Economic evaluation of hemodialysis: Implications for technology assessment in Greece

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 March 2005

Abstract

Objectives: Hemodialysis is a well-established treatment for 74 percent of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients in Greece. The purpose of this study is to provide an estimate of the direct cost of dialysis in a public hospital setting and an estimate of the loss of production for ESRD patients. The results will be useful for public health facility planning purposes.

Methods: A socioeconomic prevalence-based analysis was performed using micro-economic evaluation of health-care resources consumed to provide hemodialysis for ESRD patients in 2000. Lost productivity costs due to illness were estimated for the patient and family using the human capital approach and the friction method. Indirect morbidity costs due to absence from work and long-term were estimated, as well as mortality costs. Mean gross income was used for both patient and family.

Results: Total health-sector cost for hemodialysis in Greece exceeds €171 million, or €182 per session and €229 per inpatient day. There were 2,046 years lost due to mortality, and the potential productivity cost was estimated at €9.9 million, according to the human capital approach, and €303.000, according to the friction method. Total morbidity cost due to absence from work and early retirement was estimated at more than €273 million, according to the human capital approach, and €12.5, according to the friction method.

Conclusions: Providing hemodialysis care for 0.05 percent of the population suffering from ESRD absorbs approximately 2 percent of total health expenditure in Greece. In addition to the cost for the National Health System, production loss due to mortality and morbidity from the disease are also considerable. Promoting alternative technologies such as organ transplantation and home dialysis as well as improving hemodialysis efficiency through satellite units are strategies that may prove more cost-effective and psychologically advantageous for the patients.

- Type

- GENERAL ESSAYS

- Information

- International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care , Volume 21 , Issue 1 , January 2005 , pp. 40 - 46

- Copyright

- © 2005 Cambridge University Press

The rising cost and the efficiency of resource use has been a dominant health policy issue over the past 20 years (26). It has been established that health technology is a major cost-driver (12;36) but also that its appropriate utilization improves quality and effectiveness in health care delivery (24). Health technology assessment is a useful strategy for evaluating the need for the introduction of expensive technology, innovations, and alternative treatments.

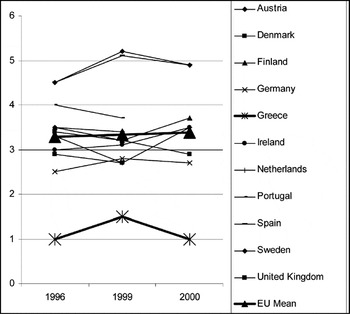

Among European Union (EU) countries, Greece shows one of the highest rates of hemodialysis stations for the treatment of end-stage renal disease (ESRD; Figure 1), and one of the lowest rates of kidney transplantation (Figure 2). Given the already proven effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the latter method (18;23), it is a matter of interest to evaluate the financial implications of a health policy that seems to favor the more costly alternative.

Hemodialysis stations per million population in some European countries. Source: OECD Health Database 2002. EU, European Union.

Number of kidney transplantation procedures per million population in European countries (1996, 1999, 2000). Source: OECD Health Database, 2002. EU, European Union.

Despite that ESRD affects only 0.05–0.07 percent of the population, its treatment consumes a considerable portion of national health resources (Table 1). Hemodialysis, as the most widely used approach to ESRD treatment, is characterized by high cost and major limitations, which are associated with the duration and frequency of treatment. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD), on the other hand, is characterized by a high incidence of complications (hospitalization rates among CAPD patients are higher than that for hemodialysis patients) (2), and kidney transplantation is a rather complicated and lengthy procedure. This finding may partly explain the steady growth in the numbers of patients treated with hemodialysis (30;31). In Greece, the total number of ESRD patients on in-center hemodialysis, on CAPD, and with a functioning kidney transplant rose between 1997 and 2001 from 6,942 to 8,889, three quarters of whom were patients on hemodialysis (9). It is also worth mentioning that 70 percent of ESRD patients are between the ages of 20 and 65, which is the productive age.

Hemodialysis sessions usually take place in a hospital setting (National Health System [NHS] or private) and, therefore, is expensive to deliver (8;16;23). Additionally there are other costs involved, as dialysis affects the ability of the patient to work. A recent study reported a drop in employment from 83 to 42 percent for in-center hemodialysis patients (6). This type of lost productivity, rarely included in economic analyses of ESRD, is shown in this study to have a substantial impact on the total cost-of-illness.

OBJECTIVES AND METHODS

This study provides a comprehensive estimate of the cost of hemodialysis treatment in Greece. The cost valuation includes a microlevel (11) estimate of direct hospital cost, as well as the productivity losses associated with the condition and its treatment with hemodialysis. It is based upon recent guidelines on economic evaluation methodology and uses detailed data collected through a specially designed empirical study (3;17;22).

The study uses a prevalence-based approach to provide cost estimates from a societal perspective. Data for 1 entire year (2000) were collected at the Georgios Gennimatas General NHS hospital in Athens, which includes a nine-station dialysis unit, performing approximately 7,000 hemodialysis sessions per year. The unit operates 6 days a week for 14 hours/day. Data on lost productivity and costs to the patient and family where collected from a countrywide sample of 128 patients. Mean gross income from national accounts was used to compute lost production due to absence from work. All data are expressed in 2000 Euro (€) prices.

All direct health-care sector costs such as medical supplies, drugs, laboratory tests, salaries and wages, and overhead expenses (11), including equipment and plant depreciation, were included. Dialysis membranes (mainly hemophane, polyacrylonitrile, cellulose acetate, and high flux in a small percentage of patients) are disposable by law, and all patients are treated with bicarbonate dialysate. Water is deionized in a central water preparation system using reverse osmosis. We included average cost for concomitant drugs used, including recombinant human erythropoietin, administered to 87.5 percent of patients, and routine laboratory testing for 1 year. Personnel costs were estimated using the time spent performing various activities.

Because various hospital departments (administration, laundry, housekeeping, technical, porterage, etc.) provide services, directly or indirectly, to hemodialysis patients and to the unit staff, a microcosting model was developed to allocate such costs to the dialysis unit (11;34). The cost of electricity was estimated using an engineering model based on the number of kilowatts needed and the functioning hours of the equipment involved in treatment (33). Depreciation expenses for dialysis units and the reverse osmosis machine were estimated according to patient utilization levels for a specified period by using the fixed balance method. Amortization was assumed at 5 years for dialysis units and 7 years for the water preparation system (1).

Hemodialysis patients are often hospitalized for the treatment of complications. Because fixed charges set by the Ministry of Health for reimbursement purposes do not depict accurately real resource consumption, we calculated cost per inpatient day in the nephrology ward through direct cost analysis and used the result to calculate the total cost associated with hemodialysis.

In addition to direct medical costs, lost productivity for the patient and family (often referred to as indirect costs) have a substantial impact on the total cost-of-illness. According to the Canadian guidelines, this type of costs is the value of production lost as a result of the illness or the treatment process (3). In the case of in-center hemodialysis, where lost time and/or employment are major cost components, including these costs is essential. An effort was made to estimate mortality and morbidity costs due to absence from work, long-term disability leading to a change in type of work, or premature retirement. These estimations were attempted using both the Human Capital Approach and the Friction Cost Method.

The human capital approach measures the present value of all future production foregone and is the method most commonly used for the estimation of indirect costs. It may, however, overestimate real production losses for society, because nonurgent work lost by short-time absenteeism may be postponed or taken over by the patient's colleagues (10;14;19;20;35), and in long-term absenteeism, work can be taken over by an unemployed person. Therefore, production losses were estimated by the friction period, which is the period needed to replace a sick worker. Because there are no available Greek data for the average friction period, the average period that an employee is compensated for by Social Security after being dismissed from his job was used. Additionally, the length of the friction period used was confirmed by data from a sample of companies regarding the replacement and training of new employees.

Mortality in terms of the number of potential years of life lost in 2000 was estimated by taking the difference between the mid-point of each 5-year age band in which a death due to ESRD occurred and the estimated years of life expectancy at the time of death. The number of deaths that took place within each age band was multiplied by this difference. However, it is not assumed that individuals dying from ESRD would otherwise have attained the average life expectancy. To estimate the number of individuals who would reach retirement age if they had not died, the number of deaths for each age band was multiplied by the probability of survival (px), calculated as px=1−qx, where qx is the probability of death for each age band, according to Greek life tables.

The mortality cost of ESRD patients on dialysis was estimated by multiplying average annual earnings at year 2000 for both men and women by the average economic activity rate for the relevant age group and then by the average employment rate and the number of working years left, to estimate the earnings that an individual who died in 2000 would have received from paid employment. This value was discounted at a 3 percent discounting rate and multiplied by the number of deaths in each age group to estimate the total productivity loss due to mortality caused by ESRD in 2000 (11). Morbidity also causes production losses due to premature retirement, absence from work and reduced productivity during work. Information on these factors for the patient and the patient's family was collected through a questionnaire filled during the hemodialysis session, indicating age, sex, profession, number of hours worked per week, type of work, and so on. It should be noted, that only the career's actual working time lost was taken into consideration. Mean gross hourly wage was used to calculate lost output. The analysis concentrated on people who had a paying job during the last month before the study. To calculate the loss of production by the friction method, respondents were asked to indicate any compensating mechanisms at work (e.g., compensation by colleagues).

Loss due to morbidity was then estimated by multiplying the number of days or hours out of work, because of sickness and invalidity caused by the disease or the specific treatment, with the mean gross income in 2000 in Greece. To calculate daily earnings, annual gross income was divided by 250, assuming that people worked 5 days per week and 50 weeks per year.

Production loss due to premature retirement of patients with ESRD was estimated with the methodology used for the production loss due to mortality. The years of production lost were estimated by calculating the difference between actual retirement age and age of death. Finally, to calculate reduced productivity during work, patient estimates of the number of days worked with ESRD symptoms in the previous month were used (7;27).

RESULTS

Health-care sector costs associated with each hemodialysis session where estimated at €189/session. Major expenses are medical supplies and drugs (53 percent) with hemodialysis membranes as the major cost-driver. Staff remuneration represents 31 percent of health-sector cost, and overhead expenses account for 6 percent. These data are consistent with other evaluations of health-sector cost for ESRD (8;15;29).

Of the 128 ESRD patients who underwent hemodialysis, 46.1 percent were hospitalized for 8.5 days/year (95 percent confidence interval [CI], 3.2–13.7 percent; SD, 8.3). After detailed cost analysis, the cost per inpatient day in the nephrology ward was estimated at €229.5. The total average direct in-patient cost per patient per year is estimated at €29,470, and extrapolation to the total number of hemodialysis patients in Greece in the year 2000 gives an estimate of €171.8 million spent in the treatment of ESRD patients with hemodialysis.

Lost Earnings from Premature Mortality

In 2000, 706 patients on hemodialysis died in Greece leading to a loss of 2.034 potential productive years of life lost. Lost earnings, after taking into account the economic activity and unemployment rate for Greece in the year 2000, were estimated at €9.9 million (3 percent discount rate). When the friction method was used for the estimation of mortality cost, the amount was only €302,513, because it was assumed that costs should only be measured for a friction period of 0.27 years.

Production Losses Due to Morbidity

Of 200 patients observed, 128 (64 percent) agreed to fill out a questionnaire on the effects of morbidity. The majority of the respondents were men (57.8 percent), and the average age was 56.1 years (95 percent CI, 52.2–59.9 percent; SD, 16.7) for men and 51.7 years (95 percent CI, 47.6– 55.9 percent; SD, 15.4) for women. Of the 128 respondents, 33 had a paying job at the time of the study, 64 were retired (47 prematurely) due to ESRD, and 31 were unemployed or students.

As mentioned above, 36.7 percent of the patients retire before normal retirement age.1

The official retirement ages in Greece is 65 years for men and 60 for women.

Of the patients who had a paying job, 63.6 percent reported absence from work of 19.9 hours/week (95 percent CI, 15.7–24.1 percent; SD, 7.5) and lost earnings were estimated at €5,090 per patient per year. At the national level, for the year 2000 a loss of €4.9 million is attributed to absence from work. However, when taking compensating mechanisms into account, estimated earnings lost are reduced to €4.3 million, because 43.5 percent of the patients with a paid job, reported either that they were not absent from work or that their work was compensated by colleagues during normal working hours. Loss of production for these cases was considered to be zero.

Among the patients with a PAYING job, 39.4 percent reported on average that 4.8 days/month were working with ESRD symptoms and they also reported that they were on average 62.2 percent effective (range from 0 to 100 percent), resulting to a loss of earnings of €496,877. Another 43.3 percent (n=55) of patients was accompanied to the hospital by a family member. Of the family members, 50.9 percent had a paying job and reported a loss of 2.4 hours (95 percent CI, 1.9–2.9 percent; SD, 1.3) per hemodialysis treatment (three times per week) from work, because they provided this support, resulting to a loss of €1,842 per accompanying member per year (€2.1 million for Greece).

In summary, the overall production loss from ESRD in patients undergoing hemodialysis and for their families was estimated at €273.1 million. The total amount is much lower (€12.5 million) when the friction method is used, because compensating mechanisms are taken into account.

DISCUSSION

In 2000, the direct cost of dialysis in Greece accounted for 2 percent of national health expenditure, almost twice the expenditure attributed to RRT in other countries (Table 1). This should attract the attention of funding agencies and kidney disease specialists and underlines the importance of health technology assessment, a scientific field that has not yet received the appropriate attention in Greece (21). This study provides information for policy priorities formulation and reimbursement purposes. It can also be used to identify cost driving factors and to inform decisions for curtailing costs. Finally, as a precise costing exercise, it can be used by providers for claiming reimbursement and for policy-makers to decide reimbursement rates in relation to other diseases.

In addition to the costs imposed on the NHS, ESRD imposes significant costs on society in terms of production losses due to treatment requirements, morbidity, mortality, and time spent to care for patients. It was estimated that production losses due to mortality from the disease are €10 million and production losses due to premature retirement and morbidity are €270.6 million. Additionally, the cost of informal care is up to €2.5 million. On the other hand, if compensating mechanisms are taken into account, estimates of productivity losses are significantly lower but still considerable.

Undoubtedly, dialysis is very expensive, but it is also a life-saving treatment for 6,700 people in Greece. There is clearly room for efficiency improvement with the use of satellite hemodialysis units, a dialysis mode that may prove cost-effective and psychologically advantageous for patients (28). For example, of the 2,272 units providing dialysis services in the United States, 1,646 were free-standing and only 626 were hospital-based (13). Changing the staff skill mix may also reduce costs, because a major part of the cost is salaries and wages. Renal nurses, for example, with a higher level of education, could substitute for expensive medical staff.

Kidney transplantation offers considerable lifetime savings and a drastic improvement of patient quality of life and, according to the literature, is the most cost-effective treatment for ESRD (18;23;32). The low transplantation rate in Greece is due largely to a shortage of organ donors because of complex cultural and societal factors. A campaign directed to the general population and medical professionals could prove effective. A major attempt should also be made to coordinate activities in intensive care units and transplant units. This strategy requires a special effort to provide hospital personnel with managerial and communication skills for the identification of potential donors and the approach of grieving families. Such efforts led to the increase of donors in Spain from 14.3 per million population in 1989 to 26.8 in 1996. Finally, there is evidence that telemedicine could provide safe and effective out-of-hospital hemodialysis accompanied by significant savings from reduced utilization of medical and administrative personnel. A study (25) has demonstrated the feasibility of linking an out-of-hospital facility or the patient's home to a hospital supporting control center, thus enabling acute intervention by the specialists. The supervision of each hemodialysis session with bidirectional communication links and the adoption of high security levels as well as the transferability and interoperability of these services to an actual hospital environment could offer a great deal of benefits (4). As the present analysis demonstrated, ESRD and hemodialysis represent a major burden on the NHS, and adoption of some of the above recommendations could lead to substantial savings at a national level.

CONTACT INFORMATION

Daphne Kaitelidou, MSc, PhD, Senior Research Associate (dkaitel@cc.uoa.gr), Department of Nursing, Center for Health Services Management and Evaluation, University of Athens, 123 Papadiamantopoulou Street, 11527 Athens, Greece

Panagiotis N. Ziroyanis, MD, PhD, Chief, Department of Nephrology, G. Gennimatas Hospital, 154 Mesogeion Avenue, 11527 Athens, Greece

Nikolaos Maniadakis, PhD, Manager–CEO (nmaniadakis@med.upatras.gr), University Hospital of Rio, 26504 Rio Patra, Greece

Lycurgus L. Liaropoulos, PhD, Professor (lliaropo@cc.uoa.gr), Department of Nursing, Center for Health Services Management and Evaluation, University of Athens, 123 Papadiamantopoulou Street, 11527 Athens, Greece

References

- 28

- Cited by