Why has gold persisted as a monetary reference for over a century since the classical gold standard collapsed during World War I? Why do states still hold on to gold when “they have no more reason to hold gold than, say, antiques”?Footnote 1 Standard accounts of international monetary relations do not give a cogent answer to this question. They commonly depict a succession of discontinuous institutional “systems” or “regimes” that waxed and waned with changes in power structures and economic ideas. For example, the demise of the gold standard in the 1930s and 1940s is often associated with the ascent of the United States as a world power and of Keynesian views of the economy. Yet the persistence of gold across successive international monetary regimes is underappreciated. Gold continued to have an outsized policy impact after the Keynesian turn, after the shift to a de facto dollar standard, and even after the closing of the gold window in 1971. This importance is at odds with standard views of gold as the vestige of a bygone era.

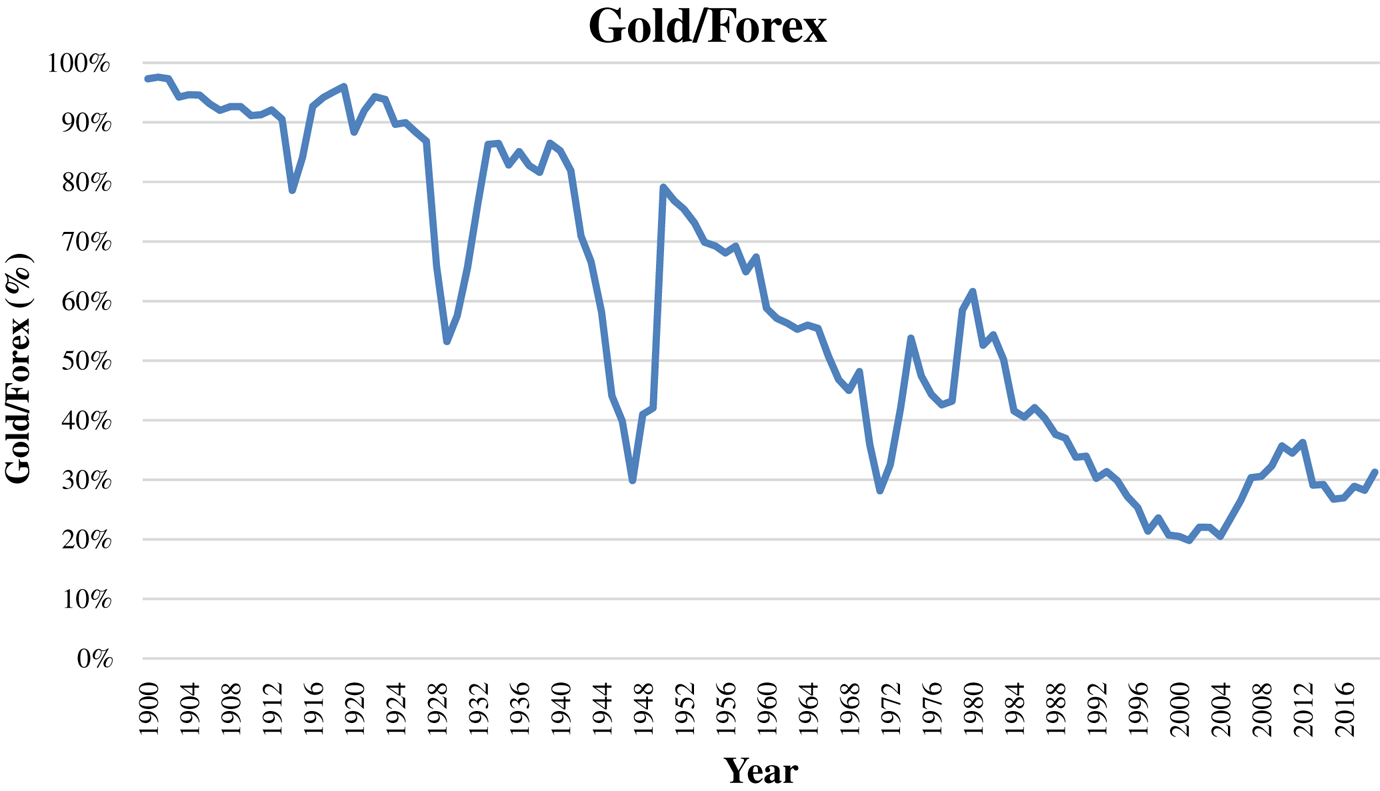

The uniqueness of gold is attested by its ghostly afterlife. Gold no longer has an official monetary role today, but states and international organizations still hold thousands of tons of gold reserves. The aggregate share of gold in the total reserves accumulated by the central banks of the G7 countries (including the European Central Bank and the IMF) has undergone only a slow decline since its apex above 90 percent in the early twentieth century (Figure 1).Footnote 2 Even today it remains around 30 percent—that is, slightly higher than its share when the US gold window was closed in 1971. The past specie backing of currencies thus continues to cast its shadow on international monetary relations today, and not even the dollar is deemed as stable as gold appeared to be from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century. Some analysts have warned of an impending decline of the dollar, accelerated by the 2008 financial crisis,Footnote 3 while others have recommended that developing countries increase their gold reserves.Footnote 4 So it does not appear that the status of gold as a reserve asset is in any immediate danger—quite to the contrary. Gold accumulation can be justified, of course, as a way for central banks to diversify their portfolio of reserve assets. But this hedging logic alone would call for further diversification to other assets, and hardly justifies 30 percent of all reserves being held in the form of gold.

Figure 1. Aggregate share of gold over total foreign exchange reserves (including gold) held by the central banks of G7 countries—plus the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the European Central Bank—from 1900 to 2019.

In this article we offer an account of gold's persistence as a core element of international monetary relations from 1944 to the mid-1970s, when the world moved to floating exchange rates. In the international political economy (IPE) literature about that period, gold is secondary—as if relegated to a ceremonial role by the hegemony of the US dollar and “embedded liberalism,” and then by the onset of neoliberalism. To explain the continuing impact of gold, we build on social psychology and new materialist theories to conceive of money in the world's political economy as an assemblage. An assemblage is a persistent and active linkage between heterogeneous elements. The concept highlights the continuously evolving order achieved through transactions between individual actors and the social and material environments in which they operate. It therefore involves dynamics of order and interactions with the material environment that more conventional concepts tend to neglect, since they designate relatively static and coherent social structures or ideas. In this instance, what we call money in IPE is not a straightforward and clearly bounded institutional reality, like the “regimes” or “systems” usually depicted by IPE scholars. It is a complex and perpetually evolving arrangement of material artifacts (namely, metallic specie and monetary instruments issued by central banks), institutions (including forms of international monetary organization, as well as core states’ monetary institutions), ideas (including economists’ monetary theories), and practices (the myriad monetary transactions between public and private actors). In turn, this assemblage was long held together by the enduring practice of referring money to gold—a pivotal practice that served as a linchpin of the international monetary assemblage. Well beyond the collapse of the classical gold standard, J.P. Morgan's famous 1912 pronouncement that “money is gold, and nothing else” continued to reflect monetary practice, as gold long remained the ultimate reference for money at the international level.Footnote 5 Actors could not easily imagine any substitute for it because, as we will show, their relationship to gold was not merely instrumental.

After laying out the conventional understanding of monetary relations as a succession of institutional regimes, we introduce an alternative conceptual framework that challenges this institutional reading of monetary relations to elucidate the persistent influence of gold. We then contrast our reading of the evidence with the traditional realist and constructivist interpretations, which identify changes in relative power or in dominant ideas, respectively, as drivers of regime change. Based on newly available archival evidence and secondary sources, we demonstrate the tenacity of specie backing in the construction of the postwar monetary order, its importance through years of incremental reforms in the Bretton Woods era, and the attempt to reinstitutionalize an international monetary system around gold despite strains that progressively undermined its centrality as a monetary reference. At each step, we show how the reference to gold shaped important developments that the conventional focus on successive monetary regimes underplays. Rather than discontinuities, this perspective thus highlights long-standing links between money and gold that were progressively transformed and only formally severed in the 1970s.

Practical Continuities in Political Economy

Scholars of twentieth-century international monetary relations conventionally distinguish three periods: an age of classical liberalism, dominated by the UK before the 1930s; a Keynesian shift toward “embedded liberalism” under US hegemony after 1944; and a shift toward neoliberalism under US auspices since the 1970s. Writing in the 1940s, Karl Polanyi saw the Great Depression as the final “collapse” of “nineteenth-century civilization,” of which the gold standard was a core institution.Footnote 6 Building on Polanyi's idea that the economy must be “embedded” in society, John Ruggie characterized the postwar economic order as a new era of “embedded liberalism” that underscored the “power” and “purpose” of the United States.Footnote 7 Finally, in the last decades of the twentieth century, scholars depict a broad shift to another regime characterized by the Washington Consensus.Footnote 8 This three-pronged periodization meshes with a long-standing model of regime change that highlights political realignments during short “critical junctures.”Footnote 9

Typically, the movement from one regime to the next is attributed to shifts in power or ideas. Thus, the realist view of Bretton Woods stresses US hegemony after World War II. The power of the United States to remake the monetary order gave the dollar a privileged position, and the Bretton Woods agreements served as a tool for the United States’ leadership. Realist scholars then highlight the importance of power politics for the Nixon administration and its decision to exploit the United States’ “structural power” via market-based governance in closing the gold window.Footnote 10 For example, Joanne Gowa argues that the Nixon administration sought to escape institutional constraints and follow a more “nationalist” policy.Footnote 11 Such realist readings of Nixon's decisions informed international relations scholarship at the time and through the 1980s. As Robert Gilpin summarized, “the American hegemon smashed the Bretton Woods system in order to increase its own freedom of economic and political action.”Footnote 12 In contrast, scholars with a more constructivist reading of the origins of the postwar order usually read the Bretton Woods agreements as the embodiment of a principled “compromise” between John Maynard Keynes, representing Britain, and the more orthodox Harry Dexter White, the head of the US delegation.Footnote 13 Scholars working in this vein also attribute the end of the Bretton Woods regime to the widespread adoption of neoliberal ideas,Footnote 14 with the shift to floating exchange rates as part of the move away from Keynesianism in the 1970s.Footnote 15

Recent scholarship has begun to problematize these causal mechanisms and the attendant periodization by underscoring the importance of incremental change and unintended consequences. Eric Helleiner points out that the Bretton Woods emphasis on development stems not exclusively from the influence of Keynesian ideas, but also from the experience of US policy toward Latin America in the 1930s.Footnote 16 James Morrison suggests that the devaluation of sterling in 1931—often portrayed as a conscious first step toward the postwar Keynesian era—was actually an “unintended experiment” that only later enabled Keynes to better promote his ideas.Footnote 17 As for the turn away from Keynesianism, Jacqueline Best argues that the “hollowing out of Keynesian-inspired norms” started well before the triumph of neoliberalism in the 1980s.Footnote 18 Challenging realist and constructivist readings of the demise of Bretton Woods, Gretta Krippner argues that financial liberalization was a largely unintended effect of contingent decisions.Footnote 19 Finally, on a general theoretical level, many scholars have also downplayed “critical junctures” in favor of more incremental and endogenous models of institutional change.Footnote 20

Consistent with this newer scholarship, our own intervention underscores the complexity and ambiguity of the international monetary environment practitioners faced. In particular, we emphasize the material role of gold and the habitual orientations and practices associated with it. Although most scholars gloss over the importance of gold, the influence of the United States in postwar monetary politics is inextricably linked to the fact that the dollar alone remained convertible into gold. Along with US hegemony, the concentration of the world's gold reserves in the United States after the Second World War helps explain the enhanced status of the dollar in international monetary relations. After all, gold had represented a fungible, high-density store of value for centuries, and international monetary relations had been constructed around it well before the rise of US power. It also stands to reason that the many practices and habits associated with the role of gold in international monetary relations would inflect Keynesian ideas and the reconstitution of the postwar monetary order at the Bretton Woods conference.

Similar dynamics are generally overlooked in the management and subsequent fracturing of the Bretton Woods system. Extant explanations in terms of US power or ideological shifts do not pay much attention to gold or to policymakers’ struggles with the tensions inherent in a specie-linked currency. Rather than simply shedding a constraint on its power, the Nixon administration viewed cutting the link to gold as a temporary tactical move to achieve a more favorable institutional settlement. As we will show, Nixon and his associates were enormously concerned about the United States’ reputation as a reliable ally and leader, and until the mid-1970s, all American reform proposals included a continued role for gold. It took a decade for policymakers to renounce their habitual attachment to gold and the pivotal practice of referring money to it. This was not so clearly a manifestation of shifting economic ideas, either. To be sure, Milton Friedman advocated floating currencies and letting market forces determine their value.Footnote 21 Yet most economists and policymakers—even those later identified as neoliberals—disagreed and saw the Bretton Woods system and its tie to gold as a haven of stability, much as classical liberals had viewed the gold standard.

A Pivotal Practice in the Assemblage of International Monetary Relations

To remedy the blind spot on gold, we stress how situational contingencies and the inherited specie backing of money shaped the possibilities for monetary reform. We make the case for thinking about money at the international level in terms of a complex and evolving assemblage of institutions, practices, and material elements. Scholars have used the concept of assemblage to highlight the unique dynamics of phenomena constituted by heterogeneous elements, such as the right-wing alliance between Christians and capitalists, certain modalities of security governance, and even electric power provision.Footnote 22 In approaches associated with the new materialism in social and political theory, the concept emphasizes transactions between humans and material artifacts and the complexity of agency.Footnote 23 Although a recent arrival in the conceptual lexicon of international relations, assemblage thinking is at home in the practice and relational turn.Footnote 24 An assemblage is a multiplicity characterized by persistent tensions in the relations between its heterogeneous components, which are held together through practical activity.Footnote 25 Thus, an assemblage is unlike what IPE scholars call an “institution” or a “regime,” both in terms of its constituent parts and how they are linked together. The role of practical activity, rather than normative consensus or strategic realities, and their heterogeneous nature, as opposed to the relative homogeneity of regimes or institutions, tend to make assemblages more plastic and less clearly bounded. However, this does not mean assemblages are weaker forms of order; rather, the concept emphasizes different foundations for order.

An assemblage is also not simply any collection of artifacts, institutions, and actors linked by activity. Rather, it is more than the sum of its parts because it persists through time and has social and political effects independent of those of any of its separate constituents. One example is the development of anti-submarine warfare in the Second World War.Footnote 26 This required bringing together and stabilizing a diverse mixture of institutions, actors, and practices from military and scientific backgrounds. These were often significantly at odds with one another, or even “incommensurable,” due to rapidly advancing technologies and an absence of readily available institutional frameworks. Another prominent example from economic sociology is the constitution of financial markets.Footnote 27 Important market actors such as hedge funds rely on an “infrastructure of economic action” well beyond their trading rooms: computer networks and algorithms, overseas administrative and investment sites, collateral transfer arrangements, and so on. This assemblage not only enables the traders’ activities but also generates tensions as a result of cognitive biases and financial contagion or even crises.

It makes sense to think about money at the international level as an assemblage because internationally recognized money is unlike money at the domestic level, where it is an institutional reality built on the foundation of sovereign authority. No sovereign currency is recognized as exclusive legal tender at the international level. Instead, a shifting patchwork of practices, based for centuries around specie, has served the abiding interest in international trade and economic transactions. International money is an assemblage characterized both by its continuity and by its ambiguity, heterogeneity, and exceptions. The centrality of specie, and particularly gold, in international monetary relations was of long standing, despite frequent crises and misalignments—often unforeseen—that mark its history. Rather than critical junctures portending new eras of institutional stability, such recurrent crises point to the continuous efforts and creativity required to maintain the assemblage under changing circumstances, even in “normal” times. The history of Bretton Woods is a good example of this: its framers of 1944 would have had difficulty recognizing it in 1970.Footnote 28 Insofar as attempts to impose order actually tend to produce unexpected novelty, anchored by specific material realities, notions of institutional stability rooted in commonly held rules and norms reach their limit.Footnote 29

To characterize the role of gold in the assemblage of money at the international level, we build on social psychology and new materialist insights to develop the concept of pivotal practice. As we define it, a pivotal practice is a shared and largely unquestioned pattern of action that stabilizes relations between the disparate parts of an assemblage. For example, Gerald Berk emphasizes the importance of rotating scientists through combat missions in developing effective anti-submarine warfare. This rotation was central because “it was only sitting side-by-side and learning with pilots, navigators, radar operators, the magnetron, and the cathode ray tube screen” that effective submarine search strategies could be developed and disseminated.Footnote 30 Likewise, the reference of money to gold was a pivotal practice of international monetary relations for decades. Gold, its qualities, and the practices associated with it, oriented policymaking well after the gold standard was abandoned. At the same time, a pivotal practice is relatively open-ended. This follows from the characterization of assemblages as dynamic, evolving, and dependent for their persistence on practical activity. Although policymakers coordinated their practices with respect to gold, the forms of this coordination were ambiguous and contested. Because the relations in which gold was embedded allowed a variety of interpretations, policymakers continually reassembled the associations between money and gold.Footnote 31 The practice of referring the assemblage of money to gold thus shaped policy initiatives, but not in any single ideological direction. If referring money to gold was indeed a pivotal practice as we envision, then the assemblage of international money was not directed by a precise set of structures or ideas.

The pivotal practice of referring money to gold has both a material and a social-psychological dimension—just like scientific personnel rotation in anti-submarine warfare, which consisted of the mediation of military and scientific habits in the material context of actual operations—the vibrations of the plane, the performance of the magnetron, and the fatigue of the crew. These conditions were central to successful strategy development. Attention to the material dimension of practices is not entirely new in political science. Scholars have increasingly brought a concern with the role of material artifacts to bear on our understanding of topics such as diplomacy, security, and institution or state building.Footnote 32 Although the theoretical stances that inform these moves are diverse—including pragmatism, practice theory, science and technology studies, social network theory, and evolutionary theory—they share a commitment to analyzing how material elements combine with social consciousness to produce the world we experience.

We understand the material dimension of a pivotal practice in the sense articulated by new materialist scholarship: that matter—in this case, gold—is not just a passive object on which social relations act or have effects. That is, individuals’ relationships to objects are not merely instrumental. The conventional dichotomy between matter and ideas obscures the active participation of material artifacts in shaping actors’ worldviews and social relations.Footnote 33 Agency is therefore not the property of individuals, classes, or states, but is distributed across human and natural/material domains. This is what Jane Bennett calls the “vibrancy” of matter: the ability of objects to “animate, to act, to produce effects dramatic and subtle.”Footnote 34 Understanding how this capacity of objects is constituted through transactions between humans and material artifacts is the focus of Bruno Latour's project of “reassembling the social.”Footnote 35 As Mike Bourne puts it, “things might authorize, allow, afford, encourage, permit, suggest, influence, block, render possible, forbid and so on … You only wanted to injure but, with a gun now in your hand, you want to kill.”Footnote 36 At a hedge fund, for example, trading decisions—including herd behavior—are greatly influenced by tools, such as computer terminals and financial news services, that furnish information to traders.Footnote 37 A form of this influence is also expressed in the aphorism, “If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.”

A new materialist perspective thus prompts us to think about the active role of gold (and other objects), as opposed to the “old” materialist view of gold as merely an object of instrumental manipulation by powerful interests. The physical characteristics of gold and silver were central to the origin of money and significantly enabled long-distance exchange. According to Christine Desan, “the token representing the unit of account must be both durable and difficult to imitate … One solution is a token made of material that is rare, imperishable, and takes skill to work.”Footnote 38 The value of the metal lay partly in the fact that it facilitated exchange between different jurisdictions because each could coin it into their own currency.Footnote 39 That is, “traders who moved between worlds used silver or gold, not money,” and in so doing, merchants acted “as translators in a largely disjointed system” of inconvertible sovereign currencies.Footnote 40 Desan's characterization nicely evokes the practical linkages that maintained the assemblage of international money and made international exchange possible. The eventual rise of paper currency did little to dispel the centrality of specie. Even a century after the development of paper currency in Britain, Adam Smith held that commerce and industry were not as secure “suspended upon the Daedalian wings of paper money as when they travel about upon the solid ground of gold and silver.”Footnote 41

In addition to pointing to the material foundation of money in specie, Smith's attitude speaks to the social-psychological dimension of the pivotal practice of referring money to gold. This aspect originates in the habitual nature of practice, as theorized by pragmatist philosophy and buttressed by recent scholarship in psychology. Habits are individual dispositions—ingrained ways of perceiving the world and acting in it—that have a tendency for self-perpetuation. They are what John Dewey called “conditions of intellectual efficiency” that exclude potential alternatives.Footnote 42 Many habits are also intersubjective, reinforced by the socialization of individuals in groups, and therefore central to the durability and intelligibility of collective practices.Footnote 43 This social-psychological quality of a pivotal practice contributes to its resilience—even for people who have no stake in it. In the heyday of the gold standard, one did not need to own gold to understand it as the foundation for money. People's habits change over time, but it often takes a longer process of habituation.

By the end of the eighteenth century, the status of gold as the specie of reference was firmly established at the domestic level in England, a country that dominated global trade and financial flows. This made its adoption as the foundation of the international monetary order a seemingly natural extension. Classical liberal doctrine therefore proclaimed gold an inherent standard of value, independent of the state actions that actually engineered specie-backed money.Footnote 44 By the turn of the twentieth century, gold was central to the global understanding of what money was. As Polanyi put it: “Belief in the gold standard was the faith of the age … the one and only tenet common to men of all nations and all classes, religious denominations, and social philosophies.”Footnote 45 No longer a contested object of classical liberal advocacy, the gold standard then mustered broad social-psychological appeal.

We understand the material dimension of practices to be closely linked to the social psychology of habits and conventions. This a perspective with a long history: as Bennett notes, Dewey himself suggests that “a political system constitutes a kind of ecosystem” insofar as “he highlights the affective, bodily nature of human responses.”Footnote 46 In fact, habits are for Dewey constituted in part by the active participation of the material context of action. Foreshadowing the concerns of new materialist scholarship, Dewey emphasized the role of available means in constituting the ends of action. For decades, gold thus played a referential role in the international monetary assemblage—that is, in the linkages between central banks, currency markets, treasuries’ reserve positions, vaults, ledgers, the IMF, speculators, the mining industry, and myriads of economic transactions. Gold was not something held at arms’ length, a convenient object of manipulation, but constitutive of monetary relations through practices and habits from which it was inseparable.

The practice of referencing money to gold meant that gold's scarcity or abundance not only conditioned action but, by embodying value, also shaped actors’ perceptions of the possible in responding to crises. Thus, gold can be described as an active participant in constituting and maintaining the assemblage of international money. In fact, the history of international monetary relations makes little sense if we assign gold a passive role. Alternatives are always available—for example “antiques,”Footnote 47 or even just silver, another metal that served as money over longer historical periods than gold. With their instrumental approach to objects, conventional perspectives suggest that policymakers could have done away with gold much earlier. Keynes's “bancor” is the most famous example of an international monetary unit divorced from any reference to gold, and the invention of special drawing rights in a sense concretized Keynes's idea in the 1960s. Yet the capacity to act was intimately tied up with gold, which helps explain why these alternatives were marginalized. Finally, gold's demonetization should have rendered it a commodity like any other, and a few countries did liquidate their gold holdings. Canada sold almost all its gold in the 1990s, and the UK sold a significant portion of its reserves between 1999 and 2002, but the rest of the G7 held onto their gold (Figure 1). To be sure, gold is frequently cited as a hedge against inflation, yet the evidence for this is rather inconclusive—especially in high-inflation periods such as the early 1980s. A strictly economic logic is therefore insufficient for explaining gold's persistence as a monetary reference decades after its official demonetization.

We can better comprehend the effects of the pivotal practice of referring money to gold if we consider international money as an assemblage. As products of continuous activity, assemblages are inherently dynamic and subject to persistent tensions between their heterogeneous parts. Actors attempt to address a particular tension by rearranging the relations among the components of the assemblage. This leads to the emergence of new properties, and thus new challenges and new tensions. These inherent tensions and the continuous attempts by actors to manage them drive the evolution of assemblages. Thus, in the assemblage of international money, a significant source of tensions was the deflationary bias of the reference to gold. Under the classical gold standard, policymakers typically resolved these tensions by deflation, shifting adjustment costs onto the laboring classes. This was no longer politically tenable after the incorporation of workers into democratic politics, and Bretton Woods was in part an attempt to finally resolve such tensions by insulating domestic economies. The continued referencing of money to gold, however, meant that gold still affected how policymakers perceived problems and possibilities. With the long postwar boom, tensions in the assemblage resurfaced. Policymakers then sought to ease these tensions by reassembling the relations between gold and money in novel ways. This process eventually led to the demonetization of gold, which in turn led to new tensions. The mechanism here is best thought of as causal but nondeterministic—as a historically transposable way of thinking about change, but necessarily tied to context.

While stressing the persistent importance of gold, we will now focus on three specific episodes where the pivotal practice of referring money to gold was crucial in reconstituting the assemblage of international money: the negotiation of Bretton Woods; the effort in the 1960s to quell speculation against the gold-backed dollar; and the closing of the gold window and its immediate aftermath. In each of these cases, the social-psychological and material characteristics that made referring money to gold a pivotal practice of the international monetary assemblage significantly impacted the reconstitution of monetary relations. Importantly, they did so in a way that does not comport with an instrumental understanding of the role of objects in either a realist or a constructivist framework. Our empirical focus is on the considerations of senior policymakers and negotiators, although we occasionally refer to other actors to situate their actions and decisions. Across our cases, we highlight how actions and claims at key moments do not comport well with existing accounts of monetary relations.

The Lure of Gold at Bretton Woods

The Bretton Woods Agreements are remembered today as the official rejection of what Barry Eichengreen (and Keynes) called the “fetters” of gold, after the rising tide of democracy had rendered unacceptable the gold standard and its painful episodes of deflation.Footnote 48 Realists then stress the United States’ new role as the hegemonic power underwriting the free world, while constructivist scholars typically highlight the importance of new norms and ideas in the US-led order. Yet, as we will show, the reference to gold remained a pivotal practice, a fact that challenges the conventional focus on Bretton Woods’ shift to “US hegemony” or “embedded liberalism.” In the eyes of policymakers, gold was a guarantee of stability and in many ways also an equalizer of power, rather than a fig leaf for US hegemony. Furthermore, the influence of Keynesian ideas, though real, remained sharply limited on the topic of gold.

For policymakers at the time, the dollar stood for gold—not just for US power, as realists tend to assume. In March 1945, White testified in Congress that “to us and to the world, the United States dollar and gold are synonymous.”Footnote 49 White thus approached the Bretton Woods negotiation with a more positive view of gold than Keynes's, even as he agreed with Keynes to rule out a return to the classical gold standard. Yet neither of the two main architects of Bretton Woods advocated a radical break from gold.Footnote 50 Both believed in the stabilizing virtue of gold, in particular for exchange rate stability. Keynes's proposal was to replace gold with an international fiat currency (the bancor) and thus, over time, to “de-monetize gold.”Footnote 51 White's much less radical plan envisioned a “gold exchange standard” in which “the US dollar was to be the de facto core currency”Footnote 52—that is, replace sterling as the currency on which other currencies would be pegged. But there is no indication that White saw the dollar as a full-fledged alternative to gold. While he did not advocate gold as an international currency, he favored an international currency “based on some gold reserve.”Footnote 53 Ultimately, he envisioned the dollar as a functional substitute for gold, similar to sterling under the gold exchange standard of the interwar period.

The reference to gold thus remained a pivotal practice in the reformed assemblage of international money of the postwar world. From a social-psychological perspective, gold was reassuring as a guarantee of stability in light of its historical role as the basis for money. In the negotiations, it also became clear that the US would not seriously contemplate Keynes's bolder plan of a new international fiat currency and that the dollar—rather than sterling—would be at the core of the new system. Against Keynes's initial plan and despite his later assertion to the contrary, Bretton Woods was widely viewed at the time as a reestablishment of the interwar gold exchange standard, but with the dollar rather than sterling as the new gold-convertible core currency.Footnote 54 Later scholars have focused mostly on US-led “embedded liberalism” and the novelties of Bretton Woods—capital controls, adjustable pegs, and the IMF—as well as its break with the orthodox gold standard. Yet the Bretton Woods conference really only reconfigured the linkages between currencies and gold. The dollar remained convertible into gold at the price Roosevelt had established in 1934, and the IMF mediated the linkage of other currencies to gold.

From a new materialist perspective, the reference to gold was also attractive as a pivotal practice because it did not require a potentially destabilizing change in social conventions and material realities. As an apparently neutral material, gold heralded a symmetry in international monetary relations—contrary, again, to the later realist reading of Bretton Woods as the establishment of US hegemony. Unlike untested fiat arrangements such as Keynes's bancor, gold gave the system a material foundation that was literally more solid than reciprocal promises among states with divergent interests. Every state had to negotiate exchange-rate adjustments with its partners at the IMF, and even the United States was bound by its commitment to honor the gold convertibility of the dollar. Moreover, every state's “quotas,” and therefore its voting rights on the IMF board, hinged on the amount of gold it deposited with the IMF.

For the United States, as the world's greatest creditor and accumulator of gold in 1944, a system centered on gold ensured a continuity of debt obligations. This was a primary US concern, especially vis-à-vis the United Kingdom, the most highly indebted country in the world at the time. While the UK was indebted in (gold-convertible) dollars to the United States, the “dollar shortage” problem that it and other countries faced was dwarfed in 1944 by the more immediate problem of “sterling balances.” As Barry Eichengreen points out, “by the end of the war, the accumulated sterling balances of central banks and governments exceeded their dollar balances by a factor of two to one.”Footnote 55 The global demand for dollars therefore provided only limited leverage to the United States for asserting the primacy of the dollar at Bretton Woods. In fact, the architecture of Bretton Woods assumed that the “dollar shortage” would be a temporary problem—and that was also Keynes's view.Footnote 56 By contrast, many nations of the British Commonwealth had accumulated large sterling-denominated credits received in payment for Britain's wartime imports. The Bretton Woods transcripts, recently discovered and published in 2012, show that this question “kept cropping up” during the conference.Footnote 57 The US government did not want to provoke a British default on its debts by forcing a return to sterling convertibility—but it did want to make sure that, over time, Britain would repay its debts in hard currency. The agreements’ constant reference to gold and their late incorporation of an explicit role for the dollar must be understood in that context. It was not the dollar as such that many Bretton Woods delegates valued over sterling; rather, they valued its perceived superiority as a “gold-convertible currency.”

Far from being only a material resource in the hands of the powerful, as realists would have it, gold also provided protection for the weak. Even states that were weaker and had less gold than the United States had an interest in preserving a gold-based system. This active role of gold in the postwar assemblage of international money can be better understood if we first consider the UK example. Despite the fragility of sterling's position, gold was attractive to British officials who were concerned with the risk of beggar-thy-neighbor policies on the part of the United States. They derived comfort from the material threat of gold depletion acting to discipline US economic policies.Footnote 58 The dollar's link to gold was “a discipline on the policies of the reserve center (i.e., the US), analogous to the discipline exerted by the threat of reserve depletion in other countries.”Footnote 59 Gold thus materialized a pledge of financial responsibility by the United States, whereas a massively indebted Britain could no longer afford to make that pledge.

Perhaps even more striking, other countries in much weaker positions than Britain also supported the privileged status of the dollar under Bretton Woods because of its convertibility in gold. The transcripts reveal that the hugely consequential decision to grant the dollar its privileged status resulted from a request by India. The term “gold-convertible exchange” first appears in the early draft of the Bretton Woods Agreements, which did not mention the dollar. In an annex to the draft, it was defined as “financial assets that can be sold for gold, which implies that the assets are denominated in currencies that do not have exchange controls on capital transactions.”Footnote 60 In July 1944, however, the US dollar was the only currency that remained externally convertible into gold. During the conference, the delegate of India requested a clarification: “I think it is high time that the USA delegation give us a definition of gold and gold convertible exchange.”Footnote 61 In response, the US delegate answered, “On the practical side, there seems to be no difference of opinion, and it is possible for the monetary authorities of other countries to purchase gold freely in the United States for dollars … It would be easier … to regard the United States dollar as what was intended when we speak of gold convertible exchange.”Footnote 62 According to the conference transcripts, Dennis Robertson, a member of the British delegation, then proposed to amend the text by substituting “dollar” for “gold-convertible exchange”—and nobody at that point objected.

On its face, India's deference to the United States on this issue is surprising. In 1944, India was still a British colony, and had virtually no gold. It did hold a sterling balance of £1.5 billion, which raised concerns about Britain's ability to repay.Footnote 63 Yet there is no obvious reason why India should have desired a gold-backed currency like the US dollar as a core currency of the new system—unless we account for the reference to gold as a long-standing pivotal practice of the international monetary assemblage. By this point, the connection between money and gold was deeply rooted, both socially, as Polanyi notes, as well in the practices of international monetary relations. The constructivist reading of Bretton Woods as a victory of “embedded liberalism” tends to overstate the influence of Keynes's dismissal of gold as a “barbarous relic.” Even before the Bretton Woods conference, the British chose to “defer to the American view” and to abandon Keynes's bancor proposal. This was in recognition of White's “difficulties with Congress” and suspicion of replacing the gold-backed dollar with a “phoney international unit”Footnote 64—that is, one that, to paraphrase Smith, did not “travel about upon the solid ground” of gold. Banking circles and the US Congress, in particular, were still wedded to gold.Footnote 65 Moreover, an instrument like bancor was—like Eichengreen and Mathieson's suggestion that antiques might be substituted for gold—detached from the practical experience of policymakers.

To be sure, Keynes's ideas were influential, as conference delegates’ concern about the potential deflationary bias of a metallic standard foreclosed a return to the classical gold standard. In its bilateral dialogue with the United States, the British government, advised by Keynes, had been adamant about avoiding automatic mechanisms of deflation, which risked “crucifying” domestic economies on a “gold cross.”Footnote 66 But Keynes remained opposed to giving the dollar privileged status at Bretton Woods, and found out about it only after the conference was over.Footnote 67 Robertson's willingness to endorse a gold-convertible dollar suggests that the British delegation was not fully behind Keynes.Footnote 68 Ironically, Keynes's opposition to a rigid gold standard may have ultimately played in favor of ratifying a gold-convertible dollar. Clearly, the link of the dollar to gold was not as rigid as under the gold standard, since Roosevelt had devalued the dollar and ended its domestic convertibility.Footnote 69 From this perspective, the Bretton Woods adoption of the dollar as a core currency, alongside gold, could be seen as reassuring.

The Persistence of Gold in the Bretton Woods Era

After the Second World War, world trade recovered, and dollar-denominated US aid enabled the postwar reconstruction of Europe and Japan. By the 1960s, the Bretton Woods system was gripped by tensions that became known as the “Triffin dilemma.” While the US supplied dollars to a rapidly growing Western bloc and went into chronic balance of payments deficit, the supply of gold grew much more slowly. The US could either slow down the dollar flows, at the risk of killing the postwar boom, or sustain them, at the risk of inflation and an erosion of confidence in the dollar. According to Barry Eichengreen, “these problems should not have come as a surprise. There was an obvious flaw in a system whose operation rested on the commitment of the United States to provide two reserve assets, gold and dollar, both at a fixed price, but where the supply of one was elastic and the other was not. The economist Robert Triffin had warned of this problem in 1947.”Footnote 70 Benjamin J. Cohen formulates a similar critique of Bretton Woods and the apparently “Panglossian” optimism of the negotiators, and Mark Blyth likewise claims that “the Bretton Woods institutions were in fact a paper standard masquerading as a gold standard.”Footnote 71

With the benefit of hindsight, such assessments seem reasonable. Yet they also suggest that actors at the time severely misjudged the situation, or that the reference to gold was merely a mask for US hegemony or embedded liberalism. By contrast, our analysis strives to “follow the actors themselves,” as Bruno Latour recommends, tracing the transactions between them rather than assuming the presence of concealed social forces or a categorical truth. The situation of the international monetary assemblage actually precluded an awareness of the problem during the Bretton Woods conference. The problems of the 1960s, even if obvious in retrospect, could not be so easily anticipated in 1944. Although Robert Triffin saw in 1947 that “fundamental disequilibria” may accumulate in the absence of a strong coordination of international monetary policies,Footnote 72 his articulation of what became known as the Triffin dilemma came only in a 1960 book.Footnote 73 The 1947 article arguably foreshadowed the Triffin dilemma,Footnote 74 but only in general terms. It not only failed to mention the fundamental problem of the dollar's equivalence to gold in the Bretton Woods agreement, but also suggested rather optimistically that balance of payments difficulties could be remedied with international and IMF assistance. Last but not least, Triffin knew he was being a contrarian—like Keynes—when he questioned the “deep-rooted tradition” that viewed currencies as effectively backed by gold.Footnote 75

The more prevalent view in the mid-1940s was that the dollar, as the only currency convertible into gold, was “as good as gold.” At the Bretton Woods conference, White dismissed as “nonsense” the notion that the United States might want to change the gold value of the dollar.Footnote 76 Robertson, the British delegate who endorsed the dollar on par with gold, was following “the conventional wisdom: in 1944 the dollar was the only currency one could freely convert into gold.”Footnote 77 In his March 1945 testimony to Congress, White asserted that “there is no likelihood that … the United States will, at any time, be faced with the difficulty of buying and selling gold at a fixed price freely.”Footnote 78 He and other Bretton Woods delegates could not easily foresee future developments that seem obvious to us. They could see the world only as it was then, when the idea of a fiat currency not backed by gold seemed esoteric or even “phoney,” as British diplomats themselves acknowledged. For most contemporaries, the Bretton Woods accords’ assemblage of international money around gold and its dollar equivalent, and their pervasive reference to gold, simply made practical sense.

By the 1960s, however, the context had drastically changed, and new tensions had emerged with the dollar overhang, itself a product of how policymakers had reassembled monetary relations at Bretton Woods. US deficits and inflation undermined trust in the dollar. In contrast, gold retained its status as a transcendent foundation of value—a status acquired over centuries and supported by gold's unique material characteristics and social-psychological appeal. As French president de Gaulle put it, “there can be no other criterion, no other standard than gold. Yes, gold, which does not change in nature, which can be made into bars, ingots, or coins, which has no nationality, which is held eternally and universally as the immutable and fiduciary value par excellence … It is a fact that even today no currency matters, if not through its relation, direct or indirect, real or assumed, to gold.”Footnote 79 De Gaulle's speech was influenced by Jacques Rueff, an advocate of a return to the classical gold standard and a member of Hayek's Mont Pélerin SocietyFootnote 80—another indication that “embedded liberalism” was not as pervasive as many constructivist analyses of that period imply. Translating words into action, France then adopted a policy of converting its dollar reserves into gold, which further undermined confidence in the dollar.

In de Gaulle's personal view as well as in his public rhetoric, gold as a metal had intrinsic qualities that preserved it from political manipulation—by the United States or any other government. According to verbatim notes taken by his minister and long-time confidant Alain Peyrefitte, de Gaulle told him: “Only gold, because it is unalterable and it inspires confidence, escapes the fluctuations of the so-called gold exchange standards and of the selfishness of national policies.”Footnote 81 The fact that de Gaulle expressed strikingly similar views in private suggests that his public rhetoric was not merely a grandiose justification for a French bet against the US dollar. Peyrefitte further comments that, for de Gaulle, “Gold is a police force. It is extra-political.”Footnote 82 Ultimately, de Gaulle's reasoning was based on a logic that J.P. Morgan would not have disowned. As the French president once blurted out: “Enough with reserve currencies! We are not going to invent more of them! There is gold. Anything else is just stories made up to screw us.”Footnote 83

In more analytical but equally stark terms, the Triffin dilemma posed the question of the relationship between gold and the dollar and therefore the continuing reference to gold as a pivotal practice of the international monetary assemblage. Policymakers sought to evade the dilemma while maintaining this reference with the introduction of new devices and practices. The changes they made aimed to defuse mounting tensions in the assemblage of international money. Robert Roosa, the treasury undersecretary for monetary affairs under Kennedy, developed foreign-currency-denominated bonds to lessen the pressure on US gold reserves. Central banks established swap lines of credit to provide alternate sources of liquidity. And Japan and Germany agreed to support the system by holding on to large amounts of dollars rather than converting them into gold.Footnote 84 Two initiatives in particular reinforced the visible, practical linkage between gold and money. In 1961, in response to a spike in the price of gold (brought on by fears the US would follow inflationary policies after Kennedy's victory), the major gold-holding nations established the London Gold Pool. Pool members’ central banks bought and sold gold in the open market to stabilize its price at the official mark of USD 35 per ounce.Footnote 85 And in June 1962, Kennedy approved the establishment of a “gold budget” for federal agencies’ foreign expenditures, overseen by a new inter-Cabinet committee.Footnote 86 Discussions of the gold budget invariably called for spending less abroad to reduce the outflow of dollars and thus to consolidate the United States’ gold position.

Scholars have often interpreted moves like these as rear-guard actions to preserve an anachronistic reference to gold in “a paper standard masquerading as a gold standard.”Footnote 87 In light of the continuing significance of the reference to gold for Bretton Woods, however, these policies make more sense as an expression of gold's centrality and its implication in the assemblage of international money. By performing the pivotal practice of referring money to gold in novel ways, policymakers preserved specie backing under changing circumstances while reconfiguring the international monetary assemblage. This provided space for continued growth while keeping gold at the center of the Bretton Woods regime. The only alternative seemed worse: unanchored fiat currencies and a return to the chaos of the 1930s. Through the 1960s, the monetary policies of de Gaulle and his American counterparts were at cross purposes, but this antagonism was based on a shared understanding of the stabilizing virtues of gold. There were many ways in which de Gaulle could frustrate US policies, and thus underscore the decline of the Bretton Woods regime. The fact that he chose gold as a lever speaks to its ability to induce action, about which realist as well as constructivist scholars have little to say.

These activities affirmed gold's pivotal role in the assemblage of international money. In fact, the use of the gold pool—with its direct linkage to gold—to steady the system stands in contrast to proposed changes whose linkage to gold was much more tenuous. These innovations, such as the creation of special drawing rights (SDRs) to provide liquidity and ease the pressure on gold and the dollar, were marginalized. The SDR represented a conceptual leap in a world where specie-backed currencies had been the norm for centuries. The notion that currency in circulation did not represent a claim for any specie against the issuer was considered “a genuine breakthrough in monetary thinking” at the time.Footnote 88 The development of SDRs opened the possibility for a smooth transition to a system in which the SDR served as a reserve alongside gold.

This development, however, would not come to pass. Major countries took action to defend the link to gold, and many observers dismissed the grant-like SDRs as “manna from heaven.”Footnote 89 As a synthetic asset without backing, “it was widely suspected as ‘funny money.’”Footnote 90 The idea of untethering currencies from gold as a solution to pressing problems thus did not fare any better than Keynes's bancor had in 1944. The SDR's unorthodoxy likely doomed it in the eyes of practitioners who were immersed in monetary transactions linked to gold and habitually associated stability with specie backing and nonconvertible currencies with economic dislocation.Footnote 91 The cool reception of SDRs illustrates the social-psychological attachment to gold, which practitioners habitually associated with stability, as well as gold's superior materiality as a foundation of value.

Through the 1960s, the superior materiality of gold in comparison to paper alternatives was only confirmed, over and above evolving power relations and ideas. Continued US deficit spending, rising industrial gold use, and a leveling-off of gold production all put heavy demands on the monetary gold stock.Footnote 92 The gold pool became a net seller of gold from 1966 on, especially as sterling later weakened and the market demand for gold increased.Footnote 93 A proposal then surfaced to salvage the gold pool by reimbursing pool members who sold their “real gold bars” with “gold value certificates.” Yet European central bankers “immediately and flatly rejected” this proposal.Footnote 94 In a run on gold from December of 1967 to March of 1968, the gold pool lost 3 billion dollars’ worth of gold, which prompted its closure on 15 March 1968.Footnote 95 This struggle between policymakers and speculators took place amid a common understanding of the centrality of gold as an inescapable monetary reference.

The closing of the gold pool and the crisis of 1968 have largely been overlooked in postwar history.Footnote 96 Yet they dramatically highlighted the key tension in the assemblage of international money of the dependence of the Bretton Woods regime on the amount of gold available. International finance was hostage to a natural material that was available in only finite quantities. Decades after the official end of the gold standard, Polanyi's critique of gold as a “fictitious commodity” had come back to haunt the Bretton Woods regime.Footnote 97 Unlike commodities that were produced for sale on the market, gold's supply and demand could clearly not be regulated by market mechanisms alone.

By closing the gold pool, policymakers sought to defend monetary gold stocks, but in doing so they undermined the referencing of money to gold as a pivotal practice in the evolving assemblage of international money. The Washington Agreement, reached after the gold pool was closed, stipulated that the central banks of the gold pool countries would not buy or sell gold on the market. Instead, they would exchange it only among themselves at the official price of USD 35 per ounce. This separated the gold market in two, and “the world switched to a de facto dollar standard.”Footnote 98 Dollars held abroad in private hands were no longer convertible into gold. While the dollars held by foreign central banks were still convertible at the official price, it was clear that such moves would threaten the system.Footnote 99 The tensions in the assemblage of international money caused by the gold backing of the dollar were effectively eased by a greater reliance on fiat currency. This easing of pressure on monetary gold stocks was only temporary: the Washington Agreement purchased short-term stability yet undermined the system in the longer term. The system was now held together only by commitments not to follow through on the further conversion of dollars to gold—commitments that even close allies of the US, like Britain, would be unable to hold in 1971. The end of the gold pool meant that policymakers were no longer involved in transactions in gold, which had been vital to the operation of the system, and monetary gold became inactive in central bank vaults. This reassemblage was mirrored by the declining administrative interest in gold: the last mention of the “gold budget” in the Foreign Relations of the United States series is on 7 November 1967.Footnote 100

Critiques of the “rigidity” of Bretton Woods have usually focused on the lack of adjustment of currency parities over time. Focusing on gold, however, illustrates an underappreciated way in which the system was rigid: the ingrained habits of policymakers that precluded consideration of alternative modes of action. Despite the innovations of the 1960s, Bretton Woods was still tethered to the available monetary gold stock. During crises, policymakers circled the wagons around the remaining link between the dollar and gold rather than developing constructive alternatives. A memorandum to President Johnson as pressure mounted in late 1967 put these difficulties in stark terms. After listing the challenges to the official price of gold and the taxes and other measures needed to stabilize the situation, it ended with an almost desperate plea: “Is all this worth doing just to preserve the gold-dollar link?”Footnote 101 This rhetorical question reveals the capacity of gold to circumscribe policy orientations—a form of agency that evidently puzzled policymakers themselves. As Robert Solomon notes: “It is hard today to put ourselves in the shoes of officials who feared—deeply feared—that suspension of dollar convertibility would lead to chaos in international financial relations.”Footnote 102 Policymakers could not stomach all the contortions needed to stabilize the system, but they also could not simply walk away from gold. The social-psychological and material qualities of gold—its long history as the foundation for currency and its intimate amalgamation of functionality and aesthetic appeal—thus explain the difficulty of moving toward a post-gold version of the Bretton Woods regime.

Gold as a Haven of Stability in an Unstable World

Richard Nixon's decision to end the dollar's gold convertibility is often seen as a watershed. According to a realist reading, it was the end of the United States’ underwriting of Bretton Woods and of “hegemonic stability” in favor of a more nationalist outlook; while according to many constructivist scholars, it was the beginning of a shift to “neoliberal” economic ideas after the long era of “embedded liberalism.” Our account, by contrast, highlights important continuities with the preceding and subsequent periods, and the importance of gold as a thread to make sense of these continuities. In fact, most policymakers at the time saw the move to floating currencies as temporary and unwelcome because they worried about both its foreign policy consequences and its economic consequences. The reference to gold ceased to be pivotal in the 1970s, but gold is still a unique material with monetary consequences in the assemblage of international money.

The continuing instability of international monetary relations after Nixon's election confronted him with the need to make important decisions. Paul Volcker, as treasury undersecretary for international affairs, developed three policy options: negotiating changes to the Bretton Woods framework, ending the convertibility of the dollar, or raising the price of gold. Policymakers favored negotiations, with ending convertibility considered a fallback option.Footnote 103 As circumstances worsened in spring of 1971, Volcker recommended letting a foreign exchange crisis develop to highlight the need for reform. The United States could then temporarily eliminate dollar convertibility to pressure partner nations. Volcker thought of this suspension not as an end in itself, but as a tactic that would provide leverage for the US to negotiate a transition of Bretton Woods toward more flexible pegs—not floating exchange rates.Footnote 104

Top economic officials in the Nixon administration—including those later labeled in constructivist accounts as neoliberal—were all wary of letting exchange rates float without a link to gold. They favored not a radical revision but greater flexibility in the institutional framework of Bretton Woods, namely the wider exchange rate margins and transitional floats that the US would propose to the IMF in July 1971.Footnote 105 Their common point of reference, like that of most practitioners, was the instability of floating exchange rates in the 1930s—a world of competitive devaluations and global economic fragmentation.Footnote 106 That was especially the case for Arthur Burns, the chairman of the Federal Reserve (and once mentor to Milton Friedman), and of Volcker, the man who later “jumped on the monetarist bandwagon” as chairman of the Federal Reserve in the 1980s.Footnote 107 As late as 1969, Volcker himself had dismissed the notion of floating exchange rates as a mere concern of academics.Footnote 108 When Nixon decided in 1971 to close the US gold window, Burns, who wanted only a devaluation of the dollar with respect to gold, “opposed this decision until the last minute.”Footnote 109 Even the chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors, Paul McCracken, whose views were close to Friedman's, noted that while fixed rates would likely be unworkable, “the recent practice of unregulated exchange rate changes and floating disrupts the monetary order.”Footnote 110 Accounts that emphasize the importance of neoliberal ideas therefore provide little leverage on the issue of gold.

Nor is it the case, as argued in realist accounts, that the United States under Nixon adopted a unilateral line. Once the link to gold was cut, Nixon and members of his administration feared that others would regard a “go it alone” policy as irresponsible. In fact, Nixon preferred to show constructive leadership and to re-establish an institutional foundation for international monetary relations.Footnote 111 Here our analysis sharply differs from Gowa's realist account, in part because of her limited access to federal documents at the time and because her analysis ends with the closing of the gold window. Immediately following Nixon's suspension of gold convertibility on 15 August 1971, Volcker stressed to his European and Japanese counterparts that the US would float the dollar “for a limited time” and would be “ready at the appropriate time to go back to a system of fixed rates but with some changes, perhaps along the lines of our proposals on wider bands and temporary floats.”Footnote 112 Volcker's own mentor was Roosa, who opposed Friedman's push for floating exchange rates and in the early 1960s had devised methods to ease pressure on the monetary gold stock.Footnote 113

Cutting the last links to gold removed what up to then had served as an anchor for policy decisions, pitching policymakers into an unknown world. Even critics on the left staunchly defended gold. George McGovern commented, “It is a disgrace for a great nation like ours to end in this way the convertibility of the dollar … By this act we will become the economic pariah of the world.”Footnote 114 Unlike closing the gold pool, which formally preserved gold's position in the monetary system, closing the gold window—even temporarily—meant that the very status of gold became contested. This step effectively ended the ability of references to gold to serve as a pivotal practice in linking together the disparate parts of the monetary assemblage, thereby transforming it. Exchange-rate volatility increased considerably, prompting conversations among American policymakers about the desirable reconstitution of a “system.”Footnote 115 Their plans remained hazy, however, reflecting a lack of determinate structural pressures or ideological convictions. The outlines that emerged testify to the power of habit, in that the details they did contain were a straightforward evolution of the familiar institutions, including a role for gold.

The United States had not formulated specific objectives for negotiations on the future of monetary relations when convertibility was suspended.Footnote 116 More than a month later, policymakers finally cobbled together a loose two-phase negotiating strategy. Although “limited convertibility” of the dollar (a term left undefined) might be granted in the first phase in exchange for immediate exchange-rate adjustment and concessions on trade and defense burden sharing, a return to gold convertibility would not be promised until the second phase. This leverage would be used to achieve a broader but still vague “reform” of the system, in line with the objectives of the first phase.Footnote 117 In other words, the Nixon administration thought a modified status quo ante, including a role for gold, would be acceptable. Pending a broader settlement, the Smithsonian Agreement, concluded in December 1971, revalued several currencies, widened the bands around par values, and devalued the dollar relative to gold. Gold convertibility was not resumed, however, and the world officially moved to a dollar standard.

Questions over the durability of the Smithsonian Agreement quickly arose as negotiations continued. After replacing the more abrasive John Connally as treasury secretary, George Shultz presented a proposal to the IMF in September of 1972 that built on previous US proposals, stressing greater flexibility and a continued role for gold alongside SDRs, and recommending a symmetry of obligations between creditor and debtor nations.Footnote 118 These proposals for evolutionary change, aired a year after the closing of the gold window, speak to the persistence of habit regarding the sources of stability in the monetary system. They also presented the least disturbance to the practices that linked the disparate parts of the international monetary assemblage. Members of the administration initially favored these proposals, rather than the alternative strategy of forcing currencies to float by failing to support the Smithsonian Agreement. Even Shultz associated the latter strategy with the “risk of encouraging already widespread beliefs that ‘we don't care.’”Footnote 119 Nixon also did not want the United States to relinquish leadership through a policy of benign neglect, arguing that this would be “just too much of a ‘To hell with the rest of the world’ as a policy.”Footnote 120

Within a year, the suspension of gold convertibility, though it was initially carried out for tactical purposes, became the new basis for monetary relations. In March 1973, as more countries floated their currencies, American policymakers finally abandoned efforts to uphold fixed rates. Even monetarists who had long advocated floating exchange rates remained concerned about a disjointed international monetary assemblage. Shortly before the final decision to jump to floating currencies, Shultz noted that such a system would be “at loose ends with itself.”Footnote 121 By then, however, policymakers had more than a year of experience with unanchored currencies, and the world economy had not collapsed. This experience undercut the power of the analogy to the chaotic 1930s.Footnote 122 As Volcker later remarked, “the world didn't come apart.”Footnote 123 After the shift to floating rates, the American negotiation position sought to avoid any “tendency” to “place gold back in the center of the system,” for fear that it would develop in a more rigid direction.Footnote 124 The Europeans coalesced around the French advocacy of a role for gold in clearing transactions among themselves.Footnote 125 American policymakers differed on how far to accommodate the French, and saw “little logic” in the French position: France was concerned about inducing inflation by issuing SDRs, but unconcerned about the potential inflationary effects of approving transactions in gold at a market price way above the official price.Footnote 126 Burns, however, saw “no economic reason” to rush to agreement on gold while it remained immobilized in bank vaults at the official price.Footnote 127

These debates over gold and its proper place underscore its vitality, which was not approached from a strictly rational economic perspective. US policymakers knew that gold sales were often scorned as “the dissipation of our last patrimony,”Footnote 128 and Nixon sympathized with the French, agreeing that “gold has a mystique.”Footnote 129 As French president Pompidou pointedly asked in May of 1973: “As to SDRs, they are based on what? What is their value other than a symbolic value? … Who will give gold in return for SDRs?”Footnote 130 Gold remained for him, even then, the only suitable material as a basis of value. Pompidou noted proposals by French economists to base the value of money on raw materials, but commented that “no one else believes in that.”Footnote 131 This wariness of the SDR was also present on the American side.Footnote 132 As American policymakers noted, “There is, in fact, still a considerable emotional attachment to gold as a monetary asset, and a basic distrust of bank or paper money not having intrinsic value.”Footnote 133 The lack of confidence in “paper money” (as opposed to “real” money) highlights the specific materiality of the problem.

The “basic attraction” of gold, as noted by American policymakers, gave the yellow metal a power to create tensions in monetary relations.Footnote 134 Fearing a return to the rigidity of the gold standard, policymakers found a solution: to immobilize gold indefinitely, like kryptonite, in central bank vaults by keeping its official price steeply discounted relative to the market price. Only by locking gold away in vaults could they block a return to a more rigid system. Yet they also realized that locking away tons of gold indefinitely was not entirely realistic.Footnote 135 An agreement was eventually reached which eliminated official references to gold and significantly liberalized central bank transactions in gold for a transition period, after which policymakers would reassess the situation.Footnote 136 When the Second Amendment to the IMF Articles of Agreement came into effect on 1 April, 1978, gold finally ceased to play an official role in international monetary relations. Writing in 1982, Solomon predicted that “over time, gold is likely to seep out of official reserves and into the market, where it will become available to jewelers, dentists, artists, and industrial uses for whom substitutes for gold are less readily at hand than for monetary authorities.”Footnote 137 Gold no longer served as a standard of value or medium of exchange; it was only a store of value—like antiques, one might say—and this would handicap gold's role as international money.

Salomon's prediction ultimately failed, however. The gold standard was not restored, but neither did gold simply vanish from balance sheets. Most countries have held on to their gold since the Nixon shock—including the American government, whose gold stock of 8,000 tons today has barely budged since the 1970s. Gold has remained an element in the assemblage of international money, even though references to gold no longer serve as its pivotal practice. Policymakers had eased tensions in the assemblage by reassembling the relations among its parts, but were faced with wild exchange-rate fluctuations. They subsequently attempted to manage them through exchange rate cooperation, establishing regular economic summitry as a new pivotal practice.Footnote 138 Solomon saw the persistence of large gold reserves under these conditions as the result, inter alia, of a “distrust of government” and of gold's status as a “fail-safe” mechanism.Footnote 139 Salomon was of course correct that gold remained the great beneficiary of flights to safety in troubled times. Yet his analysis begs the question of why specifically gold has remained in this position. There are many other assets that could be used as safe-haven reserves, and yet only gold is seen as a safe asset worth hoarding by most central banks as well as market actors. Gold's presence on balance sheets thus manifests, among commodities and precious metals, a unique resilience—even though gold is no longer an official monetary reference.

Conclusion

To reinterpret changes in international monetary relations through a focus on gold provides important insights. The closing of the gold window has left the international monetary system, as George Schultz said, “at loose ends with itself.” We agree with this diagnosis, but we would add that, even before 1971, international monetary relations did not really take the form of a highly coherent “system.” International money is better understood as an assemblage, of which referring money to gold was for a long time a pivotal practice. Policymakers wrestled with tensions in the international monetary order, clinging to the known and only reluctantly leaping into the unknown. Their habitual attachment to gold persisted despite the shifts in power and economic ideas that IPE scholars have focused on. We are not denying that there is some usefulness to the distinction between the “embedded liberalism” of Bretton Woods and the turn to “market-friendly” policies after 1971. Yet a greater attention to assemblages and pivotal practices alerts us to continuities across historical periods. The waning of specie backing for money, which is often a mere footnote in conventional accounts of postwar IPE, may retrospectively appear as the truly historic monetary development of the twentieth century. There was nothing inevitable about gold. Yet gold constituted in part the possibility of action through its historical association with money and its implication in countless transactions and practices. Removed from the center of this assemblage but still endowed with many of the same qualities, gold now exists in an uneasy relationship with it. As much as some economists may prefer it, gold is unlikely in the foreseeable future to lose its status as a reserve asset and as a refuge from economic uncertainty.

More generally, international relations and IPE scholars should recognize that many assemblages populate international relations, as suggested by recent scholarship in cognate fields. There is an assemblage of international production, involving not only a political economy of trading states but also material elements such as natural resources and energy, machines, or transportation networks.Footnote 140 There is an assemblage of international peace and conflicts, which involves not only alliances and rivalries between states, but also changing military technologies and organizational forms and an ever-larger range of biological and physical phenomena.Footnote 141 There is an assemblage of international environmental degradation and protection, including not only conventions and treaties between states, but also planetary phenomena, capitalist exploitation, and scientific networks.Footnote 142 Each assemblage is, in turn, precariously maintained by actors who, in confronting an always-evolving reality, test, implement, and sometimes change the pivotal practices that support the assemblage.

Attention to assemblages, both in their social-psychological and material dimensions, is consistent with various strands of recent international relations scholarship that highlight the role of technology and the incremental evolution of institutions. If we accord too much importance to the study of power and ideational structures and consider assemblages as strictly exogenous to them, we miss an important dimension of what international relations are about. Politics does not only take the form of visible distributional or ideological conflict. There is also what Steven Lukes called a “third face” of powerFootnote 143—namely, that most people find it difficult, if not impossible, to imagine a world radically different from the one in which they live, which tends to make “objective” realities and everyday practices highly resilient. For instance, the reference to gold long framed policymakers’ slowly changing understanding of what money itself was. International relations and institutions should be analyzed not on the basis of some a priori defined characteristics but in terms of their emergent properties, as contemporary social theorists of institutions would advise.Footnote 144 In other words, it is time to investigate international assemblages, to embrace their ambiguity and loose coherence, and to focus on their pivotal practices.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this article may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/0VOR71>.

Acknowledgments

We thank Adam Kim for research assistance. For helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article, we thank Jane Bennett, Gerald Berk, Jacqueline Best, Jerry Cohen, Barry Eichengreen, Eric Helleiner, Victoria Paniagua, David Steinberg, participants in the 2018 American Political Science Association Annual Meeting, the editors of International Organization, and the anonymous reviewers.