Introduction

International Relations (IR) has long been the subject of controversies that have called into question its intra-disciplinary cleavages. One of the most important of these is the interrelated matter of global and intellectual hierarchies and IR's relevance as a genuinely ‘international’ endeavor. Since the publication of ‘An American Social Science: International Relations’ by Stanley Hoffmann, the IR discipline has been gripped by a debate: to what extent is IR representative of the experiences of non-Western countries, and are IR theories relevant for grappling with the complexities facing the global ‘rest’?Footnote 1 Owing to historical provenance, its material preponderance, and its institutional opportunities, US academia has virtually established itself as the fulcrum of IR theories production. Meanwhile, the European IR community has maintained a robust dialog, providing a steady stream of theoretical scholarship that has been viewed as complementing or challenging the dominance of its North American counterpart.Footnote 2 Notably absent from this Trans-Atlantic dialog, however, are contributions from the Non-Western world, which have remained largely peripheral to the IR theoretical (IRT) mainstream. Although some have offered formulae, like greater pluralism and dialog, to rectify this deficiency,Footnote 3 it appears that in addition to various institutional impediments,Footnote 4 pedagogical choices may be militating against a truly global IR.

Is the periphery silent because there is an absence of original and meaningful IR theory production, or because there are structural incentives favoring theories from the core? IR's disciplinary histories, especially the recent global intellectual turn, have helpfully grappled with this topic, while contemporary studies of disciplinary trends reveal the nature and extent of the problem by way of adopting frameworks, such as uneven and combined development (UCD).Footnote 5 These histories are instructive in terms of exposing and contextualizing past and ongoing inequalities in world politics as well as the IR discipline. These studies explain that despite homogenizing forces (i.e. ‘combination’) like ideas, technologies, and networks, differences remain in how societies react and adapt, thereby producing significant variations. Thus it is expected, per UCD, that ‘the spread of IR thinking will also be uneven and combined, and the expectation should not be Waltzian uniformity, but Rosenbergian diversity’.Footnote 6 We contend in this paper that the current disciplinary crisis cannot be solved with such a mindset because it overlooks a crucial problem.

Despite our collective and acute awareness of disciplinary inequalities, the IR core has a profound homogenizing impact on the periphery. Rather than Rosenbergian diversity, Waltzian homogeneity is reinforced through disciplinary socialization, a process in which new members of any community of practice, in this case, the academic discipline of IR, become socialized into the community's expected tasks, beliefs, and language through participation that begins on the periphery and moves them gradually toward an assimilated center.Footnote 7 Thus the IR discipline presently displays the dynamics of dependent intellectual development rather than UCD.Footnote 8 Dependency emerged as a major intellectual current in Latin America, was a major contribution to the social sciences, and, despite falling out of fashion, still provides a useful framework with which to challenge dominant forms of theorizing, and thereby help to decenter IR.Footnote 9 Although Dependency made a huge impact, it nevertheless seems not to have had the same impact on the discipline as other popular IR studies published in similar periods. In the spirit of dependency, we argue that this is because the periphery conforms to the core's dominant forms of theorizing through dynamics of disciplinary socialization, since a scholar's success in the periphery and elsewhere depends on their ability to conform to core disciplinary standards, which are sometimes even more brutally self-imposed in the periphery than in core institutions.

As with anything involving production and consumption on a global scale, we need to think about the imperfect and, often, hierarchical forces that determine producer and consumer preferences. In the global economy, scholars in the periphery tend to produce labor-intensive goods for the export business, which are then repurposed into value-added and capital-intensive goods by the core. These goods are then sold to periphery markets as superior products at higher prices. In a similar manner, the academic core creates dominant IR discourses and knowledge, in large part with the help of periphery scholars who tailor their research into a mold deemed acceptable by core journals and institutions – both of which serve to reproduce this modus operandi through the socialization of students. This intellectual dependency has clear implications for efforts to globalize IR, as one may legitimately ask how rising powers can change the global production of IR theories when the graduate training and knowledge production within those rising powers themselves are shaped by mainstream theories. Is it even possible for them to become unshackled from this dependency trap?

In the ongoing discussion on global IR, we, too, position ourselves as advocates of greater pluralism and dialog, while underscoring the need for more homegrown IR theories. By homegrown theorizing we are challenging concepts like post-Western, or non-Western. This is because ‘Western IR’ is dominant in the West as well, and even Western scholarship that falls outside this domain is also in need of emancipation. Homegrown theorizing has no fixed location nor is it in the purview of a specific (non-western) demographic, as anyone, anywhere, can engage in original formulations. Even prominent institutions of the global IR discipline such as the ISA have assumed an almost corporate identity by virtue of its location at the ‘core of the core’Footnote 10 and adopting practices that inadvertently, but inevitably, discriminate against the global rest.Footnote 11 The ISA's advancing of homegrown scholarship, education, and practices is tantamount to efforts supporting local businesses against the rising tide of an IR mega-corporation. For a genuinely global IR we need local and native businesses to thrive through their own efforts and initiatives. This, we argue, requires considerable effort on the part of scholars in the periphery. However, current pedagogical preferences and trends outside of the global core raise doubts about the likelihood of this happening.

Our main purpose, therefore, is to interrogate one component: the dissemination of global IR theory scholarship through the training of IR graduate students around the world. We contend that there can be no genuine homegrown IR theories when the formative experiences of aspiring scholars are informed primarily by mainstream theoretical writings that reinforce the orthodoxies of the IR core. To explore this issue, we undertake an examination of the diffusion of IR theory scholarship as it is taught in graduate-level IR theory courses around the world. We accomplish this by creating a global IR theory syllabus database and coding both demographic and scholarly variables pertaining to IR theory scholarship in assigned materials. What sets our research apart from previous research on IR pedagogy and syllabiFootnote 12 is our variety of data sources (based on 151 syllabi from institutions in 45 different countries), which not only enables a comparative examination of pedagogical trends between the core and the periphery, but also helps us to explicate the staying power of IR's intellectual dependent development worldwide.

Dependency and global IR

Since western intellectual traditions and experiences do not neatly translate into those of the non-West,Footnote 13 it has become commonplace to challenge the disciplinary exclusion of non-Western scholarship by scrutinizing the discipline's Eurocentrism.Footnote 14 Eurocentrism has manifested in IR's fundamental disciplinary discourses since it developed out of racist and Eurocentric perspectives about world politics,Footnote 15 despite its lofty founding myth.Footnote 16 Commonly held contemporary assumptions about the shocking disparities between the so-called intellectual core and the periphery include the predication of all scientific standards on Western experience, as well as the periphery's alleged predilection for consumption rather than production of knowledge.Footnote 17 Second, Eurocentrism figures into the discipline by way of the Anglo-American hegemony's ability to shape normative assumptions about world politics and delineate the research agenda. A survey of the discipline reveals the imperial legacies of the discipline and IR theorizing as a fundamentally US-based intellectual hegemonic exercise,Footnote 18 skewed in favor of the core, albeit less so than some other disciplines.Footnote 19 A final aspect of Eurocentrism is the uneven distribution of disciplinary resources, including institutions and practices of IR publishing, which reflect a Western-bias that gatekeeps non-Western forms of theorizing. Since academic publishing primarily takes place in the West, wherein institutional and professional incentives privilege certain kinds of IRT knowledge,Footnote 20 scholars are exposed to structures and disciplining effects of academic publishing.Footnote 21 This is further aggravated by graduate training.Footnote 22 Quite simply, embedded Eurocentrism presents a formidable obstacle to the development and proliferation of genuine and original homegrown theorizing.

We argue that the most problematic aspect of many efforts to encourage a more globalized IR is assuming that genuine, homegrown theorizing is possible by working within the ‘system’ when ‘your discipline disciplines you’.Footnote 23 In other words, is it possible to theorize the full gamut of complexities of the periphery's social realities through undiscerning imitation of core IR's intellectual tools? The system betrays a similarity to the global economy, and the structure mirrors the dynamics observed in the dependent development literature. Similar to how dependent development theory has been used to explain economic and political dynamics of dependence between the core and the periphery,Footnote 24 we propose the theory's adoption into the study of an academic discipline and thereby also explore an alternative way by which dependency can help to decenter IR.Footnote 25 Dependency theory and its various iterations emerged as a response to modernization theory,Footnote 26 which posited that the formulaic application of certain government policies would enable development. Dependency theorists struck back, arguing that a country's position within the global commodity chain determines its development prospects. The asymmetric relationship of capital- and labor-intensive production between the core and periphery, respectively, creates unfavorable terms of trade (intellectual in our case) that incentivize peripheral elites (compradors) to pursue dependent development. They structure their local economy and institutions in a way that vertically integrates their country into the global commodity chain, thereby encouraging them to realize dependent development through adopting a labor-intensive niche. Both dependent development and our specific application of theory to the development of an academic discipline, underscore the voluntary and parochial nature of the structuring of, in this case, global knowledge production and transfer. The periphery is industrialized; it has capacity, agency, and produces knowledge. The peripheral scholar, however, based on modes of socialization and various institutional incentive structures replicates core-western modes of knowledge production and dissemination.

It is difficult to break from this trap because the global economy incentivizes the periphery to integrate as dependent states, relying on external aid and engaging in labor-intensive production to be utilized in the core for adding value to capital intensive products. Scholars in the periphery may have incentives to ‘mimic’Footnote 27 their Western counterparts and become ‘native informants’.Footnote 28 who ultimately engender the dominance of mainstream theories by supplementing them with additional case studies and data points; labor-intensive work that benefits the core. This also includes the importation of critiques from core paradigms, since genuinely innovative and non-Western perspectives are rarely produced or, more likely, rarely appear in major Western outlets. Again, the specific mode of entry into the market is the reason. The global IR system structures the discipline through publication standards and other disciplinary activities, like major conferences, not unlike how borrowing money from the IMF is contingent on structural adjustment. To stay relevant in the IR system, scholars in the periphery must fulfill the expectations of editors and reviewers in top Western journals. This, in turn, leads IR theory practitioners in the periphery to act as conduits of ‘Western IR Theory’ by gatekeeping either the production of IR theory knowledge in the periphery or the training of aspiring IR theory scholars, much in the same way that internationalist comprador elites are incentivized to advocate the interests of international capital. As we demonstrate below through an examination of IR theory course syllabi, these dynamics are present in IR pedagogy too, which begs the question of what kind of pluralism we can expect to find in a discipline in which aspiring scholars in the non-West are trained with the same materials as their core counterparts. How can they develop unique insights about IR and contribute to a genuinely global IR when most of what they imbibe is mainstream IR theory?

Studying a discipline through IR theory syllabi

IR theory in many ways forms the core of the IR discipline. Other disciplines, like Political Science, may examine IR topics and develop frameworks and concepts, but IR theories are wholly unique to the IR discipline and set the disciplinary agenda. For example, as Wæver mentions, Waltz's Theory of International Politics (or ‘theory of theory’) has arguably become a yardstick against which all other IR theory research is measured.Footnote 29 One cannot help but reflect on the agenda-setting qualities of paradigmatic research and the star power of disciplinary luminaries. Avey and Desch, for instance, show that US-based IR scholars and policymakers alike have nominated prominent IR theorists as being ‘the most influential’ IR scholarsFootnote 30 while finding that scholars in the periphery attach as much importance to paradigmatic research (if not more in the case of approaches like realism) as their core counterparts.Footnote 31 Meanwhile, IR theory continues to be the discipline's main driving engine, enjoys a top-dog status in the discipline, and may be considered the most prestigious form of scholarship – although admittedly there appears to be a decline in the publication of paradigmatic research in favor of mid-range theorizing.Footnote 32

In entering this conversation on IR theory pedagogy, we chose to focus on graduate-level syllabi around the world. Extant syllabi-centric studies have sought to utilize reading lists, often in conjunction with comprehensive examination lists and other journal-based bibliometric analyses.Footnote 33 Each piece of scholarship assigned for students to read is an indirect indicator of disciplinary socialization and dominant patterns of IR theory diffusion since institutional directives and instructors' prerogatives help to shape curricula. Granted, inferring potential pathways of graduate-student socialization from an instructor-preference based analysis are difficult to consistently measure on a large scale since many idiosyncrasies can affect the process. Research requirements and students' diverse research interests may direct them to readings beyond those that are assigned.Footnote 34 Moreover, students' mileage from their coursework may vary based on their prior educational and personal contexts,Footnote 35 their second language (i.e. English) capabilities,Footnote 36 and even the very academic habitus which stifles some ideas in favor of others. Graduate classrooms will naturally vary according to institutional context, with some imposing a more hierarchical and assimilatory structure and others enabling a more horizontal and plural intellectual environment conducive to critical thinking. Similarly, local academic cultures and institutional practices may reinforce to varying degrees modes of socialization promoting deference to the instructor and unquestioning adaptation of material.Footnote 37

We nevertheless contend that syllabi grant us an indirect lens with which to understand the dominant patterns of instructors' evaluations of the IR discipline's canon and state of the art. There are two potential pathways to linking syllabi with socialization. First, with so many degrees minted in core institutions, instructors might inadvertently be acting as gatekeepers helping to maintain dominant patterns of thought and disciplinary biases by highlighting some research over others. Because schools and instructors in the periphery are likely to accept the assimilatory pressures of the discipline and privilege core scholarship, socialization in periphery institutions may also result in homogeneity rather than diversity. Although it may not appear prima facie that instructors' assigned readings necessarily engender intellectual conditioning, the very practice of crafting a curriculum or syllabus by necessity distinguishes mainstream works and creates intellectual boundaries. Even if one were to operate from the via negativa and select studies with the expectation of repudiating them, one is still suggesting which arguments are most attention-worthy. To repeat an earlier point, if WaltzFootnote 38 has become a yardstick in many syllabi, it is only so because of instructors' choices to deem and select his works as the best, or worst, version of an argument. If pedagogical preferences in core and periphery institutions lean toward similar goals, even if to criticize mainstream approaches, diversity may still be stifled.

Second, we can think of syllabi as being affected by publication trends and vice versa. An instructor's emphasis on specific types of publications, methods, and journals (or academic publishers) may be instructive for graduate students about which journals and publishers they should follow, what types of research they ought to conduct, and where they should aspire to publish.Footnote 39 As ombudsman between graduate students and the published discipline, instructors are both conscious and unwitting conduits of socialization by privileging some journals and publishers over others, thus interpreting what are considered popular publication trends.

Most syllabus studies have been relatively narrow in scope because of the difficulties involved in collecting data. Our project is unique both quantitatively and qualitatively. Quantitatively, the data collection and coding process was a multi-year undertaking (2018–2020), focusing on a hitherto unmatched number of syllabi. We systematically compiled graduate-level IR theory course syllabi from universities around the world, from core countries in North America and Europe to institutions in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Oceania – 151 syllabi total. Our efforts, we hope, will allow us to build on preexisting investigations of IR syllabi that examine USA,Footnote 40 Anglo-European,Footnote 41 and African syllabi,Footnote 42 allowing for the first time an examination of both Western and non-Western IR theory graduate syllabi comparatively.

Research design

The purpose of this study is to provide a detailed account of the development and propagation of the IR discipline by examining graduate-level IR theory syllabi around the world. Our goal is to examine how, and by whom, IR knowledge is produced and disseminated globally. We provide a ‘CT Scan view’ to trace patterns in which certain ideas have been imported/exported to divine dominant patterns of distribution. The study aims to reveal, therefore, whether there is an underlying unfavorable intellectual ‘terms of trade’ between the core and periphery, or if instead the creation of a dominant pattern of scholarship and pedagogy is an organic process in which the periphery, rather than being a hapless victim of structural exclusion, also has agency. We believe that until scholars undertake a detailed analysis of IR theory production, pedagogy, and proliferation, a definitive diagnosis of the inclusivity of the discipline will elude disciplinary debates. By way of addressing this lacuna, our study rises to Acharya's challenge to positively expand the global IR scholarship agenda.Footnote 43

Simply, we sought to assess if the syllabi in our sample show notable regional variations akin to the UCD model or if we would find more of the homogeneity associated with dependent development. We advance two propositions about the state of IR theory assigned as graduate readings. First, ‘Similarity’. If we find similarities in the types of assigned readings in core and periphery institutions and the ratios among them, it will point to the homogenizing tendency of the discipline. We attempt to test the specific mechanism responsible for the patterns that emerge. Although we argue that where one is educated may play a significant role, hence our decision to attempt a CAT scan of the discipline via syllabi analysis, it is also likely that the discipline has become so homogenizing that other considerations like institutional preferences or popularity play a more important role. Simply, the logic of the market promotes emulation. Our second consideration is ‘replication’. If we find that instructors in the periphery are likelier than those in core institutions to assign critical and reflexive IR theory developed in the core, it will lend support to the dependent development argument because it exhibits a tendency to vertically connect with the intellectual marketplace from a dependent position rather than developing domestic capability for horizontal integration. A corollary to this would be that the dependent development perspective will garner further support if core syllabi are more likely to assign homegrown theorizing than their periphery counterparts. This would show that the core is indeed a kind of intellectual engine that is moving forward while courses in the periphery squelch homegrown research.

To map the diffusion of IR theory we seek to understand what kinds of studies dominate syllabi. In this respect, we aim to further advance the TRIP surveyFootnote 44 by way of a tripartite IR theory scholarship coding scheme, assessment of instructors' demographic data, and an investigation of local language studies.

An alternative typology of IR scholarship

Crafting a typology of IR theory scholarship is inherently difficult. Regardless of one's categories, the nuances of any study can render attempts at classification an arbitrary exercise. Theory in particular is a contentious subject for the IR discipline, with multiple possible meanings.Footnote 45 For our purposes, we define ‘theory’ very broadly, as ‘a contribution to a body of literature in (the IR) discipline that illuminates some aspect of the (social) world’. A key distinction then, concerns the primary intention of the contribution.Footnote 46 IR theory research has also been visualized as being divided among major schools of thoughtFootnote 47 and, similarly, based on the extent to which it is paradigmatic.Footnote 48 This conventional focus on explicit theoretical/paradigmatic identities is problematic, however, because a theoretical-identity-based division can ignore variations within paradigms, or the extent to which a study is indeed advancing paradigmatic axioms, or rebuking them, even from the same assumptions. In other words, whether a contribution presents a challenge to the extant wisdom of the discipline by offering critical perspectives, as opposed to a prescriptive, or problem-solving, one,Footnote 49 is of consequence. Given the contested nature of IR as a scientific enterprise, this study advances a typology of IR scholarship that distills insights from various prior studiesFootnote 50 by categorizing IR theory scholarship along two major axes (see Table 1).

Table 1. 2 × 2 arrangement of IR theory scholarship

First, to what extent does a study place itself within a specific IR-paradigmatic grand theoretical tradition? Although IR theories do share common suppositions concerning the social world, their axiomatic differences militate against a unitary conception of the discipline that makes it necessary to address its paradigmatic qualities. According to Kuhn (1963), disciplines are guided by foundational assumptions that establish their boundaries and scientific standards, thereby delineating a space in which normal science, or ‘scientific progress’ can take place. IR has eluded the formation of an all-encompassing paradigm and several ‘relatively-similar’ schools of thought (or grand paradigms) have established themselves as ‘mainstream’ grand-theoretical paradigms that form the core of the discipline.

For our purposes, paradigmatic research refers to theoretical research that identifies as having explicitly placed itself in a broader research program, or family of studies that build on similar foundational assumptions about the social world. It is this type of research that has been found to appear most prominently in IR syllabi in North America.Footnote 51 In contrast, non-paradigmatic research eschews a grand-theoretical identityFootnote 52 and instead explores core IR topics like alliance formation, war initiation, cooperation, among other things, by using tools more broadly available to the social sciences. For example, a bulk of rational choice and other behavioralist research, and many mid-range theories, especially those that do not identify with a specific IR paradigm, would fit here. Since they borrow ideas, concepts, and methods from related disciplines like Political Science and Economics to address IR phenomena, non-paradigmatic studies do not formally contribute to core IRT paradigms.

Second, we ask how ‘revolutionary’ or ‘conservative’ oriented a study is based on whether it is advancing knowledge that reinforces the same axioms of a body of research, or seeking to critique it. All scientific research aspires to provide a better answer than its alternatives and thus is, by design, revisionist to some extent. However, there is a primary difference between generating new hypotheses and data for a theoretical premise by adding to the ‘n’ of a research program, and casting a reflexive and critical gaze. This second axis is, therefore, important because it is an indication of a discipline's reflexivity and inclusivity. Conservative in this sense refers to the replication of the fundamental assumptions as well as the methodological and epistemological conventions of paradigms, understanding that such scholarship may introduce incremental progress (however defined) to a particular way of knowing. For our purposes, foundational ontologies, universal conceptions of science, axioms such as state-centrism, a western geocultural reference point, and an emphasis on problem-solving theory vs. critical theory are the most important indicators. Revolutionary, therefore, refers to the expansion of the purpose and concept of theory. This type of research interrogates the fundamental assumptions of paradigms, engages in introspection, while seeking also to expand the traditional subject matter and boundaries of the discipline; in this case beyond state-centrism and Eurocentrism.

Based on these axes, we can thus conjecture four types of IR theory research: imperial theorizing, ancillary, reformist, and homegrown.Footnote 53 We have chosen ‘imperial theorizing’ as the deliberately provocative designation for mainstream, often US-based IR theory research for two reasons. First, this type of research perpetuates axioms originating in the Western IR canon.Footnote 54 These include state-centrism, a universal conception of science, and a tendency to produce problem-solving theories.Footnote 55 Second, many of these studies either concern American foreign policy, the Western and great powers' experiences, or simply take core theoretical research and replicate it in the Global South. Aside from their state-centrism, all these studies display one or more other features that qualify them in this category. From classical realism's ahistoric and timeless wisdomFootnote 56 to structural realism's starting point as a theory of theory rooted in a narrow understanding of science,Footnote 57 to the clear US-centric political agendas of complex interdependence and liberalism(s) as validations of American hegemony,Footnote 58 imperial theorizing is a distinct and common category. There are, however, significant within-paradigm variations, as some constructivist and English School studies can be considered as imperial research. For instance, constructivism has conventional and critical strands. The constructivists' challenge is no doubt a revolutionary response to the Realists' dominant discourses, yet most conventional constructivist perspectives ultimately offer explanatory and problem-solving theories, and operate, for methodological reasons, with foundational assumptions contrary to their critical counterparts.Footnote 59 The English School, meanwhile, famously exists as a tripartite framework, with a more-conventional and statist pluralist wingFootnote 60 contrasted with more solidarist and critical perspectives.

Ancillary scholarship, so-called because it aids grand theory development, eschews grand theoretical identities or arguments. Instead, this kind of research primarily addresses subjects in the disciplinary domain of IR but does so by borrowing ideas, concepts, and methods in an ad hoc fashion from other disciplines like Economics or Political Science.Footnote 61 Many works on bargaining, alliances, war initiation, and deterrence, for example fit into this category, unless otherwise stated by the text, because their core components are potentially compatible with a wide range of grand theories.Footnote 62 We also consider manuals on theory-building and research as being part of ancillary scholarship. Readings on methodology and research design, philosophy of science, and social scientific debates more generally are ancillary IR theory scholarship precisely because they aid theory development.Footnote 63 For these reasons, we argue that the high prevalence of imperial and ancillary research in IR theory syllabi would suggest that the dynamic of similarity is not only significant, especially in local language, but also evidence the assimilatory tendencies of the discipline.

We posit, next, a separate category of critical studies originating primarily from Western intellectual traditions as well as studies in other disciplines. ‘Reformist’ theorizing's research agenda extends beyond the IR discipline, tracing a distinct IRT pedigree but one that ultimately seeks to transgress and expand the traditional boundaries of imperial scholarship. Reformist theorizing not only borrows from other disciplines but is arguably an extension of other academic disciplines and intellectual traditions into IR. It simultaneously embraces a paradigmatic identity but also one that ultimately transcends disciplinary boundaries, often calling into question the ontological and epistemological assumptions of ‘imperial’ IR theory scholarship.Footnote 64 Reformist scholarship critiques mainstream IR, denaturalizes the state, draws attention to levels and processes traditionally excluded from mainstream IR, such as class, gender, and post-colonial relations.Footnote 65 Assessing the relative prevalence of reformist scholarship is important because this type of research is inspired by Western IR and related disciplines to challenge mainstream theorizing.

Our final category is homegrown IR theory. Homegrown scholarship is defined by the distinctiveness of geocultural reference point.Footnote 66 Homegrown scholarship is revisionist in that it advocates pluralism and syncretism, seeking to extend the boundaries of mainstream IR by introducing alternative cases, especially from the global periphery; developing theories distinct from mainstream paradigms; and challenging conventional IR theory scholarship beyond arguments derived from Western IR theory paradigms. Homegrown theorizing is distinct because it does not formally situate itself among existing schools of IR thought originating from the global core. It is non-paradigmatic because it seeks disassociation from the lineage of imperial scholarship that forms the discipline's mainstream critiques originating from the Global North. To illustrate, the dependency framework for our analysis can trace its lineage to Marxist theories on imperialism, but its advocates have carved out an independent identity as an approach for and by the periphery. That said, homegrown research can be conducted by anyone so long as the research uses ideas and thinkers originating outside of the Western tradition, but more importantly seeks to provide alternatives to mainstream theories.Footnote 67 It is worth underscoring that homegrown theorizing moves beyond the metadisciplinary task of critiquing mainstream approaches per se and provides theoretical and empirical novelties. Homegrown theorizing is the hallmark of pluralism and the heterogeneity we would expect from a truly global discipline. For instance, Cox's efforts to incorporate Ibn-Khaldun's political theory to the study of hegemony,Footnote 68 Escudé's writings on the anthropomorphic fallacy,Footnote 69 and homegrown responses to mainstream theories that go beyond mere criticism to generating novelties such as Ayoob's subaltern realism and Escudé's realismo periferico.Footnote 70

Inevitably, a few readings defy clear-cut categorization because they are unmistakably from other disciplines or are not scholarly in nature, and are simply designated as ‘other’ (Table 2).

Table 2. Sample works

Demographic data

Another component of our study is mapping the demographic breakdown of instructors who teach IR theory, a key variable in helping to assess the nature of core-periphery dialog in IR theory scholarship and pedagogy. To this end, we extract data about the instructors' alma maters. We contend that one's alma mater is a more important metric than one's national affiliation because assimilation, by way of disciplinary socialization, happens at university. Part of the reason that academics from the periphery may become ‘academic compradors’ could be attributed to their formative experiences and induction into IR theory production as graduate students in Western institutions. It was imperative, therefore, to consider where scholars earned their degrees and to explore whether this has some relation to their preferences when assigning readings.

By examining the instructors' (under)graduate alma mater(s), this study is able to offer insights into that presumption, including comparative data on whether there are differences according to particular schools or between undergraduate and graduate studies. A majority of IR scholarship originates in North America and Europe, where many IR PhDs are also minted. No matter how competent, capable, and prolific these instructors may be, their induction and socialization into the IR discipline through the prism of core institutions and expectations may impede their effective participation in initiatives to globalize IR. We conjecture that scholars educated in Western institutions may likely prioritize imperial and ancillary scholarship in their teaching. Moreover, if we find that scholars educated in non-core institutions also elicit a similar pattern, then we can more confidently argue that disciplinary socialization and the dynamics of IR indeed resemble dependent development.

Disciplinary language

A final issue is the language of IR theory courses. Given the epithet ‘International’, there seems to be a prevailing tendency among academic programs around the world to choose English as the language of instruction. There are several reasons for this, ranging from successive periods of Anglo-American hegemony and globalization, which made English the global political and cultural lingua franca; to the fact that major venues of publication are located in the Anglophone world. Without downplaying the immanence of the English language, it is nevertheless peculiar that many IR departments in non-English-speaking countries prefer to teach their classes in English or to assign IR theory scholarship in English even when locally produced texts are available. This is no trivial matter because choices like the language of instruction and the use of local languages and scholarly works, may influence the research interests and sensibilities of aspiring academics and socialize them into academia in a way that reinforces Anglo-American hegemony.Footnote 71 In fact, English-language-based terms and concepts arrive as carriers of IR theory knowledge, the first pills of assimilation, or homogenization, standardizing the disciplinary language and delineating the boundaries of thought. Moreover, although perspectives vary, some research in linguistics and cognitive science has shown that one's imagination is less vivid when using a foreign language.Footnote 72 This may help explain why imitation of theories, rather than original theory building, may be more common among scholars in the periphery.

In other words, so long as local languages are eschewed in the classroom, even as assigned readings, assimilation may be likelier than genuine diversification and enrichment. However, it is also likely that under dependent development, local-language studies might reproduce by way of translation the same mainstream IR theories, which again would lend support to the dependent development argument. We, therefore, formally inquire into whether instructors assign readings in any other languages, including their institution's local language(s), in their courses and whether there are differences in terms of the types of scholarship assigned to students.

Data selection

Our focus on graduate syllabi is important for several reasons. Apart from providing a better basis to compare specialized training, graduate-level IR theory courses are fewer in number compared to undergraduate ones, making this a better sample of the total available data. Moreover, graduate-level courses are more significant in the training of IR scholars and instructors. Barring some exceptions, graduate school is where most students are inducted into the discipline; identifying students who want to specialize in an IR topic, and possibly pursue academia as a vocation. Although undergrads are often exposed to metatheoretical debates about IR and the philosophy of science, this pales in comparison with the graduate school experience. Finally, graduate school is the transitional phase when consumers of knowledge are socialized into becoming producers too, which is how they encounter the hierarchies of knowledge in the first place.

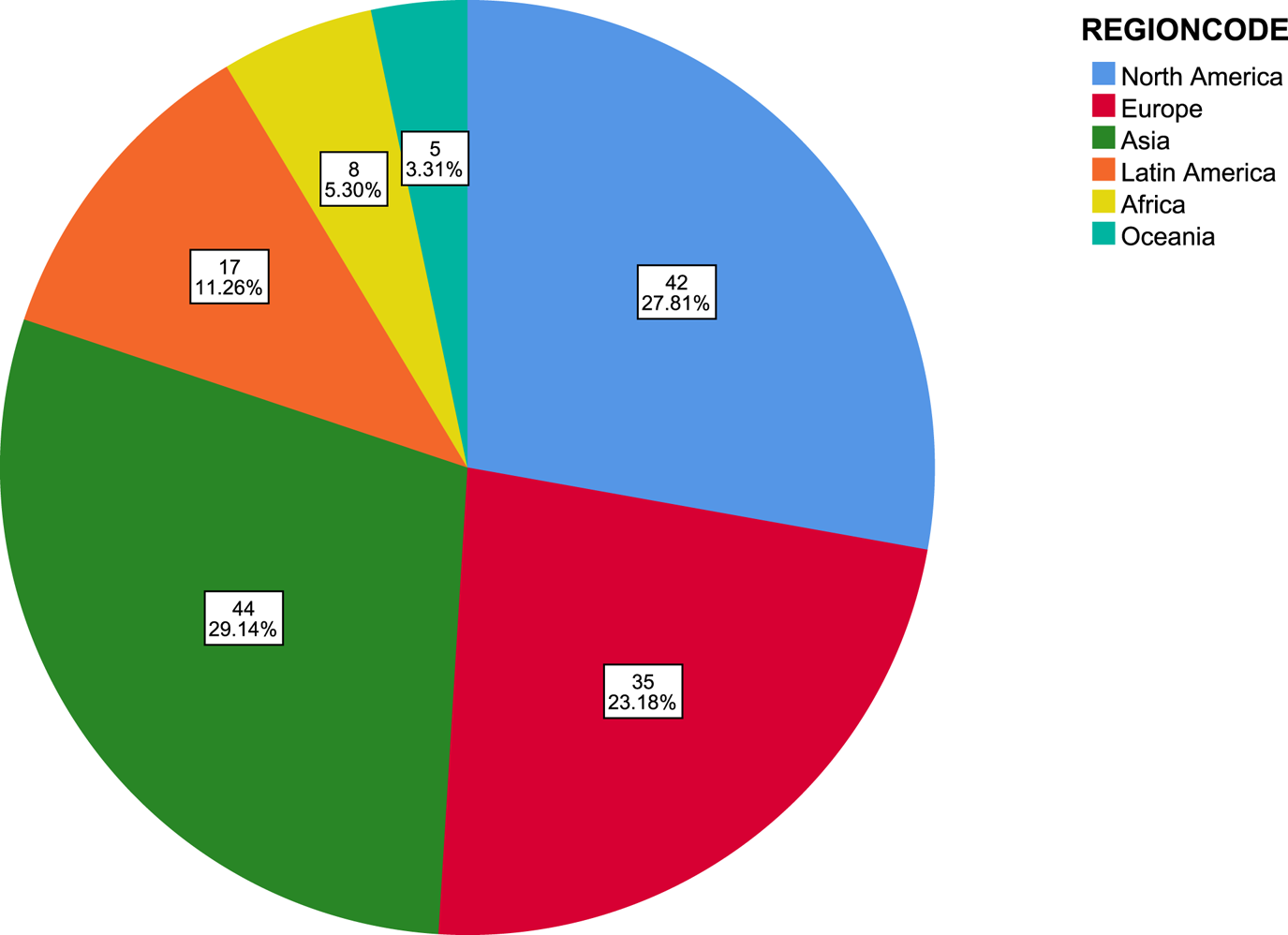

Our selection criteria for the syllabi were based on two considerations. First, we went through the QS World University Rankings (2018) and made a list of top graduate IR programs for each continental region. Based on the curricula information on the school's websites, we searched the internet for each program's graduate-level IR theory course (or whatever designation was used by the institution, such as ‘Contemporary IR Theory’), and compiled all syllabi dated from courses taught between 2010 and 2019. Given the enormous discrepancies in the reading requirements of each syllabus (some did not mention any readings and others mentioned only a textbook or two), we did not code syllabi that mentioned fewer than seven readings. Finally, the availability of syllabi greatly influenced our sample. Like ColganFootnote 73 we were largely limited to syllabi available through internet searches, although we were able to obtain several additional syllabi from instructors who responded positively to an email inquiry (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Geographic distribution of syllabi (N = 151).

Coding process

Following our quadripartite typology we coded each piece of IR theory scholarship presented as required readings in the 151 syllabi, resulting in 5064 pieces in total. For each one we read the abstract, introduction, and conclusion sections, as well as introduction chapters, forewords, acknowledgments, and prefaces in the case of books, to determine which category it fell under. In cases of uncertainty, we applied the following additional procedures until we reached a consensus. For article and book-chapter length readings, the original coder would read the rest of the text to reach a verdict, while for scholarly books the coder would read the primary theoretical chapters to reach a verdict. Next, a second coder would follow the same procedure. If both coders independently reached the same verdict, no further steps were taken. If consensus was still not possible, a third coder would follow the same procedure and all three would discuss their reasoning until deciding on a final verdict.

When coding imperial scholarship, we often relied on their identifying designations. Especially in the case of seminal/foundational ‘imperial’ texts, many were pre-determined by others, rather than through our coding process. For instance, it would not have been immediately obvious that The Anarchical Society Footnote 74 was a contribution to the ‘English School’ without knowledge of succeeding developments in the literature since the only mention within Anarchical Society to the English or British School of IR is found in the forewords of recent editions. Similarly, in the Theory of International Politics,Footnote 75 which is the seminal text of Structural Realism, the word ‘Realism’ is not mentioned in the book. For ancillary scholarship, we paid attention to whether the texts mentioned specific paradigmatic affiliations, the origins of the concepts and hypotheses being employed, and whether these originate from other social sciences. A further consideration relates to pedagogical matters, whether these texts discussed matters of theory-building, research design and methodology, or pedagogy. Coding reformist scholarship relied foremost on explicit references to critical research traditions rooted in other disciplines such as critical studies, gender-related research, and post-colonial research, all of which are distinct traditions found in other social sciences and humanities. We further noted if a given study engaged in critical and normative theorizing. Finally, for coding homegrown scholarship, we looked to see if a study positioned itself as part of a grand theoretical paradigm or school of IR thought. We coded studies that explicitly situated themselves as doing non/post-Western, post-colonial, homegrown, or local theorizing. Even when not explicit, we examined if a given study used thinkers from the non-Western world to develop IR theory, attempted to develop a theory with original concepts/data emanating from the non-West, or sought to advance IR theory using literature and concepts from completely non-Western works. Everything, including non-scholarly works or philosophical texts from the Western world, that did not fit any of these categories, were simply coded as other.

Findings and discussion

Generally, our results show that IR theory courses favor imperial scholarship or studies that concern mainstream IR theories as the most popular type of assigned reading, followed by reformist, other, and finally homegrown studies (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. IR theory scholarship from our sample.

Although the sample sizes were small for some regions, for example, Africa and Oceania, we nevertheless undertook a detailed analysis of the syllabi based on their regional distribution (Figure 3). The findings show that, across all regions, IR theory instructors seem to favor assigning to their graduate students, in declining order of preference, imperial and ancillary IR theory, reformist research, non-IR works, and homegrown IR theory. Imperial and ancillary scholarship constitutes the bulk of assigned readings, indicating a preference for assigned readings about specific IR grand theories and schools. This is consistent with the observation from the TRIP survey that paradigmatic studies feature most prominently in North American syllabi, as well as recent accounts about the rising prominence of non-paradigmatic and mid-range theorizing.Footnote 76

Fig. 3. Percentage distribution of each type of IR theory scholarship (by region).

There are, however, some notable variations within both the core and the periphery (see Figure 4 for averages), when these terms are defined in terms of political and economic North-South. Concerning imperial scholarship in the Global North, differences between North American, European, and Oceanian institutions were minimal (38.75, 39.81, and 31.76%, respectively). In the periphery, meanwhile, the average percentage of imperial scholarship was at even higher levels than in the core, comprising 45.90% of assigned material in African syllabi, 47.85% in Asian, and in Latin American 38.41%. Overall, syllabi in Africa, Asia, and Oceania seem to deviate more than other regions from the global average mean of 41.7%, evidencing cross-regional similarity and, therefore, homogenizing tendencies in IR theory pedagogy. The tendency to assign ancillary scholarship, meanwhile, shows relatively little variation from the global average of 26.4%, although syllabi from Oceania appear as a significant outlier since they far exceed the average at 52.65%, although this may be attributable to the small sample size.

Fig. 4. PhD region (‘political’ core vs. periphery) and scholarship assignment.

Meanwhile, there is much greater variation in the distribution of reformist and homegrown scholarship. Although both types are generally low globally (20.3 and 3.5%, respectively), their relative exclusion from North American syllabi (15.82 and 2.93%, respectively) is indicative of a tendency in the core of the core to ignore alternative approaches rooted in critical traditions as well as homegrown perspectives. This percentage is low especially when we consider that in our sample, North American institutions tend to assign more readings overall on average (51) than the global average (24). Interestingly, reformist scholarship is more prominent in Asian (20%), European (28%), and Latin American (24%) syllabi. Homegrown theorizing, however, is uncommon everywhere, with a global average of 3%; exceeded only slightly in European syllabi (5%).

Although we cannot box each kind of scholarship to a geospatial location since this could run the risk of presenting an overly skewed and counterproductive picture of the discipline, we can nevertheless argue that some research traditions and publication types are more likely to appear in some places than others. If there are similarities across multiple regions, then this would suggest evidence of disciplinary globalization. To the extent that globalization refers to the movement of ideas and volume of trade, the syllabi showcase a kind of globalization based on the preeminence of North America mainstream theorizing, since imperial scholarship, much of which originates from North America, is globally dominant. It is perhaps not surprising that reformist literature is prevalent in Europe since much of that scholarship can be traced to European universities. Reformist literature is less prevalent in the North American core but seems to be well-represented in other regions. Homegrown theorizing, meanwhile, struggles to find sufficient representation anywhere, which is something we need to acknowledge before reflecting on how to reform IR in the core to make it more global and pluralistic.

Interestingly, when we reexamine global trends by dividing the regions into broadly conceived categories of core (North America, Europe, Oceania, and Japan) and periphery (Africa, Asia, and Latin America), Reformist scholarship's prevalence in the periphery while not in North America can be attributed to intellectual dependence, and corroborates earlier findings about US parochialism.Footnote 77 We can infer that courses in the global south recognize the need to provide alternative frameworks to US-based paradigmatic studies and therefore incorporate critical perspectives. In conjunction with the general lack of homegrown theorizing, however, this endeavor is largely enabled by predominantly Western-inspired and paradigmatic critiques rather than homegrown ones, which is consistent with replication. It is also possible that peripheral scholars who are socialized by core institutions and disciplined by Western publishers’

As for the ‘other’ category, North American (12.12%) syllabi are more likely than those in other regions to assign these, including studies from broader disciplines, philosophical or ‘pre-theoretical’ texts, or journalistic/op-ed texts. Although the overall regional figures are closer to the global average of 8%, European and Oceanian syllabi are nevertheless likelier than their periphery counterparts to assign ‘other’ readings. It is difficult to speculate on the reason for this, but it may be related to the average workload in North American syllabi and those from the Anglosphere in general, which tend to have longer reading requirements.

Despite underscoring the importance of homegrown theorizing, very few IR courses bother to assign this type of research. European syllabi, and instructors with a European education who teach in English, are generally the group most likely to assign homegrown scholarship. But, there can be no illusions about the dependent nature of the discipline. American-based, mainstream theories are dominant regardless of region, the language of instruction, and instructor background.

Education and scholarship preferences

Although the trends in assigned readings suggest a strong bias toward mainstream scholarship, we sought to investigate to what extent these trends are linked to instructors' education, or simply to the homogenizing and centripetal forces of the discipline. For each syllabus, we gathered publicly available information about the instructors' Department/location (at the time of teaching) and Alma Mater (BA, MA, and PhD institutions). As shown in Figure 5, regardless of their current affiliation, 134 of the 151 instructors earned their degrees from North American, European, and Oceanian institutions. From a purely descriptive point of view, the high number of PhDs from not just the core but the Anglosphere specifically, is interesting as it serves as a reminder of how many of the people tasked with pluralizing and emancipating periphery scholarship have been socialized into the global IR system through core institutions and expectations; and may be more likely, therefore, to adapt pedagogical preferences that reflect that training. This is true even though half of our sample contained syllabi from other regions (i.e. instructors employed outside of the global core).

Fig. 5. Distribution of degrees by region.

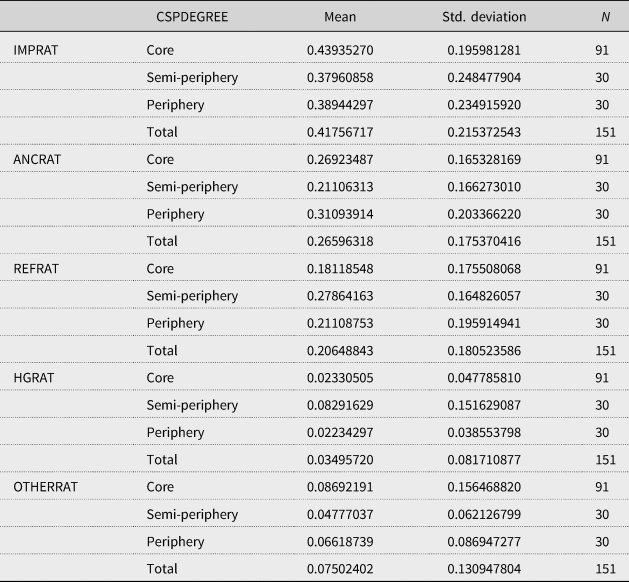

To make sense of these data, we sought to run statistical tests ordering the data based on a different conceptualization of core-periphery. As Turton points out,Footnote 78 our conceived notions of core and periphery fail to highlight many of the intellectual flows, hierarchies, and other nuances that exist within these categories. Taking inspiration from the divisions within the ‘core’,Footnote 79 or the idea of a core of the core, and peripheral states with intellectual cores, we interpreted the core as North America and the UK; the rest of Europe and key countries with intellectual cores like Brazil, China, Japan, and South Korea, as semi-periphery; and the rest as periphery (see Figure 6).

Fig. 6. Comparison of types of scholarship: core vs. semi-periphery vs. periphery.

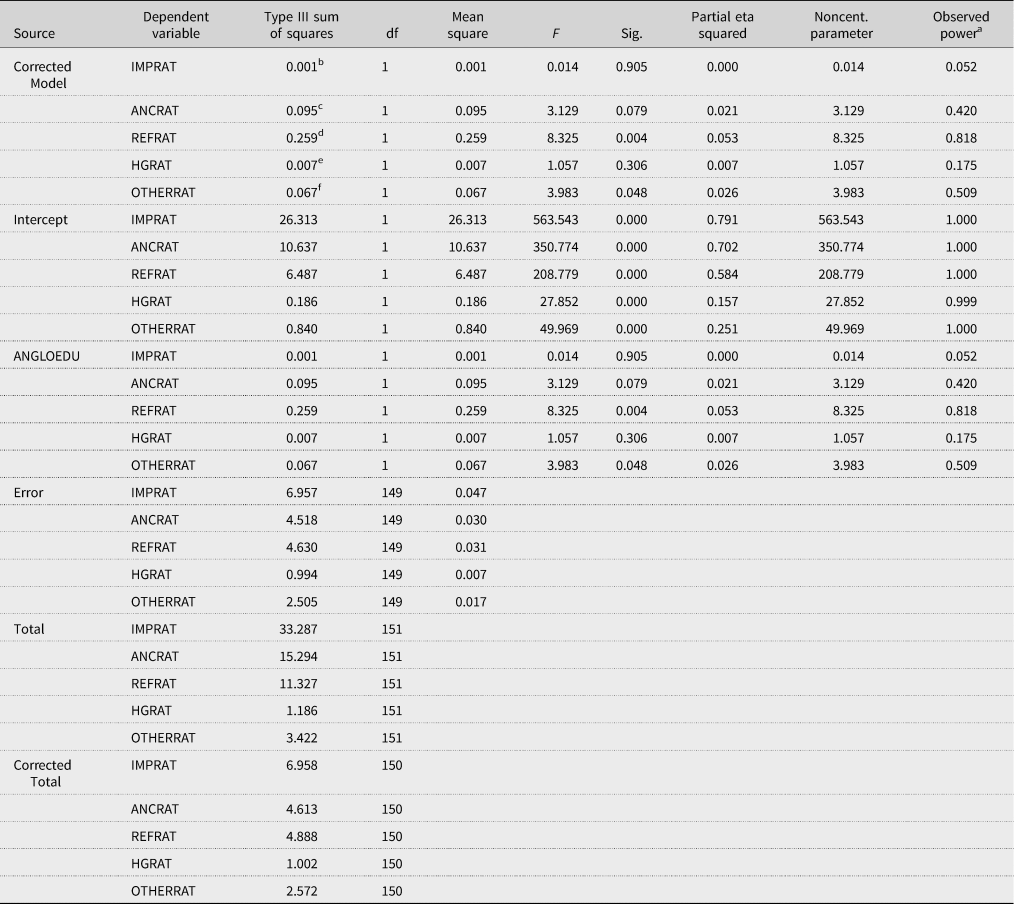

We then devised a multivariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) test to see how our categoric factor interacted with each scholarship type across our syllabi. Although our data did not fulfill the normality assumption due to discrepancies in the scholar preferences, we still conducted a parametric test because each regional group in our model contained at least 30 cases, rendering our model robust to violations of normality. We discounted our findings on homegrown and other scholarship, the former being statistically significant, due to extreme skew and kurtosis (see the Appendix) beyond the acceptable parameters. This was likely because most syllabi in our sample simply did not have any homegrown and other scholarship, and the mean values were thus based on outliers' values. This was not the case for imperial, ancillary, and reformist scholarship, so for these we tested our model based on where instructors earned their PhDs.Footnote 80

There was a statistically significant difference between core, semi-periphery, and periphery when considered jointly on the dependent variables, Roy's largest root = 0.054, F(1, 148) = 2.33, P = 0.002, partial η 2 = 0.109. A separate ANOVA was conducted for each dependent variable (alpha level 0.05). There was a significant difference in terms of where instructors earned their PhDs based on their tendency to assign reformist scholarship, F(2, 148) = 3.406, P = 0.36, partial η 2 = 0.044, with core, semi-periphery, and periphery educated instructors' mean ratio of reformist scholarship at M = 0.181, M = 0.279, and M = 0.211, respectively. Imperial and ancillary scholarship, meanwhile, did not yield any statistically significant results. Overall, PhD education had a statistically significant relationship with instructors' tendency to assign reformist scholarship, explaining 4.4% of the variance, and suggesting that instructors with PhDs from semi-periphery, that is, European universities apart from the UK, as well as a selection of other countries from the periphery with intellectual cores, are far more likely to adopt reformist scholarship.

To assess potential differences in trends with respect to language, we investigated differences between courses taught by instructors who received their doctoral degrees in the Anglosphere (i.e. Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, UK, and USA) compared to the rest of our sample (N = 77 and 74, respectively). We aimed to see if there were discernible tendencies between institutions where the local language is English compared to institutions that adopt English as a foreign language as well as courses taught in other local languages. There was a statistically significant difference between the three groups when considered jointly on the dependent variables, Roy's largest root = 0.074, F(4, 146) = 2.703, P = 0.033, partial η 2 = 0.069. A separate ANOVA was conducted for each dependent variable (alpha level 0.05), revealing a significant difference in terms of English language based on their tendency to assign reformist scholarship, F(1, 149) = 8.325, P = 0.004, partial η 2 = 0.053, with syllabi from the Anglosphere, and the rest of the world featuring mean ratios of reformist scholarship at M = 0.166 and M = 0.249, respectively. However, we note that the overall results resemble our examination of syllabi based on PhD regions since dividing the world based on language, that is, where English is the native language, is akin to the core-periphery divide. The over-representation of North American institutions in the former population reduced the overall mean of reformist scholarship compared to the non-Anglosphere (Figure 7).

Fig. 7. PhD region: Anglosphere vs. the rest of the world.

The data leave us in a place to interpret some of our earlier thoughts. First, the lack of a statistically significant relationship between graduate education and scholarship preferences with respect to imperial and ancillary relationship suggests that these types of readings are overall dominant and pervasive. In this respect, the disciplinary practice of using mainstream works, at the expense of homegrown scholarship, is so entrenched that regardless of one's educational background, syllabi around the world will generally resemble one another due to the homogenizing effects of the discipline. Imperial scholarship dominates regardless of the region; variances in education backgrounds do not seem to account for this; and in view of Figure 4 from earlier, there is a noticeable difference between core and periphery (again, taking a conventional political global north-south perspective), with the latter being even more susceptible to assigning this type of research. The high ratio of reformist scholarship assigned by those who studied in the peripheries with intellectual cores is an interesting finding. This group appears to be the most enthusiastic in terms of assigning studies that critique the core mainstream, but this is again primarily achieved through studies developing around paradigmatic research. Homegrown research is, overall, an afterthought.

Although we are confident about these modest findings, our substantial data remain lopsided due to insufficient data from regions such as Africa, particularly outside the MENA region and South Africa, as well as Oceania. Even when syllabi are available, they tend to be uneven in length and detail. Finally, the fact that homegrown and other scholarship either figure rarely into syllabi has impeded us from making reliable inferences with a parametric test.

Concluding thoughts: toward a symmetric interdependent theory of global IR

Our data provide evidence of a dependent relationship in the production and dissemination of IR knowledge. The question remains although of how best to proceed from here. Drawing further on the analogy of IR knowledge as an international commodity, developmental global economic theory suggests three routes may be pursued by dependent actors in such a relationship: full liberalization; revolution; and strategic trade policy.

In traditional economic dependency, a dependent country may opt to open up its economy to full trade liberalization, but because local technologies and know-how are limited, raw materials are prioritized, and the country becomes an object of international activity, rather than an equal contributor. Essentially, the country is swept into the dominant powers' game – dropping its production efforts, remaining underdeveloped, and becoming more fully entrenched in a dependency pattern. This route of least resistance, in which production and dissemination behaviors are basically left to their natural, unhindered development, describes the traditional reality for the majority of the periphery in the IR discipline. This is unsurprising, since IR production from the core is overwhelmingly powerful. Without intervention, continuation on this route will arguably lead to further advancement of the current hegemony, despite some self-reflection on the state of the IR discipline/theories, and therefore a continuing, if not growing gap between the knowledge and the reality of global affairs.

A second route, the polar opposite of the first, has a dependent country rejecting the dominant system. This revolutionary approach is based on the understanding that development as a dependent entity within the system is impossible, and that only through complete ‘delinking’Footnote 81 can the yoke of dependency be broken. Despite its intended goal of eventual reintegration, such apparently autarchic efforts for self-reliance, in which the country produces locally, and consumes only what it produces, may run the risk of lengthy isolation. The parallel to this approach in a theory of symmetric interdependent development within the IR discipline would suggest a rejection of working within the system,Footnote 82 arguing that years of dialog, and thousands of workshops promoting a more equal balance,Footnote 83 will achieve little. These calls for radical change are extremely important, but taken to extreme, full rejection of the current system runs the risk of minimal interaction and closed systems of knowledge – the antithesis of a symmetrically interdependent global IR.

Economic theory and trade practices suggest an alternative, comparative advantage model. Essentially, a dependent state turns a local advantage into a strategic product and prioritizes its trade policy accordingly – promoting that particular globally relevant sector or product, making sure the dominant powers in the system have a vested interest in it, and then ensuring it is made available to them in an acceptable format. One may also consider this as a more nuanced interpretation of ‘delinking’, which Amin explicitly wrote did not in fact equal autarky, but rather, the defining of new criteria based on ‘a law of value, which has a national foundation and a popular content’Footnote 84 independent from the dominant rationality of the core. For global IR, this may be interpreted as the periphery defining new value by producing globally relevant local scholarly products, packaged in a familiar language and style that can grab the attention of core consumers. Moreover, based on the principle that gains of trade come from differences, these products have to provide novel tastes that the core cannot simply produce on its own. In other words, for true symmetric interdependent global IR, today's periphery must produce something the core needs, but either cannot – or would find too costly to – make by itself.

Concrete steps to applying such a comparative advantage model, thereby reducing the current dependency and paving pathways to symmetric interdependency and thus genuine globalization of the discipline, may be described along three lines: pedagogical, institutional, and production.

Pedagogical

Radical changes must first take place in the classroom, because these graduate training ‘factories’ are where dependent minds are produced. For a true global IR to develop, tomorrow's main producers have to be liberated from dependent cognition, and socialized into the possibility of symmetric interdependency. Although pedagogical change must occur everywhere, the core initially bears the primary responsibility, not only for the purpose of setting a good example but also because, in the current dependent context, leading IR producers from the periphery are most likely to get socialized in the core. Pedagogical change, focused in particular on graduate IR theory classrooms, must be made in both process and content.

First, there should be a democratization of graduate IR theory teaching. In line with widely accepted educational theory, IR classrooms should adopt a less hierarchical, more student-centric approach, in which, rather than being dictated from above, a diverse student body's needs are taken into consideration when determining the focus and prioritization of content. Simultaneously, a multiplicity of instructors' perspectives should also be promoted by encouraging practices such as team-teaching in IR theory courses. For specialist courses it makes sense to have a single, expert individual instructor, but for IR theory training, students should be actively exposed to a wide range of views. If the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us nothing else, it is that course instructors and students don't need to be all in the same place at the same time. We can now easily imagine IR theory classrooms, no matter where they are based, presenting students with truly global views, offered by diverse faculty from all geographical and paradigmatic backgrounds. Moreover, the simple practice of bringing in outside voices in this manner could help sensitize all instructors to their own parochialism, encouraging a reflectiveness that itself could contribute to more global IR.

Second, and the most obvious implication of this study's findings, there needs to be a globalization of IR theory curricula. Without a diversification and expansion of the content of course syllabi and overall program curricula, the dependent structure of the IR discipline will remain solid, and true global IR cannot be achieved. Yes, the standard content of the IR theory curriculum needs to be covered, but a dependent structure is far less likely to change if the presumed agents of that change are never given a glimpse at what an alternative might look like. Clearly, IR theory graduate syllabi must include more works featuring homegrown theorizing from outside North America and Western Europe. Again, the responsibility for this starts in the core, because if homegrown inclusion becomes fashionable there, it is more likely to follow in the periphery as well. Currently, although our data show that in fact core IR theory course instructors do include fractionally more examples of homegrown theorizing in their syllabi than their periphery counterparts, the percentage is still abysmally low, and is far from enough to serve as a sign of anything but tokenism in a settled, dependent system.

Institutional

There are both informal and formal institutional factors that can help liberate the IR discipline from its current dependency status. Informally, we should not be afraid of growing numbers of regional or national ‘hubs’ of IR. Rather than as signs of fragmentation, parochialism and a moving away from global IR, their growth may be viewed as a stage of enrichment. As occurred within core IR, when a critical mass is produced within these hubs, self-reflection and debates also naturally emerge, for example, addressing methodological orientations in local knowledge production.Footnote 85 With time, local hubs can develop into sources of both healthy competition and collaboration in a global IR discipline.

More importantly, there are formal, concrete measures that must be taken to ensure the growth of an interdependent global IR. Current IR theory production and dissemination venues, that is, journals and presses, constitute a controlled and exclusively regulated market. To achieve a more globally legitimate and relevant agenda setting, there must be a push for a global marketplace of IR theory dissemination, a ‘global fair’, with genuinely open and transparent access. Periphery journals are the building blocks for this global fair of IR knowledge. They must, therefore, be promoted and supported, so they can become competitive counterparts to existing top IR journals. Only such an open global marketplace of journals rather than a core-managed one, can steer a route out of dependency to symmetric interdependency, and thus, to a true global IR. Again, the core must take the primary initial responsibility. If core scholars are serious about global IR, they must set an example by publishing in or serving as editors for these periphery journals, so that periphery scholars too will be emboldened to follow suit rather than focusing their primary energies on both publishing in and assigning readings from core venues alone.

Equal access to the global marketplace also means that it must be a multilingual one. Moving beyond the linguistic hegemony of English is critical if IR hopes to achieve core-periphery ‘dialog’ that goes beyond the label alone. Current calls for dialog abound, but without a preceding practice of pluralized and ‘joint-venture’ theory production and dissemination, ‘dialog’ remains merely talk. Of course, multilingual access has its own complications: how widespread should it be? A global marketplace including ‘all’ languages is clearly impractical, but doesn't the alternative run the risk of just creating a few linguistic hegemonies instead of one main one? Moreover, couldn't multilingualism inadvertently lead to less access, as it shunts consumers into narrower pools of knowledge in language(s) they understand? Although these are legitimate questions, the goal of a multilingual marketplace should be seen as an interim solution, and well worth the risks. Even if in the short term it leads to hubs of IR theory production along with new linguistic hegemonies, it will still greatly advance fairer access on a relatively more even linguistic playing field. For an interim period, this will at minimum encourage more diverse participation, and thus provide material for more interdependent development until the inevitable time when technological advancements in automatic translation make such blunt linguistic measures irrelevant.

Production

Which brings us to the final point: the periphery's responsibility to identify and produce globally relevant, locally manufactured ‘products’ that can be traded in a symmetric interdependent system of global IR, in other words, homegrown IR theories and concepts. We should remember that every homegrown concept has the potential to become universal, just as today's leading IR theories and paradigms were once locally produced and homegrown themselves. Laying the groundwork for homegrown production are the preparatory pedagogical changes outlined above. Rather than encouraging memorization and repetition, or at best, application, of standard IR theories, democratization of the classroom and globalization of the IR curriculum will make it possible for everyone, regardless of background, to imagine, ‘what can I offer that is original?’ ‘What do I know that others don't know?’ ‘What is my best possible contribution?’ Future and present IR scholars around the world will gain the sense that anybody's ideas can matter, and these ideas can play a mutually beneficial role in the larger discipline.

Add to this the further formal institutional preparation of an open, multilingual marketplace for fair competition, and homegrown theorizing becomes a meaningful and feasible option both in imagination and in practice. Current patterns of dependent development are designed to regenerate the core's hegemonic theoretical production. Emboldened homegrown theorizing represents a comparative advantage-based product. Strategic trading of homegrown knowledge and conceptual ideas in a free and fair global marketplace will lead to interdependent knowledge production and consumption and ultimately to a genuine global IR. Ultimately, it is this type of global IR that may be our best hope for meeting the challenge of growing crises in the IR discipline.

Acknowledgements

We thank several professors, most notably Nathan Andrews, for their contributions to the project by providing us with graduate-level IR theory syllabi. We are also indebted to our research assistants and interns whose efforts made this project possible. Finally, we owe a great deal of gratitude to the four anonymous reviewers and to the journal editors for their extremely constructive suggestions and assistance throughout the process.

Appendix 1: List of countries in the studies

Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Egypt, France, Gambia, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Hungary, India, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Japan, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Lebanon, Mexico, Morocco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Pakistan, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Uganda, United Kingdom, United States of America, and Uruguay.

Appendix 2: Results of the ANOVA

*Descriptive Statistics

Core vs. semi-periphery vs. periphery

Descriptive statistics

Anglosphere vs. rest

Descriptive statistics

**Homogeneity tests

Core vs. semi-periphery vs. periphery

Anglosphere vs. rest

***Multivariate tests

Core vs. semi-periphery vs. periphery

Education: Anglosphere vs. rest

****Tests of between subjects effects

Education: core vs. semi-periphery vs. periphery

Tests of between-subjects effects

Education: Anglosphere vs. rest

Tests of between-subjects effects