Introduction

In theory, international humanitarian law and international human rights law provide protection against torture in times of war. The United Nations (UN) 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the 1984 Convention against Torture prohibit the practice at all times and in all places, whether in peace or war, as do the 1949 Geneva Conventions and the Additional Protocols of 1977 in situations of armed conflict. Yet the weight of evidence of illegal detention, forced disappearances and abuses of the enemy to emerge after 9/11 would suggest otherwise.Footnote 1 Disdain for international law is widely displayed by State and non-State armed groups. Indeed, today's dilemmas of how to protect political (or “security”) detainees in situations of extreme violence would have been perfectly recognizable to a post-Second World War generation of humanitarians and human rights activists. The past seems condemned to repeat itself.

It was amidst the violent upheavals of the end of empire and the Cold War that international organizations first developed a basic framework for holding State and non-State armed groups to account for their actions when taking prisoners.Footnote 2 The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) placed itself at the very centre of these developments. Detention visiting – hitherto a fairly marginal activity for the world's leading humanitarian agency – rapidly became a cornerstone of its work.Footnote 3 Nowhere was this growing preoccupation with the problem of protecting detaineesFootnote 4 more evident than apartheid South Africa.Footnote 5 Detainees lack the legal protection of prisoners of war (PoWs) – a term that refers to any person captured while fighting by a belligerent power, and is hence applied only to members of regularly organized armed forces. The ICRC's concern with PoWs was long-standing, dating back to the late nineteenth century. Its subsequent concern with detainees – persons sentenced or detained for their political ideas or ideological beliefs – can be traced back to the interwar years of the twentieth century and was focused initially on Europe. At that time the activity was quite limited, however. Starting in a more modest way with the Hungarian insurrection in 1956, and then on a much larger scale in South Africa from the 1960s, the ICRC rapidly expanded its concern with political detainees. The first visits to prisoners detained by the apartheid State occurred in the wake of the Sharpeville massacre of 1961, a period which saw the political opposition almost destroyed and many of its leaders imprisoned or exiled.Footnote 6 International pressure mounted, ranging from grass-roots activism of citizens, to the actions of States, to regional bodies like the Organization of African Unity, to supranational organizations like the UN, even if such pressure was not continuously or evenly applied and had yet to fully isolate the apartheid regime. As far as Nelson Mandela and other African National Congress (ANC) detainees were concerned, the assumption of the South African authorities was that they would never be released and would eventually die in prison.

More ICRC visits to prisons took place in South Africa than in any other African country, with the exception of Rhodesia-Zimbabwe. Involvement in South Africa raised in its sharpest form the question of what mandate, if any, international organizations possessed to protect those considered by their national governments to be “enemies of State”. While the South African authorities insisted that no such mandate existed, and that there was no right of humanitarian initiative in a situation of collective violence that did not amount to an armed conflict, the perspective of the ANC was very different. Like other African liberation movements, the ANC regarded its liberation war as tantamount to an international armed conflict, and felt fully vindicated with the passage of the first Additional Protocol in 1977. The first Additional Protocol infused the laws of war with the politics of anti-colonialism by redefining international armed conflict to embrace all peoples fighting against “colonial domination”, “alien occupation” and “racist regimes”.Footnote 7

For the ICRC, detention in South Africa was also the beginning of the organization's awareness of psychological torture.Footnote 8 From the outset it was apparent that the ultimate purpose of the apartheid State depriving its political enemies of liberty was to break their morale and to deny them any hope for the future. An elaborate system of humiliation and intimidation was ruthlessly implemented alongside the denial of even the most basic of physical needs. Prison life was organized through the bestowal of privileges and the distribution of punishments.Footnote 9 Isolation and solitary confinement were a favoured and forbidding form of punishment, and Mandela was later to write that “nothing is more dehumanising than the absence of human companionship”.Footnote 10 The disruptive effects of this disciplinary system – individually and cumulatively – were as much on the mind (e.g., depressive symptoms such as sleep difficulties, irritability and anxiety disorders) and personality (e.g., mood disturbances, shattering of confidence and even suicidal tendencies) as they were on the body.Footnote 11 They increased the detainee's sense of vulnerability and reinforced feelings of dislocation and despair. Prisoners fought back, however – for example, by refusing to prepare for inspections or to take part in incentive schemes for good behaviour, or by attacking warders who abused and humiliated them. Striking the right balance between accommodating and fighting the prison system was essential to a detainee's survival. Jailers were at times resolutely defied in order to challenge the regime's jurisdiction, yet detainees also had to learn to adapt to the system in order not to be ground down by it.Footnote 12

Starting in 1964, there were ICRC visits to Robben Island, Victor Verster (and its outstation Bien Donne (juveniles)), Pretoria Local (whites only) and Barbeton (black women) in twenty of the following twenty-six years.Footnote 13 During these visits the ICRC was drawn into an internationalized human rights dispute that severely tested its leadership. A fundamental challenge was to ensure that securing the cooperation of the South African authorities did not become an end in itself. If the terms of access legitimized – or even appeared to legitimize – unlawful deprivation of liberty or arbitrary State behaviour, the ICRC risked being judged complicit by the very people it sought to help. This risk was compounded by the fact that apartheid was unusual if not unique in the extent to which it challenged the existing norms around armed conflict – traditional definitions of humanitarian action were destabilized by the racialized State of South Africa, in just the same way as conceptions of human rights were reframed in a quest to combat the injustices of Afrikaner rule.

Apartheid therefore had the potential to set humanitarian and human rights organizations against each other, yet deteriorating racialized violence in Southern Africa at the same time provided a powerful impetus to make common cause. In their efforts to ameliorate the violence of apartheid, a post-war generation of humanitarians and human rights activists came together to call upon the moral force and universal quality of the concepts of “human dignity” and “humanitarian protection”.Footnote 14 The ICRC, Amnesty International and the UN Commission for Human Rights were particularly prominent in the context of apartheid South Africa and the protection of detainees. For reasons of space, they form the focus of this article. There were, however, many other organizations involved, including the International Aid and Defence League, the Africa Bureau, the International League for Human Rights and the International Commission of Jurists, which are examined in greater depth in my forthcoming book. Through their combined if not always coordinated efforts, they sought to extend their mandates into states of public emergency. This is not to deny the fact that under those twin banners, assorted legions marched. It is, however, to argue that there were multiple paths from the UN's Universal Declaration of Human Rights to the international humanitarian and human rights regimes with which we are familiar today. Rather than positing a dramatic turn from humanitarian concerns to individual human rights after the end of the Second World War, I assert that there was in fact another path – that of humanitarian rights − forged by the many and varied groups that grappled in the post-war era with the problem of political detention.Footnote 15

The first recorded ICRC interview with Nelson Mandela

Although he was first visited on 20 April 1964 by the ICRC's delegate-general in Africa, Georg Hoffmann, the first ever recorded interview with Nelson Mandela by an ICRC delegate occurred on 8 April 1967.Footnote 16 (In 1965 the ICRC had requested a further round of visits, but it was not until 1 February 1967 that the South African authorities responded affirmatively to its repeated requests.) The delegate in question was the energetic, fiery Godfrey Senn. His interview with Mandela encapsulates the experiences of the many insurgent, guerrilla and liberation movement fighters detained during decolonization. Mandela later remembered Senn in his memoir, Long Walk to Freedom.Footnote 17 He noted the improvements that had followed Senn's visit, yet lamented that Senn was not in any sense “a progressive fellow”. In front of the head of the prison, Senn had dared to suggest that “mealies” − a sour-milk porridge made from course maize flour − were better for the teeth than the bread which Mandela had requested, a remark that has proved a source of embarrassment for the ICRC ever since. Senn's Rhodesian background likely aroused suspicion, though it should be said that several former ANC, Pan-African Congress (PAC) and (Namibian) South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO) prisoners on Robben Island had much more positive recollections of the man.Footnote 18 Moreover, the consequences, at this juncture, of a more robust engagement with the South African authorities can only be speculated upon. The risks of expulsion were real, and weighed heavily on the minds of Senn's superiors in Geneva.

Senn was nothing if not a complex character.Footnote 19 Formerly the director of a juvenile prison in a Baltic State, he later emigrated to Southern Rhodesia, where he was appointed the ICRC's delegate for Southeast Africa in 1941; he subsequently developed relations with African nationalists such as Hastings Banda and Kenneth Kaunda while becoming increasingly critical of the attitudes and actions of the Rhodesian branch of the British Red Cross. He was short and plump in appearance, a declared atheist, and lived in a religious community in the town of Rusape in the northeast of the colony, reputedly in a room with a coffin leaning against the wall, which he used as a cupboard for his numerous whisky bottles. A fearless man, impatient with bureaucrats, he was thoroughly opposed to apartheid. He also had a reputation for breaking administrative bottlenecks. That reputation was established during the civil war that broke out in the Congo after the Belgian colonists withdrew in 1960 and left a major humanitarian crisis in their wake. Senn reacted rapidly to mobilize a massive medical relief operation under the auspices of the Red Cross and World Health Organization.Footnote 20

By the time Senn arrived in South Africa, however, he was an older and frailer man. He certainly defended ANC prisoners robustly, and often criticized his ICRC superiors in Geneva for not being sufficiently assertive or outspoken, especially with regard to the abuse of prisoners.Footnote 21 Yet Senn was equally a man of his time. After years spent among East African's settlers, he became, as Mandela − with typical restraint − observed, acclimatized to the very racism of which he was a critic.Footnote 22 Senn's racially paternalistic language meant that he did not quite look upon Africans as he would white people and that he ascribed different characteristics to them. To quote another ICRC delegate who spent several years in South Africa at this time, he “defended Africans, but as Africans”.

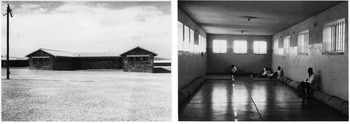

Figures 1 and 2. “H” block, Robben Island, 10 April 1967. ICRC Archives, Geneva. Photograph by Godfrey Cassian Senn, © ICRC.

Senn visited Robben Island for six days from 5 to 10 April 1967, at a time when the ICRC's standard practices and procedures for detention visiting – regular and repeated visits without witnesses present and access to all facilities − had yet to crystallize.Footnote 23 There were further visits in May, August, September and October that year, the autumn visits including the medical delegate Simon Burkhardt. Senn's presence in South Africa was recorded as being so “hush-hush” that he did not contact the local office of the South African Red Cross. The ICRC deliberately did not ask for access to detainees still on trial. Indeed, although the ICRC later changed its policy and attempted to visit non-convicted prisoners, at no time after 1964 did the organization ever gain access to any interrogation centres, such as the notorious “Kompol” building in Pretoria where political prisoners were treated brutally and sadistically by officers of the South African Special Branch.Footnote 24

Days of mental and physical torture (including electric shocks and simulated drowning), regular beatings, verbal intimidation and sleep deprivation were designed to extract information and confessions from those recently captured. All of this occurred well before prisoners were transferred to Robben Island and well out of sight of any international organization. The ICRC did, however, learn of detainees’ complaints of torture after their arrest, remarking as early as 1967 that the “number and consistency” of such complaints “would seem to justify enquiries and if need be the introduction of a system of control over police interrogation”.Footnote 25 For their part, the South African authorities strove to keep any reference to maltreatment during interrogation out of the ICRC reports on the spurious grounds that the police belonged to another ministry to that of the prison administration, to which separate reports should therefore be submitted.Footnote 26

When Senn visited Robben Island there were 996 prisoners, 822 of whom were convicted “for crimes against the security of the State” – to all intents and purposes, political detainees. ANC members were separated in single cells in “D Section” and kept apart from the rest. Senn's report to Geneva records a walk through the hospital, single cells, kitchen and recreation hall on the Friday morning, followed by “a long talk with Mr Mandela” on the Saturday morning, without witnesses present. This conversation focused mainly on medical complaints. There was a further talk with Mandela on the Sunday afternoon, with the Prison Department's liaison and information officer present, which focused on the inadequacy of food rations. On the Monday morning, Senn met with the prison doctor for a second time. He later inspected three separate work parties at the stone quarry, the limestone quarry and the seaweed processing plant – hard labour in the quarries on Robben Island was not brought to an end until 1977.

Figure 3. Prisoners drying seaweed, Robben Island, 10 April 1967. ICRC Archives, Geneva. Photograph by Godfrey Cassian Senn, © ICRC.

The 1960s was a particularly punishing decade for Robben Island detainees. “We live in a legal vacuum without the slightest hope of real justice”, one detainee remarked.Footnote 27 Prisoners were deprived of all news and locked in their cells over weekends, and there was no pretence at rehabilitation. On numerous occasions ICRC delegates expressed their concerns about the impact of the lack of any form of rehabilitation on the morale and mental health of detainees. Several cases of assault by prison warders were under investigation – State violence was not limited to interrogation. Family visits were scarce, and there were considerable delays in the delivery of very limited incoming and outgoing mail, much of which was in any case redacted by the authorities. Detainees regarded this as a particularly inhumane aspect of the prison system.Footnote 28 (Mandela wrote of his daughter, Zindzi, “She was a daughter who knew her father from old photographs rather than memory.”Footnote 29 ) Above all, as Mandela recorded in his autobiography, work regimes were known to have been extremely strenuous, contradicting the Prison Department's own stated policy.Footnote 30 Quarrying lime or stone, or dragging seaweed from beaches, for seven hours a day, five days a week, had the intended effect of not only sapping the physical strength of prisoners but also beginning to break their morale.

Figure 4. Stone quarry, Robben Island, 10 April 1967. ICRC Archives, Geneva. Photograph by Godfrey Cassian Senn, © ICRC.

When Senn arrived on Robben Island, Mandela and his ANC colleagues had been working in the quarries or seaweed processing plant since January 1965. They were all complaining of regular collective punishments for not meeting work quotas, and of warders charging upon them with dogs and batons. They noted how the doctor refused to treat them. Mandela's tear glands were permanently damaged after years of smashing rocks at the quarry, a result of the dazzling glare from the stone and the lack of proper eye protection, and he later recalled how the sun's rays, reflected into his eyes by the lime itself, had been a greater problem than the heat.Footnote 31 Medical complaints of ANC prisoners included work- and stress-related illnesses such as hernias and hypertension, as well as cases of injury not attended to by the prison medical officer, the absence of proper medical histories, poor screening for tuberculosis, and limited dental care.Footnote 32 There had been seven recorded deaths on Robben Island since May 1964, in addition to several cases of severe depression. Diet was also a major issue of contention – as no food was grown on the island, and all produce had to be shipped in, rations were highly monotonous. There were no vegetables or fresh fruit in the diet, and prisoners often went hungry and suffered from vitamin deficiency (especially skin complaints) and severe constipation. The diet, moreover, was racially discriminatory. Different amounts and types of food were given to whites, coloureds and blacks.Footnote 33

Figure 5. Stone quarry, Robben Island, 10 April 1967. ICRC Archives, Geneva. Photograph by Godfrey Cassian Senn, © ICRC.

Political detention during decolonization: A brief history

Let us step back for a moment and consider the broader context of protecting detainees during decolonization. Nowhere was the challenge of containing the violence of the end of empire more acute than with regard to the introduction of sweeping emergency security laws and the widespread resort to political detention.Footnote 34 Detention was a method of choice for an apartheid regime confronted by nationalist opposition.Footnote 35 Detainees were to be cut off from the outside world by making the world forget them, and them forget the world.Footnote 36 The need to provide better protection for detainees therefore emerged as one of the biggest challenges facing humanitarians and human rights activists during the post-war era.

The basic model for detention visits had of course existed for many years in the form of ICRC visits to PoWs, the modalities for which were laid down in the Third Geneva Convention of 1949. Detention work evolved by analogy to PoW work, which had defined some of the basic visiting criteria, including repeated visits and talks without witnesses.Footnote 37 Nevertheless, after 1945 the rapid growth of the number of those detained and the number of detaining powers was paralleled by the equally rapid growth of humanitarian and human rights activity aimed at ascertaining the facts regarding detention, monitoring the trials of those charged with offences against the State, improving the treatment of those deprived of their liberty, and bringing relief to the families they left behind. For the ICRC in particular, detention demanded a rapid and far-reaching growth in post-war programming − at a time of significant budgetary constraints.

Three successive decades of intensive lobbying on behalf of detainees by the ICRC and Amnesty International, the International Commission of Jurists and an array of other human rights groups occurred at the very moment when wars of nationalist resistance were raging and, subsequently, post-colonial States were struggling with internal security problems of their own. So weak was the legal basis for humanitarian or human rights interventions at this juncture that, in the words of a leading international lawyer, the protection of political detainees threatened to become a “no-man's land in humanitarian action”.Footnote 38 In purely legal terms, the situation in South Africa was considered to be below the level of an armed conflict. Unlike in Algeria, or Kenya, or Rhodesia-Zimbabwe, the ICRC in South Africa did not even try therefore to appeal to Article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions, covering situations of non-international armed conflict, but based the offer of its services on tradition and precedent and the organization's own statutes instead.Footnote 39

Despite the legal limitations, as much as any other organization in the international sphere during the post-war era, the ICRC led the way in holding late-colonial and postcolonial States to account for their treatment of political detainees. From the early 1960s to the mid-1970s, the ICRC's delegates visited an estimated 100,000 detainees in over seventy countries – a staggering number, and a massive increase on anything undertaken in the inter-war period. Data from a previously unpublished ICRC memorandum points to the scale of the transformation: from thirty visits to nineteen countries during the 1950s, to 106 visits to forty countries during the 1960s, to 243 visits to fifty-eight countries during the 1970s.Footnote 40 Previously a subsidiary feature to relief operations (the ICRC even internally questioned whether it possessed the necessary mandate to undertake detention visits), the protection of detainees was now turned into a cornerstone of its work. The ICRC, moreover, intervened in apartheid South Africa and many of Europe's colonies in the face of considerable hostility and resistance from the detaining powers. The strength of the organization's resolve is captured by Jacques Moreillon, delegate-general for Africa, who argued: “A fireman must be close to the fire and those people who are the main concern of ICRC, political detainees, must be within easy reach of our Delegate.”Footnote 41

The ICRC and the challenge of apartheid South Africa

The ICRC's access to political detainees

Detention visiting was an aspect of protection work that brought the ICRC into close communication with Europe's colonial powers and African liberation movements. Indeed, the difficulty for international organizations navigating their way through the transition between colonial and postcolonial regimes is very well illustrated by the experience of the ICRC. Within barely a decade, the organization, alongside a number of human rights groups and churches, had swung from largely avoiding contact with liberation movements to systematically cultivating a dialogue with them. In 1962, the former Swiss army officer and future ICRC president Samuel Gonard headed the organization's first information-gathering mission to Equatorial and Central Africa, visiting British, French and Belgian colonies and ex-colonies.Footnote 42 The ICRC had hitherto only reluctantly involved itself in the affairs of Europe's colonial empires. Gonard's mission was largely prompted by a well-founded fear among his ICRC colleagues that what had been “an essentially European organisation” would not be perceived as sufficiently independent or “free from the prejudices acquired from centuries of colonial domination” to establish itself on the continent after the end of European rule.Footnote 43

Initial interventions were improvised and reactive. The ICRC's delegates in Africa – of which there were forty-two in the late 1960s compared to seventy-four in the Middle EastFootnote 44 – found themselves presented with situations of insurgency and counter-insurgency of a severity and on a scale for which they were ill-prepared.Footnote 45 They received limited formal training for detention visiting, provided as part of a week-long course at the ICRC's Cartigny centre, despite visiting on average between 300 and 400 South African detainees almost every year from 1967. During the 1960s, the ICRC did, however, open up regular contacts with non-State armed groups active across Angola, Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Nyasaland (Malawi), Southwest Africa (Namibia) and South Africa. African nationalist leaders pressed the ICRC and other leading aid agencies for medical relief as well as for cooperation on the visiting of detainees. All of the ICRC's contacts with liberation movements in Southern Africa at this time were direct rather than via governments or the UN. Although the ICRC did not know exactly who in the ANC were members of Umkontho we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation, the ANC's armed wing, co-founded by Mandela), it was assumed that all of the leading detainees on Robben Island were. Hence, in talking to Mandela or Mbeki, the ICRC was aware that it was talking directly to the organization's military wing, though perhaps not in the first visits.

It is worth emphasizing that the ICRC was the only international institution to gain widespread access to political prisoners in apartheid South Africa. The delegates of the international Red Cross also developed a reputation for genuinely seeking to establish what was happening inside of South Africa's prisons and to form “a coherent picture of the situation and circumstances” in which detainees were held.Footnote 46 Privileged access came at a price, however – namely, that the ICRC commented on the conditions but not the causes of detention. Amnesty International's approach differed, though it was arguably complementary. It campaigned for the release of what became known as “prisoners of conscience”, although with the proviso that they had neither advocated nor practised the use of violence.Footnote 47 (A conflict therefore arose in 1964 over whether or not to sponsor Mandela as a prisoner of conscience. Because Mandela maintained that violence was a justifiable last resort, Amnesty decided it could not adopt him as a prisoner of conscience, however prominent in the anti-apartheid struggle he may have been.Footnote 48 ) In the event that Amnesty could not campaign for the release of a prisoner, it limited its concern to the conditions of detention, just like the ICRC. Amnesty's first report on prison conditions in South Africa was published in 1964–65.Footnote 49 Amnesty and the ICRC began corresponding over the protection of detainees in 1963 – the year before the first ICRC visit to Robben Island – partly in relation to a draft international code of conduct for the treatment of persons suspected of presenting a danger to the security of the State, partly in relation to a proposed project for the universal inspection of administrative detention camps. Peter Benenson, the founder of Amnesty International, was the originator of these initiatives, which he presented as ways to strengthen international humanitarian law and guarantee fundamental human rights during periods of transition between colonial rule and independence.Footnote 50

As already noted, the ICRC acknowledged that there was no effective legal basis for detention visiting in internal (or “non-international”) armed conflicts, let alone in situations below this threshold.Footnote 51 Insofar as States were willing to accept and authorize detention visiting, it was largely on the basis of practice and precedent. Declaring the difficulty of gaining access to political detainees in such situations “a growing worry” for all those “who have humanitarian principles at heart”, the ICRC convened three Commissions of Experts in 1953, 1955 and 1962, in order to examine the problem.Footnote 52 These Commissions were followed by a consequential seminar on political detainees that ran from May 1973 until March 1974, and which reflected at length on the experience the ICRC had hitherto acquired in this field.Footnote 53 Even at this stage, there continued to be significant reservations within the ICRC about enlarging detention-related activity. How would the ICRC avoid jeopardizing its relations with States, or alternatively, becoming their instruments? Was it possible for the ICRC to preserve its ideological impartiality when assisting detainees? What were the essential and what were the desirable conditions of visits? These questions were debated at length by participants in the detention seminars, without always arriving at clear answers. The seminars – backed by the Assembly – eventually concluded that when other organizations were not in a position to provide protection to detainees, the ICRC had a moral obligation to do so, even if no satisfactory legal basis existed.

The actions of the apartheid authorities

Throughout the 1960s, the intention of the South African government could not have been clearer. Amidst a welter of race legislation, which included the infamous pass laws, the authorities imposed a highly punitive and coercive detention regime in which repression and cruelty were codified to the last detail. Study facilities were almost non-existent, contact and correspondence with relatives remained scarce (an egregious effect of which was to put many marriages and family relationships under severe strain), and every effort was made to prevent prisoners from gaining access to news of the outside world. The main aims of detention were to isolate and intimidate political prisoners and generate an atmosphere of hopelessness among them. Several measures were taken to this end.

First, the South African authorities refused to distinguish between the so-called “criminals” and the “politicals”. This was not simply to deny political detainees any special status: common-law criminals were also used by warders as informers or as part of criminal gangs to maintain order inside the prison and to harass and assault ANC members.Footnote 54 Second, control was exerted by the granting or denial of privileges. Prisoners on Robben Island were classified into four categories according to the security risk they were judged to represent. Members of the ANC, PAC and SWAPO − so-called “active extremists” − were forbidden newspapers and radios, and were only permitted to write a three-quarter-page letter every six months and to receive one half-hour visit every three months. Third, there was victimization by prison warders. For example, in his interview with Senn, Mandela referred directly to a “persecution campaign” of a particular vindictive warder, van Rensburg, who had a swastika tattooed on the back of his hand.Footnote 55 Fourth, prison authorities sought to mislead and manipulate the ICRC, which they resented for interfering with State security. A tried and tested technique was to improve the conditions of detention immediately prior to a visit. Hence Mandela's wry remark in his first interview with Senn: “[W]e respect the Commissioner of Prisons very much; even before he comes for a visit, the handling of the prisoners by the Staff becomes more ‘human’.”Footnote 56 Senn himself was under few illusions on this score. He later remarked that the fact that prisoners appeared relaxed in the rock quarry was because warders did not dare risk an order to intensify work while an ICRC delegate was present. He also cautioned against any optimism regarding the results of the ICRC's first visits to Robben Island, singling out van Rensburg and his kind – of whom Senn said there were a lot – for whipping up public hysteria against the ICRC.

Figure 6. Stone quarry, Robben Island, 10 April 1967. ICRC Archives, Geneva. Photograph by Godfrey Cassian Senn, © ICRC.

The South African authorities were even more obstructive with regard to the type of detainees that the ICRC was permitted to visit. The ICRC was able to work on behalf of two categories of prisoners: convicted security prisoners who were serving sentences, and later (from 1976) those detained under Section 10 of the Internal Security Amendment Act.Footnote 57 A long-run battle and repeated representations to see those detained under Section 6 of the Terrorism Act of 1967, which supplemented ninety- and 180-day detention orders and allowed for unlimited periods of detention, came to nothing.Footnote 58 The Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs refused access to those detained under the Terrorism Act for the next decade, despite the ICRC president's personal intervention on the issue. Both the South African and Rhodesian authorities rejected any argument in favour of ICRC authorization to visit those who they classified as “captured terrorists” for fear of such detainees thereby qualifying as “combatants” and attaining PoW status.Footnote 59

The major flashpoint, however, was the South African government's selective and politically motivated citation of ICRC reports.Footnote 60 Senn, as already noted, was not the first ICRC delegate to visit Robben Island. An earlier visit in April 1964 by the ICRC's delegate-general for Africa, Georg Hoffmann, erupted in controversy when two years later, on 26 November 1966, the South African government published sections of Hoffmann's report in the local press (as well as publicizing them in the UN) that showed the prison authorities in a good light.Footnote 61 The tone of the Hoffmann report had been very subdued – this was most likely because Hoffmann feared the South African government would otherwise prevent further visits. Not without justification, he was accused of failing to convey the seriousness of the problems.Footnote 62 Yet his reticence was not without cause. Public denunciation ran the risk of losing the very thing the ICRC prized: proximity to the people who were in need of protection. In fact, the ICRC had very nearly been expelled from South Africa precisely at the moment when allegations of “defending and sheltering white supremacy” were surfacing with great fanfare in the UN's General Assembly.Footnote 63 Hence the considerable reluctance on the part of the ICRC to speak out publicly – a reluctance which nonetheless continually exposed the organization to criticism from human rights groups.

The decision of the South African authorities to selectively cite the report was most probably prompted by the UN's Commission on Human Rights (CHR) unprecedented break with its “no power to act doctrine”.Footnote 64 The CHR was formed in 1946 in the wake of the mass atrocities of the Second World War to promote the rights of all of the world's peoples, but it was immediately hamstrung over disagreements on the question of whether and in what ways to enforce the principles it promulgated. The CHR's decision to investigate allegations of torture and ill-treatment in South Africa's prisons broke with its doctrine not to investigate and report on abuses. It was the first time since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) that the UN's human rights machinery had been used to take on a member State in such an openly confrontational manner.Footnote 65

A UN Working Group of Experts, which the ICRC felt had set out to make as much trouble as possible for the South African government, was charged explicitly with the task of investigating the violation of human rights. It was (unsurprisingly) forbidden to enter the country, the apartheid government arguing that the UN's decision to investigate was a “flagrant breach of its internal affairs”;Footnote 66 hence the Working Group had no direct access to detainees. Instead the UN had to rely on interviews outside of the country with those already released from detention. The Working Group wrote to the ICRC on 5 June 1967 requesting “certain information”, and the ICRC's annual report for that year records that “in so far as it was able”, it had attempted to supply this information.Footnote 67

Insisting that his government had nothing to hide, South Africa's ambassador to the UN adduced the ICRC's visits – and its supposedly free access to any prison – as evidence in support of his contention. The ambassador's assertion relied on the erroneous claim that ICRC delegates had been allowed “unrestricted inspection”. He went on to insist that the ICRC was “by reason of its long tradition of objectivity” the proper body to establish the truth of the situation.Footnote 68 The Working Group, meanwhile, attacked the ICRC for its hesitation in speaking out against abuses, for delays in despatching its reports, and for “playing the game of Pretoria”. What particularly smarted in Geneva was the UN General Assembly's comparison – or, in the ICRC's words, the “slanderous accusations” – of failure to act in South Africa and the ICRC's earlier failure to condemn the Nazi concentration camps. These accusations made by UN delegates from Nigeria and the USSR provoked an organization usually keen to avoid the spotlight of publicity to vigorously defend itself on the public stage.

The ICRC insisted that the policy of confidentiality protected its freedom to privately criticize a detaining power. Yet the force of this argument was undermined by the highly selective citation of the ICRC's reports by the South African authorities. By the ICRC's own admission, detainee confidence in its neutrality and impartiality was seriously damaged by the Hoffmann incident.Footnote 69 If nothing else, this turn of events exposed the emerging stresses and strains between humanitarian organizations and human rights groups as they tried to put in place a more robust international framework for the protection of political detainees. The ICRC's president, Samuel Gonard, felt strongly enough to write to the UN secretary-general, U Thant, and to Marc Schreiber, director of the UN's Division of Human Rights, to say that he had been “deeply perturbed” by the allegations made in the precincts of the UN, which were “so obviously contrary to the truth”.Footnote 70 In a highly unusual move, he then pressed for his letter of rebuttal to be circulated among the members of the UN's Economic and Social Committee (ECOSOC).Footnote 71

A decade later, Moreillon's successor as delegate-general for Africa, Frank Schmidt, and Gonard's successor as president, Alexandre Hay, were still grappling with essentially the same problem – namely, how retain detainee confidence and trust in the ICRC, and enlarge the scope of the organization's prison visits, while not falling foul of the South African authorities. Hay had visited South Africa in 1977, the first ever ICRC president to do so.Footnote 72 His primary purpose had been to gain access to non-convicted detainees held under the Terrorism Act. (Subsequently, in 1987, still lacking access to non-convicted detainees under interrogation and considering that there was little more to ask for in favour of convicted prisoners, the ICRC decided to suspend sine die its visits to the latter, for the second time in its history.Footnote 73 ) In 1978, as the ICRC sought to step up its activities in the region, Hay went so far as to write to James Kruger, South Africa's minister of justice, police and prisons, to raise the matter of very low detainee morale.Footnote 74 At the time of writing, the ICRC was submitting detailed written statements from twenty-five recently convicted prisoners about their ill-treatment and torture while they were detained and under interrogation. They were mainly young men arrested in the wake of the Soweto uprisings, and the statements they wrote for the ICRC were fresh evidence of ill-treatment. This infuriated Kruger, who was pressing for the publication of a relatively favourable ICRC prison report which, taken out of context, would have produced a partial and highly misleading impression of delegates’ overall findings. Many of these younger ANC detainees were also refusing to talk to the ICRC's delegates, arguing that their visits, subject to so many limitations, “served no useful purpose” and that they simply “whitewashed” the South African authorities.Footnote 75 Hay therefore warned Kruger that the ICRC's position in South Africa was fast becoming untenable. The risk of giving the appearance of some kind of collusion between the ICRC and the South African authorities was ever present, but all the more acute at this juncture. Kruger was told that if the government would not publish in extenso the reports of all ICRC visits, either the ICRC would do so or the reports would be made available to the press or other organizations upon request.

The effectiveness of humanitarian and human rights groups

Political detention brought into sharp relief the limits of humanitarian action and human rights activism. A whole new infrastructure was painstakingly built by a post-war generation of international and non-governmental organizations to defend detainees in court, to visit them and take care of the welfare of families, and to document their experiences upon release. A key aim of that infrastructure was to limit the sense of isolation of detainees; regular and repeated visits were understood to be one key part of that process, and access to education, recreation, news and family another.

Figures 7 and 8. New recreation hall for prisoners, Robben Island, 10 April 1967. ICRC Archives, Geneva. Photographs by Godfrey Cassian Senn, © ICRC.

This brings us to the question of effectiveness. Did an international presence provide the hoped-for protection, or did it create a false sense of security? To what extent did humanitarian and human rights groups operate as a restraining or challenging mechanism on late-colonial and postcolonial violence? The growth of activity on behalf of detainees certainly threatened to break down the seclusion of a late-colonial world, to open up avenues for legal redress, and to thrust the actions of detaining powers into a new and much more volatile international arena. Forced onto the back foot at the UN, where colonialism was rapidly losing much of its legitimacy, detaining powers were often cautious about bypassing external scrutiny and not allowing outside visits to go ahead, judging the price of such actions to be too high. Equally, however, they were determined not to have their emergency powers excessively curtailed or, for that matter, to be outmanoeuvred in international fora.

For the ICRC, there was always risk of falling into a trap of relatively meaningless visits in the hope of achieving slow, incremental change. To be set against that, however, are the views of many former detainees who recalled with gratitude the ICRC's work in diligently listening to their complaints, monitoring their conditions and persuading the authorities to make concessions. This takes us back to the very nature of the detention experience, marked as it was by uncertainty, deprivation and intimidation. Any visits to political detainees or improvements in detention conditions had a symbolic as well as substantive value – detainees knew they had not been forgotten. Such efforts undermined the “complete blackout” that Mandela saw the authorities as attempting to impose.Footnote 76 The visits of outsiders, whether from the ICRC, Liberal MPs or churches, reduced the sense of isolation from which detainees suffered. This is why so much store was set on obtaining news. Inmates would go to almost any length to obtain – and conceal – even scraps of information.Footnote 77 Newspapers, in Mandela's words, were “more valuable to political prisoners than gold or diamonds, more hungered for than food or tobacco”. To have access to news was to reconnect with the outside world.Footnote 78

We do not yet fully understand the reasons for timings of particular changes in regime policy and practice in South Africa, partly because of the difficulty of gaining access to relevant State archives. While the early years on Robben Island were particularly harsh, subsequent improvements in conditions were not always sustained. There was, for example, a notable regression in the behaviour of prison wardens on Robben Island in the early 1970s with the arrival of a new commanding officer, Colonel Badenhorst. In June 1973, the ICRC's president, Marcel Naville, wrote to the South African minister for foreign affairs, Hilgard Muller, to say that it was disappointing for all concerned that ten years after the first ICRC visits to prisoners, the most serious shortcomings in detention conditions were effectively the same.Footnote 79 Naville wrote of the “moral ordeal” inflicted on prisoners by their isolation from the outside world, which the ICRC was at a loss to “find any valid justification for”. He then went on to propose that the South African authorities thoroughly review their policies toward prisoners working, studying and having access to news.

Special access to UN and ICRC archives made the writing of this article possible, and much of the material presented here has never been seen or cited before. That said, without access to the archives of the Republic of South Africa − which may have been destroyed − it will always be difficult to explain why the authorities conceded particular things at particular moments in time, or at what level in the bureaucracy these decisions were taken. Prisoner resistance is likely to have been a major factor in many, perhaps the majority, of these concessions, as evidenced by the memoirs of detainees. Equally, such resistance was clearly bolstered by pressure from the very few outsiders who had access to prisons: the media, ex-prisoners, the UN and various local and international anti-apartheid movements (although the ICRC largely avoided contact with the latter, if only because they were always closely scrutinized, and at times even infiltrated, by the police and security services). Similarly, lack of access to State archives prevents us from establishing with any real clarity the evolution of the political situation and the shifting mentality of the authorities. When, for example, did the South African government arrive at the view that Robben Island inmates would eventually leave their cells, and even play a part in running the country, and so needed to be prepared for their release? Access to news came very late in the process of negotiations − does this signal such a shift of mentality? What arguments had carried the day? The truthful answer is that although we may hazard a guess, we do not really know.

What we do know is that just as political detainees were over time able to achieve a high degree of organization, there were decisive developments in the ICRC's approach to detention visiting during the 1960s and 1970s. The ICRC became more alert to the apartheid regime's tactics of improving prison conditions prior to visits, holding press briefings to discredit visits, impersonating Red Cross delegates, and selective citation of ICRC reports. Meanwhile, the confidence of detainees in ICRC delegates and the quality of their visits was gradually increased. The key factor here was the laying out of a basic framework for detention-related work: access to all detainees and to all facilities, private and unsupervised conversations, authorization for regular and repeated visits, the professionalization of the role of the delegate, and larger delegations including medical staff.Footnote 80

There were, to be sure, limits to what could be achieved, and senior figures in the ICRC were under few illusions. In 1974, Jacques Moreillon spoke of the “crazy situation of today's international law” where “the alien is better protected than your own national”.Footnote 81 He saw the maltreatment of political detainees during their initial interrogation and subsequent detention arising principally from three factors: first, the securing of intelligence regarded as vital for State security; second, a State policy of terror; and third, the lack of checks on the behaviour of prison warders and officials. Moreillon – a fiercely intelligent and politically shrewd delegate who later rose to become the director-general of the ICRC – arrived at a sobering conclusion. He felt that regular visits of outside bodies, like the ICRC, might be of help with regard to the last of these factors – namely, curbing the ill-discipline of prison warders. However, such visits were unlikely to make much if any impression on methods of interrogation when intelligence could not be gathered in other ways.

The sad and stark truth behind Moreillon's observation is attested to by an important and strangely neglected study undertaken for the ICRC by Laurent Marti in 1969 − a study prompted by mounting concern over the use of torture. Marti posed the question of what constituted a place of detention, and in response put forward “la doctrine des quatre murs”.Footnote 82 According to this doctrine, a person was of legitimate concern to the ICRC regardless of whether he or she was detained in a police cell, a prison or a detention camp. Visits to prisons and camps were generally admitted at this time, but, significantly, not to police cells, where interrogation often occurred soon after a suspect's arrest. Marti insisted that the right of visits be extended to each and every place of detention (including those currently unregulated) if the ICRC was to report satisfactorily on the treatment of all political detainees.

Marti and Moreillon were experienced ICRC delegates who were mindful of the ICRC's lack of access to places of interrogation as well as the need to improve the methodology of prison visits to enhance their value. Nor was the ICRC the only organization grappling with the issue of detention at this time. By the early 1960s the question of the ICRC's inspection of detention centres was closely linked to Amnesty International's concern to establish a basic international code of conduct, adopted by the UN, for the treatment of all persons suspected of endangering the security of their States. Other options to protect political detainees that were actively canvassed at this juncture, even if they were ultimately discarded, include an international prison under UN control to be used by member governments in emergencies; international areas for the purpose of providing asylum to political refugees; the despatch of trained UN observers to trouble areas; and UN prison rules with special provisions for the treatment of “political prisoners” and “freedom fighters”.Footnote 83

Whatever the actual or verifiable impact of humanitarian and human rights groups, it is important to recognize that it was ultimately the detainees themselves who fought the system the hardest, and who with considerable courage negotiated the routines of their everyday lives.Footnote 84 They sought to empower themselves through education − Robben Island was later dubbed “Mandela University” – and they put pressure on and sometimes deliberately provoked prison administrations through active and passive forms of resistance. Arguably they alone could not have secured the improvements described in this article, and several detainees later stated that the privileges they secured were in large part due to the work of the ICRC.Footnote 85 Nonetheless, the influence of outside organizations, important as it may sometimes have been, always needs to be set in this wider context.

In terms of improving the conditions of detention, it is likely that the biggest breakthroughs were a product of combined prisoner resistance and outside pressure, and that outside pressure was all the more effective when carefully aligned with detainees’ own struggles. Early if modest improvements in the 1960s in diet and clothing, and later improvements in the mid-1970s including studies (where restrictions were considerably relaxed), work regimes (considerably reduced if not yet ended)Footnote 86 and medical care (better organized, with more doctors and visits), all attest to this – they were regarded as high-priority by Mandela and his ANC colleagues and hence were actively agitated for.Footnote 87 Conversely, the lack of progress over almost two decades in securing any substantive concessions on the rationing of correspondence, family visits (their length was extended and their number raised from one to two per month in 1977, but visits by children remained prohibited)Footnote 88 and access to news serves to highlight the limits of what could be achieved – yet also the persistence and tenacity required to obtain improvements when they were eventually granted. We have already noted the importance of prison visits and letters: “the only real life-line with normality” which assumed an “almost grotesque importance”, in the words of one detainee.Footnote 89 The desire to know what was happening in the outside world remained similarly undiminished.Footnote 90 Access to news – always highly prized – did eventually come in 1979–80; the following year prisoners were permitted to receive daily newspapers without censorship, a major breakthrough.Footnote 91 Two years later, further concessions were secured on correspondence (increasing the number of letters), visits by children under the age of 5, and material support to finance the trips of families from their homes, but visits by non-family members and older children remained prohibited even at this time, despite repeated protests that the latter restriction had led to an “alienation of family feelings”.Footnote 92

Humanitarianism and human rights: A troubled rapport

The ICRC is a humanitarian organization, Amnesty International a human rights group. This brings me to my final point: the troubled rapport between humanitarianism and human rights.Footnote 93 Humanitarians and human rights activists have not been averse to presenting themselves in oppositional terms;Footnote 94 the promotion of the one is often perceived to have been at the expense of the other.Footnote 95 Humanitarianism is based on a discourse of charity and suffering, and many aid agencies are cautious about speaking out against rights abuses for fear of jeopardizing access to people in need and of politicizing humanitarian action to the point of draining its moral purpose.Footnote 96 Human rights, by contrast, are based on a platform of justice and solidarity, and providing relief is considered secondary to gathering evidence about atrocities and denouncing their perpetrators.

Amnesty International and the ICRC are frequently held up as exemplars of these different modi operandi or working modalities – compassion and charity versus justice and solidarity; material support versus an emancipatory vocabulary of rights; and private persuasion versus public denunciation. The reality in the South African case was invariably more complicated, however. Whereas disputes erupted into the public arena and have attracted the attention of historians, cooperation concealed itself behind closed doors and is considered to be of less interest to their readers. Privately, Amnesty did in fact share information with the ICRC's delegates in Africa as they passed through London, although this was more on the state of Portuguese prisons than on Robben Island, of which the ICRC knew much more than Amnesty anyway. Conversely, with the possible exception of the UN Working Group, there is little evidence to suggest that the ICRC informed any outsider, including Amnesty, about the conditions of South African detention.Footnote 97

Institutional rivalry notwithstanding, it was, nonetheless, the quiet and unannounced post-war revolution in detention visitation that provided the terrain upon which the concerns of humanitarians and human rights activists converged. This is not to deny that challenges to humanitarian “minimalism” came from rights groups, development agencies and peace-building bodies. But the humanitarian agenda was itself broadening during decolonization. In making claims on behalf of victims, aid agencies, working alongside human rights groups, adopted ethical witnessing as an integral part of their work. Nowhere is this blurring of boundaries between humanitarianism and human rights more clearly seen than in relation to the fact-finding missions, gathering of personal testimony and detailed documentation of abuses from the 1960s onwards.Footnote 98 A new literary genre of human rights reporting emerged, factual and forensic, framed around stories of individual suffering. It was a type of “monitory democracy” whose aim was to validate the victim rather than search for the causes of victimization − “advocacy with footnotes”, in the words of Ron Dudai.Footnote 99 If nothing else, this seriously calls into question the presumptive human rights surges of the 1940s and 1970s that have tended to dominate the more recent historiography.Footnote 100 Arguably, the 1960s stake the stronger claim as the decisive decade.

In the quarter-century after 1945, what we really see is the continuous development of a network of international organizations seeking to lift the veil of secrecy over places of undisclosed detention and expose the weaknesses of international law regarding internal armed conflict and other situations of collective violence. Through their combined if not always coordinated efforts, humanitarians and human rights activists sought to gain greater recognition of the necessity of extending existing norms into states of public emergency. The post-war era was a turning point in the relationship between evolving humanitarian and human rights agendas: the concerns of the one were expanding rapidly towards those of the other. There was, moreover, great fluidity in what it meant to do human rights and humanitarian work at this time, with different approaches and ways of working as likely to be found within as they were between international organizations.Footnote 101

Detention today: The future of the past

In late 2014, the international media poured over the redacted summary of a suppressed 6,000-page CIA report which revealed shocking details of how, in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, suspects were interrogated and tortured at secret, out-of-sight “black site” prisons around world.Footnote 102 The chair of the US Senate Intelligence Committee declared this to be an “ugly stain” on his country's history and reputation. By so-called “enhanced”, “advanced” or “coercive” interrogation techniques, call them what you will, detainees were subjected to loud noise, simulated drownings and sleep deprivation and stress positions, all of which were deemed by Barack Obama as contrary to American values. The US Senate found that information obtained from these techniques had been neither reliable nor effective, nor had it produced intelligence that could not have been obtained from conventional (non-violent) interrogation.

This begs the question of what, if anything, has actually changed since the late-colonial and apartheid era. Some forty years prior to the publication of the CIA report, the UN had passed its first resolution on “Human Rights in Armed Conflict”, and a 224-page Amnesty International report on torture had observed a growing tendency for governments to authorize and condone “inhuman or degrading treatment”. The use of torture, Amnesty then argued, was becoming a more routine part of interrogation in many parts of the world, whether to extract information or to control political dissent, with interrogation techniques constantly refined. More specifically, from its investigation of 139 countries, Amnesty claimed that sixty-three had used torture, thirty-four as “a regular administrative practice”. It went on to declare that the scale upon which torture was being used was a “disgrace to modern civilisation”, and to launch its first worldwide campaign for the abolition of torture in 1972.Footnote 103

Precisely when torture became a taboo is a matter of open debate among historians. A new historiography on human rights is mirrored by a new literature on torture which suggests that “most citizens of the Cold War wanted to avert their gaze from torture rather than to mobilise to stop it”.Footnote 104 As this article has shown, over the years the ICRC had tried – and failed – to gain access to detainees under interrogation in South Africa. Publicly or privately, the exposure of assaults or torture, whether by the ICRC, Amnesty International or any international organization, shows no sign of having ever inhibited those involved. After repeated refusal of requests for access to non-convicted detainees, the ICRC decided in 1987 to suspend all visits to convicted prisoners. Meanwhile, improvements in the material conditions of detainees were from time to time secured, even if it is not always clear precisely for what reasons. These concessions had the effect of improving prisoners’ morale and reducing their sense of isolation, and many inmates clearly felt that the ICRC had been useful in voicing complaints, solving problems, restoring privileges and (later) providing financial support.Footnote 105 Prisoners could be harassed after ICRC visits, yet they were equally aware of positive changes. Mandela himself felt that the authorities were keen to avoid international condemnation, and that this fact alone gave the ICRC, as an independent organization “to whom the Western powers and the United Nations paid attention”, a certain degree of leverage.Footnote 106 Over time, ICRC delegates developed a reputation for competence, perseverance and objectivity, and of not being easily fooled by the prison authorities.Footnote 107 That said, the fact that all contact with the outside world remained highly constrained throughout the 1960s and 1970s – and the major breakthrough on access to news did not happen until 1979–80 – is a powerful reminder of the highly oppressive nature of the apartheid regime and the limited scope of any international organization to counter this. At the heart of the South African prison system, to recall the words of one detainee, was the denial of the humanity of “the other”, and in that sense it faithfully mirrored the wider ethos of the racialized State from which it was born.Footnote 108 Nor were improvements to prison conditions always sustained: “The graph of improvement in prison was never steady”, Mandela observed.Footnote 109 For example, a more liberal regime on study was to be considerably curtailed in the later 1960s before relaxations were later achieved, and in the early to mid-1970s, ANC detainees spoke of a “deep-freeze” or hardening of attitude on the part of prison warders whereby news of the outside world was systematically denied.Footnote 110 Certainly, it would be difficult to claim, based on the available evidence, that the lobbying and campaigning of international organizations in the post-war era produced a fundamental attitudinal shift such that public opinion presumptively condemned either the physical or the psychological torture of political detainees. (There may be a better case for arguing for such a shift with regard to what has been called the “two worlds” approach to rights discourses, whereby what were perceived as “primitive” and “backward” societies were not regarded as ready for European or Western rights regimes.Footnote 111 )

The problem of how to protect rights in armed conflict remains, as is evident in Syria, Iraq, Libya, Yemen and Ukraine, to name but a few of the more egregious cases that currently fill the pages of the press and feed social media on a daily basis. Because so many rights violations occur in the context of armed conflict, and because by far the most problematic type of protracted armed conflicts are those below the threshold of full-blown civil wars, the nexus between international humanitarian law and international human rights law continues to be of great concern.Footnote 112 Since the end of the last century the UN has placed greater emphasis on integrating human rights into humanitarian action, and given more recognition to the role of its own specialized agencies in assuring respect for human rights in situations when States are unwilling or unable to do so.Footnote 113

The work of building a critical dialogue between the humanitarian and human rights communities extends well beyond the precincts of the UN, however. These two bodies of international law have developed in parallel; according to their respective advocates, the former, the “law of war”, is aimed at striking a balance between military necessity and the protection of humanity, while the latter is based on an individual rights paradigm and aimed at protecting people from the arbitrary behaviour of governments at all times, including war. But however much it may sometimes suit their advocates to emphasize such differences, both of these bodies of law intersect at a critical juncture – namely, the circumstances in which the international community is prepared to contemplate constraining State sovereignty in favour of stronger protection, whether we frame these circumstances in humanitarian terms as a right of “initiative” or “intervention”, or in human rights terms as non-derogable rights which can't be suspended in any circumstances, including states of national emergency. Either way, what we are effectively talking about is a duty, obligation or “responsibility to protect”.Footnote 114

The title for this article, “Restoring Hope Where All Hope was Lost”, recalls the poem “Doubletake” by Seamus Heaney.Footnote 115 In this poem, Heaney writes movingly of human beings suffering and torturing one another − “They get hurt and get hard” − and of history telling us not to hope, at least not “on this side of the grave”. Yet in same breath Heaney goes on to conjure up an image of a “further shore” that is “reachable from here”, and to speculate how, once in a lifetime, a “longed-for tidal wave of justice can rise up” − a “great sea-change on the far side of revenge”. Hope and history, Heaney says, can then rhyme. For hope and history to rhyme for today's political detainees − or “security detainees”, as they are now more commonly called − the complementary action of international humanitarian and human rights organizations is imperative. Humanitarianism and human rights have often existed in a state of troubled rapport. But it is, above all, in the domain of detention that we can see the concerns of one expanding towards those of other. And it is in the domain of detention that the international community now needs to crystallize a new concurrence of approaches of humanitarian norms and human rights guarantees, not by ignoring their differences but by turning them to better account.