One of the most challenging developments in recent years for the Liberal International Order has been the growing popular backlash against international cooperation. In countries as diverse as Brazil, Britain, the Philippines, and the United States, citizens have voted politicians into office who campaigned on promises to withdraw from international institutions such the Paris climate agreement, the International Criminal Court (ICC), and the European Union (EU). Public opinion has become increasingly critical of individual international and supranational institutionsFootnote 1 such as trade institutions,Footnote 2 international courts,Footnote 3 and European institutions.Footnote 4 This popular opposition has been consequential in delaying and preventing the creation of new international institutions,Footnote 5 and has even led to withdrawals from existing institutions.Footnote 6 With mantras such as “America First” and “Take Back Control,” isolationism, nationalism, and protectionism are back on the political scene with a vengeance. Whereas a decade ago, a withdrawal of a member state from the EU or the unraveling of the World Trade Organization's (WTO) dispute settlement system seemed virtually impossible, this has now become reality. At the same time, there have also been vocal popular demands for more or continued institutionalized international cooperation, such as the “Remain” campaign in the United Kingdom or the worldwide climate youth movement, and confidence in international organizations (IOs), such as the United Nations, remains high.Footnote 7 In this article we explore when and how this domestic public contestation influences international cooperation.

Skepticism about the merits of international cooperation is nothing new, and countries’ national interest has always been at the heart of international politics. What is new, however, is the increasing politicization of international cooperation. The mass public has become increasingly aware of, mobilized, and polarized on issues surrounding globalization, international institutions, and the modes of foreign policymaking more generally.Footnote 8

These developments also pose a challenge for international relations research. Whereas traditional international relations research paid little attention to the role of the mass public,Footnote 9 recent work in the field has taken the influence of domestic public opinion in foreign policymaking much more seriously. Nonetheless, scholarship on international cooperation often makes simplifying assumptions about the public's underlying preferences. Audience cost theory, for example, assumes that policymakers can gauge the domestic price that a leader would pay for making foreign threats and then backing down,Footnote 10 and that such domestic constraints can therefore serve as a credibility-enhancing device in international negotiations.Footnote 11 Likewise, research on two-level games in international negotiations argues that governments can use voters’ preferences as a device to enhance their bargaining power.Footnote 12 These models presume that governments have a good understanding of how both their own and their opponent's domestic audiences would react to different foreign policy decisions.

At the same time, a large literature on individual preferences and political psychology in international relations demonstrates that gauging what the mass public wants is far from straightforward. Recent work shows considerable variation in public preferences for forms of international cooperation, such as international trade,Footnote 13 foreign direct investment,Footnote 14 foreign aid and global public goods provision,Footnote 15 international organizations (IOs),Footnote 16 and European integration.Footnote 17 And even when the public has clear preferences in foreign policymaking, they might not necessarily reveal these preferences by acting on them.Footnote 18 So, whereas existing work has generated important insights into who wants which kinds of policies and who is more open or opposed to international cooperation, our understanding of whether and how these preferences matter for foreign policymaking is much less developed.

We explore the causes and consequences of the politicization of international cooperation. Politicization refers to the process of making an issue political, that is, debating it in the public sphere as an issue of public contestation.Footnote 19 We argue that the mass public has become increasingly attentive to international issues and can constrain governments and international institutions. Some scholarship has suggested that this growing politicization is largely a function of the increasing authority of international institutions.Footnote 20 Yet, politicization differs across the member states that belong to the same international institutions. This raises questions about the possible causes and consequences of politicization. How does the growing politicization of foreign policy and international institutions, a polarization in public support for international cooperation, and the rise of nationalist parties change the role of the mass public in international relations? Why does the politicization of international cooperation differ not only across countries that are members of the same organization, but also within countries over time? And does the changing role of the mass public in international politics ultimately strengthen or weaken the stability of international institutions?

To answer these questions, we seek to bridge the gap between the international relations literature and the comparative politics literature on political behavior. By fusing insights from the study of opinion formation and party competition that explores how international issues become politicized domestically and the study of IOs, we develop a framework for understanding the politicization of international cooperation and the systemic implications for the depth and scope of international cooperation. We argue that in order to become politically consequential, two conditions must be met. First, international issues need to become publicly contested and politicized. There are two key elements that lead to a politicization of international cooperation: public discontent about existing forms of international cooperation—which requires both awareness and polarization of opinion—and the mobilization of this discontent by political entrepreneurs. Political entrepreneurs mobilize public opinion to their strategic advantage. In doing so, they tap into the pre-existing sources of discontent that are the most advantageous to politicize. Determining what is causally prior—public discontent or political mobilization—is difficult because they reinforce each other. What is important is that both conditions are met.

Second, for public contestation to present a serious challenge to international cooperation, political opportunity structures, such as permissive elections or referendums on international treaties, must exist to channel this discontent into concrete demands for more or less international cooperation. When transferred to the international level through these channels, growing politicization means that the mass public can become more important for international relations and international institutions in ways that can either enhance or constrain international cooperation. On the one hand, more public debate about the contours of international cooperation has the potential to bolster the legitimacy of international institutions. On the other hand, mobilization of nationalist sentiments by political entrepreneurs makes it more difficult for governments to enter new multilateral agreements, reduces their credibility when they do, and increases the likelihood that they will renege on these commitments ex post.

Empirically, we draw on evidence from around the world, with a particular focus on Europe. Although the bulk of existing work on the role of public opinion on foreign policymaking stems from the US context,Footnote 21 focusing on other countries allows us to broaden our focus and demonstrate the wide scope of our argument. Moreover, the European context allows us to examine variation in politicization across countries exposed to the most ambitious attempt at international cooperation to date. The EU is perhaps one of the clearest manifestations of the Liberal International Order,Footnote 22 as the most advanced IO in terms of the depth and scope of rule-based integration among its member states. It has facilitated free trade across its members and has a treaty basis that expresses a commitment to democracy and human rights. Looking beyond the US context teaches us that the effects of politicization are not unidirectional but instead can have both stabilizing and destabilizing consequences for international cooperation. This is an important perspective for students of international relations more generally. Although IOs face threats to their existence, they also have ways to move through crises and be resilient.

Public Contestation of International Cooperation

International cooperation is often opaque and difficult for ordinary citizens to grasp. It involves organizations or agreements with which most people lack direct experience. In much of the early work on international cooperation, the assumption was that the low salience and welfare-enhancing effects of international cooperation would lead to a “permissive consensus”Footnote 23 among citizens.Footnote 24 As a result, it has traditionally been assumed that policymakers would not be punished for engaging in international cooperation. Yet, as the level of international authority and the public awareness of it has grown, such a permissive consensus can no longer be taken for granted.Footnote 25 Although some public skepticism about the merits of international cooperation has been growing for quite some time,Footnote 26 the intensity with which it has manifested itself more recently is a rather new development. Against this backdrop, it is important to understand variation in public contestation of international cooperation across countries, across types of cooperation, and across time. To do so, we examine the nature and sources of public discontent with international cooperation as well as the activities of political entrepreneurs and political opportunity structures in order to explain how the interaction of these factors shape their impact on international cooperation.

The Nature and Sources of Public Discontent with International Cooperation

We start with examining the mass public's attitudes toward international cooperation, broadly defined as attitudes about the opening of borders to flows of goods, services, capital, persons, specific international institutions, and general international cooperation. If the public is broadly supportive of international cooperation, then it places few constraints on policymakers operating on the international level. The opaque nature of IOs or agreements shielded political elites against the opinions of the public for a long time. Trade liberalization and international cooperation were perceived to generate a sustained and diffused improvement in living standards for a large fraction of the population.Footnote 27 Over the past two decades, during which economic shocks raised the salience of increasing inequality and migration, international cooperation has become a more contentious subject in public debate.Footnote 28 Studies suggest that the public is often more critical of international institutions than elites are, and that among certain parts of the population, discontent is on the rise.Footnote 29

What are the roots of public discontent with international cooperation? Existing research has three broad sets of explanations: an economic, a cultural, and an institutional explanation. The first focuses on the economic consequences of international cooperation and the long-term structural changes in labor markets and the welfare state. It also considers and the rising inequality as well as the short-term economic shock that are associated with open economies and that create winners and losers. In this view, dissatisfaction with the existing system is caused by material hardship experienced by those “left behind” by globalization and technological change.Footnote 30 The second explanation highlights the importance of growing concerns about identity and cultural value divides.Footnote 31 It is based on the idea that the rise in electoral support for political parties that stress parochialism, nationalism, protectionism, and opposition to immigration constitutes a “cultural backlash” against liberal elites.Footnote 32 The dividing line is perceived to be between the highly educated who espouse more pro-immigration and cosmopolitan attitudes, and the less-well-educated who are wary of immigration and open borders.Footnote 33 The third explanation focuses on international institutions themselves and highlights the way in which they increasingly constrain domestic politics and policies as well as states’ ability to protect the losers from these processes. As a result, international authority has become increasingly contested,Footnote 34 not just in terms of its legitimacy,Footnote 35 but also in terms of strategies and practices that challenge established multilateral institutions.Footnote 36

Although the literature often treats these three explanations of public opinion as mutually exclusive, these factors should not be viewed as operating in isolation. After all, most social phenomena are multi-causal in nature and need to be addressed as such. The economic, cultural, and institutional explanations interact and together help us to understand complex phenomena such as support for international cooperation. Differences among economic groups and economic grievances are often articulated in cultural terms and are politically institutionalized. Processes of economic and political interdependence have coincided with increasing migration flows, creating difficult trade-offs,Footnote 37 and cultural, economic, and political motivations may co-exist. Indeed, the mass public itself tends to view international cooperation as “a package of openness”Footnote 38 that includes free trade and economic cooperation, but also non-economic aspects such as loss of national control, growing exposure to foreign influences including immigration, and an increasingly multicultural society with shifting social norms. It is therefore important to study how people navigate these multiple dimensions, how they make the relevant trade-offs, and how this is related to support for or opposition to international cooperation more generally. People may like the idea of international cooperation in the abstract but not display much appreciation for technocratic standard setting or the cost of annual contributions.

Consider support for the activities of IOs, for example. Using data from the 1995, 2003, and 2013 waves of the International Social Survey Program (ISSP) and twenty-one countriesFootnote 39 across five continents, Figure 1 shows the percentages of respondents who view international institutions positively (black line) or negatively (gray line). It shows a decline over time in the people who support the right of IOs “to enforce solutions to certain problems” and an increase in people who think that “IOs take too much power for national governments.” Moreover, Figure 1 demonstrates that support for IO activities not only varies over time but also differs significantly depending on which dimensions of these activities we examine. For example, more than two-thirds (68%) of respondents in countries across the world agree that “for certain problems, like environment pollution, international bodies should have the right to enforce solutions.” At the same time, however, only 37 percent of respondents think that their country in general should follow the decisions of IOs, even if their government does not agree with the decision, and almost every second respondent (48%) agrees that IOs are taking away too much power from their national government. In fact, among those agreeing that IOs should be able to enforce solutions, approximately one quarter thinks that their government should not comply with these solutions if it disagrees.

FIGURE 1. Support for international organizations, 1995–2013

Source: International Social Survey Program, waves 1995, 2003, 2013. Share of respondents (dis)agreeing or strongly (dis)agreeing with each statement.

Figure 1 illustrates that public opinion about international cooperation is ambivalent in nature.Footnote 40 Attitude ambivalence is important because it makes citizens much more open to taking cues from political elites.Footnote 41 This makes public opinion more malleable. In the absence of an international public sphere, citizens often rely on political elites or the mass media in forming opinions about international cooperation.Footnote 42

Taken together with the complex and multidimensional nature of international cooperation, we argue that this makes the actions of political entrepreneurs, and the media response that they might invoke, crucially important in trying to understand how trade-offs related to international cooperation are framed and how the mass public thinks about them as a result. By framing international cooperation as a package deal, political entrepreneurs can activate those pre-existing public sentiments that are most advantageous for them to politicize. This helps explain why citizens in countries facing similar levels of international authority often show different levels of discontent with and support for international institutions, and why countries also differ in the extent to which opposition to international institutions becomes politically relevant.

The Role of Political Entrepreneurs

Public discontent with international cooperation alone is therefore not sufficient to lead to a serious challenge to international institutions. For such discontent to matter politically, it must be politicized. Politicization refers to the process of making an issue political, that is, debating it in the public sphere as an issue of public contestation.Footnote 43 It can occur when governments blame international institutions for bad domestic policy outcomes. President Trump's stated intention to withdraw from the World Health Organization in an effort to distract from the US government's suboptimal response to the COVID-19 crisis might be viewed in this light. Although withdrawal from IOs is among the more radical responses, governments routinely blame IOs for negative domestic outcomes. Examples include the “scapegoating” of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for the conditionality incorporated in their programs,Footnote 44 or the EU in the context of the Eurozone crisis.Footnote 45

Another way in which discontent is mobilized is by political entrepreneurs.Footnote 46 Most mainstream politicians support, at least publicly, IOs and a liberal international order built on multilateralism. This consensus is being increasingly challenged by political entrepreneurs who mobilize voters with a nationalist “drawbridge up” message, favoring stronger borders, less migration, protectionist policies, and withdrawal from international cooperation.Footnote 47 This mobilization is not only the result of grievances associated with international cooperation, as discussed in the previous section, but is also a result of the effort of strategic politicians.Footnote 48 Public dissatisfaction and the efforts of strategic politicians reinforce each other. Political entrepreneurs try to successfully ignite opinions that lie dormant, or mobilize aspects of pre-existing discontent that are the most advantageous to politicize. In doing so, political entrepreneurs seek to gain electoral advantage from driving a wedge between mainstream elites and their supporters by mobilizing opposition to international cooperation.Footnote 49 Such mobilization can be significantly amplified by the media.Footnote 50 In response, more cosmopolitan political forces have equally increasingly mobilized on the issue of international cooperation, turning against this nationalist message.Footnote 51 Green and social liberal parties have increasingly committed themselves to cosmopolitan and internationalist stances,Footnote 52 and so have government leaders such as the Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, French President Emmanuel Macron, or New Zealand's Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, to name a few recent examples.

Theories of issue evolution and issue manipulationFootnote 53 teach us that strategic politicians are crucial in the politicization of previously nonsalient issues, as parties facing a string of losses will attempt to redirect political competition to structure political competition in such a way that they gain leverage. Attacking international cooperation is one way for politicians to seek to gain such leverage, especially where public discontent already exists. However, in multiparty systems in which the mainstream political coalitions are built around commitments to international institutions such as the WTO, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), or the EU, it is costly for mainstream parties to challenge this established order. Taking a stance on a controversial wedge issue is inherently risky because the mobilization of such issues may destabilize parties internally, put off certain voters, and jeopardize future coalition negations.Footnote 54 Issue entrepreneurship also carries the potential of reshaping political competition and thus reaping electoral success. A core feature of the politicization of opposition to international cooperation thus comes from challenger parties that occupy losing positions on the dominant dimension of political competition—parties that act as issue entrepreneurs and thus play a key role in the politicization of issues.Footnote 55

One prominent example of how political entrepreneurs have mobilized international cooperation is the growing emphasis on opposition to the EU among challenger parties across European countries. The EU issue constitutes a classic wedge issue in European politics because it is an issue that is not easily integrated into the dominant dimension of left–right politics. The process of European integration has provoked deep tensions within major parties on both the left and right.Footnote 56 As EU membership is a core component of the postwar mainstream political consensus in Europe and its commitment to the Liberal International Order, an openly anti-EU position will also make parties less credible as coalition partners. As a result, most mainstream parties have preferred not to politicize an issue that could lead to internal splits and voter defection. In contrast, for challenger parties, there are great incentives to mobilize opposition to the EU to attract new voters, often in tandem with anti-immigration and nationalist messages.Footnote 57

We can use data from the Chapel Hill Expert Surveys (CHES) on the positions of political parties across EuropeFootnote 58 to illustrate this point. Experts were asked to rank each party's “general position on European integration” from (1) strongly opposed to (7) strongly in favor. Figure 2 shows that mainstream parties are united in their commitment to the pro-EU cause, with an average score near 6, whereas challenger parties are much more heterogeneous and generally more Euroskeptic. Looking at this by party family, we can see that the radical right and the radical left mobilize the anti-EU cause, whereas all the other party families are broadly pro-European, regardless of whether they are left or right. Because mainstream political elites remain on average considerably more supportive of European integration than citizens, Euroskeptic political entrepreneurs can reap electoral gains.

FIGURE 2. Party positions on European integration

Source: International Social Survey Program, waves 1995, 2003, 2013. Share of respondents (dis)agreeing or strongly (dis)agreeing with each statement.

Source: Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trendfile

There is also considerable ideological heterogeneity in the content of Euroskeptic party cues. Research has shown that whereas left-wing Euroskeptic parties mobilize economic anxieties and anti-austerity concerns against the European project, right-wing Euroskeptic parties rally opposition by highlighting national identity considerations and feelings of cultural threat.Footnote 59 This points to the ability of political entrepreneurs to frame international cooperation in such a way that suits them best. The fact that the mass public tends to view international cooperation as a “package of openness” that includes not only economic aspects relating to free trade, but also non-economic ones such as sovereignty concerns, concern about foreign influences, or about a multicultural society,Footnote 60 provides political entrepreneurs with some flexibility in choosing how to frame the threats of international cooperation and to focus those elements that are more salient for voters.

Overall, the actions of political entrepreneurs are crucial in determining the nature and level of public contestation of international cooperation. Strategic politicians can harness drivers of discontent for their own political gain. Public discontent is therefore a necessary but not sufficient condition for politicization. Public contestation is likely to be greater when the drivers of discontent with existing forms and levels of international cooperation are activated by political entrepreneurs. In contrast, it will be less if either the public is satisfied with the status quo of international cooperation or there is a lack of political entrepreneurs to mobilize any discontent. Determining what is causally prior—public discontent or political mobilization—is inevitably tricky as these feed off and reinforce each other. What is important is that public contestation requires both.

Political Opportunity Structures

Taken together, public discontent with and mobilization of international cooperation by political entrepreneurs generate public contestation. But public contestation leads to a serious challenge to international cooperation only when the right political opportunity structures are present. Such opportunity structures include institutional arrangements that allow public discontent to translate into an effective challenge to international cooperation.

One obvious pathway to a direct challenge of international institutions, as we have seen, for example, in the United States and Hungary, is the election of a government that is skeptical about international cooperation and that has both the will and the institutional power to challenge it. However, such cases, which are the direct result of increased public discontent and elite mobilization, remain relatively rare because most Western governments are generally favorably disposed toward international cooperation.Footnote 61 Elections are usually fought over a myriad of domestic policy issues. That said, certain institutional characteristics, such as electoral rules and multiparty systems, make it easier for political entrepreneurs to generate public contestation over international cooperation. Proportional electoral rules foster multiparty competition, which makes it easier for new parties not only to break through, but also to campaign on a more specialized issue offering.Footnote 62 Within systems with majoritarian electoral rules, political entrepreneurs face higher barriers to entry. Such contexts make it harder for new parties and issues to permeate the system, although this is possible, as the example of the 2017 French presidential elections demonstrates, in which neither of the two second-round candidates (Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron) belonged to any of the established French mainstream parties. An alternative strategy for political entrepreneurs in majoritarian contexts is to try to gain a stronghold within established political parties, as US President Donald Trump did within the Republican Party, or British Prime Minister Boris Johnson did within the Conservative Party. Although it may prove harder for political entrepreneurs to mobilize issues relating to international cooperation within a majoritarian context, the systemic effect on international cooperation is likely to be much more profound. In contrast, in contexts with proportional electoral rules and multiparty competition, public discontent with international cooperation mobilized by political entrepreneurs may get defused through coalition negotiations and coalition governments, as the examples of the Freedom Party in Austria or the Five Star Movement in Italy demonstrate.

The introduction of direct elections to the EU's legislative chamber, the European Parliament (EP), four decades ago is another example of how elections can provide a platform for political entrepreneurs skeptical about international cooperation. These second-order EP elections with permissive electoral rules and little at stake for voters act as an incubator for electoral success at the national level also, by increasing their resources and heightening their brand and visibility.Footnote 63 In the 2019 elections to the EP, for example, parties highly critical of the EU topped the polls in Britain, France, and Italy, with serious domestic reverberations and possible consequences for the nature of the relationship between these member states and the EU.

Another way that challenges stemming from political opportunity structures allow public discontent to challenge international institutions, aided by political entrepreneurs, is a referendum on international cooperation. Direct democracy allows citizens a direct say regarding international institutions. Popular referendums on international treaties have long been seen as a means of increasing the democratic legitimacy of international cooperation.Footnote 64 Over the past decades, referendums have not only become a much more common feature in the ratification process of international agreements, but have also more often led to outcomes that are not in line with the government's preferred outcome.Footnote 65 This poses an important challenge to the conventional wisdom that government can use such domestic constraints to increase their bargaining power at the international level.Footnote 66

Figure 3 shows that between 1970 and 2019, eighty-four referendums about international cooperation were held across the world in countries as diverse as Brazil, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom.Footnote 67 Although the majority of these referendums were about issues relating to European integration broadly defined, approximately one third of these referendums concerned international cooperation in the context of other international institutions, such as NATO, trade agreements, the United Nations, or international courts. Figure 3 shows that in line with our argument about the growing politicization of international cooperation, the use of referendums has increased in recent decades, and noncooperative referendum votes, that is, referendum outcomes in which voters vote against the establishment of a new or the continued membership in an existing international institution, have increased.Footnote 68 Since 2010, voters have voted down proposals for more or continued international cooperation in every other referendum. By providing opportunities for political entrepreneurs, many of these referendums have also had longer-term consequences by fostering a sustained politicization of issues related to international cooperation.

FIGURE 3. Voting outcomes of referendums on international cooperation, 1970–2019

Source: Centre for Researchon Direct Democracy (C2D) Database, authors' own calculations. See online appendix for details.

Taken together, the mass public can turn into a relevant force for international relations when political entrepreneurs use political opportunity structures to their advantage to mobilize public discontent.

Implications for Countries’ Ability to Engage in International Cooperation

Discontent with international authority, mobilized by political entrepreneurs and transmitted onto the international arena through political opportunity structures, changes the role that the mass public plays in international politics. But the way in which this affects the prospects for international cooperation is not straightforward.Footnote 69 On the one hand, these developments make it more difficult for policymakers to create new or to sustain existing cooperative institutions. On the other hand, the growing involvement of the mass public provides possibilities for international institutions to increase their legitimacy.Footnote 70 Politicization thus poses both a challenge to international cooperation and an opportunity for international institutions to show resilience.Footnote 71

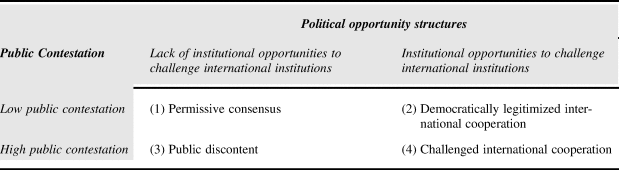

How and whether the mass public matters for international cooperation, and whether this influence strengthens or weakens international institutions, depends on both the nature of public contestation and the availability of political opportunity structures. Table 1 shows four different scenarios for how the mass public matters for a country's ability to engage in and sustain international cooperation. On the vertical axis, it distinguishes between instances of high contestation—in which public opinion about international cooperation is mobilized by political entrepreneurs—and instances of low contestation—in which the public either is not discontented or there are no public entrepreneurs to mobilize existing discontent, or both. On the horizontal axis, it distinguishes between political opportunity structures that allow domestic contestation to be directly transmitted to the international level, and those structures in which such transmission is much more restricted. This yields four ideal-typical scenarios for how the mass public matters for international institutions.

TABLE 1. Consequences of politicization for countries’ ability to engage in international cooperation

The first scenario of permissive consensus is one in which there is both a lack of public contestation and an absence of institutional opportunities for challenging the international order. In this scenario, international institutions are typically an elite-driven project of low salience and with broad public acceptance. This has always been and continues to be by far the most common scenario for most international institutions. Whereas some international institutions, such as the IMF, the EU, and the ICC, have become contested, the vast majority of international institutions do not attract much public attention. Other IOs, such as the International Civil Aviation Organization, the World Meteorological Organization, or the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, rarely feature prominently in the public debate, and public opinion matters little to how these institutions are created, function, or decay.

In the second scenario, democratically legitimized international cooperation, the political institutional structure provides the public with opportunities to challenge international institutions. The public uses these opportunities to support these international institutions, either because discontent is slight and/or not mobilized. In this scenario, institutional opportunities such as referendums give international institutions a high level of democratic legitimacy, that is, the public believes that the institution's exercise of authority is appropriate.Footnote 72 An example of this is the support for the United Nations in Switzerland, a country with a strong direct democratic tradition. Because of Swiss neutrality, UN membership was long a hotly contested issue in Swiss politics, despite the fact that numerous UN organizations are based in the country. In 1986, an overwhelming majority of 76 percent of Swiss voters rejected a government proposal to join the United Nations. The issue remained contested, and in the late 1990s, a cross-party committee launched a popular initiative to put the proposal for UN membership to a second popular vote. In 2002, this proposal was accepted by a 54.6 percent majority of Swiss. As a result, Switzerland joined the United Nations and the issue quickly lost salience. The ability to directly vote on UN membership thus in effect legitimized Switzerland's UN membership. Today, Swiss UN membership is widely accepted in Switzerland.

The public response, however, is not always so positive. In other cases, when public opposition to international cooperation remains entrenched and mobilized by political entrepreneurs, this may lead to lasting public discontent with the status quo. Yet, when political opportunity structures do not allow this contestation to be channeled into an effective institutional challenge, it remains simply that: a simmering discontent without any immediate systemic repercussions. In Austria, for example, Euroskepticism is both very strong and mobilized by political entrepreneurs, such as the Freedom Party. Yet, compared with the situation in the United Kingdom, the domestic contestation has had little systemic effect. This is because the Euroskeptic demands of the Freedom Party have been curtailed by more pro-EU coalition partners, and no referendums on European integration have been held after the accession referendum in 1995.

Only when political opportunity structures are permissive is public contestation likely to spill over to the international level, creating a systemic challenge. This is the most consequential scenario from the perspective of an international institution. In this scenario of challenged international cooperation, shown in the lower right-hand quadrant of Table 1, public contestation is channeled into a concrete challenge to the status quo of international cooperation, expressed in forms such as public vetoes of new international commitments, demands for differentiated integration, withdrawal from existing arrangements, or demands for alternative forms of international cooperation. An example of how a political entrepreneur, buoyed by institutional opportunities, introduced a challenge to European integration is the case of the Dutch politician Geert Wilders and his Party for Freedom. The issue of European integration had not been not salient in Dutch public debate until the 2000s, when Geert Wilders entered the political scene as a political entrepreneur.Footnote 73 The 2005 referendum about the European Constitutional Treaty, the first-ever referendum held in the Netherlands on EU matters, provided an opportunity for Wilders. With 61.5 percent of Dutch voters voting against the treaty, the referendum had significant consequences for the EU: following the Dutch (and French) rejection, the EU abandoned its ambitious attempt at a constitutional treaty in favor of a more modest “amending treaty”: the Lisbon Treaty.

Likewise, elections in which issues of international cooperation feature as key campaign issues can result in this scenario. Examples include Presidents Donald J. Trump in the United States, or Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, who have campaigned on a nationalist populism platform that has presented a direct challenge to international institutions such as the Paris Agreement or the World Health Organization. In the first three years of his presidency alone, Trump had withdrawn US membership from seven major international institutions.Footnote 74 At the same time, the example of French President Emmanuel Macron's attempts to achieve a serious reform of the EU highlights that challenges to the status quo by some politicians may also be directed toward achieving closer international cooperation.

Systemic Implications of Public Contestation

What are the systemic consequences of the growing involvement of domestic mass publics for international institutions and international cooperation more generally? The four scenarios discussed suggest that the impact of the national mass public on the prospects of international cooperation is likely to vary significantly. The scenario with the most serious systemic consequences is scenario 4, a direct challenge to international cooperation. Especially when the challenge comes in the form of opposition to international cooperation, countries in this scenario have the potential to complicate each stage of international cooperation: the negotiation of new cooperative agreements, the ratification process, and the functioning of international institutions. When a cooperation-skeptic domestic public, especially one that is mobilized by political entrepreneurs, has the opportunity to veto new arrangements, the salience of new cooperative agreements reduces the ability and willingness of policymakers to make the package deals and side payments that have long characterized international negotiations. As the literature on two-level games has demonstrated,Footnote 75 this makes it more difficult for policymakers to negotiate new international agreements and enter arrangements with other countries that require compromise, even though it can also raise countries’ bargaining power. Ratification of international agreements also becomes more difficult in this scenario. When the public pays more attention to the details of the negotiations and when some elites mobilize voters against the negotiated agreement, it becomes harder for governments to control the domestic ratification dynamics. This is particularly true when referendums are used as a part of the ratification process. In this scenario, the outcome of the ratification process is thus often uncertain, and the likelihood of a negotiated agreement's failing increases. These domestic ratification constraints raise the risk of involuntary defection and thus may hamper governments’ ability to successfully ratify negotiated agreements.Footnote 76 Finally, this scenario also presents an increased risk that countries will renege on their international commitments ex post, such as through treaty renegotiations, noncompliance, or even the partial or full exit from existing international agreements.Footnote 77 This creates uncertainty about the public acceptance of outcomes, even after a treaty is ratified.

How these dynamics play out depends both on how much leverage the state in question has at the international level and on how the international institution itself responds to the challenge. The more leverage a state has, the more consequential the challenge is for the affected international institution. For example, in situations in which unanimity is required to attain a new level of cooperation, each member state's leverage is high. In these situations, one state's failure to reach an agreement can lead the entire project to unravel (as it did after the 2005 rejections of the European Constitutional Treaty in the Netherlands and in France). In these cases, cooperation-skeptic member states are also often able to negotiate substantial concessions, such as opt-outs from certain provisions (an example is the opt-outs that Denmark negotiated after it had failed to ratify the Maastricht Treaty).Footnote 78

In many situations, however, the leverage of individual member states is much lower. When decisions are made by qualified majority voting, for example, as in many policy areas in the EU, dissenting votes allow the cooperation-challenging member state to cast a noncooperative vote, but it cannot prevent the other member states from moving forward if a majority of the member states supports a policy proposal. Such flexibility allows governments to signal their responsiveness to the skeptical domestic public, yet cooperation continues.Footnote 79 In other situations, the leverage of the cooperation-challenging member state is so slight that the other member states can force it to backtrack. For example, after the Greek people had overwhelmingly rejected new austerity measures associated with a European bailout package in a referendum during the Eurozone crisis in 2015, the other Eurozone countries confronted the Greek government with the choice to either accept more austerity or leave the common currency. Because the Greek public, although opposed to austerity, had a strong preference for staying in the Eurozone,Footnote 80 the Greek government chose to disregard the referendum vote and to accept a third bailout package instead. One of the reasons that challenges to the status quo are less likely to have systemic reverberations if they are directed toward closer or different forms of cooperation is that the leverage of one state to compel institutional changes is much less in most international settings than a state's leverage in vetoing such changes.

The international response to the demands of a cooperation-challenging member state is not just a question of leverage, however. Rather, the international institution itself, or perhaps more precisely, the other member states within the international institution, also have to weigh the costs and benefits of accommodating these demands versus the costs and benefits of not accommodating them. This decision weighs particularly heavily when the challenging state is a member state of an international institution and opposes the deepening or the continuation of the institution's existing cooperative arrangements. To the extent that the other member states are interested in more or continued cooperation, this creates an “accommodation dilemma.”Footnote 81 On the one hand, other member states have incentives to accommodate the demands of the cooperation-challenging country as far as possible in order to retain the benefits of cooperation, even if this means that the cooperation-challenging country receives a larger share of the overall cooperation gains. On the other hand, such accommodation carries the risk of encouraging other countries to follow suit and also try to improve their position through a less cooperative stance, which may result in an eventual unraveling of the compromises that form the core of international agreements. As a consequence, the greater the potential contagion risks of accommodating the demands of a cooperation-challenging state are, the stronger the incentives for the other member states to take a hard, non-accommodating line in the ensuing negotiations in order to deter other states from following suit, and vice versa. This strategy is not without risks either, however, because it enables political entrepreneurs to use this uncompromising stance as an argument to delegitimize the international institution further.

An example of how domestic contestation of an international institution, in combination with political opportunity structures, can have systemic implications is the case of Brexit, Britain's vote to leave the EU in 2016. Public discontent with the EU has a long tradition in the United Kingdom. However, with no parties in Parliament advocating Britain's exit from the EU, the issue was not highly contested.Footnote 82 Yet, the question of membership became more mobilized when the elections to the EP provided a platform for the anti-EU challenger party, the UK Independence Party. The party's win in the 2014 EP elections contributed to the decision by the Conservative government to call a referendum on EU membership.Footnote 83 The 2016 Brexit referendum then provided the opportunity structure for an issue that cut across the traditional party lines to become the defining issue in British politics since that point and to reshape public opinion in profound ways.Footnote 84 Brexit also has significant systemic implications because it meant that one of the largest and most powerful member states would leave the EU. This confronted the remaining twenty-seven EU member states with a significant accommodation dilemma: loss of the close cooperative relations between the United Kingdom and the EU would be costly not just for the United Kingdom, but also for the EU-27. At the same time, making the United Kingdom better off outside the EU would raise the risk that further countries would leave the EU.Footnote 85 The Brexit case thus illustrates not only the domestic scope conditions for a direct challenge to an international institution, but also how the international response to such a challenge may shape the future of the organization and may feed back into domestic mass politics.

Conclusion

International institutions are increasingly challenged by domestic opposition and nationalist political forces. In times of a growing politicization of international politics, the mass public has taken on a more active role in international politics and does not always behave in ways predicted by governments. This study demonstrates that such developments can have both stabilizing and destabilizing effects on international cooperation, which suggests that the domestic political arena is a key battleground for protecting forms of international cooperation. The recent success of political entrepreneurs taking a firm aim at IOs, such as US President Donald J. Trump or Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, can be matched by those defending the international order, such as French President Emmanuel Macron or New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern. The battle is about winning the hearts and minds of the public.

Our study of the role of the mass public in international cooperation has set out a research agenda focused on the causes and consequences of the growing public contestation about international cooperation. For this purpose, we have developed a framework that emphasizes the agency of political actors at the domestic and international levels and political opportunity structures as crucial drivers of effective public contestation of international cooperation. This framework identifies the nature of public discontent, the activities of political entrepreneurs, and the permissiveness of political opportunity structures as important scope conditions for the politicization of international cooperation. We argue that public discontent alone does not pose a serious challenge to international institutions. For such discontent to matter politically, it must be politicized. How this politicization affects countries’ ability to engage in international cooperation, and the stability of international institutions, in turn depends on the nature of contestation, the international leverage of the skeptical country, and how the international institution itself responds to this challenge.

Our study also raises questions about the endogenous relationships underlying politicization. A first set of questions relates to the relationships among the mass public, political entrepreneurs, and political opportunity structures at the domestic level. We have argued that certain institutional characteristics, such as electoral rules, multiparty systems, and the presence of referendums, make it easier for political entrepreneurs to strategically activate public contestation over international cooperation. Within systems with majoritarian electoral rules, political entrepreneurs face higher barriers to entry.Footnote 86 In these contexts, entrepreneurs have a strategic incentive to reshape political parties from within. If they succeed, the consequences for international cooperation are likely to be greater compared with more permissive contexts, as political entrepreneurs face less political and institutional pressure to compromise. The extent to which institutional rules shape the way in which political entrepreneurs frame and politicize international cooperation is an important area for future research.

A second set of questions relates to the feedback effects between domestic and international politics, and across member states in international institutions. One set of feedback effects can occur horizontally. As the mass publics in other countries observe how one country's voter-based challenge to international cooperation plays out internationally, such challenges have the potential to reverberate both across countries and across time.Footnote 87 Another set of feedback effects can occur vertically between the international level and the domestic level. For example, because international institutions in a low public contestation environment face fewer constraints on their actions than those who face high public contestation domestically, they can often perform their tasks more freely and effectively.Footnote 88 This can create positive feedback effects, as a demonstrated problem-solving capacity increases the mass public's perception of the institution's legitimacy.Footnote 89 But such a response can also result in a growing intrusiveness of the IO's decisions that then fosters public contestation,Footnote 90 thus moving the IO from a low- to a high-public contestation scenario. Likewise, governments may respond to high levels of domestic contestation by depoliticizing decisions through turning them into technocratic issues or delegating them to technocratic authorities.Footnote 91 One danger with such a strategy is that it reduces the IO's accountability; another is that it may eventually turn the organization into a “zombie international organization” with limited activities.Footnote 92

If international institutions respond by being more responsive to public concerns, this may result in making international agreements more flexible, for example, by including escape clauses,Footnote 93 by decreasing the authority of IOs,Footnote 94 or by creating more democratic institutions that give political entrepreneurs new avenues for becoming involved. Such responsiveness can create positive feedback effects and may ultimately strengthen support for international cooperation, thus moving the IO from a high- into a low-public contestation scenario. But such a strategy also carries the risk of moving from a public discontent to a challenged international cooperation scenario, especially when measures put the benefits associated with the centralization of collective activities and independence of IOs at risk. After all, the agency of political entrepreneurs suggests that there is no simple linear relationship between the level of international authority and the severity of the challenge posed to it by the mass public. Future research should explore these proposed feedback effects in greater detail. This study has provided a framework for understanding when and why the mass public poses a challenge to international cooperation, and has highlighted the need to recognize endogeneity as an integral feature of the relationship between domestic politics and international cooperation.

In closing, we invite more theoretical and empirical work examining the causes and consequences of the politicization of international cooperation. We think that fusing insights from international relations and comparative politics as well as across different areas of regional expertise, North America, Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Asia, is the most fruitful way of doing this. Regarding the causes of public contestation of international cooperation, we wish to see future work moving beyond the current debate about the role of economic grievances, cultural fears, or worries about loss of national control. We suggest that understanding how people navigate these different concerns, how they make the relevant trade-offs, and how this is in turn related to support for or opposition to international cooperation more generally, generates important insights. Regarding the consequences of public contestation for international cooperation, international relations work should move away from making simplifying assumptions about the public's underlying preferences. Audience cost theoryFootnote 95 and research on two-level games in international negotiationsFootnote 96 assume that governments have a good understanding of how both their own and their opponent's domestic audiences would react to different foreign policy decisions. Yet our study suggests that the reality is frequently far more complicated. Often it is not easy for governments to predict public responses to foreign policy decisions. Governments may also find themselves caught off guard by political entrepreneurs who have every incentive to exploit even the tiniest of rifts between incumbents and their supporters. Likewise, studies examining how the preferences of median voters influence foreign policymaking by national governments and legislators,Footnote 97 and research on how governments take domestic preferences into account during international negotiations,Footnote 98 such as when negotiating about the content and design of international institutions,Footnote 99 assume that policymakers know their voters’ preferences and can use them as a strategic tool in international negotiations. We argue that governments often face high levels of uncertainty about ascertaining their voters’ preferences and understanding the extent to which these voters will be mobilized domestically, and that this uncertainty may affect the behavior of governments in international negotiations. The way in which this uncertainty affects behavior is an important area of future research.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this article may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GAAKFB>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000491>.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeff Checkel, Sara Wallace Goodman, Abe Newman, Maggie Peters, Michael Zürn, the anniversary issue editors, and workshop participants for helpful comments. Reto Mitteregger provided excellent research assistance.

Funding

This article was funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme grant agreement No 817582.