An emerging research agenda examines the international dimensions of civil war.Footnote 1 Conflict economies, with global buyers and transnational networks, are a core focus of how armed groups connect to the international system.Footnote 2 Existing research expects wartime trade to operate through underground networks able to keep to the shadows and evade state authority. Yet little is known about a basic step in this process: how do illegal actors bridge their resources to formal markets? Drawing on original records from armed groups and their trading partners, I examine new evidence that rebels use state institutions as tools to pass resources to global markets. Whereas states are recognized actors in the international system, rebels are, simply put, illegitimate when it comes to financial transactions. By taking over state agencies in conflict zones, rebels can use the stamp of state to place a legal veneer on illicit activities. This strategy of legal appropriation enables rebels to better operate in a normative context that values state recognition. It reveals a fundamentally different model of how conflict actors skirt sanctions and access global markets not by evading the state but by infiltrating its institutions. I develop a framework of how this strategy works and the novel implications it reveals for state fragmentation, rebel governance, and clandestine trade.

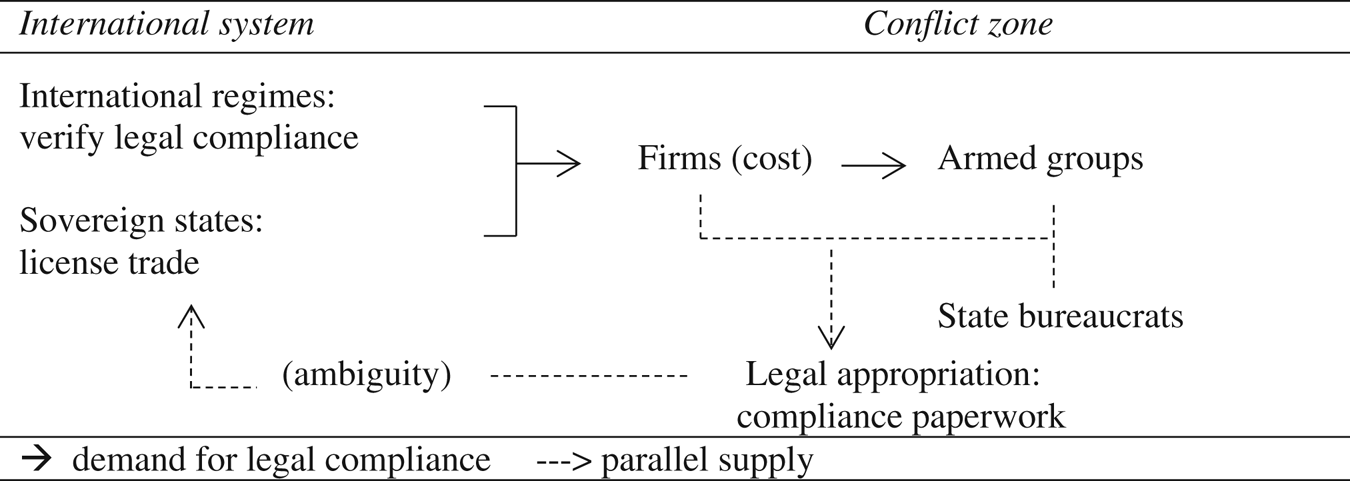

The framework contributes to understanding the how of wartime financial transactions. Building on research on rebel governance and illicit global markets,Footnote 3 it demonstrates how the international context of sovereignty norms and sanctions regimes generates incentives for rebels, firms, and bureaucrats to coordinate around this legal veneer. In particular, rebels can convert resources into revenue, firms can claim legal cover for engaging in otherwise illicit trade, and the resulting ambiguity can forestall action by international regulators seeking to stamp it out.

I substantiate the argument with original data from the internal files of a prototypical resource war, the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Congo is seen as the benchmark case of conflict markets in scholarship and policy, so much so that sanctions regimes looked to its wars to design procedures to curb rebel financing worldwide.Footnote 4 Yet a common tactic of wartime exchange, legal appropriation, eluded detection, compromising policies around transparent supply chains and theoretical understandings of conflict markets. During fieldwork, I gained unprecedented access to the records of the largest armed group in the Second Congo War (1998–2003), the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD). These rebel financial ledgers, payment slips, and correspondence with foreign buyers help fill an empirical knowledge gap about clandestine markets.Footnote 5 They provide unusually fine-grained insights into the mechanisms of civil war transactions and allow me to study wartime trade in a systematic way.

Three main pieces of evidence illustrate the framework. First, an analysis of 126 contracts between rebels and firms engaged in cross-border trade documents frequent references to domestic laws and institutions to construct a legal veneer. Second, an examination of payment records shows that most firms purchasing conflict resources routed funds to rebels via state agencies, creating an official paper trail to conceal illicit actions. Third, real-time statements from actors engaged in this process show that firms demanded “legal cover” to trade with rebels,Footnote 6 and that international regulators struggled to sanction firms because of the ambiguity created by this strategy.

The framework and evidence hold important theoretical and policy implications. They contribute to civil wars research by reframing rebels’ relations to formal laws, institutions, and markets. To effectively connect resources to global buyers, armed groups need tactics of crossing the border between illegal and legal practice. More than simply appearing state-like, this can involve converting the material structures of bureaucracy—official documents, stamps, and seals—into tools for legitimation. This insight builds on and extends research on how rebels mimic statehood.Footnote 7 It shows that armed groups can operate more like criminal organizations that infiltrate, rather than supplant, state institutions than previously realized.

For international relations scholars, the framework draws new connections between cross-border markets in conflict zones and the legal recognition of states in the international system. The state system rests on the assumption that central governments monopolize juridical power across national territory regardless of de facto control.Footnote 8 Yet, rebels who are excluded from this status can circumvent this norm by seizing state institutions. In short, military control may be more closely linked with the ability to access and exploit a legitimate status.

For studies of state building and fragmentation, findings demonstrate that the bureaucratic shell of weak states is transformed, not absent, in conflict zones. Paradoxically, nonstate actors have financial incentives to sustain domestic state institutions, but in ways that weaken central governments. Moreover, state actors at all levels of the national apparatus, including rank-and-file bureaucrats, can participate with violent organizations in ways that undermine cohesive central rule.

Finally, these findings contribute to research and policy on illicit markets. Existing policies to curb conflict financing rely on a meaningful boundary between state and nonstate actors. For instance, sanctions regimes, due diligence policies, and transnational advocacy networks seek to prevent global consumers from funding violence by ensuring that firms pay states, not rebels, in conflict zones.Footnote 9 However, norms and sanctions meant to reduce trade with rebels can incentivize new tactics to evade scrutiny. By passing trade through recognized institutions, rebels and firms can challenge the rules from within the system.

International System and Wartime Markets

Armed groups are players on the international stage, but relatively little is known about their financial strategies at this scale. There is extensive debate about how external markets affect rebel governance at the domestic level: do lucrative resources extend war, or build informal order?Footnote 10 Do lootable commodities, or social connections, shape rebel violence against civilians?Footnote 11 Across these debates, however, there is a relative consensus on the tools and relationships that armed groups use to move resources across borders: underground, informal networks. Scholars demonstrate how rebels work through informal banking systems,Footnote 12 trust and reputation with civilian trading networks,Footnote 13 or under-the-table deals with foreign governments to integrate into global markets.Footnote 14 As Ahram and King emphasize, such tacit connections are what make armed groups “uniquely gifted boundary crossers” when it comes to illicit exchange.Footnote 15 This view reflects broader expectations that rebels’ ability to keep to the shadows and avoid the reach of state institutions is what enables their success in transnational war.Footnote 16

Yet there is a critical overlooked question: How do resource-rich rebels convert commodities into tools for waging war, given their limited ability to access formal markets? As Hazen points out, physical control over resources is distinct from rebels’ ability to convert resources into usable revenue streams.Footnote 17 To effectively connect resources to global economies, rebels must find a way to navigate the border between illegal and legal practice. In short, wartime trade may not be simply about deploying informal relations, but blurring the boundary of informal and formal rules and markets.

This question is understudied, but there are important theoretical and practical reasons to expect it lies at the heart of conflict economies. First, rebel governance research examines how armed groups operate in a broader political context that rewards state affiliation. Scholars like Huang, Mampilly, and Tull demonstrate how groups like the Sudan People's Liberation Army and Tamil Tigers mimic state rhetoric and organize diplomatic missions to gain seats at negotiation tables and tax humanitarian intervention.Footnote 18 This work demonstrates that rebels’ ability to connect with the global system is linked to their ability to navigate between a nonstate and state-like status. And yet, this insight has not been applied to their global economic transactions.

Second, maneuvering this illegal-legal status is a standard part of illicit global economies.Footnote 19 Scholars of illicit markets show that firms use intricate webs of offshore financing, professional intermediaries, and anonymous shell corporations to wash dirty money as legal.Footnote 20 Criminal organizations also route goods through third countries, buy off government officials, and exchange illicit resources for innocuous commodities. For instance, Mexico's Sinhola drug cartel deposited funds into formal banking systems to obtain hard currency, launder profits, and alter records.Footnote 21 These actions enable actors in clandestine markets to make resources fungible and access larger markets in the formal sector. They do so by exploiting the same institutions as legitimate finance to cover up illicit actions.Footnote 22 Conflict economies are one type of illicit market. Yet although cross-infiltration between violence and formal institutions is a basic part of studies of illicit global markets, it has been rarely examined in research on wartime trade.

Finally, growing sanctions regimes heighten demands for a legitimate status in conflict-affected markets. United Nations sanctions committees, multilateral efforts like the Kimberly process and Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, US legislation, and voluntary corporate initiatives like the Geneva Declaration have proliferated since the early 2000s to curb conflict financing. These regimes seek to prevent global markets from funding civil war violence by ensuring that trade passes through state channels, not rebel hands. As the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Due Diligence Guidelines stipulate, “We will not tolerate any direct or indirect support to non-state armed groups … We will ensure that all taxes, fees, and royalties … from conflict-affected and high-risk areas are paid to governments.”Footnote 23 Sanctions committees designate armed groups as “illegal” and penalize their trading partners by freezing bank accounts and seizing assets.Footnote 24 Growing transnational advocacy and consumer demand also raise reputational costs to firms.Footnote 25 Meanwhile, on-the-ground UN investigators deployed on Group of Experts panels across diverse conflict zones heighten scrutiny in rebels’ backyard. Although changes in the international system can reshape rebel tactics and capabilities,Footnote 26 little is known about how conflict actors respond to this new institutional environment when it comes to financial strategies.

This gap leaves key questions overlooked: how does the legal recognition of states—the underlying principle of the international system—shape the tactics and institutions of armed group exchange? Do sovereignty norms moderate rebel behavior, or reroute how they finance violence? Do sanctions create incentives for firms’ compliance, or workarounds? A deeper look inside the tool kit of options available to actors in conflict markets is needed.

Skirting the System: Legal Appropriation in Civil War

State administrations are one such tool. The international context of sovereignty norms and sanctions regimes raises costs to trade with rebels, but it also creates a legal loophole that rebels can exploit. The stamp of the state is the recognized instrument that produces legality. State rule is recognized across national territory and at all levels of the bureaucratic apparatus.Footnote 27 This norm means that state agencies maintain a legal status even where central governments lack military control.Footnote 28 By coopting state agencies that persist in conflict zones—controlling the stamp of the state—rebels can build power over the instruments that produce a legal status. In short, in a world of international economic flows in juridically sovereign yet conflict-ridden states, rebels can use state administrations to manufacture legality.

I call this practice “legal appropriation.” The tactic meets international demands for legal compliance with a parallel supply of state legitimation (Figure 1). Parallel certification in turn creates ambiguity about what constitutes (il)legal practice that can complicate efforts at enforcement.Footnote 29 Following these incentives along steps in the supply chain will illustrate the framework.

Figure 1. Concealing conflict markets

Rebels: Occupying State Agencies

Illicit markets often require tacit relations with government officials, but rebellion enables armed groups to directly control state offices. These can include taxation bureaus, regulatory offices, sub-branches of national ministries, and parastatals. As rebels gain territory, state agencies remain geographically fixed. Civil wars research demonstrates that military control can lead administrations like these to switch sides.Footnote 30 Rebels can induce compliance by threatening force and replacing agency heads with cadre members. For their part, rank-and-file bureaucrats may accept new rebel principals as a survival strategy during war.Footnote 31

Rebels appropriate state agencies across diverse conflicts like Iraq, Yemen, Côte d'Ivoire, and Sri Lanka.Footnote 32 In Central Africa Republic (CAR), for instance, rebels took over agencies charged with monitoring diamond markets, known as Special Anti-Fraud Units (Unité spéciale antifraude—USAF). UN investigators arriving at these bureaus found that, “militarily, the ex-Seleka elements operate with USAF agents or have taken the USAF agents hostage to work for their account.”Footnote 33 Rival groups also occupied USAF buildings and obtained mining permits.Footnote 34 As a result, rebels on all sides of conflict controlled the very bureaus that certified diamonds as legal.

Rebels have financial incentives to preserve state agencies because they supply an important resource for cross-border markets: the legal status of official documents. Rebels may physically control resources and the populations that access them, but they sell in a transnational context that penalizes their trade. Bureaucratic documents can transform illegal resources into usable revenue by mitigating risks to buyers. OECD Guidelines demonstrate that regulators verify compliance by “identifying the factual circumstances of [firms’] activities and relationships and evaluating those facts against … national and international law.”Footnote 35 Bureaucratic documents produce these legal “facts.” A stroke of a pen on certificates, licenses, and receipts can misrepresent the nature of illegal commodities and create images of legitimate payment.Footnote 36 By controlling bureaucratic agencies, rebels can create parallel facts of legitimation to sell goods in trafficking markets.

Firms

Firms have diverse incentives to participate in this legal fiction. Some internalize norms and seek certification out of a desire to comply with legislation.Footnote 37 Others willfully flaunt the rules for profit or survival.Footnote 38 For these firms, false certification is part of standard practice. Transparency norms, consumer demand, and sanctions committees reduce firms’ ability to channel dirty money to accounts directly.Footnote 39 Studies of illicit global markets show that firms invest considerable effort to conceal money trails and obscure the identities of buyers and sellers.Footnote 40 Firms launder revenue through intermediaries and complicated paper trails. Bureaucratic documents provide a valuable layer of intermediation by creating distance between firms and violent actors.

Bureaucratic licenses offer plausible deniability. To be considered illegitimate, firms must knowingly trade with rebels.Footnote 41 Official documents, which indicate intent to pay state actors, provide a layer of legal defense. Attorneys of firms purchasing gold from rebels in CAR, for instance, provided payment receipts to state bureaus to argue that “clients do not have any information and/or awareness of taxation and/or security payments being paid to [combatants].”Footnote 42 In lengthy supply chains in conflict markets, money trails ending with bureaucratic certification also make for an easier sell to headquarters and upstream buyers.

International Regulators: Rules and Ambiguity

Legal appropriation creates an alternative supply of state licenses, certification, and legitimation. At some point, someone may be duped, whether regulators, upstream firms, or consumers who view documents as legally authentic. Yet the strategy need not be fully convincing to succeed. By exploiting the legal affiliation of state agencies, this strategy can complicate enforcement by creating ambiguity in what constitutes legitimate practice.Footnote 43

To distinguish legal from illegal actions, sanctions officers and advocacy organizations examine whether payments are made to states. Whereas trade with rebels is penalized, “legal taxes, fees, and/or royalties” do not constitute support for rebels.Footnote 44 In this case, applying the rules—verifying payments are made to state bureaus—can create ambiguity in enforcement. UN investigators demonstrate this dilemma in CAR. Here, despite evidence that a gold exporter “maintains a network of fraud to the United Arab Emirates,” investigators declared the firm “legal due to the fact that it respects the exportation procedures of precious metals conforming to the mining regulations.”Footnote 45 On-the-ground investigators express confusion at parallel legitimation; buyers and regulators farther from conflict may be more easily misled.

Meanwhile, central governments have varied relations with rebels.Footnote 46 They can also range from rivals to complicit in legal appropriation. Governments with knowledge that rebels control state agencies may tolerate their presence, coordinate around financial kickbacks, or try to stop these actions. Others may simply lack information about activities in rebel territory. Across these possibilities, what is significant is that governments lose a monopoly on legal certification supplied from national territory.

Generalizability

The scope conditions for this strategy are more common than it may appear: state bureaus often persist in conflict zones, and international norms should create standard incentives for rebels and their trading partners to seek legal cover. Rebels often coopt state agencies, including in wars in relatively strong states like Sri Lanka to failed states like CAR. These interactions span from “warlord” rebels in Liberia,Footnote 47 religious extremists like the Islamic State,Footnote 48 parochial insurgents with ethnic agendas like the Houthis in Yemen,Footnote 49 to breakaway groups like the Tamil Tigers.Footnote 50 Bureaucratic takeover across varied levels of state capacity and rebel ideologies suggests these interactions are not limited to any one region or type of conflict.

Second, rebels forge connections with formal state and economic institutions for market transactions across diverse wars. Guerillas in Colombia formed “symbiotic relationships” with bankers to invest narcotics revenue in formal economies.Footnote 51 Kosovo's Government in Exile, the basis for the Kosovo Liberation Army, worked with legal experts to design transactions that could evade scrutiny, while the União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola held money throughout European banks and offshore accounts.Footnote 52 Similarly, in Yemen, a tribal elder under Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula explained that even extremist groups “need the official documents” to sell crude oil.Footnote 53

Resources can be illegal because of the actors who control them or the nature of the commodities. False bureaucratic paperwork is used across both types of resource transactions: it can conceal the identity of actors or misrepresent the nature of resources. The Sinaloa Cartel used formal banks to obtain altered records that whitewashed the origins of money flows and concealed the nature of transactions.Footnote 54 To move goods across borders, bureaucrats in central Africa also misrepresented illegal arms as innocuous goods like petrol and sugar on official paperwork.Footnote 55 The underlying relationship of legal appropriation is similar: rebels forge subversive relationships with state agents to obtain formal—but falsified—paperwork to cross the border between illegitimate and legitimate practice.

Data and Research Design

To study wartime transfers, I examine how firms interacted with the largest armed group in the Second Congo War. Congo is a good case for several reasons. First, scholars and policymakers treat Congo, and the RCD rebellion in particular, as a “paradigmatic” case of resource wars.Footnote 56 Based in the extreme periphery of eastern Congo, the RCD controlled vast resource deposits, held external support from Rwanda, and drew labels of “blood diamonds” and “blood tins” for its trade.Footnote 57 Its external patrons, state weakness, and porous boundaries are attributes seen as representative of conflict markets more broadly.Footnote 58 Second, existing research on this war focuses on informal networks and foreign sponsors; state institutions seem outside the plausible scope. Third, the war brought the issue of conflict financing to the international agenda. It motivated multilateral efforts, domestic legislation, and transnational advocacy networks to stop the conflict mineral trade.Footnote 59 Demonstrating that a critical tactic went overlooked in a conflict that defined the agenda suggests that it could go undetected elsewhere. It invites scholars to reexamine cross-infiltration across a broader universe of cases.

Data come from rebels’ internal records. During three years’ fieldwork between 2009 and 2017, I negotiated access to the files of Congolese armed groups including the RCD. Files include financial statements, contracts, mining permits, payment slips, and identification documents of foreign buyers in rebel territory. Records also include export certifications, bureaucratic forms, and official stamps that dressed transactions in a legal veneer.

I performed several verification checks to assess the credibility of the data. A first internal validity check pertained to data collection and content. I gained unrestricted access to the files and selected records unsupervised at rebel field sites, mitigating risks that collection would bias the content. Rebels kept records in confidential locations and produced them for internal purposes. Records contain evidence of transactions with sanctioned entities and include files labeled “confidential” or “secret.” Extensive field knowledge and fluent Swahili were necessary to gain privileged access to the data: I learned of the records through networks established during a year-long residence in Congo before doctoral research (2009–2010), accessed the records thereafter (2011–15), and returned for follow-up interviews (2016–17).

As an external validity check, I compared trafficking circuits in the rebel files against investigative reports. In 2000, the UN Security Council created the Panel of Experts on Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources to investigate Congo's conflict economies. I created a roster of firms the UN Panel identified as “illegally” operating in RCD territory.Footnote 60 Seventy-eight percent of firms are represented in the files I recovered. My files also reveal extensive information beyond the UN reports. This type of overlap would be expected of two independent studies of war economies that relied on original records as sources. For this study, all rebel trading partners were anonymized: my purpose is to evaluate patterns in illicit exchange, not present a whodunit case.

I use these data to examine rebel markets across two steps. A first asks how extensively rebels and firms coordinated in legal appropriation. I evaluate whether the RCD built a legal cover into export trade, then examine firms’ payments to test whether state agencies provided channels for exchange in practice. A second step probes mechanisms. It traces how global norms created costs to deals that lacked a legal cover, and how using state bureaus created ambiguity about legitimate practice. Table 1 summarizes these steps and the data that assess them. It indicates where readers can view rebel files used to evaluate the argument.

Table 1. Research design

Legal Appropriation: A Systematic Measure

As the RCD organized and gained territory, it took over persisting branches of state agencies.Footnote 61 These included taxation agencies (Direction Générale des Recettes Administratives, Judiciaires, Domaniales et Participations [DGRAD]), customs and export offices (Office des Douanes et Accises [OFIDA] and Office Congolais de Contrôle [OCC]), and mineral certification bureaus (Centre Nationale d’Expertise [CNE]). These agencies are officially tasked with verifying that trade in commodities like diamonds and gold follows national legislation. As the RCD took over, it restructured agencies’ chains of command so that bureaucrats reported and remitted funds to rebel headquarters in Goma. It typically retained rank-and-file bureaucrats and created new “coordination” bureaus of rebel management to supervise low-level agents. In some cases, bureaucrats resisted rebels or siphoned money from transactions. Yet across RCD holdings, bureaucrats also had interests in keeping their agencies alive. Bureaucrats maintained their offices as Kinshasa's influence waned—in part due to personal interests to use their posts as sources of authority and extraction.Footnote 62 Their actions created a fragmented national bureaucracy, but one still run through government offices, uniforms, and documentation. Rebels taking over these bureaus gained control over these levers of statehood.

Legal Veneers: Export Agreements

To systematically measure how state agencies provided a cover for rebel exchange, I first examine the export agreements between the RCD and its trading partners. If state administrations provided channels to legitimize exchange, this should be reflected in these agreements. These written agreements, or contracts, meet two key conditions: (1) they authorize economic transactions with rebels, and (2) they are tailored to a specific trading partner, whether an individual or firm. Appendix A provides a redacted sample. I obtained 126 export agreements, described in Table 2. Most authorize trade in lucrative tins that were mainstays of war (coltan and cassiterite, N = 68).Footnote 63 The second most frequent resource chain was diamonds (N = 36). Others authorize trade in gold, general mining, and products like timber and coffee. The RCD's Department of Finance or Department of Land, Mines and Energy issued most agreements.

Table 2. RCD economic regulations

Note: Some export agreements are issued for multiple resources, resulting in a sum by resource type larger than the total number

The data are limited, and I cannot be certain of the full universe of agreements. However, because I obtained data on conditions of unrestricted access, I can be relatively confident that the sample is not systematically biased. Since half the firms sampled fell under UN investigation for illicit trade, it is credible that this procedure captures the real workings of conflict markets.

To determine how extensively rebels built legal veneers into cross-border trade, I examine export agreements for references to state legitimation across three indicators: references to national legislation, requirements that firms pass payments or goods through state agencies, and references to the Mining Code or Investment Code. Indicators derive from a separate set of central government contracts that provide a benchmark of comparison.

Table 3 presents results. Of the 126 agreements surveyed, 86.5 percent cite official legislation. Many preface their terms with references to state laws, like the following clause: “Given the ordinance no 67-416 of 23 September 1967 regarding Mining Regulations … [Firm] agrees to [X price for Y amount of Z resource].” Agreements require firms to respect national protocols, including a generic clause reading: “Firm [X] is designated as a [resource] buyer, conforming to the legislation in effect in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.” In addition, 82 percent of agreements require firms to make payments through state agencies or obtain bureaucratic licenses and certificates.

Table 3. “Legality” in rebel export agreements

These attributes created a legitimate gloss to rebel exchange. Excerpts illustrate this veneer in fuller detail. A first is from an agreement with Thai timber exporter “D”:

[Firm “D”] commits to submit all import and export activities to the verification procedures of the Congolese Office of Control (OCC) … The State guarantees … all indemnities of exportations due to foreigners, as stipulated by Article 5 of the Investment Code. Any disputes on the interpretation or application of this statute will be submitted to the arbitration procedure provided in Articles 159 to 174 of the Civil Procedure Code.

Comparing this excerpt with a second export agreement in different resources—tins and gold—with South African Firm “E” illustrates the regularity of the official image: “with the support of the OFIDA customs bureau, tax collectors, and DGRAD, [Firm “E”] commits to pay the fiscal duties relevant to this file on the fifteenth of every month.”

Standardized bureaucratic formulations provided a nothing-to-see-here impression that cloaked the illicit nature of transactions. These protocols required firms to pass through the same bureaus as before rebellion, giving the outward appearance of legal compliance.

A Tailored Strategy?

Was this legal veneer tailored to transnational markets? After all, the RCD took over much of the preexisting bureaucracy. Citing official procedures could reflect this institutional environment broadly, rather than an explicit attempt to overcome legal barriers in transnational exchange. To determine whether rebels pursued a strategy of legal appropriation, I examine whether rebels used a legal veneer on external commerce at a significantly higher rate than in domestic markets.

To do so, I exploit a standardized mechanism and form that rebels used to issue economic regulations. The RCD used a standard arrêté form to issue business agreements in export markets and used this same form to issue agreements and regulations for sales in domestic markets. Domestic markets include sectors like petrol, cigarettes, and household goods that were destined for local consumption. This sample is the best available control group for comparison. It enables me to assess rebel decision making under relatively stable conditions. It holds constant the RCD ministries (Department of Finance or Department of Mines) and procedures rebels used to issue regulations. Online Appendix B depicts forms from these subsamples side-by-side to illustrate this procedural similarity.

I develop a legality index to measure the degree to which the RCD constructed a legal front and compare the difference in means between these two samples. Findings that the exports sample held significantly higher levels of legality than the domestic sample would constitute evidence that rebels tailored this veneer to legitimize trade. Online Appendix B provides the full coding rules. Points are allocated per state law cited and subtracted for references to rebel bodies (e.g., internal ministries, the military wing, the “war effort”) or rebel rule codes. Such references include statements like “In light of the Interior Regulations of the Rally for Congolese Democracy.” Points are earned for invoking official legislation and official markers like the “public treasury” or “the State.” Scores assigned in this way should measure the level of legal veneers infused into rebel dealings.

Results demonstrate that RCD regulations for external markets held a higher level of legality (3.98) than for domestic markets (-0.72). A two-group comparison t-test placed the difference in means as significant at the 99 percent confidence level (4.70, T = 10.7, p < 0.001). Findings suggest that rebels tailored veneers of legality to export markets.

Firms: Obtaining Legal Cover

The RCD wrote legality into its trade, but did state agencies become channels for illicit markets in practice? To determine whether firms routed revenue to rebels through state intermediaries, I crosscheck the set of export agreements with firms’ payment records. These include tax slips, receipts, bureaucratic licenses, export certifications, and written correspondence. This step uses different data sources to cross-verify legal veneers with the actual use of state institutions.

Figure 2 depicts examples of these records. (See online Appendix C for further examples of parallel certification.) Technically counterfeit, these documents are visually indistinct from authentic documents issued by the same agencies in government-held territory. Bedecked with official letterhead and stamps, the records illustrate legal cover in practice. These forms and receipts passed money to rebel-controlled accounts, but make no reference to rebels.

Figure 2. Sample trafficking documents: false certification issued by rebel-held state bureaus

I found evidence that 77 percent of firms routed payments to rebels through state channels. Because this measure relies on recovering first-hand records of clandestine deals, it represents a minimum estimate. Moreover, firms worked with more state agencies than rebels required. Agreements obliged firms to report or pay taxes to an average of one agency. Actual payment records demonstrate that firms interacted with an average of 3.4 agencies. This finding supports the argument that firms held independent incentives to exploit legal channels.

Mechanisms: Cost and Ambiguity

These measures reveal three core insights. First, the RCD widely used national codes and procedures to validate trade. Second, rebels tailored this cover to export markets. Third, state agencies passed money and resources between rebels and most trading partners. This section examines mechanisms underlying this strategy.

Demands for Legal Validation

Global norms for legal validation created financial costs for rebels. Firms passed these costs to rebels through their buying practices. RCD records show that firms avoided deals that could be easily linked to rebels.

Firms changed their purchasing behavior in Congo based on the availability of legal certification. Sovereign states—including Congo's central government and regional countries—made this status available to buyers by laundering conflict-affected resources through internal ministries.Footnote 64 When war broke out, rebels tried selling resources to buyers directly. In 1998, for instance, the RCD and Rwanda jointly looted a tin producer. Whereas Rwanda brought its share to Kigali and sold it to buyers as “clean,” the RCD managed to sell less than half its stocks.Footnote 65 Over the following year, the RCD sought out foreign firms to purchase diamonds. But the RCD Department of Mines found that firms preferred to purchase from Rwandan and Ugandan front companies and “refused to pay taxes” to rebels.Footnote 66 As a result, the RCD received only USD 230,000 of the USD 1.2 million it anticipated from diamond sales—nearly a million-dollar loss.Footnote 67 A juridical disadvantage came at a financial cost.

Firms also told rebels that their business depended on their international image. In 1999, Belgium diamond and gold firm “B” warned RCD leaders that “juridical insecurity … poses a difficulty” to exchange. To facilitate business, it advised rebels to “improve the image of the RCD on the international level.”Footnote 68 Likewise, arms trafficker Victor Bout refused to deal with rebels without “juridical cover.”Footnote 69 And as German Firm “C” explained to rebels, it wanted its tin mining “recognized in national and international conventions” in order to “leverage mining concessions to acquire capital investment from international banks.”Footnote 70

The RCD began a full-blown strategy of legal appropriation in mid-2000. Global penalties on firms created penalties for rebels, and rebels needed to keep state agencies minimally functional to satisfy buyers. For example, when the price of coltan skyrocketed, the RCD shifted course to route sales through a rebel front company.Footnote 71 Firms warned that removing bureaucratic intermediaries created “obstacles to the good commercial relations … with foreign partners all over the world, notably in Belgium, the United States, Britain, and [post-]Soviet states.”Footnote 72 Belgium Firm “F” wrote that the system “discourages partners from mineral production” and withdrew its business.Footnote 73 Without legal cover, the tin was labeled as “blood tantalum” by UN investigators. Upstream manufacturers sought “to dissociate themselves” from this label, and international demand for coltan fell.Footnote 74 Unable to sell resources, rebels reinstated bureaucrats. Rebels’ financial gain and firms’ legal cover in global markets were intertwined.

Supplying Parallel Legitimation

Was legal appropriation convincing in global markets? How did the central government and international regulators respond? Trade deals at national and international levels suggest this cover took effect by creating ambiguity in who wielded state authority.

Congo's central government is prototypical of weak states that rely on external recognition for financial and military survival.Footnote 75 Kinshasa used recognition to authorize mineral exploitation throughout war, giving its front companies names like “Operation Sovereign Legitimacy” to invoke its legal status.Footnote 76 When rebels coopted state agencies to facilitate trade, some firms claimed that Kinshasa simply turned a blind eye.Footnote 77 Yet key trade deals indicate this tactic created new competitions over state legitimation.

Illustrating this competition, Kinshasa recruited a foreign firm to reopen a tin parastatal in RCD territory. Central rulers use their recognized status to build economic and security influence over rebels.Footnote 78 The expectation is that a juridical monopoly will exclude rivals from trade benefits, but rebels recruited a different firm, German Firm “C” to relaunch the same parastatal. The RCD licensed the firm “conforming with the mining legislation in effect in Democratic Republic of Congo.” Firm “C” passed payments to the RCD via state bureaus, which, rebels stipulated, “will provide you all the necessary exportation documents.”Footnote 79 Firm “C” took over the parastatal, claiming its actions were “approved by the Congolese State.”Footnote 80 Kinshasa challenged these actions before Interpol and foreign courts, but the case was hung up in a legal battle that outlasted war.Footnote 81 Meanwhile, rebels blocked Kinshasa's partner from operating.

In other cases, firms that Kinshasa rejected turned to rebel-held state agencies to obtain certification. For example, when Kinshasa denied Thai Firm “D” a license to harvest timber, the firm approached rebels. Firm “D” obtained the same licenses from RCD-controlled bureaucrats that it would have received in the capital. It used these certificates to export timber in defiance of Kinshasa, making payments to bureaus that had been hijacked by rebels. International norms recognized Kinshasa's monopoly over juridical statehood. Yet, rebels supplied a parallel source of state legitimation that the capital did not fully control.

At the international level, UN panels, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and powerful state courts investigated war economies. Their goal was to penalize actors operating in “violation of the sovereignty” of Congo by determining whether trade complied with the “existing regulatory framework.”Footnote 82 But passing illicit transactions through recognized institutions had shifted the effect of these rules.

Firms invoked official regulations in legal defense. For instance, when Kinshasa called Interpol to requisition German Firm “C's” tin, Firm “C” demonstrated it “had all the documents justifying our presence and activities at the mine.”Footnote 83 Likewise, when British Firm “G” was questioned before the UK parliament, it cited payments to state agencies as proof of legal validation: “We were going and getting the documents signed and getting the documents obtained.”Footnote 84 In the agricultural sector, Firm “H” told an NGO certifying supply chains, “I pay my taxes to the same people I've always paid taxes to, in the office in the middle of town, but the management changes occasionally.”Footnote 85

Exploiting official rules created ambiguity in what constituted legal practice. Mahoney and Thelen describe this pathway of change that occurs when “[opportunists] redeploy these rules in ways unanticipated by their designers.”Footnote 86 In this context, applying standard rules created dilemmas for regulators. For instance, the UN Panel verified legal compliance by determining whether firms paid state agencies. Payment records showed that “forms indicate issuance from a government organization, complete with the required stamps and signatures.”Footnote 87 The expert panel blacklisted RCD trading partners, but reversed several sanctions recommendations when it could not prove firms acted illegally. It described this dilemma with Thai Firm “D”—the timber exporter that Kinshasa had rejected: “[Firm D] complied with all the regulations in effect. It currently pays its taxes at the same bank as it did before the area came under rebel control. It also deals with the same customs officials as it did before the rebels took control … a bimonthly check is conducted by the local Congolese authorities.” In a similar way, NGO certifiers declared Firm “H’” legal, while Firm “C” was never charged before German courts. By working through official rules, firms and rebels exploited the system to expand what could pass as legal—or at least what provided plausible deniability.

Implications

International System, Sovereignty, and State Institutions

These findings suggest a more complex relationship between sovereignty, institutions, and violence. The international system rests on the fiction of independent juridical units with full recognition across national territory.Footnote 88 And yet, military control can fragment control over the state's legal status. Rebels that market legality, and firms that recognize rebels’ authority to deal in the name of the state, undermine the central government's ability to use a legal monopoly as a source of power. For international relations scholars, findings clarify how states mediate between the international system and domestic markets. States are recognized on the international scale, but central governments hold no monopoly over how this status is used.

These findings demonstrate new pathways of state building and fragmentation. Paradoxically, nonstate actors have incentives to sustain bureaucratic agencies that central state rulers may abandon. Seemingly defunct taxation bureaus and customs authorities offer valuable legitimation resources for actors at a juridical disadvantage. So long as norms value states, and international regimes validate economic transactions with the stamp of the state, violent actors have incentives to exploit the institutions that provide this status. These incentives reveal unexamined mechanisms that sustain state institutions, but in ways that fragment control over the state apparatus.

These new findings invite research into the parallel uses of state legitimation. More work is needed to unpack the layers of the state to understand who uses legal authority, and for what ends, on the international stage. This agenda would entail a variety of research questions: How do central governments adapt financial strategies to these parallel uses of statehood? Does the ability to exploit legal affiliation behind frontlines reduce rebel incentives to capture the national capital to obtain this status?Footnote 89 Research in this trajectory would examine how bureaucrats’ incentives may differ from the national government's, and how their survival strategies during war may build out the power of nonstate actors.

Rebel Governance Research and Wartime Order

Institutions play more varied roles for rebels than previously known. Alongside domestic functions of institutions to recruit, tax, and socialize noncombatants, rebels also need the right channels to connect to the international environment. These channels go beyond mimicking executives or setting sights on the national capital. They also seek distinct benefits from rank-and-file bureaucrats who provide a recognized status.Footnote 90 Researchers have shown that back-end accountants and bureaucratic writing are needed to organize violence.Footnote 91 Official state bureaucrats who can provide the stamp of legality are another important support network.

Wartime connections between rebels and bureaucrats hold potentially lasting effects for embedding violent financing within state institutions. Future research would fruitfully examine the postconflict legacies for economic networks and institutions. (How) do rebels use state institutions to sustain themselves financially over time? How does this shape the negotiating tools and competitions in the domestic power balance between central state officials and rebels?

These findings also suggest new pathways of how wartime revenue needs might build order. Scholars often cast external partners and lucrative resources as undercutting rebels’ incentives to build institutions.Footnote 92 Yet firms seek to work through official institutions. This raises questions about other functions that institutions may play in wartime exchange: more than legal cover for profits, do institutions provide other guarantees, like predictable markets? Might firms prefer to work with rebels through institutions because preexisting rules and systems—however altered they may be—offer more predictable channels exchange than handshake deals? Scholars focus on rebel taxation of civilians as producing wartime institutions, but external relationships that gain from stable institutions may provide another driver of order.

Illicit Markets and Sanctions Regimes: Methods and Underlying Assumptions

A basic implication is that closer knowledge is needed about the varied ways that illicit financing moves through formal institutions. Money laundering and organized crime exploit the interstices of rule.Footnote 93 Institutionally, rebels face similar realities of navigating formal laws and markets, but these comparisons are unexplored and undertheorized.

Policy efforts to curb conflict financing have not kept pace. Existing UN, OECD, multi-stakeholder organizations, and corporate initiatives rely on an artificial boundary between rebels and states. The expectation is that heightened penalties for funding rebels will incentivize firms to pass through legitimate state channels. These policies designate transactions as legitimate if they follow official procedures—trade with rebels is, by definition, “against Government laws.”Footnote 94 But these boundaries are blurred in practice. Rebels and their trading partners can repurpose the tools that regulators use to establish the “facts.” This means firms may provide certification of seemingly legitimate payments while still financing rebels. Solutions must anticipate that laws and regulations will incentivize dynamic adaptations.

To account for cross-infiltration, policymakers must shift the focus on curbing violence from what institutions are used (state versus nonstate) to a closer understanding of the relationships that permeate and govern them.Footnote 95 Illicit economies may be much larger than realized if they run through the state but for the agendas of armed groups.Footnote 96 Second, policies must adjust expectations of how rebels navigate a global environment. Rebels are more adept at maneuvering the expectations of policymakers and scholars when it comes to accessing the state and the international system. Methodologically, it calls for closer attention to the evidence and assumptions that shape understandings of conflict, and how these may also form part of rebels’ terrain of competition.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this research note is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818321000205>.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Elizabeth Wood, Stathis Kalyvas, William Reno, Paul Staniland, Hendrik Spruyt, Stephen Nelson, Kenneth Schultz, and three anonymous reviewers for excellent feedback on earlier versions of the paper. The paper benefited from support of the Harvard Academy for International Area Studies and the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs at Harvard University, with special thanks to Mariano Sanchez-Talanquer and David Szakonyi.

Funding

Fellowships from the Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Award, the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation, the Dispute Resolution Research Center at the Kellogg School of Management, and the Program on African Studies at Northwestern University supported data collection and analysis.