Often interchangeably known as rationing or resource allocation, priority setting calls for processes that decide about allocation of resources between competing health programs (Reference Sibbald, Singer, Upshur and Martin1–Reference Williams3). Every nation faces the challenge to provide access to comprehensive healthcare services within the constraint of finite available resources. Prioritization is influenced by clinical and cost-effectiveness evidence, political, economic, and social factors, and health system constraints (Reference Baltussen, Jansen and Mikkelsen4). In the light of recently announced Sustainable Development Goals 2030 agenda, several low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) aspire to move toward universal health coverage (UHC) (5). This calls for setting explicit priorities with explicit defined criteria to prioritize spending on publicly funded health care. Often, priority-setting criteria are necessitated by rising population demands in healthcare services, constrained health budgets, lack of legal frameworks, inadequate data on effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness (Reference Ham and Coulter6).

Conceptually, two schools of thought on priority setting exist in the literature. The first, consequentialism, relies on the premise that only outcomes of an action are important and excludes giving any importance to the processes that were involved in achieving those outcomes (Reference Mooney7;Reference Jan8). An example of underpinnings of consequentialism lies in which economic evaluation is done through cost-effectiveness/cost-utility analysis, wherein outcome is solely judged in terms of health, such as quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) or its proxies, and does not place any importance to processes involved (Reference Mooney7). It is also referred to as “the ends justify the means” concept (Reference Jan8). The second is proceduralism, that places importance to the processes involved in achieving a particular outcome and also facilitate in achieving procedural justice with addressing equity dimension (Reference Ham and Coulter6–Reference Jan8). Over the recent years, significant attention to proceduralism has been reported in the literature with respect to healthcare priority setting (Reference Jan8–Reference Daniels and Sabin10).

In LMICs, priority-setting processes are generally ad-hoc or implicit (Reference Kapiriri and Martin11). Haphazard rationing and the absence of reliable evidence for informing priority setting often acts as a deterrent to UHC and may lead to inefficient spending on health in developing countries (Reference Glassman and Chalkidou12;13). Systematic approaches to priority setting used in high functioning health systems include program budgeting and marginal analysis (PBMA), accountability for reasonableness (AFR), multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA), health technology assessment (HTA), and Cookson and Dolan (Reference Cookson and Dolan45) (refer to Supplementary Box I) (Reference Soto, Alderman, Hipgrave, Firth and Anderson14). Priority-setting decisions primarily occur at three levels within the health system: macro, meso, and micro. While the macro level corresponds to global/national level, the meso level may refer to provincial/regional/district depending upon a country's health system and micro mainly considers hospital or facility level (Reference Kapiriri and Norheim15).

A range of work had been done to identify common criteria or approaches in context of priority setting internationally (Reference Barasa, Molyneux, English and Cleary9;Reference Musgrove16–Reference Kapiriri and Razavi20). For LMICs, previous reviews had primarily attempted listing of criteria (Reference Youngkong, Kapiriri and Baltussen21) or identified the systematic approaches used for priority setting in LMICs (Reference Hipgrave, Alderman, Anderson and Soto22). One review listed criteria and specifically approaches that incorporates evidence from economic evaluation for setting priorities in health care in LMICs (Reference Wiseman, Mitton and Doyle-Waters23). However, little is known from previous works if any variation in frequency of use of these decision criteria exists by different levels, methods or approaches used in priority-setting studies in case of LMICs. This review follows on from the previous work done so far and attempts to address these gaps in available evidence base.

The primary aim of this review was to identify the criteria being used in priority setting for public health resource allocation in LMICs. The secondary aim was to elucidate the core policy aspects at play (content, process, context, and actors) in priority setting in LMICs in accordance with the application of a policy triangle (Reference Walt and Gilson24). The specific objectives were to report on overall frequency of use of decision criteria for public health interventions and essential care or benefit packages. This work will provide a useful contribution to the scant literature on criteria used to set priorities and inform health resource allocation decisions in LMICs.

Methods

Search Strategy

The design of this systematic review is based on Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) guidelines for conducting the searches, analysis, and writing the manuscript (25). In addition, a policy triangle (Reference Walt and Gilson24) is applied to those studies included in this systematic review to explicitly explore the policy context and implications of priority setting in LMICs. Systematic searches (electronic) were carried in four databases: Pubmed, Embase, Econlit, and Cochrane. The search strategy was centered on the research question of the review and divided into two main concepts, priority setting in health care and LMICs. Synonyms for both search concepts were searched in Google and previous papers. A combination of MeSH terms and keywords used and the detailed search strategy are available in Supplementary File provided.

Initially, the search strategy was formulated for Pubmed and subsequently modified as per other databases. In addition to electronic searches, bibliographic searches of the relevant studies and reviews along with pre-identified Web sites were also performed till June 2017. No filters in terms of time-period, language, or study design were applied. Studies in non-English language were documented to assess the extent of this literature available on priority setting in LMICs. However, the non-English literature was excluded at the time of analysis. The review protocol is registered in International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews PROSPERO CRD42017068371.

Screening Strategy and Identification of studies

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were outlined in study protocol (Reference Kaur, Prinja, Sharma and Teerawattananon26) and were based on Population, Intervention, Comparator, and Outcome (PICO) format. Population was identified as studies from all low- and middle-income countries, as defined by the (World Bank country classification by income). The processes of priority setting were considered as equivalent to the intervention in this review. No comparator was deemed necessary as per the research question. Outcomes were classified as primary and secondary, where the decision criteria elicited in priority setting was the primary outcome of interest, and key factors/ barriers to priority setting were identified as secondary outcomes. Any study that referred to relevant criteria or process for decision making was considered for inclusion for full text review. Exclusion criteria consisted of all studies primarily focused on high income countries. Furthermore, examples of priority setting in the field of health research other than priority setting for public health resource allocation or non-health fields, opinion piece, letters, editorials were also excluded.

Two authors (G.K. and D.S.) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all studies identified from search strategies. Subsequently, screening of full text articles was done independently by same authors (G.K. and D.S.). Any disagreements at any stage of the review were resolved by consultation with the third reviewer (S.P.) until a full consensus was reached.

Quality Assessment

The Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs (QATSDD) (Reference Sirriyeh, Lawton, Gardner and Armitage27) was used to quality-assess all studies. This tool has 16-point criteria that allows for the assessment of quality of studies with either quantitative, qualitative or studies with both quantitative and qualitative research designs. However, in case of studies with quantitative or qualitative designs, only fourteen criteria were used to assess for quality based on the tool (Reference Sirriyeh, Lawton, Gardner and Armitage27). The QATSDD has high face validity, and good inter-rater and test–retest reliability in evaluating qualitative as well as quantitative studies (Reference Sirriyeh, Lawton, Gardner and Armitage27).

Each criterion was evaluated on a 4-point scale where 0 = the criterion is totally undescribed, 1 = described to some extent, 2 = moderately described and 3 = described in full. The quality assessment of included studies independently by two reviewers (G.K. and D.S.) was done. Reviewer inter-rater agreement rate (kappa statistic) was calculated, and for kappa below 0.7, those points were resolved in discussion with third reviewer (S.P.) until a final consensus was reached. All scores for each study were summed, representing the total score. Combined mean reviewer scores were calculated. On the basis of these scores, studies were categorized as being of low (when mean score from 0 percent to 35 percent); moderate (when mean score from 35 percent to 70 percent) and high quality (mean score greater than 70 percent) (Reference Hardy, Johnson, Sharples, Boynes and Irving28). However, no study was excluded in final analysis based on study quality.

Data Extraction

Considering the diverse designs of included studies, separate templates for data extraction for qualitative, quantitative, and studies using both qualitative and quantitative designs were developed, and piloted with 20 percent of total studies for each design. Minor modifications in the data extraction templates were done after full consensus with a third reviewer. Two independent reviewers extracted data for the main outcome, which is criteria elicited for priority setting, and other relevant characteristics of the included studies in LMICs like type of country (by income), methods, domain, and level of prioritization, stakeholders involved and barriers to priority setting. Furthermore, we reported on criteria stratified by priority-setting approaches and methods, domain of prioritization (generic/specific), at overall and various levels (macro, meso, and micro) in LMICs. The macro level was considered as the national, meso as the district, and micro as the hospital level. Under generic domain of prioritization, priority setting for health interventions in multiple programs was considered. The specific domain of prioritization referred to priority setting for health interventions under a particular health program.

Analysis of Included Studies

The extracted information was sorted into the four domains (content, process, context, and actors) in the policy triangle given by Walt and Gilson (1994) (Reference Barasa, Molyneux, English and Cleary19;Reference Walt and Gilson24). We considered a priori our primary objective of identifying criteria for priority setting as part of content section. The different themes/criteria were extracted manually and combined under common concepts to arrive at the final list of criteria (Reference Guindo, Wagner and Baltussen18). Furthermore, the information was also extracted on use of specific approaches, methods, techniques for eliciting and assigning relative importance (any weighting) to criteria were considered under the process category. Domain of prioritization, presence of situational factors like political arrangements, financial factors and barriers to priority setting were identified as part of context analyses. The stakeholders consulted in these studies were considered actors within the realms of policy analysis. The data extracted was primarily qualitative in nature and descriptively analyzed in terms of counts and percentages of occurrence of terms/criteria in the included studies. The findings have been reported in the form of text, tables, and graphs in the subsequent section.

Results

Study Selection

Based on PRISMA guidelines (Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman29), the process of study selection in this review is summarized in Figure 1. Of the 18,397 records identified through electronic and bibliographic searches, 16,412 records were selected for first stage screening based on title and abstract. Subsequently, in accordance with pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, 112 articles were reviewed for full text screening; and finally, forty-four papers were included in this review. The following sub-sections present review findings in terms of: characteristics of included studies; their methodological approaches; quality assessment; identified priority-setting criteria. These findings are subsequently aligned under the four domains of the policy triangle (content, process, context, and actors) and reported in subsequent sections (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. PRISMA Chart.

Characteristics of Included Articles

The time-period of articles included in this review was between 2000 and 2016 (refer to Supplementary Figure 1). Most of these studies were carried out in upper middle-income countries (UMIC-40 percent) followed by low-income countries (LIC-37 percent) and lower middle-income countries (LMIC-23 percent). According to World Health Organization (WHO) regional groupings, majority of studies were from the Africa region (refer to Supplementary Figure 2). Priority setting processes were studied most frequently at macro level in all three country-income groups (LIC, 69 percent; LMIC, 90 percent; and UMIC, 88 percent). Meso level was considered in only one-quarter of studies in LIC and one-tenth in LMIC. Micro level studies constituted 12 percent in UMIC and 6 percent in LIC regions.

Two studies that reported on processes and stakeholders’ views were not considered while analyzing the frequency of use of decision criteria (Reference Makundi, Kapiriri and Norheim30;Reference Mshana, Shemilu and Ndawi31). Reviewer interrater agreement rates (G.K. and D.S.) for quality assessment of included studies were calculated and were mostly high (if > 0.7) (refer to Supplementary Table 1). Quality assessment showed that, on an overall level, more than 84 percent of included studies were of high quality. Based on the criteria mentioned in QASTDD tool, the included studies were further appraised by methods and their individual criteria scores for each design were also computed (refer to Supplementary Table 2).

Content

Criteria Elicited in Priority-Setting

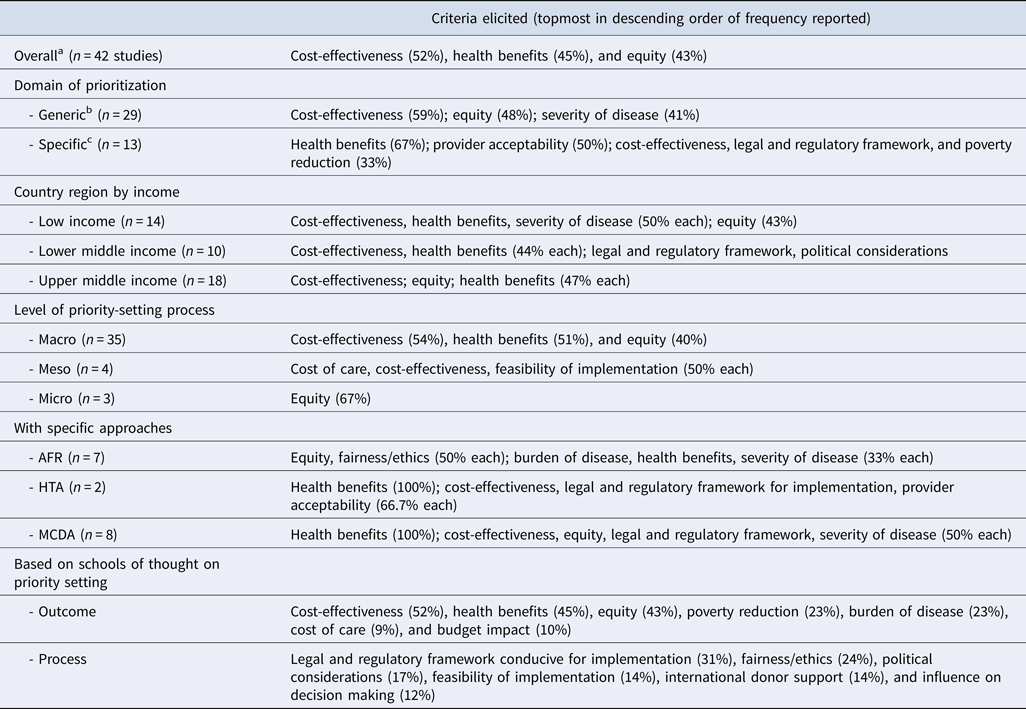

Overall, we found that cost-effectiveness was the most commonly (52 percent) reported criteria for priority setting. Health benefits (45 percent), equity (43 percent), severity of disease (33 percent), and legal, regulatory framework conducive for implementation (31 percent) were other notable identified criteria. To this end, studies that reported health benefits criteria, close to half (48 percent) of them primarily reported benefits with clinical outcomes (effectiveness/efficacy of intervention) and 26 percent each separately for population and individual level benefits. Distribution of criteria by country region showed that cost-effectiveness and health benefits were highest two criteria, common in low-income and middle-income countries. Details of criteria elicited and their key domains are provided in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 3, respectively. Furthermore, 70 percent of studies with the generic domain of prioritization reported cost-effectiveness as the most frequent criteria.

Table 1. Summary of Key Criteria Used in Priority Setting in Included Articles

aTwo studies that did not report on criteria were not included in analysis on frequency of use of criteria.

bGeneric indicates health interventions in multiple programs.

cSpecific indicates related to particular health program.

AFR, accountability for reasonableness; HTA, health technology assessment; macro, national; MCDA, multi-criteria decision analysis; meso, district; micro, hospital.

On the other hand, health benefits was cited as the most common criterion in the rest of the studies that had considered specific domain of prioritization. To this end, under specific domain of prioritization, highest criteria specific for programs such as HIV programs showed that health benefits, fairness/ethics, international donor support, and provider acceptability were key criteria. While for studies involving selection of health interventions for benefit packages reported on poverty reduction followed by cost-effectiveness, equity, fairness/ethics, health benefits, legal and regulatory framework, and severity of disease. Studies using either of any approaches reported use of health benefits (59 percent); burden of disease, cost-effectiveness, and legal and regulatory framework (41 percent) followed by equity and severity of disease (35 percent each) as the priority-setting criteria. Furthermore, detailed criteria with respect to individual studies and most commonly used approaches (MCDA, HTA, AFR) are shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 3, respectively. In studies using no specific approach/framework, cost-effectiveness was the predominant criteria, besides equity (44 percent) and health benefits (32 percent).

Table 2. Key Criteria by Individual Studies

aDomain of prioritization: generic, health interventions in multiple programs; specific, related to particular health program.

AFR, accountability for reasonableness; HTA, health technology assessment; macro, national; MCDA, multi-criteria decision analysis; meso, district; micro, hospital.

Furthermore, cost-effectiveness (44 percent) was the highest criteria reported in studies using qualitative methods. Cost-effectiveness and equity (60 percent each) was reported in studies using quantitative methods and health benefits (67 percent) in studies with both quantitative-qualitative methods. In line of findings of our review, we considered cost-effectiveness, health benefits, equity, poverty reduction, burden and severity of disease, cost of care and budget impact as outcome-oriented criteria. While, other criteria elicited in our systematic review, such as legal and regulatory framework conducive for implementation, fairness/ethics, political considerations, feasibility of implementation, international donor support, influence on decision making, fall under processes of priority setting. In a sub-group of studies conducted in Asian region, we identified cost-effectiveness as being the most commonly stated criteria, followed by both equity and health benefits.

Table 1 provides a summary of key criteria used in priority setting in included articles. Table 2 provides key criteria by individual studies.

Contemplating for any variation by stakeholder groups, our findings showed that international donor support (60 percent); cost-effectiveness, cost of care, affordability from patient perspective, feasibility of implementation, legal and regulatory framework, and political considerations (40 percent each) were equally reported chief criteria in studies that had civil society participation. On the contrary, studies where these stakeholders were not considered or not reported, cost-effectiveness (50 percent), health benefits (45 percent), and equity (45 percent) were chief criteria. Of interest, cost-effectiveness was the most frequently reported criterion in studies whether general population was involved or not. Health benefits (75 percent) followed by provider acceptability (63 percent) were chief criteria elicited where patient group representatives were included.

Process of Priority Setting

Methods Used. Forty-three percent of studies reported use of qualitative methods, 36 percent used quantitative methods, while 24 percent used both qualitative as well as quantitative methods to assess priority setting processes. In particular, questionnaire survey (33 percent), in-depth interviews (24 percent), focused group discussions and consultative sessions (14 percent), and discrete choice experiments (12 percent) were frequently cited techniques used to elicit priority setting processes in the included studies. Furthermore, in approximately 21 percent of all studies, stakeholders’ perspective on priority setting was taken; 14 percent studies merely described the priority setting process, while another 14 percent described and evaluated the priority setting process.

In addition, 43 percent of included studies used specific approaches/frameworks to elicit criteria for priority setting. Systematic approaches used were MCDA (7 studies); AFR (6 studies); HTA (2 studies); balance sheet, TELOS (technical, economic, legal, operational, and scheduling) framework (Reference Cookson and Dolan45), Cookson and Dolan (Reference Cookson and Dolan45), and with both MCDA and AFR (one study each). Furthermore, these studies using specific approaches also weighted and ranked the health interventions. Two most common means used for weighting criteria were agreement on pre-ascertained scale and use of regression coefficients obtained through carrying out discrete choice experiments.

Context of Priority Setting

Approximately 70 percent of studies considered a generic prioritization; while the rest undertook priority setting for any specific health program. In terms of specific program, one study each considered priority setting for drug-reimbursement, new vaccine introduction, safe motherhood program, malaria treatment, cardiovascular disease, and breast cancer. Moreover, four studies evaluated about prioritization for health benefits package and four for national level HIV/AIDS program. With regard to contextual factors in priority setting, two studies evaluating priority setting processes reported that political pressures and international priorities play an important role at macro level decisions in priority setting processes in developing countries with decentralized health systems (Reference Kapiriri, Norheim and Martin32;Reference Colenbrander, Birungi and Mbonye33). Also, lack of resources and insufficient funding influenced on allocations for priorities of importance at meso and micro levels (Reference Kapiriri, Norheim and Martin32;Reference Maluka, Kamuzora and San Sebastian34).

Two studies perceived lack of knowledge about economic evaluations and difficulty in interpretation of scientific literature at macro and meso levels as a barrier to explicit priority setting while exploring on how healthcare decision makers implement these resource allocation decisions (Reference Mshana, Shemilu and Ndawi31;Reference Rubinstein, Belizan and Discacciati35). It further cited difficulty in generalizability of cost-effectiveness results from the developed countries to the developing countries as factor impeding on use of economic evaluation evidence in the priority setting (Reference Rubinstein, Belizan and Discacciati35). Another barrier identified pertained to lack of any standardized processes and insufficient information for data use in decision making at the meso level (Reference Maluka, Kamuzora and San Sebastian34;Reference Avan, Berhanu, Umar, Wickremasinghe and Schellenberg36).

Actors

On an overall level, the composition of stakeholders/actors consulted in priority setting processes were policy makers (81 percent), health professionals (42 percent), general population (26 percent), patients and their organizations (21 percent), researchers (19 percent), civil society representatives (14 percent), reimbursement managers (9 percent), pharmaceutical representatives (7 percent), international donor support representatives (5 percent), and ethicists (2 percent). Policy makers were leading stakeholders that were most frequently consulted in all levels (refer to Supplementary Figure 4). Stratifying by methods used in the included studies, again policy makers were most commonly consulted stakeholders followed by health professionals. Similar findings were seen in studies with generic prioritization and whether any approach used or not. However, for specific programs, stakeholders from patients and their organizations were the second most consulted along with health professionals subsequent to policy makers. With regard to decision making, another three studies reported that policy makers at macro level decided on the context of priority setting for meso and micro levels (Reference Kapiriri and Norheim15;Reference Kapiriri, Norheim and Martin32;Reference Maluka, Kamuzora and San Sebastian34).

Discussion

This review investigated the primary criteria used in LMICs to inform priority setting for resource allocation in healthcare, and explored the key dimensions of these criteria according to a well-defined policy framework. To the best of our knowledge, this review provides the first comprehensive overview of the various criteria used to inform priority setting in LMICs at macro, meso, and micro levels of the health decision-making space, and the range of stakeholders and contextual and process related factors of importance at the various levels of priority setting in these countries. The findings of this review have important implications for furthering the scientific literature and enhancing general understanding of how decisions are made toward the allocation of resources in health in LMICs.

This review found cost-effectiveness was the most emphasized criterion at an overall level in resource allocation decisions in LMICs. The majority of included studies focused on the macro level, with policy makers as the most frequently consulted stakeholders in the included studies. Furthermore, stakeholders from the general population were more frequently cited as part of priority setting studies in LIC than LMIC and UMIC. Stakeholders from patient organization were frequently involved in the priority-setting process in circumstances where the AFR approach was used. However, at an overall level, we observed an under-representation of patient organizations and civil society in priority setting. We did not find any study in LMICs that reported using the PBMA approach for making resource allocation decisions (Reference Hipgrave, Alderman, Anderson and Soto22). In addition, we found that an MCDA approach was more frequently used in UMIC, and an AFR was more frequently used in LIC.

The findings of cost-effectiveness as the primary criterion for informing priority setting in LMICs is unsurprising given the international focus on cost-effectiveness as an essential priority-setting criterion, driven by global initiatives such as the World Health Organization project Choosing Interventions that are Cost-Effective (WHO-CHOICE) and the Disease Control Priorities Project, which provide evidence on cost-effectiveness of selected health interventions in developing countries (37;Reference Jamison, Breman and Measham38). Health benefits and equity were also found to be common criterion for informing resource allocation decisions in many categories analyzed in this review, highlighting a common tendency for outcome-oriented criteria to drive decision making in LMICs. However, we note that relying solely on outcome-oriented criteria captures only one side of the priority-setting picture. Incorporating process criteria into the resource allocation decisions would assist in achieving the goal of procedural justice and facilitating more transparent, fair, and explicit decision making (Reference Baltussen, Jansen and Mikkelsen4;Reference Barasa, Molyneux, English and Cleary9). It is important to mention that these criteria are not decision rules but decision aids. Many a times these criteria are in conflict with each other (Reference Jan8;Reference Norheim, Baltussen and Johri39). Henceforth, the stakeholders need to be cognizant of the fact that different health interventions consider different criteria, and there may be differentials across these decisions depending upon the context of priority setting.

The majority of included studies in this review focused on the use of priority-setting criteria to inform macro-level decisions. In countries with decentralized health systems, the levels of priority setting are of paramount importance in policy decisions (Reference Kapiriri, Norheim and Martin32), in terms of macro-level national decisions regarding what gets funded; and how and where policy decisions are implemented at the meso and micro level within the public system.

Furthermore, there should be emphasis on involvement from public and community as these stakeholders understand the local context and preferences in a more apt way (Reference Hoedemaekers and Dekkers40). Moreover, their involvement opens the possibilities of provision of justification by decision makers for decisions made thereby improvising accountability, options of revisions or re-appeals and precludes chances of ad-hoc/implicit judgements (Reference Daniels and Sabin10).

We would like to note the limitations of our review. First, the included studies were restricted to only peer-reviewed articles and did not include gray literature, which may have skewed or restricted the pool of studies assessed under this review. Second, the stated criteria for priority setting may differ from the methods used in real-world setting. While the stated criteria can be elicited from interviews, the actual methods or criteria used can only be assessed by observing the processes followed in priority setting in real world. Third, it could not be ascertained from these studies as to who was responsible for making these decisions. Fourth, there is a need to explore the role of actor-power and its influence on the decision for priority setting. We would recommend these gaps in evidence as priority areas that may be considered for future research. In addition, the evidence in this important area would benefit from assessment of methods and practices of priority setting in real time setting.

In conclusion, our review findings suggest that priority setting in LMICs is largely driven by consideration of evidence for cost-effectiveness and health benefits. Other criteria such as legal and regulatory framework conducive for implementation, fairness/ethics and political considerations were infrequently reported and should be considered by LMICs to strengthen the priority-setting process.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462319000473

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.