Modern carcerality in Iran, with its attendant systems of surveillance, policing, and mass imprisonment, was a gendered project from the outset. In turn, the new modern prisons of the Pahlavi era (1925–79) provoked gendered anxieties about seemingly rising rates of female and child criminality, the deteriorating family unit, and the inherent sin and vice of life in a modern city. In general, it is difficult to overstate the wholesale changes that the modern carceral system has brought to Iran. The establishment of modern prisons, an effort begun in the first decades of the 20th century, has led to an enduring transformation in social worlds for Iranians of all genders. For much of Iran's pre-20th-century history, forced confinement of any kind was a relative rarity, legal practices and norms were diffuse and diverse, and long periods of incarceration were virtually nonexistent.Footnote 1 The conceit of prisoner reform central to the modern penitentiary model—wherein centralized modern governments imagine prisons as rehabilitative spaces in which socially undesirable “criminals” can be reformed into good “citizens”— is nowhere found in the archive of Iran's pre-20th-century punishments.Footnote 2

Before the 20th century, there were no dedicated jailing facilities for women in what was then Qajar Persia, and women were never jailed, even for short periods of time. When someone did happen to find himself jailed in this era, it was for very short periods while awaiting specific corporal or monetary penalties.Footnote 3 English colonial officer and travel writer George Curzon noted the transitory nature of jailing in the late Qajar era, writing in his famous 1892 volumes on Persia, “Imprisonment for some or several years and long detention is unprecedented. Prisons are usually evacuated at the beginning of each year, and whenever a new ruler initiates office, he often empties the prisons filled by his predecessor.”Footnote 4 To put it plainly, the types and lengths of detention handed out in modern and contemporary Iran, along with the notions of criminality and reform inexorably linked to the modern carceral model, would have been unfathomable in earlier periods. According to Iranian police sources at the end of the 1920s, prisoners in Tehran numbered only a few hundred.Footnote 5 Since then, the number of people incarcerated in Iran has increased exponentially until the present day, in which there are at least a quarter million people, including at least nine to ten thousand women, detained in the Islamic Republic's 268 official jails and prisons.Footnote 6

A brief look at Qajar-era (1789–1925) punishments for women, particularly those most prevalent before the Constitutional Revolution (1905–11), is necessary to put the dislocations of the past century in further context. Women convicted of various forms of wrongdoing and social transgression before the 20th century, like their male counterparts, were largely subjected to a variety of corporal or monetary penalties. In minor cases, bribing local authorities for more lenient outcomes was typical. As one European missionary noted in 1895, “Wine-sellers, thieves, and lewd men and women are levied upon for hush-money, a la Tammany [Hall, in New York].”Footnote 7 Capital punishments for women, although exceptionally rare, did occur. Although most capital punishments for male wrongdoers of the era were done via hanging or throat slitting, women often faced other methods, especially forced poisoning and strangulation.Footnote 8 As one female traveler of the era notes, “No women are ever imprisoned, although if mixed up in a crime they will probably be poisoned, but . . . such cases are of the rarest.”Footnote 9 Other European sources attest to the inventiveness with which the very few women punished by death were executed, although it is likely that many of these sources relied on rumor rather than firsthand knowledge. One traveler, for instance, noted that “in the few capital punishments of women,” the offending party was “usually strangled, or wrapped up in a carpet and jumped upon, flung from a precipice or down a well.”Footnote 10 Perhaps the most prominent woman to be executed in 19th-century Persia was the revolutionary women's activist, poet, and Babi firebrand Fatemeh Zarrin-Taj Baraghani, also known as Tahereh Qurrat al-ʿAyn, who was punished for her transgressive political and theological views by being strangled to death and thrown into a well in 1852.Footnote 11

The first modern prison facilities in Iran were established in the final years of Qajar rule under the direction of Swedish police officers led by reserve lieutenant Gunnar Westdahl, who was brought to Iran in 1912 to reform Tehran's then-modest police force. In their decade in Iran, the Swedish officers initiated several policing reforms and oversaw the building of a nascent carceral network in central Tehran's Tupkhaneh Square, a location that had until recently been used for public whippings and executions. Included in this network were a small interrogation center, a temporary holding facility, the central police jail, and the first dedicated women's jailing facility in Iran. This facility would remain the main women's prison well into the Pahlavi period, although women would begin to be held in police jails in other big cities such as Isfahan during this era as well.Footnote 12

The Reza Shah Pahlavi period (1925–41) is particularly consequential in the founding and entrenching of the modern carceral state in Iran. It was during Reza Shah's reign that the Iranian government embarked on the wholesale codification and centralization of Iran's legal system. It also was during this time that the government invested in a substantial modern prison system, taking long-standing Iranian reformist anxieties regarding law and order as well as European legal and penal models as sources of action and inspiration.Footnote 13 The centralization of modern Iran's legal system was undertaken by the newly crowned Reza Shah, who in 1927 appointed the University of Geneva–educated politician ʿAli Akbar Davar to reform the central judiciary, which had first been established during the Constitutional era. Two days after his appointment, Davar dissolved the existing judiciary and undertook the overhaul of the piecemeal 1911–12 organic, civil, commercial, and criminal codes, which had themselves been efforts to standardize Qajar Persia's decentralized systems of legality.Footnote 14 The expansive reforms of the Davar period, largely undertaken from 1927 to 1931, irrevocably changed the political, legal, and social landscape by codifying law, reducing the power of the shariʿa courts, and establishing a standardized judiciary that borrowed liberally from European legal norms while maintaining some connection to customary and clerical legal structures and personnel. Crucially, the nascent legal institutions of the centralizing state were increasingly invested in—and increasingly capable of—policing the boundaries of appropriate public behavior, based on gendered notions of normative citizenship.Footnote 15

Those small jailing facilities built in Tehran in years prior were not enough to meet the swelling demand for prison space brought about by a post-Davar legal order. Accordingly, the Pahlavi government planned to build tens of new prisons, in part to address this need for space and in part to show to the global powers that Iranian systems of law and punishment had been standardized.Footnote 16 The most important of these new facilities was Tehran's Qasr prison, which opened its doors in December 1929 with the initial capacity of holding several hundred prisoners. A separate women's ward was planned for the near future and would be fully operational with factory and educational facilities by the 1950s.Footnote 17

These newly built prisons were promoted by the Pahlavi elite as modern solutions to social problems and a necessary step in transforming Iran from a “lawless” traditional society to a “civilized” modern nation–state capable of taking its rightful and sovereign place on the global stage. Members of the Pahlavi elite claimed that this “progressive” institution, designed and built with input from criminologists and law enforcement specialists from around the world, could reform criminals into productive citizens and could even end the social disease of crime altogether.Footnote 18 Yet, despite these early hopes, these new prisons would quickly become objects of criticism, as these spaces seemed almost immediately to reveal the pitfalls of Pahlavi penal modernization rather than its successes.

Public awareness of women and children held at these new carceral facilities would particularly elicit anxiety among the emerging middle classes in mid-century Iran about the apparent rise in female criminality and the breakdown of the Iranian family, despite the still relatively small number of female prisoners in this period. In 1946, a Tehran-based publisher released Come with Me to Prison (Ba Man bih Zindan Biyaid) by Hedayatollah Hakim-Elahi, an Oxford-educated journalist, Islamic humanist, and chronicler of the seedy underbelly of life in Tehran.Footnote 19 The book compiled Hakim-Elahi's serialized newspaper writing and was one of several similar titles, including Come with Me to the Red Light District, Come with Me to the Asylum, and Come with Me to School. Come with Me to Prison gestures to the budding sentiment among mid-century intellectuals that to live in Tehran, lined with prisons, mental institutions, and brothels, was to live among ever-growing throngs of people as well as ever-budding criminality and vice. This view would be further championed by later intellectuals such as Qadisih Hijazi, a female critic who wrote the first monograph-length work on what was now being called “female criminality,” and who, as historian Cyrus Schayegh has noted, viewed female criminality in Iran “as a result of accelerating urbanization, migration, changing patterns of work, and the rise of mass urban culture.”Footnote 20 Tehran was the bustling capital of the modern nation, to be sure, but in these texts it also was the nation's dangerous capital of loose women, vice-seeking men, and potential social degradation.

Echoing the moralist bent of his quasi-ethnographic work on Tehran's red-light district, Hakim-Elahi decried conditions at the Tehran women's prison, including the fact that many of the women held there had young children in tow or youngsters left behind without motherly supervision at home. Hakim-Elahi especially lamented the legal limbo in which detainees were held without having been arraigned, sentenced, or in some cases told of the state's exact charges against them. The author claimed that of the fifty-seven women being held in the women's prison upon his visit, only five had already been sentenced; most of the women had been waiting to be sentenced on theft or prostitution charges, and many insisted on their innocence.Footnote 21 Whereas other sources noted the kitchen and small dining area in the prison, Hakim-Elahi wrote of the facility, “Filth and misery covered the prisoners from head to toe.” The journalist continued, “Everyone complained about their uncertain sentences. They would say, ‘If they tell us that we have to be in prison for ten years, it would be better than this uncertainty [bilā taklīfī].’”Footnote 22 What was worse, these wretched women were exposing their innocent children to the deleterious atmosphere of prison. According to Hakim-Elahi, the conditions at Tehran's juvenile prison Dar al-Taʾdib were equally grim. Hakim-Elahi claimed that in Dar al-Taʾdib, young boys were often subjected to bachih-bazī, that is, sexual relations between older men and young boys. The author asserted, with little by way of corroboration, that young boys were kidnapped on the streets of Tehran and brought to powerful imprisoned gangsters for their sexual pleasure. Children as young as eight were picked up and shuttled to prison, the author insisted, their only crime their attractive “rose-colored cheeks.”Footnote 23 Again, Tehran itself was implicated in the corruption of Iranian youths.

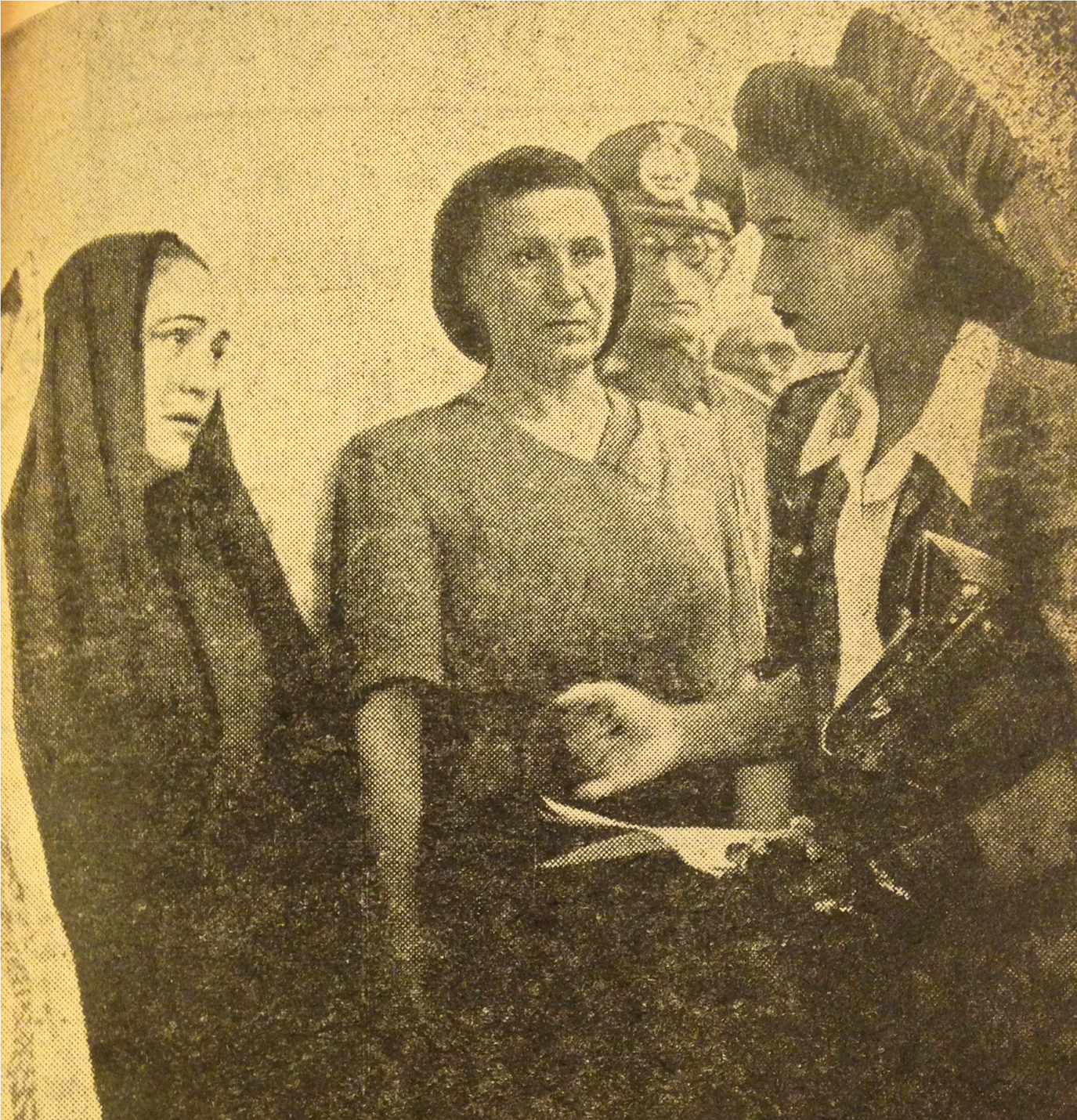

Hakim-Elahi was skeptical of official efforts to improve conditions at the women's prison, including those made by arguably the most powerful woman in Pahlavi Iran, Princess Ashraf Pahlavi, Mohammad Reza Shah's twin sister. In September 1946 Princess Ashraf, who in later years took up elite women's issues in part through her work with the United Nations, visited the women's prison and met with both officials and detainees (Fig. 1).Footnote 24 Hakim-Elahi asserts that prison officials simply gave the typically filthy and degraded jailed women new chādurs (chadors/veils), and that Ashraf was satisfied by these surface efforts. Other more sympathetic press of the day also reported on the princess's visit to the prison, including one article in the popular news magazine Khandaniha (Readables), a long-running Reader's Digest–like journal that reprinted noteworthy news from other sources alongside its own reports.Footnote 25 The Khandaniha report put the official number of detainees in the women's prison at the time of Ashraf's visit at sixty, close to Hakim-Elahi's claimed total of fifty-seven, and painted a relatively benevolent picture of the princess providing comfort and compassion to suffering female detainees and their children. The report claimed that of the women being held, eleven were incarcerated on the charge of murder, ten were incarcerated on the charge of “actions inconsistent with chastity,” twenty-four on charges related to theft, and the final fifteen on fraud. Yet even this sympathetic article admitted that of these women at least fifty were still waiting to know if and when they would be sentenced. Upon leaving, Ashraf is reported to have taken the names of the incarcerated children, in whom she took charitable interest as innocent parties, to introduce them to relevant educational institutions.Footnote 26 In Hakim-Elahi's view, little meaningful change would come of such half-hearted efforts.Footnote 27

Figure 1. Princess Ashraf on a visit to the women's prison, September 1964. Hedayatollah Hakim-Elahi, Ba Man Bih Zindan Biyayid (Tehran: Shirkat-i Sihami, 1946), 142.

Documentary filmmaker Kamran Shirdel painted a comparably dark picture of Tehran's women's prison in his short 1965 film Women's Penitentiary (Nedamatgah).Footnote 28 Shirdel's 1960s films depict life in Tehran—particularly its prisons, poverty, and sex industry—in gritty, moralistic detail, not unlike Hakim-Elahi's quasi-ethnographic texts. Like Hakim-Elahi, Shirdel depicted the women's prison, as well as Tehran's red-light district about which he also would make a short documentary, as a site of abjection and victimhood for Iranian women. Women's Penitentiary includes footage of imprisoned women raising their young children behind bars and worrying about their families beyond the prison walls. The film further includes interviews with both detainees and social workers, one of whom argues that having mothers in prison leads to “psychological and emotional problems” for their children. In their emphasis on broken families, damaged children, and the dangers of Tehran, critiques such as those of Hakim-Elahi and Shirdel offered damning appraisals of the Pahlavi government, in part because they challenged the state using a long-standing discourse of Iranian nationalism: patriotic motherhood.Footnote 29 As Firoozeh Kashani-Sabet has noted, the discourse of patriotic motherhood linked the intimate practice of raising children to the public health of the nation; patriotic mothers were women “committed to the family who also identified with the ideals of the nation.”Footnote 30 Yet instead of raising the next generation of healthy patriots as the nation's citizen-mothers, these critiques indicated, Iranian women were raising the next generation of criminals and recidivists.

The concepts of female and child criminality, particularly the idea that Iranian children were learning to engage in crime rather than being educated at school or by citizen-mothers, were a direct challenge for the modernizing Pahlavi government. Pahlavi state institutions argued that child criminality was a failing of absentee parents, who through negligence let their children be corrupted by sinister forces. A 1960s radio program broadcast by the national police, for instance, interviewed a twelve-year-old pickpocket who explained that he had been abandoned by his father and left unattended by his mother, leaving him to learn the art of delinquency from street thieves.Footnote 31 Even in these official discourses, Tehran was implicated as a source of potential corruption. Come with Me to Prison ironically noted that Qasr was a “giant school of ethics” in which one must learn a “strange science”: the science of criminal behavior.Footnote 32 Yet despite this damning appraisal, Hakim-Elahi believed in the reformist promise of Iran's new modern prisons. Rather than argue that the prisons he so forcefully critiqued be emptied, Hakim-Elahi instead demanded the further expansion of Iran's carceral networks. The journalist argued for the development of Iran's prison factories in particular, which he believed could rehabilitate wayward Iranians. It was precisely this expanded carceral project, with attendant notions of gendered labor and behavior, that the Pahlavi state would take up in coming years.

On 9 October 1954, a little over a year after a CIA-led coup restored Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to the throne, the Iranian cabinet approved the bylaws for the Institute for the Cooperation and Industry of Prisoners (ICIP; Bungah-i Taʿavun va Sanaʿiʾ-i Zindanian), a state-run organization mandated with developing prison factories and education facilities and supporting the families of the incarcerated.Footnote 33 With financial backing from another state institution, the Organization for the Protection of Prisoners (OPP; Anjoman-i Hemayat-i Zindanian), the ICIP dramatically expanded Iran's prison labor and education program in the coming years. In 1959, the Pahlavi government (through the OPP) gave machines, tools, and capital in excess of 285,000 rials to the ICIP to put toward this end. The institute established new factories in both the men's and women's prisons in Qasr, with workstations for sewing, metal works, automobile repair, furniture building, shoemaking, purse-making, embroidery, basket weaving, belt-making, straw mat–making, rug-making, sock knitting, frame building, hair and makeup, handicrafts, and fine arts.Footnote 34 Skills classes and factory work were delineated across gendered lines. By 1965 there were at least thirty skilled experts and technicians in the Qasr prison factory who taught skills classes and worked in a management capacity. There also were an estimated 850 male, 95 female, and 45 youth incarcerated workers in prison work programs across Iran.Footnote 35

The ICIP credited its founding to Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who they claimed had reformed Iranian prisons along “civilized” and “scientific” principles, and whose prisons were championed as working toward the eradication of the social disease of criminality.Footnote 36 A 1965 speech given at the eighth general conference of the OPP by then national Chief of Police Major General Mohsen Mobassar, highlighted the “humanitarian efforts” of those working to improve the lives of prisoners in Iran.Footnote 37 Instead of merely punishing for the sake of punishing, Mobassar told members of the organization, civilized and progressive modern nations including Pahlavi Iran now meted out punishment scientifically, humanely, and most importantly, effectively. After the founding of the institute, Pahlavi law enforcement officials increasingly championed the therapeutic and restorative capacity of Pahlavi prisons, touting them as the antidote to the social contagion of criminality. In a speech given in 1968, for instance, Mobassar argued for the necessity of viewing crime as a social disease that could ultimately be cured:

The prison system has totally been transformed, such that today the prison is no longer a place meant for the negation of freedom. Instead, the prison is a treatment center in which criminals and lawbreakers are taken into a space . . . after which the social illness with which they enter is cured.Footnote 38

The primary means through which Iranian prisons could turn social disorder into social productivity, according to Pahlavi officials, was labor. Indeed, prison labor was touted as being capable of restoring a prisoner's health, honor, social standing, and moral compass.

Prison labor was imagined in gendered terms, with the division of labor for men and women strictly defined. Male prisoners were put to work in factories or on farms, whereas women were taught sewing and embroidery. The ICIP saw sewing, cooking, and home management as integral to its mandate for female prisoners, because women needed to be prepared for their future lives as virtuous homemakers and mothers. In other words, socially deviant women, now coded as female criminals who had to be transformed into patriotic mothers, had to be trained to live their lives as normative citizen-mothers and citizen-wives. Pahlavi prison reformism was a project of the embodied production of normatively gendered citizens. For men, this was a training in “honest” labor, which would free them from the shackles of degeneracy and vice. For women, this was a matter of restoring honor, and a means to live a new life as a productive wife, mother, and citizen.