A rare disease is a disease which affects a small number of people in a population as compared with other prevalent diseases (Reference Richter, Nestler-Parr and Babela1). In other words, a rare disease is a medical condition which has low prevalence, is life-threatening or chronically debilitating, and has different definitions from one country to another (Reference Pearson, Rothwell, Olaye and Knight2). Examples of rare diseases include genetic diseases, rare cancers, infectious tropical diseases, and degenerative diseases (Reference Gammie, Lu and Babar3;Reference Ollendorf, Chapman and Pearson4). For example, the National Organization for Rare Diseases has defined them as diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 individuals, or approximately sixty per 100,000 population (Reference Ollendorf, Chapman and Pearson4). However, the European Union (EU) has defined the condition as affecting no more than five in 10,000 people. Totally, it is estimated that there are 6,000–8,000 rare diseases in the world affecting approximately 6–8 percent of the world’s population (Reference Richter, Nestler-Parr and Babela1;Reference Gammie, Lu and Babar3).

Today, approvals of orphan drugs such as biopharmaceutical products for patients with serious, disabling, and fatal diseases have provided new chances for the patients (Reference Ollendorf, Chapman and Pearson4). Following these achievements, the market for orphan drugs is expanding. In 2015, worldwide sales of orphan drugs reached USD 100 billion, but the market is expected to amount more than USD 200 billion by 2022. It is estimated that, by 2022, one-fifth of all prescription drug sales will be related to orphan drugs. Furthermore, the average annual cost for orphan drugs is calculated to be five times greater than that for nonorphan medications (USD140,443 vs. USD27,756, respectively) (Reference Ollendorf, Chapman and Pearson4).

There is a lot of debate in different countries over the financial support of orphan drugs. These debates include the allocation of governmental subsidies for orphan drug development such as providing tax incentives and clinical development costs as well as extending patent protections (Reference Ollendorf, Chapman and Pearson4). There is evidence of a societal impulse to prioritize treatment for conditions that are severe or genetic based, and those which affect very young people (Reference Ollendorf, Chapman and Pearson4). On the other hand, health system policy makers in the world must deal with the conflict generated by competing increasing demands and insufficient resources for providing orphan drugs and their financial protection in their own countries. Orphan drugs may be costly to develop, but the target population is very small, and the need to recoup (R&D) “research and development” costs is often reflected in high prices (Reference Lopez-Bastida, Ramos-Goni and Aranda-Reneo5).

Although the availability and affordability of orphan drugs have high priority for policy makers in all countries, such policies are sometimes destined to fail or are limited because of cost-effectiveness (CE). Because of that, prioritization for rare diseases drugs is becoming very important in order to ensure maximum efficacy and effectiveness with limited resources. There is no definite way to prioritize orphan drugs. Different methods are used to do so, including CE analysis and multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA). However, the common characteristics in all these methods (mostly related to MCDA) are their needs for the criteria for prioritization that could lead to maximum efficacy and effectiveness of health interventions (Reference Lasalvia, Prieto-Pinto and Moreno6). Regarding all the aforementioned reasons, this study aimed to identify the methods and criteria for prioritizing rare diseases and orphan drugs. The results of this study can help make evidence-informed policies for rare diseases in many countries in various aspects. These aspects can include prioritizing these diseases for ensuring availability and affordability of their treatment in the form of benefit packages or subsidies, provide scientific accountability evidence for community, plan to manufacture and produce drugs, and finally choose the appropriate solution to supply drugs and treatment for rare disease.

Methods

The scoping review was conducted because we wanted to identify knowledge gaps and scope a body of literature about various methods and criteria for prioritizing orphan drugs and rare diseases. For this purpose, we used the five stages of Arksey and O’Malley’s framework, as described below, for scoping the review (Reference Arksey and O’Malley7):

Identifying the Initial Research Questions

According to the purpose of this study, we put the following items on the agenda:

What are the methods for prioritizing orphan drugs and rare diseases?

Which criteria were selected for prioritizing orphan drugs and rare diseases?

Identifying Relevant Studies

We performed comprehensive literature searching in the major databases, including Scopus, PubMed, Embase, and the websites of health technology assessment (HTA) agencies (like EUnetHTA, CADTH, and NICE) from 1 Jan 2000 to 1 Jan 2021, for English and Persian language articles in all types of research. Aiming to search the abovementioned databases, a search strategy appropriate to each database regarding MeSH guidelines was used with the following keywords: “orphan drugs,” “orphan disease,” “drug costs,” “prioritize,” “budgeting,” “economics,” and “health policy” (Supplementary Table 1). We also searched across the websites of governments and organizations and Google for data in gray literature to obtain possible related evidence.

Study Selection

The conducted searches included only the studies which could provide information about prioritizing orphan drugs or diseases (the papers with type of original or review with explicit method section). The titles and abstracts of the articles which were found were checked out by two researchers in parallel and any disagreements were resolved by mutual consent. The abstracts were reviewed and the studies without an explicit methods section were excluded. Full texts of the remaining articles were reviewed for inclusion. In addition, references in the selected articles were further searched for additional articles.

Data Charting and Collation

In this part, the data were extracted from the articles according to the developed framework based on the questions and the dimensions of the studies and then presented in excel sheets. The framework combined the general specifications of the articles, such as the title, year, authors, country, and method for prioritizing orphan drugs or diseases as well as the criteria for prioritizing.

Summarizing and Reporting Findings

In the final step, to ensure the accuracy of data extraction and literature analysis, we used text search in MAXQDA software (8) to determine categories and subsets for priority setting.

The findings of the selected studies were synthesized using a directed approach of qualitative content analysis known as deductive category formulation (Reference Hsieh and Shannon9). In this study, the researchers were interested in better understanding of the methods and criteria currently used for priority setting of orphan drugs and rare diseases, and research questions were used to find differences and similarities in different studies to formulate categories. Two researchers independently produced the intially identified categories. Then, the researchers shared their drafted analyses and interpretations and had a meeting to discuss the identified categories. We classified all categories into subsets according to the general commonalities among them.

Results

Study Selection

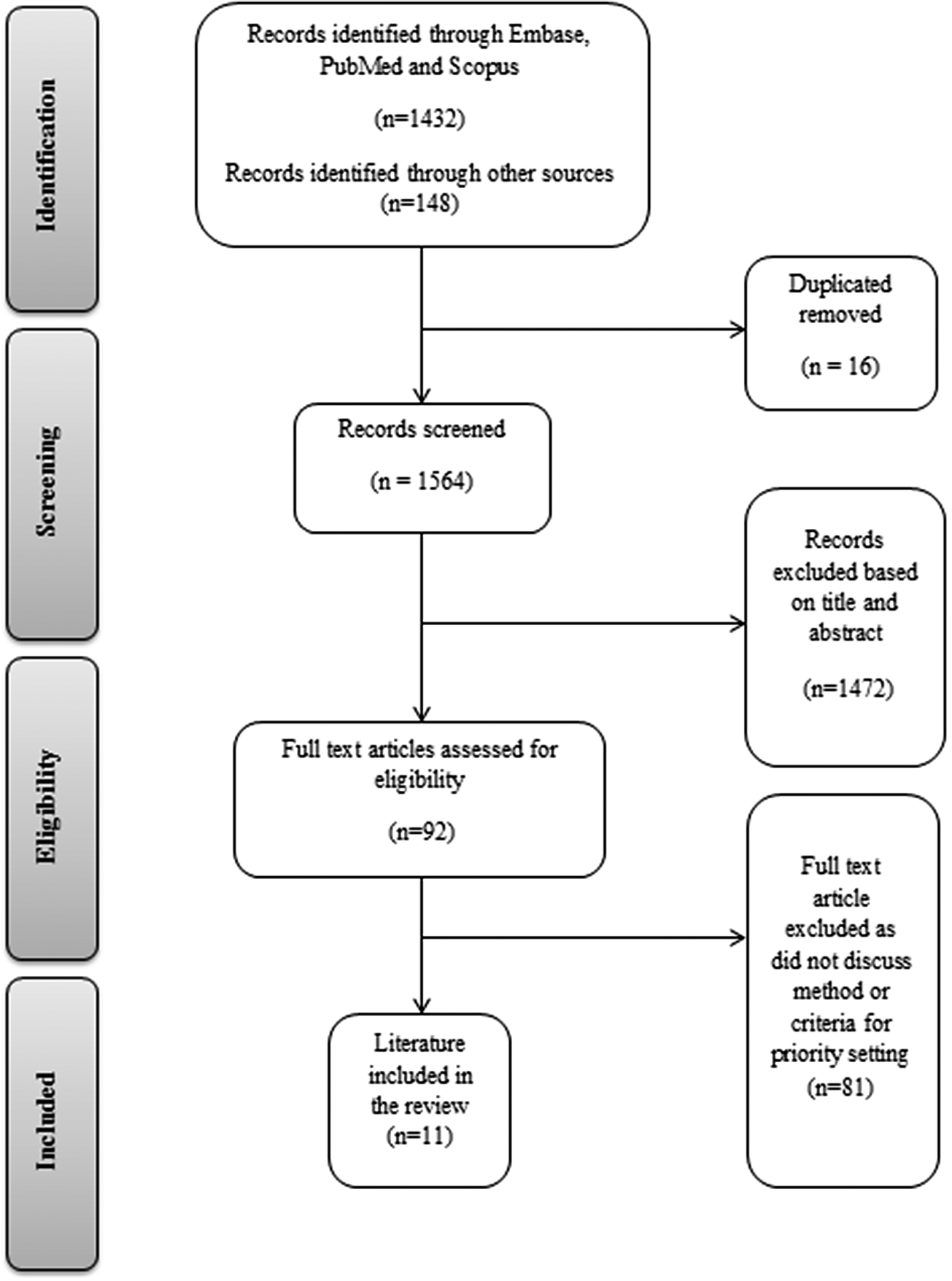

Thousand five hundred and eighty articles were found in the initial search. After reviewing titles and abstracts, we excluded sixteen duplicates and a further 1,472 papers which did not refer to orphan drugs or rare diseases or were otherwise not relevant. We reviewed the full text of the remaining ninety-two papers and found eleven relevant papers to include in our review. This process was carried out in accordance with the PRISMA statement and is summarized in Figure 1 (Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin10).

Figure 1. Article screening process (PRISMA 2018 flow diagram).

Characteristics of Studies

All identified studies were published between 2015 and 2019. Contexts included fourteen different countries (see Table 1), Central and Eastern European countries, and Europe as a whole (Reference Ollendorf, Chapman and Pearson4–Reference Lasalvia, Prieto-Pinto and Moreno6;Reference Nicod11–Reference Guarga, Badia and Obach16).

Table 1. Frequency of Included Papers[CMT5] on the Base of Country

Methods of Assessment

Two main methods for assessment of orphan drugs and rare diseases were identified. This review included three review articles that were assessed for the valuation criteria of orphan medicines in different countries. Six tested the criteria for priority setting of orphan drugs qualitatively. In the qualitative studies, the researchers employed “qualitative MCDA or discrete choice model” to score and rank the criteria (Reference Baltussen, Marsh and Thokala17). Two studies used mixed methods where CE analysis was compared to MCDA (Table 2). As we can see, MCDA was the most frequent method (seven out of eleven studies) for priority setting of orphan drugs and rare disease. In all seven studies, the main criteria were extracted and prioritized according to the MCDA method based on the opinion of experts, and in two of them, scenarios were designed based on the importance of different criteria.

Table 2. Extraction Data from Full Text

Abbreviations: BI, budget impact; DCE, discrete choice experiments; DRD, drugs for rare diseases; MCDA, multicriteria decision analysis; OD, orphan drugs; PRO, patient-reported outcome.

Criteria for Assessment

Criteria for priority setting of orphan drugs and rare diseases were analyzed in six main domains as follows: health outcomes and clinical implications, economic aspects, disease and population characteristics, therapeutic alternatives and uniqueness of orphan technologies, quality and availability of evidence, and other social and organizational criteria. Figure 2 shows the frequency of each criterion in the reviewed literature and as we can see CE, budget impact and disease severity were mentioned most frequently (see Figure 2). In the next part, the subsets of each domain are explained comprehensively.

Figure 2. Frequency of each criterion in the literature.

Health Outcomes and Clinical Implications

Health Benefits

Three studies addressed health benefits of policy making for orphan drugs. “Impact on the patient, job and family,” “health and social effects,” “impact on the provision of care services,” “capacity related to the benefits of treatment,” and “improvement health” were the main proxy attributes which reflected health benefits (Reference Ollendorf, Chapman and Pearson4;Reference Lopez-Bastida, Ramos-Goni and Aranda-Reneo5;Reference Nicod11). The term “improvement health” is related to the patient’s feeling in the treatment process on the EQ-5D scale (Reference Lopez-Bastida, Ramos-Goni and Aranda-Reneo5).

Clinical Benefits

Clinical benefits were determined in orphan drugs policy making as attributes like “clinical uncertainty,” “clinical evidence,” and “clinical effectiveness and efficacy” (8;Reference Friedmann, Levy, Hensel and Hiligsmann13–Reference Kolasa, Zwolinski, Kalo and Hermanowski15). Clinical evidence was defined as the best available scientific information to guide decision making about clinical management (Reference Kolasa, Zwolinski, Zah, Kaló and Lewandowski14).

Efficacy/Effectiveness

“Comparative efficacy” was the most frequent attribute in the included studies for the evaluation of policy making for orphan drugs and three papers mentioned this attribute (Reference Arksey and O’Malley7;Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin10;Reference Nicod11). This attribute was the most quantitative attribute regarding the orphan drugs policy making (Reference Arksey and O’Malley7).

Safety

Safety was one of the important attributes mentioned by six included studies. The main terms which were defined for safety in the included studies were “safety and tolerability,” “drug safety considerations,” “the level of treatment safety,” “safety and side effects,” “level of side effects,” and “drug safety” (Reference Lopez-Bastida, Ramos-Goni and Aranda-Reneo5;Reference Arksey and O’Malley7;8;Reference Nicod11–Reference Friedmann, Levy, Hensel and Hiligsmann13). Given the shortage of data on safety aspects of orphan drugs, discussions between experts will have a great value for determining safety status (Reference Friedmann, Levy, Hensel and Hiligsmann13).

Quality of Life

In Eastern and Central European countries, the “quality of life lost without treatment” was one of the important attributes for policy making of orphan drugs (Reference Nicod11). Priority setting of rare diseases could be performed by QALYs via disease states (Reference Nicod11).

The Level of Uncertainty in Effectiveness

“The degree of uncertainty about the effectiveness of the drug” for orphan drugs policy making was defined via attributes like clinical benefit, study design, comparator, population and generalizability, sample size, and safety (Reference Hsieh and Shannon9). This attribute can be categorized into three levels: “immature but promising data,” “appropriate surrogate endpoints,” and “robust clinical endpoints” (Reference Hsieh and Shannon9).

Economics Aspects

Cost-Effectiveness

The most frequent main attribute mentioned in seven papers was “cost-effectiveness.” Considerations regarding the methods of incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) calculations for adapting the orphan drugs policy making context and determining the accurate threshold for it were the major discussions in the papers (Reference Ollendorf, Chapman and Pearson4;Reference Lopez-Bastida, Ramos-Goni and Aranda-Reneo5;Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin10–Reference Kolasa, Zwolinski, Zah, Kaló and Lewandowski14). According to the Ollendorf et al. (Reference Ollendorf, Chapman and Pearson4) study, for England and Wales, Sweden, and the Netherlands, the CE thresholds were Pound Sterling 100,000, 35,000–100,000, and EURO 80,000 per QALY, respectively. ICER in MCDA context based on the Friedmann et al. (Reference Friedmann, Levy, Hensel and Hiligsmann13) study (as trade-off criteria of decision matrix) was categorized into three groups, ICER below EURO 24,000, ICER in the range between 24,000 and EURO 48,000, and ICER above EURO 48,000.

Costs

Four papers mentioned “cost” via proxy attributes like “cost data,” “treatment costs,” and “costs of drugs for rare patients (non-medical and medical)” (Reference Lopez-Bastida, Ramos-Goni and Aranda-Reneo5;Reference Short, Stafinski and Menon12;Reference Kolasa, Zwolinski, Zah, Kaló and Lewandowski14;Reference Baltussen, Marsh and Thokala17). This term refers to the resources which must be allocated to treatment (Reference Lopez-Bastida, Ramos-Goni and Aranda-Reneo5). Lopez-Bastida et al. (Reference Lopez-Bastida, Ramos-Goni and Aranda-Reneo5) suggested that where information was lacking about nonmedical costs for rare diseases, it could be excluded from policy making.

Budget Impact

After CE, “budget impact” was the most frequent attribute among the economic factors, and five papers mentioned this attribute (Reference Ollendorf, Chapman and Pearson4;Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin10–Reference Friedmann, Levy, Hensel and Hiligsmann13). According to the Ollendorf et al. (Reference Ollendorf, Chapman and Pearson4) study, for England and Wales, France, and Germany, budget impact thresholds were Pound Sterling 20, EURO 30, and EURO 50 Million per year, respectively. Total costs of insurance coverage of orphan drugs in the first two years in the MCDA context based on the Friedmann et al. (Reference Friedmann, Levy, Hensel and Hiligsmann13) study (as trade-off criteria of decision matrix) were categorized into three groups: budget savings or positive budget impact “below EURO 1.2 Million,” “in the range between EURO 1.2 and 2.4 Million,” and “above EURO 2.4 Million.”

Opportunity Cost and Financial Affordability

This attribute was mentioned in only one study as a factor related to economic aspects of orphan drugs policy making (8).

Disease and Population Characteristics

Disease Severity

Disease severity was used to refer to the pretreatment health state of patients, the more severe the disease, the greater the impact on society, especially on patients and caregivers. Most of the rare diseases can cause morbidity, disability, reduced quality of life, and shorter life expectancy. A large part of these conditions begins during childhood and many of them lead to major disability. Generic health-related quality of life or disease-specific quality of life tools can help to measure this criterion (Reference Richter, Nestler-Parr and Babela1). In the study of the evaluation of orphan drugs in the MCDA framework, the severity of the disease was a high relevance criterion in all studies (Reference Pearson, Rothwell, Olaye and Knight2). In Poland, in order to evaluate priority of fifty-four orphan drugs in comparison with each other, the disease severity was used in an MCDA framework (Reference Gammie, Lu and Babar3).

Disease Burden

The burden of disease, including the prevalence, incidence, life years adjusted based on the disease, predicted health years, economic burden, and other indices related to the burden of disease, was defined as a criterion for priority setting (Reference Ollendorf, Chapman and Pearson4). In several studies, disease burden was one of the criteria used to evaluate orphan drugs (Reference Pearson, Rothwell, Olaye and Knight2;Reference Lopez-Bastida, Ramos-Goni and Aranda-Reneo5).

Population Size

The number of eligible patients is another factor influencing the decision-making process in the field of orphan drugs. In evaluating ten orphan drugs, the criterion of disease population size was used together with other criteria in four European countries (Reference Lasalvia, Prieto-Pinto and Moreno6). Also, in a study performed in Canada, the population size was used in decision making in the field of rare disease drugs (Reference Arksey and O’Malley7).

Disease Effects

This criterion expresses the effects that the disease has on the patient. In a study prioritizing ten orphan drugs in four countries (England, Scotland, Sweden, and France in 2016), the effects of the disease on the patient were considered as one of the evaluation criteria (Reference Lasalvia, Prieto-Pinto and Moreno6).

Disease Rarity

The rarity of the disease by itself as single attribute is not enough to measure value of orphan products; however, the rarer the disease, the more complex its assessment in terms of research and development because evidence is harder to generate (Reference Pearson, Rothwell, Olaye and Knight2). To use this criterion in priority setting, different studies defined rarity based on the prevalence of disease in a certain population. For example, in a European study which evaluated six orphan drugs in the MCDA framework, disease rarity was considered at three levels: (i) 1: 2.000–1: 20.000, (ii) 1: 20.000–1: 200.000, and (iii) less than 1: 200.000 (8). In Poland, to evaluate twenty-seven orphan drugs in comparison with each other in an MCDA framework, disease rarity was studied at three levels: (i) prevalence less than 0.5 per 10,000, (ii) prevalence in the range of 0.5–1 per 10,000, and (iii) prevalence more than 1 per 10,000 (Reference Hsieh and Shannon9).

Unmet Needs

Unmet needs may be recognized when current interventions have serious limitations on efficacy, safety, tolerability, and impact on quality of life. It is highly relevant for orphan diseases, where important therapeutic limitations persist and there are few interventions focused on a specific condition (Reference Pearson, Rothwell, Olaye and Knight2). Unmet medical needs in Poland were studied at three levels: (i) no comparable alternative available, (ii) second-line treatment available, and (iii) at least one comparable alternative available (Reference Hsieh and Shannon9). The unmet need was one of the criteria used in the evaluation of orphan drugs in the MCDA framework in the Netherlands (Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin10). In Spain and Central and Eastern European countries, unmet needs were used as a measure of the value of orphan drugs (Reference Nicod11;Reference Short, Stafinski and Menon12).

Therapeutic Alternatives and Uniqueness of Orphan Technologies

D.1 Availability of Alternative Technology

Absence of therapeutic alternatives represents a predominant difficulty for orphan diseases (Reference Pearson, Rothwell, Olaye and Knight2). In a study in Central and Eastern European countries, the availability of alternative technology in the evaluation of orphan drugs was considered (Reference Short, Stafinski and Menon12). This criterion was used to assess a set of orphan drugs in different studies, especially those conducted under the MCDA framework (Reference Richter, Nestler-Parr and Babela1;Reference Pearson, Rothwell, Olaye and Knight2;Reference Lasalvia, Prieto-Pinto and Moreno6).

Uniqueness

Uniqueness was one of the criteria mentioned in the studies on the evaluation of orphan drugs in the MCDA framework (Reference Lopez-Bastida, Ramos-Goni and Aranda-Reneo5;Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin10). To evaluate twenty-seven pairs of drugs in Poland using the MCDA framework, uniqueness was used at three levels: (i) one unique indication, (ii) more than one orphan indication, and (iii) one or more indications for common diseases (Reference Hsieh and Shannon9).

To evaluate six orphan drugs in the MCDA framework in a study in Europe, this criterion was defined at three levels: (i) existing orphan or nonorphan indication for the same molecule, (ii) potential for multiple indications, and (iii) unique indication or no. In Poland, this criterion was also used in the MCDA framework to test fifty-four pairs of orphan drugs (Reference Gammie, Lu and Babar3).

Quality and Availability of Evidence

Quality of Evidence

Although decision making about orphan drugs and diseases based on particular features like their scarcity and high prices leads to high ICER and budget impacts, their assessment according to HTA criteria can be a challenge (Reference Guarga, Badia and Obach16). So, the quality of evidence, such as the level and the number of studies undertaken and the relevancy, is an important criterion that can contribute to making more accurate decisions (Reference Lasalvia, Prieto-Pinto and Moreno6;Reference Friedmann, Levy, Hensel and Hiligsmann13;Reference Schey, Krabbe, Postma and Connolly18).

Scientific Evidence for Clinical Efficiency

In our reviewed papers, six pointed to this criterion as an important factor for priority setting (Reference Ollendorf, Chapman and Pearson4;Reference Short, Stafinski and Menon12–Reference Kolasa, Zwolinski, Kalo and Hermanowski15;Reference Zelei, Molnár, Szegedi and Kaló19). The quality and quantity of the scientific evidence are limited due to low power from small populations, limited time horizons, and limited diagnostic capacities. It is therefore difficult to confirm the added value of the drug and uncertainty about the efficiency and safety increases. One article, however, mentions that it is possible to undertake an acceptable clinical trial with a small patient population by undertaking sequential, three-stage, or adaptive designs rather than traditional clinical trials (Reference Zelei, Molnár, Szegedi and Kaló19).

Expert Consensus/Clinical Practice Guidelines

Expert consensus refers to the ideas and opinions of an expert panel about the priorities of orphan drugs and diseases. These documents are not evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Because of the limitations in scientific evidence of orphan drugs and diseases which use expert consensus or clinical practice guidelines, European countries have started considering practical criteria for better judgments in decision making such as ensuring an adequate, transparent assessment process and providing a consistent decision support tool for policymaking (Reference Friedmann, Levy, Hensel and Hiligsmann13;Reference Guarga, Badia and Obach16).

Other Social and Organizational Criteria

F.1 Health System Issues

Capacity management in health systems is about the organizational responses to existing demands given limited resources. Due to the scarcity of rare diseases (in form of individual diseases) and the high price of orphan drugs, one of the criteria that was considered in priority setting of orphan drugs and rare diseases in the literature was the system’s capacity and its appropriate use of orphan drugs based on the context of each country (Reference Friedmann, Levy, Hensel and Hiligsmann13;Reference Guarga, Badia and Obach16).

Social, Political, and Legislative Issues

The social impact of rare diseases and orphan drugs, such as the indirect costs imposed on families and caregivers, has been included in MCDA approaches but was often ignored in other HTA approaches (Reference Ollendorf, Chapman and Pearson4;Reference Zelei, Molnár, Szegedi and Kaló19). Because the formal approaches designed for decision making about common health services are problematic in the assessment of orphan drugs, there are other criteria which are considered under MCDA frameworks, especially in European countries: developed national priority, political context, and government legislation that determine governments’ strategies about priority of orphan drugs and rare diseases to reduce the burden of diseases and catastrophic costs (Reference Nicod11;Reference Friedmann, Levy, Hensel and Hiligsmann13).

Fairness and Equity

Equity issues of orphan drugs and rare diseases due to the nature of these diseases (low patient population, high costs, and low health gain) are highly important. Since the ICERs of these treatments are so high and the amounts of health resources are limited, most of them would not fall under standard thresholds of CE. It has been suggested that patients with rare diseases have a human right to treatment raising issues of equity in terms of access to orphan drugs (Reference Zelei, Molnár, Szegedi and Kaló19). Therefore, this criterion has been mentioned as a one of the contextual criteria in new methods of priority setting in determining a social value for orphan drugs (Reference Friedmann, Levy, Hensel and Hiligsmann13;Reference Guarga, Badia and Obach16;Reference Zelei, Molnár, Szegedi and Kaló19).

Discussion

In the era of growth in the development and use of orphan drugs to treat rare diseases, understanding the methods and criteria in priority setting of rare diseases and orphan drugs for policy making such as financing, legislation, and regulation is so important. The review of priority setting literature for orphan drugs and rare diseases showed that setting of criteria is the first and most important step and the rest of the prioritization process is based on these criteria. According to the conducted scoping review, there were numerous studies discussing both methods and criteria for priority setting of orphan drugs and rare diseases. Some studies, especially from European countries, have used various methods such as the MCDA and discrete choice experiment to appraise orphan drugs but the interest in MCDA for comparing cases by using multiple scoring and direct weighting was more frequent (Reference Nicod11;Reference Schey, Krabbe, Postma and Connolly18;Reference Zelei, Molnár, Szegedi and Kaló19). Since there is no consistent framework for decision making and prioritizing these drugs, some studies have attempted to demonstrate the benefits of having a unique framework like Evidence and Value: Impact on Decision-Making (EVIDEM) or to incorporate HTA and MCDA as a new method (Reference Friedmann, Levy, Hensel and Hiligsmann13).

In terms of “health outcomes and clinical implications,” the most frequent attributes in the reviewed studies were identified as safety, clinical benefits or effects, health benefits or effects, efficacy/effectiveness, and the quality of life and uncertainty about efficacy, respectively, and the maximum frequency was related to “safety.” Our results can be compared with research performed by Friedman et al. (Reference Friedmann, Levy, Hensel and Hiligsmann13) who suggested some attributes related to health outcomes for policy making of orphan drugs. These attributes were as follows: “clinical effectiveness,” “effectiveness,”, and “safety,” this research focused on the using of MCDA for appraisal orphan drugs but our research was more comprehensive and considered all methods and criteria for assessment and appraisal of orphan drugs with more details, both of studies acknowledged on safety and effectiveness as the most important attributes related to the health outcomes.

In the section of “economic factors,” the attributes with the highest frequency in the included studies were CE, budget impact, costs, and opportunity cost and affordability, respectively. “Cost-effectiveness” and “budget effect” have the maximum frequency in this theme. Friedman et al. (Reference Friedmann, Levy, Hensel and Hiligsmann13) suggested the CE as the most important of criteria related to “economic factors,” however our research found “budget impact” and “cost-effectiveness” as the most important criteria in this regards.

According to the studies concerning “disease and population characteristics,” “disease severity,” “population size,” “rarity of the disease,” and “unmet needs” are important factors that are considered in making decisions and the maximum frequency was related to “disease severity.” It is better to measure the rarity of the disease according to the prevalence in a certain population (Reference Pearson, Rothwell, Olaye and Knight2;8;Reference Hsieh and Shannon9). Our research and Friedman et al. found “disease severity” as the most important criteria related to “disease and population characteristics.”

In terms of treatment alternatives, “the availability and uniqueness of treatment” is one of the important factors that should be considered in making decisions. Depending on the number of alternatives available and the quality of their treatment, degrees of uniqueness can be determined at several levels. Friedman et al. did not give enough attention to this kind of criteria; our research expressed more details about “the availability and uniqueness of treatment.”

As mentioned in the results section, according to the small size of population, the difficulty to confirm the added value, the limited time horizon, and the limited diagnostic capacities, the power of scientific evidence is limited for orphan drugs and rare diseases, which finally means inability to reach a consensus (Reference Friedmann, Levy, Hensel and Hiligsmann13). Therefore, if the scientific evidence for clinical efficacy and the quality of evidence in this area are increased, expert consensus can be reached more easily and clinical practice guidelines can be developed.

We should consider that the assessment of these criteria depended on the decision method which applied. This point is important because it impacts on the final decisions. As a result, identifying explicit criteria and methods for an adequate evaluation of orphan drugs and rare diseases improves accessibility and affordability of these kinds of medications. As a whole, this study contributes to a better understanding of the methods and the attributing criteria for complex decision making regarding orphan drugs and rare diseases. Since the price of orphan products is so high and its validation and appraisal for reimbursement and coverage are not compatible based on the traditional HTA, it is critical to explore the issue in precise technical methods which consider multiple criteria in priority setting. However, these criteria can lead to different priorities in different countries in accordance with contextual frameworks which show country-specific preferences (Reference Onakpoya, Spencer, Thompson and Heneghan20).

Therefore, we suggest that these criteria be used for developing a robust framework for orphan drugs policy making, as is the case for MCDA and Accountability for Reasonableness (A4R) (Reference Daniels21) which have been discussed in the global literature for general priority setting of health care in the recent years to cope with these complexities. Similar to our results, Friedman et al. found that MCDA has great capacity to be used for orphan drugs reimbursement policy making.

Limitations

In this review, access to the full text of some papers was limited. Hence, we excluded them accordingly. As we performed a scoping review rather than a systematic review, our work did not include a quality review of the identified articles.

Conclusion

Orphan drugs are often costly and traditional methods of HTA are not appropriate for making reimbursement decisions. Alternative methods such as MCDA and A4R may be appropriate in priority setting. Future research in these methods would be beneficial.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462322000393.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.