It has been 50 years since Arnstein published her seminal paper, “A ladder of citizen participation” (Reference Arnstein1). It aimed to distinguish between citizen control and empowerment and citizen consultation and levels of “tokenism.” Some 40 years later, Tritter and McCallum (Reference Tritter and McCallum2) published a critique of Arnstein's model, suggesting that her emphasis on power undermined the potential of involvement processes. Tritter and McCallum explored the involvement of users of health care in healthcare decision making, focusing on the aspects of effective involvement that Arnstein's model did not consider (Arnstein's “missing rungs” (Reference Tritter and McCallum2, p.161)).

From “citizens” to “users,” Tritter and McCallum's paper reflected a neoliberal shift in citizen involvement to that of “future service users” and “potential patients” (Reference Tritter and McCallum2, p.160). The shift emerged from the notion that markets could improve health service provision by “giving [patients] purchasing power—i.e. making them customers of primary care services” (emphasis in the original text) (Reference Fredriksson3, p.95). The term “user” employed by Tritter and McCallum (Reference Tritter and McCallum2) is consistent with “consumer,” the term preferred in Australian government circles.

The debate over terminology continued. Coulter suggested that it was “easy to stumble into semantic minefields when writing about patient engagement” (Reference Coulter4, p.8), and rejected the use of alternative terms to “patient.” However, in many countries, the term fell out of use in a context which saw service delivery as operating within a market. The term “citizen,” on the other hand, suggests a reciprocal arrangement with the state in which individuals have both rights and responsibilities. It also carries notions of nationality and may be seen to exclude noncitizen residents. While the term “citizen” includes patients, in recent years “public and patient” or simply “public” involvement has mostly engaged those presenting patient and/or carer perspectives. (Reference Fredriksson and Tritter5)

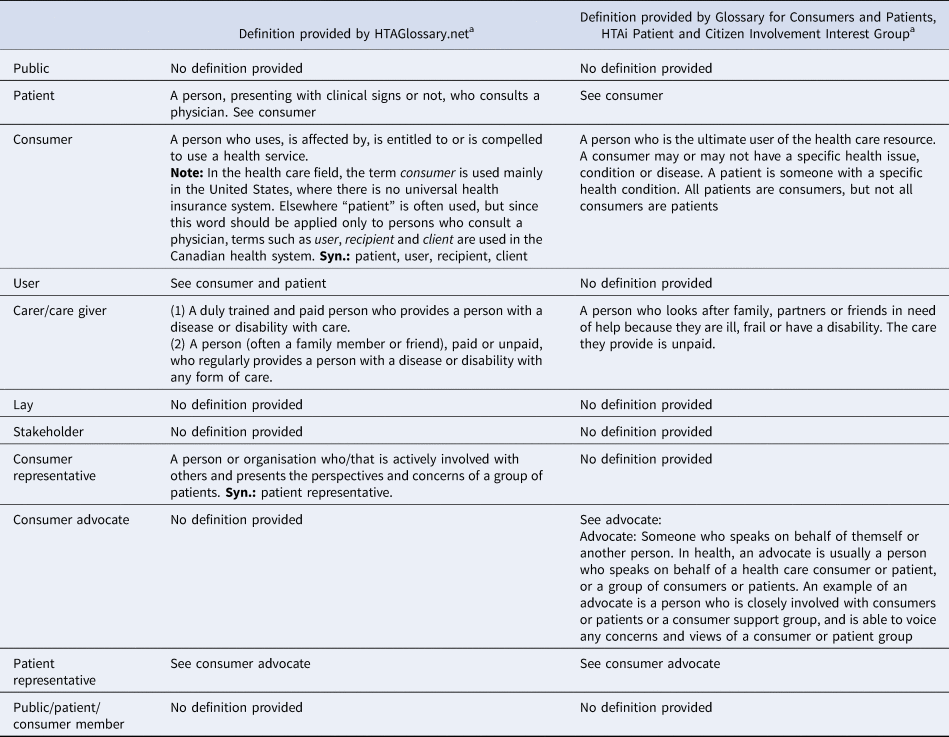

Public and patient involvement in Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and HTA-informed decision making, at least initially, appears to have been undertaken with relatively little attention to the roles these groups might play. Boothe suggests that, without any clear goals, the inclusion of public members in the Canadian Drug Expert Committee was a response to demands by patients’ groups “and a reluctance on the part of experts in agencies responsible to involve patients directly on the committee” (Reference Boothe6, p.639). She also documents how our iterative engagement (Reference Menon, Street, Stafinski and Bond7), described in this paper, sparked intense reflection and debate amongst researchers, agencies, and patient communities (Reference Boothe6) with one ministry official commenting, “they're working on trying to make a conceptual distinction between patient and public…I find that really hard to draw, except at the extreme case” (Reference Boothe6, p.640). As of November 2019, there is no definition of “public” provided in the glossary of Health Technology Assessment international (HTAi) (8) or HTAGlossary.net although there are definitions of patient, consumer, user, advocate, and patient representative (see Table 1). In the main, the definitions describe the type of individual involved and not the interests that they represent. To date, in many cases, the distinction between “public” and “patient” or “consumer” has failed to penetrate the working processes of HTA and HTA decision making. A summary of public and patient involvement across countries is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1. Definitions in Common Usage in HTA

a Accessed November 2019.

Implications for Health Technology Assessment

The lack of clarity in the use of these terms has resulted in their inconsistent application across HTA processes around the world. HTA is a multidisciplinary process through which governments compare new health technologies with existing publicly funded medicines, services, and devices. It is based on a systematic evaluation of safety, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and social, ethical, and legal factors. It supports decisions on which technologies to fund and, in some cases, which ones not to fund (9;10).

The past 10 years have seen increasing demand for patient and public involvement (PPI) in HTA and HTA-informed policy decision making (11;12). This has stemmed from a broader move toward patient-centered care in all health systems, a focus on patient empowerment and the associated collectivization of patient voices in patient organizations and lobby groups (Reference Facey, Ploug Hansen and Single12). Also, a desire to address a “democratic deficit” in representative democracies has emerged. Democratic deficit refers to a point at which the public becomes disaffected with governments and political matters because they are not aligned with public aspirations (Reference Norris13). In general, stakeholders, including clinicians, industry, HTA agencies, and government departments, have responded favorably to patient involvement in HTA processes. Patient involvement supports a broad panel of objectives, including improved practice, transparency, legitimacy, and comprehensiveness through the incorporation of valuable information about the “lived experience” of patients and carers (Reference Facey, Ploug Hansen and Single12). However, concern remains that a focus on patient interests may increase pressure to publicly fund particular services, drugs, and devices outside the usual funding criteria. Consideration of public interests—namely appropriate use of limited resources and preservation of a well-functioning health service—can act to mitigate these concerns.

Currently, most HTA decision-making processes are based on systematic reviews of safety and effectiveness and an economic evaluation that generates a cost per quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). If the process reflects the values held by society, the use of QALYs assumes that the public and patients highly value population health maximization. In most countries, however, there has been little empirical work on what the public values in terms of health technologies or what constitutes the public interest. Where this research has occurred, the public prioritized funding of technologies based on other criteria, namely, equitable distribution of resources, life-saving treatments, prevention, and interventions for children (14;15).

In Australia, the Consumer Consultative Council is designed to reflect consumer rather than public interests. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) and Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) processes allow and invite public input but the process primarily attracts submissions from patients, carers, and patient advocacy groups (Reference Wortley, Wale, Facey, Ploug Hansen and Single16). In 2006, the Canadian Drug Expert Committee added two public members and the Ontario Committee to Evaluate Drugs added two patient representatives but the role of both is to collect, interpret, and present information from patient groups (Reference Boothe6).

In the UK, through input from the Citizens Council, NICE has included a public perspective on broad moral and ethical issues in public healthcare policy sometimes at odds with economic imperatives (Reference Shah17). Recommendations from the Citizens Council are not directly incorporated into NICE guidance but are included in Social Value Judgement documents with which decisions are expected to align. The Citizens Council has examined trade-offs between equity and efficiency (14), and departures from the recommended ICER threshold (15). Whilst this has provided important community input into specific moral and ethical issues surrounding health funding decisions, it does not provide public input in the same way that clinician, health economist, and consumer advocate input is currently provided. In addition, it is unclear whether the general value statements are interpreted such that the final decisions would align with technology-specific recommendations if they were made directly by a public panel.

Despite the involvement of patients and the public in HTA processes for more than a decade, standardized methods are underdeveloped. This has resulted in the use of the terms “patient” and “public” interchangeably in many HTA organizations. (5;6). The lack of guidance around the use of terms is at odds with the traditionally rigorous standards employed in HTA to assess the safety, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of health technologies (18;19). It also contributes to the potential for “mismatched expectations” (Reference Fredriksson and Tritter5, p.96) in decision making, leaving PPI in the HTA process open to criticism. In addition, where this conflation occurs, public interests may not be explicitly included in HTA decision making but rather they are considered in an ad hoc manner dependent on the inclination of those involved.

This paper clarifies the goals, terminology, interests, and roles for public involvement in HTA processes and provides a rationale for why the role of the public should be distinguished from that of patients, their families, and caregivers.

Methods

The term HTA was used as defined in HTAGlossary.net (accessed November 2019), an official collaboration between the peak HTA bodies including HTAi and International Network of Agencies for HTA. This definition excludes “decision making” from HTA. The decision-making step is an important point for the incorporation of public values in funding decisions and therefore we included the consideration of HTA-informed decision making in this work. To conceptualize an operational definition for the “public” in the context of HTA and possible goals for their involvement, we drew from (i) the literature reviews we had previously conducted on the use of deliberative methods in HTA (see 23 and 24 in Table 2), (ii) our own primary research on the inclusion of patient and public voices in HTA (see 16–19, 21, 22, 26, and 28 in Table 2), and (iii) additional relevant key scholarly papers identified primarily through a literature review conducted for the doctoral thesis of author EL and with a small number of papers offered by participants in the consultation process described below (see 1–15, 20, 25, and 27 in Table 2).

Table 2. Literature Used to Support the Development of an Operational Definition for the “public” in the Context of HTA and Possible Goals for their Involvement

We applied an iterative process with stakeholders over several years. Draft definitions were refined in consultation with academic researchers and practitioners of PPI processes in HTA, including members of the HTAi Patient and Citizen Involvement Group (PCIG) (http://www.htai.org/interest-groups/patient-and-citizen-involvement.html). We note that initially, the distinction between patient and public was highly contentious as some argued that all stakeholders, including patients and craft groups, were members of the public. A version of the document was released for a consultation to the PCIG/HTAi working groups during the period from July to September 2016. The feedback received was then used to refine the list of goals for involvement and develop a nomenclature for different types of public in the HTA process. Subsequently, the definition and goals were refined at a workshop involving individuals from different stakeholder groups at the 2017 Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) Conference in Ottawa (Reference Menon, Street, Stafinski and Bond7). A revised document was released to the PCIG, the workshop participants and the Australian public and patient engagement advocacy group, Health Technology Assessment—Australia (HTA-Aus), for a second round of consultation early in 2018. The final description was presented at the 2018 HTAi conference.

Findings

Participants in the consulted groups agreed that clearer definitions of PPI were needed. The rationale for patient involvement was seen as relatively well defined (Reference Facey, Ploug Hansen and Single12), namely to reflect the patient experience of diseases and technologies used in their treatment, to ensure that patient priorities were considered and to support the inclusion of the views of those stakeholders who would be most impacted by the decisions. Clearly, patients are consumers (or users) of technology but consumers may also be healthy individuals who undergo screening or use vaccines or other preventive technologies. The role of consumers in HTA is very similar to those of patients, namely to reflect the consumer experience with these technologies and to support the inclusion of consumer views in decision making. Goals for public involvement, which constitutes the public, the nature of public interests, and the lines of separation between public and patient and consumer interests were seen as much less well defined. Participants described six possible goals for public involvement in HTA.

The Goals and Rationale for “public” Involvement

The goals for including the public are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Goals for Public Involvement in HTA

The rationale for these goals is as follows:

(1) To improve the comprehensiveness of evidence underpinning the decision making for individual health technologies

The public may offer important insights into the value proposition of specific public health-related technologies, such as vaccines or health promotion and screening programs. They may also help to ensure that technologies which elicit strongly held social and cultural values, such as contraceptives or assisted reproductive technologies (Reference Hodgetts, Hiller and Street20) or those being considered for disinvestment (Reference Street, Callaghan, Braunack-Mayer and Hiller21), are assessed as holistically as possible.

(2) To increase the legitimacy of the process for the assessment of preventive technologies, thereby ensuring public uptake of the findings

The public utilize preventive technologies; vaccines are an important aspect of public health, which is threatened by concerns about their safety. Similarly, doubts about the effectiveness of some screening programs impact their uptake (Reference Bosely22). Greater public involvement in HTA processes, with associated improved public understanding, may increase legitimacy, allay community fears, and improve uptake.

(3) To increase the capacity of the public to engage in their own health care

Health literacy and public understanding of the assessment of new technologies may be improved by making the process of HTA more accessible to the public and more transparent. A more “health literate” public is a public more likely to become informed about their own health care: this is an essential plank for improving population health and building support for public health measures.

(4) To improve the involvement of members of the public in the democratic process

Over the past 20–30 years, there has been a demand for a more devolved participatory democracy in developed nations. The drivers for this demand include increased availability of evidence to all (Reference Couldry23), the rise of social media with national and global public discussion of policies (Reference Rheingold24), falling trust in governments (25), and the recognized “weaknesses in traditional representative structures” (Reference Mullen, Hughes and Vincent-Jones26, p.22). Loss of trust in governments and representative democracy is particularly evident in younger voters (Reference Oliver27). Public participation in policy development and decision-making processes has high levels of support amongst younger voters and could be seen as a mechanism for overcoming some of the weaknesses in a representative democracy, where voting is usually around a “limited set of choices with little depth of involvement” (Reference Mullen, Hughes and Vincent-Jones26, p.22). Some governments are now including deliberative informed public involvement processes in specific cases where decision making is contentious (e.g., 28).

(5) To ensure that the HTA process aligns with public values and that the interests of the public are included in the HTA process

Values are intangible standards or principles which guide our choices and behavioral responses and provide meaning to our lives. These might include personal Kantian virtues such as good will and moral duty. At the societal level, such virtues underpin public values of fairness, accountability, and integrity. Public values are typically elicited through empirical research (e.g., citizens' juries).

Interests embody the trade-offs we are willing to make in the execution of those values. For example, many people believe autonomy and respect for personal privacy should be underpinning values guiding government processes and decision making. The public interest therefore lies in ensuring that the HTA processes and the subsequent decision making reflect respect for persons. This invariably requires trade-offs with other values. For example, the high public value placed on health and wellbeing and effective health services may require some loss of privacy and autonomy due to sharing of health data. How trade-offs should play out in HTA processes is difficult to decide if we do not understand the range of values held by the public and the weightings the public would make in trading one against the other.

In deliberations determining public values and interests or in the representation of those interests, individuals should come to the deliberation as free as possible from other interests. Although others involved in the HTA process are also members of the public, they represent specific interests, including those of patients, healthcare providers, health administrators, industry, and public services. They are often appointed to committees because of their affiliation with those groups through their work, professional role, and qualifications. The inclusion of members of the public, without particular financial, work, or personal interests in the outcome, in these committees ensures broader representation in decision making and explicit consideration of public interests. In some cases, active inclusion of the public interest may act as a bulwark against powerful vested interests wishing to undermine the rigor, impartiality, and independence of the HTA process.

(6) To assist in explaining to the public the rationale for difficult decisions which deny funding for potentially life-saving or life-altering health technologies

Funding for contentious health technologies which loom large in the public imagination but fail to measure up in the assessment processes is an ongoing issue for governments (e.g., see Reference Abelson and Collins29). In acting as independent advocates for the public interest, public panels or public members present the public interest argument for denying or approving public funding for technologies which are considered overly expensive relative to the public benefit or for which evidence of benefit is equivocal. This is an extension of goals 5 and 6 in that, under these circumstances, PPI acts as a conduit for public education and informed debate but also as a process for formal input on public interests and values.

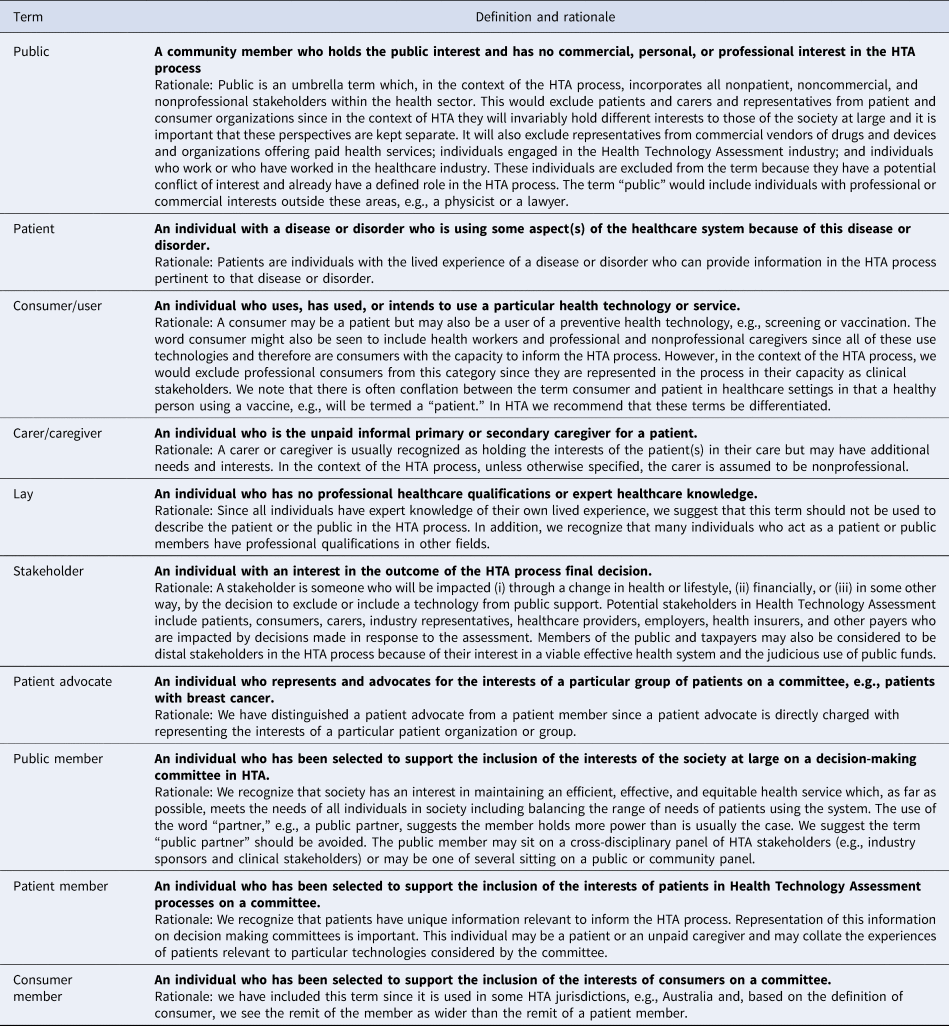

Defining Terminology for “the public” in HTA and HTA-Informed Decision-Making

In Table 4, we define terms which have been loosely defined and often used interchangeably in the HTA community. These terms were developed from scholarly literature and in consultation with a broad group of members of the HTAi community, but we suggest that there is no right or wrong definition. The actual term used is less important than achieving consensus from the HTA community about what the terms mean. In other areas of HTA, there is a clearly understood shared language.

Table 4. Definitions of Terms for Use in Public and Patient Involvement in the Context of Health Technology Assessment and HTA Decision Making

In the consultation process, our original definition of public, drawn from the literature, was expanded to describe particular exclusions such as those individuals representing commercial industries manufacturing drugs and devices, the HTA industry, and individuals who work or who have previously worked in the healthcare industry. In addition, we excluded individuals with personal interests from this term, including patients and carers, so as to be consistent about the inclusion of the public interest. Other definitions were also refined in response to feedback. For example, our original definition described a patient as someone “with a diagnosed disease or disorder.” As a result of the consultation, the word “diagnosed” was dropped as being too narrow and the sentence: “An individual with the lived experience of a disease or disorder who can provide information pertinent to that disease or disorder” added in order to describe the contribution such a person might bring to the HTA process. The term “representative” was removed and the word “represent” used carefully since the capacity or remit for a person to “represent” patients or the public was seen as problematic. Therefore, the word was only used to describe individuals who were consumer or patient advocates and thus specifically asked to represent the views of others. Finally, we recommend against the use of the term “lay.” Although considered a neutral term by some (Reference Popay, Williams, Thomas and Gatrell30), in the context of HTA decision making, where we are making the case for public and patient expertise, it is damaging: for example, current common dictionary synonyms for the term include amateur, inexpert, unqualified, and dilettante.

Discussion

Fifty years after Arnstein's ladder of citizen participation (Reference Arnstein1) and 13 years after Tritter and McCallum's work on user involvement (Reference Tritter and McCallum2), the conceptualization of public involvement in public decision making has shifted. Arnstein's ladder reflected the paternalistic and rigid processes of the sixties and the contemporary push for more participatory processes and “citizen power.” Tritter and McCallum's reformulation reflected the rise of patient-centered care, the empowered patient and advocacy for patient involvement in those decisions which affected them. By 2007, it was clearly problematic to ask patients to manage their own care while denying them any input into the very decisions which affected the range of health technologies to which they had access. The latest iteration in this debate, which we describe in this paper, is the recognition that patients and the public hold very different interests and both sets of interests should be systematically incorporated into public decision making.

It is difficult to comment on differences between the public and patient populations in terms of their held values since there is little empirical evidence drawing this comparison. There is some evidence that even where values are shared they may be differently weighted, for example, some studies suggest that patients have a higher tolerance of risk than the public (Reference Lindsay-Bellows31). However, as the findings from this article and Boothe (Reference Boothe6) suggest, the interests of patients, patient advocates, and patient members lie primarily in advocating for specific medicines or treatments which will benefit a particular patient group, whereas the interests of the public will always rest not only in ensuring equitable distribution of scarce resources amongst all patient groups but also in supporting a well-functioning society which sustains the wellbeing of all. Further, the goals of PPI described in this paper go well beyond the instrumental goals which might be met through observing changed recommendations from an advisory committee or an altered final funding decision as a result of PPI (Reference Boothe6). This narrow understanding of the potential impact of PPI neglects the benefits of a more transparent and inclusive process particularly in democratic accountability and in maintaining and rebuilding public trust in government decision making (Reference Boothe6). More empirical research is needed to explore whether increased public and patient involvement increases public trust in the HTA process.

The ways in which Australia, Canada, and the UK conceptualise public and patient engagement in HTA processes, described in the introduction to this paper, exemplify one way of differentiating the roles of patients/consumers and the public. This was identified by Fredriksson (Reference Fredriksson and Tritter5) as patient and consumer views drawing on “experiential knowledge generated from being a service user” and public views, exemplified by the UK NICE Citizens Council, as “collective perspectives generated from diversity” (Reference Fredriksson and Tritter5, p.97). Our work points to a different interpretation: the terms describing patient and public in HTA should not describe who the people are but rather the interests and values they are tasked to present in the HTA process or at the decision-making table.

Arising from the public involvement goals described in this paper, our work suggests that there are two distinct aspects to the interests held by the public which should be explicitly included in the HTA process. The first lies in ensuring democratic accountability in the process, namely that it includes comprehensive, high-quality evidence, good deliberation, and is free of bias from special interests. In this role, public members act as independent auditors for the process, building legitimacy and public trust for the process. The second ensures the inclusion of public values. These values would need to be delineated in diverse informed deliberative fora. The role of a deliberative public council might be to develop a generic set of values similar to the operation of the NICE Citizens Council with explicit inclusion of these values in the process. For example, individuals from the council might sit on any decision-making body or be embedded in the HTA process. Alternatively, contentious decisions in HTA could be directly considered by a public council. The ways in which the public values and interests are explicitly included in HTA and the HTA decision-making process will need to be developed within each jurisdiction to reflect the particular policy context. Potentially, public representation could act as a broker between the broader public and the decision-making committee, assisting in the dissemination of the rationale for decisions and increasing public understanding of the HTA process.

Conclusion

Including the public and patients in HTA and HTA-informed policy decisions has become imperative in many jurisdictions using HTA as the basis for government healthcare provision. However, their inclusion has been compromised by the lack of clarity around goals and the roles of the public and patients. This paper provides definitions of those goals and roles drawn from the literature and shaped in a consensus building process. The definitions provided here are particular to the HTA context, but may also be useful in other areas where patients and the public are included in decision making. The next step is a broader discussion across all HTA stakeholders in order to provide an industrywide understanding of the distinct roles and interests of the patient and public members in the HTA process.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462320000094

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the members of the HTAi/PCIG, HTA-AUS group, and the CADTH workshop and other HTAi members in engaging in robust discussion, providing feedback, and refining the nomenclature.