Introduction

For the first time, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the International Criminal Court (ICC) are dealing concurrently with the same set of events, which concern the violence to which those in the group that self-identifies as the Rohingya have been subjected in Myanmar, and that has prompted their mass exodus to Bangladesh. Before both courts, proceedings are at a preliminary stage.

On July 4, 2019, the ICC Prosecutor, having decided to start a proprio motu investigation on the situation in Bangladesh/Myanmar, seized Pre-Trial Chamber III to obtain an authorization for the investigation, based on Article 15 of the Rome Statute.Footnote 1 The Prosecutor's Request was granted on November 14, 2019.Footnote 2

On November 11, 2019, the Republic of The Gambia (The Gambia) filed an Application instituting legal proceedings against the Republic of the Union of Myanmar (Myanmar) at the ICJ, alleging violations of the 1948 Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Genocide Convention). With the same Application, The Gambia also requested provisional measures.Footnote 3 The ICJ ordered provisional measures on January 23, 2020.Footnote 4

The ICC's Investigation Authorization

Pre-Trial Chamber III of the ICC agreed with the jurisdiction decision rendered by Pre-Trial Chamber I in 2018,Footnote 5 and found that the ICC could assert jurisdiction pursuant to Article 12(2)(a) of the Rome Statute if at least one element of a crime within the material jurisdiction of the Court were committed on the territory of a state party.Footnote 6 According to Pre-Trial Chamber III, there is a reasonable basis to believe that at least one element of the crimes against humanity of deportation and persecution, under Article 7(1)(d) and (h) of the Rome Statute respectively, were committed against the Rohingya on the territory of Bangladesh.Footnote 7 The latter, unlike Myanmar, is a state party to the Rome Statute. In making this determination, the Chamber also considered facts falling outside the jurisdiction of the ICC to establish whether the contextual elements of crimes against humanity were present.Footnote 8

The Chamber authorized the Prosecutor to investigate crimes committed at least in part on the territory of Bangladesh, as well as crimes committed at least in part on the territory of other states parties or of states making a declaration under Article 12(3) of the Rome Statute, and that were sufficiently linked to the situation as described in the decision.Footnote 9 With respect to the temporal jurisdiction of the Court, and going beyond what the Prosecutor had requested, the Chamber authorized her to investigate crimes that allegedly took place after the Rome Statute entered into force for the relevant states, including crimes committed after the issuance of the decision authorizing the investigation.Footnote 10 The Chamber also stressed that the Prosecutor was bound neither to investigate solely the events outlined in her Request, nor by their provisional legal characterization.Footnote 11

The ICJ's Order on Provisional Measures

Having found that a dispute between the parties appears to existFootnote 12 and that Myanmar's reservation to Article VIII of the Genocide Convention did not affect Myanmar's consent to the ICJ's jurisdiction under Article IX of the same Convention,Footnote 13 the ICJ concluded, without prejudice to the merits of the case, that it has prima facie jurisdiction.Footnote 14

The ICJ agreed with The Gambia that, because of the erga omnes partes character of some obligations under the Genocide Convention, The Gambia has an interest in Myanmar's compliance with those obligations without having to prove a special interest.Footnote 15 The Court based its conclusion on its Advisory Opinion on “Reservations to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide”Footnote 16 and on its judgment in Belgium v. Senegal.Footnote 17 Reliance by the Court on the latter case was criticized by Vice-President Xue, who emphasized that Belgium had instituted proceedings against Senegal because it was supposedly injured under the rules of State responsibility, and thus specially affected by the alleged violations, rather than simply because it had an interest in Senegal's compliance with the erga omnes partes obligations under the UN Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.Footnote 18

The Court further recognized that some of the alleged acts could be qualified as crimes other than the crime of genocide.Footnote 19 Nonetheless, it dismissed Myanmar's argument that the Court should determine whether the existence of genocidal intent—which is determinative in distinguishing genocide from other international crimes—was the only plausible inference to be drawn from the alleged facts.Footnote 20 Rather, the ICJ focused on the plausibility of the rights claimed by The Gambia.Footnote 21 This low standard of plausibility was criticized by ad hoc Judge Kress, appointed by Myanmar.Footnote 22 Conversely, Judge Cançado Trinidade argued that, because of the fundamental character of the rights requiring protection, there was no need to inquire about whether they were plausible.Footnote 23

Notwithstanding these slight disagreements among the judges, four provisional measures were granted unanimously by the ICJ.Footnote 24 First, Myanmar must take all measures within its power to prevent the commission of the acts listed in Article II of the Genocide Convention. Second, Myanmar must ensure that its military, as well as irregular armed units directed and supported by it, and organizations and persons under its control, direction, or influence do not commit any of the acts within the scope of Articles II and III of the Genocide Convention. Third, Myanmar is ordered to take effective measures to preserve evidence related to allegations of acts under Article II of the Genocide Convention. Fourth, Myanmar is required to submit a report on all measures taken pursuant to the Court's Order within four months of the issuance of the Order and then every six months until the Court renders a final decision on the case.

Conclusion

The ICJ's orders on provisional measures have binding effect for the Parties to a dispute before the Court.Footnote 25 In this case, the last two provisional measures indicated by the ICJ are quite novel and allow for a more active role of the Court in checking compliance with the measures ordered. They likely reflect the Court's attempt to avoid the tragic consequences of the violation of provisional measures regarding the prevention of genocide that had been ordered in Bosnia and Herzegovina v Serbia and Montenegro.Footnote 26

While the ICJ and the ICC are dealing with substantially the same subject matter, they have different mandates and jurisdictional constraints. For the ICJ, such constraints relate to the fact that its jurisdiction derives from Article IX of the Genocide Convention and is thus restricted to the subject matter of this Convention, whereas for the ICC the issue is that Myanmar is not a state party to the Rome Statute.

Nonetheless, both courts have remarked that the alleged crimes under their scrutiny are susceptible to multiple legal qualifications, and that one qualification does not exclude others. These clarifications open the possibility for both courts to make divergent, but equally valid, determinations regarding the nature of the alleged crimes, based on their respective jurisdiction and on the nature of the proceedings before them. Thus, at the merits stage, it will be entirely possible for the ICJ to characterize as genocide acts for which individuals will be prosecuted at the ICC under charges of crimes against humanity. It remains to be seen whether and how the parties to proceedings before either court will attempt to exploit these divergent interpretations.

Original: English No. ICC-01/19

Date: 14 November 2019

PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER III

Before: Judge Olga Herrera Carbuccia, Presiding Judge

Judge Robert Fremr

Judge Geoffrey Henderson

SITUATION IN THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH/REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR

Public

Decision Pursuant to Article 15 of the Rome Statute on the Authorisation of an Investigation into the Situation in the People's Republic of Bangladesh/Republic of the Union of Myanmar

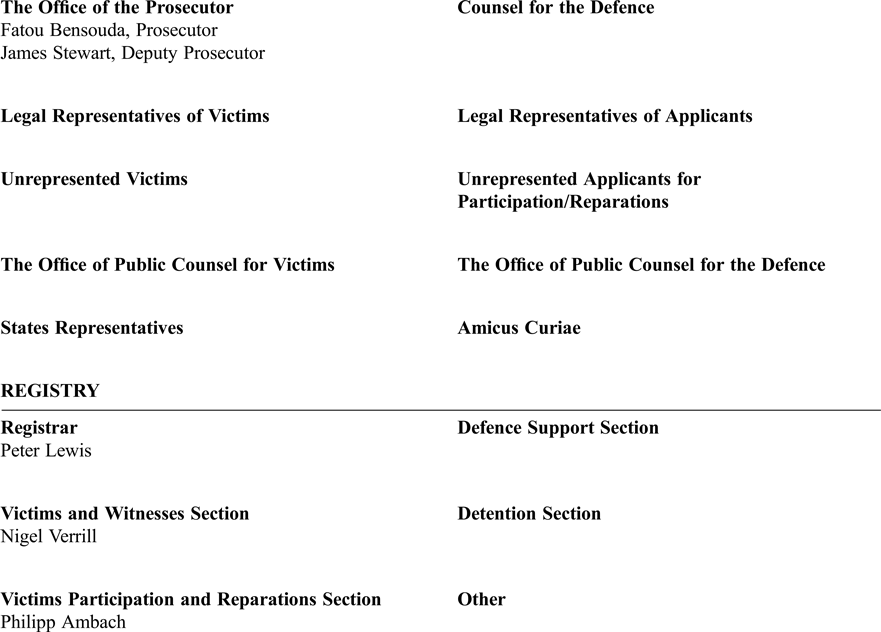

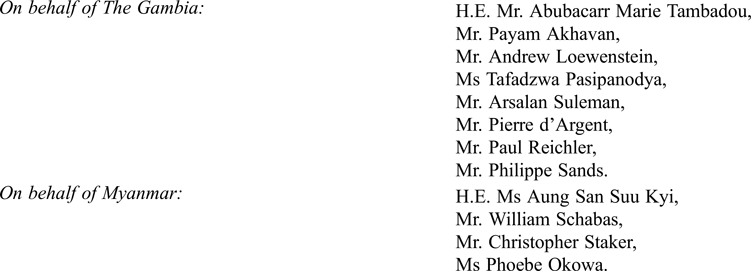

Decision to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to:

I. Procedural history

II. Procedure under Article 15 of the Statute

III. Preliminary consideration

IV. Victims’ representations

A. Introduction

B. Views on the scope of the investigation

C. Views on gravity and the interests of justice

1. Gravity

2. Interests of justice

V. Jurisdiction

A. Jurisdiction ratione loci

1. Applicable law

i. Meaning of the term ‘conduct’ in article 12(2)(a) of the Statute

ii. Location of the conduct

2. Conclusion

B. Jurisdiction ratione materiae

1. Alleged contextual elements of crimes against humanity

i. Applicable law

ii. Alleged contextual facts

a. Background

b. Systematic or widespread attack directed against any civilian population

c. Alleged State policy

iii. Conclusion

2. Alleged underlying acts constituting crimes against humanity

i. Applicable Law

a. Deportation

b. Persecution

ii. Alleged facts

a. Deportation

b. Persecution

iii. Conclusion

C. Jurisdiction ratione temporis

VI. Admissibility

A. Complementarity

B. Gravity

C. The interests of justice

VII. The scope of the authorised investigation

A. Territorial scope of the investigation (ratione loci)

B. Material scope of the investigation (ratione materiae)

C. Temporal scope of the investigation (ratione temporis)

PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER III of the International Criminal Court (‘Court’) issues this ‘Decision pursuant to Article 15 of the Statute on the authorisation of an investigation into the Situation in the People's Republic of Bangladesh/Republic of the Union of Myanmar (the ‘Situation in Bangladesh/Myanmar’)’.

I. Procedural history

1. On 6 September 2018, Pre-Trial Chamber I issued its ‘Decision on the “Prosecution's Request for a Ruling on Jurisdiction under Article 19(3) of the Statute”’Footnote 1 (the ‘Jurisdiction Decision’) finding that the Court may assert jurisdiction pursuant to article 12(2)(a) of the Statute if at least one element of a crime within the jurisdiction of the Court or part of such crime is committed on the territory of a State Party to the Statute.Footnote 2

2. On 12 June 2019, the Prosecutor informed the Presidency, pursuant to Regulation 45 of the Regulations, of her intention, pursuant to article 15(3) of the Statute, to submit a request for judicial authorisation to commence an investigation into the Situation in Bangladesh/Myanmar.Footnote 3

3. On 25 June 2019, the Presidency constituted this Chamber, and assigned the Situation in Bangladesh/Myanmar to it, with immediate effect.Footnote 4

4. On 27 June 2019, the judges of the Chamber designated Judge Olga Herrera Carbuccia as Presiding Judge.Footnote 5

5. On 4 July 2019, the Prosecutor requested the Chamber ‘to authorise the commencement of an investigation into the Situation in Bangladesh/Myanmar in the period since 9 October 2016 and continuing’ (the ‘Request’).Footnote 6

6. On 30 August, 13 and 27 September, and 11 and 31 October 2019, in accordance with the Chamber's decision granting an extension of time for victims to make representations under article 15(3) of the Statute,Footnote 7 the Victims Participation and Reparations Section (the ‘VPRS’) of the Registry submitted reports on victims’ representations.Footnote 8

7. On 21 October 2019, the Prosecutor submitted supplementary information regarding the admissibility criterion, in particular complementarity.Footnote 9

8. On 23 October 2019, the Chamber received a representation made by the Legal Representatives of Victims on behalf of 86 victims from the village of Tula Toli.Footnote 10

9. On 11 and 31 October 2019, victims’ representations were transmitted to the Chamber.Footnote 11 On 31 October 2019, VPRS also filed its Final Consolidated Report on victims’ representations.Footnote 12

10. On 7 and 11 November 2019, further victims’ representations were transmitted to the Chamber.Footnote 13

II. Procedure under Article 15 of the Statute

11. The procedure for initiating an investigation upon the Prosecutor's own initiative is regulated by article 15 of the Statute. This provision subjects the Prosecutor's power to open an investigation proprio motu to the judicial scrutiny of the Pre-Trial Chamber.Footnote 14 Article 15(3) provides that, ‘[i]f the Prosecutor concludes that there is a reasonable basis to proceed with an investigation, he or she shall submit to the Pre-Trial Chamber a request for authorization of an investigation, together with any supporting material collected’.

12. Article 15(4) of the Statute clearly states the limited mandate of the Chamber at this stage of the proceedings:

[i]f the Pre-Trial Chamber, upon examination of the request and the supporting material, considers that there is a reasonable basis to proceed with an investigation, and that the case appears to fall within the jurisdiction of the Court, it shall authorize the commencement of the investigation, without prejudice to subsequent determinations by the Court with regard to the jurisdiction and admissibility of a case.

III. Preliminary consideration

13. The Chamber notes that the Prosecutor states that the term ‘Rohingya’ is contested:

The Rohingya self-identify as a distinct ethnic group with their own language and culture, and claim a long-standing connection to Rakhine State. Successive Myanmar Governments have rejected these claims. Instead the Rohingya are widely regarded as ‘illegal immigrants’ from neighbouring Bangladesh, and are often referred to as ‘Bengalis’. Even use of the term ‘Rohingya’ is contested.Footnote 15

14. Nevertheless, the Prosecutor uses the term throughout the Request and she identifies and refers to the victims of the alleged crimes as the ‘Rohingya’.Footnote 16

15. The material on the record also points to the use of the term Rohingya as being contested. Reports prepared by the Irish Centre for Human Rights (the ‘ICHR’),Footnote 17 International Crisis Group (the ‘ICG’),Footnote 18 and Amnesty InternationalFootnote 19 indicate that persons who identify themselves as Rohingya reportedly claim that the term denotes an ethno-religious group.Footnote 20 Whereas reports prepared by the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (the ‘OHCHR’)Footnote 21 and Public International Law & Policy Group (the ‘PILPG’)Footnote 22 indicate that other ethnic groups in Myanmar reject this claim.Footnote 23 Certain Burmese sources on the record indicate that Myanmar authorities do not recognise the term ‘Rohingya’.Footnote 24 Other documents, including a report by Fortify Rights,Footnote 25 indicate that governmental authorities have denied the existence of the Rohingya as an indigenous groupFootnote 26 instead, State authorities refer to them as either ‘Bengali'Footnote 27 or ‘the Muslim community in (northern) Rakhine State’.Footnote 28 Further, a report from Amnesty International contains references to new reports where the Bangladeshi Home Minister used the term,Footnote 29 whereas the agreement concluded on 23 November 2017 between Bangladesh and Myanmar on the return of displaced persons from Rakhine State does not employ it.Footnote 30

16. The Chamber notes that certain victims in their representations have emphasised their wish to be recognised as and called ‘Rohingya’ instead of other denominations, such as ‘Bengali’ or ‘Khola’—a derogatory Burmese term—or even ‘Non-Myanmar national Bengali’ and ‘illegal immigrants’.Footnote 31

17. It is also noted that the United Nations General Assembly ( the ‘UNGA’) has used the term in its resolutions and called upon the Government of Myanmar to allow self-identification.Footnote 32 In that respect, and considering the discussion above, the Chamber will employ the term ‘Rohingya’ in the present decision to refer to the alleged victims individually and collectively.Footnote 33 Notwithstanding this, the Chamber stresses that the use of the term in this decision does not imply endorsement of any particular historical narrative or political claim, or recognition of a specific group for purposes outside of the present decision. The Chamber also emphasises the need for further analysis of this issue during any future stages of proceedings before the Court.

IV. Victims’ representations

A. Introduction

18. The Chamber notes that within a relatively short time span, the Registry has collected and transmitted representations on behalf of a significant number of alleged victims of the Situation in Bangladesh/Myanmar that have come forward to present their accounts and views on whether or not the Chamber should authorise the commencement of the Prosecutor's investigation into this situation. Victims have also provided valuable information relevant to the scope of an eventual investigation.

19. Generally, the victims’ representations confirm the information provided by the Prosecutor in the Request. These victims’ representations, which were gathered from individuals and organisations representing alleged victims living in all camps in Bangladesh, also appear to be a representative sample of the affected population and thus useful in the Chamber's assessment of the merits of the Prosecutor's request.Footnote 34 Although the Chamber has reached its decision on the basis of the material provided by the Prosecutor, the abundant information contained in the victims’ representations would have also allowed the Chamber to reach the same conclusion.

20. The Court received a total of 339 representations in English (311 representations were submitted in written form and 28 were put forward in video format).Footnote 35 The Registry engaged with victims directly, as well as with individuals and organisations working with the affected communities.Footnote 36 The Registry received representations that were submitted in English, but also in Burmese, and in Bengali. The Registry also received video representations in Rohingya.Footnote 37 The Registry reports that it was able to travel or meet individuals from all 34 refugee camps in Bangladesh and held more than 60 meetings with approximately 1,700 individuals.Footnote 38

21. The Chamber has reviewed victims’ representations submitted or translated into English. In the First Registry Transmission, a total of 29 victims’ representations were notified to the Chamber.Footnote 39 In the Second Registry Transmission, a total of 176 victims’ representations were transmitted to the Chamber (174 written forms and two video representations).Footnote 40 In the Third Registry Transmission, a total of 85 representation forms were transmitted to the Chamber, along with 16 videos in support of some representations.Footnote 41

22. The victims’ representations transmitted represent either small family groups or were completed on behalf of a larger community of victims (i.e. living in the same refugee camp). The Registry indicates that a few representations still need to be translated into English. These will be transmitted to the Chamber after the set deadline.Footnote 42 Nonetheless, the Registry estimates that out of the transmitted representations, ‘202 representations were introduced on behalf of approximately 470,000 individual victims, two were submitted on behalf of a total of eight families and one representation was introduced on behalf of one village’.Footnote 43 Further, multiple representations were submitted on behalf of thousands of alleged individual victims.Footnote 44

23. The Chamber acknowledges all the individuals, groups and organisations that have come forward to present their views and accounts of the events pertaining to the present situation.

24. The Registry submitted a total of five reports during the present article 15 proceedings. Therein, the Registry explained the approach taken when reaching out to the victims,Footnote 45 emphasised the high interest amongst the victims to participate in the process,Footnote 46 but also stressed the logistical challenges faced by the VPRS when collecting victims’ representations.

25. The Registry also made it clear that it was not in a position to verify the accuracy of the information contained in the representation forms, in particular the number of victims allegedly represented. It states that, as previously done in situations before the Court, and in light of the applicable standard of proof, when reporting to the Chamber it has taken into consideration the intrinsic coherence of the information provided by the victims and their representatives.Footnote 47

B. Views on the scope of the investigation

26. All victims’ representations are submitted on behalf of alleged victims who, as a result of the alleged attack against Rohingya in Myanmar, were forced to seek refuge in Bangladesh.Footnote 48

27. Most victims’ representations allege that crimes were committed during the 2017 wave of violence. However, some victims’ representations allege that crimes (particularly, those concerning coercive acts of deportation) took place at an earlier time, as of 2012.Footnote 49 The Registry reports that a large number of victims request that the alleged conduct after 1 June 2010 also be covered by an eventual investigation.Footnote 50

28. Alleged coercive acts: as noted above, all victims’ representations are submitted on behalf of alleged victims who either survived or witnessed the coercive acts described below in this subsection and who, as a result of these coercive acts, now live in refugee camps in Bangladesh or in other countries. Several victims’ representations describe how they had no choice but to leave Myanmar.Footnote 51 One victims’ representation clearly describes the cause-effect of the coercive acts they allegedly suffered and the resulting deportation: ‘We lost our family members. We survive with [gunshot] wounds. We lost our property, our houses, our lands and cattle and everything. Kicked out from our motherland and made us refugee. Destroyed our everything.’Footnote 52 Another representation, submitted on behalf of women, also states that the ‘atrocities of August 2017 were the turning point of the Rohingya crisis, after this date none of the women represented could return to their motherland Myanmar’.Footnote 53 A representation submitted on behalf of alleged victims living in the same refugee camp in Bangladesh similarly states that victims ‘decided to escape and save our lives from the extra-judicial killings […] the people had just one way to save their lives. [It] was to come to Bangladesh’.Footnote 54

29. Alleged killings underlying the alleged coercive acts: several individuals filling in the victims’ representations directly witnessed the killing of close family members, who they are now seeking to represent.Footnote 55 Victims’ representations refer to attacks in which the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw) and other Myanmar security forces allegedly entered villages and started shooting indiscriminately at villagers.Footnote 56 Victims’ representations also mention that children were often targeted and killed, including small children who were thrown into water or fire to die.Footnote 57 Victims’ representations refer to entire families being torched after perpetrators locked them in their homes.Footnote 58 Other victims’ representations report how Rohingya were allegedly killed on their way to Bangladesh.Footnote 59

30. Alleged arbitrary arrests and infliction of pain and injuries underlying the alleged coercive acts: many victims’ representations refer to mass arrests of Rohingya men, including influential community leaders, who were allegedly detained by the Myanmar authorities in order to assess whether or not they had ties with or knowledge of Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (hereinafter ‘ARSA’).Footnote 60 Victims’ representations also refer to conduct that may amount to torture (such as beating) and arbitrary arrests.Footnote 61

31. Alleged sexual violence underlying the alleged coercive acts: numerous victims’ representations recount frequent occurrence of incidents of rape and other forms of sexual violence.Footnote 62 One victim representation claims that most of the women consulted, who are now refugees in Bangladesh, had been subjected to rape(s), sexual harassment, and other forms of sexual violence whilst in Myanmar.Footnote 63 Other victims’ representations report that victims were subject to gang rapes and mutilations.Footnote 64 One victims’ representation also refers to third-gender persons who were reportedly subjected to rape and sexual violence.Footnote 65

32. Alleged destruction of houses and other buildings underlying the alleged coercive acts: most victims’ representations mention that in addition to the aforesaid violent acts committed against them or their family members, their property were destroyed or taken away from them. Victims’ representations also refer to incidents of burning of their homes, as well as destruction of schools and mosques, either during the attacks to their villages or while they were on their way to Bangladesh.Footnote 66 They also claim that their livestock and their property was taken away from them. Some victims’ representations mention that, in some instances, entire villages were destroyed.Footnote 67

33. Alleged discriminatory intent: all victims’ representations assert that these aforementioned alleged acts were committed on grounds of their ethnicity and religion, namely Rohingya and Muslims.Footnote 68 Furthermore, the Registry states that victims ‘insisted to convey to the ICC Judges how important it is to them to have an acknowledgement that the Rohingya as a recognised and recognisable group by virtue of a common culture, identity and religion were victims of atrocious crimes exclusively based on their ethnicity and religion’.Footnote 69

C. Views on gravity and the interests of justice

1. Gravity

34. Victims’ representations refer to the gravity of the crimes. Some identify those that are allegedly most responsible and some describe the scale of the crimes, the elements of brutality and cruelty of the alleged conduct.

35. The Registry reported that the vast majority of victims’ representations identified the Tatmadaw, the Border Guard Police (‘BGP’), the Myanmar Government, Myanmar Police Force (‘MPF’) and other local authorities, as well as members of the local population and Buddhist monks, as being among those who were allegedly responsible for the acts and conduct described above.Footnote 70 Some victims have specifically identified high-ranking alleged perpetrators.Footnote 71 Victims also claimed that during the alleged attacks, the alleged perpetrators referred to them in a derogatory and discriminatory manner.Footnote 72

36. Victims’ representations refer to the impact of the conduct, particularly how people were forced to flee to Bangladesh.Footnote 73 Victims also state that, as a result of the deportation, many families have been separated.Footnote 74 Victims, particularly Rohingya youth, also claim that they need access to education in order to have a future.Footnote 75

37. As noted above, victims’ representations mention that perpetrators purposely targeted children and that sexual violence, often committed in a brutal manner, was prevalent.

2. Interests of justice

38. According to the Registry, victims unanimously insist that they want an investigation by the Court.Footnote 76 The Registry reports that many of the consulted alleged victims ‘believe that only justice and accountability can ensure that the perceived circle of violence and abuse comes to an end and that the Rohingya can go back to their homeland, Myanmar, in a dignified manner and with full citizenship rights’.Footnote 77 Victims have also expressed their willingness and eagerness to engage with the ICC and ‘explained that bringing the perpetrators to justice within a reasonable time is crucial in preventing future crimes from being committed and for the safe and dignified return of the Rohingya to their homeland Myanmar’.Footnote 78 One victims’ representation states: ‘We are educated, we read about the ICC, about what the Court can do and what it cannot. Despite its limitations, the ICC is the only Court that can look into what happened to the Rohingya and we strongly believe that if the Court opens an investigations, the perpetrators will think twice about committing these crimes again’.Footnote 79

39. Despite the challenges faced during the present article 15 process, the Registry states that the process has been welcomed by the victims.Footnote 80 However, the Registry also conveys the victims’ message that proceedings should be expeditious, evidence should be collected as soon as possible, and victims should be protected as they fear retaliation if they cooperate with the Court.Footnote 81 The Registry also reports that victims wish direct interaction with the ICC, including judges, who victims state ‘should come here and see for themselves how the Rohingya are and how they live’.Footnote 82

V. Jurisdiction

40. The Chamber recalls that, for conduct to fall within the jurisdiction of the Court, it must: (i) fall within the category of crimes set out in article 5 and defined in articles 6 to 8 bis of the Statute (jurisdiction ratione materiae); (ii) fulfil the temporal conditions specified in article 11 of the Statute (jurisdiction ratione temporis); and (iii) meet one of the two requirements contained in article 12(2) of the Statute (jurisdiction ratione loci or ratione personae).Footnote 83

41. In her Request, the Prosecutor seeks authorisation to investigate, specifically, ‘crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court in which at least one element occurred on the territory of Bangladesh, and which occurred within the context of two waves of violence in Rakhine State on the territory of Myanmar, as well as any other crimes which are sufficiently linked to these events.’Footnote 84 Accordingly, the Chamber will assess whether or not in light of the applicable law and with regard to the information provided in the Request, the criteria of territorial jurisdiction, material jurisdiction and temporal jurisdiction are satisfied.

A. Jurisdiction ratione loci

1. Applicable law

42. Article 12(2)(a) of the Statute establishes that the Court may exercise its jurisdiction in the event of a State Party referral (article 13(a) of the Statute) or as a result of the Prosecutor's proprio motu initiation of an investigation (article 13(c) of the Statute):

[…] if one or more of the following States are Parties to this Statute or have accepted the jurisdiction of the Court in accordance with paragraph 3:

(a) The State on the territory of which the conduct in question occurred or, if the crime was committed on board a vessel or aircraft, the state of registration of that vessel or aircraft;

(b) The State of which the person accused of the crime is a national.Footnote 85

43. In the context of the situation in Bangladesh/Myanmar, the Chamber recalls that Pre-Trial Chamber I found that ‘the Court may assert jurisdiction pursuant to article 12(2)(a) of the Statute if at least one element of a crime within the jurisdiction of the Court or part of such a crime is committed on the territory of a State Party to the Statute’.Footnote 86 For the reasons given below, the Chamber agrees with the conclusion of Pre-Trial Chamber I that the Court may exercise jurisdiction over crimes when part of the criminal conduct takes place on the territory of a State Party.

44. Article 12(2)(a) of the Statute has been widely interpreted as an expression of the territoriality principle. To date, the application of this principle in most of the situations and related cases before the Court has generally been uncontroversial. Most of them were territorially confined within the boundaries of a single State Party.Footnote 87

45. The facts underlying the Request compel the Chamber, however, to interpret the principle of territoriality further. In particular, the question arises as to whether the Court may exercise its jurisdiction over crimes that occurred partially on the territory of a State Party and partially on the territory of a non-State party. In order to answer this question two issues must be addressed: first, the Chamber must ascertain the exact meaning of the term ‘conduct’ in article 12(2)(a) of the Statute and, second, whether article 12(2)(a) of the Statute requires that all conduct must take place in the territory of a State Party.

i. Meaning of the term ‘conduct’ in article 12(2)(a) of the Statute

46. In addressing the first issue, the Chamber begins by assessing the textual interpretation of the term ‘conduct’ in article 12(2)(a) of the Statute. An assessment of the plain meaning of the word ‘conduct’ indicates that it is best defined as a form of behaviour,Footnote 88 encompassing more than the notion of an act.Footnote 89 This understanding of ‘conduct’ is supported by the French version of article 12(2)(a) of the Statute, which uses the word ‘comportement’.Footnote 90 Nonetheless, apart from suggesting that it must be more than a mere act, the plain meaning of conduct does not indicate what it is that must take place on the territory of one or more State Parties.

47. In this regard, the contextual interpretation discussed below provides some clarity. As part of assessing the immediate context of the term ‘conduct’ in this provision, a comparison between the terms ‘crime’ and ‘conduct’ as they appear in article 12(2)(a) of the Statute offers some guidance.

48. Article 12(2)(a) of the Statute uses the term ‘conduct’, when referring to State territory; and ‘crime’, when referring to vessels and aircrafts registered in a State. At first glance, the term ‘conduct’ appears to be distinct from the term ‘crime’. However, the use of both ‘conduct’ and ‘crime’ in the language of article 12(2)(a) of the Statute indicates that the term conduct, short of crime, is a reference to criminal conduct absent legal characterisation. The travaux préparatoires offer no explanation as to why the drafters selected to use a different word in relation to vessel/aircraft. There is no apparent reason why the threshold for territorial jurisdiction would be different based on whether the location of the conduct/crime is on land or vessel/aircraft. In the absence of any explanation as to why the drafters chose different words for the determination of territorial jurisdiction, a contextual reading of the provision allows an inference to be drawn that the juxtaposition of ‘conduct in question’ on the territory of a State immediately before ‘crime’ committed on board a vessel or aircraft means that the notions of ‘conduct’ and ‘crime’ in article 12(2)(a) of the Statute have the same functional meaning.

49. A contextual interpretation of the term involving a comparison with other provisions of the Statute using the same term also renders the same conclusion. For instance, use of the term conduct in article 20 is understood to refer to conduct absent legal characterisation.Footnote 91 For these reasons, the word is used in a factual sense, capturing the actus reus element underlying a crime subject to the jurisdiction ratione materiae of the Court.

50. Further, depending on the nature of the crime alleged, the actus reus element of conduct may encompass within its scope, the consequences of such conduct. For instance, the consequence of an act of killing is that the victim dies. Both facts concerning the act and the consequence (i.e. the killing and the death) are required to be established.

51. In respect of certain crimes within the Statute, the particular consequence may be that the victim behaves, or is caused to behave, in a certain way as a result of conduct attributable to the alleged perpetrator. The negative corollary is that, should those consequences not follow from the conduct of the perpetrator, the crime cannot be said to have occurred (although the suspect's conduct may constitute attempt).

52. The legal elements of the crime of deportation require, inter alia, that the ‘perpetrator deport […] by expulsion or other coercive acts’. This element may be carried out by the perpetrator either by physically removing the deportees or by coercive acts that cause them to leave the area where they were lawfully present.Footnote 92 In such a situation, the victims’ behaviour or response as a consequence of coercive environment is required to be established for the completion of the crime. If the victims refused to leave the area despite the coercive environment or they did not cross an international border, it would constitute forcible transfer or an attempt to commit the crime of deportation.

53. In the present Request, it is alleged that the coercive acts of the perpetrators, which took place in Myanmar, have forced the Rohingya population to cross the border into Bangladesh. The Prosecutor avers that the crime of deportation was completed when the victims left the area where they were lawfully present and fled to Bangladesh as a result of coercive acts and a coercive environment. Accordingly, it could be concluded that part of the actus reus of the crime of deportation occurred in the territory of Bangladesh.

ii. Location of the conduct

54. A second issue requiring the analysis of the Chamber is whether article 12(2)(a) of the Statute requires that all the conduct takes place in the territory of one or more State Parties.

55. As noted above, the wording of article 12(2)(a) is generally accepted to be a reference to the territoriality principle. In order to interpret the meaning of the words ‘on the territory of which the conduct occurred’, it is instructive to look at what territorial jurisdiction means under customary international law, as this would have been the legal framework that the drafters had in mind when they were negotiating the relevant provisions.Footnote 93 It is particularly significant to look at the state of customary international law in relation to territorial jurisdiction, as this is the maximum the States Parties could have transferred to the Court.

56. Customary international law does not prevent States from asserting jurisdiction over acts that took place outside their territory on the basis of the territoriality principle. A brief survey of State practice reveals that States have developed different concepts for a variety of situations that enables domestic prosecuting authorities to assert territorial jurisdiction in transboundary criminal matters, such as:

(i) the objective territoriality principle according to which the State may assert territorial jurisdiction if the crime is initiated abroad but completed in the State's territory;Footnote 94

(ii) the subjective territoriality principle, according to which the State may assert territorial jurisdiction if the crime has been initiated in the State's territory but completed abroad;Footnote 95

(iii) the principle of ubiquity, according to which the State may assert territorial jurisdiction if the crime took place in whole or in part on the territory of the State irrespective of whether the part occurring on the territory is a constitutive element of the crime;Footnote 96

(iv) the constitutive element theory, according to which a State may assert territorial jurisdiction if at least one constitutive element of the crime occurred on the territory of the State;Footnote 97 and

(v) the effects doctrine, according to which the State may assert territorial jurisdiction if the crime takes place outside the State territory but produces effects within the territory of the State.Footnote 98

57. It is safe to assume that all the states reviewed are of the view that their domestic legislation on territorial jurisdiction over cross-boundary conduct are in conformity with international law (opinio juris).

58. Two conclusions follow from this: first, under customary international law, States are free to assert territorial criminal jurisdiction, even if part of the criminal conduct takes place outside its territory, as long as there is a link with their territory. Second, States have a relatively wide margin of discretion to define the nature of this link.

59. Article 12(2)(a) of the Statute does not specify under which circumstances the Court may exercise jurisdiction over transboundary crimes on the basis of the territoriality principle. However, it would be wrong to conclude that States intended to limit the Court's territorial jurisdiction to crimes occurring exclusively in the territory of one or more States Parties. Moreover, reading article 12(2)(a) of the Statute in this manner would go against the principle of good faith (including effective) interpretation.

60. Indeed, when States delegate authority to an international organisation they transfer all the powers necessary to achieve the purposes for which the authority was granted to the organisation. In this respect, it is recalled that the Statute contains a number of war crimes that take place in international armed conflicts. If the Court could not exercise its jurisdiction over crimes that were partly committed in the territory of a non-State party, this would mean that the Court could not hear cases involving war crimes committed in international armed conflicts involving non-States Parties. There is no indication anywhere in the Statute that the drafters intended to impose such a limitation. This is confirmed by the fact that the States Parties deemed it necessary to include such a limitation in article 15 bis (5) of the Statute in relation to the crime of aggression. It follows from this that, since the States Parties did not explicitly restrict their delegation of the territoriality principle, they must be presumed to have transferred to the Court the same territorial jurisdiction as they have under international law.

61. The only clear limitation that follows from the wording of article 12(2)(a) of the Statute is that at least part of the conduct (i.e. the actus reus of the crime) must take place in the territory of a State Party. Accordingly, provided that part of the actus reus takes place within the territory of a State Party, the Court may thus exercise territorial jurisdiction within the limits prescribed by customary international law.

2. Conclusion

62. The alleged deportation of civilians across the Myanmar-Bangladesh border, which involved victims crossing that border, clearly establishes a territorial link on the basis of the actus reus of this crime (i.e. the crossing into Bangladesh by the victims). This is the case under the objective territoriality principle, the ubiquity principle, as well as the constitutive elements approach. The present situation therefore falls well within the limits of what is permitted under customary international law. Under these circumstances, the Chamber does not otherwise deem it necessary to formulate abstract conditions for the Court's exercise of territorial jurisdiction for all potentially transboundary crimes contained in the Statute.

B. Jurisdiction ratione materiae

1. Alleged contextual elements of crimes against humanity

i. Applicable law

63. The chapeau of article 7 of the Statute sets out the contextual elements of crimes against humanity as ‘a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population’.Footnote 99 Article 7(2)(a) of the Statute further defines an ‘attack directed against any civilian population’ as ‘a course of conduct involving the multiple commission of acts referred to in [article 7(1) of the Statute] against any civilian population, pursuant to or in furtherance of a State or organizational policy to commit such attack’.Footnote 100 As regards the elements ‘attack’,Footnote 101 ‘civilian population’,Footnote 102 ‘policy’Footnote 103 and ‘widespread or systematic’,Footnote 104 the Chamber refers to the established case law of the Court. Lastly, any of the underlying crimes must have been committed as part of the attack.

ii. Alleged contextual facts

a. Background

64. The Prosecutor submits that in Myanmar's political and constitutional context the Tatmadaw essentially dominates the government.Footnote 105 The Prosecutor also states that in Myanmar, but more specifically in Rakhine State, there is systematic discrimination, institutionalised oppression, human rights violations, and hostility against the Rohingya.Footnote 106 The Prosecutor alleges that the government has discriminated against this ethnic group for decades, by implementing policies and laws that deny citizenship to persons of this ethnic group, ‘rendering them stateless’.Footnote 107 The Prosecutor also states that the government of Myanmar has violated fundamental rights of the Rohingya people, including by restricting their movement between townships.Footnote 108

65. The Prosecutor further submits that on previous occasions the government of Myanmar forced many Rohingya to flee Myanmar (including in 1978, 1991–1992, and 2012–2013).Footnote 109 She also states that there was increasing Buddhist nationalism and use of hate speech against Muslims in general and the Rohingya in particular.Footnote 110 Within this context, the Prosecutor submits that ARSA emerged and launched attacks against government posts in Rakhine State.Footnote 111 Consequently, the Prosecution states that the Tatmadaw launched ‘clearance operations’ that resulted in the 2016 and 2017 waves of violence, which are the subject of this Request.Footnote 112

66. According to the supporting material, including the report of the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar (the ‘UNFFM’),Footnote 113 MyanmarFootnote 114 and more specifically Rakhine State are ethnically diverse,Footnote 115 with the Rohingya forming the second largest group in Rakhine State.Footnote 116 It is reported that, unlike the vast majority of the population in Myanmar, who are almost 90% Buddhist,Footnote 117 the Rohingya are predominantly Muslim.Footnote 118 Further, according to the supporting material, the Rohingya also have their own language, which is a spoken language, with no agreed written script.Footnote 119

67. According to the information on the record, the Rohingya have gradually been deprived of citizenship through legislation,Footnote 120 and via administrative decisions applying the legislation.Footnote 121 For example, it is reported that the Rohingya are not entitled to full citizenship by birth.Footnote 122 The supporting material indicates that the Rohingya have allegedly been subjected to severe violations of their human rights for decades,Footnote 123 including the right to freedom of movement,Footnote 124 marriage,Footnote 125 and other aspects of family life.Footnote 126

68. The supporting material, including reports by Amnesty InternationalFootnote 127 and Human Rights Watch (hereinafter ‘HRW’),Footnote 128 refers in particular to waves of violence in June and October 2012, involving confrontations between Buddhist and other inhabitants of Rakhine State on one side, and Rohingya and other Muslim groupsFootnote 129 on the other.Footnote 130 The available information suggest that acts of violence were perpetrated by members of both communities,Footnote 131 but that most of the internally displaced were Muslim, and among them, most of them Rohingya.Footnote 132

69. The supporting material suggests that the violence in Rakhine was partly inter-communal, fuelled by an increasing anti-Muslim sentiment propagated by nationalist Buddhist groups and individuals who portrayed the Rohingya and Muslims as a ‘threat to race and religion’.Footnote 133 According to the supporting material, members of the Myanmar security forces (the Tatmadaw, the police and the Border Area Immigration Control Headquarters, known as the NaSaKa) allegedly participated in the attacks, supported them, or failed to stop them.Footnote 134

70. According to the available information, following the 2012 waves of violence, the restrictions against the Rohingya, as well as other Muslim groups, were tightened and expanded, particularly in terms of their freedom of movement.Footnote 135 The available information suggests that the authorities sought to segregate the two communities in order to prevent further violence and reduce tensions.Footnote 136 However, it is alleged that the restrictions, which involved limitations on freedom of movement, travel permits, school segregation, and confinement to internal displacement camps, discriminately and disproportionately targeted the Muslim communities.Footnote 137

b. Systematic or widespread attack directed against any civilian population

71. The Prosecutor submits that there is a reasonable basis to believe that the alleged crimes which form the object of the Request were committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against a civilian population.Footnote 138 She states that the alleged crimes were committed in the context of two waves of violence, starting on 9 October 2016 (‘2016 wave of violence’) and on 25 August 2017 (‘2017 wave of violence’), which constitute—either in combination or separately—an ‘attack’ within the meaning of article 7 of the Statute.Footnote 139 The Prosecutor contends that the available information supports allegations that the attack was widespread, particularly given the high number of peopled reportedly killed (10,000) and deported (700,000) during the 2017 wave of violence.Footnote 140 She also argues that the attack was systematic, given the high-degree of organisation and amount and type of State resources used to commit it.Footnote 141 The Prosecutor further submits that there is a link between the identified crimes of deportation and inhumane attacks and the attack.Footnote 142 With respect to the 2016 wave of violence, she states that there are striking analogies between the two waves, suggesting that the crimes committed in 2016 also meet the widespread/systematic threshold.Footnote 143

72. In her Request, the Prosecutor claims that there is information about acts of violence allegedly committed by ARSA and of armed confrontations between ARSA and the Tatmadaw. She states that, if authorised to investigate, her office will keep these allegations under review, to determine whether crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court were committed in the territory of a State Party.Footnote 144

73. As regards the 2016 wave of violence, the Prosecutor states that on 9 October 2016 and on 12 November 2016, following ARSA attacks, the Tatmadaw, together with other governmental forces and non-Rohingya civilians, started ‘clearance operations’ in Rakhine State that resulted in the use of violence against Rohingya. It is estimated that 87,000 persons fled to Bangladesh as a result.Footnote 145

74. According to the information on the record, ARSA emerged as a response to the events of 2012.Footnote 146 It is reported that on 9 October 2016, ARSA launched an attack on three border police posts in Maungdaw and Rathedaung townships, resulting in the death of nine police officers.Footnote 147 The supporting material, including a report by the OHCHR,Footnote 148 indicates that these events marked the starting point of an escalation in the scale and severity of the violence perpetrated by Myanmar security forces against the Rohingya.Footnote 149

75. The supporting material suggests that, in the course of these operations, the Tatmadaw and the police, most notably the BGP, with the participation of some non-Rohingya civilians, murdered, tortured, raped, sexually assaulted, mutilated, imprisoned, and severely deprived Rohingya men and women of their physical liberty.Footnote 150 The ‘clearance operations’ reportedly lasted until January/February 2017 and caused as many as 87,000 Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh.Footnote 151 It is estimated that a further 20,000 to 22,000 people remained internally displaced.Footnote 152

76. In relation to the 2017 wave of violence, the Prosecutor submits that following ARSA attacks on 26 August 2017, the Tatmadaw together with other governmental forces and non-Rohingya civilians, again launched ‘clearance operations’ of Rohingya villages, but this time on a larger scale. During this wave of violence, hundreds of villages were destroyed; thousands of persons were killed, raped and injured. As a result, she estimates over 700,000 Rohingya were deported to Bangladesh.Footnote 153

77. According to the information on the record, on 25 August 2017 ARSA allegedly launched a series of coordinated attacks and further clashes were reported over the next several days.Footnote 154 The aim of the attacks was reportedly to respond to what ARSA viewed as an ‘increased oppression of the Rohingya’ and to draw attention to their situation.Footnote 155 It is reported that, following the aforesaid attacks, the Government of Myanmar declared ARSA a ‘terrorist organisation’ and launched ‘clearance operations’ in hundreds of villages across Maungdaw, Buthidaung and Rathedaung townships.Footnote 156 In the course of these operations, the Tatmadaw and other security forces, often with the participation of non-Rohingya civilians, allegedly murdered, tortured, raped, sexually assaulted, mutilated, and imprisoned or otherwise severely deprived Rohingya men and women of their physical liberty.Footnote 157

78. The supporting material suggests that the clearance operations during the 2016 wave of violence were mostly limited to Maungdaw Township.Footnote 158 In relation to the clearance operations during the 2017 wave of violence, documents including a report by Médecins Sans Frontières (hereinafter ‘MSF’),Footnote 159attacks were allegedly carried out in hundreds of villages across the Maungdaw, Buthidaung, and Rathedaung Townships.Footnote 160

79. PILPG and Kaladan Press Network (hereinafter ‘Kaladan’)Footnote 161 report that the focus of the clearance operations were village raids.Footnote 162 Organisations that have conducted investigations in the area, including UNFFM, OHCHR, and Xchange,Footnote 163 report that the village raids were allegedly perpetrated by Tatmadaw soldiers, often accompanied by local civilians,Footnote 164 and at times accompanied by the BGP.Footnote 165 According to the supporting material, these assaults were full-fledged military operations.Footnote 166

80. It is reported that most of the attacked villages were comprised almost exclusively of Rohingya.Footnote 167 It is further reported that in villages with mixed ethnic population, the non-Rohingya population remained unharmed.Footnote 168 According to the information submitted, including a report by Physicians for Human Rights (the ‘PHR’),Footnote 169 the attackers referred to the victims in a derogatory and discriminatory manner during the attacks.Footnote 170

81. The supporting material suggests that the village raids were carried out following the same pattern.Footnote 171 Documents, including research by HRWFootnote 172 report that, after entering villages, the Tatmadaw and other security forces often shot indiscriminately at villagers.Footnote 173 As a result of these indiscriminate shootings, numerous Rohingya, including many children,Footnote 174 were reportedly killed or injured, many whilst fleeing.Footnote 175

82. Several village raids reportedly resulted in mass killings with hundreds of Rohingya dead,Footnote 176 many of them allegedly buried in mass graves.Footnote 177 According to the supporting material, such massacres allegedly occurred at least in Min Gyi, Maung Nu, Chut Pyin, Gu Dar Pyin and Koe Tan Tauk village tract, Shila Khali and Tong Bazar.Footnote 178

83. The available information further suggests that, as part of the clearance operations, Rohingya houses in northern Rakhine were systematically burnt down,Footnote 179 leading to the death of numerous RohingyaFootnote 180 and the destruction of their homes.Footnote 181 It is reported that where houses were not burned, they were destroyed by other means.Footnote 182 According to UNOSAT, 392 settlements were affected between 25 August 2017 and 18 March 2018 and approximately 37,700 structures were destroyed.Footnote 183

84. Estimates in the supporting material indicate that 6,097 sexual and gender based incidents have been reported between 27 August 2017 and 25 March 2018.Footnote 184 The majority of the alleged rapes occurred during village raids.Footnote 185

85. The clearance operations allegedly also involved the systematic abduction of girls and women ‘of fertile age’ to military and police compounds and bases, where they were detained and raped for extended periods of time,Footnote 186 and often subsequently killed.Footnote 187 Most alleged rapes were reportedly carried out by the Tatmadaw, although members of the BGP, the MPF and local civilians equally committed these acts.Footnote 188

86. Although the majority of alleged rapes concern women and girls, the Chamber notes that the supporting material also refers to incidents of rape, forced nudity, forced witnessing of rape, sexual violence humiliation of men during the 2017 clearance operations,Footnote 189 in particular while in detention.Footnote 190 Moreover, the available information suggests that in some instances ‘Hijra’ individuals, who are defined as third-gender persons, transgender women, and intersex persons in South Asia who were assigned a masculine gender at birth’,Footnote 191 were reportedly targeted for rape and sexual violence.Footnote 192

87. The supporting material further indicates that at least between August 2016 and October 2017, Myanmar authorities allegedly carried out mass arrests of Rohingya, often in order to assess whether they had ties with or knowledge of ARSA.Footnote 193 In particular men and boys between the age of 17 and 45,Footnote 194 at times as young as 15,Footnote 195 and influential community members such as village elders, religious leaders and teachers, were allegedly targeted.Footnote 196

88. According to available information, numerous Rohingya were killed or injured en route to Bangladesh.Footnote 197 MSF reports that 13.4% of violent deaths occurred during the period between their displacement from their village to their arrival in Bangladesh.Footnote 198

89. In light of the allegations described above, it is reported that over 700,000 Rohingya allegedly fled to Bangladesh.Footnote 199 This has been reported to be ‘one of the fastest refugee exoduses in modern times [which] has created the largest refugee camp in the world’.Footnote 200

c. Alleged State policy

90. The Prosecutor submits that the alleged crimes against Rohingya were ‘carried out pursuant to a State policy to attack the Rohingya civilian population’. The Prosecution identifies the following as perpetrators of the crimes: the Tatmadaw (Myanmar defence forces comprising the army, navy and air force), the MPF and the BGP. The Prosecutor also submits that non-Rohingya civilians may have also been involved in the commission of the crimes. The Prosecutor avers that the existence of a policy is suggested by: (a) patterns of violence, (b) institutionalised oppression, (c) public statements of high officials, (d) and the failure to bring those responsible to justice or to prevent or deter further crimes.Footnote 201

91. According to the supporting material, members of the Tatmadaw led the 2016 and 2017 ‘clearance operations’.Footnote 202 Other security forces such as the BGP and the MPF reportedly operated jointly with the Tatmadaw during clearance operations.Footnote 203 The available information further suggests that non-Rohingya civilians (including Buddhist monks), may also have taken part in village raids conducted during the clearance operations.Footnote 204 The supporting material suggests that they participated in consistent ways, carrying out specific functions.Footnote 205

iii. Conclusion

92. Based on the above, the Chamber accepts that there exists a reasonable basis to believe that since at least 9 October 2016 widespread and/or systematic acts of violence may have been committed against the Rohingya civilian population, including murder, imprisonment, torture, rape, sexual violence, as well as other coercive acts, resulting in their large-scale deportation. Given that there are many sources indicating the heavy involvement of several government forces and other state agents, there exists reasonable basis to believe that there may have been a state policy to attack the Rohingya.

93. In reaching these conclusions, the Chamber has taken into account the allegations underpinning the 2016 and 2017 waves of violence, which took place on the territory of Myanmar. In this regard, the Chamber wishes to make the following clarification: while the Court is not permitted to conduct proceedings in relation to alleged crimes which do not fall within its jurisdiction, it ‘has the authority to consider all necessary information, including as concerns extra-jurisdictional facts for the purpose of establishing crimes within its competence’.Footnote 206 In other words, the Court is permitted to consider facts which fall outside its jurisdiction in order to establish, for instance, the contextual elements of the alleged crimes. In the situation at hand, the Chamber has considered the information regarding alleged coercive acts (including alleged murder, forcible transfer of population, imprisonment, torture, rape or persecution) which have allegedly occurred entirely on the territory of Myanmar for the purpose of evaluating whether the Prosecutor has a reasonable basis to believe that an attack against the Rohingya civilian population pursuant to a State policy may have occurred. In other words, although the Court does not have jurisdiction over these alleged crimes per se, it considered them in order to establish whether or not the contextual elements of crimes against humanity may have been present.

2. Alleged underlying acts constituting crimes against humanity

94. In her Request, the Prosecutor submits that there is a reasonable basis to believe that, since 9 October 2016, members of the Tatmadaw jointly with the BGP and the MPF, with some participation of non-Rohingya civilians, and other Myanmar authorities, committed crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court, of which at least one element occurred on the territory of Bangladesh.Footnote 207

95. According to the Prosecutor these include crimes against humanity of deportation (article 7(1)(d) of the Statute), other inhumane acts (article 7(1)(k) of the Statute), and persecution on grounds of ethnicity and/or religion (article 7(1)(h) of the Statute).Footnote 208 She however states that further crimes may be identified during an authorised investigation.Footnote 209

96. In the following, the Chamber will focus its assessment on the alleged crimes of deportation and persecution, in order to establish whether the threshold under article 15 of the Statute is met. If this is the case, there is no need to assess whether other crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court may have been committed, even though such alleged crimes could be part of the Prosecutor's future investigation.

i. Applicable Law

a. Deportation

97. Deportation or forcible transfer of a population, within the meaning of article 7(1)(d) of the Statute, are committed when:Footnote 210

1. The perpetrator deported or forcibly transferred without grounds permitted under international law, one or more persons to another State or location, by expulsion or other coercive acts.

2. Such person or persons were lawfully present in the area from which they were so deported or transferred.

98. The forcible displacement of individuals must occur without grounds permitted under international law. While it is for the Prosecutor to prove that this is the case,Footnote 211 the Chamber notes that, under international law, deportation of a State's nationals as well as the arbitrary or collective expulsion of aliens is generally prohibited.Footnote 212 International humanitarian law permits displacement in specific circumstances, where the security of the population or imperative military reasons so require.Footnote 213 However, this is not the case where the humanitarian crisis that caused the displacement is the result of an unlawful activity.Footnote 214

99. The lawful presence of a person must be assessed on the basis of international law,Footnote 215 and should not be equated with the requirement of lawful residence.Footnote 216

b. Persecution

100. Persecution, within the meaning of article 7(1)(h) and (2)(g)Footnote 217 of the Statute,Footnote 218 is committed, either through a single act or a series of acts,Footnote 219 when:

1. The perpetrator severely deprived, contrary to international law,Footnote 220 one or more persons of fundamental rights.

2. The perpetrator targeted such person or persons by reason of the identity of a group or collectivity or targeted the group or collectivity as such.

3. Such targeting was based on political, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious, gender as defined in Article 7, paragraph 3, of the Statute, or other grounds that are universally recognized as impermissible under international law.

4. The conduct was committed in connection with any act referred to in Article 7, paragraph 1, of the Statute or any crime within the jurisdiction of the Court.Footnote 221

101. Not every infringement of human rights amounts to persecution, but only a ‘severe deprivation’ of a person's ‘fundamental rights contrary to international law’ (emphasis added). Fundamental rights may include a variety of rights, whether derogable or not, such as the right to life, the right not to be subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, freedom of expression, freedom of assembly and association and the right to education.Footnote 222

102. The targeted group or collectivity must be identifiable by any of the characteristics mentioned in article 7(2)(g) of the Statute. In assessing whether a group is identifiable, a mixed approach may be adopted,Footnote 223 considering both objective and subjective criteria.

103. Based on objective considerations, an ethnic group may be defined as a group whose members share a common language and culture.Footnote 224 A religious group may be defined as one ‘whose members share the same religion, denomination or mode of worship’.Footnote 225 As regards the subjective criteria, the perception of the group by the perpetratorFootnote 226 as well as the perception and self-identification of the victims may be considered.Footnote 227

ii. Alleged facts

a. Deportation

104. Pursuant to the information on the record, as a result of the clearance operations described above,Footnote 228 many Rohingya were forced to flee to Bangladesh.Footnote 229 In particular, the supporting material suggests that as a result of the 2016 wave of violence, 87,000 RohingyaFootnote 230 were forced to flee to Bangladesh,Footnote 231 while others have reportedly been internally displaced, residing in camps with severe restrictions on freedom of movement and access to healthcare, education and livelihoods.Footnote 232

105. It is estimated that, following the 2017 wave of violence, approximately 700,000 Rohingya were forced to escape to Bangladesh.Footnote 233 Only 10% of the original Rohingya population allegedly remains in northern Rakhine State.Footnote 234 The supporting material further indicates that the majority of Rohingya arrived in Bangladesh during the peak of the 2017 clearance operations,Footnote 235 between 25 August and 31 December 2017.Footnote 236 A 2017 survey on Rohingya migration reports that of the 1,360 respondents interviewed following the 2017 wave of violence, 92% answered that they had suffered or witnessed a major incident prompting them to flee to Bangladesh.Footnote 237

106. While reliable numbers of the current Rohingya refugee population in Bangladesh are not available to the Chamber, UNHCR reported that 907,199 Rohingya lived in Bangladeshi refugee camps in January 2019,Footnote 238 with the largest camp in Cox's Bazar hosting over 700,000 people.Footnote 239

107. According to the material submitted, most of the Rohingya interviewed in refugee camps in Bangladesh wish to return to Myanmar,Footnote 240 but expressed concerns about their safety and citizenship rights.Footnote 241 Many stated that they would return only if they were treated with dignity, including respect for their religion, their ethnic identity, the return of their possessions, and a sustainable future for their children.Footnote 242

108. In light of the above, a reasonable prosecutor could believe that coercive acts towards the Rohingya forced them to flee to Bangladesh, which may amount to the crime against humanity of deportation.

b. Persecution

109. The Chamber is further satisfied that the Prosecutor could reasonably believe that the alleged coercive conduct leading to the Rohingya's deportation to Bangladesh was directed against an identifiable group or collectivity.Footnote 243 This is confirmed by victims representations that have indicated that they self-identify as belonging to the same group.Footnote 244 Further, based on the available information the Prosecutor could reasonably believe that the targeting may have been based on ethnic and/or religious grounds. It is for the investigation to determine whether or not this was actually the case. The Chamber reiterates the need to obtain further clarity on the contours of the group-identity in question as well as the basis of the alleged targeting.

iii. Conclusion

110. Upon review of the available information, the Chamber accepts that there exists a reasonable basis to believe that since at least 9 October 2016, members of the Tatmadaw, jointly with other security forces and with some participation of local civilians, may have committed coercive acts that could qualify as the crimes against humanity of deportation (article 7(1)(d) of the Statute) and persecution on grounds of ethnicity and/or religion (article 7(1)(h) of the Statute) against the Rohingya population.

111. As noted above, the Chamber does not consider it necessary to form any view in relation to the facts identified as relevant to the Prosecutor's submissions concerning the alleged crime of other inhumane acts. Nevertheless, the Chamber stresses that the Prosecutor is not restricted to investigating only the events mentioned in her Request, much less their provisional legal characterisation.

C. Jurisdiction ratione temporis

112. Pursuant to article 11 of the Statute, the Court may exercise jurisdiction over crimes committed after the entry into force of the Statute or, where a State has become party to the Statute later, after the entry into force of the Statute for that State.

113. The Chamber notes that Bangladesh ratified the Rome Statute on 23 March 2010,Footnote 245 and therefore, pursuant to article 126(2) of the Statute, the Statute entered into force for that State on 1 June 2010.

114. In light of the information submitted and allegations described above, the Chamber notes that alleged crimes have partially been committed on the territory of Bangladesh since at least 9 October 2016. Consequently, the Court may assert jurisdiction ratione temporis over those crimes.

VI. Admissibility

A. Complementarity

115. Article 17(1)(a)–(b) of the Statute provides, in the relevant part, that ‘[…] the Court shall determine that a case is inadmissible where: (a) the case is being investigated or prosecuted by a State which has jurisdiction over it, unless the State is unwilling or unable genuinely to carry out the investigation or prosecution; (b) the case has been investigated by a State which has jurisdiction over it and the State has decided not to prosecute the person concerned, unless the decision resulted from the unwillingness or inability of the State genuinely to prosecute’. The Chamber has taken note of the Prosecutor's submission in relation to the admissibility of potential cases arising out of the situation. Given the open-ended nature of the Request—there are at present no specific suspects or charges—and the general nature of the available information, the Chamber sees no need to conduct a detailed analysis, as this would be largely speculative.

116. Moreover, the Chamber has not received submissions from Myanmar on the issue of admissibility. Regardless of the question whether or not the Prosecutor should have notified Myanmar at this stage of the proceedings, the Chamber would receive and entertain an application by the Prosecutor, should Myanmar ask for deferral on the basis of article 18(2) of the Statute within one month of the issuing of the present decision. Moreover, specific challenges to the admissibility of specific cases can be brought at a later stage, pursuant to article 19 of the Statute.

117. The Chamber therefore does not consider it necessary to assess complementarity at this point in time. It suffices to note that, on the basis of the currently available information, there is no indication that any potential future case would be inadmissible.

B. Gravity

118. With respect to the gravity of the situation at hand, the Chamber is of the view that the mere scale of the alleged crimes and the number of victims allegedly involved—according to the supporting material, an estimated 600,000 to one million Rohingya were forcibly displaced from Myanmar to neighbouring Bangladesh as a result of the alleged coercive actsFootnote 246—clearly reaches the gravity threshold.

C. The interests of justice

119. As regards the interests of justice, the Prosecutor has stated that she ‘has identified no substantial reasons to believe that an investigation into the situation would not be in the interests of justice’Footnote 247 and the Chamber has no reason to disagree with this assessment. This view is reinforced by the fact that, according to the Registry's Final Consolidated Report, ‘all victims representations state that the victims represented therein want the Prosecutor to start an investigation in the Situation.’Footnote 248

VII. The scope of the authorised investigation

120. The Prosecutor requests authorisation to proceed with the investigation into crimes allegedly committed since 9 October 2016, in the context of the 2016 and 2017 waves of violence which occurred in Rakhine State, Myanmar, and any other crimes which are sufficiently linked to these events, where at least one element of the crime occurred on the territory of Bangladesh.Footnote 249 The Prosecutor makes a number of specific submissions regarding the material and temporal scope of the investigation, as follows.

121. Regarding the material scope, she submits that the incidents identified in her Request are ‘examples of relevant criminality within the situation’ and that the Chamber should not limit the scope of the authorised investigation to these acts or incidents, but should authorise an investigation into the situation as a whole.Footnote 250 Similarly, she highlights that while the Request focuses on crimes allegedly committed by Myanmar authorities and some non-Rohingya civilians, she is aware of a number of acts of violence allegedly committed by ARSA. She submits that, if the authorisation to investigate is granted, she will keep these allegations under review, together with any allegations that an armed conflict may have existed between Myanmar and ARSA.Footnote 251

122. Regarding the temporal scope, the Prosecutor submits that the environment in Myanmar remains volatile and she specifically requests that the authorisation extend also to ‘any alleged crimes that may be committed and/or completed after the filing of [the] Request, provided that they occur within the context of the waves of violence […] or are sufficiently linked to these events’.Footnote 252

123. In what follows, the Chamber will set out the parameters of the authorised investigation in terms of territorial, material and temporal scope.

A. Territorial scope of the investigation (ratione loci)

124. The Chamber recalls its determination regarding jurisdiction ratione loci where it found that the Court can exercise jurisdiction where a part of the actus reus of a crime within the jurisdiction of the Court is committed on the territory of a State Party.Footnote 253 Consequently, the Chamber authorises the commencement of the investigation for crimes committed at least in part on the territory of Bangladesh.Footnote 254 Following this principle, the Prosecutor may also extend her investigation to alleged crimes committed at least in part on the territory of other States Parties, or States which would accept the jurisdiction of this Court in accordance with article 12(3) of the Statute, insofar as they are sufficiently linked to the situation as described in this decision.Footnote 255

125. Considering that article 12(2) of the Statute is formulated in the alternative,Footnote 256 the Prosecutor is authorised to investigate alleged crimes which fall within these parameters irrespective of the nationality of the perpetrators.Footnote 257

B. Material scope of the investigation (ratione materiae)

126. The Chamber authorises the commencement of the investigation in relation to any crime within the jurisdiction of the Court committed at least in part on the territory of Bangladesh, or on the territory of any other State Party or State making a declaration under article 12(3) of the Statute, if the alleged crime is sufficiently linked to the situation as described in this decision.Footnote 258 Noting the Prosecutor's submissions,Footnote 259 the Chamber wishes to emphasise that the Prosecutor is not restricted to the incidents identified in the Request and the crimes set out in the present decision but may, on the basis of the evidence gathered during her investigation, extend her investigation to other crimes against humanity or other article 5 crimes, as long as they remain within the parameters of the authorised investigation.Footnote 260 Similarly, the Prosecutor is also not restricted to the persons or groups of persons identified in the Request. The Chamber considers that, for the reasons that follow, such a limitation would be inconsistent with the object and purpose of article 15 of the Statute.