The tadhkira (biographical anthology; plural tadhākir; Pers: tazkirih, tazkirih-hā) of Persian poets has proved to be a valuable resource for charting a vast array of literary, social, cultural, and political phenomena across the early modern and modern Persianate world. Scholars have relied on tadhkiras of Persian poets to assess developments in poetic style and literary reception and used them to reconstruct communities, social networks, cultural memory, and (trans)national historiographies.Footnote 1 Fewer studies have utilized tadhkiras to ask questions about the larger processes that governed the production, proliferation, and circulation of the genre as a whole. Achieving such an aim requires pursuing elements of a macroanalytical approach based on “the systematic examination of data [and] quantifiable methodology,” which tadhkiras are well equipped to provide.Footnote 2 A wealth of quantifiable data, such as the date and place of production, intertextual citations, and biographical information about authors, allows individual tadhkiras to be recorded, cataloged, and mapped in a systematic way. This method allows for a stronger basis to make claims about a collective genre and its attributes than may be gleaned by selective close readings of individual works. It does not mean the pursuit of a macroanalytical approach is akin to doing away with the method of close reading altogether, but that the two should be seen as complementary approaches. As Matthew Jockers in Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History notes, “the macroscale perspective should inform our close readings of the individual texts by providing, if nothing else, a fuller sense of the literary-historical milieu in which a given book exists. It is through the application of both approaches that we reach a new and better-informed understanding of the primary materials.”Footnote 3

The word tadhkira comes from the Arabic root dh-k-r meaning “to recall” or “to remember.” At its most fundamental level, a tadhkira may best be described as a prosopographical text seeking to “remember” certain individuals; in doing so the text establishes those individuals as a “class.”Footnote 4 But as one of the most inventive and plentiful categories of texts produced in Islamicate societies, establishing a comprehensive definition of the tadhkira in a way that corrals its multilingualism, differential models of organization, subject matter, and varying authorial impulses can prove elusive. For this reason, this article approaches the large corpus of tadhkiras produced in the 18th and 19th centuries across Iran and South Asia as constituting a transregional library of texts.Footnote 5 Even absent an actual physical and central location housing these texts, relying on the metaphor of a transregional library provides a way to concretize a vast collection of tadhkiras and more adequately assess major trends in their production and circulation across space and time. Approaching these texts as part of a library allows for a shift from locating characteristics meant to define tadhkiras as a singular generic class, identifying elements common to them all, to a focus on their shared processes of production and circulation.

The first section details the makeup of the tadhkira library in the 18th and 19th centuries. It relates how state disintegration and formation, such as the breakup of the Mughal Empire in South Asia and the emergence of the Qajar dynasty in Iran, shaped major trends in tadhkira production. It argues that state disintegration and formation created new climates for tadhkira production and impacted methods of compilation, opportunities for patronage, and authorial motivations in the crafting of new works. In the 18th century, the rising importance in South Asia of poetic networks and noncourt assemblies played the most formative role in reshaping methods and practices of tadhkira production. As Mughal power waned and imperial networks broke down, compilers were further emboldened to record new and contemporary voices of poetry in operation beyond the imperial center. In the 19th century, the greatest factor (re)shaping the composition of the tadhkira library relates to the role played by the Qajar state. The Qajar royal court oversaw and managed tadhkira production as a state enterprise, creating an environment in which tadhkiras produced and circulating within their sovereign lands were valued above all else. In other words, the tadhkira library, with the bulk of texts produced in Qajar lands during this time, was being reconstituted to cohere with state aims. In 19th-century South Asia, tadhkira production was becoming increasingly confined to the courts of successor (and princely) states—the last official locations recognizing and utilizing Persian as a primary marker of elite literary status—but with less definitive results. The overall impact of both of these developments was the reconstruction of the tadhkira library in the 19th century around isolated pockets of state interest and power. Other plausible explanations for the rise in production of tadhkiras by Persian poets in the 19th century, such as the higher survivability rate of manuscripts in the 19th century or the proliferation of print technologies lowering the barriers to production and circulation of texts, are not borne out by the evidence. In the first case, tadhkira authors across the centuries were adamant about relying on the corpus of earlier produced texts in the composition of their own works, thus if an earlier period produced a greater volume of texts (whether those works are extant or nonextant today), tadhkira authors would have made note. In the second instance, print technologies in the 19th century, except for a few isolated instances that will be discussed, simply did not factor into the production or circulation of tadhkiras in the 19th century in any significant manner.

The second section turns to the intertextual relationships between tadhkiras by mapping their citations and highlights some of the methodological opportunities of this approach, such as the way citations can help explain how different authors viewed and accessed the tadhkira library across space and time.

The systematic assessment of the transregional library of tadhkiras for any time period requires quantifiable data that can be mapped and analyzed. The evidence used for this article comes from my own database of tadhkiras of Persian poets produced between the years 1200 and 1900. The database was constructed through the use of secondary sources (Ahmad Gulchin-i Maʿani's two-volume History of Persian Tadhkiras, Sayyid ʿAlirida Naqavi's Persian Tadhkira Writing in India and Pakistan, and C. A. Storey's Persian Literature: A Bio-Bibliographical Survey); manuscript catalogues (Charles Rieu's Catalogue of the Persian Manuscripts in the British Museum and Wladimir Ivanow's Concise Descriptive Catalogue of the Persian Manuscripts in the Collections of the Asiatic Society of Bengal); and individual tadhkiras appearing in manuscript, lithograph, and print.Footnote 6 In order for a text to be included in this database, it had to meet certain criteria. First, the text needed to appear in Persian and focus primarily on poets writing in Persian. Thus, tadhkiras written about Persian poets in another language (e.g., Urdu), tadhkiras in which the primary focus was non-poets, and tadhkiras primarily dedicated to non-Persian-writing poets (e.g., Urdu, Turkish, Arabic), even if the text itself appeared in Persian, were excluded. Second, each text (whether still extant or not) needed to have a recognizable title. Finally, each text needed to have either a reliable place or time of composition. One hundred eighty-eight texts met the above criteria, but only 144 had both reliable temporal and geographic data. It is these 144 texts that composed the set of tadhkiras of Persian poets discussed in this article.Footnote 7

There are certainly limits to pursuing a macroanalytical approach solely devoted to the tadhkiras of Persian poets defined by the above criteria. The reliance on quantitative analysis can often militate against more faithfully situating a text in the many worlds of its creation. Tadhkiras were not produced in an environment where little else mattered save their relationship to other tadhkiras, but were instead part of a large, multifaceted, and multilingual world of histories, poetry collections, dictionaries, and other compendia. Likewise, tadhkira authors were not solely defined by their tadhkira writing, but also by their social and political experiences as poets, courtiers, bureaucrats, and secretaries. A macroanalytical approach cannot always account for these many nuances, as authors and texts are condensed to single data points to be counted as statistics, plotted on graphs, and geocoded on maps. Nonetheless, although this approach may too highly value the forest for the trees and too readily rely on a manufactured world limited to tadhkiras of Persian poets, the benefits to understanding how tadhkiras and their authors relate to one another across space and time, how tadhkira production intersects with larger social and political trends, and the presentation of new methodological opportunities for exploring transregional trends in textual production and circulation, outweigh these drawbacks.

THE COMPOSITION OF THE TADHKIRA LIBRARY IN THE 18TH AND 19TH CENTURIES

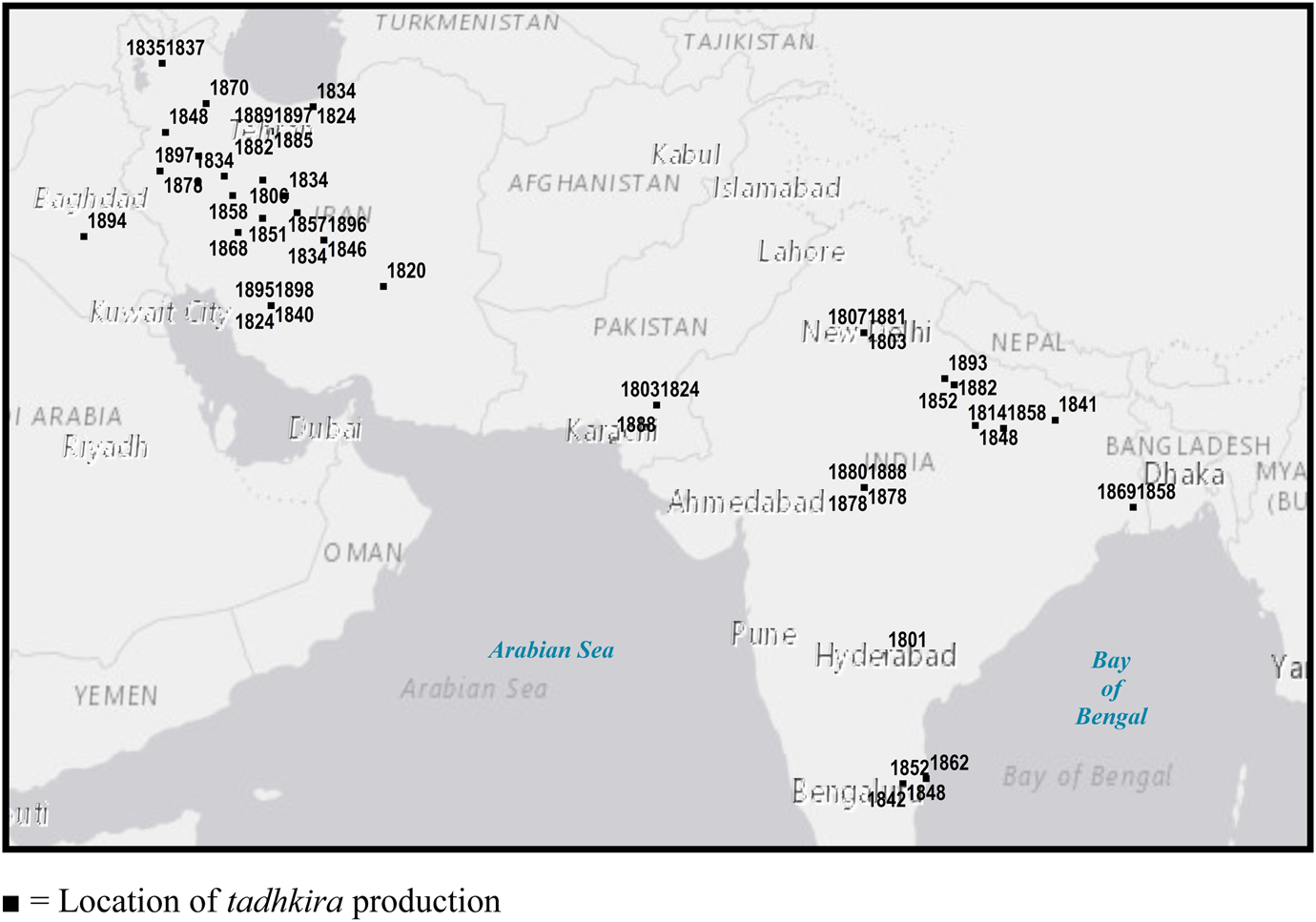

The 18th and 19th centuries witnessed an explosion of tadhkiras of Persian poets (see Figure 1). Of the 144 tadhkiras in my possession produced between the years 1200 and 1900, 123 (85%) were produced in the period from 1700 to 1900. Figure 2 reflects that the periods from 1725 to 1775 and 1800 to 1850 stand out as times of high tadhkira production and the expansion of the tadhkira library. To portray the geographic distribution of tadhkira production during this time, Maps 1 and 2 depict the locations of tadhkiras produced in the 18th and 19th centuries, respectively.

FIGURE 1. Tadhkira Production by Century, 1200–1900

FIGURE 2. Tadhkira Production in Twenty-Five Year Increments, 1200–1900

MAP 1. Locations of Tadhkira Production in the 18th Century

MAP 2. Locations of Tadhkira Production in the 19th Century

THE 18TH CENTURY

The breakup of the Mughal (1526–1857) and Safavid (1501–1722) Empires, the formation of successor states in South Asia, and the continued flourishing of poetic assemblies all served as fertile ground for creating opportunities and inspiring increased tadhkira production from 1725 to 1775, with steady continuation over the following twenty-five years. Poetic assemblies and networks operating outside the direct control of courts served as a major venue for tadhkira production in South Asia during this time. Of course, Persian literary networks and assemblies (sing. majlis) featured heavily outside of courtly domains and imperial control prior to the 18th century.Footnote 8 The sprawling networks of Mughal bureaucracy and the significance accorded to the Persian language as a marker of elite intellectual and literary status nurtured an active poetic culture in places like Lucknow, Agra, Lahore, and the Deccan as well as other cities and provinces. As Purnima Dhavan notes, already by the early decades of the 17th century, most Persian learners could be found “not in the rarified inner circle of the imperial court, but in much more eclectic settings all over the province and cities of the emperor.”Footnote 9

The political shocks of the 18th century, such as Nadir Shah's sacking of Delhi in 1739 and the weakening of the Mughal court, increased the importance of non-court-affiliated poetic assemblies and networks for motivating tadhkira compilation. As complex patronage networks began to break down and the rigid social system of the Mughals loosened, literati and artists left Delhi for other regional centers.Footnote 10 As the poet and tadhkira writer Muhammad Qiyam al-Din “Qaʾim” Chandpuri (d. ca. 1790) described it, “in these days, due to the decay of empire, the string connecting imperial servants broke apart and everyone—like pearls—fell to the ground in humiliation, turning every which way” such that “willing or not, they preferred emigrating elsewhere to staying put [in Delhi].”Footnote 11

Nonetheless, Delhi remained an important center for the arts, including the compilation of tadhkiras, during the 18th century. Several tadhkiras emerged from assemblies and in response to poetic conversations there, such as Mir ʿUzmat Allah “Bikhabar” Bilgrami's Safinih-yi Bikhabar (1728–29) and Mir Husayn Dust Muradabadi's Tazkirih-yi Husayni (1749–50).Footnote 12 Ghulam “Mushafi” Hamdani (d. ca. 1824–25), whose own house in Delhi served as a meeting place for poets, likewise gained inspiration for his tadhkira during a poetic assembly. The famed poet and intellectual Mirza Muhammad Hasan “Qatil” (d. ca. 1822) showed Mushafi a notebook on the poetry and prose of contemporary poets and requested he compose a tadhkira based on its contents.Footnote 13 The result was ʿAqd-i Surayya (Delhi, 1784–85), which focused on the lives of poets in 18th-century South Asia. Toward the end of the century, a similar occurrence played out concerning the compilation of Makhzan al-Gharaʾib (Delhi, 1803–04). When the author Shaykh Aha ʿAli Hashimi sought to collate the verses he collected over the years into a simple notebook, Mirza Qatil once again directed his student to compile instead an alphabetized tadhkira.Footnote 14 This text, however, was more comprehensive than Mushafi's work of a quarter-century earlier: Makhzan al-Gharaʾib included notices of upwards of 3,000 ancient and later poets. Elsewhere, the role of poetic assemblies and networks in galvanizing tadhkira production was equally in play, as seen in the case of Qudratallah “Shawq” Gupamavi's Takmilat al-Shuʿaraʾ Jam-i Jamshid (ca. 1784–85) in Rampur. Having completed several years earlier a general history of rulers and dynasties up to the late 18th century, he was beseeched by friends to compose a work on the biographies of poets since his previous work was lacking in this regard.Footnote 15

The fracturing of Mughal power not only amplified the importance of urban literary salons and societal gatherings as major venues for poetic production, but also instigated a greater tendency among some of the participants to record their activity, especially outside the imperial center. Shamsur Rahman Faruqi points out that the artistic and cultural achievements of the 18th century in Persian (and Rekhta) literary production can be traced to writers and intellectuals who, no longer bound by what was occurring in Delhi, “evinced a spirit of inquiry and independent thought, and preferred to gather information on their own.”Footnote 16 Just as important as the seeking out of new opportunities was the desire to record newness in poetry and literary culture, a trend already becoming apparent in tadhkira writing in the last quarter of the 17th century. Indicative of this trend are the comments of Muhammad Afzal Sarkhush in the introduction to his Kalimat al-Shuʿaraʾ (Delhi, 1682), which would become one of the most-cited tadhkiras in the 18th century, that “there is little merit in going on copying from the works of each other [i.e., other tadhkira authors] and repeating things … the present age is full of writers who know how to deal with many-coloured images and fresh new concepts, it will not be inopportune to devote oneself to describe their lives and speak about the peculiarities of their poetical discourse.”Footnote 17

The rise of Mughal successor states, like the Asaf Jahi state (1724–1948) at Aurangabad (and Hyderabad) and the Awadh state (1732–1858) at Lucknow, served as emergent venues for Persian littérateurs to garner employment, participate in Persian literary activities, and record new poetic voices in new spaces. In both places, poetic assemblies and networks intersected with patronage prospects to create newfound opportunities for tadhkira authors. In the Deccan, the writer Mir Ghulam ʿAli Azad Bilgrami (d. 1786), himself the author of three tadhkiras of Persian poets (Yad-i Bayda, Allahabad, 1735–36; Sarv-i Azad, Aurangabad, 1752–53; and Khizanih-yi ʿAmirih, Aurangabad, 1762–63) was a crucial figure in this regard. Azad connected a student and the future author of Tazkirih-yi bi-Nazir (Hyderabad, 1758–59) to the Nizami state and also helped the wayward traveler ʿAbd al-Hakim “Hakim” Lahuri conceptualize his biographical anthology Mardum-i Didih (Aurangabad, 1761–62).Footnote 18 The flurry of Persian poetic activity around the environs of the state at Hyderabad was such that it led Azad's contemporary Afdal Bayg Khan Qashqal Aurangabadi to shun compiling a tadhkira on ancient poets and instead focus his Tuhfat al-Shuʿaraʾ (Hyderabad, 1751–52) solely on contemporary poets in the Deccan.Footnote 19

In Lucknow, poetic assemblies and networks played a crucial role in tadhkira production as well, at times intersecting with the Awadhi court. It was at a poetic assembly, for example, that a secretary to the Nawabi rulers, Maharajah Tikit Ray (d. 1800–01), scrutinized Tadhkirat al-Muʿasirin (Agra, 1752) of Hazin Lahiji and asked those present “if there is now someone who can organize a tadhkira in this manner?”Footnote 20 Muhan Laʿl “Anis” obliged by composing his Anis al-Ahibba’ (Lucknow, 1783), focusing on the poetic network and pupils surrounding the famed Luckavi poet and instructor Muhammad Fakhir “Makin” (d. 1825–26). Such an example demonstrates how poetic assemblies not only inspired tadhkira production but also highly valued the recording of poetic networks operating outside of the court. The compilation of Anis al-Ahibba’ was not the only case in which Maharajah Tikit Ray and Makin's poetic network came together to inspire a tadhkira: Tikit Ray also employed one of Makin's students, Bahgavan Das “Hindi,” who composed Hadiqih-yi Hindi (Lucknow, 1785–86) and Safinih-yi Hindi (Lucknow, 1804–05) on Persian poets in South Asia throughout history and during contemporary times.Footnote 21 During this time, tadhkira production at Lucknow was further buttressed by the presence of East India Company (EIC) employees and an exiled Safavid prince, demonstrating the extent the compilation of tadhkiras could benefit from a new influx of patrons. The assistant resident at Lucknow, Richard Johnson, commissioned Lubb-i Lubab (Lucknow, 1780), while the exiled Safavid royal Sultan Muhammad Bahadur Khan Safavi (himself a pensioner of the EIC at Lucknow) commissioned Tazkirih-yi Katib (Lucknow, 1810).Footnote 22 Both texts were primarily selections (sing. muntakhab) of earlier tadhkiras, Valih Daghistani's Riyad al-Shuʿaraʾ (Delhi, 1748) and Makhzan al-Gharaʾib (Delhi, 1803–04), respectively, amended with new entries.Footnote 23 That these two tadhkiras, like the example of Hazin's Tadkhirat al-Muʿasirin noted above, should so directly inspire the production of tadhkiras a few decades later are indicative of the high level of tadhkira circulation in 18th-century South Asia.

THE 19TH CENTURY

In the 19th century, the most significant feature of tadhkira production was its relationship to the activities and aspirations of ruling states and courtly centers. Across Qajar Iran and the courts of Mughal successor or princely states in Arcot, Bhopal, and Lucknow, tadhkiras were commissioned by rulers and written by poets, state functionaries, and members of the royal elite. The high incidence of tadhkira production at courtly centers in Iran and South Asia throughout the 19th century is illustrated in Map 3. The map is calculated to depict the concentration (or density) of tadhkira production according to the temporal and spatial proximity of texts produced there. In Tehran, for example, one sees the highest concentration of production as it was a place that witnessed a significant number of tadhkiras produced during a short period of time. Likewise, other “hot-spots” of tadhkira production can be seen in Bhopal and Arcot. Although this macroanalytical approach displays that the tadhkira production connected to state courts represented the most significant trend in the 19th century, understanding what this reveals about the reconfiguration of the tadhkira library requires one to inspect how the content, production, and compilatory processes of these works may have intersected with state aims and larger trends in Persian literary culture.

MAP 3. Density of Tadhkira Production in the 19th Century

In South Asia, the concentration of tadhkira production at the courts of Mughal successor and princely states demonstrates the continued ability of Persian littérateurs to find outlets for patronage more than a century after the breakup of the Mughal empire. But more importantly, the relationship between the production of tadhkiras of Persian poets and a regional or princely court indicates how the space for the production and reception of the genre was narrowing from the previous century, a function of the changing status of Persian as a literary language on the subcontinent.

Poetic assemblies and networks of poets, at times intersecting with emergent state courts, not only reflected one of the most creative and intellectualized climates for the production of Persian poetry, but also fostered a welcoming atmosphere for authors wishing to record such activity in a tadhkira of Persian poets, as seen in the previous section. By the first decade of the 19th century, however, the literary climate for the production and reception of Persian had shifted significantly. Networks of poetic instruction were shifting away from Persian toward Urdu.Footnote 24 Genres like tadhkiras and poetic topoi like shahr-āshūb (city-disturber), once the primary domain of Persian, increasingly found expression in the ascending vernacular of Rekhtah-Urdu.Footnote 25The political shocks of the previous century had also helped drive Rekhtah's dispersal and transmission to regional centers.Footnote 26 By the early 19th century a Persian-inflected form of Urdu was replacing Persian in elite circles as a new cosmopolitan vernacular,Footnote 27 and the remainder of the 19th century witnessed the gradual displacement of Persian by English, Urdu, and other regional languages.

While the narrative of the decline of Persian in 19th-century South Asia is vastly overstated, the rise of Rekhtah-Urdu as an increasingly acceptable and utilized medium for expression in poetry and prose was unquestionable. This does not mean that Urdu's rise in South Asia occurred in a linear or uniform fashion, or that Persian and Urdu were locked in a struggle for monolingual supremacy, directed by a romanticized, proto-nationalist vision of “one language, one people.”Footnote 28 Quite the contrary: Persian and Urdu were intimately intertwined and continued to both compete with and complement one another across a variety of institutions, court settings, genres, and knowledge systems within a larger multilingual milieu.Footnote 29 But this also should not be taken to mean that the complex interrelationship between the two languages, or their relationships to other languages for that matter, mapped evenly across society. As Francesca Orsini reminds, multilingualism may have been structural to society during the “long 18th-century” in north India, but “it was not uniformly spread.”Footnote 30 Greater attention, she cautions, must be paid to the particular configurations of language use and cultural practices among different groups, places, and genres, rather than falling into the trap of generalizations, such as the phenomenon of vernacularization or a theory of language substitution.Footnote 31

The tadhkira of poets genre is a case in point. By the 1840s, over half of tadhkiras of Urdu poets were composed in a language other than Persian, whereas during the earlier part of the century the situation was entirely reversed, demonstrating that the proliferation of Urdu poetic practice was now being recorded, perhaps naturally so, in Urdu itself.Footnote 32 The literary career of Ghulam “Mushafi” Hamdani, discussed above, further illustrates this trend: he followed up his Persian-language tadhkira of Persian poets, ʿAqd-i Surayya, with a Persian-language tadhkira on Rekhtah/Urdu poets (Tazkirih-yi Hindi, 1794–95) ten years later, and another tadhkira in 1820–21 on both Urdu and Persian poets (Tazkirih-yi Farsi) with nearly all the extracts appearing in Urdu.Footnote 33 The tadhkira of poets genre appearing in Persian was narrowing.

At the same time as tadhkiras in Urdu began to appear with greater frequency and the courts of successor and princely states began to provide increased patronage opportunities for Urdu and other regional languages, these courts nonetheless continued to serve as enclaves for the production of tadhkiras of Persian poets.Footnote 34 Official courts at Lucknow, Arcot, and Hyderabad continued to offer patronage opportunities for Persian littérateurs during the first half of the century, as Persian still maintained relevance as a language of internal administration and of engagement with East India Company residencies.Footnote 35 In the 19th century, the production of tadhkiras of Persian poets increasingly came to be defined by the patronage practices and prerogatives of these courts, amid a shifting literary and linguistic environment. If 18th-century tadhkira production was defined by recording new poetic voices and breaking away from the imperial court at Delhi, the production of tadhkiras of Persian poets in the 19th century was defined by a retreat to the last and most prominent official spaces dedicated to maintaining the Persian language as central to an elite literary culture—the courts of successor and princely states. The results of tadhkira production at these courts, however, were varied.

Tadhkira production under the Nawabs of Arcot (1710–1855) focused primarily on the literary activities of the royal court, poets associated with it, and other littérateurs in the immediate surroundings.Footnote 36 As the political fortunes of the Arcot court—placed under the suzerainty of the British in the early part of the century—waned, cultural and literary activity took on increased importance. Works such as Guldastih-yi Karnatik (Arcot, 1832–33) and its supplement Subh-i Vatan (Arcot, 1842), composed under the name of Nawab Muhammad Ghaus Khan “Aʿzam” (d. 1855), focused on contemporary poets of Carnatic; Isharat-i Binish (Arcot, 1848–49) detailed the lives of poets in attendance at the aforementioned Nawab's exclusive literary society at the court. Other tadhkiras at Arcot, such as Gulzar-i Aʿzam (Arcot, 1852–53), remained invested in cataloging some of the contemporary literary debates at the court, indicating just how closely tadhkira production related to courtly activities in and around Arcot.

In Lucknow, the Awadhi state witnessed the compilation of several tadhkiras in the 1830s and 1840s, but patronage for authors of tadhkiras of Persian poets was proving more difficult. First, local poetic assemblies and networks no longer afforded authors inspiration for the compilation of works or provided the source material for their content. Second, already during the reign of Nawab Shujaʿ al-Dawlah (1753–1775) patronage opportunities become available for Urdu poets at the Awadhi court.Footnote 37 One of the causes leading to increased patronage opportunities for Urdu poets was political, as the new rulers of Awadh were skeptical of the old Persianized Mughal elite. Even though Shujaʿ al-Dawlah was himself a Persianized Mughal and the grandson of a migrant from Iran, Awadhi rulers began to rely on local, non-Persianized groups who were more inclined to bestow patronage on Urdu (rather than Persian) authors.Footnote 38

By the mid-19th century, the Awadh court can only be credited with sponsoring Hadaʾiq al-Shuʿaraʾ (Lucknow, 1846), whose author entered the service of the Nawabs during the reign of Saʿadat ʿAli Khan II (1798–1814) and compiled his work at the court over the course of fifty years.Footnote 39 The other two authors composing works under the auspices of the court during this time only came to Lucknow as a final stop on itinerant travels across South Asia. For example, Rajah Ratan Singh “Zakhmi,” author of Anis al-ʿAshiqin (Lucknow, 1829), traveled throughout South Asia, worked for a time for the EIC in Calcutta, and studied poetry under Mirza Qatil in Delhi before returning to his birthplace of Lucknow to enter the service of the Nawabs and complete his work.Footnote 40 Likewise, Muhammad Rida “Najm” Tabatabaʾi, author of Naghmih-yi ʿAndalib (Lucknow, 1845), left his birthplace of Patna and traveled to Bareilly, Delhi, and Nagpur in pursuit of employment before settling in Lucknow and dedicating his Naghmih-yi ʿAndalib to Nawab Wajid ʿAli Shah (r. 1847–1856).Footnote 41 Both authors’ itinerant travels allowed them to connect with various patrons, employers, and poets across South Asia and provided source material for their works. Their experiences point to how certain patterns of tadhkira compilation, such as the pursuit of regional employment and poetic networks, could still benefit a few intrepid tadhkira authors writing in Persian in the mid-19th century. More importantly, it indicates why a regional court served as a logical final destination for completing a tadhkira of Persian poets: it was here that the elite and imperial stature of Persian was best preserved. It was the location most likely for an author to gain patronage, even if Persian's overall position was becoming increasingly precarious.

As for the Asaf Jahi state, although the court at Hyderabad during the first half of the 19th century continued to attract Persian littérateurs in search of employment, it was not such a hospitable place for tadhkira production. The only tadhkira produced under the auspices of the court was Bustan-i Sukhan (Hyderabad, 1807), a slim volume on the poets who produced poems (in Persian and Urdu) in praise of the Prime Minister Mir ʿAbd al-Qasim.Footnote 42 The only other tadhkira produced at Hyderabad during the 19th century was an equally slim volume on mystical poets composed at the turn of the century, entitled Tazkirih-yi Nawbahar (Hyderabad, 1801–02).Footnote 43Tadhkira production at Hyderabad would confront difficult language politics later in the century: in the 1860s the language at court began to shift from Persian to Urdu; by 1884 the transition took full effect.Footnote 44 No longer benefiting from the presence of communities of Persian poets operating outside of the court, the courts at Lucknow and Hyderabad played a less decisive role in tadhkira production than they had even a quarter-century earlier.

Whereas the previous period witnessed a thriving of tadhkira production outside of courts and a close association with assemblies and networks of poets in South Asia, the first half of the 19th century saw tadhkira production reduced to courtly centers. By the end of the 19th century, the last princely court in South Asia to fully invest itself in the production of tadhkiras of Persian poets was that of Bhopal. As will be discussed in the next section, the approach of the Bhopal court to tadhkira production differed from that of the Arcot court, which chose to focus on the recording of local poets, and from the waning engagement in tadhkira production by the courts at Lucknow and Hyderabad. The princely state of Bhopal sought to produce a series of up-to-date and comprehensive tadhkiras to be distributed in print utilizing a wide range of different tadhkiras as source material.

But it was in Qajar Iran that one witnesses how the transregional library of tadhkiras was reconfigured as a result of state intervention, as can be seen on Map 2. Nowhere was the desire to record the activity and lives of local Persian poets as strong as in Qajar lands. Unlike the situation in South Asia, except perhaps for Arcot, the Qajar court attempted to redefine and localize the Persian tadhkira library with an overwhelming focus on tadhkiras featuring poets and poetic culture located squarely in the court's sovereign domains. From the early days of their reign, the Qajars invested themselves in reconstructing the library of tadhkiras. Serving as patrons, collectors, and composers, the ruling family helped churn the wheels of production and used the Qajar state bureaucracy to commission, collate, and compose works. The result was the transformation of a once decentralized library cutting across regions into one no less vast, but circumscribed to focus squarely on textual production in Qajar lands. Royals, elites, and government officials served as the primary patrons of tadhkira production; the work of poets located in Iran during the Qajar period—often that of the Qajar royal family itself—served as the primary focal point. There is no comparable occurrence to be found on any such scale under the Timurid (1307–1570), Safavid (1501–1722), or Durrani (1747–1826) dynasties. The desire of the Qajars to construct a newly formulated tadhkira library, with their own activities at the center, conforms to larger historiographical trends of the period, such as the writing of dynastic histories and other court-sponsored works.Footnote 45 By the century's end, the Qajars had succeeded in developing a vast network of tadhkiras and remaking the tadhkira library in their image.

Fath ʿAli Shah (r. 1797–1834) was well positioned to reconstruct the library of tadhkiras by drawing on literary networks in Isfahan prior to his reign. His association with Mirza ʿAbd al-Wahhab “Nashat” Isfahani (d. 1828–29), who would later travel with the future shah to Tehran and become a leading littérateur and literary critic at his court, helped establish a crucial link between a burgeoning poetic culture in post-Safavid Isfahan and the new ruling house.Footnote 46 Already by the first decade of his rule, Fath ʿAli Shah's connection with Nashat paid dividends. Zinat al-Madaʾih (Tehran, 1803–04) is an early tadhkira produced at this time praising the new Qajar shah. This particular tadhkira focused on many of the poets who were acquainted with Fath ʿAli Shah in Isfahan and associated with Nashat.Footnote 47Zinat al-Madaʾih, as Naofumi Abe notes, served as the first of many attempts by the Qajar court to utilize tadhkira writing to place itself atop the Persian poetic tradition. The interest and initiative of Fath ʿAli Shah in projects of tadhkira writing was made abundantly clear in the work's preface.Footnote 48 A few years later, Mirza ʿAbd al-Baqi Isfahani (Nashat's cousin) composed Madaʾih-i Husayniyyih (Isfahan, 1807–08) in honor of Fath ʿAli Shah and his prime minister (ṣadr-i aʿẓam). The collection focused on poems praising the latter.Footnote 49

These early tadhkiras bore some of the major hallmarks that would go on to define Qajar intervention in tadhkira composition and an ever-expanding network of production: dedication to a royal or government official, poems in praise of a particular individual, and, in the case of Madaʾih-i Husayniyyih, a primary focus on poets of a particular locale. Although not all tadhkiras of 19th-century Qajar Iran displayed these features, such texts nonetheless helped establish the definitive framework for the composition of tadhkiras and the Qajar desire to administer production that would soon proliferate throughout the country. Fath ʿAli Shah's many progeny, scattered as they were in various positions throughout the country, played a pivotal role in overseeing tadhkira production both during their father's reign and after. Their dispersal across the country resulted in the establishment of an expansive space for production, beyond the major centers of Tehran and Isfahan, and served as a way to incorporate the poetry of locally based individuals of the “periphery” into the grander library schematic.

From Shiraz, Fath ʿAli Shah's son Husayn ʿAli Mirza Farmanfarma, the long-time governor of Fars, commissioned a work (Tazkirih-yi Dilgusha, Shiraz, ca. 1824–25) on the city's history, its celebrated figures (e.g., the poets Saʿdi and Hafiz), the poetry of the royal family, and other poets contemporary with the ruling monarch.Footnote 50 Around the same time, likely in Borujerd, the poet “Ashraf” composed Lataʾif al-Madaʾih wa Zaraʾif al-Manaqib (1822–23) dedicated to poets praising its governor Muhammad Taqi Mirza Hisam al-Saltana, the shah's seventh son.Footnote 51 In Tabaristan, Muhammad Kazim Mirza commissioned Badayiʿ al-Afkar (1824), arranged according to poetic form.Footnote 52 Closer to home in Tehran, the crown prince ʿAbbas Mirza (d. 1833) commissioned the prolific Qajar historian ʿAbd al-Razzaq Dunbuli (d. 1827–28) to pen Nigaristan-i Dara (1825–26) on the poets contemporary with Fath ʿAli Shah's reign.Footnote 53

Even though these works range in thematic and temporal focus they indicate the way the geographically dispersed Qajar royal family invested itself in tadhkira production and helped shape the direction of its output. All of these works contained entries dedicated to the poetry of the royal family itself or to poets praising the royal family, or focused on Fath ʿAli Shah's literary contemporaries. Although the account presented here undoubtedly privileges the view from the Qajar court in Tehran and its efforts to harness tadhkira production for its own purposes, this emphasis should not be taken to mean that local tadhkiras were incapable of articulating regional attitudes and identities at the same time. For example, the insistence by the author of Tazkirih-yi Dilgusha to specifically include information on Shiraz's history, buildings, gardens, and celebrated poets, alongside entries on royal poets and the author's contemporaries, points to how Qajar-era tadhkiras could strive to incorporate information on regional identities, history, and community even while serving as a source for a larger state-centered tadhkira project.Footnote 54

The Qajar court's dedication to commissioning tadhkiras, many of which would serve as sources for larger tadhkiras produced in Tehran itself, is the defining procedural element of the restructuring of the tadhkira library here. The Qajar royal family would go even a step further by composing their own works, an occurrence unmatched under previous dynasties like the Timurids or Safavids. Doing so created an additional vector that privileged contemporary, local, and oftentimes royal poetic composition over a larger regional and historical one. Once again the sons of Fath ʿAli Shah led the way, most prominent among them Mahmud Mirza (d. between 1854 and 1858).

Throughout his career Mahmud Mirza composed no less than four tadhkiras dedicated to recording the lives of contemporary and historical poets from Iran and beyond. But the overwhelming focus remained on those poets related to Fath ʿAli Shah's court and his time. His Bayan-i Mahmud (Tehran, 1824–25) focused on contemporary poets only, whereas Gulshan-i Mahmud (Tehran, 1834–35) exclusively focused on the notices and poetry of forty-eight sons of Fath ʿAli Shah and was commissioned by the monarch himself.Footnote 55 Another work, Nuql-i Majlis (Lorestan, 1825–26), recorded the poetry of the shah's harem and other female poets who praised him, in addition to historical notices of other prominent women poets throughout history.Footnote 56 As a member of the Qajar household, Mahmud Mirza was only unique on account of his prolific output. Several of his brothers composed tadhkiras during the reign of their father (and after his death), and the practice continued into the reign of Muhammad Shah (1834–48).Footnote 57

Interestingly, a Qajar prince's falling out of favor with the royal family could result in a tadhkira with significantly broader horizons, as its author was no longer bound by the centralizing forces governing its compilation and singular focus on the poets of Qajar domains. The one-time governor of Kerman, Hulaku Mirza, fled for his safety from Qajar lands after Muhammad Shah attained the throne, first to Sistan in 1836 and then to Ottoman-controlled territory.Footnote 58 It was during these travels outside of Qajar domains that he eventually completed his Kharabat (1840–41). The work contained notices on Iranian, Arab, Afghan, Uzbek, and Hindu poets and examples of Turkish and Arabic poetry throughout history and during contemporary times.Footnote 59 He later created a redaction of the work, entitled Mastabih-yi Kharab (after 1840), while in Istanbul, that was focused exclusively on contemporary Persian, Indian, and Turkish poets writing in Persian and Turkish.Footnote 60 In the introduction to each tadhkira, Hulaku Mirza notes that his exile from Qajar lands and traveling with no companion who spoke his language motivated his writing.Footnote 61

Members of the Qajar royal household were supported by ruling elites, the secretarial class, and unaffiliated authors who helped reconstitute and reconfigure the tadhkira library. From Sanandaj to Shiraz, works devoted to local and contemporary poets proliferated during the reigns of Fath ʿAli Shah and Nasir al-Din Shah (r. 1848–96). Such works were guided by either a focus on a particular locale (e.g., Yazd) or devoted to praising a certain local patron. In the latter case, this almost always meant the lives recorded were local and contemporary. Isfahan in particular, due to its higher concentration of poets than most places, not only witnessed an outpouring of tadhkiras for poets competing for patronage but also ones specifically devoted to poets of nearby places, outside the urban core, such as Chahar Mahal and Bakhtiar (Makhzan al-Durar, 1868–69), and Zavareh (Tuhfat al-Shuʿaraʾ, late 19th century).Footnote 62

This desire by the Qajar state to create and utilize a network of texts in support of dynastic aims can be seen in how the court of Fath ʿAli Shah compiled the definitive tadhkira of his reign, Anjuman-i Khaqan (Tehran, 1818–19). Eventually completed by Muhammad Fadil Khan Garrusi “Ravi,” the work underwent several iterations before being completed. The task initially fell to Ahmad Bayg Gurgi “Akhtar,” who worked on the first installment of the work under the title Anjuman-i Ara (Tehran, 1816–17) up until his death. Akhtar's brother extended the work for an additional two years until his own death, after which Garrusi brought it to fruition. In an effort to create this most complete account of the poets of his reign, Fath ʿAli Shah sought to ensure the inclusion of poets throughout his lands by commissioning texts devoted to poets on the periphery. He instructed the governor of Kerman, for example, to collect information on the poets there and envisioned the commissioned text to contribute to the larger work being produced in Tehran. The governor obliged and the result was Mirza ʿAbd al-Razzaq Gawhar Kirmani's Shuʿara-yi Kirman (Kerman, 1820–21).Footnote 63

For the remainder of the 19th century, the growing library of tadhkiras of Qajar lands served as an accessible catalog for later authors to draw upon in compiling their works. These authors could now utilize recently completed local sources to create larger comprehensive ones dedicated to poets of Qajar lands, like Anjuman-i Khaqan. Hadiqat al-Shuʿaraʾ (Kermanshah, 1878–79), composed by Hajji Ahmad Ishik Aqasi Shirazi “Divan Baygi,” represents a clear example of such a process at work. The author was able to construct his work by drawing on texts from the 1830s–1850s dedicated to the local poets of Kermanshah, Kurdistan, and Naiin and collating those works into his own. In this case, it is important to understand how administrative opportunities and bureaucratic pathways stretching throughout Qajar domains could afford an author the opportunity to access the library of tadhkiras. One need not simply sit at the court in Tehran and wait for texts arriving from the periphery to the core; one could excel by being on the move. Divan Baygi's own peregrinations through Shiraz, Khurasan, Isfahan, Yazd, and Tehran, while serving in administrative capacities to various elites, allowed him to come into contact with original local sources on a firsthand basis.Footnote 64

CIRCULATION AND CITATION NETWORKS

One of the main features assisting the development and construction of the transregional tadhkira library over space and time was the manner by which texts served as a collection to be utilized for the crafting of new works. This compilatory practice of tadhkira authors, relying on a historically and geographically vast corpus of earlier texts as source material to be incorporated, reworked, and repackaged into new works—themselves to be used by future generations of scholars—gives force to the idea that these texts constituted an interconnected and continually developing library. The process of compilation that defined the production of Persian tadhkiras was not unique to the genre. Muhsin al-Musawi notes that the writing, rewriting, and commentary practices found in a wide range of medieval Arabic texts created a “library of works in the Islamic world [that] grew over centuries as part of a process of ongoing communication, emulation, explanation, gloss, debate, and counter-discourse.”Footnote 65 Dictionaries, compendia, encyclopedias, and other voluminous works “map out a society and its individual scenes and lives across time, space, and cultures, and in so doing, they redefine a library as more than any particular books or private collections.”Footnote 66 The tadhkira of Persian poets was equally adept at emboldening such a process and was as well equipped to elucidate how different conceptualizations of such a collective literary sphere shifted over space and time.Footnote 67

While the utilization of earlier tadhkiras reflected the common practical need of the tadhkira author to compile the content of his own work, the practice of citing previous texts was less than uniform. A unified list of names of previous texts could appear in the introduction (muqaddama) or conclusion (khātima). Alternatively, reference to the title of a text could simply be made in an individual biographic entry as the source of a particular piece of information. Tadhkira authors did not always feel the need to state their sources directly, but instead remained content with incorporating, paraphrasing, rewriting, and copying from previous works—with or without attribution—for different reasons.

Tadhkira authors, for example, could borrow or copy from previous works without attribution in an effort to pass off the work as an originally conceived product, perhaps to yield easy prestige or financial remuneration from a patron. Texts moving across communities of authors in this manner, as Jason Scott-Warren has observed with regard to early modern England, “came under pressure and were explicitly or implicitly rewritten to serve new interests … [and] transformed in order to be put to entirely new uses.”Footnote 68 Moreover, some authors even repackaged, modified, or abridged their own work under different titles as a low-cost way to attract the attention of a new patron or fulfill the desire to produce the most up-to-date compilation of a life's work. In one of the more extreme examples in this regard, Taqi Kashi continued to amend his Khulasat al-Ashʿar wa Zubdat al-Afkar (late 16th or early 17th century) multiple times, continually incorporating the lives and verse of more poets and updating each new version with his reflections on the seemingly never-ending process of tadhkira compilation.Footnote 69 Finally, after nearly thirty years, he decided to bar himself from “the door of Tazkirah-writing and end his troubles of authorship.”Footnote 70

The myriad ways in which tadhkira authors used, made reference to, engaged, and repackaged the vast corpus of previous texts, sometimes as a recognized continuation (dhayl), completion (takmila), or selection (muntakhab), constituted a crucial element in sustaining an ever-expanding transregional library. Again, this was a not a practice in any way unique to the compilation of tadhkiras of Persian poets or the 18th and 19th centuries. The Arabic biographical tradition during the classical and medieval periods privileged the use of formulaic styles, organizational models, investigative scope, and the desire to update previous works in an effort to create continuity among scholarly output and knowledge production across successive generations.Footnote 71 Encyclopedists in Mamluk Egypt and Syria, likewise, sought to reorganize, correct, and re-present material found in previous works to be placed alongside newer information.Footnote 72

Citations—as intertextual links connecting multiple tadhkiras across space and time—may serve as an additional way to assess the constitution of the transregional library of tadhkiras as a whole. “Citation sites” or “citation moments,” as Ronit Ricci has aptly put it, can facilitate the exploration of textual contact and exchange connecting peoples across vast geographic terrains and over centuries, in this case a community of tadhkira authors.Footnote 73 Whereas Ricci widens the perspective to consider networks of language and literature through citations of text (i.e., phrases of words) and matters of orthography, the focus here is on citations of texts (i.e., titles of tadhkiras). These citations found in tadhkiras can be divided into two types: those mentioned together as a compiled list in a tadhkira’s introduction or conclusion, and those to which individual references are made within the body of the tadhkira text itself. (The maps presented use both types of citations as data points.)

Cited texts should not necessarily be equated with sources utilized. However, even without the ability to establish a direct genealogical linkage between different texts as sources often do, the value of citations resides in the way they connote an authorial awareness of a body of texts—in this case, the library of tadhkiras. Whereas sources help establish the level of interconnectivity among texts of the tadhkira library, citations (while potentially being able to serve that function) are equipped to help establish how tadhkira authors conceptualized this library. Citations provide insight into a tadhkira author's textual purview through the mention of other texts. Assessing different authors’ purviews by cataloging what texts across space and time were recorded allows for a comparative insight into how authors viewed their surrounding literary universe. In this way, citations may be best understood as a paratextual element of the tadhkira, serving to “surround it and extend it” and to establish its “presence in the world, its ‘reception’ and consumption.”Footnote 74 With the insight they provide into a text's purview, or the surrounding literary world as “seen” by an author, citations may be best described as sites of sight: they demonstrate how authors viewed the catalog of texts comprising a transregional library.

Scholars in Islamic studies have used the presence of citations to help reconstruct the popularity, demand, and circulation of certain texts for a particular population at a given time, often across vast terrains. Maria Szuppe understands the citation lists of Central Asian tadhkiras as “a form of authoritative ‘bibliography’” that indicates a text's popularity and expansion across the Persianate sphere.Footnote 75 In assessing several such lists, she concludes that “a standard group of particular texts appears, regardless of the date and place of composition of the tadhkera” to form “the core of the ‘neo-classical’ sources, and serve as universally authoritative references for tadhkera writing.”Footnote 76

My purpose here is not to use citations to determine the popularity of a text for tadhkira authors. Rather, I am interested in using cited texts to understand how authors across space and time accessed and viewed the transregional library of tadhkiras in the 18th and 19th centuries and what this says about the labor practices of tadhkira production more generally. To what extent, for example, were tadhkira authors aware of other coeval tadhkiras in 18th-century South Asia, when production was most closely tied to poetic assemblies and networks? Were 19th-century tadhkira authors more or less inclined to cite texts produced within their sovereign borders during a time when state-sponsored production dominated? How was an author's knowledge of the transregional library of tadhkiras impacted by the labor practices of tadhkira production at different courts?

Map 4 depicts a citation network among tadhkiras produced in 18th- and 19th-century Iran and South Asia. As this network is meant to depict only the intertextual citations of tadhkiras during the 1700–1900 period, it does not include citations of tadhkiras produced in earlier centuries. Although space prohibits a full analysis of this network, it is presented here to visualize the manner in which 18th- and 19th-century tadhkiras were connected to one another through their use of citations. What the network demonstrates, on the broadest of levels, is that there was little cross-regional citation among tadhkiras of Iran and South Asia during this time. Moreover, it elucidates that the network connections between tadhkiras of South Asia were of a more decentralized nature than the interrelations among tadhkiras produced in Iran. Recognizing these general characteristics illuminates the manner in which tadhkiras produced in different places across the Persianate world displayed divergent purviews of the tadhkira library.

MAP 4. Intertextual Citations between Tadhkiras of Iran and South Asia in the 18th and 19th Centuries

One way to explore how authors viewed the library of tadhkiras in distinctive ways is by comparing the citation lists of two coeval works produced in different locations. The example presented here relates to two 19th-century tadhkiras, Majmaʿ al-Fusahaʾ (Tehran, 1871) of Rida Quli Khan Hidayat (d. 1871) and Sayyid Nur al-Hasan Khan's Nigaristan-i Sukhan (Bhopal, 1875). These texts provide a rich ground for comparison: Majmaʿ al-Fusahaʾ and Nigaristan-i Sukhan were produced at nearly the same time, on opposite ends of the Persianate world, and contain two of the most voluminous lists of citations to be found in any 19th-century tadhkira (nineteen citations for Majmaʿ al-Fusahaʾ and twenty-six for Nigaristan-i Sukhan). Finally, each text offers its citations in the form of a comprehensive list found in either the introduction or conclusion.Footnote 77

An appraisal of each text's citations reveals how each author distinctively viewed and accessed the library of tadhkiras as a function of the general labor practices of tadhkira production at their individual courts. The two works share seven citations, a list that includes some of the most often cited, well-known, and widely circulated tadhkiras of the medieval and early modern periods, such as Lubab al-Albab (Ucch, 1221), Tadhkirat al-Shuʿaraʾ (Herat, 1487), and Haft Iqlim (Delhi, 1593). The explicit shared citations of these historically and geographically distant texts by two late 19th-century tadhkiras of Tehran and Bhopal is itself testament to their revered status and longevity. If one wished to ascribe the status of “authoritative bibliography” to regularly recurring citations, then the three texts listed above would be viable candidates.

But the citation lists of these two 19th-century tadhkiras also diverge quite significantly, as they only contain one shared citation from the 200-year period preceding their compilation: the Atishkadih (Qom, 1779) of Azar Baygdili (d. 1781). More remarkably, save the shared citation to this single text, Majmaʿ al-Fusahaʾ does not cite a single text composed outside of Qajar lands and Nigaristan-i Sukhan does not cite a single text outside of South Asia for the entirety of the 1700–1900 period. Map 5 demonstrates the divergent textual purviews of Majmaʿ al-Fusahaʾ and Nigaristan-i Sukhan by connecting these texts to those they cited. The map illustrates the more restrictive geographic scope of citations of texts produced after 1700.

MAP 5. Citation Network of Majmaʿ al-Fusahaʾ (1871) and Nigaristan-i Sukhan (1875)

The stark contrast in how Hidayat and Nur al-Hasan Khan chose to view and utilize the library of tadhkiras was a consequence of their locations at different dynastic courts and what tadhkira production came to signify there. Attached to the Qajar court in Tehran, the diplomat and historian Hidayat was at the nexus of Qajar efforts seeking to bolster the dynasty's place in Persian and Iranian historiography.Footnote 78 The six-volume Majmaʿ al-Fusahaʾ was a major part of this project and signified a solidification of Qajar contributions to tadhkira production that warranted the use and recognition of contemporary sources from Qajar domains. As such, Hidayat's position at the Qajar court necessitated a textual purview that comprehensively accounted for poetry in Qajar lands and valued, above all else, the tadhkiras produced there. Among the texts cited by Hidayat are many of those tadhkiras produced in early Qajar times that were confined to local poetic output and meant to serve the bureaucratic pathways leading up to the court in Tehran. This centripetal flow of texts to the Qajar capital in Tehran may also help explain why Nur al-Hasan Khan did not cite any 19th-century tadhkiras from Iran: such texts were primarily intended to be accessed and distributed within Qajar territories, rather than outside of them. This was as true during the reign of Fath ʿAli Shah, as seen in the example of Anjuman-i Ara, as it was for the reign of Nasir al-Din Shah, at least until the completion of Majmaʿ al-Fusahaʾ. This does not mean one should extrapolate from the inattention of Majmaʿ al-Fusahaʾ to tadhkiras outside of Qajar lands a similar lack of awareness by all Iranian tadhkira authors. Rather, it is meant to demonstrate how the textual purview and dominant labor practice of tadhkira production at the Qajar court can be gleaned from the citations of a central figure in Qajar-era tadhkira writing.

Nur al-Hasan Khan's Nigaristan-i Sukhan was equally affected by the attitudes and sensibilities governing tadhkira production of the Bhopal court. During the 1870s and 1880s, Bhopal witnessed the compilation of no less than six tadhkiras, earning it the distinction of the last major center of tadhkira production of Persian poets in 19th-century South Asia. The rich atmosphere of tadhkira production at Bhopal not only reflects how Persian was relevant for a princely state in the 19th century, but that the court remained connected to the larger world of Persian literary culture outside its sovereign domains: tadhkira production at Bhopal was defined by an ongoing process that sought to create the most comprehensive and up-to-date work by incorporating more and more source material from across South Asia. The extensive list of citations in Nigaristan-i Sukhan can thus be situated within the larger labor practices of tadhkira production at the Bhopal court, defined by a desire to comprehensively record poetic activity and thoroughly consider all available tadhkiras for this effort.

The ongoing effort in Bhopal to compile a comprehensive tadhkira through several updates is not readily apparent from the publication of the first tadhkira produced there, Shamʿ-i Anjuman (1875). In the introduction Siddiq Hasan Khan (d. 1890), who was husband to the ruling begum and father of Nur al-Hasan Khan, noted that recording the lives of all ancient, modern, and contemporary poets across Iran and South Asia was an impossible task.Footnote 79 Instead, one had to be selective, even if that still meant including entries on nearly 1,000 poets. But if the author of Shamʿ-i Anjuman was conscious of the limits to comprehensiveness, then this attitude changed rather quickly. Shortly after Shamʿ-i Anjuman went to press at the court-affiliated Matbaʿ-i Shahjahani, the author received material from contemporary poets in Bengal and Dhakka who submitted it for inclusion. As the information arrived too late, Nigaristan-i Sukhan was printed that very same year as a completion (takmila) to Shamʿ-i Anjuman for the expressed purpose of adding this late-arriving material and information on other contemporary poets.Footnote 80

The attentiveness of Nigaristan-i Sukhan to shaping itself as a more comprehensive and updated version of its predecessor was not restricted to the incorporation of new information. Unlike the earlier Shamʿ-i Anjuman, Nigaristan-i Sukhan now listed twenty-six tadhkiras “considered” during the time of the writing, often accompanied with a description of the author or the work itself.Footnote 81 Of particular note is Nur al-Hasan Khan's mention of how the advent of printing created “easy accessibility” (sahl al- ḥuṣūl) to texts such as Azar's Atishkadih (printed in Bombay in the 1860s), the only cited tadhkira produced in Iran between 1700 and 1900.Footnote 82 The reference not only indicates that print technology could now assist the compilation of a tadhkira, but again helps explain why Nigaristan-i Sukhan cited no tadhkiras of 19th-century Qajar Iran: few tadhkiras of 19th-century Qajar Iran were printed prior to the late 1870s. However, without additional empirical data detailing the circulation of printed tadhkiras in the 19th century, this explanation remains incomplete.Footnote 83

Nigaristan-i Sukhan was succeeded by two other tadhkiras printed by the state's press: Subh -i Gulshan (1878), by another of Siddiq Hasan Khan's sons, and Ruz-i Rawshan (1880). Each text was constructed as a supplement to the tadhkiras preceding it and confirms the dual motivation to update the previous works: to include both notices on additional contemporary poets and tadhkiras not considered by the other previous authors. The author of Subh -i Gulshan, for example, explains in the introduction the benefit of consulting “new tadhkiras,” like Aftab ʿAlamtab (Lucknow, 1852–53) and Nishtar-i ʿIshq (Lucknow, 1818), and “other rare letters” in his possession to create an updated work.Footnote 84Ruz-i Rawshan, which culminated the court's effort to create an up-to-date and comprehensive tadhkira and featured entries on more than 2,400 poets, once again utilized newly accessible tadhkiras to do so. To help readers recognize the updated nature of his work, he marked the end of entries appearing in the earlier works with the letters shīn, nūn, or ṣād (i.e., the first letter of the title of the other Bhopali tadhkiras).Footnote 85 New entries, whether related to historical or contemporary poets, that did not appear in Shamʿ-i Anjuman, Nigaristan-i Sukhan, or Subh-i Gulshan were left unmarked. Not unlike the authors of the two tadhkiras preceding it, the author of Ruz-i Rawshan aspired to compile the most comprehensive and up-to-date tadhkira by incorporating newly available sources and entries on contemporary poets, in particular across South Asia.

A comparison of the citation lists of Majmaʿ al-Fusahaʾ and Nigaristan-i Sukhan reveals the divergent perceptions of the tadhkira library in the 19th century and how it was being differentially accessed by two authors on opposite ends of the Persianate world. Whereas Majmaʿ al-Fusahaʾ emphasized recording poetic activity within Qajar lands, Nigaristan-i Sukhan sought to catalog activity across South Asia and well outside of the princely state's sovereign borders. These divergent approaches may be best understood as indicative of the different labor practices of tadhkira production at the Qajar and Bhopal courts.

CONCLUSION

This article has addressed the production and circulation of tadhkiras of Persian poets in the 18th and 19th centuries by employing a macroanalytical approach and utilizing quantifiable data. This was done to better grasp general trends in tadhkira production and circulation over space and time and their intersection with larger social and political phenomena, such as state disintegration and formation. Although the approach has limitations, it also presents new methodological opportunities for exploring textual production and circulation on a transregional basis over significant periods of time.

Although only one tadhkira of poets was produced in Iran during the 18th century (Azar's Atishkadih), the period represents the flowering of tadhkira production in South Asia. Following the breakup of the Mughal Empire, tadhkiras proliferated in different urban centers, drawing inspiration from poetic assemblies and networks. During the 19th century, Persian tadhkira production shifted to the domain of the state. In Iran, the Qajar court became heavily invested in tadhkira production to place Qajar poetic contributions at the center of Persian's literary universe. Rida Quli Khan Hidayat's Majmaʿ al-Fusahaʾ was in many ways the crowning achievement of this project. Not only did his work serve as the culminating text of Qajar efforts that began earlier in the century, his vision of the tadhkira library (as ascertained through his citations) reflected an attitude in line with this effort. In South Asia, courtly centers also played a major role in the production and commissioning of tadhkiras, but to a lesser degree than their Qajar counterparts and with varying results. In some places, language politics and the rise of Urdu created a less hospitable atmosphere for court-sponsored tadhkira production, and elsewhere, such as in Arcot, tadhkira production restricted itself to primarily recording the poets, literary debates, and assemblies of its court and immediate environs. The princely state of Bhopal, on the other hand, sought to produce the most comprehensive tadhkira possible by extensively drawing upon the library of tadhkiras to continually update a series of works. As seen in the citation list of Nigaristan-i Sukhan and in the two Bhopali tadhkiras that followed, there was an effort to look beyond the confines of Bhopal to access a more comprehensive library of texts.

Overall it may be said that these features of tadhkira production in the 19th-century Persianate world reflect the differentiated state of Persian literary culture in places like Iran and South Asia. In Iran, Persian literary culture was increasingly falling under the domain of the state and en route to being nationalized; in South Asia, Persian literary culture, as exhibited by the tadhkira of Persian poets genre, was still refashioning itself to elicit connections across a larger regional domain, but in a significantly less robust manner than had existed previously. At least in terms of the tadhkira of poets genre, the space for Persian literary representation was narrowing.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743819000874.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was assisted by a Social Science Research Council Postdoctoral Fellowship for Transregional Research with funds provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Research was also conducted while in residency at the John W. Kluge Center at the US Library of Congress. The author would like to thank Elias Muhanna, Aria Fani, Daniel Majchrowicz, Zahra Shah, the anonymous reviewers of IJMES, and members of the 2017 Middle East Studies Association conference panel “Looking East: Knowledge, Travel, and Friendship between the Middle East and Asia in the 19th Century,” where this research was first presented, for their critical comments and insights. Special thanks to Prashant Keshavmurthy for suggesting the metaphor of a “tadhkira library” and Lenka Starkova for help with the maps.