Is conquest obsolete? How rare has territorial conquest become? Because conquest recurred as a central element of warfare for most of human history, those questions raise another: have the causes of war changed? Past studies reach a remarkable degree of consensus about the history of conquest since 1945. These studies report that conquests of entire states virtually ceased after the Second World War. Conquests of parts of states declined sharply after 1945 before nearly ending altogether after 1975. Consequently, territorial wars became rare after 1975, marking a historic change in the causes of interstate war. A strengthening territorial integrity norm is thought to be the principal reason for these declines of conquest and war. The international community now more frequently intervenes to uphold that norm. Thanks to those interventions, the few attempts at conquest that still occur rarely succeed.Footnote 1

This consensus history of conquest's decline seems at odds with the array of territorial conflicts confronting the world today. Russia's 2014 invasion of the Crimean Peninsula demonstrated that the world has not seen the last of conquest, not even in Europe. Alarmed by events in Ukraine, NATO began to increase its presence in the Baltic to deter a similar operation in, for instance, the Estonian border town of Narva.Footnote 2 In Asia, the possibility of a Chinese seizure of islands in the Senkakus (from Japan) or the Spratlys (from Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, or Taiwan) ranks among the most likely future crisis scenarios. The prospect of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan constitutes one of the most worrisome pathways to major war in the twenty-first century. China's border with India remains contested. Potential territorial wars seem to span the globe, including festering disputes between India and Pakistan, Armenia and Azerbaijan, Sudan and South Sudan, and more. Are these fears misplaced?

New and more comprehensive data on territorial conquest make it possible to re-examine this gap between scholarly research documenting the decline of conquest and popular perceptions of conquest's enduring threat. The Modern Conquest data set consists of 151 conquest attempts from 1918 to 2018.Footnote 3 Drawing on these data, in this study I lay out a revised history of territorial conquest after 1945 to come to a new understanding of conquest in the world today. This revised history diverges from the academic consensus to a surprising extent. Despite the existence of six major empirical studies using three data sets to document the decline of conquest, only the first of the six principal findings summarized in the opening paragraph finds clear support in the new data. Modern conquest differs markedly from conquest before 1945 in size, location, and strategy, but conquests have proven far more persistent than past studies recognized. More than it declined, conquest evolved.

In earlier eras, conquest and warfare seemed naturally to go hand in hand. The sequence of events often went: initiate war, then try to take territory. Today, the predominant sequence has become: seize a small piece of territory, then try to avoid war. The fait accompli has become the primary strategy of conquest.Footnote 4 This change in the relationship between conquest and war happened as a gradual evolution that began in 1945. Attempts to conquer entire states—the most war-prone form of conquest—declined immediately after 1945. Past studies ably document this.Footnote 5 However, Modern Conquest data reveal the lack of a corresponding decline in “war-averse” conquests. These are conquests of territories with characteristics that reduce the risk of provoking war. Attempts to conquer territories far smaller than entire states—generally one province or less in size—remained common after 1945. By the 1980s, conquest attempts targeting small territories with attributes that heighten the probability of war—populated territories and garrisoned territories—became rarer. By the 1990s, attempts to conquer unpopulated territories came to outnumber those taking populated regions for the first time in modern history. Similarly, seizing undefended areas now occurs more often than seizing areas that require confronting a military garrison.

Past studies have inferred a constraint against conquest—the territorial integrity norm—and applied it to explain the decline of war. Yet why, then, have territorial revisions with less risk of provoking war persisted? Rather than the decline of conquest causing the decline of war, the evidence better supports a reversal of the causal arrow: the decline of war caused the decline of war-prone forms of conquest. Nonetheless, although states attempting conquest now generally limit their ambitions to reduce the likelihood of provoking war, that risk is not zero. Argentina did not expect its 1982 seizure of the Falkland Islands to cause war, nor Pakistan its 1999 encroachments in the Kargil region of Kashmir.Footnote 6 Because some would-be conquerors miscalculate what they can get away with taking, territorial wars have retained their status as the predominant type of interstate warfare. Indeed, this chain of events—a miscalculated attempt to get away with seizing a small disputed territory that unexpectedly provokes escalation—accounts for a considerable proportion of interstate warfare since 1945.

These revisions to the history of conquest matter for several reasons. First, if conquest has become as rare as past studies suggest, then research on territorial conflict would be of historical more than current interest. By documenting the persistence of both conquest and territorial war, I make the case for the continued importance of territorial conflict. Second, scholars working on any aspect of territorial conflict can use the description of modern conquest developed in this study as a basis for assessing whether and how their findings apply to conquest today versus, for instance, pertaining to conquest only before 1945. Third, by describing the strategy and characteristics of modern conquest, the study sheds light on how states might manage future territorial conflicts that threaten to erupt into wars. Finally, by challenging the evidence suggesting that the territorial integrity norm curbed conquest and war, the study contributes to better understanding the causes of war in the modern era.

Of course, no single article can provide a comprehensive history of conquest. Most importantly, I do not attempt to assess all possible motives for conquest; that is, why so many states desire even small pieces of territory enough to risk seizing them.Footnote 7 Instead, I focus on the question of whether some constraint—such as a territorial integrity norm or an alternative constraint against war initiation—has shaped conquest's evolution. Consequently, I engage only briefly with the processes of decolonization and secession that intersect so clearly with some of the motives for revising inherited borders after 1945. Nor do I address the distinctive features of conquest before 1918, an era of imperialism and colonization.

I begin by reviewing the existing scholarly consensus that a territorial integrity norm caused the decline of territorial conquest after World War II. Second, I develop an argument about how conquest evolved as states increasingly came to take territory while trying to avoid wars rather than trying to win wars. Third, I chart the surprisingly partial nature of conquest's decline after 1945. Fourth, I show that territorial war persisted even after conquest in effect ceased to occur according to existing conquest data sets. Fifth, I cast doubt on the evidence that states more frequently intervene to reverse conquests or that these interventions have reduced the success rate of conquest attempts. Sixth, I provide an empirical basis for deeming the fait accompli as the predominant strategy of modern conquest. Seventh, I identify characteristics of seized territories that reduce the risk of provoking war and use them to document the declining war proneness of conquest attempts. Finally, I conclude by explaining why small territorial seizures are likely to be a defining element of the twenty-first-century international security landscape.

The Territorial Integrity Norm

Extensive evidence suggests that a territorial integrity norm greatly diminished conquest after the end of the Second World War. Conquests of entire states virtually ceased.Footnote 8 Only four times since 1945 has a state attempted to conquer and absorb another. North Korea unsuccessfully sought to conquer South Korea in 1950.Footnote 9 North Vietnam successfully conquered South Vietnam in 1975. Indonesia invaded and annexed Timor-Leste in 1975, nine days after it declared independence from Portugal.Footnote 10 Timor-Leste regained its independence in 2002. Iraq occupied Kuwait in 1990 before losing the Gulf War.

Broadening the lens to include conquests of all sizes, past studies again describe dramatic decline after 1945 and a further steep decline from 1975.Footnote 11 Goertz, Diehl, and Balas conclude that “conquests and annexations are significantly less frequent after 1945 than in previous eras to the point that they are virtually nonexistent in the last forty years.”Footnote 12 Pinker affirms, “Zero is also the number of times that any country has conquered even parts of some other country since 1975.”Footnote 13 If so, one purpose of this study—describing conquest in the world today—would be fruitless. There would be little to describe.

These conclusions provide a basis for optimism about the improbability of conquest and territorial war in the future. The centrality of territorial conflict to the causes of interstate war has been well documented.Footnote 14 If conquest has largely subsided, presumably it can no longer function as an integral step toward the onset of most interstate wars. Is territorial conflict no longer the pressing issue for international relations that it has been for time immemorial? The consensus history of conquest would seem to imply just that.

One idea dominates among existing explanations for the decline of territorial conquest: a norm of territorial integrity grew stronger after 1945, suppressing conquest.Footnote 15 Fazal characterizes it more narrowly as a norm against conquest. Atzili's concept of a norm of border fixity approaches it more broadly as a general constraint against changes to existing borders. These conceptualizations diverge on two points: whether or not the norm proscribes secession and whether or not it discourages peaceful border change. This study sets both questions aside and focuses on behavior that all prior studies agree falls within the norm's purview: conquest after 1945. Akin to Fazal, this study defines the territorial integrity norm as a widespread social understanding that it is impermissible to deploy a military force to seize territory from another state without that state's consent in furtherance of a claim to sovereignty over the territory.Footnote 16

The final two decline-of-conquest studies make arguments that stray from this consensus. Pinker uses the decline of conquest as evidence for the shrinking role of violence in human civilization rooted in long-term processes of social progress.Footnote 17 Hathaway and Shapiro apply it as evidence for international law's efficacy at constraining war.Footnote 18 Both studies eschew drawing a sharp distinction between their arguments and the territorial integrity norm, which I critique in later discussion.

Although these studies agree that the norm suppressed conquest, they conceive of conquest in subtly different ways.Footnote 19 Conquest can be understood as either a behavior or an outcome. That is, does a state need to merely seize disputed territory to have conquered it? Or must that state retain control afterward for an extended length of time? That choice matters because it gives rise to the question: must all conquest behavior decline for the territorial integrity norm to be vindicated, or merely conquests as lasting outcomes? Consider the Persian Gulf War. Does Iraq's attempt to conquer Kuwait weigh against the norm because it occurred? Or does it demonstrate the norm's strength because the international community intervened to oppose conquest by liberating Kuwait?

To avoid confusion about this, I use the term conquest attempt in lieu of conquest for precision of meaning. Conquest attempts correspond to conquests conceived as behaviors. Successful conquest attempts comprise conquests conceived as outcomes. Unsuccessful conquest attempts are cases where states seize territory but fail to hold it, usually losing control after battlefield defeats. It is sometimes useful to think of unsuccessful conquest attempts as short-lived conquests because the difference is a question of duration.Footnote 20

Evaluating the territorial integrity norm must start from a clear understanding of what it predicts about the history of conquest after 1945. After all, a few violations of a norm cannot invalidate its existence.Footnote 21 The simplest and most sweeping understanding of the norm's effects would expect that it prevented most conquest attempts and therefore led to something approaching the demise of conquest. However, although the frequency of violations (the number of conquest attempts) is one important dimension of norm strength, norm scholars argue that violations eliciting broad condemnation and punishment can reveal a norm's strength more than its weakness.Footnote 22 On that basis, the norm might instead be expected to have produced a different pattern of conquest behavior: conquest attempts continue to occur regularly—albeit less frequently than before 1945—but the international community frequently intervenes to ensure that these attempts fail. According to Goertz, Diehl, and Balas, “even in the few instances in which states have recently violated the norm against conquest, the international community has responded in ways that seek to maintain the norm.”Footnote 23 Zacher and Fazal emphasize the invigorated opposition to conquest, primarily by Western states and frequently operating through international organizations.Footnote 24 The coalition that ejected Iraq from Kuwait exemplifies this reactiveness against conquest. Although the international community failed to reverse Russia's annexation of Crimea, the condemnations and sanctions directed at Russia indicate an attempt to do so by means short of force. Intervening in some instances may deter attempts at conquest in others by making credible the threat to intervene.

Perhaps the most significant difference between these two possible effects of the norm is their predictions regarding territorial war. A territorial integrity norm that suppresses successful conquests primarily because outside states intervene to defeat aggressors implies a persistence of territorial wars like the Gulf and Korean Wars. Thwarting successful conquests is not enough to prevent war. To accomplish that, the norm must suppress conquest attempts generally, including failed attempts.

Observing a pattern of continuing conquest attempts and territorial wars without third-party interventions would not suffice to imply that the territorial integrity norm lacks widespread legitimacy. States seeking to violate a norm—would-be conquerors, in this context—can deny its applicability to their actions without questioning its validity. Alternatively, they can violate the norm while rejecting it outright. Norm scholars regard the former as less damaging to norms and even as indicative of their strength. A growing body of research suggests that this type of violation is common across issue areas.Footnote 25 In territorial disputes, states can claim that the territory they seized is rightfully theirs, thus denying that occupying it violated the norm. Indeed, if they believe this rationale, states can conquer territory without perceiving themselves to be violating the norm.Footnote 26

This possibility aids in reconciling the evidence I will present with past studies that find clear support for the discursive strength of the territorial integrity norm after 1945.Footnote 27 Studies by Korman and Gotberg document the demise of rhetoric seeking to legitimize territorial seizures “by right of conquest,” which suggests that the norm has exerted a transformative impact on conquest discourse.Footnote 28 O'Mahoney shows that third parties rarely endorse and often condemn conquests in the modern era, frequently via a policy of nonrecognition.Footnote 29 Along these lines, Lee and Prather report that 47 percent of Americans and 37 percent of Australians surveyed would support military intervention to reverse hypothetical conquests.Footnote 30 In contrast, about 75 percent of each would support condemnations and economic sanctions. It is possible for a norm to be widely perceived as legitimate without causing a commensurate reduction in proscribed behaviors or costly punishments of those behaviors.Footnote 31 This study does not directly investigate discourses surrounding the territorial integrity norm, which is to say that it leaves unchallenged the robust qualitative evidence of their strengthening over time.

Consequently, skepticism about whether the territorial integrity norm caused historic declines in the rates of conquest and war does not imply rejection of the norm's existence. This study does not question the perceived legitimacy of the norm, but rather the limits of its capacity to constrain costly state behavior: conquest attempts, successful conquests, interstate wars over territory, postwar border changes, and third-party military interventions to oppose conquest. This study shows that conquest attempts—both failed and successful—seizing small territories continued to occur and even to cause war, typically without third-party interventions. Given these conclusions, it remains to develop an alternative account of conquest after 1945.

The Evolving Relationship Between Conquest and War

Conquest and war naturally seem to coincide. Aggressors invade, defeat defenders’ armies, and take the territories they desire. This form of conquest declined precipitously after 1945.Footnote 32 However, its decline did not spell the end of conquest. Instead, conquest evolved as its relationship with war changed. Before 1945, challengers often initiated war as a first step toward conquering large territories. After 1945, challengers increasingly came to limit their aims to seizing smaller territories, then attempting to avoid war.

One way to understand this evolution is to distinguish two strategies of territorial conquest: brute force and the fait accompli.Footnote 33 The strategy of brute force—a term Schelling coined to describe imposing one's will by destroying or disabling the adversary rather than coercing their cooperation—seems to befit conquest.Footnote 34 For conquests of entire states, it is apt. However, it applies poorly to attempts to conquer small territories, which avoid war most of the time and sometimes avoid violence altogether.

In contrast, a fait accompli imposes a limited gain without permission in an attempt to induce the adversary to relent rather than escalate in response.Footnote 35 Each fait accompli is a calculated risk; in this context, a gamble that taking a piece of territory will not provoke war. Whether a fait accompli results in a successful gain or escalation depends on whether the state employing it has successfully gauged the level of loss the adversary will accept rather than go to war. Sometimes this succeeds, as with Russia's 2014 annexation of Crimea and China's seizure of the Paracel Islands in 1974. Other faits accomplis fail when they miscalculate and elicit a military response. Pakistan's 1999 infiltration of forces to occupy positions on India's side of the Line of Control in the Kargil district of Kashmir backfired when it provoked India to attack and retake the territory. The concept of the fait accompli is particularly useful for understanding attempts to conquer small territories. Whereas conquest once encompassed a mix of brute force and fait accompli strategies, this study will show that brute force declined after World War II while the fait accompli became the primary strategy of modern conquest.

This evolution took place because the decline of conquest is a symptom of the decline of war, not its cause. Past studies explain conquest's decline first and then use that finding to explain the decline of interstate war. The territorial integrity norm presides as the leading such theory. The revised history of conquest presented here reverses that causal arrow connecting the decline of conquest to the decline of war. The operative constraint restricts war-prone aggression, not border revision.

As states increasingly came to shy away from intentionally waging war, war-prone forms of conquest declined earlier and more strongly. Conquest attempts more consistent with the fait accompli strategy and its aim of avoiding war proved more enduring. These tend to target smaller territories, especially those with little or no population and no military garrison that would need to be removed. It could have transpired that states would forgo conquest almost altogether as they increasingly sought to avoid starting wars. Instead, states avoided only war-prone conquest while persisting with comparatively war-averse conquest.Footnote 36 Consequently, the decline of conquest was partial and incomplete, amounting to a qualitative evolution more than a quantitative decline.

If the decline of (war-prone forms of) conquest is merely a consequence of the decline of war, then its causes need not pertain directly to territorial conflict. Nonterritorial theories of the decline in interstate war can explain why conquest declined. For instance, the proliferation of liberal ideas—or of nuclear weapons—may have made states more reluctant to start wars.Footnote 37 The changing structure of the international system after 1945 might explain it.Footnote 38 Alternatively, the unique nature of US foreign policy as the strongest power in the international system might do so.Footnote 39 War aversion has many plausible realpolitik and ideational explanations. Mueller makes the case for a robust norm of war aversion.Footnote 40 The evidence I present accords better with a broader norm against aggression than a narrower territorial norm against conquest.Footnote 41 Pinker makes a similar claim about violence aversion more generally.Footnote 42 Hathaway and Shapiro attribute the declines of war and conquest to the strengthening of international law beginning from the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928.Footnote 43 Although both studies declined to challenge the territorial integrity norm, their arguments are not equivalent to it; each more naturally explains a decline of war-prone aggression than territorial revision. Although this study does not attempt to determine the nonterritorial causes of interstate war's decline after 1945, all of these theories fit the evidence more closely than the territorial integrity norm.

The most remarkable consequence of this evolution of conquest toward the fait accompli is that disputes over small territories take on great importance for international politics. The Falkland Islands and several hills in the Kargil region of Kashmir spawned wars. The Ugandan-Tanzanian and Cambodian-Vietnamese Wars began with small territorial seizures that provoked better-known retaliatory invasions culminating in regime change. India and China's competition to build posts in disputed border regions escalated to war in 1962, as did Ecuador and Peru's in 1995. Every case like these contrasts with several more where the challenger took similar actions, calculated correctly, and avoided war. Yet, even a comparatively bloodless fait accompli can poison diplomatic relations and sow the seeds of future conflicts. Russia's annexation of Crimea did just that to its relations with much of the world. This study will show that understanding the persistence and perils of conquest attempts employing the fait accompli strategy to seize small territories fills in a significant piece of the puzzle of modern interstate conflict.

The Decline of Territorial Conquest?

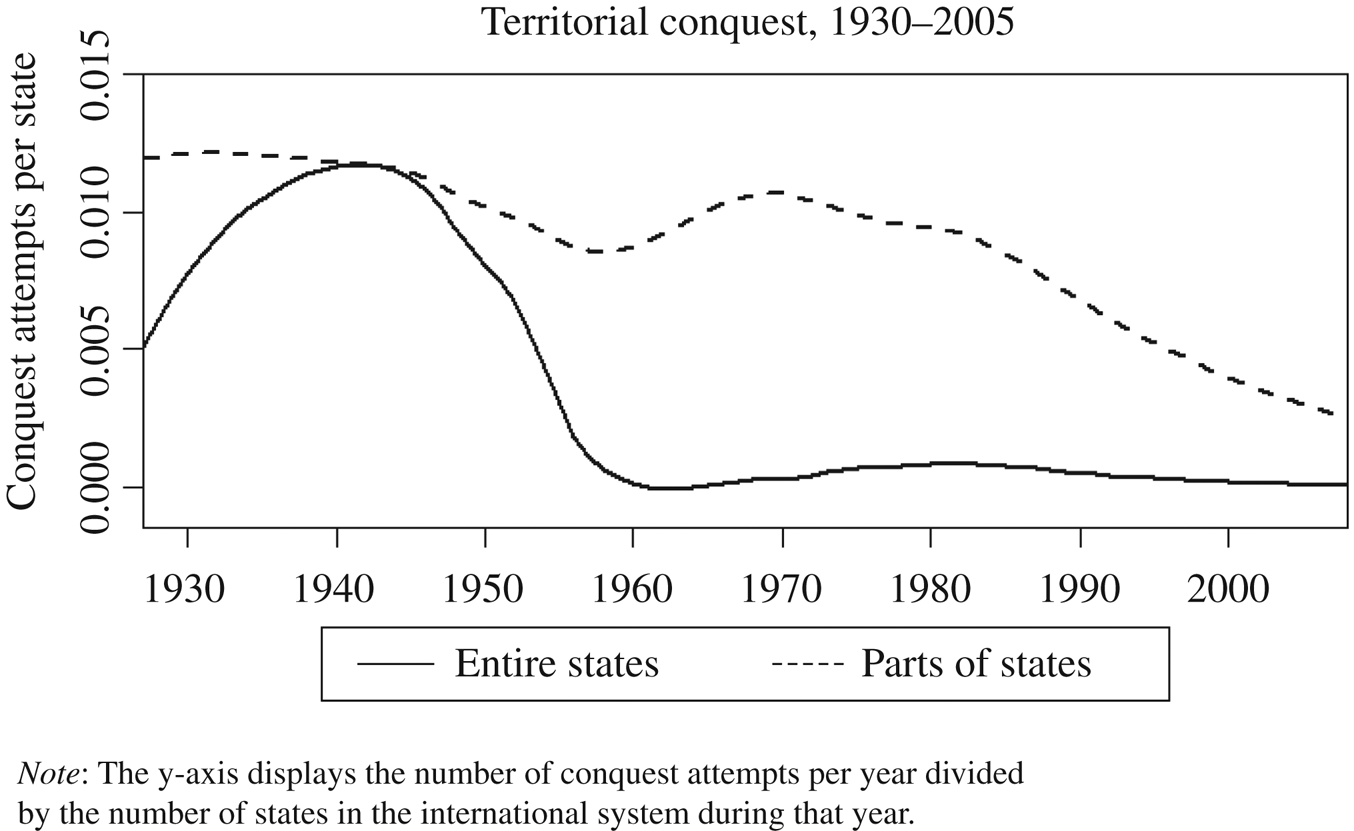

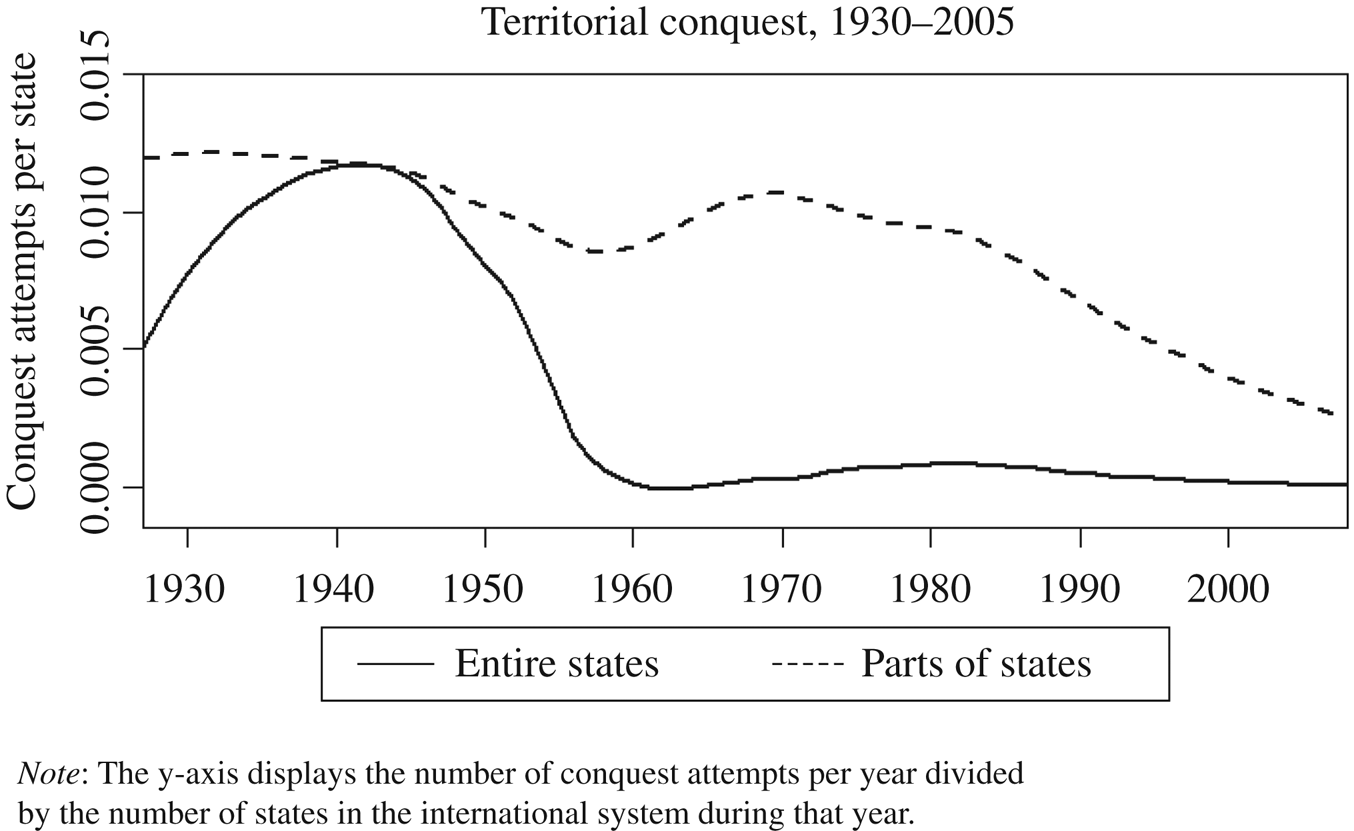

The consensus history of territorial conquest describes a sharp decline after 1945, particularly for attempts to conquer entire states, and the near-disappearance of all conquest after 1975. Figures 1 to 3 tell a different story using Modern Conquest data, which consist of 151 conquest attempts from 1918 to 2018.Footnote 44 A conquest attempt occurs when one state deploys a military force to seize disputed territory from another without permission and with the intention to assume lasting sovereign control of that territory.Footnote 45 Although conquest attempts are militarized assertions of sovereignty over territory, use of the term implies nothing about the legitimacy of the challenger's claim, legality under international law, or recognition by the international community. This definition excludes most cross-border military operations. Incursions other than conquest attempts include interventions in civil wars, cross-border raids, peacekeeping missions, and navigation errors by military patrols. The definition also excludes conquests by or against nonstate actors. Because of this restriction, the data omit important cases of secessionist and state-formation conflicts that transitioned uninterruptedly into interstate conflicts over territory such as the Arab-Israeli and Indo-Pakistani Wars of the 1940s.Footnote 46Figures 1 to 3 and all subsequent analysis further exclude retaliatory conquest attempts, which retake territory that was just lost to an initial conquest attempt. This is important when assessing the territorial integrity norm because a defender ejecting an invader cannot be considered a violation of the norm.

Figure 1. The decline of territorial conquest? All conquest attempts

The decline in conquests of entire states immediately after 1945 did not extend to conquests of parts of states. No reduction to near-zero levels culminated around 1975. Both facts provide evidence against a comprehensive decline in conquest attempts of all types as a result of the territorial integrity norm.Footnote 47 In Figures 1 to 3, the solid lines represent cases of one state attempting to conquer another in its entirety. The dotted lines do the same for conquests of parts of states. The figures smooth the trends using LOESS regression. Although the LOESS curves make use of data from 1918 to 2018, the figures are constrained to the 1930-to-2005 period because of the unreliability of the curves near the boundaries of the data where they cannot draw on data from both sides of the estimates. More than it declined in frequency, conquest shrank in size after 1945. In comparison to four attempts to conquer entire states, one state attempted to conquer part of another sixty-five times since 1945.

Figure 1 includes both successful and failed attempts at conquest. Figure 2 includes only the successes. A conquest attempt is considered successful if control over the territory persists immediately after the associated militarized dispute, crisis, or war ends. As comparing the figures suggests, the success rate of attempts to conquer parts of states remained remarkably steady at around 50 percent across the period.Footnote 48 This comparison between Figures 1 and 2 is specifically damaging to the claim that interventions to uphold the territorial integrity norm reduced the success rate of conquest attempts. Because conquest attempts tend to either fail quickly or succeed, Figure 2 is not especially sensitive to the duration that a conquest attempt must hold territory to qualify as successful. Of the thirty-four conquest attempts since 1945 in which the challenger “succeeded” by possessing the territory when the immediate conflict subsided, challengers had lost control ten years later in only five cases.Footnote 49

Figure 2. The decline of territorial conquest? Successful attempts only

The rising number of states in the international system after 1945 as a result of decolonization complicates this analysis of conquest trends. To determine whether this increase is masking the decline of conquest, Figure 3 adjusts Figure 1 for the number of states in the international system.Footnote 50 This adjustment does steepen the apparent decline in attempts to conquer parts of states. Intriguingly, however, the decline still begins around 1980. The decline in conquests of parts of states seems not to have begun immediately after 1945.

Figure 3. All conquest attempts adjusted for the number of states in the international system

Both the standard history and the revised history presented here are stories of decline. Nonetheless, the differences between them are significant for two reasons. First, the steepness of conquest's decline matters. The most widely used conquest data set, Territorial Change, records four conquests and zero annexations since 1975.Footnote 51 The Modern Conquest figure is thirty-five initial conquest attempts among forty-nine total conquest attempts. The substantive difference equates to one conquest attempt per year versus one conquest per decade. This means that conquest is still a recurrent and important part of international politics. It increases the expected number of interstate wars. Second, not all types of conquest declined simultaneously. I later show that the decline of attempts to conquer parts of states around the 1980s consists almost entirely of a decline in seizures of territories with characteristics that elevate the probability of provoking war. Comparatively war-averse conquest attempts without those characteristics continued to occur.

Importantly, conquest attempts remained surprisingly common across most of the world among states of diverse regime types and levels of power. No single region or group of states drives these trends. In Table 1, region refers to the location of the seized territory. The prevalence of conquest in regions other than Europe marks a departure from the concentration of territorial conflict in Europe before 1945. These conquest attempts more frequently occurred in the postcolonial world, often amid disputes over new international borders. That reflects, in part, the high-water mark of European imperialism and the resultant dearth of states considered sovereign elsewhere in the eastern hemisphere. Receding further in time to include more cases of colonization would qualify this comparison.

Table 1. The global breadth and diversity of conquest attempts, 1946–2018

Notes: *Regime type missing for Timor-Leste (1975).

Sources: Regime type data from Polity IV (Marshall and Jaggers Reference Marshall and Jaggers2002); major power data from Correlates of War 2017; regional power data from Lemke Reference Lemke2002.

Similarly, both the perpetrators and victims of conquest attempts include democracies and nondemocracies, great powers and minor powers.Footnote 52 The comparative rarity of conquest involvement for major powers reflects the larger numbers of regional and minor powers in the international system. However, given the history of disproportionate major-power involvement in interstate conflicts, the prevalence of minor-power conquest attempts deserves mention.Footnote 53 Norm scholars’ conjecture that powerful states are better able to violate norms finds no clear support.Footnote 54 Instead, the territorial integrity norm has had a limited capacity to constrain conquest attempts by a wide variety of states.

To explain why Modern Conquest data paint such a different picture from past studies supportive of the territorial integrity norm, Table 2 contrasts it with the three prior conquest data sets: Territorial Change, Territorial Aggressions, and State Deaths.Footnote 55 Four inclusion/exclusion criteria explain the discrepancies.Footnote 56 Deciding differently on even one of those four criteria suffices to generate a surprisingly different history of conquest. First, as shown in Figures 1 to 3, examining only conquests of entire states generated conclusions about the decline of conquest that do not extend to smaller conquests.

Table 2. A comparison of four conquest data sets

Note: Initial conquest attempts exclude retaliatory conquest attempts and those occurring amid a war that was already underway.

Second, data sets that approach conquest as an outcome exclude failed attempts at conquest.Footnote 57 The initial aggressor has lost nearly every war that began with conquest in recent decades, so omitting these cases leads to underestimating the enduring relationship between conquest and war.Footnote 58

Third, the most widely used data set (Territorial Change) largely omits successful conquests that failed to garner diplomatic recognition. This appears to be a consequence of identifying cases from cartographical sources—that is, starting from cases of maps changing and then ascertaining why they did so.Footnote 59 When conquests succeed in the modern era, the international community often eschews recognizing them.Footnote 60 Consequently, maps may not change. If not, the case does not enter the data set. One plausible explanation for the large number of affected cases is that the territorial integrity norm has curtailed the recognition of conquest more than the act of conquest. If so, the norm suppressed data on conquests, not conquests themselves.

Finally, excluding nonviolent conquests like Russia's in Crimea amounts to disproportionately excluding successful conquests. Modern conquest usually consists of the seizure of a small piece of territory in the hope of getting away with that gain when the victim declines to escalate in response. Oftentimes, violence occurs only when this fait accompli fails. This partly explains why Zacher concludes, “In fact, there has not been a case of successful territorial aggrandizement since 1976.”Footnote 61 The Modern Conquest data set contains twelve such successes before 2001 and sixteen through 2018.

The Decline of Territorial War?

Because territory has long ranked as the foremost issue over which states wage war, any decline in conquest should cause a decline in interstate warfare. If territorial conquest effectively ceased to occur, territorial war would too. However, an examination of interstate wars in recent decades suggests otherwise. To facilitate comparison, I focus on the window of 1976 to 2006, which Goertz, Diehl, and Balas use to highlight the declines of conquest and war.Footnote 62 According to the standard Correlates of War list, states waged eighteen interstate wars in that period.Footnote 63 Nine of those eighteen wars began with a conquest attempt according to Modern Conquest criteria.Footnote 64 Fighting for sovereign control over territory played a central role in four more of the eighteen.Footnote 65 That sums to thirteen territorial wars among the eighteen interstate wars. Table 3 lists these eighteen wars and the years in which they began.

Table 3. Interstate wars, 1976–2006

Table 4 extends this tripartite division of interstate wars back to 1918. It reveals only a small reduction in the proportion of territorial wars and wars begun by conquest attempts.Footnote 66 Although the proportion of territorial wars did decline, it did so only modestly—a far cry from almost ceasing to occur.Footnote 67 Territorial war remains critically important in international politics. Fazal's conclusion that wars of intervention and regime change have supplanted wars of conquest finds some support here, but only for great powers, principally the United States.Footnote 68 Since 1945, most wars that began with a conquest attempt occurred in the developing world pitting two nonmajor powers against each other.

Table 4. Has territorial war become rare?

All nine states responsible for the initial conquest attempts in the wars begun by conquest since 1975 lost the ensuing wars. At first glance, this seems to offer strong support for the proposition that interventions by the international community motivated by the territorial integrity norm caused these attempts to fail. However, that conclusion presupposes (1) frequent third-party interventions that caused (2) the success rate of conquest attempts to decline. The next section presents evidence against both claims. The Persian Gulf War is simply not representative of modern conquest. Why, then, so many defeats? Understanding that these challengers largely relied on the fait accompli as their strategy sheds light on those defeats. Under that strategy, challengers intend to get away with a gain without fighting a war. A political calculation to that effect supersedes a military calculation about how a war would go because no war is expected to occur. The resultant wars reflect the minority of cases in which the challenger miscalculated. Given that chain of events, a high rate of lost territorial wars is less surprising.

The evidence also does not support a decline in the rate of border changes after interstate wars to the extent Zacher concluded.Footnote 69 Zacher reports that nearly 80 percent of wars before 1945 ended in territorial redistributions but only approximately 30 percent since then. This seems to indicate a transformative, norm-induced change in the international system. However, to generate that result, Zacher compared data from Holsti before 1945 to his own list of territorial aggressions after 1945.Footnote 70 Those two sets of cases differ in ways that contributed to the strength of the discrepancy. Although Zacher uses it up to only 1945, Holsti's data extend to 1989, which permits comparison to Zacher's data from 1946 to 1989. In that period, Holsti identifies forty-one cases of “wars and major armed interventions” over the issue types Zacher classifies as territorial. Zacher reports thirty-four territorial aggressions. However, the two lists share only seventeen cases in common. Zacher's list includes incidents below the intensity threshold of Holsti's list, which includes many cases of contested secession—often resistance movements leading to decolonization—that Zacher excludes. Such cases quite often resulted in border changes. For both reasons, Holsti's list contains a greater proportion of border changes. Extending Zacher's pre-1945 methodology to the 1946 to 1989 period, the rate of border changes did drop below 80 percent, but to 59 percent rather than 30 percent.Footnote 71 Both high figures are artifacts of using secession-laden data to study conquest.Footnote 72

This decreased frequency of postwar border adjustments after 1945 does not imply the corresponding reduction in either conquest attempts or territorial wars that it appears to require. The victims of failed conquest attempts now more rarely take adversary territory as a sort of reparation after wars end. Instead, they more often limit their territorial aims to restoring the status quo ante.Footnote 73 Since 1945, only a few retaliatory conquest attempts sought territory other than what was just seized. Comparing Britain and France's territorial acquisitions after World War I to their comparative restraint after World War II illustrates this. Consequently, and because aggressors frequently lose territorial wars, the decline in border changes after wars exceeds the decline in wars fought over attempts to change borders.

Interventions to Oppose Conquest Attempts?

Did a strengthening territorial integrity norm spur more aggressive attempts to reverse conquests and thereby uphold the norm? The striking concentration of territorial wars among failed conquest attempts since 1975 seems consistent with this belief in increased norm-driven intervention. However, a direct assessment suggests otherwise. For attempted conquests of parts of states, third-party military interventions occurred infrequently and have not become more common in recent decades. For attempted conquests of entire states, third-party interventions have long been fairly common—likely for realpolitik reasons that predate the norm. Moreover, there is no large decline in the success rate of conquest attempts, as the comparison of Figures 1 and 2 suggested. Conquest attempts frequently fail, but they failed roughly as often before 1945.

By and large, the victims of smaller conquests have been on their own. Of the sixty-three initial conquest attempts targeting parts of states since 1945, in only five did a third-party state—a friend or ally of the victim—fire at least one shot in defense of the victim. Morocco's 1963 attempt to seize the Algerian provinces of Tindouf and Colomb-Bechar elicited Egyptian and Cuban intervention to support Algeria. Israel's 1967 seizure of the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Egypt prompted Syria, Jordan, and Iraq to intervene against Israel. In 1974, Greece intervened on behalf of Cyprus in response to Turkey's invasion. In 1977, Cuba and South Yemen intervened to defend Ethiopia against a Somali invasion of the Ogaden. In 1978, Mozambique deployed a single battalion to support Tanzania after Idi Amin's Uganda seized the Kagera Salient. The paucity of these cases combines with their clustered occurrence toward the middle of the postwar era (rather than the most recent decades) to suggest that third-party intervention did not grow steadily more common. If anything, the data hint at the intensity of Cold War proxy conflicts in Africa in the 1960s and 1970s.Footnote 74 Outside that era, violent interventions against conquest attempts targeting parts of states remained rare throughout the 1918–2018 period.Footnote 75

In contrast to the dearth of external interventions after attempts to conquer parts of states, military interventions have more often opposed attempts to conquer entire states. Coalitions reversed Iraq's 1990 conquest of Kuwait and North Korea's 1950 invasion of South Korea. Germany's 1939 invasion of Poland led Britain and France to declare war. Germany's 1914 invasion of Belgium did the same for Britain. Third parties may have a stronger interest in their allies’ survival—to preserve the balance of power, for instance—than in those allies’ retention of small border regions. This is consistent with the possibility that realpolitik governed decisions about whether to intervene to reverse conquests.

However, third-party interventions need not use violence to succeed. Robust diplomatic interventions by third-party states and international organizations could suffice to reduce the success rate of conquest. The diversity of forms of nonviolent intervention complicates observing them.Footnote 76 Distinguishing sincere efforts from token statements poses a particular challenge. Rather than attempt to observe these interventions and adjudicate among their varieties, Table 5 examines them indirectly by evaluating whether increasingly vigorous diplomatic interventions—consequences of a strengthening norm—increased the failure rate of conquest attempts over time. Overall, the data provide few signs of that. Instead, the failure rate of conquest attempts consistently lingers around 50 percent. The success rate of conquest attempts decreases only slightly after 1945.Footnote 77

Table 5. Outcomes of attempts to conquer parts of states

Past studies are more sanguine about international organizations’ contributions to reducing the success rate of conquest. Zacher's case narratives—in conjunction with a few high-profile cases like the Gulf War—laid the basis for this belief.Footnote 78 Those cases indeed establish that conquest attempts often failed in recent decades, sometimes because of third parties. However, conquest attempts failed frequently before the territorial integrity norm grew stronger after 1945. A high failure rate need not imply an increased failure rate. In this instance, there was no significant increase. Zacher's territorial aggressions data begin in 1946, which hindered making that comparison. Second, as discussed earlier, Zacher's exclusion of nonviolent conquests resulted in the disproportionate omission of successful conquests by selecting on the failure of challengers’ fait accompli strategy. Third, although brief case narratives can observe the occurrence of a diplomatic intervention, those data alone are insufficient for inferring that interventions caused outcomes. Consider Zacher's narrative for the 1977 Ogaden conflict: “An OAU [Organization of African Unity] committee called for respect for the former boundary. Somalia withdrew all forces by 1980.”Footnote 79 Somalia did not withdraw as a result of OAU diplomacy, but rather was militarily ejected by Ethiopia.

On balance, the evidence does not sustain claims that the territorial integrity norm vanquished conquest, greatly curtailed the incidence of interstate war, increased third-party military interventions to uphold the territorial status quo ante, or curbed the success rate of conquest attempts. That evidence opens the door for a new and different account of the evolution of conquest after 1945.

The Fait Accompli as the Strategy of Modern Conquest

As states increasingly sought opportunities to seize territory without initiating wars, the fait accompli became the predominant strategy of conquest. Before presenting the trends, I must first establish a stronger empirical basis for the fait accompli as a distinct strategy of conquest. Recall that brute force embraces war in an attempt to seize a large piece of territory.Footnote 80 The fait accompli, by contrast, seizes small piece of territory in an attempt to avoid war. War onset reflects the failure of the strategy, whereas for brute force it is the initial step in implementing the strategy.

Observably, faits accomplis target much smaller territories and provoke war less frequently. However, merely establishing the correlation between seizing larger territories and a greater probability of war would not establish the utility of this dichotomy. That result is overdetermined. Instead, Figure 4 takes a different approach. In brief, the two strategies target territories of discontinuously different sizes. Although seizing part of a state's territory and seizing all of it might seem to differ only in degree, that is, in effect, not the case. As the targeted territory grows larger, prospects diminish for getting away with taking it without provoking war. Once the stakes grow high enough that defenders will resist to the limits of their abilities, challengers have little reason to curtail their territorial ambitions. Consequently, challengers either aim for the entire territory and adopt a brute force strategy or aim to get away with taking a much smaller prize by fait accompli.

Figure 4. The bimodality of conquest, 1918–2018

Figure 4 provides the distribution of the sizes of territories seized in conquest attempts between 1918 and 2018 using the number of provinces as a crude measure of size.Footnote 81 That distribution exhibits a striking degree of bimodality. Seizing half—or one quarter, or three quarters—of a defender's territory is quite rare.Footnote 82 Although Figure 4 separates seizures of part of one province (the first bar) from seizures of exactly one province (the second bar), it thereafter combines them.Footnote 83 That is, seizing small parts of two provinces registers as seizing two provinces in the figure, and so on. Consequently, Figure 4 understates the bimodality evident in the data. The three cases of seizing ten or more provinces were failed attempts to conquer entire states: Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union, Japan's invasion of China, and North Korea's invasion of South Korea. The largest initial conquest attempts as a proportion of the defender's total territory aside from those were Yugoslavia's invasion of Albania in 1921, Japan's seizure of Manchuria in 1931, Russia's attack on Finland in 1939, and Turkey's invasion of Cyprus in 1974. Beyond those cases, events such as Israel's 1956 and 1967 occupations of the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip rank among the largest remaining conquest attempts. Put more simply, most conquest attempts seized small regions, especially after 1945.Footnote 84

The distribution of outcomes of modern conquest attempts are also broadly consistent with the fait accompli strategy. Approximately the same number of conquest attempts after 1945 occurred without any battle deaths (twenty-two) as led to a war of over 1,000 battle deaths (nineteen).Footnote 85 The nineteen wars underscore the continuing importance of territorial war in the modern era. The twenty-two nonviolent conquest attempts defy any assumption that violence inheres in conquest. They also cast doubt on the possibility that the territorial integrity norm falters only amid intense conflicts when the stakes are highest.

The Decline of War-Prone Conquest

One dominant thread runs through the evolution of conquest in the twentieth century: the decline of war-prone conquest. Figures 1 to 3 charted the first part of this change. Attempts to conquer entire states became rare immediately after the end of the Second World War; conquests of parts of states persisted. It remains to document the second. By the mid-1980s, the second stage was well underway: the decline of comparatively war-prone seizures of small territories. However, lower-risk territorial seizures fully embracing the fait accompli strategy again continued. As a result, war-averse conquests account for an increasing proportion of conquest attempts over time during the post-1945 period. The fait accompli became the predominant form of modern conquest not because it became more common in absolute terms but rather because it withstood whatever forces so diminished war-prone strategies of conquest.

To understand where states can attempt conquest with the least risk of war is to identify the conditions under which modern conquest tends to take place. What, then, are those conditions? Both the prevalence of geographically small conquests and the logic of the fait accompli point to an answer: low-value territories. Rather than fight for them, defenders should more willingly sacrifice smaller areas with less valuable attributes.Footnote 86 This reasoning dovetails with the emphasis on territory characteristics in past studies of territorial conflict, which emphasize population size, natural resources, strategic location, and ethnic identity motivations.Footnote 87

A statistical analysis of the conditions under which conquest attempts more often lead to war provides a tentative basis for identifying the characteristics of war-averse conquest attempts. The results suggest that population and strategic value correlate strongly with an increased probability of war (see the appendix for full results).Footnote 88 Natural resources and ethnic identity motives, surprisingly, do not.Footnote 89 Relative military power and regime type also fail to correlate with the propensity for war among conquest attempts. This study focuses on the two basic dimensions of territorial value that offer the best indicators for the war proneness of conquest attempts. The two standard measures of strategic value aggregate many diverse sources of it, complicating the task of drawing conclusions about its role.Footnote 90 Consequently, a related but simpler variable is used: the presence/absence of a military garrison in the seized territory. The gradual shifts away from seizing populous and defended territories reveal themselves clearly.

Seizing populous territories incurs a greater risk of provoking war than seizing unpopulated regions. The import of population for the probability of war comes as little surprise. Population factors into many different reasons that states value territory: economic production, political representation, prestige, moral responsibility to citizens, and more. The right side of Figure 5 confirms this. From 1918 to 2018, seizing territories with at least one major city (at least 100,000 inhabitants) led to war 78 percent of the time.Footnote 91 Seizing a populated region without such a city (such as several villages) provoked war 36 percent of the time. Seizing an unpopulated area, in contrast, provoked war only 9 percent of the time. This three-level scheme is adopted from the ICOW Territorial Claims data set, but the variable was coded anew. ICOW's population variable describes the full claimed territory, whereas Modern Conquest data describe the seized region only.Footnote 92 Consistent with the fait accompli strategy, challengers sometimes occupy only a small part of a disputed territory.

Figure 5. Conquest attempt trends: Population

The left side of Figure 5 shows that conquest attempts targeting populous territories declined earlier and more sharply. This decline began in the 1970s and proceeded rapidly to the present. Indeed, around 1990 seizing unpopulated areas became the modal type of conquest for the first time. The sharp decrease in the rate of conquest attempts seizing populated regions around the 1980s marks the second stage of the evolution of conquest as it became increasingly war averse.Footnote 93

Attempts to conquer territories with military garrisons exhibit a similar evolution around the 1980s. States can attempt to seize territory while minimizing the risk of war by avoiding garrisoned territories. Taking full control of a garrisoned territory requires dislodging adversary forces, usually by attacking them. The garrison variable observes whether the defender had already deployed forces to the area that was then seized.Footnote 94 Specifically, it records whether at least one armed and uniformed state official was stationed in the seized territory when the conquest attempt began. This definition includes militia and police, who are not easily distinguished from soldiers in some contexts. I refer to ungarrisoned territories as undefended. In line with expectations, seizing a garrisoned territory usually implies combat with the garrison. Only five attempts to seize a garrisoned territory did not result in at least one battle death.Footnote 95

Although garrisons can function as an indicator of strategic value, the theoretical basis for placing emphasis on garrisons comes from the deterrence literature's concept of tripwires. This concept holds that states can forward deploy troops to a contested area to more strongly commit themselves to fight if that area—and thus the troops—come under attack.Footnote 96 Deterrence theorists generally agree that tripwires enhance credibility. When tripped, war becomes more likely.Footnote 97 It follows, then, that conquest attempts that limit their ambitions to undefended areas can more often avoid provoking war.

The right side of Figure 6 confirms that seizing a garrisoned territory entails a greater risk of war. With a garrison, war resulted 46 percent of the time. Without one, war broke out only 6 percent of the time. Unfortunately, causation here remains opaque. The presence of a garrison could cause this increase in the probability of war. Alternatively, defenders may deploy garrisons to regions that they were already more likely to violently defend for other reasons. Regardless, the ex ante presence of a garrison provides an indicator of higher war risk.

Figure 6. Conquest attempt trends: Military garrison

The left side of Figure 6 shows that conquest attempts seizing undefended areas have proven more persistent than seizures of garrisoned territories. Around 1990, seizing undefended areas became the majority of conquest attempts for the first time, underscoring the declining war proneness of conquest. Because garrison presence and population correlate closely, Figures 4 and 5 largely capture the same change. The strength of this correlation is interesting considering the significant number of forward military positions and posts in unpopulated but disputed border areas. It suggests that challengers generally prefer to work around garrisons by instead seizing nearby empty areas, which is consistent with the fait accompli strategy.Footnote 98 The Spratly Islands, for example, became a peculiar hodgepodge of interspersed military posts because several states gradually seized islands that remained unoccupied instead of assaulting extant garrisons.Footnote 99

Over the full 1918–2018 period, significant proportions of conquest attempts seized unpopulated territories (39 percent) and undefended territories (41 percent).Footnote 100 These figures suggest the existence of a large pool of conquest attempts with ambitions limited to territories whose seizure comes with a reduced risk of war. Those figures rose over time. Unpopulated territories account for 28 percent before 1980 but 60 percent since then. Undefended territories account for 31 percent before 1980 but 60 percent since then. From those trends, the picture of modern conquest starts to become clear. War-prone conquest declined disproportionately while war-averse conquest consistent with the fait accompli strategy largely persisted, becoming the modern form of conquest.

Figures 4 and 5 hint at a possible decline in even war-averse territorial conquest in the early twenty-first century. Time will tell if this is truly the trend or merely a temporary lull. Even if the decline continues, projecting these trends forward still suggests the description of modern conquest presented here should hold for the immediate future.

How Attempts to Seize Small Territories Will Shape the Twenty-first Century

Although conquest evolved in fundamental ways, the widespread belief that the territorial integrity norm largely vanquished conquest understates the enduring prevalence of both territorial conquest and territorial war. An alternative understanding of the norm's effects—that challengers continued to attempt conquest but largely failed due to norm-inspired interventions by the international community—also finds little support. Military interventions by the international community to reverse conquest attempts happened infrequently and have not significantly reduced the success rate of conquest attempts. None of the evidence presented here challenges past qualitative research reporting that the norm's discursive legitimacy remains robust. After all, by asserting that the seized territory was already rightfully theirs, challengers can seize territory while denying that they have violated the norm. Its legitimacy notwithstanding, recognizing the limits of the norm's strength as a constraint against conquest is vital for understanding interstate conflict since World War II.

Conquest is not gone, but it has changed. The International Relations field continues to grapple with the question of why interstate war, particularly high-intensity war and great power war, declined after 1945. This study does not settle that fundamental question. Whatever the reasons, these forces extended into the territorial realm and gradually transformed the nature of territorial conquest. As the fait accompli became the predominant strategy of conquest, the most war-prone form of conquest (entire states) declined first, immediately after 1945. Then the intermediate form (populated territories, garrisoned territories) declined around the 1980s. The least war-prone form of conquest (unpopulated territories, undefended territories) persisted. Territorial conquests have not gone away but rather have become smaller, more targeted, and less violent.

Small territorial seizures that usually do not lead to war matter more than it may at first appear. Conquest remained the primary initiating event for wars after 1945 and even after 1975. There is tension but not a contradiction between a behavior usually not leading to war and that same behavior instigating most wars. War is rare and becoming rarer. Nonterritorial interstate war has never been common. Consequently, despite the increasingly war-averse nature of conquest attempts, they remain central to the causes of most interstate wars. Consider, for instance, the nightmare scenario of nuclear war. To date, a pair of nuclear powers have fought each other with significant casualties on two occasions: China and the Soviet Union over Damansky Island in 1969 and India and Pakistan over Kargil in 1999. Both conflicts began with a military deployment to seize a small, unpopulated border territory.

Looking to the future, the most plausible scenarios that culminate in armed conflict between China and Japan begin with the disputed Senkaku Islands, which remain unpopulated and undefended. China's disputes with the Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia over the Spratly Islands raise similar fears despite the small garrisons stationed there. Although the potential for a Chinese invasion of Taiwan continues to loom, a more limited Chinese seizure of Taiwanese islands like Kinmen, Mazu, and Itu Aba better fits the mold of modern conquest. Similarly, enduring disputes surrounding China's border with India—often over remote unpopulated areas—linger as a potential source of conflict. The 2017 Doklam crisis could be illustrative of events to come. Elsewhere, the specter of future Russian territorial advances in Ukraine, Georgia, Estonia, and beyond now compete with terrorism at the top of the European security landscape. Territorial conflicts remain common in regions with newer borders, including the Middle East and Africa.

Across the world, the most worrisome scenarios for interstate conflict tend to return, time and again, to conquest attempts. Seizing a small piece of territory will likely serve as a crucial step toward war, if such a step is taken. Successfully preventing or properly managing the response to a sudden fait accompli in a seemingly unimportant peripheral area may well determine whether war begins. Far from the marginal phenomena that they may at first appear, attempts to get away with seizing small territories may prove to be a defining feature of the twenty-first-century interstate security landscape.

Appendix

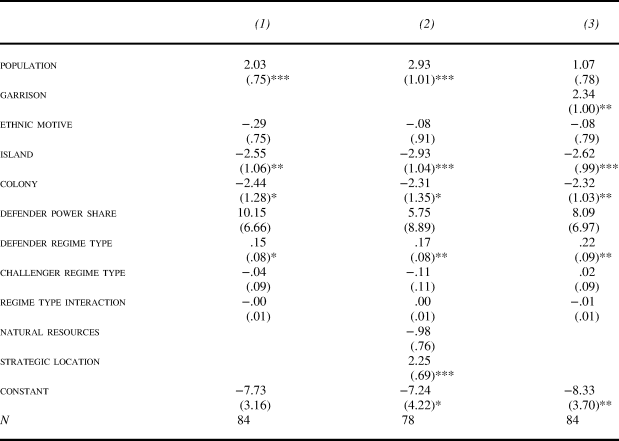

The choice of which territory characteristics to use as indicators of war-averse conquest relies in part on the results of a statistical analysis. Because neither a full analysis of the conditions under which conquest attempts provoke war nor the inference of any causal effects therein fall within the scope of this study, the results are merely summarized in brief. Table 6 presents results from four statistical models that assess the war proneness of conquest attempts. Attempted conquests of parts of states serve as the unit of analysis. The temporal scope is 1918 to 2018. War is the dependent variable using Correlates of War data. Each column displays results from a logit model with the designated variables included and standard errors clustered by militarized dispute. The clustering affects only a few cases such as Egypt and Syria's invasions of Israel in 1973. The first column provides the basic model, incorporating Correlates of War military expenditures data to assess power and Polity data for regime type.Footnote 101 Defender power share is equal to the defender's military expenditures divided by the sum of that and the challenger's expenditures (each logged). The second column adds ICOW data on the strategic and natural resource value of the seized territory, sacrificing a few observations that have missing data.Footnote 102 The third column adds the garrison variable. Because the garrison variable is post-treatment to the other variables, the first three models serve to examine those variables and the fourth model to evaluate garrisons alone.

Table 6. The conditions under which conquest attempts more often lead to war

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this article may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XLYTC7>.

Acknowledgments

I thank Andrew Bertoli, Paul Diehl, Marina Duque, Tanisha Fazal, Gary Goertz, Phil Haun, Paul Huth, Stig Jarle Hansen, Michelle Jurkovich, Melissa Lee, Jonathan Markowitz, Nicholas Miller, Vipin Narang, Kenneth Oye, Barry Posen, Kenneth Schultz, Kathryn Sikkink, Nina Tannenwald, Ben Valentino, Alec Worsnop, two anonymous reviewers, and the editors for their comments and insights. My thanks to Joshua Allen, Jamie Hinton, Christopher Jackson for research assistance.