A man was stopped at a checkpoint.Footnote 1 The men at the checkpoint asked him, “Who are the pansies, the terrorists or the police?” He said to them, “I'm the faggot who came this way.”

Wāḥed ḥbes fī barrage saqsāwah “shkūn al-aʿṭāīn, les terros welā la police?” Qālhum “ānā al-naqsh elī jizt minā.” Footnote 2

Jokes and caricatures from Algeria's Dark Decade, a period of conflict that ravaged many areas in the North African nation from 1991 until approximately 2002, created parallel universes in which even the most ordinary of citizens could reconstruct the social and political realities in which they found themselves. Occasionally cartoonists and joke tellers used their crafts, the most popular forms of humor from those years still accessible to scholars, to portray the major tormentors and perpetrators of the violence (the armed insurgents and the state) as buffoons completely bereft of power. For the most part, however, humor from this critical period of Algeria's postindependence history, recognized by local actors and scholars as its nadir, tended to make fun of civilians, like the man who ends up at the checkpoint above.

Yet popular comedy from this era of Algeria's history not only exposed the supposed weaknesses of the population, but generally did so in ways that emphasized how the war was undercutting the “masculinity,” or rujūla, of Algerian men, observes Abderrahmane Moussaoui.Footnote 3 The joke here echoes this pattern. Anyone familiar with what residents of the nation have sometimes coined the “time of terrorism” would know that a wrong answer on the part of the ensnared man could entail a lamentable fate. He refuses to answer the question from the men at the checkpoint, either agents of the state or of the rebel self-proclaimed Islamist organizations that were working to upend it. If he said that the terrorists (read: insurgents) were homosexual, he placed his allegiance squarely on the side of the state, and vice versa. Instead, he lowers himself by local standards, calling himself a homophobic slur, naqsh, for a man who is penetrated during sex, an act that purportedly diminishes a man's rujūla.

Scholars of Middle East masculinity studies such as Paul Amar and Marcia Inhorn have argued for studies of men and male behavior and identity in the region that avoid reproducing stereotypes that link masculinity to anger and employ violence as a catch-all explanation for their actions. Amar and Inhorn have pushed for more work regarding the globally informed, varied, and creative ways that men across the region continuously delineate and perform masculinities.Footnote 4 This work adds to and breaks theoretical ground in Middle Eastern and North African gender studies by asserting that, in the context of Algeria's Dark Decade, comedy reinforced preexisting gender norms and offered a forum for expressing ideas and possibly lessening anxieties surrounding the violence and its “emasculating” impact on men. At the same time, men might have used jokes and cartoons to make up for lost masculinity by speaking out about the violence in a “manly” fashion. This article highlights the potential of political comedy as a medium of gender construction, an innovative contribution to Middle Eastern and North African studies.Footnote 5 The recognition of humor's role as a site for crafting manliness constitutes a step toward teasing out ways of being masculine in a region that, in the words of Frances Hasso, “systems of dominance” have “made discursively illegible.”Footnote 6 In this case, such systems include media outlets covering Dark Decade events as well as scholars viewing Algerian men's elaboration of masculinity through the lens of violence at the expense of more pacifist, creative endeavors.

I also attempt to move scholarly deliberation on Algerian masculinities away from nationalist or colonial paradigms or actors engaged in direct confrontation with the Algerian state. My focus lies rather on the emotionally laden humorous rhetoric that members of the pacifist civilian majority used to process how the Dark Decade was altering Algerian society as well as themselves. This work further analyzes silences imposed upon men rather than male-supported initiatives to keep women relegated to certain spheres, the focus of most previous literature on gender in Algeria. Instead, I parse out other types of masculinities, beyond those connected to violence (including that of a sexual nature) and the oppression of women in an Algerian context. Indeed, most writing on Algerian men during the Dark Decade and events leading up to it, such as the October 1988 riots, has concentrated on men turning to violence or wealth accumulation as ways of pushing back against perceived emasculating situations such as the economic crisis of the late 1980s, state violence, and a general sense of dispossession.Footnote 7 The present piece will highlight how, amid the armed struggle, tools beyond violence or hustling existed that men could draw upon to respond to perceived threats to their ability to express locally accepted forms of masculinity. Finally, I avoid conceptualizing the war in terms of its belligerents and choose to focus on how the crisis influenced the country's pacific civilian majority. I indicate the significance of at least some Algerian men's peaceful responses to the emasculating political circumstances of the Dark Decade as well as the importance of humor, a major space for acknowledging and playing with taboos related to sex and gender, as a source for critical gender scholarship on the region.

Jacob Mundy, Mani Sharpe, and Andrea Khalil have explored masculinity during the Dark Decade through the prism of films such as Bab El-Oued City. Their work suggests a plurality of masculinity in Algeria at the time and attempts to undercut myths surrounding rujūla in this context.Footnote 8 During the conflict, Algerian literary authors such as Assia Djebar and Yasmina Khadra (female pen name of Mohammed Moulessehoul) represented the war's many gendered aspects in their work.Footnote 9 I turn my analytical lens upon a more popular form of cultural expression that was widespread, communally created and consumed, and broadly available to Algerians across socioeconomic groups in the 1990s—political humor. Humor offers a more ambiguous but accessible source that can be used by scholars to uncover the effects of this period on the subjectivities of nonviolent male civilians, whose stories of the Dark Decade have been overshadowed by accounts of the armed groups, the state, and their respective motives.Footnote 10 Anthropologist Abderrahmane Moussaoui has noted that jokes from this era tended to ridicule men as weak, impotent, and effeminate. Moussaoui concludes that these humorous anecdotes functioned very much in the ways that I suggest. However, I want to push Moussaoui's work a step further to propose that these jokes may have indicated a disruption in masculinity that arose from the circumstances of the armed struggle and then also link this function of jokes to the country's broader comedic landscape by showing that caricatures worked in the same way to demonstrate a reversal of gender expectations.Footnote 11

I collected the majority of the orally transmitted jokes presented here in interviews with journalists, cartoonists, and comedians in Algiers and from publications such as Blagues Made in Algéria (sic) by Algerian cartoonist Lounis Dahmani.Footnote 12 Many of the narrators I spoke to were male intellectuals during the war. I was unable to gain a more representative example of the Algerian population due to persistent political sensitives surrounding the Dark Decade in Algeria. Dalila Morsly has examined feminine humor, and certain jokes such as those collected and represented in cartoon format by Dahmani seem to reflect humor for and by women during this time.Footnote 13 My collection of oral history testimonies was limited to those of public figures and journalists, who were overwhelmingly male. As a result, the jokes that I evaluated may be more representative of anecdotes told and retold by Algiers-dwelling men who were engaged in cultural production.Footnote 14 The caricatures examined below hail from the country's most widely read newspapers, which followed different circuits of production and distribution. They appeared in towns and cities across the country, with the exception of the spaces that the armed groups controlled (where they suppressed the distribution of newspapers that they deemed too “pro-regime”). By referring to this body of comedic material—whether orally transmitted joke or caricature—as “Algerian,” I do not mean to give greater weight to the national at the expense of local (Algérois or Oranais, for instance), ethnic (Tamazight, Chaoui, etc.), regional, transnational, or any other identity. The very political intrigues and actors of the Dark Decade, however, were linked to aspirations for power on a national level. What is more, Algerians themselves (such as Dahmani) have labeled this comedy as “Algerian” or “from Algeria.”Footnote 15 Finally, humor by its nature is ambiguous and open to multiple readings and understandings. The broader historical context in which audiences consumed jokes and caricatures helps to elucidate how they would have been understood in the era. I also focus here on civilian narratives involving disruptions of masculine practices, although it is possible that these jokes and even caricatures were retold by military and rebel partisans; the lines between these categories proved far from stable in the midst of the war.

GENDER AND ALGERIA'S DARK DECADE

The circumstances surrounding Algeria's civil conflict of the 1990s undermined commonly accepted norms surrounding masculinity, or rujūla, so much so that noted scholar of Francophone literatures Mourad Yelles has viewed the arguable start date of the conflict, the October 1988 riots, as a “symbolic turning point” in Algerian masculinities.Footnote 16 Notions of “correct” masculinity in Algeria by this time revolved around three core ideas: (a) men's capacity to protect women and homes, (b) a willingness to go into public spaces or outside to challenge potential invaders, and (c) strict interest in having only heterosexual relations.Footnote 17 Violence against women marked the Dark Decade, exposing a breakdown in Algerian men's ability to ensure the safety of women. Women feared attack if they failed to behave in manners deemed inappropriate by insurgents. There were numerous examples of women being killed for not wearing a veil, as prescribed by the armed rebel groups. Conversely, there also were limited cases of women and girls being assassinated by still unknown actors for veiling. Insurgent groups wielded rape as a weapon of war and intimidation against women. From 2,000 to 8,000 women were estimated to have been kidnapped, raped, or killed over the course of the conflict.Footnote 18 By the late 1990s, although the subject was still very much taboo, media outlets within Algeria as well as the state itself attempted to tackle the issue of women who had been raped and at times ostracized by their families and communities. Many outspoken feminists and women's rights activists also received anonymous death threats and either went into hiding or fled the country as a result of these terrifying menaces.

Conversely, some women supported Islamist parties and assisted the armed groups in their mission to overthrow the government.Footnote 19 Bill Lawrence identifies feminist Islamism as one of the six major discourses that Algerian youth forged during the period of the late 1980s through the 1990s.Footnote 20 Michael Willis also estimates that one in four Islamic Salvation Front (FIS, a major Islamist party) supporters were women.Footnote 21

An overview of humor and the circumstances of the Dark Decade demonstrates that the enduring violence may have challenged men's sense of rujūla. John Phillips and Martin Evans recognized rujūla as being so strong that they designated this pride and need to stand up to corrupt authorities, fueled by the “anger of the dispossessed,” as the driving force behind a number of men's political actions in the 1980s and 1990s. These actions included rallying around the FIS and taking out their anger about religious transgressions on women.Footnote 22 Despite the occasional presence of women in Islamist movements and the armed groups, the majority of partisans in the FIS and armed groups were men. Protestors at various events throughout the late 1980s, including the October 1988 riots, and the conflict of the 1990s often called leaders effeminate and themselves “men” to counter their treatment at the hands of the state. These taunts illustrated the importance of perceived rujūla in local political worldviews.Footnote 23 Cartoonists even honed puns from the similarities between the Islamist party's acronym (FIS) and the French word for son, a sign that the movement gendered itself male from the very beginning, in 1991, despite insisting that women had a role to play as well.Footnote 24

By creating imagined connections between their militants and the National Liberation Front (known by the French acronym FLN) soldiers who defeated France in 1962, FIS leaders aligned themselves with the paragons of Algerian standards of masculinity in the postindependence era—the mujahidin. Several Algerian writers born in the wake of Algeria's successful revolt against French occupation have noted a malaise that they felt growing up in the shadows of the Liberation War. Many feared that they could not live up to this acutely masculine mujahidin generation.Footnote 25 Moreover, as James McDougall has rightly outlined, in the 1970s intellectual figures of varying ideological and political stances commented on the purported decline of masculinity and manliness among young men, those who had been too young to fight in the nationalist uprising.Footnote 26 Concerns about how political circumstances were impacting masculinities in the country persisted throughout the postindependence era. The economic crisis after 1984 marked an especially trying time for young men who struggled to start families while watching a kleptocratic elite live lavishly off the state's coffers. In this sense, the 1990s, during which economic problems persisted, marked a continuity rather than a rupture with earlier patterns of unfulfilled gender expectations.Footnote 27

The state produced and reproduced this veneration of the mujahidin in a number of cultural spheres. Comedy was one such field. From the 1960s to the 1980s, the country's state-supported bandes dessinées industry, including artists like Mustapha Tenani, lionized the mujahidin through lustrous albums. This artwork depicted the War of Independence fighters in action, typically in the imagined and oft-mythicized maquis, performing heroic feats of bravery while protecting their communities against villainous French soldiers. These figures often died accomplishing these tasks, transforming them into shuhadāʾ, or martyrs. As Rahal has noted, the postindependence state has privileged weapons-bearing soldiers of the National Liberation Army and typically eschewed focus on individual fighters.Footnote 28 Algerian humorists acknowledged and played with what Rahal referred to as the hagiography of the shahīd, those nationalist fighters who died in the liberation struggle.Footnote 29 Algerian comedy makers had thus been using humor as a discursive field for reflecting on, reinforcing, or shaping masculine ideals for decades prior to armed struggle of the 1990s.Footnote 30

The mujahidin and shuhadāʾ perfectly encapsulated the underlying attributes generally associated in Algeria with rujūla even prior to the war, but long afterward as well. Toughness and a capacity to protect oneself and one's family and limit intrusions by outsiders into the family space were the markers of this masculinity. In the earlier War of Independence, researcher of French and FLN policies toward women Neil MacMaster discovered that Algerian men suffered from the knowledge that they were losing the war against the French militarily. Theorist, psychiatrist, and member of the FLN himself, Frantz Fanon recognized a similar anxiety and dislocation of gender roles as a result of French police and military repression during the armed struggle, namely the rape of women. MacMaster's archival findings and Fanon's observations evinced how notions of masculinity and admirable “manly” behavior were entrenched in the ability of men to protect women and defend their communities.Footnote 31 Furthermore, a connection of the outside with manliness is reflected in the organization of gendered social spaces that Schade-Poulsen discovered in Oran in the late 1980s and early 1990s, despite women occupying public spaces.Footnote 32

For men, particularly young men, the conflict of the 1990s ushered in a period during which they could not keep insurgents or state agents from entering even the most intimate spaces of their family lives and homes. In his ethnographic study of the Dark Decade, Moussaoui describes male heads of households determining their political alliances and actions based on whether these maneuvers would help to protect female family members. He specifically discusses a case in Beni-Saf in western Algeria. A man joined a neighborhood militia group because he feared insurgents could assault his daughters in his own home. According to Moussaoui, the man stated, “How do you calmly sleep when you know that at any hour of the night your daughters can be raped in front of you?”Footnote 33

Beyond a failure to protect the home there was potential failure to protect oneself. There appears to have been a surge in the sexual abuse and rape of men directly resulting from the crisis that gripped the country from 1988 until the early 2000s. Official statistics on male sexual assault survivors from the armed struggle do not exist. Human rights lawyer Amine Sidhoum averred, however, that at least one man he knew who was rounded up by security forces between 1991 and the early 2000s claimed that he had been sexually violated during his detention.Footnote 34 There was a common rumor that the government possessed an animal that was used to anally rape men as an interrogation technique. This unsubstantiated accusation made its way most recently into journalist Adlène Meddi's novel about the conflict, 1994.Footnote 35 Survivors of the government's crackdown on protesters in October 1988 also claimed that state agents had subjected them to sexual abuse.Footnote 36

All in all, limited sources beyond humor suggest that at the height of terror in some parts of their country Algerian men were not just incapable of warding off attacks on their homes and family but also on their own bodies, potentially inciting tremendous anxiety. The next section will suggest that humor about the conflict could relieve some of this tension while also buttressing gender expectations and implying that the conflict was upending men's ability to fulfill them.

DARK DECADE JOKES AND CARICATURES THAT EMASCULATE CISGENDER MALE FIGURES

Numerous caricatures and jokes, two of the most popular forms of contemporary comedy in Algeria during the armed struggles, commented on the shifting nature of gender roles and masculinity in its wake. Of the seventy or so jokes that I collected relating to the Dark Decade, nineteen could be considered emasculating, in that they assigned “female” attributes such as cowardice to men or showed men being subjected to sexual assault or openly enjoying homosexual sex. Twelve of these jokes involved male characters being sexually assaulted or raped, a high proportion of the jokes overall, especially in light of the silence shrouding this issue in other contemporary source material. These numbers illustrate that humor opens doors to analyses constricted by more traditional archival source material.Footnote 37

This comedic work seems to have worked to alleviate men's apparent tension concerning their inability to exercise traditional masculinities due to the conflict. It likewise signaled to readers and listeners that previous gender norms entailing masculinity (power as well as an ability to protect both family and oneself) were still very much in play and expected. Students of humor have long posited that comedy often depends upon the unexpected to incite laughter and, in the process, release tension. Incongruity humor theory asserts that jokes often play upon norms that lead unsuspecting listeners to anticipate one outcome only to have themselves faced with another. The school of superiority theory believes that humor can function as a corrective tool or mechanism for shaming by mocking individuals who break with socially desired patterns of behavior.Footnote 38 In Dark Decade jokes and caricatures, joke tellers and cartoonists depicted scenes that took their audiences through unexpected twists related to how men and women should act, embodying aspects of both humiliation and social control, although it is impossible to know the degree to which creators intended these products to act in these ways. Humor from this period permitted listeners to refresh already standing models for male and female behavior in Algerian communities. It did so by calling attention to and further normalizing listeners’ or readers’ anticipated outcomes of stories concerning gender and sex in jokes and caricatures that upended norms.

Like so many other comedic products of this period, the following anecdote pokes fun at presumably cisgender men for losing control of their ability to assert their rujūla and protect themselves in the context of the conflict:

This is the story of a man from Mascara [a town in western Algeria] who was transporting olives in his truck and arrived at the top of a mountain, where he came across a fake checkpoint.

The terrorists decide to insert all of his olives into his anus.

After 15 minutes of this activity, the man from Mascara starts to laugh. The terrorists are surprised, and the chief of the group asks that he be stuffed with even more olives, but the man from Mascara doesn't stop laughing.

The chief, fed up with him, decides to find out the cause of his guffawing. The man explains, “I'm thinking about my friend, who is coming this way transporting melons.”

C'est l'histoire d'un maʿascariy (Arabic term for person from Mascara, sometimes written maʿascariy) qui transportait des olives dans son camion, arrivait à hauteur d'une montagne, et tombe sur un faux barrage.

Les terroristes décident de lui rentrer toutes ses olives par l'anus.

Après 15 minutes de passage à l'acte, le maʿascariy commence à rire. Les terroristes sont étonnés, et le chef demanda de lui rentrer encore plus. Le maʿascariy n'a toujours pas arrêté de rire.

Le chef a eu marre de lui, et il décide de savoir la cause de son fou rire. Le maʿascariy répond: “Je pense à mon ami, qui est en route et qui transporte des melons.” Footnote 39

Jokes about false checkpoints functioned as imaginative social experiments whereby joke tellers placed any subsection or group of Algerians (alcohol drinkers, young couples, Kabyles, horny older women, etc.) face to face with harbingers of doom. Insurgent organizations designed fake checkpoints to hold the general population in fear and awe, inflict punishment upon suspected government allies, and acquire wealth and sex from their unsuspecting victims. Rebels disguised themselves as state soldiers along highways where the latter usually stopped passengers to check for any signs that they were collaborating with the armed groups. Mundy labels the military's checkpoints sites of “masculine surveillance and control.”Footnote 40 In these circumstances, the men in control abused their power to rob other men of their capacity to express their rujūla.

In this fake checkpoint anecdote, the man from the oft-ridiculed Algerian town of Mascara finds himself confronted with wily insurgents who subject him to sexual abuse.Footnote 41 He is unable to overpower the men to prevent them from violating his body using, of all things, the source of his livelihood—his own olives. The unexpectedness and incongruity of the man's laughter as well as the surprise ending, when listeners discover that the man can revel in the horrendous impending fate of his friend, emphasize that the armed men keep both the olive farmer and his companion from effectively performing their rujūla by ensuring their own bodily defense. The ability of the man to laugh at a friend and someone who is about to suffer a similarly nasty experience further highlights how this type of sexual abuse, when directed at someone else, can provoke hearty laughter and schadenfreude.

This joke may also have alleviated tension around the rape and sexual abuse of men by acknowledging that any man who happened to come across a fake checkpoint—these were widespread in different parts of the country—could find his body mistreated in a similar fashion, even to the point of being comical. In the interviews that I conducted with seventy-two narrators who either survived the Dark Decade or worked in an academic, journalistic, or artistic capacity on the conflict, with two notable exceptions, I was unable to confirm that Algerian men were concerned about being raped or had been raped. Comedy potentially worked here as a tool to express a fear otherwise largely unspoken, a function of humor commonly identified by its students.Footnote 42

The man's complete subjugation to the will of the rebels shows that he is weak, according to the logic of then prevalent attitudes toward gender. What is more, there is no question here that his friend with the melons will be able to fight off his male attackers (in his 2008 depiction of the joke, Damani portrays the terrorists as men, and in contemporary media discourse the armed groups were gendered as male).Footnote 43 Given the context of events underway in Algeria, this short anecdote reveals that a serious anxiety about loss of masculinity may have existed among men during the Dark Decade. This tension appears to have revolved around men proving unable to protect their bodies and being subjected to what they may have considered a humiliating and emasculating ordeal, one that they could not openly discuss with others.Footnote 44 This narrative reminded listeners that men should fear losing control of their ability to protect their bodies from attack. The story would strengthen preexisting ideals of masculinity while suggesting that Dark Decade circumstances could inflict emasculating horrors at any moment upon any unfortunate man who happened across a fake checkpoint.

A joke that Moussaoui analyzed in his scholarship likewise stresses the emasculation of civilian men at checkpoints. It is as follows:

[A] citizen [is] held up by a terrorist who, to humiliate the man more, asks, “Who between the two of us is the man? You or me?” Without getting flustered, the citizen, pointing to the revolver of the terrorist, responds, “Neither you or me. That there is the man!”

[Un] citoyen [est] braqué par un terroriste qui pour mieux l'humilier lui demande: “Qui de nous deux est l'homme? Toi ou moi?” Sans se démonter, le citoyen, tout en désignant le revolver du terroriste, répond:“Ni toi ni moi! C'est celui-là l'homme.” Footnote 45

Like the previous joke, this one plays with incongruity to potentially provoke laughter while also starkly reminding the listener of the conflict's horrifying nature. In setting up the interaction between the terrorist (insurgent) and the man, the general assumption is that the terrorist (once again, the rebel is gendered as male) intended for the citizen to respond that he, the terrorist, was the man. In this scenario, the civilian victim would assume emasculation, according to the widespread norms of Algerian masculinity and accepted male social behavior. Rather than bowing to this pressure, however, the citizen insists that the armed man also is not a true man. The punch line of the victim (who might very well be killed upon the culmination of the joke) insinuates that neither man in the scenario proves to truly be a man. All of the power or rujūla resides in the weapon. In asking who between them is the man, the insurgent asks which party is more powerful or dominant. The victim's response reminds him that masculine power is not inherent but derived from access to might, in this case the gun.

Although this joke points out that the man who fell victim to violence as well as the one who perpetrated it both lost or never possessed masculinity, at least the person wielding the weapon was in closer proximity to manliness. Moussaoui asserts his conviction that by labeling the gun as the true man in the situation the terrorist intended to humiliate the unfortunate citizen.Footnote 46 Consequently, the armed man held the position of superiority, or masculinity, in this circumstance, thereby rendering the everyday Algerian citizen helpless and emasculated despite the numerical superiority of the citizen group (Mundy estimates that there were upward of 25,000 members of the armed groups at their largest point).Footnote 47 What is more, in the famed movie Bab El Oued City, filmed in highly contested terrain of Algiers during the Dark Decade, a gun appears to mark the transition of a character from boyhood to manhood. Although the two principal young male figures vie for the upper hand, the true power resides, according to Mundy's reading of the film, with the nefarious, if obfuscated, men who wield weapons.Footnote 48

The anonymous author of this gun-as-man narrative may have wanted to send a similar message—that the gun had triggered a displacement in the meaning of masculinity. Manhood no longer rested with the young men of the country but instead with guns. The joke teller evokes a dark humor with this anecdotal observation of a contemporary Algerian society ripped asunder by the struggle between the state and insurgent groups, and anyone willing to step into the fray with a weapon, a nod to the ambiguity of violence during war and the possible implications it may have had for gender norms. Above all, however, this joke advances the notion that the possession of weapons, a previous sign of masculinity in the country, still held clout, even as masculinity might move to authorities greater than the men themselves, such as the tools of the war unfolding around them.Footnote 49 Once again, this anecdote normalizes for listeners previous ideas concerning roles that men should fulfill to prove their masculinity and suggests areas in which men may have shortcomings due to Dark Decade violence.

Beyond failing to confront danger and protect women, some jokes insinuated that men would try to escape death by pusillanimous means, even if by doing so they actively took part in the victimization of women. One such joke proceeded as follows:

A bus ends up at a fake checkpoint. The terrorists make everyone get off the bus. The leader then announces, “We're going to kill all the women and rape the men.” A second later he starts to correct himself (“No, wait!”), but one of the men from the bus pipes up, “You said kill the women, rape the men, and that's that.”

Ḥbes bus fī faux barrage. Al-irhāb habṭou an-nās, ū qālhum al-chef, “Dorka, noqtolū an-nisā’ ū naghtaṣbū ar-rijāl.” Daqīqa omba‘d fāq ma‘ rūḥu bālak ghaleṭ, “Asstanāw! biṣaḥ niṭaq wāhid min bus qālhum: lā qolt toqtel an-nisā’ ū taghtaṣib ar-rijāl ū khlaṣ!”Footnote 50

The man's insistence that the terrorist leader uphold his initial, unintended statement proves humorous; the man is not in a position to save the women or himself, so he opts for a more cravenly action. In this world of humor, one of gender relations turned upside down for comedy, men not only fail to protect women and their communities but go so far as to sacrifice the lives of women and submit themselves to rape to avoid being killed. Other contemporary anecdotes similarly highlight the cowardliness of civilians and their pitiful place in the conflict. In this joke, however, the laughter springs from the man's depletion of his virility for the sake of self-preservation.

Another reading of this joke is possible, in which the man pipes up and interrupts the terrorists because he secretly desires to be penetrated by the armed men. In this scenario, the man further admits to his purported lack of rujūla. This interpretation appears unlikely to be the one that the original joke teller intended his audience to understand; if the man is fulfilling a hidden desire then the joke loses its comic sting. The man would be revealing his eagerness to allow himself to be raped to spare the women from sexual violation, but allowing the terrorists to murder them in the end. Although this reading may serve to critique a repressed desire on the part of men to participate in male-on-male sex, the original take on the joke calls attention to the cowardice of men. It falls more in line with the olive farmer anecdote that stresses the victimhood and subjugation of civilians when confronted with terror, a terror that reduces the men in these jokes to emasculated weaklings by the prevailing social standards. This demonstrates the inability of civilian victims to find a voice when faced with the weapons of terrorists; rather than expressing themselves courageously or intervening to try to stop violence or protect women, as the listener might expect, the men pipe up only to reaffirm their helplessness to alter the circumstances.Footnote 51 Once again, this joke may have alleviated actual fear of enervation and sexual assault, while also reminding listeners of the social conventions surrounding masculine behavior, namely that men should be capable of protecting themselves and extending that protection to women.

Caricatures commenting on violence and how it impacted gender and family roles also abounded during the height of the war. In particular, like the weavers of emasculating jokes, Algerian caricaturists, some of the most widely celebrated cartoonists in the Francophone and Arab worlds, portrayed men in Algeria at the peak of violence during the Dark Decade as lacking typically virile characteristics. They also employed the gun as a symbol of masculinity and courage in the presence of dangerous enemies. Figure 1, drawn by Ali Dilem, employs gender role reversal. A man is emasculated by Algerian social standards as “women fend off a terrorist attack.” That same day in Dilem's habitual newspaper Liberté a journalist had covered the story of women defending themselves and their homes from members of an armed group in the northwestern Algerian province of Tiaret.Footnote 52 The caricaturist took inspiration from this account to depict women filling the gap that men supposedly were leaving in Algerian society at the height of the war.

FIGURE 1. Dilem's “Madame Algeria” steps out to protect her community. “Le Dilem,” Liberté, 19–20 June 1998, 23.

The cartoon goes a step further than the article, however. The caricature features Dilem's famed Algerian everywoman unleashing a veritable earthquake on preconceived ideas of correct gender relations and roles. From the beginning of his cartooning career in December 1990, Dilem used the woman, to whom he gave the name “Madame Algeria,” to stand in for the civilian population of the country as a whole.Footnote 53 The drawing has the haik-clad woman toting a gun as she heads out the door of a domestic space. A man, presumably her husband, queries, “You're going where at this hour?” She replies as she heads toward the threshold, “I am going to join my girlfriends for a search and sweep operation.” Depending on a number of factors, including education, employment, socioeconomic status, and geographic location, during the 1990s many women Algeria were not free to go out in the evenings. What is more, curfew was in effect in some parts of the country, further prohibiting women from circulating freely at night. The man's question, had he posed it in a context outside of this violence, would have come across as a husband exerting his patriarchal control over the woman by asking her what she was doing by going out late at night (even without the conflict some Algerian women did not venture out at night). The humor lies in the contrast between the husband, who still attempts to exert patriarchal control, and the wife, who is going outside to engage in warfare that he can not or will not undertake. Even during the country's War of Independence women generally did not bear arms as their male comrades did.Footnote 54 The woman leaving to patrol with her “group of girlfriends” stresses that men in general in the neighborhood are, like the husband pictured here, failing to uphold the typical gender roles expected of them.

Finally, to add emasculating insult to injury, the man sports an apron and a child clings to his side. These attributes further communicate that he occupies the position previously held by women in the family in Algeria, that of child rearer and homemaker. Here, the man has been effectively effeminized. The woman is willing to put her body on the line, whereas he is not. Dilem's decision to show a woman carrying a gun as well as a blood-laden ax signals that she controls or possesses masculinity. In fact, the caricaturist consistently chose to highlight the masculinity and power of the insurgents at the expense of other figures, such as the civilian armed militias or state soldiers, by showing the rebels holding guns and blood-soaked blades as possible stand-in phalluses. Madame Algeria is in fact one of the only civilians ever to use weapons to confront the armed rebel groups in Dilem's cartoons, despite the participation of tens of thousands of men across the country in armed civilian militia organizations.Footnote 55 Other caricaturists portrayed only the insurgents toting weapons.

The point of Dilem's cartoon becomes all the more powerful when one learns that one of his former colleagues, Mohamed Benchicou, created a woman editorialist, Ines Chahinez, under whose name he published columns critical of “Islamic fundamentalism.” According to another writer who worked for Le Matin, Benchicou's paper at the time, by using the voice of Chahinez the editor wished to shame fellow Algerian men into speaking out as well. Through writing, staging trials of lead political figures in the country, and leading the way in anti-fundamentalist protests such as the one in Algiers on 22 March 1994, some Algerian women prominently denounced the elements responsible for the “period of terrorism,” the state and the rebel forces. Morsly has quipped that “paradoxically (given rife violence against women), the 1990s saw in Algeria the unprecedented development of women's voices (les paroles féminines).”Footnote 56 The idea of women filling roles generally occupied by men in the unique contexts brought about by the civil conflict, then, would not only provoke comedy. Instead, just as Benchicou hoped through the creation of Chahinez, it would shame men into vocal opposition.Footnote 57 If Dilem's cartoon worked in a similar manner, the artist hoped to prompt men to assume the position of masculine protector of the home by pointing to an example of a woman occupying that manly role, thus reinforcing previous gender stereotypes.

A popular anecdote from the 1990s similarly places a weapon, or symbol of manliness, in the hands of a woman in ways that are unexpected. I was able to recover two versions of the joke. The anecdote places either a horny man in a luxury car or a taxi driver in a run-of-the mill cab cruising around the working class Algiers neighborhood of Belouizdad after curfew. The man picks up a woman in a niqab who he sees on the side of the road. Getting excited and hoping to score with the oddly silent stranger, he asks her if she would like to go to the forest. The figure sitting in the car beside him remains silent. He takes her taciturnity as consent for this idea and begins his ride out to a grove of trees where he hopes that the impromptu couple will be able to get it on. The driver attempts some conversation with his companion, but still she does not speak. Upon arrival at an intimate location, they both get out of the vehicle. The man goes to his truck and pulls out a piece of cardboard and places it on the ground so that they will have a place to consummate their relationship. As the man turns to invite his companion to join him near the cardboard, the woman lifts up her outer garment to reveal a large Kalashnikov; it transpires that she is actually a member of a rebel group. Timidly, the man motions invitingly toward the cardboard and squeaks out, “Mā tḥabīsh taṣallī māʿyā?” [Don't you want to pray with me?] (The man is now insisting that his actual intended purpose was to use the cardboard as a Muslim prayer rug, instead of for extramarital sex.)Footnote 58

This joke relies heavily upon the unexpected to inflict its comedic sting. As other jokes from the “Dark,” it pokes fun at a subset of characters who were traditionally the butts of Algerian jokes, in this case a man horny enough to seek sex with an unknown woman at night. The man's sudden turn to religion (embodied by his physical turn from the woman to the impromptu prayer rug) as a mechanism to save his skin appears ridiculous, given that he was seeking to engage in what might be considered an impious act. The apparition of the Kalashnikov where one might least expect it (under a woman's garments) signals to listeners that the man's potential demise at the hands of a woman may be imminent; the unexpectedness is further emphasized by the man falling victim to an arms-bearing female assailant that he was hoping to sleep with.Footnote 59 This outcome and the laughter inspired by its incongruity reinforce the preexisting gender norm that men should tote weapons and be able to defend themselves.

Jokes and cartoons thus emphasized the supposed weakness of civilian men and inability, in the context of the 1990s crisis, to perform behaviors commonly accepted among Algerians as signs of rujūla. These narratives functioned as reminders of masculine ideals and pointed out that the armed struggle disrupted the capacity to live up to them. At the same time, the very act of denouncing the violence and its agents offered men a sorely needed occasion to recapture their masculinity.

MASCULINITY REDEEMED THROUGH HUMORISTIC EXPRESSION

In late 1991, with the assistance of UNESCO, Groupe Aïcha, one of a dozen prominent women's rights organizations in Algeria, issued a 1992 planner filled with information about the history of women's rights in the North African country. One page of the agenda listed “Proverbs and Sayings of Popular Arab and Kabyle Tradition.” The compilers of the adages apparently intended to criticize their inherent misogyny. For example, one stated:

Feminists recognized and circulated this saying, which they identified as well known and rooted in the country's folk culture in late 1991, as they wished for better times ahead.

The contents of the agenda signaled that at least some intellectuals, and by extension potentially Algerians on a larger level, were aware of the publication; over a dozen Algerian cartoonists contributed work that addressed issues related to women to fill small spaces throughout the planner. The cited couplet evinced a commonplace association of the act of speaking with masculinity and silence with a process of emasculation or a reiteration of femininity, in which the latter embodied weakness or a dearth of courage. The proverb implies that the person staying silent has done so explicitly to avoid death. This decision makes the person a “girl,” an insult in Algerian communities if directed towards a cisgender male.

Algerian writer Tahar Djaout was the first journalist murdered during the civil conflict. He was shot outside of his home by a purported GIA militant on 26 May 1993 and passed away a week later. Djaout apparently modified the common proverb to comport with the context of the early 1990s. This version, often presented as proceeding from Djaout yet absent from his published writing as far as I was able to discern, is the following:

If inspired by the proverb correlating speech with masculinity and silence with femininity, then this verse may have been understood among contemporary listeners to mean that the act of speaking while under threat evoked not only courage but also masculinity. The connection between maintaining silence and dying in both versions suggests cross-pollination between the two. Additionally, the early Dark Decade context in which Djaout reportedly uttered these words and during which wide swathes of Algerian communities, particularly intellectuals, assigned them to the murdered writer, indicates that listeners may have connected the proverb with the Djaout version, and by extension believed that speaking entailed rujūla. Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu also observed in the context of 1950s Kabylia that ideas of manliness and virility were inextricably bound up in men's participation in public life as well as outward expression of opinions.Footnote 62 I do not mean to collapse the differences between this small portion of the Algerian population living in a period predating the 1990s by several decades. However, Bourdieu's earlier remarks concerning Kabyle social structures, still viewed as legitimate by Algerian scholars, echo wider evidence of masculinity being linked to voice.Footnote 63

Joke tellers and caricature artists refuted silence throughout the Dark Decade in ways that upheld ideals of masculinity in Algeria. On at least one occasion, caricaturists replicated the image of a brave anticolonial soldier, the epitome of rujūla in the country's social memory, to apply it to themselves. In a cartoon published in El Manchar in February 1992, Dilem and his frequent partner in satire, the editorialist Saïd Mekbel, advertised the new comedic paper they were launching in conjunction with a number of other artists and writers. The paper was called Baroud (Arabic for gunpowder). In this cartoon, probably not drawn by Dilem (judging by the style), two musket-holding men stand on top of a hill looking out into the distance (see Fig. 2). These men wear clothing reminiscent of the 19th-century Zouaves or their resistors. They could be standing in for this group of men in Algeria that assisted the French, or their colonial opponents, who sported similar attire. If representing the latter (a strong possibility given how commonly Algerian cartoonists evoked historical scenes of Algerian resistance against colonialism in their work), the cartoonist and editorialist are being depicted as the predecessors of the mujahidin in nationalist lore. The caption of the image (not visible here) reads, “Saïd Mekbel drags along the first recruit of the satirical journal.” Intertextually, the style of this drawing hearkens back to the earlier tradition of cartoonists using their art to glorify resistors of French occupation as the ultimate Algerian heroes.

FIGURE 2. “Saïd, do you think that with the two of us we are going to succeed?” “Bop! You know Dilem, we'll open fire and see!” Unknown artist, El Manchar, 33 (February 1992), 11.

The phrase “open fire” is a play on Baroud (gunpowder); their actions may have explosive results. The artist behind the image also is likely referencing Napoleon's famous quip when approaching battle, “We'll jump in and see.” The allusion describes two intellectuals who do not know what launching the newspaper will bring, but are willing to embark on the venture anyway.Footnote 64

Although Mekbel and Dilem might have intended to poke fun at themselves, readers might have gleaned from the sketch that the two artists were behaving heroically and manly, complete with masculine weapons, by launching the satirical paper despite not knowing whether it would be successful. Here, they may have been stating that their heroism in moving forward with the plan to start a new review was tantamount to taking up weapons against a dangerous enemy to protect communities. By the time that this cartoon appeared, the security situation in the country had significantly worsened, and intellectuals were facing death threats. Dilem's question to Mekbel suggests that his true concern lies in gaining an audience and thereby obtaining commercial success (this cartoon appeared in a fellow satirical journal, El Manchar, designed most likely to prompt readers to follow this new publication). An additional reading of the cartoon might insinuate that they are facetiously comparing themselves and their experience of starting a new periodical to a fight against colonial occupation or, at the very least, a battle; after all, the venture to start a new newspaper is not quite on par with taking up arms. Yet a broader consideration of the context may elucidate a message concerning the cartoonists’ intertwined masculinity and capacity to speak.

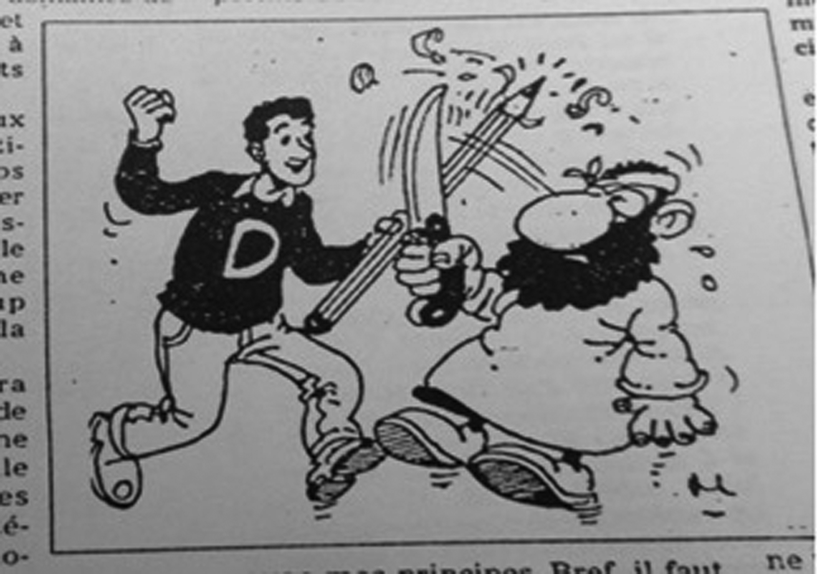

In interviews that I held with over a dozen cartoonists, these men generally referred to the work they were engaged in, depicting and denouncing the worst carnages of the war, as “combat” or “defense of the country.” This combat was overwhelming masculine.Footnote 65 By the early 2000s, in the over thirty-year existence of Algeria's cartooning industry, only one woman, Fatima Beddiaf, known by her pen name Daïffa, had engaged in the craft.Footnote 66 Men like Dilem and Mekbel persisted despite repeated threats against their lives as artists and intellectuals, and even the murder of their colleagues. The caricaturist Maz once depicted Dilem fighting with an insurgent, using his pen against the rebel's blade (Fig. 3). The artist's pen rendered Dilem's primary instrument of cartooning on par with the insurgent's knife. Maz may also have been attempting to ridicule a statement that GIA leader Sid Ahmed Mourad, alias Djaffar al-Afghani, supposedly issued in November 1993, declaring, “Those journalists who fight against Islamism through the pen will perish by the sword.”Footnote 67

FIGURE 3. Maz shows Dilem besting a rebel's blade with his pen. Caricature by Maz in article by Tahar Hani, “Avec le dessin, j'exorcise mon chagrin,” El Watan, 23 December 1999, from the dossier on Dilem and the press, Library of the Centre Culturel Algérien, Paris, France.

Nevertheless, this cartoon appeared at the top of a page in the popular French language newspaper, El Watan, above an article celebrating Dilem for his accomplishments as a caricaturist. Given this context, Maz most likely referenced the adage, “the pen is mightier than the sword,” to highlight Dilem's courage in standing up to terrorists. In the cartoon, the artist appears chipper and ready to fight the stiff-seeming insurgent, identifiable here by his use of a knife. Algerian intellectuals such as Maz and even higher-ups in the rebel groups (such as al-Afghani) may have seen the act of expressing opinions that countered insurgent rhetoric as on par with the rebel's military strength, symbolized by a blade. Taken together with the cartoon above of Dilem and Mekbel carrying weapons as proto-nationalist resistors, it is possible to conclude that these artists perceived in the undertaking of their work an exercise of their rujūla.

CONCLUSION

The complex and sometimes contradictory messages contained within Dark Decade emasculating comedy suggest multiple ways of being or, conversely, failing to be manly. They also point to diverse responses on the part of mainly intellectual, urban-dwelling men to war-induced disruptions of masculinity. Furthermore, these reactions did not entail men upholding patriarchal norms, oppressing women, or turning to violence and anger to try to rectify tension and reassert their masculinity, all of which have been the focus of most scholarship on masculinity during the Dark Decade. Rather, at the height of the civil conflict between the state and rival armed rebel groups, humor proffered a unique space for some Algerians to acknowledge, accept, reject, play with, and attempt to push back against the general situation of helplessness that some civilian men appear to have experienced during the crisis. What is more, the body of humor mocking Dark Decade circumstances analyzed above suggests that jokes and caricatures, with their propensity to allow their creators to reimagine dire realities, can serve as critical spaces for the elaboration of masculinities and their possible limitations in a Middle Eastern and North African context.

But just as comedy producers commented upon the enervating circumstances of the Dark Decade, humor reinforced gendered taboos contained within puns and satirical drawings and opened up areas for men to push back against these same emasculating situations. Noncombatant joke tellers and caricaturists used their arts of comic expression to recapture the collective rujūla that the circumstances of conflict put in jeopardy. Comedy, then, functioned to buttress norms surrounding gender relations while also allocating men opportunities to recapture some of their manliness with their voices and through the expression of their opinions. Examined in tandem with critical humor theory, the jokes and cartoons from this period encapsulate a stark moment of Algeria's past, as it was lived by a civilian majority forced to grapple with a universe turned askew and communities torn asunder. This suggests new possibilities for inquiries into gender formation in the region.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank the anonymous referees for their careful reading and critique of this manuscript. Sara Rahnama additionally read and commented on an earlier draft of the piece. Indira Gesink, Suha Kudsieh, Sara Scalenghe, and Ezgi Saritas also offered constructive feedback on a presentation based on this work at the Middle East Studies Association's 2017 annual meeting. Finally, the author would like to offer her gratitude to the American Institute for Maghrib Studies, Centre d'Etudes Maghrébines en Algérie, Robert Parks, Karim Ouaras, the Ohio State University Office of International Affairs and Department of History, the Council of American Overseas Research Centers, and the seventy-two oral history narrators for their generous support of the research presented here.