In the last decade, interest in neuroscience and its insights into cognition and emotion has arisen within international relations (IR), though interventions remain tentative. Wariness is understandable given the historical misappropriation of biology in naturalizing behavior and essentializing identities. Nonetheless, we see emerging a non-deterministic, neuroscientifically-informed scholarship, heeding critiques of positivism arising from IR's Third Debate. Holmes (Reference Holmes2014), for example, argues that neuroscience and philosophy of the mind can overcome the binary of structure and agency, operating as a via media. Investigating emotions' role in moral reasoning, Jeffery (Reference Jeffery2014b) draws on cognitive, decision, and social neuroscience, highlighting how brain structures and functions elucidate the ways emotion infuses social interaction.

In a forum on emotions and world politics in this journal, neuroscience features prominently (Bleiker and Hutchison Reference Bleiker and Hutchison2014). Within it, Jeffery contends that experimental neuroscientific findings, allied with contextual facts generated from interpretivist approaches, form webs of meaning that can explain and interpret the dynamics of IR (Reference Jeffery2014a, 588). For Bially Mattern, neuroscience substantiates features of emotions long suspected by social scientists: it endorses views that emotions ‘are intersubjective social phenomena as much as they are biological subjective ones’, and that emotions and cognition are deeply intertwined (Reference Bially Mattern2014, 590). Crawford (Reference Crawford2014), employing neuroscientific evidence about fear and empathy, suggests that emotions are institutionalized and feedback through the complex adaptive systems of world politics. Mercer (Reference Mercer2014a) highlights the complex interplay of neurophysiology with culture, emphasizing that culture regulates social emotion and changes the brain's architecture.

Among IR scholars venturing into neuroscience and emotion, points of consensus emerge. First, emotions have a neurobiological basis, but are irreducible to brains. Second, social interaction influences neurobiology, particularly given the phenomenon of neuroplasticity, whereby neural structures are environmentally shaped. Accordingly, culture and institutions influence the experience and expression of emotions. Third, emotion and cognition form a tight nexus, implicating emotions in nearly all aspects of decision making.

Despite acknowledgement of neuroscience's significance for emotions research in IR, a quandary arises. Bially Mattern (Reference Bially Mattern2014) claims that theorizing emotions as a force in world politics requires a clear conception of emotion, which is hindered by the seemingly indistinguishable nature of cognition and emotions. Mercer (Reference Mercer2014a) notes this complication, citing neuroscientists Zaki and Ochsner, who compare separating emotion from cognition to slicing a cake into flour and sugar. Consequently, Bially Mattern proposes that the emotion/cognition nexus elicits not just greater attention to emotion, but a ‘radical reconceptualization of the human experience and consciousness’ (Reference Bially Mattern2014, 591).

This paper argues that affective neuroscience and depth neuropsychology address this quandary, offering clearer articulation of the emotion/cognition nexus than hitherto advanced in IR, and a reconceptualization of human experience and consciousness. Affective neuroscience, coined and pioneered by Jaak Panksepp (1942–2017), adopts a broader evolutionary and ethological perspective on emotions. It develops an integrative approach, which reveals evidence of common mammalian emotional systems, and advances a comprehensive hierarchical view on how emotions are generated and modulated in the brain. Though IR scholarship cites developments from cognitive and behavioral neuroscience, affective neuroscience and depth neuropsychology, which investigates the divide between conscious and unconscious mental processes, remain underexplored.Footnote 1 Distinct from other subfields, Panksepp's affective neuroscience theorizes primary emotions that operate separately from cognition, and which are integral to consciousness itself. Though cognition and emotion are intertwined, they are not inextricable. This separation allows more precise theorization of how emotions influence cognition and behavior.

Together with depth neuropsychology, affective neuroscience offers a route toward ‘deep theorizing’ in IR, providing novel perspectives on the motivations of individuals and social groups (Berenskötter Reference Berenskötter2017). By disarticulating it from emotion, cognition is theorized distinctly from other approaches that treat them as indistinguishable. Cognition is retheorized as playing an emotional regulatory role. Specifically, cognition and cognitive constructions are theorized as subserving the goal of attenuating emotional consciousness. This insight is significant for IR, suggesting a drive for emotional quiescence that overdetermines the operation of all social institutions.

Adopting a comprehensive understanding of neural substrates and neuro-psychodynamics furthers scholarship on emotions within IR. Belatedly following calls for emotion's study in international politics (Mercer Reference Mercer1996; Crawford Reference Crawford2000), affect-related research has proliferated. After a long-standing elision of emotion, a hangover of the behaviorist revolution that expelled terminology about ‘mental states’ (Kurki Reference Kurki2008, 64), IR scholars are actively engaged in the ‘affective turn’ of the social sciences (Clough and Halley Reference Clough and Halley2007). Wide-ranging scholarship has examined the impact of emotional states on international politics, including anger (Lebow Reference Lebow2008), anxiety (Widmaier Reference Widmaier2010), cruelty and humiliation (Linklater Reference Linklater2011), empathy and compassion (Pedwell Reference Pedwell2014, Head Reference Head2016), happiness and joy (Penttinen Reference Penttinen2013), mourning (Butler Reference Butler2003) and vulnerability (Beattie and Schick Reference Beattie and Schick2013). It marks a recovery of an earlier appreciation of emotion's salient role in IR, particularly by classical realists (Schuett Reference Schuett2010, Solomon Reference Solomon2012, Ross Reference Ross2013a). Affective neuroscience, though, allows a clearer conceptualization of how these emotional states are constituted, and how they are interrelated.

Combined with depth neuropsychology, affective neuroscience can advance existing macro studies focusing on group emotions. Sasley (Reference Sasley2011), for example, employs intergroup emotions theory to illuminate how group emotions are more than an aggregation of individuals' emotions. Group emotion entails a process producing emotional convergence, inducing collective action tendencies. Similarly, Ross (Reference Ross2013a), moving beyond the analysis of discrete emotions, investigates how interconnected emotional responses are generated and constitutive of social interactions. Hutchison (Reference Hutchison2016) argues that ‘affective communities’ are forged out of shared emotional understandings of trauma. Such approaches, capturing the integral nature of affect in shaping intra- and intergroup dynamics, are enhanced by a further conceptualization of the intra-psychic economy of self-organization. Understanding neural predispositions entailed in subject formation, as offered by depth neuropsychology, can help bridge the interscalar divide between micro and macro approaches to emotions in IR.

Providing a more in-depth treatment of neuroscience, this analysis argues the case for a non-deterministic motivating force that animates social construction and identity formation. It applies research by Panksepp in affective neuroscience and Mark Solms in neuropsychology, among others, which suggests a propensity of higher corticalFootnote 2 brain regions to discharge and minimize the arousal of subcortical regions, from whence originate core affects and consciousness. This propensity aims at overcoming affective disturbances and limiting consciousness. It arises in higher cortical regions to resist entropy, a tendency toward disorder and randomness. This counter-entropic predisposition can eventuate in diverse second-order behaviors, behaviors shaped by one's socio-historical context. The resulting neuro-psychodynamic, though not a basis for social prediction, helps explain the microphysics of power that lend inertia and continuity to the complex of social relations defining contemporary IR.

Conceptualizing this drive for emotional quiescence, the paper reassesses how we understand institutions and behaviors in IR. In doing so, it departs from more rationalist accounts, arguing that institutions are the products of historical efforts to corral and attenuate the emotional arousal of their constituents. It is argued that institutions, particularly the state, indirectly foster conditions of automaticity of thought and behavior for their subjects, that is, thought and behavior operating without the need for conscious arousal. In line with the abovementioned counter-entropic neural predisposition, automaticity helps minimize emotional excitation and maintain psychical repose. Institutions, thusly, are conceptualized as affective technologies that arrest psychical entropy for their constituents, and institutions' longevity depends on providing conditions that attenuate affective consciousness.

Exploring how the neural apparatus provides a substrate for the social self, this analysis resists biological or ‘neuro-reductionism’ (Martin Reference Martin, Thomas and Ahmed2004). Though neural predispositions delimit how we experience the world, they do not furnish a parsimonious psychology for explaining human behavior. Attempts to locate neural correlates of complex social behavior, that is, sufficient conditions in specific brain regions, are rejected. Recent neuroscience suggests that almost all psychological specializations of the ‘higher’ mammalian neocortex are learned, not intrinsic (Panksepp and Biven Reference Panksepp and Biven2012). In contrast to neural correlates, this analysis adopts neuroscientist Georg Northoff's (Reference Northoff2011) notion of neural predispositions, which entail the neural conditions necessary but non-sufficient to explain psychological processes. Accordingly, this analysis remains skeptical of interdisciplinary endeavors like neuroeconomics, which looks to develop ‘linkages between measurable neural activity and utility-like concepts derived from economics’ (Glimcher Reference Glimcher2011, 397–98). Given the plasticity of neural circuitry in higher cortical regions, charting such correlates can run afoul by naturalizing that which is socially conditioned.Footnote 3

The paper is divided into four sections. The first section employs affective neuroscience to illuminate affect's defining role in consciousness and omnipresence in social behavior. It challenges the conspicuous absence of emotion in mainstream IR theories. The second section elaborates higher cortical regions' function in modulating and inhibiting affect. Here it is argued there exists a counter-entropic neural predisposition that contingently produces the utilitarian rationalities foundational to certain approaches within IR. This counter-entropic predisposition drives efforts to maintain self-coherence and self-continuity. The third section lays out three key implications of affective neuroscience and depth neuropsychology for IR as we move from the micro-individual to the macro-institutional level of emotion. First, they offer a reconceptualization of motivations and psychological ontology. Second, they cause us to reassess the role of institutions, especially the state, in regulating emotions. Third, the section outlines how these neuroscientific approaches complement critical and post-positivist theoretical perspectives, which avoid engagement with natural science and treat the body as a blank slate. The concluding section sketches a potential application arising from IR's engagement with the neuroscience of emotion, specifically a therapeutically-attuned approach. Understanding the self- and social regulation of affect, as well as emotions' plasticity, allows for reproblematizing contemporary issues confronting scholars and practitioners of IR.

Basic affects and emotional consciousness

Despite ferment surrounding affect and emotions in IR, definitional differences abound. Some advise against conflating affect and emotion (D'Aoust Reference D'Aoust2014, Hutchison Reference Hutchison2016). Oft-cited social theorist Brian Massumi sustains that affect and emotions ‘follow different logics and pertain to different orders’ (Reference Massumi2002, 27). He conceives affect as a nonconscious intensity driving psychical life, and emotion as a ‘qualified intensity’. Emotions, Massumi contends, are the insertion of affect into ‘function and meaning’ (Reference Massumi2002, 28).

Employing affective neuroscience, though, this paper eschews this distinction, and disputes that affect is nonconscious. Affects, for Panksepp (Reference Panksepp2010), are a range of subcortically-based neural processes, which are divided into three types: sensory affects (related to external stimuli, e.g. taste, hearing), homeostatic affects (related to internal stimuli, e.g. hunger) and emotional affects. Here, unless stated otherwise, affects refers to emotional affects, and is used interchangeably with emotions. According to Panksepp (Reference Panksepp1998a), emotions are conscious feeling states that are both visceral and psychic. They are ‘psychoneural processes that are especially influential in controlling the vigor and patterning of actions in the dynamic flow of intense behavioral interchanges between animals, as well as with certain objects during circumstances that are especially important for survival’ (Panksepp Reference Panksepp1998a, 48).

Not entirely dissimilar to Massumi's distinction, this paper differentiates basic or primary emotions from complex social emotions. Primary emotions, like Massumi's affect, are non-representational and non-cognitive. Social emotions, however, arise from primary emotions. Massumi's separate conceptions of affect and emotions impede grasping how primary emotions are modulated, intertwined and channeled to form social emotions.

Exploring affective neuroscience, this section aims to render a clearer delineation of emotions from cognition, and addresses a cursory knowledge of neuroscience within IR. Affective neuroscience can impart greater precision in defining the psychological ontologies informing assumptions about social dynamics. Also, a deeper engagement helps minimize inaccuracies arising with the popularization of neuroscience (O'Connor et al. Reference O'Connor, Rees and Joffe2012). Though the prefix ‘neuro-’ is fashionable, undertaking such interdisciplinary work requires grounded neuroscientific knowledge.

The emergence of affective neuroscience owes substantially to the research of Jaak Panksepp, though his position on emotions is but one within a contested, evolving field.Footnote 4 Disputing the prevailing behaviorism in the 1980s, he contributed to the study of the nature and causes of human emotions at a neurological level, challenging conventions within neuroscience and psychology (Panksepp Reference Panksepp1982). His research advanced this distinct subfield, which sought an understanding of basic emotions evident across mammalian species, emotions that, from an evolutionary perspective, confer reproductive success and fitness (Panksepp Reference Panksepp, Puglisi-Allegra and Oliverio1990, Reference Panksepp1992).

Panksepp's affective neuroscience contrasts with behavioral and cognitive neuroscientific approaches to emotion more commonly cited within IR. Within traditional behavioral neuroscience, examining how neural processes generate behavior, emotional experience was disregarded. Methodological imperatives of objective, empirical observation precluded subjective emotional experiences from investigation. Though cognitive neuroscience, drawing on cognitive psychology and neurobiology, recognizes emotions' significance, they are conceived as higher-level cognitions (Ortony and Turner Reference Ortony and Turner1990). Emotions are largely theorized to originate in the neocortex, the area of the brain responsible for sensory perception, language, reason and volitional motor control. This contrasts with Panksepp's subcortical perspective, which is a source of contention. Notably, cognitive neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett contests the existence of anatomical correlates for basic emotions like anger, fear and sadness. For Barrett (Reference Barrett2006), emotions are not ‘natural kinds’, but products of cortically-generated categorizations. Panksepp's research refutes this cognitivist conception of emotions as the ‘cortical readout’ of subjective states. It critiques an arguably latent anthropocentricism in cognitive neuroscience, which reinforces the view that few non-human species experience emotional feelings (Panksepp Reference Panksepp, Lewis, Haviland-Jones and Barrett2008).

Affective neuroscience questions both emotion's neglect and the Cartesian duality of instinctual animals and sentient humans, demonstrating the centrality of emotion to the conscious experience of all mammals (Panksepp Reference Panksepp1998a). Theorizing emotions as primary processes of the neural apparatus, it disputes ingrained notions about the nature of higher psychological processes and the basis of consciousness.

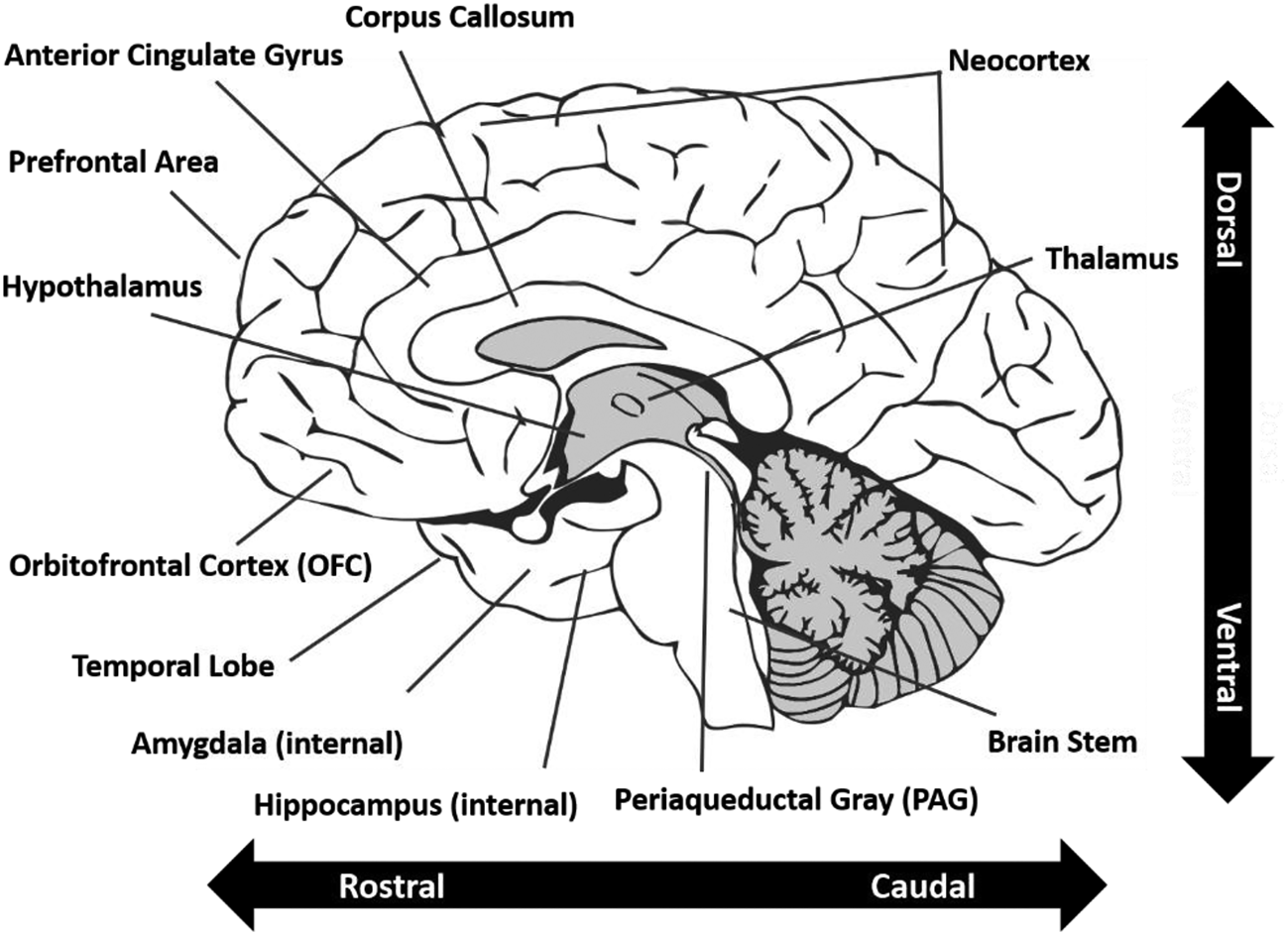

This section challenges agential conceptions within IR by employing insights from affective neuroscience, emphasizing sub-neocortical primary processes in generating basic affects (Panksepp Reference Panksepp1998a) and, relatedly, consciousness itself (Solms and Panksepp Reference Solms and Panksepp2012; Solms Reference Solms2013). Unlike complex psychological processes such as emotional reflection and regulation, which are socially conditioned, discrete regions implicated in generating basic emotions can be localized.Footnote 5 Neuroimaging studies indicate discrete brain activations for emotional states such as happiness, sadness, anger, fear, and disgust (Vytal and Hamann Reference Vytal and Hamann2010). Panksepp's research suggests that processes producing raw affect are more caudal (toward the back of the head) and ventral (inferior or closer to the neck) and, evolutionarily, more ancient. These basic emotions generate an energetic form of consciousness he refers to as ‘affective consciousness’, countering views of consciousness as a cognitive manifestation (Panksepp and Biven Reference Panksepp and Biven2012).

By reconceptualizing agency herein, the intent is to further destabilize implicit notions of rationality within mainstream IR theories, which treat affect as a disturbing influence extrinsic to reasoning. Though classical realism was cognizant of emotion's role in statecraft (Ross Reference Ross2013b), with Morgenthau (Reference Morgenthau1947) arguing the advance of ‘reason over nature’ was underpinned by ‘emotional forces’, post-war IR typically conceived rationality and emotion as binary opposites. Rational-choice theories, predominating IR during the post-war era, have often assumed fixed exogenous conceptions of preference, with motivation defined as economically-maximizing or power-seeking. Mercer (Reference Mercer2005) argues IR scholars have commonly subscribed to a myth of a baseline rationality that excludes psychology and emotions. Though outside IR rational-choice theorists have argued for emotions' importance in reasoning (Elster Reference Elster1999), and for their inclusion in modeling preference formation (Loewenstein Reference Loewenstein2000), IR scholarship has belatedly sought to integrate insights about emotion into such approaches (Gross Stein Reference Gross Stein, Carlsnaes, Risse and Simmons2013).

Emotions, here, are conceptualized as psychical drives energizing agency, contradicting the rational instrumentalism permeating many approaches to IR. Rationality, when defined in terms of abstract utility, inadequately captures the functioning of the complex, non-binary affective systems elaborated here. Subcortically generated affects do not directly translate into calculative, instrumental rationalities, but can be socially conditioned as such.

Beyond contesting rational-choice theories, as discussed later, this conceptualization of emotions can complement constructivist and poststructuralist IR approaches, which emphasize the role of norms and normalization in guiding behavior. Understanding affect's role in subject formation and motivation can elucidate the compunction to follow a logic of appropriateness, of internalizing prescriptions for legitimate behavior (March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1998).

Possibilities for reconsidering emotions in IR and the social sciences have widened with findings about the neurobiology of affect attained through neuroimaging advances. Chief among these are positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) (Phan et al. Reference Phan, Wager, Taylor and Liberzon2002). Earlier knowledge of the neurobiology of emotions came from lesions studies and electrical and chemical stimulation experiments. PET registers brain activations by measuring blood flow to specific regions, detecting injected radioactive compounds. fMRI detects activations through the altered magnetic properties of hemoglobin where metabolism occurs.

Despite showing the functional integration of the brain's distributed, hierarchically organized regions, imaging has limitations in studying emotion, which requires recourse to broader, interdisciplinary approaches. fMRI has poor temporal resolution, too slow to capture rapid activation sequences. Test subjects must remain stationary, limiting experimental parameters; speaking alone can produce excessive movement for fMRI (Sweet Reference Sweet, Cohen and Sweet2011). Addressing these limitations, Panksepp's approach combines neuroimaging, brain manipulations, animal behavioral studies and self-reported mental states (Reference Panksepp1998a).

Sagittal brain sectionFootnote 6

Affective neuroscience's ‘psycho-neuro-ethological triangulation’ is pertinent for theorizing emotions and reason in IR. Affective neuroscience postulates that the core emotional affects we experience are shared mammalian evolutionary inheritance, and aims to elucidate homologous neurodynamic processes (Panksepp Reference Panksepp1998b). Integrating evolutionary neuroethology elucidates cross-species emotional systems, allowing appreciation of the ways emotions are modulated and transmuted in human social interaction. These offer insights into the causes of emotions, and a basis for theorizing motivation in the social sciences.

Panksepp's approach to emotions, seated in ancient brain structures, takes partial inspiration from the now classic evolutionary neuroethology of Paul MacLean (Reference MacLean1990), specifically the latter's ‘triune’ brain model. Panksepp adopts aspects of this model for heuristic reasons, providing a simplified overview of mammalian neuroanatomical organization. At the base of MacLean's three-layered model is the ‘protoreptilian formation’, or ‘reptilian brain’, the source of basic affects. The defining feature of these affects is that they are ‘subjectively agreeable or disagreeable’ (Reference Panksepp, Puglisi-Allegra and Oliverio1990, 423–25). The next layer, the ‘paleomammalian formation’, houses the limbic system, which MacLean proposed as the emotional brain. This system integrates the amygdala, implicated in emotional reactivity and primary memory processing, the hippocampus, involved in declarative memory formation, and the hypothalamus, key for nervous and endocrine regulation. For MacLean, the paleomammalian formation is responsible for more complex emotions, including desire, anger, fear, sorrow, joy and affection (Reference MacLean1990, 438). The third, ‘newest’ layer is the ‘neomammalian formation’, implicated in cognitive/rational deliberation. Though Panksepp disagrees with MacLean about the nature and quality of affects generated in ‘older’ brain regions, he concurs that the source of emotions is not the neocortex.

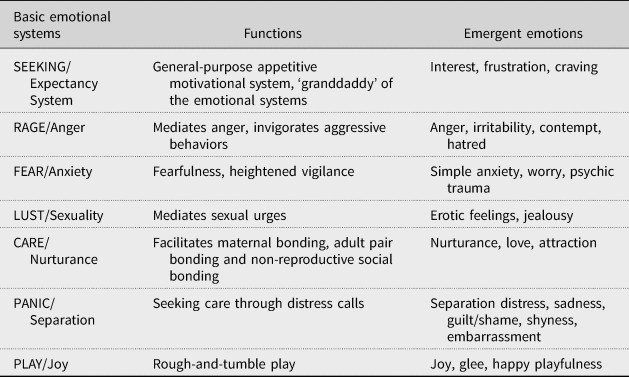

Panksepp's research on the subcortical affective structures yields a unique taxonomy of emotions, instructive for IR scholarship in which the interrelationship between emotions remains under-theorized. He identifies seven discrete emotional systems emanating from ancient subcortical structures (Panksepp and Biven Reference Panksepp and Biven2012). These include SEEKING (expectancy), FEAR (anxiety), RAGE (anger), LUST (sexual excitement), CARE (nurturance), PANIC/GRIEF (sadness), and PLAY (social joy).Footnote 7 Contrasting with MacLean, Panksepp locates the raw emotions that contribute to social emotions in the midbrain, rather than more dorsal (toward the top of the head) regions. Here, along with others such as LeDoux (Reference LeDoux2003), he contests preponderant views of emotions being seated in the limbic system.Footnote 8 These seven systems, generating unconditioned raw affects, are designated as primary processes, and produce differing states of affective consciousness. These systems, he theorizes, provide the elements for composite or mixed emotions, including jealousy, shame, guilt, trust, empathy, blame and pride, which take shape in higher brain regions (Panksepp and Biven Reference Panksepp and Biven2012, 19) (Table 1).

Table 1. Panksepp suggests emergent emotions join different systems (e.g. jealousy combines separation distress and anger). Based on Panksepp (Reference Panksepp2000)

For IR, insights into basic affective systems complicate constructivist views on emotions. Constructivists generally adopt a cognitivist stance, with emotions understood as intersubjectively constituted cognitive beliefs (Ross Reference Ross2006). In contrast, the raw emotions generated by these distinctive affective systems lack cognitive content, creating feelings Panksepp describes as ‘goodness’ or ‘badness’ (Reference Panksepp1998a). RAGE produces raw emotion that can become anger, aggression and hatred, but at the primary-process level generates emotional feelings without objects. When induced, these emotional states are never neutrally received. Animals appear to dislike the arousal of FEAR, RAGE, PANIC/GRIEF and like that of SEEKING, CARE, LUST and PLAY (Panksepp and Biven Reference Panksepp and Biven2012). These raw emotions are present in our conscious states, but do not always have immediate cognitive associations. Their presence supports arguments by Holmes (Reference Holmes2015) about affective intuitions, or ‘aliefs’, which produce belief- and norm-discordant behavior in international politics.

Basic emotions, though, do not evidence an essentialist psychology, nor entirely undermine constructivist engagements with emotion. Though basic emotions can be rewarding or punishing, this does not validate hedonic conceptions of motivation. Reward at a neurological level, Panksepp stresses, lacks singular definition. It is not a homeostatic mechanism, releasing pleasure upon the re-equilibration of biological imbalances.Footnote 9 Each affective system is activated by different combinations of neurochemicals in varying regions of the lower brain (Panksepp Reference Panksepp2010). The reward elements of positive emotional affects activate distinct sites. Panksepp speculates that at the tertiary-process conceptual level, within the cortical or third level of the brain, we ‘conflate feelings into positive and negative – “good” and “bad” – categories, but that is a heuristic simplification’ (Reference Panksepp2010, 536). It is at this tertiary level that constructivism's focus on social conditioning, as later discussed, comes into play.

Common to these systems is the involvement of an ancient brainstem structure known as the periaqueductal gray (PAG), a notion that challenges theories that seat emotions in limbic and cortical regions (Briesemeister et al. Reference Briesemeister, Kuchinke, Jacobs and Braun2014). The PAG is a small gray matterFootnote 10 body composed of functionally discrete columns. Negative emotions or unpleasure are localized in its dorsal columns, and positive emotions in its more ventral columns (Behbehani Reference Behbehani1995; Solms and Turnbull Reference Solms and Turnbull2002). Meta-analysis corroborates this region's role in generating emotional states (Buhle et al. Reference Buhle, Kober, Ochsner, Mende-Siedlecki, Weber, Hughes, Kross, Atlas, McRae and Wager2013; Motta et al. Reference Motta, Carobrez and Canteras2017).

Situating the kernel of the emotional economy in the PAG disputes traditional neuroscience and is pertinent for IR scholars. For constructivists and poststructuralists, it introduces pre-social, pre-discursive dimensions of affect that require consideration. It substantiates Holmes' arguments about latent emotions that lead to ostensibly irrational decisions by policymakers (Reference Holmes2015). Further, it supports scholarship contesting the prevailing theorization, or lack thereof, of the body in IR. Bodies, such research emphasizes, are co-constitutive with political structures (Wilcox Reference Wilcox2015). The presence of subcortical affects contradicts conceptions of a tabula-rasa body, on which the social is inscribed.

Another key facet of Panksepp's conceptualization of emotions, confounding claims of some IR scholars, is that the raw affects generated in the PAG are constitutive of consciousness. Rather than epiphenomenal, emotions are intrinsic to consciousness. In evolutionary terms, affective consciousness confers survival advantages, producing a basic sense of how we are feeling. These valenced feelings indicate how we stand in relation to our environment, and nudge us into salutary actions (Panksepp Reference Panksepp1998b, 567). Homologous structures in the ancient mammalian brain, Panksepp theorizes, are scaffolding for a primordial yet coherent self. They stimulate ‘anoetic’ consciousness (Vandekerckhove et al. Reference Vandekerckhove, Bulnes and Panksepp2014), consciousness without cognitive content, upon which secondary and tertiary processes constitute higher-level, knowing consciousness. This affective consciousness runs counter to positions of some IR scholars, who view affects operating non-consciously.Footnote 11

In humans, evidence of subcortical affective consciousness manifests in children with the congenital condition hydranencephaly, in which the neocortex fails to develop, resulting in a fluid-filled cranial cavity. Though this condition was thought to produce a permanent vegetative state, afflicted children show discriminative awareness. This is seen in their ‘distinguishing familiar from unfamiliar people and environments, social interaction, functional vision, orienting, musical preferences, appropriate affective responses, and associative learning’ (Shewmon et al. Reference Shewmon, Holmes and Byrne1999, 364). Corroborating this, Merker (Reference Merker2007) reports that these children, when exposed to environmental events such as caregivers' voices or loud noises, express pleasure by smiling and laughing, and aversion by fussing, crying, and arching their backs.

Affective consciousness has significant bearing for IR, as emotions are omnipresent and overflow the ostensibly rational sphere of international politics. Basic emotions cannot always be modulated, as elaborated in the next section, forming part of what Robert Jervis (Reference Jervis1970) terms nonmanipulable indices. Indices are involuntary behaviors informing how perceivers evaluate others' intentions and make predictions. Building on Jervis, Hall and Yarhi-Milo (Reference Hall and Yarhi-Milo2012) claim that affective information, unintentionally transmitted in high politics, influences assessments of sincerity and often overrides intentionally communicated signals.

Ultimately, affective neuroscience yields novel perspectives on the fundaments of selfhood and confounds assumptions within IR theory, but it also validates growing interest in emotions research. It undermines rational-choice methods that disregard psychology and emotion in preference formation. Simplistic conceptions of utility are less tenable considering evidence of multiple endogenous and overlapping emotional systems. Providing evidence of the centrality of emotional systems in how we respond to stimuli, affective neuroscience underscores IR's need to integrate emotion into theories of individual and collective behavior.

The raw affective systems theorized by Panksepp, though, provide only a substrate for complex, learned social behavior of interest to social science. Comprehending such behavior necessitates going beyond unconditioned primary-process emotions. It requires understanding conditioned responses arising with secondary learning processes in the limbic system, and complex cognitive functions of the neocortex. The next section, integrating theories of neuro- and psychodynamics, outlines processes co-constitutive of social selfhood, offering a view on motivation that casts light on social dynamics that preoccupy IR scholars.

Higher-level emotions and neural predispositions

Insights regarding basic emotions, though challenging ontological assumptions about affect within IR, are not readily applicable to the field's immediate concerns. They reveal that emotions are fundamental to subjectivities and rationalities, yet the picture of how basic emotions influence social dynamics remains incomplete.

This section outlines how raw affects are regulated and modulated, producing social emotions and complex psychodynamics relevant to IR scholars. It looks at secondary processes, which provide learned responses to environmental stimuli and engender basic ‘noetic’, or knowing, consciousness. It then explores tertiary processes that precipitate ‘auto-noetic’, or self-aware, consciousness (Vandekerckhove et al. Reference Vandekerckhove, Bulnes and Panksepp2014). The section integrates theorizations of neuro- and psychodynamics from depth neuropsychology, conceptualizing how affective and cognitive processes intermesh in autonoetic consciousness.

With neural predispositions, we can theorize a generalizable motivation arising with cortical self-awareness, a force relevant for interpreting social phenomena in IR. Produced by secondary and tertiary processes, and energized by basic affective systems, this motivating force aims at attaining self-coherence. Contrasting with hedonic, instrumentalist rationalities, this neural predisposition can induce negative emotional states to preserve a sense of self, instigating behaviors that might otherwise be deemed irrational. Importantly, though neural predispositions are self-regarding, they are not socially deterministic, giving rise to multifarious social relations.

Secondary processes entail associative learning and modulate primary affective consciousness. They involve brain nuclei and regions associated with the limbic system and other subcortical structuresFootnote 12 implicated in habit learning and in selecting/enabling cognitive, executive, and emotional programs stored in the cortex (Leisman et al. Reference Leisman, Braun-Benjamin and Melillo2014). These regions have pathways to the PAG, and induce and modulate affects in response to external and internal stimuli. Panksepp and Solms (Reference Panksepp and Solms2012) explain that secondary processes operate unconsciously, parsing affective states in response to environmental conditions, refining actions undertaken for self-preservation.

Crucial in this emotional learning network is the amygdala (LeDoux Reference LeDoux1998), which has attracted attention popularly and from IR scholars (Linklater Reference Linklater2011; Crawford Reference Crawford2014, Lebow Reference Lebow, Jacobi and Freyberg-Inan2015) for its role in fear and aggression. The amygdala, located in the temporal lobes, modulates other emotional states accompanying maternal, sexual and eating behaviors, and reinforces rewarding behavior (LeDoux Reference LeDoux2007). It receives non-cognitively mediated external and internal inputs from the thalamus, a relay/gateway to the neocortex, the brain stem, and from the auditory, olfactory, optic, taste, pain and touch systems. The amygdala forms implicit associative memories linking rewarding or unpleasurable emotions with stimuli. It underpins Pavlovian-type conditioning, whereby neutral stimulus is paired with emotionally arousing unconditioned stimulus, and through repetitive pairing induces unconscious reactions to the neutral stimulus. For example, being startled by a moving shadow owes to the amygdala's conditioning. The amygdala also potentiates long-term declarative memory through connections to the hippocampus, a structure responsible for directing the storage of explicit memories in the neocortex. In short, it ensures that emotionally salient experiences are well-remembered (McGaugh Reference McGaugh2004). With projections to the hypothalamus, the amygdala can instigate bodily responses, such as increased heart rate, to emotionally salient stimuli, enhancing survival in life-threatening situations.

Secondary-process learning, which assigns emotional valence to stimuli, allows understanding basic stimulus-response behavior, but is a distance from complex social emotions and motivations of concern in IR. Understanding these requires comprehending tertiary-level processes that precipitate self-awareness. In the neocortex representations of the external world and the self take root. The neocortex allows us to forge conceptions of the self in our environment, and to project ourselves through time. Additionally, cognition diversifies emotions, generating negative emotions including envy, guilt, jealousy, and shame, and positive ones such as awe, hope, humor and pride (Panksepp and Biven Reference Panksepp and Biven2012). Such emotions have gained attention with IR's affective turn.

Extending into the neocortex, the limbic system helps parse emotions necessary in social settings, providing emotional regulation essential for intragroup stability. Key areas are the prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex. The prefrontal cortex provides ‘executive control’, a composite of discrete functions including inhibition, task switching, concept formation, word generation, temporal sequencing, insight, interpersonal perspective taking (theory of mind), and social and real-world executive performance (Miller Reference Miller, Miller and Cummings2007, 7). An important subarea of the prefrontal area, the orbitofrontal cortex, located above the eyes, has substantial connections with the amygdala, allowing it to modulate the latter's arousal. As a gateway between the limbic system and long-term memory, the orbitofrontal cortex regulates unprocessed amygdala reactions (Fuster Reference Fuster2008).

The orbitofrontal cortex is crucial to self-control necessary with a complex social division of labor, self-control integral to the modern nation-state's rise, and to situations involving sensitive decision-making, like in foreign policy. Reconciling associative information from the amygdala with cognitive representations of one's context and of the future, the orbitofrontal cortex aids in fear extinction, dampening anger and controlling appetitive impulses. Individuals with injuries to this area exhibit difficulties engaging in reversal learning, that is, inhibiting rewarding associations with stimuli once reward contingencies are removed (Rolls Reference Rolls2005, 134). Such lesions, while leaving cognitive abilities intact, severely impair emotional processing and social interaction (Damasio et al. Reference Damasio, Grabowski, Frank, Galaburda and Damasio1994). Social decorum requires suppressing frustration and anxiety and checking impulses, a self-control diminished with orbitofrontal damage. Orbitofrontal injuries result in disinhibition, socially inappropriate behavior, violence, verbal abusiveness, lack of initiative, misinterpretation of others' behavior, anger, irritability, and lack of self-concern (Rolls Reference Rolls2005, 135). Cognitively, such individuals may recognize socially appropriate actions, but cannot inhibit their emotions. Noting the forebrain's function, Sasley (Reference Sasley2010) argues that strong ‘affective attachments’ can explain foreign policy decisions that override those considered to be reasoned or rational.

Coronal brain sectionFootnote 13

Through the extended limbic system, cognition not only attenuates emotions, but also arouses them, as occurs with empathy, which has come into increasing focus in international politics (Pedwell Reference Pedwell2014; Head Reference Head2016). Not an emotion itself, affective empathy is cognition activating a range of emotional states. The anterior cingulate cortex and insular cortex (insula) are areas important for affective empathy. Empathy operates both intellectually, where one reasons another's state, and affectively, where one feels another's state (Davis Reference Davis1983). Whereas prefrontal areas are important for generating intellectual empathy, the anterior cingulate and insular cortices appear to generate a simulation of others' emotional experiences (Shamay-Tsoory Reference Shamay-Tsoory, Decety and Ickes2009). In experiments, these two regions activated when individuals saw loved ones experiencing physical pain, areas also activated when individuals themselves experience pain (Singer et al. Reference Singer, Seymour, O'Doherty, Kaube, Dolan and Frith2004). Empathic pain involves affective aspects, but not sensory ones. These regions coactivated when viewing hated persons receiving painful injections, though accompanying this was arousal of a reward-processing part (basal ganglia) of the brain, a phenomenon akin to Schadenfreude (Fox et al. Reference Fox, Sobhani and Aziz-Zadeh2013).

The insula also appears crucial in social emotions, playing a vital role for the maintenance of social groups. Evidence suggests it facilitates crosstalk between cognition and feeling (Damasio and Carvalho Reference Damasio and Carvalho2013). As Damasio relates, individuals with injuries in this area experience feelings of pleasure and pain, but cannot relate these emotions to other aspects of cognition. They show positive social reactivity to loved ones, but no longer recognize them (Damasio Reference Damasio2010). The anterior insula appears important for predicting self and other related feeling states, essential for compassion and interpersonal phenomena such as fairness and cooperation (Lamm and Singer Reference Lamm and Singer2010). The insula enables rumination about our emotions and those of others (Paul et al. Reference Paul, Stanton, Greeson, Smoski and Wang2013).

Mediated by the limbic system, basic consciousness is transmuted into complex forms of emotional expression animating the social relations of concern to IR. Rather than cortical regions generating consciousness, they modulate and refine it. With brainstem regions, they form a nested hierarchy, which, Northoff (Reference Northoff2011) explains, differs from non-nested hierarchies with segregated levels and top-down control. In this nested hierarchy, affects from brainstem regions resurface in higher-level mental processes. Emotions are energetic forces powering higher conscious states. Ascending the hierarchy, there is increasing complexity as basic emotions forge into social emotions. RAGE becomes anger and resentment once objects for offending stimuli are cognitively formed (introjected). PANIC may become shame and guilt, with anxiety about the potential loss of or separation from an attachment arousing this emotion within the neocortex (Wright and Panksepp Reference Wright and Panksepp2011). Basic affects give rise to potentially hundreds of composite emotions (Panksepp and Biven Reference Panksepp and Biven2012, xi).

This nested hierarchy's formation engenders personal development, the neurobiological correlate of subjectification that constructivists and poststructuralists seek to illuminate. Myelination, a process whereby fatty sheath coats nerve fibers, allowing them to efficiently transmit signals to other cells, corresponds to the development of higher-level emotions and their control. There are stages of brain development, with myelination beginning and ending later in the neocortex. Imaging studies suggest that in humans, particularly in the prefrontal lobe, it does not reach completion before the third decade of life (Fuster Reference Fuster2008). From infancy until late childhood, myelination occurs in the amygdala, giving greater influence to secondary-level emotional processes in early adolescence (de Haan Reference de Haan, Calder, Rhodes, Johnson and Haxby2011). Only with the subsequent development of efficient inhibitory projections from prefrontal areas does effective emotional regulation of secondary processes arise, regulation essential for negotiating the social world. We might think of a child's increasing ability to control its temper. Importantly, environmental factors influence the limbic system's development, with exposure to environmental stressors correlating with inhibitory control deficits (Hart and Rubia Reference Hart and Rubia2012).

The evolutionary development of this nested hierarchy, though conferring survival advantages, complicates views of motivation and confounds instrumental-utilitarian psychologies premising certain IR theories. Consciousness, operating on the basis of rewarding and unpleasurable emotional states, Solms and Turnbull (Reference Solms and Turnbull2002) suggest, provides a way of monitoring the delicate economy of the body's internal milieu. Secondary emotional processes further enhance survival by linking stimuli with rewarding or unpleasurable states through associative memory. These processes are reactive and largely hedonic, helping extricate ourselves from threatening situations and promoting survival-enhancing behavior. The tertiary level, though, gives rise to self-referential processes in which emotional states are regulated and modulated for ends that belie rational-choice theories of international politics.

Tertiary processes, though self-referential, contradict theories in IR that posit actors driven by material self-interest or self-aggrandizement. These processes, intermeshing cognition and emotion, Solms (Reference Solms2013) argues, create ‘prediction-error coding’ that works – in the long run – to avert and minimize affective consciousness. Our cognitive constructions, coded in the non-static, plastic columns of the neocortex,Footnote 14 are introjections of external objects, as well as the object of the self. Effective introjections facilitate automaticity and obviate conscious processing, the need to feel our way through situations (Solms Reference Solms2013, 14). Arousal of tertiary-level emotions guides behavior toward certain objects and assigns emotional valency to introjected objects, minimizing future prediction errors and fostering biologically satisfactory conditions. In surprising situations, affective arousal ‘emotionally tags’ memory (Richter-Levin and Akirav Reference Richter-Levin and Akirav2003), which enhances synaptic plasticity in certain brain regions, and refines representations.

Though developing reliable predictive coding, mastering situations by forming cortical representations, can confer pleasure, this is instrumental to the goal of eliminating the need to consciously deal with such situations. Consider the pleasure of learning new tasks, which later are performed unconsciously. Evidence suggests that when learning new tasks, we receive positive feedback with the release of dopamine, a multipurpose neurotransmitter associated with neural reward centers.Footnote 15 With increasing competence, tasks occur independently of this learning/reward mechanism (Ashby et al. Reference Ashby, Turner and Horvitz2010). Declarative consciousness is avoided, and procedural mental processes occur without reflexive awareness (Solms Reference Solms2013).

Automatization has significance for understanding social order, and thus relevance for IR. Automatization occurs not only with the formation of behaviors, but, some studies suggest, with higher-order capacities such as social cognition. Observing another's actions can activate a network of brain regions as if we had performed the actions ourselves. This network, the mirror neuron system, appears to provide relatively automatic behavior identification, as opposed to mentalizing the reasons for others' actions (Iacoboni Reference Iacoboni and Pineda2009, Spunt and Lieberman Reference Spunt and Lieberman2013). In contrast, empathizing with another, mentalizing their emotional state, appears to impose a cognitive load (Rameson et al. Reference Rameson, Morelli and Lieberman2011). Holmes (Reference Holmes2013) explains that mirror neurons are key in face-to-face diplomacy, allowing the simulation of others' intentions. This automatic behavior identification lends coherence to shared social objects, and provides a neurological basis for the reification of constructed social relations, as occurs in IR. This automatization, though, complicates efforts at conflict resolution in international politics, making empathy with outside groups difficult. Automatization is promoted by particular socio-psychological infrastructures, which Head (Reference Head2016) argues perpetuate shared narratives, memories, emotions, attitudes, and beliefs that make empathic encounters with others costly.

Research by Solms and others on the neocortex's role in dampening affective consciousness through modeling the self and the external world illuminates neurological drivers of identity formation, which is relevant to post-positivist IR research. Friston (Reference Friston2005) argues the brain attempts to minimize free energy, to minimize entropy. It has evolved to represent or infer the causes of changes in its sensory inputs. Synaptic plasticity, the processes of creating new synaptic connections and pruning superfluous ones, helps minimize future disturbances. The brain generates hierarchical models that enable it ‘to construct prior expectations in a dynamic and context-sensitive fashion’ (Friston Reference Friston2005, 815). In particular, the discovery of the ‘default mode network’ of brain function (Raichle et al. Reference Raichle, MacLeod, Snyder, Powers, Gusnard and Shulman2001) gives further evidence of the brain's counter-entropic function. This default mode constitutes baseline activity transpiring when the brain is not engaged in goal-directed behavior, what some theorize as self-referential processing. Buckner et al. speculate the default mode allows ‘flexible mental explorations – simulations – that provide a way to prepare for upcoming, self-relevant events before they happen’ (Reference Buckner, Andrews-Hanna and Schacter2008, 30). Northoff (Reference Northoff2012) explains that this intrinsic activity, drawing roughly 80% of the brain's energy needs, creates a ‘spatial-temporal structure’. Weaving together neuronal, internal and external stimuli, in default mode the brain refines a virtual synthetic structure, allowing it to extend and link different points in time and space. It creates, Northoff suggests, a template for future neural processing.

Arguably, this counter-entropic neural predisposition is an intrinsic psychodynamic force, one that belies fixed conceptions of rationality in IR. Solms, Friston, and Northoff each propose a notion of the default mode as constitutive of the ego. In forming objects of the external world, we also constitute objects of our selves. The self-object is constantly undergoing refinement in response to changing conditions. This self-referential processing is done, concurring with Solms' conception of mental life, to minimize emotional consciousness and facilitate automaticity. We confront the challenges of social life through prediction-error coding, constituting objects of others in relation to our evolving self-object. These object relations enable us to efficiently confront future contingencies. This drive for psychological repose, though, does not square with utility-maximizing conceptions of rationality.

This counter-entropic neural predisposition challenges a tendency in IR to treat emotion as a disturbing influence, an assumption that misapprehends the relationship between emotions and rationality. Rather than emotion being external to and thwarting rationality, more properly, strong affective states are indicative of rationality's limitations in channeling emotion and preventing situations that aggravate emotional disturbance.

For IR and social science, recognizing our constructed object relations, and modifications to our objects, as means of regulating emotions adds a new perspective on agency. In situations of anger, anxiety, or fear, in the plastic neocortex, internalized objects that constitute prediction-error coding are reformulated to re-establish emotional quiescence. Solms suggests that the cortical apparatus aspires to a zombie-like state of Nirvana, but, given life's surprises, is never entirely successful (Reference Solms2013, 14). In the case of anger, though, the neocortex may help rationalize and forgive transgressions against our internal coherence, but it does not forget. Offending objects are reassessed, refining our prediction-error coding. In the case of anxiety, a fear of dispossession of cherished objects energizes new synaptic connections, forcing a change of one's self-conception.

The breakdown of object relations helps explain the outbreak of emotions that commonly occurs in international politics. As Eznack (Reference Eznack2011) claims, where there are close alliances between states, the transgression of relational norms precipitates passionate negative reactions. She argues this occurred in the 1956 Suez crisis, with emotion unleashed in the clash between the United States and its allies Britain and France. Such crises give indication of the role of introjected objects in regulating affect, and of the costliness of adjusting these objects.

Though our understanding of the hierarchy of emotional processing remains limited, it challenges implicit psychological ontologies within IR. Emotions and the need for their regulation, as suggested by the counter-entropic predisposition, give pause to reconsider instrumental motivations posited to drive actors in international politics. These motivations, though, are historically and socially conditioned responses to the drive to extinguish emotional consciousness.

Implications of affective neuroscience for IR theory

Having explored affective neuroscientific views on basic emotions, as well as the neuropsychology of higher-level emotions, this section outlines key implications for IR theory. First, these subfields open paths toward deep theorizing in IR. Deep theorizing, as Berenskötter (Reference Berenskötter2017) explains, develops a picture of socio-political (inter)action and order by reading how basic motivations and ontologies of political actors manifest in specific loci of social space and time. Aided by affective neuroscience, deep theorizing entails comprehending how neural predispositions are mediated in particular social contexts. Doing so allows us to understand the situatedness of motivations and to interrogate assumptions about human nature latent within contemporary IR (Freyberg-Inan Reference Freyberg-Inan2004; Schuett Reference Schuett2010). Extending ontology to the neural level destabilizes folk psychologies implicit in conceptualizing behavior in IR.

Second, the reading of neuro- and psychodynamics here invites reassessment of the social regulation of emotions, particularly as observed in institutions. As argued here, a key role of all social institutions, and determinant of their longevity, is their ability to regulate social emotions. This is especially relevant in understanding the state, its formation and evolution. Though, as mentioned earlier, others have proposed an emotional regulatory role of institutions and cultures (Crawford Reference Crawford2014; Mercer Reference Mercer2014a), grasping the underlying neural predispositions offers further insight into the dynamic and directionality of this regulation.

And third, the section discusses how productive rapprochement can be made between affective neuroscience and critical approaches to IR. Approaches such as constructivism and poststructuralism, which generally avoid engagement with natural science, can incorporate insights from neuroscience about emotions without neuro-reductionism. For both, the incorporation of the affective dynamics of the brain counters a problematic blank-slate conception of the pre-social self.

The previously outlined counter-entropic neural predisposition serves not merely as another critique of the ‘baseline rationality’ underpinning much of IR theory, but provides a novel perspective of motivation. This predisposition furnishes a distinctive view that resists fixed notions of human nature and socially deterministic perspectives that elide the body. It establishes a position regarding neural substrates that contests mechanical, physicalist interpretations of behavior, as well as social constructivist views that conflate the self with social identity (Blackman Reference Blackman2008). As advanced here, the counter-entropic predisposition animates a drive toward psychological repose, toward self-continuity and self-coherence. It is a motivating force that can seem counter-intuitive given the emotional salience of international politics.

Other approaches to emotions in IR lack a conception of the counter-entropic drive either because they adopt a more cognitivist position on emotions,Footnote 16 or because of their focus on discrete emotions. Without the premise of basic affects, emotions become externalized social objects, and thus motivation requires an alternative explanation. Further, the counter-entropic predisposition cannot be conceived without an overarching conception of the neurodynamics of affect, captured by the nested hierarchy of basic, secondary, and tertiary emotions.

The conception of this counter-entropic neural predisposition engenders a defensive understanding of selfhood. Rather than producing truth seekers in some platonic quest for knowledge, higher cortical processes, in aggregate, aim at limiting consciousness through increasing automaticity. Thus, we constitute representations of the world with the aim of attaining emotional quiescence, not perfecting knowledge. The self is not an essence to be uncovered, but an amalgam of the physical body and a continuously evolving constellation of introjected representations of the self (identities), others, and the world. The self is a composite in which we continuously and unconsciously aim to minimize inconsistencies.

Evidence of the counter-entropic predisposition is arguably witnessed in individuals having undergone so-called split-brain surgery. These individuals, due to intractable epilepsy, have had an operation severing portions of the nerve fiber bundle, the corpus callosum, which connects the brain's hemispheres. The operation extinguishes the relay of sensory information, such as auditory and visual information, between the hemispheres. Techniques to isolate visual input to each hemisphere produce disjunctions in how split-brain individuals understand their own experiences and behaviors. In experiments (Gazzaniga Reference Gazzaniga1995) that isolated visual input to the right hemisphere, when subjects were asked to verbally identify objects shown to them, they could not do so. This is because the regionFootnote 17 responsible for speech production is in the left hemisphere. Asked, though, to point out the objects, split-brain individuals could do so with their left hand, which is controlled by the right hemisphere. Subsequently, asked why they pointed to these objects, subjects would provide seemingly plausible explanations that were confabulations.

Arguably, what transpires with split-brain patients is not ‘lying’, but an intrinsic neural tendency to manufacture a coherent and unified conception of the self. Hirstein (Reference Hirstein2005) suggests that from a neuro-evolutionary point of view, confabulation and self-deception may confer survival advantages. Rather than acknowledge shortcomings in our models and belief systems, unconsciously we disregard their flaws until they become overwhelming. Fitting with Solms' neuropsychology, it appears we overlook contradictions in our worldviews to avoid a flood of emotions that would result from being ‘truthful’ with ourselves.

Understanding this intrinsic tendency is consequential, as it suggests notions about motivation within IR are the result of second-order conditioning. This tendency does not manifest in universal modes of behavior. For example, taking explicit and implicit assumptions in classical and post-classical realism about fear and the survival instincts that fuel a desire for power (Schuett Reference Schuett2010), knowledge of the counter-entropic predisposition suggests this is not innate. Though FEAR is identified as a basic emotion in affective neuroscience, its objects are frequently socialized.

Tracing the influences on realism's assumptions about human nature, namely Hobbes' notion of fear, it can be interpreted as a historically particular projection and displacement of emotion. Projection is a psychological phenomenon where one's own emotions and feelings are ascribed to others, and displacement the redirection of emotions from the objects that arouse them to other, proxy objects. Hobbes, who himself claimed he was born the twin of fear (Reference Hobbes1679), projected his own emotional perspective as a universal one. Though Hobbes explains it as fear of violent death, as Blits suggests, Hobbes' fear did not originate with the state of nature, but was more broadly an ‘indeterminate fear of the unknown’ (Reference Blits1989, 424). Hobbes, thus, arguably displaced this deeper-seated anxiety onto the object of civil order.

Hobbes' conception of the universal fear of death, arising from the unceasing war of all against all, can be interpreted as a means of attenuating existential anxiety. ‘This perpetual fear’, Hobbes writes, ‘always accompanying mankind in the ignorance of causes, as it were in the dark, must needs have for object something’ (cited in Blits Reference Blits1989, 425). Giving concrete expression to this fear within the political realm offered a means of placating it, namely through the submission to the sovereign. The Leviathan, thus, is a strategy for attaining psychological repose and limiting emotional consciousness. So too, emotional quiescence could be attained by reducing complex psychology to a simple, mechanistic one. A mechanistic psychology, which Hobbes held self-evident, obviates establishing mentally taxing and emotionally arousing empathic connections.

There is yet another way in which Hobbes' conception of fear, unconsciously if not consciously, aids in emotional regulation, namely through its performative dimensions. The idea of the state of nature helped normalize the conception of the possessive individual (Macpherson Reference Macpherson1962). Adapting Michel Callon's (Reference Callon and Callon1998) view on the performativity of economic theory, Hobbes' conception of the individual set in motion the enactment of a particular mode of subjectivity. The possessive individual and consequentialist morality established a strategy for emotional regulation and psychological repose.

So too, reassessing liberal conceptions of self-interest and rationality, these can be understood as historically contingent strategies for attaining emotional quiescence. Liberal tenets such as those advocated by John Locke relied on educative apparatuses, particularly within the family, to inculcate a new form of selfhood, contradicting ideas about rationality in the state of nature (Hindess Reference Hindess1996). Baltes writes that Locke's design for education ‘invisibly manipulates the child's desire for esteem, gently correcting his undisciplined mind and teaching him to become his own governor, to internalize the sociable, industrious, and honest practices that ground the possibility of liberal civil society’ (Reference Baltes2013, 175). Mehta (Reference Mehta1992) argues Locke believed not in an innate propensity for order and reason, but a natural condition prone to madness originating from the disorder of the imagination, a disorder to be subdued through liberal institutions.

Like the performative aspects of Hobbesian theory, with the rise of liberal notions of self-interest, we see the enactment and formatting of emotional expression. A hedonic psychology was particularly abetted, Hirschman documents, by Adam Smith's collapsing of diverse human passions into a singular drive for the ‘augmentation of fortune’ (Reference Hirschman1977, 108). During the 17th and 18th centuries, the ‘passions’, including ambition, lust for power, greed, pride, and sexual lust, underwent conflation. For Hobbes and Rousseau, these passions became reduced to two sorts: one a desire for respect and recognition, and the second a desire for things. It was Smith, though, who took what was already ‘simplification on a grand scale’, and amalgamated the passions into the drive of self-interest (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1977, 109). The historical rendering of homo economicus was a means of regulating emotions by cultivating indifference toward the plight of others.

Though motivations underpinning classical theories of behavior, and which often remain latent in approaches to IR, have been historicized by other scholars, they have not elucidated their role in emotional regulation. Understanding the counter-entropic neural predisposition, the tendency to create conditions for automaticity to stave off emotional arousal, helps to reinterpret theory. It is not only that theories neglect emotion in their analyses, but, through performativity, are implicated in the social regulation of emotions.

Affective neuroscience and depth neuropsychology not only offer reinterpretations of motivation, but cast new light on social institutions' role in regulating emotions. Institutions, by fostering stable patterns of behavior, contribute to satisfying the drive toward emotional quiescence. Adopting views of pragmatist Charles Peirce (Reference Peirce1877), institutions are a method of fixing belief, or, as he termed, a method of tenacity. Institutions for Peirce worked against conflicting individual impulses, focusing the attentions of people, reiterating beliefs perpetually and shutting out contrary ideas.

Thus, institutions help quell emotionally arousing situations of doubt. ‘Doubt’, Peirce writes, ‘is an uneasy and dissatisfied state from which we struggle to free ourselves and pass into the state of belief’. He adds, ‘the latter is a calm and satisfactory state which we do not wish to avoid, or to change to a belief in anything else’ (Peirce Reference Peirce1877, 5). Not dissimilar to the confabulations of split-brain patients, institutions help to constitute and maintain beliefs that stave off the need to reconsider ourselves and worldviews.

Importantly for IR, the state, as an amalgam of institutions, performs a vital role in regulating the emotional economies of its constituents. Emotional economies are understood as systems constituted by patterned exchanges of emotional display and socialized modes of emotional self-restraint. In these systems ‘people give and withhold emotional resources, form social bonds and divisions, negotiate microhierarchical arrangements, and derive identity and self-worth’ (Clark Reference Clark, Manstead, Frijda and Fischer2004, 406). As Norbert Elias (Reference Elias1978) argued, accompanying the centripetal forces of the emerging nation-state was more regulated emotional economies. What he termed the ‘civilizing process’ entailed the need to suppress certain emotional expressions, such as anger, fear, and pleasure, while accentuating others like disgust. With the rise of the modern nation-state and the intensification of social interdependence, emotional self-containment and, in certain instances, heightened emotional responses, like repugnance, were essential in normalizing new behaviors.

Though the functioning of state institutions is often discordant, they work toward synchronizing emotion, channeling it during periods of extreme arousal, and eliciting behavior conducive to long-term social stability. State practices and rituals are not simply geared toward down-regulating emotions, for they frequently arouse them to maintain investments in shared symbols, without which the rhythms of social reproduction would break down. State practices, to adapt sociologist Randall Collins' (Reference Collins2004) theorization of interaction rituals, incite affect for the purposes of generating mutual-focus and the emotional entrainment of social groups. Though ostensibly contradicting the counter-entropic neural predisposition in the short run, these state rituals regularize emotional rhythms in society, limiting affective consciousness over the long run. State ceremonies and rituals, from the celebration of independence and memorial days, to state funerals and inaugurations, provide emotionally-charged events that renew attachments to symbols, fostering shared identity.

Although there are instances when institutions are formed with strategic aims to regulate emotions (Maor and Gross Reference Maor and Gross2015), often regulation occurs in unconscious and unplanned ways. Notably, Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1977) argues that market society was an institutional strategy for channeling destructive passions into ‘innocuous avarice’, but the strategy went awry. Institutions often imperfectly regulate emotions and provide coherence to their constituents. The longevity of institutions relies on their continued ability to furnish a modicum of emotional attenuation. In line with evolutionary institutionalism, to the extent that institutions and their attendant rituals deliver emotional quiescence, they are reproduced. When they insufficiently do so, and emotional arousal becomes unmanageable, this indicates potential moments for radical change. Crisis can precipitate the clamor for new institutions that promise self-foreclosure and emotional quiescence. Exemplifying this, as briefly discussed in the final section, is the phenomenon of populism, which itself offers a social form of confabulation.

Understanding the emotional dynamic of the state, drawn from insights from neuroscience, moves us away from timeless geopolitical logics deriving from second-order conceptions of human nature. We can reconceptualize the state as a historically-specific affective technology. More than offering a fix for conventionally understood security needs, through their symbolic functions and historical narratives, states play a crucial role in quelling disturbing emotions. They provide the basis on which their constituents can derive identity and maintain an element of coherence. The significance of shared national symbols in maintaining social life is better appreciated by understanding their role in coordinating group and individual identities in ways that placate the drive for emotional quiescence (Linklater Reference Linklater2019).

Though it exceeds this analysis's scope to formulate a fuller historical sociology of emotions and the state, affective neuroscience and depth neuropsychology imply a deeper motivation undergirding the development of IR. Despite proliferating emotions research in IR, its focus on discrete emotions or the simple recognition that ‘emotions matter’ lacks comprehension of the unifying dynamic offered by exploring the complex relationship of emotion and cognition. Comprehending this neural predisposition can further the theorization of subjectivity and agency in IR, especially in constructivist and poststructuralist approaches, which eschew engagement with the body.

For constructivist approaches, there are important ways in which affective neuroscience and neuropsychology can advance its theorization of IR. First, they address a problematic conception of the human mind inherent in conventional constructivism. As McDermott and Lopez (Reference McDermott, Lopez, Shannon and Kowert2012) argue, constructivism implicitly harbors a blank-slate model of cognition not dissimilar to behaviorism. Identities and behaviors are acquired through processes of learning and reinforcement. Though social interaction complicates this process with mutually constitutive behaviors and identities, this does not, ‘in any substantive way’, alter the presumption of tabula-rasa actors responding to environmental stimuli via reinforcement (McDermott and Lopez Reference McDermott, Lopez, Shannon and Kowert2012, 205).

The conception of the defensive, counter-entropic predisposed mind, which attempts to minimize emotional arousal, allows us to discern the impetus of social construction. It helps in understanding the limits of social conditioning by recognizing a certain intractability of the body. It brings to light that all social constructions unconsciously, if not consciously, are implicated in emotional regulation.

From a constructivist perspective, we arguably see the functioning of the counter-entropic predisposition in what Hopf (Reference Hopf2010) refers to as the logic of habit. By focusing consciously on apprehended identities and contested norms, Hopf suggests, we lose sight of habitual routines that give stability to the patterns of cooperation and conflict (Reference Hopf2010, 540). We might think of habit as the dark matter of global social order, that which is unseen, but which plays a crucial stabilizing role. Hopf looks to cognitive neuroscience to explain the prevalence of habit, arguing the so-called ‘automatic system’ of the brain maintains habits to minimize the need for reflection and its attendant cognitive load (Reference Hopf2010, 542). This explanation is but a few steps from the argument of this analysis, which is that the logic of habit serves an inherent tendency to attenuate emotional consciousness. Habits persist provided they furnish emotional attenuation, but are susceptible to disruption and change in moments when emotion rouses conscious reflection.

Poststructuralist IR, which focuses on the discursive construction of subjects, can also benefit from apprehending the brain's affective dynamics, and from a retrieval of the physical body with which discourses interact. Though poststructuralist interventions have brought attention to the management of bodies in IR, particularly drawing on Foucault's biopolitics and his genealogy of state practices (e.g. Foucault Reference Foucault2007), they fail to register the drives emanating from these bodies. In Foucault, the body is treated as a passive entity, ‘acted upon in discursively-constituted institutional settings’ (Lash Reference Lash1984, 3). With this assumption of passivity, it dismisses the agency of the body. Paraphrasing Coole and Frost's work on new materialisms, the body, though, possesses a generativity and resilience with which social actors interact, and its material forms circumscribe, encourage and test discourses (Reference Coole, Frost, Coole and Frost2010, 26). Understanding neural predispositions, of a drive toward psychological repose and a tendency of confabulation, offers insight into subjectification. The reasons why individuals become complicit in oppressive forms of self-regulation and self-cultivation is that they afford, albeit in disfigured forms of subjectivity, a glint of emotional quiescence.

For poststructuralist IR, there are fruitful possibilities from engaging with the body and the neural substratum, without defaulting to essentialism. Despite issues with bodily passivity in Foucault's work, other poststructuralists, albeit less prominent in IR, have taken account of the body in theorizing social order. Deleuze and Guattari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1984), for example, see the body as the source and target of libidinal drives. These drives, which are initially objectless, are mediated through capitalism and produce specific libidinal investments in institutions such as the family and state. Similarly, Lyotard (Reference Lyotard1993) formulates social relations in terms of libidinal economies, through which pre-social drives of the body are shaped and transmuted into desires through culture. Emotions are an ineffaceable aspect of social life, and through dispositifs are channelized and object-desires are constellated.

Despite neglect of the body's agency, there are ways in which the body's affective dynamics can be integrated into Foucault's theorization. Emotional regulation can be seen operating in what Foucault (Reference Foucault, Martin, Gutman and Hutton1988) referred to as technologies of the self, techniques for self-cultivation crucial to the operation of the modern state. These techniques, employed by subjects to refine the operations of their own bodies, minds and souls, can simultaneously be viewed as subserving emotional quiescence. Incorporating neuro- and psychodynamics can address limitations of governmentality studies, which as D'Aoust (Reference D'Aoust2014) argues, treat emotions as instrumental and through which practical rationalities can be enacted. They can rehabilitate the body and its agency, and we can better understand those instances when emotions exceed the capacity of social technologies to deliver psychological repose.

As has been argued, affective neuroscience and depth neuropsychology contribute to the appreciation of the affective body's ineffable presence in IR. They help destabilize questionable psychological ontologies that premise IR theories, both mainstream and critical. So too, they recast our understanding of institutions, particularly the state, in terms of an enduring drive for emotional quiescence.

There is, though, as the concluding section outlines, another potentially valuable agenda to be realized from grasping the neural dimensions of IR, specifically a therapeutically-attuned approach to IR.

Conclusion: toward a therapeutic IR