In the autumn of 1851, a group of travelers in Central Eurasia filled their water skins from the Oxus River, loaded their Bactrian camels, and set forth westward on the road toward Iran. The caravan was on its return journey and included Riza Quli Khan Hidayat (1800–71), a Persian envoy and writer who had led the expedition to the region of Khvarazm, the large river delta on the Upper Oxus and the northern branch of the fabled Silk Road. For over six months, the mission had traversed the roads on the waterless stages of the Qara Qum or Black Sands Desert to reach the steppes of the Oxus. Its purpose was to free the thousands of Persians held as captives in Central Eurasia and to survey the unsettled eastern borderlands of Qajar Iran. Riza Quli Khan recorded the group's findings in a travel book titled Sifaratnama-yi Khvarazm and upon his return to Iran presented the manuscript to Nasir al-Din Shah (r. 1848–96). Riza Quli Khan's journal was part of a genre of 19th-century Persian travel books (safarnāma) that mapped and took measure of the Central Eurasian frontier.

Through a reading of Sifaratnama-yi Khvarazm and other 19th-century Persian travel narratives, this article attempts to locate the history of Iran and Central Eurasia within the context of recent literature on global frontier and environmental processes, including The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World by John Richards and China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia by Peter Perdue.Footnote 1 Taking their point of departure from the imperial histories of India and China, Richards, Perdue, and others have suggested that beginning in the early modern period, there occurred the closing of a great frontier in world history. This process was characterized by the expansion of the frontiers of settlement, intensified land use, and the eclipse of indigenous populations. According to Richards, the period circa 1400 to 1800 saw the global expansion and settlement of imperial frontiers:

In nearly every world region, technologically superior pioneer settlers invaded remote lands lightly occupied by shifting cultivators, hunter gatherers, and pastoralists. . . . In Africa, Eurasia, and the New World, they expelled, killed, or enslaved indigenous peoples. . . . Expansive early modern states imposed new types of territoriality on frontier regions.Footnote 2

Likewise, Perdue writes: “The expansion of the Qing state formed part of a global process. . . . Nearly everywhere, newly centralized, integrated, militarized states pushed their borders outward by military conquest, and settlers, missionaries, and traders followed behind.”Footnote 3

This grand narrative of the closing of the early modern frontier has important parallels in the history of Iran and its Central Eurasian borderlands. The period witnessed the unraveling of the Islamicate-Chinggisid world across Central Eurasia. With the centralization and expansion of Eurasian “gunpowder empires,” attempts were made to mold the steppes to the modern imperial state. During the 16th and 17th centuries, the Safavid dynasty consolidated its rule and expanded into the Central Eurasian frontier. However, unlike the Mughals, whose reign in India extended into the mid-19th century, and the Qing, who held power in China into the 20th century, the Safavids fell to the Afghans in 1722, leaving Iran's eastern borderlands unsettled in a time of dynastic instability and pastoral resurgence throughout the 18th century. The settlement of this steppe frontier occurred only with the arrival of 19th-century imperial boundary commissions and their cultural and geographical boundary-marking projects, including the production of travelogues, surveys, and maps.

There is a vast literature on Western travel writing, surveying, and mapping projects. Building on critiques by Edward Said in Orientalism and Culture and Imperialism, scholars such as Mary Louise Pratt, Thongchai Winichakul, and Thomas Metcalf, among a host of others, have examined Western geographical and ethnographic representations of the world.Footnote 4 Only recently, however, with the work of C. A. Bayly, Muzaffar Alam, and Sanjay Subrahmanyam have scholars begun to probe encounters that took place outside of a Western colonial framework and within an Asian setting.Footnote 5 This essay seeks to complement this burgeoning literature by examining environmental themes in Persianate travel narratives about the Eurasian steppes.Footnote 6

These narratives represent 19th-century imperial ventures to explore environments and gather information about the natural world. Persian travel narratives describing the deserts, rivers, oases, and peoples of Central Eurasia were influenced by both indigenous and Western traditions of exploration literature. In describing the environment, Persian travel narratives, natural histories, and geographical chronicles marked a continuation of the genres of Islamic road books (masālik u mamālik), geography (jughrāfīyyih), and encyclopedic books of science and wonders (ʿajāʾib). Such texts were also influenced by the growing body of printed Western geographical and ethnographic literature, including travelogues, journals, atlases, and maps that classified and left systematic observations of all that was encountered in the natural world. Since the early modern period, European empires had been actively engaged in efforts to represent, classify, and control environments while producing an array of encyclopedic texts based on newfound knowledge about the lands, oceans, peoples, customs, animals, flora, and fauna to be found at the ends of the earth.Footnote 7

The encounter between empires and the environment has been studied in such works as Alfred Crosby's Ecological Imperialism and Richard Grove's Green Imperialism.Footnote 8 In addition, recent works in the history of science have examined the geographical, naturalist, and botanical knowledge systems of early modern empires in great detail, considering the ways that the expansion of European empires transformed environments across the world.Footnote 9 Quite recently, the environmental dilemmas initiated by the advance of Western imperialism have generated the interest of scholars working on North Africa and the Near East. Diana Davis’ analysis of the role of French narratives of environmental decline and deterioration in the colonization of Algeria and Edmund Burke's examination of Saint-Simonian engineering projects in North Africa have begun to mine the history of European developmentalist projects in the 19th-century Maghrib.Footnote 10 Building on this literature, it is now possible to move past the Western colonial narrative to ask how indigenous or Muslim states and societies used, constructed, and perceived natural environments.Footnote 11

This article argues that 19th-century Persianate travel narratives about the Central Eurasian steppes were part of the global imperial venture to classify and reclaim the natural world. These indigenous descriptions of Central Eurasia were marked by the material encounter with the steppes and were projects for reclaiming the Oxus frontier. Far from a passive act of collecting information and more than merely an extension of observers’ preconceptions, description was an essential part of the expansion and preservation of empire.Footnote 12 Through an analysis of Riza Quli Khan Hidayat's Sifaratnama-yi Khvarazm, the following pages explore the 19th-century Muslim “discovery” of the Central Eurasian steppe world. Riza Quli Khan's journal mapped the natural, geographical, and ethnographic boundaries between the steppe and the sown. The Khvarazm expedition of 1851 set out to define imperial boundaries and to reclaim the Qara Qum Desert, but on its journey the mission found a permeable “middle ground,” a contact zone in between empires, marked by transfrontier and cross-cultural exchanges such as trade and pilgrimage.Footnote 13

A JOURNEY INTO THE STEPPES

During the first half of the 19th century, the Qajar Dynasty (1797–1925) undertook repeated military and scientific expeditions to explore and reclaim the steppes between the Caspian Sea and the Oxus River. Among these missions were the expeditions of ʿAbbas Mirza and the European-trained “new army” (niẓām-i jadīd) in 1832 and 1833 and Muhammad Shah's Herat campaign of 1837. In 1831 the crown prince ʿAbbas Mirza (1789–1833) was appointed the governor (bayglarbaygī) of Khurasan province. The following year, relying in part on the niẓām-i jadīd, he began campaigning vigorously against Turkmen raiders in the eastern borderlands. Marching out against refractory tribes and their fortresses, his troops stormed the frontier post of Sarakhs, pacifying many of the Salur Turkmen. ʿAbbas Mirza died in 1833, while making plans for an expedition against the Sariq Turkmen in the oasis of Marv, thus halting the Qajar's march into the Qara Qum.Footnote 14 The eastern campaign later resumed under his son, Muhammad Mirza, following the latter's ascension to the Qajar throne in 1834. In 1836, Muhammad Shah set out on an expedition against the Turkmen and the following year advanced into the contested domain of the Durrani Empire in Afghanistan, seeking to reintegrate Herat into the Qajar kingdom.Footnote 15 Under intense pressure from the British, Muhammad Shah abandoned the siege of Herat and his campaign in greater Khurasan in 1838.Footnote 16

Nasir al-Din Shah's reform-minded premier Mirza Taqi Khan Amir Kabir (1807–52) pursued a policy toward the preservation of Iran's eastern frontier as a measure against Russian and British imperial encroachment.Footnote 17 Seeking to reassert Qajar control over the steppes of the Qara Qum and the oasis cities of Khurasan and Transoxiana, in 1851 he ordered a government mission to reclaim the liberty of the thousands of Persian Shiʿi subjects taken captive and sold in the slave markets of Central Eurasia. Having served as an official in Tabriz and on the Azerbaijan frontier in northwestern Iran, much of which was lost to the Russians during the course of the early 19th century, Amir Kabir was keen to favorably settle Qajar frontiers in the eastern province of Khurasan. This policy entailed reclaiming the steppes of the Qara Qum and bringing an end to the destructive slave raids of the Turkmen tribes, which had cast serious doubt on the reach of Qajar imperial authority into Central Eurasia.

Amir Kabir appointed Riza Quli Khan Hidayat, a distinguished poet, writer, and scholar in the service of the Qajar court, to lead the expedition to the Oxus River and to make an ambassadorial visit to the court of Muhammad Amin Khan, the Uzbak Khan of Khiva, who had boldly styled himself “Khvarazmshah” and was providing a slave market where Persian men, women, and children could be bought and sold as captives.Footnote 18 Riza Quli Khan hailed from an old bureaucratic family in the south and had received the title of “the prince of poets” (amīr al-shuʿarā) from Fath ʿAli Shah (r. 1797–1834).Footnote 19 He was a talented writer of both prose and verse and was skilled in the writing of history.Footnote 20 His works include Rawzat al-Safa-yi Nasiri, a multivolume world history completed in the mid-19th century that linked the Qajars to the Islamic-Chinggisid empires of the past and was perhaps the most important chronicle of 19th-century Iran. In 1851, Riza Quli Khan was commissioned by Amir Kabir to gather information and keep a journal of the Khvarazm mission through the steppes of Central Eurasia:

It is your duty to write in detail a daily journal [rūznāmijāt] from the first day the mission is sent until its return to the threshold of Iran, with description and explanation [sharḥ va basṭ] of everything including events that occurred, the names of stages on the roads, the calculation of distances, [and] the identification of tribes, their chieftains, and elders [rīsh-sifīdān] and to bring this information back so that his highness [the shah] may be informed [bā-iṭilāʿ] of those people and have the knowledge he seeks about them.Footnote 21

The deployment of traverse surveys and information-gathering missions fit well with Amir Kabir's reforming agenda to consolidate the Qajar state and its frontiers. He sought a reliable, scientific survey and description of Iran's eastern steppe borderlands, detailing the physical and cultural geography of the region. The possession of knowledge about the lands, resources, and peoples of the Eurasian steppe would allow the Qajar state to possess a distant frontier. The purpose of the Khvarazm mission was the reclamation of the Eurasian steppe for the shah; the passage of the expedition and the surveys it produced were to bring imperial territory into existence.Footnote 22

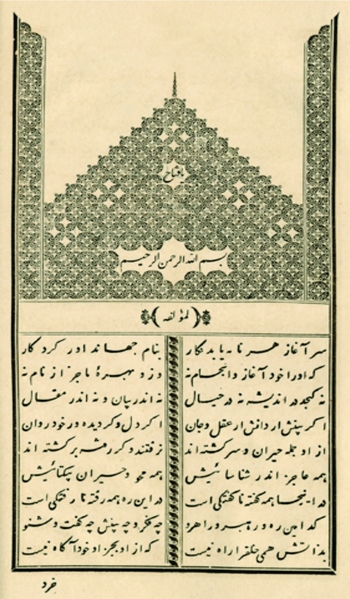

A manuscript of the travel account was presented to the shah upon the completion of the mission. A lithographed text of the Sifaratnama, comprising 151 pages in nastaʿlīq Persian script, was printed in Cairo, Egypt, at the Bulaq press in 1875 and reissued a year later in Paris under the editorship of the French Orientalist Charles Schefer (see Figure 1).Footnote 23 The text stands as just one example of the 19th-century Persianate literature of travel and exploration about the steppes of Central Eurasia.Footnote 24 During the 19th century, Persian travel accounts, newsletters, and memoirs came to be read by an ever-growing audience, as the spread of lithography and printing made possible a wider dissemination of texts.Footnote 25 Central Eurasian travel books were certain to have had a limited readership, circulating among the upper echelon of the Qajar bureaucratic elite and perhaps other literate classes in Tehran and the provincial capitals. However, through such circulation, they became significant knowledge-making projects that helped determine imperial policies and the ordering of the Central Eurasian frontier. The encounter with the steppes and the effort to reclaim the desert were among the recurring themes in this literature.

FIGURE 1. Introductory page of Sifaratnama-yi Khvarazm by Riza Quli Khan Hidayat. From the Bulaq lithograph (1875), published in France as Riza Qouly Khan Hidayat, Relation de l'Ambassade au Kharezm, ed. Charles Schefer (Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1876). [A color version of this figure can be viewed online at journals.cambrige.org/mes]

BLACK SANDS OF THE OXUS

On the fifth day of the month Jamadi al-Thani in the Muslim lunar year of 1267 (7 April 1851), the Qajar mission, including retinues from Khvarazm and a contingent of horsemen from the Atabay Yamut Turkmen tribes serving as guides (balad), embarked from Tehran.Footnote 26 The mission was given three months and 2,000 tumans to complete a perilous journey that would take it across the eastern boundaries of the empire to “the Jayhun [Oxus] River that flows between Iran and Turan.”Footnote 27 To reach the waters of the Oxus and the oasis cities of Central Eurasia, the travelers would have to traverse the parched and waterless Black Sands Desert, the Qara Qum.

The expanse of land that forms Central Eurasia extends from eastern Iran to western China. With the exception of the oasis cities of the Silk Road, much of this region comprises steppelands bounded by forests in the north and interspersed with deserts and semideserts in the south. Over the longue durée, the history of Central Eurasia has centered on the interactions of the Turkic nomadic pastoralist world with the settled and mostly Persian-speaking populations of oasis cities.Footnote 28 This interface between the steppe and the sown is one of the most significant themes in Central Eurasian and Middle Eastern environmental history.

The Oxus River, or Amu Darya, originates in the Pamir Mountains in modern Afghanistan and flows northward, parting the Black and Red Sands deserts before emptying into the Aral Sea, approximately 1,500 miles from its source. From the Pamir Mountains, the stream of the Oxus passes to the north of the Balkh oasis and then winds through the sun-drenched steppes south of the city of Bukhara before reaching the delta of Khvarazm near the end of its course. On its path from the mountains to the sea, it flows through and marks the borders of four present-day states—Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The waters of the Oxus are a source of cultivation and settlement in the steppes of Central Eurasia.

The hydroclimatic history of the Oxus is difficult to trace and not known for certain. The river has flowed north from the Pamir Mountains since the late Pleistocene (the geological period that ended about 10,000 years ago). However, its flow has historically been prone to changes and fluctuations carrying environmental consequences for the frontier between the steppe and the sown. During intervals throughout its history, the river is believed to have partially flowed into the Caspian Sea by way of the Uzboy Channel, an ancient bed of the Oxus that is dried up today. In flood years, the Oxus would overflow, emptying into the Sarykamysh depression about 150 miles southwest of the Aral Sea, continuing its westward flow through the Uzboy Channel into the Caspian Sea. Thus, until the 16th century, when the Oxus is believed to have changed course, the Caspian and the Aral may have been episodically connected through other bodies of water lying between them.Footnote 29 Climatic fluctuations as well as irrigation works along the Oxus in Khvarazm may have affected the course of the river and the channels it flowed through. What is certain is that since the 16th century the Oxus has flowed north only into the Aral Sea, and there occurred a complete desiccation of the Sarykamysh depression.

The steppes of the Oxus were legendary in the Persianate geographical imagination, connoting the liminal edges of the empire.Footnote 30 In the Shahnama, the 10th-century Persian epic poem by Firdawsi, the Oxus is the legendary frontier ground (sarḥadd) between Iran and Turan. Classical Muslim geographers, who called the Oxus by the name Jayhun or Amu Darya, classified it as the edge of civilization, designating the land south of it as the Iranian province of Khurasan and the region to the north as Mavaraʾulnahr, “the other side of the river,” or as commonly referred to in the West, Transoxiana.Footnote 31 Travelers approached the Oxus with great wonder and highlighted its strangeness, such as the fact that it froze over in winter, and called the surrounding steppes “the Desert of the Ghuzz Turkomans.”Footnote 32 The Oxus was also seen as a cultural divide, “the water where unbelievers were hidden [āb-i kāfir nahān]” and the abode of pastoral nomads.Footnote 33 The steppes of the Oxus were thus long imagined to mark a geographical and cultural frontier.

The Oxus frontier and its steppes became the subject of unprecedented surveying and cartographic projects during the 19th century. The Qajar dynasty and other surrounding empires sought to gather scientific information and bring cultivation to the desert steppes as a means of claiming territory. Persian engineers in the service of the Qajars were engaged in the effort to map the physical and cultural geography of Iran's borderlands with Central Eurasia and to mark the boundaries between wildlands or desert (bīyābān) and cultivated lands (ābādān). The remnants of these imperial cartographic projects may be found in Qajar maps, geographies, and gazetteers.Footnote 34 Similar sorts of records from the period may also be found in issues of the illustrated imperial gazetteer, Ruznama-yi Dawlat-i ʿAlliya-yi Iran, printed under the auspices of the royal house of crafts (Dar al-Funun). In 1863, the gazetteer printed lithographed maps of the Turkmen steppes, noting that scientific mapping “was very new since the area possessed a dangerous and frightening landscape and no engineer had previously ventured there to make maps” (see Figure 2).Footnote 35

FIGURE 2. Map showing the pastures and encampments of the Yamut and Guklan Turkmen tribes on the eastern shores of the Caspian Sea, the province of Astarabad, and the river Gurgan and its tributaries. The map, made at the Qajar imperial school, the Dar al-Funun, following a state military campaign against the Turkmen, shows the location of natural and geographical features on the frontier, including mountain (kūh), forest (jangal), and pasture (chaman). From Ruznama-yi Dawlat-i ʿAlliya-yi Iran (1281/1863) (Tehran: National Library of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1370/1991).

Sifaratnama-yi Khvarazm may be read in light of this larger endeavor to explore, survey, and define the boundaries between the steppe and the sown. This was as much by necessity as design because the expedition required practical information about the desert to safely reach the Oxus. Standing on the brink of the Qara Qum Desert, Riza Quli Khan and his party arrived at the edge of an “endless ocean [daryā-yi bīpāyān],” the sands overshadowing all settlements and villages.Footnote 36 “The wilderness road to Khvarazm,” he wrote, “is a road that is arduous and full of labors [rāh-i bīyābān-i khvarazm rāhī ast pur zaḥmat].”Footnote 37 Describing the travelers’ sojourn to the banks of the Oxus, Riza Quli Khan wrote, “The sands poured down on our heads, cut the ropes of our tents, and put out our lights.”Footnote 38 Their journey became a seemingly endless quest to find water, and as the party neared the bank of the Oxus they were surely aware that they had entered a frontier ground beyond the pale of the Qajar dynasty. The Oxus was the classic eastern frontier, but a wide distance now seemed to separate it from the guarded domains of Iran. The mission continued its journey through the steppes in order to reach the populated and flourishing places (maʿmūra; jahān) that lay beyond.Footnote 39

Upon reaching the Oxus, Riza Quli Khan examined its geography and natural history, recording his observations of the river and its environs. He described the source of the river in the Pamir Mountains and traced its winding course to the Aral Sea, noting that the river shaped patterns of settlement and trade:

It is said that the Jayhun originates from two waterfalls in the region of Badakhshan and flows mightily passing many cities and settlements on its course toward Khvarazm where it empties into the Aral Sea (Bahira-yi Khvarazm). During winters, the river is frozen over, allowing caravans to pass over it, while the water flows beneath the ice.Footnote 40

Moreover, Riza Quli Khan observed signs of substantial changes in the flow of the river, with consequences for the frontier between the steppe and the sown. He suggested that water from the Oxus had once flowed across the Qara Qum Desert and into the Caspian Sea through riverbeds and canals that had since dried up. Tracing the old bed of the Oxus, he found evidence to support the fact that the Aral and the Caspian were once joined and that historically the course of the river was prone to fluctuations:

It is said that the Aral once flowed through an underground channel into the Absikun and from there into the Caspian [Bahira-yi Khazar]. And it is written in some chronicles that in the past, the Oxus used to flow eastwards until the Mongols dug a new channel and redirected the waters toward the Caspian. On the road back and forth to Khvarazm, I saw certain vestiges and signs that remained . . . One still sees traces of its dried-up bed.Footnote 41

Riza Quli Khan observed that sometime since, the river again swerved eastward, emptying completely into the Aral Sea.

Along the banks of the Oxus, the expedition passed ruined settlements and cities (āsār-i shahrhā-yi kharāb va vīrān bisīyār ast), deserted trade routes where few caravans ventured, and fragmented monuments, their domes and inscriptions worn away by time and covered by dunes.Footnote 42 The desert had slowly obscured the monuments of the past, such as the Gunbad-i Qavus, which stood alone, partially buried in the steppes.Footnote 43 “Lands where settlements had once flourished,” Riza Quli Khan lamented, “had become a desert of sand.”Footnote 44 The Khvarazm mission discovered evidence to suggest that the fluctuations in the flow of the Oxus had precipitated the expansion of the steppes of the Qara Qum.

Riza Quli Khan displayed an agrarian and irredentist impulse to reclaim the steppes of the Oxus, restoring them to a supposedly more fertile past. His descriptions of the desert echo the “declensionist narrative” of environmental history, which has been deconstructed at length by William Cronon and recently examined by Diana Davis in her pathbreaking study of the French colonial mission in Algeria.Footnote 45 Davis explores how a narrative of decline associating the arrival of pastoral nomads with the deforestation, desertification, and degradation of the North African landscape since the reportedly fertile Roman past contributed to French colonial expansion in the Maghrib.Footnote 46 She reveals how even the scientific fields of geography, botany, plant ecology, and phytogeography (the geographical distribution of plant species) conformed to the dominant French colonial narrative of environmental decline in North Africa.

Little is known, however, regarding indigenous, Islamicate systems of knowledge about nature and their role in projects to reclaim natural environments. In many ways, 19th-century Persian travel accounts such as Sifaratnama-yi Khvarazm were also the products of imperial surveying projects and offered narratives of decline and deterioration, painting the Eurasian steppes as fallen and unsettled badlands. However, restricting the analysis to such a perspective would miss other features that emerge from a reading of 19th-century Persianate narratives about the steppes of Central Eurasia.

Alternative descriptions of the desert are discernable in the Sifaratnama-yi Khvarazm. Among the most important was that the steppes were not badlands but rather an ecological space created through the fluctuations of the boundaries between cultivated lands and wildlands—the ebb and flow of the steppe frontier. The steppe and the sown were tangled and interwoven. Persian travel writings, geographical literature, and natural histories about Central Eurasia belonged to a perennial and long-standing effort to describe—and thus to control, order, and manage—the arid steppe frontier and its population. However, the boundaries between steppe and sown, as well as those between pastoral nomadic and settled populations, remained fluid, and there was little impulse on the part of the Qajars and their agents to permanently cultivate the desert. The Qajars were, after all, a dynasty with origins based on Turkic pastoral and tribal power. They claimed the Central Eurasian steppes as part of their wild, Turanian heritage. In early Qajar paintings, Central Eurasian and Turko-Mongol historical figures such as Afrasiyab and Chinggis Khan are represented in Persian garb (see Figure 3). For the Qajars, the wildness of the steppes had not lost its appeal.

FIGURE 3. Qajar painting of Chinggis Khan by Mihr ʿAli, 1803–1804. Private collection, Paris. Courtesy of the Iran Heritage Foundation, London. Reproduced with permission. [A color version of this figure can be viewed online at journals.cambrige.org/mes]

The Khvarazm expedition of 1851 certainly was driven by an irredentist concern for reclaiming the steppes of the Oxus. For all its ornate language, the record of the mission, Riza Quli Khan's Sifaratnama-yi Khvarazm, is a text that uses the 19th-century science of description to survey the Central Eurasian environment. However, the project came to be mediated by the physical and material encounter with the steppes.Footnote 47 The venture to know and order nature went beyond the preconceptions of observers. It was forged through actual contact with the desert and tempered by the powerful economic and cultural networks that the agents of empire encountered there.

WRITING THE STEPPES

An important element of imperial surveying projects involved the ethnographic representation of “unknown” peoples, races, and tribes of the different parts of the world. Central Eurasia figured into this imperial mission to identify, take measure, and write the histories of indigenous populations. Persian travel narratives of the 19th century attempted to survey and gather information about the customs of the pastoral nomadic Turkmen tribes of the Central Eurasian steppes.

The Turkmen were a conglomeration of frontier peoples inhabiting the steppes between the Caspian Sea and the Oxus River.Footnote 48 During the 19th century, their encampments could be found on the fringes of the Kopet Dagh Mountains in the Qara Qum Desert, where they wielded considerable independence and power on the unsettled Central Eurasian frontier. According to the chronicle of Mir ʿAbd al-Karim, the Turkmen were “settled along the banks [lab-i āb] of the Amu Darya River for four or five days march and are made up of the following tribes [ṭāyifa]: Ersari, Sariq, Baqah, Salur, Tekke, Amir ʿAli, and Chawdur.”Footnote 49 They spoke Turkish dialects and adhered to local Islamic beliefs and customs. In the 19th century, the Turkmen practiced both pastoral nomadism and agriculture. The tribes who adopted a nomadic and migratory way of life were called chūmūr and those who were sedentary chārvā. All possessed flocks of sheep and herds of horses while living in wooden, felt-covered yurts. Nineteenth-century sources estimated the population of the Turkmen according to the number of tents or yurts, with some estimates reaching over 150,000 yurts or roughly 750,000 individuals.Footnote 50

Persianate travel writers and surveyors cast the Turkmen as pastoral nomads on an unsettled and unassimilated frontier. In travel narratives, the Turkmen gallop off the pages as rapacious raiders and slave traffickers marauding the eastern borderlands. A recurring theme in these accounts is Turkmen violence on the frontier. Turkmen pastoral nomads were depicted as the untamed inhabitants of a wild landscape, wicked tribes (ṭavāyif-i ashrār) inhabiting the banks of the Oxus and raiding the surrounding roads and villages, carrying off Shiʿi Persians as slaves.Footnote 51 In these sources the Turkmen stir havoc and fear through their surprising forays (chapū) and violent slave-raiding expeditions (ālāmān), with devastating effect on trade and cultivation in the eastern borderland provinces of Astarabad and Khurasan. The slave traffic of the various Turkmen tribes was blamed for having caused the abandonment of villages and for having brought about the decline of cultivation and trade.

On the road to Khvarazm, Riza Quli Khan observed the consequences of slave traffic on the eastern Iranian frontier. He described ruined villages where the entire population had taken flight or had been carried away or killed. Walls fortified the settlements that survived, and towers were raised where peasants could retreat in case of attack. The fear of the Turkmen (khuf-i turkmān) was so strong among the peasantry that they carried arms when they worked in the fields and rarely stepped beyond the village walls. On the once thriving trade routes of Khurasan, Riza Quli Khan wrote, the number of caravans that ventured to cross the eastern Iranian frontier had diminished. He described the road ahead as passing through the “terrifying landscape” (sarzamīn-i makhawf) of the Turkmen Sahra and recorded verses on the uncertain and arduous journey they faced: “Even a lion of war would be shaking on that hard frontier/Where awaited more than a hundred thousand Turks with spears [dil-i shīr-i jangī dar ān sakht marz/zi gurgān-i gurgān hami larz larz/hamānā ki turkān-i nayza guzār/dar īn rāh afzūntar az ṣad hizār].”Footnote 52 He and his fellow travelers on the Khvarazm expedition were left “with no feet to go and with no place to stay [na pāy-i raftan va na jāy-i māndan].”Footnote 53

Surveying migratory steppe peoples proved a vexing task for travelers and explorers. For instance, in the illustrated manuscript of the travel book Safarnama-yi Turkistan, produced at the Dar al-Funun in 1861 and kept at the National Library in Tehran, the pastoral nomadic populations of Central Eurasia are cast as elusive, migrating with their animals and yurts (ālāchīq) while “leaving behind only the black patches of their fires on the ground after their departure” (see Figure 4).Footnote 54 In a similar vein, Riza Quli Khan lamented the inhospitable nature of the land: “This endless desert [ṣaḥrā] has no villages [ābādī], no trees [shajar], no stones [ḥajar], and no signs [ʿalāmat]. Distances are not known. The Turkmen call the lands by names of their own and themselves know the places where water is found.”Footnote 55 Moreover, Riza Quli Khan continued, information on the unsettled and free-spirited Turkmen was difficult to obtain:

The Turkmen tribes have no cities that would wall or enclose them and are not constantly settled in one place. It is difficult to estimate their numbers. They are spread and scattered from the steppes of Gurgan to Khvarazm. Some number thirty thousand, some less, some more, and they are met day and night all along the desert that stretches for more than twenty days travel between Astarabad and Khiva. There are various tribes and subtribes and some are enemies to one another. To list the names of all their sections and clans would take too long. Each person is a commander [sardār] in his own tribe. No tribe serves another. Even perhaps the lowliest camel driver does not follow his own chief and khan.Footnote 56

The Turkmen steppes were a terra incognita, an unknown terrain. In mapping the physical and cultural geography of Central Eurasia, 19th-century Persian travel narratives were prone to casting the steppes as a forbidding and inhospitable land. However, these sources also reveal so much more, above all that steppe peoples were integrated into Eurasian networks of trade, traffic, and cultural exchange. In the parched sands of the Qara Qum, where rivers swerved away and oases were lost, the Turkmen tribes built a thriving pastoral economy and entered the pilgrimage routes of the Naqshbandi Sufi brotherhood.

FIGURE 4. Manuscript page from “Safarnama-yi Turkistan” (1861), produced at the Qajar imperial school, Dar al-Funun. National Library, Tehran, Mss. 1368. [A color version of this figure can be viewed online at journals.cambridge.org/mes]

NETWORKS OF ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL EXCHANGE

In Persianate travel writing about Central Eurasia we find descriptions of economic and cultural networks that fostered an array of transecological and cross-cultural encounters.Footnote 57 Collecting information on the geography, natural history, trade, and customs of the Eurasian steppe, travel writers discovered a frontier ground defined by exchanges and interactions between the steppe and the sown.

Though the long-distance trade of silk may be better known, intermediary networks linking nomadic pastoralists to urban life also crossed the caravan (qāfila) routes of Central Eurasia. The trans-Eurasian caravan trade—of horses, silver, tea, wool, salt, grains, and plants—linked pastoral nomads and merchant centers. Recent literature has called into question the familiar claim that following the rise of the newly discovered sea routes of the Indian Ocean during the 16th century, Central Eurasian overland traffic and its grand market centers were eclipsed, falling into ruin in the steppes.Footnote 58 Throughout the 19th century, the Central Eurasian steppes remained a zone of contacts, encounters, and exchanges across ecological and cultural boundaries. The trade and traffic of the Turkmen, Afghans, Tajiks, Persians, Uzbaks, and other ethnolinguistic groups broke the lines of division in a wider Eurasian world. This Eurasian culture complex was shaped by contacts and exchanges between nomadic pastoralists and settled populations, bridging the steppe and the sown.Footnote 59

During the Khvarazm expedition, Riza Quli Khan observed that the Turkmen's livelihood and subsistence were derived from their horses, camels, and sheep.Footnote 60 He described twice-weekly bazaars in the city of Khiva that attracted nomads from the steppes and were crowded with horse traders (asb-furūsh), camel traders (shutur-furūsh), and slave traders (asīr-furūsh) on Mondays and Fridays.Footnote 61 In the stables of the Khan of Khiva could be found prized Akhal Tekke horses, each worth between 500 and 1,000 tumans.Footnote 62 In his survey of the Yamut Turkmen of Aq Qalʿa, Riza Quli Khan identified the tribes’ resources, which included herds of camels (shutur) and flocks of sheep (gūsfand), the latter of which were the source of exquisite wool and the basis of the distinctive weavings made by the women of the Yamut.Footnote 63

Other 19th-century travelers provided similar accounts of the Turkmen's role in economic exchanges between the steppe and the sown. According to one observer, in the Qara Qum “twice weekly a makeshift bazaar was assembled in Marv near the near the fortress of Qushid Khan Qalʿa and . . . all the tribes gathered there to trade their goods and merchandise from dawn until dusk.”Footnote 64 Although some locals possessed Persian and Bukharan currencies, their wealth consisted primarily of livestock and crops.Footnote 65 The trade of pastoral nomads, in this case the Tekke Turkmen, in horses, camels, sheep, wool, and textiles bound them to the oases of Khurasan and Mavaraʾulnahr.Footnote 66 In the bazaar of Marv they traded with merchants from Khiva, Bukhara, and Mashhad for silk, cotton, tobacco, tea, sugar, and rice, which could not be grown in the sandy and parched soil of the Qara Qum.Footnote 67 Others observed the wide circulation of resources from the steppes; the trade in the prized horses of the Turkmen, for instance, reached from the Qara Qum into Qajar Iran and Mughal India.Footnote 68

Travelers also detailed the Turkmen traffic in slaves. Since the fall of the Safavid Dynasty in the 18th century, the Turkmen had raided the borderlands of Iran for Shiʿi slaves. By the early 19th century, it was customary for the khans, princes, and ʿulamaʾ of Central Eurasian cities such as Bukhara and Khiva to endorse the Turkmen marches through the desert to Khurasan to raid caravans, towns, and villages for slaves. The Turkmen built a powerful slave-raiding and trading network in the borderlands of empires. Turkmen slave raids and surprise attacks were predicated on their pastoral economy and were made possible by the speed and endurance of Turkmen horses in crossing the steppes of the Qara Qum. Raiding expeditions were led by a commander and varied in number of horsemen from three to 1,000, depending on the number of men in an encampment possessing a good horse. Raiding parties sought out passing caravans of travelers, merchants, and pilgrims on the roads and plundered frontier towns and villages, carrying away Persian captives tied on to horses or dragged along on foot in chains. Upon reaching the steppes, some of the captives were put to the work of cultivating fields and grazing flocks and herds in the Turkmen grasslands. Others were ransomed or sold into slavery in Central Eurasian cities, including Khiva and Bukhara.Footnote 69

Some information on the slave trade may be gleaned from 19th-century European travelogues. In the 1840s, it was reported that the slaves were sold, through purchase or barter, to Uzbak merchants who visited the Turkmen encampments two or three times a year. At the time, the price paid for a ten-year-old boy was reported to be forty tumans, a man of thirty was worth twenty-five, and so on, the value decreasing with the age of the slave.Footnote 70 This estimate overlooks the fact that many of those taken captive were girls and women. In the language of colonial masculinity, Arthur Conolly noted earlier in the 19th century that “the Toorkmuns capture many beautiful women in Persia. . . . torn from their homes, and taken under every indignity and suffering through the desert, to be sold in the Oosbeg markets.”Footnote 71 Later in the 19th century, Henri Moser reported that Shiʿi slaves were sold in the markets of Central Eurasia for between forty and eighty pieces of gold (ṭalā), with girls between the ages of ten and fifteen years and men between twenty-five and forty years being worth the most.Footnote 72 The Turkmen took as captives “the strong and the beautiful,” whom they could sell in the slave markets of Central Eurasia, which became lined with Shiʿi men and women for sale. European accounts of the 19th century estimated that there were 200,000 Iranian slaves in the Khanate of Bukhara and 700,000 in the Khanate of Khiva alone.Footnote 73

Riza Quli Khan's Sifaratnama and other 19th-century Persianate travel accounts also surveyed the Turkmen's integration into the cultural networks of the Eurasian steppes. Crossing into the Qara Qum, Riza Quli Khan and other Persianate travelers entered the currents of Islamic networks and brotherhoods; they responded by writing geographies of Central Eurasian Sufism and charting networks of pilgrimage between the steppe and the sown. During the 19th century, pilgrimage to the tombs of saints (zīyārat) played a central role in the religious life of the Eurasian steppes. Riza Quli Khan reported the traffic of the Sufis or Muslim mystics/ascetics and mendicants (darvīshān; qalandarān) performing wondrous deeds (karāmat) among the peoples of the steppes (ṣaḥrā-nishīn).

The expedition passed many tombs of saints belonging to the Naqshbandi Sufi brotherhood or tariqa (literally “path” or “way”).Footnote 74 Having made pilgrimage to the tomb of the eponymous founder of the brotherhood, Khvaja Baha al-Din Naqshband (1318–89), on the outskirts of Bukhara, the itineraries of Naqshbandi pilgrims carried them farther into the steppes. Riza Quli Khan observed the disciples of the brotherhood plying their way between the many tombs of saints (mazār) and Sufi lodges (khānqāh; qalandar-khāna) on the desert road to Bukhara.Footnote 75 He took measure of the cultural exchanges connecting the steppe and the sown through such descriptions of Central Eurasian networks of pilgrimage, mapping the complex of Naqshbandi shrines and enumerating the brotherhood's mendicants, mystics, and disciples making pilgrimage across the Black and Red Sands deserts.Footnote 76 Moreover, he observed the affinity forged between steppe peoples, such as the Turkmen, and charismatic saints through shrine pilgrimages. With the building of lodges and the organization of pilgrimages, the Naqshbandi brotherhood wove the steppes into a wider Islamic ecumene.

For a Persian with mystical leanings accustomed to the doctrinal and at times stringent juridical brand of Shiʿism found in urban Iran, with the shariʿa-minded ʿulamaʾ class at the forefront, the Sufi culture of Central Eurasia must have been a welcome change.Footnote 77 At the turn of the 16th century, as Shah Ismaʿil I established the Safavid dynasty (1501–1722) in Iran, the Shaybanid Uzbaks became the sovereigns of Transoxiana. As the Safavids set out to convert Iran to Shiʿism, the Shaybanids promoted Sunnism, resulting in what some scholars have suggested was an almost permanent cultural rift between Iran and Central Eurasia.Footnote 78 Thus, although Iran was mostly converted to Shiʿism in the Safavid period, the Eurasian steppes remained grounded in Sunnism and indigenous “Inner Asian” Islam.

In his travel narrative, Riza Quli Khan traced the Naqshbandi brotherhood's expansion outward from Bukhara into the surrounding steppes. The mission surveyed the geography of Sufism, passing and identifying the consecutive graves of saints with the greeting az ānjā guzashta mazār-i dīgar rasīdīm. The party passed the tomb of Khvaja Azizan of Bukhara, a weaver (nasāj) who had become one of the disciples (murīdān) of the grand Naqshbandi brotherhood. Coming from Bukhara to settle on the banks of the Oxus, the shaykh was said to have had gained so many disciples that he worried the local sultans.Footnote 79 The mission passed several other places of pilgrimage, including the tomb of Shaykh-i Sharaf and the Yaraqra Qapi shrine. They passed a tall, blue-tiled dome said to be the tomb of a woman saint named Turbay Khanum and that was known to be “frequented by tribes with strange clothes and hats [libās-i gharīb va kulāh-i ʿajīb] who made pilgrimages to the tomb.”Footnote 80

The expedition arrived at a place on the edge of the Oxus River (bar lab-i jayhun), where a Turkish shaykh named Hakim Ata lie buried. Hakim Ata had belonged to the Naqshbandi chain of transmission (silsila), and his resting place was at the margins of settlement in Khvarazm (intihā-yi ābādī-yi khvarazm ast). The travelers then crossed over to the Red Sands Desert.Footnote 81 On the road they passed the tomb of Adun Ata, a Turkish shaykh with great rank (shān-i ʿālī) among nomadic pastoralists who regarded his shrine as a place of pilgrimage (zīyāratgāh).Footnote 82 On another occasion Riza Quli Khan had the opportunity to observe the devotion and loyalty of the Turkmen to the Naqshbandi shaykhs. “On the night of the revered Sayyid Rahmatallah Khoqandi-yi Naqshbandi's death,” he wrote, “the Turkmen people came despite great difficulties, and despite the fact that they are people of the steppes and are unaccustomed to crossing tall mountains and full forests [kūh-i sakht va jangal-i pur-dirakht]—which do not exist in their lands.”Footnote 83

In Khvarazm, Riza Quli Khan also noticed the cult of saints built around more eccentric and heterodox figures on the Central Eurasian frontier. One such example was Mazar-i Pahlavan Mahmud Khvarazmi, also known as Hazrat-i Pahlavan, who was renowned for his strength and considered the champion of his time (sar-āmad-i ahl-i zamān būd). Nearby was the Mazar-i Chahar Shahbaz. The poor (faqīrān) of Bukhara, Khoqand, and Khiva, as well as “strangers from all lands [ghurabā-yi har dīyār],” spent time at these two tombs, which also served as hospices.Footnote 84 From contemporary sources, then, it becomes clear that Central Eurasian steppe societies were integrated into wider Muslim networks that bridged ecological frontiers. The Qara Qum was criss-crossed by Naqshbandi networks and immersed in the world of Central Eurasian Sufism.

In surveying the Central Eurasian steppes, the Khvarazm expedition discerned a zone of contact marked by transfrontier networks of trade and pilgrimage that integrated pastoral and settled populations.

CONCLUSION

Following a difficult journey through the desert road and a proverbial brush with a Turkmen raid, the Khvarazm expedition returned to Tehran in the holy month of Muharram in the Muslim lunar year 1268 (November 1851), seven months after the mission had begun.Footnote 85 The Oxus expedition, which had been ordered by Prime Minister Mirza Taqi Khan Amir Kabir to reclaim the steppe borderlands of Central Eurasia, had found little success. Instead of hastening the abolition of the traffic in Persian slaves, the members of the expedition were nearly taken captive, and the mission needed Turkmen guides to get in and out of the Qara Qum Desert in safety. Upon meeting Muhammad Amin Khan of Khiva, the expedition found that his rule did not extend into the steppes of the Qara Qum. Although he had established alliances with the slave-raiding Turkmen—offering Khiva as a market for their captives, purchasing some Persian slaves, and allotting the Turkmen land and water rights in return for service as horsemen and retinues—the steppes of the Qara Qum were beyond the pale of his control.Footnote 86 This lack of imperial authority was proven in 1855, when the Tekke Turkmen resoundingly defeated the Uzbaks, killing the Khan of Khiva in battle and sending his head to the shah. Moreover, in 1860, during the reign of Nasir al-Din Shah, the Turkmen routed thousands of Qajar infantry and cavalry that had marched on Marv under the governor of Khurasan, Hamza Mirza Hishmat al-Dawla, and thousands of Persians were led into captivity.Footnote 87 The disastrous Marv campaign of 1860 would constitute the last serious Qajar attempt to reclaim the Eurasian steppe frontier.Footnote 88 The limitations faced by Islamic empires in the Eurasian steppe convey the compromise and accommodation that defined imperial encounters on the shared contact zone that environmental historian Richard White has termed the “middle ground.”Footnote 89

The written record of the expedition, Riza Quli Khan's Sifaratnama-yi Khvarazm, was a boundary-marking project produced through the material encounter with the Eurasian steppes. It may be approached in the context of the imperial venture to survey and reclaim natural environments across the world. Observation and description were means of ordering and domesticating nature. The scientific description and surveying of environments—geographical, naturalist, botanical, and ethnographic—bounded imperial territories and defined borderlands. However, these narratives of exploration were forged through imperial encounters on the ground. During the 19th century, Persianate travel writers and surveyors explored and inscribed the Central Eurasian steppes in the genre of the safarnāma. Riza Quli Khan's journal of the 1851 Khvarazm expedition represents the Qajar impulse to define and reclaim Eurasian borderlands. But this reclamation project was reshaped by the encounter with the pastoral steppes and the permeable and protean nature of Eurasian frontiers.