Background

Health Problem at Stake

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD), also called autumn–winter depression, usually begins in autumn/winter and ends again in spring/summer (Reference Rosenthal, Sack, Gillin, Leway, Goodwin and Davenport1). According to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10), SAD is a subtype of major depressive disorder (MDD) with a seasonal pattern (2). According to the American classification system Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), SAD occurs when depressive episodes occur for at least two consecutive years and cannot be explained by other circumstances, such as the loss of jobs for seasonal workers (3).

SAD patients not only suffer from typical symptoms of depression such as depressed mood, lack of drive, or loss of interest and joylessness (Reference Tam, Lam, Robertson, Stewart, Yatham and Zis4), but they also often suffer from atypical symptoms such as anger attacks, hypersomnia (in 70–90 percent of SAD patients), increased appetite (in 70–80 percent), carbohydrate craving (in 80–90 percent), and weight gain (in 70–80 percent) (Reference Pail, Huf, Pjrek, Winkler, Willeit and Praschak-Rieder5). Most SAD patients experience mild-to-moderate depressive episodes and are less likely to experience suicidal ideations than nonseasonal MDD patients. Nonetheless, SAD continues to have a major impact on patients’ private and professional lives (Reference Rastad, Wetterberg and Martin6;Reference Partonen, Rosenthal and Partonen7). In general, the prevalence of SAD is higher in the north than in the south. In Europe and in the United States, the prevalence of SAD ranges between 1 percent and 10 percent. Long-term studies suggest that 22–42 percent of patients diagnosed with SAD still have SAD 5 to 11 years after diagnosis. Furthermore, 33–44 percent of SAD patients progress into a nonseasonal depression, whereas in 14–18 percent of SAD patients, the depressive symptoms disappear completely (Reference Magnusson and Partonen8;Reference Schwartz, Brown, Wehr and Rosenthal9).

Technologies at Stake

Because of the fact that depressive episodes in SAD patients start in autumn/winter, a connection between the development of SAD and the decrease in hours of sunshine is suspected. The absence of sunlight could have an impact on the circadian rhythm, hormones, and the levels of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, norepinephrine, or serotonin (Reference Levitan10). Light therapy and vitamin D therapy are thus two technologies at stake in this analysis. The list of comparators considered is placebo, no intervention, second-generation antidepressants, and psychotherapy.

Light Therapy

Due to its similarity to natural daylight, white fluorescent light (with ultraviolet radiation filtered out) is used most frequently for light therapy. SAD patients are recommended to carry out light therapy with an illuminance of 10,000 lux for about 30–45 min a day (Reference Terman and Terman11)—ideally in the morning right after waking up (Reference Levitan12). The form of light therapy varies and the forms included in this analysis are light lamps (placed at a distance of 50–80 cm from the head), light devices (attached directly to the head), or light rooms (in which patients physically stay). It is important that SAD patients have their eyes open during light therapy, because the light is processed via the retinohypothalamic tract (Reference Pail, Huf, Pjrek, Winkler, Willeit and Praschak-Rieder5). Light therapy is expected to take effect after a few days to weeks and it is recommended to be carried out continuously in the winter months, as stopping it may lead to the return of depressive symptoms (Reference Partonen, Rosenthal and Partonen7).

Vitamin D Therapy

Vitamin D is partly ingested through food, but for the most part, it is formed in the skin as a result of UV-B radiation from sunlight. It is, therefore, assumed that in the decrease of sunlight in the autumn/winter months, the lack of vitamin D may be related to SAD. In the present analysis, vitamin D therapy with vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) (the most important physiological form of vitamin D) in various dosage forms (tablets and drops) and doses was examined.

This present article is the ethics chapter from a full health technology assessment (HTA) commissioned by the Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen (IQWiG) and carried out by the Donau-Universität Krems in cooperation with the Austrian Institute for HTA and the University of Freiburg (Reference Nussbaumer-Streit, Titscher, Kaminski-Hartenthaler, Strohmaier, Stanak and Zechmeister-Koss13). The full HTA results will be submitted to a peer-reviewed journal separately (excluding this detailed ethics chapter). The present ethics analysis uses the revised Socratic approach (Reference Hofmann, Droste, Oortwijn, Cleemput and Sacchini14) to analyze the interventions of light therapy and vitamin D therapy for SAD patients. It aims to highlight the overt and covert value issues with regard to the two health technologies, the disease, and the process of conducting the HTA itself and hence to inform the decision makers about the relevant value issues present in the HTA. The concrete ethical issues found concern the target patient population (vulnerability and beneficence), the disease (SAD as a disease, stigma, underdiagnosis, medicalization, and autonomy), the interventions and the comparators at stake (harm-benefit ratios), and the methodological limitations related to the assessment process.

Methods

Selection of Literature Used for the Ethics Analysis

Because ethical issues are independent of publication type, status, and study type, no limitation on the literature source was applied. Journal publications, monographs, project reports, but also relevant information on the Web sites of interest groups were considered in the ethics analysis. Throughout the text, the term ethical issue refers to any aspect related to the interventions, the disease, or the assessment process that is of ethical relevance. That is to say that it concerns ethical values, norms, or principles. Concerning ethical values, what is mostly meant is that an aspect of the health technology may not realize a value or impede access to a value (e.g., self-determination). Concerning norms and principles, what is mostly meant is that an aspect of the health technology may violate a norm or principle (e.g., respect for patient autonomy).

Data Gathering

For the sake of finding the relevant overarching ethical issues, the revised Socratic approach of Hofmann et al. was applied (Reference Hofmann, Droste, Oortwijn, Cleemput and Sacchini14). The approach provides a set of questions that may assist in identifying overarching ethical issues with respect to the intervention, the disease, the patient group and other interest groups, as well as the actual assessment process of the health technology. The authors went through the set of questions and identified the relevant overarching ethical issues. The authors considered all questions from the revised Socratic approach and the decision on which ones were relevant was resolved by discussion.

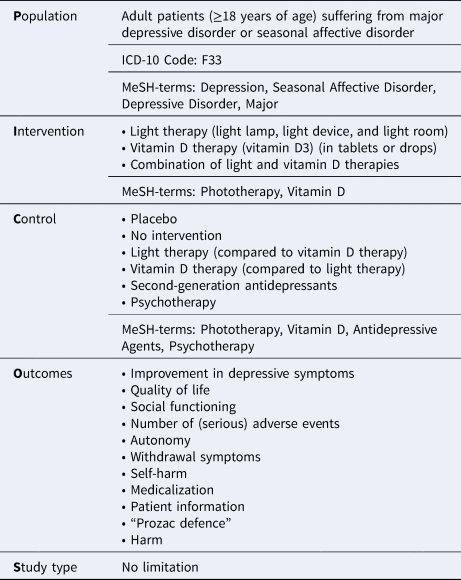

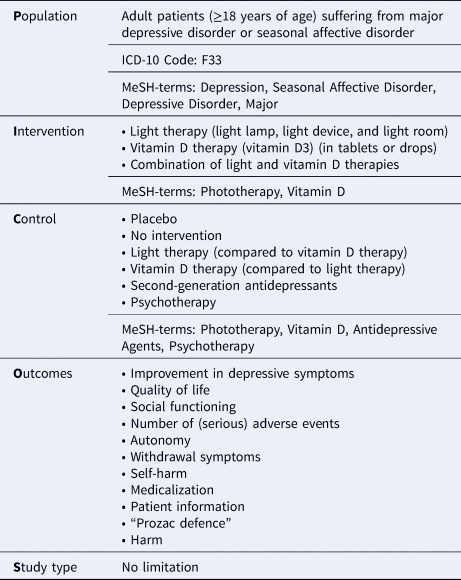

Subsequently, once we identified the overarching ethical issues, we conducted an exhaustive hand search and a search for grey literature on the Web sites of interest groups. Because no articles were found that would specifically focus on the ethics of the two therapies and the disease, a comprehensive systematic literature search was conducted between 12 and 14 February 2019 in MEDLINE via OVID, CINAHL, ETHICSWEB, EthxWeb, PsychINFO, Belit, and Scopus. The search was not limited to the years of publication but was limited to sources published in English or German. The inclusion criteria for literature selection were defined using a Population-Intervention-Comparison-Outcome-(Study design) (PICO) model shown in Table 1. The search was kept broad for the sake of not missing out on articles related to the ethics of SAD and the two technologies at stake.

Table 1. PICOs inclusion criteria

Furthermore, the studies included in the assessment of clinical benefit and the economic assessment of the full HTA were screened for ethically relevant issues.

Data Analysis

Gathering of all data and screening of all abstracts found by the systematic literature search was done by one person (MS). The selection of full texts from the systematic literature search was confirmed by a second person (CS). All concrete ethical issues necessary for the preparation of the ethics analysis were extracted in Table 2 by MS, which is structured as follows: (i) overarching questions from the revised Socratic approach, (ii) concrete ethical issues, and (iii) explanation/quote/reference. All the concrete ethical issues were constructed around the overarching questions set forth by the revised Socratic approach.

Table 2. Identified ethical issues

Results

The systematic literature search resulted in a total of 1,063 hits and the search strategies can be found in the Supplementary material. Data from a total of thirty-three documents were extracted for the purposes of the ethics analysis, and quotations from the relevant publications can also be found in Table 2.

Identified Ethical Issues

Based on the revised Socratic approach (Reference Hofmann, Droste, Oortwijn, Cleemput and Sacchini14), we were primarily able to identify concrete issues related to disease and target groups, with only a few ethical issues related to the interventions. However, understanding the value context in which the interventions apply is particularly important. There were no studies found that would directly report on the ethics of SAD, but as SAD is defined by ICD-10 as a subtype of MDD or bipolar disorder, ethical issues related to depression in general were taken to be on a par with particular SAD issues. This is also because of a pathophysiology model of SAD that assumes a dual vulnerability where “SAD develops when an individual has a combination of significant seasonal physiological symptoms (e.g. energy, sleep, appetite) [seasonality factor] and a vulnerability to develop secondary depression symptoms (e.g. low mood, guilt, anxiety, rumination) [depression factor]” (Reference Enns, Cox, Levitt, Levitan, Morehouse and Michalak21). Individuals who have the depressive factor markedly higher than the seasonal one may not show the pattern of SAD because of their vulnerability to distress that “may manifest as non-seasonal depressive episodes (and other forms of psychopathology)” (Reference Enns, Cox, Levitt, Levitan, Morehouse and Michalak21).

Ethical Issues Concerning the Target Patient Population

Vulnerability

As SAD is argued to have a major impact on the everyday functioning of a patient (Reference Pail, Huf, Pjrek, Winkler, Willeit and Praschak-Rieder5), the vulnerability of the SAD patient group is of particular ethical relevance here. Vulnerability is understood here as a quality of being able to be easily hurt or simply being at a higher risk of harm or wrong. According to Winkler et al., SAD affects approximately twice as many women as men, the onset is in early adulthood, and approximately half of the cases have a family history of psychiatric disease (Reference Winkler, Praschak-Rieder, Willeit, Lucht, Hilger and Konstantinidis19). Also, SAD patients tend to “exhibit comorbidity with other disorders linked to serotoninergic dysfunction, like premenstrual syndrome, alcohol abuse, and overweight” (Reference Wallin and Rissanen20). SAD patients are, furthermore, vulnerable due to the disease's negative influence on individuals’ health-related quality of life, their social functioning, and their employment status due to the frequency of sick leave being 0.36 days a month according to IC0-10 (Reference Rastad, Wetterberg and Martin6;Reference Guajardo, Souza, Henriques, Lucia, Menezes and Martins40;Reference Pjrek, Baldinger-Melich, Spies, Papageorgiou, Kasper and Winkler41). Concerning employment and depression in general, people with depression are “twice as likely to be unemployed. They also run a much higher risk of living in poverty and social marginalization” (16).

Beneficence

The ethical imperative to treat depression is rooted in the principle of beneficence, which holds that there is an obligation for healthcare professionals to act in the best interest of patients. There is a need to treat depression because if goes untreated, it becomes increasingly debilitating—possibly resulting in brain damage caused by toxic levels of stress hormones (16;Reference Preston44) and increased risk of ischemic heart disease and myocardial infarction (Reference Kemp, Malhotra, Franco, Tesar and Bronson45). It is particularly important due to the long-lasting nature of SAD as outlined above (Reference Magnusson and Partonen8).

Ethical Issues Concerning the Disease

SAD as a Disease?

There is a certain ambiguity regarding the existence of the disease (Reference Winkler, Pjrek, Spies, Willeit, Dorffner and Lanzenberger46)—depression in general and SAD in particular—that is of ethical relevance. On the one hand, stands the biological explanation from above that SAD patients suffer from both the seasonal factor—coming with the change of autumn–winter seasons and the depressive factor—meaning that they develop secondary depression symptoms as a reaction to SAD (Reference Enns, Cox, Levitt, Levitan, Morehouse and Michalak21). On the other hand, however, stands the general experience of winter fatigue that is experienced by many and the social theory of depression that interprets depression as a social bias against mildly dysthymic individuals (Reference Martin47). The argument is that depression is a result of the society creating norms that favor outgoing, friendly, and nondepressed personalities and that depression is potentially a normal response to pathological social structures (Reference Martin47). Hence, rather than curing normal emotional responses, it can be argued that we should change the disintegrating community structures (Reference Kramer24;Reference Martin47). The reason why this ambiguity is ethically relevant is that it concerns societal norms or values that may be implicitly at play when diagnosing and then treating individuals with SAD or depression. Such inappropriate diagnosis may lead to inappropriate treatment that may result in unnecessary harm. Furthermore, the nonacceptance of SAD as a disease may have negative implications such as a lack of societal acknowledgment of SAD-related suffering or social inequality with respect to lacking access to covered SAD treatments.

Stigma

Concerning SAD and the experience of winter fatigue, SAD patients report a lack of awareness of SAD among physicians and especially, among general practitioners (Reference Nussbaumer-Streit, Pjrek, Kien, Gartlehner, Bartova and Friedrich15). Such a lack of awareness may be a contributing factor to patients’ self-stigma as patients themselves report doubts whether listlessness, social withdrawal, and depressed mood are a normal part of winter (Reference Nussbaumer-Streit, Pjrek, Kien, Gartlehner, Bartova and Friedrich15). The physicians’ lack of knowledge combined with the SAD patients’ potential self-stigma may mean that opportunities to recognize and treat SAD are missed (16). The potential social barrier is also materialized in the form of lacking insurance coverage of SAD treatments and is well depicted in the Swedish context where patients diagnosed with SAD report experiencing “a dilemma because they knew the diagnosis [SAD] and the treatment [light therapy] were not considered legitimate in the Swedish health care” (Reference Rastad, Wetterberg and Martin6). “There is [furthermore] a well established link between depression and negative self-evaluations, including lowered self-esteem” (Reference Brosse, Sheets, Lett and Blumenthal29) and the ambiguity regarding the existence of SAD has the potential to contribute to it even more.

Underdiagnosis

In light of the above, depression advocacy groups argue that such a lack of awareness would be unacceptable in any physical disease area (16). This is because a lack of awareness may lead to underdiagnosing SAD as a disease and, by implication, undertreating it. They argue on the grounds of fairness saying that a similarly severe case of a physical disease would receive more attention and thus would be less underdiagnosed. In general depression, it is furthermore estimated that only 25–33 percent of depressed patients seek treatment (Reference Preston44) and the appropriateness of the care pathway for those who do seek it is scrutinized. Illustrated by the US context, “85% of prescriptions…for antidepressants are written by physicians and nurses that do not have specialty training in psychiatry … [and] … only 11% of those treated for depression in primary care receive adequate treatment (in terms of dosing, time to response, and follow-up)” (16).

Medicalization

The question of underdiagnosis, however, needs to be put into contrast with the question of medicalization in order to avoid human conditions to be defined and treated as medical conditions. To the extent that SAD is just a form of winter fatigue that the patient can cope with without the need of healthcare support, we should resist the treatment imperative to medicalize normal reaction to winter just because of the fact that there is an adequate treatment for SAD (Reference Lidz and Parker26). Kramer suggests that we should avoid cosmetic pharmacology where medicines are used as mood elevators, as opposed to cures for pathological conditions (Reference Kramer24;Reference Martin47). Furthermore, with the aim of avoiding medicalization, it is suggested that depressed patients first go see a nonphysician clinician who evaluates whether medications from a psychiatrist are necessary (Reference Riba38).

The question of medicalization is also relevant in the context of religious views of depression. Religious perspectives may tend to see depression as a form of spiritual exercise as in the case of the Jesuit priest Moorehead who interpreted his experience with depression in the context of laziness, spiritual pride, or moral weakness—the affliction the Catholic Church once called acedia (Reference Callaghan and Ryan28). Religious understanding of depression may thus see it as a moral matter “when it is a potentially meaningful encounter with troubled relationships, activities, values and self-respect” (Reference Martin47). In this respect, the religious interpretation may provide a sense of purpose for the experience of depression-related suffering.

Autonomy

One of the key ethical issues related to the experience and treatment of depression is associated with the notion of autonomy and the related challenges with authenticity and capacity for decision-making. Broadly speaking, the principle of autonomy here refers to individuals’ capacity to make decisions for themselves that are aligned with their goals and it is understood as a precondition for holding individuals morally responsible for their actions. The experience of pathological depressive symptoms damages autonomy (in the sense of capacity to make decisions) by “reducing energy, enthusiasm, concentration, hope, optimism, self-esteem, and self respect” (Reference Kramer24;Reference Martin47). The autonomous and authentic self that faithfully represents its values, desires, or life plans over time is precisely what health care aims to restore (Reference Lidz and Parker26;Reference Cassell27). However, in the case of depression, the question of authentic personality is particularly problematic. Although an essentialist view of authenticity sees only one true self that the anti-depression interventions are to restore, the process view acknowledges that the self is not a given and hence it changes all the time (Reference Kramer24;Reference Martin47). With respect to the latter view, it is problematic to decide what self is to be restored or maintained—especially in the light of the self that changed through the use of antidepressants. For the sake of making autonomous and authentic decisions for which patients can bear moral responsibility, it is argued that individuals must possess a certain minimum standard of decision-making capacity, which may pose a challenge to patients at the heart of their depressive episodes (Reference Callaghan and Ryan28).

Ethical Issues Concerning Interventions

Benefit-Harm Ratio of the Interventions at Stake

Even though both interventions (light therapy and Vitamin D therapy) are not particularly normatively challenging and hence are relatively uncontroversial, some ethical issues remain. Both interventions attempt to improve the baseline low quality of life (QoL) of seasonally depressed patients and their main issues concern the benefit-harm ratio and the question of social inequality. Regarding vitamin D therapy, although safety concerns are minor, there is insufficient evidence concerning its benefits. Regarding light therapy, the clinical benefits shown by the meta-analysis (Reference Nussbaumer-Streit, Titscher, Kaminski-Hartenthaler, Strohmaier, Stanak and Zechmeister-Koss13) need to be put in contrast with the potential side effects such as irritability, headaches, eye strain, sleep disturbances, and insomnia (Reference Terman and Terman11). Light therapy was also judged to be time-consuming by patients as it requires a commitment both in the morning and in the evening that is hard to be incorporated into daily routines and thus has the potential to disturb one's personal life (Reference Nussbaumer-Streit, Pjrek, Kien, Gartlehner, Bartova and Friedrich15). The issue related to social inequality is driven by the lack of insurance coverage and hence the need of out-of-pocket expenses. This is of particular relevance in case of purchasing the light therapy lamp that costs approximately 300 EUROS where patients also state that they get little guidance in the process of choosing the right lamp (Reference Nussbaumer-Streit, Pjrek, Kien, Gartlehner, Bartova and Friedrich15). Furthermore, the fact that, for instance, pharmacological therapy is covered by health insurance may have the potential to “nudge” SAD patients toward using pharmacological therapy instead of the less invasive options (such as light or vitamin D therapy), even though SAD patients tend to show preference toward nondrug therapies (Reference Nussbaumer-Streit, Pjrek, Kien, Gartlehner, Bartova and Friedrich15).

Benefit-Harm Ratio of the Comparators

Concerning the comparator interventions, the ethical issues with respect to second-generation antidepressants (SGAs) stem from their unclear clinical benefit profile and the risk of adverse events. The Cochrane systematic review of fluoxetine concludes a nonsignificant effect in favor of fluoxetine when compared to placebo and an equivalent effect when compared to light therapy (against the backdrop of low-quality evidence) (Reference Thaler, Delivuk, Chapman, Gaynes, Kaminski and Gartlehner36). In contrast, the potential side effects of fluoxetine are many and they include drowsiness, dizziness, weakness, runny nose, sore throat, headache, flu symptoms, nausea, diarrhea, changes in appetite, weight changes, decreased sex drive, impotence, difficulty having an orgasm, dry mouth, and increased sweating (Reference Thaler, Delivuk, Chapman, Gaynes, Kaminski and Gartlehner36). The insufficient clinical benefit profile of fluoxetine compared to the list of side effects seems to suggest a negative befit-harm ratio. With respect to the comparator of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), although there seem to be positive effects of CBT on SAD patients—especially when CBT is modified with respect to patients’ beliefs and values drawn from their spiritual narratives—the time-consuming nature of person-centered therapy serves as an obstacle that may prevent patients from seeking this treatment alternative (Reference Nussbaumer-Streit, Pjrek, Kien, Gartlehner, Bartova and Friedrich15;Reference Hodge and Bonifas32).

Ethical Issues Concerning the Assessment Process

Potential ethical issues with regard to the full HTA (Reference Nussbaumer-Streit, Titscher, Kaminski-Hartenthaler, Strohmaier, Stanak and Zechmeister-Koss13) are related to the choice of comparators and the health economic analyses. Relevant comparators that were not assessed in the full HTA are antidepressants other than SGAs, diet change, and lifestyle change. As these comparators were excluded from the analysis, a potential selection bias may be in place and relevant studies missed. This is of ethical relevance because gaps in the evidence base may change the conclusion of the HTA and hence the coverage decision. What is also ethically relevant are methodological mistakes in health economic studies, which may “incorrectly” deem an intervention cost ineffective and thus have a negative impact on patients. The main methodological concerns related to the health economic studies are that both health economic studies included come from the US context, and in the analysis, both included the healthcare provider view, whereas the patient view was included to a limited extent in one analysis, as it had a reduced patient perspective in terms of provider costs, travel costs, and income loss (Reference Ross48;Reference Freed49). No discount rates were used and reported in any of the studies and only inflation adjustments were made (Reference Ross48;Reference Freed49). In one of the studies, no reference values were used (Reference Ross48).

Discussion/Conclusion

In this article, we have analyzed the concrete ethical issues related to the interventions of light therapy and vitamin D therapy as well as those related to the assessment process and SAD as a disease. The ethical issues found concerned vulnerability of the target population and the imperative to treat depressive symptoms for the sake of preventing future harm. Further disease-related ethical issues concerned the questionable nature of SAD as a disease, autonomy, authenticity, and the capacity of SAD patients for decision making, and stigma related to underdiagnosis of SAD, which is contrasted with the concern over unnecessary medicalization that may redefine human conditions into medical ones. Moreover, only a limited number of ethical issues were found to be related to the interventions at stake—namely with respect to their benefit-harm ratios and the question of social inequality (due to the presence of out-of-pocket expenses). The benefit-harm ratio of the comparators was found to be of ethical relevance. Further ethically relevant issues were related to the assessment process, which concerned the choice of comparators and the input data for the selected health economic studies.

The main limitation of this ethics analysis lies in the methods used. First, it is questionable to what extent the PICO model applied to searching the medical databases can result in relevant hits, as PICO is an approach borrowed from especially clinical medicine and might thus not be fully suitable for searching and selecting ethically relevant literature. Secondly, the fact that only one person (MS) screened the abstracts without the quality check of the second person (CS) may cast doubts over the comprehensiveness of the literature included.

The present ethics analysis originally served as a chapter in a full HTA that assessed the safety and efficacy of the interventions at stake, as well as their economic, ethical, social, organizational, and legal implications (Reference Nussbaumer-Streit, Titscher, Kaminski-Hartenthaler, Strohmaier, Stanak and Zechmeister-Koss13). The concrete ethical issues that were found to be relevant to the interventions, the disease, and the assessment process were made overt in the present ethics analysis. The ethical issues outlined above are assumed to complement the medical-technical results of the clinical benefit assessment and so contribute to a broader assessment of value of the health technology. The ethics analysis yielded no ethical issues that would challenge the application of either of the two interventions. The IQWiG ThemenCheck is commended for conducting full HTAs that include the assessment of more issues than just those related to clinical benefit and safety. The value judgments embedded in the process of conducting an HTA need to be addressed in a transparent manner and ethics analyses can serve precisely this purpose.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462320000884.

Acknowledgments

We are most thankful to Tarquin Mittermayr for his support with the systematic literature search.

Financial Support

This work was funded by the Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen (IQWiG) and the Austrian Institute for Health Technology Assessment, Vienna, Austria.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.