Questions about consciousness pervade the social sciences, whether social scientists admit to them or not. Consciousness lies at the heart of efforts to reconcile the material and ideational worlds, the human agent and social structures, and positivism and interpretivism (Wendt Reference Wendt2015, 1–2, 14–20). Further, consciousness is deeply intertwined with important phenomena like rational reflection, intentionality, and emotions. Debates in philosophy of mind between dualism, monism, pan-psychism, and alternatives have profound theoretical consequences for International Relations (IR), framing epistemological and methodological debates about which actors to study and how (Jackson Reference Jackson2008). And though behaviourist approaches allow scholars to avoid thorny consciousness-related questions and instead focus on actions, consciousness is vital to many behaviours' conceptual coherence in the first place. If human beings did not experience fear consciously, it seems unlikely that IR would have incorporated a functionalist account of fear into the security dilemma (Bleiker and Hutchison Reference Bleiker and Hutchison2008, 116)?

Perhaps the most confounding question consciousness poses for IR relates to conceiving of states as actors. States have long been the paramount actor in the discipline and popular discourse frequently anthropomorphizes states. But should states be seen as ‘real’ agents and, if so, are they conscious agents, merely impacted by consciousness or somewhere in-between? In his seminal 2004 article, Wendt (Reference Wendt2004) argued that states should be considered corporate persons or unitary intentional agents. Yet, he also recognized that this account of personhood was incomplete without consciousness, which has been considered a vital aspect of personhood ever since René Descartes famously wrote ‘I think, therefore I am’ (cogito ergo sum). These limitations seemingly lingered, as more than a decade later Wendt published Quantum Mind and Social Science (2015), advocating quantum consciousness theory as a means of connecting the physical and ideational worlds. But, despite generating enormous scholarly interest,Footnote 1 Wendt's book received criticism for ‘drawing on minority and even fringe speculations’ to construct a comprehensive theory of reality (Jackson Reference Jackson2016, 1154). Though quantum consciousness theory certainly has its advocates, it remains entirely unverified and as yet unverifiable – both physicists and metaphysicians have little agreement over the ontology of consciousness or even how best to investigate the issue. From the perspective of IR, Wendt's pan-psychism, considered alongside his previous interventions on state personhood, raises further questions regarding what distinguishes states from other groups if all of social life consists of shared quantum mental states. Understanding whether states possess a unique type of consciousness among political groups thus also requires engaging with IR and political theory debates on the ontology of the state. Though perhaps a more tractable issue than the ontology of consciousness, the ontology of the state remains hotly contested and committing to any approach threatens to alienate vast portions of the discipline before even wading into the complexities of philosophy of mind (see Ringmar Reference Ringmar1996; Bartelson Reference Bartelson1998; Wight Reference Wight2006, 215–25).

Instead of dwelling on these thorny ontological debates, in this article I demonstrate why advocates of multiple ontologies of both consciousness and the state can incorporate a pragmatic notion of state consciousness into their theorizing. I argue that states, insofar as they are typically understood and analysed as unitary ‘persons’ in IR scholarship, exhibit most (if not all) key characteristics of consciousness, including both its psychological and phenomenological aspects. Further, drawing on recent work by Eric Schwitzgebel, I demonstrate why certain IR scholars (namely ontological realists) might be forced to accept that states probably are really conscious, in the sense that states are complex superorganisms whose parts function together to produce consciousness irreducible to individuals. This theoretical intervention, I argue, not only reshapes how scholars conceive of state agency and model the international system – it also offers IR enormous explanatory power when applied. I demonstrate this by applying a model of an international system with conscious states to recent debates over how ontological security literature approaches levels of analysis issues. Ontological insecurity, I argue, need not be seen as a faulty extension of human psychology to the state-level. Scholars can also reasonably refer to state-level qualia like ontological anxiety that are emergent phenomena, irreducible to human beings within the state. Though this view might lead to problematic anthropomorphism, it will help combat the false parsimony of previous models and, when coupled with epistemological humility, can help move forward numerous related debates.

Why consciousness? The limits of state personhood

To address the question of whether the state is conscious, one must first begin with the question of whether and how the state can even coherently be thought of as a unitary actor capable of possessing properties like consciousness. Though anthropomorphic language attributing agency to states is common in IR scholarship and everyday political discourse, the position that states are agents is by no means universal. Many scholars have argued that this language is merely a useful shorthand and that literal interpretation reifies what should be understood as metaphorical usages (Gilpin Reference Gilpin1984, 301; Ferguson and Mansbach Reference Ferguson and Mansbach1991, 369–72; Wight Reference Wight2004; Lomas Reference Lomas2005). Anti-state personhood thinking typically begins from the premise that ‘only individuals act’ and states are simply figments of people's imagination (Gilpin Reference Gilpin1984, 301). If this is true, invocations of state agency should be seen as metaphorical – a shorthand used to avoid complicated statements about arrays of individuals acting in unison or within organized hierarchies.

But despite the parsimony of this individualism, it exhibits multiple problems that limit its utility for IR scholarship. First, it cannot adequately account for the irreducibility of collective intentions outlined by Pettit's (Reference Pettit, Goldman and Whitcomb2010) ‘discursive dilemma’ – the logical inequivalence of statements about aggregated individual state officials' actions and those of states as agents. In many cases, individuals act by collectivizing rationality, rather than acting independently and having their efforts summed into those of a collective, making methodological individualism yield incomplete accounts of collectives' actions. Second, it exhibits a neurochauvinist tendency that privileges human beings as actors but does not explain what is truly unique about them or their neuron-based brains that allows them to uniquely come together into monological agentic systems. Though I comment more on the problems of neurochauvinism later, recent work in philosophy of mind has demonstrated how neurochauvinist and anthropocentric approaches to understanding psychological predicates undermine scholarship's explanatory power in numerous fields (Figdor Reference Figdor2018). Third and relatedly, this metaphorical approach to the state raises ontological and epistemological issues on the necessity and utility of reduction for analysis. For example, explanations about states' behaviour that reduce to individual agents' deliberative minds, according to most materialist ontologies, can be further reduced to billions of neurons operating in complex patterns. If materialism is true, why stop reduction at the layer of the human mind rather than at the larger layer of the state? Reduction may or may not be possible all the way down, but reducing farther than necessary can make causality evaporate into impractical layers of complexity (Schwitzgebel Reference Schwitzgebel2016b, 882).

For these reasons, most IR scholars, political theorists, and international legal scholars have adopted the position that states are corporate persons, capable of acting as unitary agents. According to Wendt (Reference Wendt2004, 295), persons need not be understood solely as human beings, but rather can be identified via four attributes that make them ‘intentional – purposive or goal-directed – systems’.

(1) a unitary identity that persists over time; (2) beliefs about their environment; (3) transitive desires that motivate them to move; and (4) the ability to make choices on a rational basis, usually defined as expected-utility maximization.

Wendt's account of state personhood depends on a materialistFootnote 2 (scientific realist) metaphysics and a notion of either collective agency supervening on individuals' decisions or emerging from them – both of which mean that methodologically individualistic reductionist approaches can offer less explanatory power than holist ones. But, notably, many of Wendt's arguments about supervenience or emergence could plausibly transcend his metaphysics and offer scholars who are anti-realists with regards to the state a rump model of collective agency. For example, a post-positivist who does not view ontology as meaningfully prior to epistemology (Hansen Reference Hansen2006; Schiff Reference Schiff2008) might view agency as a socially constructed quality typically attributed to the socially constructed individual, but might also agree that it applies equally well to the state, considering the way states are understood and constituted in relevant discourses.

Yet, despite Wendt's account of state personhood's resonance with certain commonplace statements about state actions and utility for scholarship on certain subjects, it is problematically thin. It contains a limited functionalist account of state decision-making that leaves open important questions about what type of agent a state really is. For example, Christian List (Reference List2018, 297–98) points out that this functionalist definition of agency can easily apply to not only simple animals like bats, but also robots and even thermostats, as thermostats have ‘beliefs’ about the current temperature, ‘desires’ about an optimal temperature and the capacity to make choices to regulate the temperature through cooling and heating systems. Does attributing functionalist ‘desires’ to thermostats not undermine the term's resonance, which stems from the fact that ‘desires’ in humans have a phenomenology? Drawing on Thomas Nagel's (Reference Nagel1974) famous phrasing, saying that a thermostat ‘desires’ a temperature neglects the fact that the term ‘desire’ connotes something to humans precisely because there is something it is like to have desires and this qualia is deeply entangled with desires' function. Further, Wendt's labelling the state person a ‘rational actor’ raises the question of whether states are purely rational social robotsFootnote 3 or more complex, human-like conscious actors with emergent identities and emotions that can skew what's traditionally understood as rational decision-making.

Because of the limitations of this approach, even Wendt (Reference Wendt2004, 312) recognized that this definition of personhood is incomplete. Namely, Wendt points out that ‘intuitively consciousness seems essential to being a person, since without it we wouldn't know what it was like to be a person, which we do in fact know’. In other words, the functionalist definition of personhood that Wendt applies to the state stems from a problematic objectification of subjective conscious experience and thus remains incomplete without accounting for its first-person aspects. Intentionality, as used by Wendt and others to describe group agents, thus deliberately does not address the full range of anthropomorphic statements frequently made about states. For example, while intentionality grounds a literal reading of the statement ‘North Korea conducted a nuclear test’, it provides far less guidance on how to read the also common statement ‘North Korea is angry’ (Haberman and Sanger Reference Haberman and Sanger2018; Thiessen Reference Thiessen2018). Contra Jackson (Reference Jackson2016, 1156), I argue that the concept of consciousness, on some level, is vital to theorizing how and why the latter statement is a meaningful explanation for action. In this sense, I follow much philosophy of mind literature in treating consciousness as a broad concept that links mental experiences and motives to intentionality and action – though some of these phenomena can be understood functionally, a linkage of subjectivity and intentionality follows intuitively from human experience and, understandably, frames IR discourse.

Though, in his article, Wendt (Reference Wendt2004, 312) raised the question of ‘state consciousness’ and offered some speculative thoughts, he left open the question of whether states should be considered conscious, writing that the relative dearth of IR literature on state emotions or state subjectivity indicates that it might be a bridge too far for the field. When he did return to this idea more than a decade later, he did so solely with an unproven metaphysics liable to alienate many mainstream social scientists. Yet, in the decade and a half since Wendt's article on personhood, mainstream IR has still seen an explosion of work attributing irreducible emotions, insecurities, and self-reflexive identities to states. For example, Jonathan Mercer (Reference Mercer2014; see also Sasley Reference Sasley2011; Crawford Reference Crawford2014) argues that group emotions are emergent ideational structures that cannot be ontologically reduced to individuals. This group emotion, Mercer argues, provides a basis for understanding group identity, a key subject for IR scholarship. Similarly, Emma Hutchison (Reference Hutchison2016) has theorized how emotions can help constitute communities, while Hall and Ross (Reference Hall and A2019, 2) have written about popular emotion as an analytical category separate from individual ‘affective experience’. Considering this work on the irreducibility of group emotions alongside scholarly consensus on state personhood as intentionality, the time seems ripe for alternative examinations of whether such collective emotions might be attributable to states as persons and, if so, whether this might necessitate a broader notion of state consciousness.

Defining and identifying consciousness across species and systems

Beyond aforementioned ontological questions, part of the difficulty in addressing whether states are conscious stems from the diversity of definitions for ‘consciousness’. Because of its intimacy with human experience, in varying capacities consciousness has been studied by philosophers and scientists for centuries, including Descartes' famous self-examination and later Hume's reflections on how bundles of perceptions related to individual identity. But, in response to the dominance of behaviourism and cognitivism in psychology and other social sciences, a new interdisciplinary field of Consciousness Studies has emerged since the 1980s explicitly focused on the ontological, epistemological, and methodological issues associated with integrating human behaviour with the internal subjective experiences of human minds (Overgaard Reference Overgaard2006). Yet, despite this field's more focused interdisciplinary examination of these issues – evidenced by the popularity of the now quarter-century old University of Arizona ‘Toward a Science of Consciousness’ conference and the Journal of Consciousness Studies – the field has made little headway settling on how to define its subject of study. While certain models of consciousness like Tononi's (Reference Tononi2004) Integrated Information Theory (IIT) and Dretske's (Reference Dretske1997) representationalist account have garnered disciples, Consciousness Studies remains deeply divided over fundamental issues that limit scholars' ability to move beyond problematic definitions to robust theories.

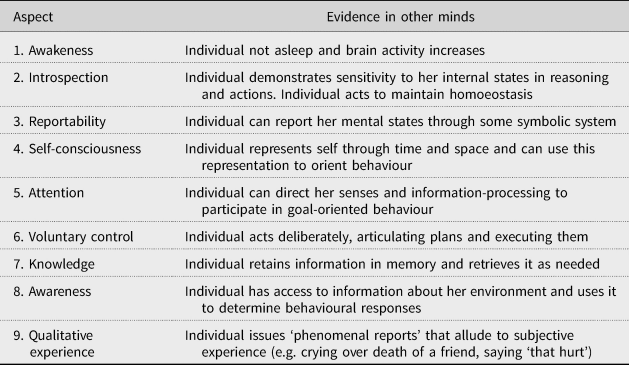

For this reason, prominent scholarly definitions of consciousness vary considerably. Ram Virmal (Reference Virmal2009), for example, identifies forty ‘meanings (or aspects)’ of consciousness in philosophy of mind with differing implied ontologies. Some recurrent themes Virmal identifies are the ability to ‘discriminate stimuli’, ‘report information’, ‘monitor internal states’, a ‘stream’ of awareness, and ‘subjective’ or ‘perceptual experience’. Notably, the first three of these descriptors might plausibly fall under an expanded rubric of intentionality, while the latter three likely do not. Much scholarship, alternatively, has built on Nagel's (Reference Nagel1974) idea that what makes consciousness unique is its first-person subjectivity – that there is something it is like to be a conscious entity. To best account for the complexity and pluralism associated with consciousness, I cobble together multiple aspects of consciousness as criteria, recognizing that they overlap significantly and may be inseparable in practice if not in theory. The term ‘aspects’ implies that together they constitute manifestations of the same larger, multi-faceted but poorly understood phenomenon without committing to any specific ontology of consciousness. Yet, despite their inherent connectedness, viewing them as aspects also offers the benefit of an artificial divisibility of consciousness. This facilitates the creation of a spectrum from partially conscious entities that merely demonstrate a few aspects of consciousness to fully conscious ones like humans that demonstrate all of them.Footnote 4 To better understand these aspects' implied metaphysics, I draw on David Chalmers' (Reference Chalmers1997, 23–26) typology of nine varieties of consciousness and oft-cited distinction between the easy (psychological) problem of consciousness and the hard (phenomenological) one.

According to Chalmers, psychological aspects of consciousness are those that might be explicable solely in terms of their function and thus potentially relate to intentionality, as defined in the above-mentioned IR literature. Though they are often accompanied and influenced by phenomenal subjective experiences, psychological aspects can, given the theoretical limitations of current science, potentially be understood via a materialist model of the brain as an electrochemical computer. By contrast, according to Chalmers the ‘hard’ question of consciousness refers to phenomenological consciousness (alternatively referred to as subjective experience or qualia). Because of the confusion this distinction often raises, to distinguish the phenomenological aspects of consciousness from the deeply intertwined psychological ones, Chalmers (Reference Chalmers1997, 83–94) invokes a variety of thought experiments. The most straight-forward of these has to do with the logical possibility of zombies – an organism physically identical to a human being that lacks qualia. If a human being named John stubs his toe, he will receive and process signals in his brain warning him not to repeat the same action, but he will also experience pain. By contrast, when John's zombie twin stubs his toe, he will receive the exact same signals in his brain as a warning, but they will not be accompanied by the qualia of pain. Chalmers argues that the intuitive logical possibility of zombies implies that human beings recognize qualia are distinct from functionalist accounts of brain processing.

Building upon Chalmers' dichotomy between psychological consciousness and typology of nine ‘varieties’, in Table 1 I outline nine aspects of consciousness and how they are typically identified in ‘other minds’ (addressed more completely in the next section). As the table makes clear, intentionality could potentially overlap with certain aspects of consciousness, but consciousness is a broader, richer concept.

Table 1. Nine aspects of consciousness and identification in ‘other minds’

As Chalmers (Reference Chalmers1997, 25) notes, these aspects oftentimes overlap in significant ways and are sometimes further divisible. Yet, despite the problems associated with this typology, offering these nine aspects alongside one another allows scholarship to compare consciousness in different entities, both human and non-human, much in the way that neurologists distinguish between ‘minimally conscious states’ and full consciousness, and have even created spectrums of consciousness (Charland-Verville et al. Reference Charland-Verville, Vanhaudenhuyse, Laureys, Gosseries and Miller2015, 50). For instance, a man in a coma who has internal subjective experiences, but no voluntary control over his movements or information processing may be regarded as possessing a very low level of consciousness. Likewise, Artificial Intelligence (AI) robots might be considered awake (according to functionalist criteria), able to process information and able to exert voluntary control over their movements. Further, they might even be capable of introspection and production of a working model of the self (Franklin Reference Franklin2001). However, the best possible current AI technology does not seem to have phenomenological consciousness and thus should not be regarded as fully conscious. Though viewing these aspects as criteria is useful for purposes of comparison, scholars typically have thresholds for considering something conscious. For example, a thermostat's responsiveness to its environment is so simplistic and unidimensional that scholars typically would not regard it as even minimally conscious.

Before moving on to the next section, it's worth considering one prominent view of consciousness called illusionism, held by many materialist philosophers (Dennett Reference Dennett1993; Frankish Reference Frankish2016). Illusionists hold that phenomenal consciousness is illusory and that ‘the task for a theory of consciousness is to explain our illusory representations of phenomenality, not phenomenality itself’. Unlike radical realists who believe ‘radical theoretical innovation’ is necessary to explain phenomenological consciousness or conservative realists (‘weak illusionists’) who attempt to explain phenomenological consciousness as an emergent outcome of material brains, illusionists treat phenomenal properties as utterly deceptive (Frankish Reference Frankish2016, 11–14). Dennett (Reference Dennett2016), for example, compares phenomenal experience to a stage magician tricking people into believing in real magic. The debate between illusionists (weak and strong), property dualists, substance dualists, and panpsychists relates to the ontology of consciousness, a subject too complex to outline here. However, I mention here the existence of illusionists because of the utility in considering their viewpoint later in my argument.

Consciousness beyond one's own mind

Beyond aforementioned ontological issues, two other streams of criticism warrant addressing, as they allude to common sense, epistemological, and agent-structure problems important to conceptualizing state consciousness in IR. In this section, I address the interwoven issues of neurochauvinism, anthropocentrism, and contiguism, as well as the ‘problem of other minds’. Though these streams do not exhaust criticism of recent arguments about state consciousness, they do provide the greatest barriers to entry for IR scholars interested in philosophy of mind arguments and thus warrant consideration prior to this article's central claims.

Neurochauvinism refers to a tendency in philosophy of mind to believe that consciousness requires either neurons or structures very similar to neurons and neuronal networks (Schwitzgebel Reference Schwitzgebel2015, 1716–17). This view is intuitively problematic to those with functionalist inclinations towards consciousness – if aliens that act exactly like humans but with vastly different internal systems appear on earth, why should they not also be considered conscious? But it has been articulated to varying degrees by prominent scholars like Ned Block (Reference Block and Block1983) and John Searle (Reference Searle1984, Reference Searle1980) and it aligns fairly well with the view of consciousness implied in much IR scholarship (that human beings are conscious, but robots and larger diffuse systems are not). This view breaks down on closer scrutiny. One prominent rebuttal is a Ship of Theseus-esque thought experiment that considers what would happen if one replaced every neuron in another human's brain with a tiny microchip that performed the exact same functions as the neuron it replaced. Given that scientists currently have no insight into what might possibly make neurons achieve consciousness but not functionally identical microchips, neurochauvinists have no grounds for believing that the individual would lose her consciousness during the experiment. A second rebuttal speculates that, given the size and variability of the universe, in some other context with vastly different resources, consciousness might have appeared in vastly different ways.

This tendency towards associating consciousness with humans or human-like animals also leads to a bias Schwitzgebel (Reference Schwitzgebel2015) calls morphological prejudice or ‘contiguism’. This refers to the belief that only spatially contiguous entities can possibly be conscious. To dispel this idea, Schwitzgebel (Reference Schwitzgebel2015, 1699–1701) proposes a logically possible organism called the Sirian supersquid whose brain communicates via light signals rather than electrochemical ones, allowing the supersquid's brain to be dispersed throughout its tentacles and not centrally located like in humans. Supersquids possess all the same aspects of consciousness – psychological and phenomenological – as human beings. Yet, unlike humans, in times of crisis they detach their tentacles and disperse them. Though the supersquid is no longer spatially contiguous, the various parts of its brain housed in its tentacles continue to communicate via light signals, which travel so fast that the squids' processing does not slow down discernibly. Importantly, these limb-roving supersquids are not ‘reporting back’ to any centralized system, but rather remain cognitively integrated throughout their parts. If one is inclined to believe that spatially distributed supersquids are still conscious, then spatial contiguity ceases to be a criterion for consciousness.Footnote 5

In many ways, intuitive neurochauvinism, anthropocentrism, and contiguism with regards to consciousness are natural considering that the best data human beings have about consciousness comes from their own experience. Though one can observe functional correlates of consciousness via other humans' and animals' behaviour or brain scans, the only direct evidence for complete consciousness is one's own experience. Since this is attached to a contiguous human body and typically only discussed with other humans, it oftentimes leads to intuitive anthropocentric, neurochauvinist, and contiguist assumptions. But it's important to recognize that these tendencies stem from confusing correlation with causation. If consciousness is understood according to reasonable criteria as in the prior section, then any complex informationally-integrated systems – especially those of complexity rivalling the human brain – should be considered candidates.

But though these thought experiments demonstrate that consciousness might appear in an array of systems, determining this consciousness is another matter. These tendencies, though problematic, allude to the problem of other minds – the difficulty of ‘how to justify the almost universal belief that others have minds very like our own’ (Hyslop Reference Hyslop and Zalta2014). This problem has remained a persistent issue in philosophy for centuries and resolving it fully seems dependent on developing a complete and accurate theory (complete with an ontology) of consciousness beyond a mere definition or set of criteria. Outside of radical solipsists, most people assume that other human beings and many animals have consciousness like their own and, thus, are not deceptive zombies. But the basis for this assumption is contested. Current science provides insufficient information for making conclusions about people's consciousness beyond a truncated functionalist definition and even illusionists have not yet mapped the intricacies of the brain systems they claim give rise to the ‘illusion of consciousness’. How, then, are scholars to determine whether others are truly conscious?

In determining whether other individuals or entities are phenomenologically conscious, the best third-person data come from verbal phenomenal reports that allude to phenomenal experience (e.g. ‘That hurts’) beyond intentions and desires, particularly when these data contain detail that resonates with first-person experiential data (Chalmers Reference Chalmers2010, 37–51; Feest Reference Feest2014). In essence, this involves inference to the best explanation in light of limitations on available data (Avramides Reference Avramides2019). For animals that possess no language, the best possible evidence is not verbal, but behavioural phenomenal reports. When a dog squirms from a pinch or offers human-like expressions, many owners reasonably assume the dog is phenomenally conscious. Of course, complex organisms like dogs often exhibit functional responses to experiences that are not necessarily indicative of their phenomenal qualities; for example, in addition to being an unpleasant experience, pain from a pinch is a signal to avoid something and thus zombie dogs might conceivably react in similar ways. However, certain types of reports that do not serve obvious immediate functional roles, especially given the context in which they occur, allude to assumed phenomenal experiences existing alongside psychological processing. One has no way of knowing if a dog is simply a deceptive zombie seeking the benefits of human presumptions of phenomenological consciousness, but this problem persists for any type of identification of others' phenomenal consciousness, including through explicit verbal reports (Schwitzgebel Reference Schwitzgebel2016a, 230–31).

In determining whether states are conscious, I begin from a pragmatic, explicitly non-neurochauvinist, non-anthropocentric, and non-contiguist posture. In this sense, I am open to the idea that anything, from aliens to zoos, could be conscious to some degree, so long as it demonstrates sufficient evidence that it possesses some aspects of consciousness. Further, following my pragmatic approach to the problem of other minds, I identify these aspects with an agnosticism towards various types of data, using reductionist analysis and functionalist analogy when possible and inference from phenomenal reports when not. When examining the information processing capacity of a computer, I suggest breaking down the processes it employs and determining whether they are analogous to science's best understanding of those that produce consciousness in humans. When determining whether a computer is phenomenally conscious, I suggest asking if it issues phenomenal reports not associated with functional properties (i.e. not indicating that it is overheating simply as a pre-programmed response to indicate adverse effects on performance). This pragmatism is a necessity given the limitations of current science and my efforts to offer a pragmatic explanation not wedded to an uncertain ontology.

Group minds and state consciousness from Le Bon to Schwitzgebel

Though the field of Consciousness Studies has emerged only in the last few decades, the idea that groups – especially those groups organized for political action – might have ‘minds of their own’ to some degree is a longstanding one. Indeed, beyond scattered metaphorical invocations of the body politic in the writings of Aristotle and Hobbes (Smith Reference Smith2018), the idea gained firm ground with the birth of social psychology in the late 19th century. In his seminal book The Crowd (1897 [Reference Le Bon1895], 2), Gustave Le Bon first suggested that individuals in mobs join together into a ‘collective mind’ that suppresses individuals' personalities and inhibitions, though he did not robustly theorize this collective mind as a system with emergent properties. Ideas about mob psychology and subservience to political leadership only became more widespread with the militarism and populism of World War I and the Russian Revolution (see, e.g. Trotter Reference Trotter2005 [1916]; McDougall Reference McDougall1920). Shortly after the war, Sigmund Freud wrote Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (Reference Freud1957 [1919]) in which he posited that individual libidinal desire helps explain why individuals become attached to charismatic leaders and exhibit oftentimes peculiar behaviour at their command. Freud suggested that many intra-psychic dynamics manifest collectively in social groups (Pick Reference Pick1995), undermining a sharp division between individual and social psychology and facilitating his later political thought, which often depended on analogies from individuals to groups (see, for example, Freud Reference Freud and Jones1939). Though this early psychological work reflected most directly on how group dynamics might relate to intra-psychic ones, somewhat similar theories had already been developing relatively independently in sociology, though with fewer explicit efforts to link emergent social structures to individual minds. In the late 19th century, for example, French sociologist Émile Durkheim (Reference Durkheim, Coser and Halls1998 [1893], 38–39) wrote of ‘collective…consciousness’ as an emergent social system ‘with a life of its own’, irreducible to individuals. Durkheim's vision, though, did not dwell on internal mental states and thus has notable dissimilarities with recent Consciousness Studies literature.

Given the political focus and origins of this early work on group minds, it's unsurprising that scholars began to apply it to the modern state, a form of political grouping which became increasingly dominant over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries. This application raised questions of what distinguishes the state from other political groups with ‘minds of their own’, as well as why it might be a better or worse candidate for such emergent characteristics, implicating important questions on the history and ontology of the modern state. In 1896, for example, French sociologist René Worms expanded the organicism of many of that period's sociologists to describe the state as one of many types of social organisms with a ‘collective consciousness’ capable of producing ‘unanimous’ sentiments in individuals. At the time of his writing, though, the inchoate character of neuroscience and scholarship theorizing the state prevented Worms from elaborating on this idea and fully theorizing the contours of state consciousness (Park Reference Park1921, 6). Alternatively, in his reading of multiple early theorists of group minds, legal philosopher Hans Kelsen (Reference Kelsen1924) drew on Freudian ideas to theorize the state as a unique type of group unified by both a charismatic leader and shared ideas in individuals' psyches. He thus dismissed reading the state via Durkheim's notion of an emergent collective consciousness existing ‘out there’ in the world, separate from individuals' minds. Kelsen's theorization saw the state as an ideational structure that imposes a socially produced ego and superego onto members' inner lives as they submit to its dictates due to a deeper unconscious libidinal desire. Thus, it rhymes with much post-structuralist scholarship's emphasis on the discursive social production of the state and the impact this discursive production has on the psyches of individuals. In this sense, Kelsen's account of the state could reasonably inspire a similar post-structuralist ‘as if’ account of state consciousness, in which the discursively-produced ideational state is articulated as a conscious group mind (see Schiff Reference Schiff2008). Still, Kelsen problematically grants primacy to the individual and her mind, exhibiting similar issues to aforementioned methodological individualist approaches.

Despite these early examples, as IR developed within the context of 20th century social science, it became dominated by behaviouralist and rational choice approaches that lessened interest in internal mental states in individuals, let alone in states (Saurette Reference Saurette2006, 499). Further, most scholars adopted theorizations of the state characterized by ontological realism – the view that states exist ‘out there’ in the world – and thus they grew to devalue consideration of ideational structures intertwining with material ones, emphasizing instead the modern material apparatus of political authority the state embodied. Thus, most IR ontologies of the state have fallen into what Ringmar (Reference Ringmar1996) has labelled the ‘[political] realist’ camp or the ‘pluralist’ camp, which I believe are best understood via their outside-in and inside-out approaches to states' ontologically ‘real’ existence. Outside-in [political] realist scholars take the state as an a priori actor, bound together by the logic of conflict, with implicit independent ontological standing, precluding meaningful theoretical reduction. By contrast, inside-out pluralist models of the state emphasize the historical evolutions in different sub-state groups and technologies that led to their integration in the modern state and thus they question treating the state as a unitary actor, emphasizing instead the competition between these groups and forces within the state as an arena. Ringmar notably dissents from both and instead advocates understanding the state not as it ‘really’ is, but rather through how it is understood through narratives in political discourse, a move which could conceivably inspire a similar post-structuralist ‘as if’ account of state consciousness. But, to the extent that the dichotomy Ringmar identifies has persisted in much IR scholarship, his typology essentially transforms questions of state consciousness from theoretical to empirical. Both camps agree that states represent ‘real’ material structures, but simply disagree on whether they're integrated sufficiently coherently to be thought of as unitary conscious agents. This empirical question of states' informational integration provides a segue into Schwitzgebel's recent intervention on the production of group consciousness and also helps distinguish the state, as a modern, informationally integrated system whose complexity might rival that of a human brain, from other, far less sophisticated groups that cannot.

Schwitzgebel's realist response

Philosopher Eric Schwitzgebel's (Reference Schwitzgebel2015) recent intervention on the subject of state consciousness is particularly insightful in overcoming the pluralist vs. political realist divide among ontological realists. Instead of asking whether the state in the abstract is a conscious agent, he turns to the question of whether a particular state – the Unites States – defined intuitively as consisting of all the things, people and sociocultural institutions under its ambit, is sufficiently well-organized to be considered not only a unitary agent, but also a conscious one according to a materialist ontology of consciousness. Defining materialism as the belief in philosophy of mind that the reason one possesses consciousness – including both psychological and phenomenological qualities – is because ‘the material stuff out of which you are made is organized the right way’, Schwitzgebel (Reference Schwitzgebel2015, 1697) answers the question of the Unites States’ potential consciousness ‘probably’, given materialists still limited understanding of the emergence of consciousness in complex systems.

Schwitzgebel begins by noting that, when examined telescopically as a superorganism, the United States possesses many non-trivial non-metaphorical similarities to biological organisms with assumed consciousness. This includes cells and organs (in its citizens and animals), the maintenance of homoeostasis, defence against external threats and the ability to maintain its existence over time (Schwtizgebel refers to states' ability to ‘reproduce’ in new states, but I would add the intergenerational continuity of citizens as an element of states' ‘reproduction’). Further, like brains, the United States possesses ‘complex high order/low entropy information processing’ and ‘sophisticated responsiveness to environmental stimuli’, distinguishing it from less sophisticated, less organized group actors, including pre-state political groupings (Schwitzgebel Reference Schwitzgebel2015, 1706). Is this processing capacity empirically comparable to that of conscious brains? Schwitzgebel notes that human brains contain approximately 1011 neurons, with approximately 103 connections each, firing every several milliseconds. By contrast,

Most people in the United States spend most of their time in visual environments that are largely created by the actions of people (including their own past selves). If we count even 1/300 of this visual neuronal stimulation as the relevant sort of person-to-person information exchange [contributing to the state as a collective system], then the quantity of visual connectedness among people is similar to the neuronal connectedness within the human brain (1014 connections). Very little of the exchanged information will make it past attentional filters for further processing, but analogous considerations apply to information exchange among neurons. Or here's another way to think about the issue: If at any time 1/300th of the U.S. population is viewing internet video at 1 megabit per second, that's a transfer rate between people of 1012 bits per second in this one minor activity alone. Furthermore, it seems unlikely that conscious experience requires achieving the degree of informational connectedness of the entire neuronal structure of the human brain. If mice are conscious, they manage it with under 108 neurons (Schwitzgebel Reference Schwitzgebel2015, 1707).

Because of the simplicity of mouse consciousness that Schwitzgebel uses as a minimum threshold, which is orders of magnitude less complex than the potential capacity of US consciousness, his argument likely applies beyond the Unites States to other states, though it does raise the question of whether small states might be less conscious than bigger ones. Still, to the extent that most small states are able to come together organizationally and fulfil the complex state functions that he describes (defence, homoeostasis, etc.), they likely contain the information processing capacity of a simple animal. These state-level functions require immense amounts of informational-processing from numerous individuals, harnessing resources drawn from all corners of the state. Indeed, any political grouping (among which states are merely a highly organized example) in which a reasonably large number of people exchanges information continuously and a significant amount of this information exchange contributes to the state's higher-order action and processing, should be deemed a candidate for consciousness. Mapping simple state functions onto the eight aspects of psychological consciousness outlined above reveals why nearly all modern states should be considered possibly conscious (Table 2).

Table 2. Mapping state consciousness

Relating these state functions to those in humans makes clear that the massive information-processing roughly approximated by Schwitzgebel (Reference Schwitzgebel2015, 1707) is not simply of the right ‘quantity’ to rival the consciousness of a complex mammal, but also of the right quality – it is ‘goal-directed…[and] flexibly self-protecting and self-preserving’. Indeed, in certain respects, the United States' consciousness seems far more complex than that of average human beings, who could not individually organize complex war efforts or launch space programmes.

Schwitzgebel's argument has sparked a lively debate in philosophy of mind, much of which relates to anti-nesting principles – the idea that a conscious entity cannot either contain conscious sub-parts or depend on their ideational projection – that he dismisses in a brief section of his article (Kammerer Reference Kammerer2015; Schwitzgebel Reference Schwitzgebel2015, 1702–03; Schwitzgebel Reference Schwitzgebel2016b). Other criticisms have examined whether his argument would reasonably apply to other materialist theories of consciousness like IIT (Schwitzgebel Reference Schwitzgebel2012; List Reference List2018). Though these arguments are important for answering the question of whether states are truly conscious, much of their intricacies are irrelevant to the question of whether theorizing the state as conscious offers explanatory power for IR, as they all make either ontological or technical criticisms that begin from the premise that Schwitzgebel's account of the Unites States meets most aspects of consciousness. Further, many critiques based on anti-nesting principles relate to the potential reducibility of state consciousness-related behaviour to individuals, and thus the same criticisms of anti-personhood due to supervenience or emergence and complexity also apply. Nevertheless, a prominent stream of criticism relates to Schwitzgebel's relatively limited engagement with the US potential phenomenal consciousness (Pettit Reference Pettit2018), which I address in the next section.

Addressing state phenomenal consciousness beyond materialist ontologies

Schwitzgebel's account alludes to how states possess the eight aspects of psychological consciousness listed above and it might satisfactorily prove state consciousness for illusionists who do not believe phenomenological consciousness is a distinct phenomenon from computer-like psychological processing. Likewise, non-illusionist materialists who believe phenomenological consciousness is a real but emergent phenomenon stemming from brains' poorly-understood complex information-processing systems might also be inclined to believe that states are good candidates for experiencing qualia (Pettit Reference Pettit2018). But what about those who explain phenomenological consciousness via alternative ontologies? These scholars typically believe that current science's materialist model of the brain is not sufficient to explain consciousness; some other currently unknown factors are necessary for phenomenological consciousness, be it a property (for property dualists), a substance (for substance dualists), or perhaps a poorly-understood effect of physical processes (e.g. the collapsing of the wave function in quantum consciousness theory).Footnote 6 Scholars in these traditions might look at Schwitzgebel's account and conclude that it only serves to deepen understanding of states' intentionality, demonstrating that states are almost fully conscious but actually closer to massive AI computers, lacking qualia, with intentions shaped by founders and operators. Indeed, this vision of the state as an AI computer rhymes with many models of the state as a rational systemic actor reflecting human decisions within them.

While materialists can draw on analogous structures to identify phenomenological consciousness, current science's limitations and the problem of other minds afford non-materialists only phenomenal reports and limited, problematic attempts at reduction. Yet, I argue that states not only issue collective phenomenal reports irreducible to individuals within them, but also that the relevant phenomenology behind these reports similarly cannot be reduced to individual human minds. For this reason, advocates of such alternative ontologies of consciousness have good reason to regard states as fully conscious (including qualia). This approach parallels the contours of much of the aforementioned debate over Schwitzgebel's article and proves the most pragmatic approach given ontological uncertainty. When states are examined telescopically, the phenomenology behind state collective phenomenal reports appears fully integrated into the state system. While individuals are certainly experiential nodes within this system, their phenomenology cannot be understood without reference to the state system, and thus these phenomenal reports cannot be reduced to individuals. Though this argument does not necessarily prove states are phenomenally conscious in their own right, it does provide strong evidence for the pragmatism of treating states as conscious in IR theorizing.

To prove these theoretical points about states' phenomenal consciousness, it's helpful to draw on the concrete example of the 9/11 attacks, a paramount instance of international terrorism. In many ways, terrorism serves as a critical case among international political phenomena for examining qualia's role due to its strong association with collective affective states – international terrorism is defined by its goal of producing in individuals the qualia of terror and exploiting its discomfort to provoke decision-making that deviates from presumably rational responses. But though terrorism is perhaps an extreme example of affective experience shaping foreign policy, recent literature in IR's ‘emotional turn’ has demonstrated that all foreign policymaking discourses have affective components that limit theorization via a rational actor model (Mercer Reference Mercer2010, Reference Mercer2006). For this reason, terrorism can serve as an example to help build theory on state phenomenology.

In the abstract, a state responding to terrorism could involve a simple function of state psychological consciousness – monitoring threats and taking action to prevent future harm – and thus be an extension of state personhood as intentionality. Yet, state responses to major attacks like 9/11 widely discussed in media and society can only problematically be understood via such functionalist analogies, especially when the scale of the attack and the threat it represents are compared to other equivalent threats. For example, why would the 9/11 attacks provoke among Americans a significant and measurable reluctance to fly (Myers Reference Myers2001; Bergstrom and McCaul Reference Bergstrom and McCaul2004) and costly related policy responses, while other plane crashes – many of which were also widely covered in news media and resulted from far more common accidents or pilot errors – did not?Footnote 7 To explain such deviations from rationality in the wake of 9/11 – including deviations in foreign policy – IR scholars have increasingly turned to the qualia the event produced, especially qualia motivated by the events' interpretation through a nationalist lens. For example, Paul Saurette (Reference Saurette2006) has described US foreign policy in the wake of the 9/11 attacks as influenced by a form of social humiliation, experienced by individuals, but not completely reducible to them, while Jenny Edkins (Reference Edkins2002) writes of proliferating feelings of trauma and vulnerability among Americans that shaped notions of post-9/11 securitization and, ultimately, foreign policy. Likewise, Ty Solomon (Reference Solomon2012) draws on a Lacanian framework to demonstrate how the 9/11 attacks produced affective (phenomenal) experience in Americans that was translated into political discourses via ‘emotional signifiers’ (a form of phenomenal report), which, in turn, shaped US foreign policymaking's logics. The affective resonance of the War on Terror's emotional justification, Solomon writes, helps explain support for the policies it entailed. Though the array of subjective experiences these authors identify likely blend together, this literature demonstrates why theorizing terrorism's impact accurately requires consideration of qualia, their translation via phenomenal reports into socio-politically potent emotions and these emotions' complex role in shaping state actions beyond narrowly understood rationality.

The policy responses impacted by post-9/11 qualia, I argue, are best explained as collective phenomenal reports, irreducible to individuals within the state. As Hall and Ross (Reference Hall and Ross2015, 849) theorize, ‘strong affective reactions can upset the trajectory of our thoughts and behaviour’ – beyond simple phenomenal reports like clenched fists and muscle tensing, the qualia of anger also leads to a desire to ‘redress perceived offenses’. In an organized political context like that of a modern nation-state, individual responses to qualia provoked by a terrorist attack do not simply wash out as they are shared socially. Rather, they come together to produce an emergent response that is more than the sum of its parts. For this reason, Hall and Ross (Reference Hall and Ross2015) describe an ‘affective wave’ that swept across the Unites States following the attacks, impacting both citizens and policymakers and ultimately contributing to the broad-reaching policies of the War on Terror, which led to ‘spillover’ aggressiveness in confronting Iraq. To the extent that these actions constituted responses to the qualia provoked in Americans by the 9/11 attacks, I argue that they must be considered collective phenomenal reports. As multiple scholars have argued, the qualia of fear, humiliation and anxiety that Americans' behaviour and rhetoric after the attacks contributed directly to American foreign policy's deviation from what would otherwise be considered rational and proportionate. Though perhaps America could be a zombie state full of zombie citizens imitating the actions of phenomenally conscious ones, inference to the best possible explanation and analogy to the self leads to the conclusion that qualia played a role in shaping the collective phenomenal reports of US foreign policy. And, importantly, if these policy responses are considered phenomenal reports, they cannot be reduced to the actions of individuals without loss of explanatory power. Individuals cannot launch a multi-faceted War on Terror or organize a massive invasion of Iraq – these policies either supervened on the decisions of many Americans or emerged from them.

A sceptic might agree that, in line with consensus about state personhood, US foreign policy after 9/11 is irreducible to individuals and was impacted by individuals' qualia, but object to considering this foreign policy a collective phenomenal report on the grounds that the qualia-related aspect of decision-making is entirely reducible to individuals. Yet, this conclusion is problematic due to the extent to which 9/11-inspired qualia were so deeply conditioned by the state system. Indeed, the idea that emotions – defined both functionally and by their associated qualia – are conditioned by salient socio-political groupings has become a consensus in psychologyFootnote 8 and has even shaped much recent IR literature on state-level emotions (Sasley Reference Sasley2011; Crawford Reference Crawford2014; Mercer Reference Mercer2014). Literature on the emotional impact of the 9/11 attacks similarly found in individuals across the country increased incidences of post-traumatic stress (Silver Reference Silver2002), increased prejudice (Morgan, Wisneski, and Skitka Reference Morgan, Scott, Wisneski and Skitka2011), and feelings of insecurity associated with a shift in policy preferences (Huddy and Feldman Reference Huddy and Feldman2011). Put simply, explaining why individuals thousands of miles from 9/11's devastation would experience more fear and anxiety from the attacks than a commensurate disaster exposing risk in another far-flung region across the globe requires consideration of the state as an integrated system. Though human brains might have been the primary nodes within the state experiencing qualia in response to the attacks,Footnote 9 these qualia were informationally integrated into the larger superorganismic system of the state and explaining them requires reference to the state organizing these experiences into the framework of international politics. Thus, they can no more be reduced to individuals than individual neurons in the amygdala firing in response to a frightful stimulus can be isolated from the cohesive system of the mind that produces the qualia of fear and subsequent phenomenal reports.

The vision of the state as a conscious superorganism emerging from this argument is, like Schwitzgebel's (Reference Schwitzgebel2015, 1699) related materialist argument, ‘conditional and gappy’, in that it is bound by the limitations of current science and could conceivably collapse in the face of future insight. Further, while human beings typically presume their peers are not deceptive zombies due to analogy to the self, intuitive anthropocentrism and contiguism make presuming that the state is not a zombie, with consciousness above that of individual members, far more difficult. This makes sense – it is intuitively difficult to picture the state telescopically, as a superorganism highly-organized around a hierarchical structure whose parts – some of which are presumed to be phenomenally conscious – come together to produce the sufficient conditions for a higher order level of consciousness. Yet, as Huebner (Reference Huebner2014, 120) writes ‘it is just as hard to imagine that a mass of neurons, skin, blood, bones, and chemicals can be phenomenally conscious…The mere fact that it is difficult to imagine collective consciousness does not establish that [conclusion]’. Given the available evidence and the limitations associated with it, I argue that state consciousness is the best conclusion given the data and provides IR with the most explanatory power.

The middle school dance of international politics: debating the ontological security of the ‘conscious’ state

Together, the previous sections have articulated a vision of states as informationally integrated complex systems that exhibit most functional aspects of consciousness, as well as behavioural correlates of phenomenological consciousness – phenomenal reports. Further, I have argued that the relevant phenomenology behind these reports cannot be reduced completely to individuals within the state. Though current science has insufficient basis for concluding whether states possess a coherent ‘stream’ of consciousness at a separate level from the fully conscious beings within them, this possibility cannot be ruled out, despite discomfort with the prospect. Given these findings, I argue that treating states as conscious actors constitutes a pragmatic way forward for IR scholarship, both for post-structuralists interested more in the discursive production of the state as an actor and for ontological realists interested in characterizing the state as it exists in the world. This approach not only provides a deeper understanding of states as persons, but also can provide a more nuanced model of the international system for IR theory that can help move forward multiple outstanding debates. In this section, I outline this model and demonstrate its utility in debates over applying ontological security theory at the state level.

Traditionally, IR scholarship has drawn upon analogies to theorize IR within a cohesive system, most commonly referring to states as billiard balls bouncing off one another or tectonic plates colliding (Krasner Reference Krasner1982). These two prominent early analogies and their cognates treat the international arena as a closed system governed by veritable laws (akin to the laws of physics) and states as inanimate, non-agentic like units operating predictably within these laws' constraints. Notably, many of these physical models preclude variation based on the internal attributes of states – a vision that has cast a shadow over much IR scholarship. Even the advent of early Wendtian ‘thin’ constructivism that differentiated state units based on identity did little to undermine the rationality assumption of prior models, making states' actions as corporate persons somewhat predictable and limiting potential new analogies of states to more complex entities. While critical IR scholarship has launched varied attacks on these existing models, no prominent system-level alternative has emerged to account for the complexity inherent in state agency. With this in mind and, in light of this article's arguments on state consciousness, I argue for a model much more similar to human social interactions. Though states obviously have many dissimilarities to human beings beyond consciousness, I argue that the presumption of state consciousness lends itself to modelling the international system as a ‘middle school dance’Footnote 10 – a delineated social arena made up of conscious adolescent units. While certainly imperfect, this model can prove useful not only in conceptualizing the complexity of conscious state systems interacting, but also help move forward outstanding debates in the discipline.

Unlike a bustling adult cocktail party, the international system, like a middle school dance, is ‘thin’ on social interaction – the main actors are prone to keeping to their corners and interacting primarily with close allies or focusing on introspection. Because adolescents in puberty have only problematic senses of self, the unitary agentive voice with which they speak belies tremendous internal contestation and uncertainty. Yet, from a top-down perspective, any chaperone observing and analysing the system as a whole would find tremendous analytical utility in treating these actors as unitary conscious intentional agents partaking in social interaction. Further, these adolescents cannot be dismissed as purely rational or irrational. Instead, their rationality should be understood as bounded by unique social arrangements and their limited capacity to express themselves coherently and consistently over time. These constraints, I argue, can be theorized both from a bottom-up perspective (analogous to neuroscience's examination of individuals' behaviour via brain functions) and a top-down macro-perspective (analogous to social theory linking outward behaviour to internal mental states). While the bottom-up perspective reveals redundant, contradictory and oftentimes competing internal forces, the top-down perspective emphasizes unitary external actions that are not easily reducible to component parts. This model also emphasizes that, when scholarship assumes the top-down perspective of the chaperone, much as with adolescent students, the subjective contours of state consciousness can only be deduced via indirect behavioural correlates – the problem of other minds persists whether those minds are contained in bodies or spatially-distributed superorganisms. Yet, any chaperone would likely assume the students are not deceptive zombies, taking their phenomenal reports as genuine.

Beyond its potential macro-level analytical utility in understanding international interaction, the middle-school dance model with states as adolescent actors also lends itself to reframing debates over ontological security scholarship, as identity-related anxieties are hallmarks of the human maturation process. Over the past two decades, literature on ontological security in IR has explored the multiple ways states act to secure stable senses of self for various actors. Work on ontological security in IR stemmed from psychoanalyst Laing's (Reference Laing1960) work on individual minds, which was subsequently adapted by sociologists like Anthony Giddens (Reference Giddens1991) and Ulrich Beck (Reference Beck1997) to describe individuals' relationships to social structures. As IR scholars translated the concept to international politics in the late 1990s and early 2000s (see Huysmans Reference Huysmans1998; McSweeney Reference McSweeney1999; Kinnvall Reference Kinnvall2004), it expanded to describe both individual identities' mediation via international politics and, eventually, the actions of states in defence of identities for themselves as ‘persons’ (see Mitzen Reference Mitzen2006; Steele Reference Steele2008). To address the levels-of-analysis issues inherent in taking a concept developed for the individual psyche and applying it to states, scholars have alternatively emphasized the pressure states feel from citizens to create anxiety-reducing routines (Mitzen Reference Mitzen2006, 352), the role of narratives in bridging the individual-state divide (Steele Reference Steele2008, 15–20), and even simply the empirical purchase an expanded notion of security has in explaining anomalies in state behaviour (Mitzen Reference Mitzen2006, 352). In more recent years, this state-level approach has gained enormous traction, yielding significant empirical results and more nuanced theoretical explorations (Subotić Reference Subotić2015; Lerner Reference Lerner2019; Steele and Homolar Reference Steele and Homolar2019). Still, no scholarship on ontological security has robustly argued that anxiety related to ontological insecurity might constitute an irreducible state-level qualia, or, in other words, that states' identity-related insecurity should be considered an aspect of state consciousness.

While ontological security literature has made a notable impact on the IR discipline, efforts to scale up scholarship on individuals' anxieties to states socializing in the international arena have provoked significant criticism. For example, Stuart Croft (Reference Croft2012, 225) has criticized ontological security scholarship in IR for ‘reifying the state’ rather than remaining faithful to Laing and Giddens' insight into individuals, while Chris Rossdale (Reference Rossdale2015, 369), alternatively, has taken issue with how it ‘marginalizes modes of subjectivity which resist the closure of ontological security-seeking strategies’. But by far the most prominent advocate of this line of critique has come from Richard Ned Lebow. According to Lebow (Reference Lebow2016, 35), state-level theories of ontological security depend on a ‘deeply problematic’ notion of state personhood and state identity. Though Lebow (Reference Lebow2016, 22) believes states possess multiple conflicting identifications, he argues that they ‘differ from people in having neither emotions nor reflective selves’ to experience or act upon these identities as agents. This allows state leaders ample leeway in manipulating narratives of multiple possible national identities on offer to legitimize their actions, problematizing any notion of ontological security-seeking as a robust constraint on decision-making. Ultimately, Lebow concludes that ‘[i]t makes no sense to speak of [states’] psychological needs, especially anxiety reduction’ and that ontological security theorists need to ‘exercise more caution and self-restraint’ in connecting individual anxiety-reduction to state actions (Lebow Reference Lebow2016, 36, 43).

To varying degrees, these criticisms rest on a sharp dichotomy between individuals as monological, unitary agents and states as either ‘passive receptacles’ (Lebow Reference Lebow2016, 28, 179) for individuals' projections or apparatuses whose identities are controlled by select powerful individuals. Yet, as demonstrated throughout this article, the constitution of the state as an informationally integrated complex system whose attributes and actions are irreducible to its members is largely an empirical question. To the extent that states can harness a sufficient level of such information-integration to produce collective intentions and phenomenology that supervenes on (or emerges from) the decisions and phenomenology of individuals within them, states can reasonably be understood as conscious, possessing irreducible macro-level emotions like identity-related anxiety that motivate foreign policy. This is not to say that contestation within the state cannot both shape these macro-level effects or exist in conflict with them, just as the monologic ‘stream of consciousness’ in the mind overlies complex, competing inner dynamics (Fernyhough Reference Fernyhough1996). Rather, it simply recognizes that, the state as a system can manage these diverse inputs, harnessing some and disregarding others for what Schwitzgebel (Reference Schwitzgebel2015, 1706) refers to as ‘complex high order/low entropy information processing’ and ‘sophisticated responsiveness to environmental stimuli’ – in other words, foreign policy.

To return to the analogy of adolescents at a middle-school dance, chaperones at the dance serving as observers of students' behaviour would be wise to recognize that these young people possess complex, conflicting underlying senses of self, many of which are vulnerable to manipulation, either by outsiders or base instinctual desires. Further, many of these desires will contradict one another and require management by the larger conscious system. For example, a middle-school student deciding whether or not to dance might simultaneously want to affirm his or her identity by looking ‘cool’ in front of peers, avoid embarrassment that would be detrimental to self-esteem, form lasting friendships that reinforce a sense of self, or even simply pursue the purely monetary interest of winning a bet with a friend. Yet, to the extent that these diverse underlying dynamics come together via a complex system to produce the unitary, irreducible action of dancing, the individual should be considered conscious and the decision reflective of this complete consciousness, which includes psychological and phenomenological aspects. Indeed, a simplified functionalist explanation that ignores the phenomenology of the inner anxieties of the individual and his or her sense of self would seem incomplete in the face of this individual's subjective ontological insecurity. Of course, these students could be deceptive zombies, but their behaviour, coupled with the chaperone's inference to the best possible explanation, would make that conclusion seem unlikely.

Just as in the middle-school dance, state-level actions in pursuit of ontological security can also be understood as the response to state-level qualia, which are the outcome of a complex, informationally integrated conscious system managing competing sub-state pressures, desires, and identity narratives. Indeed, this approach reinforces the utility of examining bottom-up insight into the narrative production of state-level anxieties in tandem with the top-down international political perspective that reflects on irreducible state-level behaviours, just as bottom-up insights into adolescent brain development exist in tandem with the top-down sociological perspective of the chaperone. The idea of state consciousness simply demonstrates that a top-down vision of the state as a unitary conscious actor can have merit beyond pure metaphor, orienting attention to the irreducible contours of state intentionality, which extends beyond mere functionalism to include a host of other aspects of consciousness, including qualia. Of course, one has no way of knowing whether a state is a ‘zombie state’, integrating only deceptive zombies whose phenomenology is not impacted by socio-political mediation. But given the large number of contributing actors, this conclusion seems even more unlikely than a similar one made by a chaperone observing an array of adolescents.

In making this argument, I recognize that the deep anthropomorphism of the ‘middle-school dance’ model will likely make many uncomfortable. Indeed, even as I argue for treating states as conscious, I recognize that their consciousness is likely quite different from that of humans and that their qualia are likely also distinct. Despite the fact that human beings are components of the conscious state system, their aggregation might yield state consciousness that more closely resembles that of a bat, a beehive, or no existing entity at all – this is an empirical question for future research to explore. Yet, by viewing state anxiety as an irreducible qualia, discernible indirectly via its presence in the zeitgeist and state-level phenomenal reports, scholarship can take seriously state-level ontological security literature beyond mere metaphor. Despite its problematic anthropomorphism, the middle-school dance model can help demystify state consciousness in multiple ways. First, because it surfaces vulnerable memories of adolescent insecurities in many readers, it helps an otherwise abstract theoretical debate resonate and encourages the sort of empathy necessary to imagine state consciousness. Second, by demonstrating the applicability of the concept of state consciousness to an outstanding debate in IR, the model encourages application of the conscious state to a variety of other debates in the discipline that are still plagued by limited rationalist assumptions and the dominance of functionalism and methodological individualism. Third and finally, this model suggests paths for investigating state consciousness' contours. For example, scholarship might begin to empirically investigate states' actions both functionally and as phenomenal reports, relating to an underlying irreducible phenomenology. Scholarship can compare and contrast state phenomenal reports to ask what sorts of state-level qualia are most likely to emerge, how these are different from human qualia and how underlying sub-state forces contribute to them. Though an imperfect method, given the limitations of the problem of other minds, it constitutes a pragmatic path forward.

Conclusion

This article has argued that, while it might be impossible given current knowledge to discern whether states are ‘truly’ conscious without further insight into the ontologies of consciousness and the state, IR scholars of a variety of theoretical persuasions can pragmatically incorporate state consciousness into their theorizations. For this reason, I have suggested modelling the international system via analogy to a middle school dance – a thin social environment with complex, incompletely formed actors who nonetheless demonstrate irreducible unitary qualities, especially discernible in top-down analysis. I understand that this argument about state consciousness is speculative and open to criticism. Yet, it does raise important questions for IR scholarship about how the discipline engages with constructivist ideas about the state adapted from humanistic disciplines and also can help undermine the oftentimes problematic dichotomy in much scholarship between individuals as monological conscious agents and other actors as either metaphorical or purely rational. In this sense, this article seeks to provoke unabashed examinations of states as persons beyond functionalism and metaphor, seeing how far personifying language can push the boundaries of the discipline. In turn, the idea of state consciousness can reshape how existing IR scholarship deals with state-level emotions, revenge, resentment, and a host of other ‘feelings’.

Finally, though this article avoids normative argumentation, it's worth noting the ethical dilemmas that arise from the idea that states might meaningfully possess qualia over and above that of humans within them. For example, if states can reasonably be described as ‘feeling’ pain, is committing violence against the state wrong over and above the physical suffering experienced by individuals within it? Further, if phenomenal consciousness is considered a basis for moral standing, should state death be considered a moral wrong, even if all the state's citizens remain alive and gain citizenship in other states? Personifications of the nation or the state have historically been abused by fascist regimes to justify brutal acts against individuals – how can scholarship wrestle with state consciousness without lending ammunition to violent ideologies? Though the idea of state consciousness lends these questions a certain intellectual merit, it does not offer easy answers. My hope is that this article opens new avenues for examinations into the normative aspects of personhood, from animals to human beings, corporations, and even the state. Though these normative questions are deliberately outside this article's focus, they demonstrate the stakes of these questions and the importance of engaging with ideas of macro-cognition and consciousness head-on.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Yale Ferguson, Sean Fleming, Lucas De Oliveira Paes, Shailaja Fennell, Patrick Thaddeus Jackson, Brent Steele, Jaakko Heiskanen, Giovanni Mantilla, Jeffrey Friedman, Allicen Dichiara, and the editors and anonymous reviewers at International Theory.