Medicare is the federal health insurance program for U.S. citizens aged 65 years and older and certain people with disabilities under the age of 65 years. As the largest healthcare payer in the United States, Medicare accounted for approximately 20 percent of national health spending in 2013 (1). Medicare pays for the health care of approximately 50 million citizens, at a cost of more than $555 billion (2). For prescription drugs, coverage decisions are made by private plans that contract with the program (Medicare Part D). For other technologies and interventions, including medical devices, surgeries, medical procedures, and inpatient and physician administered drugs, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issues coverage policy through one of two mechanisms: national coverage determinations (NCDs) or local coverage determinations (LCDs). CMS typically reserves NCDs for a select subset of ‘big ticket’ interventions likely to have a significant impact on costs or quality of care, or those which are associated with safety concerns. NCDs represent roughly 10 percent of all CMS coverage determinations (3). For most technologies, coverage is determined at the regional, rather than the national, level by twelve Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs), private insurance companies that contract with the Federal government to administer claims for the program (4). Because MACs must comply with NCDs, a national noncoverage determination issued through an NCD is binding on all regions. On the other hand, a positive national coverage determination issued through an NCD means that all eligible Medicare beneficiaries (as defined by the parameters of the NCD) will have access to the intervention regardless of the residential location. NCDs, therefore, can have profound implications for beneficiaries’ access to medical advances, for program costs, and for product manufacturers’ revenues.

A stated goal of the Affordable Care Act is to reduce the growth of healthcare spending while promoting high-value, effective care. While no provisions in the law directly impact NCDs, research shows that when holding constant the level of supporting evidence, coverage determinations made in NCDs have become increasingly restrictive (Reference Chambers, Chenoweth and Cangelosi5). The objective of this study was to evaluate NCDs issued from 1999 to 2013 to identify key trends, and to discuss implications for future CMS policy. This research builds on two previously published NCD reviews, which studied NCDs through 2003 and 2007, respectively (Reference Neumann, Divi and Beinfeld6;Reference Neumann, Kamae and Palmer7).

METHODS

We used the Tufts Medical Center National Coverage Determination Database maintained by researchers at the Center for the Evaluation of Value and Risk in Health at Tufts Medical Center for this research (8). This database includes multiple variables related to NCDs, including those pertaining to the technology, the decision-making process, the review by CMS of the supporting evidence, and the coverage determination outcomes. Information is abstracted from decision memoranda and related documentation, which CMS makes publicly available for each NCD by means of its Web site (9). Two trained reviewers at Tufts Medical Center abstract data independently and clarify discrepancies between them during a consensus meeting. A more detailed description of the database and our data collection protocols is described elsewhere (Reference Neumann, Divi and Beinfeld6;Reference Neumann, Kamae and Palmer7). The database has been widely cited and used previously to evaluate trends in NCDs, and has contributed to analyses identifying factors correlated with positive coverage and comparing the restrictiveness of Medicare coverage policy with corresponding FDA approval (Reference Chambers, Chenoweth and Cangelosi5;Reference Chambers, Morris, Neumann and Buxton10;Reference Chambers, May and Neumann11).

We examined various characteristics of NCDs in a manner consistent with previous reviews (Reference Neumann, Divi and Beinfeld6;Reference Neumann, Kamae and Palmer7). Intervention type categorizes interventions as: (i) medical devices, for example, implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) for patients with arrhythmias (12); (ii) medical procedures, for example, foot care for diabetic patients (13); (iii) medications, for example, aprepitant for chemotherapy induced nausea (14); (iv) radiologic/diagnostic imaging, for example, positron emission tomography (PET) for various cancers (15); (v) laboratory/diagnostic tests, for example, screening immunoassay fecal-occult blood test for colorectal cancer (16); (vi) health education/behavioral therapies, for example, intensive behavioral therapy for cardiovascular disease (17); (vii) surgeries, for example, lung volume reduction surgery for chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (18); or, (viii) other medical therapies, for example, cardiac rehabilitation for patients recovering from cardiovascular events (19).

Condition type categorizes the nature of conditions placed on coverage decisions: (i) coverage restricted to certain population subgroups, for example, patients that suffer from a particular comorbidity; (ii) coverage restricted to patients receiving care in specific care settings, for example, restricted to treatment in centers with a threshold volume of transplants per year; (iii) treatment restrictions applied to coverage decision, for example, patients who have failed first-line therapy; or (iv) restricted to patients enrolled in an approved coverage with evidence development (CED) study.

Evidence strength categorizes the strength of supporting evidence in favor of the technology based on our assignment using the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force classification scheme (20). We categorized the strength of supporting evidence in favor of the technology as: (i) “good” if it included consistent results from well designed and conducted studies in representative populations; (ii) “fair” if evidence was sufficient to determine the effect on health outcomes but its strength was limited by the number, quality, or consistency of individual studies; (iii) or, “poor” if evidence was insufficient to assess the effects on health outcomes due to the limited number or power of studies, flaws in their design or conduct, or lack of information on important health outcomes.

Evidence limitations captures the manner in which CMS critiques the evidence base, and categorizes evidence shortcomings as those pertaining to: (i) the number of studies available; (ii) the number of patients studied; (iii) the length of patient follow-up; (iv) the lack of relevant outcomes; (v) the lack of applicability of study findings to the Medicare population; (vi) the lack of control groups; (vii) whether the study fails to address variables that may have affected results; (viii) the lack of study blinding; (ix) high dropout rates; and, (x) the lack of randomization.

Time to decision reports the time between the date of CMS's formal acceptance to open an NCD and the date the final decision memorandum was released and posted. For this variable, we consider NCDs issued since enactment of the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) in 2003, which legislated maximum NCD review times—6 month review time, or 9 months if CMS sought advice from the Medicare Evidence Development and Coverage Advisory Committee (MEDCAC) or commissioned a health technology assessment (HTA) to support their decision. Previous research showed that review times were reduced following enactment of the MMA (years studied 1999–2007) (Reference Neumann, Kamae and Palmer7).

For the variables, MEDCAC and HTA, we recorded whether CMS referred the decision to the MEDCAC or commissioned an HTA to support their decision.

We also included variables not considered in the previous studies evaluating NCDs (Reference Neumann, Divi and Beinfeld6;Reference Neumann, Kamae and Palmer7). In Reconsideration we categorized whether the NCD was novel, or a reconsideration of an existing NCD. CMS typically reconsiders an existing NCD when substantial new evidence becomes available. The reconsideration may be triggered either by a request from an external party, i.e., from a manufacturer or a medical or professional society or organization, or, CMS may choose to open the reconsideration themselves in the absence of an external request. In Prevention-level we categorized the nature of a technology's benefit as primary, secondary, or tertiary prevention. Primary prevention refers to interventions that prevent the onset of disease by means of risk reduction, for example, smoking cessation counseling (21). Secondary preventive interventions are used after disease has occurred, but before the patient shows symptoms, for example, intensive behavioral therapy for cardiovascular disease (17). Tertiary preventive interventions are used to treat disease after symptoms are present, for example, autologous cellular immunotherapy treatment of metastatic prostate cancer (22).

We excluded incomplete NCDs, as well as those pertaining to treatment facilities, minor coding changes, or language changes. We analyzed trends using Microsoft Excel and SAS version 9.3. For categorical variables, we evaluated longitudinal trends (i.e., 1999–2013, unless noted) using the Cochran-Armitage trend test, which is a test for trend in binomial proportions and is appropriate when one variable is ordinal in nature, and the other has two levels.

For Time to decision we used linear regression to evaluate the correlation between NCD year and the time it took CMS to perform the national coverage analysis. We considered p-values below the 5 percent level to be statistically significant and values between 5 percent and 10 percent to be weakly significant.

RESULTS

One hundred and seventy-three unique national coverage determinations were included in our analysis. Seven (4 percent) resulted in full coverage of the intervention, 123 (71 percent) in coverage of the intervention for Medicare beneficiaries meeting particular conditions, 27 (16 percent) were completely not covered, and for 16 (9 percent) CMS deferred coverage to regional MACs. We identified several key trends (Table 1).

Table 1. National Coverage Determinations from 1999 Through 2013, Statistical Trend Findings

*Downward trend; **Upward trend; † Annual statistical trends for “Prevention level” and “Quality of evidence” required consolidation of outcomes to perform Cochran-Armitage test. “Prevention level” consolidated Primary and Secondary Prevention; “Quality of evidence” consolidated Good and Fair quality evidence; ‡ CMS applied first CED policy in 2004.

For categorical variables we evaluated longitudinal trends (i.e., 1999–2013, unless noted) using Cochran-Armitage trend tests. For Time to Decision we used linear regression to examine national coverage determinations made post Medicare Modernization Act, 2003–2013.

p-values pertain to the statistical significance of longitudinal trends (i.e., 1999–2013, unless noted)

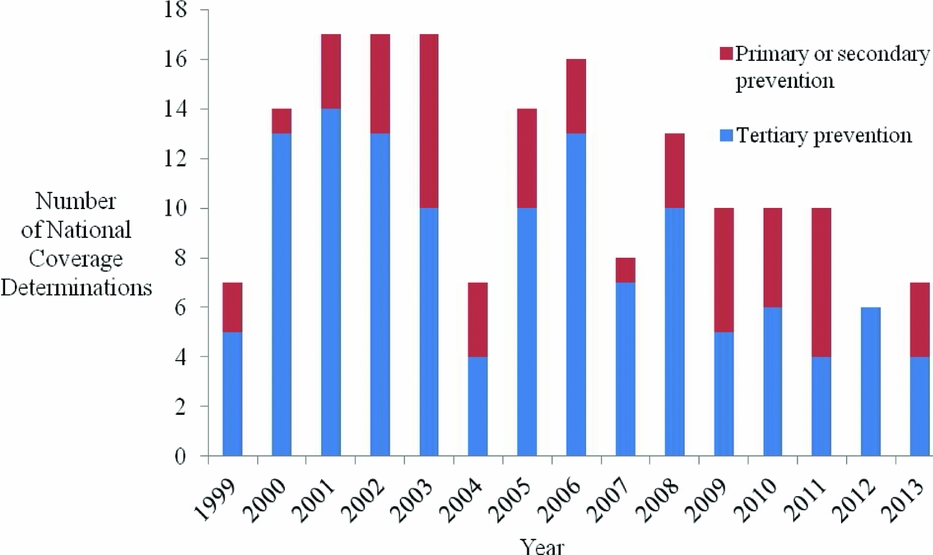

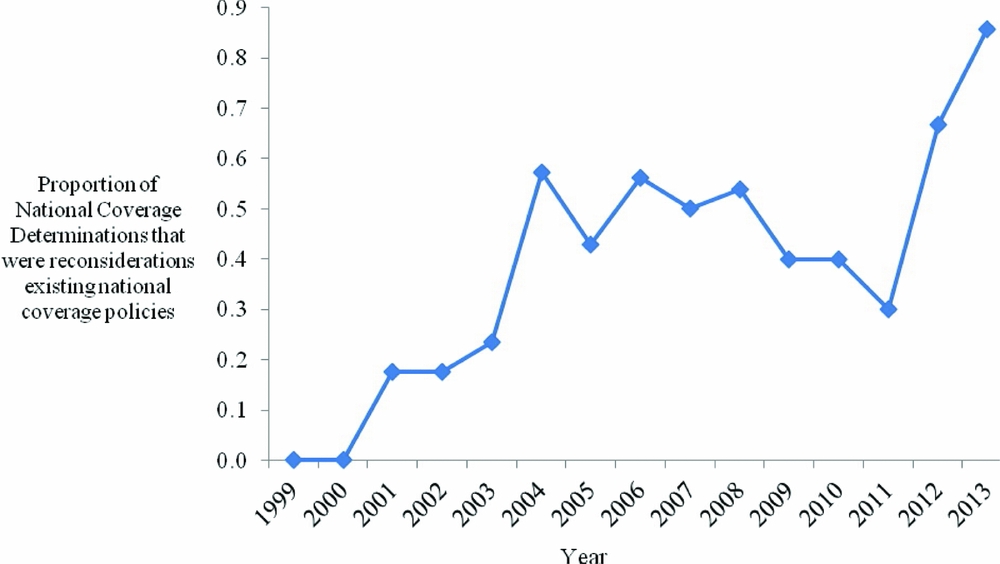

First, CMS increasingly uses NCDs to evaluate health education/behavioral therapy interventions (p = .051), and diagnostic imaging (p = .033). Second, with respect to limitations placed on coverage, CMS less often restricts coverage to certain population subgroups (p < .001), and, since 2004, CMS has increasingly applied CED policies (p < .001). Third, CMS increasingly cites a lack of relevant outcomes (p = .019), the lack of applicability of study results to the Medicare population (p < .001), and the failure of studies to address factors that may affect results (p = .013), as limitations of the supporting evidence. CMS less frequently cites a limited number of studies reviewed (p < .001) as a limitation of the supporting evidence. Fourth, since the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) in 2003, NCD review times have declined (p = .061). Fifth, an increasing proportion of NCDs are reconsiderations of existing national coverage policies (p < .001) (Figure 1). Sixth, interventions for primary or secondary prevention, as opposed to treatment (tertiary prevention), are increasingly subject to NCDs (p = .072) (Figure 2). Over the time period studied, we did not identify a trend in the quality of evidence supporting NCDs, for CMS's use of the MEDCAC in NCDs, nor for how often CMS commissioned a HTA.

Figure 1. Proportion of national coverage determinations that were reconsiderations of existing national coverage policies by year.

Figure 2. Number of national coverage determinations by year, stratified by prevention stage.

DISCUSSION

Our study identified several trends that provide a window through which to view the changing Medicare program. We found that the type of intervention considered in NCDs has changed, with an increased number pertaining to diagnostic imaging and health education/behavioral therapies. The increased use of national coverage policies for diagnostic imaging is presumably in response to the increased usage that has accompanied advancements in the field. Between 2000 and 2006, Medicare spending on diagnostic imaging doubled to approximately $14 billion (23;24). Diagnostic imaging represents roughly 30 percent of all NCDs, with roughly 40 percent of the diagnostic imaging NCDs (seven of eighteen NCDs) constituting reconsiderations of previous policies. CMS has issued NCDs for PET across a broad range of indications and patient subgroups, including informing initial and subsequent treatment strategy for various cancers, evaluation of myocardial perfusion, and diagnosing of dementia and Alzheimer's disease.

CMS's more frequent review of health education/behavioral therapies, for example, counseling and/or behavioral therapy for tobacco use, obesity, sexually transmitted infections, and cardiovascular disease (25–28), is consistent with our finding that an increasing proportion of NCDs pertain to preventive care. This development is consistent with broader trends in U.S. health care. For example, the Affordable Care Act created the National Prevention Council to promote, coordinate, and align federal health and prevention efforts, and created the Prevention and Public Health Fund to sustain the necessary infrastructure and funds for the delivery of preventive care (29). Furthermore, as of 2011, the law required removal of copayments for preventive services recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (services with an “A” or “B” rating), the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, and the Health Resources and Services Administration (29). The shift toward prevention in NCDs indicates that Medicare is evolving from a program that simply pays treatment claims, to one that aims to keep beneficiaries healthy. This evolution is consistent with trends among private health insurers and other government agencies (Reference Faust and Menzel30). While research has shown that not all preventive services are cost-saving or even cost-effective, many are (Reference Cohen, Neumann and Weinstein31), and the judicious addition of preventive services should lead to a healthier Medicare population and a program that receives better value for its spending (Reference Chambers, Cangelosi and Neumann32).

We found that the nature of the conditions CMS places on coverage has changed over time. CMS is less often restricting coverage to patient subgroups, but is more often applying CED policies in NCDs. CMS's increasing application of CED is consistent with policies implemented in other countries to cover technology contingent on the collection of additional effectiveness data (Reference Hutton, Trueman and Henshall33;Reference Neumann, Chambers, Simon and Meckley34). These policies are a form of “risk-sharing,” that is, reimbursement linked to demonstrated effectiveness, often imposed in reaction to a health technology assessment agency judging that the technology is not sufficiently cost-effective. Risk-sharing schemes have been implemented in many countries, including the United Kingdom, Australia, and Italy (Reference Sudlow and Counsell35–Reference O’Malley, Selby and Jordan37). As CMS does not consider cost-effectiveness for treatments, an important distinction for Medicare is that CMS-implemented CED policies are designed to establish treatment effectiveness, not cost-effectiveness (Reference Chambers, Neumann and Buxton38).

CMS's increasing application of CED in NCDs has uncertain consequences. Advocates for the policy have argued that CED promotes innovation by providing market access to promising technology despite an immature evidence base (Reference Daniel, Rubens and McClellan39). Opponents, however, have noted that CED can be restrictive, and that it can slow access to and adoption of innovative technology by raising the evidentiary hurdle for coverage (Reference Tunis, Berenson, Phurrough and Mohr40). The concern is understandable. Data collection can continue for years before the coverage policy is revised, and in the first 20 CED cases, only in two instances (lung volume reduction surgery for late-stage emphysema [2003], and PET for cancer [2009]) was data collected used to revise coverage policy. In many instances, despite CMS applying a CED policy, data collection efforts were not designed, funded, or implemented (Reference Tunis, Berenson, Phurrough and Mohr40). Nonetheless, in November 2014, CMS issued updated guidance on CED that indicated the Agency's intention to retain the approach as an integral part of coverage policy (41). Because CED policies are administratively and economically burdensome, it seems that, without a fundamental change in the role CMS plays in funding CED policies, it is unlikely that the Agency has the necessary resources and infrastructure to substantially increase their number. Arguably, CMS should play a more active role in funding CED studies, or contributing to manufacturer initiatives, as having access to relevant and timely evidence is necessary for evidence-informed coverage policy. More probably, CMS will reserve CED for highly promising technologies for which additional data collection seems likely to substantially reduce uncertainty.

We found that CMS is increasingly citing lack of relevant outcomes and the lack of applicability of study results to the Medicare population as evidence limitations (Reference Neumann and Tunis42). This is consistent with a broader trend toward greater sophistication in evidence generation and evaluation. For example, the Affordable Care Act established the PCORI to generate and disseminate comparative effectiveness evidence and to promote “patient-centered” outcomes such as health related quality of life and clinical endpoints as opposed to surrogate endpoints (43).

CMS appears to be increasingly scrutinizing the evidence base to adequately demonstrate that covered interventions improve relevant health outcomes, for example, functional status, disability, health related quality of life, major clinical events, and death. The trend reflects CMS's increasingly aggressive efforts to balance an intervention's risks and benefits, and costs. Our earlier research has indicated that when controlling for factors such as the quality of the underlying evidence and the availability of alternatives, NCDs have become more restrictive over time (Reference Chambers, Chenoweth and Cangelosi5;Reference Chambers, Morris, Neumann and Buxton10).

We found that an increasing proportion of NCDs are reconsiderations of existing national coverage policies. While CMS has on occasion initiated a national coverage analysis immediately following an intervention's FDA approval, the Program often chooses to evaluate interventions that have been available for several years. This is in contrast to agencies such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK, or the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) in Australia, which act as “gatekeepers” to new technology, ruling on technologies before their entry into the healthcare system, and often throughout the product's lifecycle (44;45). CMS typically reconsiders an existing NCD following the availability of new clinical evidence, with the coverage analysis initiated after a manufacturer's request (e.g., electrical bioimpedance for cardiac output monitoring initiated in 2006), or by CMS themselves (e.g., implantable defibrillators initiated in 2004) (46;47).

LOOKING FORWARD

The appropriate role for NCDs continues to be debated. Proponents for more NCDs highlight that Medicare's local coverage process leads to variation in access (Reference Foote, Wholey, Rockwood and Halpern48). The regional MACs vary in size and available resources, as well as in their use of evidence and the timeliness of their decisions (Reference Foote, Halpern and Wholey49). Their independent nature inevitably leads to variability in access, for example, a biologic paid for in Massachusetts may not necessarily be covered in New York (Reference Saret, Cangelosi, Chambers, Cohen and Neumann50). A 2014 report by the Office of Inspector General reported that LCDs limited coverage of medical technology differently across states and regions (51). The report also found wide variation in the application of LCDs between regions, with LCDs affecting coverage of more than 50 percent of interventions in some states, and as few as 5 percent in others. When a regional MAC has not issued an LCD, coverage is adjudicated on a case-by-case basis. There is a longstanding effort to increase consistency in Medicare coverage policy across the United States, and consolidation of Medicare contractors is ongoing; currently, there are twelve MACs, with CMS planning to reduce the number to ten (52–55).

While NCDs offer an opportunity to reduce variation and in turn equalize access and promote program efficiency, some argue that regional variation is healthy, because national policy, with its cumbersome process, can inhibit diffusion of innovative technology (Reference Bailey56). Within this view, regional variation is fundamental to the development of clinical knowledge and should be embraced as a mechanism to generate new evidence on clinical effectiveness. Nevertheless, coverage policy not informed by evidence and that does not generate additional evidence to inform future decision making has questionable value and may well be unethical. While these debates will continue, despite managing to reduce NCD review times, it appears that CMS lacks the capacity to issue NCDs with substantially greater frequency, meaning that NCDs will likely continue to focus on big-ticket items and regional MACs will be relied upon to issue the majority of coverage decisions.

CONCLUSIONS

National coverage determinations have been, and will likely remain, important avenues for U.S. Medicare coverage. Since 1999, CMS's use of NCDs has evolved. This evolution is indicative of broader changes in the Medicare program, with a greater focus on prevention, attempts to reduce inappropriate use of medical technology, increased scrutiny of the supporting evidence base, and more frequent application of CED policies.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No external funding was received for this research