One of the responsibilities of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) is granting of marketing authorization to novel therapeutic agents in the European Union (EU). Once approved under the centralized authorization procedure, new medicines can be marketed throughout the EU. However, in many European countries, patient access to novel therapeutic agents is conditional on reimbursement by payers.

Health technology assessment (HTA)—a multidisciplinary process that systematically considers the clinical, social, economic, and ethical issues related to the use of a health technology—informs payer reimbursement decisions in an increasing number of European jurisdictions (1). Unlike EMA, which primarily focuses its assessment on the benefit-risk profile of new drugs, HTA bodies undertake an assessment of clinical effectiveness, such as added therapeutic benefit and real-world relative effectiveness (Reference Chalkidou, Tunis, Lopert, Rochaix, Sawicki and Nasser2), as well as value for money offered by the new technology.

In England, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is an organization which, as one of its responsibilities, makes recommendations for the payers in the National Health Service (NHS) on whether new technologies should be reimbursed at the national level. NICE Technology Appraisals and Highly Specialized Technologies (for very rare conditions) are the programs focusing on such evaluations (3).

EMA's evidence requirements for marketing authorization have implications for national- and regional-level HTA in Europe. Benefit-risk assessments conducted by the EMA's Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use require trials exploring the efficacy and safety of an investigational agent. Frequently, these trials are short, based on surrogate end points, and may have a placebo as a comparator or no comparator at all. Such evidence may not be sufficient for an assessment of relative clinical effectiveness. HTA bodies often require additional data for reimbursement decision making (Reference Clement, Harris, Li, Yong, Lee and Manns4). The absence of longer-term comparative data results in significant uncertainty, which can be defined as the lack of conclusive evidence to substantiate the value claims of a product (e.g. due to single-arm trials or immature data) and thus, its clinical and cost-effectiveness.

Currently, EMA has two special approval pathways to facilitate earlier market access to certain products: conditional marketing authorization (CMA) and approval under exceptional circumstances (AEC). EMA grants a CMA when the approval is based on data which, while not yet mature or comprehensive, indicate that the medicine's benefits outweigh its risks. The CMA can only be granted for medicines that satisfy an “unmet medical need” (5). While the CMA decision is based on limited clinical data, successful generation of comprehensive data is statutorily required prior to granting full marketing authorization via postauthorization efficacy studies (6). Medicines aimed at treating rare conditions may also gain an AEC if the sponsor can show that it is unable to provide comprehensive data on the efficacy and safety of the medicine for which authorization is being sought, for example, because of potential ethical issues or limited scientific knowledge in the area. Unlike the CMA, an AEC is not aimed to be converted to full authorization (5).

The lack of robust clinical data at the time of CMA/AEC decisions poses significant risks for patients and the healthcare system and directly impacts HTA decision making. Patients may get access to treatments with unproven benefits and uncertain safety profile. These risks could be addressed through additional data collection once the product is in use in clinical practice. The risk to patients associated with these products can be partially mitigated through restricted and closely monitored use and the risk to the healthcare system can be mitigated through commercial negotiations on the price of the drug. These strategies can be implemented, for example, through various types of managed access agreements (MAA). Companies developing drugs or treatments that are expensive and unlikely to be recommended by NICE for use in the NHS can offer NHS England a patient access scheme (PAS), which commonly consist of confidential discounts (7). The new Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) offers the opportunity to generate evidence on the effectiveness of new cancer drugs associated with clinical uncertainty while these are being used in the NHS. When a treatment is recommended for use within the CDF, a formal data collection arrangement is drawn up as part of an MAA, outlining the key areas of uncertainty and explaining how these will be addressed through data collection. The other component of the MAA is a commercial access agreement, which determines the level of reimbursement during the data collection period (8). This route is particularly relevant to some cancer medicines which obtain a CMA and are presented for a NICE evaluation with a limited evidence base.

In this paper, we investigate the impact of the uncertainty stemming from less comprehensive data associated with products approved by the EMA under CMA or AEC on NICE's recommendations. Our objective is to explore how NICE advisory committees respond to such uncertainty. Specifically, we investigate if the uncertainty associated with these products leads to negative recommendations and, if not, whether the positive recommendations are subject to further data collection or commercial arrangements. We also analyze if commercial arrangements are more common for products with CMA/AEC than for products with full authorization comparing the odds of implementing commercial arrangements for products with and without CMA/AEC; and whether the conversion to full marketing authorization leads to changes in the NICE recommendations over time. Finally, we draw lessons for the future, as the EMA plans to implement new models aimed at expediting drug development and approval (9). A full list of acronyms used in this manuscript can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. List of Abbreviations

Methods

Sample Identification: Cohort of Drugs with European CMA and AEC

The EMA database of European Public Assessment Reports was searched to identify all pharmaceutical and biologic agents that had received CMA/AEC between 2002 and 1 December 2016. Information was extracted about the marketing authorization and whether it had been converted from conditional to full authorization by the end of data extraction. The status of this marketing authorizations was further traced up to August 2019.

Identification of Drugs with CMA/AEC Evaluated by NICE

The NICE Web site was searched to match products with European CMA/AEC with NICE evaluations at the indication level. Only products referred for evaluation from the Department of Health and Social Care are evaluated by NICE (10). Some products were outside of NICE's remit (such as HIV treatments). Furthermore, in order for NICE to conduct an evaluation, this has to be deemed to add value to the NHS (e.g. if without a NICE guidance, there is likely to be significant controversy over the interpretation of the available evidence on clinical and cost-effectiveness).

NICE Recommendations

The NICE Web site was reviewed to collect information on the final recommendations by NICE. These were categorized as recommended, recommended with a commercial arrangement (PAS, MAA, and MAA specifically as part of the CDF) or not recommended. Information on data requirements associated with those commercial arrangements was extracted, where relevant. Negative recommendations were analyzed to identify whether these were impacted by the uncertainty associated with products with CMA/AEC such as the lack of robust clinical data.

The evolution of the NICE recommendations was traced over time in order to identify if changes in the products' marketing authorizations had an impact on the original recommendations. These were first checked in August 2017 and subsequently in August 2019.

Analysis

Suspended and terminated NICE appraisals were excluded from the analysis since these do not include any recommendations. Withdrawn recommendations were also excluded since they did not carry any recommendations at the time of analysis. Multiple technology appraisals have been counted as different appraisals for each individual product evaluated within it. However, multiple recommendations within a single technology appraisal for the same product have been counted as one, classifying the product as recommended if any of the recommendations were positive. A commercial arrangement was only counted in the analysis if it specifically referred to the product with CMA/AEC. Furthermore, commercial negotiations other than those where NICE have had input (e.g. agreements through the commercial medicines unit) have been excluded.

The odds of NICE's recommendations carrying a commercial arrangement for products with and without CMA/AEC were calculated: an odds ratio (OR) and its 95 percent confidence interval. The regulatory status (CMA/AEC vs. full authorization) and the inclusion of a commercial negotiation in the NICE recommendation (presence of a commercial arrangement vs. no commercial arrangement) were used as binary variables to build the 2 × 2 contingency table. STATA 15 software was used for the computation of the OR (11).

Two investigators independently matched the CMA/AEC products with corresponding evaluations conducted by NICE. This was reviewed by a third investigator. One investigator derived the NICE recommendations and conducted the analysis. Another investigator independently reviewed the data extraction and analysis. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. The data set is included in Supplementary Table 1.

Results

Between 2002 and 1 December 2016, EMA had granted CMA (n = 28) or AEC (n = 26) to fifty-four products. As of August 2017, three products had their marketing authorizations withdrawn due to (a) lack of efficacy (drotrecogin alfa) (12), (b) inability of the sponsor company to provide the additional data required to fulfil its specific obligations (celecoxib) (13), and (c) commercial reasons (rilonacept) (14). During this period, fourteen CMAs were converted into full authorizations (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Evolution (2017–2019) of products granted conditional marketing authorization or authorization under exceptional circumstances by the European Medicines Agency up to 1 December 2016 (n = 54).

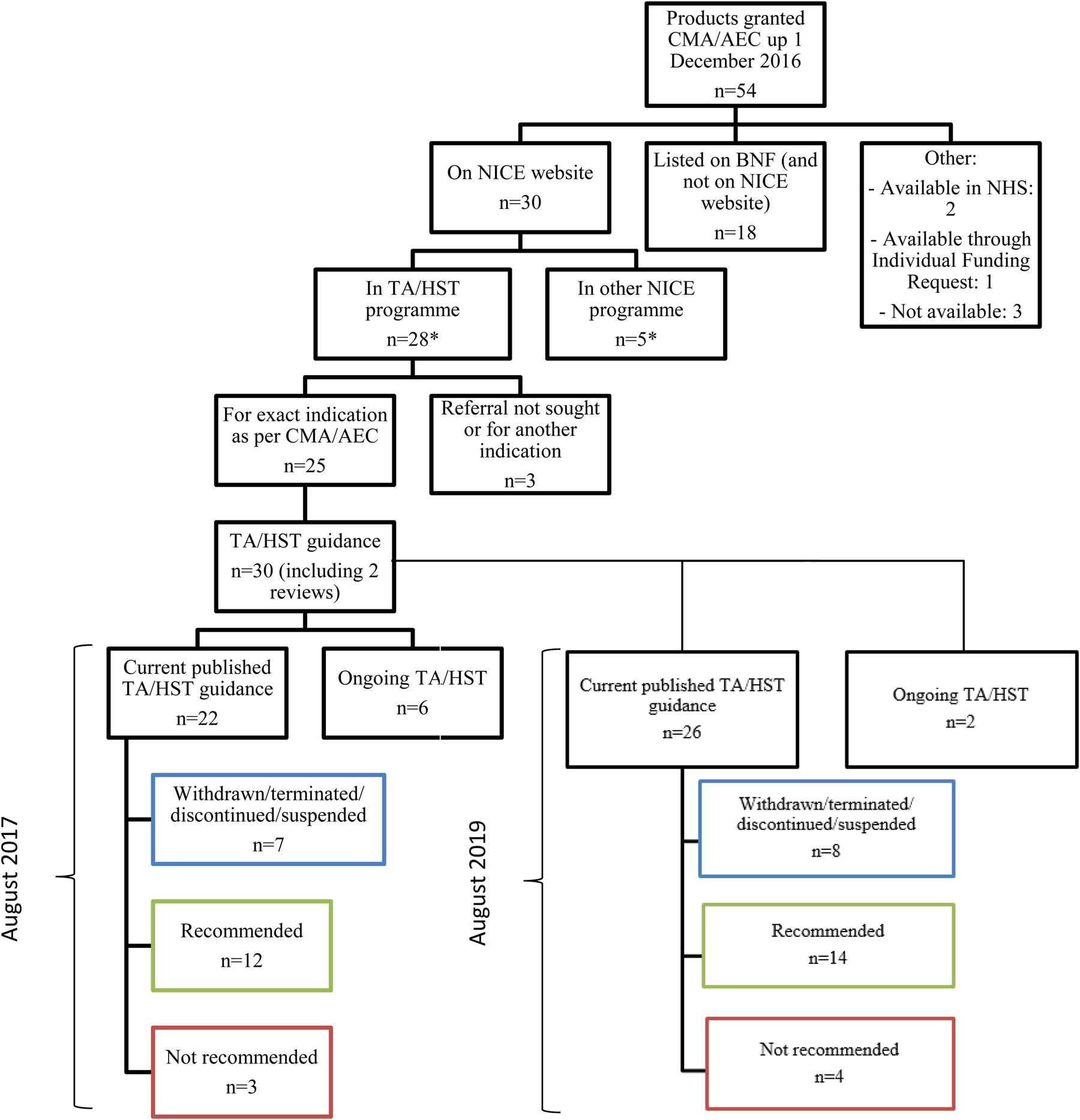

Out of the fifty-four products that originally had CMA/AEC, thirty were listed on the NICE Web site by August 2017 (Figure 2). Twenty-eight out of the thirty were listed as a NICE evaluation and five products were considered by NICE in clinical guidelines and/or evidence summaries. Three products out of the twenty-eight were evaluated in an indication that differed from the one for which the product received CMA/AEC, or their appraisals were not sought for referral (15;16).

Figure 2. Data flow of products granted conditional marketing authorization or authorization under exceptional circumstances by the EMA up to 1 December 2016 and availability in the NHS. CMA, conditional marketing authorization; AEC, approval under exceptional circumstances; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; BNF, British National formulary; NHS, National Health Service; TA, technology appraisal; HST, highly specialized technologies.

The remaining twenty-five products with CMA/AEC triggered thirty evaluations. Out of these thirty evaluations, six were still ongoing, two were reviews of previous recommendations, seven had been withdrawn (n = 1), terminated (n = 2), discontinued (n = 3), or suspended (n = 1) and therefore did not carry any recommendations, three were not recommended and twelve were recommended (Figure 2). All these twelve products were recommended alongside a commercial arrangement (PAS [n = 8], CDF/MAA [n = 4]).

Two of the twelve recommended appraisals originally received negative recommendations by NICE for the same product and indication: crizotinib and bosutinib. Both products originally received negative recommendations because of high incremental cost-effectiveness ratios and a lack of robust clinical data. The reviews were triggered by the transition from the old CDF, in which cancer products which were not recommended by NICE could be reimbursed by the NHS through this fund (17). NICE recommended crizotinib and bosutinib in their respective reviews following new commercial arrangements (18;19). In the case of crizotinib, the committee concluded that the size of the overall survival estimate with crizotinib was still uncertain.

Although only three products were not recommended (sunitinib, panitumumab, and ofatumumab (20–22), their clinical uncertainty featured amongst the reasons for these negative recommendations. Table 2 contains further details. The conversion to full authorization did not lead to changes in NICE recommendations. The marketing authorizations of sunitinib, panitumumab, and ofatumumab have been converted into full by the EMA but did not trigger a review at NICE. In the case of sunitinib, the conversion from conditional to full authorization was based on an application from the company to extend the indication from the second to the first-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma based on data available on the first line (23). This triggered a new evaluation at NICE for the same product in the first-line treatment.

Table 2. Rationale of Negative Recommendations by NICE on Products Granted Conditional Marketing Authorization or Authorization in Exceptional Circumstances

TA, technology appraisals; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

In the case of panitumumab, when its CMA was converted into full authorization, NICE initiated a review proposal but did not go ahead with the review, as the new data were unlikely to have an impact on the recommendations. The company that holds the marketing authorization for panitumumab supported NICE's opinion during consultation (24).

Obligations that the marketing authorization holder for ofatumumab had to fulfil as part of the CMA included conducting a controlled study—ofatumumab versus physician choice in patients with bulky fludarabine refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (OMB114242), in addition to the provision of the results from ongoing studies in earlier lines of therapy. The results presented from the study OMB114242 showed that there was no statistically significant difference in progression-free survival, the primary end point (25). As of August 2017, NICE had not carried out a review proposal of ofatumumab's appraisal as it was awaiting trials completion and publication of the final results.

Excluding evaluations which have been withdrawn, terminated, discontinued, or suspended, and thus, analyzing those appraisals for which NICE had issued recommendations, by August 2017, NICE recommended 80 percent (12/15) of the products that were evaluated having received EMA's CMA or AEC up to 1 December 2016 (see Figure 2). All products with CMA/AEC that were recommended by NICE were subject to a commercial arrangement, five of which included data collection requirements. Data requirements outlined as part of the commercial arrangement for products with CMA/AEC are included in Supplementary Table 2. The rest of commercial arrangements were based on PAS and did not require data collection. The odds of carrying a commercial arrangement were significantly higher for products with CMA/AEC than for those with full authorization (OR 9.50; 95 percent CI 2.49–53.12). We conducted a sensitivity analysis restricting the time frame for the analysis from October 2007 onwards, when the first commercial arrangement was granted. We obtained similar results (OR 8.51; 95 percent CI 2.23–47.61). During this period, 70 percent of products with full marketing authorization had a commercial arrangement at the recommendation stage.

Changes up to 2019

As of August 2019, three additional products had their marketing authorizations withdrawn: two due to commercial reasons (antithrombin alfa and ofatumumab) (26;27) and one due to lack of demand for the drug (alipogene tiparvovec) (28). Seven additional products that had CMA or AEC have had their authorization converted into full (Figure 1).

Two of the three products that were not recommended in 2017 remained not recommended (sunitinib and panitumumab) and one (ofatumumab) has had its license and evaluation withdrawn. Out of the six products that had their evaluation ongoing in August 2017, one was still ongoing, two have not been recommended, and three have been recommended with a commercial arrangement (Figure 2).

For example, daratumumab, whose evaluation was ongoing in August 2017, was subsequently recommended for use within the CDF. These recommendations were published before its marketing authorization was converted to full. One of the products that was recommended within the CDF in August 2017 (brentuximab vedotin for CD30-positive Hodgkin lymphoma) exited the CDF and was later recommended for routine commissioning with a commercial arrangement. Its marketing authorization remained conditional. Osimertinib, whose license was converted into full and which was recommended by NICE within the CDF, had its evaluation under review at the end of the data check.

By August 2019, NICE had recommended 78 percent (14/18) of the products that were evaluated having received EMA's CMA/AEC up to 1 December 2016. All products with CMA/AEC that were recommended by NICE were subject to a commercial arrangement.

Discussion

In January 2017, the EMA published a 10-year report on its experience with CMA (29), which showed that, in order to speed up market access for specific products (usually those addressing high unmet medical need), the EMA has increasingly granted CMAs. Products which receive this type of authorizations carry inherent uncertainties, such as lack of robust clinical data, to demonstrate their clinical and cost-effectiveness, and thus, have a substantial impact on HTA assessments as seen in this study. Despite the fact that most of the products with CMA/AEC evaluated by NICE have received positive recommendations (by August 2019, 78 percent [14/18]), all of them had an associated commercial arrangement. A PAS was the only commercial mechanism available until 2016, but since then, products with CMA/AEC have also entered clinical practice via the CDF or have been recommended within an MAA. The latter mechanisms not only address the financial risk for the healthcare system of incorporating and paying for products which are potentially not cost-effective, but also provide the opportunity for collecting further data to mitigate some clinical uncertainties.

Previous studies have noted that in Europe, conditional pathways have been referred to as “rescue options” for products that are deemed unlikely to receive regular approvals due to their limited evidence base (30;31). Further evidence generation may sometimes be hampered once these products are on the market, and research efforts may not adequately address the uncertainty associated with their benefits and harms. This poses significant risks to patients and the healthcare system. Recent empirical evaluations documenting the dynamics of postmarketing evidence generation show that there are frequent delays and discrepancies in the completion of the required studies (32;33). In the US, only half of the products granted accelerated approvals by the US Food and Drug Administration had their required postmarketing studies completed after at least 3 years on the market (Reference Naci, Smalley and Kesselheim34).

European payers have recently voiced their criticism and skepticism about expedited approval mechanisms (Reference Ermisch, Bucsics, Vella, Arickx, Bybau and Bochenek35). In the case of new cancer treatments, some studies have shown that there is no evidence that conditional approval led to differences in HTA decisions neither that the presence of controlled data had a decisive impact on HTA decisions (36;37). However, there is yet little experience on the evaluation of these products and the sample size is small so findings should be interpreted with caution. The proportion of positive recommendations in products with CMA/AEC is similar to NICE's overall recommendations in the technology appraisals program (38). However, the odds of commercial arrangements were almost tenfold higher for products with CMA/AEC compared to those with the full EMA approval as of August 2017. This shows that additional mitigation mechanisms are required to deal with the uncertainty associated with these products. The conversion of the marketing authorizations from conditional to full does not seem to have had an impact on NICE's recommendations, which may mean that data required for regulatory purposes do not necessarily meet HTA's requirements to warrant a change in the recommendations. However, it may be expected that mechanisms such as the CDF, which contain data collection arrangements, may overcome this limitation, and indeed become a tool frequently used for products with CMA/AEC in order to allow early patient access to promising, yet clinically uncertain, products. Caution should be taken so these mechanisms are only reserved for those products that show promising results since according to the literature, these agreements are difficult to implement, enforce, and monitor (Reference Ferrario and Kanavos39).

Limitations and Strengths

This study has limitations. First, the sample size of the analysis is relatively small given the number of products with CMA or AEC that have undergone a NICE evaluation for the exact indication for which the license was granted. The current number of NICE evaluation reviews, after conversion from conditional to full authorization, is even smaller and due to data sparseness, we have been unable to perform any multivariable analyses. On some occasions, the evidence used by the regulators to grant the conversion to a full MA referred to the same product's indication but in another line of therapy. This was the case with sunitinib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma, which triggered a new appraisal at NICE for another line of treatment. Second, not all products that received CMA/AEC were evaluated by NICE. However, we investigated whether the twenty-four products not listed on the NICE Web site were listed in the British National Formulary (40), available in the NHS through a national commissioning policy or by individual funding requests (41). We also checked the Monthly Index of Medical Specialities database (42) and the Specialist Pharmacy Service database (43). Eighteen products were listed in the BNF, two products were available in the NHS through a commissioning policy and one was available via individual funding request. Through an individual funding request, a treatment that is not routinely offered by the NHS can be made available to an individual patient when a clinician believes that the patient's clinical circumstances are clearly different to other patients with the same condition, and when there is a reason why the individual patient would respond differently than other patients—and therefore gain more clinical benefit from the treatment.

Third, the nature of most commercial arrangements is confidential, so we could not assess whether the level of the discount offered by the company differed between products with CMA/AEC and full authorization.

Despite these limitations, this analysis provides the first in-depth evaluation of the NICE's experience with products granted CMA and AEC by EMA. Furthermore, through a two-step process, it has been possible to show how NICE's recommendations for these products have evolved over time. To the best of our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive assessment of products with CMA and AEC and subsequent HTA recommendations.

Policy Implications

Efforts should be made to conduct high-quality postmarketing studies to minimize risks to patients who are receiving products with CMA/AEC in clinical practice. Such evidence generation practices can inform HTA evaluations and trigger changes, as necessary. This will also ensure that patients access treatments which are appropriately monitored for the quality of their evidence base. As the regulatory trend for early access continues, companies, regulators, decision makers, payers, and patients should all have vested interests in long-term evidence generation. Recommendations linked to MAA are increasing at NICE. Efforts should be made to ensure that data collected through this mechanism are adequately monitored and relevant to patients and the healthcare system.

Conclusions

Uncertainty stemming from the lack of robust clinical data on products authorized with CMA or AEC has a substantial impact on HTA recommendations, requiring risk mitigation mechanisms such as commercial negotiations and further data collection arrangements. Such mechanisms may not fully address the uncertainties at the time of market entry. Therefore, they should be reserved only for those products that show promising results in terms of clinical outcomes. All stakeholders in the system should work together to ensure that early access pathways are not exploited, and further analyses should be conducted to assess whether the benefits of such early access strategies outweigh the risks for patients and the healthcare system.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462320000355

Financial support

This research received no specific funding from any agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.