Interest in displaced persons has been growing in the international community since the 1990s. The number of internally displaced persons has increased considerably as borders have gradually been closed (strategies to ‘contain’ crises and population movements)Footnote 1 and ‘new’ complex long-term conflicts have emerged.Footnote 2 Internally displaced persons have become a fact of life in today's humanitarian world and the focus of keen competition amongst actors aiming to gain legitimacy and influence in this sad and terrible field of opportunity. The recent reform of the UN system originated mainly in the realization that, despite the initiatives taken to promote assistance and protection, the situation of these displaced populations was still particularly critical.Footnote 3 After years of oblivion, renewed attention has for several years been focusing on displaced people who have relocated to urban areas. Lost in the urban multitude and dissolved into the surrounding poverty, this elusive population has often escaped the humanitarian machinery, falling outside its fields of operation or jurisdiction. A major initiative has been underway for three or four years to try to remedy this shortcoming; it consists of devising methods of ‘profiling’ displaced persons who have settled in urban areas in order to have a better idea of their characteristics and needs.Footnote 4 The present article pursues a different purpose, seeking to understand the issues and problems raised by displaced populations who settle in the capital, and to examine how the various actors cope with the phenomenon. A long-term study of the circumstances of displaced persons in Khartoum and BogotáFootnote 5 revealed the similarities between these two highly different contexts, and provided a basis for understanding how and why they differ and how they have evolved. The massive presence of displaced populations in the capital cities of Khartoum and Bogotá, although of varying intensity, raises fairly similar issues, but the policy decisions taken to deal with the situation differ widely. As a result, both the panels of aid actors involved and the strategy choices they make differ from one context to another.

Displaced persons – a category shaped by politics

The term internally displaced persons (IDPs) is now used virtually unanimously by the international community, as though the reality it designates were uniform and agreed. Yet depending on the context and on who is using the term, the population group to which it refers is very heterogeneous. Rather than evading the complexity of the term and of the circumstances in which it was developed, we wish to focus on the expression to demonstrate that it is profoundly political and ideological in concept.

An attempt was admittedly made over ten years ago in the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement to define the term of IDP:

‘persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalised violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognised State border.’Footnote 6

There are two factors in this definition that are beyond debate: the coercive nature of the displacement, and the fact that it takes place within an internationally recognized border. However, due to the nature of these Guiding Principles (soft law), this definition is non-binding, and the list of possible causes of displacement that it contains is non-restrictive (being preceded by the expression ‘in particular’). There is thus room for interpretation on the part of the person using the term. For example, are natural disasters, whether man-made or not, to be regarded as a cause of displacement? More specifically, are the people who have been displaced by drought and famine in Sudan IDPs? Are the people who have been displaced by the fumigations of coca fields in Colombia IDPs? Furthermore, the fact that this definition is non-binding and the looseness of its interpretation means that the authorities can set their own definition criteria to suit the imperatives of the regime's domestic policy and ideological motives. Let us take a further look at this point.

Colombia – legislation and a specific status for displaced persons

Colombian legislation is regarded as an example at the world level when it comes to displaced persons.Footnote 7 Special attention was devoted to displaced persons at a very early stage in Colombia,Footnote 8 and specific legislation was introduced back in 1997, one year prior to the adoption of the Guiding Principles by the UN General Assembly, although it was very clearly based on the work carried out by Francis Deng's team at the time.

There is a legal, and thus binding, definition of IDPs in Colombia: ‘A displaced person is any person who has been forced to migrate within the territory of Colombia, thus abandoning his/her place of residence or usual economic activities, because his/her life, physical integrity, or personal safety or freedom have been flaunted or are directly threatened due to any of the following situations: internal armed conflict, internal unrest or tension, widespread violence, massive human rights violations, violations of international humanitarian law or other circumstances resulting from previous situations which can impair or drastically affect public order’.Footnote 9

The Colombian definition disregards natural or man-made disasters from the outset. Any citizen who declares to the public prosecution department that he/she has been displaced and whom the public authorities recognize as such acquires displaced person status and thus has access to the system of aid provided by law.Footnote 10 The question of who is recognized as a displaced person and who is not thus becomes crucial. The determination of the criteria for defining IDPs is thus profoundly influenced by politics. The non-recognition of persons who are displaced as the result of fumigations and the implementation of major agricultural projects and the growing temptation to no longer recognize populations that have been displaced by paramilitary groups are the result of domestic policy decisions. In the context of the Colombia Plan initiated by the United States, the massive eradication of illegal crops is an essential component of action to combat drugs. The fumigation of coca fields causes the displacement of people, who are thus deprived of their livelihood. Yet at the present time, it is imperative that any examination of the location of fields where coca is produced and of the laboratories where the drug is processed include an analysis of the conflict. It is now a well-known fact that armed groups have close links with this parallel economy,Footnote 11 and it sometimes becomes artificial to make a distinction between persons who have been displaced because of drug production and those who have been displaced as the result of conflict. Similarly, when large-scale production projects are being launched, investors frequently rely on the support of armed groups in order to ‘free up’ productive land. To evade the responsibility of the State and of those armed groups in these two cases of displacement is thus basically a political issue; the image of noble US–Colombia co-operation and of the major investors must not be tarnished. Likewise, the policy of ‘Justicia y Paz’ and democratic security pursued since President Alvaro Uribe's accession to power in 2002 has led to dialogue with the paramilitary groups resulting in their demobilization. Officially, there are no more paramilitary forces in Colombia; thus to recognize that displacements are still being caused by such organizations would amount to recognizing that Uribe's policy for resolving the conflict has failed, at least in part. Yet it has now become manifest that the paramilitary groups are remobilizing in local militias and that the forced displacements caused by these new groups are continuing.

Sudan: long ignored, displaced persons are now a major political issue

The situation is very different in Sudan.Footnote 12 Under repeated and growing pressure from the international community the Sudanese regime has gradually come to recognize the problem of forced displacement. Sudan's relations with western countries have been stormy, to say the least, and the subject of displaced persons has on certain occasions provided an opportunity to make amends. Political decisions on the issue have long remained evasive, however, and have rarely been implemented. A succession of institutions has been set up since the 1980s, to little avail. The criteria used to define displaced persons (who are known as naziheen in Sudanese Arabic) and to distinguish them from others have changed from one era and actor to another. The tribal criterion and geographic origin have prevailed for a long time. The great majority of Sudanese regard people who come from South Sudan and are living in the North as displaced persons, and this has been extended more recently to cover some of the Darfuris who are now living in Khartoum. The question of what caused the displacements is not broached, and people are classed as naziheen – or not – according to physical criteria, manifest social vulnerability, date of arrival in the North or place of residence (urban fringe districts, camps for displaced persons). The actual causes of displacement do not seem to be of any particular significance. ‘Naziheen’ is a pejorative term, which, as will be seen below, results in considerable discrimination on the part of the regime. The term ‘IDP’, which has been imported by the international community and humanitarian actors, is of a different register, since it can lead to access to aid programmes and represents possible positive discrimination. Humanitarian actors have not clarified the vagueness surrounding this population group in Sudan, however, and the term ‘IDP’ generally refers to population groups in Khartoum, people who have come from the South, the Nuba Mountains or Darfur, are living in the outskirts of Khartoum, and are extremely vulnerable. However, an attempt was made in the recent work preceding the promulgation of the new policy on displaced persons in 2009 to fill this gap and put an end to the ambiguity. Although several international organizations encouraged the government in this process of reflection and decision-making, providing support and advice, the definition which the government eventually opted for in the final version of the policy is so evasive that, depending on how it is interpreted, it can cover a large proportion, or just a fraction, of the Sudanese population. Displaced persons are defined as individuals or groups of individuals who have been forced or obliged to leave their homes due to, as the result of, or in order to avoid the consequences of a disaster, whether natural or man-made, and who have moved to other places in Sudan.Footnote 13 There is no direct reference to situations of armed conflict or violation of human rights or to international conventions or the Guiding Principles. The significance and effectiveness of this document is thus likely to be similar to that of the Sudanese government's previous commitments regarding displaced persons and should not require any change of strategy.

However, as has been shown by the promulgation of a new policy (however ineffective), it will be seen in the following paragraphs that the subject of displaced persons has gained greatly in value for the political players in Sudan since the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement between North and South Sudan in 2005. The subject is also of high diplomatic value for a country where humanitarian issues have become an imperative topic in the relations it entertains with third countries.

Living on the urban fringe

Examination of the location of displaced people in the Khartoum and Bogotá conurbations has revealed one feature that they have in common – which, in fact, is not surprising, and that is that most of the displaced persons live on the urban fringe. This location on the periphery is due to several factors. Displaced people are pushed out to the urban fringe both by market forces and by State regulatory measures and planning. It is less expensive to live in the outskirts than to live in the city (price of land and housing, whether for rent or for sale, rates charged for ‘public’ services, and cost of basic necessities), and in the case of Khartoum the booming property market has exerted particularly strong pressure on the vulnerable populations living in the pericentral districts of the city. In Bogotá, the city districts are classed according to the socio-economic characteristics of their inhabitants as a basis for pricing public services: the richer the inhabitants, the higher the rates. The aim of this progressive pricing is to achieve greater social justice, but it also has the negative effect of grouping and settling the most vulnerable population segments on ‘poor man's lands’. The measures taken by the State are fairly strong and more or less authoritarian, and they take on different forms. In Khartoum, the State exerts direct authoritarian pressure on the location of displaced persons in the conurbation by demarcating districts where they can set up home (Dar Es Salam, created towards the end of the 1980s, and camps for displaced persons, which were set up in 1991) and through mass evacuation measures and the creation of resettlement districts for these population groups that have been driven out of the city. In the 1990s, the public authorities cleared squatted districts en masse in this fashion by means of forced evacuations coupled with the demolition of entire districts and the transfer of the populations to more peripheral areas.Footnote 14 In the early 2000s, the State embarked on a new phase of legalization of squatted areas, proceeding in the same way as before but this time also extending its action to the camps for displaced persons.

Map 1. Districts and sites where displaced persons have settled in the Greater Khartoum areaFootnote 15.

Map 2. Distribution of the displaced population by district in the Greater Bogotá area.

In Bogotá, as is the case in Khartoum, the fact that displaced persons have settled in the outskirts of the capital on a massive scale poses a considerable challenge to urban planning. The 625,000 displaced persons who arrived in Bogotá between 1985 and 2006Footnote 16 account for over 8.5% of the total population of the municipalities of Bogotá and Soacha:Footnote 17 (7,242,123 inhabitants). Khartoum has an estimated displaced population of 2 million, some 40% of the total population of the conurbation (4.5–5 million)Footnote 18. This population influx is thus far from negligible and contributes dynamically to urban growth in these capitals. The policy choices and the measures taken to accommodate the displaced in the city obviously depend on how the various actors analyse the situation, and in particular on whether they regard the presence of these displaced populations as an interim situation. What is more, certain characteristics of the displaced population that are common to both Sudan and Colombia are a further obstacle to their integration in the city. The great majority of these people come from rural areas and thus do not have the necessary skills for finding employment in an urban context when they arrive,Footnote 19 and the fact that they have a lower lever of education than the rest of the population in the municipality adds to already restrictive hiring practices. Due to the trauma that they have suffered and the fact that they have lost their property and the greater part of their social networks, their isolation and vulnerability are particularly acute.Footnote 20 This statement must be qualified, however, since there are several networks of solidarity that endure in both Bogotá and Khartoum, despite displacement, or which have come into being as a means of coping with the adversity that follows in its wake. In Sudan, for example, belonging to a tribe plays a major role in displaced persons' choice of location when they arrive, and in Colombia the Catholic Church stands for a national network of mutual aid. Displaced populations in urban areas are thus marginalized on two scores – their social marginality is exacerbated by spatial marginality.

A population that is threatening for the capital

For several reasons, the displaced population seems threatening for the capital, where many residents see the arrival and settlement of displaced people as an additional security risk. Each case must be examined separately, for the factors of tension and the dangers, whether real or imagined, that are associated with the displaced in the city are specific to each context.

Khartoum, a besieged city?

In Khartoum, the displaced population is particularly large for the capital in numerical terms, and its arrival upset the demographic balance. It is estimated that 1.1 million of the 2 million displaced people living in Khartoum have come from South Sudan; the remainder come mainly from the Nuba Mountains and Darfur. The South Sudanese are very different from the people from North Sudan, since they are designated as African, as opposed to the North Sudanese, who define themselves as Arab and, for the most part, are not Muslim. They have distinct physical features and dress, and their origins are not to be concealed. The ethnic composition of the population of the capital has thus changed drastically as the result of the arrival of the displaced populations. Many North Sudanese regard this ethnic diversity as a threat and even as an adulteration of the Arab Muslim identity advocated by the regime in Khartoum. The feeling of being threatened is no doubt related to irrational factors, which are found in many other contexts connected with unfamiliarity and fear of others but also with objective factors of potential destabilization. Displaced persons, by definition, come from regions in conflict and are thus considered to have a dubious past: they may be partisans of the rebellion, they may have supported it, or they may still be supporting it. Politically, they generally support opponents of the regime. The camps for displaced persons and the districts where they live are areas where there is a strong Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) presence (the SPLM is the political branch of the Sudan People's Liberation Army, an armed group that fought the armed forces in North Sudan during the war between the North and the South). Several events have in fact confirmed that displaced people can become a significant factor of destabilization for the capital. First, the riots that broke out after the death of John Garang on 30 July 2005 made a lasting impression on the inhabitants of Khartoum. Following the announcement that the helicopter that was bringing the South Sudanese leader back from Uganda had crashed, there was an uprising of South Sudanese living in Khartoum, who invaded the streets of the capital and took it out on the North Sudanese, who were the symbols of the regime of oppression. Scores of people were killed in these riots, which were led first by the South Sudanese and then in retaliation by the North Sudanese against the southerners. A more recent event, the Omdurman attack, which was led by the Darfur rebel group Justice and Equity Movement, was followed by a government crackdown on people from Darfur living on the outskirts of Khartoum. Again scores of people were killed in this attack, which exacerbated the climate of distrust of displaced people from the west of the country. The security risk associated with the influx of displaced people into the capital is thus very real, though no doubt exaggerated by the regime, for which it provides facile justification of segregation and discriminatory measures.

Bogotá, urbanization of the conflict and urban violence

The displaced persons in Bogotá are not as markedly different from the local population as is the case in Khartoum. However, the conflict afflicting Colombia is of a different nature, pervasive and rampant, and is gradually permeating the various spheres of life in the country – economic life, political life, and people's private lives. Bogotá has in general been spared by this seemingly interminable conflict, with the exception of certain dark episodes in its history. The relative tranquillity enjoyed by Bogotá is the result of police control and a national defence strategy that aims to protect the capital, the seat of power, but it is also maintained by political discourse that invariably denies the possibility of the conflict penetrating the city. The noose has been tightening for several years, however, and it is becoming more and more difficult to deny the obvious: the conflict is infiltrating certain parts of the city. The FARC modified their military strategy in the 1980s, aiming to ‘take the cities’, and they were followed by paramilitary groups in the 1990s who tried to counter that move.Footnote 21 Although many political actors are continuing to deny this trend, armed groups are present on the outskirts of the capital, and as the result of the recent measures to demobilize the paramilitaries these groups have gained a stronger foothold in Bogotá. ‘Obscure individuals’ have moved into these districts on the periphery, where they swell the ranks of the urban militia groups that contend for control of territories and for the economic and social control of these districts. The displaced population is frequently associated with this phenomenon of the urbanization of the conflict. ‘If they (the displaced people) are here, there's a reason – they'll have done something.’ Their mysterious past soon becomes dubious in the eyes of the inhabitants of Bogotá, and they are often held responsible for the troubles that afflict them. Poverty, isolation and the trauma of displacement have made families vulnerable – particularly the children of displaced people, who become the prime targets and recruits for the local underworld. The displaced are thus often associated with the violence of which they are the victims. It is an undeniable fact, however, that the arrival and settlement of displaced persons in the capital has actually enabled and is still enabling armed groups to infiltrate the city on the sly. The arrival of these persons makes the city boundaries more porous and complicates the control of population movements. The infiltration of members of armed groups into the registers of displaced persons has been exposed on several occasions. This phenomenon means that the infiltrated members can be concealed and maintained, but on the other hand it discourages the registration of authentic displaced persons, who are afraid of being spotted mixing with former paramilitaries or former members of the guerrilla. Displaced persons who settle in the city are disturbing for a resident population that has become distrustful after decades of conflict, but what is more, they also facilitate the infiltration of the armed groups and the proliferation of the gangsters of whom they are the primary victims.

Although the challenges and problems raised by the arrival of these populations in the cities are fairly similar (adapting infrastructures and services to urban growth, controlling the new demographic balances and new population groups), it will be seen in the following section that the political responses in Khartoum and Bogotá and, consequently, the ways in which aid actors are involved in that response are very different.

Bogotá, an approach that focuses on individuals and on their rights

The law that was passed in Colombia in 1997 guarantees special attention for the displaced population. As Angela Carillo explains in detail in her article,Footnote 22 obtaining displaced person status confers the right to what is termed emergency aid for a renewable period of three months (although due to administrative and logistical delays this aid is generally delivered once the immediate urgency is over) and then to socio-economic stabilization aid. The aid system is run through the Acción Social agency under the authority and direct coordination of the President's Office and is designed to provide comprehensive aid for displaced persons throughout the various stages of displacement, a further objective being to restore and protect their rights. As in the 1991 Constitution, the entire legislative framework relating to displaced persons is based on human rights. The response that has been developed to address the issue of forced displacement is thus profoundly social and involves lasting commitment and responsibility on the part of the State, since it is not merely a question of short-term policy but one of legal responsibility. What has actually been achieved obviously falls short of these extremely high ambitions, but the Constitutional Court has constantly urged the executive to honour its commitments to the displaced and has required it to do so in various rulings. The budgets allocated by the State to this comprehensive aid for displaced persons have risen steadily, with significant increases since 2004 (the year in which the Constitutional Court issued Ruling No. T025).

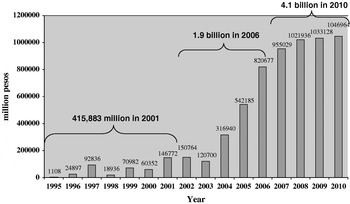

Figure 1. Budgets allocated by the government to aid for the displaced population (1995–2010)Footnote 23.

The Colombian State's response to displacement certainly is not perfect, but it is definitely improving, although the persistence of considerable needs and continuing vulnerability within the displaced population would seem to contradict this. One alternative is to call for ever-increasing commitment on the part of the State and the actors involved to improving the aid system; another is to devote thought to the actual effectiveness and relevance of the aid system that has been established in Colombia.

Aid actors in Colombia have to decide precisely where they stand in this dilemma. The great majority of the actors (donors, international organizations, UN agencies and NGOs) play a direct part in the operation of the comprehensive aid system that is co-ordinated by the State. USAID (United States Agency for International Development), for example, supports the State's efforts in aid of displaced persons and finances part of the integrated aid system. International organizations such as the FUPAD (Fundación Panamericana para el Desarrollo) and the IOM (International Organization for Migration) have two sources of funding – Acción Social and USAID, and participate to the full in the implementation of national policy in aid of displaced persons. The complex chain of funding sources and ‘sub-contracting’ contracts make this national aid system a vast and sprawling, convolute mechanism. Many international organizations and agencies as well as national and international NGOs play a role in the various components of this policy: emergency aid, socio-economic stabilization (training, income-generating activities, microcredit), psycho-social aid, education, health care, housing, etc. Some of these organizations are more critical of State policies than others, and some try to exert pressure on the government to improve its practices and commitment.

On the fringe of the aid system, several determined national and international NGOs are staging a trial of strength with the government, calling for action to improve or to reform the aid system. Civil society in Colombia is particularly strong and structured, and Colombian NGOs are not to be outdone when it comes to the political pressure movement. The trial of strength is mainly in the legal field, since the legal framework and legal institutions are particularly conducive to defending individual and collective rights. The Constitutional Court has on many occasions ruled in favour of displaced persons, exerting considerable pressure on the government and its administration. Some NGOs thus take up and support the complaints filed by displaced people and demand that their rights be respected and that the law be applied to the full. Others work more in upstream activities providing education, promoting civic and militant emulation and structuring the displaced population in grassroots organizations.

In this climate, displaced persons' protest campaigns abound. The strong political and trade union culture characteristic of Colombia is also to be found in the displaced populations, which are a breeding ground for NGO empowerment practices. Many leaders have emerged, and continue to emerge, championing the collective cause and structuring demands. Moreover, the law makes provision for the participation of displaced persons' organizations in the development of local aid plans, which set out how national policy on displaced persons is to be implemented at the local level. Displaced people take advantage of this opportunity to influence policy, but they also use the legal instruments at their disposal (petitions and trusteeship actions). In addition, they resort sporadically to more spectacular action, which consists of occupying public or symbolic premises, to try to break the silence and indifference and to win their case. Although these practices bring benefits in the short and medium term enabling the displaced to obtain their claims by force when the State is dragging its heels, they also widen the gap between the displaced and the rest of the population and exacerbate the climate of distrust and incomprehension between the displaced and civil servants and sometimes even between the displaced and aid actors.

Be that as it may, this panorama is only representative of the situation in the capital city of Bogotá and is without prejudice to the extent to which national policy on aid for displaced persons is being implemented or to the structuring and dynamism of the displaced population in the rest of the country.Footnote 24 The presence of the State is incomparably more marked in the capital, where the administration is also infinitely more efficient. National and international NGOs also have a strong presence, and the displaced population is also more thoroughly organized. Despite all of these remarks, which ought to mean that the displaced population is better integrated, and despite legal machinery which is extremely favourable for that population and is gradually increasing the responsibilities devolving on the State with regard to protection and assistance, most displaced people are still marginalized and particularly vulnerable, and there seems to be no solution to the gulf of distrust and incomprehension that separates them from the rest of the population. The Colombian experience must thus be questioned; perhaps it should be seen as a laboratory rather than as an example to be followed. Indeed, many donors and actors are currently seeking a model on which to focus attention, a model that would provide a way out of the rut and a means of permanently improving the situation of displaced people in their new living environment.

Khartoum, a spatial approach guided by security imperatives and political constraints

In Sudan, the approach to the displacement phenomenon is diametrically opposed to the Colombian model. Although there is no legislation on displaced persons, there are several reference documents establishing the regime's policy guidelines on the issue. An agreement between the North Sudan government's Humanitarian Aid Commission and its South Sudan equivalent that was signed in 2004 provides a framework for the return of displaced people to the South. The Government of National Unity recently decreed a new general policy on displaced persons (in 2009), but here again the vagueness of the terms employed is liable to reduce its significance.

The authorities in Khartoum have adopted two main lines of policy in response to displacement: spatial control and urban regulation on the one hand, and the return of displaced populations to South Sudan on the other. In order to cope with the imbalance resulting from the arrival of displaced persons en masse in Khartoum, the government has tightened up police and military control in the districts where they settle. Police checkpoints control movements in these districts. Police ‘raids’ in which houses are searched and the inhabitants are checked are particularly frequent, and outsiders must have an official permit in order to enter these zones. Civilian informants, who often live in the area and are paid by the government, also play a role in the control of these districts. People's committees (lijan sha'biya), which were introduced when Omar el Beshir came to power in 1989, are a further mechanism of social and political control. These grassroots units, which are set up at district level (one committee per 10,000 inhabitants) play a fundamental role in the administration of local affairs (particularly regarding access to basic services and access to land ownership). In theory, they are elected, but in actual fact they are a local relays of the ruling party, the NCP (National Congress Party), and the members are generally also NCP members. Urban policies, a further instrument of spatial control, are guided mainly by security imperatives and economic issues. Urban regulation and policies for legalizing districts and allocating land are an effective means of driving the most vulnerable population groups further out to the gates of the city and of controlling who obtains access to land in the capital while at the same time drawing financial benefits. The government's methods are authoritarian, and the legalization of districts involves the indiscriminate evacuation of the population and the demolition of homes by bulldozer followed – after several weeks or even months – by the allocation of demarcated plots. Access to land is governed by strict preconditions: Sudanese nationality (candidates must hold a birth or military service certificate), a dependent family (they must hold a marriage certificate), length of residence in the district, ability to pay the land access tax (in some districts the land is sold for a symbolic amount or even given away, but candidates must be able to pay the duties and fees involved in the procedures), and, in theory, they must have no other place of residence in the State of Khartoum. These legalization measures give rise to underhand practices, and corruption is rife, depending on the populations of the districts concerned. They also provide an opportunity for widespread land speculation, where displaced people rarely stand to win. Although the legalization of districts enables part of the displaced population to own land, it also results in the eviction of all those who are too vulnerable to participate in the system and in their relocation further into the outskirts. Although this process can cause considerable material losses for the inhabitants of a district, they are nevertheless very much in favour of it, since they apparently consider that the potential benefits (i.e. the possibility of holding a legal title to land) by far outweigh the losses involved.

Since the 1980s, when the first waves of displaced persons began to arrive en masse, the NGOs working in Khartoum improved the new settlement areas and then sought to attenuate the consequences of the government's authoritarian and discriminatory policy. They thus provided basic services in the camps, sank and serviced wells, built health centres and schools, and distributed food aid.Footnote 25 At the end of the 1990s, the mass withdrawal of humanitarian actors from Khartoum left the inhabitants of the camps for displaced persons in a precarious situation, since they were still extremely dependent on aid. There has been a veritable humanitarian ‘invasion’ in Khartoum in the last few years with a view to rebuilding the South following the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005 and the crisis in Darfur. Several actors launched projects in the capital on that occasion, mainly in aid of the displaced population. When the mass destruction and legalization of districts was resumed in 2003, in which the State began to extend its action to include the camps for displaced persons, the international community endeavoured to denounce and monitor the government's practices in the urban policy field. The pressure exerted by the international actors failed to halt the process, however, and the State only agreed to set up several joint committees (composed of Sudanese authorities and international actors). The most successful initiative was certainly the initiative launched by the Delegation of the European Commission, which made part of EU aid to Khartoum contingent on the signing of a commitment by the Governor of Khartoum to respect fundamental principles in compliance with human rights and the Guiding Principles. With the support of the UN Resident Co-ordinator, this memorandum of understanding between the international community and the local Sudanese authorities finally came into being and was signed in 2007. It is difficult to say what the tangible effect of this document has been, however, since the authorities have now legalized the vast majority of the districts in Khartoum. The climate is tense for aid actors and is not conducive to their taking a bold stance. All sorts of red tape and administrative delays and bottlenecks at times jeopardize access to the target groups and indeed the actual running of the project.

The measures to support the return movement, the other component of government policy on the displaced population, have received strong support from the international community. The governments of North and South Sudan and the United Nations signed a Joint Return Plan in 2006 for the organized return of 150,000 displaced persons in addition to the spontaneous returns that have been taking place since the signing of the ceasefire in 2004. The international community has contributed considerable financial support to the return process. The IOM has been selected to co-ordinate logistical support for the return movement, and many NGOs and agencies have become involved in the various phases of the Plan, organizing activities ranging from pre-departure information campaigns to assistance and protection during the return journey and on arrival in the resettlement areas. Numerous difficulties have had to be coped with – logistic (inadequate infrastructures and communication channels, areas that are inaccessible during the rainy season, etc.), social (difficulties arising in the reintegration of returnees into their communities of origin), and political (counterpressure exerted by the North and South Sudan authorities). When the Global Peace Agreement was signed in 2005, the displaced persons issue took on a new dimension as the displaced population that had settled in the North acquired new ‘political value’ in view of several approaching deadlines. The 2008 census is to be taken as the basis for distributing resources between the regions, and in the referendum that is scheduled for 2011 the people of South Sudan will be called upon to decide between a united Sudan and independence for the South. In this context, the numerical weight of displaced people living in the North, as in Khartoum, for example, is an asset for the regions of the North, since the budgets they will be allocated will be calculated accordingly. As for the 2011 referendum, the displaced South Sudanese are more likely to opt for a united Sudan if they are living in the North than if they return to the South. Since the voting procedures for the referendum have not yet been decided, however, it is not yet certain that people from South Sudan who are living outside the South will be able to vote. These general policy issues are compounded by local considerations of a more individual nature. Displacement has brought upheaval for the sultans, the traditional political leaders whose legitimacy has been based on the tribal system and territorial affiliation. There are now at least three types of sultan in the displaced population in Khartoum: there are the traditional sultans who arrived in Khartoum with their villagers; then there are sultans who were appointed after their arrival in Khartoum and whose legitimacy can be based either on lineage or on the influence they have acquired as individuals; and there are other sultans who have been established and are paid by the government (or, to be more precise, by the ruling party, the NCP) and who enjoy much less support from the people but often have more influence due to their connections with the ruling party. In the case of the sultans who were appointed after arrival in Khartoum, return to the South jeopardizes their function: they are liable to lose recognition and thus be deposed. Pressure is thus exerted at many levels on the displaced people in Khartoum: by the government of South Sudan and the regional governors, who are doing their utmost to encourage them to return to the South, by the government of North Sudan, which often pursues an ambiguous policy on the displaced, marginalizing them and at the same time trying to settle them in the North, at least temporarily (and the process of legalizing districts and allocating plots of land is an extremely powerful tool in this context), and by the sultans, some of whom urge the people to return whilst others seek first to consolidate their foothold in the North before attempting any return to the South.

The displaced population is an uprooted population living in a no-man's land between war and peace, between here and there. As the result of violence and uprootedness, it is slipping into a new conditionFootnote 26 that seems to be never-ending. The Colombian approach, although in theory appropriate in all respects, traps displaced people in a separate status and does not seem to promote their reintegration into society; on the contrary, it keeps them on the fringe. The legal framework and the aid system have thus strayed off target, despite the continuing efforts of part of civil society. Displaced people are becoming entangled in demands and action to defend their rights, and opposition to the political authorities and the administration is becoming more firmly entrenched. In Sudan, the stigma and discrimination attached to displaced persons has become State policy. The political interest they are now arousing is an opportunity that brings the hope that the political actors will commit themselves to longer-term choices and solutions. However, in view of the highly strategic nature of the displaced population the situation is often analysed in political terms and it is difficult for the stances adopted to be neutral. When working with displaced persons, humanitarian actors are liable to see their neutrality rapidly compromised and are often caught up in internal political struggles against their will. It is not always desirable for these actors to take a stand, nor is such siding welcome, but the fact remains that they enter the arena of national politics. The displaced are indeed a nagging thorn.