In January 2019, I was in Mashhad for two days as part of a longer visit to Iran.Footnote 1 A friend showed me around the former Jewish quarter, where today hardly any memory of its Jewish past remains. Mashhad is the second largest city in Iran, located in the province of Khorasan, and the most important place for Shiʿi pilgrimage in Iran, as it is home to the shrine of Imam Reza. The Mashhadi community stands out in the history of Iranian Jews, since they were forced to convert to Islam in 1839 and lived secretly as Jews for several generations.Footnote 2 However, there also were others, who did not define themselves clearly as Jews, Muslims, or even converts, since their self-understanding, their practices, and their relationships with the various (Muslim and Jewish) communities did not fit into any of these categories.

Today there are no more Jews living in Mashhad, and the space for ambiguities is extremely small when it comes to official religiosity in Iran. Although Judaism is among the legally recognized religions and there are several active Jewish communities in Iran, the drive of the authorities to construct the Iranian public sphere as religiously homogenous is predominant.Footnote 3 However, ideas of religious identity and religious boundaries were not always as rigid as they are today. Iranian Jewish historiography usually invokes the Pahlavi era (1925–79) as the time of religious freedom and pluralism, since the Pahlavi drive for modernization and a strong state required the suppression of religious difference to a certain degree. Although most Jews experienced considerable upward social mobility during this period, Iran's encounter with colonial modernity and accompanying concepts of exclusive national and religious identity had come to fruition by this time as well, leaving little room for multiple and overlapping identifications.

This paper deals with a time before ideas of modern nationalism and the religious identities they encapsulated gained a foothold in Iran, proposing that an understanding of Jewish life in Iran in the 19th and early 20th centuries is only possible when we historicize our concepts of religious identity and belonging. As Mana Kia points out, “This range of Persianate selves not only challenges nationalist narratives but also reveals a larger Persianate world, where proximities and similarities constituted a logic that distinguished between people while simultaneously accommodating plurality. To be a Persian was to be embedded in a set of connections with people we today consider members of different groups.”Footnote 4

It is not my intention to put forward a notion of “Persia” by essentializing a polarity between the modern and the premodern era. Rather than representing a unique and monolithic position without contradictions, modern nationalism marks the site where different representations of the nation contest and negotiate with each other.Footnote 5 Neither is the purpose of this paper to recover an original history of the Mashhadis. The point is to analyze what the Mashhadis chose as worthy of remembering, as what they choose to recall constitutes their communal identity. Group memories are expressions of how communities locate themselves with respect to other relevant groups, for example with regard to the global Jewish community and to Iran as a (former) homeland. I argue that modern concepts of national identity and religiosity have influenced the Mashhadis’ process of memory formation, leaving no space for grey zones and multiple affiliations. However, this paper does not seek to assert “truths” about the Mashhadi past or judge claims about its continuity. When explaining controversial issues of Mashhadi identity, my aim is not to evaluate, validate, or invalidate such claims. Instead, I trace how narratives of the past have taken shape and how they influence and are influenced by changing concepts of identity, belonging, and convergence.

The Jewish Community of Mashhad

Although Jewish settlements in Iran date back to the 7th century B.C., the Jewish community in Mashhad was a relative latecomer. In the course of Nader Shah's (r.1736–47) resettlement policies, about forty Jewish families from Qazvin settled in Mashhad, where no Jewish community had established itself previously.Footnote 6 Due to its position along the Silk Road, Mashhad attracted Jews from other Iranian cities such as Yazd and Kashan. In the 1830s, the community encompassed about 2,500 individuals, an estimated 10 to 15 percent of the population of Mashhad at the time. In 1839, a riot erupted, during which the Jewish community was forced to convert to Islam. This event was called Allahdad (God given).Footnote 7 The main narrative states that the riot was triggered in connection with a dead dog, used for medical reasons by a member of the Jewish community, allegedly ridiculing the Muslim holiday of Muharram that was taking place at the time. It is likely that the perpetrators used this story as pretense to attack the Jewish community. Mehrdad Amanat ascribes the reasons for the outbreak to a combination of the following factors: “Great Power rivalries, changes in the economic status of some Jews, the pressures created by a renegade Qajar army, local elite rivalries, the local administration's ineptitude, and possibly imported European anti-Semitic ideas.“Footnote 8

The regiments of the Persian army involved in the riot had suffered a defeat in Herat in 1839 at the hand of the British and retreated to Mashhad. The disenfranchised soldiers, of whom a majority were Russian deserters and native Assyrian Christian recruits, saw the Jewish community as a scapegoat, as many Jews of Mashhad at that time were not only successful businessmen but also served British officials in the region.Footnote 9

Rather than a sudden outburst of irrational hatred, sources suggest that the riot also was the result of a rivalry between one religious authority, supported by the central government, against another religious authority representing a new interventionist attitude among the ʿulamaʾ. The latter, trustees of the Imam Reza Shrine, must have anticipated the value of the allegiance of a sizable community who as “new converts” would be dependent upon his favor: “Such protection could only be provided in the physical setting of the shrine, where non-Muslims could enter only after having converted to Islam.”Footnote 10

To avoid conversion, almost half of the community left for Herat, in today's Afghanistan; they thereafter constituted the Herati Jewish community. Some moved to other Iranian cities such as Shiraz or joined the Jewish community in Bukhara, although Albert Kaganovich states that Mashhadi migration to Bukhara was for business reasons and not due to persecution. According to Joseph Ferrier, two-thirds of the Jewish community left Mashhad in the 1840s.Footnote 11 The community narrative states that from 1839 onward, those who remained resumed Jewish practices in secret, while outwardly professing Islam, which included a change of name and regular attendance at the mosque. However, according to Ephraim Neumark (1947), a Jewish traveler and writer born in Eastern Europe who visited Mashhad in 1884, those who continued Jewish practices right after the Allahdad were a few individuals who lived rather isolated and it was only after about 30 years, that Jewish practice accumulated renewed attention in private.Footnote 12 The extent to which they practiced Judaism differed significantly however, as did the ways in which individuals accommodated Islam in their daily lives. Over time, this diverse community became the closely-knit community of Jadid al-Islam (New Muslims). From the 1920s onward, when the Qajar dynasty collapsed and Reza Shah Pahlavi came to power, the Mashhadis practiced Judaism more openly.

Today's self-representation of the Mashhadis frames the Allahdad and the ensuing “underground period” as a mere shift of a homogenous and unchanging Jewish practice from public to secret (and later back to public again). Hilda Nissimi refers to this “memory of sacred history” as the most important layer of identity for the Jews of Mashhad.Footnote 13

The mainly orally transmitted narrative of the past is indeed crucial to constituting today's communities, which sustain it at commemorative events and in academic and community publications, memoirs, and personal conversations.

One could ask how it is that the descendants of the Mashhadis, who had immersed themselves in non-Jewish culture and society, have come to act so much like Jews today—to an extent that they are considered more Jewish than others.Footnote 14 Daniel Swetschinski argues that, in the case of the Portuguese crypto-Jews, it was not so much the loss of memory of Jewish traditions but the rejection of the memory of their crypto-Jewish past that helped define their later Jewish identity.

Similarly, Mashhadi history rejects elements of the past and reframes them to conform to contemporary demands of Jewish identity. This was necessary for the Mashhadis, for whom neither Mashhad (after 1946) nor Iran (after 1979) proved a feasible homeland anymore. Many Mashhadis, most of them by then already living in Tehran, emigrated to Israel in the 1950s, and the bulk of the community came to the US following the Iranian revolution in 1979. Ideas about Jewish identity, as encompassed in the national framework of the state of Israel, affected the Jews of Mashhad in particular: when many Mashhadis were waiting in Iran to get permission to immigrate to Israel in the 1950s, some of the Israeli authorities had doubts about their status as Jews. Yitzhaq Raphael, head of the Jewish Agency's Department of Immigration, turned to the two chief rabbis of Israel for an authoritative opinion on their religious status. Rafael Patai writes, “The reason for this step was that in certain religious circles, doubts were entertained about the Jewishness of the Meshhed Jews, similar to the doubt that was attached to the status of the Ethiopian Falashas. The significance of the issue lay in the fact that Israeli law accorded the right of immigration to Israel to all Jews, but only to Jews; the Israeli institutions were supposed to bring to Israel only Jews who had the legal right to immigrate. Yitzhaq Raphael felt that before he could mobilize institutional help for the Meshhed Jews, he first had to ascertain whether rabbinically they were considered Jews who had the right to come to Israel.”Footnote 15 Although the Ashkenazi chief rabbi, Yitzhaq Halevi Herzog, demanded more investigation and proof of the Mashhadis’ Jewishness, the Sephardic chief rabbi, Ben-Zion Meir Hay Ouziel, ruled that they were “pure Jews.” Finally, the Israeli authorities reached the conclusion that the Mashhadi Jews were rightful Jews, and they received institutional help to come to Israel.

This incident shows that proving a “true” and unbroken Jewish identity in the eyes of the state of Israel was of vital importance for the Mashhadis to be accepted among the global Jewish community, after they had to leave Iran and steer themselves toward a new (symbolic) homeland.Footnote 16 Their attachment to the Land of Israel, which most contemporary Mashhadis attest to, is one variant of the aforementioned “sacred memory,” as it is retrospectively located in the community's early days and also updated to include modern Jewish-Israeli history. But before discussing the history of the converts’ lives in Mashhad and its contemporary interpretation in more detail, I will address some aspects of Iranian Jewish historiography that are relevant to this endeavor.

Historiography of Jews in Iran and the Middle East

Recent scholarship on Jews in the 19th- and 20th-century Middle East increasingly shows how Jews engaged intellectually and politically in their home countries.Footnote 17 Despite this departure from one-sided portrayals that cemented a mutual exclusiveness between Muslims and Jews, the concept of religious identity has experienced little historicizing.Footnote 18 European missionaries, government officials, and European Jewish institutions that have perpetuated a Eurocentric and essentialist understanding of religious identity in their writings have informed the accounts of Jewish communities in 19th-century Iran. In many of these texts, the theme of isolation and oppression recurs, coupled with the alleged ignorance of Iranian Jews.Footnote 19 Christian missionaries, some of whom were themselves Jewish converts (like Joseph Wolff or Henry A. Stern), explicitly targeted Jewish communities in the Muslim world, as their employers regarded them particularly suited for this task due to their knowledge of Hebrew and Jewish traditions. Although many European and later American missionaries and travelers tended to observe Iran's society from a position of cultural or civilizational superiority, with open denigration or misconceptions about Islam and Muslim culture, they also purported the idea of a singular and privatized religiosity.Footnote 20 This process has led to the alienation of individuals not only from each other but also in their ways of defining themselves according to worldviews that did not fit into these official narratives.Footnote 21 Within this framework, it is not possible to grasp the multiple affiliations of Jews in 19th- and 20th-century Iran other than in terms of force, secrecy, or deceit.

In 19th-century Iran, where the Mashhadi narrative originates, categorical differences relating to religion did not need to be absolute or mutually exclusive. Although it was a clearly hierarchical society, the social structure allowed for multiplicities of meaning and interpretation. Identities were constituted relationally, so that the meanings of origin and belonging could be multiple and shifting. This multiplicity produced an “understanding of difference as overlapping gradients, rather than as mutual exclusivity.”Footnote 22

This is not to say that there were no differences between Iranian Jews and other Iranians, but formulating categories with discrete borders like “Iranian” and “Jewish” is a way of knowing rooted in modern epistemology. The identities of Mashhadi Jews, and to a certain extent Jewish identities in Iran more generally, might be seen today as a set of paradoxes. But seeming contradictions appear so through the lens of our present. Rather than assuming identifications as a stable set of beliefs or practices, I argue that there were overlapping identifications with porous, permeable, and indeterminate boundaries. This approach also departs from notions of a “hybrid” identity of converts, as hybridity assumes pre-fixed identities mixing with each other.

The teleological histories of modern nationalism eradicated the shifting and at times indeterminable identities of 19th-century Iran. As a result, many historical accounts resort to a rather rugged classification of Jews as distinct from their surroundings.Footnote 23 In particular, they gloss over the perspective of individuals who changed their religion sometimes more than once and maintained affiliations with different religious traditions simultaneously. During my fieldwork, I realized that the way in which religious identities were defined, negotiated, expressed, and perceived in Iran did not correspond with the idea of religiosity as an individual, inner conviction.Footnote 24 Neither was religious identity a category itself; its dissection from the political, cultural, and economic context made actions of individuals unintelligible. There were more realities than being Jewish, Muslim, or a convert. There were gradual transitions from one direction to the other, during which individuals often were in a state not clearly definable by the terms at our disposal.

In the course of the 20th century, ideas of religious and national belonging further narrowed. The evolution of political Zionism and later the 1979 Iranian revolution propelled concepts of Iranian and Jewish identities according to a rigid religious-national teleology, leading to the incorporation of Jewish histories into a framework of clear boundaries and political loyalties. The history of the Jews of Mashhad shows how these processes have affected the constitution of a distinct group memory.

The Mashhadi Narrative

The community narrative consists of a few central elements that exclusively relate to religious aspects such as forced conversion, keeping Jewish faith in private, outwardly pretending to be Muslim, and secret religious practices. These elements testify to the steadfastness of the Jews to their ancestral faith and explain all actions based on Jewish history alone, enforcing the boundaries of the environment in which the Jews had lived.

As the 2019 brochure of the United Mashadi Jewish Community of America shows, Mashhadi communal identity celebrates the Allahdad as a formative element (Fig. 1).Footnote 25 The text notes that, in accordance with the teachings of 12th-century sage and rabbi Moses Maimonides, the Jews of Mashhad accepted conversion to spare their lives. With the invocation of Maimonides, explanations for the event resort exclusively to religious legitimacy, disregarding social and economic circumstances that might have led the Jewish community to accept conversion. Consequently, the text frames all reference to Islam and Muslims in terms of “unwanted” coercive “force.”

Figure 1. Publication of the United Mashadi Jewish Community of America. Property of the author.

In the following sections, I will show that the border between Jewish and Muslim practices was not as clear-cut as retrospectively assumed, although the relationship to Islam took on a distinct character for the converts in Mashhad. I will focus on the three main elements of the narrative: forced conversion, inner and outward religiosity, and secrecy.

Forced Conversion

The official Mashhadi narrative tends to explain the forced conversion in 1839 based on Muslim fanaticism and hatred toward Jews (blood libel). However, the riot, in which more than thirty individuals were killed and houses looted, had a profound political dimension that went beyond religion and beyond the borders of Iran: it was a period of political crisis in Iran, in which the province of Khorasan was deeply involved, particularly in the Anglo-Iranian war over Herat. Colonial encroachment by the British and Russian empires and ongoing political fragmentation affected the relationship between Shiʿi Iranians and religious minorities, who appeared as the sole beneficiaries of foreign intervention. As successful tradespeople, the Jews of Mashhad were in a position of economic advantage, and their connections to the British, for whom they acted as trading contacts, moneylenders, or messengers, rendered their allegiance questionable for the Shiʿa majority.Footnote 26

Yaghoub Dilmanian provides a detailed account of the conversion. During the riot members of two Jewish families, who already had close ties to the Muslims, held a meeting and decided to accept Islam. These six or seven individuals announced their decision to the looters on the street, then went to Mirza Ashgari, the Imam Jumʿah of the Shrine, and converted to Islam by saying the shahada. The Imam congratulated them, gave them Muslim names and distributed sweets among them. “According to the Imam Jomeh's ordinance, those who had initiated the mass conversions were obligated to recruit more converts. However, many tried to stall and used any excuse to avoid an audience with the Imam Jomeh. Up to a month after the incident, very few had actually gone to the Imam Jomeh. They all began to orient themselves with the teachings and rituals of Islam, so they could present themselves as Moslems.”Footnote 27

This context is important to understanding the fault lines within the community as well as agency across religious boundaries, as the families who acted as intermediaries between religious authorities and the Jewish community had “considerable power” and saw themselves as leaders of the Mashhadi Jews. There also was the possibility of evading the Imam Jumʿah's wish for the Jews to convert “officially” in his presence.

Jews, as a minority, were a vulnerable group that suffered especially in times of upheaval.Footnote 28 Members of the majority could employ existing inequalities and stereotypes to enforce privileges and interests. But the Jews of Mashhad also flourished at times and had other social roles than being “Jews.” Many histories of Mashhadi families, for example, oscillate between memories of wealth and respectability, on the one hand, and oppression and fear on the other. The latter aspect of the narrative is so dominant, however, that references to a good or even “normal” life in Mashhad only occur now and then, without destabilizing the main narrative.

A recently published memoir by Esther Amini, daughter of Mashhadi immigrants who came to the US in the 1950s, has shed new light on this.Footnote 29 Amini's father came from a financially successful, highly respected Jewish Mashhadi family and attended a London boarding school in the 1920s, an opportunity open only to wealthy Iranians at that time. In Mashhad, he had owned “acres of farmland and fruit orchards, raising sheep, goats, and chickens, all attended to by hired hands.”Footnote 30 Amini's great-grandfather, Benyamin Aminoff, born in 1847 and having lived most of his adult life in the “underground” period, was a successful merchant. He owned multiple slaughterhouses in Iran's province of Khorasan in addition to three caravansaries (one in Mashhad and two in Merv), a huge farm outside of Mashhad, and a profitable icehouse. He grew poppies to harvest opium, which he sold to pharmaceutical companies in Germany. As an offspring of the wealthy Aminoff clan, Amini's father celebrated his wedding accordingly: “The streets of Mashhad were lined with festive lanterns and red roses. My father wore a top hat and tuxedo; my mother, a French wedding dress. Pop had purchased Parisian lace embroidered with baroque pearls and had it stitched to a gown for his bride in Mashhad. They rode through the streets in a chariot drawn by eight rose-festooned horses. It was 1938, and the pomp and pageantry outshone all other weddings.” Footnote 31

By addressing previously neglected aspects of Mashhadi history, Amini breaks the common narrative pattern that she describes a few pages earlier: “For generations, my ancestors hid in plain sight, living a lie, pretending, adapting to a culture that wanted to annihilate them. They befriended Muslim neighbors and shopkeepers, spoke in their vernacular, danced to their Islamic melodies, cooked their foods, used their spices, and shouted their curses. Mirroring Muslims, they painted the palms of their hands with henna, rubbed it on their hairs, slapped dayerehs (framed rim instrument with jingles resembling a large tambourine), and wore chadors, only to go home and braid challah, light Shabbat candles, keep strict kosher, perform circumcision, and marry solely among themselves.”Footnote 32

The assumption that befriending Muslim neighbors and shopkeepers and sharing the same language, music, and food was part of faking a Muslim identity, whereas the Jewish identity would not have comprised any of these features, employs a constricted concept of Jewish identities severed from their environment. Rather than being mutually exclusive, privilege and oppression existed side by side and played out differently according to changing social contexts.

Amini furthermore acknowledges how her father longed for a return to Iran after having immigrated to the United States: “For Pop, uprooting was heart-wrenching. In Mashhad, the Aminoff name and legacy commanded multigenerational respect. There, he had once led a regal life surrounded by housekeepers, gardeners, fig trees, lemon groves, and acres of real estate. Even here in Tehran, men strolling the boulevards now tipped their hats, warmly acknowledging him.”Footnote 33

The Aminoff family might have been exceptional due to their financial success, but, although economic privilege did not necessarily guarantee political safety, the successful business networks of some Mashhadi families suggest interactions with the Muslim environment based on respect and agency rather than oppression, fear, and deceit.

Assuming that at least among some segments of the society there were “soft” boundaries between Jews and non-Jews in Mashhad, it is possible that they did not view mutual boundary breach as a threat and even could eventually amalgamate into one community. Differences in dietary and religious practices may not have prevented the sharing of a range of other practices between Muslims and Jews. Besides being engaged in trade networks, Jadids in Mashhad worked as arbiters for business and personal disputes, consulted by Muslims and Jews alike, or as midwives who delivered babies for Muslim and Jewish families.Footnote 34

Swetschinski makes this point when he suggests that “actual evidence for the difficulties . . . felt in living with a so-called split conscience is difficult to come by.”Footnote 35 Can we assume that some individuals were unaware that a particular opinion sprang from Muslim rather than Jewish tradition, or that they thought the splitting of opinions into separate traditions was unnatural or meaningless? Evidence suggests that the distinction made by the Mashhadi Jews between force inflicted on them by particular groups and a general appreciation for the authorities in Mashhad and Persian culture in general was not a mask covering an irresolvable deeper tension.

Jewish-Iranian identity has unique features that distinguish it from the Muslim tradition, but it also developed and existed in an interactive cultural milieu. Mashhad, renowned for religious orthodoxy and traditionalism, also was a space for intense exchange across confessional boundaries and heterodox currents, providing remarkable religious curiosity and debate, as I will show in the next section. From the mid-19th century onward, religious authorities countered this dynamic and aimed to control and homogenize the public sphere. Mehrdad Amanat ascribes this development to the rise of more conformist and legalistic interpretations of Islam, as well as to being “a response to early manifestations of modernity and European hegemony.”Footnote 36

The Split Between the “True” and the “False” Religion

The Mashhadi Jewish narrative has established a trajectory of unbroken, orthodox Jewish practice. Splitting individual consciousness into an inner religious conviction and an outwardly faked one sustains this unambiguous and unvarying Jewish identity. Many community histories evolve around how the Mashhadis kept Shabbat, slaughtered kosher meat, congregated for prayer in small underground rooms and married according to Jewish law, all under the threat of their Muslim neighbors exposing them.Footnote 37 In this depiction, the demarcation between inside and outside, between Judaism and Islam, is very clear. However, the missionary Joseph Wolff, who visited Mashhad in 1831, eight years before the forced conversion, gives an account of the interaction between some Jews and Muslims:

The Jewish Soofees of Meshed . . . acknowledge Jesus, Mohammed, and 124,000 Prophets, without feeling themselves bound to act under the control of any of these Prophets; . . . I met here in the house of Mulla Meshiakh, with a Hebrew translation of the KoranFootnote 38 . . . I frequently heard the Jewish Soofees at Meshed say that they had two religions: the zaher, i.e. the Exterior, and the baten, i.e. the Interior; or the religion of the people and the religion observed in their lodges. I tried to make them aware of the danger of their system, and of the reasonableness of a divine revelation, as contained in the Bible and the New Testament.Footnote 39

This account suggests that at least part of the Muslim and Jewish leadership in 19th-century Khorasan did not emphasize confessional borders. The Jews in Mashhad, who were active in Sufi circles, were primarily the leaders and learned members of the community, suggesting that they were part of an educated and rather wealthy stratum of the wider society.Footnote 40

Islam was part of the dominant culture, and there were clear asymmetries resulting from this hierarchy, thus influence was rather one-directional. Although Nadir Shah had requested the translation of parts of the Torah to Persian, the familiarity and embracement of religious and cultural texts from the Muslim tradition (including classical poetry and the Qur'an) was so common among Jews that they transcribed them into Judeo-Persian and Hebrew. These elements created shared spaces of spiritual and cultural practice, albeit predominantly for certain elites. Wolff's report reveals his limited understanding of these practices, as the Protestant views he had acquired in the course of his education informed his own religious outlook.

The Shiʿi concept of religious dissimulation (taqiyya), as well as elements of Islamic mysticism such as the complementary forms of esoteric and exoteric (ẓāhir and bāṭin), accommodate a simultaneity of religious identifications.Footnote 41 In some cases, individuals employed these practices to avoid persecution, but they also used them to gain certain privileges, or to facilitate daily activities and temporary interactions. A society in which religious belonging was not only an individual choice but primarily an element of communality and social coherence formed the backdrop to these developments.

Similar to converts in 17th century France, as Monica Martinat argues, “dissimulation as presented here was neither a potential lie nor a real lie about one's faith, but rather a means to satisfy the ideological requirements of authorities, who insisted on putting religion at the centre of individual and collective life. . . . in other words, this reality indicates that the ideal of an exclusive religious affiliation was not necessarily shared by a large group of men and women whose attitudes, both intellectual and practical, were much freer than has been supposed until now.”Footnote 42

The traditional separation of public and private spheres in Iran allowed for individuals to have multiple religious identities even after a conversion.Footnote 43 The necessity to practice different religions simultaneously thus created multiple forms of deviation from the ideal of a homogenous public sphere. Individuals finely calibrated expressions of public and private religiosity to uphold a certain degree of conformity, while at the same time actively transforming these religious practices. Therefore we can assume that a new boundary between Jewish and Muslim identities only developed some time after the Allahdad.

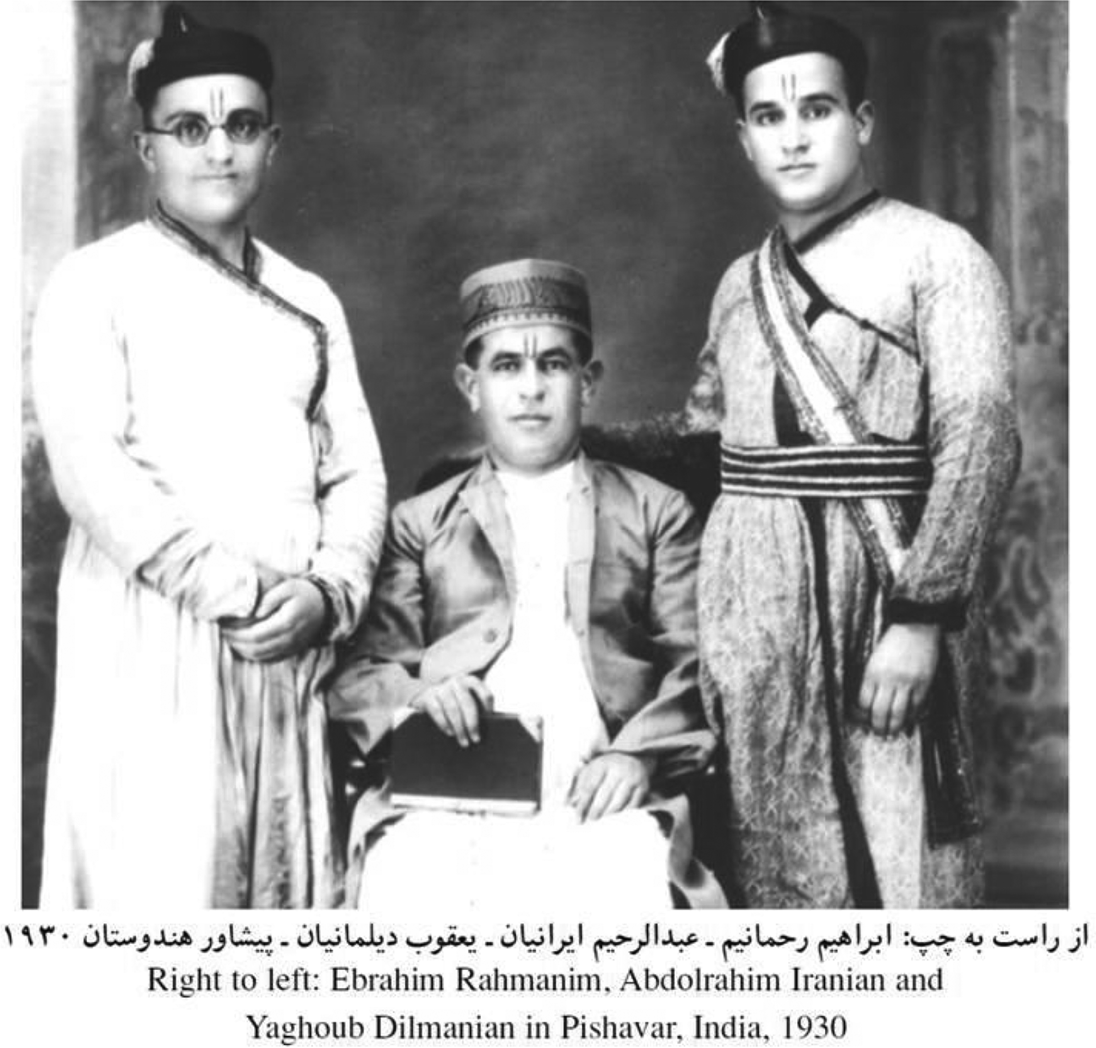

As businesspersons traveling between the centers of transnational trade ranging from Herat over Merv and Bukhara to Peshawar and Bombay, the 19th-century Mashhadis traded in furs, precious stones, spices, carpets, and silk (Fig. 2). They were highly mobile and resorted to a diverse repertoire of identifications. Nevertheless, the community memory ignores any advantages that this kind of multiplicity may have brought. On the most mundane level, an ability to present oneself in any number of guises created opportunities in an area in which tribal conflicts, smuggling, and monopolies were common.Footnote 44

Figure 2. Mashhadi merchants in Peshawar, today's Pakistan. Source: Shlomo Kaboli, Du Qarni Muqavamat: Tarikhi Yahudiyani Mashhad.

For Joseph Wolff, the absence of religious boundaries he encountered in Mashhad was hard to fathom. At times, he ascribed it to the alleged delusion of the Iranian people, who, he argued, had yet to understand that one could adhere exclusively to one religion. He notes: “Nissim is a complete infidel in sentiments: at Meshed he is a Mussulman, and a Jew at Sarakhs, Khiva, and on his journeys to Europe.”Footnote 45 This description confirms that individuals could don different religious identities depending on objective and place.

Many Mashhadis lived in the border region of Turkmenistan for several months at a time to conduct their business, while their wives and children stayed in Mashhad. In his memoir, Farajullah Nasrullayoff Livian describes how Jewish tradesmen living in Turkmenistan did not pay attention to keeping the Shabbat or eating kosher, and only adopted these practices toward the end of the 19th century. Since they were away from their families for a long time, some Mashhadis also took a second, Muslim wife.

About one hundred years later, when the Mashhadis had dispersed into a global but closely knit community, having Muslim relatives was something that one “did not talk about.” One of my interlocutors stated that the Mashhadi community in which he now lived frowned upon individuals who stayed in touch with their non-Jewish relatives in Iran.Footnote 46

In the late 1880s, a new emphasis on Jewish practices developed, which affected the Jews in Mashhad as well as among the communities in the border towns.Footnote 47 Although documentation is scarce on this development, we can infer from the few existing accounts that it affected the Mashhadis living in Turkmenistan insofar as they started to keep Shabbat (as a day of rest, not kindling a fire for dinner) and eat kosher meat. This development was possibly due to the influx of Jews from Herat, who remained in Mashhad after the Persian army had laid siege to Herat in 1854 and took all Jews that they considered Iranian subjects as prisoners back to Mashhad.Footnote 48

Practices and beliefs such as those familiar from the participation of Jews in Sufi brotherhoods meanwhile seem to have retreated. There is but one example of a manuscript, written by the scribe Eliayu ben Eliah fourteen years after the Allahdad, in 1853. It is a copy of “Yusuf and Zulaikha,” a medieval Islamic version of the story of the biblical prophet Joseph, written in Judeo-Persian. It points to the fact that Qur'anic and Sufi poetry remained a meaningful aspect of Mashhadi culture.Footnote 49

Individuals did rely on different religious sources in their search for truth and ways to break with what they perceived as outdated traditions. In several accounts written by converts, the authors mention that they carried a Qur'an and a Torah with them at all times, illustrating that both beliefs were equally important to a number of individuals at the time.

Secrecy

Historians of the Jews of Mashhad often frame the practice of Judaism in Mashhad as an “open secret.” Although in the surrounding Muslim environment there was an awareness that the Jadids still practiced Jewish traditions, the community narrative emphasizes that possible exposure was a constant threat and danger.

Joseph Wolff, who returned to Mashhad in 1844, just five years after the conversion, openly addresses the Jadids as “Jews” in a letter to the Imam Jumʿah, and sees no need to hide the Jewish identity of his protégés.Footnote 50 Several other sources confirm that the Jadids were referred to as "Jews", "Jadids", or "Muhammedan Jews” after the conversion.Footnote 51 Ephraim Neumark confirms that people knew that the “New Muslims” secretly kept their Jewish religion but that they tolerated it because the Jadids were a crucial element of the economy. He mentions that the police patrolled the city of Mashhad each night and “would detain anyone they found on the street, except for the Jadidis. Also, many of the municipal positions are assigned to the trustworthy Jadidis.”Footnote 52

Neumark mentions that some Jadids were in charge of the financial affairs of the shrine of Imam Reza. Assuming such central positions in the administration of a mosque would be difficult for converts for whom Islam was just a facade. Moreover, wealthy Jadids donated generously to the shrine's foundation, the Astan Quds Razavi, and poor Jadidi families received financial support from the Imam Reza shrine.Footnote 53 Mashhadi Jewish life thus was closely intertwined with the central authorities of the city, to a degree of mutual support. Many Jadids had good relations with the local governors, buttressing their position as trusted and influential members of the religious and political establishment in Mashhad.Footnote 54

When these elements come up in community history, they tend to be framed as pretense, actions taken for the sole purpose of protecting the community. The proximity of Jadidi and Muslim lives, however, also was evident in the spatial configuration of the former Jewish quarter, the Eid Gah: central buildings such as one of the former synagogues, the bathhouse, the bank run by Jadids (now demolished), as well as a famous shopping arcade (Saray Azizollahoff) were all in the immediate vicinity of the shrine of Imam Reza.

Although particularly the first generations of Jadids experienced strong pressure to hide their Jewish identity, many over time integrated into the wider Persian society and in this process were able to acquire considerable social standing. Practices of private and public religiosity varied accordingly. For about thirty years after the conversion, Jewish practice in general was almost nonexistent. Ephraim Neumark, who was in Mashhad about forty-five years after the Allahdad, writes:

Those who remained slowly forgot the religion of their forefathers, except a very few that withdrew from the ways of the world and isolated themselves in their homes where they could do as they pleased. Under these circumstances thirty years passed by, but during the last fifteen years the spirit of G-d began to awaken in the souls of the children of the notable personages.Footnote 55

From the 1870s onward, groups of individuals resumed Jewish practices, starting to celebrate Shabbat, Passover, and Yom Kippur. However, it is rather unlikely that from one day to the next “the community was united and faithful to its secret religion,” the revitalization of Jewish traditions began small, with improvisation, and expanded to more people over time.Footnote 56

The imposition of Islam as an alien practice held true for part the Jewish community, but the Mashhadis consisted of various groups. Those known as the Talebin al-Islam, or students of Islam, who had fostered close connections with Muslims before the Allahdad, advocated conversion. They took Muslim names, went to the mosque frequently, and traveled on pilgrimage to Mecca, some stopping in Jerusalem or Karbala on the way back.Footnote 57 They would invite Shiʿi dignitaries into their homes for celebrations. Yaghoub Dilmanian writes that other groups among the Jewish community “mistrusted them and considered them less observant,” pointing to considerable diversity within.

According to Sara Koplik, the Jews who remained in Mashhad after the conversion were the more wealthy members of the community. They were more prone to assimilate to their Muslim environment for pragmatic reasons, lack of piety, or genuine acceptance of Islam. The second group, the Mitasebin (sic), the “dissenters” or “zealous ones,” who performed the minimum of Islamic rituals necessary to avoid the suspicion of their Muslim neighbors, were poorer and very devout.Footnote 58 Dilmanian ascribes their poverty to the fact that they refused any interaction with the Muslim environment. In addition to the “zealots” and the aforementioned “advocates” (Talebin), he introduces a third group of “moderates,” who actually were the majority and chose a middle way between wholehearted conversion and opposition to it. As they were “more or less inactive in the social sense,” Dilmanian does not elaborate on them in his book. He states that the zealots eventually prevailed.Footnote 59 Although many Jadids actively participated in Mashhad's daily public life, purchasing and donating land, building communal spaces such as a tekkieh (a theater for Islamic passion plays) or a water reservoir, the zealots opposed these actions to a degree that they isolated themselves from the rest of the community and “for 30 years would not even marry with them.”Footnote 60 This nucleus of people was adamant in drawing a line between what they strictly understood as Jewish and all other identities, including other Jadids. I will return to the role of the zealots again toward the end of this paper.

There were different responses to the forced conversion, resulting in various blends of a public Muslim and a private Jewish identity. One should read the following examples of Mashhadi practices with the above differences in mind, rather than assume that all members of one homogenous community employed them equally.

Underground Religion

Histories of the community during their time as converts describe practices such as observing Passover shortly before or after its assigned date, or eating only rice for the entire holiday. Some of these customs disappeared over time, whereas other customs, such as lighting Hanukkah candles separately instead of on a menorah, endured longer.Footnote 61

Regarding dietary laws, many stories relate that the Jadids bought meat from local (non-kosher) stores to avoid appearing suspicious in the eyes of their neighbors. Then they gave the meat to the poor or fed it to the dogs, clearly something only the well-to-do could afford. After some time, the men of the community learned the practice of ritual slaughter and distributed the kosher meat to family and friends. There also are accounts of accusations against the Jadids for not eating the same food as Muslims and not working on Shabbat, which allegedly proved that they were not real Muslims.

Usually, periods of social and political conflict brought about these accusations of tainted religiosity. In the year 1900, for example, there was a famine in Mashhad and food prices were very high. Some people accused the Jadids of hoarding wheat and other foodstuffs in their cellars, while “we were starving to death.”Footnote 62 The incited people then attacked the “bakeries which belonged to Muslims” and the house of the biggest landowner of the city (a Muslim). Before they reached the Jewish houses, “a grocer called Mirza Davood” was able to stop the rioters; later the authorities also sent soldiers to contain the riot.Footnote 63 This episode shows that the looters were motivated by socioeconomic disparities, which led them to attack wealthy Muslims and Jews alike.

Other popular stories relate to the difficulties of keeping the Shabbat while staying open for business.Footnote 64 There were varieties of ways used to avert customers: asking for unreasonably high prices or sending young boys to the shops, who would tell potential customers to come back another day because the owner was not there. Surely, the Muslims understood that the Jadids did not engage in business because of Shabbat. There also were individuals who wanted to keep their businesses open and did not share the commandment of Shabbat as a day of rest. One of my interview partners told me that the Mashhadis had a group of elders who controlled adherence to Jewish laws and punished individuals for violations. He related that this also could include beatings, repeated until the person complied. A distinct community structure had evolved, resembling other crypto-Jewish communities such as the Dönme.Footnote 65

The Jadids had their own neighborhood, cemetery, and bathhouses. Among themselves, the converts referred to their community as Jadids, too: “When my parents talked about ‘the Jews’ they always meant other people. We were Jadids.”Footnote 66 They were a distinct community due to the evolution of their identities and practices, and although they had close ties to both Muslim and Jewish communities they somehow remained apart.

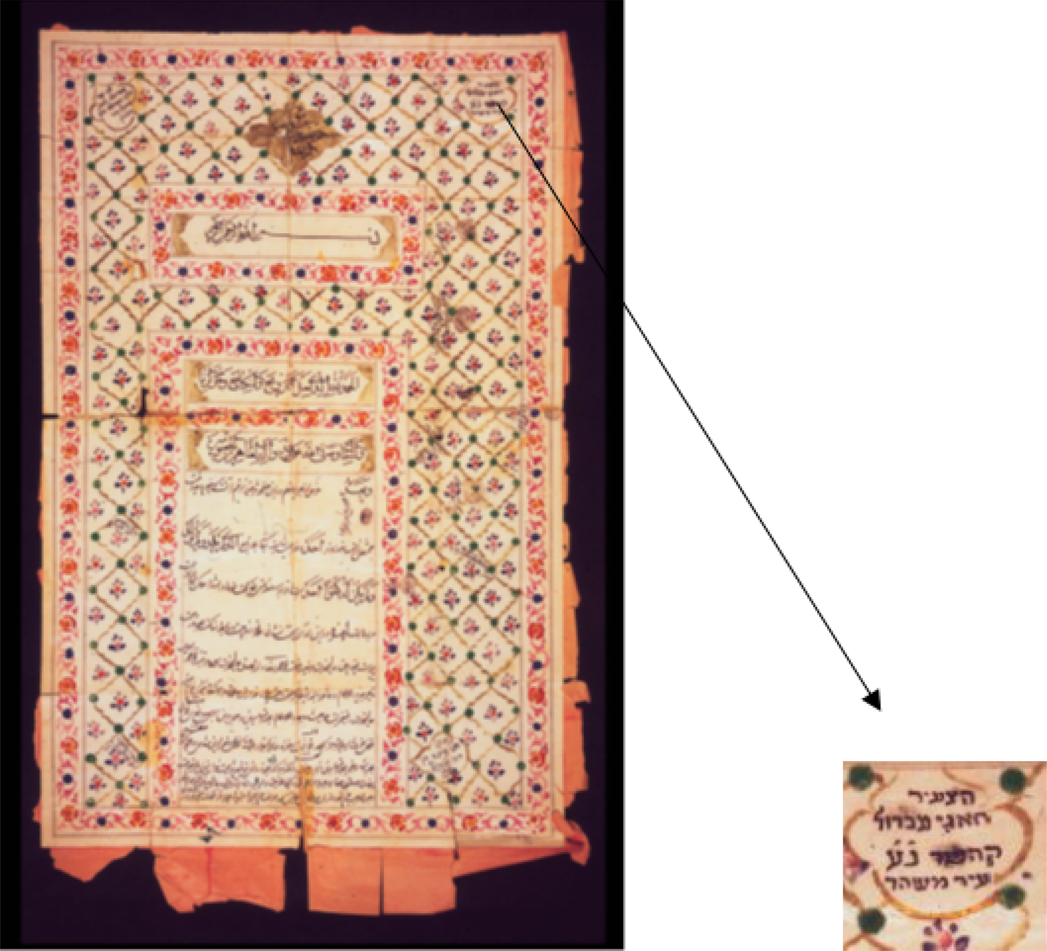

The marriage contracts of the Jadid al-Islam further illustrate the difficulty of drawing clear borders between Muslim and Jewish identities (Fig. 3). The Muslim marriage contract, the ʿaqd nāmah, begins with Qur'anic verses and prayers. However, this tradition was not limited to Muslim families. There are several examples of Jewish marriage contracts with the incorporation of Arabic, Hebrew, and Aramaic as the holy languages of the contract, or the sole use of Qur'anic lines in addition to the Persian text.Footnote 67 The Mashhadis had Muslim wedding contracts in addition to a Jewish one for private use. Some marriage contracts had two identical pages, one in Hebrew and Aramaic and the other in Arabic and Persian. Shalom Sabar discusses a typical Shiʿi ʿaqd nāmah, where the appellation Jadid al-Islam stands next to the names of the bridegroom, the bride, and their parents. Like many Iranian Jews, Jadids usually bore two names, a typical Muslim name and a Jewish name used only by members of the community. However, on some marriage contracts of the Jadids, Jewish names do appear:

The witnesses required to sign these contracts would often write their Jewish names in cursive Hebrew script instead of Arabic. These signatures were written in such minuscule cursive handwriting that obviously only members of the community could decipher them. In fact, if a Muslim asked the Jadidim for the meaning of their peculiar writing, they would usually answer that it was a secret script inherited from their fathers.Footnote 68

Rather than acknowledging the simultaneity of Hebrew and Persian elements in the marriage contract that pointed to a multilayered identity, Sabar incorporated this example into the dichotomy of secrecy and public deceit. It is unlikely that the Muslims of Mashhad were unable to detect that “the script of the forefathers” was Hebrew.Footnote 69

Figure 3. Marriage Contract from Mashhad, 1869 (Source: National Library of Israel)

Sabar elucidates the character of the decorations and the selection of motifs and designs in the marriage contracts of the Jadids, which changed dramatically in the period after the forced conversion. Instead of the characteristic Jewish elements, the decoration resembled typical designs of Shiʿi marriage contracts. Toward the end of the 19th century, when a small book-form marriage contract became the norm, the Jadids immediately adopted it for both types of marriage contracts, Jewish and Muslim. Rather than upholding a strict public-versus-private identity, the marriage contracts illustrate how closely the Jadids were intertwined with Persian culture.Footnote 70

Constriction and Continuity

At the turn of the 20th century, those who had advocated conversion to Islam had either merged with the majority Shiʿi society or left Mashhad. Leadership of the Jadidi community shifted to the “zealots.” Dilmanian states: “Any advocates of Islam found it necessary to put aside differences of opinion and join the others. Whenever they faced trouble they always united, and everyone was brought closer to the ancestral faith.”Footnote 71

Dilmanian mentions that in 1856 the first copies of a Persian Bible translation arrived in Mashhad, prepared by the Christian Bible society in London. He suggests that this was an important factor in strengthening Jewish identity. After the Constitutional Revolution of Iran (1906–11), the government established public schools in Mashhad and the Jadids used this development to request their own school. The school did not differ in its curriculum from other schools, and included Qur'an lessons and prayers. In addition to public school, over time more Jadidi boys attended the beit midrash, where they studied Hebrew and received religious instruction.Footnote 72 In this way the period saw the manifestation of more institutionalized Jewish practice.

In the course of time, some of the Jadids became Muslims, without a trace of their Jewish roots remaining. Others became pious Muslims, but retained elements of Jewish religion and culture at home. They considered themselves true believers of Islam, but their practice was syncretic. Those who chose a Jewish identity engaged in the production of a new communal identity.Footnote 73

From the 1920s onward, when Reza Shah Pahlavi (r. 1925–41) came to power, the Mashhadis practiced Judaism more openly. In 1933, the Jadids amounted to 3,000 people and had several synagogues. After 1941, when Reza Shah was deposed, prohibitions against political activism such as Zionism initially loosened. This led to new forms of contact between the Mashhadi Jews and Jews in Palestine, mainly mediated by the Jewish Agency office that had opened in Tehran in 1942.

Many Mashhadi memoirs from the 1940s refer to a happy childhood, especially in connection with increasing prosperity. There are references to big mansions with (Muslim) housekeepers. Some Jadidi families were among the first who owned a car or a telephone in all of Mashhad. Jadidi children went to school with Muslim children, who were their friends. They accompanied their parents to synagogue and went to the bathhouse every Friday that they shared with the local Muslims.Footnote 74

From 1941–46, the Russian army occupied Mashhad. When the army left the city, crowds from the street attacked the Jewish neighborhood despite attempts of civil and religious officials to protect the Jadids. This event prompted a visit by a representative of the Jewish Agency for Palestine from Tehran who called for the “rescue of our brethren,” in the form of their emigration to Palestine.

The diminishing economic opportunities after the war also spurred the emigration of Mashhadis, mainly to Tehran. In 1953, there were about one hundred Jewish families in Mashhad, and the last individuals left in the late 1990s. Today the largest communities of Mashhadis live in Israel and in Great Neck, New York, with some smaller offshoots in the United Kingdom and Italy. Altogether, the community comprises about 20,000 individuals, and they maintain close connections across borders.Footnote 75

According to Dilmanian's proposition that the zealots shaped the self-understanding of Mashhadis from the 1900s onward, they provided strong exclusive identifications and boundaries for the community, which over time aligned their history with the tenets of normative Judaism and exclusive belonging as encapsulated in modern nationalism. Dalia Kandiyoti has pointed out that the desire to recuperate buried histories of crypto-Jewish communities can be both productive and problematic. Their productivity lies in the potential of personal narratives to assert what hegemonic religious, political, and economic powers have long suppressed. At the same time, there is the possibility of essentializing identities “by reaching back to supposedly authentic and fixed definitions, including those interpretations in which certain looks, behaviors, talents, and choices are marked as ‘Jewish’ and serve as evidence.”Footnote 76

Conclusion

Muslim and Jewish identifications in 19th-century Iran could be complementary rather than antagonistic. Categorizations as distinctly Muslim or Jewish do not reflect the array of practices, beliefs, and affiliations that the Mashhadis employed. By pointing out these convergences, I hope it has become clear that this article is not interested in determining whether the Mashhadis were or were not “real” Jews. The interest rather lies in the question of how it came about that their particular way of being Jewish, including its manifold and at times indeterminate expressions, was channelled into a contemporary narrative in which hardly any of these variations and interlinkages have a place.

A reading in which categories of religious belonging need not be oppositional but rather articulated with each other, supplementing and engendering each other, entails some Mashhadis who may not have made a clear distinction between what they privately believed in and what they practiced publicly. This is not to say that what one believed or how one identified was meaningless. Rather, there was considerable diversity among the Jadids regarding the extent to which they accepted Islam or opposed conversion. The respective practices transformed over time, rather than representing a singular and invariable Judaism. It was thus not the act of conversion itself that created the communal boundary, but the continual transmission of its narrative.

Imposing a historical trajectory of Jewish exclusivity on heterogeneous and interrelated cultural practices is a product of processes internal to various Jewish contexts but also of the wider world's discourses on equality and civilization, in which figures who build lives, identities, and communities by hiding, mixing, masquerading, and moving have no place.Footnote 77 When we look beyond the narrow confines of these boundaries, a wide field of known and unknown ties between Jewish history and other histories emerges.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Mehrdad Amanat, Shervin Farridnejad and Florian Schwarz for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper.