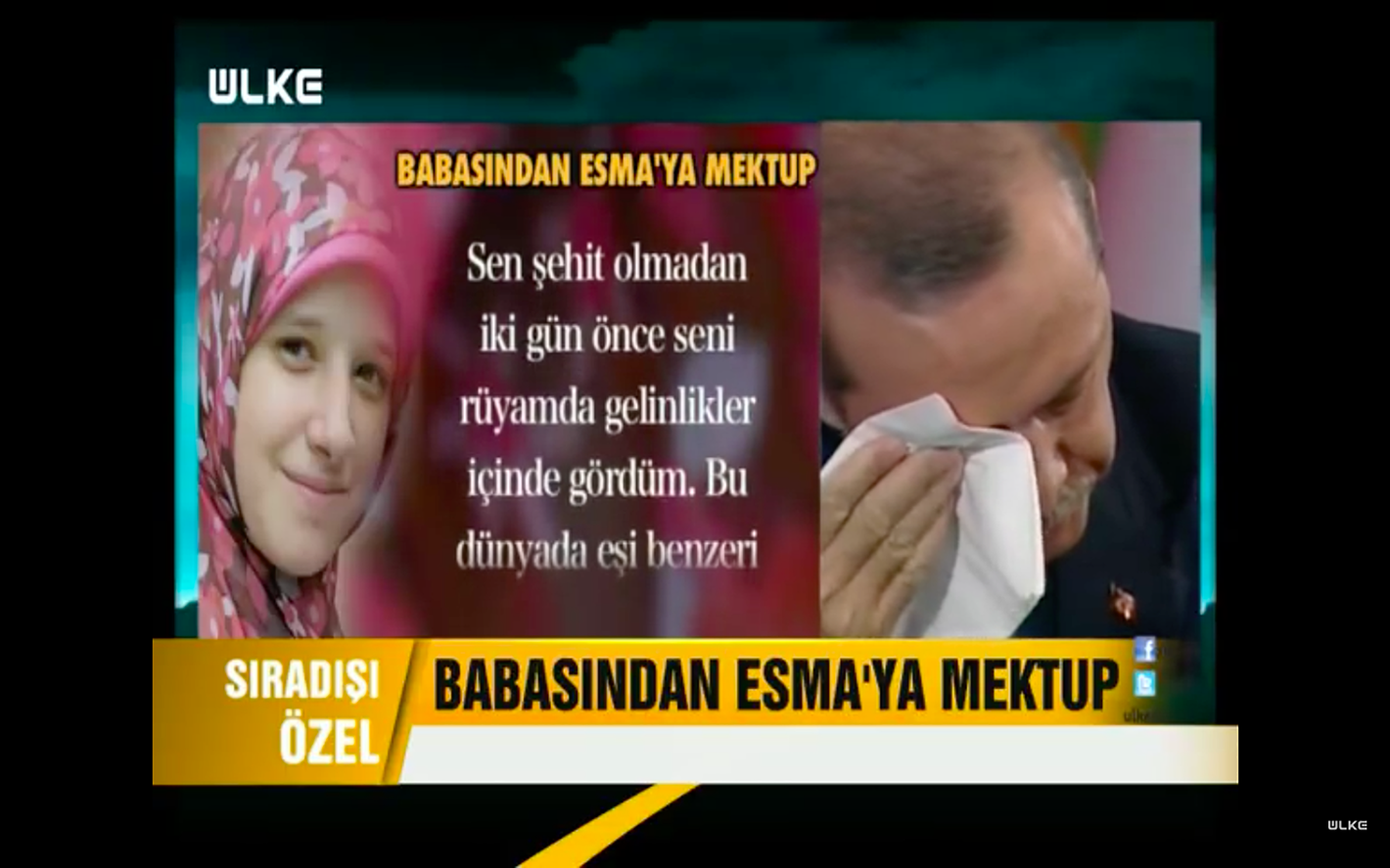

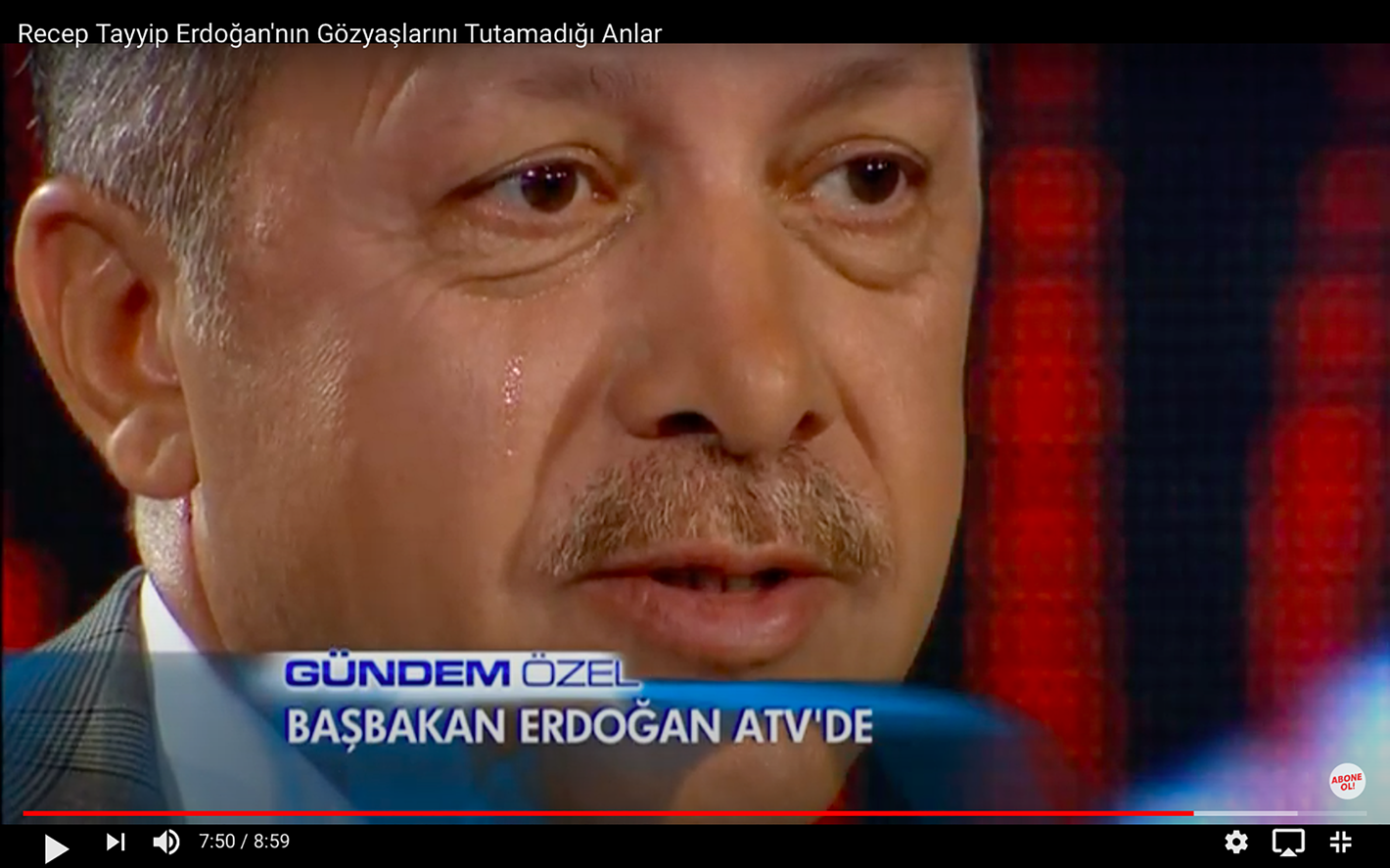

In August 2013, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the then-prime minister of Turkey and the president since 2014, began to cry in a live broadcast on TV while a letter written by the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood politician Muhammad al-Baltagi was being read. The dramatic letter was addressed to al-Baltagi's deceased daughter who was killed by the Egyptian security forces during the violent protests against the military coup that ousted the Muslim Brotherhood from power that summer. The cameras zoomed in on Erdoğan for several minutes as he cried. When the moderator asked what made him so emotional, Erdoğan stated that the letter made him think about his own children who could not see their father enough while growing up because he was working so hard for his political cause. He added that he was moved by al-Baltagi's maturity in approaching life after death and his daughter's martyrdom.Footnote 1 This was not the first or the last time that Erdoğan appeared emotional on TV. Contradicting the image of a tough and authoritarian strongman, Erdoğan has been seen weeping many times in public. By my records, between 2007 and 2020 Erdoğan has become teary-eyed in public at least thirty times. The variation in Erdoğan's public emotionality over time also is dramatic. Of these thirty times he wept or showed teary eyes in public, twenty-five occurred after the Gezi protests in 2013 and eighteen after the failed coup attempt in July 2016.Footnote 2 Other prominent members of the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) also have cried in public several times. In 2012, the then–minister of foreign affairs Ahmet Davutoğlu was photographed crying while hugging a Palestinian man in Gaza. At an inauguration ceremony, Bülent Arınç, the then–deputy prime minister, could not keep his tears back while giving a speech that also made Davutoğlu cry. Binali Yıldırım, Melih Gökçek, Abdullah Gül, and Süleyman Soylu are among other AKP politicians who have cried at different public occasions (Figs. 1–2).Footnote 3

Figure 1. Erdoğan crying over al-Baltagi's letter (“Recep Tayyip Erdoğan'ın Esma'ya Yazılan Mektuba Ağladığı Anlar,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GIq4dadI8WE; accessed 12 July 2020).

Figure 2. Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım during a press conference after the 2016 coup attempt “Başbakan Binali Yıldırım Gözyaşlarını Tutamadı,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P8EI6psNCaM; accessed 15 September 2020).

There are reasons why the weeping in public of Erdoğan and other AKP members is peculiar. First, Erdoğan's propensity to tears in public does not easily conform to his tough posturing. Public weeping can be risky for politicians as it can be taken as a sign of vulnerability, weakness, loss of self-control, or opportunism. In 1972, when the American senator and Democratic presidential candidate Edmund Muskie got emotional at a press conference, he was accused of being unmanly and emotionally unstable. Muskie's competence for office was questioned, particularly given the context of the Cold War, a time when presidents needed to project an image of masculinity and strength vis-à-vis the Soviet adversary.Footnote 4 In 1985, when the British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher shed tears during a TV interview, speaking about her father, the press mocked her severely, interpreting her public display of emotions as calculated and fake.Footnote 5 Erdoğan and other AKP leaders also have been criticized and mocked by the opposition for shedding “crocodile tears” in public.Footnote 6

Second, historically, prior to the AKP period, for a Turkish politician to cry in public was exceptional. In the 1990s the prime minister Tansu Çiller occasionally became emotional and teary-eyed in public.Footnote 7 Turgut Özal, when he was president, was teary-eyed during a TV interview after a surgical operation in 1992.Footnote 8 Nevertheless, these examples were extraordinary. Erdoğan and other AKP members cry frequently enough that it has become almost mundane. Weeping in the public political arena is a phenomenon of the AKP's Turkey.

Despite the increased likelihood of the emotionality of politicians being captured and broadcast due to the growth of new media technologies, the frequency of Erdoğan's tearfulness in public begs an explanation. In today's world of “communicative abundance,” the line between the public and private spheres of politicians has blurred.Footnote 9 Digital media, social networking, and mobile technologies allow information to flow quickly and widely. The change in media technologies is one reason there is less of a taboo about politicians crying in public than a few decades ago. Many politicians and public figures have been caught off guard crying by the media.Footnote 10

It is, however, difficult to explain Erdoğan's public tears by the growth of new media. The repeated nature of these instances of tearing and weeping and the way these images are promoted by the pro-AKP media suggest that there is an element of intentionality in the construction of Erdoğan's emotional image. Erdoğan's tearful appearances are frequently incorporated into propaganda videos made by the AKP and his fans.Footnote 11 The official documentary on the 15 July 2016 coup attempt posted on the presidency's website shows Erdoğan sobbing at the funeral of Erol Olçok, his former campaign manager, killed during the attempt.Footnote 12 Another documentary produced by pro-AKP media uses the image of Erdoğan's tearful eyes a few times while recounting the process that led to his imprisonment in 1998.Footnote 13 It is not possible for social scientists to assess how sincere his tears are or whether they come involuntarily. Nevertheless, it is possible to assess how this image of emotionality is created and used by the media. Given Erdoğan's power to control and censor the media we can assume that he does not mind the publicity of these emotional images. The production and distribution of the images are intentional, seeking to project a particular appearance.

So how can we make sense of these public displays of emotionality by Erdoğan and other leaders of the AKP? What explains the variation in these emotional displays over time?

Building on the literature that conceptualizes populism as a particular political style, I argue that crying in public can be understood as a populist performative act of legitimation and mobilization.Footnote 14 Public tears serve to dramatize the basic components of the populist discourse: the antagonistic divide between the people and the elite, the claim to represent the people who are victimized and suffering, and the evocation of crisis and threat. I also contend that the increased visibility and frequency of public weeping by Erdoğan relate to two major dilemmas that populists in power encounter. Both dilemmas stem from a growing discrepancy between populist rhetoric and practice, diminishing the credibility of the populist leader and putting constituent support at risk. By signaling emotional authenticity, Erdoğan's tearfulness can be seen as an attempt to boost his persuasiveness at a time when his growing wealth and political power are increasingly at odds with his populist rhetoric. Using emotional appeals, Erdoğan also seeks to consolidate the identity and solidarity of his constituents and mobilize them against the opposition.

Research has identified the strong tie between emotions and populism, but this relationship is understudied. Scholars have sought to understand which emotions are associated with the support for populism. They have tried to assess the relative weight of negative emotions, such as anger, resentment, and fear, in the formation of populist attitudes.Footnote 15 Another group of scholars has analyzed the emotional rhetoric used by populists to elicit support.Footnote 16 In this article I call attention to a different kind of populist appeal and underline the importance of studying emotional performances to understand how populism works. How populists deliver their message can be as important as the content of their rhetoric. Populism is as much about how politicians talk, behave, and act as what they say. Focusing on an unconventional emotional style, this study also shows the modular character of populism and the expandable nature of its performative repertoire, which draws from and conforms to different cultural and ideological contexts.

Populism

Populism has been a contentious and nebulous concept. Scholars working on different regions have defined populism in different ways. Whereas Europeanists associate it with right-wing politics characterized by anti-immigrant and xenophobic positions, those working on Latin America associate it with clientelism, statism, and welfare policies. One of the main criticisms of the conceptualization of populism has been that it can not be considered a separate ideology because it lacks thickness, unlike fascism, socialism, and liberalism.Footnote 17 Populists can represent various political programs from the far left to the far right. As Bart Bonikowski explains, “unlike most political ideologies, populism is based on a rudimentary moral logic that has few direct policy implications and does not provide a general understanding of society or politics. In other words, populism does not offer a worldview; at best, it offers a simplistic critique of existing configurations of power.”Footnote 18

More recently, scholars have begun to sharpen the concept to make it analytically more useful. A group of scholars emphasizes the stylistic elements that are unique to populism. For example, Rogers Brubaker treats populism as a discursive and stylistic repertoire. Accordingly, “elements of the repertoire, taken individually, are not uniquely populist, but may belong to other political repertoires as well, and . . . it is the combination of elements—rather than the use of individual of elements from the repertoire—that is characteristic of populism.”Footnote 19 He identifies the core element of populism as the claim to speak and act in the name of “the people,” defined in opposition to economic, cultural, and political elites. Populists portray the people as morally decent, economically struggling, and endowed with common sense. Elites, on the other hand, are portrayed as rich, powerful, and educated but also as selfish, corrupt, and possessive of a condescending attitude toward and out of touch with the problems of ordinary people. Brubaker identifies five additional elements of the populist repertoire. First, populists claim to reassert democratic political control over issues that they claim have been depoliticized. Second, populists emphasize majoritarianism. Third, they distrust mediating institutions like political parties, media, and the courts. They seek to assert control over the media or to communicate directly with the people through social media. Fourth, they claim to protect the people against internal and external threats. Finally, they endorse a crude, unrestrained, “bad boy” demeanor.Footnote 20 This is what Pierre Ostiguy calls “flaunting of the ‘low.’” For Ostiguy, populists display more raw and culturally popular tastes, are more demonstrative in their bodily or facial expressions, and behave in more uninhibited, hot-tempered ways in public to show that they come from the people. This contrasts with the “high” style, in which public self-presentation is well mannered, proper, and composed.Footnote 21

Similarly, Benjamin Moffitt identifies populism through its performative aspects, which are used by a wide range of politicians across the world. Populists can be distinguished by how they look, talk, and present themselves in public space. As a way to connect themselves with the people and show that they come from the people, they tend to disregard the “appropriate” and usual ways of conduct in the political realm. For example, they use slang, disregard political etiquette, resort to coarse and culturally vulgar appeals, make offensive remarks about their opponents, and present themselves in more colorful and demonstrative ways. They construct a narrative of crisis and threat through dramatization.Footnote 22 The conceptualization of populism as a distinct political style is useful not only because it identifies populism across a range of ideological and cultural contexts but also because it takes seriously the more bizarre, performative, and emotional aspects of politics, such as public crying, that are often not analyzed.

Like other leaders of political movements, populists appeal to people's emotions to mobilize support. People make political decisions through a mix of cognition and emotion, or what James Jasper calls “feeling-thinking processes.”Footnote 23 Emotions have a significant impact on how people define their interests, derive meaning from political events, and construct their identities. As Jonathan Mercer states, emotions and identity depend on each other: “Identification without emotion inspires no action for one does not care. Whereas indifference makes identities meaningless (and powerless), emotion makes them important. . . . Emotion makes identity consequential, and identity makes group-level emotion possible.”Footnote 24 Collective action requires emotional triggers. Emotions like anger, joy, and pride motivate people to take action and politically mobilize because they “promote optimistic assessments, a sense of personal efficacy, and risk acceptance.” Other emotions, like fear, shame, and sadness, discourage people from taking political action because they “increase individuals’ tendencies to make pessimistic assessments, discount prospects of change, privilege information about danger, have a low sense of control, and avert risk.”Footnote 25

The use of an affectual narrative and manner as opposed to a rationalist discourse and composed demeanor is a key marker of populist style.Footnote 26 Different reasons may account for this distinctive relationship between emotions and populism. The global spread of populism is partly related to the commercialization of media and development of new communications technologies that prioritize simplification, dramatization, emotionality, and visualization. Mediatization of politics fosters a populist style of political communication.Footnote 27 Doing politics has become more performative and theatrical with the growth of visual and social media, providing more opportunities for politicians to appeal to mass constituencies directly and pushing them to endorse more attention-grabbing and emotional political styles.Footnote 28 Furthermore, the thin ideology of populism makes persuasion through emotional appeals more necessary. Finally, populism encourages permanent mobilization of its constituency because it relies on the claim of direct representation of the majority at the expense of intermediary institutions. As Nadia Urbinati underlines, populism rests on the claim that the political opposition is morally illegitimate because it does not represent the right people. Populists “try to remain in a permanent electoral campaign in order to reaffirm their identification with the people and assure the audience they are waging a titanic battle against the entrenched establishment in order to preserve their purity.”Footnote 29 This need for constant political mobilization demands heavy reliance on emotional and symbolic appeals. Populist performative style is about evoking emotions: love and compassion for the populist leader and anger and contempt for the opposition.

Performing Populism Through Tears

Since its foundation in 2001, the AKP has endorsed a strong anti-elitist discourse, emphasizing the victimhood of the majority at the hands of a repressive, secular, and Western-oriented minority. Like populists across the globe, the party presents itself as the representative of the real “national will,” the “silent majority,” and the people on the street, pitted against the elite.Footnote 30 “The people” defined by the party are faithful Muslims. “The elite” includes the Kemalist political establishment, comprising the Republican People's Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, CHP) and the secularist military, bureaucracy, and judiciary. In his speeches Erdoğan frequently brings up the discrimination and humiliation that people from lower-income, conservative groups and rural backgrounds have encountered. “In this country there are White Turks as well as Black Turks. Your brother Tayyip belongs to the Black Turks,” he has stated.Footnote 31 He boasts of being a “man of the people,” having worked hard, selling lemonade on the street, coming from a pious and modest family, and attending a religious school.Footnote 32 In his party's propaganda material he is presented as “one of us” (bizden biri), “the lad of the neighborhood” (mahalle delikanlısı), or a leader who can be called by his first name, Tayyip.Footnote 33 In another speech he says, “We know very well what exclusion means due to someone's belief, exercise of religion, or scarf on her head. We know what poverty is. . . . We are the children of this land.”Footnote 34 Documentaries on Erdoğan made by the pro-AKP media portray him as an authentic, pious, and hardworking leader whose support comes from “those who were looked down on” (hor görülenler), “those whose sense of the divine was ridiculed” (kutsallarıyla alay edilenler), “those who were otherized” (ötekileştirilenler), and “the oppressed” (mazlumlar).Footnote 35

I contend that crying in public should be seen as a populist act as it serves to dramatize the basic discursive elements of populism. One element that Erdoğan's crying alludes to is the moral divide between the people and the elite. Several instances of his public tearfulness have been triggered by representations of “old Turkey” juxtaposed with the “new Turkey.” The AKP and Erdoğan invoke the rhetoric of old vs. new Turkey to emphasize the Manichean view of Turkish political history. In this depiction, old Turkey represents the period when the Kemalist elite dominated the state apparatus and ruled the country through top-down, unjust policies, oppressing the majority. The “new Turkey” refers to the AKP era, when real popular rule was established. Erdoğan has cried publicly in reaction to portrayals of injustice and suffering at the hands of the secular, Kemalist elite in the old Turkey. As such, his tears work to accentuate the Manichean discourse of populism. For instance, in 2010 Erdoğan became teary-eyed while speaking at the AKP's parliamentary group meeting. His speech was about the repressiveness of the military regime after the 1980 coup and the arbitrary execution of two political prisoners. While quoting a letter written by a right-wing prisoner before he was executed, it appeared that Erdoğan could not hold his tears back.Footnote 36 This emotional speech was strategic. It happened two months before the 2010 referendum that put a number of constitutional amendments to a vote with the aim of weakening the power of the military and the judiciary. Employing emotion, Erdoğan sought to mobilize the voters in favor of the amendments by reminding them of the military's repression. Similarly, in April 2017, only a few days before the referendum that ratified the move toward a presidential system, Erdoğan became emotional on live TV while watching scenes from the “old Turkey.” The video, an excerpt from a 1990s TV show, contained interviews with enraged patients complaining about the inefficiencies and neglect they encountered in hospitals. Broadcast with the chyron “Do not forget” (Unutma), the split screen showed Erdoğan's growing agitation and tearfulness next to the scenes of patients who blamed the corrupt state elites for their suffering.Footnote 37 Erdoğan's display of emotions highlighted the moralistic division between the people and the elite as he signaled his compassion for the former and indignation at the latter (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Erdoğan crying on TV days before the 2010 constitutional referendum about the political repression of the Kemalist elite (“Recep Tayyip Erdoğan'ın Gözyaşlarını Tutamadığı Anlar,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TmXiKrxj4yE; accessed 15 September 2020).

Erdoğan and his party construe the people as devout Sunni Muslims, labeling groups that reject this identity, such as non-religious Kurds, Alevis, liberals, leftists, and secularists, as enemies of the nation and the people.Footnote 38 The AKP government stands out in Turkish political history for its heavy use of Islamist symbolism, initiating significant changes in the official symbolic repertoire. It has moved away from expressions of staunch secularism, incorporating Ottoman and Islamic imagery more visibly in public space. Official ceremonies began to include prayers led by the head of the Religious Affairs Directorate (Diyanet) and Qur'an recitations. In some venues it is Erdoğan himself who recites verses from the Qur'an.Footnote 39 AKP's shift toward a more Islamic character has included some real policy changes leading to the expansion of religious schools, an increase in Islamic education in school curricula, legal regulations to restrict alcohol consumption, and more mosque construction.

Political Islam's symbolic and rhetorical universe provides the AKP rich material to draw from in its populist appeal to the Muslim majority. As a sign of devotion to God and innocence, crying is part of the cultural repertoire of many religions, including Islam. The Qur'an mentions it in a positive light, and its recitations can be accompanied by collective weeping.Footnote 40 The hadiths speak about the Prophet Muhammad and the first caliph Abu Bakr weeping.Footnote 41 Crying has a special place in Shi'ite religious ritual. The festival of Muharram, commemorating the killing of Husayn and his family, involves collective ritual crying.Footnote 42 Thomas Hegghammer writes that weeping is socially appreciated among the jihadis and that communal weeping is an integral part of the jihadi culture, like poetry, music, and dream interpretation. Jihadists cry during Qur'an recitations and prayers, after being denied martyrdom or an opportunity to fight, and when they see images or information about Muslim suffering.Footnote 43

In Turkey, too, the image of crying has been common in Islamist visual imagery. It communicates the message of Muslim victimhood, unfair suffering, and struggle, which have been integral to Islamist political discourse. “Various photographs, illustrations, and drawings of pain and tears, mostly of children, circulate through a wide range of Islamic media, from television to print media to the Internet,” writes Özlem Savaş, stating that this “aestheticization of suffering” is central to the political Islamic imagination in Turkey.Footnote 44 Fethullah Gülen, Erdoğan's most prominent Islamist opponent, is well known for crying while delivering his sermons, inducing mass weeping in the audience.Footnote 45 The image of crying has cultural resonance for Erdoğan's Muslim voters.Footnote 46

Several instances of public weeping by Erdoğan and other members of the AKP were triggered by references to Muslim victimhood and suffering due to injustices at the hands of their enemies. Emine Erdoğan, the AKP leader's wife, burst into tears in Myanmar when she met members of the Muslim minority who were subject to repression by state security forces.Footnote 47 Yalçın Topçu, then minister of culture and tourism, became emotional during a speech about İskipli Atıf Hoca, an Islamist who opposed the secular character of the Turkish Republic. Topçu could not hold his tears back when talking about how the Independence Tribunal sentenced İskipli Atıf Hoca to death in 1926.Footnote 48 Often Erdoğan and other members of the AKP have teared up in reaction to religious nationalist poems written by such poets as Mehmet Akif Ersoy, Arif Nihat Asya, Erdem Beyazıt, and Necip Fazıl Kısakürek. In 2016, the cameras zoomed in on Erdoğan's teary eyes when Sezai Karakoç's poem “Oh, Beloved” (Ey Sevgili) was recited by a little girl during the opening ceremony of the Diyanet Center of America in Maryland.Footnote 49 Erdoğan is famous for incorporating poems rich with Islamic content into his emotional oratory. In 1998, he was convicted to ten months in prison for inciting religious hatred after reading a poem at a political rally. Cihan Tuğal writes that many AKP activists told him that the recitation of this poem by Erdoğan made them cry, and they joined the party after his imprisonment because they could not bear the injustice.Footnote 50 The pro-AKP media frequently uses his recitations to elicit emotional effect.Footnote 51 Shedding tears for Muslims, Erdoğan and other members of the AKP signal that they feel the pain of Muslim suffering and can speak on their behalf.

Crying also dramatizes the threat and crisis rhetoric that is central to populist discourse. It highlights the idea that the people, the Muslim majority, are under constant threat of victimization by outside groups or elites. For example, in 2015 Erdoğan cried with his wife in Albania during a mosque's inauguration ceremony while a student was reciting a poem. Titled “Prayer” (Dua), the poem read like a prayer, begging God not to allow the country to be taken over by non-Muslims.Footnote 52 As the next section explores, it was not a coincidence that a large part of Erdoğan's public emotionality was on display after the 2013 Gezi protests and the 2016 coup attempt. Both challenges to the AKP government gave Erdoğan the opportunity to construct a sense of crisis and emergency and highlight the continuing threat that Muslims face, reminding his constituents that the AKP government protects the Muslim majority's well-being and security.

Dilemmas of Populists in Power

There is significant variation in Erdoğan's public emotionality over time; much of the public crying of Erdoğan and other AKP leaders occurred after the Gezi protests. What explains this increased frequency of crying in public? My contention is that it relates to two major dilemmas encountered by populists in power, pushing them to appeal to their constituents through more performative emotional means. These dilemmas stem from a growing discrepancy between populist rhetoric and practice that begins to hurt the persuasiveness of the leader's claims. Crying not only dramatizes the basic components of populist discourse, but it does so in a manner that signals authenticity. Because it is seen as involuntary, crying has been associated with sincerity. Like blushing, tears are harder to fake than other emotional signals. Therefore they are taken as a sign of honesty and reliability.Footnote 53 For instance, in many religious devotional contexts crying conveys the depth and authenticity of one's religious feelings.Footnote 54 Male crying is particularly associated with genuine feeling because it is more exceptional.Footnote 55 According to Maurizia Boscagli, public display of masculine feelings through weeping signals emotional authenticity because it violates two taboos: privacy and established gender boundaries.Footnote 56 It is easy to be a populist rhetorically. Populists need more than their rhetoric to convey credibility, especially when they are in power. Because it is difficult to fake, crying can function as a perceivable indicator of authenticity that makes the populist discourse more believable.Footnote 57

The first dilemma relates to the anti-elite rhetoric of populists. Populists claim that they are the only real representatives of the people, criticizing elites as out of touch with and indifferent to the realities of the ordinary people. While in power, however, populists become members of the political and most likely economic elite. Therefore, the longer they rule the more they feel pressure to show that they have not become too distant from the people and that they still are outsiders to the political establishment. Analyzing presidential campaign discourse in the United States from 1952 to 1996, Bonikowski and Gidron find that the longer an incumbent stays in power the less likely he is to resort to populist rhetoric, because his antiestablishment claims lose credibility among the electorate.Footnote 58 As Jan-Werner Müller describes, however, populists in power can perpetuate anti-elitism by aesthetically performing proximity to the people.Footnote 59 One way of portraying an image of ordinariness is through emotional expressions, such as crying.

Public crying signals proximity to people when it becomes difficult to sustain the credibility of anti-elitist and antiestablishment discourse. By its third term the AKP government had already dismantled Turkey's old establishment, eroding the veto power of the military and the judiciary in politics and weakening the secularists’ grip on the ranks of the bureaucracy.Footnote 60 It concentrated economic power and created its own business elite through capital transfers and distribution of state resources to loyal businesses. The elaborate clientelist relationships enriched several AKP politicians’ families, including Erdoğan's, as the 2013 corruption investigations and leaked tape recordings revealed.Footnote 61 Erdoğan's gigantic presidential palace opened in 2014 in Ankara, with its lavishly decorated and colossal interior, and brought into sharp relief the discrepancy between Erdoğan's lifestyle and that of the people he claimed to represent.

As Moffitt underlines, populist leaders need to strike a balance between appearing both ordinary and extraordinary to appeal to people. On the one hand, they claim to possess outstanding leadership qualities and project themselves as extraordinary representatives of the people.Footnote 62 This emphasis on Erdoğan's extraordinariness can be seen in the pompous state ceremonies and massive rallies that he attends, his gigantic Presidential palace, and the cult of personality constructed around him. His supporters refer to him as “the chief” (reis), “a leader who gathers all of Allah's qualities in himself” (Allah-ü Teala'nın bütün vasıflarını üzerinde toplamış), and “the shadow of Allah on earth” (Allah’ın yeryüzündeki gölgesi).Footnote 63 On the other hand, populist leaders also need to present themselves as being of the people and ordinary. They do this by disregarding political correctness and appropriate forms of conduct, making attention-grabbing remarks, and emotional appeals. They perform ordinariness through “bad manners.” They use slang and coarse and vulgar language, make offensive remarks, and disregard the usual practices of politics. Erdoğan has been famous for his bad manners, increasing in intensity as he has concentrated more power. With an aggressive and confrontational style, he called the Gezi protesters “marauders” who “drink until they puke” and has referred to academics, students, and journalists who criticize his government's policies as terrorists and traitors.Footnote 64 He has disregarded diplomatic rules of conduct, threatening the US with an “Ottoman slap” and accusing German and Dutch politicians of “Nazi practices.”Footnote 65 These distinctive ways of acting, speaking, and looking, including his defiant and offensive remarks about his opponents, impulsiveness, unusual claims such as “Muslims discovered the Americas before Columbus,” conspiratorial statements, and public crying belong to the populist tool kit for signaling ordinariness.Footnote 66

Crying in public signals Erdoğan's ordinariness at a time when his growing political power and economic wealth increasingly set him apart from the politically and economically marginalized. Similar to increased emphasis on Islam and piety and bad manners, it serves to connect the ruler and the ruled by communicating intimacy and approachability, reinforcing the image of the leader as being of the people. In one instance, Erdoğan's crying was triggered by a sentimental poem titled “Farewell Mother” (Hoşçakal Anne), recited on stage by İbrahim Sadri, a poet and artist popular particularly among Turkey's conservatives.Footnote 67 After finishing the poem, Sadri gave a short speech emphasizing Erdoğan's loyalty to his friends, saying that Erdoğan did not leave him alone when he lost his mother, came to the funeral, and carried the casket with him. Erdoğan's emotionality conveyed the image of an approachable, empathetic, and compassionate leader. His tender feeling for mothers also conformed with his rhetoric of masculinity, which exalts women primarily as mothers. Erdoğan calls childless women deficient and incomplete, associating women's worth with the ability to reproduce and raise the next generation of pious Muslims.Footnote 68 In his speech, Erdoğan described the suffering of mothers and the sacrifices they make for their children, including his own mother and daughters. In another instance, the cameras showed Erdoğan wiping his eyes with a handkerchief while he was watching a short documentary during a meeting with the Roma community in 2018. The documentary covered the discrimination that the Roma community in Turkey faced before the AKP came to power. It also included interviews with Erdoğan's childhood Roma friends from Istanbul's Kasımpaşa district, where he grew up. The interviewed people emphasized their Muslim identity and recalled Erdoğan's humility and kindness toward them as a friend.Footnote 69 Erdoğan's tearful reaction conveyed his ordinary roots, his familiarity with people's suffering, and his continuing loyalty to them. In 2018, he became teary-eyed for a second time watching a video that showed patients suffering in the old Turkey's hospitals. Suggesting that he came from the people, he said that he also was a patient in these hospitals, which were run by the Social Security organization in the 1990s, experiencing the same distress.Footnote 70 The image of crying has been used to indicate the ordinariness of other AKP leaders as well. In an AKP video titled, “We Loved You So Much,” made in honor of Binali Yıldırım, then speaker of the parliament, a series of photographs showed him hugging children, petting lambs, interacting with ordinary citizens, tending a sick man, and crying.Footnote 71 The increased frequency of public weeping by Erdoğan can be attributed to his growing need to signal proximity to people as he has become more firmly entrenched in the ruling elite.

The second dilemma of populists in government relates to their propensity for authoritarianism.Footnote 72 Although populists advocate the “will of the people,” champion the use of democratic procedures such as elections and referendums, and give voice to politically marginalized sections of society, they are likely to erode liberal-democratic principles while in government. Populists emphasize the rule of the majority at the expense of individual rights. They conceive the people as virtuous and homogeneous at the expense of pluralism. Those who do not fit their conception of the people are excluded using moralistic claims. Their anti-institutionalism undermines the power and legitimacy of democratic institutions that hold executive power accountable, such as courts, the media, nongovernmental organizations, and parliament.Footnote 73 Anti-institutionalism also reinforces the central role of the leader as the embodiment of the people, promoting a personalist regime. Particularly in contexts where institutions are weak and checks and balances are not well established, populist governments are likely to turn authoritarian.

The shift of populists toward personalist rule and authoritarianism comes into tension with their emphasis on popular sovereignty and representation. Concentration of power by one leader would not only limit the claims about the opposition, whom populists attack as representatives of “the establishment,” but also may hurt their own constituents by diminishing their access to power and assertion of interests, putting the coherence of populist constituents and public support for populists at risk. Appealing to constituents through emotional performances that dramatize the threat and crisis rhetoric can be seen as a strategy to justify growing authoritarianism. In addition, emotional appeals can be tools of identity consolidation and political mobilization of populist constituents against a growing opposition.

In Turkey, the shift to authoritarianism under the AKP government has been well documented. The party created a dependent and compliant judiciary, took the mainstream media under its control, built a loyal business class, eroded the distinctions between the party and the state, imposed significant restrictions on civil liberties, and skewed the electoral playing field in its favor.Footnote 74 Concurrent with growing authoritarianism, Erdoğan also increasingly concentrated power at the expense of his party's apparatus and his alliance with the Gülen movement. Particularly after the Gezi protests and the 2013 graft probe, he accelerated neutralization of the internal opposition within his party and the purge of Gülenists from the state. After the failed coup, the emergency rule allowed him to concentrate power further through the use of executive decrees without legislative oversight. The personalization of power not only hurt the opposition but also led to intra-Islamist struggles that hurt the solidarity and coherence of the AKP constituents.Footnote 75 The government undertook a massive crackdown on the Gülen movement, which it held responsible for the coup attempt. This crackdown alienated part of the previous AKP voting bloc. After the coup, the government purged more than a hundred thousand of its opponents from the state bureaucracy and the military, imprisoning about a third of them.Footnote 76 A large section of them were purged due to their alleged links to Gülenists. The fragmentation of the AKP's constituency pushed Erdoğan to form an alliance with the extreme right Nationalist Action Party (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi, MHP) in an attempt to unify the conservative-nationalist bloc before the 2018 general election.Footnote 77 The resignations of the former Economy Minister Ali Babacan and the former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu from the AKP and the launch of two political parties under their leadership revealed the discontent with Erdoğan's personalization of power within the AKP. I contend that the increased frequency of crying by Erdoğan in public is closely related to the context of the growing authoritarianism of the AKP government.

After the Gezi protests, most of Erdoğan's public emotionality has been a way to accentuate the discourse of victimhood mixed with anti-Western conspiracy theories. Erdoğan has accused foreign agents and lobbies of inciting the protests in an attempt to prevent Turkey from being a powerful regional leader. This emphasis on victimhood, which was relatively latent during the AKP's early years, became more pronounced as Erdoğan began to concentrate more power in his hands.Footnote 78 The aborted coup in July 2016 gave Erdoğan an opportunity to further emphasize his victimhood and the vulnerability of Muslim constituents. After the coup attempt, Erdoğan and members of the AKP often cried in public during the commemoration ceremonies for “martyrs” who died during the popular resistance against the coup, defending the government.Footnote 79 This emotional style of communicating with constituents serves to dramatize the threat and crisis rhetoric. It also reminds constituents of the importance of solidarity in the face of continuing threats and the necessity of government repression.

Public emotionality can be seen as a mechanism of identity building. For those who sympathize, it solidifies fellow feeling, separating them from those who do not understand. As Sara Ahmed states, “emotions create the very effect of the surfaces and boundaries that allow us to distinguish an inside and an outside in the first place. So emotions are not simply something ‘I’ or ‘we’ have. Rather, it is through emotions, or how we respond to objects and others, that surfaces or boundaries are made: the ‘I’ and the ‘we’ are shaped by, and even take the shape of, contact with others.”Footnote 80 The act of crying also is an otherizing mechanism. It defines the out-group because it points to the perpetrators of injustice and suffering. Tearfulness has an interpersonal function. Because it communicates an intense emotion, it demands attention and understanding from its audience.Footnote 81 People usually cry in the presence of a sympathetic audience that is likely to provide an empathic and cooperative response. Crying “promotes prosocial responses in others. In this way, this signal facilitates feelings of connectedness and, consequently, promotes social bonding.”Footnote 82 For AKP partisans, crying with Erdoğan or for Erdoğan has become an identity marker. For instance, two columnists began to weep on TV while listening to the call to prayer that Erdoğan gave on the morning after the coup attempt.Footnote 83 The contagious effect of crying also can reinforce its social bonding impact. With his tearfulness, Erdoğan often has provoked tears in his audience and the people around him.Footnote 84 Weeping in public can be seen as an attempt to make AKP support a “felt identity.”Footnote 85 The increased frequency of Erdoğan's public weeping can be attributed to the need for identity consolidation in the face of the growing fragmentation of AKP constituents.

Finally, crying in public also can be seen an attempt at political mobilization, with a goal of evoking feelings of anger and revenge within the AKP constituency and underlining the importance of its devotion to the cause. The majority of Erdoğan's crying after the Gezi protests reacts to and amplifies a narrative of injustice. As such, it is a display of rage against the perpetrators of injustice. When Erdoğan got teary-eyed on live TV watching scenes of suffering patients in old Turkey's hospitals, he was expressing his anger against his political rival, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, who was the head of the Social Security organization in the 1990s. In a similar vein Melih Gökçek, an AKP politician who served as the mayor of Ankara from 1994 to 2017, cried in a TV interview at the time of the Gezi protests. “These tears are because of my fury,” he said. “We are all Muslims and believe in God. Our God is with us and we don't fear anyone but God. . . . They played with us until today. My God can give them such trouble that they would be surprised.”Footnote 86 Portraying the AKP government as the representative of Muslims, Gökçek equated the heavy-handed state repression of the protestors with the fury of God. A year later, he shed tears expressing his dismay about calls to vote for the main opposition, the Republican People's Party's candidate, in the local election campaign. “Who closed the Qur'an schools? Who closed the Imam Hatip (religious vocational schools)? How could you vote for that party?” he asked with tearful eyes.Footnote 87 Tears accentuated his anger toward the opposition, seeking to mobilize voters against it.

The public appearance of vulnerability and fragile emotionality contains an implicit legitimization of revenge and harsh measures against opponents, some of whom were ex-supporters of Erdoğan.Footnote 88 As Erdoğan frequently declares in his speeches, “We won't turn the other cheek to those who slap us.”Footnote 89 While Erdoğan was shedding tears on live TV for those who died during the coup attempt, the chyron displayed something he had said: “Showing compassion to oppressors is a betrayal to the oppressed. We will protect the rights of the oppressed.” The quotation was referring to the Gülenists, oppressors who would not be forgiven. On the first anniversary of the coup, Erdoğan became teary-eyed on stage while his wife and other members of the AKP wept in the audience during the ceremony commemorating those who died fighting the coup attempt. Addressing his supporters who attended the ceremony, he declared that the coup attempt was not the first and would not be the last attack against Turkey by terror groups supported by outside powers. He promised “chopping the heads off the traitors” and reinstating the death penalty.Footnote 90

As an expression of anger, crying calls for political mobilization in support of Erdoğan at a time when his growing personalization of power puts the solidarity of AKP constituents at risk. Anger is a crucial emotion for political mobilization because it emanates from a sense of injustice that is necessary for collective action. As Jasper states, “Without outrage over an injustice, without a villain to blame, there simply is no cause.”Footnote 91 Anger boosts political participation, promotes a demand for a corrective response, and increases support for punitive and aggressive policies because they are accompanied by the sense that one has some capacity to address the unfair situation that is externally caused by an identifiable, specific agent.Footnote 92 Reminding the AKP constituents of the ongoing threats, evoking a sense of injustice with a performance of crying ascribes blame and demands punishment of the opposition. It is an attempt at legitimation and arousing anger to encourage political mobilization in support of Erdoğan's growing authoritarianism.

Erdoğan's tears also call for aggression and mobilization by playing on masculine sensitivities. In several instances, Erdoğan's tearfulness is a reaction to women's victimization. The suffering of women in headscarves in old Turkey, grieving women whose husbands or children died during the coup attempt, and the sacrifices of poor women bring tears to Erdoğan's eyes.Footnote 93 By showing compassion for victimized women, he demands contempt and outrage against the perpetrators of women's suffering. In such contexts, crying reinforces Erdoğan's masculinity and seeks to mobilize aggressive assertions of power (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Erdoğan crying over a video about martyrs' mothers at an event celebrating International Women's Day in 2020. (“Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan Gözyaşlarını Tutamadı,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=42whAmYAKNc; accessed 15 September 2020).

Conclusion

In this article I have argued that the public tearfulness of Erdoğan and other members of the AKP can best be understood as a feature of populism's performative repertoire. Populists present themselves in dramatic, attention-grabbing, emotional, and unconventional ways to signal their closeness to the people and to project an image of authenticity. This does not mean that all self-presentation by populists is the same. The substantive content of populist performances can vary from one context to another depending on symbolic and cultural resonances and how the populist defines “the people.”Footnote 94 Conceptualizing populism as a stylistic repertoire can help us identify and understand creative and novel styles of populist self-presentation that respond to different local contexts and the particular political problems encountered. Crying in public is an innovative style of communication, but it is not unique to Erdoğan. Other populist leaders, such as Vladimir Putin of Russia and Narendra Modi of India, also have had repeated instances of crying, albeit not as frequently. Once it was the Russian national anthem at a diplomatic ceremony that triggered Putin's emotionality. Another time he cried during the Police Day ceremonies while listening to a song about the bravery of the police force.Footnote 95 Modi wept after he was elected leader of the BJP parliamentary party, when his party won in elections in Gujarat, and during a speech, talking about the personal sacrifices he had made for his nation.Footnote 96

Although this study focuses on Turkey, it has broader implications for the function of populism. Populists heavily rely on emotional appeals to connect with their constituents and build public support. Understanding the relationship between populism and emotions requires examining not only populist discourse but also performative and aesthetic practices that can have a powerful impact on constituents. Emotional performative practices can help populists in power address an increasing gap between their rhetoric and practice. I have argued that an increase in emotional expressiveness relates to two dilemmas that populists in power encounter. First, it helps communicate a message of closeness to the people and sustain the anti-elite rhetoric when populists become the new political elite. Second, it can work to justify authoritarian practices while sustaining the claim to rule in the name of popular power. Another implication of this study is that, the longer populist politicians remain in power, the more likely they will be to resort to emotional appeals discursively and performatively to signal proximity to the people and to construct a sense of crisis and threat in an effort to legitimize their rule.

The AKP's electoral success and its ability to mobilize the masses cannot be understood without its emotional appeal. Public opinion surveys and in-depth interviews show that AKP voters are highly leader-oriented.Footnote 97 They vote for the party because of their support for Erdoğan and express this support emotionally. They claim unconditional loyalty and love for him. They attribute blame to external actors, rather than to AKP or Erdoğan's failures.Footnote 98 They state that they admire Erdoğan for his sincerity, bluntness, sudden reactions, humbleness, and self-sacrificing nature. They express anger and hatred toward the main opposition parties, the CHP and the People's Democratic Party (Halkların Demokratik Partisi, HDP), the Gezi protestors, and the 2016 coup organizers.Footnote 99 AKP voters also state that the Gezi protests resulted from a conspiracy against Turkey and that outside forces are responsible for causing economic difficulties. They are largely in support of the government's control over the media and limitations on basic rights and freedoms.Footnote 100 These studies suggest that Erdoğan's emotional appeals have been successful with his supporters.

Far from legitimizing the AKP's rule broadly, however, Erdoğan's populist style divides the society further. Symbolic and performative practices can exacerbate political tension because they generate strong emotions. Survey results indicate high levels of political polarization in Turkey. In 2017, 60 percent of CHP voters and 51 percent of HDP voters stated that they would never vote for the AKP. Sixty-one percent of CHP voters and 63 percent of HDP voters thought that the main social tension was between Erdoğan supporters and opponents. According to 82 percent of CHP voters and 83 percent of HDP voters, Erdoğan has become more authoritarian and repressive.Footnote 101 The AKP's populist style has provoked increased politicization of society by evoking strong and conflicting emotions among its supporters and opponents. The result is a highly polarized and emotionally charged society, presenting ample opportunities for further political unrest.

Acknowledgments

I thank Ayça Alemdaroğlu, Ceren Belge, Francesco Duina, Reşat Kasaba, Tülay Kılıçdağı, Joel Migdal, Hale Yılmaz, and especially Jason Scheideman for their helpful comments on the earlier drafts of this article. I am also grateful for the suggestions and critiques of Joel Gordon and the anonymous reviewers from IJMES. This article builds on an earlier memo that I prepared for a workshop on Turkish politics, organized by the Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS) at Rice University in 2016. I thank the participants in this workshop as well as the participants of Understanding Turkey Conference at Stanford University, and of my talks at Northwestern University, Wesleyan University, and Bates College.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743820000859