The 1920s were the global age of alphabet revolutions. Although in the history of the Middle East the most famous of them was the Turkish alphabet revolution that replaced the Arabic alphabet with a latinized one in 1928, the revolutionary fervor was present across Eurasia. In 1924, Azerbaijan was the first Soviet Socialist Republic to latinize its alphabet; and two years later, the future of the Arabic alphabet was the most contested issue at the First Turcology Congress, which convened in Baku under the auspices of the Central Committee of the USSR. In 1928, a mixed group of Russian and Turkic scholars invented the Unified New Turkic Alphabet (unifitsirovannyi novyi tiurkskii alfavit; UNTA) to replace all Arabic alphabets with a latinized one. “Latinization,” as Lenin allegedly said, “[was] the Great Revolution in the East!”Footnote 1 Quickly, the latinization movement spread even further, as the UNTA became the basis of the Mongolian, Kurdish, and Persian Latin alphabets as well. Even the first Chinese Latin alphabet, the mother of contemporary pinyin, was a reformed version of the UNTA. The simultaneous alphabet revolutions in Turkey and the USSR in the 1920s, in short, reverberated globally.

The purpose of this article is to revise the extant paradigms of the origins of these alphabet revolutions that have hitherto been treated separately, mostly due to Cold War politics. The first wave of scholarship on alphabet reforms and revolutions in the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey, for instance, treated the movement as merely an ongoing effort at Westernization and secularization.Footnote 2 In contrast, the scholarship on latinization in the Soviet Union has largely been defined as a product of Soviet colonialism and imperialism that allegedly sought to divide and conquer the Turkic nations.Footnote 3 More recent scholarship on the subject has correctly challenged these earlier works, although it has continued to treat the two movements separately.Footnote 4 Nergis Erturk's innovative study of Turkish literary modernity reinterpreted the Turkish alphabet revolution as an outcome of Western colonialism and phonocentrism, which designated the Arabic script as a backward writing technology.Footnote 5 In the case of the latinization movement in the USSR, scholars also have moved away from Cold War narratives and demonstrated latinization's intimate connections with anti-imperialism, internationalism, and the Soviet nationality policies of the 1920s.Footnote 6

This article reevaluates the history of the Soviet and Turkish alphabet revolutions as the product of a common Russo-Ottoman techno-political space. Alphabet reforms in the Russo-Ottoman world started in the 1860s in Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, and Tbilisi, the capital of Transcaucasia (Ru. Zakavkaz'e), the polyglot region in the Russian Empire that roughly corresponds to present-day Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia. In the 1860s, Muslim and non-Muslim intellectuals argued for the first time that the Arabic alphabet prevented the world of Islam from achieving civilizational progress and started proposing new phonetic alphabets that were based on writing each letter separately. Although Istanbul served as the center of the movement, Sultan Abdulhamid II's (r. 1876–1909) regime of censorship brought it to a halt in the Ottoman Empire; instead, during the Hamidian decades, the Crimea and Tbilisi carried the flag of reform as they became major centers of alphabet innovations. Later, when the Russian imperial reforms following defeat in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) rendered the Muslim populations increased freedom to print works in their own languages, the alphabet debates increased exponentially in Transcaucasia. After the Young Turk Revolution in 1908, these debates again spread into the Ottoman Empire. Eventually, the movement culminated in the revolutions of the 1920s, first in the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic in 1924, then in the Soviet Union at large and in the Republic of Turkey in 1928. The history of the alphabet reforms in the Russian and Ottoman empires, which ultimately inspired a greater alphabet revolution across Eurasia, demands a new approach that integrates the two imperial histories.

In rethinking the alphabet revolution, I would like to suggest that neither the paradigm of modernization, nor of secularization, nor that of Western colonialism is sufficient to understand its origins in the 1860s. The anxieties concerning the written alphabet of the Ottoman and Transcaucasian reformers were deeply interwoven with the new media ecology in a globalizing information age that involved the telegraph and the increased use of movable metal type in the Ottoman Empire and the Muslim regions of the Russian Empire. Although the centrality of the telegraph and the printing press in the dissemination of reformist ideas has received much attention in scholarship, this article proposes the need to study the material impact of these technologies on the medium of writing itself.Footnote 7 Taking Nile Green's exploration of the effect of industrializing print technologies on Persian and Arabic typography one step further, the first section of this article examines the intimate connections between the Arabic Morse code, typographic reforms, and the alphabet question in the 1860s.Footnote 8 The 19th-century communications infrastructures and print technologies, I contend, brought a new mode of knowledge and information production that challenged the medium of the Arabic letters themselves. The letterpress in particular imposed new limits on writing at the same time as it generated a new space for alternative politics in which the reformers could utilize the medium of typographic interface to argue for radically different political visions. The materiality of print in this way gave birth to an unforeseen engagement with the meaning of communication, language, labor, and literacy in a modernizing economy. Through this engagement, a new kind of subject was born, an imagined “typographic Muslim,” whose mental and physical world had to adapt to the techno-politics of new communications infrastructures and technologies.

Although the first reformers were steeped in the new technological conditions and considered alphabet reforms a means to expedite knowledge production and acquisition, the second generation of reformers was faced with the greater challenge that arrived with a potential change of the alphabet, that is, linguistic representation. The second section thus turns to the politics of language that typographic imaginations lent to Muslim reformers in the Russo-Ottoman space from the 1880s to the 1920s. In particular, this article highlights the hitherto unexplored debate between the Crimean reformer Ismail Gasprinskii (1851–1914), who sought a unified literary common for Turco-Muslims across Eurasia, and the Azeri reformer Mohammad Shakhtakhtinskii (Az. Mehemmed Aga Sahtaxtili; 1846–1931), an alphabet-innovator who defied Gasprinskii's call for unification and strove for recognition of vernacular languages as a medium of literary expression. The unresolved dispute between the two figures anticipated the larger debates about language and alphabet following the Russian reform movement in 1905 and the Young Turk Revolution in 1908. As the Russo-Ottoman imperial and postimperial space witnessed an increased use of media technologies and the rise of nationalist language projects, the Latin alphabet emerged as a serious alternative to earlier proposals and eventually triumphed during the alphabet revolutions of the 1920s. By examining the interweaving of sociopolitical worlds and typographic imaginations that formed around new media technologies and alphabets, this article offers a reconsideration of the alphabet revolutions as an integral part of the communications revolution that was simultaneously taking place across the Ottoman and Russian empires.

Telegraphic Epistemologies and Typographic Muslims

Script reform in the Russo-Ottoman world started almost simultaneously in Istanbul and Tbilisi. Munif Pasha (1830–1910), the founding director of the Ottoman Society of Sciences and the chief interpreter at the Ottoman Sublime Porte, and Mirza Fatali Akhundzade (Akhundov; 1812–1878), the famous Iranian Azerbaijani playwright and interpreter to the Russian viceroy of Caucasus, were the two figures who demanded that a fundamental transformation of the Arabic alphabet was necessary to ensure scientific and literary progress in the Muslim world. In 1862, Munif Pasha delivered a speech at the newly founded Ottoman Society of Sciences on the deficiencies of the “method of writing” (usul-u resm-i hatt) and the need for a reform in the script to facilitate the acquisition, accumulation, and dissemination of information and knowledge.Footnote 9 A year later, Akhundzade traveled to Istanbul to present his proposal for reform to the Ottoman Society of Sciences. The long journey of Arabic alphabet reforms thus began.

Both Munif Pasha and Akhundzade found justification for reform in the expanding technology of the movable metal type that had already become ubiquitous in major centers of the Ottoman and Russian empires by the 1860s. Although printing was introduced to the Ottoman Empire in the 18th century by Ibrahim Muteferrika (1674–1745), its impact on publishing in the Arabic alphabet was arguably very limited until the Tanzimat era (1839–76).Footnote 10 Yet, despite the limited growth of printing in the Arabic script, the Greeks, Armenians, Jews, and missionaries in the Ottoman Empire had been publishing in their respective scripts and languages before and after Muteferrika's press, and their dominant presence undoubtedly served as a catalyzer for the Arabic alphabet reform.Footnote 11 The Armenians, for instance, were the leading publishers, typeface designers, and Arabic type-casters in the Ottoman Empire. In addition to publishing in the Armenian language, they also published dozens of journals and newspapers in Ottoman Turkish using the Armenian alphabet. The Armenian-lettered Ottoman Turkish publications were in fact very popular among the educated public, for some of them were translations of European literature and scientific advancements.Footnote 12 Ahmet Ihsan Tokgoz (1868–1942), one of the leading publishers at the turn of the century in Istanbul, recalls that he used to read these newspapers and journals, as well as translated Turkish literature published in the Armenian alphabet, because the number of Arabic-lettered Ottoman Turkish books on Western sciences and literature could not reach that of the Armenian-lettered Ottoman Turkish journals and books.Footnote 13 In 1883, a certain Macid Pasha even proposed that the Arabic alphabet should be replaced with Armenian.Footnote 14 Similarly, Armenian publishers were prominent in Russia and Transcaucasia during the same period. According to the 1912 notes of Armenian historian Teotig, Tbilisi was in fact the largest center of Armenian publishing in Russia after Moscow, and it also was home to publishing in the Russian and Georgian alphabets.Footnote 15

The intellectual stimulus offered by the Armenians and other non-Muslims aside, the dominant presence of non-Muslim scripts was crucial in rethinking of the graphic interface of the Arabic alphabet. All of the non-Muslim scripts—Armenian, Greek, Latin, Russian, and Georgian—were written with separate letters, and when compared with the Arabic alphabet the number of sorts, or metal types, was significantly smaller, as will be explained. The claim of both Munif Pasha and Akhundzade that the Arabic alphabet was the biggest obstacle in typographical advancement and scientific progress in the world of Islam was formulated within cosmopolitan, multilingual, and multi-scripted imperial spaces.

Akhundzade and Munif Pasha's arguments about typography and the Arabic alphabet constituted a blueprint for the reformers and revolutionaries of the following decades. First, and most important, many of the letters in the Arabic alphabet were written differently depending on their positions in the word. Most letters had different glyphs for the beginning, the middle, and the end of a word, and a fourth glyph as an isolated sign. Akhundzade gave the example of ‘ayn ﻉ, which was عـ as the initial form, ـعـ in the middle, and ـع in the final form.Footnote 16 In typography, the absence of separate letters (unlike the Latin alphabet) required four different sorts for each letter. In addition, depending on the calligraphic typeface, the connection of letters also could show variation, thereby demanding the engraving of extra sorts for combined letters. The name Mahmud offers a good example. Written with the letters mim م, ha ح, mim م, waw و, and dal د, Mahmud in today's Unicode can be typed as follows: محمود. Yet in the common calligraphic style of the time, known as naskh, the same word was written differently, as the first three letters (mim, ha, and mim) were connected to each other vertically instead of horizontally. In the world of typography this necessitated a ligature, that is, a separate sort that combined these three letters. Naskh, in other words, demanded ligatures that combined multiple Arabic letters at once—mim م, ha ح, and mim م; lam ل and mim م; nun ن and cim ج; and dozens more. This practice had started with the first Arabic printing presses and then continued, but the end result was a type case that was significantly larger than the type case of any separate-lettered language—Latin, Armenian, Georgian, Russian, etc. In short, this system of writing demanded an elaborate practice of typesetting that used more than 500 signs in contrast with the less than 100 for separate-lettered writing systems; the early script reformers believed it was an unnecessary waste of labor and resources. The result was even worse in other calligraphic typefaces, such as ta'liq, which was considered to be aesthetically superior to naskh, but which according to some accounts required a type case of 1,600 to 2,200 signs.Footnote 17

Second, the designation of consonants in the Arabic alphabet was by placement of dots below or above given marks that, according to reformers, slowed reading. For instance, the consonants be ب, pe پ, nun ن, te ت, and se ث were susceptible to optical confusion, especially when handwritten, leading to unnecessary mental labor for the reader. This was an argument for the letterpress as well. Typography was the artistic technique of casting and maintaining a letter within the bounds of a metal square. Once the metal typeface was cast, the letters were trapped in an exact relation to all the dots that belonged to them. Compared to the mechanical precision of the press, the hand was a sloppy imitator. It could misplace or misrepresent the dots, distort meaning, and confuse the mind.

And third, the Arabic letters lacked sufficient signs for vowels, which produced semantic ambiguity in the written word and took extra time to comprehend. As all 20th-century reformers were fond of demonstrating, waw و could be pronounced as an o, ö, u, ü, or v in Turkish, depending on the word. As Munif Pasha himself noted, اون could be pronounced in three different ways, and كورك in six. He was not even satisfied with the use of diacritical marks (harekat) placed below or above a given letter to signify vowels; he claimed that it was still hard to determine which line the diacritics belonged to. Reading Arabic letters, in the words of Munif Pasha, caused “mental confusion” (teşviş-i zihni) and “waste of thought” (sarf-ı efkar).Footnote 18 Articulating typographical problems as cognitive difficulties that obstructed progress in sciences and literature, Munif Pasha considered separate letters (huruf-u mukattaa or huruf-u munfasıla) the only solution.

Although typography undoubtedly played a major role in Munif Pasha's and Akhundzade's proposals for reform, there was another major infrastructural medium that compelled the reformers to ponder the value of separate letters: the telegraph and its medium of transmission, the Morse code. The Morse code, invented by Samuel F. B. Morse in the 1840s, abstracted the twenty-six letters of the English alphabet into dots and dashes, enabling the transfer of messages across large distances through wires. Although a demonstration of the electric telegraph was presented to Sultan Abdulmejid in 1847, the official entry of the telegraph into Ottoman lands did not take place until the Crimean War (1853–56), when the British and the French intervened to prevent Russian expansion into the Ottoman domains. As part of the military endeavor, they installed telegraph cables that connected Istanbul to Varna and the Crimea in 1855. The number of stations expanded after the war with technical support from London and Paris, as the telegraph facilitated the entry of European capital into Ottoman lands. In 1869, the Ottomans established a telegraph factory to reduce the cost of importing equipment, and a decade later they possessed more than 17,000 miles of cables in the imperial domain, which increased even more under Sultan Abdulhamid II (r. 1876–1909).Footnote 19 Meanwhile, Tbilisi also was becoming a center of wired communications in the 1850s and 1860s. Following British and French penetration of the Ottoman empire, in 1858 the German company Siemens & Halske built the first telegraph line between Tbilisi and Kojori, which was quickly followed by new lines that connected Tbilisi to Poti, Moscow (via Stavropol), Baku, and finally Tehran in 1865.Footnote 20

The telegraph enabled not only an unprecedented increase in the circulation of information but also a new epistemology of separate letters in writing the Arabic alphabet. The Morse code was specifically designed for the twenty-six letters of the English language and was easily adapted for French as well. But when the telegraph entered the Ottoman Empire, an Arabic Morse code did not exist, which left French as the official language for telegraphy. Troubled by the linguistic incongruence, a certain Mehmed Bey and Volic Efendi devised the first Ottoman Morse code for Arabic letters in 1856, which was revised and put in practice widely in the 1870s. In devising the Morse code, however, the two technicians encountered a problem similar to the typographic problems that stemmed from the number of glyphs. Instead of rendering each glyph or letter-combination into dots and dashes as in letterpress, Mehmed Bey and Volic Efendi devised an almost exact copy of the French code and used only stand-alone letters of the Arabic alphabet. The Ottoman Morse code was composed of only thirty-two signs, and when it was revised ha ح and hı خ were both assigned the same value, four dots (….), since they represented the same sound in Ottoman Turkish.Footnote 21 It eliminated redundancy and made it easier for Ottoman telegraph operators to learn the code and at the same time put into practice a new form of writing using the Arabic alphabet, as each letter was transmitted individually and separately. The sentence “How do you receive?” (Nasıl alıyorsunuz? نصل اليورسكز؟), for instance, was encoded in the following way:Footnote 22

The problem of coding was common to many non-Roman scripts throughout the semicolonized world. In China, for instance, the problem was even greater than in the Ottoman Empire, since the Chinese writing system was not even alphabetical to begin with. To turn Chinese characters into the Morse code, each character was first translated into a four-digit number, and then the numbers were translated into dots and dashes. When faced with this infrastructural anomaly, many turn-of-the-century scholars argued for alphabetizing the Chinese writing system itself and transcribing each sound separately to increase communication efficiency and facilitate literacy.Footnote 23 What followed were decades of debates about new Chinese alphabets, similar to discussions in the Russo-Ottoman world.

In the Russo-Ottoman space, both telegraphy and typography played a critical role in the development of separate letters and redefining literacy. When Munif Pasha delivered his landmark speech in 1862, Akhundzade deemed it worthwhile to travel to Istanbul to offer his own script proposal, which consisted of letters that were graphically similar to Arabic letters, but with each sign written separately and each vowel signified with an extra letter and with the ability for all signs to be written in conjunction yet retain their independence. In 1863, he arrived and presented his proposal to the Ottoman Society of Sciences. The members of the Society convened twice to discuss the proposal and praised the merits of the alphabet, but many noted that such a radical reform would require republication of all extant literature in the new alphabet. Eventually, they rejected the proposal.Footnote 24

Akhundzade went back to Tbilisi without having made much progress, but he continued promoting his reformist ideas in the Ottoman Empire and Persia, where the impact of the telegraph and movable metal type on the Persian alphabet was similarly felt. Until he died in 1878, Akhundzade wrote dozens of letters to the Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, to Nazir al-Mulk Mahmud Khan, to the Iranian Ministry of Education, to the Ottoman Grand Vizier Ali Pasha, and to Munif Pasha.Footnote 25 But the only person who followed Akhundzade was Mirza Malkom Khan (1833–1908), the well-known Iranian Armenian reformer who met Akhundzade in Istanbul during his visit in 1863. Malkom Khan's interest in alphabet reform also stemmed partially from the telegraphic and typographic world order of which he was a part. Actually, Malkom Khan was the first to introduce the electric telegraph to Persia. In 1858, the same year as the establishment of the line from Tbilisi to Kojori, Malkom Khan connected the Polytechnic College (Dar al-Fonun), where he taught geography and worked as a translator, to the Shah's pleasure garden Bag-e Lalazar.Footnote 26 As the Persian telegraph network expanded in the following years, Malkom Khan was appointed special adviser to the Persian ambassador in Istanbul, and he lived there from 1862 to 1872. In 1868, Malkom Khan wrote a petition to the Ottoman grand vizier and presented his separate-lettered alphabet as an alternative to the extant one.Footnote 27 When his proposal was rejected like Akhundzade's, Malkom Khan decided to publicize it, which caused a minor stir in the Ottoman intellectual community, with Namik Kemal (1840–88), one of the literary giants of the day, vehemently opposing the project.Footnote 28

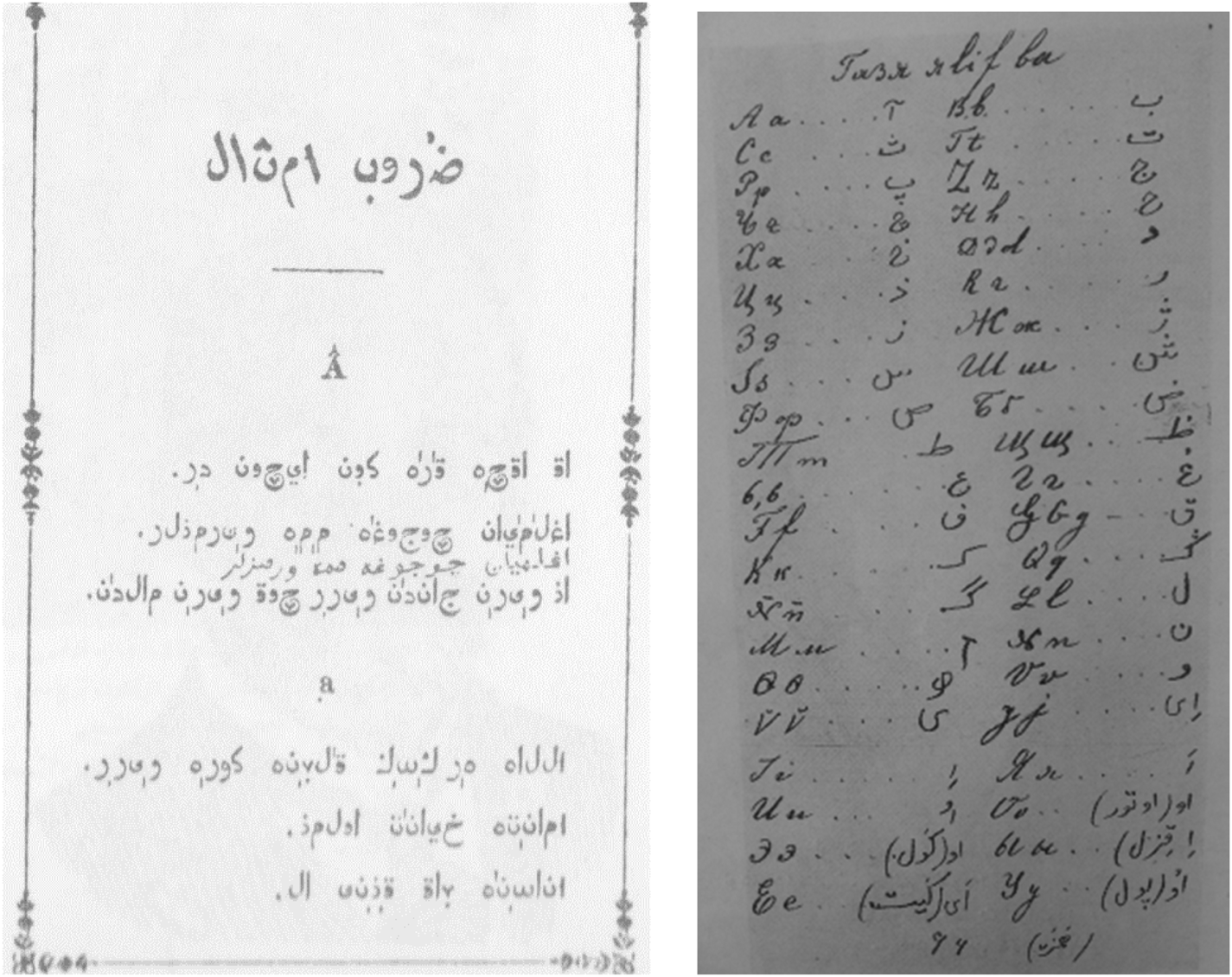

The main difference between the scripts of Malkom Khan and Akhundzade was that the former retained the dots of Arabic letters, showed vowels through diacritics, and had letters that did not connect with each other in a standardized way. Although at first criticized by Akhundzade, the two figures continued collaborating in the 1870s in an effort to reform the Arabic alphabet. Akhundzade later also broke away from his earlier project to keep the design of the letters similar to their originals, and instead created an alphabet that was a mix of Latin and Cyrillic letters (Fig. 1).Footnote 29

Figure 1. Malkom Khan's separate letters and Akhundzade's Latin-Cyrillic letters. From Rahim Ra'isniya, Iran va Usmani dar Astanah-i Qarn-i Bistum (Tabriz: Intishārāt-i Sutūdah, 1385); M. F. Akhundov, Tekst Pisem, Napisannykh na Farsidskom Iazyke (Baku: Izdatel'stvo akademii nauk azerbaidzhanskoi SSR, 1963), 53.

Although none of the proposals was accepted, all three figures involved in the reform movement, Akhundzade, Malkom Khan, and Munif Pasha, agreed on the fundamentals of a new script based on separate letters that conformed with both the new telegraphic epistemology of writing and an efficiency in typographic design and labor. What emerged was an imagined “typographic Muslim,” with cognitive patterns of letter recognition aligned with the mechanical order of the movable type. The only way to change the Islamic world, according to the first reformers of the script, was by eliminating the main barrier to the acquisition of information. The simplicity of typesetting was reformulated as simplicity of perception; the economy of printed letters translated to an economy of mental labor in reading. The lettered mind of the Muslim, in short, was reinvented in the image of typography.

The issue of typographic economy and efficiency was undoubtedly a big part of the printing business itself, and the Ottoman printer-reformers also were involved in the debates about reforming the Arabic alphabet, although they did not agree with the proponents of separate letters. An experimental script at the time was proposed by Ibrahim Sinasi (1826–71), the editor of the first private Turkish journal Tercuman-i Ahval (Translator of events), which started publication in 1860. In 1869, Sinasi invented a new typeface to economize printing, most probably influenced by German and British Orientalists who also had invented a new Arabic typeface at the time.Footnote 30 As mentioned above, more than 500 sorts (metal types) were needed for a proper type case in Ottoman printing due to the different combinations of multiple letters. Sinasi reduced this number to 112, bringing it much closer to the number of sorts in a Roman-lettered type case, and published two works using this experimental typeface (Fig. 2).Footnote 31 Interestingly enough, Sinasi's typeface was very similar to the typeface used in present-day Unicode, which makes Sinasi one of the first typographers to have anticipated the Arabic Unicode; each letter in Sinasi's typeface had its own separate place, as in Mahmud محمود.Footnote 32

Figure 2. Sinasi's typeface and 112 sorts. From Ebuzziya Tevfik, “Sinasi Merhumun Ba'dettenkih Ittihaz Ettigi Hurufun Envai ve A'dadi,” Mecmua-i Ebuzziya 43 (1302): 1274.

Ebuzziya Tevfik (1849–1912), another leading printer-writer of the day, also was in favor of reforming the Arabic script from within, but his “economy” differed greatly from Sinasi's. Ebuzziya claimed that Sinasi's typeface distorted naskh and that despite its semantic correctness it was calligraphically and habitually wrong—Mahmud محمود, after all, did not conform with the rules of naskh as explained earlier.Footnote 33 Moreover, according to Ebuzziya, Sinasi's typeface was a burden for the typesetter, because it was in fact inefficient. To typeset Mahmud, a typesetter using Sinasi's sorts had to arrange five sorts side by side: mim, ha, mim, waw, dal. The same typesetter would use only three sorts (mim + ha + mim, waw, dal) if he used Ebuzziya's naskh typeface and reduce the necessary manual labor by 40 percent. In contrast to those who claimed that the extreme number of signs in a type case was uneconomic, Ebuzziya further argued that a Turkish typesetter of Arabic letters was faster than a French typesetter of Latin letters. He claimed that if a French text written in Latin and Arabic letters was given to a good French typesetter and a bad Turkish typesetter, the latter would arrange the letters faster than the former, despite his lack of linguistic skills. “If anyone at any time is curious about this and does not believe it,” wrote Ebuzziya, “he may try it out himself to eliminate his suspicions.”Footnote 34 What was perceived as a deficiency, in other words, in fact optimized labor in typesetting without sacrificing the calligraphic norms of naskh. Ebuzziya's typeface thus satisfied both an economy of typesetting and calligraphic norms. He was indeed proud to showcase the 519 sorts he used in his printing press, compared to Sinasi's 112 signs.Footnote 35 Typography in Arabic letters was compatible with the demands of a modernizing information society; type cases needed no reduction; and alphabets needed no destruction. At least, that was the view from Ebuzziya's print shop.

Apart from the issue of sign economy, the typographical project of printing each sound separately struck at the heart of imperial language politics and raised concerns about imperial unity. One reformer who immediately recognized script reform as a threat was the Ottoman literary titan Namik Kemal, a friend of Ebuzziya and the first to publicly criticize Malkom Khan's alphabet proposal. According to Namik Kemal, a separate-lettered phonetic alphabet, even if it promised progress in knowledge production, had the potential to cause disintegration of the multilingual and multiethnic composition of the Ottoman Empire. “I do not understand why we need to write letter by letter,” he noted sarcastically, “the nonsense (lakırdı) uttered by each of our people (akvam) as well as all the nations of the civilized world (kaffe-i milel-i mütemeddine). . . . Are we supposed to give an alphabet to the Albanians, Kurds, and Laz, and lend a spiritual weapon (silah-ı manevi) to their hands so that they can press it against our temples?”Footnote 36

Namik Kemal's distinction between nations (millet) of the outside world and the people (akvam) of the empire, such as the Albanians, Kurds, and Laz, was a significant semiotic mark that prioritized a larger Ottoman identity that could only be maintained at the expense of multiethnic and multilingual representation. Indeed, his words anticipated the problems that became central to imperial politics in the early 20th century and ultimately culminated in the formation of separate nation–states. Interestingly enough, in 1910 the Albanians were the first to latinize their script and claim a sovereign national identity. Nevertheless, Namik Kemal's objections were not necessary for long, as under the Hamidian regime of censorship Ottoman alphabet debates came to a temporary halt—even letter foundries were consolidated under one roof to control the casting of sorts.Footnote 37 In the following decades, new alphabetical innovations were harnessed not by the Ottomans but by the Turco-Muslim reformers in the Russian Empire.

Alphabet and Language in the Russo-Ottoman Space

Although typographical debates came to an end in the Ottoman Empire, they found new soil in the Crimea, on the opposite shore of the Black Sea. Ismail Gasprinskii, a leading jadidist figure among the Crimean Tatars of the Russian Empire, entered the Muslim world of publishing in the 1880s. Gasprinskii was among the first to introduce the new method (usul-i jadid) to promote literacy among Muslim students, which was based on dividing each word into its letter components to expedite the speed of learning, and he opened the first new method school in 1884 in Bahcesarai. Breaking away from the traditional memory-based techniques, Gasprinskii's new method was replicated across Muslim Eurasia.Footnote 38 Apart from his pedagogical innovations, Ismail Gasprinskii had a lasting influence on the Muslim world through his bilingual journal Terjuman/Perevodchik (Translator), published from 1883 to 1918, which was the first journal to circulate widely in the Turco-Islamic world from the Crimea to Manchuria.

The significance of movable type in Gasprinskii's journalistic achievement as well as his pedagogical technique demands closer scrutiny, for it mirrored the Ottoman debates on the interface between typography and reading efficiency. Noteworthy is that the typeface Gasprinskii used in his educational materials as well as Terjuman was in fact very similar to that of Sinasi. Rather than sticking with the norms of naskh, Gasprinskii strung each letter side by side for the typeface of the most widely circulated journal in the Muslim world. The same principle also was at work in Gasprinskii's new pedagogical technique of breaking down the words into syllables and letters, which he published in 1884, only a year after the publication of Terjuman.Footnote 39 The movable type and the new typeface were his model for a new form of Turco-Muslim literacy, whereby reading and writing followed the patterns of typesetting.

Terjuman and the new method both expressed Gasprinskii's larger desire to unify all the Turkic-speaking Muslim lands through a literary common. His jadidism was indistinguishable from his language and script politics, as he believed that a simplified literary language among Turkic people across Eurasia was both necessary and plausible. Akin to his Russian, European, and Ottoman peers who were engaged in debates about vernacularization, Gasprinskii advocated for the invention of a new literary medium that was close to Ottoman Turkish but used shorter sentences and involved fewer Persian and Arabic words. A 19th-century romantic, he sought spiritual renovation through education and the creation of a common past with a simplified language and script. Yet, since the language that Gasprinskii's script represented was much closer to Ottoman Turkish than other vernacular speeches in Transcaucasia and Central Asia, it drew the wrath of other reformers whose ideas were diametrically opposed to Gasprinskii's ideal of inventing a common literary medium. After all, in an age of rising nationalist sentiments, why would the speakers of different Turkic languages succumb to the dominance of a simplified Ottoman Turkish?

A key figure, heretofore unexplored, in the transition from imagining a common typographic Muslim to imagining vernacular nations was Mokhammad Sultanovich Shakhtakhtinskii. A journalist by training, Shakhtakhtinskii was born in Nakhchivan and studied in Tbilisi, Petersburg, Leipzig, and Paris. Engaged in the politics of language and script at least as much as Gasprinskii, he also was a member of the International Phonetic Association, formed in Paris in 1886 by the French linguist Paul Passy.Footnote 40 Although his relationship to Akhundzade remains unclear, he was certainly informed by the latter's work on alphabet reform, as he published his first attempt at a new script in 1879 in Tbilisi, one year after Akhundzade's death in the same city.

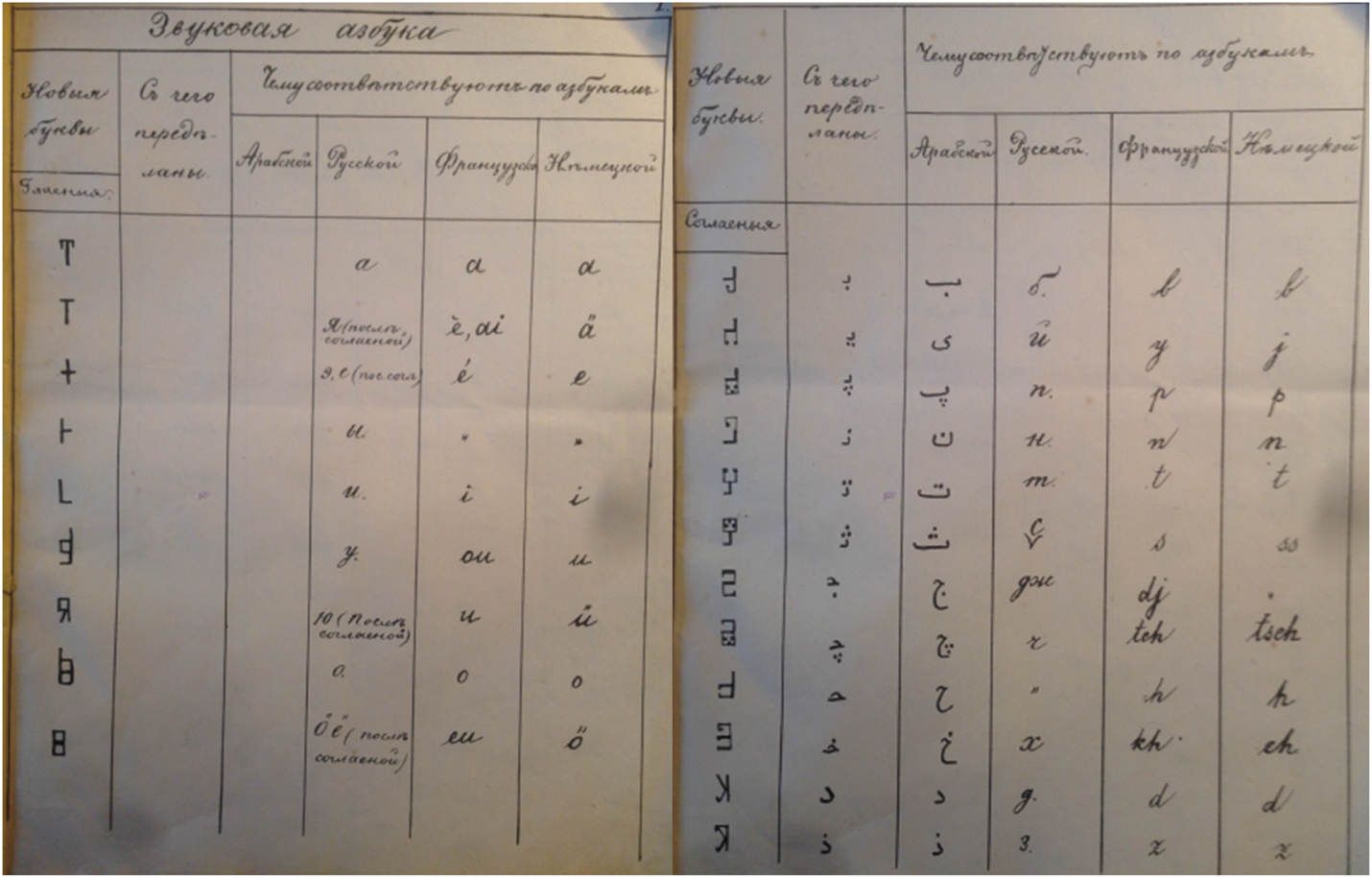

Shakhtakhtinskii's work was titled Usovershenstvovannaia Musul'manskaia Azbuka (The reformed Muslim alphabet). His attempt at innovating a reformed alphabet followed Akhundzade's proposals. This effort underwent several revisions in the following decades. “The Arabs gave the Muslim world a ‘bet,’” noted Shakhtakhtinskii sarcastically to emphasize the lack of vowels in the Arabic script, “I am presenting it an alphabet.”Footnote 41 His vowels were in principle derivations of aleph ا and waw و. He added new strokes to these two letters to make exact equivalents of nine vowels. The new consonant signs, on the other hand, were very similar to the existing Arabic letters, but additional strokes contained the dots within the limits of one letter to ascertain exact signification, just as in movable type. He then gave each letter only one sign to make sure that the alphabet could be written using separate letters, echoing the telegraphic and typographic reasonings of the earlier generation (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Shakhtakhtinskii's alphabet, with comparison to Arabic, Russian, French, and German letters and pronunciations. From Mamed Shakhtakhtinskii, Usovershenstvovannaia Musul'manskaia Azbuka: Tekmillenmis Musulman Alifbasi (Tiflis: Pech. v litogr. Tomsona, 1879), 1, 3.

The reformed Muslim alphabet, wrote Shakhtakhtinskii, was not a “national” but an “Eastern” one for all the speakers of Turco-Tatar languages, Persian, and Arabic.Footnote 42 He anticipated that it would take a long time for Muslims to get used to his alphabet, so he also invented a reformed naskh script (usovershenstvovennyi naskh’) that included the vowels that were hitherto unwritten.Footnote 43 Contrary to his expectations, however, Shakhtakhtinskii's alphabet did not achieve the recognition he hoped for, and in the following years he stepped away from his initial desire to create an “Eastern alphabet.” In the 1890s, Shakhtakhtinskii had already begun imagining an Azeri identity with a colloquial Azeri language, different from other Turkic languages. Between 1891 and 1893, while he was working as a temporary editor for the Russian journal Kaspii (The Caspian) published by Azerbaijani Turks in Baku, he started to define “Azerbaijan” and “Azerbaijanian” as a national category, and attempted to publish a journal in Azeri Turkish.Footnote 44 Finally, between 1903 and 1905, he published Sark-i Rus (The Russian East).

Sark-i Rus was the first and only challenge to Gasprinskii's Terjuman in the Russian world of Muslims. Shakhtakhtinskii was skeptical of Gasprinskii's attempt at inventing a common literary medium for Turkic speakers and noted that simplified Ottoman Turkish could not in fact serve as this medium. In defiance to Gasprinskii's call for unification, Shakhtakhtinskii had already revised his reformed alphabet and published it as The Little Azerbaijani Alphabet in 1902, a year before the publication of his journal. The letters of this “national” alphabet differed significantly from those in his 1879 proposal. They were not as perpendicular and clunky, but embodied the same principles of eliminating the dots, assigning only one sign to each letter, and inventing new signs for vowels, all for a vernacular Azerbaijani speech.Footnote 45

He did not print Sark-i Rus in his own invented alphabet, and it was clear that the language politics of Sark-i Rus were going to be different. On the one hand, as the first Turkic journal to be published after Terjuman, Shakhtakhtinskii was keen to promote it to the whole Turkic world. On the other, in the first issue of the journal he noted that due to the lack of a common literary norm he would allow all sorts of Turkic tongues to be published in his journal; he naively expected that a common language would naturally emerge out of linguistic diversity. In practice, however, the reconciliation of vernacular differences turned out to be a difficult endeavor. In 1904, for instance, he refused to publish an article from a Kyrgyz author with the explanation that it did not conform with the literary language of the Turco-Tatars.Footnote 46

Perhaps more importantly for Shakhtakhtinskii, Sark-i Rus served as a platform to display his Azerbaijani alphabet and promote vernacular language politics. In 1904, he published a reformed version of his above-mentioned alphabet, in which he assigned an Arabic number to each vowel—nine numbers for nine vowels:١ ä, ٢ а, ٣ э (e), ۴ ы, ٥ и, ٦ о, ٧ ö, ٨ у, ٩ ÿ. According to these signs, üzüm (grape) would be written as ٩ز٩م instead of اوزوم, uzun (long) as ٨ز٨ن instead of اوزون, ana (mother) as ٢ن٢ instead of انا, and so on.Footnote 47 He also changed the signs he invented for numbers, replacing them with letters. From 0 to 9, the numbers were going to be represented by the following letter signs: ـط ـحـ ز و ـه ـد ـج ب ا ٠. He did not explain the rationale behind this strange move, and the new alphabet required relearning numbers as letters and letters as numbers. The future of the Azerbaijanian alphabet looked rather complicated at best.

The person who least liked the alphabet was without a doubt Gasprinskii, for it ran against his Pan-Islamist and Pan-Turkist vision. Shakhtakhtinskii indeed drew a distinction between religious and secular education through his alphabet. Arabic script, Shakhtakhtinskii proposed, could still be used to study Islamic works, but his alphabet offered a new medium to study modern sciences and literature in vernacular tongues. The materiality of signs, in other words, sharply delineated what constituted religious and secular, traditional and modern, Islam and civilization. This arbitrary separation posed a contradiction for Gasprinskii and his followers in Terjuman, who devoted their lives to arguing for Islam as civilization. “Revered Mehemmed Aga's alphabet issue has astonished us,” wrote Gasprinskii in Terjuman, and characterized Shakhtakhtinskii's project as “childish” and “empty”:

The children of Islam are learning the Arabic alphabet to read and write in Arabic, Turkish, Persian, Urdu, and Javanese tongues. The alphabet is one. The shape of letters is one. Mehemmed Aga [Shakhtakhtinskii] is proposing the Arabic alphabet for the Koran, and his own alphabet for the rest. [Now we have] two alphabets. Isn't it better and more useful to simplify educational methods rather than inventing an alphabet that is strenuous and difficult to promote and make people accept? . . . If there is a need for a new alphabet to simplify education and civilizational progress for the Caucasian Muslims, . . . the Russian alphabet is ready for use.Footnote 48

Gasprinskii's sarcastic comment masked his frustration and fear. In reality, Shakhtakhtinskii's script proposed a powerful alternative to Gasprinskii, and the following months witnessed one of the most heated public debates about alphabet in Transcaucasia, published on the pages of Terjuman, Sark-i Rus, and Kaspii, the Russian-language journal published in Baku by Turkic intellectuals who were previous colleagues of Shakhtakhtinskii. “We wanted to have a journal in our own tongue,” wrote Kaspii, “[but] we were disillusioned by the hopes that [such a journal] would serve education and civilization. Look, Sark-i Rus started coming out. See how it serves the people.”Footnote 49 For the authors of Terjuman and Kaspii, Shakhtakhtinskii's insistence on Azeri language was dangerously vernacular and potentially detrimental to the Pan-Islamist, Pan-Turkist cause.Footnote 50

Not everyone was of the same opinion, however. In an unexpected article published in Sark-i Rus, Abdurresid Ibrahim (1857–1944), one of the leading Pan-Islamists of the day, whose transnational life from Istanbul to Tokyo has been the subject of previous scholarship, reacted against Terjuman's conservatism.Footnote 51 Portraying himself and Sark-i Rus as a “caravan,” Abdurresid Ibrahim likened Terjuman to a “brigand” (razboinik/yol basıcı). Clearly, for Ibrahim, script reform and vernacularism did not necessarily obviate the politics of Pan-Islamism, but offered a different path that did not necessarily rely on literary unity. Yet, Gasprinskii was still of the opposite opinion, for Shakhtakhtinskii's literary vision was a threat to Turco-Islamic unity under a Russian Empire. “Our time is not the time of Shaki, Shirvan or Karabakh Khanates,” wrote Gasprinskii, referring to the semi-independent Turkic khanates in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, “it is the time of Russia.”Footnote 52

Gasprinskii's words pointed to the alliance with the Russian Empire that Terjuman desired. Shakhtakhtinskii's promotion of Azeri language and identity was especially troublesome for this alliance, since Azeri-speakers composed the majority of the population in Transcaucasia.Footnote 53 Alphabet politics, in other words, were enmeshed with geopolitics, national politics, and imperial politics, and as such the debate between Terjuman and Sark-i Rus continued, as the latter printed the literary pieces of young Azeri intellectuals as well; some of these writers played important roles in the Azeri script reforms in the 1920s. When Sark-i Rus ceased publication in 1905, Shakhtakhtinskii's alphabet lost its novelty as well, but Gasprinskii was mistaken in his belief that alphabet reform was not possible in the Islamic world. The debate between Gasprinskii and Shakhtakhtinskii was in fact a breaking point that anticipated a bigger clash between divergent alphabets and the politics embedded in them as the Ottoman and Russian Empires entered their last decades.

After 1905, the debates about script, vernacularization, and secular versus Islamic knowledge were no longer confined to three journals, as dozens more commenced publication right after the Russian reforms following defeat in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05).Footnote 54 A few years later, when the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 brought down the Hamidian regime, print business developed at an unprecedented speed in the Ottoman Empire as well, as hundreds of journals and newspapers started publication. Although many of them encountered financial difficulties and ceased publication soon after, this sudden proliferation coupled with a growing technologized environment and desire for mass literacy ignited a debate about the alphabet that cut across the Ottoman Empire, the Crimea, and Transcaucasia.

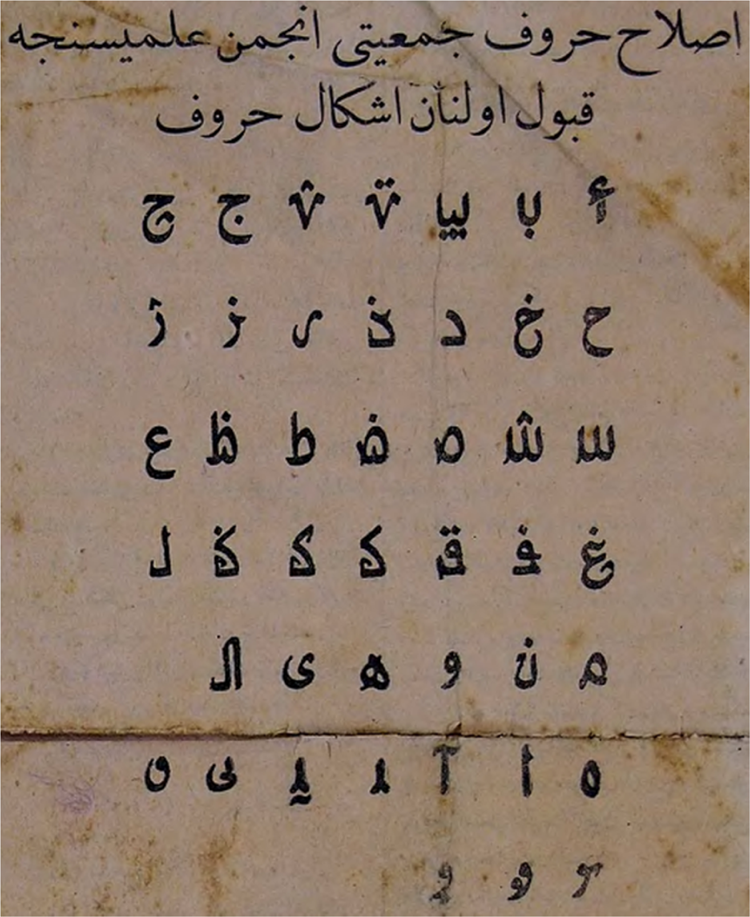

On one side of the debate in the Ottoman Empire were the reformists who pursued the path of separate letters, first proposed by Munif Pasha, Akhundzade, and Malkom Khan, and followed by Shakhtakhtinskii. Eminent Ottoman intellectuals such as Recaizade Mahmut Ekrem and Milasli Ismail Hakki established the Committee of Alphabet Reform (ıslah-ı huruf cemiyeti) in 1911. The proposals that came out of this committee dovetailed with those of Malkom Khan in that the shape of the letters were similar to Arabic letters, dots were preserved, the direction of writing was from right to left, and the letters were written separately with one sign for each letter. Milasli Ismail Hakki (1870–1939) was the leading figure promoting the “new writing” (yeni yazı) through books, newspapers, and conferences, and even printed entire books in the new script (Fig. 4).Footnote 55

Figure 4. The shapes of letters accepted by the Scientific Council of the Committee of Alphabet Reform, 1914. From Yeni Yazi 1 (1330).

These separate letters were embraced to a greater extent by Enver Pasha (1881–1922), one of the most controversial military figures in the late Ottoman Empire. As military telegraphic communications became central to imperial survival during the Great War, Enver Pasha tried to implement new writing into the telegraphic and print media. In 1914, he ordered the use of separate letters in all sorts of military communications, and even Ordu Salnamesi (The military yearbook of 1914–1915) was published using separate letters (Fig. 5).Footnote 56 However, since it required retraining the officers in a new script, it proved to be more confusing than efficient and was abandoned almost immediately after its invention.

Figure 5. Introduction to Ordu Salnamesi [The military yearbook of 1914–1915] (Istanbul: Ahmed Ihsan ve Surekasi Matbaasi, 1330).

On the other side of the debate were prominent Turkish intellectuals, such as Huseyin Cahid, Celal Nuri, and Abdullah Cevdet, who were ardent supporters of the Latin alphabet and claimed it was not only the medium of intellectual production in Europe but also more practical than inventing new signs. Although discussions about the Latin alphabet occurred in the 1860s as well, this was the first time that major intellectual figures began to openly support it. Instigators of this debate were the Albanians, who adopted the Latin alphabet in 1909–10 in an effort to claim a national identity. Subsequently, the issue of letters was highly nationalized in the 1910s, as Ottoman Turkish intellectuals claimed that the Arabic alphabet had always been for the Arabs and was never suitable for the phonetics of Turkic languages.Footnote 57 Didn’t ذ,ز and ظ all give the same z sound; and ث, س, and ص s in Turkish?Footnote 58 Arabic letters, the Turkish Latinists believed, caused an unnecessary inflation in the writing of Turkish, which was now rapidly going through a period of vernacularization.Footnote 59 The Latin alphabet, they forcefully asserted, was the only solution. The Arabic letters, in the words of Celal Nuri, were “abysmal” (berbat), “insufficient” (nâkâfi), and “unnatural” (gayri tabii) for representing Turkish.Footnote 60 (Ironically, all three adjectives were Arabic loanwords.)

Meanwhile, in Transcaucasia, the dispute that had started between Gasprinskii and Shakhtakhtinskii was never really settled. After the Russian reforms in 1905, the increasing number of Transcaucasian journals published in various languages put more pressure on the alphabet issue. On top of the ongoing debates, some intellectuals voiced their discontent with the linguistic policies of the Russian Empire. The leading satirical journal in Tbilisi, Molla Nasreddin, periodically published scathing critiques of the educational policies that prioritized instruction in the Russian language at the expense of native tongues. Written in colloquial Azeri, Molla Nasreddin portrayed the overwhelming presence of Russian language as an encroachment on the bodies of the Azeris themselves. In one drawing, it parodied the use of Russian language in education as a surgical operation on native Azeris. The right-wing monarchist Vladimir Pureshkevic and the nationalist head of the Russians in Caucasia F. F. Timoshkin were portrayed cutting off the tongue of an Azeri man and sewing on a new Russian one instead. In another cartoon, an Azeri Turk twisting in pain was stuffed with Russian, Persian, and Arabic tongues while he exclaimed, “Dear brothers, I already have a tongue so why are you trying to put others into my mouth!” (Fig. 6)

Figure 6. Sewing Russian tongues in schools; an Azeri Turk stuffed with tongues. From Slavs and Tatars (eds.), Molla Nasreddin: The Magazine That Would've Could've Should've (Zurich: JRP-Ringier, 2011), 196–97.

Azeri speech, according to the nationalist intelligentsia, was under attack not only by Russian, Persian, and Arabic, but even Ottoman Turkish. Firidun Kocharli (1863–1920), a Latinist himself who had earlier published in Sark-i Rus, called the Ottomanization of Azerbaijan a “national treason” and even likened it to Il'minskii's Russification project.Footnote 61 For the Azeri Latinists, like the Turkish nationalists across the border, a new script was the concrete medium with which to signify linguistic sovereignty by distinguishing the Azeri tongue from Arabic, Persian, Russian, and Ottoman Turkish. And with the fall of the Russian Empire in 1917, the Latin alphabet was the strongest alternative to existing script proposals.

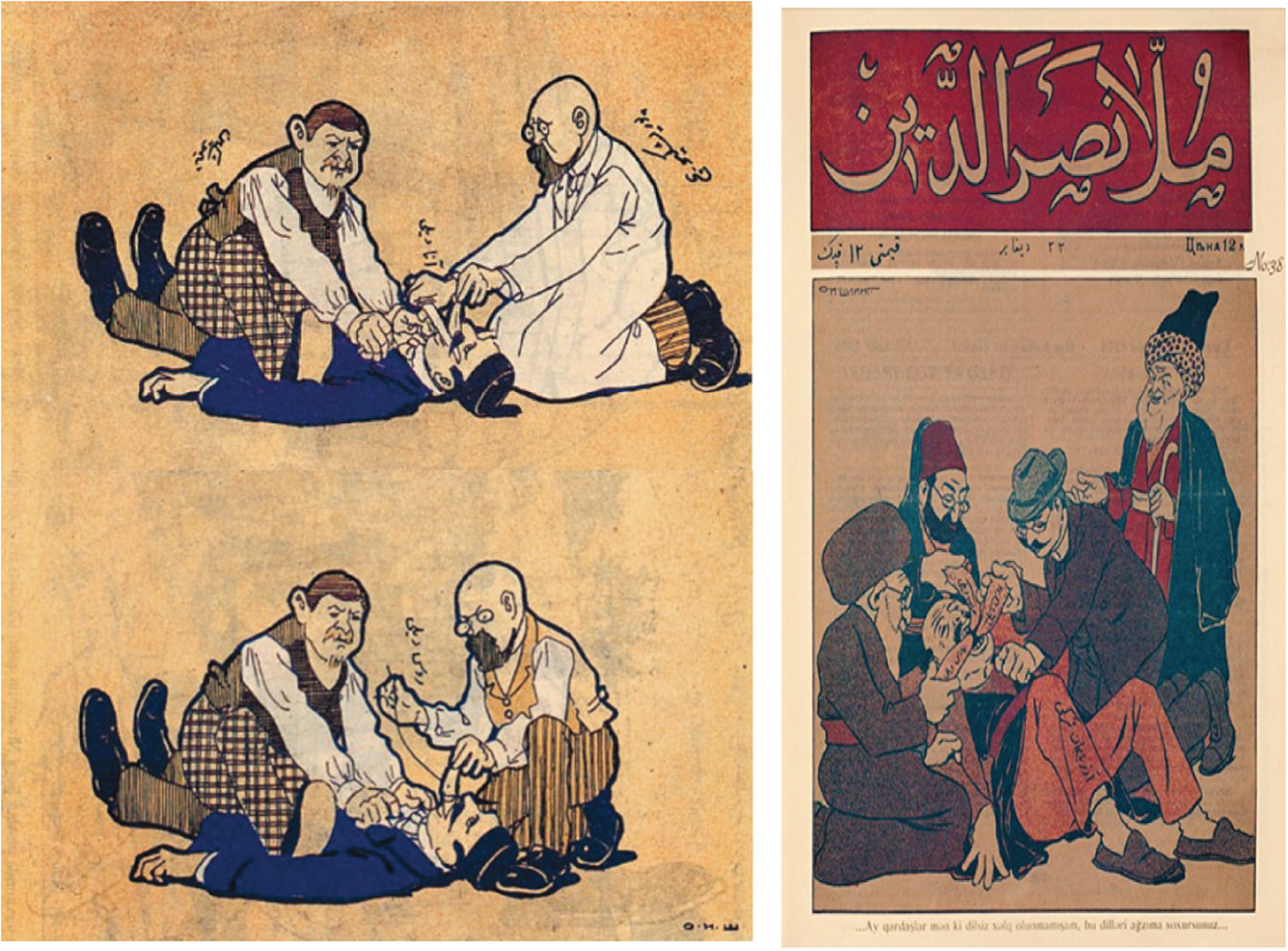

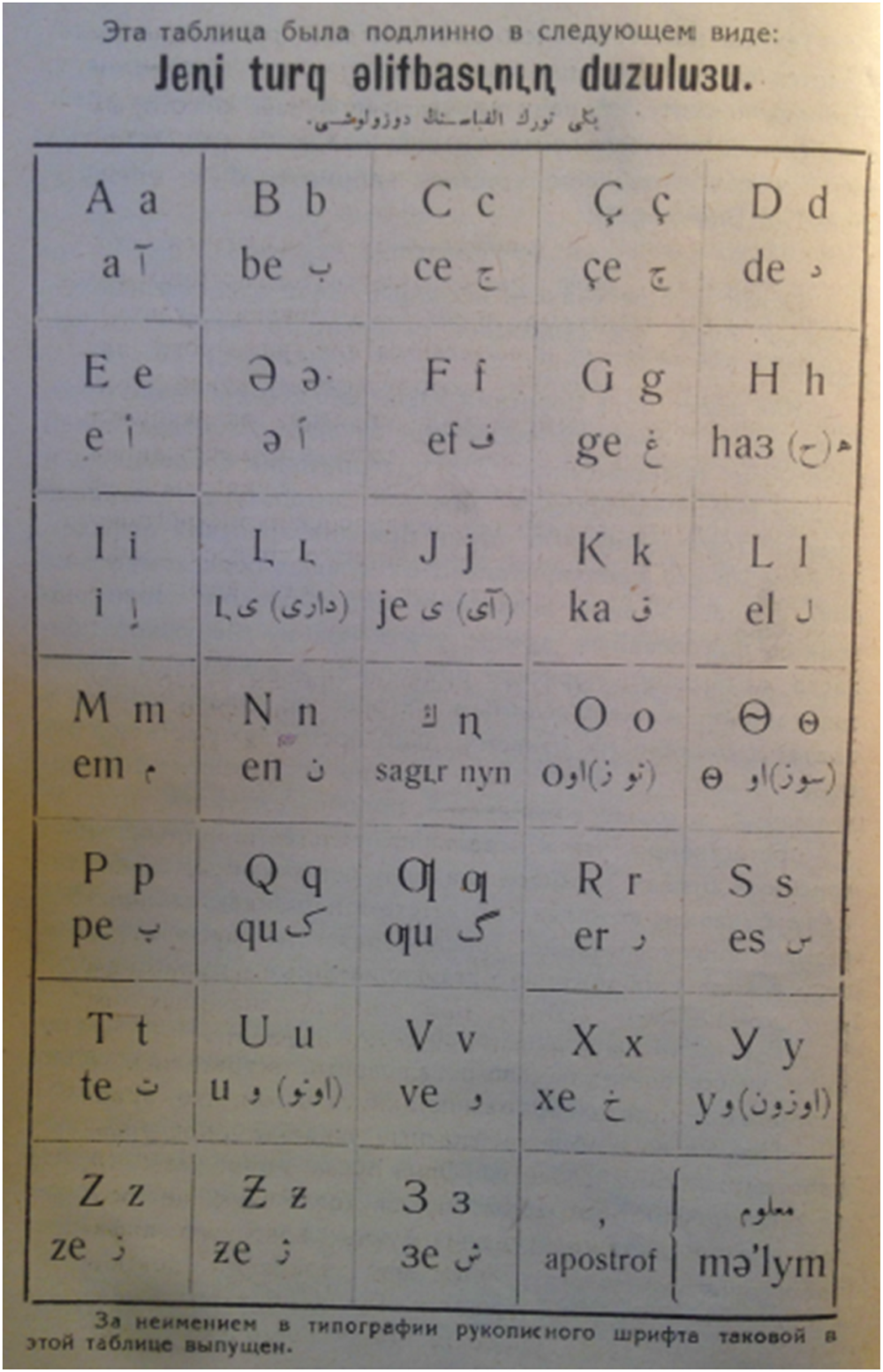

The first latinized Azeri alphabet, known as the last Turkic alphabet, was published in 1919 in Baku after the establishment of the short-lived Democratic Azerbaijani Republic (DAR; 1918–21).Footnote 62 The DAR was formed immediately after the Bolshevik Revolution, which brought an end to Russian rule in Transcaucasia and forced many of the reformers to move from Tbilisi to Baku, turning the latter city into the new frontier of latinization. Only a year later, the DAR surrendered to the Bolshevik forces in what was in effect an invasion, but the dispute between “Arabists” and “Latinists” persisted in Baku. The Latinists established the Komitet Novogo Tiurkskogo Alfavita (Committee of the New Turkic Alphabet) in which Shakhtakhtinskii was just one among many who fought for a new Latin alphabet. Some of the members of this committee were later present at the First All-Union Turcology Congress in 1926.Footnote 63 Indeed, the head of the committee was Samed Aga Agamalioglu (1867–1930), who later became the leading figure of the Soviet Union's latinization movement. The committee introduced the “New Turkic Alphabet” in 1922 and started publishing the monthly journal Jeni Jol (The new way) that promoted it (Fig. 7). Agamalioglu then took a quick trip to Moscow to receive Lenin's blessing, who, according to Agamalioglu's account, called latinization the “revolution in the East” (eto revoliutsiia na vostoke).Footnote 64 On 20 October 1923 the New Turkic Alphabet was declared to be on par with the Arabic alphabet in Azerbaijan, and it was exported to Georgia, Armenia, Turkmenistan, and the Crimea. On 27 June 1924 it was finally recognized as the official alphabet of the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic.Footnote 65

Figure 7. The New Turkic Alphabet in Azerbaijan, 1922. From Agazade, Istoriia Vozniknoveniia Novogo Tiurkskogo Alfavita v ASSR, s 1922 po 1925 god (Baku: Komiteta po Provedeniiu Novogo Tiurkskogo Alfavita, 1926), 10.

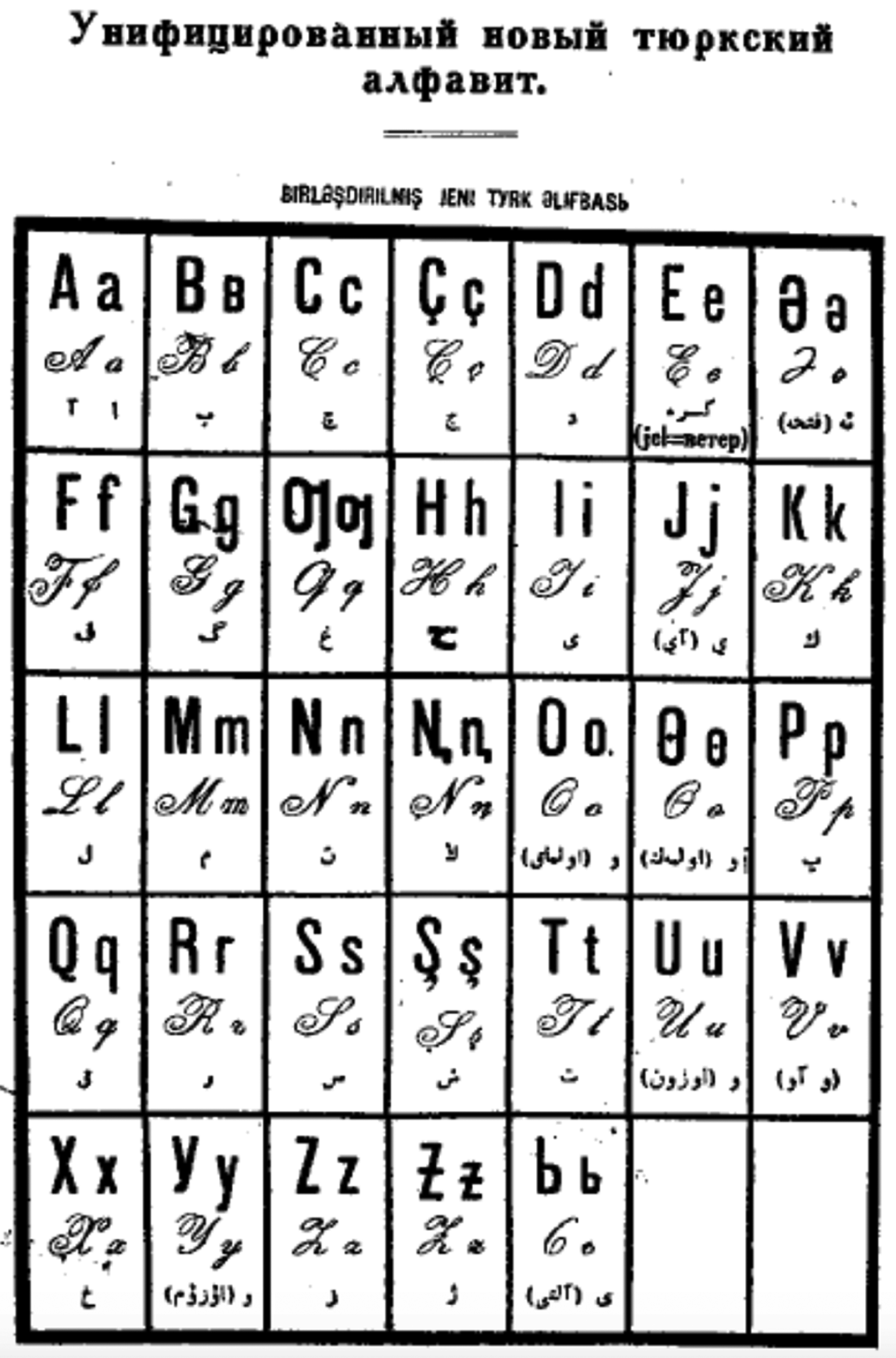

The transition of the Azeris from an Arabic to a Latin alphabet in fact marked the end of a long period of debates and the beginning of a new one that transcended the Turkic world. In 1926, at the First All-Union Turcology Congress, representatives from all over the Soviet Union convened in Baku and decided to turn latinization into an internationalist project to invent a new socialist civilization within and outside of its borders. Keeping intact most of the letters of the New Turkic Alphabet, the Unified New Turkic Alphabet (UNTA) was devised in 1928 and exported to non-Turkic languages as well, such as Kurdish, Mongolian, Persian, and Chinese (Fig. 8). Meanwhile, the Republic of Turkey, emerging from a similar period of imperial disintegration, also defined the Latin alphabet as a revolution, albeit not a socialist one. Although they closely watched the alphabet revolutions in the USSR and remained in contact with Soviet linguists, the Turkish political leaders put a distance between the two movements. In 1928, when the New Turkish Alphabet was officially declared, its letters were noticeably different from the Unified New Turkic Alphabet of the USSR: ь of the UNTA was replaced with an ı in Turkish, ƣ with a ğ, c with a ç, ɵ with an ö, y with a ü, and so on.

Figure 8. The Unified New Turkic Alphabet. From Kul'tura I Pis'mennost’ Vostoka, kniga vtoroia (Baku: Izdanie VTsK NTA, 1928).

Conclusion

Although the histories of the alphabet in Turkey and the USSR diverged considerably during the rest of the 20th century, they were intricately linked to one another until the 1920s. The recognition of their common roots demands a historical reconceptualization of the Russo-Ottoman space from the second half of the 19th century onward, during which time the intellectual borders of the empires were highly permeable due the development of new media technologies. What primarily connected Transcaucasian, Crimean, Ottoman, and even Persian alphabet reformers was neither their calls for reform nor their trans-imperial peripatetic travels, but the challenges they faced from the techno-political conditions and new media ecology of the 19th century.

A transnational approach that highlights the significance of new media technologies and their material and immaterial ramifications compels us to rethink the alphabet reforms as part of a global communications revolution in the 19th and 20th centuries, to which non-Roman scripts across the world—from Chinese characters to the Arabic alphabet—had to adapt. It is true that telegraphy and movable metal type allowed an increased circulation of information, giving birth to new political imaginations, but of equal importance were the challenges they posed and the new epistemologies of writing they imposed, which had a lasting impact on language politics across the world. The history of alphabet reforms was, in short, the product of a changing mode of knowledge production that challenged existing orders of language and writing. As such, alphabet revolutions of the 19th and 20th centuries were not merely outcomes of political transformations; they instead stood at the techno-political forefront of global communications and information histories.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted with the support of the Social Science Research Council, American Council of Learned Societies, and Columbia University Harriman Institute. I would like to thank John Chen, Marwa Elshakry, Adrien Zakar, Umit Firat Acikgoz, and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.