Within the economic domain of health technology assessment (HTA), health economic evaluations (HEEs) provide a framework for comparing the relative benefit and cost of different treatments over a long-term time horizon and from a national healthcare system and societal perspective. Competent authorities for pricing and reimbursement (P&R) of medicines and other HTA bodies around the world usually require HEEs from the marketing authorization holder (MAH) to inform their decisions/recommendations. Most of them have issued official guidelines for setting methodological standards and ensuring consistency, relevance, and transparency of submitted studies (1). The Canadian State of Ontario and Australia were pioneers in this field, followed by many other European countries (2–4). In principle, HEEs, possibly integrated with budget impact analyses (BIA), are deemed useful tools for pursuing allocative efficiency in healthcare systems, which is one of the value-pillars of the emerging value(s)-based health care approach in the European public debate (5). Currently, in few countries the results from HEEs are the main driver of decisions (e.g., England and Australia); whereas, more generally, they have a less explicit role within a multi-criteria decision-analysis approach (e.g., Germany, France, and Italy) (Reference Ngo6–Reference Jommi, Armeni, Costa, Bertolani and Otto8).

In Italy, the submission of HEEs within P&R applications is not mandatory, though officially encouraged by national regulations, especially for innovative products and medicines for orphan diseases (CIPE Resolution No. 3 of 1 February 2001) (9). The Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) is the national authority for both the pricing and the reimbursement of pharmaceuticals. For decision making, it relies on the advice of two expert committees (i.e., the Technical Scientific Committee—CTS and the Pricing and Reimbursement Committee—CPR), which are in turn supported by the AIFA internal staff and the HTA Secretariat. As such, the decisions about the reimbursement criteria and the relative reimbursement price of medicines are strictly related to each other and simultaneously taken according to a stepwise approach: first, the CTS decides on the eligibility for reimbursement coverage; then, the price of reimbursable medicines is negotiated between the CPR and the MAH. However, in case an agreement on price is not reached, the medicine will not get reimbursement by the Italian National Health Service (NHS). In the Italian system the reimbursement decisions are primarily driven by the therapeutic value of a medicine (also compared to existing alternatives), whereas cost-effectiveness and budget impact estimates may have a role in the price negotiations, together with other factors (Reference Villa, Tutone, Altamura, Antignani, Cangini and Fortino10). Despite the cost-effectiveness criterion was first introduced in 1997 (CIPE Resolution No. 5 of 30 January 1997) (11), and confirmed in the CIPE Resolution No. 3 of 1 February 2001 (9), as one of the criteria to be used for determining the prices of reimbursed medicines, it is only recently that HEEs have been formally integrated within the HTA activities performed at the central level by AIFA. In October 2016, the HEE Office was established to review the pharmacoeconomic studies submitted by manufacturers within the HTA process and provide pricing recommendations to the CPR based on cost-effectiveness results and budget impact estimates (12). Nevertheless, in Italy the cost-effectiveness criterion remains non-binding and rather vague to make P&R decisions; in fact, a cost-per-quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) threshold has never been explicitly defined, even due to the poor acceptance of the QALY as a unique measure of value. In 2018, AIFA was invited by the Ministry of Health to issue a position paper on these aspects, but it has not been following up on the request (13). Moreover, differently from many other countries, AIFA has never defined methodological requirements for the submission of HEEs. A proposal for guidelines for the economic evaluation of health interventions was issued in 2009 by the Italian Association of Health Economics (AIES) (14), but it has not officially been transposed into national guidelines. Therefore, in the Italian context, pharmaceutical companies face no explicit incentives to submit HEEs and anyhow, a high degree of discretion is granted in the choice of the study type and other methodological aspects. This could reasonably lead to scepticism toward the results of HEEs, given also the increasing use of electronic models for running pharmacoeconomic analyses, which implies many assumptions and other discretional choices (Reference Cornago, Li Bassi, De Compadri and Garattini15;Reference Hoffmann and von der Schulenburg16). However, when designed, analyzed, and interpreted appropriately, HEEs could be important sources of information for decision makers.

In a previous study by Russo (Reference Russo17), the quality of cost-effectiveness analyses (CEAs) submitted to AIFA was considered extremely heterogeneous. Poor transparency and clarity in reporting were the main issues raised by the author. To assess the current state of pharmacoeconomic submissions to AIFA, we reviewed the general characteristics and quality of HEEs through the application of a checklist adapted from Philips et al. (Reference Philips, Ginnelly, Sculpher, Claxton, Golder and Riemsma18). Future actions to enhance the quality of HEEs submitted for P&R decisions of medicines in Italy will be proposed.

Methods

For the purpose of this study, we reviewed all P&R dossiers submitted to AIFA by pharmaceutical companies from October 2016 (i.e., since the establishment of the HEE Office at AIFA) to December 2018. Dossiers were selected if related to (i) new medicinal products (never marketed before), (ii) orphan medicines, and (ii) new therapeutic indications. Each dossier might contain more than one pharmacoeconomic analysis for different therapeutic indications or subgroup populations. The general characteristics and quality of cost-effectiveness studies (if any) were further investigated. Our study focused only on HEEs, whereas the assessment of BIAs was excluded because it was outside the scope of this study.

General Description of HEEs Submitted to AIFA

In order to collect data systematically, a data extraction sheet identifying all relevant items which needed to be extracted from each study was developed. The list of items was selected from the ISPOR Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) Checklist, which includes items to be taken into account when reporting HEEs (Reference Husereau, Drummond, Petrou, Carswell, Moher and Greenberg19). The investigated variables were grouped into five categories: (a) general study characteristics: study population, setting, study perspective, type of comparator, time horizon, and discount rate; (b) health benefits: types of health outcomes and source of clinical and utility data; (c) costs: types of costs, source of resource, and unit cost data; (d) model structure (if any); and (e) sensitivity analysis. Any previous publication of the study in peer-reviewed journals was also highlighted.

Quality of HEEs Submitted to AIFA

The methodological quality of HEEs submitted to AIFA for P&R decisions was systematically assessed following a predefined checklist. Currently, there is no universally accepted instrument, but a number of checklists have been developed over time to guide the critical appraisal of model-based HEEs and the quality of their reporting (Reference Sculpher, Fenwick and Claxton20–Reference Adarkwah, van Gils, Hiligsmann and Evers25). Some authors have also proposed a scoring system, where the final score is indicative of a study's overall quality. However, the use of such system is currently not recommended because no valid and reliable scoring approach has been found (Reference Walker, Wilson, Sharma, Bridges, Niessen and Bass23).

In this study, we applied a customized checklist adapted from Philips et al. (Reference Philips, Ginnelly, Sculpher, Claxton, Golder and Riemsma18), which is routinely used by the AIFA HEE Office. The Philips' checklist was selected because it is specifically designed and widely suggested for the assessment of modeling studies (Reference Walker, Wilson, Sharma, Bridges, Niessen and Bass23;Reference Shemilt, Mugford, Byford, Drummond, Eisenstein, Knapp, Higgins and Green26;27). However, it contains a relatively high number of items (n = 61) and its full application would be cumbersome in routine practice, given the large number of HEEs and the time constraints of the P&R procedures (Reference Wijnen, Van Mastrigt, Redekop, Majoie, De Kinderen and Evers28). Thus, a shorter version was created with the aim of making the assessment process more efficient, that is, balancing timeliness and comprehensiveness. Studies not adopting a model approach were excluded because a different checklist should be considered in these cases and results would not be comparable.

The customized checklist is composed of three dimensions, eighteen topics, and thirty-one items. For each item, four mutually exclusive responses were allowed: “yes” if the study complied with the criterion; “no” if the study substantially diverged from the criterion; “unclear” if the dossier provided insufficient information; “NA (not applicable)” if the criterion was not relevant in a particular instance. Because the application of this checklist may imply value judgments of the reviewer, each item was appraised by two independent reviewers (AC and MZ) and disagreements were resolved by consensus or through a third reviewer (AS or PR), where necessary. We calculated the overall compliance rate of each study by dividing the number of “yes” responses by the total number of items on our checklist. Moreover, the compliance rate of the individual items across studies was calculated by dividing the number of studies with “yes” responses by the total number of studies. In this study, we did not mention medicine names and other details that might reveal a specific product and only aggregated results were showed.

Results

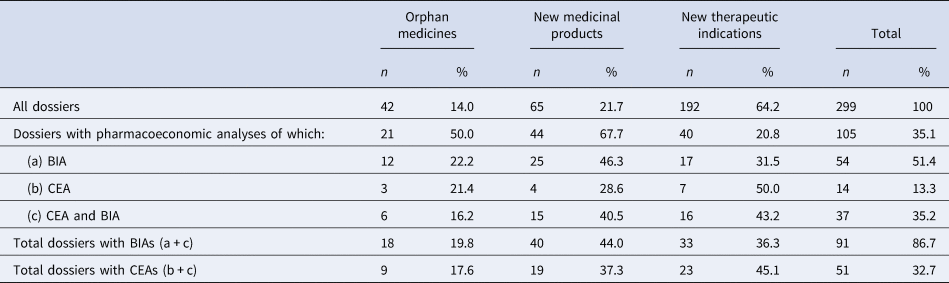

Overall, 299 P&R dossiers were submitted to AIFA for coverage and pricing decisions from October 2016 to December 2018. Among them, only 105 (35.1 percent) included one or more pharmacoeconomic studies, referring to 21 orphan medicines, 44 new medicinal products, and 40 new therapeutic indications. A higher frequency of pharmacoeconomic analyses was observed in P&R dossiers related to new medicinal products (67.7 percent) and orphan medicines (50.0 percent), whereas only a few dossiers included a pharmacoeconomic analysis for new therapeutic indications (20.8 percent). Table 1 shows that dossiers with CEAs, including cost-utility analyses, were less frequently submitted than those with BIAs (32.7 percent, n = 51/105 and 86.7 percent, n = 91/105, respectively). Moreover, when CEAs were conducted, in the majority of cases, they were accompanied by a BIA (72.5 percent, n = 37/51) for all types of P&R applications.

Table 1. Number and type of pharmacoeconomic analyses in the P&R dossiers submitted by pharmaceutical companies to AIFA

General Description and Quality Assessment of HEEs Submitted to AIFA

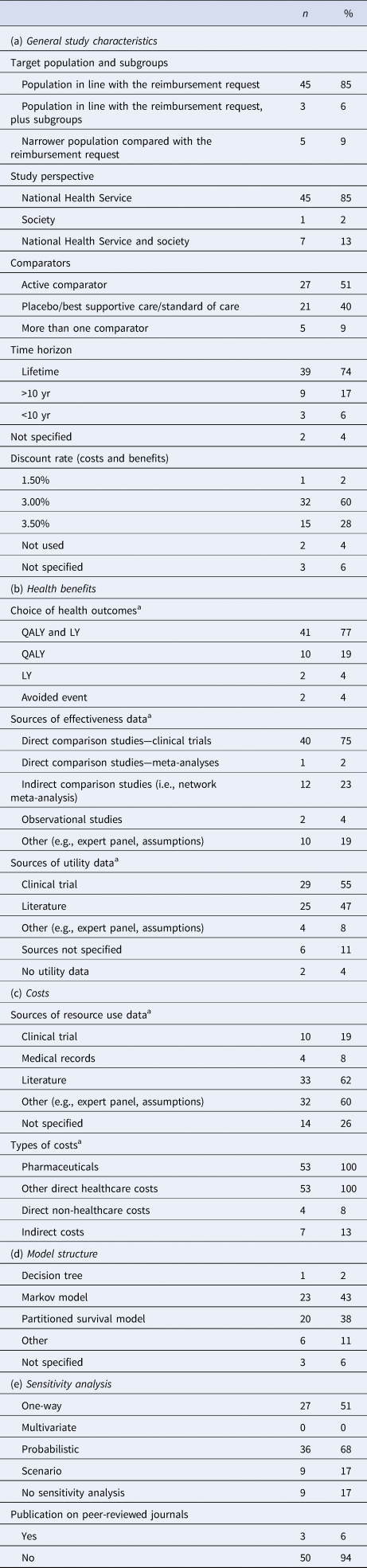

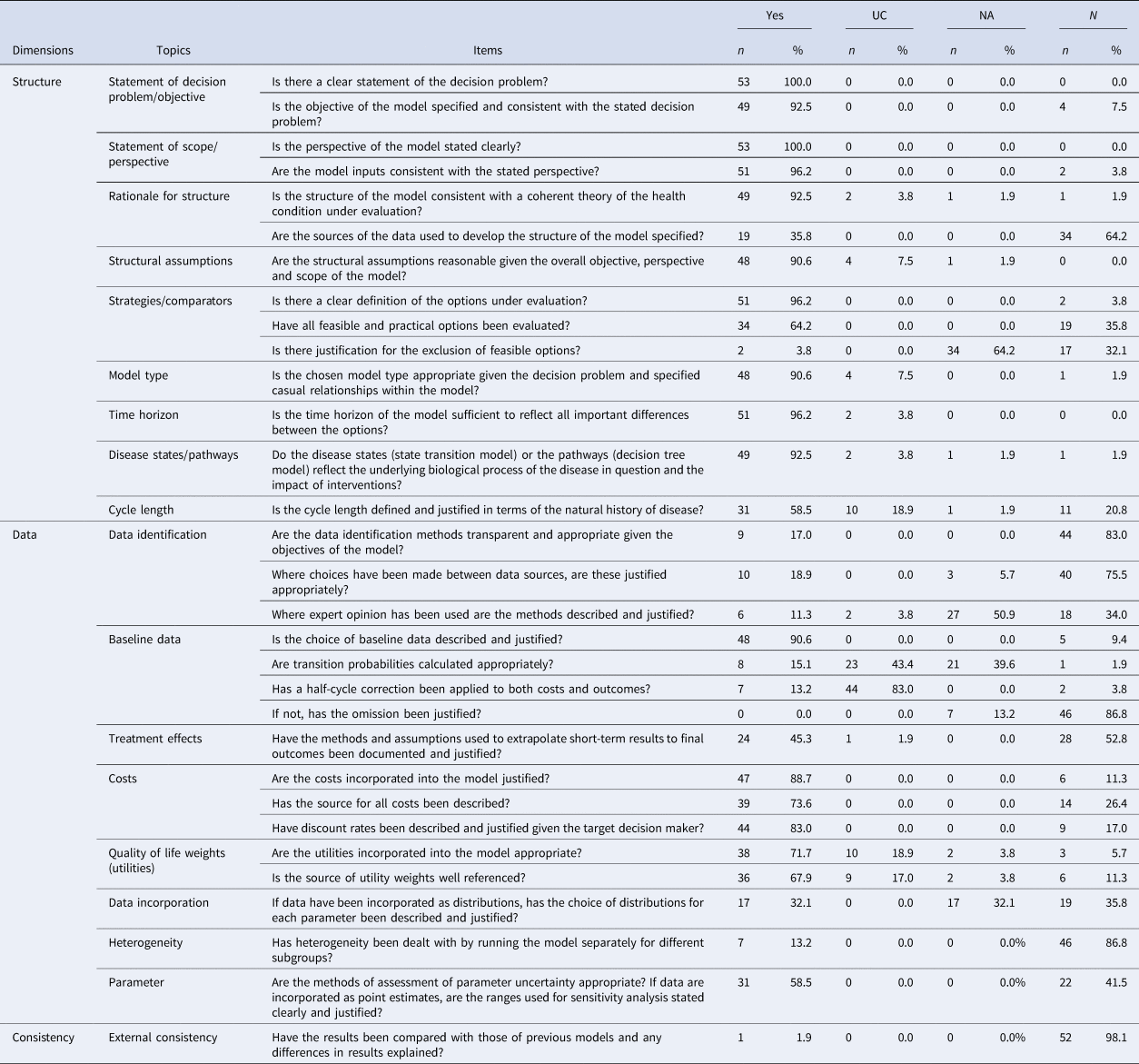

Overall, the P&R dossiers with CEAs (n = 51) included fifty-three model-based HEEs (five non-model-based analyses were excluded from our sample). The general characteristics of HEEs are listed in Table 2 and compliance with quality items is summarized in Table 3.

Table 2. General description of model-based HEEs submitted to AIFA (n = 53)

a More than one option could be selected for each study.

% = Proportions were calculated by dividing the number of relevant submissions on the individual items by the total number of submissions.

Table 3. Evaluation of the HEEs submitted to the AIFA based on a checklist adapted from Philips et al. (Reference Philips, Ginnelly, Sculpher, Claxton, Golder and Riemsma18)

A summary description of all reviewed studies (n = 53) is provided below, based on the five categories mentioned in the “Methods” section. Moreover, the main methodological issues emerged from the application of the quality checklist were further discussed.

General Study Characteristics

Target population and subgroups. Overall, the target population was generally well described and in line with the authorized indication requested for reimbursement (n = 48/53, 90.6 percent). Among these, three studies explored specific subgroups in addition. A narrower population compared to the reimbursement request was rarely used, often without a clear justification.

Perspective. All but one of the fifty-three reviewed studies was conducted from the perspective of the Italian NHS. In few cases the societal perspective was presented in addition, whereas the regional perspectives were never explored. The perspective was always clearly stated. However, in two studies it was found that the model inputs were inconsistent with the declared perspective (i.e., indirect costs and NHS perspective).

Comparators. The alternative options under evaluation were usually well defined. Studies against active comparators were observed in twenty-seven studies and more than one comparator was included in five studies. In the remaining cases (all but one with before-after design) the medicinal product was compared to placebo, standard of care, or best supportive care. The quality checklist highlighted that nearly 36 percent of studies did not include all the most relevant comparators used in clinical practice and very few of them provided justifications for their exclusion.

Time horizon. A long-term time horizon was generally adopted in accordance with international methodological guidelines (thirty-nine lifetime horizon, nine greater than 10 yr), with a minority of studies presenting results over a period of less than 10 years (n = 3) and two studies with an unknown time horizon.

Discount rate. The same discount rate was always used for both future costs and health outcomes (n = 48), ranging from 1.5 to 3.5 percent; in the remaining five studies it was not applied or not reported, despite each study having a time horizon of more than 1 year.

Health Benefits

Choice of health outcomes. All studies expressed the effect measure as QALYs gained or life-years (LYs) gained and forty-one of them reported both measures. The number of avoided events was used in two cases as a further measure of effectiveness in the models.

Source of efficacy and utility data. The prevalent source of efficacy data was the main pivotal trial (n = 40); in twelve cases, indirect comparison studies (i.e., network meta-analysis) were also carried out to populate the model, especially in the absence of head-to-head clinical trial evidence. Description of methods and limitations of indirect comparisons were often poorly reported. Methods and assumptions used to extrapolate short-term results to final outcomes were well documented and justified in only 45.3 percent of the studies. The transition probabilities across health states were often missing or not clearly described in the dossiers, and only for eight studies they were judged appropriately by the assessors. Health-related quality of life data were generally retrieved from the pivotal trial or from a literature review, whereas observational studies, expert opinion, or assumptions were rarely used. The sources of utility weights were judged to be well referenced in over two third of the studies (67.9 percent). However, no studies in our sample made explicit use of Italian-specific preference weights, such as the published Italian value set of the EQ-5D health states questionnaire (Reference Scalone, Cortesi, Ciampichini, Belisari, D'Angiolella and Cesana29;Reference Scalone, Cortesi, Ciampichini, Cesana and Mantovani30).

Costs

Sources of resource use and cost data. The typical approach to costing was to retrieve resource use data from multiple sources in the literature and then assign national tariffs to each item. Generally, disease-specific costs were attached to model health states, regardless of the type of intervention, whereas therapy-specific costs (acquisition and administration costs) were differently assigned to each model arm. No trial-based economic evaluations were found in our sample. Expert panels or assumptions made by the authors were commonly adopted to generate resource use data. On the contrary, data from clinical trials had a limited use in our sample and were generally confined to the calculation of costs of treatment, adverse events, and hospitalizations. In fourteen out of fifty-three studies the source of resource use data was missing for all or for certain items.

Types of costs. All studies included medicine acquisition and other direct healthcare costs, whereas only a few studies considered direct non-healthcare costs (n = 4) and indirect costs (n = 7), either in the base-case analysis or in the sensitivity analysis.

Model Structure

Modeling approaches consisted of Markov models (n = 23), partition survival models (n = 20), decision trees (n = 1), and other decision models (i.e., hybrid models; n = 6); in three cases the type of model was not specified. Even though most studies thoroughly reported on the type of model and description of health states, only a small number gave reasons for the choice of the model structure and data used to develop it (n = 19). Information on the cycle length of health-state transition models was missing or unjustified in over half of the studies (58.5 percent). Half-cycle corrections were explicitly applied only in seven studies.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses were performed for forty-four of the fifty-three reviewed studies. Most were conducted in a probabilistic way (n = 36) and results presented using scatter plots on the cost-effectiveness plane or a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve. A one-way sensitivity analysis was performed in twenty-seven studies, either as a unique analysis or in addition to a probabilistic sensitivity analysis. However, ranges of point estimates and distributions assigned to each parameter in the model were frequently not reported or not justified. The exploration of heterogeneity in sensitivity analyses was properly performed in seven studies.

Publication on peer-reviewed journals. Ninety-four percent of submitted studies was not published at the time of evaluation and decision making, hence these studies were not subjected to the scrutiny of peer-reviewers.

Overall, the quality of reviewed studies was highly variable, with a compliance rate ranging between 19.35 and 90.32 percent (mean 59.22 percent). Similarly, the mean compliance rate of each item was on average 58.43 percent (range 0–100 percent). Out of the thirty-one items on our checklist, sixteen showed compliance rates above 67 percent, five had a compliance rate >33 and <67 percent, and the remaining ten items revealed critical flaws with a compliance rate of less than 33 percent. The main weaknesses emerged from the quality assessment were the following: (i) unjustified exclusion of some relevant alternatives; (ii) lack of transparency or justification of data sources and assumptions; (iii) poor reporting of transition probabilities; (iv) half-cycle correction not used or not reported; (v) distribution of parameters often omitted or not justified; (vi) heterogeneity issues not adequately addressed; and (vii) study validity not checked or not reported.

Discussion and Conclusions

In the current status, where the submission of HEEs within medicines P&R applications is voluntary and no methodological standards have been established by AIFA, the availability of health economics evidence for informing price negotiations in Italy is fairly limited. As a general observation, the number of P&R dossiers with CEAs has not increased over time compared with the frequency reported by Russo (Reference Russo17) (about 35 percent in both studies). Moreover, full economic evaluations were less used by pharmaceutical companies to support their applications compared to BIAs. These elements suggest a low level of acceptance and use of HEEs by both private and public parties involved in the price negotiation process in Italy.

The critical assessment of all fifty-three HEEs submitted to AIFA, between October 2016 and December 2018, revealed that the quality level is widely variable. On one hand, numerous HEEs met high methodological standards, both in the rigor of the analysis and the quality of reporting. To a certain extent, this finding corresponds to our expectations, given the great effort dedicated by the international community in establishing good-practice modeling guidelines, as well as the industry's widespread practice of developing very accurate global cost-effectiveness models subsequently adapted to local contexts (Reference Walker, Wilson, Sharma, Bridges, Niessen and Bass23;Reference Caro, Briggs, Siebert and Kuntz31;Reference Mullins, Onwudiwe, de Araújo, Chen, Xuan and Tichopád32). On the other hand, none of the reviewed studies performed impeccably with respect to all checklist items and some critical issues were identified. The most frequent methodological flaws were the unjustified exclusion of relevant alternatives, the insufficient description and justification of model inputs and assumptions, and the poor exploration of uncertainty and study validity. Moreover, non-homogeneity across studies was found in the choice of the study perspectives, discount rates, methods for costing, estimating QALYs, and conducting sensitivity analyses. In many cases, some relevant information was unclear/not available in the reporting of HEEs and this did not allow a proper critical assessment of models throughout the checklist.

The limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the appraisal of quality inevitably involves subjectivity. The use of a checklist was helpful to identify the main critical issues, but it consisted of general questions whose interpretation often relied on a value judgment by the reviewer (e.g., when methods could be considered “justified”). Another limitation is that the models were assessed against a customized checklist consisting of thirty-one selected items from the Philips's checklist. The methodological approach adopted reflects the concern of maintaining a trade-off between scientific and operational needs in routine practice at AIFA. In addition, the calculation of the compliance rates of each study against the checklist items implicitly involved that each item weighted equally, even though flaws observed in some crucial items might affect the overall quality of a study more than others. For these reasons, the results in terms of compliance rates should be used with caution and always interpreted along with a qualitative descriptive analysis of all criticalities.

Overall, high variability of quality in HEEs submitted for reimbursement decisions was also detected by means of a checklist in other studies (Reference Ramsberg, Odeberg, Engström and Lundin33;Reference Yim, Lim, Oh, Park, Gong and Park34). Unfortunately, a direct comparison with our study was not possible given the methodological differences, mainly in the type of checklist adopted. A limited comparison with the results obtained by Ramsberg et al. (Reference Ramsberg, Odeberg, Engström and Lundin33), regarding the quality of reimbursement submissions in Sweden, showed a similar quality score of approximately 60 percent (range 24–83 percent). Moreover, common shortcomings were related to the choice of the relevant comparators, inconsistencies between types of costs and study perspective, insufficient exploration of uncertainty and study validity. Another study published by Yim et al. (Reference Yim, Lim, Oh, Park, Gong and Park34) about HEEs submitted for reimbursement decisions in South Korea reported a broadly higher quality level to our study, having a compliance rate of 70.9 percent (range 35.0–100 percent) according to their specific checklist, which however does not overlap much with ours.

Despite all the aforementioned limitations, relevant conclusions could be drawn from our study. First, the presence of variation in methodological approaches across studies and poor reporting of relevant information could be overcome by the publication of AIFA guidelines. Second, the checklist allowed the identification of items that should be carefully addressed by future guidelines and better fulfilled by the applicants in order to increase the quality of HEEs. In general, the majority of reimbursement authorities and HTA agencies have produced HEE guidelines to clarify their own position with regard to aspects of methodology (e.g., preferred perspective, discount rate, methods for valuing health outcomes, etc.), which often differ from each other due to different national contexts and cultural values (35–Reference Mauskopf, Walter, Birt, Bowman, Copley-Merriman and Drummond37). However, it is worth noting that the experiences gained from other countries revealed that having such guidelines, although it was helpful in setting a minimum of standards, may not be sufficient to guarantee higher-quality evidence. Wherever they were delivered, a variety of quality issues and weak compliance with the established requirements was found in the HEEs submitted to several reimbursement or HTA bodies in Canada (British Columbia), Australia, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France (Reference Anis and Gagnon38–Reference Toumi, Motrunich, Millier, Rémuzat, Chouaid and Falissard42). For these reasons, the critical assessment of HEEs by internal reviewers, which goes beyond the simple application of a checklist, remains a crucial step in many countries (e.g., Australia and England) (Reference Hill, Mitchell and Henry39;Reference Barbieri, Hawkins and Sculpher43), with different levels of accuracy based on a context-specific trade-off between scientific rigor and available resources (Reference Johannesen, Claxton, Sculpher and Wailoo44). Whenever possible, companies' models should be requested and analyzed using different assumptions or inputs, because industry-sponsored studies are likely to overestimate cost-effectiveness (Reference Johannesen, Claxton, Sculpher and Wailoo44;Reference Eddy, Hollingworth, Caro, Tsevat, McDonald and Wong45).

In conclusion, our study underscored that the quality of pharmacoeconomic studies submitted to AIFA within the reimbursement dossiers has still room for improvement. A much greater effort would be needed by both parties involved in the P&R process in Italy: AIFA should clarify its position with regard to the economic evidence required for decision making, whereas industry should strive to provide more accurate analyses and increase the transparency of their models. Considering the results of this study and the knowledge learned from other contexts abroad, we believe that the issue of AIFA guidelines for reimbursement submissions, together with the strengthening of the internal assessment process, could contribute to enhance the quality of manufacturers' HEEs, as well as the reliability of their results. Overall, both actions will hopefully represent a significant step toward a greater use of HEEs for evidence-based decision making on reimbursement and prices of medicines in Italy.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this work are personal and should not be understood or quoted as being made on behalf of or reflecting the position of the Italian Medicines Agency or of one of their committees or working parties. All authors are employed by the Italian Medicines Agency (Health Economic Evaluation Office) and bound by the obligation of professional secrecy according to the AIFA's Code of Conduct. All content of P&R dossiers submitted to AIFA by pharmaceutical companies is regarded as confidential information. Therefore, medicine names and other details that might reveal a specific product were not mentioned in the article and only aggregated results were showed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marta Toma for providing language editing and proofreading.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have nothing to disclose.