At least since the posthumous publication of Max Weber's essay Die Stadt in 1921, scholars have highlighted the medieval development of self-governing towns in the period between CE 1000 and 1300 as crucial for European patterns of state formation, including for the formation of the European multistate system.Footnote 1 By urban self-government, we mean government by a town council comprised of citizens who were chosen by at least parts of the citizenry.Footnote 2 In this research note, we present a new explanation that sheds light on the origins of this development in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Our account emphasizes how the collapse of royal power in ninth- and tenth-century West Francia opened a window for a bottom-up social coalition (the Cluniac or church reform movement), led by clergy and facilitated by new norms about ecclesiastical office holding, which provided an impetus for urban self-government.

Two bodies of theory currently dominate the literature on the development of urban self-government.Footnote 3 First, associated with the work of Stein Rokkan,Footnote 4 there is the notion that initial geographical and economic endowments allowed certain urban areas to grow, thereby triggering institutional changes that culminated in urban self-government.Footnote 5 The most recent example of this research is Abramson and Boix's sophisticated attempt to empirically demonstrate how the development of “parliamentary checks (in the form of city councils or territorial assemblies with stronger urban participation)” in Europe between 1200 and 1900 was endogenous to urban economic development, in itself largely dependent on a specific set of geographic factors.Footnote 6 Second, associated with the work of Charles Tilly,Footnote 7 there is the “bellicist” notion that warfare empowered urban groups who were well placed to wrest political autonomy from cash-strapped monarchs.Footnote 8 Here, the most recent example is Dincecco and Onorato's ambitious analysis of how warfare facilitated urban population growth and political self-government in Europe in the period between 1000 and 1799.Footnote 9

There are two problems with these explanations. First, other regions of Eurasia had much higher levels of urban economic development in CE 1000 or 1200 and were also regularly visited by warfare but did not develop anything similar to the self-government—in the form of autonomous city councils and territorial assemblies—that appeared in medieval Europe.Footnote 10 Second, the first wave of formalized self-government, in the form of autonomous town councils, began deep into the eleventh century,Footnote 11 and a form of de facto self-government seems to have been present in urban communities even earlier.Footnote 12 According to the data set we use in the empirical analysis, sixteen towns introduced autonomous town councils before CE 1100, and a total of 136 before CE 1200.Footnote 13 This was well before the urban growth that Boix and AbramsonFootnote 14 take as a point of departure and, according to historians working on medieval Europe, warfare also intensified around only CE 1200.Footnote 15

While early urban agglomeration and warfare after 1200 might help explain the later development of urban self-government (for instance, whether it came to have staying power and to which areas it ultimately spread), these factors cannot explain the initial emergence of autonomous town councils, which began almost one-and-a-half centuries earlier,Footnote 16 and they cannot explain why this political innovation occurred in the Latin West and not elsewhere.

However, there is a third explanation in the literature, which seems better placed to shed light on the origins of urban self-government. In a series of recent works, David Stasavage has proposed that the emergence of autonomous towns ultimately arises from state weakness.Footnote 17 Stasavage's explanation is premised on a large body of historical research which has documented how the weakening of royal power in particularly the western and central parts of the former Carolingian Empire in the ninth and tenth centuries decentralized and privatized public authority structures.Footnote 18 There is an intuitive plausibility to the notion that this weakening of top-down authority paved the way for urban self-government from below. As historian Chris Wickham describes, the collapse of public power in West Francia left a “cellular structure for politics,” with local lordships and urban and rural communities making up cells of power, “which became more formalized in the context of royal weakness.” Footnote 19

However, while the sequence fits in the European case, “there had been plenty of periods of weak or chaotic rule in earlier centuries without autonomous lordship developing,”Footnote 20 and there are many other regions of the world where weak public authority did not bring about anything similar to the self-governing towns of medieval Europe.Footnote 21 In other words, and as Stasavage concedes, the recent work on state collapse has done little to show precisely how and why this process paved the way for the initial emergence of autonomous town councils after CE 1000, including why the idea arose in the first place.Footnote 22

Our new explanation addresses these gaps. We argue that the key to understanding both the advent of urban self-government and its timing in the eleventh and twelfth centuries is to be found in institutional and ideational developments within the medieval Catholic Church, which were themselves enabled by the tenth-century state collapse. In other words, we combine Stasavage's focus on state collapse with a recent focus on how the Catholic Church affected the development of political institutions of self-government in medieval Europe.Footnote 23

We take as a starting point the observation, made by several generations of historians, that the weakening of royal power in West Francia allowed a bottom-up church reform movement—known as the Cluniac movement—to emerge in the late tenth century and spread the notion of the freedom of monastic and other ecclesiastical institutions from secular influence in the eleventh century.Footnote 24 The Cluniac reform movement was based on a new social coalition between clergy in West Francia and popular movements, and its program found a large resonance among townsmen. We argue that the reform movement—both before and after it had given rise to the Papal or Gregorian movement centered on RomeFootnote 25—helped foster the associationalism that led to urban self-government in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. It did so by incentivizing townsmen supporting church reform to take political power to implement the reform program in the face of opposition from, for example, lord-bishops who were seen as simoniac and lax on clerical celibacy. As one historian puts it, the reform movement thereby created a “general belief among townsfolk that self-government was essential to ensuring a peaceful, godly community.”Footnote 26

In the mold of Hendrik Spruyt's seminal work on European state formation,Footnote 27 we thus provide an explanation for the origins of urban self-government that is more contingent and actor-driven than the long-run structural explanations emphasizing endowments or warfare and that appreciates ideational factors. Our explanation can be situated in a new literature that argues we need to integrate the study of religion into the study of state formation and regime change.Footnote 28 Moreover, it follows in the footsteps of four decades’ of historical literature that has pushed the crucial period of European state formation back to the tenth, eleventh, and twelfth centuries and has emphasized the importance of the medieval Catholic Church.Footnote 29

We first set the Cluniac reform movement in the context of the ninth- and tenth-century breakdown of public order, develop the argument about how it fostered urban associationalism and self-government, and use two cases to illustrate these dynamics. Next, we apply the argument empirically, using an existing data set covering 643 towns in the period from 800 to 1800 combined with new geocoded data on the location of 270 Cluniac monasteries. In a second step, we use distance from Cluny—the movement's place of origin—to instrument for urban proximity to Cluniac monasteries. We provide empirical evidence that the Cluniac reform movement had a strong positive effect on the initial emergence of autonomous town councils (before CE 1200).

The Cluniac Reform Movement

The collapse of royal power in the ninth and tenth centuries meant that ecclesiastical institutions —hitherto ruled by kings who had inherited a vigorous tradition of public authority from RomeFootnote 30—came to be beholden to local lords rather than to royal power. In the 150 years after the death of Charlemagne in 814, church lands, tithes, and offices thus progressively came under the control of lay lords,Footnote 31 especially in the western part of the former Carolingian realm, West Francia.Footnote 32

This lay encroachment of ecclesiastical institutions sparked a reaction as clergy in West Francia attempted to escape from the control of local lay authorities and to fill the void left by royal authority's enfeeblement.Footnote 33 The key principle of this tenth- and eleventh-century reform movement was the church's freedom from lay influence.Footnote 34 Monasteries, in particular, should be free to pursue the vita religiosa in a way that was true to church tradition and scripture. Ecclesiastical independence from lay control was seen as a necessary shield against practices such as simony (selling church offices) and to enforce clerical celibacy.Footnote 35

Historians associate this bottom-up reform movement with the abbey of Cluny in Bourgogne, which was the main institution spreading the new asceticism and the practices of ecclesiastical self-government.Footnote 36 In a deliberate attempt to avoid the lay encroachment of the day, the foundation charter of Cluny, which Duke William I of Aquitaine signed in Bourges on 11 September 910, stipulated that the monastery was not to be beholden to any local authorities (lay or ecclesiastical) but subject only to the pope,Footnote 37 and that the monks would henceforth elect the abbot.Footnote 38

Cluny's abbots obtained confirmation of their independence from successive popes, beginning with John XI in 931.Footnote 39 The Cluniac reform movement began in earnest in the late tenth century. By the early eleventh century, Cluniacs had created the first international organization of priories which answered to the mother abbey at Cluny rather than to local lords or bishops.Footnote 40 The Cluniac heydays were during the fifty-four-year-long abbacy of Odilo, which lasted until 1049, and the ensuing sixty-year-long abbacy of Hugh of Cluny (1049–1109).Footnote 41 The decentralized culture of monastic and conciliar independence created by the Cluniacs “spread through the clergy in the generation before the Investiture Conflict.”Footnote 42

The “Peace of God” movement of tenth- and eleventh-century Languedoc illustrates how state collapse enabled the Cluniac reform movement. The peace movement was part of the wider reform movement, directed by bishops in West Francia and propagandized by the Cluniacs.Footnote 43 In the early Middle Ages, and under the Carolingians in particular, peace had been a royal prerogative.Footnote 44 This is reflected in the timing of the peace councils, which began a few years after the last Carolingian king of West Francia was replaced by Hugh Capet in 987. The Capetians had very little power outside their royal lands, which were concentrated in the Isle-de-France,Footnote 45 and the Peace of God councils were “a response to social collapse, in which monasteries led the poor in concerted defense against the anarchic conduct” of predatory lay lords.Footnote 46 Besides establishing oath-sworn public peace where the royal peace had faltered, the peace councils spread the Cluniac reform program's three core tenets consisting of prohibition of clerical marriage, simony, and lay investiture.Footnote 47

This ambitious attempt by the clergy of southern France to spread the reform program via a bottom-up alliance with popular movements came to engulf most of the parts of the Latin West where royal power had buckled: “The force of popular indignation under religious leadership was most dramatically harnessed in the cause of ecclesiastical reform in northern and central Italy and southwestern France from the second half of the tenth century onwards, spreading to northwestern France by the end of the eleventh century.”Footnote 48 On the contrary, the Cluniac reform program—and the Peace of God councils (see Table A1 in the online appendix)—initially had little traction in the Capetian royal demesne, the strong English and Sicilian kingdoms, and the strong Roman Empire of the German Nation; “in short, wherever the ecclesiastical hierarchy could expect to call upon the support of well established secular authority.”Footnote 49

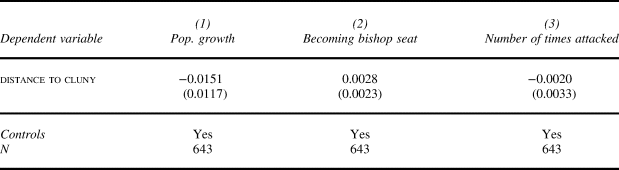

This spatial pattern is clearly illustrated by the way the Cluniac order spread. The locality of Cluny can be seen on map (a) in Figure 1. As illustrated in the other maps (b, c, d, and e), the subsequent spread of Cluniac monasteries happened in concentric circles from Cluny.Footnote 50 Many of the monasteries that adopted the Cluniac ideals had personal ties to Cluniac abbots nearby. In some cases, their leadership was even taken over by the abbot of Cluny or by monks brought in from Cluny.Footnote 51 This meant that Cluniac practices and ideas spread from neighboring monastery to neighboring monastery.Footnote 52

Figure 1. The spread of Cluniac monasteries

Church Reform, Urban Associationalism, and Self-Government

As we pointed out, laymen were an integral part of the Cluniac reform coalition, and popular support was necessary to force the reform program on “secular magnates who failed to surrender lands and tithes to the church, and on bishops and clergy who failed to acknowledge or implement the new prohibitions.”Footnote 53

This reliance on popular support meant that the reform movement had secular political repercussions.Footnote 54 In the eleventh century, popular urban movements began championing the ideals of the Cluniac reformers, and townsmen in many urban sites founded oath-sworn associations of believers that attempted to reform their local churches. Their most prominent demand was that the community of believers—rather than lay lords or monarchs—elect the city's bishop.Footnote 55 In this way, the bottom-up Cluniac reform movement stimulated a similar bottom-up associationalism among townsmen, especially in towns that were the seat of bishops, nested in expectations about responsible clerical office holding that could be harnessed by urban movements in their campaigns for self-government.

Indeed, urban self-government was necessary to carry through the reform program in the face of opposition from especially unreformed lord-bishops, who held both lay and religious power in the towns they ruled (or lay lords who protected unreformed clergy in towns they ruled). Townsmen disgusted with clerical corruption in these episcopal towns had little alternative to demanding political power, which would enable them to force out simoniac bishops and enforce chastity on the local clergy (see the Cambrai and Milan examples that follow). The Cluniac reforms thus gave an impetus to “civic emancipation through its sustained critique of allegedly corrupt and immoral senior clergy and the secular lords accused of protecting them.”Footnote 56

The Peace of God movement also illustrates this ecclesiastical-urban nexus. We have already described how the very idea of the peace councils was to use popular action to push the Cluniac reform program. British historian Susan Reynolds more specifically observes that some of the earliest attempts to create urban communes in France—for example, Le Mans in 1070, Saint-Quentin in 1081, Beauvais in 1099, and Noyon in 1108—seem to have been outgrowths of the peace movement. Townsmen fighting for self-government “probably thought of themselves as the kind of association for the defence of peace and punishment of peace-breakers which the clergy of France had been encouraging for nearly a century.”Footnote 57

The Cluniac reform movement was succeeded by—and helped foster—the eleventh and twelfth-century “Gregorian” or papal reform movement,Footnote 58 named after its most radical protagonist Pope Gregory VII.Footnote 59 Gregory expanded the Cluniac reform program in several ways, including by arguing that lay investiture “was as much an infringement of the liberty of the Church as simony was.”Footnote 60 This further increased popular pressure on unreformed clergy and the consequent urban associationalism. In the 1070s, Gregory VII directly encouraged lay sanctions against unreformed clergy, and unreformed bishops in particular, instructing the laity to use local assemblies to attack simony (now encompassing lay investiture) and clerical unchastity.Footnote 61 Especially in the places where Cluniac influence already ran high, there was a lot of resonance as townsmen heeded Gregory's call.Footnote 62

Two eleventh-century examples illustrate the reform movement's urban political repercussions, the first in a longer-run perspective (Milan), and the second with respect to the specific transition to urban self-government (Cambrai). In the eleventh century, Milan was politically dominated by a coalition between the representatives of the German emperors and successive Milanese archbishops, who were also known to buy and sell their high office. The Cluniac reform program had a large appeal among the industrious Milanese townsmen, who rallied against their wayward clergy in general and their archbishop in particular.Footnote 63 As early as 1042, mercantile groups in Milan succeeded in expelling the simoniac Archbishop Aribert, who managed to return in only 1044.

For the remainder of the century, Milanese townsmen would fight simony among the higher clergy in Milan and increasingly oppose lay influence on investiture, which was seen as the root of the evil practices. Beginning in the 1050s and growing in influence throughout the eleventh century, we find a popular movement in Milan—which spread to other north Italian cities—called Patarenes (patarini, “ragpickers”), who founded “sworn associations of the godly to provide a more moral and autonomous government.”Footnote 64 The effect was “a kind of lay strike against offending clergy,”Footnote 65 and by the mid-eleventh century the situation in Milan had become explosive: “the townsmen in a sworn commune or conspiracy opposed the again resident archbishop and his noble supporters, and the spectre of imperial intercession hovered in the wings.”Footnote 66

In fact, the outbreak of the “Investiture Conflict” between 1075 and 1122 owed to the resonance of the Cluniac reform project among the urban population of Milan. In 1072, the reform clergy and people of Milan once again renounced their archbishop, who they considered a simoniac because he had bought the office from his predecessor, and proceeded to elect a new one. Pope Alexander II supported the reform movement's candidate, whereas Emperor Henry IV stood by the old archbishop who was allied with German imperial power.Footnote 67 It was ultimately this conflict, still unresolved when Gregory VII became pope in 1073, that sparked the investiture conflict as Henry IV and Gregory, who had long been a staunch supporter of the Patarenes,Footnote 68 came into open conflict about who should appoint the archbishop of Milan.

Stasavage codes Milan as self-governing from 1097,Footnote 69 but as the case example shows, the roots of civic autonomy go much further back into the eleventh century and are inseparable from the Cluniac or church reform project. An example of how the reform movement's use of popular action to confront unreformed clergy caused the specific transition to urban self-government comes from the town of Cambrai in present-day northern France. In the 1070s, the bishop of Cambrai was a certain Gerard who had been invested by Emperor Henry IV, Pope Gregory VII's archenemy in the investiture conflict. This placed Gerard on the reform movement's blacklist of simoniac bishops. In 1076, the political situation in Cambrai erupted after a priest named Ramihrdus accused Gerard of being a simoniac, only to have Gerard's supporters burn him alive. Pope Gregory reacted with fury when he heard this, and Ramihrdus's followers kept up the pressure on what they saw as the unreformed clerical establishment of Cambrai.Footnote 70 A desperate Gerard traveled to Rome to plead his case, only to have Gregory refuse to meet him. The papal legate in Burgundy proved more accommodating and subsequently approved Gerard's episcopal election as canonical. However, “during the bishop's absence, workers and peasants had seized control of Cambrai. Declaring a commune, they swore never to have him back.”Footnote 71 Dutaillis records Cambrai as self-governing from 1076, and we see here a very clear illustration—virtually “fingerprint” proof—of how, deep into the eleventh century, the reform program encouraged popular groups to claim urban political autonomy as part of an attempt to correct unreformed clergy.Footnote 72 As Wilson summarizes this development, “attacks on simony and concubinage lent moral force to political demands for civic autonomy.”Footnote 73

While the reform program (centered on fighting simony, lay investiture, and clerical marriage or concubinage) continued to be papal policy in the following centuries, it gradually lost its popular dimension in the late twelfth century as the papal establishment changed course and increasingly distanced itself from the popular and communal sentiments with which the reformers had initially been allied.Footnote 74 The late twelfth century also more specifically marked the end of the great era of Cluny as the Cluniac order came to be seen by the clerical vanguard as ossified and as monastic influence within the Church increasingly fell to newer and more vibrant orders such as the Cistercians in the twelfth centuryFootnote 75 and the Dominicans and Franciscans in the thirteenth century.Footnote 76 But by then, the genie was out of the bottle, and after 1200, ideas and practices of urban self-government could spread without the assistance of the bottom-up pressure of the church reform movement that had first brought it into existence. For instance, urban self-government was further facilitated by the twelfth- and thirteen-century medieval “commercial revolution” and the “communal movement” that this created—a set of economic and political developments that are probably better explained by the endowment and bellicist literatures.Footnote 77

Data and Research Strategy

To assess the relationship between the Cluniac reform movement and urban self-government, we use a panel data set of 643 European towns and cities between 800 and 1800. We measure our dependent variable, self-government, with the commune variable from Bosker, Buringh, and van Zanden.Footnote 78 It is an indicator that is equal to 1 if a town has a local self-governing council in a given century, and 0 otherwise. The indicator is coded by searching for mentions of the occurrence of communal government or town councils in conjunction with the participation of at least part of the citizenry. Of the 643 towns in the data set, 383 attain self-government at some point. Figure 2 illustrates the geographical spread in the sample.

Figure 2. Towns in the sample

To capture the impact of the Cluniac reform movement, we have geocoded the location of 270 Cluniac monasteries that had been established by Abbot Hugh's death in 1109 (see Figure 1), using information in McCormick, Georganteli, and Moore.Footnote 79 Based on the location of medieval towns in the Bosker, Buringh, and van ZandenFootnote 80 data set, we use these data to construct a simple measure of urban vicinity to the Cluniac order—the distancei,t of a town to the nearest monastery in 100 kilometers. This serves as our main explanatory variable. This specification is based on prior research, which argues that the likelihood of ideas and organizational practices diffusing between source and receiver depends on, first, proximity, and second, frequency of interaction.Footnote 81 We argue that this applies a fortiori for medieval Europe, where travel was cumbersome.Footnote 82 For additional details on the empirical spread of urban self-government and our control variables, see the “Description of Data” section of the online appendix.

Empirical Analysis

As a first test of our propositions, we use a simple difference-in-difference design. We interact our indicator of proximity to Cluniac monasteries with a treatment period indicator that is equal to 1 after the tenth century because this was when the Cluniac campaign for ecclesiastical autonomy began. We expect towns that are closer to Cluniac monasteries to have a higher likelihood of attaining self-rule after this point in time. We include town and century fixed effects, which account for time-invariant confounders such as a Roman legacy, and for common time shocks like visitations of the plague. We also add controls for other known predictors of self-government from the literature.Footnote 83 Due to the number of fixed effects, all models are estimated using a linear probability model (LPM).

Table 1 shows that towns closer to Cluniac monasteries are more likely to be self-governing after the tenth century. According to model 1, increasing the distance to the nearest monastery by 100 kilometers is estimated to decrease the probability that a town has self-government by 4.4 percentage points. This estimate remains virtually unaffected by the inclusion of fixed effects and controls (models 2 and 3). One might worry that towns closer to Cluniac monasteries are also more likely to be open to new ideas and attract, for instance, bishops or universities. To ensure that this is not driving our results, model 4 allows each control variable a differential impact over time. Reassuringly, our estimate remains substantially unaltered.Footnote 84

Table 1. Difference-in-difference estimates

Notes: Standard errors clustered by town in parentheses. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

In Table A2 in the online appendix, we report results from four additional models that take possible unmeasured differences in institutional trends into account. First, we introduce modern country-specific time trends that allow each country a different institutional path. Second, based on a map of European kingdoms in CE 1000,Footnote 85 we control for realm-specific trends. Third, we allow for further flexibility by adding city-specific trends. Finally, we adopt a matching approach and use tenth-century developments to predict the likelihood that a town will later introduce a self-governing council.Footnote 86 This gives us a measure of variation in a town's propensity to adopt new institutions. We then allow towns with varying propensities a differential impact over time. Across all four models, our results remain robust.Footnote 87

IV Analysis

A potential objection against the presented results is that the founders of Cluniac monasteries might have selected locations where towns were more likely to introduce councils, for reasons not related to state collapse. To address this problem, we use distance from Cluny as an instrument for the proximity of towns to Cluniac monasteries.

At the time of foundation, Cluny was a back-of-beyond hamlet in the Black Valley, located far away from the centers of royal or lordly power of West Francia.Footnote 88 Based on the small size of Cluny before the founding of the monastery, we do not expect distance to Cluny to correlate with pre-movement urban regime change. Because no towns transition to self-government before the eleventh century, we cannot test this assumption directly. Instead, we check whether distance to Cluny is associated with tenth-century changes in other known correlates of urban self-government: urban population growth, episcopal presence, and warfare.Footnote 89

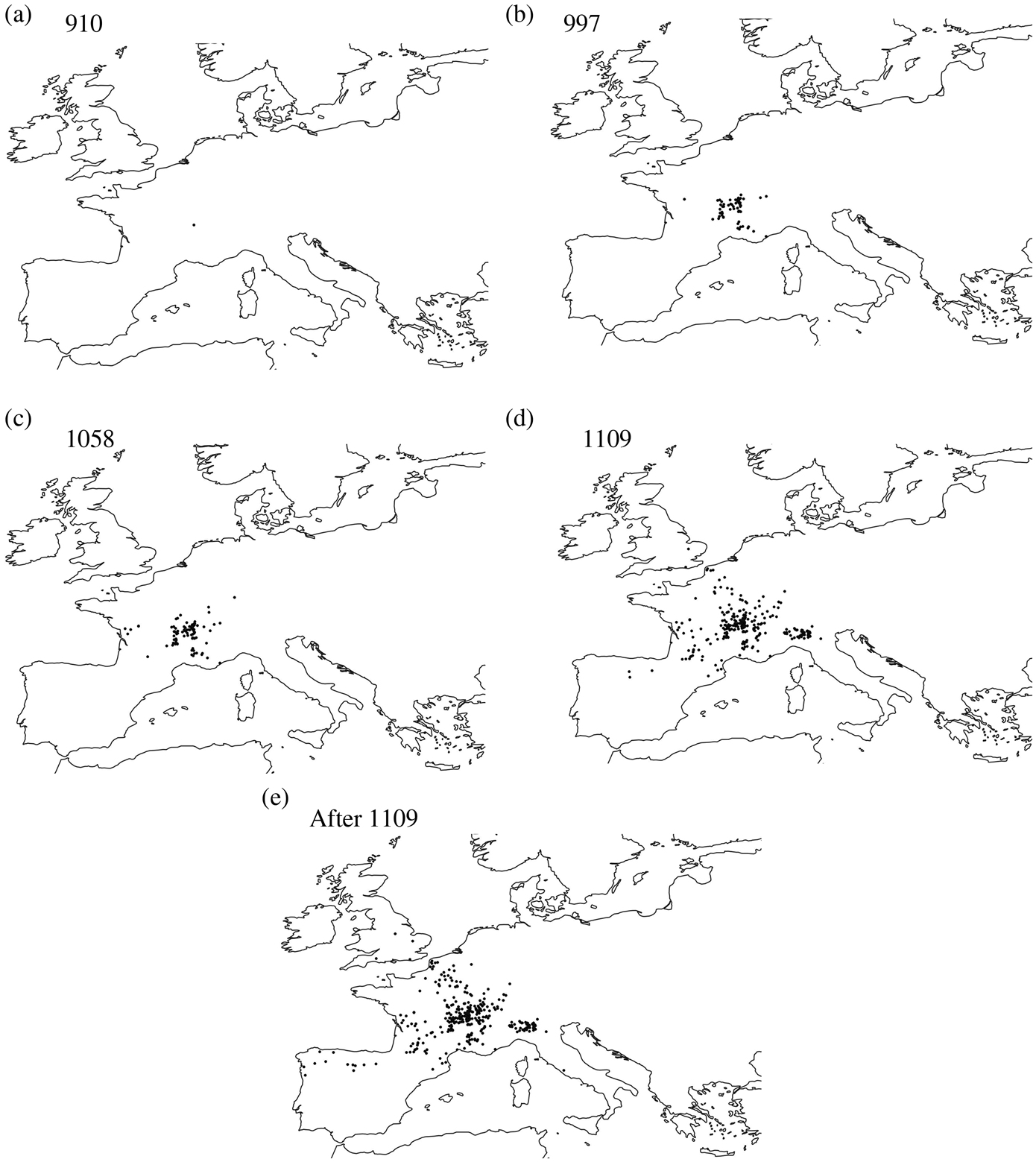

Models 1 to 3 in Table 2 document that there is no discernible relationship between distance to Cluny and tenth-century town development. These findings indicate that our instrument picks up variation in monastery location that is exogenous to other urban developments that predict regime change.

Table 2. Predicting tenth-century town development

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

We begin the IV analysis by examining the first-stage relationship between distance to Cluny and proximity to Cluniac monasteries. In all models, we control for longitude, latitude, ports, navigable rivers, being on a Roman road hub, elevation, terrain ruggedness, and soil quality.Footnote 90 Additional models also include measures of tenth-century town development: logged population size, being a capital or the seat of a bishop, having a university, and the number of times the town was attacked during the century.

To control for the “Carolingian Partition Hypothesis,”Footnote 91 and hence to test our argument that the effect of the ninth-century state collapse was realized via Cluniac influence, we add three dummy variables in all models: one measuring whether a town was part of the Eastern Frankish realm; one indicating if it was part of the Western Frankish realm; and one measuring if it was part of the Central Frankish realm).Footnote 92 The reference category contains towns that were never part of the Carolingian Empire.

The first-stage coefficients in models 1 to 4 in Table 3 confirm that distance to Cluny is a strong predictor of the founding of other Cluniac monasteries. Our outcome in the second stage of the IV analysis in models 1 and 2 is an indicator variable that is equal to 1 if self-government is established after the tenth century. According to model 1, a 100-kilometer increase in the distance to a Cluniac monastery reduces the likelihood that a town transitions to self-government by 5.2 percentage points. This likelihood decreases slightly to 4.8 percentage points when also controlling for tenth-century town developments in model 2. Models 3 and 4 show that the Cluniac movement primarily predicts the introduction of town councils between 1000 and 1200, that is, the initial emergence of urban self-government, which traditional theories emphasizing economic endowments and warfare cannot account for.

Table 3. IV estimates

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

To ensure that our results are not driven by measurement error in the commune variable from Bosker, Buringh, and van Zanden,Footnote 93 we employ an alternative indicator for urban self-government, namely the autonomy measure from Stasavage,Footnote 94 which covers 169 towns in Western Europe. As Table A3 in the online appendix illustrates, results from these models return similar estimates. We also consider an alternative specification using a setup similar to the one presented in Table 1, where the interaction between post-1000 and distance to a Cluniac monastery is instrumented with an interaction between post-1000 and distance to Cluny. These models, reported in Table A4 in the appendix, return estimates that are close to those presented in Table 1.

One may still worry that our instrument is associated with other determinants of institutional change than tenth-century urban developments, thus violating the exclusion restriction. We therefore conduct an additional falsification test. As we argued, the Cluniac reform movement ebbed out in the late twelfth century, only to be replaced by other factors spurring urban self-government such as the medieval commercial revolution. Thus, the Cluniac movement cannot be expected to explain urban institutional changes after this point in time. Beginning in the late thirteenth century and lasting into the fifteenth century, many towns saw revolts led by craft guild members that attempted to improve the inclusiveness of town councils. This late medieval development has been referred to as a “democratic revolution.”Footnote 95 In Table A5 in the online appendix, we show that the statistical relationship between distance to Cluny and guild revolts is negligible (and in the opposite direction).Footnote 96 These results lend additional credibility to our IV models.Footnote 97

Finally, it follows from our argument that the reform movement was especially important in sparking self-government where townsmen attempted to wrest power from unreformed lord-bishops, including Milan and Cambrai. To test this implication, we have rerun our main models interacting proximity to Cluniac monasteries with an indicator for being the seat of a bishop. As expected, we find that the effect of the reform movement is strongest in episcopal towns where secular and lay authority overlapped. Moreover, there is no interaction effects after the reform movement ebbed out in the late twelfth century. These results are shown in Table A6 in the online appendix. Finally, in the section “Ruling Out Alternative Explanations” in the online appendix, we provide additional evidence that the spread of university-educated administrators trained in Roman and canon law, economic development (including regional fairs), and political fragmentation are not driving our results.

Conclusion

There is a broad consensus that the medieval development of urban self-government is a crucial aspect of European state formation. In this research note, we have pursued a recent argument that an adequate explanation of medieval self-government's origins must take as a starting point the collapse of public power in the ninth and tenth centuries. More particularly, we have argued that this buckling of public authority, which was most pronounced in West Francia, was the backdrop of the tenth- and eleventh-century Cluniac reform movement and its offspring, the eleventh- and twelfth-century Gregorian reform movement. This Church reform movement fostered the ideals of ecclesiastical institutions’ freedom from secular control and responsible clerical office holding. These ideas and practices diffused widely, including to urban environments, where the Cluniac ideals of clerical chastity and the prohibition of simony and lay investiture had a large resonance, and where urban movements fighting for church reform could establish their own niche of autonomy in the new cellular structure of politics brought about by state collapse.

Using a difference-in-difference approach, we have demonstrated that towns located near Cluniac monasteries were more likely to be self-governing after the tenth century. This finding is corroborated by regressions that use distance from Cluny—the movement's place of origin—to instrument for proximity to Cluniac monasteries. Finally, we have shown that Cluniac influence was especially important in producing self-government in towns that were the seat of bishops, as we would expect if the reform movement were the main impetus behind urban political transitions before CE 1200.

By factoring in the Cluniac reforms, we can make sense of why state collapse produced urban self-government in medieval Europe. Our results provide a corrective to recent work by Abramson and BoixFootnote 98 because it indicates that the birth of European self-government was not endogenous to urban economic growth, even if this might have been the case for its later consolidation (after CE 1200). Instead, we argue that the initial emergence of urban self-government was the contingent result of bottom-up social realignments, facilitated by new norms and beliefs about ecclesiastical governance, which were made possible in the first place by the collapse of state power. The absence of a similar bottom-up religious reform movement, fighting for ecclesiastical autonomy and responsible office holding, probably explains why feeble public authority (or economic development and warfare) outside of the Latin West did not produce anything similar to the free towns of medieval Europe.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this research note may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SRXJLN>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this research note is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000284>.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to David Stasavage, Andrej Kokkonen, and Jacob Gerner Hariri for valuable comments. We also thank three excellent IO reviewers for their comments and suggestions, as well as the editor for helpful guidance and encouragement. All errors are our own.