Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the most common cancer diagnosed in Europe (Reference Ferlay, Parkin and Steliarova-Foucher3). In 2008 it accounted for 13.6 percent (436,000 cases) of all diagnosed cancers, and 12.3 percent (212,000) of total cancer deaths (Reference Ferlay, Parkin and Steliarova-Foucher3). The European Code Against Cancer recommends that individuals aged 50 and older participate in CRC screening. There are two general categories of screening test: stool-based tests (including guaiac-based fecal occult blood tests [FOBT], fecal immunochemical tests [FIT] and fecal-DNA tests), and structural colon tests (including rigid and flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, and CT-colonography [CTC]). For screening programs, the choice of the optimal test remains uncertain. As a relatively new screening tool, CTC is at the forefront of this uncertainty.

CTC provides 2D or 3D images of the colon and the rectum. Advocated as a minimally invasive alternative to colonoscopy, CTC potentially offers several advantages, including no requirement for patient sedation, short procedure time, and low risk of bowel perforation (Reference Lefere, Dachman and Gryspeerdt17). Detection of extra-colonic findings, such as abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA), offers a possible further advantage, although distinguishing between benign and potentially significant findings remains challenging (Reference Pox and Schmiegel24).

Drawbacks of CTC include cancer-risk associated with radiation exposure (Reference Brenner and Georgsson1), false positives, problems detecting flat adenomas, and an inability to remove polyps or biopsy suspicious lesions during the procedure, necessitating referral to diagnostic colonoscopy. The issue of referral threshold is controversial. While there is a consensus that all individuals with polyps ≥10 mm should be referred for polypectomy (Reference Pox and Schmiegel24), best practice for 6- to 9-mm lesions is uncertain with some advocating removal and others surveillance (Reference Lefere, Dachman and Gryspeerdt17).

To inform the debate on optimal CRC screening tests, we systematically reviewed the evidence on cost-effectiveness of CTC as a CRC screening tool, with a focus on identifying key factors influencing findings. We also report on the methodological quality of CTC cost-effectiveness studies.

Methods

Studies were eligible if they reported an economic evaluation of CTC as a primary CRC screening tool, used cost-effectiveness or cost-utility analysis, included comparison to another screening modality or “no screening” and were published in English in peer-reviewed journals during January 1999 to July 2010. Studies were also required to explicitly present data on endogenous model variables, such as costs and screening uptake. Studies which assessed CTC for diagnostic purposes or, where CTC data was not population-based, were excluded. Electronic databases searched included PubMed, Medline and the Cochrane Library. MeSH headings included, but were not limited to, “colorectal neoplasms”, “colonography, computed tomographic”, “costs and cost analysis”, “cost-benefit analysis”, and “quality-adjusted life years”. Relevant textwords were also included. We searched for, and reviewed separately, studies conducted by health technology assessment agencies which had not been published in journals.

Two reviewers independently reviewed the search results and screened abstracts to select those which warranted more detailed examination. Articles deemed relevant by either reviewer were further scrutinized and full texts obtained. Reference lists of published papers were screened to identify any missed papers. For each included study, the two reviewers independently extracted data on setting, screening scenarios, screening uptake, model, time horizon and outcome, CTC cost, CTC performance (sensitivity and specificity) and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs). Data was also abstracted on whether extra-colonic findings or medical complications were considered.

Cost estimates extracted from reviewed papers were converted to 2010 USD using country specific inflation rates from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and converted to USD using OECD Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) rates (http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx) (Supplementary Table 1, which can be viewed online at www.journals.cambridge.org/thc2012054).

The same authors independently appraised the quality of the included literature using the Drummond 35-point checklist for economic evaluations.

RESULTS

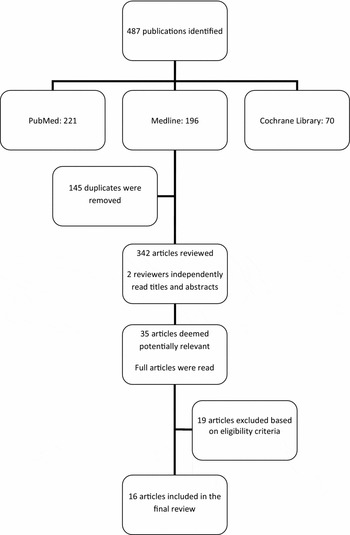

We identified and screened 342 potentially relevant papers. Of these, thirty-five were obtained for detailed consideration; of these, nineteen did not fulfill the eligibility criteria; sixteen were included in the review (Figure 1). Two health technology assessments were also identified (Supplementary Table 2, which can be viewed online at www.journals.cambridge.org/thc2012055); these are not discussed in any further detail.

Figure 1. Numbers of papers identified, reviewed, and included/excluded at each stage of the review.

Quality Evaluation

The 16 studies were of a mid to high quality and generally conformed to current standards of health economic evaluations, particularly regarding study design, and analysis and interpretation of results (Supplementary Table 3, which can be viewed online at www.journals.cambridge.org/thc2012056). Data collection in the literature exhibited lower quality methods. Most studies included only a narrow range of direct healthcare costs.

General Study Characteristics

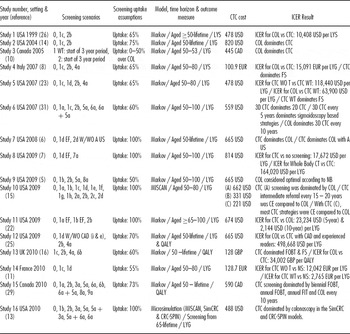

Nine of the sixteen studies shared one or more researchers (Table 1). Eleven were from the United States, two from Canada, and one each from the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. Fourteen articles applied Markov state-transition models and two used microsimulation models (MISCAN, SimCRC, and CRC-SPIN). All except two stipulated 50 as the starting age for screening asymptomatic adults, usually with a cut-off age of 80. Five-yearly or ten-yearly CTC-screening intervals were most common. Fourteen studies included a comparator of no screening; fourteen studies compared CTC with colonoscopy-based screening. Other comparators included flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS; four studies), sigmoidoscopy (Sig; four studies) and fecal tests (FOBT; four studies, FIT; two studies). Nine studies reported the polyp size referral threshold for diagnostic investigation.

Table 1. Cost-Effectiveness Studies Comparing CTC with Other Potential Screening Modalities for Colorectal Cancer: Peer-Reviewed Papers

Note. Further detail on the cost-effectiveness studies is provided in Supplementary Table 1, which can be viewed online at www.journals.cambridge.org/thc20120×1.

Screening scenarios: 0: NS (no screening). 1: CTC (computed tomographic colonography) 1a: every 5 years without a threshold; 1b: every 5 years with a threshold; 1c: every 10 years without a threshold; 1d: every 10 years with a threshold; 1e: every 15 years without a threshold; 1f: every 15 years with a threshold; 1g: every 20 years without a threshold; 1h: every 20 years with a threshold. 2: COL (colonoscopy) 2a: every 5 years; 2b every 10 years; 2c: every 15 years; 2d every 20 years. 3: FIT (fecal immunochemical testing) 3a: annually. 4: FS (flexible sigmoidoscopy) 4a: every 10 years. 5: Sig (sigmoidoscopy) 5a: every 5 years. 6: FOBT (fecal occult blood test) 6a: annually; 6b: biennially. 7: whole-body CT, 7a: every 10 years. 8: DCBE (double contrast barium enema) 8a: every 5 years. 9: FDNA (fecal DNA testing) 9a: every 3 years.

ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; LYS, life-years saved; LYG, life-years gained; Uptake, refers to uptake of screening test in population; WT, with a referral threshold; WOT, without a referral threshold; EF, extra colonic findings; A US, abdominal ultrasound; i, inexperienced reader; e, experienced reader; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; USD,US dollar; CAD, Canadian dollar; GBP, British Pound; EUR, Euro; NB, monetary net benefit.

CTC test characteristics derived from limited sources. Eight studies applied estimates from the same meta-analysis (Reference Mulhall, Veerappan and Jackson19), four combining these with results from another review (Reference Halligan and Taylor4) to compute average performance estimates for various polyp sizes. Remaining studies based parameters on a combination of trial results (Supplementary Table 4, which can be viewed online at www.journals.cambridge.org/thc2012057). Overall, sensitivity parameter estimates ranged between 80 and 95 percent for CRC detection, 71–92 percent for ≥10 mm polyps, 50–88 percent for 6- to 9-mm polyps, and 29–48 percent for polyps ≤5 mm. Specificity for CRC was 80–95 percent.

Studies varied considerably in estimates of screening uptake. Five studies published pre-2008 assumed uptake of 60–75 percent; four studies published 2008–09, and one in 2010, assumed 100 percent uptake; and five 2009–10 studies assumed uptake of 50–73 percent.

Costs and Effectiveness Measures

Ten studies applied a third-party paper perspective; five took a societal perspective; in one the perspective was not stated. All U.S. studies used Medicare reimbursement schedules and augmented this with data from other sources. For a societal perspective, five North American studies, involving a common group of authors, included indirect costs in the base-case in the form of lost working time and valued this at a median hourly income of 18.62 USD with an estimated 4 hours of lost work time (from Heitman et al.) (Reference Heitman, Manns and Hilsden10). Four further papers included indirect costs within sensitivity analyses. CTC costs ranged from 478 USD to 820 USD in U.S. studies (excluding (Reference Lansdorp-Vogelaar, van Ballegooijen and Zauber15) which set CTC costs relative to colonoscopy). On average, CTC cost estimates were approximately 20 percent lower than colonoscopy costs. Only one study assumed a higher cost for CTC than colonoscopy.

Thirteen studies assessed effectiveness as life-years gained (LYG)/saved (LYS). Two recent papers reported quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), and one used both measures. CTC tended to yield higher effectiveness results compared with all other screening types, except colonoscopy. Only when CTC screening was more frequent than colonoscopy, or where researchers included extra-colonic findings, did CTC emerge as more effective than colonoscopy.

ICER Results

The interpretation of ICERs is aided by specifying thresholds. Earlier studies did not make explicit statements about cost-effectiveness thresholds. In later studies, threshold levels ranged between 50,000 USD and 100,000 USD (United States) and 20,000 GBP to 30,000 GBP (United Kingdom). Overall, CTC was considered cost-effective compared with “no screening”. CTC tended to compare favorably with FS in studies pre-2010; CTC dominated FS and Sig in three studies, and was considered cost-effective compared with FS in another. In two recent studies, CTC was dominated by other current screening strategies including FOBT and FIT.

When comparing CTC to colonoscopy, ICERs varied depending on publication date. Three articles published pre-2006 concluded that colonoscopy was cost-effective compared with CTC, and indeed dominant in two cases. In later studies, results were mixed, but still tended to favor colonoscopy, depending on the cost-effectiveness threshold and the CTC strategy stipulated. In four studies from 2008–09 ICERs favored CTC, although in one study the result was highly cost dependent. In a 2010 UK study, the ICER for colonoscopy versus CTC was 34,002 GBP per QALY, outside the NICE cost-effectiveness threshold. Two other 2010 studies demonstrated colonoscopy dominance over CTC.

Sensitivity Analyses

All studies undertook univariate sensitivity analysis and nine presented results of multivariate sensitivity analyses using Monte Carlo simulations. Key parameters that impinged on CTC cost-effectiveness were: polyp referral threshold, screening uptake, CTC cost and CTC performance characteristics (see Supplementary Table 5, which can be viewed online at www.journals.cambridge.org/thc2012058, for more detail).

Polyp Referral Threshold

Rather than referring all suspected polyps for diagnostic work-up, applying a referral threshold improved CTC cost-effectiveness. Thresholds were varied from none to ≥10 mm, resulting in ICER changes per LYG from 54,540 USD (Reference Pickhardt, Hassan and Laghi23) to 9,277 EUR (Reference Heresbach, Chauvin and Hess-Migliorretti11).

Screening Uptake

Higher uptake for CTC over colonoscopy tended to increase relative cost-effectiveness of CTC. Relative increases from 5 percent (Reference Knudsen, Lansdorp-Vogelaar and Rutter13) to 20 percent (Reference Hassan, Zullo and Laghi8;Reference Sonnenberg, Delco and Bauerfeind26) reversed original cost-effectiveness results to favor CTC over colonoscopy.

CTC Costs

In early studies CTC costs had to be 40–50 percent lower than base-case colonoscopy estimates for CTC to be considered cost-effective compared with colonoscopy (Reference Ladabaum, Song and Fendrick14;Reference Sonnenberg, Delco and Bauerfeind26). In studies from 2008 to 2009, where CTC was considered cost-effective in the base-case analysis, increases in the costs of CTC of 60–74 percent were required to alter the conclusions in favor of colonoscopy (Reference Hassan, Pickhardt and Laghi6;Reference Pickhardt, Hassan, Laghi and Kim22). Two 2010 studies (Reference Knudsen, Lansdorp-Vogelaar and Rutter13;Reference Telford, Levy, Sambrook, Zou and Enns29) necessitated CTC cost decreases of over 50 percent for CTC to become cost-effective compared with colonoscopy.

CTC Performance Characteristics

Modest variations in CTC sensitivity and specificity altered ICERs little; only large variations, particularly for larger lesions, made a sizeable impact. Specifically, changes from 10 percent to 26 percent were necessary to change cost-effectiveness results (Reference Hassan, Pickhardt and Laghi6;Reference Heitman, Manns and Hilsden10;Reference Pickhardt, Hassan, Laghi and Kim22;Reference Regge, Hassan and Pickhardt25;Reference Sonnenberg, Delco and Bauerfeind26;Reference Vijan, Hwang and Inadomi31).

Other Potential Key Parameters: Extra-colonic Findings

Three studies considered extra-colonic findings directly (Reference Hassan, Pickhardt and Laghi6;Reference Hassan, Pickhardt and Laghi7;Reference Pickhardt, Hassan, Laghi and Kim22) and one (Reference Vijan, Hwang and Inadomi31) in a sensitivity analysis. Two studies assumed an average cost of 31 USD (across all screened individuals) for each extra-colonic radiologic workup, and one varied costs depending on screenee characteristics. Two studies (Reference Hassan, Pickhardt and Laghi6;Reference Pickhardt, Hassan, Laghi and Kim22) concluded that detection of findings of major clinical relevance, including AAA and additional malignant neoplasia, resulted in an almost 20 percent increase in life-years gained over the gain from CTC alone, leading to CTC dominance over colonoscopy in one study.

Other Potential Key Parameters: Medical Complications

One study considered cancer risk associated with CTC radiation exposure, estimating that the number of resulting deaths would be less than deaths due to endoscopic complications associated with colonoscopic screening (Reference Hassan, Pickhardt and Laghi6). Seven studies considered CTC-induced bowel perforations and/or complications, and parameter estimates varied between a 0.0005 percent perforation rate (Reference Hassan, Pickhardt and Laghi6;Reference Pickhardt, Hassan, Laghi and Kim22) to a serious complication rate of 0.1 percent (Reference Telford, Levy, Sambrook, Zou and Enns29). No papers reported sensitivity analyses for these parameters.

DISCUSSION

In the European Union, countries provide a mix of national/regional population-based and nonpopulation based screening with the former concentrated in Finland, France, Italy, Poland, and the United Kingdom. No single modality dominates: for example, gFOBT is used in the United Kingdom, France, and Finland; FIT and FS in Italy; and colonoscopy in Poland. This demonstrates the uncertainly that remains around the optimal screening test. The uncertainty means that there is considerable interest in alternative tests, such as CTC, even in settings where screening programs are in place.

This review found considerable heterogeneity regarding CTC cost-effectiveness and, consequently, we focused most attention on identifying parameters that impacted on the ICERs. Nevertheless, some general findings emerged. Compared with no screening, CTC would be considered cost-effective. No clear conclusion emerges when compared with colonoscopy. Colonoscopy dominated CTC in early papers reflecting higher colonoscopy sensitivity and specificity. Over time colonoscopy was less likely to dominate, commensurate with marginally reduced costs and increased sensitivity and specificity for CTC. Nevertheless, CTC cost-effectiveness compared with colonoscopy remains dependent on whether there is a polyp referral threshold and/or extra-colonic findings are included. With regard to FOBT, FIT, and FS, while CTC appears a promising alternative in cost-effectiveness terms, the evidence-base is too limited to draw definite conclusions. Given that FOBT is the most frequently used test in screening programs (Reference Pox and Schmiegel24) future studies should focus on CTC versus FOBT (including newer versions of these tests, such as Hemoccult® SENSA) and the various alternative versions of FIT.

Despite heterogeneity in the evidence, several interesting issues emerged in relation to specific parameters; we discuss these below.

Issues of Over-detection: Referral Thresholds and Extra-colonic Findings

Over-detection and over-treatment are major potential concerns for any cancer screening test/program. For colorectal cancer screening generally, there is currently little evidence on the extent to which this is a problem; the same applies to CTC screening, although it is recognized that screening based on imaging does offer potential for over-detection (Reference Summers28). For CTC, there are two areas in which over-detection could be relevant: detection of polyps which might never have progressed to cancer if left in situ, and detection of extra-colonic lesions which may never have presented clinically.

Referral Thresholds

Over-detection can potentially be addressed—at least in part—by the appropriate choice of the polyp size threshold for referral to diagnostic investigation following CTC. Risk of cancer and high-grade dysplasia in polyps ≤5 mm is less than 1 percent (Reference Matek, Guggenmoos-Holzmann and Demling18). Polyps of 6–9 mm have higher risk, particularly when three or more are present. The Working Group on Virtual Colonoscopy, therefore, recommended a 6- to 9-mm threshold for surveillance or referral to colonoscopy (Reference Zalis, Barish and Choi33). A 6- to 9-mm threshold also makes economic sense. By disregarding low-risk polyps, the number of follow-up procedures required is reduced without perceptibly impinging on clinical effectiveness (Reference Hassan, Pickhardt and Laghi6;Reference Heresbach, Chauvin and Hess-Migliorretti11;Reference Pickhardt, Hassan and Laghi23). These benefits are evident in the cost-effectiveness studies (Reference Hassan, Pickhardt and Laghi6;Reference Lansdorp-Vogelaar, van Ballegooijen and Zauber15;Reference Pickhardt, Hassan, Laghi and Kim22). Some uncertainties over these results remain, however.

Imposition of referral thresholds contradicts current gastroenterology practice of removing all polyps regardless of size (Reference Summers28). In addition, the referral rate at the proposed threshold is still large, and varies between studies. In a recent large multicentre study of asymptomatic individuals (see Supplementary Table 4), follow-up of lesions measuring 5 mm or more with colonoscopy would have resulted in a 17 percent referral rate, with a 6 mm threshold still resulting in a 12 percent referral rate. Future CTC studies—on both effectiveness and cost-effectiveness—should focus more explicitly on polyp over-detection.

Extra-colonic Findings

The few available studies highlight the potentially crucial role extra-colonic findings play in influencing CTC cost-effectiveness (Reference Hassan, Pickhardt and Laghi6;Reference Hassan, Pickhardt and Laghi7;Reference Pickhardt, Hassan, Laghi and Kim22). Uncertainty remains over whether detection of these findings is cost-generating or cost-saving. While early detection of abnormalities may reduce future medical outlays, extensive follow-up after CTC may also result in unnecessary investigations, with associated complications and potential over-treatment.

Two key issues arise when integrating extra-colonic findings into cost-effectiveness analyses. First, their prevalence among the general population remains uncertain. Estimates of the percentage of individuals requiring further work-up ranged between 7 percent and 12 percent (Reference Lefere, Dachman and Gryspeerdt17). However, because RCT evidence is lacking, the degree of over-detection which may arise in a population-based screening program is unknown. Second, estimation of associated costs has only been partially addressed. Studies so far have considered only short-term costs, which are generally modest at 24 USD to 68 USD per patient (Reference Pickhardt, Hanson and Vanness21). Long-term economic costs, including full diagnostic work-up, expert consultations, surgery and treatment, surveillance and follow-up, have not been considered. Costs and benefits to the individuals involved, in terms of impact on quality-of-life for example, are also poorly understood.

Screening Uptake

Based on current evidence (Reference Kanavos and Schurer12), estimates of screening uptake in cost-effectiveness analyses appear artificially high (e.g., studies published 2008–09, with the exception of (Reference Regge, Hassan and Pickhardt25) and (Reference Hassan, Hunink and Laghi5) which specify 70 percent and 50 percent uptake, respectively, assumed 100 percent uptake). The estimates out-strip real-world experience where uptake rarely exceeds 60 percent, and often falls below this (reviewed in a report by the Health Information and Quality Authority [9]). In UK FOBT-based pilot programs, uptake was around 50 percent. Italian uptake estimates vary from 28 percent for FIT to 47 percent for FOBT. Although some endoscopy-based trials report apparently much higher uptake, these often include very high levels of prescreening exclusions.

The potential for increased uptake using CTC as opposed to colonoscopy is predicated on the perceived advantages of lack of sedation and the less invasive nature of the test (Reference Pox and Schmiegel24). Findings on the degree of discomfort experienced by patients and volunteers undergoing colonoscopy and CTC are mixed (Reference van Gelder, Birnie and Florie30;Reference Von Wagner, Knight and Halligan32). Several U.S. studies (see, for example, van Gelder et al.) (Reference van Gelder, Birnie and Florie30) and a UK study (Reference Von Wagner, Knight and Halligan32) have reported an initial preference by individuals for CTC over colonoscopy. However, upon receiving information on all aspects of CTC screening, individuals reversed their preferences from CTC to colonoscopy, with the inability to take biopsies at the time of CTC perceived as a significant disadvantage compared with colonoscopy.

Given that screening uptake appears highly correlated with effectiveness as measured by LYG, improving accuracy of uptake estimates should be a key objective for future studies. More emphasis should be placed on exploring asymptomatic individuals’ views, preferences and experiences of fecal tests and FS compared with CTC.

Effectiveness and Test Performance

A major limitation of the CTC knowledge-base is a lack of evidence on efficacy and effectiveness of CTC screening in reducing colorectal cancer mortality in the population. Current evidence on effectiveness comes mainly from cross-sectional studies on test performance characteristics. Although cost-effectiveness was generally insensitive to small/modest changes in CTC performance characteristics, estimates derived from a limited number of sources, mainly the meta-analysis by Mulhall et al. (Reference Mulhall, Veerappan and Jackson19). This meta-analysis has been criticized by others (Reference Halligan and Taylor4) and studies which used estimates from it tended to find more favorable results for CTC cost-effectiveness. A further difficulty is that many of the studies are of symptomatic patients rather than true screening populations who would, in the main, be asymptomatic and this can lead to biased estimates of test performance. In the cost-effectiveness studies the use of effectiveness measures more representative of an average (screening) population tended to result in CTC not being considered cost-effective compared with relevant alternatives.

Effectiveness measures in the reviewed studies tended to concentrate on sensitivity and specificity. Little attention was given to appropriate measures of quality-of-life. Utility measures applied in the studies were generally from a single source (Reference Ness, Holmes, Klein and Dittus20) and related only to the decrease in quality-of-life due to a diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Potential impacts on quality-of-life of screening per se, false-positive and inadequate results, diagnostic colonoscopy, and extra-colonic findings have not been incorporated—in part because such data have not been reported in the literature. Further research is required to better understand the quality-of-life impact of colorectal cancer screening (by CTC and other modalities) across the entire screening process, and future cost-effectiveness analyses should take these into account.

CTC Safety

Cancer risk resulting from CTC radiation exposure has been rarely considered in cost-effectiveness analyses. The absolute lifetime cancer risk using a normal dose and current scanner techniques has been estimated as 0.14 percent for paired CTC scans for a 50-year-old, and approximately half that for a 70-year-old (Reference Brenner and Georgsson1). Doses to the patient are much lower nowadays and expected to reduce further. Nonetheless, the risk is real and screening age-groups and intervals should take this into account.

Bowel preparation for CTC involves inflating the colon with either room air or CO2, inducing a risk of perforation. Estimates of the frequency of perforation vary. UK and Israeli perforation estimates range between 0.03 percent (Reference Sosna, Blachar and Amitai27) and 0.059 percent (Reference Burling, Halligan, Slater, Noakes and Taylor2). One cost-effectiveness study (Reference Lee, Muston and Sweet16) used the estimate of 0.059 percent, while the others used lower estimates, potentially conferring an artificial advantage on CTC. Greater consideration of the risks of CTC is important, particularly when comparing CTC with inherently “low-risk” tests, such as FOBT and FIT.

Costs

Cost data in the reviewed papers were not transparently reported and costs and quantities were not reported separately. This echoes findings elsewhere in the cost-effectiveness literature and may be, partially, a consequence of reporting restrictions and constraints on article length. Consequently, it is difficult to ascertain whether the lack of sensitivity to cost in many of the cost-effectiveness studies was true or a result of which costs were included/excluded. Our ability to compare ICERs across studies was also constrained.

Only around half of the studies incorporated indirect costs and those which did considered a limited range of costs (mainly participant time). Although they were not an important driver of ICERs in this review, indirect costs possess the potential to influence cost-effectiveness, particularly in relation to follow-up of extra-colonic findings and when comparing hospital/clinic-based tests (such as CTC) with home-based tests (like FOBT and FIT). More precise estimation of participants’ time associated with different screening tests, and other participant-borne costs (such as travel and out-of-pocket expenditure), remains a key task for future studies.

Population Screening

Cost-effectiveness studies that projected findings to a population-level (Reference Hassan, Zullo and Laghi8;Reference Ladabaum, Song and Fendrick14;Reference Pickhardt, Hassan and Laghi23) generally indicated that CTC screening would reduce the number of colonoscopies required, while transferring the burden from endoscopic services to radiologic services, so there would be no decrease in resource use overall. However, all studies indicated that CTC screening would not currently be considered a replacement for screening by colonoscopy or FOBT, but a complementary strategy which could potentially increase overall screening uptake. Even if sufficient infrastructure was available, critical issues remain to be resolved, including whether CTC can: demonstrate high consistency and sensitivity across a range of settings; overcome issues with regard to optimal technological characteristics of the technique particularly in relation to referral size threshold; overcome procedure costs, and surmount risks from radiation exposure. More general issues pertaining to colorectal cancer screening, including training, monitoring, minimizing adverse effects, and the timeliness of further investigations, are also relevant to any proposed large-scale CTC screening program.

CONCLUSION

Evidence on the cost-effectiveness of CTC screening is heterogeneous. CTC appears cost-effective compared with no screening and is cost-effective compared with fecal tests and FS in some studies. Cost-effectiveness compared with colonoscopy is uncertain. The heterogeneity is due largely to between-study differences in comparators and parameter values.

Future cost-effectiveness analyses should model clinically appropriate CTC screening scenarios, with 10-yearly screening intervals and a polyp referral threshold of 6 mm or 10 mm; make more realistic assumptions regarding screening uptake; and include a range of indirect costs. They should focus on comparing CTC to fecal tests (especially newer FOBTs and the various alternative FITs) and FS, the tests most commonly used in screening programs. Comprehensive multivariate sensitivity analyses are required to fully understand how results depend on parameter estimates. Finally, the long-term costs and benefits emanating from detection of extra-colonic findings require more serious consideration.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Table 1: www.journals.cambridge.org/thc2012054

Supplementary Table 2: www.journals.cambridge.org/thc2012055

Supplementary Table 3: www.journals.cambridge.org/thc2012056

Supplementary Table 4: www.journals.cambridge.org/thc2012057

Supplementary Table 5: www.journals.cambridge.org/thc2012058

CONTACT INFORMATION

Dr. Paul Hanly, PhD, Health Economist, National Cancer Registry Ireland, Cork, Ireland.

Mairead Skally, MSc, Researcher, National Cancer Registry Ireland, Cork, Ireland.

Prof. Helen Fenlon, MB BCh BAO, FFR, FRCR, Associate Clinical Professor, University College Dublin, Department of Radiology, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital & BreastCheck, Dublin, Ireland.

Dr. Linda Sharp, PhD, Head of Research Department, National Cancer Registry Ireland, Cork, Ireland.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Paul Hanly, Mairead Skally, and Linda Sharp report their institute has received a grant and travel support from Health Research Board Ireland. Helen Fenlon reports she has no potential conflicts of interest.