Management Implications

In 2016, the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry and the Nature Conservancy of Canada applied a custom glyphosate-based herbicide (Roundup® Custom for Aquatic & Terrestrial Use Liquid Herbicide) with a water-safe surfactant (Aquasurf®, registration no. 32152) via helicopter to control 435 ha of invasive Phragmites australis (European common reed) in two freshwater wetland complexes. To assess the efficacy of this control program, we monitored (1) the degree of suppression of P. australis and (2) native vegetation recovery. Standing water depth had no influence on how effectively herbicide reduced P. australis live stem density, and regrowth of P. australis was minimal but did occur. Despite P. australis suppression, herbicide-treated sites did not resemble reference vegetation communities. Instead, many had abundant Hydrocharis morsus-ranae (European frog-bit), a small, free-floating nonnative species. Hydrocharis morsus-ranae co-occurred with P. australis before treatment, and high lake-water levels and the removal of P. australis likely provided an opportunity for it to flourish. Our results suggest that active revegetation (e.g., seeding native plants) may be a necessary step to encourage native plant recovery. Invasive P. australis management must incorporate follow-up treatment as part of routine maintenance to keep P. australis from rebounding. Because repeated glyphosate application may lead to the accumulation of residues (Myers et al. Reference Myers, Antoniou, Blumberg, Carrol, Colborn, Everett, Hansen, Landrigan, Lanphear, Mesnage, Vandenberg, vom Saal, Welshons and Benbrook2016; Sesin et al. Reference Sesin, Davy, Dorken, Gilbert and Freeland2020) or present a risk to wetland food webs (e.g., Beecraft and Rooney Reference Beecraft and Rooney2020), we do not conclude that herbicide application should be the default long-term treatment approach. The risks of herbicide use should be carefully considered when selecting P. australis control techniques, and herbicide-control programs should monitor herbicide concentrations in the treated ecosystem as well as P. australis reinvasion to minimize the disturbance and ecological risk presented by P. australis management.

Introduction

Globally, invasive species alter ecosystems in direct and indirect ways (Pyšek et al. Reference Pyšek, Hulme, Simberloff, Bacher, Blackburn, Carlton, Dawson, Essl, Foxcraft, Genocesi, Jeschke, Kühn, Liebhold, Mandrak and Meyerson2020). The addition of one species can modify community structure and ecosystem functions (Simberloff et al. Reference Simberloff, Martin, Genovesi, Maris, Wardle, Aronson, Courchamp, Galil, Garcia-Berthou, Pascal, Pyšek, Sousa, Tabacchi and Montserrat2013), and the majority of studied invasive plants negatively impact other plants at the species and community levels (Pyšek et al. Reference Pyšek, Jarošík, Hulme, Pergl, Hejda, Schaffner and Montserrat2012). Theoretically, the removal of an invasive plant should catalyze the recovery of native species and ecosystem processes. Yet well-established invasive species can become entrenched in the ecosystem, altering their environment (D’Antonio and Meyerson Reference D’Antonio and Meyerson2002), such that their removal can result in unanticipated ecological changes.

In practice, although management often succeeds in suppressing the targeted invasive plant, secondary invaders are commonly the principal beneficiaries, and native species recovery is limited (Pearson et al. Reference Pearson, Ortega, Runyon and Butler2016). The removal of invasive plants can thus trigger undesirable outcomes that are difficult to anticipate (e.g., González et al. Reference González, Sher, Anderson, Bay, Bean, Bissonnete, Cooper, Dohrenwend, Eichhorst, El Waer, Kennard, Harms-Weissinger, Henry, Makarick and Ostoja2017). Unfortunately, as many have already noted (e.g., Blossey Reference Blossey1999; Hazelton et al. Reference Hazelton, Mozdzer, Burdick, Kettenring and Whigham2014; Kettenring and Adams Reference Kettenring and Adams2011; Zimmerman et al. Reference Zimmerman, Shirer and Corbin2018), invasive species treatment actions are rarely followed by adequate monitoring to provide accountability regarding invasive species management and native vegetation restoration outcomes. For these practices to be considered successful, they should achieve the recovery goals of land managers regarding native vegetation and not only the suppression of the invasive species that prompted the management action.

European common reed [Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. ssp. australis], a perennial grass introduced from Europe, is an aggressive invader of North American wetlands (Catling and Mitrow Reference Catling and Mitrow2011; Saltonstall Reference Saltonstall2002). Once established, invasive P. australis changes its environment. It produces extensive below- and aboveground biomass (e.g., Lei et al. Reference Lei, Yuckin and Rooney2019; Moore et al. Reference Moore, Burdick, Peter and Keirstead2012); alters nutrient stocks (e.g., Meyerson et al. Reference Meyerson, Vogt, Chambers, Weinstein and Kreeger2000; Yuckin and Rooney Reference Yuckin and Rooney2019); and creates a tall, dense canopy that shades out other wetland plants (e.g., Hirtreiter and Potts Reference Hirtreiter and Potts2012). Unfortunately, because invasive P. australis is so widespread in North American wetlands (Carson et al. Reference Carson, Lishawa, Tuchman, Monks, Lawrence and Alberta2018; Catling and Mitrow Reference Catling and Mitrow2011), management of established populations is often restricted to ongoing asset-based protection and containment. For example, a survey of 285 U.S. land managers by Martin and Blossey (Reference Martin and Blossey2013) found managers spent >US$4.6 million yr−1 on P. australis suppression. In Ontario, municipalities reported spending Can$2.8 million to manage P. australis in 2019 alone (Vyn Reference Vyn2019). Given the large amount of public funds directed to invasive P. australis suppression, it is critical that the efficacy of management actions be evaluated.

The application of either glyphosate- or imazapyr-containing herbicide is the most common management action applied to P. australis in North America (e.g., Hazelton et al. Reference Hazelton, Mozdzer, Burdick, Kettenring and Whigham2014; Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Fant, Steger, Hartzog, Lonsdorf, Jacobi and Larkin2017; Martin and Blossey Reference Martin and Blossey2013). However, glyphosate and imazapyr application to control invasive species in standing water is prohibited in Canada, though an imazapyr formulation permissible for use in standing water is presently under consideration by the Pest Management Regulatory Authority (Health Canada 2020). Consequently, studies on the efficacy of herbicide in P. australis control are nearly all based in the United States. Most studies that used herbicide to control large populations report success in reducing the abundance of P. australis (e.g., Bonello and Judd Reference Bonello and Judd2020; Rohal et al. Reference Rohal, Cranney, Hazelton and Kettenring2019), but eradication is difficult to achieve (e.g., Quirion et al. Reference Quirion, Simek, Dávalos and Blossey2017), and most caution that repeated control measures are required to suppress regrowth (e.g., Bonello and Judd Reference Bonello and Judd2020; Lombard et al. Reference Lombard, Tomassi and Ebersole2012).

The record of herbicide-based P. australis control in achieving recovery of wetland floristic quality is mixed. In the absence of other conservation or land management mandates, recovery should target a vegetation community that resembles the community present in equivalent edaphic and hydrologic conditions where P. australis never invaded (i.e., the reference condition; sensu Stoddard et al. Reference Stoddard, Larsen, Hawkins, Johnson and Norris2006). Some studies report an increase in native vegetation (e.g., Farnsworth and Meyerson, Reference Farnsworth and Meyerson1999) or floristic quality (e.g., Bonello and Judd Reference Bonello and Judd2020) and an increase in similarity to reference vegetation community composition within 3 yr (e.g., Zimmerman et al. Reference Zimmerman, Shirer and Corbin2018) of P. australis removal using glyphosate. Yet, other studies using glyphosate or imazapyr herbicides do not observe improvements in floristic quality (e.g., Judd and Francoeur Reference Judd and Francoeur2019) and report that treated vegetation communities do not resemble reference conditions after herbicide treatment (Rohal et al. Reference Rohal, Cranney, Hazelton and Kettenring2019). Given the range of herbicide formulations, marsh types (tidal, riverine, freshwater coastal, etc.), landscape contexts, and invasion histories being compared, it is not yet possible to predict where herbicide treatment will achieve recovery of a desired vegetation community and where it will not. Studies that characterize baseline conditions (e.g., pretreatment stem densities and floristic diversity), document key covariates like water depth, explicitly define restoration targets, and implement experimental controls are needed to advance our understanding of why some projects are more successful than others.

The purpose of our study was to assess the efficacy of invasive P. australis control in biodiversity hot spots on the north shore of Lake Erie, including two provincial parks that are Important Bird Areas, one of which is designated a UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve, and a Ramsar wetland. The work we present here comes from the first large-scale (435 ha) application of glyphosate-based herbicide directly over standing water to control P. australis in Canada. This unprecedented action was pursued by provincial managers because of the direct and immediate threat the extensive P. australis invasion presented to multiple species at risk, including plants, herptiles, and marsh birds (OMNRF 2017). We used a spatially replicated before–after–control–impact (BACI) design with control and treatment plots paired by water depth (10 to 48 cm) to allow us to quantify the influence of water depth on treatment efficacy. First, we assessed how effective the aerial application of a glyphosate-based herbicide was at suppressing P. australis when applied over standing water of varying depths. Second, we assessed the initial recovery of vegetation in the first 2 yr posttreatment along the same water-depth gradient, comparing recovering vegetation to reference emergent and meadow marsh vegetation communities.

Materials and Methods

Study Location

Our study took place in two marsh complexes located on the north shore of Lake Erie: Long Point peninsula and Rondeau Provincial Park. These Great Lakes coastal marsh complexes are approximately 165 km apart and are directly connected to their respective bays and sheltered from Lake Erie proper by sand bars (Figure 1). Long Point and Rondeau represent more than 70% of the remaining intact wetlands on the north shore of Lake Erie, and as such provide habitat for rare and at-risk species (Ball et al. Reference Ball, Jalava, King, Maynard, Potter and Pulfer2003). These ecosystems, however, are threatened by invasive Phragmites australis ssp. australis, likely haplotype M (Wilcox et al. Reference Wilcox, Petrie, Maynard and Meyer2003). Of the 217 species designated as Species at Risk under Ontario’s Endangered Species Act (S.O. 2007 c.6), 25% are directly threatened by invasive P. australis, including 24 species of vascular plants (Bickerton Reference Bickerton2015).

Figure 1. Placement of control and treatment 1-m2 plots to assess efficacy of glyphosate-based herbicide treatment on Phragmites australis in the western portion of Long Point peninsula (A) and Rondeau Provincial Park (B), located on the northern shore of Lake Erie. Reference condition plots were established in Long Point (A) in meadow marsh and emergent marsh communities. Each reference condition point consists of three independent 1-m2 plots spaced a minimum of 10 m apart.

Phragmites australis Aerial Treatment

The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (OMNRF), in partnership with the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC), and the Ontario Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks (OMECP) obtained an Emergency Registration (no. 32356) under the Pest Control Products Act from Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulation Authority and a provincial Permit to Perform an Aquatic Extermination of invasive P. australis in standing water. In September 2016, 335 ha of P. australis was treated by licensed contractors in the western portion of Long Point peninsula, and 100 ha was treated in Rondeau Provincial Park. The treatment used glyphosate (Roundup® Custom for Aquatic & Terrestrial Use Liquid Herbicide, Bayer CropScience, Whippany, New Jersey, USA) combined with a nonionic alcohol ethoxylate surfactant (Aquasurf®, registration no. 32152, Brandt Consolidated, Springfield, IL, USA). Using a helicopter for aerial application (Eurocopter A-Star equipped with GPS guidance and Accu-flo boom nozzles, Marseille Provence Airport, Marignane, France), 4,210 g ae glyphosate ha−1 as an isopropylamine salt, combined with Aquasurf® nonionic surfactant at 0.5 L ha−1, was applied at a rate of 8.77 L ha−1, with a total spray mix of 70 L ha−1. We provide details on the concentration of glyphosate in water, sediment, and biofilms following herbicide treatment in companion papers (Beecraft and Rooney Reference Beecraft and Rooney2020; Robichaud and Rooney Reference Robichaud and Rooney2021). In February 2017, the treated marsh in Long Point was mowed using a Marsh Master™ (Baton Rouge, LA, USA) or rolled with a drum pulled by an ArgoTM track vehicle (New Hamburg, Ontario, Canada) to knock down standing dead culms of P. australis. No mulching took place, and mowing versus rolling depended on equipment availability and site accessibility, with the Marsh MasterTM able to reach sites to the north and west that the ArgoTM could not. Mechanical secondary treatment did not take place in Rondeau Provincial Park.

Field Methods

In August 2016, we established eighty 1-m2 plots in Long Point peninsula (n = 40) (Figure 1A) and Rondeau Provincial Park (n = 40) (Figure 1B). We then marked plot corners with flagging tape, metal stakes, and a GPS/GNSS unit with submeter accuracy (SX Blue II, Geneq, Montreal, QC, Canada) to ensure the exact locations could be resampled in subsequent years. We situated the plots in dense P. australis (>20 stems m−2) in a stratified-random manner, such that in each marsh treatment (n = 20 per marsh) and control (n = 20 per marsh) plots were paired by water depth, ranging from 10- to 48-cm deep (Supplementary Table S1). This water depth represented the range of standing-water depths across which dense invasive P. australis occurred in our study area (Figure 2). Low-density P. australis patches were excluded, as they were not candidates for herbicide application. In Rondeau Provincial Park, land managers were able to preserve patches to serve as control sites spatially mixed among the treated P. australis, whereas in Long Point, the entire western region of the marsh was treated, and control sites were in a similar area of marsh about 2 km to the east (Figure 1).

Figure 2. Differences in standing-water depth between the control and treatment plots among the 3 yr. Plots in Long Point and Rondeau Provincial Park are combined. Figure created with ggplot2 (Whickham Reference Whickham2016). Error bars represent standard deviation.

All plots were surveyed in August 2016, before treatment, and resurveyed in August 2017 and August 2018: 1- and 2-yr post-herbicide application. In Rondeau Provincial Park, one control plot was accidentally sprayed with herbicide, resulting in 39 control and 41 treatment plots. In 2018, a second Rondeau Provincial Park control plot became inaccessible, leaving 38 control and 41 treatment plots. At each plot, we measured relevant ecological variables and vegetation community composition. We characterized the vegetation community composition of the plots based on the percent cover of all plant species and nonliving cover, such as the litter and standing dead of all species and open water, using a modified Braun-Blanquet cover-abundance method (Wikum and Shanholtzer Reference Wikum and Shanholtzer1978). Percent cover was considered from a single canopy layer, so that each quadrat added up to 100% (±10%), and species present at less than 1% cover were recorded as 0.05% to document their presence. All invasive P. australis stems, living and dead, were counted in each quadrat. Percent incident light reaching the substrate or water surface was measured using a LI-COR LI-1500 light sensor logger with two LI-190 Quantum sensors (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) that measures photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) in the 400- to 700-nm waveband (in µmol m−2 s−1), which permitted simultaneous measurement of the intensity of incident PAR and PAR passing through the canopy. Precautions were implemented to reduce damage to the plots, including avoiding trampling by having all technicians walk in a single file with one in the lead to find the plot and then guide others in. We remained outside the plot and did measurements by reaching in, taking care to avoid damaging any plants within or around the perimeter of the plot (e.g., no bending stems, stripping leaves, affecting cover or height of plants). Voucher specimens for identification were taken from outside the plot. We then followed our single-file path out of the area to minimize additional trampling.

Reference Vegetation

In 2017 and 2018 in Long Point, we also characterized the resident vegetation community composition (henceforth “reference condition”) using the methods specified earlier. Reference condition sites were along a similar range of water depths (10 to 56 cm), which encompassed meadow marsh (shallow standing water, hummock-forming sedges [Carex spp.] and grasses (e.g., bluejoint grass [Calamagrostis canadensis (Michx.) P. Beauv.]), and emergent marsh (deeper standing water, robust emergent vegetation [e.g., Typha spp.]). We established thirty 1-m2 plots in 2017, and 21 in 2018, with all plots a minimum of 10 m apart and a maximum of 1.6 km apart (Figure 1). The plots were spread equally between meadow (n = 15) and emergent marsh (n = 15) in 2017, but slightly favored emergent marsh (n = 12) over meadow marsh (n = 9) in 2018, as we discarded four plots that had water depths <10 cm.

Statistical Methods

Phragmites australis Suppression

As a significant interaction effect is the hallmark of an effective treatment in a BACI design, we used two-way ANOVAs (type III SS) with treatment (control or herbicide-treated) and year (2016 to 2018) as fixed factors to test for the effect of herbicide application on total and live invasive P. australis stem density. We also applied two-way ANOVAs (type III SS) to test for differences in canopy height (cm), and percent incident light (%). To meet assumptions of normality in residuals, we log10 transformed percent incident light. As Long Point had secondary treatment to reduce standing dead biomass, and Rondeau did not, we also compared total stem density and percent incident light (PAR penetration) in the treatment plots between locations and years (2017 and 2018) with two-way ANOVAs. Where there was a significant effect of a fixed factor, and not the interaction term, we conducted a Tukey’s honest significant difference test. All univariate analyses were carried out using the car package (Fox and Weisberg Reference Fox and Weisberg2019) and agricolae package (de Mendiburu Reference de Mendiburu2020) in R v. 3.6.2 (R Core Team 2016).

Efficacy of Herbicide along a Water Depth Gradient

To assess how effective glyphosate-based herbicide application was along the water-depth gradient, we compared live invasive P. australis stem density in treatment and control plots 1 yr after treatment (i.e., 2017 data) using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with treatment as a fixed factor and water depth as a covariate.

Vegetation Community Response to Treatment

To assess whether the vegetation community composition changed in response to herbicide treatment, we conducted a two-way permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) with treatment and year (2016 to 2018) as fixed factors. We applied a general relativization so that percent cover added up to 100% for each plot and removed any species that occurred in two or fewer plots (10 species were removed). Because the number of control and treatment plots was unequal, we used random sampling with replacement that was stratified based on treatment and year. Thirty-eight plots from each treatment and year combination were randomly chosen for each PERMANOVA iteration, which we ran 500 times, and we then took the average of each test statistic. This analysis was performed using PC-ORD 7 (McCune and Mefford Reference McCune and Mefford2015).

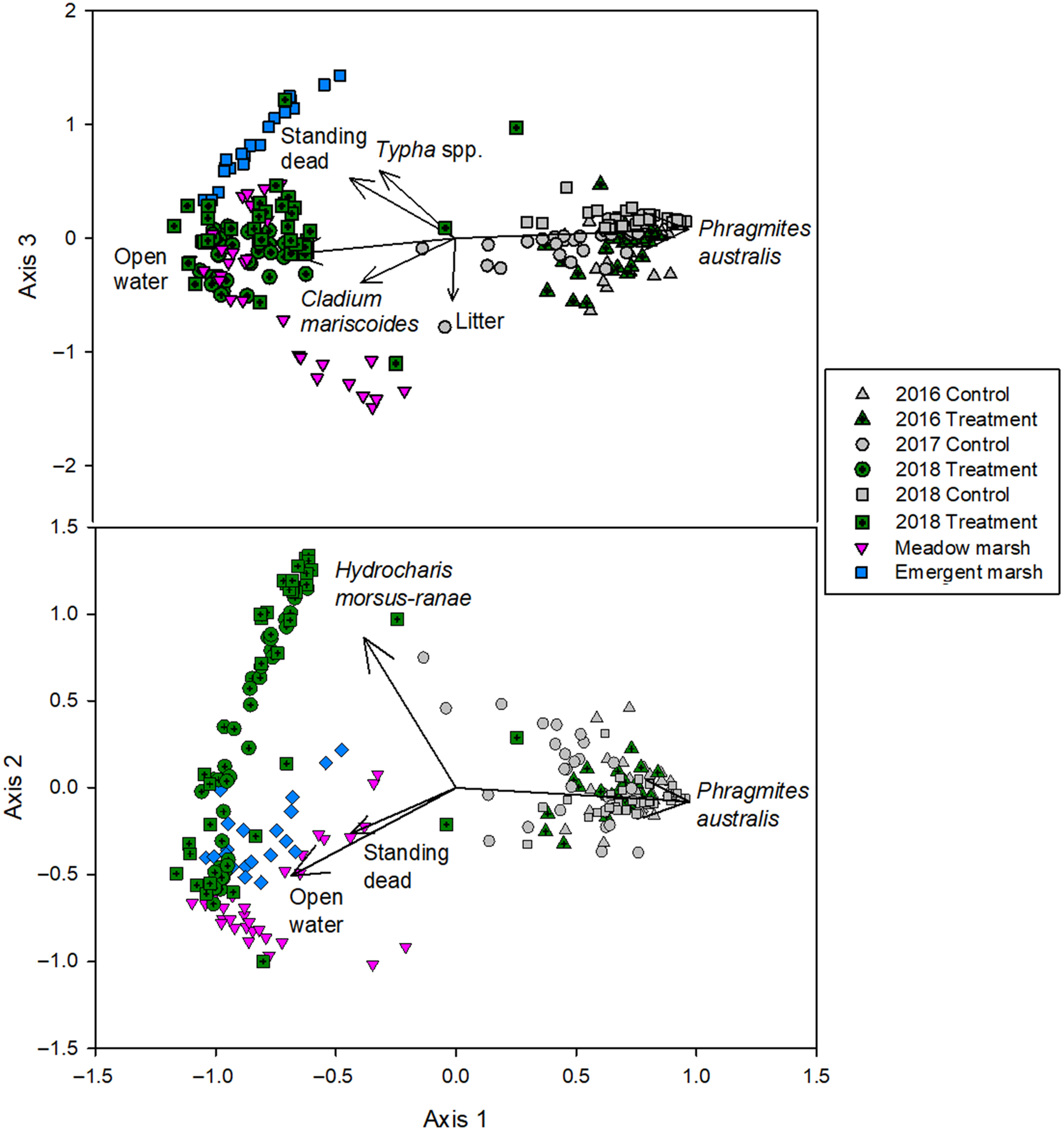

To visualize vegetation composition changes in the treatment plots from 2016 to 2018, we conducted a nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination using a Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix. We combined the vegetation composition data from the control and herbicide-treatment plots with the data from the reference condition plots, which we coded as either meadow marsh or emergent marsh based on water depth and dominant vegetation. We then conducted a general relativization, so that each plot summed to 100%, and removed any species that had two or fewer occurrences in the data set (17 total). This analysis was performed using PC-ORD 7 (McCune and Mefford Reference McCune and Mefford2015).

Results and Discussion

Suppression of Invasive Phragmites australis

For every variable related to invasive P. australis, there was a significant interaction between treatment and year, indicating that herbicide successfully suppressed invasive P. australis in treated plots (Figure 3; Supplementary Table S2). In 2017, we observed a 99.7% reduction in live P. australis stem density (per square meter) in treated plots compared with control plots: on average, there were 0.1 (SD = 0.6) live invasive P. australis stems m−2 in treatment plots compared with 36.8 (SD = 15.3) live invasive P. australis stems m−2 in control plots (Supplementary Table S3). In 2018, there was a 94.7% decrease in live P. australis stem density in treated plots compared with control plots: an average of 1.5 (SD = 5.6) live stems m−2 in treatment plots and 29.8 (SD = 12.3) live stems m−2 in control plots (Figure 3A). The suppression efficacy (e.g., stem density reduction) reported by studies of glyphosate-based P. australis management varies quite substantially from lows of 50% to 60% (e.g., Ailstock et al. Reference Ailstock, Norman and Bushmann2001; Farnsworth and Meyerson Reference Farnsworth and Meyerson1999) to highs of >90% (e.g., Derr Reference Derr2008; Zimmerman et al. Reference Zimmerman, Shirer and Corbin2018). As such, our results are on the high end of reported suppression efficacy.

Figure 3. There was a significant interaction between treatment type and year for all variables related to Phragmites australis suppression: live P. australis stems m−2 (A), total P. australis stems m−2 (B), canopy height (cm) (C), and percent incident light reaching substrate (D). This represents the clear effect of glyphosate-based herbicide at removing P. australis from targeted areas. Error bars represent the standard deviation. Created with ggplot2 (Whickham Reference Whickham2016).

The first year after treatment, only 1 of 40 treated plots had live P. australis. This plot contained four live ramets but expanded 7-fold to 28 ramets the following year. This is equivalent to the live stem density of untreated plots in 2018 (average = 29.8 live P. australis stems m−2, SD = 12.3), illustrating how quickly P. australis recolonization can occur. In the second year after treatment, P. australis had recolonized four additional plots, at densities from 1 to 22 live P. australis stems m−2 (Figure 3A). This rapid expansion and reinvasion from small remnants of P. australis mirrors the results of long-term monitoring studies (e.g., Lombard et al. Reference Lombard, Tomassi and Ebersole2012; Quirion et al. Reference Quirion, Simek, Dávalos and Blossey2017). For example, after glyphosate was used to suppress P. australis, 13.6% of sites exhibited regrowth the following year (Quirion et al. Reference Quirion, Simek, Dávalos and Blossey2017). It is important to recognize that P. australis management typically entails two distinct phases. An initial large-scale treatment with herbicide reduces the extent and density of established P. australis, achieving the objective of broad “suppression.” Afterward, management enters a second “containment” stage, when follow-up spot treatment is required as part of routine maintenance. Quirion et al. (Reference Quirion, Simek, Dávalos and Blossey2017) determined continued containment and spot treatment can keep maintenance costs low, as the probability of reinvasion significantly decreases as invasive P. australis–free duration increases, with no regrowth documented after 4 yr of consecutive absence (Quirion et al. Reference Quirion, Simek, Dávalos and Blossey2017). This emphasizes the importance of long-term monitoring and appropriate project budgeting for follow-up control to prevent reestablishment of invasive P. australis. Additionally, any herbicide used to control P. australis should coincide with herbicide monitoring, as glyphosate can accumulate in soils (Myers et al. Reference Myers, Antoniou, Blumberg, Carrol, Colborn, Everett, Hansen, Landrigan, Lanphear, Mesnage, Vandenberg, vom Saal, Welshons and Benbrook2016; Robichaud and Rooney Reference Robichaud and Rooney2021), plant litter (Sesin et al. Reference Sesin, Davy, Dorken, Gilbert and Freeland2020), and wetland biofilms (Beecraft and Rooney Reference Beecraft and Rooney2020), especially with repeated applications.

There was no difference in live stem density between Long Point, where secondary treatment occurred, and Rondeau Provincial Park, where it did not, after treatment (two-way ANOVA F(1, 78) ≤ 0.88, P ≥ 0.350; Supplementary Table S4). However, there were more total (i.e., dead and living) stems in Rondeau compared with Long Point after treatment occurred (two-way ANOVA F(1, 78) = 4.29, P = 0.042). The percent of PAR reaching the sediment also exhibited a significant interaction between location and year (two-way ANOVA F(1, 78) = 8.46, P = 0.005). The mowing and rolling that took place in Long Point the winter after herbicide application reduced the density of standing dead culms (2017 average 14.0 total stems m−2, SD = 21.5), permitting greater light penetration (68.8% [SD = 26.2%] of PAR reached the substrate in treated plots) in the following summer (2017). In contrast, an average of 87.6 total stems m−2 (SD = 49.1) remained standing in treated plots in Rondeau, permitting only 44.3% (SD = 23.2%) of incident PAR to pass through the canopy in 2017. Yet total stem densities decreased further in 2018 (average 2.8 total stems m−2 [SD = 7.16] in Long Point and 44.8 total stems m−2 [SD = 30.9] in Rondeau), and light penetration reached equivalent levels in 2018, with an average of 56.2% penetration (SD = 28.1%) in Long Point and 66.8% penetration (SD = 25.0%) in Rondeau. Increasing light penetration can encourage greater seedling establishment (Michinton et al. 2006) and promote native species recovery. Secondary treatment that moves litter of all species into the water may also speed litter decomposition (Völlm and Tanneberger Reference Völlm and Tanneberger2014; Yuckin Reference Yuckin2018), further enhancing seedling emergence to facilitate passive restoration of treated areas. However, where secondary treatment to mow or roll is not possible, our results suggest standing dead culm densities and light penetration approach equivalent levels within 2 yr in Great Lakes coastal marshes.

Efficacy of Herbicide along a Water-Depth Gradient

We observed no effect of water depth on the efficacy of invasive P. australis suppression (ANCOVA F(1, 77) = 0.08, P = 0.784; Supplementary Figure S1), nor was there an interaction between herbicide treatment and water depth (ANCOVA F(1, 77) = 0.04, P = 0.836), indicating that glyphosate was equally effective across the water-depth gradient along which dense invasive P. australis occurred (10 to 48 cm). Whereas in semiarid regions drier sites may result in less successful herbicide-based P. australis suppression, as water stress limits the translocation of the herbicide in the plant (Rohal et al. Reference Rohal, Cranney, Hazelton and Kettenring2019), our study indicates water depth does not inhibit adsorption by plant leaves and translocation into rhizomes.

Vegetation Community Response

Lake Erie water levels have been higher than average since treatment occurred in 2016 (DFO 2019), which has resulted in flooding throughout the marsh and a vegetation community that reflects prolonged high water levels. While flooding is necessary to maintain these marshes, prolonged periods can negatively impact marsh vegetation (van der Valk Reference van der Valk2005), and recent work by Keddy and Campbell (Reference Keddy and Campbell2019) suggests that four consecutive years of flooding is enough to drown marsh plants in Lake Erie coastal marshes. Prolonged flooding also limits seedbank regeneration (Keddy and Reznicek Reference Keddy and Reznicek1986). Meadow marsh is less flood tolerant than other vegetation communities and is typically among the most species-rich community in coastal marshes (Keddy and Campbell Reference Keddy and Campbell2019; Reznicek and Catling Reference Reznicek and Catling1989). Yet maintaining floooding over 30 cm can prevent P. australis seedling emergence (Baldwin et al. Reference Baldwin, Kettenring and Whigham2010; Norris et al. Reference Norris, Perry and Havens2002). As such, it is likely that the high Lake Erie water levels after initial herbicide treatment have aided the suppression of invasive P. australis, while influencing native vegetation recovery.

Vegetation species richness had no significant differences between treatments (two-way ANOVA F(1, 233) = 0.37, P = 0.544), among years (two-way ANOVA F(2, 233) = 3.01, P = 0.051), or an interaction (two-way ANOVA F(2, 233) = 2.87, P = 0.059). Despite this, the vegetation community composition in the plots that were treated with herbicide were compositionally different from the control plots following herbicide treatment (PERMANOVA, pseudo- F(2, 222) = 44.77 (SD = 5.33), P = 0.001 (SD < 0.001); Supplementary Table S5). The final NMDS ordination was a three-dimensional solution, with an instability of <0.0001 after 121 iterations and a stress of 8.94 (Figure 4). The proportion of total variance explained was 0.931 (axis 1: 0.618; axis 2: 0.213; axis 3: 0.100). All species and cover class vectors and their correlations with site scores are presented in Supplementary Table S6. The differences along NMDS axis 1 are driven primarily by P. australis abundance. In 2016, before treatment occurred, both control and treatment plots exhibited high P. australis abundance. However, 1 yr after herbicide treatment, in 2017, the treatment plots create a new space in the ordination defined by a vegetation community that contains no invasive P. australis and continue to occupy this space 2 yr after treatment, in 2018.

Figure 4. The final 3D NMDS ordination solution, using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix. Control and treatment plots were measured in 2016, before glyphosate-based herbicide treatment occurred, and in 2017 and 2018. Reference plots were sampled in 2017 and 2018. Black vectors represent reasonably correlated (r2 ≥ 0.150) cover classes.

The reference vegetation plots separate into two unique vegetation communities, meadow marsh and emergent marsh, along axis 3 (Figure 4). Meadow marsh was more diverse than emergent marsh and was characterized by C. canadensis, a mix of sedges (e.g., water sedge [Carex aquatilis (Wahlenb.)] and woolly-fruit sedge [Carex lasiocarpa (Ehrh.)]), and other herbaceous vegetation (e.g., smooth sawgrass [Cladium mariscoides (Muhl.) Torr.]). In contrast, emergent marsh is characterized by high Typha spp. abundance, the majority of which is likely the hybrid cattail [Typha × glauca Godr. (pro sp.)], though positive identification based on morphology can be challenging in the field. Treated plots fall in the middle of these two reference communities, indicating they are like, but do not exhibit the same composition as, reference communities 1 and 2 yr after treatment.

After 2 yr, more than half of the treatment plots had a community composition that was distinct from the reference condition plots and the control plots. Axis 2 explains the community composition of the treatment plots that either have a high abundance of European frog-bit (Hydrocharis morsus-ranae L.) or open water and emergent vegetation (e.g., Typha spp.). Hydrocharis morsus-ranae is a small, free-floating aquatic plant native to Europe, Asia, and Africa that was introduced in Canada in 1932 (Catling et al. Reference Catling, Mitrow, Haber, Posluszny and Charlton2003). It was present in both Long Point and Rondeau before treatment and often co-occurred with invasive P. australis. The average percent cover of H. morsus-ranae in treatment plots before they were treated was 1.73% (std = 2.86%). Robust emergent vegetation has been demonstrated to facilitate the establishment of H. morsus-ranae in Great Lakes wetlands by reducing wave action and wind energy (Monks et al. Reference Monks, Lishawa, Wellons, Albert, Mudrzynski and Wilcox2019). While H. morsus-ranae was ubiquitous in both marshes, the removal of P. australis led to an expansion in H. morsus-ranae cover, increasing to 33.6% (std = 29.8%) 1 yr after and 48% (std = 38.7%) 2 yr after P. australis treatment.

In situations of secondary invasion, we must address whether the secondary invader exerts less negative influence on the invaded ecosystem than the original invader. Unfortunately, less has been published about the effects of H. morsus-ranae invasion on freshwater wetlands in North America than has been published about P. australis. A recent review of H. morsus-ranae in North America by Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Ottaviani, Naddafi, Dai and Daolin2018) concluded that dense mats created by H. morsus-ranae can have “profound negative” effects on native aquatic plant diversity, excluding important native species, such as the carnivorous common bladderwort (Utricularia vulgaris L.) (Catling et al. Reference Catling, Spicer and Lefkovitch1988), although a more recent study concluded that H. morsus-ranae did not have a negative effect on native plant species richness in Ontario wetlands (Houlahan and Findlay Reference Houlahan and Findlay2004). Hydrocharis morsus-ranae invasion also influences the invertebrate community. Except for chironomids, which Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Kopco and Rudstam2015) concluded were more abundant in H. morsus-ranae–invaded areas, invertebrate richness and abundance were reduced by H. morsus-ranae (Catling et al. Reference Catling, Mitrow, Haber, Posluszny and Charlton2003; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Kopco and Rudstam2015). More studies on invertebrates and wetland food webs are warranted before we conclude that H. morsus-ranae is less harmful than P. australis. Of note, high water levels in Lake Erie (DFO 2019) have likely facilitated H. morsus-ranae by providing more open water habitat and inhibiting seedbank emergence. Lower lake levels could reduce the prevalence of this secondary invader in marsh where P. australis has been treated with herbicide.

Suppression is not only about controlling stem density or area of P. australis, but also requires managers to account for propagule pressure to limit reinvasion (e.g., Rohal et al. Reference Rohal, Cranney, Hazelton and Kettenring2019). Where P. australis is abundant, rhizomes and seeds contribute to the establishment or spread of populations at short and long distances, respectively (Albert et al. Reference Albert, Brisson, Belzile, Turgeon and Lavoie2015), with seed dispersal being recorded up to 500 m (McCormick et al. Reference McCormick, Brooks and Whigham2016). Thus, without coordination at a landscape level, it is likely P. australis propagules from surrounding sources will reach the treated area and initiate reinvasion.

Reinvasion and secondary invasions by nonnative species present a challenge in restoration (Kettenring and Adams Reference Kettenring and Adams2011; Pearson et al. Reference Pearson, Ortega, Runyon and Butler2016). Nonnative species are common in restored wetlands, and when coupled with a lack of native propagules, can be a reason restoration projects do not meet their targets (Bonello and Judd Reference Bonello and Judd2020; Matthews and Spyreas Reference Matthews and Spyreas2010). Our study is not the first to report a secondary invasion following P. australis suppression: herbicide treatment of P. australis–invaded Great Lakes coastal marshes in Detroit resulted in dense populations of H. morsus-ranae (Judd and Francoeur Reference Judd and Francoeur2019). Legacy effects because of established P. australis, such as alterations to nutrients (D’Antonio and Meyerson Reference D’Antonio and Meyerson2002; Yuckin and Rooney Reference Yuckin and Rooney2019) and litter production (e.g., Holdredge and Bertness Reference Holdredge and Bertness2011), and shifting environmental conditions (Pearson et al. Reference Pearson, Ortega, Runyon and Butler2016) in and around Lake Erie, for example, nutrient pollution (e.g., Mohamed et al. Reference Mohamed, Wellen, Parsons, Taylor, Arhonditsis, Chomicki, Boyd, Weidman, Mundle, Van Cappellen, Sharpley and Haffner2019) and climate change (e.g., Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Zhao, Hein-Griggs, Janes, Tucker and Ciborowski2020), increase the likelihood of reinvasion and secondary invasions.

With the current distribution and level of establishment of invasive P. australis in North America, most control projects must focus on suppression, containment, and asset protection rather than aiming for complete eradication (i.e., Quirion et al. Reference Quirion, Simek, Dávalos and Blossey2017). While eradication may not be possible, ecological benefits can be achieved through continuous maintenance and containment at relatively low costs (e.g., Turner and Warren Reference Turner and Warren2003). Annual applications of herbicide to smaller areas (e.g., hand-treating 5% of an invasive population) can effectively reduce P. australis populations over time (Turner and Warren Reference Turner and Warren2003), keeping them at an “ecologically benign” level. For example, wetland bird communities responded positively to P. australis when it occupied a small portion of the marsh in Long Point, with high species richness along the edges of stands (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Badzinski, Petrie and Ankney2010). In contrast, once P. australis accounted for nearly 70% of the land cover in these marshes, wetland bird communities using P. australis were reduced to a subset of the diverse community using remnant marsh (Robichaud and Rooney Reference Robichaud and Rooney2017). It is also possible to promote plant species diversity by reducing P. australis abundance such that light availability and other ecosystem effects (e.g., litter accumulation) do not impede native species establishment (Carlson et al. Reference Carlson, Kowalski and Wilcox2009). Recent assessments have demonstrated marsh birds (Tozer and Mackenzie Reference Tozer and Mackenzie2019) and at-risk plant species (Polowyk Reference Polowyk2020) are responding positively to P. australis suppression in Long Point. Monitoring the responses of wetland biotic communities to the large-scale suppression of an established invasive species is important, as results allow managers to accurately assess the outcomes of control projects.

Long-term monitoring to evaluate potentially harmful contamination is an essential component of herbicide-based invasive species control projects. Over the duration of this project, the concentrations of herbicide in the water and soil in Long Point and Rondeau never approached 0.8 ppm, the concentrations deemed concerning for the protection of aquatic life by the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (Robichaud and Rooney Reference Robichaud and Rooney2021). However, it is important to acknowledge that this project occurred in protected areas where herbicide had not been previously applied. With multiple applications, glyphosate can accumulate in sediment (e.g., Battaglin et al. Reference Battaglin, Meyer, Kuivila and Dietze2014; Myers et al. Reference Myers, Antoniou, Blumberg, Carrol, Colborn, Everett, Hansen, Landrigan, Lanphear, Mesnage, Vandenberg, vom Saal, Welshons and Benbrook2016) or wetland vegetation (Sesin et al. Reference Sesin, Davy, Dorken, Gilbert and Freeland2020), and there are potential sublethal effects of glyphosate in aquatic systems (e.g., Beecraft and Rooney Reference Beecraft and Rooney2020; Vera et al. Reference Vera, Lagomarsino, Sylvester, Pérez, Rodríguez, Mugni, Sinistro, Ferraro, Bonetto, Zagarese and Pizarro2010). Small, repeated herbicide applications may reduce overall herbicide use (Turner and Warren Reference Turner and Warren2003), keeping costs and contamination risks low by avoiding the need for large-scale retreatment following reinvasion (Quirion et al. Reference Quirion, Simek, Dávalos and Blossey2017). Follow-up P. australis spot treatment and herbicide monitoring thus require long-term budget allocations but given that 25% of Ontario’s species at risk are threatened by P. australis invasion (Bickerton Reference Bickerton2015), it is a worthwhile investment.

The question remains whether native species will be capable of recolonizing and persisting in areas where invasive P. australis has been dominant for over two decades, given the continued persistence of P. australis propagule sources in the local seedbank and the surrounding landscape. Passive restoration is a technique commonly used in wetlands due to the persistence of native species’ seeds (Galatowitsch Reference Galatowitsch, Finlayson, Everard, Irvine, McInnes, Middleton, van Dam and Davidson2018). It has the benefits of being relatively inexpensive and rapid (Gornish et al. Reference Gornish, Lennox, Lewis, Tate and Jackson2017), as it relies on propagules that are present within, or can easily reach, the target area. As such, the species present in seedbanks are an important determinant of the success of passive restoration. However, seedbanks in areas that have been invaded typically have a lower native species density and richness while containing a higher richness or abundance of nonnative species (Gioria et al. Reference Gioria, Jarošík and Pyšek2014). The diversity in P. australis seedbanks appears to vary depending on the system and history of invasion, though some studies suggest it is sufficient for passive restoration (e.g., Hazelton et al. Reference Hazelton, Downard, Kettenring, McCormick and Whigham2018; Howell Reference Howell2017). For example, the seedbank in P. australis stands in brackish tidal wetlands was more species rich than the standing vegetation suggested (Baldwin et al. Reference Baldwin, Kettenring and Whigham2010). These seedbanks do contain viable P. australis seeds, however, and stands that persist within 500 m of the treated area can be a source of viable seeds, which would lead to reinvasion (Ailstock et al. Reference Ailstock, Norman and Bushmann2001; McCormick et al. Reference McCormick, Brooks and Whigham2016). Removing the stress or pressure of an invasive species may not be enough to result in a native community that meets restoration goals, including creating a diverse plant community capable of resisting reinvasion by P. australis (Peter and Burdick Reference Peter and Burdick2010).

Active revegetation, or reseeding treated areas, provides an opportunity for managers to promote native plants with attributes that can resist further invasion (Byun et al. Reference Byun, de Blois and Brisson2018; Simmons Reference Simmons2005), though seeding wetland species is not without challenges (e.g., England Reference England2019). Invasive species are typically early colonizers of disturbance, making it important for managers to identify (1) the legacy of the previously established invasive species and (2) which native species can tolerate local conditions and invasion pressure (Hess et al. Reference Hess, Mesléard and Buisson2019). Trait-based restoration approaches may be applied to select native species that can tolerate the environmental conditions of the site and influence biotic interactions (Laughlin Reference Laughlin2014). This approach requires a clear understanding of the dynamics of the system and the fitness and niche differences between native species and nonnative species (MacDougall et al. Reference MacDougall, Gilbert and Levine2009) to select appropriate candidate species for seeding. Active restoration can lead to more native species cover and richness compared with passive restoration and may permit cultivation of species to increase biotic resistance to reinvasion (Byun et al. Reference Byun, de Blois and Brisson2018). Whether or not managers decide to conduct passive or active restoration is a choice that is ultimately dependent on their goals, though there is a growing body of literature that suggests planned revegetation could be an effective way to prevent the reestablishment of nonnative species (Byun et al. Reference Byun, de Blois and Brisson2018).

Acknowledgments

We thank the graduate students and technicians who made this project possible: Graham Howell, Sarah Yuckin, Daina Anderson, Jody Daniel, Heather Polowyk, and Calvin Lei. Thank you to the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, the Nature Conservancy of Canada, and Expedition Helicopters of Cochrane who carried out the aerial application of herbicide. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their improvements to the finished paper. This work was supported by NSERC Discovery Grant no. RGPIN-2014-03846 and MNRF non-consulting agreement MNRF-W-(12)3-16 to RCR and by Ontario Graduate Scholarship (OGS) to CDR. We declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/inp.2021.2