In 2002, Thailand introduced Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and, since then, the Thai population has been covered under one of the three public health insurance schemes, that is, the Civil Servant Medical Benefits Scheme (CSMBS), the Social Security Scheme (SSS), and the Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) (Reference Hanvoravongchai1). As a consequence, total government health expenditure has dramatically increased and the health insurance schemes have been subject to financial constraints (Reference Vasavid, Janyapong and Greetong2). Health technology assessment (HTA) has been advocated as a necessary activity to ensure efficient use of resources and improvement of coverage decisions. HTA is commonly referred to as a multidisciplinary field of policy analysis that considers technical performance, safety, clinical efficacy and effectiveness, cost and cost-effectiveness, organizational implications, and social, legal, and ethical consequences of the use of a health technology (Reference Velasco, Perleth and Drummond3). Equity, feasibility, budget impact, and sustainability of health financing are also considered in HTA in Thailand (Reference Tantivess4–Reference Teerawattananon, Tritasavit, Suchonwanich and Kingkaew6).

At the country level, HTA has been institutionalized and integrated into policymaking in Thailand, including in the development of the National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM), Thailand's pharmaceutical reimbursement list, as well as the benefits package of the UCS, which is the largest government-financed plan (Reference Tantivess4–Reference Teerawattananon, Tritasavit, Suchonwanich and Kingkaew6). This article explores Thailand's HTA system with a focus on its institutionalization, key elements, and contribution to policy decision making. Although HTA in this setting has been used to inform a wide range of health technology-related policies, this review aims to provide insight to the role of HTA in coverage decisions. Lessons learned from the Thai experience may be helpful for other low- and middle-income countries pursuing evidence-based priority-setting of health interventions.

Methods

A document review was conducted on the institutionalization of HTA, elements of HTA introduction, and the role of HTA in policy decision making in the Thai context. Sources include published articles from Google and domestic databases (until April 2018), and documents selected from the references of retrieved articles and gray literature (i.e., research reports and meeting minutes) in Thai and English. Additional information was collected from the authors’ involvement in the policy decision-making process in Thailand as members and the secretariat of technical working groups under the Subcommittee of the development of the NLEM and the Subcommittee for the development of the Benefits Package and Service Delivery (SCBP). The authors’ direct experiences in the policy decision-making process were also explored.

HTA Institutionalization: Chronological Development

“Institutionalization” refers to the action or process of embedding a concept such as a belief, norm, social role, particular value, or mode of behavior into an organization, social system, or society. As such, institutionalizing HTA is not merely the establishment of an HTA institute; rather, it is the promotion of developing structures and processes suitable for the systematic evaluation of health technologies, which plays a functional role in informing policy and practice at different levels (Reference Rajan, Gutierrez-Ibarluzea and Moharra7). Introducing HTA includes generating evidence and using it in policy making, building the capacity of HTA practitioners (i.e., HTA researchers and others who conduct HTA or use its findings to inform policy making), and developing organizations, system infrastructure, and collaborations. HTA introduction is also influenced by context-specific factors such as political will and leadership, local training on HTA-related disciplines, and adequate resources such as funding, technical expertise, and availability of databases (Reference Chootipongchaivat, Tritasavit, Luz, Teerawattananon and Tantivess8).

Between 1982 and 1996, mainly academics (i.e., researchers and lecturers at universities) and personnel in medical schools that invested in high-cost technologies were concerned about over-investment, poor distribution, and inequity in access to advanced health technologies (Reference Teerawattananon, Tantivess, Yothasamut, Kingkaew and Chaisiri9). Only a few centers for health economics in public universities conducted HTA to guide investment in and rational use of such technologies; however, limitations in capacity, resources, and national policy linkage led to the limited use of HTA evidence during that time. The first attempts to establish an HTA unit at the national level occurred in 1993. The Technology Assessment and Social Security in Thailand was introduced as a program focusing on the use of HTA as a policy tool for public health to inform insurance plans (Reference Tomson and Sundbom10). However, this program failed to scale up and was terminated in 1996 because of insufficient human resources and infrastructure for health economic appraisal.

In 2002, the Universal Health Coverage Scheme was implemented and the government was pressured to include high-cost services in the benefits package while facing budget constraints. In response to a need for HTA and the establishment of HTA institutes (Reference Teerawattananon, Tantivess, Yothasamut, Kingkaew and Chaisiri9;Reference Tantivess, Teerawattananon and Mills11), the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) established its “Health Technology Assessment” unit, currently the Institute of Medical Research and Technology Assessment (IMRTA), an affiliation of the Department of Medical Services (DMS) (Reference Teerawattananon, Tantivess, Yothasamut, Kingkaew and Chaisiri9). Although the institute could not meet increasing demands from sources outside of the department, during this period there were other academics, HTA institutes. and HTA programs that could also provide HTA evidence (Reference Teerawattananon and Tangcharoensathien12). For example, a semi-autonomous research institute of the MOPH's Bureau of Policy and Strategy, namely the International Health Policy Program (IHPP), was established in 1998 (http://www.ihppthaigov.net/). In addition, an international collaborative project, entitled “Setting Priorities using Information on Cost Effectiveness,” managed by the Thai MOPH and the University of Queensland, Australia, was active between 2004 and 2009 (Reference Tantivess, Teerawattananon and Mills11).

As demand for using HTA as a tool of evidence generation to inform coverage decisions of the benefits packages continued to grow (Reference Tantivess4–Reference Teerawattananon, Tritasavit, Suchonwanich and Kingkaew6), significant development in HTA institutionalization occurred in 2007 when the Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Program(HITAP) (http://www.hitap.net/en/) was established as a part of the IHPP. HITAP received funding support from the Thai Health Promotion Foundation, the Health Systems Research Institute (HSRI), and the MOPH to start a wide range of activities for setting up an HTA system for Thai society (Reference Teerawattananon, Tantivess, Yothasamut, Kingkaew and Chaisiri9). Moreover, academics, public HTA institutes/programs, and the private sector cooperated to conduct HTA studies as well as develop the national HTA methodological guidelines, essential infrastructure, and standards (Reference Teerawattananon and Chaikledkaew13–Reference Chaikledkaew and Kittrongsiri17). These were key enabling factors for HTA development in Thailand.

Conducting HTA Studies to Inform Policy Coverage Decisions

Despite limited resources, there is increasing pressure on the government to include new high-cost technologies in all public health insurance schemes. Hence, HTA, mainly cost-effectiveness and budget impact information, plays an important part in coverage decisions, including in the development of the NLEM as well as the UCS benefits package. To conduct HTA to inform the development of these benefits packages, all researchers are recommended to follow the national HTA methodological guidelines. The working group for the Thai HTA guidelines development, which consisted of researchers from HITAP and universities, produced the guidelines. The guidelines were also approved by the SCBP of the National Health Security Office (NHSO) as well as the Subcommittee for the development of the NLEM (Reference Teerawattananon and Chaikledkaew13;Reference Chaikledkaew and Kittrongsiri17).

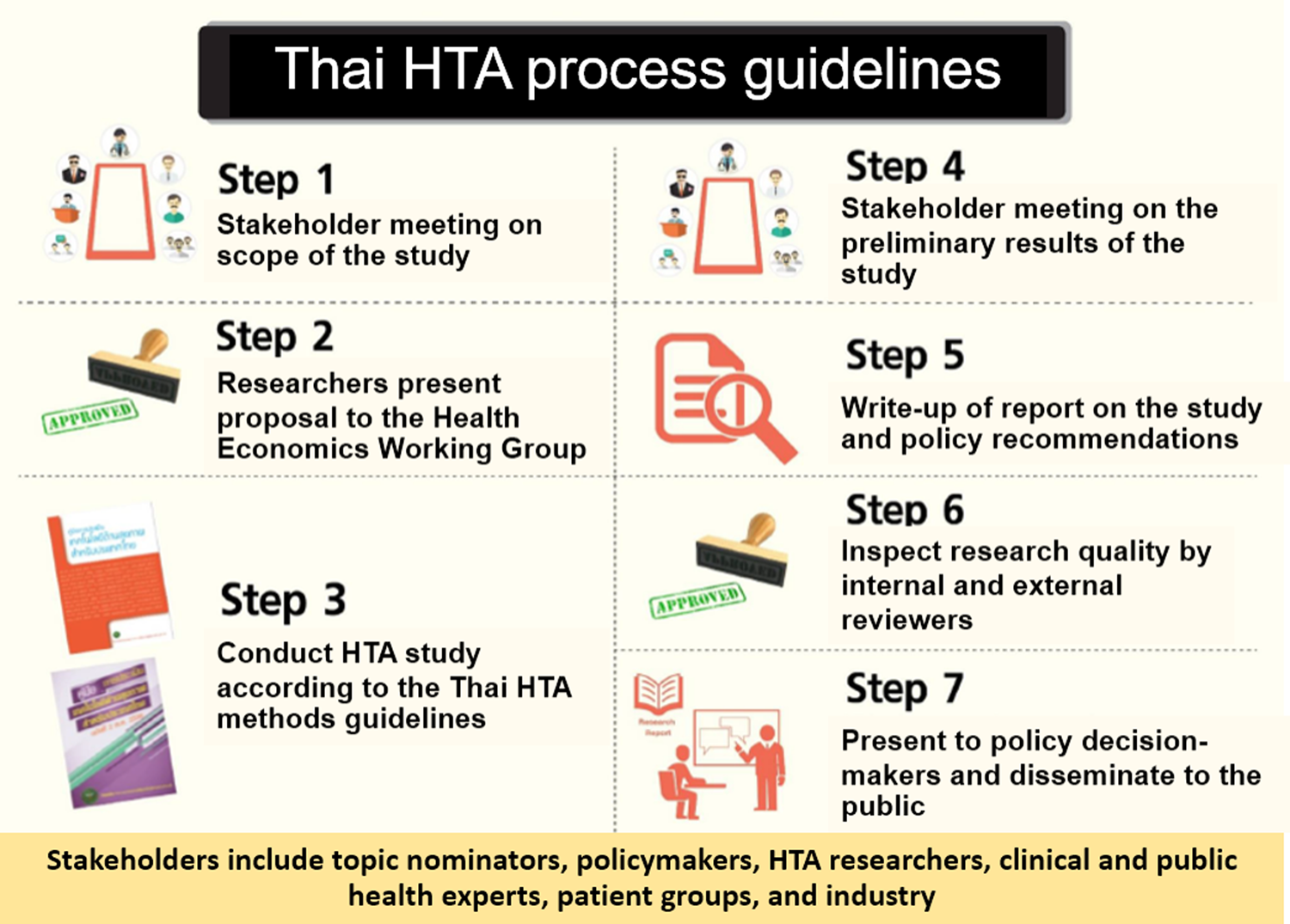

Moreover, the Thai HTA process guidelines were developed with the aim to connect the principles of good governance of HTA research (i.e., transparency, accountability, inclusiveness, timeliness, quality, consistency, and contestability) with the steps of the HTA process through specific mechanisms as shown in Figure 1 (Reference Perez, Chaikledkaew, Youngkong, Tantivess and Teerawattananon15). For the NLEM, if the analysis indicated that a medicine is not cost-effective or unaffordable, a threshold price would be calculated for use in price negotiation. In some instances, however, final decisions on service coverage are attributed to other factors in addition to value for money and affordability. These include, for example, financial burden of households, program feasibility, budget impact, and social, ethical, and equity implications of inaccessible health interventions.

Fig. 1. Thai health technology assessment (HTA) process guidelines.

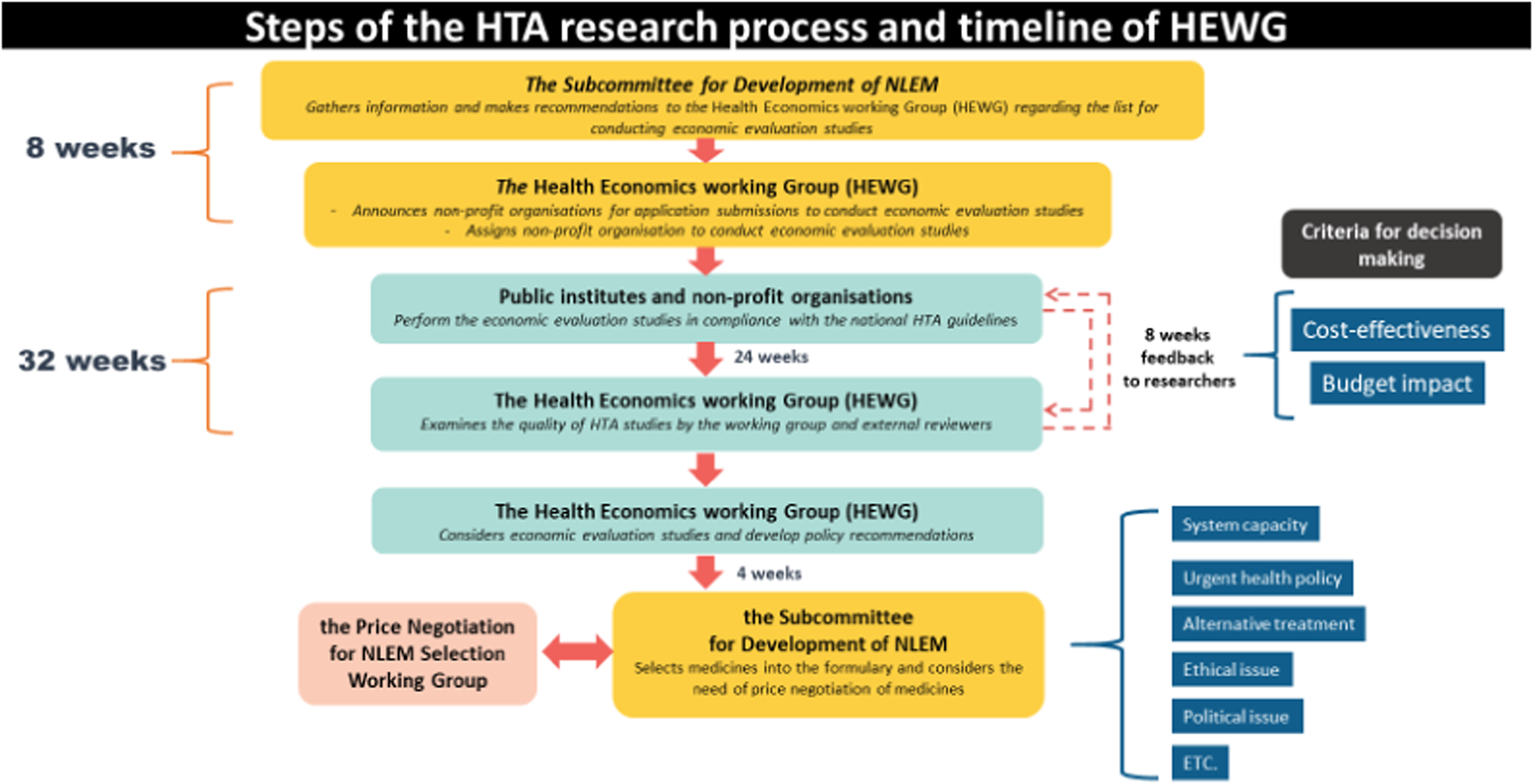

Role of Health Technology Assessment in the Development of the Pharmaceutical Reimbursement List

The NLEM was adopted into the three major health schemes as a reimbursement list of pharmaceuticals, including biological products. Since 2008, economic evaluation and budget impact analysis have been conducted to revise the list of high-cost drugs in the NLEM following the process shown in Figure 2 (Reference Teerawattananon, Tritasavit, Suchonwanich and Kingkaew6). New medicines proposed by clinical specialists, departments of the MOPH, and the pharmaceutical industry are reviewed for their safety, effectiveness, recommendations in clinical practice guidelines, quality, and health needs in the Thai setting. Comprising health economics experts, the Health Economics Working Group (HEWG) is responsible for commissioning economic evaluation and budget impact analysis, and ensuring research quality (Reference Teerawattananon, Tritasavit, Suchonwanich and Kingkaew6). The evaluations and evidence generation are carried out by researchers in universities and independent research institutes. In the final step, the NLEM Subcommittee decides whether the new medicines will be included in the list after considering cost-effectiveness and budget impact information as well as social factors such as equity and other ethical issues. It should be noted that since 2016, private, for-profit businesses are no longer commissioned by the HEWG to conduct assessments of its own product submissions.

Fig. 2. Steps of the health technology assessment (HTA) research process and timeline of the Health Economics Working Group (HEWG). NLEM, National List of Essential Medicines.

From 2001 until present, the total number of new medicines that have been evaluated for cost-effectiveness and budget impact is approximately 40 (details in Supplementary Table 1). A majority of these medicines are patented, high-cost, and of advanced technology, indicated for particular patients who require attention from sub-specialty prescribers. To ensure affordability of and equitable access to some of these medicines, both HTA information and new purchasing models, such as price-volume agreement, risk-sharing, and voluntary licensing, have been introduced through collaborations between public health authorities and pharmaceutical companies (Reference Teerawattananon, Tritasavit, Suchonwanich and Kingkaew6).

Role of HTA in the Development of the UCS Benefits Package

The Subcommittee for the development of the Benefits Package and Service Delivery (SCBP) is the body that provides recommendations on which health service interventions should be included in the UCS benefits package to the National Health Security Board (NHSB). Before 2009, any stakeholder could propose new services to the NHSO, leading to a large number of proposals made by various groups. This resulted in inconsistent levels of evidence quality due to influences from expert opinions and medical case reports. Furthermore, vested interests of high-level authorities could have affected coverage decisions (Reference Tantivess4). The NHSO understood the growing political economy pressures given the rising demand for high-cost and innovative interventions among UCS beneficiaries.

Consequently, the SCBP approached HITAP and IHPP to serve as its technical focal points and to develop the process for revising the UCS benefits package. It requested for the process to be systematic, transparent, participatory, and evidence-based (Reference Chaikledkaew and Kittrongsiri17). The process developed has three major steps as follows: select topics, conduct HTA study, and present results and policy recommendations (Reference Mohara, Youngkong and Velasco5). From 2010 to 2015, a total of 133 topics were nominated by seven stakeholders, of which sixty-five topics were selected for HTA and forty-five studies were completed. However, as of the end of 2016, results from only twenty-six completed studies were selected for presentation to the SCBP. The results of all prioritized intervention appraisals that were presented to the SCBP is shown in Supplementary Table 2.

In early 2017, the process for the development of the benefits package under the UCS was modified (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. The use of health technology assessment (HTA) in the development of the benefits package under the Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) in 2017. HEWG, Health Economics Working Group; HSRI, Health Systems Research Institute; NHSB, National Health Security Board; SCBP, Subcommittee for the development of the Benefits Package and Service Delivery.

The SCBP formulates coverage policies and strategies, especially for the development of benefits packages. The packages include not only pharmaceuticals and vaccines, but also health services, medical devices, screening and diagnostic tests, surgical procedures, and health promotion interventions. Seven groups of stakeholders (Figure 1) nominate and prioritize topics organized by the HEWG under the SCBP based on certain criteria (Reference Mohara, Youngkong and Velasco5). Similar to the process of the HEWG of the NLEM, researchers from public institutes and nonprofit organizations can contribute to the assessments. The HSRI is responsible for funds provision and quality assurance, and a final decision is made by the NHSB. The SCBP has used HTA results from studies conducted by academic institutes as technical evidence to inform decision making.

Essential Elements for HTA Introduction

This article applies the four-element framework of the essential elements for HTA introduction, namely governance and underlying values, HTA practitioners and capacity building, data and information, and funding sources (Reference Chootipongchaivat, Tritasavit, Luz, Teerawattananon and Tantivess8). The four-element framework was extracted from a policy brief and working paper entitled “Factors conducive to the development of health technology assessment in Asia: impacts and policy options,” a collaboration between the Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (http://www.searo.who.int/entity/asia_pacific_observatory/about/en/) and the Prince Mahidol Award Foundation, Thailand (http://www.princemahidolaward.org/) (Reference Chootipongchaivat, Tritasavit, Luz, Teerawattananon and Tantivess8). The working paper was based on document review and group discussions on the experiences of six well-established HTA settings in Asia, including China, Indonesia, the Republic of Korea, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Governance and Underlying Values

Thailand's HTA governance is not well established, especially for the core functions of the whole system which include coordination, standardization of research methods and processes, strategic planning, and resource mobilization for capacity development. However, at the operational level, more explicit governance for HTA introduction has existed, despite fragmentation. Examples include the development of the NLEM and the UCS benefits packages, which illustrates effective stewardship, stakeholder participation, deliberation, transparent processes, systematic use of quality evidence, and contestability. In both cases, the policy makers highly value transparency, participation, and accountability of HTA processes (Reference Mohara, Youngkong and Velasco5). The committees, research teams, and other players are encouraged to follow the recommendations of the national HTA guidelines (Reference Teerawattananon and Chaikledkaew13;Reference Perez, Chaikledkaew, Youngkong, Tantivess and Teerawattananon15;Reference Chaikledkaew and Kittrongsiri17). At the same time, social values like efficiency, fairness, equity, and responsiveness are among crucial concerns when decisions are made regarding particular technologies or interventions (Reference Perez, Chaikledkaew, Youngkong, Tantivess and Teerawattananon15).

Regarding the governance of a public HTA agency, a case study can be drawn from the IMRTA. Its policy framework, planning, and actions are explicit and subjected to official budgeting, monitoring, and evaluation. The IMRTA is responsible for building medical research and HTA capacity, which includes the development of research guidelines, training for researchers, and knowledge translation (18). HTA-related activities fall under the scope of the DMS and its associated tertiary hospitals. In some instances, the DMS clinical practice guidelines and recommendations, guided by IMRTA's research, play a role in informing national policy formulation and medical professional practice. In contrast to HITAP, the IMRTA has secured long-term funding for research, capacity building, and other HTA-related activities. Nevertheless, information on its performance and contributions to policy and HTA systems development is limited.

HTA Practitioners and Capacity Building

To respond to the growing demand of HTA in Thailand, extensive knowledge of HTA became necessary for decision makers and researchers, particularly within decision-making bodies that use HTA results and for researchers that conduct HTA-related studies. Such researchers may sit within research institutes, HTA units established in university hospitals, and departments in universities (i.e., Pharmacology, Economics, Social Sciences, and Public Health). However, the number of practitioners is insufficient, especially in terms of linking HTA study results to policy decision making at the national level. To address this, short course trainings and postgraduate trainings, including international programs, are available to increase HTA capacity. Moreover, on-the-job training and apprenticeships are offered in HTA agencies, which recruit junior researchers as full-time staff to work with mentors. Junior staff that are capable and committed are supported to study doctorate courses locally and abroad, specializing in HTA-relevant degrees.

Data and Information Necessary for Health Technology Assessment

To assess health technologies in Thailand, a range of factors including clinical effectiveness and safety, cost-effectiveness and budget impact, and social and ethical aspects (Reference Tantivess4–Reference Teerawattananon, Tritasavit, Suchonwanich and Kingkaew6) are considered. Data and information needs are dependent on differences in types of studies, outcomes or impacts of interest, and levels of implementation. The fundamental system for HTA studies (e.g., HTA guidelines for methods and processes, standard cost list, health-related quality of life [HRQoL] measurement) was developed to help researchers choose appropriate methodologies and data sources for their HTA studies (Reference Teerawattananon and Chaikledkaew13;Reference Perez, Chaikledkaew, Youngkong, Tantivess and Teerawattananon15;Reference Chaikledkaew and Kittrongsiri17). For evaluations of clinical effectiveness and safety, a systematic evidence synthesis of international and local literature is recommended, which can be carried out using relevant electronic databases that can be accessed in public universities.

In addition, important data that are used for cost-effectiveness and budget impact analyses include baseline clinical data, resource use, cost, and HRQoL, which require access to health service provision records and primary data. At the national level, the NHSO and MOPH health data centers that contain information on various target populations can only be accessed following authorization due to the standards of individual data protection. As a result, HTA researchers sometimes have difficulty accessing and analyzing this data. Similarly, accessing primary data and review of medical records are likely to be time-consuming and resource-intensive because the patient registry systems in Thailand are very limited and not well-developed. Furthermore, the assessment of social and ethical aspects has been challenging due to a lack of explicit standardized methodological guidelines and methodological experts for such matters. Nevertheless, social and ethical considerations have been used to justify the inclusion of health interventions in country benefits packages (Reference Tantivess4–Reference Teerawattananon, Tritasavit, Suchonwanich and Kingkaew6). As a result, HTA researchers would include a discussion of these issues in their reports, in cases wherein health technologies may have social and ethical consequences (Reference Tantivess19).

Funding Sources

In 2007, the HSRI, MOPH, and Thai Health Promotion Foundation (ThaiHealth) provided a budget for HTA systems development (Reference Teerawattananon, Tantivess, Yothasamut, Kingkaew and Chaisiri9). In the years that followed, the main users of HTA evidence such as the MOPH, NHSO, and ThaiHealth made financial resources available for evidence generation to inform policies related to the areas of their mandates or interests. However, there is still insufficient funding for other essential HTA activities, including capacity building, developing HTA strategies and systems, and dissemination. This is a result of a lack of governance structure and policy for HTA systems development. Only organizations that support research, such as the HSRI and Thailand Research Fund, offer grants for conducting HTA-related research, capacity building, and dissemination.

Discussion

A literature review of the chronological development of HTA institutionalization and essential elements of HTA introduction was performed. First-hand experiences from the authors who play roles as members or the secretariat of technical advisory groups under the Subcommittees for coverage decisions in Thailand revealed the existing role of HTA to inform the policy decision-making process as well as previous coverage decisions of health technologies under the Subcommittee for pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical reimbursement packages (Supplementary Tables). The enabling factors and key challenges of HTA institutionalization in the Thai context are discussed in the following sections.

HTA Institutionalization: Enabling factors

In Thailand, the enabling factors for the formal integration of HTA into priority-setting can be categorized into four groups. First, the introduction of the UCS in 2002 as the country's largest health benefits program enhanced the use of evidence. Universal coverage decisions are highly political, especially in resource-constrained settings, as such policies can have substantial effects on health expenditures as well as determine access to particular health services among large numbers of people in need. HTA was adopted to address the concerns of the UCS’ growing budget requirement and its sustainability. As asserted by Hanvoravongchai (Reference Hanvoravongchai1), “The UCS contributed significantly to strengthening the health technology assessment capacity in response to its demand for evidence for benefits package decisions.”

Second, the legacy of health systems reforms, taking place in the 1980s onward, has contributed to the development of health policy and systems research (HPSR) capacity. It marked a systematic reform process, which applied the use of evidence-based research as the main tool to reform the health system, and it served as a learning mechanism for both policy makers and stakeholders (Reference Phoolcharoen20). Regarding HPSR capacity, the HSRI was established in 1992 to promote high quality HPSR and knowledge transfer that impacts policy decisions on priority issues, including health financing, rational use of medicines, health systems governance, and health of vulnerable populations. Collaborations for improving evidence generation, policy monitoring, and information platforms between MOPH's departments, autonomous health agencies, the National Statistical Office, universities, research institutes, and funding agencies have also been strengthened. In addition, stakeholder participation in health policy has become a norm or tradition, as partly reflected in the convention of the National Health Assembly since 2008 and similar forums at the provincial and district levels thereafter (Reference Swanson, Cattaneo and Bradley21;Reference Rasanathan, Posayanonda, Birmingham and Tangcharoensathien22). These consultation venues empower policy makers, key actors, and the public because it enables learning about participatory policy processes and different types of evidence. It can be argued that such experiences increase the feasibility of involving stakeholders in coverage decisions using HTA (Reference Slutsky, Tumilty and Max23).

In addition, as policy makers are concerned about evidenced-based policy decisions, transparency, participation, and accountability of HTA processes (Reference Mohara, Youngkong and Velasco5), it is a challenge for HTA practitioners to foster engagement and participation of a broad range of stakeholders (Figure 1). The Thai HTA process guidelines suggest a mechanism to engage HTA stakeholders based on a review of international experiences and good HTA governance framework (Reference Perez, Chaikledkaew, Youngkong, Tantivess and Teerawattananon15). HTA practitioners are encouraged to manage and balance transparency and inclusiveness on behalf of multidisciplinary stakeholders who are engaged in the HTA process from selection and priority of topics to fine-tuning policy recommendations. This leads to well-accepted HTA findings and greater legitimacy for policy making. Moreover, the effective collaboration between HTA practitioners and stakeholders has built up the link between evidence and policy (Reference Chootipongchaivat, Tritasavit, Luz, Teerawattananon and Tantivess8).

The third and fourth elements, which are international collaborations and global policy, are interconnected and play a supportive role to the Thai HTA. To cope with the rising demand for new interventions and political economy pressures, policy makers searched for similar experiences and solutions in developed countries and adopted the United Kingdom's priority-setting model, that is, commissioning independent HTA units to conduct economic evaluation of the newly- proposed benefits. In addition, the global policy environment has been an important factor that legitimized HTA introduction in the Thai setting. This includes, for instance, the World Health Assembly resolutions on HTA in support of UHC, endorsed in 2014. The resolution has been mentioned by HTA supporters when discussing the rationale of evidence-informed policy, including coverage decisions (24). This is because both the MOPH and NHSO continually promote HTA and evidence-based UHC policies in international forums. Thus, terminating HTA introduction in the country would be regarded as an inexplicable politically oriented action.

HTA Institutionalization: Key Challenges

Despite the above-mentioned conducive factors, HTA introduction in Thailand faced several challenges. First, the absence of a governing body and strategic plan for HTA systems development led to the lack of a formal mechanism to mobilize financial support and harmonize plans and activities. Without this, it is difficult to synergize the system's strategies and normative activities. The second challenge has been the turnover of staff in nonprofit HTA institutes. The monitoring and review of human resources strategies for HTA, that is, recruitment, retention, management, and development, in both government and for-profit sectors should be carried out by respective agencies to stimulate long-term planning and meet the policy demand.

The third challenge involved the rising trend of advanced biotechnologies. It is anticipated that, in the near future, access to these interventions and related services will be in high demand. Collaborations between technology sponsors and providers, and regulators (of professional practice, products, and services) are necessary for determining associated risks, health benefits, and quality (Reference Velasco, Chaikledkaew, Myint, Khampang, Tantivess and Teerawattananon25). The collaborations should extend to the health schemes and HTA research institutes, as common assessment protocols and data sharing are needed. Additionally, the capacity of HTA research teams for evaluation of these innovations should be strengthened.

In conclusion, HTA in Thailand has been developed and plays an important role in evidence-based healthcare decision making. However, the key elements of HTA institutionalization should be strengthened, especially the existence of a governance structure and policy for HTA systems development, building and retaining capacity of HTA practitioners to meet increasing demands, and addressing the challenges of complex and highly innovative health interventions. Lessons learned from the Thai experience may be used as guidance to pave the way toward HTA institutionalization in other low- and middle-income countries.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462319000321

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.