A frequent theme in international relations (IR) theory is that foreign affairs is an amoral realm where everyday ethical norms know no place. Under anarchy, ethical considerations must be set aside because morality's restraints hinder the necessary pursuit of egoistic interests through the use of threats and violence. As Waltz explains, “A foreign policy based on this image of international relations is neither moral nor immoral but embodies merely a reasoned response to the world about us.”Footnote 1 Morgenthau calls this the “autonomy of the political sphere,” one in which there is no “relevance” or even “existence … of standards of thought other than the political one.”Footnote 2 Most identified with realism, “the idea that power politics are beyond the pale of morality is not new. Down through the centuries, Machiavelli and Machiavellianism have stood for a doctrine which places princes and sovereign states under the rule not of ordinary morality but of the ‘reason of state,’ considered an amoral principle peculiar to the realm of politics.”Footnote 3

Yet it is hardly only realism that explicitly maintains or implicitly accepts that the structural nature of the international system differentiates anarchic international politics from interpersonal interactions within well-organized societies in a way that makes morality irrelevant to foreign affairs. Despite their origins in a critique of neorealism, rationalist treatments of cooperation, for instance, strip out the moral nature of reciprocity, thereby perpetuating (perhaps inadvertently) the notion of the autonomous sphere.Footnote 4

Many empirical studies, particularly the first generation of the “norms” literature, aim to counter this great truism by documenting moral progress over time. Elites and national publics demonstrate increasing concern for the fate of others beyond their borders, as evident in such phenomena as international criminal tribunals, foreign aid, decolonization, and human rights treaties. Yet, despite their differences, both optimists and pessimists rely on the same conception of morality: a liberal and cosmopolitan standard in which ethical action demonstrates universal concern for individuals regardless of national origin.

The focus on cosmopolitan humanitarianism obscures the totality of morality in international politics, leaving the empirical study of morality in IR with two central blind spots. First, it focuses on moral conscience—our desire to do good for others—to the neglect of moral condemnation, our response to the perceived unethical behavior of others, not only against third parties but also against ourselves. Morality always serves to restrain excessive egoism—that is, make us good—but how do we respond when others act badly? In both everyday life and in IR, the response is generally to morally condemn, and often to punish and retaliate. Second, the IR ethics and morality literature has not come to terms with moral principles that operate at the group level, binding groups together. When “our” group is engaged in conflict with another, we owe the group our loyalty and defer to group authorities out of moral obligation. These “binding foundations” are particularly important for IR since foreign affairs are a matter of intergroup interaction. These two fundamental moral impulses are related. Groups, bound by moral commitment, do not compete with others in an amoral sphere in which ethics stops at the water's edge. Rather, they project moral expectations onto interactions with other groups, judging and condemning other groups according to similar ethical benchmarks.

Once we cast our moral net more widely, we realize that morality is everywhere, more striking in the breach than the observance. There is a reason for this ubiquity. Evolutionary psychologists have long maintained that humans' moral sense is essential to their success as a species and part of what makes humans unique among animals. Moral systems have functional roots, helping individual organisms survive, thrive, and pass on their genetic material. As De Waal writes, “Given the universality of moral systems, the tendency to develop and enforce them must be an integral part of human nature … Any theory of human behavior that does not take morality 100 percent seriously is bound to fall by the wayside.”Footnote 5 We believe that liberal moral progress is real but that it accounts for only a part of the story about morality in IR, describing how the world has become differently moral rather than more moral. Evolutionary theory is not new to international relations,Footnote 6 owing mostly to the pioneering work of Rose McDermott.Footnote 7 Yet, with an important exception,Footnote 8 morality barely features in these IR accounts, and some imply that it plays no role at all.Footnote 9

Evolutionary theorists identify moral condemnation and binding morality as crucial for the emergence of other-regarding, altruistic behavior that makes liberal morality possible in the first place. Moral condemnation makes the world safe for altruism. When others harm us, or even third parties, we condemn, passing moral judgments and sometimes retaliating; we do not speak evil but speak of evil. Moral condemnation encouraged the development of moral conscience to avoid the outrage of, and often violent group punishment by, those who were wronged. This internalized sense of right and wrong in turn acted as a credible signal of cooperativeness that unwittingly and unconsciously paid material dividends and promoted, rather than detracted from, fitness. The presence of conscience allows individuals to use morality as a marker—indeed, the most important factor—by which to judge whether others are threatening. To help themselves, individuals see evil, forming moral judgments of others. We call this “moral screening.” Group favoritism, also thought to have evolutionary origins, is moral in nature as well. Those early humans who felt obligated to contribute to the collective defense against common threats in an extremely dangerous environment could prosper to such a degree as to offset the competing incentives to free ride within the group.

Of course, moral condemnation and punishment do not fully elicit moral behavior, or there would no longer be any use for moral condemnation. However, even egoists must operate under the shadow of morality to avoid the outrage of others. There are strong incentives for egoists to mimic the behavior of conscience-driven individuals.

Evolutionary theorists agree that morality originated under conditions of anarchy precisely because of its adaptive function in promoting material well-being; evolution selected for morality, a case of “first image reversed” causation.Footnote 10 It is not despite anarchy but because of anarchy that humans have an ethical sense. Therefore, there can be no amoral “autonomy of the political sphere.” Our article seeks to push evolutionary theory and its implications more into the IR mainstream.Footnote 11

How do we define observable implications that can be empirically tested, especially since the evolutionary process is not directly observable? Since anarchy “caused” the development of morality, there is no reason to believe that morality operates in profoundly different ways in international, rather than interpersonal, relations. We should therefore observe parallels between the moral dynamics that occur between individuals (as grounded in evolutionary thought) and those that occur between states. Though not possible to directly observe, the more universal they are—across different cultural and non-Western national contexts, at different levels of analysis, and in political and nonpolitical environments—the stronger the claim that they have a basis in human evolution.

The first implication of our argument is that it is almost impossible to talk about threat and harm without invoking morality. We turn to a corpus of leader speeches in the United Nations,Footnote 12 as well as internal, private documents from the Foreign Relations of the United States collection, to show that state elites do not speak of harm and threat in a nonchalant, phlegmatic manner—even in private and away from the eyes of audiences that might induce moral mimicry—since both are inherently moralized. We use word embeddings to show that utterances of harm and threat have a consistent, negative moral valence. We find the same patterns in a massive, nonpolitical corpus of quotidian human text,Footnote 13 which demonstrates the ubiquity of these phenomena. This suggests that international politics do not form a separate sphere of human interaction. When humans discuss threat and harm, whether in intergroup or interpersonal contexts, they speak evil in very similar ways, not in the sense of doing harm through words but speaking out against immoral action.

The second concrete implication of our argument is that individuals will use moral judgments as a basis, indeed the most important factor, for assessing international threat, just as research shows they do at the interpersonal level. Evolutionary theory tells us that perceptions of moral conscience act as a screening device, since such distinctions were crucial for early success. Humans learned to see evil. A survey experiment of the Russian public shows that moral attributes provide the most important basis for threat assessments of other individuals and other states in virtually indistinguishable ways. Supplementary surveys of the Chinese public (in the online supplement) reveal the same pattern, showing that moral inferences about the United States strongly predict threat assessments.

The third implication is that foreign policy driven by a conception of the world as an amoral realm will be extremely rare. We show that Hitler was such an example, but that this exception to the rule proves our point. The Nazi leader believed that there was no such thing as ethics, only material struggle, which differentiated him from right-wing counterparts driven by a sense of injustice and grievance (i.e., moral condemnation of historical adversaries) that Hitler privately scorned. However, our argument also implies that morality will cast a shadow on all human behavior, even in an anarchic realm, given the presence of judging audiences. We show that even this most totalitarian of dictators felt the need to conceal his amoralism from audiences both foreign and domestic as he came to power.

Drawing largely on moral psychology, we first draw out the common humanitarian (and generally liberal) benchmark for morality in the field, contrasting this with moral condemnation and binding morality. We then offer an introduction to the findings of evolutionary theorists on morality, particularly how condemnation and group morality are crucial for the development of altruism in the first place. We delineate how our approach to morality differs from other approaches in the discipline, before presenting three empirical tests of the argument.

Right and Wronged in International Relations

All ethical principles place limitations on excessive self-interest and encourage other-regarding behavior based on a sense of right and wrong. To which others we owe these sacrifices and which behaviors are prescribed and proscribed varies across different conceptions of good and bad, of which there are of course many. We rely on a definition of morality as “interlocking sets of values, practices, institutions, and evolved psychological mechanisms that work together to suppress or regulate selfishness and make social life possible.”Footnote 14

The most obvious, and likely most universal, understanding of morality is demonstrating concern for others' welfare, particularly those most in need, such as the sick or weak.Footnote 15 Humans have obligations to avoid harm to, but also to care for, others. For this reason, Haidt calls this moral foundation “harm/care.”Footnote 16 The caring principle, whose manifestations include charity, benevolence, and generosity, is altruistic. Altruism is such a fundamental ethical value as to be equated with morality in much of the scientific literature, synonymous with being humane and thus a part of our very essence as humans.Footnote 17 Altruism and caring are predicated on the belief that others are deserving of our concern. They have inherent value. Western (but not solely Western) societies go so far as to declare that all individuals are (at least in principle) fundamentally equal, and as such, entitled to certain inalienable rights.Footnote 18 This is liberal morality, in the classical and individualist sense. While not identical, since altruism is often paternalist and hierarchical,Footnote 19 the ethical principles of altruism and equality nevertheless share a similarity. Individuals, whether equal or not, are the fundamental units of moral value and the locus of ethical concern.

The positive (as opposed to normative) literature on morality in IR rests on this altruistic and egalitarian conception as the benchmark by which to empirically establish moral progress. Whereas the harm/care principle in our daily lives manifests itself in our donations to charity or costly acts of generosity, in IR it is evident in efforts by states and nonstate actors to help those beyond our national borders.Footnote 20 Most of the notable contributions in the “norms” literature, the most prominent body of positive research on international morality, document humanitarian phenomena.Footnote 21 Norms (e.g., caring for the wounded on the battlefield) are specific rules that grow out of more fundamental moral principles (e.g., caring for others). Moral progress in the norms literature is not only altruistic and humanitarian but also liberal and cosmopolitan, based on commitment to fundamental equality for all individuals.Footnote 22 This is also the standard for “just war” in recent empirical analyses of public opinion on jus in bello.Footnote 23

More to Mores: Alternatives to Liberal Ethics

Although caring is undoubtedly moral and a principle that has seen increased application beyond the water's edge, there are important, equally universal, moral principles that we have largely ignored in IR, leading us to vastly underestimate morality's ubiquity in international politics. If morality is more than caring for others, what else constitutes ethical behavior? The empirical study of moral psychology suggests two strong candidates for other universal ethical principles: (1) the phenomenon of moralistic condemnation and punishment, evident in such practices as retaliation, revenge, negative reciprocity, and the pursuit of justice against immoral others; and (2) the group-based morality that Haidt calls the “binding” foundations.Footnote 24

As a general principle, neither altruistic nor individualistic conceptions of ethics provide guidance on a central moral question: what do we do when others behave in an overly selfish (and thereby immoral) manner, disregarding the interests of others and ourselves? In this vein, Price laments, “There is little satisfactory engagement with the problem of whether and how to deal ethically with the ubiquity of ruthlessly instrumental actors … What does one do in a situation—indeed, in a world—confronted constantly with agents who do not approach a negotiation or a crisis with the characteristics of the ethical encounter entailed in a dialogic ethic?”Footnote 25 However, what for Price (and many liberally minded individuals, like ourselves) is a normative challenge, is not so for many in the real world. When others act excessively egoistically, they retaliate. In IR, states literally fight fire with fire. Retaliation of this kind is as universal an ethical principle as caring for others. This retaliation against unethical actions can take many forms, such as social ostracism or the levying of symbolic or material fines. Most dramatically, though, it can justify violence in the eyes of the aggrieved,Footnote 26 what is called “virtuous violence,” a growing focus in psychology.Footnote 27

DeScoli and Kurzban distinguish between moral conscience and moral condemnation.Footnote 28 The former is the little voice in our heads and the feeling in our hearts that tells us to do the right thing by restraining our most selfish impulses. The latter is the outrage and opprobrium with which we react to those who do not demonstrate such a concern for our or others' interests when they steal, cheat, or freeload. It is the response to a lack of moral conscience. Moral condemnation has two components; it is the use of “moral concepts to judge and punish a perpetrator.”Footnote 29 Moral condemnation encourages other-regarding behavior through external enforcement rather than an internal ethical compass but is predicated on the same conception of immoral behavior found in the harm/care foundation: excessive self-concern to the detriment of others. Moral condemnation shifts our attention from what makes humans do good to how they respond to bad, from doing right to righting wrongs.

If morality exclusively meant caring for others, moral condemnation and punishment would be unethical.Footnote 30 Yet, this does not square with our common-sense notion that we are justified in defending our interests against the selfish assertions of others. The moral condemnation that accompanies physical aggression is evident in that most fundamental of norms: self-defense against threats.Footnote 31 This understanding is at the heart of just war theory.Footnote 32

The norms literature in IR focuses mostly on the development of a cosmopolitan moral conscience, asking whether it is possible for state leaders to restrict their self-interest to serve the common good.Footnote 33 This literature has integrated moral condemnation into its accounts, most notably in the “naming and shaming” literature. However, it is largely preoccupied with the enforcement of cosmopolitan and liberal values, such as human rights, beyond national borders—in other words, condemnation, stigmatization, and ostracism for a lack of cosmopolitan commitment to international norms.Footnote 34 If genuine, this is purely altruistic moral condemnation. A second generation of norms scholarship, considerably less liberal in its orientation, details how the targets of criticism strategically contest moral condemnation by arguing like lawyers, exploiting loopholes and alternative interpretations of norms to cast their behavior in a better light.Footnote 35

While important, moral outrage and retaliation also accompany perceived infringements on our own interests,Footnote 36 not just those of others, what Welch calls the “justice motive.”Footnote 37 As Stein explains it, moral condemnation like revenge is “self-help justice,” what humans rely on to punish others for excessive egoism in the absence of (or in lieu of) the impartial justice provided by institutions.Footnote 38 If we focus too narrowly on cosmopolitan moral condemnation, we miss the iceberg of morality underneath the surface, even more so when we realize that national identification itself is for many a moral value. We seek to complement findings about when states do right with findings about what states do when others do them wrong.

For King and Country: Binding Moral Foundations and the Ethics of Community

Liberal morality is individual morality, but binding morality is group morality,Footnote 39 an understanding of right and wrong based on an “ethics of community.”Footnote 40 Morality involves repressing individual wants and desires in service of a specific group. This is a more “traditional” and “conservative” understanding of morality.Footnote 41 The ethics of community come with two moral imperatives relevant for IR: respect for authority and loyalty to the in-group. Both involve the regulation of selfish interests, just like altruism, egalitarianism, or any other moral value. However, they do so differently. Authoritarian morality requires obedience, subordination of the self to the command of others. It is wrong to defy the orders of one's father, one's church, or one's government. It is right to know one's place and role and to do one's bit for the community. Binding morality is hierarchical rather than egalitarian.

In-group loyalty demands that we favor our group over others. To do otherwise is to betray those in our community, a powerful moral indictment of excessive egoism. Humans have a particular vocabulary for the violation of binding morality; betrayal is a particularly grave sin. In the modern intergroup context of IR, it is treason. Binding morality makes it possible for us to think of groups as quasi-persons with their own interests and attributes. This phenomenon, called “entitativity”Footnote 42 or “anthropomorphization,”Footnote 43 is observable in the phenomenon of stereotypes.Footnote 44 Loyalty will manifest itself in a strong feeling of national identity. We might conceive of loyalty as a costly type of identification with a group. Loyalty implies a temptation to defect to serve one's own interest. Without loyalty, the national identification that marks group relations in modern IR will have little effect. Wearing one's home-country jersey during the World Cup is not the same as fighting on the front under the national flag.

The moral nature of national loyalty and authority deference often goes overlooked in liberal scholarship on morality because it entails the subordination of individual rights, the foundation of moral value in Western thought, to group welfare and group hierarchies. Liberal normative theory uses an “impartialist” perspective to derive ethical principles, making it skeptical of special obligations to specific in-groups.Footnote 45

Second-Order Moral Beliefs and Welfare Trade-Off Ratios: Linking Humanitarian and Binding Ethics

Binding morality draws heavily on second-order ethical beliefs, beliefs about the morality of others. The binding foundations are rooted in an essentialist view of the world as a dangerous place in which those lacking moral virtue wish to do the “good” members of society harm.Footnote 46 In Janoff-Bulman's terms, the ethical motivations of charity, benevolence, and altruism are about providing, whereas the ethics of community are about protecting from those who do not take our welfare into account—in other words, those who are not constrained by the harm/care foundation.Footnote 47 Studies show that in intergroup conflicts, out-groups are criticized for violations of harm/care and fairness principles, not binding foundations, since the latter are internal to the group.Footnote 48 It makes little sense to accuse our adversaries of disloyalty to us. This allows the same interpersonal dynamics of moral condemnation to occur between groups.

If there were no moral condemnation between groups, then binding morality would be the attractive force holding the atoms of the billiard ball together, but the interactions of those billiard balls would take place in an amoral sphere of the kind often assumed in IR. Ethics would stop at the water's edge, a situation of pure out-group indifference. However, to morally condemn those in other nation-states or countries for their actions toward our group requires that the condemner believes there is something more to morality than the binding foundations; there must be moral expectations for how those outside our borders treat us. We need both moral condemnation and binding morality to understand the ethical dynamics of IR.

Yet, what remains unclear is the extent of self-interest by others that will trigger our moral outrage, inducing and justifying concern for our in-groups at the expense of out-groups. These seem to have the common denominator of indicating a low “welfare trade-off ratio” (WTR), “the ratio of values below which an individual will tradeoff [sic] another's welfare for their own benefit in any conflict of interests.”Footnote 49 As shown to operate intuitively in human beings, a WTR of 0 indicates that I will impose a cost of any size on you to obtain any benefit at all, whereas an altruist will have a ratio of infinity, willing to bear any cost for even the tiniest benefit to the other. With the gain to others in the numerator and oneself (or one's group) in the denominator, anything less than 1 indicates selfishness. In an amoral sphere of politics, all would have a WTR of 0. Empirically, Sell finds that our anger increases as a function of how skewed others' ratios are, although we automatically take into account other factors as well, such as physical formidability.Footnote 50 This anger is meant to force others to revise their WTR in our favor. In the domain of IR, these are the instances where we most expect a tension between binding and humanitarian morality. Grounded in evolutionary theory, the WTR concept explains why human beings so universally condemn unprovoked physical harm (since we value our physical security so highly) as well as why human beings respond so negatively to unfairness and inequality (since it indicates a WTR of less than 1).

Morality Is What Anarchy Makes of It: Evolution, Ethics, and International Relations

Moral condemnation, the binding foundations, and altruism are so universal that there is now a strong consensus among evolutionary biologists that they all emerged through a process of selection as a way to promote the survival of individuals' genetic material. Morality creates bonds and regulates disputes, allowing greater cooperation among individuals, which improves their (or their close kin's) chances of survival. Simply put, without morality, we cannot explain human success.

There are two primary reasons for believing that morality has a material foundation. The first is its universality.Footnote 51 We can always find immoral individuals, and there is significant cultural variation in what constitutes right and wrong. Yet, despite these individual-level and intergroup differences, we cannot find any human society, historical or contemporary, devoid of ethics, and there is a significant degree of fundamental similarity.Footnote 52 The second reason is that “the building blocks of human morality are emotional.”Footnote 53 When something is right or wrong, we literally feel it, and those feelings motivate us to act.Footnote 54 Since moral judgments are accompanied by physical sensations and feelings, which are the realm of biology, and evolution is our best explanation of biological design, it stands to reason that morality has evolutionary origins.

Evolutionary accounts are functional in character. If morality has a biological foundation, it must have played a role in helping humans deal with the “adaptive problems” of their early environment: that is, “any challenge, threat, or opportunity faced by an organism in its environment that is evolutionarily recurrent … and affects reproductive success.”Footnote 55 This creates a puzzle, however. If morality is a set of feelings about right and wrong that suppress selfish desires, how can moral concern for anyone beyond our immediate family be anything other than dangerous for our genes and therefore a mutation destined to disappear in competition with others who do not have this sense?Footnote 56 The key insight is that human beings are of little use, and generally in greater danger, when they are on their own.Footnote 57 Evolutionary scholars surmise that morality is a set of physiological and mental mechanisms arising from the need to cooperate to meet recurrent social challenges, such as protection against threats and the collection of food.Footnote 58

Condemnation Before Conscience

Cooperation is facilitated by a combination of moral conscience and moral condemnation. The former creates the impulse to aid others, the latter to punish excessively egoistic actions. Unless it is accompanied by and coupled with moralistic punishment, moral concern of the harm/care variety is “genetically reckless” if “generosity extends beyond nepotism to nonkin.”Footnote 59 With it, humans can reap the gains from conditional cooperation and dominate the planet. As De Waal writes, “Reciprocity can exist without morality; there can be no morality without reciprocity.”Footnote 60

In evolutionary theory, we are led toward moral condemnation and punishment not by a conscious strategy of inducing better behavior for self-interested purposes by investing in reputation, as is the case in rationalist deterrence theory, but rather by a sense of moral indignation and outrage.Footnote 61 Moral condemnation is emotional and automatic for a reason: it is to our evolutionary advantage. Our threats are more credible, and more likely to serve as a deterrent, if they are automatic and therefore difficult to fake and control.Footnote 62 Anger is the ultimate costly signal. While it is difficult to distinguish automatic from deliberative behavior in IR, in which interactions tend to be iterated, behavioral economists have shown that in single-shot interactions such as ultimatum games, players will punish those who take advantage of them, even if it comes at a personal cost that leaves them worse off.Footnote 63 This explains the importance of fairness in bargaining outcomes, something observed in IR.Footnote 64 The universality of such findings across cultures suggests an evolved mechanism that likely served self-interest unconsciously in our evolutionary past. As mentioned before, empirical studies show that anger is proportional to the degree to which others indicate a low WTR.

Moral condemnation is so important that evolutionary thinkers argue that moral conscience could not have developed without it and likely developed because of it.Footnote 65 In the absence of moralistic punishment, having a conscience would not be fitness enhancing. Scholars argue that conscience is an evolutionary adaptation to the threat of moralistic punishment, particularly group punishment that anthropological evidence indicates was likely quite violent; indeed it must have been to select for moral self-restraint.Footnote 66 Conscience leads us to physically internalize a commitment to moral norm adherence so as to avoid the moral condemnation of others. Our conscience acts as an intuitive, but unconscious, reputation monitor.Footnote 67 To avoid moral condemnation and punishment, the evolutionary pressure is not only to act altruistically but to actually be altruistic—that is, to take the welfare of others into account, at least to some nontrivial degree.

But moral conscience does not only keep you out of trouble. It also opens up opportunities by signaling that you are a reliable partner, to those with whom you are directly interacting but also to others observing (or hearing about) your actions,Footnote 68 what Alexander calls “indirect reciprocity.”Footnote 69 Armed with the knowledge that an ethical compass is not situational but rather an attribute that some have and others do not, we will be looking for good partners who derive pleasure from acting morally.Footnote 70 This same pressure creates the evolutionary incentive to engage in costly third-party, “altruistic” punishment, coming to the defense of others.Footnote 71 Precisely because of the punisher's lack of direct stakes in the outcome, third-party punishment is a particularly costly signal of moral type.

It is this internalized sense of the need to do the right thing, guided by our emotional intuitions, that distinguishes an evolutionary account from a standard rationalist theory of cooperation in IR, for instance in neoliberal accounts. Keohane,Footnote 72 who drew on Axelrod's contributions to IR,Footnote 73 explicitly seeks to examine the extent to which self-interest based on reciprocity can induce cooperation without introducing moral obligation, which he layers on only in a concluding chapter. Our moral sense of conscience does not act on the basis of calculated and self-conscious self-interest and would not be nearly as effective if it did, since dispositional tendencies toward taking others' welfare into account are more credible signals of cooperativeness. Our conscience is our “selfish genes” acting without our knowledge.Footnote 74

Neural studies show that reciprocating cooperation in a prisoner's dilemma is associated with consistent activation in brain areas linked with reward processing. Reciprocity feels better than cheating.Footnote 75 The same is true of participation in third-party punishment, which is of great importance for explaining the origins and maintenance of cooperation in large groups, where the problem of policing bad behavior becomes particularly difficult because the mechanisms of repeated games and reputation no longer function as effectively. Moral condemnation and punishment on behalf of others, which are hard to account for in a rationalist framework, actually activate pleasure centers in our brain.Footnote 76

With conscience and condemnation in place, the stage is set for much more extensive diffuse reciprocity that sustains human societies, which, as Rathbun argues, cannot be explained with rationalist concepts.Footnote 77 This requires “moralistic trust,” the belief that others are inherently trustworthy and good, as opposed to “strategic trust,” a belief that a specific other has a self-interest in cooperating.

Moral Screening Before Audiences

These evolutionary pressures explain why morality is the key attribute we use in forming impressions of others, more so than other attributes like warmth or competence.Footnote 78 Humans are on the lookout for those who do good and punish bad relatively indiscriminately, as a general rule of right and wrong.Footnote 79 Brambilla and colleagues write, “These findings might be interpreted from a functionalist perspective. Indeed, knowing another's intentions for good or ill … turns out to be essential for survival even more than knowing whether a person can act on those intentions.”Footnote 80 Whether someone is honest and fair is more important to our safety and prosperity than if they are funny or polite.Footnote 81

Of course, there are both (relatively) moral and immoral humans. However, the phenomenon of moral condemnation means pure egoists act under the “shadow of morality.” They must at least mimic the behavior of their moral counterparts to avoid moral judgment. Humans universally gossip, another phenomenon linked to the evolution of morality. We trade reputational information about who is dangerous and who is not, who can be trusted and who cannot.Footnote 82 For this reason, “the conscious pursuit of self-interest is incompatible with its attainment … Someone who always pursues self-interest is doomed to fail.”Footnote 83 Ridley writes that moral hypocrisy should not make us skeptical of moral power: “Even if you dismiss charitable giving as ultimately selfish—saying that people only give to charity in order to enhance their reputations—you still do not solve the problem because you then have to explain why it does enhance their reputations … We are immersed so deeply in a sea of moral assumptions that it takes an effort to imagine a world without them.”Footnote 84

Evolution of Group Morality: War Made Man and Man Made War

Just as moralistic punishment is a universal phenomenon, suggesting an evolutionary origin, so too is the human tendency to join groups and favor insiders over outsiders. If the binding foundations have evolutionary origins, then they must also have helped humans solve recurrent challenges in their ancestral past, offering fitness advantages. Yet, why would parochial altruism have emerged as a moral impulse separate from more generic altruism? Evolutionary scholars have provided two answers, both of which likely contribute to the ethics of community.

First, in-group favoritism emerges as a solution to the problems of morally policing opportunism. By confining their altruism to smaller groups, individuals run less risk of exploitation.Footnote 85 Second, intergroup competition of the kind that our early ancestors encountered would also promote binding morality. Human beings face not only the dangers of cheating from within but also the threat of physical aggression from without. When engaged in struggles over material resources, groups and individuals will do better vis-à-vis other groups if they are loyal rather than universally altruistic or entirely selfish.Footnote 86 At the individual level, the reputation benefits of being loyal would be particularly high in situations of great threat, working against the temptation to free ride. Those who avoided the temptation to figuratively dodge the draft likely also reaped gains that would have encouraged the biological evolution of in-group loyalty and deference to authority.Footnote 87 “Multilevel” evolutionary theorists argue that when group extinction was possible, even small advantages in the proportion of parochial altruists in a group might have been decisive in intergroup conflict with survival stakes, allowing the benefits of cooperation to outrun the strong “within-group” pressure to free ride.Footnote 88 Some go so far as to argue that we cannot explain the origins of altruism without war, a seeming paradox, particularly for liberals.Footnote 89

It must be stressed that what makes human beings unique is that they extend their sense of group loyalty beyond the kin group. How this identification of the group works is a matter of fierce debate among evolutionary scholars. Some argue that early humans had so little contact with others who were not related to them that they are preprogrammed to assume that everyone immediately around them is a relative, while others attribute most of the work to culture (which we think is more likely).Footnote 90 Whether human beings exhibit in-group loyalty innately, and are capable of defining groups in any number of ways, is not in dispute, however. And, as an evolutionary adaptation to early ancestral challenges, in-group loyalty is entirely capable of persisting beyond the point at which it offers a fitness advantage, since our social environment can change faster than our biology adapts. Even though few of us face existential pressures in the same way as our ancestors, we still might automatically act as if we do.

Making the Private Public: The Implications for International Relations

All of this research indicates that moral psychology is an evolved mechanism for coping with anarchy, not a luxury we enjoy only once we have transcended it. The Pleistocene era in which these traits evolved looked much like the anarchy described in theory by security scholars.Footnote 91 Evolutionary psychologists therefore offer the basis for what Kertzer and Tingley call a “first image reversed” argument, which “inverts the analytic focus of the subfield from micro-micro causation to macro-micro causation: from the effects of actor-level characteristics or individual differences on attitudes and behaviors, to the effects of environmental forces on actor-level characteristics.”Footnote 92

Since morality is an intrinsic part of the human experience (and the human body), there is no realm of human interaction where morality is absent. In classical realist terminology, there is no separation between public and private morality. Indeed, many classical realists had this realization.Footnote 93 Morgenthau observes of the public/private distinction, “The importance of this conception has been literary rather than practical. Mankind has at all times refused to forego the ethical evaluation of political action … Whatever some philosophers may have asserted about the amorality of political action, philosophic tradition, historic judgment and public opinion alike refuse to withhold ethical valuation from the political sphere.”Footnote 94 It is not just that state leaders have a duty to protect others in their community. Morgenthau rejects such a “dual morality”—that “which would make you a scoundrel and a criminal there [in private life] would make you a hero and a statesman here”—because it limits ethical concern to the in-group and would morally excuse the autonomy of the political sphere.Footnote 95 Rather, the nature of IR more often presents leaders with irreconcilable trade-offs they cannot avoid, generally between their state's interest and those outside. It is precisely because there is no amoral sphere that these thinkers advocate a “consequentialist logic” as the normative standard for good foreign policy. If there were no moral concern for those outside our borders, we would not have to justify the use of violence by reference to the consequences of its use for the greater good, something typically missed in uses of the term in the field.Footnote 96

Yet this notion of the autonomous sphere is still common among realists and, largely implicitly, in rationalist approaches that use elements central to evolutionary theory (such as reciprocity, deterrence, and reputation), while stripping them of their moral content. Cooperation among pure egoists, even if mutually beneficial, is still amoral if they treat one another as mere means to an end and respond to ill treatment by others phlegmatically, without moral outrage. Rationalism's inattention to ethics is evident in the way in which theorists scrub the inherent morality from concepts through language. Freeloading becomes “free riding.” Cheating becomes “defection.” Lying becomes “dissembling.” Aggressors are “revisionist.” Whereas structural realists sometimes explicitly disavow the moralized nature of international politics, rationalists de-moralize it by avoidance or inattention. Even constructivists, to the extent that they believe that liberal progress constitutes a move from amorality to morality, tacitly endorse such a position.

Still, the evolutionary position is neither deterministic nor incompatible with a constructivist position focused on the importance of social influences. While evolutionary theorists identify an underlying materialist basis for ethics, social factors are crucial in three ways. First, they determine the relative weighting of different moral principles when in conflict, explaining variation across individuals, places, and times. Second, social influences translate moral principles into discrete norms of behavior, telling us what is appropriate given what we believe to be right.Footnote 97 “These [moral] sentiments,” writes Frank, “are almost surely not inherited in any very specific form. Definitions of honesty, notions of fairness, even the conditions that trigger anger, all differ widely from culture to culture.”Footnote 98 The principles, or moral foundations, are roughly similar across societies. Yet, the application of those principles and their operationalization in a given time and place in the form of specific behavioral injunctions vary. Our biology gives us a moral menu, not a moral map. Third, culture and social processes are responsible for creating unique combinations of those items on the menu, combinations that are not inherent in human nature, as in ethical systems such as socialism or liberalism. While according to research deference to authority and in-group loyalty have a natural tendency to cluster, societies might nevertheless demonstrate strong in-group solidarity and be largely egalitarian. Similarly, we can be altruistic without being egalitarian; we know this as paternalism, which differs from liberalism.

However, we should not let this distract us from the universality of the foundational moral principles highlighted here.Footnote 99 Boehm writes that “even though certain types of moral belief can vary considerably (and sometimes dramatically) between cultures, all human groups frown on, make pronouncements against, and punish the following: murder, undue use of authority, cheating that harms group cooperation, major lying, theft and socially disruptive sexual behavior.”Footnote 100 This universality “is why, for all their superficial differences of language and custom, foreign cultures are still immediately comprehensible at the deeper level of motives, emotions and social habits,” writes Ridley.Footnote 101 An evolutionary approach that conceives of ethics as moral intuitions is different from constructivist accounts in that it does not think of humans as a largely blank slate. As it is for those who stress the logic of habit or internalized norms, moral sense is considered largely intuitive and nonrepresentational.Footnote 102 However, it is not produced solely by practice or socialization. “Our cultures are not random collections of arbitrary habits. They are canalized expressions of our instincts.”Footnote 103

Study 1: Morality and Threat in Human and Political Speech

Our argument implies that when humans, including the leaders of nation-states, talk about security, they cannot help talking about morality, since the evolution of ethics and humankind are interrelated. Harm done to others is morally condemned. Threats are judged through moral screening. Some of this is undoubtedly intentional; we castigate to create support for our cause, draw attention to our plight, and recruit allies. However, we suspect that much of this is also simply natural, unconscious, and intuitive, particularly in nonpolitical and private contexts not under the shadow of public morality. Scholars often use judgments reached intuitively as a window into our evolutionary past.Footnote 104

To investigate these expectations, we turn to text analysis. We first draw on 8,640 speeches, primarily by heads of state, during the annual United Nations General Debate (UNGD) from 1965 to 2018.Footnote 105 Second, we examine almost 16,000 private documents contained in the Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS) collection,Footnote 106 which represent internal diplomatic cables and communications curated by the State Department's historian's office for importance and frequently used in qualitative research.Footnote 107 Because our argument maintains that morality is a basic feature of international political life, we expect to see moralization of harm and threat in both public speeches and private communications. The UN corpus has the advantage of being truly global; FRUS serves as a more difficult test for our argument since it is private.

We locally train word embeddings on the texts using the Global Vectors for word representation (GloVe) model.Footnote 108 Word embeddings operationalize the intuition that we can know a word by the company it keeps. Embedding models take large inputs of digitized text and output an N-dimensional “vector space model” in which each corpus term is “ascribed a set of coordinates that fix its location in a geometric space in relation to every other word.”Footnote 109 Words that share many “contexts” are positioned “near one another, and words that inhabit different linguistic contexts are located farther apart.”Footnote 110

Word embeddings depart from count-based “bag of words” representations of textual data traditionally used in political science, which rely on frequencies of word occurrence. Word embeddings—or vector space representations of text—preserve far richer semantic context, providing unique leverage on the question of even implicit associations. For example, Kozlowski, Taddy, and Evans reveal gendered expectations about occupation.Footnote 111 “Engineer” appears in the same contexts as “his” and “man”; “nurse” appears in the same contexts as “her” and “woman.” For our purposes, comparisons of the vector space locations of harm, threat, and morality terms allow us to assess whether harm and morality, as well as threat and morality, really do go hand in hand in speech.

With the word embeddings in hand, we estimate the placement of moral terms on “harm” and “threat” dimensions. We take the average vector space locations of harm-related and threat-related words, and subtract off the average locations of harm and threat antonyms, respectively.Footnote 112 Continuing the Kozlowski, Taddy, and Evans example, the analytical intuition is that subtracting the location of “woman” from the location of “man” provides a “gender” dimension in vector space.Footnote 113 One can then use a similarity measure (here, cosine similarity) to project occupational terms like “engineer” onto this dimension. If those occupational terms tend to fall on one side of the male–female dimension, this reveals gendered associations with occupation.

For our purposes, if harm and threat are unrelated to morality, then our moral words will be orthogonal to the harm and threat dimensions. Harm and threat will be morally neutral, as we would expect if morality were removed from this sphere of human interaction. If humans instead make moral judgments about harm and threat, we expect that in each corpus negative moral terms will fall on the positive end of the harm and threat dimensions, while positive moral terms will fall on the negative end of the harm and threat dimensions.

In addition to our political corpora, we apply this same procedure to GloVe word vectors that were pretrained on a corpus of Wikipedia and Gigaword 5 data, with a total of 6 billion tokens and a 400,000-word vocabulary. These data represent encyclopedia entries and newswire texts, and thus quotidian, nonpolitical speech. Further, whereas stemming the terms in the political corpora appears to generally improve the quality of the embeddings, the size of the underlying GloVe corpus permits more precise identification of the full-length terms. Similar patterns to the political corpora would provide evidence that the political sphere is not autonomous but simply another realm of human activity, where morality functions similarly.

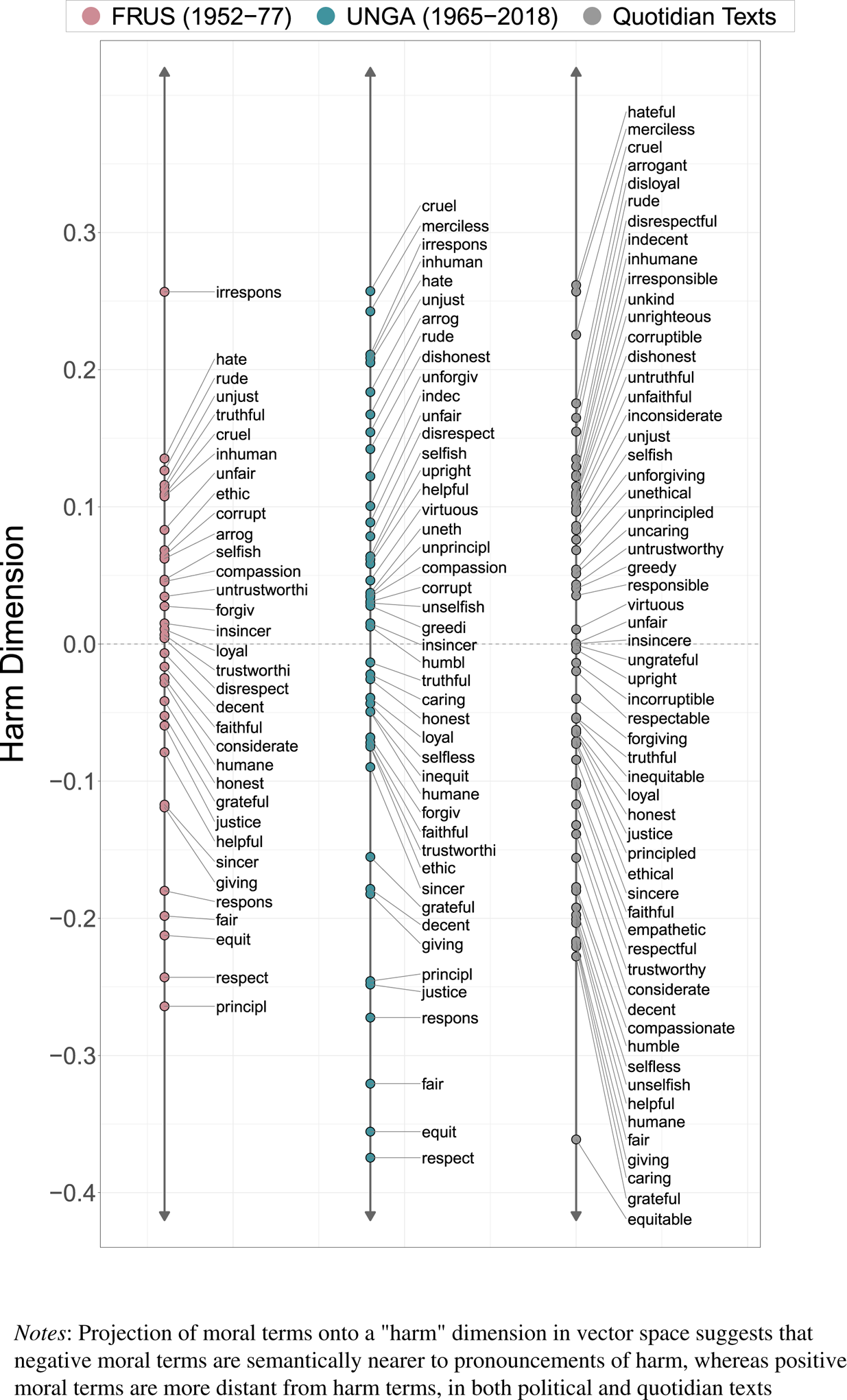

Figure 1 presents the harm results. Each moral word occupies a position that is nonorthogonal to the harm dimension, which suggests that “harm speech” contains moral content. Further, positively and negatively valenced moral words tend to cluster on opposite sides of the dimension, as expected. We note that only a subset of our moral dictionary appears in the political embeddings because the political corpora are much smaller than the corpus underlying the pretrained, quotidian texts. Thus, fewer moral terms appear on the dimensions using political texts. Figure 2 presents the threat results. Again, we find that each moral word occupies a position that is nonorthogonal to the threat dimension, with positively and negatively valenced morals clustering on opposite sides, which suggests that “threat speech” contains moral content. Overall, 87.8 percent and 81.3 percent of the moral terms fall on the expected sides of the harm and threat dimensions, respectively. These classification rates are surprisingly strong given the simplicity of the approach (namely, cosine similarities between word vectors), and comparable to the rates found in Kozlowski, Taddy, and Evans's gender, race, and class analyses.Footnote 114

FIGURE 1. Moralization of harm in political and quotidian texts

FIGURE 2. Moralization of threat in political and quotidian texts

Although these results display a strikingly clear pattern, we are cognizant of the smaller size of the political corpora and the fact that moral terms are used in several contexts, not only the context of harm and threat. Thus, to assess the robustness of the results, Appendix A.1.2 reports nonparametric confidence intervals for the political corpora, as well as a permutation test for the quotidian corpus. For the political corpora, 59.5 percent of the UNGD terms and 56 percent of the FRUS terms fall reliably far from zero. Notably, the similarity of these rates suggests that moralization of harm and threat occurs similarly in both public speeches and private communications. In the quotidian corpus, 59.3 percent of the moral terms significantly diverge from a null distribution. Importantly, we do not misclassify any of these more robust terms in the quotidian corpus and reliably misclassify only three terms in the political corpora (“virtuous” on the UNGD's harm dimension, “ethic” on the UNGD's threat dimension, and “honest” on the FRUS's threat dimension). These results increase our confidence that moral terms are surprisingly nonorthogonal to these dimensions.Footnote 115

In sum, harm and threat seem to be inherently moralized concepts regardless of the context. Whether it is masses or elites, in public or in private, makes little difference. In this way, the FRUS results are particularly striking in that these are records of private conversations among practitioners, away from the prying and judging eyes of the public.

Study 2: Moral Screening Survey

Our text analyses demonstrate the striking correspondence between threat, harm, and moral language in a real-word context encompassing a multitude of political actors over a significant period of time. However, this method does not provide the measurement precision that surveys permit, particularly regarding the importance of morality relative to other factors in judging threat. For this task, we turn to an experimental survey of a mass public. Given the centrality of audiences to the evolution of morality, these publics are more than a convenience sample. The crowd is a central part of the origins of these ethical phenomena. As discussed earlier, the evolutionary literature suggests that morality should be the most important characteristic by which individuals screen for threats from other individuals and groups, despite the different environments that mark interpersonal and international relations. This goes very much against the notion of an autonomous moral sphere in which moral considerations are absent.

In early March 2020, we surveyed 1,245 Russian respondents recruited through the survey firm Anketolog and chosen to create a sample similar to the general population in terms of age, gender, and region of residence.Footnote 116 We decided not to conduct the survey in the US since the American public is sometimes accused of moralizing conflicts in a way that is not true of other countries that have a more Realpolitik understanding of IR.Footnote 117 Our instrument was translated by a native speaker, piloted on a small sample for difficulties in comprehension, and also evaluated by another, nonnative, Russian speaker. Appendix A.2 includes sample demographics (compared to the national population) and instrumentation in both languages.

In a variant of previous research at the interpersonal level, we asked subjects to identify attributes of others that subjects deem most important in judging whether others might harm us (as opposed to merely an overall impression, the basis of previous research). Individuals were randomized into two conditions. In the interpersonal condition, they were asked to think about harm from other individuals; in the international condition, about harm from other countries. We gave respondents a list of the most important attributes identified in previous stereotype work,Footnote 118 including sociability, competence, and morality-related attributes, as well as attributes that IR scholars traditionally use as predictors of threat, such as power.Footnote 119 An English translation of the prompt is:

In [our lives / foreign policy], [we / our leaders] must form impressions of [others / other countries] and whether they might harm us or not. We never know for sure, but if you were asked to form a judgment about [someone / another country] and were offered reliable information about the following traits, which would you find to be most relevant and most important? In other words, which would you want to know?

Respondents were instructed to drag at least two attributes to a box to the right and rank them in importance.Footnote 120 This relatively inductive approach gave subjects the chance to “build your own threat” as it were, rather than simply asking them to identify whether a particular attribute is threatening or not.

Importantly, the country-versus-person randomization allows us to compare whether subjects' conceptions of threats differ between the individual and country levels, the latter being a type of group that has not been included in previous stereotype research. Our argument expects that morality will be the most important factor for the judgments of both individuals and countries because moral screening is an evolved mechanism individuals use to make threat assessments. Moreover, we do not expect large differences in the ordering of attributes across conditions, as one would if IR were morally autonomous, since we hypothesize that humans will make similar moral attributions across the individual and group levels.

Figure 3 reports the rank importance for individual and country threat traits, with D statistics and significance levels for each person-country distribution comparison shown in the top-right corner according to a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The figure presents traits in descending order of overall mean importance, with honesty/trustworthiness ranked first. The results are striking. First, the overall distributions are broadly similar, with very few statistically significant differences across treatments. This suggests that humans use morality to screen for threats, at both the interpersonal and international levels. Second, the moral attributes of honesty/trustworthiness and fair/just are by far the most important characteristics that individuals use to judge threats from both other individuals and other countries. Only two distributions significantly differ at the α = .05 level: as might be expected, subjects place more emphasis on intelligence when evaluating individuals and more emphasis on organization/competence when evaluating states.Footnote 121 Third, determinants of threat perception traditionally considered central to IR theory, such as power, resolve, and cultural similarity, lag significantly behind. Power and resolve are competence traits and, as psychological research suggests, are secondary in making judgments about others.

FIGURE 3. “Build a threat” results

Figure 3(B and C) present the trait co-occurrence networks for individual and country traits, respectively, with darker ties representing more frequent co-occurrences. These co-occurrences provide a sense of the composite threat images our respondents construct. The images are remarkably similar, underscoring our argument. Appendix A.3 presents supplementary survey evidence from the Chinese public, showing that moral judgments about the United States significantly explain respondents' perceptions of US threat.

One might question the relevance of the public for our argument. We would stress first that the public is a key audience before which political leaders, even self-interested ones, must act, such that our results elucidate the shadow of morality. Second, we believe, and our text analyses suggest, that the distinction between the psychology of masses and elites is overstated, as shown by others who are actually testing this well-worn conventional wisdom.Footnote 122 Of course, this is consistent with an evolutionary account, which stresses the commonalities across individuals given our common biological character, especially in situations, like threat, that most implicate and activate evolved mechanisms. However, to add further evidence to our case in the realm of real-world high politics, we turn to one of the most famous (and infamous) leaders of all time.

Study 3: A Qualitative Analysis of Hitler's Non-exception to the Rule

Adolf Hitler came closer than any other historical figure to a belief in the irrelevance of morality to IR, a belief he based on an (empirically refuted) understanding of the implications of biology for politics and IR as implying no room for morality, and not just humanitarian concern but also moral condemnation. The Hitler case, however, proves our point. Few would argue that the Nazis were not highly exceptional; yet arguments that presume an amoral realm of politics imply that figures like Hitler should be much more commonplace.

Hitler grounded his worldview in the crude (and indeterminate) evolutionary principles that humans have two primary drives, or “rulers of life”: hunger and love.Footnote 123 “While the satisfaction of eternal hunger guarantees self-preservation, the satisfaction of love assures the continuance of the race.”Footnote 124 While it is hard to deny the human urges to procreate and survive, the most important element of Hitler's worldview was his belief that these impulses inevitably lead to struggle—in German, Kampf.Footnote 125 In this way, Hitler thought, humans were no different than any other species, as much as they wanted to believe otherwise.Footnote 126 For Hitler, constant struggle occurred not only among humans and between humans and other species, but also between groups of humans organized as Völker, or peoples, which he interpreted in racial terms.Footnote 127

Since animals know no morality in their struggle for life, the basic moralities we found (earlier in the discussion) to be the basis of moral condemnation and screening were for Hitler merely social constructions, illusions men lived under to distract them from the brutal realities of life. “When the nations on this planet struggle for existence … then all considerations of humanitarianism or aesthetics crumble into nothingness; for all these concepts do not float about in the ether, they arise from men's imagination and are bound up with man. When he departs from this world, these concepts are again dissolved into nothingness, for Nature does not know them.”Footnote 128 For Hitler, there was only the right of the stronger (Recht des Stärkeren). Might makes right. Of course, Hitler's crude Darwinism was empirically false. It is the very material existence of ethical impulses that distinguishes humans from other animals and allows them to survive.

Since nature compels all peoples to seek territory for their nourishment, others could not be blamed for their use of force and coercion. Remarkably, Hitler expressed an understanding of the actions of Germany's most bitter enemies, the allies that had vanquished the country in the Great War, that we do not find in other rabid nationalists. Unburdened by ethics, Hitler did not have the same sense of righteous indignation vis-à-vis England and France. Hitler, for instance, believed Germany's bid for colonial territories and a greater portion of world trade during the Wilhelmine period, a strategy known as Weltpolitik, was responsible for English enmity. England had no choice but to fight. He wrote, “We must never apply our German sins of omission as a measure for judging the actions of others. The frivolousness with which post Bismarckian Germany allowed her position in terms of power politics to be threatened in Europe by France and Russia, without undertaking any serious countermeasures, far from allows us to impute similar neglect to other powers or to denounce them in moral indignation, if indeed they attend to the vital needs of their Folks better.”Footnote 129 He applied the same yardstick to English action as to German action. “England did not do this, because we were bellicose, but because we wanted to survive, and England also wanted to survive. Because now the competitive struggle came, decided not by right, but ultimately only power … We were beaten.”Footnote 130 By the same reasoning, Hitler did not condemn France: “Were I a Frenchman myself, and were France's greatness as dear to me as is Germany's sacred, then I could and would not act otherwise than Clemenceau himself did in the end.”Footnote 131 As Welch trenchantly notes, “For Hitler, neither Versailles nor the borders it established were unjust—they were merely unacceptable.”Footnote 132

Yet Hitler largely avoided expressing these views. His lack of interest in castigating enemies for their unjust treatment was actually politically untenable. To be successful in the ubiquitous shadow of morality, Hitler would have to hide his moral nihilism and engage in moral condemnation. No one, not even the Führer, could avoid its cast. Though Hitler did not blame the Versailles powers for their actions, he understood the indispensability of such a tool in building a mass movement. In recounting the early days of the Nazi movement, he notes how he focused in particular on the peace treaties. “Beginning with the ‘War Guilt,’ which at that time nobody bothered about, and the ‘Peace Treaties,’ nearly everything was used that seemed agitationally expedient or ideologically necessary.”Footnote 133 The truth of these claims, he argued, did not matter.

However, we see that even Hitler could not feel uninhibited in expressing his views. No one, even a craven totalitarian dictator with total control over his national populace, escapes the shadow of morality. Since morality is evolutionarily ingrained in humans through a process of moral judgment and condemnation, all will live under a shadow of morality, even those who entirely escape any moral inhibitions.

Hitler's use of moral indignation against the allies seems to explain his political success, not his amoral view of dog-eat-dog struggle or even his anti-Semitism. The Nazis' major breakthrough in national politics only came in 1930: a coalition with the more traditional German National People's Party (DNVP) in campaigning against the Young Plan, a renegotiation of German reparations obligations that presented another opportunity to make hay of Germany's poor treatment at the hands of its enemies in the war.Footnote 134 Following this breakthrough, in which the Nazi party became the second-largest party of the Reichstag, Hitler's materialist rhetoric about the right of the stronger almost entirely disappeared. In an analysis of searchable databases comprising two of the main compendia of Hitler's writings, speeches, and proclamations (Reden, Schriften, Anordnungen: Februar 1925 bis Januar 1933 and Reden und Proklamationen 1932–1945),Footnote 135 we searched for keywords indicative of his evolutionary views (listed in Appendix A.5). After the 1930 elections, Hitler never made a public speech outlining his racial and crude Darwinian views, even after he took power. We see no mention of natural selection in any public comments until 1943, as the war was turning against the Nazis.

Hitler seemed to understand that international audiences were morally screening because until the war began he used different “legitimation” strategies for his revisionist goals based on moral norms: self-determination and subsequently self-defense.Footnote 136 Even Hitler, perhaps the most immoral leader of all time, leading one of the most totalitarian states of all time, felt compelled to justify his foreign policy morally before domestic and foreign audiences.

Conclusion

A biological approach centered on morality improves upon several crude applications of Darwinism previously applied to IR, which make no mention of human beings' unique ethical sense.Footnote 137 Notably, Thayer argues that evolutionary theory provides microfoundations for classical realism's conception of human egoism and will to power and dominance—in other words, the autonomy of the political sphere.Footnote 138 However, human beings, as all evolutionary theorists stress, are no typical organism. No other organism extends generosity beyond immediate kin in the way humans do.Footnote 139 The world is indeed marked by the constant quest for material resources highlighted by Thayer, but humans have solved this problem, more often than not, by repressing selfish impulses rather than by sharpening them. Indeed, without morality the very groups that feature so centrally in realism could not have come to exist in the first place. In other words, no binding foundations, no nation-states. Thayer argues: “In times of danger or great stress, an organism usually places its life—its survival—before that of other members of its group, be it pack, herd, or tribe. For these reasons, egoistic behavior contributes to fitness.”Footnote 140 But if this is true, how can states act as egoistic actors at all?

Morality is not the transcendence of material reality; it is material reality. It helps us navigate adaptive challenges posed by our material environment—deterring threats, promoting cooperation, dividing resources—and is embodied in our physiology precisely for that purpose.Footnote 141 We hope that the normative and empirical advocates of liberal morality, among whom we include ourselves, recognize the normative promise (rather than threat) of a biological approach in grounding liberal morality on something other than just intersubjective understanding. Most of the norms literature is constructivist, where morality is whatever a community decides it is at any particular time. Yet, many have noted that such a position is ultimately akin to moral relativism, since morality in such a case lacks objective foundations.Footnote 142 Evolutionary theory tells us that such radical subjectivism is not necessary to explain morality. Any definition of right and wrong is not just as good or natural as any other. Group morality, the binding foundations, are a part of that, of course, creating fears of intractable group conflict. Yet, in-group love is not equivalent to out-group hate. A recent review of the literature concludes that “decades of research consistently revealed that variations in bias in intergroup perceptions, attitudes, and evaluations emerge because of variation in ingroup favoritism more than because of variations in outgroup derogation.”Footnote 143 There is (liberal) good, not just evil, to see in a biological account of ethics.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this article may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RZ1JVJ>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818321000436>.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathleen Powers and participants at the Ohio State University's Political Psychology Workshop for feedback. We are grateful to Azusa Katagiri and Eric Min for making their FRUS data available to us.