Introduction

Given its influential role in prioritizing access to safe and effective health technologies and interventions, health technology assessment (HTA) also has the potential to influence inequities in health. Along with growing recognition of the need to explicitly consider the impact of health decisions on health equity (1), there is impetus to undertake equity analyses within HTAs. However, a number of surveys have found that the inclusion of equity considerations and analyses in HTA remains infrequent (Reference Bellemare, Dagenais, Suzanne, Béland, Bernier and Daniel2;3). Different reasons might explain this; including a lack of relevant methodological knowledge and training as well as greater time and human resource requirements and sparse primary data. HTA practitioners aspiring to assess inequities and provide recommendations to decrease them might, therefore, benefit from guidance on how to do so. This article describes the development of a checklist that aims to bridge this gap: the equity checklist for HTA (ECHTA).

Defining Health Inequity

A widely used definition of health inequity has been proposed by Whitehead (1992) and built upon by the WHO's Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) (Reference Marmot, Friel, Bell, Houweling and Taylor4;5). It posits that health inequities are not merely differences in health status (termed “inequalities”) but differences between groups that are unnecessary, avoidable, unfair, and unjust (Reference Whitehead6). The criteria of fairness and justice can be understood as systematic differences considered avoidable (5). Thus, all should have a “fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible” (Reference Braveman, Arkin, Orleans, Proctor and Plough7). The use of this definition, in turn, assumes that equity considerations in the context of HTA imply a normative analysis because value judgments are applied to enable actions through recommendations, beyond the simple description of the current state of affairs. Nonetheless, the operationalization of this definition first requires an understanding of the terminology used to refer to the individuals suffering from these inequities. Different terms have been proposed and used by different individuals and groups to refer to themselves. These include marginalized, disadvantaged, individuals living in positions of vulnerability, among many others. These terms have different implications and the authors recognize the agency of individuals in choosing the term that most empowers them (Reference Friedman8). For the purposes of this paper, the term “disadvantaged” will be used, simply to denote that a health inequity represents a disadvantage in health status that is unfair. The authors hope, however, that these groups will recognize themselves in these writings.

Operationalizing the definition of health equity also calls for an understanding of the factors modulating health, including health inequities. The authors adopt the CSDH's perspective and, therefore, recognize that several aspects influence the health impacts of a technology or intervention beyond its efficacy and safety. Notably, economic, organizational, sociodemographic, and other contextual elements modulate the differential effects of a technology or intervention (5;Reference Braveman, Arkin, Orleans, Proctor and Plough7;Reference Friedman8). Different mnemonic aids and tools have also been developed to guide the recognition of potentially disadvantaged groups. For instance, the acronym PROGRESS Plus has been proposed to emphasize that inequities in health are not only due to poverty (i.e., the rich–poor gap) but also due to other critically important factors, such as place of residence, race/ethnicity/culture/language, occupation, gender/sex, religion, education, socioeconomic status, social capital; in addition, the “Plus” refers to any other relevant characteristic such as age, sexual orientation, or disability (Reference Welch, Petkovic, Jull, Hartling, Klassen and Pardo9). This provides categories through which disparities in health and its social determinants can be qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed. Groups and individuals can, however, belong to more than one of these defined categories, that is, they can find themselves at the intersection of various categories of population groups (Reference Hopkins10). For instance, an individual might be an immigrant transgender woman living in a rural area. Intersectionality refers to the unique interplay between different axes, which results in distinct societal power relations and not simply in the sum of the categorical axes to which individuals relate (Reference Hopkins10).

Applying Health Inequity Concepts to HTA

Such approaches remain, however, rather descriptive for the purposes of undertaking HTA. To address this gap, theoretical guidance has been increasingly provided. One such example is the Equity Framework for HTA suggested by Culyer and Bombard (Reference Culyer and Bombard11). This framework is aimed at impacting both the procedures of the HTA endeavor and the final conclusions and recommendations resulting from the HTA. It consists of thirteen guiding elements to consider during the HTA process (Reference Culyer and Bombard11). Another example is the GPS-Health tool, which provides a concise list of criteria for guiding healthcare priority setting in addition to cost-effectiveness evaluation (Reference Norheim, Baltussen, Johri, Chisholm, Nord and Brock12). These tools, however, are not pragmatic because they are not organized in a manner that allows practitioners to follow along each step of an HTA. The challenge, therefore, lies in utilizing tools that can analyze inequities in health and its determinants in each phase. A number of references provide explicit methods or tools to guide the choice of HTA evaluators (Reference Cookson, Griffin, Norheim and Culyer13–15).

The tool presented here does not seek to address the specific methodological approaches to be utilized. Rather, it seeks to provide general points of reflection to guide HTA practitioners and researchers in their consideration of health equity. Thus, this paper's objective is to propose a checklist that builds on previous work in the field and present the initial face and content validation of the work undertaken. Given that the tool is based on an array of international tools and frameworks and that it remains generic in its approach, our aim is that it can be useful to all HTA practitioners and researchers wishing to include equity considerations throughout their undertaking of an assessment.

Methods

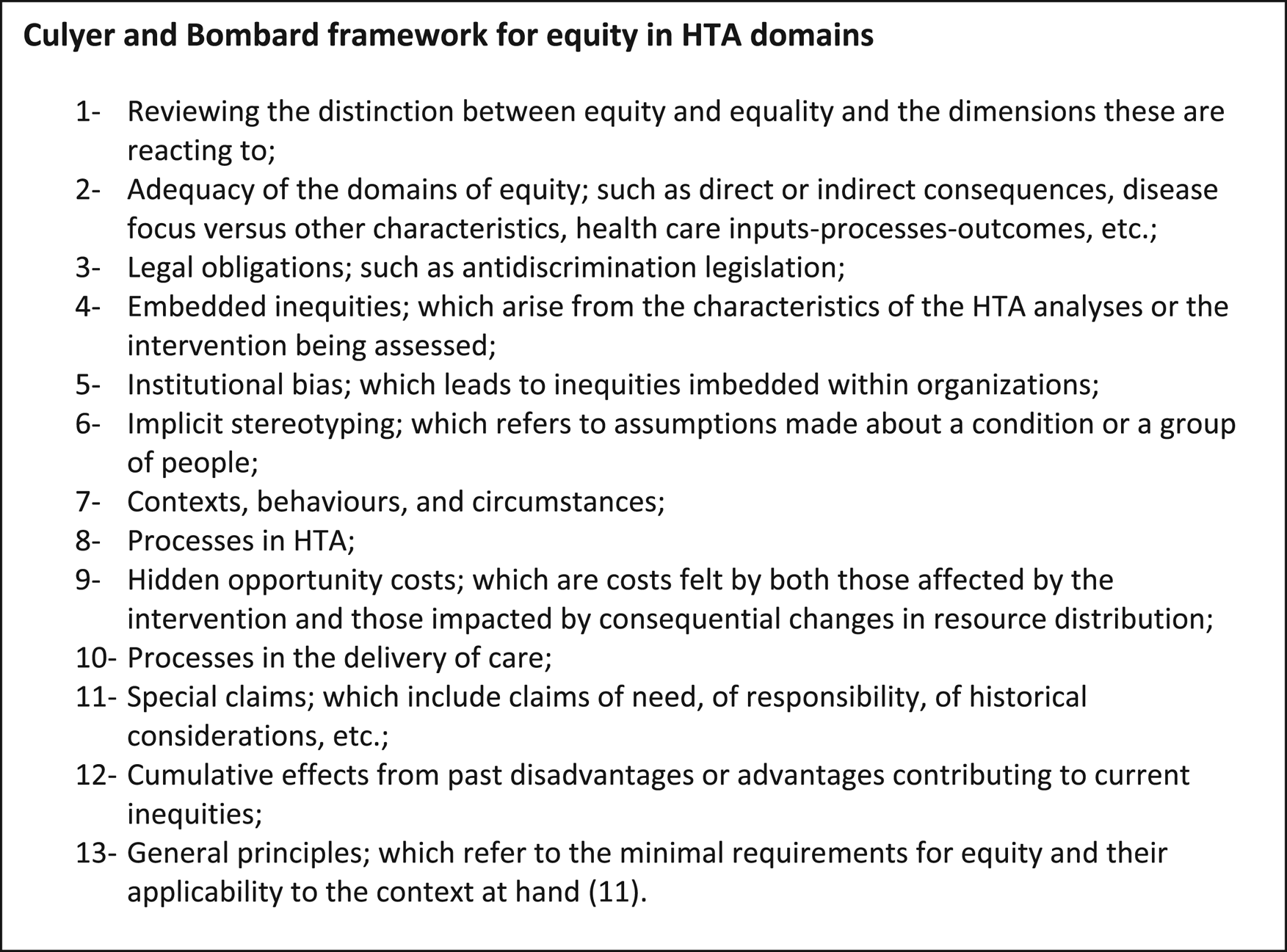

A first set of items was defined based on the thirteen domains outlined by Culyer and Bombard (Reference Culyer and Bombard11) in their framework for equity in HTA. These domains are enumerated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Culyer and Bombard framework for equity in HTA domains.

These domains, and the concepts they contain, were rephrased to render them more pragmatic. To increase user-friendliness, they were then organized into the HTA steps inspired by the HTA Iterative Loop suggested by Bennett and Tugwell (Reference Bennett and Tugwell16) as well as the equity health impact assessment literature (Reference Mahoney, Simpson, Harris, Aldrich and Williams17). This perspective views HTA as an iterative cycle that goes beyond evaluating and providing recommendations. Indeed, it evolves from scoping through to evaluation, recommendation and conclusion, knowledge translation and implementation, and lastly reassessment.

A nonsystematic literature search was undertaken to complement the initial list with additional elements and considerations. Methodological guidance tools and documents relating to the inclusion of equity in HTA were searched. First, generic searches on Google and Google Scholar using a combination of synonyms for the concepts of HTA and equity were undertaken. Second, the Web sites of the following organizations were also targeted: HTA International (including the Web sites of their Ethics interest group and their Patients and Citizen Involvement interest group), the International Network of Agencies for HTA (INAHTA), Quebec's National Institute of Excellence in Health and Social Services (INESSS), the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Cochrane Collaboration. Select elements were, therefore, included from seven additional studies and guidelines (Reference Welch, Petkovic, Jull, Hartling, Klassen and Pardo9;Reference Espinoza and Cabieses18–23).

Feedback was sought from experts on equity in HTA through e-mail and telephone correspondence. The list of experts was expanded through snowball referencing, for a total of ten experts. The experts represented a wide variety of perspectives emanating from different contexts, including academia in high-income and low- and middle-income countries, governmental agencies, as well as HTA practitioners at national and regional levels. These experts appear as authors on this paper or are acknowledged, depending on their degree of participation and willingness to participate as authors of the work. The feedback received was compiled and analyzed through a content thematic analysis. Themes and codes were created using a general inductive analysis approach (Reference Thomas24). Themes first depended on whether they pertained to the tool itself or its description within this paper. Those themes pertaining to the tool were further categorized according to the relevant section of the tool. There were no contradictions or incoherence in the comments provided. This allowed for the validation of the checklist items as well as their organization and presentation. The tool was also presented at an international conference on HTA in 2019, and the additional feedback received verbally was incorporated into the checklist (Reference Benkhalti and Dagenais25).

As the goal was to develop a guidance checklist, rather than an evaluation tool, external validity and inter-rater reliability were not tested. A pilot test was undertaken with an HTA project on corticosteroid injections and other treatments for chronic low back pain in the context of a regional health network in Quebec (Reference Benkhalti, Dagenais, Poder and Carroll26). The project manager was the first author on this paper (MB) and the supervisor was another coauthor (PD). The project also involved an advisory committee made up of a wide range of stakeholders, including healthcare professionals, managers, and users and parents of children users. This committee was involved in all phases of the HTA. It was informed and invited to further comment and discuss on the analyses, propose changes, and provide data that might answer those equity-related questions. The elements of the checklist were consulted in each separate phase of the HTA project. Adjustments were made when the analysis of a checklist element brought up concerns that had previously not been considered. As a result, the checklist was subsequently further revised so as to facilitate its use.

Results

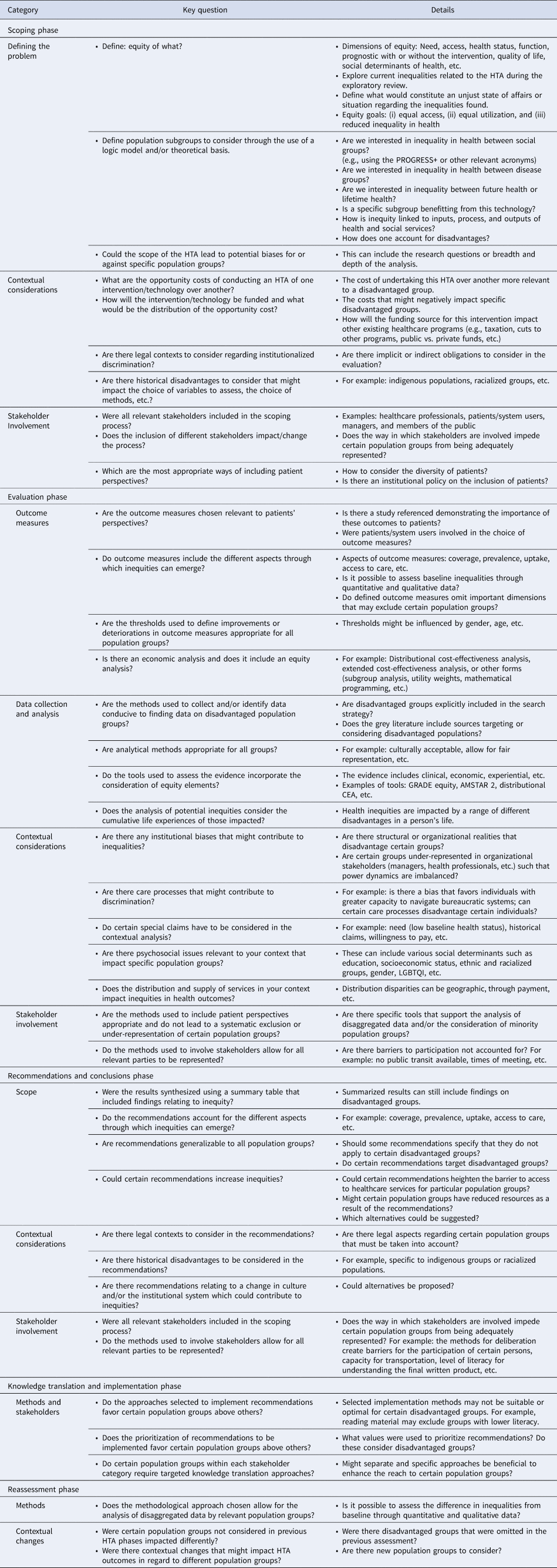

The result was a five-phase checklist, containing explanations and examples, aimed at HTA evaluators to facilitate the consideration of various domains of health equity within the evaluation process: the equity checklist for health technology assessment (ECHTA). Once a decision has been made to appraise a particular technology or intervention, ECHTA can accompany evaluators through all five phases of an HTA. They include the initial negotiations with decision makers requesting the evaluation and defining the scope of the HTA, through to the evaluation, and the development of recommendations, and lastly, knowledge translation and implementation strategies that consider disadvantaged population groups as well as understanding the need to reassess the technology or intervention. Although all five phases may not take place in every HTA, evaluators may refer to the items in the phases relevant to their particular project. It is important to note that the checklist is not meant to be completed in one sitting. Rather, it can be consulted at the start of each phase and in an iterative manner throughout the completion of the work.

The first phase, Scoping Phase, brings questions relative to defining, identifying, and contextualizing equity, such as identifying potential disadvantaged groups and including vulnerability factors in a logic model or in other theoretical frameworks. Second, the Evaluation Phase facilitates the adoption of methodological approaches that are conducive to analyzing inequities as well as considering contextual realities that have an impact on inequities. Its elements are subdivided into four categories: outcome measures, data collection and analysis, contextual considerations, and stakeholder involvement. Third, the Recommendations and Conclusions Phase addresses evidence synthesis approaches, the contextual factors to consider, as well as the generalizability versus specificity of recommendations to particular population groups. This aims at ensuring that the drafted recommendations consider existing inequities. It is also imperative that they avoid contributing to greater inequities. The elements of this phase are categorized according to scope, contextual considerations, and stakeholder involvement. Fourth, the Knowledge Translation and Implementation Phase prompts evaluators to consider whether the chosen implementation methods favor certain population groups as well as whether there might be a benefit to targeted knowledge translation approaches. Lastly, the fifth Reassessment Phase questions the methodological approaches as well as any changes in context that might have occurred since the initial evaluation. The full ECHTA tool is found in Table 1.

Table 1. Equity checklist for HTA (ECHTA)

HTA, health technology assessment; ECHTA, equity checklist for health technology assessment.

Using ECHTA

As previously mentioned, ECHTA could be used by any researchers or evaluators wishing to consider health inequities in their HTA. The checklist acts as a prompt for the various elements to consider during the undertaking of an HTA. It is not meant to be completed in one sitting, but rather to be consulted at the beginning of each step. Indeed, although the list may seem long and time-consuming, it could be regarded as five interconnected lists. Certain elements may not be relevant to the HTA at hand and, therefore, may be omitted. Their relevance, however, can be determined only upon adequate consideration. The authors nevertheless recommend that evaluators become familiar with the entirety of the checklist upon first use. The use of ECHTA may certainly be easier for evaluators with prior knowledge of ethics and equity evaluations. The checklist remains nonetheless aimed at all HTA evaluators with the hope that it will increase knowledge of these issues.

Stakeholder Involvement

A stakeholder can be defined as any “individual with an interest in the outcome of the HTA process final decision” (Reference Street, Stafinski, Lopes and Menon27). They may include healthcare professionals, health system payers, managers and other employees, patients, users, and carers. The level of involvement that stakeholders can have within an HTA may vary according to the length and depth of the assessment or according to the perceived purpose of stakeholders that HTA evaluators may have. Stakeholders may be included only as a source of data or on a sporadic basis throughout the project or they may be involved throughout the entire process. Stakeholders may also be formally included in the process via participation in an advisory committee, which has a say in every phase of the HTA, including the coconstruction of final recommendations and conclusions (Reference Street, Stafinski, Lopes and Menon27). While adopting an equity lens, the advisory committee should be cognizant of representing a diversity of relevant population groups. Indeed, it is important to note that the involvement of stakeholders does not inherently result in an understanding of health inequity concerns. Rather, it is advisable to ensure that the stakeholders, including patients and citizens, involved represent various population groups, notably disadvantaged groups. A limitation of stakeholder involvement in HTA relates to the overrepresentation of certain interests and views to the detriment of other relevant social elements. This drawback is not specific to equity analyses but could be relevant to any social value judgment. This concern can be mitigated by a transparent and accountable process including the disclosure of conflicts of interests of all stakeholders included.

Pilot Test

To assess the usability of the checklist, a pilot test was undertaken through a comprehensive HTA on corticosteroid injections and other treatments for chronic low back pain. The HTA aimed at answering the needs of a regional health network in the province of Quebec, Canada. As such, the HTA assessed the safety and efficacy of corticosteroid injections, guidelines for the other treatments, as well as organizational considerations for the optimal use of recommended treatments. The use of ECHTA rendered explicit the consideration of various factors modulating equity, beyond the differential efficacy of at-risk groups. For instance, it prompted the definition of what constitutes inequities in the context of the region and consequently enabled the team to engage with the appropriate stakeholders to further understand these realities. During the evaluation phase, ECHTA pushed the evaluators to consider inequity in the choice of outcome measures and to seek contextual data that also considered minority groups in the population. These considerations resulted in recommendations that explicitly took into account the potential realities of these groups. Table 2 presents examples of these recommendations, which are contrasted with possible outcomes had ECHTA not been used. These possible outcomes are inferred from the conclusions usually obtained in previous HTAs undertaken by our unit that did not undertake an equity analysis.

Table 2. Examples of impacts on recommendations through the use of ECHTA

ECHTA has yet to be used in the fourth Knowledge Translation and Implementation phase or the fifth Reassessment Phase of an HTA. This, combined with the fact that these phases are seldom described in HTA reports, has meant that a relatively small number of equity elements of consideration are currently listed under these phases. It is the hope of the authors that these phases will be further populated as the tool is utilized and feedback is provided from the HTA community.

Discussion

This paper presents a first iteration of ECHTA, a checklist to guide the consideration of equity during the undertaking of an HTA, and the results of its first application. This checklist does not claim to answer all barriers impeding the greater prevalence of equity analyses in HTA. Rather, it is aimed at practitioners already considering including an equity analysis in their work. It is meant as a starting point to reflect on the factors potentially impacting inequities and the means to consider them throughout an HTA. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first pragmatic checklist that can be used as a reference throughout all the phases of an HTA. It does, however, base itself on the rich pre-existing work in the field (Reference Culyer and Bombard11;Reference Bennett and Tugwell16;Reference Espinoza and Cabieses18;Reference Panteli, Kreis and Busse21).

The tool is meant for all HTA evaluators, regardless of their expertise in health equity analysis, although evaluators with less experience doing equity or ethics analyses might encounter a greater learning curve and might require consulting additional references. It is our hope that ECHTA will act as a facilitator to their learning. Furthermore, the use of ECHTA certainly generates the need for greater resources. For instance, the process of collecting and analyzing disaggregated data, which adequately represent various minority groups, can be more difficult and lengthy. Additionally, discussions with stakeholders and committees may be longer given the greater data, and sometimes controversial, nature of recommendations that require further analyses of the healthcare system's value judgments. The precise amount of additional resources required is largely dependent on the project, its research questions, and the context within which an analysis is made. Nevertheless, much like other methodological developments in HTA, we view equity analyses in HTA as strengthening the decision-making process and contributing to its legitimacy. A first pilot has demonstrated its usability and added value. It has shown that the use of ECHTA can aid in the consideration of the impact on different population groups and result in recommendations that take these groups into account. Thus, these recommendations can have concrete impacts on these population groups and ensure that the results of the HTA do not exacerbate inequities and, ideally, contribute to diminishing them.

The subsequent use of ECHTA in various types of HTAs will further strengthen the checklist through future revisions, notably through additional elements in the fourth Knowledge Translation and Implementation phase and the fifth Reassessment phase. Indeed, these latter phases are often influenced by a greater number of factors and actors that go beyond the core HTA evaluation team and might, therefore, require more nuanced considerations. Similarly, the prioritization of the HTAs to be undertaken may involve various actors beyond the evaluation team, and the selection criteria might not always include health inequities. Such processes can subsequently lead to a systematic omission of the needs of minority groups. This important element is currently missing from ECHTA. HTA evaluators should remain cognizant of such prioritization criteria and be reflexive and explicit of them in their identification of opportunity costs in the scoping phase. Although the inclusion of knowledge translation experts, decision makers, and healthcare users representing those disadvantaged groups throughout the entire HTA process can help remedy this situation, it is important to acknowledge that the responsibility frequently lies beyond that of the HTA evaluation team. Nevertheless, the authors aspire to provide more detailed guidance on this concern in future work.

Other developments for ECHTA might include more specific guidance on addressing intersectionality considerations as well as a shorter version of the checklist that identifies those considerations that are usually of importance for policy makers or for which there is often evidence. An international group of experts has formed a workgroup to further the development of the tool in order to address these points and others that might arise. The current iteration is ready to be used and the authors welcome any constructive feedback resulting from its use in other HTAs. Among other things, the checklist would benefit from use in HTAs in different settings, including resource-poor settings and examples outside of North America. The authors realize that a number of terms and concepts introduced in ECHTA are specific to the health equity literature and might benefit from further explanation.

The length of ECHTA might lead one to think that its main use would be for comprehensive HTAs. These HTAs, having longer timelines and greater resources, would have a greater capacity for additional analyses. Evaluators are nevertheless invited to use ECHTA for all their evaluations. Indeed, recommendations and conclusions emanating from rapid HTAs have the same potential of differentially impacting minority groups as more comprehensive evaluations. Several strategies could be adopted when using ECHTA for shorter HTAs. For instance, checklist items could be considered but analyzed in lesser depth. In addition, certain inequities emerging during the first Scoping Phase could be prioritized according to their severity or the capacity to address them given limited resources. Such normative value judgments should be undertaken in consultation with decision makers and stakeholders. Additionally, the limitations of these simplified analyses must be addressed. These could give rise to specific guidance for rapid HTAs.

Despite these shortcomings, ECHTA aims to facilitate the consideration of health inequity during the HTA process and presents a pragmatic approach to achieve this. The authors hope that the usefulness of ECHTA will be recognized and improved as is it used and that HTA evaluators can look to these working examples for inspiration. We also hope that this work will catalyze further engagement and discussion to better understand the barriers that have prevented equity analyses in HTA from being more prevalent.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following people for providing us with substantial comments that contributed to the development of the checklist: Reiner Banken, Ken Bond, and Tara Schuller.

We would like to thank the following people for providing us with feedback on the checklist: Marie-Natacha Marquet, Marie-Belle Poirier, and Janet Hatcher-Roberts.

Funding

We would like to thank the HTA unit (UETMISSS) from the regional health network Centre intégré univeritaire de santé et de services sociaux de l'Estrie – Centre universitaire de Sherbrooke (CIUSSS de l'Estrie – CHUS) to have funded the development of this tool from its operational budget.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Cookson reports grants from Wellcome Trust during the conduct of the study. None of the other authors have any known conflict of interest to declare.