Published in 1947 with the title From Dardanelles to Palestine: A True Story of Five Battlefronts of Turkey and Her Allies and a Harem Romance, Sarkis Torossian's memoir provides the portrait of an empire on its last gasp. In the book, which the author claims was based on true events, Torossian recounts his story of disillusionment with the ideology of Ottomanism during and following his service as an Armenian officer in the sultan's army as the Great War waged on. His narrative describes how the pride at being decorated by Enver Pasha for his military prowess dissolves into despair and rage at seeing the annihilation of the empire's Armenian population.Footnote 1 The publication of the Turkish translation of Torossian's memoir in 2012 set off a fierce dispute over the authenticity of the text, deepened by occasional ad hominem exchanges between several Ottoman historians.Footnote 2 If the controversy surrounding the memoir revealed how a historical debate could quickly devolve into a polemic, it also proved a scholarly boon by stimulating research on the experiences of non-Muslims with the military draft in the Ottoman Empire. Out of an academic quarrel was born an interest in writing unspoken stories of Ottoman peoples and military conscription into history.Footnote 3

Prior to the Turkish publication of Torossian's memoir, the conscription of non-Muslims in the late Ottoman Empire had attracted scant scholarly attention. And within that barren field of studies regarding their conscription into the Ottoman army, the emphasis has been on the alleged aversion of non-Muslims to donning the uniform, an approach that served to indict the policy of Ottomanism at the turn of the 20th century as a project doomed to failure from the outset. One of the most comprehensive works on this topic ends on a note indicative of the established paradigm in Ottoman historiography. Although it acknowledges Christian and Jewish soldiers who fought tooth and nail in the Balkan Wars (1912–13), its concluding paragraph suggests that, in general, they were better at dodging the draft than fighting valiantly.Footnote 4 A detailed monograph on the relations between the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) and Greek Ottomans offers an even more sweeping conclusion on the matter. Based on several contemporary accounts, the author argues that “especially during the Balkan Wars, not only did Christian soldiers lack emotional attachment to the Ottoman army, but they felt joy at its defeat.”Footnote 5 If desertion is employed as the tool for gauging Ottoman-ness, historical data hardly allow for a ranking of patriotism by ethno-religious groups. By the end of World War I, the number of deserters from the Ottoman army had totaled about half a million, three times more than the number of deserters from the larger German army. Whereas the rate of desertion in European armies during the war stood between 0.7 and 1 percent of the mobilized manpower, the Ottoman armies recorded a rate at least twenty times higher.Footnote 6 In the absence of information about deserters by religious category, the exact number of non-Muslim fugitives eludes us. Nevertheless, given that Muslim soldiers comprised the large majority of Ottoman manpower, they likely represented a significant portion of the army of deserters. Moreover, it is documented that desertion posed one of the most pressing challenges to the Turkish independence movement in Anatolia after World War I, a fight waged by Muslim soldiers. In his address to the Turkish national assembly in July 1920, Vehbi Bey, a representative from Konya, acknowledged the problem: “The desertions in the army, all of our friends know about it. They put two hundred men on a train in Konya, but only thirty arrive in Karahisar. A column of three hundred soldiers is down to a hundred and fifty, three days later.”Footnote 7

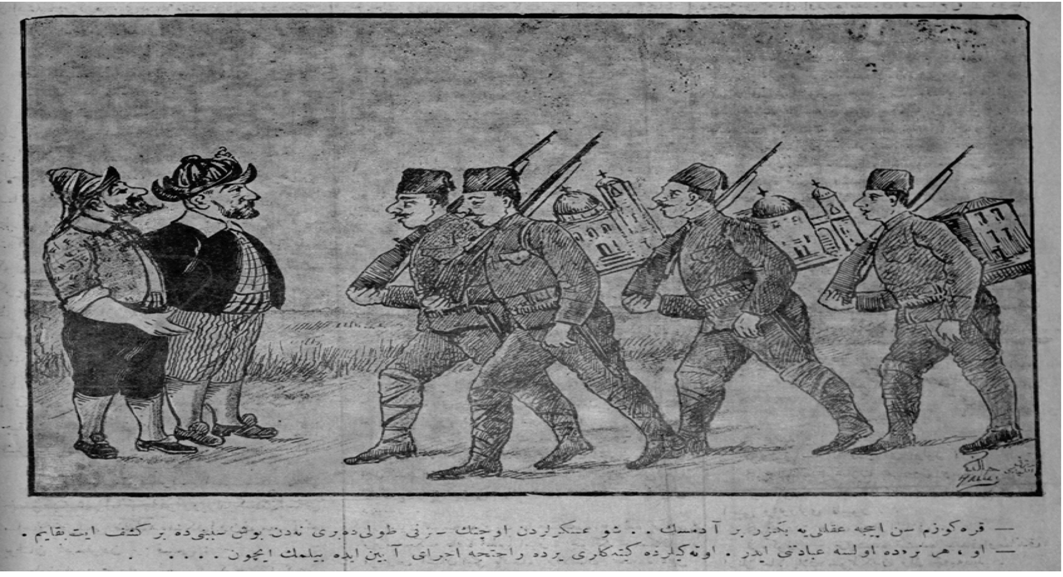

This article deals with the incorporation of non-Muslims into the Ottoman army with a focus on the empire's largest non-Muslim population, the Greek Orthodox. When the law regarding the conscription of non-Muslims was issued in the official gazette Takvim-i Vekayi (Calendar of Events) on 11 August 1909, it abolished the old practice of bedel, a lump sum tax levied on non-Muslims in return for their exemption from the military service. The law specified the establishment of local commissions to carry out the physical examination of the newly recruited in the presence of their religious representatives.Footnote 8 During the two years that followed the issuance of the new law, heated discussions about the implementation and length of service continued in the Ottoman parliament and press (Fig. 1). Before examining the enthusiasm and anxiety that the draft generated for Greek Ottomans, a few remarks are in order to highlight the significance of studying Ottoman history through the relocation of frequently marginalized non-Muslim populations into the center of analysis.

Figure 1. Front page of the magazine Servet-i Fünun (Wealth of Sciences) showing the recruitment of soldiers in Istanbul. From 17 March 1910 issue, Atatürk Library of Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality.

As Ayşe Ozil indicates in her observations relating to Ottoman historiography, Greeks of the Ottoman Empire are “conveniently positioned among the non-Muslims of the empire, who have been regarded as marginal to a supposedly real, i.e., Muslim, Ottoman history or viewed under a negative light. They are defined according to what they were not, i.e., non-Muslims, rather than what they were.”Footnote 9 Whereas Ozil critiques this approach through a multilayered analysis of the Greek Orthodox population during the late Ottoman period, Christine Philliou intervenes to address the same question through an examination of the impressive career of Stephanos Vogorides in the upper echelons of Ottoman administration during the first half of the 19th century. Like Ozil's, Philliou's account offers a powerful corrective to viewing the Ottomans as a Turkish and Muslim empire with other populations being relegated to the margins of state and society. Philliou argues that “Vogorides, precisely because he was a Christian, has confounded students of Ottoman history who would expect him to be nationalist and therefore disloyal to the Ottoman sultan.”Footnote 10 For the period under examination in this article, the aftermath of the Constitutional Revolution (1908), Michelle Campos engages with this pervasive and ingrained narrative in Ottoman history by demonstrating the appeal of Ottomanism to Jews and Christians, in addition to Muslims, in Ottoman Palestine. She scrutinizes Ottomanism not solely as a discursive program created and propagated by the state and party elite but rather as a grassroots-level vision shaped by the inhabitants of Palestine. Through what she has labeled as the project of “civic Ottomanism,” people of Palestine developed new meanings of imperial citizenship that aligned with their distinct needs. Campos is attentive to tensions inherent in the process of crafting a unifying imperial identity in the face of attempts by diverse populations to preserve their linguistic, cultural, and ethno-religious autonomy: “And yet, making imperial citizens out of such a heterogenous population spread out over three continents was not an uncontested process; among the significant challenges of the Ottoman imperial citizenship project were the divergent, indeed sometimes opposed, meanings that it had for the empire's population.”Footnote 11

Accordingly, in this article I highlight various Greek Ottoman voices emanating from the Ottoman capital in the context of debates on the incorporation of non-Muslims into the army following the Constitutional Revolution. If the postrevolutionary regime's introduction of universal conscription can be read as a statement that every Ottoman male was now equal, the examination of Greek Ottoman voices regarding its implementation bears out their distinct visions of equality, frequently in conflict with those held by the CUP, arguably the most powerful political organization in the empire. During the conscription debates, Greek Ottoman deputies in the parliament and opinion makers in the Greek-language press championed the principle of military service inclusive of all Ottomans, irrespective of religion. What drove a wedge between them and the CUP, however, was their insistence on the formation of separate battalions for Greek soldiers. The promise of equality in duties that Greek Ottomans saw in the draft was marred by their suspicion that the CUP sought to use conscription as a tool of assimilation. They proposed the formation of separate battalions for Greek conscripts as a shield against the accomplishment of such a goal. Although the CUP rejected this demand and all conscripts eventually served in mixed-religion battalions, a glimpse into the proposals of the Greek Ottomans reveals alternative interpretations of Ottomanism at a time of fierce debates about what it meant to be an Ottoman citizen.

My usage of Greek Ottoman throughout this article instead of the standard Ottoman Greek necessitates a short explanation.Footnote 12 This construct is akin to the widely accepted labels such as Greek American, in which an ethnic epithet qualifies a political relationship. My usage is informed by the nature of the proposed separate battalions in the postrevolutionary Ottoman context and, as such, closely links with the main premise of this article. I argue that the placement of the ethnic descriptor first serves to spotlight the primacy of Greekness in the hybrid imperial identity, a perspective that was underlined by Greek Ottoman opinion makers in the speeches from the podium of the parliament and the pulpits of churches and in the texts from the columns of newspapers. A vocal segment of the Greek Ottoman population viewed the formation of battalions based on ethnicity as a measure that would safeguard the characteristics deemed to define the contours of their community. If the conscription into the army allowed young Greek males to perform their Ottoman-ness and in the process affirmed their belonging to a political community, the fulfilment of that duty in separate units was envisioned to ensure the preservation of their Greekness.

Conceiving Ottoman Brothers-in-arms

Although universal conscription debates date back at least to the early Tanzimat years, never before the Constitutional Revolution in 1908 did they permeate the Ottoman public sphere so completely. Seeking to enact the deeper integration of Ottoman non-Muslims into imperial institutions, Tanzimat reformers had taken up the issue of universal draft with the Hatt-ı Hümayun of 1856. As the first official document that explicitly mentioned the enlistment of non-Muslims in the army, it deployed the language of equality in rights and duties. Speaking of universal conscription as an ideal that needed to be written into law “with as little delay as possible,” it introduced the option of paying the bedel as a tax of exemption until the passing of relevant legislation.Footnote 13

In 1865 a commission convened to deliberate on the matter. Among the commission's members was Ahmed Cevdet Pasha, whose opposition, on practical grounds, to a multi-confessional army prevailed over his otherwise sympathetic attitude toward the project. Ahmed Cevdet's line of argument culminated with a rhetorical question:

If we mix Muslim and non-Muslim soldiers in the army, we would be obliged to employ priests in addition to imams in a battalion. Perhaps this would be an easier matter if it concerned only one group of non-Muslims. However, in our country, there are all kinds of non-Muslim denominations. . . . All these communities would demand their own priests while Jews would request rabbis. . . . Similar to Muslims fasting during the holy month of Ramadan, non-Muslims observe multiple fasting days. Would it be possible to manage such a motley composition (mahlut bir heyet)?Footnote 14

Accordingly, new regulations on military recruitment that came into effect in 1870 maintained military service as a duty to be performed solely by Muslims. The first article of the recruitment law stated that “all of the Muslim population of the well-protected domains of His Majesty are personally obliged to fulfil the military service which is incumbent on them.”Footnote 15 Comparable perspectives holding sway during the 1870s partly explain why the first Ottoman constitution (1876) overlooked the issue of universal conscription, although the Hatt-ı Hümayun had made an explicit reference to it twenty years earlier. During the process of formulating the constitution, Midhat Pasha favored the explicit mention of conscription as a duty for all Ottomans, a position rejected by the majority of the drafting commission members.Footnote 16

Despite this omission, debates in the first Ottoman parliament at the time of war with Russia (1877–78) demonstrate that the principle of universal conscription resonated with many Ottomans. At a parliamentary session on 2 June 1877, Vasilakis Seragiotis Bey, a Greek Ottoman deputy from Istanbul, proposed abolishing the tax of exemption from the draft and making military service compulsory for non-Muslims. “If the constitution made everyone equal in rights and duties,” asked Vasilakis Bey, “then why is only a portion of our people deemed apt for the most sacred duty of shedding blood for the country while others just buy off their exemption from this noble duty?”Footnote 17 Unfortunately for Vasilakis Bey, during the next session Ahmed Muhtar Efendi motioned against the elimination of the bedel and urged non-Muslims to assist the army by forming volunteer corps instead.Footnote 18 In his classic monograph on the first Ottoman parliament, Robert Devereux likened Vasilakis's plea to “a voice crying in the wilderness” due to the little support he received from his fellow deputies.Footnote 19 Those opposing the proposal of drafting non-Muslims often invoked economic considerations by arguing that the bedel provided the state with a crucial source of revenue, particularly needed during a costly war with Russia. At the time of these discussions, the military exemption tax comprised 3.4 percent of state revenues.Footnote 20

Speaking at the commencement of the parliament's second year in late 1877, Abdülhamid II thanked his non-Muslim subjects for their spirited patriotism and concluded that the enlistment of non-Muslims constituted one of the objectives of his reformist administration. The deputies echoed the sultan's message and promised that they would eagerly pursue the matter.Footnote 21 During the parliamentary session on 3 January 1878, Zafirakis Efendi, a Greek Ottoman deputy representing the Archipelago province (Cezair-i Bahr-i Sefid), exclaimed that “non-Muslims have long wanted and demanded to be conscripted, but whether it would be beneficial to the state to include in the army, at this time of economic hardship, people who have, for centuries, been unaccustomed to carrying arms and lacking in experience with army life is a matter that requires careful analysis.” Invoking the biblical creation of earth in six days, Zafirakis cautioned against hasty policies and recommended a gradual approach to the conscription of non-Muslims.Footnote 22 Such lively debates in the parliament came to an end when Abdülhamid II suspended the constitution and dissolved the parliament in February 1878. After the dust of the war with Russia settled, a military commission reconsidered, away from the public eye, the matter of conscription of non-Muslims. The commission's favorable recommendation, however, produced no concrete results in terms of policy.Footnote 23

Animated discussions about the military service resurfaced through the cracks that the Constitutional Revolution of July 1908 opened in the edifice of censorship erected by the Hamidian regime. An atmosphere of euphoria throughout the Ottoman Empire characterized the postrevolutionary moment with people from all walks of life and religious backgrounds fraternizing in the festive streets. Open-air festivities presented novel expressions of political belonging, a point aptly illustrated by Bedross Der Matossian, who identifies in such a setting “the beginnings of the public sphere that emerged from the Revolution that employed both local print culture and local ritual in a way that allowed the new nation's varied ethnic and religious groups to participate in—and incrementally define—the culture of the new Ottoman nation.”Footnote 24 If the spirit of uhuvvet (fraternity) permeated street celebrations sparked by the restored constitution, the notion also commanded a ubiquitous textual presence in the burgeoning press. The newspapers saluting the advent of a promising epoch of liberty and equality drew a link between uhuvvet and conscription: what better method to achieve uhuvvet than through the creation of a multi-confessional community of Ottoman brothers-in-arms? The political program published by the CUP linked uhuvvet to constitutional rights and duties: “Without distinction of ethnicity and religion, every Ottoman will be provided with complete equality, liberty, and identical obligations. . . . Hence, the conscription law will apply to non-Muslims as well.”Footnote 25

In August 1908, a piece in the staunchly pro-CUP daily Tanin (Echo) summarized the symbolic significance of universal draft:

All citizens, regardless of ethno-confessional differences, are now entitled to reap the benefits of the development and prosperity of our common motherland. Similarly, safeguarding its internal security and guarding its borders also are their common duty. Exempting from the defense of the country some citizens, who are in all other matters subject to the same laws as their compatriots, suggests that their bond with the motherland is weak and tenuous . . . enmity and hatred between the empire's diverse populations can only be eradicated if Ahmed and Hüseyin eat from the same cauldron and sleep in the same dormitory as Artin and Dimitri.

Anticipating objections to a multi-confessional army on the grounds of preserving the Ottoman army's exclusively Muslim character, the author invoked early Islamic history by noting that, in the Battle of Hunayn against the Bedouin tribe of Hawazin in 630, Prophet Muhammad recruited 2,000 non-Muslim soldiers.Footnote 26

“Against Equality”

When the promulgation of the constitution catapulted the question of the military service of non-Muslims into the Ottoman public sphere, a joint statement by the editors of eleven Greek Ottoman newspapers asserted that the Ottoman people had been divided for ages into two opposing camps of “masters and subjects, best characterized by the label of Muslim vs. non-Muslim.” The leading figures of the Greek Ottoman press expressed hope that the new regime would dismantle such age-old divisions.Footnote 27 A similar expectation was borne out by the observations of Athanasios Souliotis, who, as the founder of the Society of Constantinople (Organōsis Kōnstantinoupoleōs), worked closely with most Greek Ottoman deputies in the parliament that functioned between late 1908 and early 1912.Footnote 28 He wrote that the proclamation of the constitution portended a promising future for Greek Ottomans:

The nations of the Balkan Peninsula and Asia Minor share so many similarities with each other, even though our fanatical upbringing and education have conditioned us to believe otherwise. . . . The new regime presented an opportunity. The declaration of the constitution generated a brotherly atmosphere among Turkey's nations, that is, all the nations of the East, [leading to a belief] that constitutional liberties would strengthen the Hellenism in Turkey to determine and follow a political program whose ultimate aim would be the cooperation among the states and nations in the East.Footnote 29

Such a belief also suggested that Greek Ottomans could finally channel their economic power into increasing their influence in imperial politics.

What raised the hopes of Greek Ottomans caused anxiety to many CUP members. In the run-up to the parliamentary elections in late 1908, the question of proportional representation brought to the surface such concerns. Hüseyin Cahid, as the editor of Tanin and soon-to-be deputy for Istanbul, emerged as the most vocal opponent of the Greek Ottomans’ demand for parliamentary representation proportional to their numbers in the empire. In a scathing editorial titled “Millet-i Hakime” (The Dominant Nation), Cahid remarked that the CUP vowed to uphold the principal of equality between Muslims and non-Muslims, yet asked: Does the provision for equal rights for non-Muslims mean that the Ottoman country will eventually become a Greek or an Armenian country?

No, this country will become a Turkish country. We will all unite under the banner of Ottoman-ness, though the structure of the state will never change at the expense of the special interests of the Turkish nation. And no action will be taken against the vital interests of the Muslim element. . . . Let us suppose that the Greeks hold a majority in the Ottoman parliament and the question of Crete's annexation to Greece comes on the agenda. I don't expect that many Greek deputies would challenge it. And some among them would even propose ceding territory around Ioannina to Greece.Footnote 30

Not every CUP member advocated for the dominance of the Turkish element in a multinational empire. Nevertheless, as the candid editor of one of the most influential CUP newspapers, Cahid likely expressed what more prudent Unionists preferred to keep private.

To many Greek Ottomans, Cahid's piece “Millet-i Hakime,” particularly the phrase “all uniting under the banner of Ottoman-ness,” concealed a Unionist desire to assimilate them. Underlining the impossible-to-achieve yet still perilous assimilationist policies, an editorial in the Greek Ottoman daily Proodos (Progress) argued that Greeks who withstood centuries of Roman rule and half a millennium of absolutism in the Ottoman Empire could never be assimilated under a regime of liberty.Footnote 31 Although Cahid mainly targeted Greek Ottoman newspapers and took a significantly more conciliatory stance toward Armenians, the position he represented had already drawn sharp criticism from the Armenian-language press as well. “Turkey for the Turks,” an article published by the Armenian-language Istanbul daily Jamanak (Time), dealt with the burning question of nationalities in the postrevolutionary context. Arguing that the CUP's attempt at weakening, even eliminating, the communal autonomy of Armenians and Greeks meant the denial of their difference, the article concluded: “We have not sacrificed hundreds of thousands for a constitution perceived that way. We have suffered for years, and if this is our achievement, we will also start looking for the old regime.”Footnote 32

During the conscription debates, Joachim III, the Greek Orthodox patriarch wielding considerable authority over his community, grew concerned about the potential hardships of life in the barracks for young Greek Orthodox men. His uneasiness pertained to various challenges that could arise as the conscripts practiced their faith in a mixed-religion army. In a column penned in response to Joachim III's repeated negotiations with state officials on the particularities of conscription, Hüseyin Cahid, the editor of Tanin, attacked what he saw as the patriarch's unacceptable intervention in army affairs. Viewing the patriarch as a meddlesome priest driving a hard bargain with the government over the specifics of military service, Cahid likened him to a customer haggling with a shop owner who sold only at fixed prices. Among the patriarch's demands were the prohibition of apostasy, employment of priests, assignment of places of worship, observation of fasting days, and formation of separate battalions for Christians. For Cahid, all but the last of these requests were legitimate. Whereas the first four qualified as spiritual matters that fell within the jurisdiction of the patriarchate, the formation of separate battalions did not. If the patriarch's argument made sense from a religious point of view, Cahid continued, then Russia, with its strict attachment to Orthodox Christianity, would refrain from enlisting Muslims in battalions mixed with Christians. Denying the patriarchate a say in nonspiritual matters overlapped with the CUP's goal of debilitating the previously widespread political influence of communal institutions.Footnote 33

Cahid's pen was stronger than his oratory, as he usually expressed his views on the matter through scathing editorials rather than from the parliament's podium. Pantelis Kosmidis, a Greek Ottoman parliamentarian representing Istanbul like Cahid, maintained no columns but owned a newspaper. In his Sada-i Millet (Voice of Nation ), with Ahmed Samim as editor until his assassination in 1910, a large number of articles treated the military service of non-Muslims differently than Tanin did. Specifically on the question of separate battalions, Sada-i Millet approvingly published excerpts from Neologos (New Logos), a Greek Ottoman daily from Istanbul. If Cahid and most Unionists viewed the formation of separate battalions for Muslims and non-Muslims as an obstacle to the union of Ottoman populations, Neologos thought that it constituted the true path to harmony. It argued that after centuries of separation, attempts to produce a quick union between Muslims and non-Muslims would backfire and create tension: “Desired results will not materialize through the creation of a haphazard mix in the same place between those who, by virtue of their deep ignorance, do not consider themselves bound to respect others’ religion and customs but, on the contrary, hold the mistaken belief that offending others’ religious sentiments is an obligation.”Footnote 34 In another article, also quoted by Sada-i Millet, the weekly Ekklēsiastikē Alētheia (Ecclesiastical Truth), the mouthpiece of the patriarchate, examined the question of separate battalions from a historical perspective. The piece mentioned Selim I's Egyptian Campaign in 1517, during which Greek soldiers fought under the command of a Peloponnesian Greek in separate battalions. Preceding this example was Mehmed II's tasking a Greek with the defense of the island of Imros in 1456. Later in the 18th century, during the reign of Abdülhamid I, a Greek named Nikolas Mavrogiannis enlisted Christian soldiers from Moldavia in distinct battalions and fought bravely against the Russians. The Ekklēsiastikē Alētheia article concluded by underlining the significance of such examples of separate battalions. The Greek-language weekly strove for the preservation of the long tradition of privileges granted to Christians as far back as the time of Caliph ‘Umar and respected by all Ottoman sultans.Footnote 35

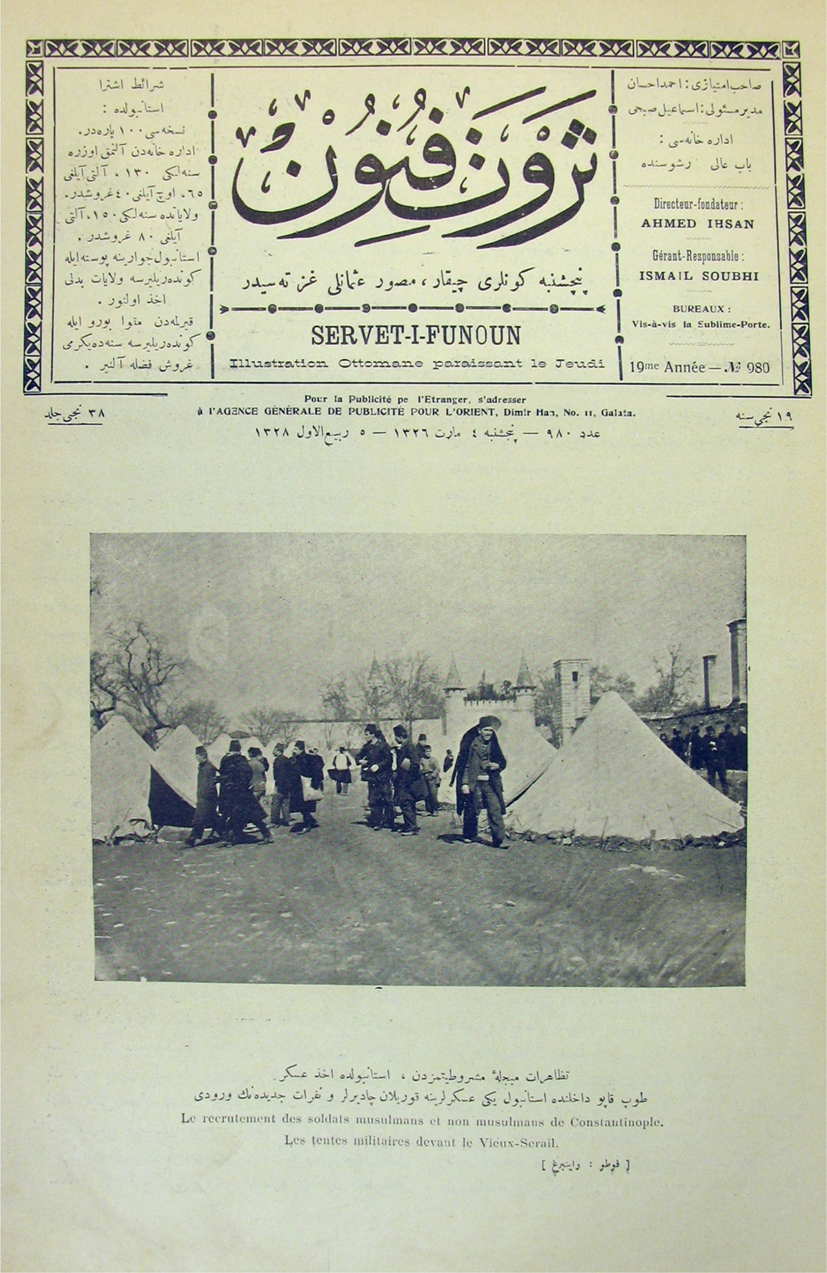

In addition to informing its readers of the meetings between the government and the patriarchate, Tanin published reports about appeals of the Greek Ottomans to the patriarchate in conscription-related matters. The tone of Tanin's reporting throughout was highly critical of the patriarchate, an institution whose pleas for active involvement in the drafting of military laws and regulations were rejected by the Unionist daily. In April 1910, Tanin published the request by around five hundred Greek Ottomans who begged the patriarch to petition the government regarding several issues, among them the shortening of military service and making Sunday a holiday for Christians. The newspaper found this appeal rather odd given the principles of hierarchy within the army that tolerated no outside interference, even by the Sublime Porte, let alone the patriarchate.Footnote 36 In response to Tanin, Ekklēsiastikē Alētheia acknowledged that the army's internal logic of operation should command everyone's respect. Nevertheless, it insisted on the legitimacy of such requests, necessitated by the creation of a multi-confessional army with such speed that it left no time for new conscripts to settle their various obligations prior to their enlistment. Underlining the novelty of conscription, Ekklēsiastikē Alētheia assured Tanin that the patriarchate's sole aim was to help Greek Orthodox soldiers observe their spiritual duties in the unfamiliar environment of mixed-religion barracks.Footnote 37 Although it is important to note that new regulations in September 1910 granted Greek Orthodox soldiers leave on Sundays in addition to the total of ten religious off-days annually, the critical attitude of the CUP-friendly press toward Greek Ottomans continued.Footnote 38 A cartoon that appeared in the satirical semiweekly Karagöz provided an illustration of Tanin's regularly negative commentary on the requests of Greek Ottomans regarding military service (Fig. 2). In the image, which caricatures all non-Muslim Ottomans as demanding characters, three conscripts representing Greeks, Armenians, and Jews are depicted carrying their places of worship on their shoulders whereas the Muslim, likely Turkish, soldier only bears a rifle.Footnote 39

Figure 2. —My dear Karagöz, you seem like a pretty smart guy. Tell me why three of these soldiers have loads on their backs while one doesn't.

—That one can worship anywhere. And the others have to [carry their temples] to conveniently perform their religious duties.

From Karagöz, 4 February 1911, Atatürk Library of Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality

Whereas the tenor of Tanin's reporting rendered many Greek Ottomans as obstinate objectors to conscription, Sada-i Millet sought to rectify such perceptions by publishing pieces conveying their eagerness for military service.Footnote 40Sada-i Millet targeted the readers in the Ottoman capital as its main audience, especially those unable to follow Greek-language newspapers due to linguistic limitations. The nature of Sada-i Millet's reporting on conscription perfectly matched its mission to “generate a genuine harmony between Ottoman populations, hitherto separated from one another by historical animosities, ethnic hatreds, and senseless enmities.”Footnote 41 Under no conditions would the newspaper neglect to publish the public address by Sofranios, the Greek Orthodox metropolitan of Ankara, in November 1909:

Fellow citizens!

Jubilantly we all listened to the communication of our sultan's imperial order regarding the conscription and we are prepared to obey it. History has shown us, with many examples, that conscription of non-Muslims is not something new. During auspicious reigns of our illustrious sultans, Christians were honored with military duty. . . . Since we are all children of this homeland, which is sacred to every one of us, it is only obvious that all Ottomans should be ready to sacrifice their lives for its defense.Footnote 42

On 14 March 1910, Sada-i Millet published the translation of the speech that Greek Orthodox patriarch Joachim III delivered to around two hundred conscripts following Sunday mass at the patriarchate:

My sons in the army!

I am proud of seeing you here, dressed in military uniform and performing your religious duty. . . . With your arms, not only will you defend this country but the principle of equality introduced by the constitution. Constitutional rule means equality among all citizens. . . . Keep in mind that beginnings are always the most difficult and you will certainly encounter hardships. But also rest assured that both the government and your spiritual center [the patriarchate] will strive to ensure you live in complete equality and harmony with your Muslim companions.

Several days later, the patriarch's speech in its Greek original appeared in the weekly Ekklēsiastikē Alētheia . It is critical to underline the differences between the original and translated texts in terms of the vocabulary used by Joachim III as he talked about the introduction of conscription to Christians in 1909. Perhaps more telling is Sada-i Millet's omission, in the Turkish translation, of the sentence that contained the phrase casting 15th-century Ottomans as foreign conquerors while privileging Greeks with the claim of historical ownership predating the Ottoman conquest: “[for the first time] since Ottomans conquered our fatherland” (Apo tou chronou tēs kataktēseōs, af’ otou oi othōmanoi katektēsan tēn patrida ēmōn). Footnote 43

The barracks offered no bed of roses to soldiers. The uncertainties associated with the novelty of conscription for non-Muslims aggravated for them the hardships of an experience already challenging for everyone. Neologos assumed the task of writing about the distress of conscription, occasionally publishing accounts of the mistreatment of Greek Ottoman soldiers by their Turkish officers. Predictably , Tanin and Sada-i Millet reacted differently to such reports. Whereas the former denied their authenticity and accused the paper's owner Stavros Voutiras of sowing enmity among Ottomans, the latter expressed sympathy for Christian soldiers and anticipated an end to unfortunate occurrences through the efforts of honest officers.Footnote 44 Indeed, Sada-i Millet went to great lengths to persuade its readers of the non-Muslim soldiers’ satisfaction with military service. It was letters from soldiers that would describe the draft as it really was. Although the use of letters and petitions poses methodological problems to historians related to authenticity, it is worthwhile to emphasize that such documents, despite their elusive character, shed light on journalistic strategies that shaped public opinion in the late Ottoman Empire. Although Tanin exhibited no strong interest in publishing letters that came from the barracks, Sada-i Millet provided numerous examples. One claimed to be written by a Greek Ottoman soldier serving in Istanbul to his friend in Salonica:

My brother Spyro,

We are always busy with performing drills and being present at the sultan's Friday Prayers. This Friday we had the honor to see His Imperial Majesty entering and leaving the mosque. Our barracks is an excellent building by the sea. . . . We sleep comfortably in our new beds, which arrived two days ago. . . . Our dining hall is in a separate building. Not all barracks are equipped with such perfect amenities. Fortune has smiled upon us.

Your brother Yorgi SandarosFootnote 45

Another example presented the details of the visit of a Greek Ottoman soldier to the office of Sada-i Millet where he conversed with the journalists about conscription. Specific information about the location of his military post and identification of an officer by name imbued this account with greater authenticity:

We get along with our Muslim companions like brothers. They treat us with full respect and help us immensely in our training. . . . We are allowed to attend Sunday Mass at church. Those coming from nearby were given permission to spend Easter at home with their families. In short, we are extremely happy with our condition in the barracks and the army in general. We have no complaints.Footnote 46

In stark contrast to such accounts, a letter that a soldier sent to the Greek Orthodox patriarchate spoke to the concerns of many anti-Unionist Greeks regarding conscription. Ekklēsiastikē Alētheia published it with the title “Against Equality”:

Your Holiness,

It is with my great sorrow to inform you that our situation has become unbearable due to violence and lawlessness. Because our officer, to our bad luck, is very fanatical and has despotic instincts. . . . On Sundays if we ever say that we want to go to church, they send us to church but, when they do, they lead us like sheep. We are aware that as soldiers we must respect the rules. But the rules are applied in a strange way and according to the will of certain individuals who are not accountable to anybody. They are like tyrants to us and harbor racial prejudices towards us. It is impossible to become like brothers as they say ‘We are all brothers’ [‘Hepimiz kardaşız’] since they are diametrically opposed to equality. What we write you falls short of communicating what we actually suffer. We do not know what holiday means. We do not know what prayer is. We do not know anything because they mock us if they see us crossing ourselves or if we do anything religious. Thus, we beg Your Holiness to show pity on us for the torture and violence we endure and to take necessary measures because our condition is unbearable. . . . We do not have permission to go to the market to buy what we need. Previously they would permit us to leave the barracks once a week, but we are not allowed anymore. They say the order was canceled by the commander of the troops. And he said that there would be no more permission, which, by the way, applies to us alone.Footnote 47

The writer of the letter claimed that he recounted not an isolated case but an instance that epitomized the condition of many soldiers.

Fight or Flight

In April 1910, around the time of the publication of these three accounts that claimed to speak to the agreeable or deplorable conditions of some soldiers, the Ottoman deputies were busy discussing a matter that concerned all soldiers: the length of conscription. Article 3 of the proposed conscription law had set the length of military service at three years. Many parliamentarians argued for a shorter term of service. Responding to demands for shortening the service to two years, the deputy for the Ministry of War claimed that two years, the length of military service in various European countries, would not be feasible in the Ottoman case. Citing the insufficient number of reserve officers in the army as the basis for his objection, he seemed to be in support of shorter service only after the completion of training of a reserve corps.Footnote 48 Pantelis Kosmidis, a Greek Ottoman deputy from Istanbul, pointed out that the conscription term could be shortened by reducing the amount of time devoted to training. Scoffing at Kosmidis's argument, the deputy representing the Ministry of War argued that even Germans lacked such military capability. Advancing an argument based on the comparison of German and Ottoman peasants, Kosmidis insisted on a shorter military term:

Germans cannot achieve it but Ottomans can. . . . When we compare our peasants with German peasants, we see a higher level of acumen in our peasants. I have absolutely no doubt that our peasants would excel at training more quickly. I am confident that our people are capable of receiving excellent military drill in the space of one year, hence my support for a two-year active duty . . . [this will] benefit the country in multiple ways by allowing young men to continue their civilian jobs rather than loiter in the barracks, especially in times of peace.Footnote 49

Mehmet Habib Bey, a deputy representing Bolu, argued that the insistence on shorter service evinced Kosmidis's ignorance of military matters. He pointed out that even an advanced country like Italy, with its extensive network of railways and infrastructural facilities, had only recently reduced the length of service to two years. Neither boasting a solid transportation network nor a homogeneous population, the Ottoman Empire was the antithesis of Italy. Given that many soldiers would lack a rudimentary knowledge of Turkish, the language of command in the army, he claimed that even the teaching of numbers for shooting drills would be an uphill battle. Discussions ended with the submission of a motion to reduce the conscription to two years. Thirty-seven signatures, of which sixteen belonged to Greek Ottoman deputies, fell short of the minimum number for approval.Footnote 50

A year and a half later, the length of military service was back on the parliamentary agenda. Although the debates in April 1910 centered on whether two years sufficed for the satisfactory training of conscripts, in October 1911 the deputies focused on the impact of longer service on the Ottoman economy and society. Georgios Boussios, one of the fiercest anti-Unionist Greek Ottoman deputies, addressed his fellow deputies in an impassioned fashion.Footnote 51 In the hope of persuading his Turkish colleagues, he focused on the detrimental impact of conscription on the Turkish population: “Speaking on behalf of all Ottomans, I declare that we Greek Ottomans need the Turkish element. Turks founded this state, but they are slowly dying away. If this state collapses, we Greek Ottomans will be losers too. Please preserve the Turkish element.” Responding to a deputy who pointed to Montenegro as an exemplary soldier nation, Boussios continued: “We cannot be like them. We want to live like civilized people. We exclaim that we are civilians first and then soldiers. But you proclaim the opposite.”Footnote 52

Boussios also claimed that the length of conscription instilled in Christians a profound fear, leaving many to regard immigration to America as the only escape. During the same session, Armenian Ottoman deputy Krikor Zohrab, in one of his characteristically articulate speeches, asserted:

We fail to understand what war really entails. We hold the mistaken notion that war means foreigners’ murderous incursions into our country through their armies. This is what we have reduced war to. We think that other types of attacks and violations are not belligerent but peaceful. Gentlemen, I will argue the opposite. I pronounce that all the violations that we deem peaceful, all the attacks that are carried out through commercial, industrial, and civilizational means constitute the real warfare. When you lose them, you can never win others. . . . Here I'm specifically addressing my dear Turkish companions. What causes concern to our Turkish companions in questions such as the election of deputies in proportion to population? It's the declining population of the Turkish element. Don't you consider waging a war against this condition? . . . According to a misconception, Turks lack the aptitude to succeed in trade and industry. I wholeheartedly disagree. Military service has reduced Turks to a sorry state by leaving them no time to devote to economic activities.

When Zohrab concluded his moving speech, even Mehmet Talat Bey, a staunch Unionist deputy from Ankara, was convinced of the merits of a shorter service.Footnote 53

Such views advanced by Boussios and Zohrab had previously appeared in Politikē Epitheōrēsis (Political Review ), an Istanbul-based newspaper in which several Greek Ottoman deputies regularly expressed their opinions. In April 1910, an anonymous editorial, likely penned by Boussios, discussed the conscription of non-Muslims at length, with particular focus on two perils, international and domestic, threatening the empire. The piece argued that the external danger stemmed from the incursive economic activities of European powers that grabbed almost all the natural resources of the country. Internal threat was perhaps even more grave. The article claimed that Turks, preserving their old and pernicious opinions, never renounced the dominant nation mentality. The editorial espoused a fair conscription policy that would ensure equality of non-Muslims with Muslims as the best remedy for these twin dangers. Only then “will they [non-Muslims] feel centered in the army and not be lured by foreign states and their ideals.” Once true equality and fraternity were established among the empire's populations, Ottoman peoples, united in harmony, would form a sturdy bulwark against the encroachment of European imperialists on the country. The article highlighted long military service as the greatest obstacle to the materialization of these aspirations. It asserted that a more lenient policy of conscription would arrest the Muslim population's socioeconomic decline. The failure to do so, however, would result in the state withering away. Citing the examples of Italy, Germany, France, and Bulgaria, Politikē Epitheōrēsis supported the shortening of military service to two years.Footnote 54

The length of service also preoccupied the Greek Orthodox patriarch. He was particularly invested in this issue as his community was shrinking slowly but steadily through the emigration of many young people to the Americas. To check the outflow of young Greeks, a commission was formed under the auspices of the patriarchate in late 1910, and a list of demands was submitted to the Sublime Porte.Footnote 55 The document, written by Athanasios Souliotis, opened with the patriarch's expression of concern about the large number of Greek Ottomans “abandoning our beloved country in an attempt to avoid conscription.” According to the document, the length of military service and uncertainties surrounding it prompted young people, at their most productive age, to leave the motherland. It also underscored the alienation that the newly conscripted suffered due to the small number of soldiers from the same religious group in the battalions and the absence of non-Muslim officers. This deepened their anxiety about the army. The document underlined the need for a serious overhaul of military regulations since they dated to a time when only Muslims served in the army. Keeping old practices intact and forcing non-Muslims to abide by them would exacerbate an already difficult situation, resulting in low morale among Christians.Footnote 56

Despite the swelling ranks of emigrants, Sada-i Millet continued publishing rosy stories in an effort to prove non-Muslims’ enthusiasm about military service. Among early examples is a letter published as part of a leader article in April 1910. An unidentified non-Muslim wrote that he had prevented his son from evading conscription by informing the authorities of the young man's escape attempt. In line with Sada-i Millet's general policy, this was yet another account that demonstrated the eagerness of non-Muslims for conscription, a story with a happy ending in which the rebellious son later expressed his satisfaction with being in the barracks.Footnote 57 However, emigration inspired by conscription was a serious problem that the Ottoman government sought to address by prohibiting the issuing of passports to those of draft age. The limited success of such measures was revealed by an official investigation in October 1910 that indicated that a third of prospective non-Muslim conscripts from Istanbul were actually in the United States.Footnote 58

In an article that appeared in Politikē Epitheōrēsis on 18 September 1911, Souliotis made an appeal to young Christians and urged them not to emigrate to evade the military service. He argued that their flight would grant credibility to the claim that Christians lacked the aptitude to fight for the country. For Souliotis, the length of conscription and ambiguities surrounding the draft explained, to a large degree, Christians’ evasion of service, whereas the principal reason lay in a widespread perception:

Christians still believe that the army is Muslim, or rather Turkish. For this reason, they fail to understand how they can serve as Christians in a Turkish army, how they can preserve their national and religious foundation, and how they will drill, share the same barracks and fight together with Turks who consider the army and state their own.Footnote 59

Hüseyin Cahid's earlier assertion in Tanin that had candidly proclaimed Turks “the dominant nation” in the empire never stopped disconcerting Souliotis and the Greek Ottoman deputies he worked with closely.Footnote 60 In November 1908, writing in response to manifestations of Unionist aspiration for Turkish dominance in the Ottoman Empire, the Greek Ottoman daily Proodos had declared the impossibility of assimilating Greeks: “Imagine, we could not be assimilated during the half-millennium of Roman rule. Neither could we be assimilated under the almost half-millennium of absolutism. It would be insane to think that this could happen under a regime of liberty during the 20th century.”Footnote 61 Three years later, Souliotis's consideration of the conscription issue through the lens of assimilation indicated the longevity of Greek Ottoman concerns that military service was a means to ensure Unionist authority instead of Ottoman equality: “if the conscription of Christians is a devious tool designed to effect their mental and moral Turkification, Christian recruits, by virtue of the firmness and vigor of their character, will prove to their misguided compatriots that Turkification is no longer possible.” Exhorting young Christian recruits to show patience in enduring hardships, Souliotis assured them that their sufferings would be remembered forever. They would be held in high esteem as the Christian soldiers who ended the humiliating exclusion from the Ottoman army. They would command as much respect as those who fought in Macedonian mountains against the tyranny of the pre-constitutional regime.Footnote 62

Conclusion

In his critical overview of the Torossian debate, Edhem Eldem underlines the eradication of Armenian voices from late Ottoman history by Turkish nationalist historiography, which consisted of “wiping away the memory of Armenians as citizens of the empire, turning them into foreigners or outsiders, all the more easily demonized.” Given the attempt to narrate an imperial past stripped of its ethno-religious diversity, “any evidence pointing at an Armenian serving as an officer and fighting side by side with his Muslim compatriots is bound to open a breach in the edifice of the Turkish grand narrative. As such, there is nothing wrong with wanting to promote the discovery of such cases, provided they are solidly documented.” Eldem's line of thinking culminates with a series of questions, one among them urging the reader to ask why it is crucial to prove that Armenians took part in the defense of the Ottoman Empire like their Muslim compatriots.Footnote 63

Eldem's question is also pertinent to a fuller understanding of the period following the 1908 revolution during which universal conscription debates dominated the Ottoman parliament and press. The significance of that question is particularly evident given the understudied and frequently misrepresented populations of the Ottoman Empire that merit research in their own right rather than simply as a reaction to nationalist historiography. Accordingly, the exploration of Greek Ottoman responses to the draft helps us better appreciate the complexities of the imperial past. The scrutiny of an issue as central as conscription from the viewpoint of the largest non-Muslim Ottoman population reveals alternative imperial visions at a transformative moment in Ottoman history. Between 1908 and 1912, both Greek Ottoman deputies and public figures employed the language of equality as they supported universal conscription. For them, the bedel was a humiliation and, as such, had no place in the new regime of equality, a point illustrated by the Greek Orthodox patriarch's March 1910 speech in which he equated the military service to the safeguarding of constitutional rule. Many Greek Ottomans’ distrust of the CUP, especially the fear that the military service functioned as a tool of assimilation, became a common refrain in this period. They sought to reconcile their enthusiastic support for conscription with their profound suspicion of the CUP's aims by demanding separate battalions for Greek conscripts, demonstrating the limits to equality in the postrevolutionary Ottoman Empire. In one of the ironies of Ottoman history, the requests of the Greek Ottomans were granted during World War I when the government conscripted them together with other non-Muslims in labor battalions reserved for those deemed untrustworthy to be armed against the empire's foes.Footnote 64

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Aron Rodrigue, Seçil Yılmaz, Samuel Dolbee, Selçuk Akşin Somel, Ümit Kurt, and Emre Can Dağlıoğlu for their feedback. I am grateful to Fokion Erotas, Evangelia Achladi, and Chara Kavidi for accompanying me through katharevousa labyrinths of the Greek texts. I appreciate the insightful comments by Joel Gordon and three anonymous reviewers, which helped bring the manuscript to its final form. I also thank Sarwar Alam and Aleeya Rahman for the assistance they provided with the publication. I discussed an early phase of my research with Vangelis Kechriotis. To his memory I dedicate this article.