On 17 August 1956, five months after Morocco gained independence from France, the Moroccan national icon Samy Elmaghribi (Sami al-Maghribi, Samy the Moroccan) wrote his brother Simon Amzallag in Marseilles. Simon, watching the shifting Moroccan political climate from afar, had grown concerned about how his brother was faring as the country's best-known recording artist and its most prominent Jewish cultural figure. The brothers were usually punctilious about their correspondence. After all, the two had a transnational business to run. The affairs of Samyphone, Samy Elmaghribi's independent Moroccan record label, required near daily back and forth between its Casablanca headquarters and Marseilles, where Simon and his family, like so many other Moroccan Jews, had dwelled since 1949.Footnote 1 But Elmaghribi had grown quiet of late.

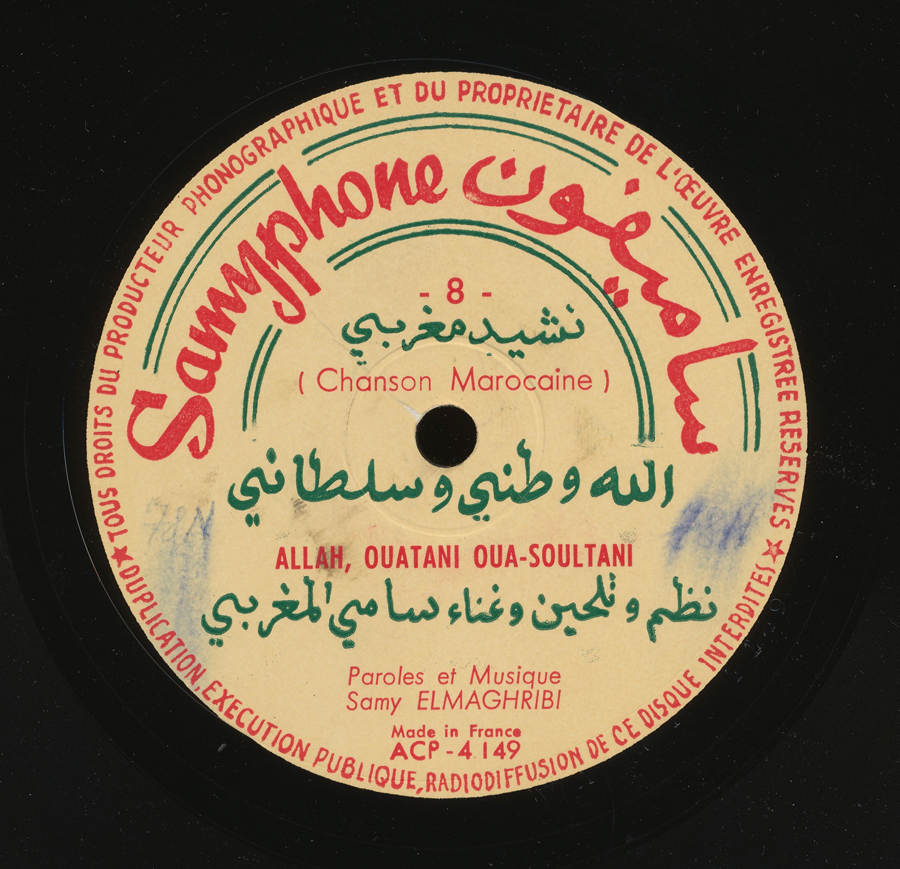

In his August 1956 letter to Simon, Elmaghribi apologized for the delay but admitted there was little he could do given the situation. “On three occasions over the last three weeks, His Highness has needed me and my orchestra to perform at soirées at which Salim Halali and his orchestra were also working,” he explained, making reference to the Algerian Jewish artist now settled in Morocco.Footnote 2 It seemed that Sultan Mohamed ben Youssef, the Moroccan sovereign, could hardly get enough of Elmaghribi. Nor could Crown Prince Hassan or his brothers. “My song Allah Ouatani oua Soultani [Allah watani wa-sultani; God, My Country, and My Sultan],” Elmaghribi wrote of his wildly successful record, “was happily danced to by the princes and their guests” at those recent royal events. There was no need to worry, he assured his brother. He and his brand of patriotic music, which celebrated the Moroccan nation in expansive terms, were in constant demand from both the makhzan (central Moroccan government) and the Moroccan Royal Armed Forces. “The Guard and Royal Army are learning to play it as well,” he added of “Allah, Ouatani oua Soultani,” “in order to perform my march … at every possible occasion.” In some ways, the military was behind the times. Ordinary Moroccans, Algerians over the border, and North Africans on the other side of the Mediterranean had already committed the song to memory. As Simon wrote Elmaghribi some ten days later, the record was “causing a furor here [in France] and in the Arab world.” Audiences from Marseilles to Algiers were finding inspiration in Elmaghribi and the sounds of his nationalism.Footnote 3

To date, Samy Elmaghribi has eluded the historiography of Moroccan nationalism.Footnote 4 In fact, most musicians and most music have. Instead, that literature has focused almost exclusively on the anti-colonial nationalist Hizb al-Istiqlal (Independence Party). In doing so, as Susan Gilson Miller has argued, Moroccan historiography remains bound up in the Istiqlal's teleological reading of the culture of nationalism in Morocco.Footnote 5 That self-interested approach, as Fadma Ait Mous has written, rests upon the notion of a “diffusionist model,” whereby an elitist, Pan-Arabist, and reformist Islam–oriented nationalism is understood to have spread from an “original core” to a single, undifferentiated periphery. This has meant that “the historiography of Moroccan nationalism has long privileged the macro-scale, thus masking the socio-political processes and networks of actors at work at the micro-level.” The result is a “stereotyped history of Moroccan nationalism” that is “linear and monolithic.”Footnote 6

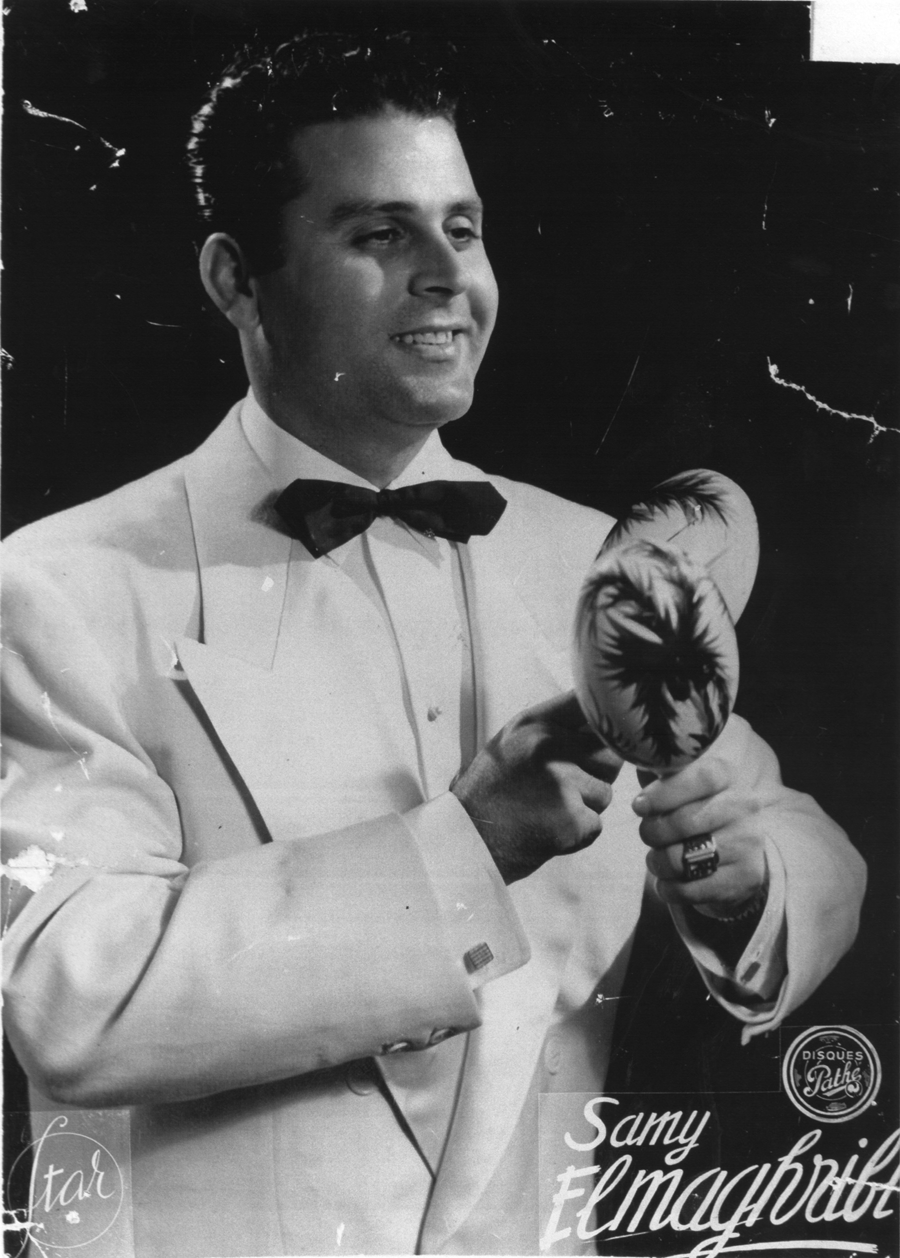

FIGURE 1. Samy Elmaghribi promotional poster for Pathé, c. 1951. (Courtesy of Samy Elmaghribi Archive).

Much as recent scholarship has uncovered the critically important informal networks and spaces deftly put to use by Istiqlal leaders in order to achieve their national aims, this essay demonstrates that still other Moroccans performed and practiced a capacious form of nationalism in venues of a different, more popular sort.Footnote 7 Among them was Elmaghribi, a Moroccan superstar with few equals in the 1950s, who espoused a nationalism centered on both the Moroccan monarch and the Moroccan people that was widely disseminated on radio, in concert, and by way of disc. That Moroccan nationalism resembled what might be called “Moroccanism.” And Elmaghribi's audiences, from the royal palace to the urban Jewish and Muslim working classes, had little trouble singing along.

This article suggests that a focus on musical culture makes audible a more nuanced sense of Moroccan nationalism and its multiplicities at the mid-20th century than previously considered. In this manner, it provides evidence for the popularity of unmarked nationalist forms like Moroccanism, which placed an emboldened Sultan Mohamed ben Youssef at its center, imagined the nation beyond the narrow ethno-religious confines envisaged by the Istiqlal, and enjoyed wide currency among ordinary Moroccan Muslims and Jews.Footnote 8 Despite a lack of affiliation to any one party, Elmaghribi was considered no less nationalist at the time by the royal palace (which hosted him frequently and on the most important of national holidays), the French Residency (which kept tabs on the performer during the final years of the protectorate), or his city-dwelling Muslim and Jewish fans.

In such a fashion, this article aims to enter into conversation with scholarship on nationalism, popular culture, and mass consumption in Egypt, which has given voice to more inclusive interpretations of national belonging that prevailed earlier in the 20th century. Ziad Fahmy, for example, has demonstrated how the nationalism of “ordinary Egyptians” was shaped by mass culture, including music, prior to and during the 1919 revolution.Footnote 9 Nancy Y. Reynolds has done much the same by concentrating on sartorial habits, department stores, and habits of consumption, but during the interwar years.Footnote 10 Both Fahmy and Reynolds conclude, respectively, that through modes of popular entertainment and fashion à la mode Egyptians of a variety of ethno-religious backgrounds learned to identify as a national community and, at the same time, with a territorial form of Egyptian nationalism that tended to elide the very divisions that would later become the hallmark of anti-colonial nationalist movements. As Reynolds writes:

Egyptian belonging thus took many forms in this era, in part because the dominant strain of Egyptian nationalism in the 1920s and early 1930s, Egyptianism, was a territorial nationalism predicated on a common connection to place rather than more integral forms of supranational identity based in a shared ethnicity, language, or religion (Arabism, Islamism, neofascism, etc.) that expanded their institutional base in the 1930s and 1940s.Footnote 11

Thus, the worlds of popular culture and consumption reveal a very real form of Egyptian nationalism that once spoke to many. So too, this article contends, does music offer an echo of a parallel variant of Moroccan nationalism that existed past its Egyptian analogue.

That Elmaghribi was Jewish should not be overlooked by scholars. That fact, along with the high profile careers of other North African Jewish musicians at the time, points to the energetic participation of Jews in a mainstream variant of Moroccan nationalism. In such a way, this article engages with work by Orit Bashkin (Iraq), Lior Sternfeld (Iran), Alma Heckman (Morocco), and Pierre-Jean Le Foll-Luciani (Algeria), who have shown that Jews actively partook in nation-building projects and anti-colonial nationalism across the Middle East and North Africa in the 20th century, despite their absence in nationalist historiography.Footnote 12 In these studies, however, emphasis has been placed on leftists and communists but not always on the vast middle. In contrast, Elmaghribi offers a case study in Jewish engagement with a broad-based nationalism embraced by a large swath of the urban Moroccan public.

Elmaghribi's rise to national prominence provides for additional rethinking of Jewish historiography in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. The arc of his career, for example, launched in the year of Israel's establishment (1948) and reaching its apex in the year of Moroccan independence (1956), corresponds to a period that has mostly been framed in terms of Jewish exodus and exile from Morocco.Footnote 13 This is not without justification given that push and pull factors reduced the Moroccan Jewish community from a postwar peak of approximately 250,000 souls to 160,000 by 1960. But as a result the question of how Jews lived during those years has been neglected in favor of detailing how Jews left.Footnote 14 In turn, voices like those of Elmaghribi and the two-thirds of Moroccan Jewry that remained in country through Moroccan independence have been silenced. As treatment of the celebrity musician will make clear, not only did Jews have a place in Morocco at the dawn of a new political era, but so too did a highly visible minority actively shape its national sounds from center stage.

Finally, the making of Samy Elmaghribi during the final years of colonialism and his continued success through the early post-independence period provides for more than a reconsideration of post-1948 life in Morocco for Jews. By bridging the divide between colony and independent nation, his stardom offers new insights into the dynamics of decolonization.Footnote 15 Close study of the trajectory of Elmaghribi, as both a Moroccan Jew and musician, provides for a better understanding of the sociopolitical history of the Maghrib itself.

MUSIC AND NATIONALISM IN MOROCCO

In the immediate postwar years, the musical marketplace in Morocco was crowded. As an emerging artist, Salomon “Samy” Amzallag (1922–2008) would be forced to contend with Moroccan Jewish recording stars like Zohra El Fassia;Footnote 16 Moroccan Muslim musical innovators like Mohamed Fouiteh, Ahmed Jabrane, and Abdelwahab Agoumi;Footnote 17 visiting acts of considerable repute from Tunisia and Algeria;Footnote 18 and those of regional renown like Farid El Atrache.Footnote 19 Amzallag did so under the stage name of Samy Elmaghribi.

Almost all of these musicians would grace Rabat's Cinéma Royal, one of a number of concert halls and movie theaters where the nationalist politics of the era were duly performed. Those stage performances would become especially strident in the aftermath of the 1944 founding of the Hizb al-Istiqlal, an anti-colonial nationalist party that called for Moroccan independence from France “within the framework of a constitutional-democratic monarchy” under the leadership of Sultan Mohamed ben Youssef.Footnote 20 On 30 August 1946, for example, musician Abdelwahab Agoumi opened his concert at the Cinéma Royal by “glorifying HM [His Majesty] the Sultan,” as P. Feraud, head of regional security for Rabat, noted anxiously in a confidential report. Among the five hundred that attended the Agoumi concert in Rabat, Feraud's agents identified them as “for the most part, nationalists.”Footnote 21 But if Agoumi's praise for the sultan could be forgiven by Feraud––His Majesty did, after all, theoretically govern alongside the French Resident General––the musician's short speech in praise of Istiqlal leader ʿAllal al-Fasi had crossed a line.Footnote 22

Nevertheless, for a growing percentage of the Moroccan public, the sultan and the Istiqlal were already one and the same. Thus, Agoumi, after invoking al-Fasi, concluded the evening by asking the audience to rise as he performed “the Sultan's hymn,” an anthem of his own creation. As he left the stage, Agoumi prepared for a trip to Egypt. “The cost of this sojourn in Egypt,” Feraud indicated, “will be paid for by the Istiqlal party.” The Istiqlal's goals for Agoumi in Egypt were by no means innocent. From Cairo, he would spread “[Moroccan] propaganda in the Middle East” and work toward “the modernization of Andalusian music in Morocco.” As well as a music industry teeming with talent, Amzallag would need to navigate a changing political climate.

Yet where Jews fit into the nationalist politics of the Istiqlal was unclear at best.Footnote 23 That lack of clarity was made ever more opaque by some in the party leadership, who defined their drive to independence in terms that favored Arabo-Islamic identity over formulations that might account for Moroccan Jews and Berbers. As Jonathan Wyrtzen has argued, that narrow reading of the contours of Moroccan national belonging was a product of “the colonial political field,” rather than constituting “evidence of long-standing national unity” that predated the protectorate.Footnote 24 And as Nancy Y. Reynolds has written with regard to Egypt, both colonial domination and nationalist revolt relied on such “neat, binary categories.”Footnote 25 At the most emblematic level, the Istiqlal aligned itself with Pan-Arabism, which tended to exclude Moroccans who did not identify as Arab. In 1947 alone, the Istiqlal established a branch of the party in Egypt with the telling name of the Office of the Arab Maghrib, while ʿAllal al-Fasi published a nationalist text, which he titled The Independence Movements in the Arab Maghrib.Footnote 26 That same year, in which the United Nations also voted to partition Palestine, and stretching into the 1950s the Istiqlal launched a number of anti-Zionist boycott campaigns, which frequently targeted Jews without regard for their actual political sympathies.Footnote 27 Music was not immune.

In fact, so wide-ranging was the Istiqlal anti-Zionist effort that Farid El Atrache, Egyptian superstar of Syrian Druze origin, soon fell within its purview. When El Atrache, dancer Samia Gamal, and an ensemble of fifteen Egyptian actors and musicians arrived in Morocco for a series of performances in early 1951, French regional security in Rabat informed the French protectorate's director of the interior that, “it is being reported that the Istiqlal party is launching an active propaganda campaign in the Muslim milieu against the Egyptian theatrical troupe.”Footnote 28 Intelligence reports identified two driving forces behind the anti–El Atrache effort, both of which revolved around questions of Jewishness, not Zionism. First, Istiqlal chatter-cum-protest came to focus on Egyptian Jewish tour manager David Salama, who had accompanied his client, El Atrache to Morocco. According to a report written on 1 February 1951, the manager's mere presence led to the Istiqlal “reproaching actors for having worked with the Jewish impresario SALAMA.”Footnote 29 Second, and in similarly curious fashion, regional security noted on 8 February 1951 that “there is a widespread rumor in Casablanca that the Egyptian actor Farid El Atrache is of Jewish origin.”Footnote 30 Despite the effort, the Istiqlal's attempted boycott of Farid El Atrache fell flat. Each of his concerts overflowed with enthusiastic fans. Moroccan Jews, whose national loyalty had been questioned in the process, behaved exactly like their Muslim compatriots. On 5 February 1951, some three hundred of them packed Casablanca's Cinéma Vox to see the Syro-Egyptian star, who had lately added a song about Marrakesh to his repertoire. El Atrache, as usual, was steadfast in his praise of the sultan.Footnote 31

Into this maelstrom stepped the young Moroccan Jewish artist Salomon “Samy” Amzallag. He too was a Moroccan nationalist, but of a very different sort.

BECOMING SAMY ELMAGHRIBI

In April 1948, the twenty-six-year-old Amzallag was tapped by L. A. Vadrot, the local head of Pathé, the most important label in North Africa, to make a series of recordings. Since childhood, he had been singing––first at the Sabbath table in Safi and then Rabat, later in the synagogue, and more recently for a growing number of admirers. In the last year, Amzallag had abandoned a job in accounting to dedicate himself to music. His talent was quickly discovered. Vadrot, though, did not just intend for the young Moroccan Jewish musician to be but one artist among many. Rather, he believed him to be the future of Pathé in North Africa.Footnote 32 Vadrot made that clear in his 30 April 1948 letter to the civil controller of Casablanca requesting permission for Amzallag to travel to Paris to record. He described “Mr. Salomon Amzallag,” as “indispensible” to the effort of “revitalizing our Arab catalogue.”Footnote 33 In 1948, then, just as nationalist parties like the Istiqlal were circumscribing Moroccan and Arab identity in ways that could exclude Jews, Pathé saw little issue with a Moroccan Jew serving as anchor to their “Arab catalogue.” And just as 1948 has often been regarded by scholars of Morocco as the beginning of the end of Moroccan Jews in-situ, as hundreds began to depart, a Moroccan Jew was beginning his meteoric ascent to the national spotlight. He did so alongside a number of his coreligionists.

When Amzallag exited Pathé’s Paris studios on 13 and 14 September 1948, he did so under the stage name of “Samy Elmoghrabi” (Samy the Moroccan).Footnote 34 By choosing such an appellation, he made explicit his identification with the Moroccan nation.Footnote 35 The sixteen sides that Elmoghrabi recorded in late 1948 already hinted at his brand of nationalism. Like other Moroccan musicians at the time, some of his first records included interpretations of modern Egyptian music, some of which had a Pan-Arabist quality to them.Footnote 36 On still other records, Elmoghrabi also drew on Egyptian modes but now blended them with up-tempo Andalusian rhythms and Latin genres like tango and paso doble to produce an emerging brand of modern Moroccan music that was popular and often patriotic. It was also quickly regarded as a national form.Footnote 37 Typical was Elmoghrabi's “Chebban Erryada” (Shubban al-Riyada; Youth of Sport), in which he praised the athletic prowess of young Moroccans while accompanied by music that was at once in 6/8 rhythm and, at the same time, a march.Footnote 38 Moroccans responded positively. The same was true for his records “Hobb El Bnet” (Hubb al-Banat; Love of Girls) and “Gitana” (Khitana; Gypsy Woman), which were overnight sensations. Pathé’s Vadrot had not been wrong in trusting the label's future to Amzallag.

At the moment that Samy Elmoghrabi became Samy Elmaghribi, many Moroccan Jews were departing their homeland for France, the State of Israel, and the Americas. Among them were Elmaghribi's siblings Simon and Denise, both of whom settled in Marseilles toward the end of 1949. Just as scholars have tended to portray Jewish departure from Morocco after the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 in the aggregate and as unidirectional and discrete, the Amzallag family journey sheds light on the personal and multidirectional nature of exile-as-process in the middle of 20th century.Footnote 39 It was not the case that the entire Amzallag family had left Morocco by 1949, and yet it was certainly true that the absence of his brother and sister weighed heavily on Elmaghribi. Nor was it clear that Simon's departure was permanent––at least initially. Writing to Elmaghribi from Marseilles on December 23, 1949, Simon expressed great joy at his younger brother's burgeoning career in Morocco while informing him that he had “completely abandoned the project to return there to live.”Footnote 40 Tens of thousands of others, of course, remained. They took refuge in Elmaghribi's music and its possibilities.

As Simon and Denise adjusted to life in France, their brother was beginning to make a name for himself on both sides of the Mediterranean. On 11 September 1949, Elmaghribi debuted on the evening radio program La Gazette de Paris on Radiodiffusion et Télévision Françaises (RTF).Footnote 41 By October 1949, a year since debuting with Pathé, Elmaghribi had given three concerts on Radio Maroc.Footnote 42 Later that month, he made another series of records for Pathé in Paris.Footnote 43 By November 1949, Elmaghribi premiered on the Arabic-language broadcast of RTF.Footnote 44 At year's end, he could claim growing Moroccan audiences in France and Morocco. He even bridged the gap. In December 1949, Elmaghribi served as in-house entertainment on the vessel Koutoubia as it sailed between Marseilles and Casablanca and returned him home.Footnote 45

Although Elmaghribi's sojourn abroad was for little more than business, hundreds of Moroccan Jews who had emigrated in the late 1940s and early 1950s returned to Morocco as well. Between 1949 and 1953, 2,466 Moroccan Jews officially re-established themselves in Morocco after having tried their hand at life in Israel.Footnote 46 Others did the same but returned from France. In addition, many Algerian Jews made their way to Morocco during the same period. Salim Halali, the renowned Algerian recording artist who had survived the horrors of the Holocaust while hiding in Paris, was among them.Footnote 47 Why Halali chose to set down roots in the cultural capital of Casablanca is unclear, although the war and its devastation likely played a role in his decision to leave France. Whatever the reason, he could be certain that he already had an audience there. Just a few years prior, in the midst of the Second World War, Halali could be heard across Morocco despite his own silencing in the Nazi-occupied French capital. His very popular discs––purchased in record stores and frequently played on radio––were deemed so politically subversive that one such Halali record was banned from sale and play in Morocco in July 1942.Footnote 48 Despite the ban, Halali's brazen “Arjaâ Lebladek” (Arjaʿ l-Biladak; Return to Your Country), which was addressed to Algerian workers in France, never seemed to disappear completely.Footnote 49 Nor did Halali.

In August 1948, the head of the diplomatic office in the French Residency demanded that Radio Tanger International, an American-run radio station in Tangier, cease its play of the still-banned “Arjaâ Lebladek.” According to a confidential report filed by the political section of the ministry of interior, Halali's record was being “broadcast three or four times a day,” having been repeatedly “requested by certain listeners in our zone” and adopted by Moroccan nationalists.Footnote 50 In 1949, months after the record was again taken off the air, Halali arrived in Casablanca. There he established Le Coq d'Or, a cabaret on Rue du Consulat d'Angleterre in the heart of Casablanca's Jewish quarter. Elmaghribi and other pillars of modern Moroccan music would soon pass through its doors.

REVOLUTIONARY MUSIC

By the early 1950s, Moroccans had begun to imagine independence.Footnote 51 For many, it sounded like Elmaghribi. In tandem with a national revolution waged by the Istiqlal in global forums like the United Nations, Elmaghribi was sating Moroccans back home with what he called his “sensational revolution in Oriental music.”Footnote 52 And it could be heard nearly everywhere: from the concert hall to the radio and from the royal palace to the marketplace. His revolutionary music celebrated urban and rural, north and south, while making no distinction between Arab or Berber nor Muslim or Jew. All were Moroccan. But if his nationalism––Moroccanism––was different from that of the Istiqlal, it was no less nationalist. On the country's largest stages and on its most symbolic ones, Elmaghribi donned the national colors, toured alongside Muslims, and sang of and for the nation. In each setting where his music was performed, Elmaghribi's audiences learned to perform his inclusive brand of Moroccan nationalism as well.

“The echoes of your brilliant success,” Simon wrote to his brother from Marseilles on 17 February 1950, “have reached me all the way up here.”Footnote 53 By early 1950, Elmaghribi's success was so compelling that Simon encouraged him to remain in Morocco instead of joining him on a permanent basis in Marseilles. In late summer 1950, Elmaghribi, whose music was already broadcast with regularity on Radio Maroc, embarked on his first concert tour of Morocco. “Les Samy's Boys,” his six-piece orchestra, accompanied him on stops that included Rabat, Fez, and Mazagan (El Jadida).

FIGURE 2. Elmaghribi's original ensemble the “Samy's Boys,” c. early 1950s. The musicians helped produce the big band, swing, and Latin sounds that characterized some of his earliest successes. (Courtesy of Samy Elmaghribi Archive).

In the promotional materials for his 1950 tour, Elmaghribi demonstrated the independent style, sartorial confidence, and musical modernism that helped set him apart. The poster for his 9 September 1950 concert in Mazagan, for instance, which adorned kiosks throughout the city, first carried his slogan of a “revolution in Oriental music.”Footnote 54 It also included a large photo of a dapper, perfectly coiffed Elmaghribi, bespoke in white suit at the microphone, surrounded by Les Samy's Boys. With all eyes fixed on their bandleader, his orchestra practically swooned. “For the first time in Morocco,” the poster announced in French, “Samy Elmaghribi and his dynamic ensemble, ‘Les Samy [sic] Boys’ (before their departure for Paris),” were to appear. Catch him for a hometown show, the marketing suggested, before the rest of the world grabbed hold of him. And with reasonably priced tickets, Moroccan audiences could afford his revolution. That rebellion of “modern music and song” was true to form and included such styles as “Franco-Arabic, flamenco, Egyptian, Algerian, Tunisian, [and] Moroccan.”

As his advertisements promised, Elmaghribi's early set lists included music that ranged across the Maghrib and the Middle East, across styles, and across languages. Much of it was unlike anything Moroccans had heard before. Emblematic were songs like his breakout record “Luna Lunera,” a bolero written by the Cuban Tony Fergo, which Elmaghribi translated into Arabic while maintaining certain whole verses in Spanish. But it was one disc in particular that ingratiated Elmaghribi to a wide swath of the Moroccan public: “Loucane Elmlayïn” (Lukan al-Milayin; If I Had Millions). Perhaps it was its aspirational quality that endeared the singer and the song so.

In “Loucane Elmlayïn,” Elmaghribi dared dream the impossible so long as French rule persisted in Morocco. In the song, which again employed the 6/8 berouali rhythm, Elmaghribi articulated the lengths he would go to pursue the love of his life. “Ay ay ay, if only I had millions,” he sang, “I know what I would do with them. / On trains … in planes, I would cross oceans and traverse mountains that reach the heavens,” in order to find the one he had been searching for. But if Moroccan audiences gravitated toward “Loucane Elmlayïn,” they would have also relished in its folly. Traveling by train and plane in order to reach, “the [Middle] East and Lebanon, India and Yemen,” as Elmaghribi crooned, would have been recognized as pure fantasy when considering that the majority of Moroccans needed permission to travel abroad. And yet, the realm of possibility that was part and parcel of the appeal of a song like “Loucane Elmlayïn” would also have suddenly seemed within grasp as Moroccans gained ground in their national struggle. Elmaghribi's music was providing Moroccans with a taste of their possible future.

With music like “Loucane Elmlayïn,” Elmaghribi was increasingly in demand among an ever-widening circle of Moroccan fans. Although his first concert tour had already attracted a multi-confessional Moroccan audience, he actively cultivated Jewish-Muslim diversity for his second. But even as those spectators in 1950 included Muslims and Jews––and among them the political establishment, the well-heeled, and the working class––his earliest promotional materials were printed only in French. By mid-1951, however, Elmaghribi began promoting his shows with Arabic-language concert posters and featuring highly regarded Muslim musicians on the bill. Just a few months later, Elmaghribi could report the following to Simon:

My success in Morocco is certainly immense and I am recognized and surrounded very quickly no matter which city I'm in, in Casa, [cities] small and big, everyone points out Samy with their finger, with a smile … the great success of the day remains the Song of the Millions [“Loucane Elmlayïn”] (my creation) in Arabic of which you have the record and which is hummed by Arabs and Jews, young and old, men and women, in all the cities of Morocco.Footnote 55

In 1951, the same year that the Istiqlal had instigated an anti-Zionist boycott campaign targeting Farid El Atrache and his manager David Salama, a pan-Moroccan urban public quite literally sang in chorus with Elmaghribi and his brand of Moroccanism. He could hardly move in Morocco without drawing attention or being swarmed by fans. The veneration of Elmaghribi by Moroccans even caused some Jews who had left the country to second guess their decision, at least momentarily. “Moroccan Jews arriving in France are speaking about your success with pride and admiration,” Simon informed his brother on 14 August 1951. “I would have paid dearly to find myself in Morocco these days,” he continued, “to be intoxicated by your rise to success; I miss this Morocco.”Footnote 56

In 1952, Elmaghribi started explicitly flying the colors of Moroccan nationalism. Or at least wearing them. “I have ordered from a fine tailor six splendid outfits for the six best performers in Morocco, who will accompany me on my tour,” he wrote to his brother on 22 February 1952. “These wool outfits are in the Moroccan colors: red vests with satin-lined lapels and green pants,” he added with pride. In the midst of composing, recording, performing, and preparing for yet another concert tour in April and May 1952, Elmaghribi had been contacted by the sultan. “These [outfits] were designed,” he noted, “for our presentation to His Majesty the Sultan and then the Glaoui [Thami El Glaoui, the Pasha of Marrakesh], which is going to give me a good helping hand in my climb to success.”Footnote 57 The red-green outfits seem to have done just the trick.

Over the next year, the relationship between Elmaghribi and the sultan––the very symbol of the Moroccan anti-colonial nationalist movement––strengthened considerably. By the end of summer 1952, Elmaghribi had given his first of many private concerts for the royal family. He provided his brother Simon with sumptuous play-by-play. “Last Sunday, Prince Moulay Hassan, son of the Sultan, sent for me and I sang until the break of dawn,” he wrote on 22 August 1952. This was no audition. Crown Prince Hassan was more than familiar with Elmaghribi and his music. “My hits were requested by His Highness himself,” he noted.Footnote 58 After having brought Samy Elmaghribi to his Casablanca villa, the crown prince promised the artist an invitation to the most iconic venue of all.

On 17 November 1952, just before midnight, Elmaghribi took the microphone at Dar al-Makhzen, the royal palace and official residency of the sultan in the capital of Rabat. For the occasion of Throne Day, a holiday initiated by the nationalist precursor to the Istiqlal in 1933, which marked Sultan Mohamed Ben Youssef's ascension to the throne in 1927, the sultan himself had requested the presence of the Jewish artist.Footnote 59 In the early hours of 18 November 1952, Elmaghribi sang two patriotic compositions of his own creation and other songs, “before some 2,000 Muslims and before Moulay el Hassan [sic], who presided over the soirée where the best musical and theatrical troupes of Morocco had passed through.” If his relationship to the monarchy could once be considered private, his association with the royal family was now public. Again he communicated his triumph to his brother in Marseilles. “My success has exceeded the limits of my wildest dreams,” Elmaghribi proclaimed. “The ovation given to me by the public was nothing like the simple applause received by other artists,” he boasted. “Then came the congratulations of all the Muslim personalities, which touched me,” he added.Footnote 60 Elmaghribi's “sensational revolution in Oriental music” was now firmly aligned with the royal family.

A NATIONAL BRAND AND INTERNATIONAL CELEBRITY

In 1952, the same year that Elmaghribi first wore his Moroccan patriotism on stage and began performing his fidelity to the sultan in front of the royal entourage, the artist himself became a national brand. As radio spread across Morocco and as the signals of stations from Radio Tanger International to Radio Maroc strengthened, Elmaghribi became not just ubiquitous but largely inseparable from the era and its airwaves.Footnote 61 To be sure, his live performances on radio and the constant playing of his records on air helped cement his status as the nation's voice during a formative political moment. But that omnipresence also owed to his foray into the world of commercial advertising.

In February 1952, Elmaghribi became an official spokesperson for Coca-Cola in Morocco. His spoken dialogues and musical hooks for the soft drink company were played in heavy rotation on Radio Tanger International over the next several years.Footnote 62 The association was more than just business. As David Stenner has shown, the soft drink company maintained deep connections to the royal palace and the Istiqlal.Footnote 63 During this period, Elmaghribi became the sound of brands like Gillette, Palmolive, Canada Dry, and Shell Oil as well. So too did his family. In one such ad for Angel Chewing Gum, the artist, his wife, and children sang the virtues of the company's many flavors while backed by a small orchestra performing modern Moroccan music. By the end of the year, every Moroccan within earshot of a radio could hear Elmaghribi singing, “How sweet is Angel Chewing Gum” (ma ahla shuwin gum anjil) on Radio Maroc with the near universal resonance of the mid-century radio jingle. With his radio ads, in addition to his concerts and records, Elmaghribi was providing many Moroccans with the soundtrack to their lives in the 1950s. But as with boundaries of genre, physical borders could barely contain the musician or his growing international appeal.

On 24 July 1952, Elmaghribi made his first of many broadcasts for Radio Alger.Footnote 64 The demand for the artist was no longer just a Moroccan one. In fact, although much of the music-related literature on North Africa has tended to adhere to national lines, Elmaghribi's relationship with Algeria and Algerians reminds that musical histories follow transnational flows, even during periods of intense nationalist fervor.Footnote 65 By mid-1952, Algerian fans were clamoring for Elmaghribi, and Algerian musicians had even started performing his repertoire. On 23 June 1952, Simon informed his brother that the Algerian Jewish comic singer Blond Blond had recorded Elmaghribi's “Loucane Elmlayïn” for Radio Paris's Arab broadcast.Footnote 66 “A large number of Arab listeners,” he reported from Marseilles, “were requesting the song daily.Footnote 67

Concurrently, throughout the early 1950s, Elmaghribi's stature as a national figure was bolstered by the electric coverage he received in the Moroccan press. Outlets like Le Petit Marocain, Maroc-Presse, and the bilingual Radio-Maroc magazine covered his radio appearances, provided his recording and travel schedules, reviewed his concerts, and even announced the birth of his triplets. In short, the press captured his nearly every move. This was especially the case for his live performances. “As for the singer himself, he alone is a whole show,” gushed Maroc-Presse in the review of his 26 April 1953 concert in the city of Mazagan. Although especially rich in description, the write-up was on no account atypical. “First there is the composer, the romantic,” the unnamed journalist wrote, “with his Algerian tangos, his flamenco-like paso [dobles], and his Tunisian songs; then, there is the dreamer, with his cheerful choruses, like ‘the Song of the Millions’ [“Loucane Elmlayïn”], which causes the crowd, already warmed up, to explode.” The temperature in the concert hall rose throughout the evening. “It was a lot for an already excited room,” the paper mused. “From the very first notes of his songs, which most already knew,” Maroc-Presse concluded, “Samy Elmaghribi had ‘his’ public.”Footnote 68

For the moment, however, the Moroccan press seemed to tread lightly on at least one facet of Elmaghribi's life: his relationship to the sultan. Nonetheless, the association between the musician and Sultan Mohamed ben Youssef only deepened as the French Residency moved in to immobilize the Moroccan nationalist movement. In May 1953, Elmaghribi traveled from Casablanca to Rabat, to the newly constructed royal palace known as Dar Essalam, where he was once again received by the sultan. This invitation came at a particularly tense time. It was a moment when the Moroccan sovereign was recovering from an injury, and Thami El Glaoui, the Pasha of Marrakesh and French ally, was setting the wheels in motion to dethrone ben Youssef. Given his physical state and the psychological pressure he was facing, the sultan had ordered a temporary halt on visitors to the palace. Elmaghribi proved the exception. Writing to Simon on 20 May 1953, Elmaghribi informed his brother that when accepting the invitation, he had announced to the crown prince that, “I am a slave to His Majesty.”Footnote 69 The following day, El Glaoui, with French support, circulated a petition calling for the sultan's ouster.Footnote 70 On 30 May, the petition, signed by hundreds of Moroccan tribal and religious leaders, was sent to Paris.Footnote 71 Morocco was on the brink of crisis.

Elmaghribi's devotion to the sultan was understood well by the police. That a popular Moroccan musician and the voice of the people had aligned himself with Sultan Mohamed ben Youssef, the most potent political symbol of the nationalist movement, was cause for concern. In April 1953, French police first trailed the musician. Immediately following his 11 April 1953 concert at the Municipal Theater in Mazagan, a confidential intelligence report on “the Tour of the SAMY ELMAGHRIBI troupe,” was stamped by the police commissioner and then rushed to Rabat, where it was delivered to the ministry of interior. But the police officer behind the report was unsure of what to make of the evening. Although the “hall was packed with an audience composed exclusively of Moroccans, Muslims and Jews, who were pleased with the event,” he also “noted the absence that evening of local nationalist elements.”Footnote 72 Looking past the content of Elmaghribi's modern music and, remarkably, past his orchestra's red and green outfits, the officer had mistaken the Istiqlal's particular agenda for Moroccan nationalism itself. Perhaps a superior officer recognized this, for the surveillance of Elmaghribi continued. Sometime later, an anonymously authored handwritten list of Moroccan musical acts was slipped into an expanding police file on “Arab and Jewish theater.” Elmaghribi's name was on it.Footnote 73

The surveillance apparatus that ensnarled Elmaghribi was indicative of the French Residency's growing impatience with Moroccan nationalism and Sultan Mohamed ben Youssef. On 20 August 1953, in a final, dramatic attempt to decapitate the figurehead of the independence movement, the French Residency removed the sultan from the throne. Two days later Elmaghribi wrote cryptically to his brother of his hope for a return to calm.Footnote 74 But with the sultan deposed and exiled to Madagascar, Morocco was far from at ease. Nor would Elmaghribi's life assume the tranquility he sought. Nonetheless, it was at this politically tumultuous time that the musician, already working at a frenetic pace, expanded the bounds of his stardom. For some, this was predictable. “Samy El Maghribi [sic], a brilliant Moroccan star,” a Maroc-Presse journalist wrote on 15 March 1954, “could one day become a star of the entire Arab world.”Footnote 75

In Algeria, Elmaghribi's celebrity soared. What started in April 1954 as a recording session with Radio Alger ended in December of the same year with an acclaimed, multi-city concert tour of the French departments––then in the initial throes of the Algerian Revolution. “I have been very well received there in the Arab artistic milieu,” Elmaghribi wrote to Simon from Algiers on 13 April 1954. He also gave one concert while there that spring, “where I sang the Millions [“Loucane Elmlayïn”] and where I was showered with applause and ululation from an audience that was entirely Muslim.”Footnote 76 Just as he had “his public” in Morocco, he was finding another one in Algeria.

FIGURE 3. Concert poster, Mostaganem, Algeria, June 1955. Elmaghribi was accompanied by Algerian musician Blaoui Houari, an up and coming artist later to become a major star. (Courtesy of Samy Elmaghribi Archive).

During his April 1954 sojourn in Algeria, Elmaghribi added a song to his repertoire that he had not previously performed in Morocco. That abstention, given his public profile and the climate back home, was understandable. While in studio at Radio Alger, he recorded what he referred to in his letters as a taqtouqa djeblia (taqtuqa jabaliyya), a light, popular form from Morocco's northern Rif region. The song in question was “Habibi Diyali” (My Love). Its titular lyric, “Ayli ayli, my love, where is he?” repeated throughout and punctuated by the anguish of the singer who longs for his lost but “not forgotten” love, was suddenly everywhere in late 1953 and through 1954. Elmaghribi was not the only musician to start singing “Habibi Diyali” at the time, despite the fact that the song had long been in circulation. Nor was he even the only Moroccan Jewish artist to record it. In the period immediately after the sultan's exile, “Habibi Diyali” was recorded by an array of Jewish musicians, including the veteran Zohra El Fassia and newcomer Albert Suissa. Others, like Salim Halali, performed it regularly; Halali would later record its best-known version.Footnote 77 The song's popularity, as Elmaghribi surely knew, was largely derived from the refrain, which, in the current context, was understood by audiences as alluding to the missing sultan. That point was certainly clear to El Fassia, who was also close to the sultan. Halali, another frequent guest of the palace, no doubt recognized its potency as well.

Through songs like “Habibi Diyali,” Moroccan Jewish musicians, including Elmaghribi, performed their patriotism outside of the limits of political parties like the Istiqlal. Their sonic contribution to the cause célèbre that was the sultan was understood as nationalist at the time. Already in January 1954, the qaʾid (tribal governor) of Settat informed the civil controller of the region that “Habibi Diyali,” which was played constantly on Radio Maroc, “makes allusion to the exile of the ex-sultan.”Footnote 78 A short while later an unsigned letter from a division within the resident general's office of political affairs stated with alarm that “the record ‘Ayli Ayli, Hbibi dyali’ [sic] has been recorded by three different singers in three different manners.” The note, passed on to the ministry of interior, continued, “that of Albert Suissa (Olympia, 1.005–1.006) contains political allusions.”Footnote 79 Quick action was necessary. The Olympia label, owned by the Moroccan Jewish Azoulay-Elmaleh firm, had just pressed and then received shipment of another 935 copies of the Suissa record containing “political allusions” to the deposed sultan. Indeed, Jewish purveyors of records, alongside musicians, were complicit in facilitating and fomenting Moroccanism.

When Elmaghribi embarked on his first concert tour of Algeria at the end of 1954––with “Habibi Diyali” and other hits in tow––he found a ready Jewish and Muslim audience and a sympathetic press. On 23 December 1954, Alger Republicain featured photos of Samy Elmaghribi posing with Algerian musicians Ahmed Wahby and Mohamed Tahar Fergani as the three met with and performed for the Post, Telegraph, and Telephone (PTT) football club of Algiers.Footnote 80 Five days later, H. Abdel Kader, writing in La Depeche Quotidienne, declared Elmaghribi's 26 December 1954 concert at the Opera of Algiers a triumph. The journalist delighted in the idea that the mostly Muslim audience had also included “many Jews who had come to applaud their idol.” With “Habibi Diyali” and “Loucane Elmlayïn,” Abdel Kader announced that the well-dressed Elmaghribi “has conquered the Algerois public.”Footnote 81 Elmaghribi did the same at the Opera of Oran the following evening. As in Algiers and with a distance from the Residency in Rabat, Elmaghribi had ended his concerts in Oran with “Habibi Diyali,” which the Oran Republicain noted was “very much appreciated by the Oranais public,” who likely also found a nationalist message in it.Footnote 82

In interviews with the press in the midst of his Algerian tour, Elmaghribi basked in his national-turned-international celebrity. “I have never received a welcome like the one I received in Algiers and Oran,” Elmaghribi told Echo Soir journalist El Bouchra. While not making direct reference to “Habibi Diyali,” he revealed that, as much as he delighted in performing in classical Arabic, he was passionate about “composing melodies and words understood by all.” He meant modern Moroccan music. Elmaghribi informed El Bouchra that, “music need not be an abstract language, on the contrary, it should serve as a message of friendship and mutual understanding.” In his interview, Elmaghribi reflected on “Loucane Elmlayïn.” “Some time ago, I wrote a song that I called, ‘Ah, if I had millions.’ It was very well received by the vendors in the markets of Casablanca, who called out to their clients with the chorus.” That adoption and adaptation of a popular song of malleable meaning was once the highlight of his career, he divulged. It had been replaced, he said, by his reception from Algerians, who were now putting “Habibi Diyali” and other songs to their own use.Footnote 83

WALTZING MOROCCO TO INDEPENDENCE

In the fall of 1955, Elmaghribi found himself outside of Morocco during a critical political time. In November 1955, Sultan Mohamed ben Youssef and members of the royal family were removed from exile in Madagascar and installed in Paris. The continued absence of the rightful sultan was no longer politically tenable for the French. Neither was the protectorate. On 6 November 1955, the sultan was reinstated to the throne while in the French capital. Morocco was on the verge of independence. Since July 1955, Elmaghribi had been a temporary resident in Paris as well. There he headlined nightly at Soleil d'Algérie, among the Latin Quarter's many North African cabarets. As the sultan prepared for his return, Elmaghribi was forced to question the expediency of his. For many Moroccan Jews, theirs was the opposite choice: whether to remain in Morocco or start over elsewhere.

Although Elmaghribi's contract at Soleil d'Algérie ran until February 1956, he had always planned to return to Morocco. He was in Paris for work but little more. Over the course of the previous year, he had established Samyphone, one of the first independent record labels in the Maghrib. In addition to serving as a vehicle for his own recordings, Samyphone took the form of a brick and mortar store in Casablanca. In Morocco, he had a career, a national brand, and financial assets to consider. Yet, in Morocco, he would also remain separated from his brother and sister, who had concluded, as had thousands of other Moroccan Jews, that life there was no longer tenable.

In late fall 1955, the bond between the sultan and the Istiqlal had frayed and the beginnings of a power struggle were evident. To Morocco's east, the Algerian Revolution was more than a year in the making, with little sign of letting up. For the father of a growing family, who also happened to be a leading musician, Elmaghribi could have been forgiven for choosing the political stability of a life outside of Morocco.

At that decisive hour, Elmaghribi tied his destiny to that of his country. On 4 November 1955, from his room at the Hotel Derby in Paris, Elmaghribi recorded the first in a series of explicitly nationalist songs released on his own Samyphone label. Among those recordings was “Fi Aid Archek Ya Sultan” (Fi ʿId ʿArshik Ya Sultan; On Your Throne Day, O Sultan), a “Moroccan anthem” (nashid maghribi) of his own composition, which drew on berouali as much as it leaned on waltz.Footnote 84 Elmaghribi's song expressed an unequivocal pride in the sultan, which seemed to mirror that of many Moroccans, whether Muslim or Jewish.Footnote 85 That pride was especially palpable in the chorus.

Like the music of that anthem, Elmaghribi's lyrics were inclusive of the constitutive parts of a broadly conceived Moroccan nation. In the verses that followed, Elmaghribi invoked “the brave of the Rif and Atlas [Mountains],” citizens “from Agadir to Fez,” and those who “come from the cities and the hinterland to delight in your Throne Day.”Footnote 86 Two days after recording “Fi Aid Archek Ya Sultan,” as well as the equally zealous “Alf Heniyeh oua Heniyeh” (Alf Haniya wa Haniya; 1,001 Congratulations), Elmaghribi performed the two nationalist compositions before Sultan Mohamed ben Youssef and Crown Prince Hassan.Footnote 87 If in the past Elmaghribi's devotion to the sultan was performed away from the camera, his fidelity to the royal family––and by extension, to the Moroccan nation––was now captured both on disc and in black and white. On 6 November 1955, an official photo was snapped of Samy Elmaghribi grasping the sultan's hand and bending at the knee. The image, widely circulated, tellingly displayed Samy Elmaghribi's name above that of the sultan.Footnote 88 The former was still the real Moroccan star, and his compatriots were anxiously awaiting his return as well.

Elmaghribi understood that the nationalist songs he had just recorded would make waves in Morocco. Within days of their recording, Radio Maroc had already played them on prime time alongside an interview with the artist. “In spite of all this,” Elmaghribi wrote to Simon on 14 November 1955, “I will think about a return to Morocco only when I will be assured of absolute calm there.” He was concerned, “especially for the safety of my little ones.” But that assurance was rather quick in coming. By 12 December 1955, Elmaghribi had ordered that 1,000 of his nationalist records be pressed for his Samyphone label. “I intend to go to Morocco to sell them myself and on the best terms,” he informed Simon.Footnote 89 For weeks Simon attempted to dissuade his younger brother from returning to Morocco. On 7 January 1956, Simon gave it one last try, but to no avail. Then, for over two weeks, the letters stopped. Elmaghribi had returned to Morocco. It was an interminable silence, given their twice-weekly correspondence and coming as the sultan and the Istiqlal jostled for control of the country.

When Elmaghribi resumed writing to Simon on 23 January 1956, he did so at a moment of exasperation. “Since my arrival in Casa,” Elmaghribi wrote, “my days have been consumed with getting the [Samyphone] records out of customs, frequent trips to the palace in Rabat, and sales at the store.”Footnote 90 His initial return to Morocco had been busy. Among other activities, he headlined the inaugural gala of El Wifaq (al-Wifaq, the Entente), a Jewish-Muslim nationalist association presided over by Crown Prince Hassan, performed alongside Algerian Jewish star Salim Halali in support of the Jewish Anti-Tubercular Society, and met frequently with the sultan and crown prince, who “promised me I had a future here in Morocco.”Footnote 91 His return was heralded in the press. He had been out of the country for less than six months but there was concern that the Moroccan national figure was contemplating exile. “Is your return to Morocco permanent?” one journalist asked desperately. Elmaghribi responded positively. “I have returned to my country to see His Majesty again,” Elmaghribi said, “and after a few days here, I need to go back to the French capital, pick up my family, and then return to Morocco for good.”Footnote 92

On 22 March 1956, Morocco gained formal independence from France. That same day, Elmaghribi wrote to Simon from Paris. The tickets were booked. He had decided to return to “his public” on the very day that Moroccans had regained their sovereignty. It was the ultimate performance of patriotism. For that act, both the palace and the public would reward him. Within days of his arrival, Elmaghribi was called upon to perform for the crown prince. In April 1956, during the first two nights of Ramadan, the Jewish artist gave a private concert for the sultan.Footnote 93 “The situation here is not as alarming as you think,” Elmaghribi wrote his brother on 11 May 1956.Footnote 94

Two months after the Moroccan kingdom had gained independence from France, Elmaghribi was doing better than he could have imagined. He had moved his Samyphone store to a tony location on Boulevard de Bordeaux in Casablanca. In the meantime, his nationalist music had become more express and that much more in demand by the palace, the Moroccan public, and the newly constituted Moroccan Royal Armed Forces. On 15 May 1956, he wrote to Simon.

Saturday, I recorded verses in classical Arabic (written and composed by me) for Radio Maroc, a military song extolling the glory of His Majesty, His Imperial Highness, Moroccan freedom, and the Royal Armed Forces, whose parade took place yesterday … this was the only Moroccan song presented to radio listeners on the occasion of the first parade of the Moroccan army.Footnote 95

Elmaghribi added that he had been flooded by both compliments and record orders since the broadcast of the song. On 25 May 1956, he entered a Casablanca studio to cut a record of the song that was already causing a frenzy among Moroccans: “Allah, Ouatani oua-Soultani.”Footnote 96 In this post-independence patriotic effort, he was joined by other Jewish artists, who also recorded their support for the sultan and the Moroccan nation on disc.Footnote 97 But few were as expressly militaristic as Elmaghribi. By contrast, “Allah, Ouatani oua-Soultani” was practically a military march, which provided booming endorsement of the sultan, the cause of independence, and Moroccans, whom he now referred to as “soldiers” in both chorus and verse.

FIGURE 4. Elmaghribi's hit nationalist anthem, “Allah, Ouatani oua-Soultani,” released on his own Samyphone label in 1956. (Drawn from author's personal collection).

And after “Allah, Ouatani oua Soultani” was performed during Morocco's first military parade, Elmaghribi informed his brother that the Moroccan Royal Armed Forces band was now in the process of learning the song as well.Footnote 99

CONCLUSION

In independent Morocco and with the militaristic “Allah, Ouatani oua Soultani,” Samy Elmaghribi had reached the zenith of his fame. The Jewish artist arrived at that moment by doing no less than pioneering modern Moroccan music and espousing Moroccanism, an inclusive variant of nationalism that placed Sultan Mohamed ben Youssef and the Moroccan people––Muslims and Jews––at its core. This article has argued that a focus on music allows for a rereading of the mid-century nationalist moment in Morocco, during which multiple approaches to national belonging existed, flourished, and could be heard. As the case of Elmaghribi makes clear, Moroccanism was widely popular among urban Moroccans despite having received little attention to date in a nationalist historiography that has favored a near-exclusive focus on the Istiqlal.

FIGURE 5. Elmaghribi signs autographs (including on his own LPs) for fans in Casablanca, c. 1956. (Courtesy of Samy Elmaghribi Archive).

This article has also underlined the point that neither Israel's establishment in 1948 nor Moroccan independence in 1956 were an end for the Jewish musician, who not only remained in Morocco during that period but whose astonishing climb to national and transnational fame in the Maghrib was measured by those very years. Indeed, treatment of leading Moroccan Jewish cultural figures like Elmaghribi provides for a reassessment of the lives of those Jews who remained in Morocco. It establishes that a number of prominent Moroccan Jews were nationalists of a certain type who carved out a space for themselves beyond the bounds of political party and across borders. Finally, Elmaghribi's career, launched at the end of the colonial period and continuing to flourish in the years of independent Morocco, reminds the historian that decolonization in the Maghrib should be studied as a process, not as rupture. In this way, the study of both Jews and music allows for a better understanding of MENA societies in general, especially during the years of transition in the middle of the 20th century, which remain shrouded in silence.

When Elmaghribi did leave Morocco three years after independence, he did so for a set of complicated reasons born of gossip. On 1 March 1959, he wrote to his brother of pernicious “rumors that some jealous and envious people are spreading, even going as far as to speak of my final departure [from Morocco] following an expulsion order.”Footnote 100 In the same breath, Elmaghribi announced that he intended to repaint and redecorate his apartment and then hold a press conference there in order to dispel the false charge. The next day, he wrote again to Simon. “It has become clear that the noise bubbling up around me,” he explained, “was due to an erroneous interpretation of the truth: my name was simply confused with that of Salim Halali.” According to Elmaghribi, Halali had been forced out of Morocco two days earlier after a police raid on his cabaret.Footnote 101

That a palace favorite could be summarily expelled in the independence era understandably unnerved the Jewish musician. The negative attention did as well, even if misplaced. Elmaghribi, of course, was more than just an artist. He was also a father of six. The rumor, which set him on edge, surfaced in the midst of a serious economic crisis. Meanwhile, a new customs regime was making the transnational affairs of Samyphone ever more difficult to operate. He made a decision with his family in mind. He left. Other cultural figures would too. Months after his departure, word reached him that the Muslim recording artist Ahmed Jabrane had been jailed by the regime.Footnote 102 Soon thereafter, Jabrane found himself in exile in Washington, DC. Elmaghribi's concern for his well-being and that of his family appeared to have been well founded.

When he returned to Morocco in May 1967 to give a series of concerts, reporters met the national icon on the airport tarmac in Casablanca. “Who are you Samy Elmaghribi?” a certain M. P. from Le Petit Marocain asked provocatively of the artist. Without missing a beat, he responded: “First of all, a Moroccan.”Footnote 103

Acknowledgments

I owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to Sarah Abrevaya Stein, Jonathan Glasser, and David Stenner for their invaluable comments on earlier drafts of this article. I would also like to extend my sincerest of thanks to the IJMES anonymous peer reviewers and Joel Gordon for being such close and perceptive readers. Finally, I am forever appreciative of Yolande Amzallag, without whom none of this work would have been possible.