Management Implications

Rhamnus cathartica (common buckthorn) is an aggressive invasive shrub that shades out native plants, negatively impacts the surrounding plant community, and is detrimental to agricultural crops. Our findings of relatively low levels of genetic variation in both introduced populations in North America and native populations in Europe with no genetic differentiation between the two ranges, indicate that invasive spread is likely due to its horticultural history and various traits and life-history strategies of the species.

Rhamnus cathartica may be particularly challenging to manage due to allelopathy that enables it to outcompete surrounding plants. Effective management strategies for R. cathartica have included controlled fires and use of herbicides. Although repeated fire or herbicide application may be required for effective control, newly burned areas need to be carefully monitored, as increased light could lead to further infestation. In these cases, hand pulling may be a better method of control, although it is less efficient and more labor-intensive for large infestations. Removing plants before their fruits mature may be crucial to prevent seed dispersal by birds.

Our study also demonstrates that R. cathartica is genetically and taxonomically distinct from Frangula alnus (glossy buckthorn, previously Rhamnus frangula), another widespread invasive shrub often misidentified as R. cathartica in the field. Thus, landscape managers should remove buckthorn species when encountered, regardless of their taxonomy. Future investigation is still needed to determine whether currently available F. alnus cultivars like ‘Fine Line’ and ‘Asplenifolia’ are sterile or may be contributing to the formation of invasive buckthorn populations.

Introduction

Although many plant species now recognized as invasive in North America were introduced accidentally, many others were intentionally brought to the continent for use in horticulture, agriculture, medicine, soil stabilization, or other reasons (Kurylo and Endress Reference Kurylo and Endress2012; Reichard and White Reference Reichard and White2001). Intentional introductions are especially common in woody invasive plant species, of which 82% were used for landscaping at some point in North America (Reichard Reference Reichard1994). The impact of these intentional introductions on the introduced gene pool remains understudied in woody species relative to herbaceous species, particularly grasses (e.g., Brodersen et al. Reference Brodersen, Lavergne and Molofsky2008; Lavergne and Molofsky Reference Lavergne and Molofsky2007; Meyerson et al. Reference Meyerson, Viola and Brown2010; Quinn et al. Reference Quinn, Culley and Stewart2012; Saltonstall et al. Reference Saltonstall, Castillo and Blossey2014). One possible impact involves the repeated and widespread introduction of a few cultivated varieties of a given species, which could lead to a genetic bottleneck and genetic drift relative to populations in the native range. Low levels of genetic variation in these introduced populations were once thought to constrain local adaptation to new environments (Sakai et al. Reference Sakai, Allendorf, Holt, Lodge, Molofsky, Kimberly, With, Baughman, Cabin, Cohen, Ellstrand, McCauley, O’Neil, Parker, Thompson and Weller2001), but that view has now shifted to consider the nature of genetic variation itself rather than only its overall quantity (Dlugosch et al. Reference Dlugosch, Anderson, Braasche, Cang and Gillette2015). For example, horticultural cultivation of a species may lead to admixture of individual genotypes to form unique, aggressive combinations. Alternatively, cultivation may create broadly adapted genotypes that may spread quickly across the landscape, assisted by commercial distribution pathways. The successful invasion of giant reed (Arundo donax L.) has been traced back to the introduction of a single nonnative genotype that outcompeted native genotypes (Ahmad et al. Reference Ahmad, Liow, Spencer and Jasieniuk2008); in this case, overall genetic variation is low, but invasion has still been quite successful. Within the field of invasion biology, the role of horticulture in impacting the spread of introduced species across their range remains relatively understudied.

Common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica L.; sometimes referred to as European buckthorn) is a dioecious shrub or small tree whose native range extends throughout Europe and western Asia (Klionsky et al. Reference Klionsky, Amatangelo and Waller2011). In North America, it is considered an invasive species that occurs at many different light levels, moisture gradients, and habitats (Knight et al. Reference Knight, Kurylo, Endress, Stewart and Reich2007), forming dense thickets in forests, wetland edges, and open areas (Kurylo and Endress Reference Kurylo and Endress2012). Following pollination of the scented flowers by insects, so successfully that the process has been described as “aggressive” (Archibold et al. Reference Archibold, Brooks and Delanoy1997), female plants produce many fruits, which are primarily dispersed by birds; the fruits have a laxative effect, thus ensuring their release near the source (Knight et al. Reference Knight, Kurylo, Endress, Stewart and Reich2007; Seltzner and Eddy Reference Seltzner and Eddy2003). Seeds can germinate readily, with an average rate of 85% in North American populations (Archibold et al. Reference Archibold, Brooks and Delanoy1997) and up to 99% in Europe (Godwin Reference Godwin1936). The age of reproduction of individuals varies, but once plants begin to reproduce, they do so consistently most years (Godwin Reference Godwin1943). Generally, R. cathartica has a high affinity for disturbed areas (Knight et al. Reference Knight, Kurylo, Endress, Stewart and Reich2007), efficiently establishing dominance in previously uninvaded areas and retaining strong regeneration in areas already invaded (Klionsky et al. Reference Klionsky, Amatangelo and Waller2011).

Rhamnus cathartica was introduced to North America possibly as early as the mid-16th century because of its medicinal use as a powerful cathartic (Kurylo and Endress Reference Kurylo and Endress2012). During the 20th century, R. cathartica began to be promoted as an ornamental plant, primarily as a hedge for lawn decoration. Commercialization favored R. cathartica shrubs with greater shade tolerance and rapid growth (Knight et al. Reference Knight, Kurylo, Endress, Stewart and Reich2007). During the 20th century, a morphologically similar related species, glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus Mill.; syn. Rhamnus frangula L.; also called alder buckthorn) also increased in popularity as an ornamental after being introduced in the late 18th century or early 19th century (De Kort et al. Reference De Kort, Mergeay, Jacquemyn and Honnay2016). To the best of our knowledge, R. cathartica and F. alnus have not been widely distributed through the ornamental pathway in their native European range. Although R. cathartica has declined in availability in commercial nurseries in North America, F. alnus continues to be sold today (Dirr Reference Dirr1998) as the cultivars ‘Asplenifolia’, ‘Columnaris’, and ‘Fine Line’ (a hybrid of Asplenifolia and Columnaris, also sold under the cultivar name ‘Ron Williams’).

Many traits of R. cathartica aid its successful invasive behavior, including tolerance of a wide range of moisture and drought, rapid growth, high photosynthetic rate, and high fecundity (see Knight et al. Reference Knight, Kurylo, Endress, Stewart and Reich2007), along with an ability to rapidly and effectively distribute its seeds (Heidorn Reference Heidorn1990). Rhamnus cathartica also impacts the soil by altering the leaf litter layer and soil nitrogen (Seltzner and Eddy Reference Seltzner and Eddy2003); such changes in nutrient cycling can adversely affect ecosystems (Roth et al. Reference Roth, Whitfeld, Lodge, Eisenhauer, Frelich and Reich2014). In addition, the species negatively impacts native plants through competition and possible allelopathy (Gale Reference Gale2000; Seltzner and Eddy Reference Seltzner and Eddy2003; Warren et al. Reference Warren, Labatore and Candeias2017) and it also reduces native species richness (Heimpel et al. Reference Heimpel, Frelich, Landis, Hopper, Hoelmer, Sezen, Asplen and Wu2010; Roth et al. Reference Roth, Whitfeld, Lodge, Eisenhauer, Frelich and Reich2014); both factors impact native animal populations by altering their habitats (Knight et al. Reference Knight, Kurylo, Endress, Stewart and Reich2007). Furthermore, R. cathartica may contribute to invasional meltdown involving other invasive species, such as the soybean aphid (Aphis glycines Matsumura) and the plant pathogen oat crown rust (Puccinia coronata Corda) (Roth et al. Reference Roth, Whitfeld, Lodge, Eisenhauer, Frelich and Reich2014), but it does not facilitate invasive European earthworms (Lumbricus terrestris L.) (Wyckoff et al. Reference Wyckoff, Shaffer, Hucka, Bombyk and Wipd2014; Ziter and Turner Reference Ziter and Turner2019; but see Heimpel et al. Reference Heimpel, Frelich, Landis, Hopper, Hoelmer, Sezen, Asplen and Wu2010).

The purpose of this study was to investigate genetic variation and structure of R. cathartica in North America, compared with its native Eurasian range, to better understand patterns of spread. Specifically, we were interested in whether the historical use and later widespread commercialization of R. cathartica in North America may have introduced a limited number of genotypes, which created a genetic bottleneck in the introduced range, consistent with lower genetic diversity. Alternatively, the remarkable ability of this invasive shrub to spread so vigorously and displace other plant species throughout its wide introduced range may indicate a single broadly adapted genotype, hybrid vigor, or a high reservoir of genetic variation.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection

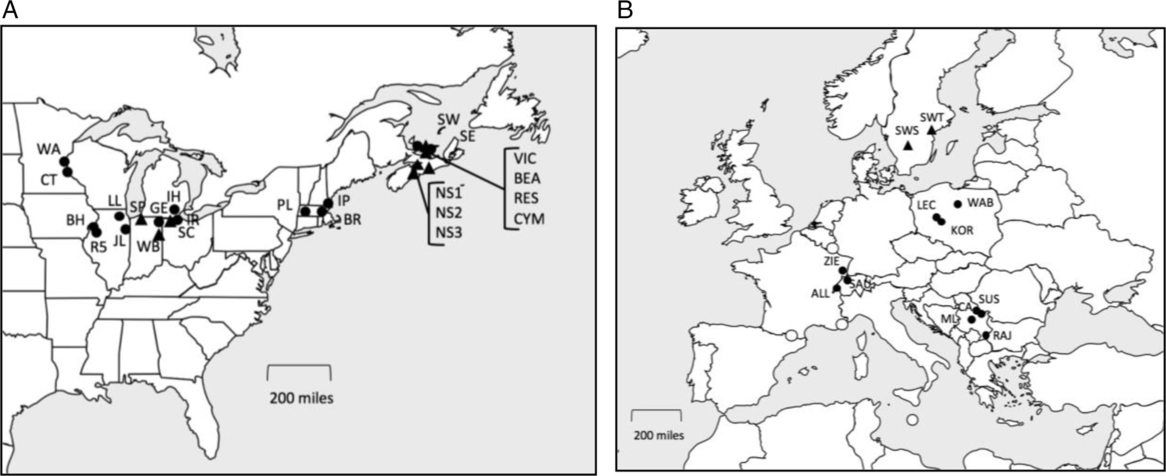

For this study, samples of R. cathartica were collected by JRS and our collaborators from the introduced range in North America and from the native range in Europe during spring and early summer in 2007. In North America, 24 wild populations were sampled from Illinois, Indiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nova Scotia, Ohio, and Prince Edward Island, while 12 European populations were sampled in Germany, Poland, Serbia, Sweden, and Switzerland (Table 1; Figure 1). Within each population, two to three leaves each were taken from 10 to 12 R. cathartica individuals that were randomly distributed across the site and at least 2 m apart. Leaf tissue was then stored with silica gel until DNA could be extracted. Upon closer morphological inspection of the sampled leaves after DNA analysis (see following section), it was discovered that some samples collected by collaborators had been misidentified in the field and were F. alnus. Frangula alnus is similar in appearance to R. cathartica (Culley and Stewart Reference Culley and Stewart2010) and can be distinguished by a difference in the pairs of veins located on the leaves and tooth patterns along the edge of the leaves (Figure 2).

Table 1. Descriptions of populations of Rhamnus cathartica and Frangula alnus sampled in this current study.

Figure 1. Distribution of sampled populations in (A) the introduced range in North America and (B) the native range in Europe. Shown are populations later verified as Rhamnus cathartica (circles) or identified as Frangula alnus (triangles). See Table 1 for definitions of location codes.

Figure 2. Rhamnus cathartica (left) and Frangula alnus (right). Although F. alnus is often misidentified as R. cathartica, it is taxonomically and genetically distinct. Photo of R. cathartica courtesy of Paul Wray under a CC BY-NC license, and photo of F. alnus courtesy of Leslie Merhrhoff under a CC BY license.

DNA Extraction and Genetic Analysis

DNA from one leaf of each field sample was extracted using the modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide method of Doyle and Doyle (Reference Doyle and Doyle1987). Thirteen microsatellite markers previously developed for R. cathartica were originally screened and initially analyzed, but only eight markers that amplified consistently across all populations (RhamA7a, RhamH7, RhamE11, RhamB9a, RhamB9b, RhamH11, RhamD8, and RhamE8; Culley and Stewart Reference Culley and Stewart2010) were finally used to quantify genetic variation and structure. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in multiplexed reactions with two primer groups that incorporated fluorescently labeled forward primer during the PCR reaction (Culley et al. Reference Culley, Stamper, Stokes, Brzyski, Hardiman, Klooster and Merritt2013). Using the Qiagen Multiplex kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), PCR was carried out in 10 μl reaction volumes as follows: 5 μl Multiplex PCR Master Mix, 1 μl 10× primer mix (each primer at 2 μmol L−1), 0.2 μl DNA (approximately 20 ng μl−1), and 3.8 μl dH2O. Multiplex PCR consisted of 95 C for 15 min; followed by 30 cycles each of 94 C for 30 s, 57 C for 45 s, 72 C for 45 s; and then eight cycles each of 94 C for 30 s, 53 C for 45 s, and 72 C for 45 s. A final extension consisted of 72 C for 10 min. PCR products were then run on a 3730xl sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Fortune City, CA, USA) at the Cornell University BioResource Center with the LIZ 500 internal size standard. Fragment analysis was conducted in GeneMarker v. 1.85 (SoftGenetics, State College, PA, USA). For all loci tested, the presence of three strong peaks was very rare, but did occur in RhamE11 (12 individuals of F. alnus) and in RhamD8 (two individuals of F. alnus, 15 of R. cathartica). To use standard statistical approaches that assume diploidy, the allele with the lowest amplification was eliminated in these samples.

Genetic variation was estimated for North American and European populations of taxonomically confirmed R. cathartica using GenAlEx v. 6.502 (Peakall and Smouse Reference Peakall and Smouse2006, Reference Peakall and Smouse2012) as the following: average sampling size (N), number of alleles per locus (A), percentage of polymorphic loci (P), observed heterozygosity (H o), expected heterozygosity (H e), and Wright’s fixation index (F). Differences in these variables between the introduced and native ranges of R. cathartica were tested using a Student’s t-test with unequal variances in R v. 3.6.0 (R Core Team 2019). Genetic structure in R. cathartica based on the microsatellite data was examined with a principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA), and F-statistics.

Results and Discussion

This study indicates that Rhamnus cathartica may be an example of the “invasion paradox” (Allendorf and Lundquist Reference Allendorf and Lundquist2003; Dlugosch et al. Reference Dlugosch, Anderson, Braasche, Cang and Gillette2015; Estoup et al. Reference Estoup, Ravigné, Hufauer, Vitalis, Gautier and Facon2016), but further investigation is still needed. In this situation, an introduced species thrives in a new environment despite reduced genetic diversity following a bottleneck during its founding. In R. cathartica, low levels of genetic variation were found in North American populations, although this was also detected in the native European range (Table 2). Both introduced and native populations exhibited the same average number of alleles per locus (A = 2.32) despite having a moderate proportion of polymorphic loci (P intro = 69.2, P native=70.0; t = 0.149, df = 21, P = 0.441). A slight bottleneck was evident in the level of observed heterozygosity, which was significantly lower in introduced populations (H O = 0.32) than in native populations (H O = 0.40; t = 2.15, df = 18, P = 0.022). However, the level of expected heterozygosity did not significantly differ among populations in the two ranges (H E(intro) = 0.29; H E(native) = 0.32; t = 1.200, df = 23, P = 0.121) and was overall lower than expected, as indicated by the fixation index F, which was usually negative (Table 2). These measures of heterozygosity are approximately half of those found in other widespread species (H O = 0.57, H E = 0.62), long-lived perennials (H O = 0.63, H E = 0.68), and outcrossing species (H O = 0.63, H E = 0.65; Nybom Reference Nybom2004).

Table 2. Genetic variation in populations of Rhamnus cathartica in the introduced range in North America and in the native range in Europe, with the sample size averaged across loci (N), number of alleles (A), percentage of polymorphic loci (P), levels of observed heterozygosity (H o) and of expected heterozygosity (H e), and fixation index (F) for the 15 introduced and the 10 native populations listed. Significant differences (based on a t-test) between the introduced and native ranges are indicated with different letters. This table excludes Frangula alnus, for which only a single microsatellite locus (RhamE11) amplified.

It is possible that these genetic levels are low due to the fact that only eight loci were used and a small proportion of each population was sampled (10 to 12 individuals). Although more loci would certainly be of value in future studies, an analysis using a genotype accumulation curve in poppr in R indicated that the eight loci resulted in nearly 100% detection of all 206 multilocus genotypes. The low number of samples per site may have led to the unintentional sampling of subpopulations (i.e., the Wahlund effect), as indicated by the negative fixation indices in some populations. Additional samples within populations may identify more rare alleles, leading to increases in A and refinement of the number of private alleles within populations and regions. Furthermore, more intensive sampling of additional populations in the native range with more loci is required to more fully characterize the genetic composition there (see Hale et al. Reference Hale, Burg and Steeves2012) and to accurately identify the number of introduction events and where the founders originated (Estoup et al. Reference Estoup, Ravigné, Hufauer, Vitalis, Gautier and Facon2016). In the current study, 82% of the 60 alleles detected in North America were also detected in European populations, indicating one or more introduction events. Future investigations could further refine the number of introduction events and help clarify whether the low levels of variation detected here are naturally present or due to limited sampling or amplified loci.

Despite the relatively low levels of genetic variation present in the species, populations of R. cathartica were still strongly differentiated from one another within the introduced North American range (F st = 0.490) and also within the native European range (F st = 0.523). Within each group, certain loci were fixed in a few populations, as opposed to all loci varying across all populations. Despite strong variation within each region, R. cathartica populations in North America were not substantially differentiated from those in Europe (F st = 0.017) when all samples were analyzed together. Sixty-four percent of all 76 alleles were common to both ranges; the only exceptions were 12 rare alleles (with frequencies of 1% to 3%, although most were <1%) detected only in the introduced range and 16 rare alleles (5% or lower) restricted to the native range. Although more extensive sampling within populations is still needed to determine whether these alleles are indeed rare, it is feasible that at least some genetic mutations have occurred within North American populations of R. cathartica. An overall lack of differentiation between the introduced and native ranges was also reinforced by the PCoA generated from the microsatellite data (Figure 3). Based on this analysis, there was no substantial genetic differentiation between native and introduced regions, with 55.43% of variation in the data explained by the two axes. Furthermore, the AMOVA based on microsatellite data indicated that no substantial molecular variance was evident between the North American and European regions (Table 3), even though patterns of genetic structure within each region were similar among populations and generally consistent with F st values (variation among populations: North American = 35%, Europe = 40%).

Figure 3. Principal coordinates analysis indicates a large overlap in the genetic distribution of sampled plants, with no substantial genetic structure between Rhamnus cathartica in the introduced range in North America (orange diamonds) and the native range in Europe (blue circles). This analysis excludes samples later determined to be Frangula alnus.

Table 3. Results of the analysis of molecular variance based on eight microsatellite loci in populations of Rhamnus cathartica in North America (introduced region) and Europe (native region).

Other genetic studies of populations of invasive species in their introduced and native regions have detected similar or lower amounts of genetic variation in introduced populations (Durka et al. Reference Durka, Bossdorf, Prati and Auge2005; Quinn et al. Reference Quinn, Culley and Stewart2012), consistent with a bottleneck effect. Such a phenomenon has been seen in the invasive grass Chinese silvergrass (Miscanthus sinensis Andersson) (Quinn et al. Reference Quinn, Culley and Stewart2012) and the herb garlic mustard [Alliaria petiolata (M. Bieb.) Cavara & Grande] (Durka et al. Reference Durka, Bossdorf, Prati and Auge2005), in which the number of alleles were significantly lower in U.S. populations compared with the native Asian range, although levels of heterozygosity were similar between the two ranges for both species. This is the typical pattern seen in recently bottlenecked populations, in which the loss of rare alleles will reduce allelic diversity well before a decline in heterozygosity can be detected (Cornuet and Luikart Reference Cornuet and Luikart1997; Dlugosch et al. Reference Dlugosch, Anderson, Braasche, Cang and Gillette2015). In R. cathartica, the opposite pattern was generally observed: the number of alleles was similar, but levels of heterozygosity were lower in the native range, although only significantly so in H o (t = −2.28, df = 20.83, P = 0.033). This may indicate that one or more bottlenecks have occurred in the more distant past in R. cathartica and may be associated with its horticultural history (see below) amid already low levels of allelic diversity. In all three species, populations were differentiated from one another in both the introduced and native ranges, although F st (or its analog θ) was much lower in M. sinensis (United States: 0.08; Asia: 0.10) than in R. cathartica (United States: 0.49; Europe: 0.52), and A. petiolata (United States: 0.82; Europe: 0.74).

The success of R. cathartica in invading natural areas in North America despite its relatively low level of standing genetic variation is consistent with our most recent understanding of the genetics underlying species invasions (Dlugosch et al. Reference Dlugosch, Anderson, Braasche, Cang and Gillette2015; Estoup et al. Reference Estoup, Ravigné, Hufauer, Vitalis, Gautier and Facon2016). Low levels of genetic variation were once thought to constrain the ability of populations to adapt to new environments (Sakai et al. Reference Sakai, Allendorf, Holt, Lodge, Molofsky, Kimberly, With, Baughman, Cabin, Cohen, Ellstrand, McCauley, O’Neil, Parker, Thompson and Weller2001), but today we recognize that the nature of the remaining genetic variation is more important than its overall amount (Dlugosch et al. Reference Dlugosch, Anderson, Braasche, Cang and Gillette2015). In R. cathartica, the existing minimal genetic variation may reflect the impact of its past horticultural history within its introduced range. Specifically, the historical distribution of groups of vegetatively propagated clones of selected genotypes (i.e., cultivars) in the early 19th century likely led to the creation of large collections of individual genotypes that would normally never encounter each other in the native range. Today, the wild populations in North America consist of many unique multilocus genotypes, indicating that genetic admixture and some mutation has occurred in the past, even though levels of genetic variation remain low.

As far as we know, any reduction in diversity at neutral microsatellite loci has not been reflected in loss of any adaptive traits in R. cathartica—another indication that a genetic invasive paradox may exist (Estoup et al. Reference Estoup, Ravigné, Hufauer, Vitalis, Gautier and Facon2016). For example, the germination mechanism and early bud break of invasive populations of R. cathartica (Stewart et al. Reference Stewart, Graves and Landes2006) allow the shrub to outcompete neighboring taxa, as does its leaf development, which shades out native species (Seltzner and Eddy Reference Seltzner and Eddy2003). In addition, the invasive success of this species has been attributed to allelochemicals in its drupes and decomposing leaf litter (Archibold et al. Reference Archibold, Brooks and Delanoy1997; Klionsky et al. Reference Klionsky, Amatangelo and Waller2011; Seltzner and Eddy Reference Seltzner and Eddy2003). Fruits of R. cathartica also contain anthraquinone, a chemical that acts as a laxative when ingested by birds (Seltzner and Eddy Reference Seltzner and Eddy2003), resulting in effective local dispersal due to its relatively rapid cathartic effect. It now remains to be seen whether these same traits also exist to the same degree in the native range as they do in the introduced range.

This study also underscores the difficulty in accurately identifying R. cathartica in the wild, given its close morphological resemblance to F. alnus (Figure 2; Anonymous 2019). Identification is also complicated by the continued use academically and commercially of the taxonomic synonyms of glossy buckthorn, F. alnus and R. frangula. This became evident in the current study: during initial fragment analysis in which all samples were initially assumed to be R. cathartica, only one of eight loci (RhamE11) consistently amplified within a subset of 82 samples (25% of 328 total samples); this locus was fixed for a single private allele (184). Closer examination of the leaf tissue of these samples confirmed that they were F. alnus, despite being identified as R. cathartica in the field. This observation was also confirmed with a separate analysis of F. alnus cultivars, Asplenifolia and Fine Line, which also only amplified for the same single locus.

Much of the ecological research on the impacts of invasive buckthorn thus far has focused on R. cathartica, assuming accurate identification in the field. Future investigators should also examine the ecological impacts of F. alnus, including potential allelopathy, reproductive output, and the role of intraspecific hybridization through cultivars. Due to the extremely low levels of genetic variation detected with the current set of microsatellite markers in F. alnus, investigators will need to employ more variable markers such as sequence-related amplified polymorphism (Robarts and Wolfe Reference Robarts and Wolfe2014). This is especially important given the continued commercialization of F. alnus, including the introduction of the popular Fine Line cultivar, which is advertised as “produces very few fruit, none of which have been shown to be viable” and “a responsible and environmentally friendly replacement for weedy, older varieties” (Proven Winners 2019). Researchers now need to verify this putative sterility, especially in terms of its potential to cross with wild R. cathartica or F. alnus.

In summary, the invasive spread of R. cathartica in its introduced range in North America is likely attributable to a combination of it past horticultural history influencing its genetic composition and its inherent morphological and physiological traits (e.g., bird dispersal of fruits, strong competitive ability). Past and ongoing commercialization of buckthorn will likely continue to facilitate invasive spread following escape from cultivation. Although R. cathartica is now rarely available in traditional plant nurseries, F. alnus continues to be popular, sold as the Fine Line cultivar. Given that R. cathartica exhibits cold hardiness to −24 C, the northern and northwestern range of existing wild populations are projected to expand with warming (Dukes et al. Reference Dukes, Pntius, Orwig, Garnas, Rodgers, Brazee, Cooke, Theoharides, Stange, Harrington, Ehrenfeld, Gurevitch, Lerdau, Stinson, Wick and Ayres2009), as has already been noted for other plant taxa (King et al. Reference King, Altdorff, Li, Galagedara, Holden and Unc2018). Combined with shifts in flowering phenology now being observed for many plant species (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Yi, Xing, Tang, Wang, Ye, Ng, Chan, Chen and Liu2018), R. cathartica has the potential to continue to spread within its introduced range in North America.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following individuals for collecting the samples used in this study: Kjell Bolmgren (Sweden), David Carmichael (Canada), Andrew Gassmann (Switzerland), Carol Goodwin (Nova Scotia, Canada), Andrzuj Jagodziňski (Poland), Connie Parks (MA, USA), Laura Phillips (MN, USA), and Ivo Tosevski (Serbia). The authors thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Funding was obtained in part from the University of Cincinnati Arts & Sciences STEM Scholarship to AW. No conflicts of interest have been declared.