 2012, four plots were prepared and seeded using different unconventional tillage implements designed by Wilcox Agri-Products (Walnut Grove, CA, USA). These tillage implements are considered unconventional because they were specifically designed and assembled for their use in the rehabilitation of degraded grassland areas in Chihuahua. The designs followed the specifications from the Government of Chihuahua State, the National Commission for Arid Zones (CONAZA), and researchers from INIFAP. The entire study area was excluded from grazing for the duration of the experiment.

Unconventional Implements and Seedbed Preparation

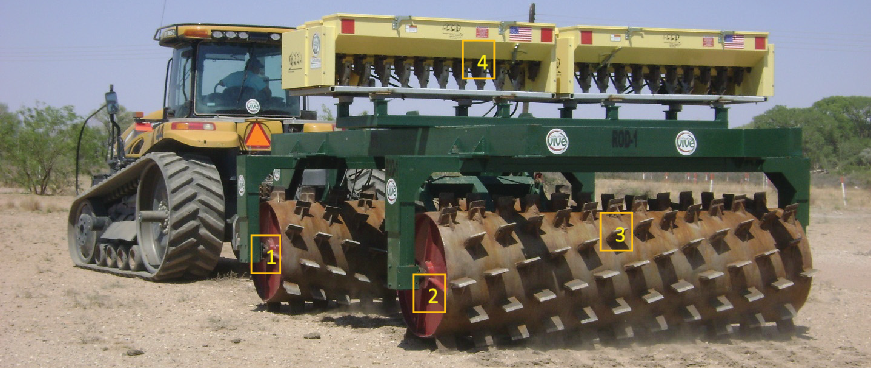

For the preparation of the Striped Harrowing seedbed, the implement used was a modified Rangeland Harrow (Figure 1). This implement was assembled with three main components in sequence, covering a cutting width of 6 m. The first component installed upfront consisted of a V-shaped harrow with 29 toothed disks. Each disk measured 88.9 cm in diameter and weighed approximately 257 kg, with a penetration capacity of 35 cm or deeper into the ground. The second component was a softener ring roller, which was used as a leveler and ground softener. The third component was a seed cover roller. The second and third components were 6-m wide and 0.41 m in diameter. The two rollers were installed with 1-m spacing between them. The last component was a seeder installed in between the two rollers, spanning the cutting width of the implement. The seedbed was prepared with this tillage implement by alternating a 6-m-wide band of tilled soil and leaving another 6-m-wide band of nontilled soil as a runoff area.

Figure 1. Rangeland Harrow implement used for seedbed preparation on semiarid grasslands. (A) Front side image and (B) rear side image. 1, V-shaped disks; 2, softener ring roller; 3, seed cover roller; 4, Truax seeder.

The Rangeland Harrow was also used to prepare the Full Harrowing seedbed. However, runoff areas were not created, and tillage occurred across the entire plot.

The Deep-Stingray Subsoiler seedbed was prepared with the Rangeland Rehabilitator, which included four main components assembled in sequence, covering a cutting width of 12 m (Figure 2). The first component installed upfront consisted of four rippers with stingray-type blades, which had a soil penetration capacity deeper than 50 cm. The second component included four 1.2-m-wide toothed crumbling rollers with V-type toothed disks. The third component consisted of four 1.0-m-wide softener ring rollers, which were used as levelers and ground softeners. The fourth component consisted of four 1.0-m-wide seed cover rollers. The last component was the seeder, which was installed in between the third and fourth components, spanning the cutting width of the implement (Figure 2). Each component prepared a different seedbed, which consisted of a 1.0-m-wide band of tilled soil and a 2.0-m-wide band of runoff area.

Figure 2. Rangeland Rehabilitator implement used for the Deep-Stingray Subsoiler seedbed preparation on semiarid grasslands. (A) Front and side view and (B) rear side view. 1, ripper stingray type; 2, crumbling roller; 3, softener ring roller; 4, seed cover roller; 5, Truax seeder.

To make the Double-Digging Aeration seedbed, the tillage implement used was a Tandem-type Aerator Roller consisting of two 3.6-m-wide iron cylinders, each covered by 144 aerator blades of 15 by 15 cm, which generated 24 holes m−2. The seeder was installed in between the two cylinders, spanning the cutting width of the implement (Figure 3). The prepared seedbed did not include runoff bands.

Figure 3. Tandem-type Aerator Roller implement used for the Double-Digging Aeration seedbed preparation on semiarid grasslands. 1, front cylinder; 2, rear cylinder; 3, aerator blades; 4, Truax seeder.

A 525 hp Challenger tractor (Challenger, Lincolnshire, UK) was used to pull all implements. In addition, the seeder used in each implement was a hydraulically driven Truax 800 (Truax Company, New Hope, MN, USA). Each seeder was calibrated to ensure a uniform distribution of the seed mixture.

Seed Mixture and Seed Density Used

The seed mixture was composed of the following native species: blue grama [Bouteloua gracilis (Willd. ex Kunth) Lag. ex Griffiths var. Hachita] (25%), sideoats grama [Bouteloua curtipendula (Michx.) Torr. ‘6107 Kansas’] (25%), green sprangletop [Leptochloa dubia (Kunth) Nees var. Van Horn] (5%), E. curvula var. Ermelo (40%), and Columbus grass [Sorghum almum Parodi] (5%; Table 1). Sorghum almum was added as a nurse plant to favor the emergence of the other seeded grasses. The seeding density used per species was based on recommendations from previous research (Bavera and Peñafort Reference Bavera and Peñafort2005; Beltrán et al. Reference Beltrán, Loredo, García, Hernández, Urrutia, Gámez, González and Núñez2009; Morales et al. Reference Morales, Royo and Lara2010). In each prepared seedbed, 5.26 kg of seed was applied as pure live seed per hectare (PLS ha−1). The amount of seed used in the mixture was adjusted based on the percentage of PLS per species, which was reported in the supplier’s warranty label.

Table 1. Amount of seed by grass species used in a mixture for seeding prepared seedbeds with unconventional tillage implements at La Campana experimental ranch (Chihuahua, Mexico).

a kg PLS ha−1, kilograms of pure live seed per hectare.

Sampling

To estimate the minimum sample size, a presampling (n = 35) was carried out. Quadrats measuring 1 m2 (1 by 1 m) were used as the sample unit to estimate the population mean and variance and then used in the formula for homogeneous finite populations (Aguilar-Barojas Reference Aguilar-Barojas2005).

Due to the homogeneity of the vegetation, the sample size yielded a minimum of 115 samples for the study area. Then, a total of 120 samples were collected to strengthen the sampling. This consisted of 24 quadrats for each plot. Three samplings were carried out in the maturity–dormancy phenological stage; the first was performed during the second year after seeding (December 2013), while the second and third samplings were performed during the third and fourth years after seeding (December 2014 and December 2015), respectively. Four approximately 50-m-long transects were distributed in each seedbed across its width. At each year of evaluation, six quadrats were randomly distributed in each transect to measure the variables. The botanical composition of the most representative species in the different seedbeds was analyzed using the following variables: plant density (plants m−2) separated by species, for which the number of plants by species in each quadrat were counted; and DM production per species, for which the entire aerial biomass from a quadrat was cut around 10 cm above ground level and separated by species. To dry out the forage, the samples were placed in a drying oven at 65 C for 72 h (GCA/Precision Scientific Model 28, Thelco, Englewood, CO, USA). The weighing was performed on a digital scale (Viper BC, Mettler-Toledo, Singapore).

For the statistical analysis, independent-samples t-tests were carried out to compare the prepared seedbeds within the same year. In addition, the same seedbed was compared across the years evaluated. The sampling was performed on different and randomly assigned quadrats each year. The analyses were performed in SAS software v. 9.1.3 (SAS 2006). The significance level set for all the tests was α = 0.05. Due to the low establishment of B. gracilis, B. curtipendula, and L. dubia, only E. lehmanniana and E. curvula were considered when carrying out the analysis.

Results and Discussion

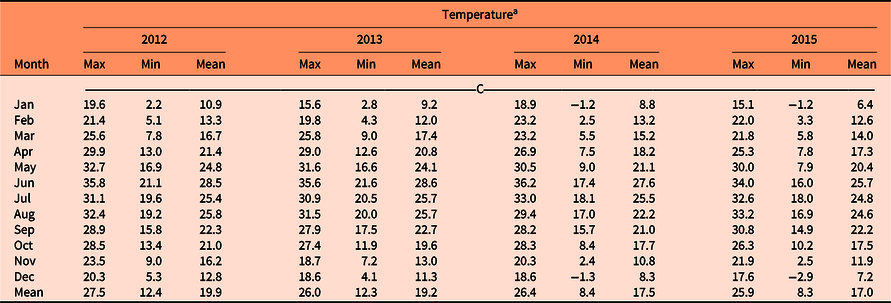

The annual precipitation during the years 2012, 2013, 2014 and 2015 were 349, 544, 390, and 379 mm, respectively. The average annual precipitation estimated for La Campana from 1982 to 2015 was 365 mm (Figure 4). The rainy season generally occurred from July to September. The average annual precipitation for the study period was 416 mm. The year of 2013 was not typical, as precipitation of around 200 mm above the historic mean was registered. Semiarid areas present high variations in seasonal precipitation patterns. This has become increasingly notable due to the effects of climate change (Méndez et al. Reference Méndez, Návar and González2008). Regarding air temperature, 2014 was the hottest year, and June was the month that registered the highest temperatures during the study. For 2012 and 2013, January presented the minimum temperature. Meanwhile, the coldest month for 2014 and 2015 was December (Table 2).

Figure 4. Monthly mean precipitation based on records from La Campana experimental ranch (Chihuahua, Mexico) and the R. Flores Magón weather station (INIFAP). Means were estimated from records of the period 1982–2015.

Table 2. Monthly mean temperatures (C) for La Campana experimental ranch (Chihuahua, Mexico) from 2012 to 2015.

a Max, maximum; Min, minimum.

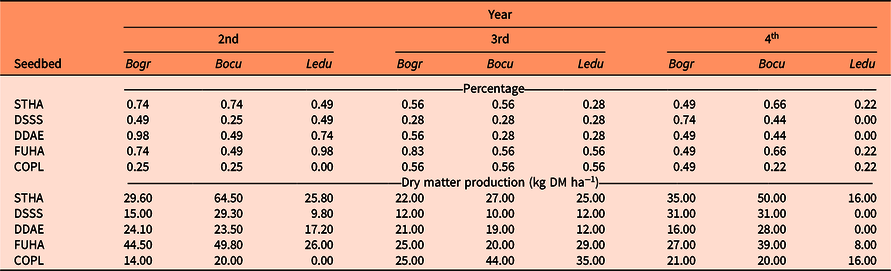

Due to their low establishment, B. gracilis, B. curtipendula, and L. dubia were not included in the statistical analyses. In all seedbeds at the time of the three evaluations, only one to three plants of these species were established, with records in only one or two of the 24 quadrats sampled in each plot. The percentage of established native plants compared with all the individuals in a plot varied from 0.0% to 0.98%. Consequently, DM production of native plants was poor in all treatments and evaluation periods (Table 3). The low plant density and DM production of B. gracilis, B. curtipendula, and L. dubia in the control plot may be due to the absence of seeds in the natural seedbank of the study area (Gutiérrez et al. Reference Gutiérrez, Morales, Villalobos, Ruíz, Ortega and Palacio2019). Although the proportion of seed from native species combined was higher than E. curvula in the seed mixture (55% vs. 40%, respectively), native species were not successful in their establishment. Even though native semiarid grassland species are adapted to soils with low fertility, many of these species show a lower relative growth rate than invasive species; when resources are scarce, invasive species are more competitive (García-Serrano et al. Reference García-Serrano, Escarre, Garnier and Sans2005; Pinedo et al. Reference Pinedo, Hernández, Melgoza, Rentería, Vélez and Morales2013). The slow growth rate, leaf area development, and root development are traits that confer a disadvantage on native versus invasive species (Carrillo et al. Reference Carrillo, Arredondo, Huber-Sannwald and Flores2009; James and Drenovsky Reference James and Drenovsky2007). Esqueda et al. (Reference Esqueda, Melgoza, Sosa, Carrillo and Jiménez2005) reported a lower survival rate of B. grama, B. curtipendula, and L. dubia compared with E. curvula under different types of soil and humidity–drought combinations. They attributed such low survival to rapid germination caused by the first rains and a low root–shoot ratio generated in the seedling stage. Generally, the seedling roots of native species from arid zones of northern Mexico do not grow deep enough to reach the water that could be available at depths of more than 10 cm; E. curvula behaves in the opposite way (Esqueda et al. Reference Esqueda, Melgoza, Sosa, Carrillo and Jiménez2005; Morales et al. Reference Morales, Melgoza and Esqueda1988; Moreno-Gómez et al. Reference Moreno-Gómez, García-Moya, Rascón-Cruz and Aguado-Santacruz2012). Thus, including both native and introduced seed species in the same mixture could represent a disadvantage for native grasses. However, in grassland reseeding programs it is important to include seed of native species developed from local genotypes and adapted to regional conditions; this could increase the establishment success and maintain natural diversity in the ecosystem (Whalley et al. Reference Whalley, Chivers and Waters2013). Given the low establishment of the native species included in the seed mixture, the following analyses focused only on E. lehmanniana and E. curvula.

Table 3. Percentage (%) of established native plants compared with the total per plot and dry matter (DM) production of native grasses evaluated during the second to the fourth year after seeding in different seedbeds. a

a Bogr, Bouteloua gracilis; Bucu, Bouteloua curtipendula; Ledu, Leptochloa dubia; STHA, Striped Harrowing; DSSS, Deep-Stingray Subsoiler; DDAE, Double-Digging Aeration; FUHA, Full Harrowing; COPL, Control plot (without tillage).

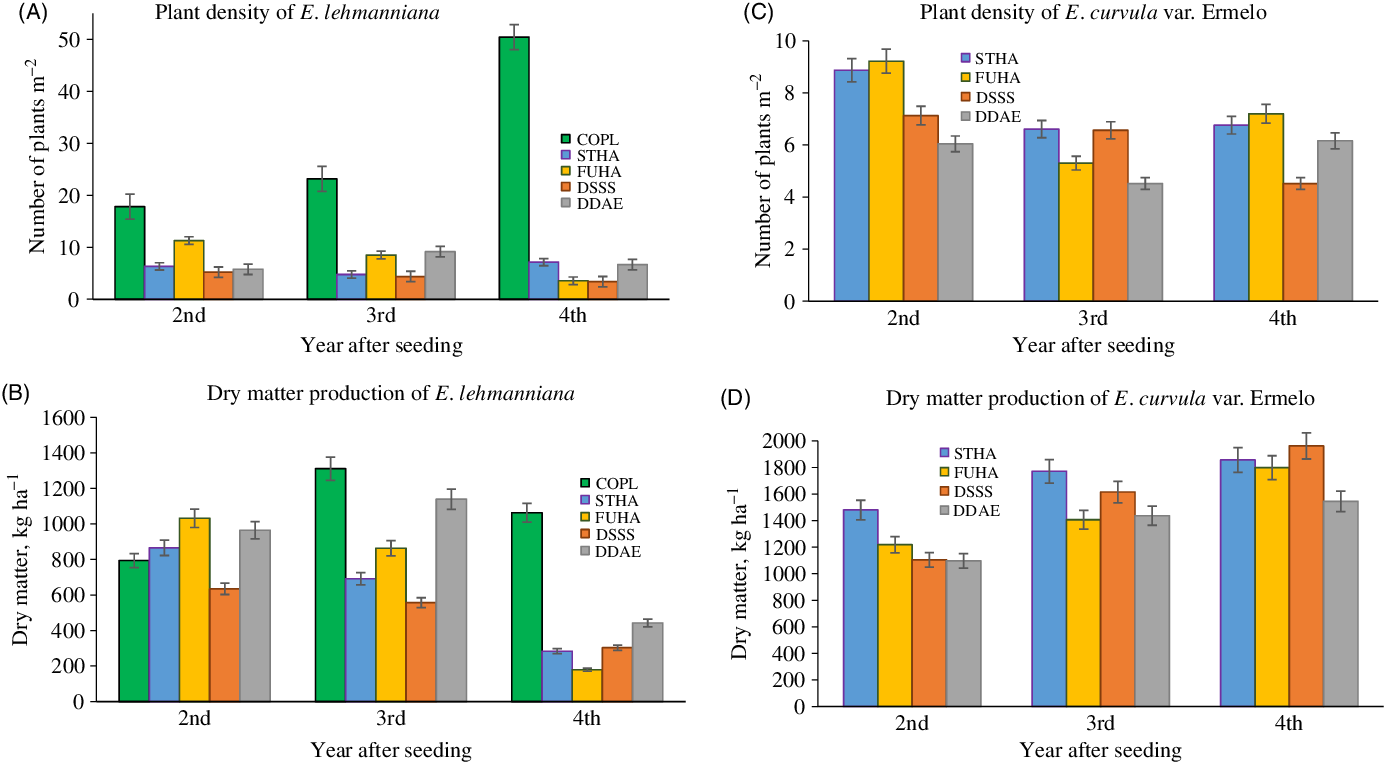

In all the prepared seedbeds, plant density and DM production of E. lehmanniana decreased significantly (P < 0.05) compared with the control plot. When prepared seedbeds within the same year were compared, statistical differences were also found (Table 4). Likewise, for the comparison of the same seedbed between years, statistical differences were found (Table 5). The plant density of E. lehmanniana in the control plot increased every year of the evaluation period. During the final year, its density was around 300% greater than its initial value. In contrast, the plant density of E. lehmanniana gradually decreased in the prepared seedbeds in the years evaluated (Figure 5A).

Table 4. P-values with the t-test in the comparison of means for plant density (plants m−2) and dry matter production (kg ha−1) within every year after seeding, Comparisons were made between different seedbeds. a

a P < 0.05 represents statistical difference. STHA, Striped Harrowing; DSSS, Deep-Stingray Subsoiler; DDAE, Double-Digging Aeration; FUHA, Full Harrowing; COPL, Control plot (without tillage).

Table 5. P-values with the t-test in the comparison of means for plant density (plants m−2) and dry matter production (kg ha−1) from seedbeds prepared with unconventional tillage implements. a

a Comparisons were made for the same seedbed between years after seeding. P < 0.05 represents statistical difference. STHA, Striped Harrowing; DSSS, Deep-Stingray Subsoiler; DDAE, Double-Digging Aeration; FUHA, Full Harrowing; COPL, Control plot (without tillage).

Figure 5. Means ± standard errors of plant density and dry matter production of Eragrostis lehmanniana and Eragrostis curvula in different seedbeds during 4 yr after seeding. STHA, Striped Harrowing; DSSS, Deep-Stingray Subsoiler; DDAE, Double-Digging Aeration; FUHA, Full Harrowing; COPL, Control plot (Without tillage).

The increase in plant density of E. lehmanniana in the control plot was possibly due to the absence of grazing during the study, coupled with the lack of competition from other species. The capacity of this species to produce large amounts of seed also influenced plant density. Carrillo et al. (Reference Carrillo, Arredondo, Huber-Sannwald and Flores2009) reported that 1 g of E. lehmanniana seed in the Chihuahuan Desert grasslands provided approximately 15,000 seeds with 3% germination. Other authors also report that E. lehmanniana is characterized by depositing an abundant seedbank in the soil per season (De los Ángeles et al. Reference De los Ángeles, Vergara and Vargas2002; Guevara et al. Reference Guevara, Estevez and Stasi2007). Given that, if a single plant produced only 1 g of seed, it could generate at least 500 new seedlings. In contrast, the reduction of E. lehmanniana density in the prepared seedbeds is possibly due to the damage caused to the roots of this species by the tillage implements. Eragrostis lehmanniana produces a dense but shallow root system with an average depth of 30 cm (Cox et al. Reference Cox, Giner-Mendoza and Dobrenz1992; Spain et al. Reference Spain, Navas, Lascano, Franco, Hayashi, Tothill and Mott1984; USDA-NRCS 2006). In addition, with a toothed harrow and subsoiler combined with crumbling rollers, the surface soil layer where the weed seedbank is located, is turned and incorporated at a 15-cm depth, greatly inhibiting the emergence of seedlings (Bàrberi Reference Bàrberi2004; Knobloch Reference Knobloch2010; Kukal Reference Kukal and Verheye2010). In the case of the Tandem-type Aerator Roller, the blades pass through the same place twice, which implies that the weed seedbank is driven deeper, limiting seed emergence (Sierra et al. Reference Sierra, Ramírez and Gutiérrez2014). In this case, the seedbank of E. lehmanniana could be buried enough to allow germination of only few seeds that could be exposed or slightly covered after the passage of the tillage implements. In the semiarid grasslands of Chihuahua, an area dominated by E. lehmanniana would see this weed double its plant cover in a couple of years if appropriate management is not applied or if the area is excluded from grazing.

In the control plot, plant density of E. lehmanniana was highest in the fourth year; however, DM production from this year was lower than DM production from the third year. This may be due to the age of the E. lehmanniana, plants, which were young and small. In general, DM production of this species all prepared seedbeds was lower than in the control plot. This was probably due to the reduction of E. lehmanniana population caused by the unconventional implements and the establishment of E. curvula (Figure 5B). Previous studies report that soil preparation contributes to increasing the establishment and productivity of seeded grasses. Tillage implements decompress the soil and increase soil aeration, as well as water retention, which is beneficial for plant development after seeding (Fierro et al. Reference Fierro, Ibarra and Sierra1980; Loredo Reference Loredo2005; Miller Reference Miller2016). In the case of E. lehmanniana, tillage did not increase plant density or DM production; this may be because seed of this species was not included in the seed mixture. Although seed of E. lehmanniana was present in the natural seedbank, the turning of the soil probably buried the seed and prevented its establishment (Bàrberi Reference Bàrberi2004; Knobloch Reference Knobloch2010; Kukal Reference Kukal and Verheye2010; Sierra et al. Reference Sierra, Ramírez and Gutiérrez2014).

Plant density and DM production of E. curvula were only evaluated in the prepared seedbeds, as seed was neither dispersed nor found naturally in the soil in the control plot. Comparisons of seedbeds were made within each year (Table 4). Moreover, comparisons of the same seedbed were made between years (Table 5). Plant density of E. curvula in each prepared seedbed behaved variably; 6 to 9 plants m−2 were registered in the second year from seeding, while 4 to 7 plants m−2 were registered in the fourth year (Figure 5C). Regarding E. lehmanniana, the reduction of its plant density was more noticeable, given that 5 to 11 plants m−2 were present in the second year from seeding, while 3 to 7 plants m−2 were registered in the fourth year. Tillage provides greater soil aeration and greater soil moisture retention during long periods. That favors the development of long-rooted species such as E. curvula, which develops a vigorous root even in acid soils (Abate et al. Reference Abate, Hussein, Laing and Mengistu2013; Colom and Vazzana Reference Colom and Vazzana2002; Royo et al. Reference Royo, Sierra, Morales-Nieto and Jurado2010). The physiological development of E. curvula in the prepared seedbeds may have contributed to control the proliferation of the E. lehmanniana. The establishment capacity of E. curvula shown in this study agrees with results reported by Martínez et al. (Reference Martínez, Ruiz M de los and Babinec2003), who found greater establishment of this species than Klein grass (Panicum coloratum L.) and Robies cocksfoot grass (Tetrachne dregei Nees) at different seeding depths. Another reason for the reduction in E. lehmanniana population may be a decrease in its photosynthesis rate due to shading by E. curvula, as tall plants with high leaf densities are genetic attributes of the species (USDA-NRCS 2006). These characteristics give E. curvula an advantage in gaining access to sunlight, water, and soil nutrients, which may have also limited the establishment and development of the native species included in the seed mixture. Interspecific competition allows dominant species to limit or exclude the presence of others within a habitat, a phenomenon known as competitive exclusion (Osorno Reference Osorno2014).

Eragrostis lehmanniana plant density was clearly reduced by the establishment of E. curvula in the prepared seedbeds. Plant density of E. lehmanniana in the prepared seedbeds decreased more than 50% from the second to the third year after seeding. At the end of experiment, the E. lehmanniana population was around 10 times greater in the control plot than in the prepared seedbeds. In contrast, DM production of E. curvula in the prepared seedbeds increased during the study (Figure 5D). The behavior of E. lehmanniana was the opposite. The Rangeland Harrow and Rangeland Rehabilitator implements contributed to higher DM production of E. curvula than did the Tandem-type Aerator Roller. Precipitation and seedbed preparation did not show a relationship with DM production of E. curvula and E. lehmanniana. Precipitation of almost 200 mm above the historical mean was registered during the second year after seeding. However, E. curvula had the lowest DM production during this period, increasing in the subsequent years. In contrast, E. lehmanniana presented higher yields during the wettest year and decreased production in the following years in the prepared seedbeds.

The Rangeland Harrow and Rangeland Rehabilitator could have generated seedbeds with greater infiltration than the seedbed prepared with the Tandem-type Aerator Roller. This in turn favored DM production of E. curvula. The preparation of the seedbeds, especially those that left areas for runoff, together with the inclusion of E. curvula var. Ermelo, served as a mechanical and biological control, respectively, to reduce the invasion of E. lehmanniana and increase DM production in semiarid grasslands in Chihuahua. In the first year of sampling, the control plot showed a DM production of 793 kg ha−1. During the last year, the seedbeds of Double-Digging Aeration, Full Harrowing, Striped Harrowing, and Deep-Stingray Subsoiler registered DM production of 1,545, 1,800, 1,850, and 1,960 kg ha−1, respectively. This represents DM production nearly double that seen using the Tandem-type Aerator Roller and more than double that seen using deep-tillage implements. Guevara et al. (Reference Guevara, Estevez, Stasi and Le Houérou2005) recommended E. curvula to rehabilitate degraded arid grasslands in Argentina, as this grass provides an economic and ecological alternative. Furthermore, Bravo et al. (Reference Bravo, Sáenz, Barrera, Medina, Mendoza, Prat and García2011) recommended E. curvula var. Ermelo for arid and semiarid zones of Mexico due to its palatability for livestock and its good establishment capacity in poor soils. However, E. curvula should be grazed for optimal use once it is established. Bernau et al. (Reference Bernau, Sprinkle, Tanner, Kava, Thiel, Prileson and Tolleson2014) stated that directed grazing schemes allow E. curvula to be managed to avoid its dispersal and to give native vegetation greater competitive opportunities. Royo et al. (Reference Royo, Sierra, Morales-Nieto and Jurado2010) emphasized the importance of soil preparation for grassland reseeding, because this technique breaks the hard layer of the soil, aids water infiltration, and favors plant emergence and the establishment and production of forage. Rangeland restoration practices with tillage implements have contributed to the recovery of degraded and invaded areas with undesirable species (Sierra et al. Reference Sierra, Fierro, Echavarría, Gómez, González, Martín and Ibarra1981; Yurkonis Reference Yurkonis2013). Despite the high plant density that E. lehmanniana can generate on semiarid grasslands in natural conditions, it contributes low productivity. In the semiarid grasslands of Chihuahua State, it has been reported from 5.3% to 6.2% of crude protein in the growth stage for this species (González-García et al. Reference González-García, Sánchez-Maldonado, Sánchez-Muñoz, Orozco-Erives, Castillo-Castillo, Martínez-De la Rosa and González-Morita2017). This represents a low forage value and may be one of the reasons why E. lehmanniana is of low appeal to livestock and wildlife.

Reseeding with E. curvula var. Ermelo at the time of seedbed preparation with the unconventional tillage implements used in this study reduced the original population of E. lehmanniana more than half. Eragrostis curvula produced the highest forage production during the 4 yr of the experiment and doubled its DM production in areas invaded with E. lehmanniana. The preparation of seedbeds with the unconventional Rangeland Harrow, Rangeland Rehabilitator, and Tandem-type Aerator Roller tillage implements, together with seeding E. curvula var. Ermelo, represents an alternative to reduce populations of E. lehmanniana in the semiarid grasslands of Chihuahua. It is recommended that rangeland managers include native species when seeding, using seed of high quality, preferably produced locally and adapted to the region.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank INIFAP, CONAZA, and government of Chihuahua State for their contribution to the present study.