In the summer of 2012, the Israeli Ministry of Agriculture was at the peak of its announced policy endeavor to achieve sustainable agriculture.Footnote 1 A marker of policy change was the ministry's choice in 2012 to fund a program of sustainable agriculture for Palestinian-Arab communities in Sahl al-Batuf/Beit Netofa Valley in the Galilee.Footnote 2 This pilot program aimed to develop a smaller area of al-Batuf called Maslakhit. In the years that followed, a larger sustainable development regional plan for al-Batuf/Beit Netofa was advanced by the Ministry of Agriculture in planning procedures in the state's Northern District Committee for Planning in 2013–18. The Sahl al-Batuf/Beit Netofa area comprises a seasonal wetland formed in winter floods and a biodiversity hotspot sustained through what officials call “traditional agriculture” on small agrarian plots. State ecologists are enthusiastic about preserving this area due to its ecosystem and landscape characteristics. About the program for Beit Netofa, Ofer, a new ecologist at the Ministry of Agriculture, said:

We did not think of them [Palestinian-Arabs of al-Batuf] at all, and then they submitted a proposal and we said, Wow [enthusiastically], those little agricultural plots, rain-fed agriculture, they don't use pesticides, a community atmosphere where everyone goes in the afternoon to the valley, it is exactly what we wanted! It is “Agriculture that Supports the Environment” [naming the new funded program]. Footnote 3

Ofer then detailed with conviction some aspects of the program for Beit Netofa: conserving biodiversity, training farmers in sustainable agricultural methods, and holding public participation meetings with local stakeholders. He also clarified that it would most likely not include draining the seasonal flood. He hoped that the agriculturalists would not be disappointed by the lack of drainage, as they perceived it as the highlight of a previous failed development plan.

Ofer's sentiment toward the valley's atmosphere encapsulates a noticeable change in the agricultural-environmental imaginary he—as well as the Ministry of Agriculture—can see. Environmental imaginary refers to the ideas that groups of people develop about a given landscape.Footnote 4 A land's imaginary holds notions of temporality and spatiality.Footnote 5 For instance, why is a landscape in its condition, how long has it been like this, what is its ideal state? The image of al-Batuf/Beit Netofa about which Ofer was so enthusiastic transforms the prevalent Zionist imaginary of large, rapidly productive, and “efficient” agricultural fields typically cultivated by Jewish cooperatives such as kibbuztim or moshavim. This model of agriculture entails science, technology, fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation. These agricultural resources and techniques enhance growth and compress production in both time and space, making agriculture less dependent on natural cycles and constraints. By contrast, Ofer admired small plots, seasonal water, and cultivation. His vision enfolded a temporality: a duration of a continuous community cultivating together, assuming long-term land tenure and agrarian cycles. Ofer recognized agriculture's multifunctional roles aside from food production—preserving landscape and environment, as well as maintaining culture and social values. Policymakers have now begun to value these roles. Also noteworthy was the shift in the agrarian plan for al-Batuf that was considered relevant for twenty years: from modernizing agriculture through drainage infrastructure to a new program that held a future image of the site without drainage and preserving “traditional agriculture” through agroecological management.

These new time-space images are a product of the perceptions of sustainable agriculture but are not limited only to these perceptions. There are important temporal-spatial frames at play entangled with the ethno-national/colonial relations between Israel and its Palestinian-Arab citizens.Footnote 6 As encapsulated in this vignette concerning Ofer, the new agriculture plan encompasses a shift in the historical approach of the Zionist establishment toward Palestinian agriculture. From the late 1920s through the early 2000s, officials from Zionist institutions and later the Israeli state predominantly denigrated Palestinian-Arab agriculture for its lack of efficiency and primitive methods.Footnote 7 Such temporal-based contempt for the peasantry is not unique to this case, but is reported within a wide range of colonial contexts and their states’ discursive legacies.Footnote 8 This article will problematize these temporal-spatial frames, examining them as a form of governmentality that is carried out through newly formulated sustainable agriculture policies. I ask the following questions: What is new about these policies of sustainable agriculture? Why do officials suddenly admire “traditional” Arab agriculture? Is there a change in the relationships between the state and its Palestinian-Arab citizens? What can this tell us about governance through time in environmental plans and policies?

I argue that the formation of Israeli agricultural sustainability policies for al-Batuf encapsulates timescapes (the embodiment of approaches to time and the relations between time and space)Footnote 9 as tools for governing people, land, and the environment. The argument that time is a social construct and a tool of governance for those holding power is not new.Footnote 10 However, it has not received the ethnographic attention that it deserves.Footnote 11 Rather, anthropological studies of time have predominantly focused on phenomenological and cultural approaches to time.Footnote 12 The contribution of this article is to elucidate how time is used for governing in the context of an environmental plan.

Time and timescape as political tools were not the starting point of this research. My ethnographic fieldwork took place during 2012–14 in official state meetings and nonofficial contexts in which sustainable agriculture programs for al-Batuf were discussed. I analyzed policy minutes and scientific reports and interviewed officials who produced policy materials as well as the agriculturalists who were affected by and at times resisted them. In my fieldwork, I noticed that various interlocutors discussed policy for al-Batuf/Beit Netofa through multiple notions of time embodied in this site. Searching for a language that describes what I witnessed, I discovered the notion of timescape. Let us clarify this term.

Whereas time permeates every aspect of our reality, its effect on us is often invisible. Barbara Adam formulates timescape as the interaction of the spatial view of life's activities with its temporal aspects.Footnote 13 She stresses that timescape sheds light on practiced approaches to time, marking its embodied form. A central aspect of timescape is the interdependence of time and space.Footnote 14 Jon May and Nigel Thrift elucidate the time–space relation in their four-component framework.Footnote 15 They attend to rhythms of activities occurring across time and space, such as seasonal cycles or shift-based employment. They also address systems of social discipline transgressing time and space, such as the workplace as a space of “productivity” versus home as a space of “rest.” Another component of their framework comprises the instruments, technologies, and devices, such as a telephone or a train, that compress time and space.Footnote 16 Finally, there are textual and visual representations that encapsulate activities of time-space. May and Thrift's framework shifts our focus to multiple manifestations of time stretching across one social space.

In her recent review on time in anthropology, Laura Bear calls for an anthropology of timescapes that follows May and Thrift's framework. She shows that anthropological research tends to address time in separate modes of exploration: time as knowledge, time as technique of imagination and agency, and time as a form of ethics.Footnote 17 Bear posits that the prevailing research distinctions between spheres of time disregard the possibility that they are often parallel and dialectical. Drawing on Bear's critique, this article examines how timescape works in practice. In al-Batuf/Beit Netofa's planning policy multiple networks of time manifest and enable us to see how time functions as a tool of power. By “planning policy” I mean the formulation, content, and implementation of spatial-agricultural-environmental public policies.Footnote 18 Moving beyond the question of which notions of time are at play in these policies, I address the work of different timescapes as bureaucratic tools of governance.

The al-Batuf case demonstrates diverse technologies of governance. First, governmental institutions manipulate time as a form of power. For example, the bureaucratic procedure and its bureaucratic delay are a perpetual mechanism that enables policymakers and planners to reach what they consider a desired plan for Beit Netofa. Second, state officials use various forms of knowledge that express time conceptions as a tool of governing. They also control the time it takes to reach the necessary knowledge. Third, state bureaucrats use temporality as an ontological and ethical arrangement of governing. More specifically, officials depict the al-Batuf/Beit Netofa landscape as an ancestral wetland, thereby constructing it as a site in need of preservation. The intervention I offer is quite straightforward: I claim that these different temporal forms—time as knowledge, time as a bureaucratic technique, and time as ontology and ethics—are all intertwined rather than separate, and they serve as one mechanism of governing through timescape. A timescape perspective highlights the substance of time, which is otherwise abstract, and offers tools to better understand and criticize environmental power, inequality, and dispossession occurring through spatio-temporal mechanisms.

By stressing that governing occurs through multiple timescapes, this article also contributes to current discussions of the environment in the Middle East. Recent scholarship has shed light on the ways Middle Eastern environments were imagined and managed by European powers. These works show how nature “improvement” and technopolitical resource management programs were based on orientalist, spatio-temporal suppositions and assessments about the region's environmental past, viewing the Middle East as a “cradle of civilization” and aiming to rehabilitate its “biblical landscapes.”Footnote 19 This new body of literature, mostly developed by historians, contests the declensionist perception that the region prospered in ancient times and became a desolate desert or a deforested land because of poor management by native populations. Thus, these studies challenge prevailing Western narratives and show that colonial environmental imaginaries of a decayed environment served European political control and resource extraction.

Still, dominant scholarship on environmental histories of Israel/Palestine continues to adopt the same declensionist narrative of environmental degradation caused predominantly by natives. These works depict an Israel that prospered in biblical times, was later ruined by its natives, and was finally rescued by European powers, both British and Zionist, in 20th-century Palestine/Israel.Footnote 20 The story I present challenges this mainstream perspective.Footnote 21 Bringing anthropology of time and environmental anthropology in discussion with historical writing,Footnote 22 I show that in Israel/Palestine, development projects initiated by the Zionist movement caused the eradication of wetland habitats, considered one of the most endangered habitats in the world.Footnote 23 The story of al-Batuf highlights that it is through agricultural cultivation by Palestinian small households, so patronized in the past by the techno-scientific Zionist movement, that a wetland habitat survived and thus the historic narrative concerning the land's stewards is upturned.

The article begins with a review of the intersections of governance, timescape, and environment. It continues with a political history of al-Batuf/Beit Netofa basin's agriculture and an ethnographic exploration of the recent timescapes of sustainable planning and policies for al-Batuf. It then concludes by highlighting the utility of a timescape analysis.

INTERSECTIONS OF GOVERNANCE, TIMESCAPE, AND THE ENVIRONMENT

There is a dearth of detailed ethnographic work on the role of time in governance. Studies discussing governance through time predominantly attend to the role of waiting as a modern state practice of subduing subjects. For instance, Javier Ayuero argues that in Argentina the practice of making the poor wait for resolutions to their problems subordinates them and reinforces their state of neglect, an observation repeated by Smadar Lavie in regard to Mizrahi single mothers in Israel.Footnote 24 Abdellah Hammoudi, in discussing the multiple forms of waiting required in Morocco to receive the paperwork needed to make hajj, describes state bureaucrats as “the masters of time.”Footnote 25 In these accounts waiting as a form of subordination takes place in corridors, waiting rooms, and antechambers. Hammoudi sheds light on additional modes of waiting, not only to meet a clerk at the end of a waiting line, but also between the minutia of procedures, and for information and forms given piecemeal rather than freely.

In contrast, Nayanika Mathur argues that citizens in India must wait not because of a subordinating technique but instead because of contradictions between the timing of procedures and different long-term temporal aims of diverse state institutions.Footnote 26 She shows that the state apparatus does not work in harmony and that citizens are often forced to wait for state institutions to settle their disputes. My observation echoes these insights and expands on the implications of bureaucratic delay as a form of governance. I place waiting in a larger bureaucratic timescape, both in its duration and in its spatial location. I show that governing through waiting happens not only in the corridor, but also, as in the case of al-Batuf, in the entire basin. In contrast to Mathur's observation, I demonstrate that although the conflicting rationales of ministries do contribute to delays in decision making, they also serve as a procedural strategy, masking the work of time and perpetual delays and inefficiency as a tool in governance.

In the context of Israel/Palestine, recent scholarship has begun to address Israel's theft of Palestinian time through the multiple forms of waiting imposed upon Palestinians, such as waiting for permits and at checkpoints.Footnote 27 This scholarship indicates that the Israeli ethno-national colonial project is not only a spatial one but also a colonization of Palestinian time. These insights were drawn from the experiences of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza but have not yet been used to examine the experiences of Palestinian-Arab citizens of Israel.

These accounts of waiting as a form of power address both the lessons of submission learned by the subjects of rule, and often their refusal to wait as a resistance practice. In the West Bank, examples include Palestinians driving through alternative routes to escape a checkpoint car line or the Palestinian Authority's 2003 enactment of daylight savings a week before Israel as an act of sovereignty.Footnote 28

Another prominent mode of addressing governing through bureaucratic timescapes focuses on manipulations, elusive promises, and securitization of the future. Here I concentrate on these future-oriented techniques in spatial and environmental realms. The planning and management of environments and spaces are linked with the modern nation-state's modes of expertise.Footnote 29 The practice of planning is a major expression of state governance, its rationality, and its promise to improve future conditions for its citizens. In terms of the bureaucratic timescape, it plays a significant role in facilitating tax collection and state surveillance. State planning is the ultimate expression of “modern time.”Footnote 30 Associated with temporal conceptions of linear progress, planning is grounded in promises and visions of better futures, though it has been widely criticized as a practice that generates spatial and social injustice.Footnote 31 These critiques of planning have undervalued the multiple notions of timescape that are a central technique of power in the planning process itself.

Simone Abram's anthropological works on planning offer a critique of the planning process’ temporalities. She encounters two central temporal planning problems: first, the gap between the future intention of a plan and the lived reality of a citizen; and, second, the time (duration) that planning takes in participatory planning processes. When citizens execute their right to further inquire on state or regional plans, they invoke the temporality of doubt over the temporality of the plan's presumed promise to improve the future.Footnote 32 In another critique of the temporality of planning, Richard Baxstrom suggests that planning is a form of governance that functions as a domination vehicle in the present, gesturing to “the future” without requiring “the future” to reach its goals.Footnote 33 His suggestion highlights the elusive promise of the plan—it is a tool of outward social improvement, acting in the present as a declaration that implies a better future—but it does not need to reach the future in order to fulfil its governing role as a promise. This insight on the symbolic and declarative role of plans elucidates why oftentimes they are neither approved nor applied.

Although scholarship has paid little attention to timescapes and temporalities of planning, the precarious global environmental moment has led to a significant rise in studies about “the future” as a technique of power. Focused on states and bureaucracies, these studies have emphasized the multiple technologies associated with the use of the future as a form of governance. For example, the idea of the future is enacted in the bureaucratic management of problems of risk, biological-environmental catastrophes, and uncertainty. These works address the employment of scenario-based exercises in governance or the state of anticipation related to biological risks,Footnote 34 threats associated with climate change,Footnote 35 and uncertainty and risk in the relations between humans, animals, and their common environment.Footnote 36

Other studies have problematized the future in the context of measuring renewability or finitude of resources.Footnote 37 These ethnographic accounts demonstrate the growing prominence of modes of techno-scientific expertise and calculation governance in bureaucratic timescapes and the decreasing role of citizens in environmental political decisions. Thus, Andrew Mathews and Jessica Barnes argue that modeling and interpolating the future of resources and environments has evolved into a main feature of current environmental politics.Footnote 38 My analysis draws on these works to consider the use of the future in the al-Batuf conservation project. I show that temporalities of sustainability politics are not only geared toward the future but are also constantly intertwined and fused with those of the past. I consider the future as a technique manifested in the risk of endangered species extinction in al-Batuf. The future is also employed in the ethical timescape of saving species from extinction in comparison with the low efforts geared toward improving conditions for certain human populations, in this case Palestinian citizens of al-Batuf. Finally, I highlight the timescape contents of the new policy plan, such as the sorts of knowledge that inform it and the temporal ethics that the process highlights. Let us now turn to the field.

THE BASIN OF AL-BATUF/BEIT NETOFA

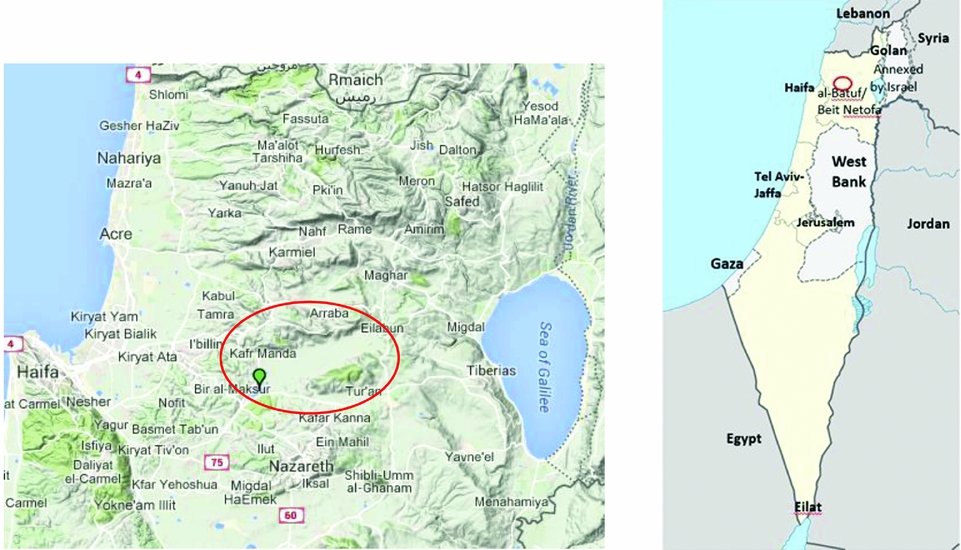

Sahl al-Batuf is an agricultural terrain of 60,000 dunums located in the lower Galilee (Figure 1). Its valley, surrounded by escarpments of 350 meters, creates a basin. Most of the agricultural land of this terrain belongs to Palestinian-Arab citizens of Israel who reside in eleven neighboring towns with a collective population of nearly 100,000 inhabitants. Until the 1970s agriculture was a main source of income for these communities, but agriculture's economic role has decreased due to a few interlocking factors: a decline in the status of agriculture in Palestinian-Arab society,Footnote 39 an increase in labor opportunities outside of Palestinian-Arab towns,Footnote 40 and, more importantly, land dispossession experienced by these communities since 1948.Footnote 41

FIGURE 1. Location of Sahl al-Batuf/Beit Netofa Valley within Israel and Israel/Palestine.

Following Israel's establishment, the land tenure regime changed dramatically to serve the settler society's land control and development. Studies in law and political geography have comprehensively discussed the legal mechanisms that facilitated the state's appropriation of Palestinian-Arab lands in Israel during the military regime of 1949–66; these dispossession mechanisms affected the towns surrounding al-Batuf basin.Footnote 42

The second wave of land appropriation took place during the 1970s based on the policy of “Judaization of the Galilee.” This program aimed to shift the Palestinian-Arab majority demographic of Galilee by settling more Jews in small community settlements planned to spatially and demographically divide Palestinian-Arab settlements from each other and restrict the possibility of a spatial continuity between Palestinian-Arab towns and their potential demand of autonomy. This settler-colonial policy was based on unequal development mechanisms and the appropriation of land in thousands of dunums from most of the towns around al-Batuf, most significantly Sakhnin and ʿArraba.Footnote 43 The program also granted half of the municipal jurisdiction of al-Batuf to the Misgav Regional Council, the municipal body of the new settlements, restricting, until today, the independent planning of the Palestinian-Arab municipalities. Presently, the Palestinian-Arab landholders of al-Batuf towns have only 30 percent of their historical pre-1948 land.Footnote 44

The scarcity of available agricultural land is also attributable to the Muslim tradition of land distribution upon inheritance. The agricultural plots of al-Batuf have been divided with each new generation. Thus, the current titles to property are small, characterized by an average of one to five acres per owner. The area's inhabitants estimate that there are hundreds of residents who cultivate plots in al-Batuf, and that there are close to 6,000 landowners. As in many other global localities, the current size of agricultural plots is insufficient to make a living. Thus, the plots are used for part-time farming to produce goods for domestic consumption and leisure. Only a minor group of approximately thirty agriculturalists depend on farming for income in al-Batuf, leasing a few plots from acquaintances to produce a greater agricultural income.

Agriculturalists typically cultivate wheat, barley, hay, sesame, clover, vetch, onions, garbanzo beans, peas, okra, squash, and tomatoes, as well as some local species of fakus cucumbers and melons. The local wheat and sesame seeds are varieties rarely grown outside of Palestinian-Arab communities, so the crop diversity of the valley enables a domestic market for selling agricultural products that are not commonly produced anymore in Israel/Palestine.

The Israeli state's high development and settlement projects have caused irreversible changes in the land and are characterized by industrialized and monoculture agricultural landscapes. Therefore, policymakers, ecologists, and planners have portrayed Beit Netofa as a unique landscape that preserves traditional agriculture and rare wetland ecosystem characteristics. According to these officials, the landscape's attractiveness is even greater when the floods occur and produce a lake where small islands come up from the flooded valley. The updated ecological surveys undertaken by Israeli environmental bodies found in al-Batuf many endangered species of plants, amphibians, and birds, including those listed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature's (IUCN) Red List, implying the highest level of extinction risk.

At the heart of the state's agroecological planning dilemma stands a question about the approach toward the recurrent floods in the valley and their ecological and social implications. In rainy winters, the eastern side of the valley becomes flooded. Occurring a few times per decade, the floods cause severe agricultural damage because the valley's eastern side has no natural or artificial drainage. The combination of recurrent floods and small plots, characterized by vegetation at the margins, has enabled the preservation of a wetland ecosystem and habitat for endangered species. Therefore, over the last twenty years, ecological and landscape conservation arguments have become central to discussions of the development of al-Batuf.

The Palestinian-Arab proprietors whom I met during my fieldwork mentioned that the lake landscape mostly serves the Jewish inhabitants of the area who maintain tourist accommodations on the hills surrounding the valley, while the Palestinians suffer agrarian-economic loss. Frustrated by this condition, some of them have invested significant resources in transporting soil to elevate their plots by up to half a meter, decreasing their vulnerability. Such a solution may be helpful in low rain and low flood years but it also manifests the importance of agriculture and its yields in social-cultural and heritage terms.

Since the establishment of Israel, water (and land) has been a nationalized resource, controlled and allocated by the state. As a part of this state system, Israel constructed the national water carrier during the period 1953–64 aimed at transporting water from the country's north to its south, as part of the Zionist project to “make the desert bloom” with settlement and agriculture. The national water carrier passes at the center of al-Batuf/Beit Netofa valley along sixteen kilometers (ten miles). In other sites along its route, the water carrier is closed in a piped tunnel. In al-Batuf the water carrier is an open water canal, fenced with wire from its two sides, symbolizing to the Palestinian-Arab landowners both the power of the state and the deprivation of irrigation water to Palestinians. In Israel agriculturalists have access to water for agriculture at a reduced price only by belonging to a cooperative water association that creates the irrigation allocation infrastructure and communally pays bills to the water authority. This is a social-economic model that was mainly structured around the rationale of kibbutzim and rural moshavim cooperative settlements. In the 1960s, the state invested in promoting the creation of Palestinian-Arab water associations, but this happened mostly in Israel's central areas, while in the Galilee there are presently only a few water quotas for Palestinian-Arab agriculturalists. Historically, the social-economic model of a cooperative was not a prominent Palestinian social mode of organization; thus, Palestinian cooperatives did not flourish.Footnote 45 However, al-Batuf agriculturalists told me that when the Ministry of Agriculture advanced a program for modern agriculture and drainage in the 1990s (a program that, as the next section will discuss, was never implemented), al-Batuf agriculturalists organized into agricultural associations to advance a water allocation plan—a plan that ultimately failed.

Scholarship has shown that the low levels of water allocation for Palestinian-Arab agriculture in Israel constitutes straightforward discrimination.Footnote 46 The landowners in the valley see it this way too. Cultivators in al-Batuf told me that seeing Israel's National Water Carrier in the valley is like leading a thirsty camel in the desert, showing him the water, and preventing him from drinking. In contrast, on the western side of the valley, the Yodfat Jewish-Israeli cooperative moshav has both intensive agriculture and irrigation, as land and water are allocated by the state.

TIME AS TECHNIQUE: THE BUREAUCRATIC PROCEDURE'S DELAY

State boundary-making practices have become an object of study for scholars looking at blurred state apparatuses of the kind evident in Israel.Footnote 47 In the al-Batuf case the blurred apparatus is demonstrated by the Israeli Nature and Parks Authority's (NPA) role in the planning process and in community outreach. The NPA is a governmental organization responsible for managing nature reserves and parks as well as enforcing wildlife protection. Although the NPA is a state body, it is seen in the public eye as one of the “Greens”—the term coined for environmental bodies and activists in Israel that are often perceived as a new pressure group. In the al-Batuf case, similarly to other planning procedures in Israel/Palestine, the NPA plays a primary role in planning politics. However, its interventions are not commonly understood by agriculturalists as restrictions imposed by “the state” but rather as limitations stemming from environmental activists and ecologists, “the Greens.” Consequently, the first procedures of planning that I will discuss concern disagreements between governmental agencies that clarify how state making is a struggle between various rationales. Different state actors who participated in the process contributed their minutes to my research and shared with me the following description of the events.

Between 1994 and 2005, under two different governmental administrations, the Ministry of Agriculture promoted programs to drain the flooded area and create water reservoirs, two actions that would have enabled irrigation and the development of modern agriculture in the valley. These plans were endorsed and celebrated by local Palestinian-Arab stakeholders, who wished to develop agriculture and benefit from their land assets.

Nevertheless, in 2006, under planning processes from the Northern District Planning Committee, the plan was rejected. Members of the NPA halted the drainage plan, which they claimed would have resulted in tremendous deterioration of a unique landscape and the wetland ecosystem. Their knowledge of the planning process enabled them to use procedural claims to further delay the proposed drainage plan. They claimed that this development plan could not be discussed in the Planning Committee through the Drainage Law, under which the Ministry of Agriculture had submitted the plan, but could only be addressed through the Law of Planning and Construction. This latter law requires inclusion of further environmental considerations.

By claiming an alternative bureaucratic channel, the ecologists created an alternative ontology of space-time.Footnote 48 This new ontology implies that more than merely ditches and irrigation reservoir infrastructures are now at stake in the vision for Beit Netofa Valley. It also ensures that potential drainage will not enable agriculturalists to build on their privately owned agrarian land, and guarantees careful zoning plans to secure more ecological involvement, thereby creating a more time-consuming process. The NPA ecologists were successful in convincing the Planning Committee to require an ecological assessment survey from the Ministry of Agriculture. When the ecological survey was presented to the Planning District Committee it was ruled unsatisfactory by the NPA, and so the process was further delayed.

An additional milestone favoring ecological considerations in planning procedures took place in 2005 with the publication of National Master Plan 35. In this plan, Beit Netofa was defined as a “landscape zone,” implying that only cautious and moderate development can be permitted. Didi, a recently retired senior ecologist from the NPA, told me that a final nail was driven into the drainage program's coffin in 2009.Footnote 49 Following lobbying and intervention, the head of the Planning Administration, the highest statutory body for planning in Israel, declared that the Ministry of Agriculture should lead an alternative development plan for Beit Netofa. He conveyed that the new plan should offer a novel and holistic agricultural and developmental approach that includes environmental conservation, and that it should be grounded in the Law of Planning and Construction.Footnote 50 As concluded by the former NPA ecologist, “This is how it all began: I can say that I sort of succeeded in creating the delay process until today, and I am talking to you about a program [the drainage] that started in 1995 and we are now twenty years later.”Footnote 51 The process that this ecologist describes is indicative of the political power that environmental bodies have gained in Israel's planning processes over the past fifteen years. A noticeable shift in the politics of planning occurred through the activism of environmental bodies. However, this shift was not coupled with greater social justice.Footnote 52

This ultimate rejection was fifteen years after the agriculturalists had celebrated the state decision “to drain the swamp.” Yet, once again, on the large planning scale for al-Batuf nothing happened for a few years. It may have taken officials from the Ministry of Agriculture involved in the drainage program a long time to recover from the defeat of the plan that they had worked so hard to advance. Nevertheless, that it took a few more years to propose an alternative program may indicate the extent to which the new plan and its target population were a low priority.

In 2011, some two years after the final drainage rejection, the Ministry of Environmental Protection and the NPA launched a formal cooperative effort to develop a new program for sustainable development in Beit Netofa. Their first official protocol serves as a basis for a comprehensive program for the valley that would replace the prior drainage program.Footnote 53 Simultaneously, the Ministry of Agriculture, together with the Environmental Protection Ministry, funded a program led by local partners from the Beit Netofa Basin Environmental Quality Union in cooperation with the NPA to introduce a small-scale pilot project called “Agriculture that Supports the Environment.” This pilot program intends to bring together a group of fifty agriculturalists working in the Maslakhit area of al-Batuf to introduce them to environmental agriculture methods that can contribute to conservation.

The contemporary planning layout, approved in the Northern District Committee in March 2014, suggests moderate agricultural development should take place accompanied by policy tools that will contribute to the agriculturalists’ welfare and major habitat conservation efforts. This approach is innovative for Israel's agricultural policies insofar as it shifts the focus away from agricultural development and toward environmental conservation as well as development initiatives less likely to produce adverse environmental effects. Nevertheless, while planning procedures that promote environmental conservation were already undertaken in statutory planning, more innovative planning measures, such as agriculturalists’ environmental payment schemes, have not been implemented. This means that measures to support the development of Palestinian-Arab agriculture are almost nonexistent. What is the impact of these long bureaucratic procedures?

Agriculturalists told me that the result of the long policy process is alienation from the land. As ʿAli, the head of the Agriculturalists’ Committee of Sakhnin, explained to me during the summer of 2014:

How many years can you talk about planning? Can someone announce that he is getting married and it will take him twenty years to do it? They are postponing until people come to a mental state where they feel that there is no solution, no progress, and then they leave their land.Footnote 54

Agriculturalists have left their land due to stagnation and lengthy wait times for development implementation or have leased it to a neighbor able to cultivate a greater area. But agriculturalists are abandoning their land for other reasons as well, including the economy of scale, better income in an alternative form of employment, and the ever-deteriorating image of agricultural work in the view of many Palestinians in Israel. Nevertheless, ʿAli's despair well embodies the ethnographic claims that waiting and agreeing to wait are a means of governmental exertion of power and its acceptance.Footnote 55

Governmental authorities have been stuck in a circle of constant planning for more than twenty years, with almost no implementation aside from the small pilot program in the Maslakhit area started in 2013. However, the Maslakhit area covers 1 percent of the whole area, and Maslakhit is used by fifty stakeholders among a few thousand land owners. Iftah, another senior ecologist from the NPA, told me in the fall of 2014 that once the drainage program was rejected it was no longer in the NPA's interest to delay the development program.Footnote 56 Indeed, once drainage was ruled out, the NPA was the only body working to create alternatives on the ground with partners in the valley. Then whose interest does it serve to work so slowly?

The Ministry of Agriculture claims that the Ministry of Interior is responsible for creating constant delays in advancing this program. During my fieldwork in 2013–14, I participated in meetings of the Ministry of Interior's planning committees where Beit Netofa Valley was discussed. These meetings often seemed like a bad joke about how bureaucratic power is used by officials, only it was reality. The timescape of using the bureaucratic procedure and delay as a technique of ruling al-Batuf/Bikat Beit Netofa was manifested once again. The head of the Northern Planning Committee was able to hold time in governmental meeting rooms to repeatedly make irrelevant remarks that brought all participants into a state of despair. Additionally, not all of the meeting's participants received in a timely manner the materials that were supposed to be discussed. Representatives of the Palestinian-Arab towns surrounding al-Batuf basin, for instance, received them only at the last moment. Having less time to prepare for such a meeting obviously restricts one's ability to influence it, yet when these representatives had few comments to make they were portrayed as disengaged from the process. Using Foucault's argument on how governmental techniques make the state as much as they are deployed by it, development scholarship has shown how “participation” is a means of governance that facilitates forms of governmental contact with marginalized populations. Aside from inviting representatives of Palestinian-Arab towns to the planning meetings, state planners did not seem to consider involving representatives of Palestinian-Arab towns in any serious way.Footnote 57

I suggest that these various forms of time as technique enacted in the bureaucratic delay might have been a demonstration of acting as “the State” following the ethno-national/colonial bureaucratic logic.Footnote 58 According to this logic, there is always a delay actor generating the governmental agency,Footnote 59 thereby contributing to stagnation and the despair of the agriculturalists. Although it is commonly known that bureaucratic procedures take time, and Israel's planning system is criticized for this aspect, the procedures are not that exhaustively long. This planning process is taking place during a paradigm shift in agriculture and planning from productivist to postproductivist sustainable agendas of agriculture, and making a system work together under new assumptions does take time. However, among governmental bodies in Israel there was always someone who put up obstacles to the process. This is the timescape of bureaucratic delay in al-Batuf. It occurs both in neon-lit governmental offices where zoning programs and irrigation reservoirs are discussed in unending meetings as well as in the abandonment of the agricultural field. The timescape of bureaucratic delay is not only about making subjects wait. It is the prima facie of “the government is taking care of the situation” but in a timescale that would make any plan irrelevant by the time it is agreed upon. The bureaucratic delay encapsulates the how of the Israeli state machine: there is always some component to discuss in planning and implementation presumed to be more urgent than demonstrating to the Palestinian-Arab stakeholders that the Israeli government does something for them. The coming sections will analyze the forms of knowledge that inform the policy process and the timescapes they create: colonial-ecological time, ecological expertise time, and a traditional agriculture timescape.

GOVERNING THROUGH EPISTEMOLOGICAL TIMESCAPES

Governments construct public reason, or the forms of knowledge, institutional practices, discourses, and techniques that they use to justify their policies. Reasoning is situated within political cultures and modes of knowledge and expertise.Footnote 60

Two themes are reiterated in Israeli public discourse and in policy documents regarding the importance of the conservation around Beit Netofa: first, “it is the last swamp that was not drained”; second, a careful and integrative planning process is required based upon the lessons learned from the history of the nearby Huleh Swamp.Footnote 61 In the 1950s, Huleh Lake was drained by the Jewish National Fund to create agricultural terrains for the new kibbutzim established in the Upper Galilee. Huleh was reflooded in 1994 because it was understood that the Huleh drainage project bore heavy ecological costs and the process was not agriculturally beneficial.Footnote 62 Huleh Swamp stands in Israel today as a communal lesson requiring the need for careful ecologically based decision making.Footnote 63 Therefore, the history of Huleh Swamp drainage justifies current planning procedures that are conceived as integrative and thoughtful.

However, while this one historic lesson influences policy, another historic factor is ignored. The vast swamp drainage projects that took place in Palestine/Israel during the 20th century were initiated by the Zionist movement mostly before the establishment of the state. Drainage, like other infrastructures, forms politics by creating coverage, connections, or disconnections of regions as well as material and economic constructions of differences.Footnote 64 Historically, drainage affected the transformation of the local landscape in Palestine/Israel technologically, ecologically, and perceptually by promoting Zionism as a modernized and progressive project, one that the British colonial government would support.Footnote 65 Drainage was understood as vital for eradicating malaria and creating agricultural land.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the Zionist movement saw enhancing the production capacities of agriculture in Palestine/Israel as crucial because this would enable it to demand higher Jewish immigration quotas from the British.Footnote 66 Drainage was vital for increasing agricultural productivity. The drainage project created dramatic changes in the land and significant loss of habitats. Drainage was a project of agricultural modernization in which the Palestinian peasants were not invited to take part.Footnote 67 Thus, underdevelopment, exclusion, and settler colonialism are the historical factors that led Beit Netofa Valley to be “the last swamp that was not drained,” as policy documents say, but these factors are never recognized by the state. As the work of Samer Alatout shows, this is a historical context in which water resources functioned to construct a Jewish identity, immigration, and Zionist settlement.Footnote 68 An epistemological arrangement of governing through timescape is thus enfolded in the official narratives constructed around the water regime of al-Batuf, serving the state apparatus.

Yet, the valley's agriculturalists, who did not enjoy the fruits of agricultural development in the past, are now being asked to fly the flag of conservation. Placing such expectations on the underdeveloped could be compared to asking developing nations to share equally in rich nations’ responsibility for climate change, something that is considered unjust on a global scale. Agriculturalists say that their newly requested role of promoting conservation “for birds and plants,” which they find ridiculous, is a contemporary form of governmental control. Munir Hamoudi, an agriculturalist from the al-Batuf area, said at the Israeli parliament:

They used to confront our demands with the police and the army. Today we are confronted with ecologists, planning committees, “Greens,” etc. . . . But we are talking here of human lives, almost a hundred thousand inhabitants . . . We could also do developed agriculture.Footnote 69

Hamoudi identifies an environmental agenda as a form of state surveillance. This was a claim that I heard from other interlocutors as well. Considering the history of loss of wetland habitats in Israel/Palestine due to Zionist developmentalism, rather than Palestinian peasants’ agriculture, Hamoudi's rejection of “Green” environmental agendas contains logic. The threats to native plants are a part of a settler-colonial legacy rather than the Palestinian agroecological legacy.Footnote 70 Colonial projects were always multispecies enterprises involving the settlement of plants as well as animals and people.Footnote 71

Evidently, many of the al-Batuf agriculturalists want to cultivate what is understood as developed and modernized agriculture while officials insist to them, in an uneven dialogue, that it is modern to conserve. Thus, Didi, the former NPA ecologist, told me: “The agriculturalist lived all his life in here [al-Batuf] and he does not understand how unique this is, he does not have a perspective of all the country to understand how beautiful this landscape is.” Didi thought it would be a mistake not to involve the agriculturalists in contemporary conservation through agroecology. He posited that it is the mission of our times to educate the agriculturalists about ecological conservation. He presumes that the agriculturalists of al-Batuf lack a timescape perspective. In contrary, Munir Hamoudi's words in the parliament indicate that agriculturalists are very clear on the timescape that is presented to them by the government versus the one they prefer, namely, developed agriculture.

This section indicates that the contemporary story of al-Batuf entails an ironic historic reversal whereby nowadays Palestinians want to drain the swamp and develop their agriculture, while the establishment wants to preserve the swamp and to conserve “traditional agriculture.” However, the contemporary governmental approach to the situation rarely addresses the historical inequality of colonial-ecological time.

THE TIMESCAPE OF ECOLOGICAL EXPERTISE

Let us consider the timescape of the rising expertise in Beit Netofa—ecology. Over the course of sixteen years, ecologists from the NPA have undertaken eight surveys and studies that mapped the flora and fauna of Beit Netofa Valley. They undertook these surveys with partners from the Society of the Protection of Nature, an NGO that is also regularly represented in the Northern District Planning Committee. They operate in a coalition that serves the rising power of environmental expertise in Israel. With every published survey, a growing body of knowledge and numbers is produced about rare species and species threatened with extinction at the site. The species are also presented in the Planning Committee Meetings. Thus, the lives of certain species are given a political-ontological status. Moreover, the ecologists have produced ecological knowledge as an inevitable factor and actor in the political process of planning in al-Batuf.Footnote 72 The threat of extinction is a powerful political-discursive tool. It recruits the future risk of species’ extinction as a technology of power and produces an ethical timescape of saving species, suggesting that if the state saved them from extinction, it would stand on a higher moral ground.

The agency of endangered species as a political technology has a timescape to it. The ecological production of entangled time and space in the valley is anchored in practices such as slowly walking, locating and identifying flora and fauna, and documenting them in charts that end up as GIS maps of flora and fauna. These GIS maps run on computers that quickly cross-reference any nongovernmental, governmental, or research institution that is interested in the preservation of these species. Thus, the timescape of the ecological knowledge gains speed over time. Conservationists say that the species survive (sustained over time) in the valley due to the work of the “traditional agriculturalists” and their small plots’ margins, meaning that preventing the development of industrial forms of agriculture in the valley is in fact an ecological objective.

The ecological-temporal conception that is produced is not only based on the time needed to gather all the data regarding endangered species, but it is also anchored in two earlier accounts repeatedly quoted in those ecological reports produced by the NPA. These accounts contribute to the ecological temporality construction of al-Batuf and to the creation of an image of the wetland as an inseparable characteristic of this place. The reports mention quotations from the 14th-century Arab geographer al-Dimashqi and the 12th-century Jewish philosopher Maimonides, both of whom referred to the character of the valley as holding floods. These accounts fortify the image of the flood as an ancient and pristine “nature” that must be conserved, therefore reinforcing the ethical-ontological timescape of conserving this landscape as a wetland.

Thus, in al-Batuf, like in other places, knowledge production induces power, silencing other forms of knowledge.Footnote 73 Recruiting ecological science's timescape and selective historical accounts to the process of politics not only makes policy partially informed but also creates an image of a sustained universality. Indeed, next to the ecological knowledge base there was no involvement of social scientists or knowledge that would consider socio-economic relations in Palestinian society, social-environmental knowledge, such as ethno-botany, or traditional ecological knowledge.Footnote 74

QUESTIONING TRADITIONAL AGRICULTURE

A powerful tool for reasoning with developed agriculture in Israel while referring to al-Batuf as an exceptional “traditional” case is linked with a colonial heritage of seeing the other as inhabiting another time.Footnote 75 Johannes Fabian's form of critique argues that power relations are structured when subjects are seen as nonmodern and noncoeval.Footnote 76 Thus, the state treats itself as Westernized and developed and ties its modernity and progressiveness to identifying the other as “traditional” and “authentic.”

The agricultural-environmental imaginary that al-Batuf evokes and the sort of timescape continuity the establishment is looking for are evident in a variety of texts written by the ecologists contracted by the Ministry of Agriculture during the 1990s and early 2000s. The following excerpt was written by one of these ecologists, Racheli Einav. Although it appeared in a popular journal rather than a policy document, it is indicative of the situation:

Beit Netofa is a closed valley in the lower Galilee. Whoever is there can disconnect and will not see the rest of the world. It is as if in the valley time stood still—there are swamps there and traditional rain-fed cultivars that are harvested with a sickle . . . It is a real swamp like in the time of the Zionist pioneers, like in the Bible, the last we have that was not yet drained.Footnote 77

The text reflects the deep orientalist imaginaryFootnote 78 towards al-Batuf embedded in the minds of officials, and points to the heritage values and continuity that they are looking to conserve: it is the image of the fellahin as a living museum symbolizing both early Zionism days and mostly the landscapes of the biblical past.Footnote 79 Beit Netofa, then, is a timescape of bringing the past to the present.

Furthermore, the term “traditional agriculture” that has been used to define the uniqueness of al-Batuf must be reconsidered. The next excerpt, from a conversation with a cultivator in al-Batuf named Muhammad, will help problematize this term. Muhammad and I sat together in al-Batuf on a sunny, early summer day in 2014. Muhammad said: “We are doing agriculture here like they did in the days of the Turks.” “What do you mean?” I asked him. Interestingly, right in front of us was a new model combine and tractor, machines associated with current agrarian practices. “I mean that agriculture here is what it used to be like—we sit here and pray for the rain; we don't have water for irrigation. This is what agriculture is like here,” he emphasized. Muhammad is a Palestinian citizen of Israel, a state with a centralized water system that is known globally for its agricultural innovations in irrigation technologies, but he needs to wait for the rain. While the state describes the agricultural condition in al-Batuf as a fruit of tradition,Footnote 80 Muhammad's emphasis on where one prays for rain acknowledges uneven water policies, highlighting the relation between the identity of landowners and their allotted water resources.

During my time in the valley, the agriculturalists used various kinds of new agricultural machinery. They applied pesticides and were well acquainted with contemporary agricultural techniques. They also farmed in small plots, which are associated with traditional agriculture. Meanwhile, organic agriculture in Israel is likewise undertaken in small plots but never termed traditional. Furthermore, even the reports by the Ministry of Agriculture's contracted experts lightly criticize usage of the term “traditional agriculture” to describe Palestinian-Arab agriculture.Footnote 81 Nonetheless, policy-wise, the formal term continues to be “traditional agriculture.”

Constructing the Palestinian as “traditional” enables a governmental approach that sees Palestinian underdevelopment through that “traditional” character of the agriculturalist, rather than the result of power relations.Footnote 82 This form of governmental discourse enables stagnation, duration of long processes, and lack of state intervention, because it supposes that “the other” is traditional and will not accept change. The ways in which the agriculturalists organized in associations in the 1990s to advance the drainage program might imply that this is simply untrue.

CONCLUSION

The case of al-Batuf offers an ironic vignette of the Zionist history of agricultural development, particularly Zionist narratives of the Palestinian peasant. It is a story of the paradigmatic shift from modernist development endeavors to the politics of sustainability. The current timescape of sustainable development in al-Batuf is framed as a project that conserves ecological values but, in reality, preserves the political construct of a de-developed “traditional agriculture.” The Beit Netofa timescape is perceived by governmental agents as a Western notion of sustainable development, a model of development that the Palestinians should abide by in order to prove their environmental citizenship. This citizenship mode expects citizens to act for the common environmental good.Footnote 83 Thus, environmental state bodies expect the Palestinians to devote their land in the valley to environmental conservation. Yet the Palestinians’ lived experience of the environment is of land and water dispossession, as well as economic marginalization, and these experiences are overlooked by the state. As a result, in the new sustainable policy program, only the Israeli state's political domination is preserved.

The Israeli officials’ sudden appreciation of the Palestinian cultivator seems to be a discursive shift but not a comprehensive one. After all, Palestinian-Arab citizens and their environment are still viewed through the biblical imaginaries and orientalist approaches that have prevailed for more than a century. When Palestinian-Arab agriculturalists ask for agricultural development, they are looked upon as outside time, agents of past ideals of landscape and agriculture. Thus, this agro-environmental imaginary of the people and their land transgresses space-time; it reproduces and extends, lingering in policies from one regime to another and maintaining its hold over institutional modes of governing. In this way, al-Batuf echoes Diana Davis's critique of lingering environmental imaginaries of the Middle East, such as the case of desertification as an international problem under UNESCO.Footnote 84 Still, I show that the timescape not only preserves a particular imaginary of the land, but also encompasses the bureaucratic times and procedures that sustain these perceptions.

Controlling time and constructing space are tools of agency. In al-Batuf, various actors are engaged in making time and space but, ultimately, it is the state's governing timescape that dominates the political dynamics. The Foucauldian notion of governmentality (in its general sense) highlights the disparate logics, strategies, plans, and practices of discipline through which domination occurs. In this paper, I sought to unravel the interwoven work of time and space as a central component of dominating a population and its environment. The ethnographic attention to the small moments that make up a bureaucracy's manipulation of time highlights that waiting as a tool of domination encompasses much more than waiting in neon-lit rooms. It also extends to the mundane ways in which bureaucrats manipulate time by delaying decision making and prioritizing certain ecological datasets over other forms of social data that are rarely collected. Thus, I suggest that a timescape frame enables us to better recognize the previously hidden layers of domination involved in the governing process. Finally, imagining a new timescape for al-Batuf requires us to push the limits of its current zoning plan and its current planning timeframes.Footnote 85 By viewing al-Batuf's planning dilemma through spatio-temporal lenses, we are more informed about this landscape's historical and present conditions. However, questions regarding its future conditions remain.