The past several decades have seen a surge of interest in psychological approaches to the study of international politics.Footnote 1 Unlike structural realist or rationalist approaches, which largely study features of the environments in which actors are embedded, psychological theories of international politics turn to the properties of actors themselves.Footnote 2 A large volume of literature has thus emerged on the psychology of political elites: their operational codes, personality traits and leadership styles, and so on.Footnote 3 One of the central insights of this literature is that leaders are imbued with many of the same psychological mechanisms as ordinary citizens: they are prone to misperceptions, engage in motivated reasoning, and rely on heuristics and biases.Footnote 4

The presence of these biases in decision making is of particular importance. As Kahneman and Renshon note, in the context of foreign policy, nearly all of the cognitive biases uncovered by psychologists would lead political leaders to make more hawkish decisions, all else equal.Footnote 5 That is, these tendencies increase suspicion, hostility, and aggression toward potential adversaries, increasing the risk of political conflict and violence.Footnote 6 Individuals’ tendency to take risks to avoid a loss, for example, could encourage leaders to prolong wars beyond the point at which victory is achievable, engaging in risky offensives with little chance of success.Footnote 7 Likewise, leaders may become less willing to make concessions and more willing to risk large losses when bargaining.Footnote 8 The biased ways in which people assess the motives of adversaries could also increase the potential for conflict.Footnote 9 For instance, individuals tend to assess the intentionality of an act by its consequences, rather than by a thorough examination of the perpetrator's motives.Footnote 10 As a result, wartime actions that produce morally bad outcomes are more likely to be deemed intentional than identical actions that produce morally good outcomes.Footnote 11 Yet another cognitive bias that can prolong or worsen conflict is reactive devaluation, the tendency of individuals to immediately discount or devalue proposals coming from an adversary, compared to identical proposals offered by one's own side or a third-party mediator.Footnote 12

Yet for all of its rich insights, this literature has wrestled with a challenge. Most of what scholars know about psychological biases in decision making comes from the study of individuals, but many foreign policy decisions are made in group contexts. Indeed, groups are often used in foreign policy decision-making settings precisely because of their (presumed) ability to counter the decision-making pathologies or shortcomings of individuals acting in isolation.Footnote 13 Thus the theoretical and empirical value of insights from the behavioral sciences on the pathologies of individual decision making are often criticized in the study of foreign policy for a lack of clear understanding of how preferences, information, or traits aggregate into group-level decisions, with critics typically arguing that these psychological biases should be mitigated or otherwise cancel out in group settings.Footnote 14 Even proponents of psychological approaches have noted this limitation. In an important review of prospect theory, for example, Levy notes that “Most of what we want to explain in international politics involves the actions and interactions of states … each of which is, in principle, a collective decision-making body. The concepts of loss aversion, the reflection of risk orientations, and framing were developed for individual decision making and tested on individuals, not on groups, and we cannot automatically assume that these concepts and hypotheses apply equally well at the collective level.”Footnote 15 Writing two decades later, Hafner-Burton and colleagues express a similar concern, noting that institutional structures are often designed precisely to mitigate individual psychological biases.Footnote 16

Ultimately, however, the question of how psychological biases in foreign policy aggregate in groups—and whether groups indeed attenuate these biases—remains an empirical one, as theories of aggregation provide few guarantees. For example, Arrow's famous “impossibility theorem” shows that, even if all the individuals in a group are perfectly rational and calculating, many aggregation mechanisms can still produce irrational choices.Footnote 17 Meanwhile, other theorems show that aggregation can lead to more optimal decision making. However, such improvement often requires a set of fairly restrictive assumptions. For example, Condorcet's well-known jury theorem shows that sufficiently large groups can make better decisions if each individual votes independently and makes the right choice with probability greater than 50 percent. Yet, violating any of these assumptions may actually cause groups to make worse decisions than individuals.Footnote 18 This could be particularly concerning in many foreign policy decision-making contexts, where policy is often decided by small groups of individuals who influence one another and who may be systematically biased toward the wrong decision.Footnote 19

In this piece, we offer what we believe to be the first direct experimental test of the aggregation of psychological biases in foreign policy. We field three large-scale online experiments, where nearly 4,000 participants work through a series of foreign policy scenarios, which they completed either as individuals, or in one of two different types of group structures. We find that three prominent tendencies from the behavioral decision-making literature—risk taking to avoid a loss, the intentionality bias, and reactive devaluation—largely replicate in small-group contexts. We find no evidence that these tendencies are significantly reduced in group settings, and find that in some decision-making contexts they may even be exacerbated. Moreover, we find little evidence that more experienced leaders can improve group decision making or that more diverse groups are less prone to hawkish biases. These findings have important implications for how we understand the role of group processes in foreign policymaking, suggesting that groups are not a panacea for producing optimal policy decisions, and that we should not assume that the psychological tendencies that shape individual decision making do not appear in collective contexts as well.

Biases and Group Decision Making

The question of how group processes affect decision making is not a new one. Indeed, outside of international politics, there is a rich and diverse literature that has explored the ways in which group settings affect bias and judgment. In legal studies, for example, research on jury decision making explores how juror-level characteristics aggregate in shaping jury-level decisions.Footnote 20 In business administration, organizational behavior research focuses on how the traits of team members have varying effects on team performance depending on the types of tasks.Footnote 21 In social network analysis, scholars have experimentally studied the conditions under which collective decision making outperforms individual decision making.Footnote 22 Indeed, a small cottage industry has now formed that includes interdisciplinary approaches to “small group decision making,” which investigates, among other things, individual cognitive biases and under what conditions they might be overcome (or exacerbated) in a group setting. Even nonhuman animal models might offer relevant insights. A school of fish can follow light too weak for any individual fish to follow, for example.Footnote 23

While this diverse scholarship may offer crucial insights for the study of foreign policy, it has important limitations. Many invocations of the “aggregation problem” in political science are more philosophical than empirical, assuming ex ante that aggregation is a challenge rather than empirically testing the specific contexts in which psychological variables should or should not aggregate.Footnote 24 Because of the high cost of bringing large numbers of people into the lab, many of the canonical experimental tests of aggregation in group decision making have traditionally been somewhat underpowered, testing the impact of relatively small groups.Footnote 25 Thus it has been difficult to identify what aspects of group decision making causally affect outcomes. Perhaps most importantly, foreign policy decision making involves three theoretically relevant institutional structures and task properties that differentiate it from some of the main configurations frequently studied in the literature outside political science.

First, foreign policy decision making, particularly over security issues, often features ill-structured problems, where the probability distributions may be unknown.Footnote 26 Actors may not know, or may disagree on, the parameters of the decision-making task; they may even disagree on the ultimate goal with respect to the decision to be made. These situations stand in contrast to much, though not all, of the small-group research and analysis of aggregation that occur in other disciplines. Investigations of cognitive biases, for example, often use well-structured problems with clear probability distributions. Alternatively, studies that investigate the “wisdom of crowds” will often use difficult, but nevertheless clearly structured, math problems.Footnote 27 It therefore remains unclear how generalizable insights from clearly structured problems may be to decision making in the more amorphous context that characterizes much of international politics.

Second, foreign policy decision making often involves hierarchically structured groups, where the chain of command and the decision-making rules are known to all the actors involved. While the existing research on small group dynamics and decision making in groups takes many forms, including analysis of groups within large-scale hierarchical settings such as firms, much of the research political science has brought in has tended to focus on “flat” or horizontal groups, such as teams, and has not systematically compared the effects of hierarchical versus horizontal decision-making structures.Footnote 28 Hierarchies may emerge endogenously over time as a result of specific group members’ personalities, but this is theoretically very different from ingrained hierarchies built on formal and clear roles and decision-making rules.Footnote 29 It is partly because of the hierarchical nature of many foreign policy institutions that much of the foreign policy decision-making literature focuses on leaders, rather than advisers.Footnote 30 Moreover, without manipulating these structural conditions it is difficult to gain analytical leverage on how hierarchy affects foreign policy decision making.

Third, the substantive focus of scholars of foreign policy decision making, including distinctive outcomes of interest, are often very different from those studied in small-group research in other domains. Analysts of foreign policy are often interested in explaining specific dependent variables, such as a decision to use force. These are quite different from those often studied in small-group research, such as team morale or workplace satisfaction in a business context, or performance on mathematical exercises. It may be that the specific decisions of interest, such as the use of force, engage different aggregation processes, limiting the utility of extrapolating findings from small-group research to foreign policy.

Empirical research in political science has tended to focus on how groups might improve decision making, which brings in a normative component, and has returned a mixed bag of results: factors such as group size, composition, decision-making rules, political context, and leadership can all affect the quality of the decision-making process and outcome.Footnote 31 For example, groupthink, the most famous psychological dynamic documented in political group decision making, whereby group members’ striving for unanimity exacerbates decision-making pathologies, is hypothesized to be a contingent phenomenon, most likely to emerge under conditions of strong social-unit cohesion and external stress.Footnote 32

Driven by this finding, as well as subsequent research affirming the danger of group members’ striving for unanimity, many of the most prominent proposals for improving the quality of foreign policy decision making focus on constructing a diverse decision unit, led by an experienced leader who fosters healthy debate and dissent in the policymaking process.Footnote 33 These principles guide decision-making models such as multiple advocacy, the competitive advisory system, and distributed decision making.Footnote 34 Indeed, the perceived value of diversity as a tool to harness the mental power of groups and improve decision making is a hallmark of much recent scholarship.Footnote 35 However, diversity is not without risk, and may also increase intragroup conflict and decision paralysis.Footnote 36 Thus the benefits of diversity in improving decision making may depend on the presence of a leader who is well positioned to channel that diversity in productive directions. For example, research has suggested that a leader's experience, leadership style, predispositions, and personality can all shape their ability to harness the information-processing power of groups to improve decision making.Footnote 37 However, most research in political science on group decision making has relied on small-N case studies, which limits our ability to identify how different attributes of the group setting, such as the distribution of information individuals have or the experience they bring to the table, affect the quality of decision making.

In sum, while there are impressive cognate bodies of literature on aggregation outside of political science, and rich descriptive evidence on group dynamics in policymaking settings, we do not yet have strong experimental evidence regarding the effects of groups in the complex settings that characterize foreign policy decision making, nor do we fully understand how different decision rules, group composition, and leader attributes shape these processes.

In this study we test for the effects of group decision making on the prevalence of three well-known cognitive biases that have been observed in individual decision making: risk taking to avoid a loss, the intentionality bias, and reactive devaluation.Footnote 38 Each of these biases has been theorized to bias political elites in a “hawkish” direction.Footnote 39 In other words, all else equal, the presence of these biases may cause leaders to demonstrate a greater “propensity for suspicion, hostility, and aggression in the conduct of conflict, and for less cooperation and trust when the resolution of conflict is on the agenda” than is objectively warranted.Footnote 40

For example, loss aversion could reduce leaders’ willingness to compromise in negotiations. Their own concessions would be viewed as “losses,” while an adversary's concessions would be viewed as “gains”—and even when these concessions are equal, the gains would feel smaller than the losses, and so compromises would likely be rejected.Footnote 41 Similarly, the intentionality bias, whereby individuals assess whether an action was intentional based on its effects, may lead to misperceptions or unfounded certainty regarding intentionality. Actions with negative consequences, or “side effects,” are more likely to be seen as intentional. Such ascriptions are relevant in a range of contexts, from security dilemma escalation to public assessments of blame in civil conflicts.Footnote 42 Finally, reactive devaluation—a bias whereby a proposal is automatically perceived as less valuable if offered by an adversary—has been shown to affect attitudes toward negotiations in various political conflicts, from US–Soviet interactions during the Cold War to the ongoing Israeli–Palestinian conflict.Footnote 43 Together, then, these three biases have the potential to reduce the likelihood of negotiation success and trigger or prolong violent political conflict. Assessing the extent to which these individual-level biases scale to affect foreign policy decisions that are often made in group contexts is crucial for understanding how the institutional structures of foreign policymaking potentially mitigate or exacerbate the influence of these biases on international cooperation and conflict.

Research Design

The present study aims to examine the relative efficacy of groups in reducing the impact of these biases on decision making using three large-scale online group experiments conducted in Fall 2019 and Winter 2020, whose structure is summarized in Figure 1.Footnote 44 By manipulating the group setting, this study provides causal leverage to examine how the cognitive biases of individuals aggregate in different types of group decision-making units. As with all experiments, there are important questions about external validity to keep in mind, which we discuss in detail later.

FIGURE 1. Study design

The study proceeds as follows. After completing an individual-differences and demographic battery, respondents are randomly assigned to one of three group conditions. In the individual condition, 760 respondents are asked to make decisions on various foreign policy scenarios individually, taking notes as they think through their options. In the two group conditions, respondents are assigned to a group with four other survey takers, in which they participate in a group chatroom, discussing their options together before deciding on a course of action. There are two types of groups: horizontal groups, where participants are asked to try to come to a collective, unanimous decision and each participant has equal say in the process; and hierarchical groups, in which one of the five participants is randomly designated as the leader of the group, and gets to make the final choice, in consultation with the four other participants, who take on the role of adviser. In the analysis that follows, the group conditions consist of 3,213 respondents, forming 771 groups (406 horizontal, 365 hierarchical) of up to five members each. We paid an average of USD 10 per subject in respondent incentives, and all together, the effective sample size (N) of the study is 3,987.Footnote 45

After being assigned to one of these treatments, respondents pass through three separate experimental modules using canonical experimental setups to examine the prevalence of various biases in the context of foreign policy decision-making scenarios. Respondents in the individual condition complete these modules as individuals, writing down their justifications for their decisions and making decisions themselves, whereas respondents in the group conditions complete these modules as groups, deliberating as a group before reaching decisions.Footnote 46 An example of a group deliberation is shown in Figure 2. Respondents were generally engaged in the group deliberations; in the horizontal condition, 73 to 76 percent of group members in the analysis participated more than once in each deliberation, similar to the rate observed in the hierarchical condition (74 to 81 percent), with leaders participating more frequently than advisers—though as we show in section 4 of the online supplement, our findings are robust and do not significantly vary across different levels of group participation.

FIGURE 2. Sample group deliberation transcript

The first experimental module examines sensitivity to gain and loss frames on policy preferences—a canonical finding from prospect theory. Subjects are presented with a scenario in which “600 lives are at stake in a war-torn region.” Subjects are asked to choose one of two courses of action (Policy A or Policy B). Policy A will definitively lead to 200 people dying and 400 people being saved. Policy B has a probabilistic outcome, with a 1/3 probability that no one will die (all 600 will be saved) and a 2/3 probability that 600 people will die (none will be saved). The experimental treatment within this module is whether the results of each policy are presented in the domain of gains (e.g., “200 people will be saved”) versus the domain of loss (e.g., “400 people will die”). Half of the respondents in each experimental condition (individual, horizontal group, or hierarchical group) receive the “gains” treatment and half receive the “loss” treatment.Footnote 47

The second experimental module tests susceptibility to the intentionality bias—the degree to which assessments of intentionality are affected by the (negative) results of an event. In this module, respondents are asked to assess how likely it is that a US navy vessel sunk 100 miles off the coast of North Korea was intentionally versus accidentally targeted by the North Koreans. The randomly assigned treatment in this module is the number of casualties the sinking of this vessel has caused: none versus all 100 servicepeople on board. Half of the respondents in each experimental condition receive each treatment. This represents a more ill-structured problem than that posed by the previous experiment.

The final experimental module explores the prevalence of reactive devaluation of a trade negotiations proposal between the United States and China. Subjects view a short proposal that purports to resolve ongoing US–Chinese disputes over trade. The experimental treatment is the authorship of the text—whether the United States or China drafted the proposal. As with the first two modules, half the respondents in each experimental condition receive each treatment. Instrumentation for each of the three experiments is shown in section 1 of the online supplement.

We calculate our dependent variable differently in the three modules based on the group condition. In the individual conditions, we focus on the choice of each individual respondent. In the hierarchical conditions, we focus on the choice of each group leader. In the horizontal conditions, we primarily use a median voter rule to calculate each group's decision, but we also use two other aggregation rules (majority vote and unanimity) to test how sensitive our findings are to other means of aggregating group members’ votes. We describe these different aggregation methods in detail in section 2.1 of the online supplement.

Together, these studies are useful because they allow us to examine the extent to which hawkish biases replicate in individual settings and the degree to which group discussion—and the structure and composition of those groups—affect their prevalence, in experiments that differ from one another in a variety of ways. The existing literature lends us strong theoretical expectations in regard to the individual condition, given the canonical nature of these cognitive biases: we expect that individuals will be more risk seeking in the domain of losses than the domain of gains, will be more likely to assess an incident as intentional when its costs are higher, and will evaluate a proposal from an adversary more negatively than the same proposal from their own side.

Yet given both the novelty of our particular study and the contradictory arguments in the literature on the efficacy of groups in reducing biases, the ultimate effects of groups on these hawkish biases remains an open question. Groups could reduce the prevalence of hawkish biases, exacerbate them, or have no effect—particularly given that these hawkish biases may be deeply ingrained, or outside the realm of conscious awareness.Footnote 48 Empirically adjudicating between these competing expectations constitutes one of the central contributions of our study.

Analysis

To test these competing expectations, we turn to each of our three experiments in sequence. For each experiment, we first look within each group condition (individual, horizontal, hierarchical) to examine the prevalence of the hawkish bias tested (susceptibility to gains/loss framing, the intentionality bias, or reactive devaluation). We then compare these differences across groups to assess the extent to which these different decision-making structures affect susceptibility to each of the tested biases. Finally, we probe the robustness of our findings, assessing the degree to which various types of leader characteristics or aspects of group diversity affect susceptibility to biases and the ability to reach a decision in the first place.

Susceptibility to Gains/Loss Framing

We begin by examining the prevalence of a canonical hawkish bias across our three group formulations: the effects of loss-versus-gains framing on individuals’ acceptance or avoidance of risky choice.

In the individual condition, our results strongly replicate the core finding of prospect theory. When choices are framed as a potential loss (e.g., of life) individuals are significantly more likely to choose the probabilistic policy—that is, they are more accepting of the risk that all 600 lives will be lost, in order to preserve the possibility of an outcome where no one dies. In contrast, those presented with a gains framework, where people may be saved, are much more risk averse, preferring the nonprobabilistic Policy A (200 people will be saved).

Do groups reduce susceptibility to this bias? Our results suggest they do not; if anything, groups may increase the effect of frames on choice. In both types of groups, groups randomly presented with loss frames are significantly more likely to prefer the probabilistic outcome than groups that were presented with a gain frame (Figure 3). Examining the magnitude of these effect sizes across decision-making structures, we find that hierarchical groups in particular are significantly more sensitive than individuals to framing effects.Footnote 49

FIGURE 3. Prospect theory framing effects replicate in groups

Comparing the horizontal groups to individual decision makers, Figure 4 suggests that the susceptibility to gain/loss frames may depend on the specific decision rule used to assess these groups. For example, examining horizontal groups that succeeded in reaching a unanimous decision, we find similar results as in the hierarchical condition: the group setting increases susceptibility to these framing effects (p < .005). However, if we examine the full set of horizontal groups using a less stringent decision rule, such as a majority rule (p < .09) or median voter (p < .16), we do not find evidence that horizontal groups perform significantly differently than individuals. Either way, it is clear that horizontal groups do not reduce susceptibility to prospect theory's framing effects.

FIGURE 4. Prospect theory framing effects by horizontal aggregation method

Intentionality Bias

Next, we examine the relative prevalence of the intentionality bias across group settings. While the prospect theory module examines a fairly well-defined decision problem where each policy choice features known probability outcomes, the intentionality bias module examines a more complex choice: how likely do you think it is that an event was caused by a purposeful attack by an adversary? In the individual condition, our results again strongly replicate the canonical intentionality bias finding. When the consequences of an event are more negative (in this case causing fatalities), individuals are significantly more likely to assess the event as an intentional provocation rather than the result of an accident or miscommunication. Group settings do little to attenuate this tendency: both horizontal and hierarchical groups are significantly more likely to assess the sinking of a US navy ship as the consequence of an intentional attack by the North Koreans when there are fatalities reported (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. Intentionality bias replicates in groups

However, unlike the prospect theory experiment, with the intentionality bias, we find that groups have no effect on the severity of this tendency. While certain group configurations tended to make our respondents somewhat more susceptible to framing effects, in this case groups perform similarly to individuals—no better or worse.Footnote 50

As before, horizontal groups that reach a unanimous decision do display a somewhat more pronounced bias than those assessed with less stringent decision rules (majority rule or median voter), but this difference is not statistically significant (Figure 6). Regardless of the aggregation method, both horizontal and hierarchical groups increase their assessments of intentionality in response to negative outcomes to a similar extent as individuals do.

FIGURE 6. Intentionality bias effects by horizontal aggregation method

Reactive Devaluation

Finally, we turn to reactive devaluation. Here we unexpectedly do not replicate the standard reactive devaluation result in two of the three decision-making conditions (Figure 7). Individuals are not significantly less likely to support a proposal authored by China than one authored by the United States. Hierarchical groups, where the decision is ultimately made by a single individual after group discussion, also do not prefer US-authored proposals.

FIGURE 7. Reactive devaluation experiment displays mixed results

On the one hand, this finding is surprising: the theoretical expectation is that proposals written by an adversary (e.g., China) will be automatically devalued with respect to proposals written by one's own side (the United States). However, work on reactive devaluation also suggests that there are two distinct mechanisms by which proposals are devalued: reactance processes that lead individuals to devalue that which is available compared to what is not, and reliance on source credibility as a heuristic for value.Footnote 51 Our treatment aims to test this second mechanism: American respondents might devalue a Chinese-authored proposal relative to an American-authored one because they would assume that the other country's negotiators do not have America's best interests in mind.

However, to the extent that source credibility drives reactive devaluation, reactive devaluation should be strongest when individuals are presented with ambiguous proposals that increase their reliance on source heuristics.Footnote 52 When the proposal is detailed and specific, subjects may be less likely to automatically devalue it because the proposal itself provides enough information to make an assessment. In our study, the proposal was quite specific and detailed, with bullet points outlining the exact compromises each side would make in the ongoing trade war. This level of detail may have attenuated reactive devaluation, making it easier for subjects to look past the purported authorship of the proposal to evaluate the actual proposal content.

Another possibility is that the conflict tested in this study—contested trade negotiations in the shadow of Trump-era trade wars—resulted in less reactive devaluation either because of the unusual domestic politics of the Trump era, or simply because the rivalry was less clear-cut than the violent, intractable conflicts in which this bias has historically been studied. In other words, Israelis may be more suspicious and distrusting of Palestinians, and Americans more distrusting of the Soviet Union or North Vietnam during the Cold War, than Americans in 2020 were of China, with whom the United States had a less directly confrontational relationship.Footnote 53

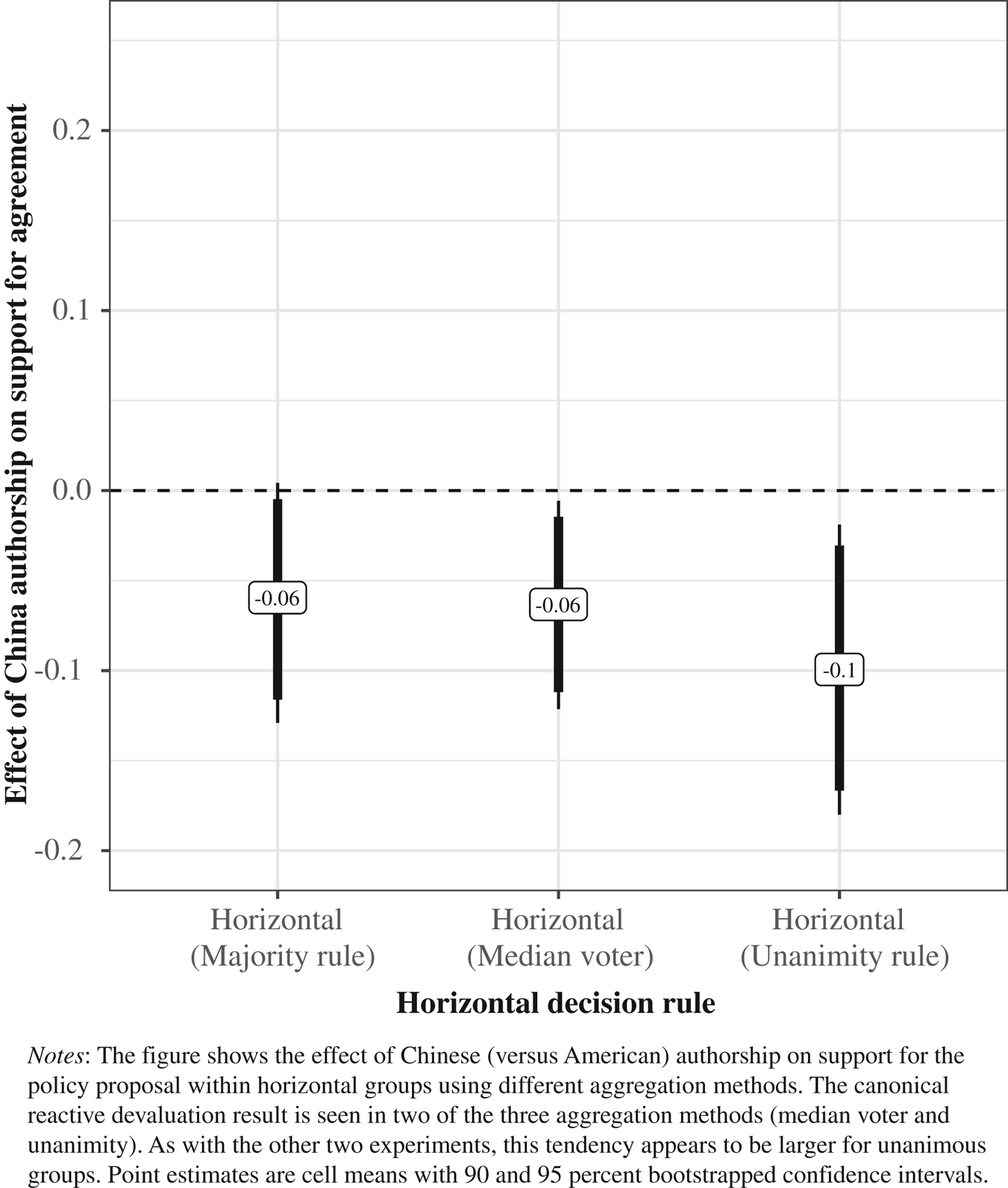

However, even with the specificity of this proposal and ambiguity in the rivalry, we do observe reactive devaluation in horizontal groups, particularly those that reached unanimous decisions (Figure 8). Unanimous horizontal groups are marginally more likely than individuals (p < .06) to devalue the Chinese proposal relative to the American one. This suggests that, to the extent that the potential for reactive devaluation occurs in this context, groups are, if anything, increasing this tendency.

FIGURE 8. Reactive devaluation effects by horizontal aggregation method

Extensions and Limitations

Thus far, our results suggest that two canonical biases from the judgment and decision-making literature—sensitivity to framing effects in prospect theory, and the intentionality bias—persist or become even more pronounced in group settings. And, while we fail to replicate reactive devaluation in our individual condition and hierarchical group contexts, we replicate it in horizontal groups, which is inconsistent with the claim that the hawkish biases that manifest in individual settings disappear in groups. However, there are important limitations and caveats worth discussing, many of which involve questions of external validity, and differences between inevitably stylized experiments and real-world foreign policy decision making.

First, our experiments lack many of the social dynamics of real foreign policy decision-making groups where there is social pressure, people have worked with each other before (and might again), issue linkage is possible, bureaucratic interests are present, and so on.Footnote 54 In contrast, our respondents participate anonymously, in novel groups formed explicitly for this study, with little social pressure for cohesion or prospect of future interaction.Footnote 55 We encourage future researchers to build on these studies by incorporating some of these features into their experimental designs to determine the impact of differing levels of social pressure on group susceptibility to bias. And yet the absence of these features likely makes our findings a more conservative test of groups’ ability to reduce bias, since the features missing from our studies are also the very features typically linked to biased information-processing and pathological group dynamics such as groupthink.Footnote 56 In that sense, the fact that we replicate the prospect theory and intentionality bias effects across all our group conditions even without the distorting effects of social conformity pressures should increase our confidence in the pervasiveness of these tendencies.

Second, in the real world, leaders are not randomly assigned but strategically selected for particular skills, attributes, or experience. On the one hand, this is precisely why experiments are helpful: in a naturalistic setting, it would be difficult to identify the effect of group structures independently of the properties of actors in specific roles in the group. Experiments, in contrast, let us harness the power of random assignment and sidestep these concerns about endogeneity. On the other hand, this also leads to an important empirical question: are groups with certain types of leaders better able to avoid these biases?

To test this question, we take advantage of the lengthy battery of individual differences administered to respondents at the beginning of the study. Since there are many potential traits that could moderate the impacts of framing effects, intentionality bias, and reactive devaluation, we adopt a data-driven approach, estimating a sparse Bayesian method for variable selection. We fit a LASSOplus model regressing our dependent variable on the treatment, a vector of twenty-one individual differences (foreign policy orientations, personality traits, demographic characteristics, government experience, and so on), and interactions between these leader-level traits and the treatment using data from the hierarchical condition.Footnote 57 This machine-learning approach thus lets us test whether certain kinds of leaders (such as those high in need for cognition, or with more experience) better help their groups avoid these biases. Crucially, none of these leader-level characteristics significantly moderate the treatments. We thus find no evidence that groups with better leaders are less likely to display these patterns. We encourage future work to build on these findings by assigning respondents with specific traits (such as narcissism) to leader and adviser roles, to test how it affects the quality of decision making.Footnote 58

The question of leader traits raises a related issue. Our study was conducted on samples of ordinary citizens, rather than experienced decision makers. It is of course possible that groups composed of actual elite decision makers would behave differently, though two considerations are relevant here. One is that these three hawkish biases have previously all been identified in foreign policy elites using archival and case study evidence,Footnote 59 so we already have reason to believe that foreign policy decision makers experience hawkish biases; the question is whether group contexts moderate the magnitude of these biases at a significantly different rate among elites than they do among members of the mass public. The other is that meta-analyses of paired experiments on elite and mass samples suggest strikingly similar responses to experimental treatments, so we should not assume that they rely on fundamentally different cognitive architectures.Footnote 60 Ultimately, however, this is an empirical question. It is also one that elite experiments may be poorly equipped to answer, suggesting benefits for archival or mixed-method approaches. Experimental or survey-based studies on real foreign policy decision makers invariably involve smaller sample sizes—effectively made smaller still once analyzed at the group level—such that many group-level elite experiments would likely be underpowered, particularly if they use the sample of elites most directly implicated by their theory.Footnote 61

Group-Level Diversity

Yet even if leader-level traits don't seem to minimize these three biases, it is possible that group-level ones do. One of the most-studied attributes of groups hypothesized to improve decision making is diversity.Footnote 62 Diversity refers most broadly to “compositional differences among people” within a particular unit, such as a decision-making group.Footnote 63 In a decision-making context, these compositional differences are often understood as representing the interaction of different cognitive styles. As Page has argued, in the context of problem solving for example, diversity of perspectives, interpretations, heuristics, and individual predictive models that are used to infer cause and effect all come together to “increase the number of solutions that a collection of people can find by creating different connections among the possible solutions.”Footnote 64 Diverse groups are also thought to lead to more extensive debate, increase exposure to others’ viewpoints, introduce differences in risk preferences, and avoid group pathologies such as groupthink, where striving for uniformity may overwhelm accuracy motives.Footnote 65 In short, “diversity trumps homogeneity.”Footnote 66 Yet, groups that are too diverse may move too far in the other direction, to where a “polythink” dynamic prevents them from reaching consensus at all.Footnote 67 Relatedly, in some instances diverse groups may be more prone to conflict, as social identity and categorization processes may impede the value of information and perspective pooling that leads to higher group performance.Footnote 68

We therefore examine the potential mitigating effect of diversity on susceptibility to bias, assessing whether groups with a more diverse composition are affected less by these various hawkish biases. Rather than using Herfindahl indices, which flatten diversity onto a single dimension, we operationalize diversity in a multidimensional fashion, calculating the group-level variance of a given trait in each group, and averaging across diversity scores for four types of traits, to produce measures of four different types of diversity.

We first examine diversity from a demographic perspective, in which more diverse groups are those with members with different ages, gender and racial identities, religions, and socioeconomic backgrounds. This type of descriptive diversity, in addition to being normatively valuable, has been hypothesized to improve decision making by broadening the information set and policy options reviewed and considered by a group.Footnote 69 Second, we operationalize diversity in terms of personal dispositions: the “big five” personality characteristics, need for cognition, trait aggression, and risk orientation. This type of cognitive diversity is often studied in the organizational behavior literature, which is interested in how the variability of personality characteristics in teams affects their collective performance.Footnote 70 Third, we turn to diversity of experience within groups, where different members of the group have varying levels of experience in leadership and small-group decision making (political or otherwise). In foreign policy decision-making contexts, diversity of experience may be particularly important, since decision units are typically a mixture of experienced bureaucrats and shorter-term political figures, themselves with varying experience in government.Footnote 71 Finally, we consider groups whose members vary in their political attitudes or orientations, including political ideology, right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, and foreign policy orientations. These types of attributes have long been theorized to play a prominent role in foreign policy beliefs and attitudes, but how the variance of these traits within a decision-making unit affects decision outcomes has been less explored.Footnote 72

Regardless of how we operationalize diversity, however, we find no systematic effects of diversity on susceptibility to any of the hawkish biases we examine. Diverse groups are just as likely as more homogeneous groups, and no less likely than individuals, to exhibit these biases (Figure 9).Footnote 73 It is not that diversity has no effects whatsoever: more diverse groups, particularly those with more diverse dispositions and political attitudes, are more likely to fail to reach agreement at all (Figure 10). This is particularly the case in the intentionality bias and reactive devaluation experiments, where respondents are assessing adversarial interactions with China and North Korea. Groups whose members hold different social and political attitudes are more likely to show internal dissensus and disagreement.Footnote 74 Nonetheless, more diverse groups do not appear to be less likely to display these three tendencies.

FIGURE 9. More diverse groups are no less susceptible to these three biases

FIGURE 10. More diverse groups are more likely to experience dissension

Group Size and Modes of Interaction

Finally, there are two other considerations worth noting, which also serve as alternative interpretations of our results. One is that for the ameliorative effects of aggregation to take place, group members need to interact face to face rather than deliberate at a distance.Footnote 75 Another is that for the ameliorative effects of aggregation to take place, groups need to be much larger; after all, foreign ministries have hundreds or thousands of individuals. While small groups might replicate individual-level biases, the “wisdom of crowds” might suggest greater rationality as groups grow in size.Footnote 76 On the one hand, these interpretations are obviously in tension with one another, since as groups increase in size, the rate of face-to-face communication decreases. On the other, there are a number of empirical tests we can employ to speak to some of these questions directly.

First, we can exploit variation in group size in our results. The magnitude of the hawkish biases we observe does not significantly shrink with group size (see Section 3 in the online supplement), and simulation methods suggest that some might actually increase.

This pattern comports with archival evidence from the United States regarding leaders’ frustrations with the pathologies of large decision-making units and the perception that larger groups had more problematic tendencies than smaller ones. As a result, while there was variation from administration to administration, a number of high-profile decisions, from the Cuban Missile Crisis to the first Gulf War, often involve the president and a relatively small number of influential advisers.Footnote 77 John F. Kennedy, for example, was disappointed by the results of relying on a large number of advisers, noting, “The advice of every member of the Executive Branch brought in to advise was unanimous—and the advice was wrong.” In response, at least partially, to these perceived failings of larger groups, Kennedy created a smaller Executive Committee, and often relied on ad hoc meetings of even smaller groups within it. Similarly, George H.W. Bush relied on ad hoc small groups of advisers when deciding whether to invade Iraq. The results from this study are likely directly applicable to these types of cases of relatively small group decision making, which have been quite common in historical US foreign policymaking.

Second, although all our respondents participated online rather than in person, if we think about face-to-face interaction in terms of the added information it conveys, we can test this informational mechanism directly by testing whether groups where respondents exchanged more information as part of their deliberations displayed weaker biases than groups where respondents communicated less.Footnote 78 Interestingly, across all three experiments, for both horizontal and hierarchical groups, we find no evidence that the magnitude of the biases groups display significantly decreases with group participation (see section 4 in the online supplement).Footnote 79

One explanation may relate to behavioral modifications that are made when more information-rich environments, such as face-to-face meetings, are unavailable. When unable to communicate with visual expressive behaviors, individuals use textual proxies for visual cues, which in some cases may enhance, rather than degrade, social bonding processes.Footnote 80 Research in social information processing theory suggests that when individuals meet for the first time, as is the case in our study, text-based communication can enhance intimacy and self-disclosure, positively affecting relationship building.Footnote 81 For example, Wheeler and Holmes argue that face-to-face interaction as a quotidian practice of international politics is a relatively recent phenomenon, which means that text-based communication was, historically, the only route to relationship building.Footnote 82 Particularly as global pandemics take diplomacy online, we see questions about the role of interaction modality in group decision-making as an important topic for future research.

Conclusion

In a recent review of the problem of aggregation, Gildea notes that “how psychological mechanisms, which are primarily individually embodied, may operate and exercise influence within complex group and institutional environments remains a crucial and contested question.”Footnote 83 To date, such concerns have remained largely conceptual in nature, and the answer to this question has proven elusive because studying it empirically introduces a number of difficult methodological and substantive challenges. We offer a direct test of how a particular class of psychological biases aggregate in foreign policy contexts by experimentally testing how a trio of so-called “hawkish biases” linked to foreign policy aggregate in groups. Our results, which suggest that the aggregation problem may be less problematic than some scholars have alleged, and that individual-level psychological biases do not necessarily cancel out in groups, may be surprising for some. If “the whole point of government is to ensure multiple voices and checks and balances so that rational decisions can, in theory, persist despite individual preferences and biases,” we may need to revisit the assumption that multiple voices lead to more rational outcomes.Footnote 84 Our results suggest that the biases that manifest in lone voices are similarly present in group decision making.

One important theoretical implication of our findings is that we should be more comfortable envisioning individual-level biases scaling up to small groups in decision-making contexts. In an important application of prospect theory to foreign policy, McDermott applied the bias to a number of cases, focusing “on a unitary actor embodied by the president.” She notes that “prospect theory is less easily applied to the dynamics of group decision making, except to the extent that all members are assumed to share similar biases in risk propensity, although each may possess a different understanding of such crucial features as appropriate frame for discussion, applicable reference point, domain of action, and so on.”Footnote 85 By analyzing prospect theory's applicability to groups experimentally, we are able to control many of these elements, including the domain of action and parameters for discussion, and our results suggest that such an application of individual psychology to groups may therefore not be as infeasible as some may fear. Further empirical work is required to assess how the experimental results we obtain here generalize to those in historical cases, while additional experimental work will likely be helpful in establishing how the group decision-making process operates. One such question concerns the study of reference point in groups. As Kameda and Davis ask, “What happens if a group is composed of some members who have experienced certain losses recently and others who have experienced certain gains recently?”Footnote 86 Randomly assigning group members with treatments that condition their individual reference points may allow researchers to trace the effects of those reference points in the group decision-making process.

An additional potential implication concerns our failure to detect beneficial effects of diversity on group decision making. One reason for this may relate to the nature of the tasks we employ here: unlike the protocols used in many of the experimental tests in the wisdom-of-the-crowd literature, testing the “miracle of aggregation” using math problems or prediction tasks, none of these studies have an objective right answer. In this sense, though, they better resemble the ill-structured problems that characterize much of foreign policy decision making, suggesting that the wisdom of the crowd may be a poor analogy for many of the questions IR scholars care about—although we also examine this question directly in follow-up work, using incentivized group bargaining experiments.Footnote 87 Future research should also focus on identifying other possible diversity mechanisms, such as those that relate to visible diversity and face-to-face interactions.Footnote 88 In face-to-face contexts, group members will likely be more aware of diversity within their group, creating a possibility that group members’ knowledge of their group's diversity affects their problem solving.

Another interpretation may have to do with the robustness of the biases themselves. Perhaps the three cognitive biases examined in this study are particularly ubiquitous and resistant to attempts at mitigation. We have some empirical evidence on this front: we use the same LASSOplus approach we used in the leader characteristic analysis, but testing for heterogeneous treatment effects by individual-level traits in the individual condition. As before, none of these individual differences significantly moderate the treatments. Thus, one potential reason why we fail to find that diversity has mitigating effects has to do with the robustness of the regularities we study here. In other words, diversity may be beneficial in improving decision making in other crucial ways, even if it does not appreciably alter a group's susceptibility to these types of cognitive biases.Footnote 89 Yet the fact that these “nonstandard preferences” appear to be so robust also suggests the merits of rational choice approaches incorporating these regularities into their models.Footnote 90 In other experimental work, we build on these findings by examining how individual-specific traits relevant to foreign policy decision making—rather than these judgment and decision-making biases that appear to be fairly robust across individuals—aggregate in group decision-making contexts.

This is not to say that groups do not exhibit their own peculiarities that may lead to subrational or irrational outcomes. It may be, for example, that not only do groups not reduce the effects of cognitive biases, they introduce new dynamics that may exacerbate deviations from expected utility models. Early psychological research identified many of these tendencies. “Risky shifts,” or the tendency of individuals in groups to make riskier decisions than when polled individually, is a finding that led to a robust literature on group polarization, consistent with the findings of our prospect theory experiment.Footnote 91 Similarly, initial studies on group conformity spurred over half a century of investigating the conditions in which groups create conformity dynamics in foreign policy situations, particularly as they relate to perceived policy failures.Footnote 92 It may be, however, that groupthink is receiving unfair blame. As Whyte has argued, “history and the daily newspaper provide examples of policy decisions made by groups that resulted in fiascoes. The making of such decisions is frequently attributed to the groupthink phenomenon”—though it may be that “prospect polarization” instead is the culprit.Footnote 93 Precisely because cognitive biases have largely been studied at the individual level, and not believed to be a group-level phenomenon, group-level theories such as groupthink have taken on a heavy explanatory burden. By relaxing the assumption that we need group-level theories to explain “nonstandard decision making,” new explanatory frameworks become available. It is also conceivable that the persistence of cognitive biases in groups exacerbates conformity dynamics by facilitating premature consensus, a possibility worthy of future research.

Finally, while our focus here is on the aggregation of biases that IR scholars have argued are particularly important in foreign policy decision making, it is worth noting that our findings are relevant for the study of collective decision making in a wide range of contexts. Prospect theory is frequently applied to a variety of questions in American and comparative politics; intentionality bias is central to questions of blame attribution in politics more generally; and reactive devaluation is tightly linked to theories of negative partisanship.Footnote 94 These findings should therefore be of interest to scholars of collective decision making across a broad set of domestic political issues, rather than just foreign ones.

In treating aggregation as an empirical rather than conceptual question, our study also has important implications beyond the three biases studied here. While we focused on studying group decision making in the context of foreign policy, similar group processes are present in a wide range of complex institutional environments. Practice theorists, for example, have argued that diplomacy in an organization such as NATO includes micro dyadic interactions between individual diplomats, as well as collective decision making in which diplomats conform with logics of practice or habit.Footnote 95 During NATO decision-making sessions on the proposed use of force in Libya in 2011, for example, Adler-Nissen and Pouliot report that diplomats drew on the taken-for-granted nature of the decision making, noting that “at some point you just know where the wind blows,” and that in these discussions, “the diplomatic process gradually gains a life of its own.”Footnote 96 One of the criticisms levied at this type of approach, however, is that the mechanism by which a group comes to know which way the wind is blowing, or how diplomacy gains a life of its own, is often underspecified, making it difficult to know a priori when and what types of practices are likely to affect outcomes in any given setting.Footnote 97 Our methodological approach offers one step toward a potential solution. By studying aggregation empirically, group experiments such as those reported here may help us better identify the ways in which group practical sense is created, providing an incremental step in building microfoundations for practice theories. Altogether, this research shows the value of treating the “aggregation problem” in foreign policy as a phenomenon that deserves to be studied empirically, rather than just assumed.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this article may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/N8GBLF>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818322000017>.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Henry Atkins, Riley Carney, Brad DeWees, Emily Jackson, Austin Jordan, Max Kuhelj Bugaric, Daiana Lilo, Ethan Mallove, MD Mangini, Andras Molnar, Clay Oxford, Eric Parajon, Yon Soo Park, Heather Rodenberg, Andi Zhou, and the students in GOVT 204 and the Political Psychology and International Relations research lab at William and Mary for research and programming assistance. We're also grateful to Jack Levy, John Paschkewitz, Katy Powers, Ryan Powers, Ken Schultz, Lisa Troyer, Alan van Beek, Jessica Weeks, and audiences at ISPP, APSA, Washington University in St. Louis, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Georgia for feedback, as well as to Rose McDermott for enormously helpful conversations at the WCFIA security cluster conference in 2018, and to Keri Lemasters, Brooke Moore, Sarah Pollack, and Amy Stockton for making the study possible.

Funding

This research was funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (award no. W911NF1920162). We acknowledge the support of the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs and the Institute for Quantitative Social Science at Harvard University.