Much of the literature on international mediation draws on a materialist perspective in which the material manipulation of the bargaining environment is understood to be the ticket to mediation success.Footnote 1 This capacity-based mediation perspective has guided most explanations for the effectiveness of different types of third parties, including African third parties’ effectiveness. African third parties have consistently been considered ineffective because third parties from outside Africa usually command far greater economic and military resources in comparison. For instance, Smock and Gregorian assert that the US and the former colonial powers seem to have a better record of successful mediation than either African organizations or African leaders, and further claim that the “very significant role of the United States and the European states seems related to the assets, resources, and leverage available to these powers.”Footnote 2 Similarly, Khadiagala claims that “by intervening with only limited tangible and material resources, African interveners have contributed to the widespread perception of being meddlers rather than mediators.”Footnote 3

While African third parties are relatively weak in terms of the material resources they command, a crucial source of mediation success is usually overlooked when discussing their effectiveness: third-party legitimacy. In this article I show that African third parties are effective in mediating civil wars in Africa because of a high degree of legitimacy flowing from the African solutions norm. This norm prescribes that mediation by African third parties in conflicts in Africa is preferable to mediation by non-African third parties.Footnote 4

In line with the African solutions norm, I demonstrate, based on unique data on international mediation in civil wars in Africa between 1960 and 2017, that African third parties are indeed more effective than non-African third parties in finding a negotiated solution to the conflict. Moreover, this negotiated solution is generally more likely to terminate the conflict. These findings contrast current materialist explanations on mediation success, since African third parties generally have less economic and military capabilities. If a mediator has legitimacy, it can continue to look for a mutually satisfactory outcome and try to pull the conflict parties toward compliance. But if a mediator loses legitimacy, the mediation effort is likely to fail even if a third party has a high degree of material resources.

I systematically compare African and non-African mediation efforts. Numerous studies have noted how there is a strong preference for African solutions to African conflicts within the African system of states, but the effectiveness of African and non-African third parties has been examined in only case studies.Footnote 5 These case studies typically conclude that African third parties are unsuccessful without comparing these efforts to the efforts of non-African third parties. This has led to biased conclusions, since failure is the “modal outcome” of international mediation processes.Footnote 6 Here I instead put forward a systematic analysis that compares the effectiveness of African and non-African third parties.

Existing studies on international mediation fail to point out the variance of African and non-African third parties and they do not offer a satisfying explanation for this variance either. African third parties have a comparative advantage in legitimacy-based mediation. Third-party legitimacy is the normative belief by the conflict parties that they should comply with the mediator, whereas capacity refers to the economic and military resources a third party possesses. In contrast to capacity-based mediation, which is based on coercion and the provision of some good, legitimacy-based mediation denotes power being conferred by the adversaries upon the mediator based on the adversaries’ normative belief that complying with the mediator is the right thing to do. African third parties have a high degree of legitimacy as a result of a common African commitment to the norm of African solutions to African challenges.Footnote 7 Since African leaders generally perceive that they are bound by norms related to the African solutions norm, African third parties possess a social status that, in turn, provides them with a high degree of legitimacy when mediating armed conflict in Africa.

Theorizing the role of legitimacy in international mediation processes, I deviate from much of the recent international mediation literature that ignores social structures when explaining mediation outcomes. I do not argue that material factors have no influence on mediation processes, neither do I deny that conflict parties are goal seeking and make decisions on the basis of costs-and-benefits analyses. But I do argue that ideational factors—and legitimacy in particular—greatly influence the prospects of mediation success. The role of legitimacy is almost completely overlooked in the literature on international mediation. This is striking since international mediation relies on the consent of the conflict parties. Much of mediation efforts’ success therefore depends on the relationship between the third party and the conflict parties. The social structure in which the third party and the conflict parties operate greatly determines the nature of this relationship. In sum, I aim to bring back ideational aspects, such as norms and legitimacy of the mediators, to the study of conflict resolution.

The Normative Context of International Mediation in Africa

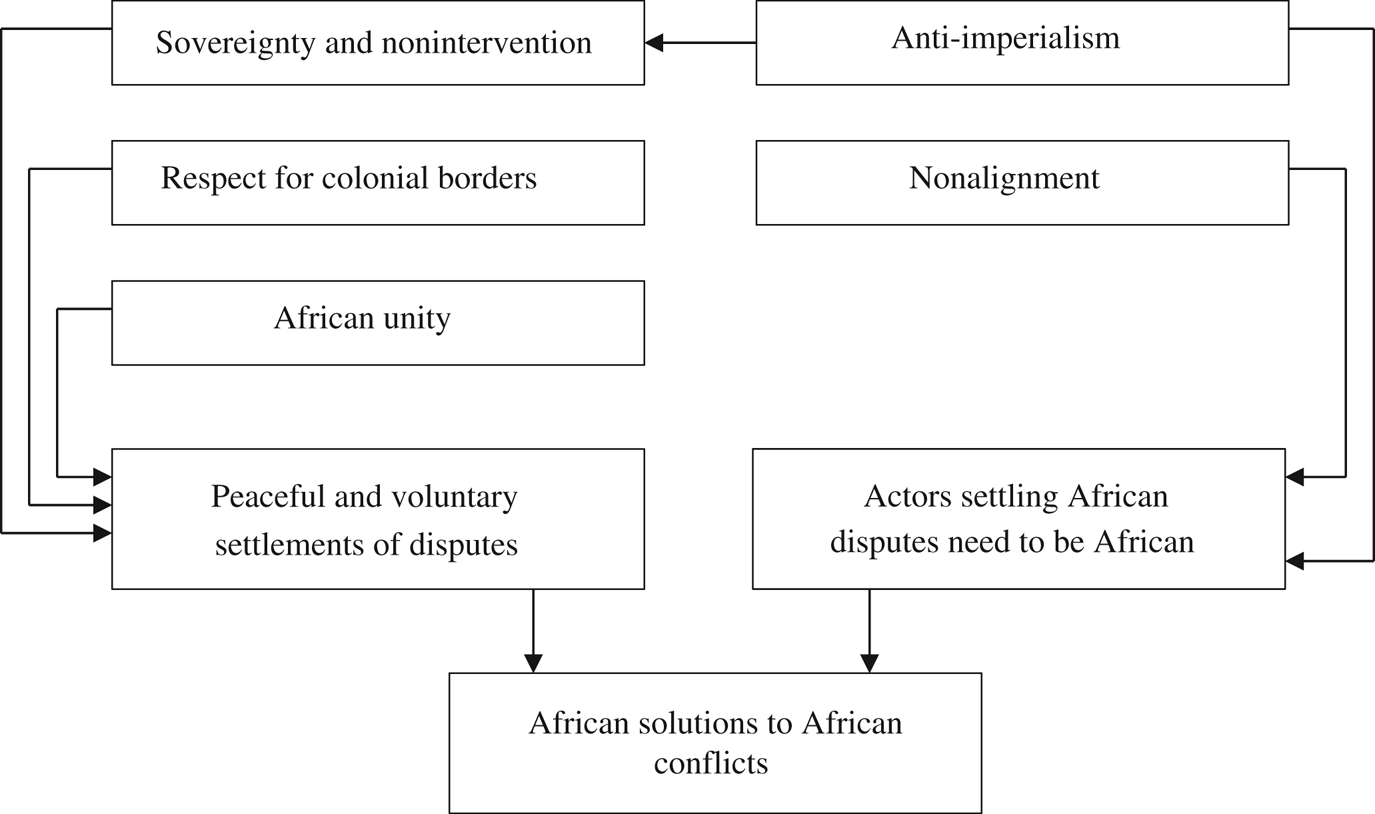

Simultaneously with the decolonization of most African states during the late 1950s and early 1960s, a normative environment emerged in which African decision makers formulated approaches on how to maintain peace and stability in the continent. Incentives to mitigate enmity in the international relations between states and within African states were the driving impetus behind the African security culture that emerged in this period. Figure 1 schematically summarizes this normative environment. What the norms listed have in common is that they all serve to maintain peace and stability in Africa. Besides the direct effects of an interest in mitigating enmity, some of the norms have been shaped by other norms. Figure 1 depicts this with an arrow running from one norm to another. The international security culture in African thus consists of a cluster of norms.

Figure 1. The emergence of Africa's normative peace and security environment

The norms of African unity, respect for colonial borders (uti possidetis), and sovereignty shaped the regulative element of the African solutions norm, namely the preference for peaceful and voluntary conflict resolution. The norms of anti-imperialism and nonalignment influenced the norm's constitutive element, namely the preference for these conflict-resolution efforts to be conducted by African actors.

Sovereignty, Uti Possidetis, and African Unity

When most African states gained their independence during the late 1950s and early 1960s, they had to operate in a threatening environment. The removal of external domination through decolonization created a large number of potential conflicts in Africa, since the borders had been created exogenously and therefore did not reflect ethnicity or community.Footnote 8 Involvement from states outside the African state system, such as former colonial powers, was seen as a threat.Footnote 9 To alleviate these threats as much as possible, African leaders emphasized their commitment to the sovereignty of the newly independent African states and to the maintenance of the territorial legacy of the colonial period, which came to be known as the uti possidetis principle.Footnote 10 While this territorial integrity norm initially emerged as a result of a need to regulate inter-African relations in postcolonial Africa, it was soon extended to also rule out territorial conflicts internal to individual states.Footnote 11 Another norm that was meant to serve the maintenance of peace and stability was African unity. Clapham notes that the sentiment surrounding African unity went beyond the merely rhetorical level, since it imposed on African leaders a moral obligation to act in harmony.Footnote 12

The norms of sovereignty, uti possidetis, and African unity explain why Africa has experienced relatively few interstate armed conflicts and the interstate armed conflicts that did occur generated significant disapproval. Another indication of these norms’ robustness is that the official recognition of rebel movements has been extremely rare in Africa and states that engage in the covert support of rebel movements are usually heavily criticized.Footnote 13

Anti-Imperialism and Nonalignment

Besides a need to regulate international relations between African states, leaders deemed it necessary to shield themselves from extra-African forces as a way to maintain peace and stability. Anticolonialism can therefore be understood as a strategy to strengthen the autonomy of the newly independent states.Footnote 14 Similarly, anti-imperialism was linked to sovereignty, since as long as African leaders could remain united in their commitment to the sovereignty norm they could more effectively shield themselves from negative pressure from non-African powers.Footnote 15Figure 1 depicts this relationship by the arrow running from “Anti-imperialism” to “Sovereignty.” The anti-imperialism norm is reflected in a passage in the preamble to the charter of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) that expresses the OAU member states’ determination “to safeguard and consolidate the hard-won independence as well as the sovereignty and territorial integrity of our states, and to fight against neo-colonialism in all its forms.”Footnote 16

Peaceful Settlement of Disputes

It follows from the OAU charter that African leaders anticipated that armed conflicts could not always be prevented. Article III of the charter specifically affirms the adherence to the principle of “peaceful settlement of disputes by negotiation, mediation, conciliation or arbitration.” This reflects the regulative element of the African solutions norm, since it emphasizes peaceful settlement of disputes as the appropriate modus operandi to mitigate armed conflict in Africa. Clapham explains that the idea of being African resulted in a perception among African rulers in one part of the continent that they had an obligation to those in another part of the continent.Footnote 17 The arrow running from “African unity” to “Peaceful and voluntary settlement of disputes” in Figure 1 depicts this relationship.

Despite the commitment among African states to resolve armed conflicts, African third parties have generally remained committed to the sovereignty of African states. Amoo and Zartman observe in this regard that the principle of respect for the sovereignty of other African states provided the basis for searching for a mediated solution.Footnote 18 The arrows running from “Sovereignty” and “uti possidetis” to “Peaceful and voluntary settlement of disputes” in Figure 1 depicts how a commitment to sovereignty shaped a preference for peaceful conflict resolution based on the consent of the conflict parties.

Many African states have remained suspicious of nonvoluntary intervention in the internal affairs of other African states. The uneven internalization among African states of the responsibility-to-protect norm reflects this suspicion.Footnote 19 This is illustrated by the lack of intervention in the conflict in Darfur and the African resistance against the military intervention in Libya.Footnote 20

Actors Settling African Disputes Need to be African

The anti-imperialism and nonalignment norms reflect how, during the Cold War, African actors had incentives for conflict-resolution efforts to be conducted by African actors. A general commitment to these norms reduced the likelihood that non-African actors would turn African conflicts into issues of Cold War confrontation.Footnote 21 An early example of the desire to prevent non-African involvement is a resolution adopted at the end of an extraordinary OAU meeting of the council of ministers on the Algerian–Moroccan border dispute of 1963, which considered “the imperative need of settling all differences between African states by peaceful means and within a strictly African framework.”Footnote 22

The international community's perceived reluctance to assist in resolving conflicts in what has been described as Africa's turbulent 1990s, including the Rwandan genocide, strengthened the perception that Africa had to control its own affairs.Footnote 23

Capacity-Based and Legitimacy-Based Explanations of Mediation Success

Since materialist studies on mediation ignore ideational factors and social structures, these studies do not consider how Africa's normative environment provides African third parties with a higher degree of legitimacy than non-African third parties. Hence, after having discussed the capacity-based perspective of mediation success, I show that the legitimacy-based perspective supplements prevailing materialist and rationalist approaches to mediation success.

Capacity-Based Mediation

In one of the first comparative case studies on international conflict resolution in Africa, Zartman argues that a mediator needs to materially manipulate the conflict parties through threats and inducements to mediate effectively.Footnote 24 From this perspective, mediation success is simply the product of the use of economic and military capabilities to move the conflict parties from fighting to negotiating an end to the conflict. I refer to this way of understanding mediation success as a capacity-based perspective.

A large majority of subsequent studies on mediation have followed this capacity-based perspective. For instance, Stedman argues that the economic and military resources of the UK as well its colonial ties with Zimbabwe were instrumental in putting pressure on the conflict parties, which ultimately led to the conclusion of a negotiated settlement.Footnote 25 Similarly, Rothchild argues that third parties providing material incentives to conflict parties can move them toward resolving the conflict. Rothchild claims that mediators with “muscle” can move the peace process ahead through “a combination of pressures, incentives, enforcement, and guarantees.”Footnote 26 More recently, Sisk presents qualitative evidence that powerful third parties with plentiful resources at their disposal are more likely to succeed than weak or poor ones. According to Sisk, powerful mediation is often the only viable option to resolve civil wars.Footnote 27

From the early 1990s onward, the qualitative body of work on mediation has been supplemented with statistical studies, which have revealed some strong empirical patterns. However, these statistical studies are rooted within a materialist framework, just like the early works on mediation. In one of the first quantitative studies on international mediation, Bercovitch finds that the “possession of resources and an active strategy provide the basis for successful mediation.”Footnote 28 In a more refined analysis, Schrodt and Gerner find that sanctions directed toward both of the conflict parties, while simultaneously providing positive incentives toward the weaker party, is the most effective mediation strategy.Footnote 29 It is thus not surprising, based on the current literature on mediation, that in their literature review on international mediation, Greig and Diehl assert that mediation by a weak mediator is not effective because it is “limited in the resources that can be brought to bear in the talks as a means of pushing the parties to make concessions and leverage an agreement between the two sides.”Footnote 30

At least four types of material incentives can be identified that mediators can provide to persuade conflict parties to make peace. First, a third party can use sanctions to leverage costs on conflict parties, thereby persuading them to make peace.Footnote 31 Second, a third party can use force simultaneously alongside its mediation efforts. The use of force can be broadly defined as a military intervention to move the conflict parties to compromise, as well as the use of military inducements, either through extending—or refusing to extend—military assistance.Footnote 32 Third, a third party can provide or promise side payments to one or both of the conflict parties, which may induce them to make peace.Footnote 33 Fourth, a third party can guarantee nondefection with agreements, thus overcoming fears of the other party reneging on the agreement in the implementation phase.Footnote 34

It follows from the capacity-based mechanisms of mediation success that the more economic and military resources a third party possesses, the more easily it can threaten conflict parties with imposing sanctions, use or threaten with force, provide financial rewards, and guarantee nondefection—which all result in the conflict parties having more incentives to make peace.

Legitimacy-Based Mediation

The role of legitimacy has received little consideration in the mediation literature, but the effectiveness of third parties without any military and economic capacity has been studied. Some research exists on what Svensson calls “pure mediators” or what Beardsley describes as “weak mediators,” but these studies define this type of mediation mainly by what it lacks, namely economic or military power.Footnote 35 Instead I focus on the possible characteristics that mediators might have—namely legitimacy—despite lacking material resources.

Although third-party legitimacy has received little attention, the idea that the success of third parties is also based on ideational sources of social control is not new. As early as 1967, Young described both tangible and intangible characteristics of a third party that he deemed necessary for effective intervention in international crises.Footnote 36 Aall has asserted that the legitimate power of a mediator arises “from the parties’ perception that the mediator has the right to act as a third party and to ask for changes in behavior or compliance.”Footnote 37 Reid puts forward the concept of “credibility leverage,” which is a context-dependent conceptualization of mediator leverage in which the mediator's effectiveness is understood to be dependent on their contextual knowledge, information, and connections to the disputants to exert influence.Footnote 38 However, few scholarly attempts have yet been made to spell out exactly what the third party's legitimacy entails and how it operates in mediation processes.

While scant scholarly attention has been paid to legitimacy in the international mediation literature, there is a major interest in questions of legitimacy among International Relations scholars. A common element in most studies on international legitimacy is that it is discussed in relation to other forms of social control. For instance, in his seminal piece on legitimacy in international politics, Hurd considers three possible ideal types of social control.Footnote 39 The first two of these ideal types are in line with the capacity-based perspective of mediation and address a superior actor's ability to get a subordinate actor to obey because of fear of punishment or because of providing benefits, whereas the third type of social control that Hurd identified relates to how an actor complies with another actor because it feels that what this actor wants is legitimate and therefore ought to be obeyed.Footnote 40 Based on this last type of influence, Hurd defines legitimacy simply as the “normative belief by an actor that a rule or institution ought to be obeyed.”Footnote 41 From this perspective, legitimacy is thus necessarily a subjective quality.

Consequently, when assessing a third party's degree of legitimacy in any mediation effort, one has to assess to what extent compliance with the third party can be justified on the basis of beliefs by the conflict parties that complying with the mediator is the right thing to do. International norms are particularly relevant in terms of justifying compliance.Footnote 42 Norms can be defined as “collective expectations about proper behavior for a given identity.”Footnote 43 Since norms are collective expectations, by definition they require intersubjective agreement between at least two actors.Footnote 44

A high degree of third-party legitimacy results in a normative pull toward compliance with the third party. Franck points out that an actor or rule that is perceived as legitimate “exerts a pull toward compliance on those addressed normatively because those addressed believe that the rule or institution has come into being and operates in accordance with generally accepted principles of right process.”Footnote 45 The social processes that underlie this normative pull have been well documented within the field of social psychology. For example, Kelman shows how social influence is accepted because the change in behavior is congruent with the value system of both the influencing agent and the ones being influenced.Footnote 46 Similarly, Tyler concludes that “people internalize group values. They take on the values of the group as their own values. This leads them to voluntarily follow the decisions of group authorities. Breaking rules and disobeying decisions made by authorities has greater negative implications for the self, whereas rule following has greater positive implications.”Footnote 47

The normative pull of the African solutions norm has not gone unnoticed in the literature. Červenka noted in 1977 that the search for compromises is “regarded as a moral obligation on the conflicting parties to settle their dispute in the interests of African unity.”Footnote 48 Amoo and Zartman identify a high degree of “moral authority” as the main strength of the OAU and assert that Africa's normative environment provides the basis for a perceived obligation among conflict parties to search for a mediated solution.Footnote 49 More specifically, they postulate that “the sense of solidarity and fraternal atmosphere among African leaders” contributes to conflict parties making concessions “in the spirit of African solidarity and unity.”Footnote 50 Khadiagala notes that African mediators have “moral leverage.”Footnote 51 Gomes argues that the conflict-resolution efforts of African third parties rely heavily on moral persuasion predicated on similar values.Footnote 52

The involvement of African third parties during various peace processes in Sudan provides telling examples of how legitimacy contributed to the resolution of armed conflict. In 1965, during the first major peace negotiations aimed at ending Sudan's first civil war, delegates from Algeria, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Uganda were present to assist the conflict parties in finding a solution to the war. Mohammed Omer Beshir, the head of the Sudanese government delegation later reflected how a perception of legitimate involvement allowed the African diplomats to play a valuable role in the peace process: the observers “instilled the feeling in the delegates that the Conference should never be allowed to fail. They advocated the need to unite, to shake off the imperialist inheritances and conciliate religious differences.”Footnote 53 Similarly, Abel Alier, a prominent member of the opposition, recalls how the conflict parties were reluctant to let the observers “leave Sudan with bleak forebodings of the country's future.”Footnote 54 The first civil war was finally resolved in 1972, following mediation by Ethiopian Emperor Haile. Southern rebel leader Joseph Lagu notes how no “carrots and sticks” were used during the negotiations in 1972 and how Selassie emphasized pan-African ideals to underscore the importance of a peace deal.Footnote 55

African third parties also enjoyed a relatively high level of legitimacy during Sudan's second civil war, which started in 1983. At the start of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) mediation effort in 1994, Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir suggested that “Africans have become mature enough to resolve their own problems and are no longer in need of a foreign guardian” and further stated that the IGAD mediation efforts would be “without loopholes through which colonialism can penetrate on the pretext of humanitarianism.”Footnote 56 IGAD's legitimacy allowed the commencement of a mediation process, which eventually led to a breakthrough in the negotiations in 2002, the conclusion of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2005, and a referendum on independence for the South to be held in 2011.

In line with the theoretical argument I set out, one would expect the commitment to the African solutions norm to translate to a strong belief among conflict parties that they should comply with African third parties. This leads to the following testable implication.

H1a African third parties are more likely to mediate a negotiated settlement in civil wars in Africa than non-African third parties.

The conclusion of a negotiated settlement marks a significant turning point in peace processes. Yet, by itself, a negotiated settlement is only a piece of paper. Evidence suggest that peace agreements are more likely to fail than they are to succeed in bringing about lasting peace.Footnote 57 This begs the question whether conflict parties might just sign a negotiated settlement in peace processes mediated by African third parties, but not stick to the agreement. I expect the opposite to be true. As a result of the higher degree of legitimacy that African third parties enjoy, African mediation is likely to be more sustainable than non-African mediation. Many studies on the consequences of power find that a change in an actor's behavior on the basis of a normative pull toward compliance is more durable than a change in behavior on the basis of threats and rewards.Footnote 58

These more general studies on power seem to be in line with studies specifically focusing on mediation. Most of the causal mechanisms Beardsley identifies to explain why mediated agreements often break down relate to material incentives that third parties cannot indefinitely prolong to ensure peace.Footnote 59 Reid argues how, contrary to mediation efforts based on strong, immediate material pressure, mediation efforts in which mediators draw on their relationship with the conflict parties tend to “contribute a more persistent or durable pressure for peace.”Footnote 60 Indeed, if conflict parties sign an agreement because they perceive complying with the third party is the right thing to do, then they will perceive implementing this agreement also as the right thing to do.

A telling example of how third-party legitimacy contributes to the implementation of an agreement is the Sudanese government's compliance with the CPA concluded in 2005, which stipulated a referendum on the independence of the southern part of the country. Five days prior to the start of the referendum, President al-Bashir gave a speech in Juba on 4 January 2011 in which he emphasized how his commitment to pan-Africanism made him highly committed to abide by the referendum results: “Whatever be the choice of the southerners, we will accept it and say welcome … But let us provide a good example for brothers in Africa, even if we separate and we will do it peacefully, we will cooperate and provide them with the example of how the United States of Africa could be.”Footnote 61

I thus expect African mediation to be more likely to lead to a negotiated settlement that terminates a civil war than non-African mediation. This leads to the following testable implication.

H1b African third parties are more likely to mediate a negotiated settlement that terminates a civil war in Africa than non-African third parties.

Using the involvement of an African third party as a proxy for third-party legitimacy assumes that the level of legitimacy enjoyed by African third parties is evenly distributed across the continent, yet some conflict parties might be more committed to pan-Africanism and the African solutions norm than others. Indeed, a fundamental aspect of legitimacy is that it is a relational concept, which means that third-party legitimacy is the product of the third party's characteristics and how positively the conflict parties perceive these characteristics. African third parties should thus enjoy a high degree of legitimacy when the conflict parties are committed to the African solutions norm. I therefore expect the effectiveness of African third parties to be conditional on the conflict parties’ commitment to the African solutions norm.

It is, however, important to distinguish between the nature of the government and rebel parties’ commitment to the African solutions norm. By initiating an armed conflict, the rebel group has already expressed a willingness to challenge the norms of sovereignty and African unity. What makes them accept these norms during mediation? To answer this question, one has to consider the different type of rebel groups in civil wars in Africa. Several different types of rebel groups can be distinguished, each with different levels of commitment to the African solutions norm.

Reno explains how rebels who fought for majority rule in the white-minority-ruled southern African states saw themselves closely linked to the pan-African movement.Footnote 62 The Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) and the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) in Rhodesia, the African National Congress (ANC), and the South-West Africa People's Organization (SWAPO) in Namibia all justified their resort to armed violence on the basis of the anti-neocolonialism norm and even the African unity norm. Roessler and Verhoeven explain how these “majority rule” rebel groups were borne out of the pan-Africanist roots of liberation, which are at once ideological and strategic: regime change from “reactionary, neocolonialism” to “pan-Africanist liberation” was seen as not merely ideological but as a necessary condition for survival of the postindependence Africa state.Footnote 63

Another type of rebel group highly committed to pan-Africanism is what Reno refers to as reform rebels. This type of rebel group draws heavily on the ideology of anticolonial rebel groups and majority-rule rebel groups, but with the addition that independence alone is not sufficient to build strong African states.Footnote 64 Reform rebels emerged in Africa in the early 1980s. Soon after most African states had gained independence, this new generation of dissidents started to adopt a leftish, pan-African ideology to justify armed struggle against a “national bourgeoisie” which relied on extensive external support from outside Africa and that continued the “extractive, repressive and exclusionary” practices of their colonial predecessors.Footnote 65 Many of the leaders of Africa's reform rebel groups were actively schooled in pan-African political thought. For example, Yoweri Museveni, who would play a leading role in rebellions that ousted Idi Amin and later Milton Obote from power, was taught by Walter Rodney, a key figure in pan-African political thought, at the University of Dar es Salaam in 1968. While there, Museveni founded the University Students’ African Revolutionary Front (USARF). John Garang, who later became the leader of the SPLM/A in Sudan, also studied at the University of Dar es Salaam and became a member of the USARF. The founding manifesto of the SPLM/A heavily reflects this pan-African political thought.Footnote 66

While majority-rule and reform rebel groups are committed to the African solutions norm, other types of rebel groups in Africa do not necessarily have this ideological commitment. For instance, Reno discusses the warlord rebel group, which is a group of rebels that launch a war mainly for material gain.Footnote 67 Reno also discusses what he refers to as parochial rebels who mainly engage in civil war to protect circumscribed communities. Unlike reform rebels, parochial rebels do not link their rebellion to international ideas such as anti-neocolonialism and pan-Africanism, but rather articulate distinct local ideas about politics and administration.Footnote 68 Finally, rebel groups that self-identify as jihadist are also unlikely to be committed to the African solutions norm. Norms like sovereignty and African unity hold little value for rebels who fight to return society to what they deem a purer form of Islam.

In short, majority-rule and reform rebel groups, which Roessler and Verhoeven refer to as (neo)liberation movements, generally display a greater commitment to the African solutions norm than warlord rebels, parochial rebels, or jihadist rebels. I expect African third parties to be more effective when they mediate in civil wars in which the rebels are committed to the African solutions norm. This leads to the following testable implication.

H2a The effectiveness of African third parties is conditional on the rebel side being part of a (neo)liberation movement.

I also expect that an African third party's legitimacy is conditional on its government's commitment to the African solutions norm, but the nature of a government's commitment to this norm is different. Unlike rebel groups who already challenge the norms of sovereignty and African unity by taking up arms, governments have an interest in committing to sovereignty and African unity.Footnote 69 The African unity norm prescribes that other African states cannot support the armed opposition.Footnote 70 The sovereignty norm allows government to determine the nature of international involvement, whether this is external support to the government, mediation, or no mediation at all. Nolutshungu notes how the Chadian government emphasized the norm of sovereignty during the various mediation efforts in its war against the Front de libération nationale du Tchad (FROLINAT) to retain “a line of retreat, underlining the voluntarism of the process.”Footnote 71 Although there's a general interest among governments that experience a civil war to commit to sovereignty and African unity, there is still variation in terms of governments’ commitment to the African solutions norm.

This variation is mainly driven by the ascent to state power of pan-African nonviolent protest movements or pan-African rebel groups. As Roessler and Verhoeven observed, virtually all (neo)liberation movements in Africa have drawn on a pan-Africanist and anti-imperialist ideology.Footnote 72 These movements have remained committed to pan-Africanism after capturing power through rebellion or popular mobilization. For example, as leader of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) and the first prime minster of Tanganyika, which would turn into Tanzania in 1964 after a union with Zanzibar, Julius Nyerere played a crucial role in defining the norm of African nonalignment and helped mobilize African support to liberation movements in Southern Africa. Similarly, after coming to power in South Africa through elections in 1994, the ANC continued to make all its foreign policy decisions based on the idea of an African renaissance, solidarity with African governments, and an anti-imperialist paradigm.Footnote 73

Reform rebel groups that capture state power have also shown a commitment to the African solutions norm. For example, Ugandan President Museveni, who came to power with the National Resistance Army (NRA) in 1986, not only displayed a preference for African solutions in Uganda, but actively promotes the African solutions norm throughout Africa. Commenting on the civil war in Libya in 2011, he stated that the Libyan crisis is an “African problem and therefore calls for an African solution.”Footnote 74 In short, one would expect the level of African third parties’ legitimacy on average to be greater in countries where the leaders have come to power through a liberation or a neoliberation revolution. Accordingly, a legitimacy-based mediation perspective would suggest that African third parties are more effective when they mediate in a civil war in which the government side is committed to the African solutions norm. This leads to the following testable implication.

H2b The effectiveness of African third parties is conditional on the government being a former (neo)liberation movement.

I have considered the causal mechanisms of capacity-based and legitimacy-based mediation mainly in isolation. However, while these forms of mediation can be distinguished analytically, in reality the two types of process often overlap. This echoes Hurd's observation that coercion, inducement, and legitimacy are rarely found in their pure isolated forms.Footnote 75 I have argued that African third parties draw relatively more often on their legitimacy, whereas non-African third parties draw more often on their capacity, but how do these different types of power combine to affect outcomes of mediation? I postulate that as long as African third parties provide the mediation effort with legitimacy, non-African third parties can further increase the mediation effort's effectiveness. Capacity-based and legitimacy-based mediation should generally supplement each other. While the legitimacy of African third parties pulls the conflict parties toward compliance, non-African involvement provides additional material incentives to make peace. This leads to the following hypothesis.

H3 Joint African and non-African mediation efforts are more likely to lead to the conclusion of a negotiated settlement in civil wars in Africa than mediation efforts conducted solely by African third parties.

Alternative Explanations

The Role of Cultural Similarity

A first alternative explanation for why African third parties are more effective than non-African ones is that a cultural similarity between the African mediator and the African conflict parties drives the effectiveness of African third parties. Several studies highlight that mediators who share a similar culture with the conflict parties understand the complex social, political, and economic dynamics that underlie armed conflicts. Autesserre shows that a greater understanding allows the mediator to more effectively resolve the conflict.Footnote 76 However, her research is mainly aimed at the local level, whereas I am mainly concerned with peace agreements concluded at the country level. The elites participating in peace negotiations aimed at bringing peace to an entire country are probably adept at interacting with international diplomats. While observers acknowledge that African third parties are more likely to be similar to African conflict parties in terms of language, religion, and race than non-African third parties, a high degree of cultural variation nevertheless exists in Africa, both between and within countries. Cultural similarities alone can therefore not explain why African third parties are more effective than non-African third parties. I will examine the impact of the chief mediator's culture in the statistical analysis to test this argument.

Third-Party Willingness to Shape Material Incentives

Another alternative explanation is that African third parties might be more willing to draw on their economic and military resources to induce or pressure the conflict parties to make peace. African states experience the negative spillover effects of civil wars and might therefore be more determined to resolve civil wars in Africa, making them also more likely to put the conflict parties under pressure. If this is indeed the case, then it is not necessarily the African third parties’ higher degree of legitimacy that explains their effectiveness, but rather a disproportionate inclination to use a “sticks and carrots” approach. By contrast, if it is really legitimacy that explains the success of African third parties, then one would expect them to be effective, regardless of the material incentives provided to the conflict parties to make peace. This touches upon the essence of testing an ideational theory: to establish how much ideas matter, one also needs to know how much material factors matter.Footnote 77 The quantitative analysis assesses to what extent the effectiveness of African third parties is driven by a mediation strategy that draws on third-party capacity.

African-biased Mediation

Mediator bias might also explain African third-party effectiveness. Rauchhaus defines unbiased mediation as the involvement of a mediator who cares about the nature of the negotiated settlement but prefers a compromise over either party's ideal point. By contrast, a mediator is biased if they share the same ideal point as one of the parties.Footnote 78 While interstate conflict is rare in Africa, civil wars are often internationalized, with African states supporting one of the conflict parties. This means that African third parties’ effectiveness might be the result of third-party bias rather than legitimacy. Previous studies have found that biased third parties might be effective because they can (1) persuade the conflict parties to make concessions through promising or threatening to resume, step up, scale down, or terminate external support;Footnote 79 (2) credibly reveal information;Footnote 80 and (3) more effectively mitigate the commitment problem of governments if they are biased toward the government side.Footnote 81

However, I argue that biased African third parties are ineffective because being biased undermines the mediator's legitimacy and thus makes them lose their primary source of mediation success. Third-party legitimacy is the normative belief by the conflict parties that they should comply with the mediator. As I explained earlier, a commitment to the African solutions norm is a major reason that conflict parties will generally believe that they should comply with African third parties. However, other ideas and norms can influence the level of third-party legitimacy too. The norm of impartiality is such a norm. Conflict parties generally believe that the mediator should treat both sides of the conflict in an equal manner.Footnote 82 If a third party is biased, the mediation effort is likely to be perceived by at least one of the conflict parties as unfair. This, in turn, makes this conflict party re-evaluate their belief about how complying with the mediator is the right thing to do.

Non-African Third Parties Mediating the Harder Cases

A final alternative explanation for why African third parties might outperform non-African ones is that non-African third parties are more likely to mediate conflicts that are less prone to resolution. Since it is impossible to know how well a third party would perform in armed conflicts that are ex ante more difficult to resolve, the factors that can influence both mediation incidence and outcomes will be included in the empirical analysis. However, third parties may choose to mediate certain conflicts based on factors not controlled for or variables that are difficult to measure such as the conflict parties’ resolve.Footnote 83 If this is indeed the case, then the finding that African third parties outperform non-African ones might be a result of endogeneity, since the impact of these unobserved variables could bias the results.

There are at least two theoretical reasons for why African third parties are unlikely to mediate the easier cases than non-African third parties. First, potential African third parties are on average more exposed to the negative consequences of civil war in Africa, which provides them with strong incentives to try to resolve conflict even when resolution is unlikely. Second, African third parties are committed to the African solutions norm, which means they are determined to resolve civil wars in Africa regardless of whether these conflicts are prone to success. Consistent with these theoretical reasons, there is some evidence that regional mediators commonly are involved in especially hard-to-manage disputes.Footnote 84

Nevertheless, to exclude the possibility that non-African third parties are outperformed by African third parties because they mediate in cases less prone to mediation success, the empirical analysis deals with the endogeneity problem through an instrumental variable approach.

Research Design

To statistically test the effectiveness of African and non-African mediation, I created a data set on international mediation in civil wars in Africa. It covers mediation efforts in civil wars in Africa between 1960 and 2017 and builds on conflict data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP). The data set includes observation on the onset of mediation as well various aspects of mediation, including the chosen mediation strategy and the identity of the chief mediator.Footnote 85 In addition to drawing on news media sources, the data set draws on scholarly literature, nongovernmental organization (NGO) reports, and international organization (IO) reports such as UN Secretary General reports to the UN Security Council. This makes the data set the most comprehensive data set on mediation in Africa currently available. The unit of analysis is conflict dyad-years. A conflict dyad consists of a government and an organized rebel party.

The conclusion of a negotiated settlement, measured as a dichotomous variable, is used as a measurement of mediation success. To be included in the data set, a negotiated settlement should address the incompatible goals of the conflict parties by settling all or part of the conflict issues.Footnote 86 I combine data from the UCDP Peace Agreement data set, UN Peacemaker, and the PA-X data set, as well as secondary literature and news reports, to code whether a negotiated settlement is concluded in a given year.Footnote 87

To measure whether the negotiated settlement leads to a termination of the armed conflict, the data set also includes a binary variable coded as 1 if the conclusion of the negotiated settlement was followed by an inactive conflict dyad-year. The UCDP conflict data set is used to code whether a conflict turns inactive in the year following the conclusion of a settlement. This durable negotiated settlement variable thus essentially uses a stricter definition of a negotiated settlement, making it possible to determine whether or not a negotiated settlement actually terminates the conflict.

A third-party effort in a conflict has to fulfill at least two criteria to classify as mediation. First, the activity undertaken by the third party should be specifically aimed at achieving a compromise or a settlement of issues between the adversaries and second, the adversaries have to give their consent to the third party's involvement and to the final outcome of the mediation process.Footnote 88 To measure the types of mediation under study, I create two binary variables that measure whether an African or a non-African third party is involved in mediation respectively. I focus on the organizational identity of the mediator rather than the personal identity in order to code whether a third party is from Africa or not. This choice is theory driven because I expect the legitimacy and the capacity of the mandating agency to mainly influence the prospects for mediation success.Footnote 89

To isolate the impact of mediation efforts in which both African and non-African third parties are involved, I also create four mutually exclusive dummy variables: no mediation as the reference category, african mediation only, non-african mediation only, and mixed mediation. Mixed mediation takes place when at least one African and one non-African third party were involved in the mediation in a given conflict dyad-year.

This study also takes the conflict parties’ commitment to the African solutions norm into account. In reality, this commitment will range from a spectrum of no commitment to a high level of commitment. It is difficult to measure this spectrum of commitment to the norm in a precise manner, but what is possible is to identify a group of government and rebel parties that are at the far right end of the spectrum. As I discussed in the theory section, liberation movements and reform rebel groups, as well as governments that have come to power through a liberation or neo-liberation revolution, are generally at the end of the spectrum in terms of their commitment to the African solutions norm. Drawing on the conceptualizations of Reno and Roessler and Verhoeven, I have coded whether the governments and rebel groups in the data set are waging or have waged a (neo)liberation revolution.Footnote 90 Of the 1,114 conflict dyad-years, 412 (37 percent) include a government that is a former (neo)liberation movement.Footnote 91 The data set includes 196 (17.6 percent) dyad-years with a (neo)liberation rebel group.Footnote 92

In addition to the main independent variables, this study uses several variables to measure the impact of specific types of third parties. First, following the capacity-based mediation perspective outlined earlier, I construct a dummy variable that measures whether the third party engages in material manipulation of the bargaining environment. This variable is coded as 1 if a third party imposes sanctions, uses force simultaneously with the mediation effort, threatens to use sanctions or force, provides or promises side payments, and assures nondefection. Next, I use a variable that measures whether the chief mediator shares a similar culture with one or both of the conflict parties. I follow Inman and colleagues who operationalize culture by measuring religion, ethnicity, and language.Footnote 93 If the chief mediator shares all these three elements with one of the conflict parties, the shared culture variable is coded as 1. Finally, I follow Svensson's operationalization of biased mediation. Svensson codes third parties who have previously supported one of the conflict parties as biased mediators.Footnote 94

To reduce the risk of omitted variable bias, I control for a number factors in the subsequent statistical models that have been found to influence both the likelihood of mediation and the prospects for its success. These contextual factors include: whether the conflict is fought over a piece of territory or control over the capital;Footnote 95 the conflict's intensity;Footnote 96 the duration of the conflict measured in number of years;Footnote 97 and whether the conflict parties are supported with troops from another country.Footnote 98

I rely on logit models to examine the likelihood that a negotiated settlement is concluded given the dichotomous structure of the dependent variable. Robust standard errors are used in the logit models to assess whether the observations from the same conflict are related. Furthermore, the data used to study the likelihood that a negotiated settlement is concluded entail observations on the same unit of analysis over a series of time points, which may bias the findings as a result of temporal dependence. Following Beck, Katz, and Tucker, I use binary time-series cross-section correction to account for this potential bias.Footnote 99

Findings and Discussion

The International Mediation in Civil Wars in Africa data set includes 1,114 conflict dyad-years, of which 380 have experienced mediation. This constitutes 34.1 percent of the total number of conflict dyad-years. African third parties have been involved in mediation in 278 of the 380 conflict dyad-years in Africa between 1960 and 2017. In 138 of these conflict dyad-years, African third parties were involved in mediation simultaneously or jointly with non-African third parties. This means that African third parties have been involved in mediation without the involvement of any non-African third party in 140 conflict dyad-years. Non-African third parties have mediated in 244 conflict dyad-years, but non-African mediation without the involvement of African third parties has taken place in only 106 conflict dyad-years. Mixed mediation is thus the most common type of mediation in civil wars in Africa, followed by African and non-African mediation respectively.

A negotiated settlement was concluded in 170 conflict dyad-years in civil wars in Africa in the 1960–2017 period. Out of these negotiated settlements, twenty-one were concluded without third-party involvement. A further seventy-five were concluded with only African third parties involved in the dyad-year, only seven with solely non-African third parties involved in the dyad-year, and sixty-seven were concluded with a combination of African and non-African third parties involved in the dyad-year.

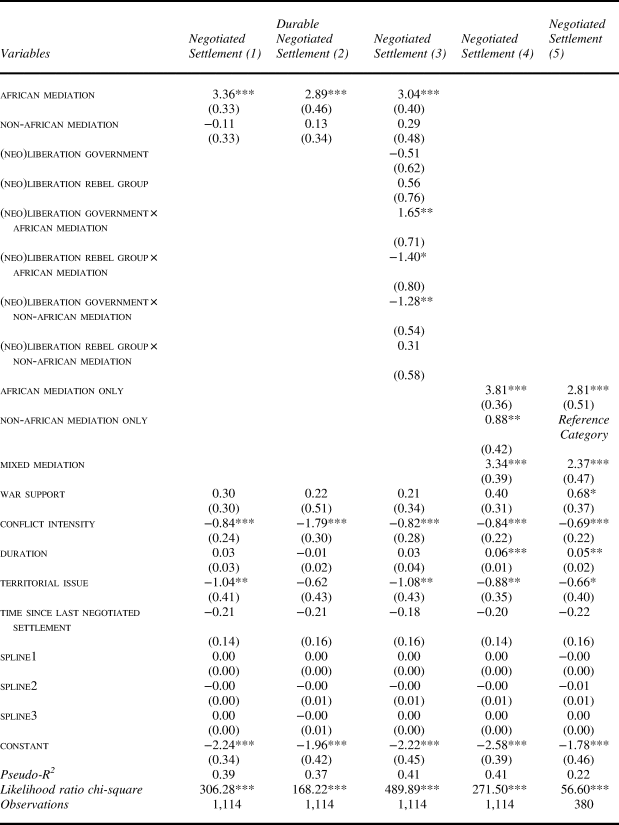

Table 1 shows the results for the comparison between the effects of the different types of third parties on the likelihood of the conclusion of negotiated settlements. Model 1 shows that compared to conflict dyad-years in which no mediation takes place, african mediation makes the conclusion of a negotiated settlement significantly more likely. This effect is not significant for non-african mediation, which means that the involvement of a non-African third party in a conflict dyad-year does not make the conclusion of a negotiated settlement more likely than when there is no mediation. The difference between the effect of the African and non-African mediation variables is statistically significant. This finding supports hypothesis 1a that African third parties outperform non-African ones.

Table 1. Logit estimates on the likelihood of negotiated settlements in civil wars in Africa, 1960–2017

Notes: Conflict dyad-years with no mediation is the reference category in models 1, 2, and 3. Conflict dyad-years in which only non-African third parties are involved is the reference category in model 4. Robust standard errors, clustered on the conflict level, are in parentheses. * p < .10; ** p <.05; *** p <.01.

African third parties also seem to outperform non-African third parties when it comes to the conclusion of durable settlements. Model 2 shows that African mediation makes the conclusion of a durable negotiated settlement—defined as a settlement that leads to the termination of the conflict—significantly more likely. The impact of non-African mediation in model 2 is statistically insignificant. The difference between the effects of African and non-African mediation is also significant in Model 2. This provides support for H1b.

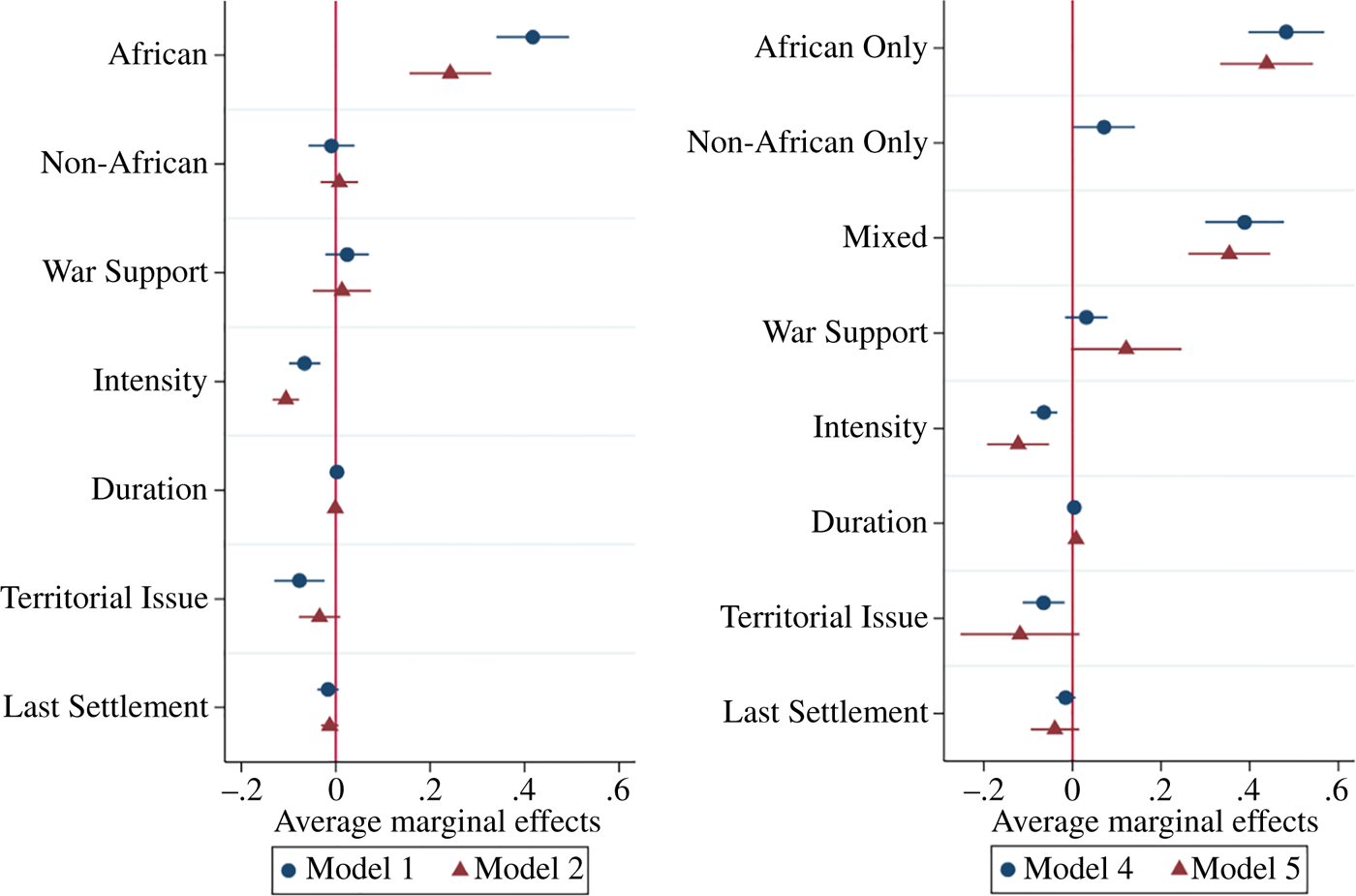

Figure 2 presents the average marginal effects of models 1 and 2 and 4 and 5 along with their 95 percent confidence intervals. The impact of a variable is statistically significant if its confidence interval does not overlap with the vertical line at 0. From the plot, one can see that the positive impact of African mediation on the likelihood of the conclusion of a negotiated settlement is not only statistically significant, but also substantively strong. All else equal, the likelihood of a negotiated settlement increases by 41.7 percentage points, from a probability of only 3.6 to 45.3 percent, when an African third party becomes involved in mediation. This figure is 24.3 percentage points for the impact of African mediation on durable settlements, from a probability of 2.7 to 27.0 percent.

Figure 2. Marginal average impact of African and non-African mediation on the conclusion of a negotiated settlement

It follows from model 3 that, in line with H2b, a (neo)liberation government makes African mediation more effective. The interaction between the (neo)liberation government and the African mediation variables is positive and statistically significant at the 5 percent level. Yet, a conflict with a (neo)liberation government makes non-African mediation less effective. Contrary to H2a, a rebel group being part of a (neo)liberation movement makes African mediation significantly less effective. Figure 3 graphically depicts the marginal impact of African and non-African mediation, conditional on the government being part of a former (neo)liberation movement and the rebel group being part of a (neo)liberation movement.

Figure 3. Marginal impact of African and non-African mediation on the conclusion of a negotiated settlement, conditional on the conflict parties’ commitment to the African solutions norm

When the government side is not a (neo)liberation regime in a given conflict, African mediation increases the probability of a negotiated settlement with 34.4 percentages points (from 4.4 to 38.8 percent). However, when the government side is a (neo)liberation regime, then African mediation increases the probability of a negotiated settlement increases with 54.4 percentages points (from 2.1 to 56.5 percent). The conditional impact of a (neo)liberation regime is negative for non-African third parties. All else equal, non-African mediation makes the conclusion of a negotiated settlement 2.7 percentage points more likely when the government side is not a (neo)liberation regime (from 13.6 to 16.3 percent). Yet, the probability of non-African mediation success decreases by 5.9 percentage points if the government side is a (neo)liberation regime (from 18.4 to 12.5 percent).

The conditional impact of a rebel group being a (neo)liberation movement is significant at only the 10 percent level for African mediation and statistically insignificant for non-African mediation. Strikingly, the conditional impact on African mediation is negative. When a rebel group is not part of a (neo)liberation movement, African mediation increases the probability of a negotiated settlement with 43.8 percentage points (from 3.1 to 46.9 percent), but this is only 26.5 percentage points when the rebel group is part of a (neo)liberation movement (from 5.5 to 32.0 percent).

These findings thus suggest that a third party enjoying legitimacy in the eyes of the government side makes the conclusion of a negotiated settlement especially likely, whereas the rebel group perceiving the third party as legitimate seems to have no effect or probably even a negative effect. A plausible explanation for this finding is that governments have to make the concessions when concluding a negotiated settlement. As Svensson explained, government stands to relinquish authority, whereas the rebels stand to gain opportunities—recognition, time, and access to official state structures—during peace processes.Footnote 100 A third party who enjoys a high degree of legitimacy from the government side can draw on this legitimacy to pull the government side toward making concessions that pave the way for the conclusion of a negotiated settlement.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) involvement in the civil war in Guinea–Bissau in 1998 and 1999—is a telling example in this regard. Guinea–Bissau gained independence in 1973 following a rebellion by the Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC). Roessler and Verhoeven list Guinea–Bissau as a liberation regime because of the PAIGC's leftish, pan-African orientation.Footnote 101 In spite of the first multiparty elections in 1994, the PAIGC was still was in power in June 1998,when the Military Junta for the Consolidation of Democracy, Peace, and Justice took up arms against the government. The pan-African orientation of Guinea-Bissau's government translated to a high degree of legitimacy for the African third parties involved in the peace process. For instance, in early August 1998, the foreign minister of Guinea-Bissau, Delfim da Silva, stated that the civil war in his country required a regional solution and ECOWAS had to play a key role in the conflict-resolution process. Mediation by ECOWAS subsequently led to the conclusion of the Abuja Agreement on 2 November 1998.Footnote 102

A closer look at civil wars in which the rebel group is part of a (neo)liberation movement, on the other hand, shows that these civil wars typically involve governments that arguably display the least commitment to the African solutions norm. While SWAPO in Namibia, ZANU and ZAPU in Rhodesia, and the ANC in South Africa all had a pan-African ideology, the white minority regime in these countries could in no meaningful way be seen as members of the African society of states because these governments denied the status of African peoples.Footnote 103

Another example is the government of Morocco's lack of commitment to the African solutions norm in the context of the liberation rebellion by the Frente Popular de Liberación de Saguía el Hamra y Río de Oro (POLISARIO). Although African states were initially sensitive to the government of Morocco's fear of recognizing POLISARIO, this changed after Algeria pushed for the recognition of an independent Western Sahara. Emphasizing that the conflict was an issue of self-determination that the territorial integrity norm did not apply to, Algeria successfully put the issue on the OAU agenda.Footnote 104 This undermined African third parties’ legitimacy from the government's perspective and Morocco even suspended its membership in the OAU in 1984. These examples explain why a (neo)liberation rebel group's commitment to the pan-African solutions norm does not make African mediation more effective.

Looking at whether African and non-African mediation supplement each other, model 4 shows the effect of african, non-african, and mixed mediation on the conclusion of negotiated settlement. The three mediation variables are mutually exclusive. All three types of mediation have a positive impact, though the effect of non-African mediation is statistically significant at the 5 percent level. Yet, the substantive impact of African and mixed mediation is significantly greater than non-African mediation. Taking conflict dyad-years in which non-African mediation took place as the reference category and dropping all conflict dyad-years in which no mediation takes place, model 5 shows that African and mixed mediation are significantly more likely to lead to the conclusion of a negotiated settlement than non-African mediation. Compared to non-African mediation, African mediation makes a negotiated settlement 43.8 percent more likely (from 22.4 to 66.2 percent). This figure is 35.4 for mixed mediation (from 25.0 to 60.4 percent). The impact of mixed mediation is not significantly different from the impact of African mediation. This means that the findings do not support H3 that Joint African and non-African mediation efforts are more likely to lead to the conclusion of a negotiated settlement than mediation efforts solely conducted by African third parties. This could mean that in some cases African legitimacy and non-African capacity can supplement each other, but in other cases non-African involvement might undermine the legitimacy of the process. This finding thus calls for further research.

Alternative Explanations

Model 6 in Table 2 shows that controlling for the impact of material manipulation does not change the basic finding that African mediation has a positive impact on the likelihood that a negotiated settlement is concluded.Footnote 105

Table 2. Logit estimates on the likelihood of negotiated settlements in civil wars in Africa, 1960–2017

Notes: Conflict dyad-years with no mediation is the reference category. Robust standard errors, clustered on the conflict level, are in parentheses. * p < .10; ** p <.05; *** p <.01.

A cultural similarity does not seem to drive African third parties’ effectiveness either. The effectiveness remains when controlling for the impact of a chief mediator who shares a similar culture with one of the conflict parties.Footnote 106

It follows from model 6 that biased African countries do not make the conclusion of a negotiated settlement more likely. The ineffectiveness of African third parties with partisan interests is in line with the central argument that a preference for a particular side in a given conflict undermines the party's legitimacy. By contrast, biased non-African third parties have a positive and statistically significant effect on mediation success, though this effect is significant at only the 10 percent level. The material incentives that biased non-African third parties provide make it appealing to conflict parties to comply with these third parties despite their biases. For instance, the conflict parties in Angola's civil war were highly dependent on financial and military support from Russia and the US, which explains why the adversaries cooperated with the biased superpowers in the search for a negotiated settlement.

As a series of additional robustness checks, I also examined the impact of mediation by a neighbor, a major power,Footnote 107 the Community of Sant'Egidio, a former colonial power, and the UN. Controlling for these types of third-party efforts did not alter the main finding that African third parties outperform non-African ones. Controlling for only one of each of the different types of mediation controlled for did not alter this finding either.

Dealing with Endogeneity

Finally, I use an instrumental variable approach to examine whether non-African third parties are less effective because they mediate the conflicts less prone to mediation success. More specifically, I draw on a dummy variable that measures whether presidential elections take place in the US in a given year as an instrument for non-African mediation in a two-stage least-squares regression.

The us presidential elections variable meets the two primary criteria for an instrumental variable. First, the instrument has a direct effect on the possible endogenous variable.Footnote 108 Theoretically, we would expect that presidential elections held in the US make the onset of non-African mediation in civil wars in Africa more likely. The incentives of governments to mediate in a civil war are not only determined by the interests of a state, the severity of the war, and calls for resolution by the wider population, but are also determined by a government's willingness to showcase a foreign policy success. In democratic countries, one would therefore expect the willingness to become involved in mediation to be the greatest in election years. Since the US is the non-African state that has mediated most frequently in Africa between 1960 and 2017, one would expect a greater US inclination to mediate in US election years to translate to more non-African mediation in these years.Footnote 109

A wealth of anecdotal evidence suggests that the US indeed pushes for mediation in Africa in US presidential election years to score a foreign policy success. For example, in his memoir on the Tripartite Accord, which granted independence to Namibia from South Africa and ended the direct involvement of foreign troops in the Angolan Civil War, former US Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Chester Crocker recounts how during the presidential election campaign of 1988 “[Republican presidential candidate George H.W.] Bush commented on our negotiations in glowing terms on several occasions” and that conflict parties involved became “Republican Party exhibits” during the climax of the election campaign.Footnote 110

Another example is how US officials tried to make the Sudanese government and the SPLM/A reach an agreement prior to the State of the Union Address by President Bush in January 2004. Former Norwegian Minister of International Development Hilde Johnson recalls how in a round of negotiations, US Senior Representative on Sudan Mike Ranneberger told the other diplomats and the conflict parties that “it was important to have a framework agreement capturing the main principles before 20 January [2004]—the date of President Bush's State of the Union address. The parties were promised a Rose Garden ceremony.”Footnote 111 With still no final agreement concluded, US Senator John Danforth pointed at his watch during a round of negotiations in mid-2004 to signal that a peace agreement needed to be concluded on that day because US elections were coming up.Footnote 112

With its permanent seat in the UN Security Council, the US at times also pushes for the UN to become involved in mediation. For example, in mid-1992, with elections on the horizon, US diplomats tried to become part of the mediation team when the peace process in Mozambique gained momentum. After the US was allowed only international observer status, the US pushed the UN to become directly involved in the mediation process.Footnote 113 Together the US and the UN have been involved in 172 out of the 244 conflict dyad-years with non-African mediation, which amounts to 70.5 percent. The results reported in model 7 of Table 3, where I model the likelihood of non-African mediation, are in line with the anecdotal evidence that suggests that non-African mediation is more likely in US election years. A US presidential election year is a statistically significant predictor of non-African mediation.

Table 3. Ordinary least squares and two-stage least squares estimates on the likelihood of negotiated settlements in civil wars in Africa, 1960–2017

Notes: Conflict dyad-years with no mediation is the reference category. Robust standard errors, clustered on the conflict level, are in parentheses. * p < .10; ** p <.05; *** p <.01.

A second requirement of an instrument is that it should not directly affect the outcome variable, in this case the conclusion of a negotiated settlement, except through the mechanism of the possible endogenous variable.Footnote 114 There are no theoretical reasons to expect that presidential elections in the US directly affect the likelihood of the conclusion of a negotiated settlement in civil wars in Africa. Model 8 in Table 3 shows that US presidential elections do not directly influence the likelihood that a negotiated settlement is concluded in civil wars in Africa. In short, the instrument can be used for the consistent estimation of the impact of non-African mediation on the likelihood that a negotiated settlement is concluded.

Model 9 in Table 3 shows the effect of non-African mediation on the likelihood of the conclusion of a peace agreement through the use of the instrument. An F-score of 14.9, which is well above the commonly accepted threshold of 10, suggests that the US presidential elections year variable is sufficiently strongly correlated with non-African mediation.Footnote 115 The coefficient of non-African remains statistically insignificant. Moreover, the regression-based test of exogeneity score is statistically insignificant, which suggests that non-African mediation can be treated as an exogenous variable and that a two-stage least squares model is unnecessary. Overall, this provides support for the claim that the ineffectiveness of non-African third parties is not a result of them mediating civil wars that are unlikely to succeed in mediation.

Conclusion

Much of mediation efforts’ success depends on the relationship between the third party and the conflict parties. The social structure in which the third party and the conflict parties operate, in turn, greatly determines the nature of this relationship. Within the African society of states, African leaders generally perceive that they are bound by norms related to sovereignty, respect for the colonial borders, anti-neocolonialism, nonalignment, and peaceful conflict resolution. The collective commitment to this cluster of norms provides African third parties with a social status that, in turn, provides them with a high degree of legitimacy when mediating armed conflict in Africa. I have argued that this high degree of legitimacy makes African third parties more effective than non-African ones.

My statistical analyses support the argument that African mediation outperforms non-African mediation. Despite a higher degree of economic and military resources, non-African third parties are less effective in mediating civil wars in Africa than African ones. Indeed, something other than third-party capacity must explain the effectiveness of African third parties. The statistical analyses thus draw on what Hurd describes as the logical necessity of legitimacy to show that African mediation efforts are likely to be regarded as more legitimate than non-African mediation efforts.Footnote 116

African third parties’ effectiveness is conditional on the government side's commitment to the African solutions norm. This suggests that rather than just a low degree of third-party capacity, African third parties are effective because African governments perceive them as legitimate. Hence, I go beyond considering the effectiveness of mediators that are considered weak mediators or lacking “muscle.”Footnote 117 The effectiveness of African third parties is not a result of either the presence or the absence of third-party capacity, it is about the presence of legitimacy. In this article I thus explain why third parties from Africa that have comparable resources to “weak” non-African third parties like Norway or less resources than a non-African third party like the US are still more effective.

For example, Beardsley notes about Kofi Annan's mediation effort in Kenya's post-2007 electoral crisis that “Annan possessed no authority to promise aid or threaten sanctions against the intransigent parties, nor did he have better access to information about the capabilities and resolve of the respective parties than they had themselves.”Footnote 118 For this reason, Beardsley identifies Kofi Annan's mediation effort as a good example of a third-party effort by a weak mediator. This is a valid observation, but what Kofi Anan did have was a degree of third-party legitimacy. When the AU mediation team led by Anan arrived in Nairobi to mediate, they told the conflict parties that they had discussed the conflict with Nelson Mandela and that he sent his best wishes and sought to remind them that all of Africa was watching the process.Footnote 119 Almost one month later the conflict parties signed an agreement. This agreement would lay the basis for a grand coalition government that successfully mitigated the conflict.

One major question for future research is whether regional mediators in other regions can also draw on their third-party legitimacy. This question requires further research, but a preliminary analysis included in the appendix suggests that mediation efforts by regional third parties in the Middle East and Latin America—which are both regions where regional third parties with a high degree of third-party capacity are largely absent—are significantly less effective than nonregional mediation efforts. This could mean that the African solution norm bestows legitimacy onto African third parties that neither non-African third parties nor regional mediators in other regions benefit from.

The level of compliance with the African solutions norm in Africa contradicts the prevailing view in the literature that only third parties with a high degree of economic and military resources are effective in mediating civil wars. Clearly, security dynamics in Africa can be partly explained in realist terms, but international norms affect the behavior of African actors to a great extent. African conflict parties’ understandings of the international environment in Africa constitute an international structure that is highly influential in shaping the outcomes of mediation processes. From this perspective, it is striking that the role of third-party legitimacy has largely been ignored in the literature on international mediation. In essence, solely focusing on third-party capacity entails missing a relevant alternative source of mediation success, namely third-party legitimacy.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this article may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KPRL5U>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000041>.

Acknowledgments

I thank two anonymous reviewers, the IO editors, as well as Alex de Waal, Andrea Ruggeri, Andrew Hurrell, Christian Fastenrath, Duncan Snidal, Eelco van der Maat, Enzo Nussio, Erika Forsberg, Evan Perkoski, Govinda Clayton, Jennifer Welsh, Johan Brosché, Kristine Eck, Lee Seymour, Monica Toft, Ricardo Soares de Oliveira, Samantha Gamez, and Sophia Dawkins for excellent comments on earlier versions of this article. I especially thank Neil MacFarlane. Any remaining errors are my own.