Introduction

Ingestible medical devices (IMDs) have nurtured a hefty interest among the researchers engaged in this field over the last few decades. Wireless capsule endoscopy (WCE) systems are a type of ingestible electronic device used in medical applications where images of the human digestive tract or gastrointestinal (GI) tract are captured. Inaccessible portions of the small intestine that are undetectable and cannot be diagnosed by conventional types of endoscopy/colonoscopy are examined by capsule endoscopy. Non-invasive and painless capsule endoscopy is seen as a better choice than the painful and time-consuming conventional techniques. The patient is asked to swallow a tiny camera embedded small capsule. The capsule moves through the GI tract by peristalsis method taking images, which are communicated outside the patient's body and collected by a receiver unit. The collected images are interpreted by a physician either in real-time or in offline mode.

Different frequency bands are suggested for various biomedical applications like industrial, scientific, and medical (ISM) bands which cover 433.1–434.8, 608–614, 868–868.6, 902.8–928, 1395–1400, 1427–1432 MHz and 2.4–2.5 GHz, the Wireless Medical Telemetry Service (WMTS) [2] and 401–406 MHz for Medical Implants Communications Services (MICS) by the ITU-R recommendation in 1998 [Reference Pan and Wang1].

From the reported study it has been observed that, as the center frequency of operation increases the useful bandwidth is enhanced, hence the maximum data-rate is also enriched. However, various attenuation factors for wireless communication are also augmented. For example, in 900 MHz bandwidth is 26 MHz where water absorption is low as compared to 2450 MHz where around 100 MHz operational bandwidth is offered. Accordingly, depending upon the application requirement frequency of operation is chosen for optimum throughput of the system. Moreover, different frequency bands are allocated around the globe according to some internally region-wise classifications, like- 433 MHz is allocated in Europe, Africa, and Russia, whereas 2450 MHz band is globally used most popular ISM band.

The frequency of operation decides the architecture of the whole antenna system. Moreover, the frequency of usages decides the link budget calculation for this tiny device. Fig. 1 shows a typical commercial WCE capsule. In the subsequent sections, the background of this technology and art and sciences are explained.

Fig. 1. Wireless capsules for endoscopy (PillCam SB and PillCam ESO) [Reference Pan and Wang1].

Background and history

The first ingestible wireless-capsule known as an endoradiosonder or radio pill having very limited capabilities like measuring a few physiological parameters with the help of sensors, such as pH, temperature, and pressure of the GI tract was developed in the 1950s [Reference Pan and Wang1]. The idea of wireless video capsule endoscopy was first proposed by Iddan later in 1981 [Reference Basar, Malek, Juni, Shaharom Idris, Iskandar and Saleh3] to see the earlier inaccessible areas of the wall of the human digestive tract painlessly. In 1997 Swain et al. [Reference Basar, Malek, Juni, Shaharom Idris, Iskandar and Saleh3] developed a number of working models of a capsule endoscopy system with a tiny camera, a video processor, a light source, a microwave transmitter and got satisfactory results from the conducted experiments. In those prototypes, a dipole antenna, and a battery were also used. A passive video capsule system was introduced in 2000 which used the low-power, CMOS-based image sensor [Reference Basar, Malek, Juni, Shaharom Idris, Iskandar and Saleh3] and was guided by the natural peristaltic motion of the GI tract. It was formed of three main parts, the swallowable capsule, a portable image-recording system attached to a belt or jacket worn by the patient, and a workstation computer with powerful image processing software [Reference Waghmare, Panchal and Poul4] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Typical WCE system [Reference Pan and Wang1].

Almost every system in the image-recording subsystem uses eight body leads/antennas. The body leads are connected to the abdomen and the chest of the patient as per the guidelines. The image processing software processes the collected images for diagnosis. An advanced algorithm constantly detects the strength of the signal received by the lead sand whichever receives the strongest signal, its position determines the position of the capsule. The algorithms can also differentiate between different color pixels so as to distinguish between the different anomalies of GI tract.

Antenna architectures

Unlike other communication systems, the antenna in WCE system behaves as an electronic eye and is one of the most essential components in a WCE system. The primary design criterion of the antenna for WCE is that it should be compact in size so that it fits inside the ingestible capsule. Thus it is absolutely necessary that the antenna size obeys the optimal capsule dimensions of 5–11 mm diameter and a length below 26 mm. An 11 mm × 26 mm capsule approximately weighs 4 gm. To design such a compact antenna suitable for medical application, a number of steps have to be followed. Apart from this, the radiation pattern of the antenna should be very near to omni-directional and with a large bandwidth profile to mitigate all the detuning factors inside the human body during the movement of the capsule through the GI tract. Moreover, the SAR value has to be maintained for the said antenna system (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Geometry of the WCE capsule (26 mm × 11 mm) [Reference Pan and Wang1].

Keeping in view of the application field, a planar miniaturized version of the antenna is essential for WCE system. Miniaturization of the antenna structure can be done in several ways. However, the efficient way is to select the miniaturization technique, which fulfills the mandate radiation characteristics too. Literature survey reveals that, diverse antenna designs have been proposed over the years for various biomedical applications, such as a monopole, helical, planar inverted F-antenna (PIFA), slot PIFA, folded slot dipole, loop antenna, rectangular patch, etc. The following sections describe various such antenna architectures adopted practically.

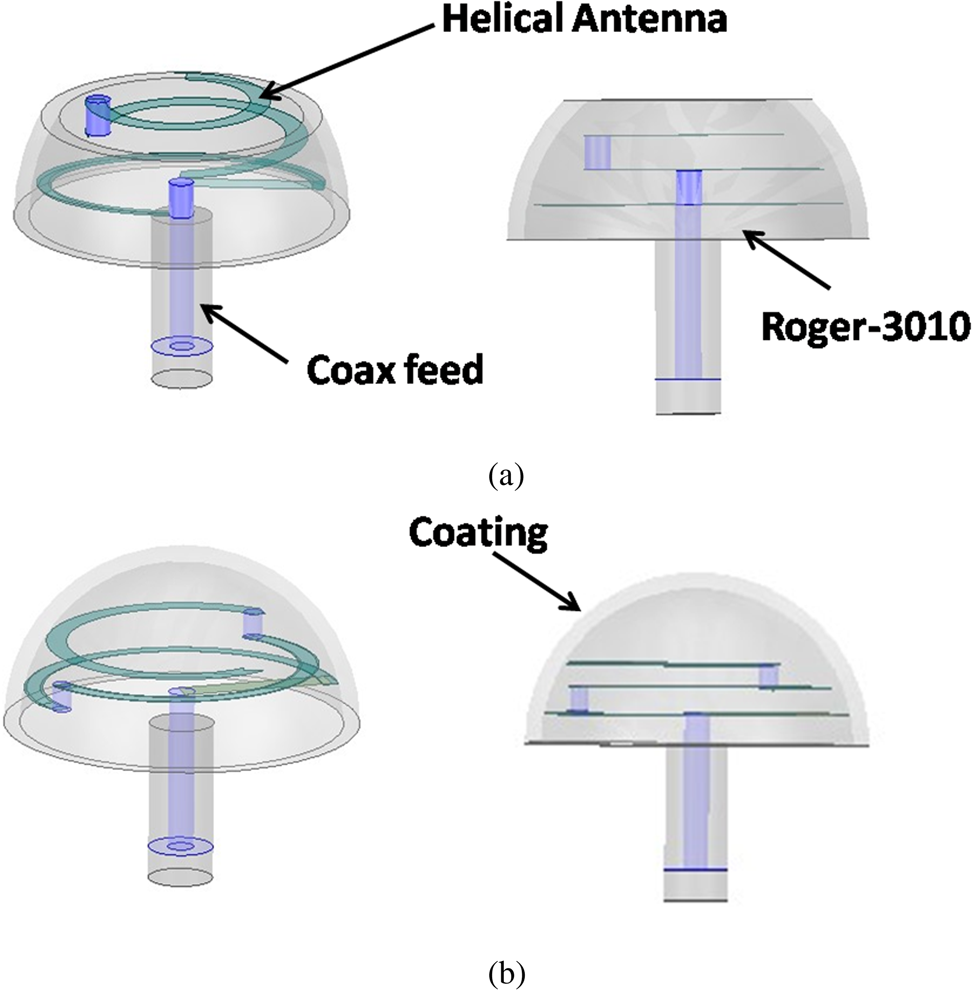

Ref. [Reference Lee, Chang, Kim and Yoon5] demonstrates a conical spiral-shaped antenna in the tip of the capsule fed with 50 Ω coaxial line was proposed by Sang Heun Lee et al., as shown in Fig. 4. The proposed compact antenna with a radius of 10 mm and a height of 5 mm could be easily enclosed in a small capsule. The proposed ultra-wideband (UWB) antenna has an impedance bandwidth of 418–519 MHz. An advanced version of the same is presented in reference [Reference Liu, Guo and Xiao6], as shown in Fig. 5. Here, a coaxial probe is again used for feeding the antenna. Three different open loops are present on separate 100 μm thick layers of microwave substrate (Rogers RO3010) with permittivity of 10.2 and loss tangent of 0.002. This structure is a potential choice for high data-rate swallowable WCE systems with wide bandwidth ranging from 2.3 to 3 GHz.

Fig. 4. 3D-structure of conical-shaped spiral antenna based on the model demonstrated in [Reference Lee, Chang, Kim and Yoon5].

Fig. 5. (a, b) 3D structures of the CP multilayer helical antenna based on the model shown in [Reference Liu, Guo and Xiao6].

Further, an antenna with helical structures composed of series of small loops and dipoles was suggested making certain that the external occupied area of the capsule stays small even though the electrical length of wires seems to be extended. It has been seen in this experiment that chances of detuning is also less in varying dielectric property of the body tissues [Reference Faerber, Cummins and Desmulliez7]. It also has the advantage of maintaining the antenna geometry with easy fabrication along the pill curvature. Designing such an antenna is possible at the required operating frequency which is a lower resonance frequency of 433 MHz offering higher radiation efficiency. The lower resonance frequency makes it less susceptible to signal attenuation (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Generalized structure of the spiral helical antenna.

Research over the years has shown that embedded and conformal designs are suitable choice for capsule antennas. Embedded and conformal antennas are placed inside the cavity and on the walls of the capsule, respectively. The advantage of PIFA which was invented in 1950 lies in its low profile, light weight, flexibility and ability that it can be easily integrated into equipment. It can also receive both vertical and horizontal polarized waves. A flexible PIFA is proposed by Islam et al., which operates in the ISM band (2.4–2.4835 GHz) [Reference Islam and Arifin8]. For compact design Copper and Rogers RO-3010 are selected as the patch and substrate material, respectively. This antenna with dimensions 9.48 mm × 7.8 mm × 0.735 mm, performs reliably under bent conditions due to the very small thickness (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. PIFA geometry.

A circular-shaped miniaturized antenna with a diameter of 10 mm and complex input impedance in the ISM frequency band (2.45 GHz) is proposed for ingestible application, as shown in Fig. 8 [Reference Bao and Guo9]. Using the meandered line structure the size is reduced significantly. Tuning of the input impedance over a very wide range is possible with an π-match network and the coupling structure between the antenna end and its feed point. Thus, there is no need for an added matching circuit, to make certain that the antenna and the transceiver are conjugate matched directly.

Fig. 8. 3D-structure of the miniaturized circular-shaped antenna using π-match based on the model in [Reference Bao and Guo9].

Size miniaturization and the conductive bio-fluid environment become the major sources of poor efficiency in such type of bio-medical antenna. By altering the electrical length of the antenna as well as implementing the metamaterial in antenna design can mitigate such inherent issues involved in antenna engineering. These metamaterials are not naturally available in nature and these are artificially engineered which makes the antenna systems electrically small as well as efficient. Thus a monopole wire patch antenna embedded with a double C shaped resonant (DCR) structure preferable for ingestible WCE system is proposed [Reference Mary Neebha and Nesasudha10] as shown in Fig. 9. By introducing the metamaterial, an antenna operating at a dual-frequency can also be constructed under some conditions. The proposed antenna is suitable for capsule endoscopy systems because of its compact structure, easy fabrication procedure, good radiation characteristics and it is cost-effective as well.

Fig. 9. DCR structure loaded monopole wire patch antenna [Reference Mary Neebha and Nesasudha10].

Literature survey shows a variety of conformal antenna designs where the geometry is placed on the wall of the capsule allowing the area within the capsule to be occupied by other capsule components. The conformal outer-wall loop antenna proposed by S. Yun et al. effectively uses the capsule's outer surface which makes it appear larger than the antennas placed interior to the capsule. This proposed architecture ensures that volume is minimized while radiation performance is improved [Reference Yun, Kim and Nam11]. The capsule has an inner and outer radius of 5 and 5.5 mm, respectively, with a length of 24 mm. It provides omni-directional UWB characteristics of 260 MHz. Fig. 10 shows such a conformal antenna (generalized diagram)

Fig. 10. Structures of a conformal outer-wall loop antenna.

A UWB conformal trapezoidal-shaped strip excited hemispherical dielectric resonator antenna (DRA) was proposed as WCE antenna, as shown in Fig. 11 which can be conformed over the capsule dome unlike the cylindrical capsule surface [Reference Wang, Wolf and Plettemeier12]. The bandwidth of the design ranges over 3.1–4.8 GHz with FBW (fractional bandwidth) of 43%. Instead of having the traditional probe, a more energy-efficient conformal strip is used here for excitation which results in the electric current distribution on the whole DRA surface.

Fig. 11. 3D-structure of a capsule dome with conformal hemispherical DRA based on the prototype shown in ref [Reference Wang, Wolf and Plettemeier12].

A compact, conformal outer-wall loop antenna operating at 433 MHz was proposed by Miah et al. [Reference Miah, Khan, Icheln, Haneda and Takizawa13]. The flexible 100 μm thick Preperm-255 is used as the substrate which allows easier bending and wrapping around the capsule. The antenna exhibits additional resonance at 905 MHz. The maximum realized gain of the antenna is −35 dBi at the resonant frequency and the gain approximately remains stable over different orientations of the capsule. In spite of variations in the antenna resonance across varying human tissue types, the reflection coefficient of the antenna remains below −10 dB over 336–1065 MHz. Fig. 12 shows a conformal antenna with balun structure.

Fig. 12. WCE antenna wrapped around the capsule and test jig with balun structure [Reference Biswas, Karmakar and Kumar31].

An UWB conformal capsule slot antenna was proposed by Bao et al. The simple design provides a constant impedance matching feature with impedance bandwidth ranging between 1.64 and 5.95 GHz (113.6%), as depicted in Fig. 13 [Reference Bao, Guo and Mittra14]. The proposed antenna is wrapped around the inner wall of a capsule shell as it a better choice over conformal outer-wall placement resulting in a comparatively high specific absorption ratio (SAR), low efficiency and low gain.

Fig. 13. Architecture of a capsule with conformal inner-wall antenna based on the model in ref [Reference Bao, Guo and Mittra14].

The dielectric properties of the bio-tissues are changed dynamically with frequency. The human GI tract comprises of varying tissues and the change in its properties has a considerable impact on the capsule performance as it travels along the human digestive tract. Thus to overcome the adverse detuning effects from the proximity with the bio-tissues or the internal components of the capsule, wideband design is preferable over typical narrowband design. Along with that, keeping in view of SAR-limit, and other radiation limited reasons, few researchers preferred the inner wall design of the antenna. One such design is shown in Fig. 14.

Fig. 14. 3D structures of the antennas of two sets of conformal inner-wall capsule antennas based on the model demonstrated in ref [Reference Bao, Guo and Mittra14].

WCE application also introduces “slot antenna” having wider bandwidths. The presence of slots in the patch design ensures additional resonances which help in resolving the detuning issue. Further bandwidth enhancement is possible with a slot-loop design which is a complementary form of a loop antenna. Another compact, conformal inner-wall differentially fed antenna fabricated on ultrathin flexible polyimide substrate operating at 915 MHz is proposed [Reference Zhang, Liu, Liu, Cao, Zhang, Yang and Guo15]. The polyamide substrate is easily wrapped around the capsule making it compact, occupying very less area but without compromising with the performance. The miniaturization is obtained by notching meandering slots with volume of only 30 mm3 (Fig. 15).

Fig. 15. Arrangement of the conformal differentially fed antenna over the capsule structure.

The conformal chandelier meandered dipole antenna was suggested by P. Izdebski et al., as a suitable choice for WCE system [Reference Izdebski, Rajagopalan and Rahmat-Samii16]. Miniaturization is achieved by its vector current alignment. With this method, significantly the total wire length is reduced but maintaining the fixed resonant frequency of the whole structure. Because of this uniqueness in the miniaturization technique along with its Omni-directional radiation pattern, conformal geometry, tunability and polarization diversity, it is preferred over various other options. The operating frequency of this antenna is in the WMTS band around 1395–1400 MHz. There is an additional series resonance along with parallel resonance that is dual resonance is supported as it is offset-fed in a certain way with two different sized arms. This additional resonance ensures better matching at the required frequency. But as the capsule traverses, detuning might happen due to the body conductivity and the varying electrical properties of the tissues in various parts of the human digestive tract (Fig. 16).

Fig. 16. Structures of the meandered dipole antenna.

Another UWB conformal antenna with bandwidth ranging from 0.377 to 1.13 GHz on 0.1 mm thick flexible polyamide (ɛr = 3.5, tan δ = 0.008) substrate initially with an inverted-F structure having a resonant frequency of 490 MHz for wireless endoscope applications is presented by Shang et al. is suggested [Reference Shang and Yu17]. L-shaped open slot can be introduced between the short location and the feeding location on the ground to generate an additional resonant frequency at 2.89 GHz, as explained in Fig. 17.

Fig. 17. Structures of the conformal UWB antenna on flexible polyimide [Reference Shang and Yu17].

Unlike a single-band, a compact multi-band conformal antenna for WCE application was proposed by Yousaf et al. The five different bands covered are MedRadio (401–406 MHz), ISM (433.1–434.8, 868–868.6, 902–928 MHz), and midfield (1200 MHz) to perform various functions like biotelemetry, power saving, and wireless power transfer (WPT) concurrently [Reference Yousaf, Mabrouk, Faisal, Zada, Bashir, Akram, Nedil and Yoo18]. Flexible Rogers ULTRALAM having a thickness of 0.1 mm is chosen as the substrate for the antenna which is wrapped around the inner wall of a capsule (Fig. 18). Considerable reduction in size is achieved by the introduction of the via holes or shorting-pins and open-ended meandered slots in both radiator and ground plane. The antenna dimensions are19 mm × 15 mm × 0.2 mm with a volume of 57 mm3 in the flat form and only 48.98 mm3 in the conformal form. The bandwidth of the proposed antenna in a homogeneous muscle phantom varies as 27.46, 13.2 and 5.42% bandwidth at the frequencies 402, 915 and 1200 MHz, respectively.

Fig. 18. Structures of the multi-band compact conformal antenna [Reference Yousaf, Mabrouk, Faisal, Zada, Bashir, Akram, Nedil and Yoo18].

Fractal engineering is widely used in the antenna field, especially in the case of printed versions. It is because miniaturization is associated with wideband characteristics due to the self-similar and space-filling inherent characteristics. The space-filling property makes the antenna appear electrically small resulting in size reduction and the self-repeating behavior with reduced size facilitates broad-banding nature. Various types of fractals are being used for this purpose, like-Minkwoski, Hilbert curve type, etc. [Reference Biswas, Karmakar and Chandra20, Reference Biswas, Karmakar and Chanda21, Reference Biswas, Karmakar and Kumar31]. A10 × 10 mm2 fractal UWB omni-directional microstrip patch antenna (MPA) which is pentagonal in structure with star-shaped slots inside the patch was proposed by Nizar Hammed et al. [Reference Hammed, Fayadh and Farhan19]. Here fractal geometry up to 4th iteration is suggested which provides a wide bandwidth of 5.1 MHz along with a high data rate. In recent times, three numbers of fractal-based miniaturized antenna architectures have been reported [Reference Biswas, Karmakar and Chandra20–Reference Merli, Bolomey, Zurcher, Corradini, Meurville and Skrivervik22]. Compact size, broad-banding nature and Omni-directional irrespective of the position of the capsule inside the GI tract make these designs attractive choices for WCE application. Fig. 19 collectively shows all the fractal engineering-based WCE antennas.

Fig. 19. Structures of the fractal antennas (a) pentagonal-shaped fractal micro strip patch antenna (MPA) [Reference Hammed, Fayadh and Farhan19], (b) Minkwoski fractal antenna on FR-4 [Reference Biswas, Karmakar and Chandra20] and (c) Minkwoski fractal antenna on LCP [Reference Biswas, Karmakar and Chanda21].

A10 × 10 mm2 wide-band fractal elliptical-shaped antenna was proposed recently having two different sizes of circular slots on FR4 substrate, resonating at 5.78 GHz, as depicted in [Reference Alreem, Hammed and Fayadh24]. Here fractal geometry up to the second iteration is suggested which provides a wide bandwidth. The proposed antenna has the |S 11| values of −41.25 dB having an impedance bandwidth of 72.95% inside the human GI tract (Fig. 20).

Fig. 20. Architecture of the fractal engineering miniaturized antenna based on structure in [Reference Alreem, Hammed and Fayadh24].

A first-ever dual-circular-polarized wideband conformal inner wall antenna (Fig. 21) for WCE applications at 402, 915, and 2.4 GHz with a high-data rate was recently proposed by Basir et al. [Reference Basir, Zada, Cho and Yoo25].The proposed antenna is fabricated on a flexible polyamide substrate and has dimensions of 32 mm × 10 mm × 0.025 mm with a volume of 8 mm3. It provides impedance bandwidths of 236.2, 104 and 55.4% and peak gains of −29.71, −28.7 and −20.8 dBi at frequencies of interest 402, 915 MHz and 2.4 GHz, respectively.

Fig. 21. Architecture of the dual-CP conformal antenna based on the structure demonstrated in [Reference Basir, Zada, Cho and Yoo25].

A novel Omni-directional hemispherical DRA with dual-polarization having a resonating frequency of 2.45 GHz for WCE application is proposed by J. Lai et al. in the latest study which has a different radiation principle than other traditional antennas, as shown in Fig. 22 [Reference Lai, Wang, Zhao, Jiang, Chen, Wu and Liu26]. The bandwidth of the proposed antenna is around 200 MHz (2.36–2.56 GHz). Surface wave loss is absent in the case of a DRA and electromagnetic radiation is produced across the surface except the ground plane ensuring a very good radiation efficiency of 15–18%.

Fig. 22. WCE system in dual-polarized DRA antenna [Reference Lai, Wang, Zhao, Jiang, Chen, Wu and Liu26].

Miniaturization along with system-on-chip (SoC) concepts attracts the popular substrate silicon as a viable candidate for WCE antenna, as demonstrated in Fig. 23. Keeping in view of system integrity, the antenna (in flat form) is placed with the capsule structure. As the capsule traverses through the human body, stable performance of the WCE system irrespective of varying properties of the bio-tissues and capsule position is preferable along with wide-band omni-directional characteristics.

Fig. 23. WCE antenna realization using silicon substrate [Reference Biswas, Karmakar and Chanda23].

Biocompatibility issues and safety consideration

Biocompatibility

Since the capsules are ingested within the patients, the materials used must comply with extremely strict requirements and they should be biocompatible for the entire device lifetime. This can be done by either using biocompatible materials in the fabrication of the antennas or by using a thin layer of the same to coat the antenna as shown in Fig. 24 below. The most commonly used biocompatible materials are Teflon, MACOR® and ceramic alumina. A special grade of the polycarbonate Makrol on was recently used which is mechanically strong and safe, ensuring a trouble-free examination. Biocompatible material thickness can also influence antenna performance. Dielectric materials with the same electrical properties as the biocompatible materials can be used as an alternative for fabrication in case if certain biocompatible materials are unavailable.

Fig. 24. Miniaturized antenna with bio-compatible materials.

In [Reference Kiourti and Nikita27], the use of superstrate and substrate of PDMS have in an antenna fabrication embedded in silicone can be seen. Ceramic can be considered as the most suitable material for use. Materials like alumina and zirconium dioxide are also popular choices. The antenna can be insulated with a thin layer of low-loss biocompatible encapsulation with materials like PEEK, zirconia and Silastic MDX-4210 Biomedical-Grade Base Elastomer. Zirconia having certain electrical properties emerges as a better option for biocompatible insulation from an electromagnetic perspective (Fig. 25).

Fig. 25. Biocompatibility for implantable/ingestible Antennas: the addition of a superstrate coating.

Safty

Specific absorption rate (SAR) is an important performance parameter that is used to measure the amount of electromagnetic energy absorbed by the unit mass of human tissue [Reference Miah, Khan, Icheln, Haneda and Takizawa13]. SAR depends on the material conductivity, mass density and induced electric field. It is calculated by taking an average of over 1 g or 10 g of bio-tissue in the form of a cube. As per C95.1–2005 standard, SAR is regulated by IEEE with respect to 1 g (avg.) and 10 g (avg.) which are limited to 1.6 and 2 W/kg, respectively. Since the antennas are made of non-biocompatible materials, to ensure safety they should be coated with a biocompatible layer which also provides isolation from the moist and corrosive environment of the human digestive tract.

Power delivery to the capsule

Battery

The WCE system consists of various electronic components like a light source, imaging camera, telemetry unit and battery, out of which the battery is the most space-occupying element. The antenna performance and impedance bandwidth should be stable even in presence of the battery and irrespective of the radius, height and position of the battery inside the capsule. Among all the battery specifications, radius mostly affects the performance. To extend the WCE applications, the battery lifetime should be maximized. To overcome the limited lifetime of a battery, recently a technology called “wireless power transfer (WPT)” is emerging in WCE system.

Wireless power transfer

The limited energy budget of the endoscopy capsule battery severely restricts the system performance in terms of operating time, resolution, and so on. For example, the battery-powered capsule can operate approximately 6–8 h. However, for some patients, the capsule might stay in the digestive tract for more than 8 h. In this context, WPT is a significant technical breakthrough. It can offer an unlimited remote power source and improve system's overall performance metrics. Recent literature reveals that significant efforts are being paid for developing efficient WPT systems for various bio-medical micro-systems [Reference Noormohammadi, Khaleghi and Balasingham29, Reference Dey, Ashour, Shi and Sherratt30, Reference Sun, Xie and Wang32].

Commercially available WCE system runs with 25 mW power with generally two numbers of coin-shaped batteries. To replace this power system, WPT should be sufficient to deliver that much power out of the body maintaining the safety limits. In-vitro test is necessary to validate the actual performance of WPT link in the WCE environment, because the power transferring efficiency will drastically fall within biological tissue [Reference Basar, Ahmad, Cho and Ibrahim33]. Inductive coupling or near-field communication (NFC) will be most probably a viable solution for the same.

As per authors’ knowledge, the development of WPT in this field is still in a nascent phase. The safety aspect of using it is another concern and practical research with field trials on this aspect considering advanced WCE system is still limited.

Locomotion and localization

Locomotion

As of now, the capsule in the existing WCE system traverses through the human GI tract after being swallowed under the effect of natural peristalsis, and hence the capsule movement is passive. Also the capsule's position cannot be determined in this method. So in place of passive (non-controlled) locomotion, we need to use the active (controlled) locomotion. A new technique with the use of magnetic actuator was proposed by Sendoh et al. [Reference Sendoh, Ishiyama and Arai28] in this respect.

Localization

The localization system consists of N receiver antennas (N ≥ 3 for 2D and N ≥ 3 for 3D localization) placed at some pre-defined positions around the patient's abdomen which collects signals transmitted from the capsule as it travels through the GI tract. In the first step of the three-step localization algorithm, the distance between the receiver and the capsule is determined. In the next step, the determined distance from the previous step is used to calculate the initial coordinates of the capsule with the help of the linear least-squares method. Using non-linear least-squares method and the previously estimated initial coordinates more accurate estimation of the capsule coordinates is done in the final step.

First, safety of the locomotion mechanism of the WCE system has to be tested before it can be practically employed for disease diagnosis. The active medical robot loaded with multi-functions like locomotion, localization, telemetry, powering, and diagnosis/treatment tools is the optimal diagnostic and therapeutic instrument for GI diseases. With the development of MEMS (Micro-electro-mechanical systems), this can be realized. A prototype of this kind having a radius of 5 mm and a length of 10 mm is proposed by Korean IMC [Reference Pan and Wang1]. It has the capability to move forward/backward, stop at the point of interest, anchor itself to the wall of GI tract and diagnose or perform therapeutic procedures with external control.

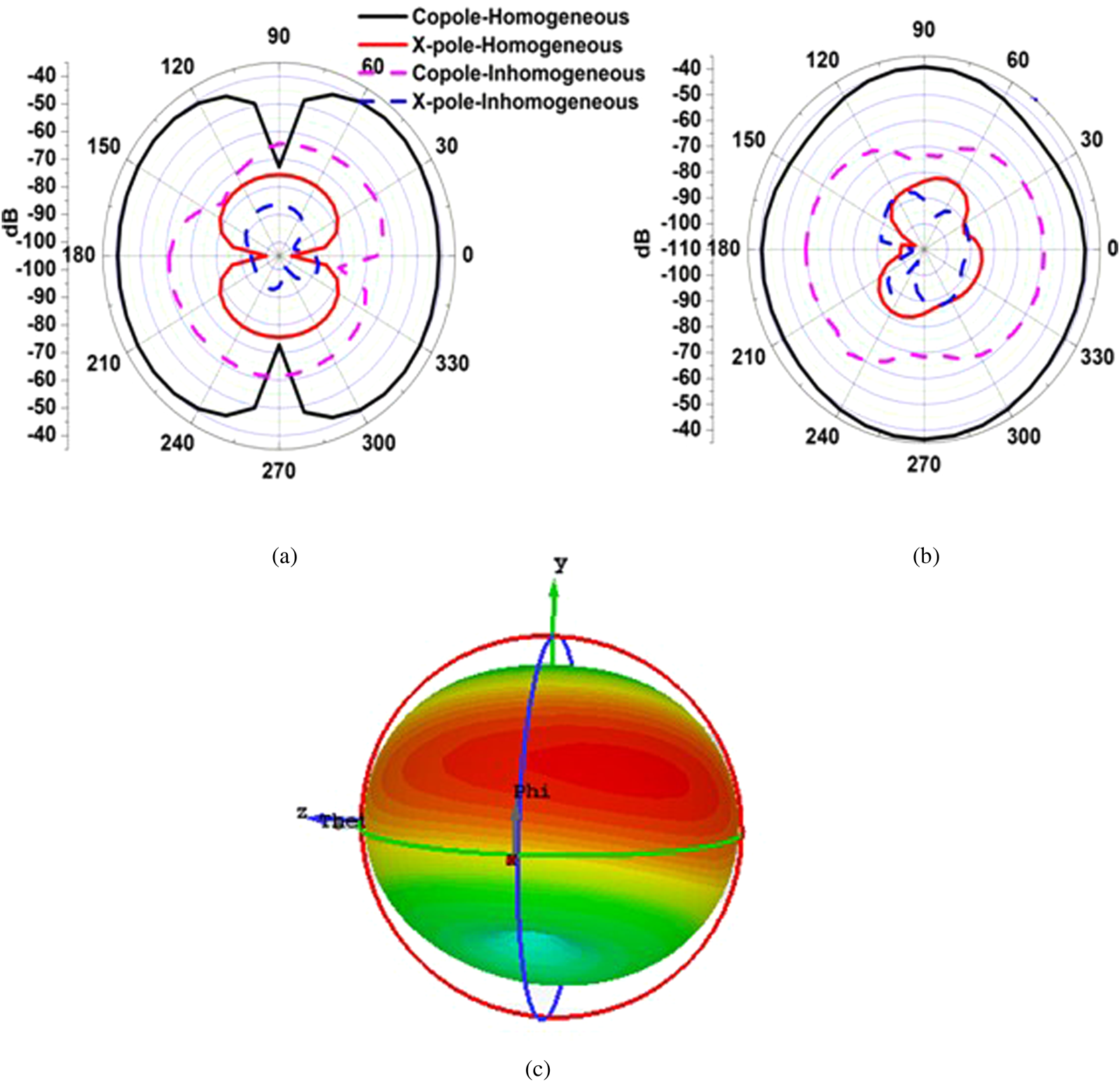

Radiation pattern

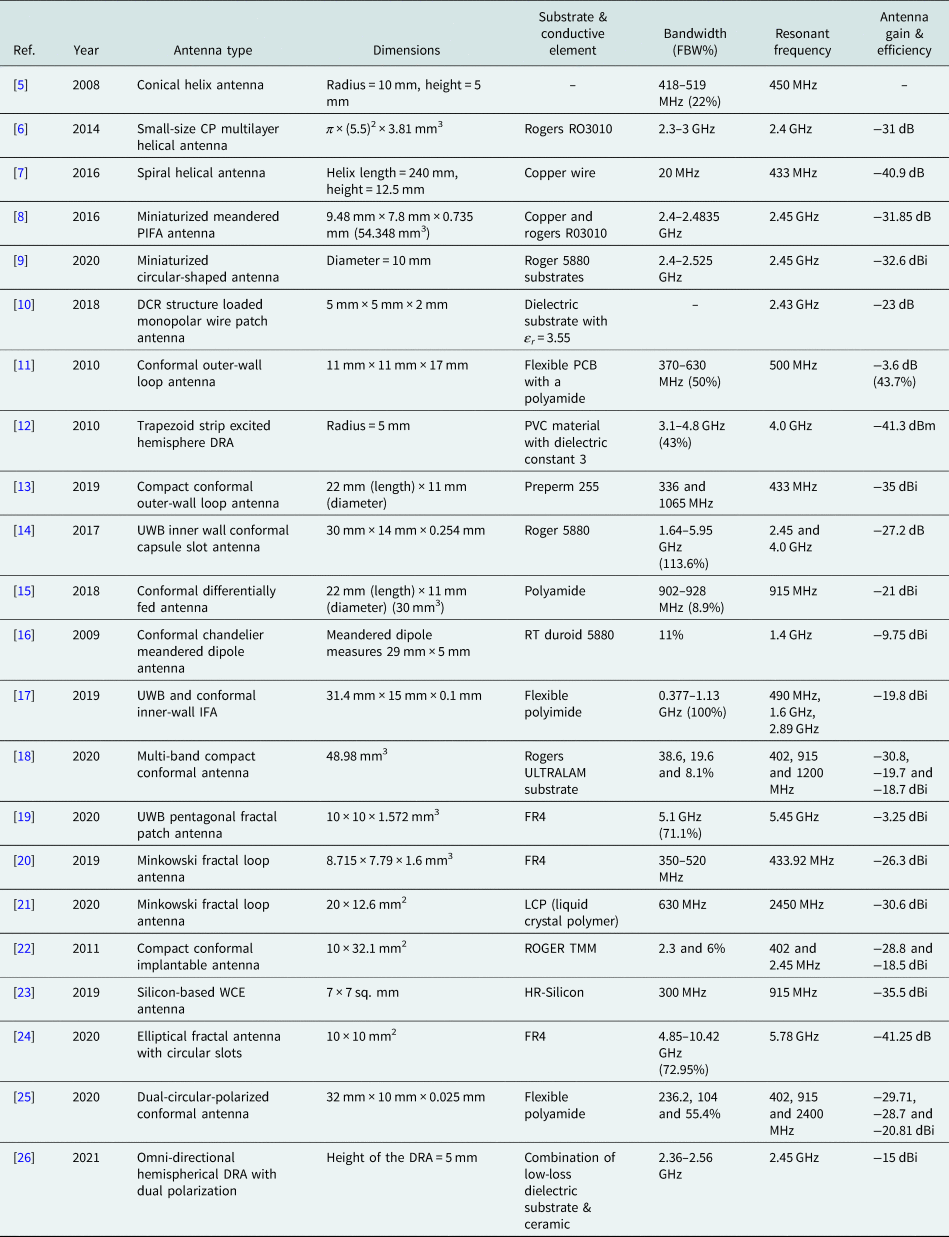

Previous sections of this manuscript deal with the antenna architectures along with their bio-compatibility issues and safety limits for final usage. One very important concern of this type of antenna designing is its radiation pattern and achieving UWB feature irrespective of the variable bio-tissue nature inside the human body during the operational periods. Usually, omni-directional pattern is desirable for such an antenna. Although perfect omni-directional nature is not realizable through practical means but best efforts are put in obtaining so. One such far-field radiation pattern is depicted in Fig. 26. Table 1 summarizes various other antenna performance metrics, like gain, return loss, bandwidth, polarization nature and, finally radiation efficiency for a variety of WCE antennas.

Fig. 26. Radiation pattern of an WCE antenna at 915 MHz in (a) E-plane, (b) H-plane and (c) 3D-visualization of gain.

Table 1. Comparison of reported WCE antennas.

Conclusion

Currently WCE system provides an efficient painless non-invasive way of detection/diagnosis of various diseases/anomalies of the human GI tract. Using transceiver chips, optimized power consumption and improved data rate can also be ensured. With the introduction of a user interface in the future, the physician will be able to detect the capsule location, control its movement and direct it toward the point of interest for further analysis. To overcome the bottlenecks of the existing WCE system research is going on to develop multifunctional, miniaturized, medical robots at present. In this regard, along with the study of UWB, Omni-directional, optimized, compact, efficient transmitter antenna preferably conformal to the inner wall of the capsule, research is focused to develop power-efficient, high data rate, mixed-mode ASIC, micro-actuation system which is essential for the development of next-generation endoscopes. Table 1 summarizes various such research outcomes of recent times. In the next-generation capsules, the incorporation of artificial intelligence, user interface along with mini-surgical tools is anticipated which will enhance the WCE technology even more.

Sreetama Gayen obtained her bachelor's in 2016 from the St. Thomas’ College of Engineering & Technology, Kolkata, India in electronics & communication engineering. She is currently pursuing her master's in microwave communication from the Indian Institute of Engineering, Science and Technology, Shibpur, India.

Sreetama Gayen obtained her bachelor's in 2016 from the St. Thomas’ College of Engineering & Technology, Kolkata, India in electronics & communication engineering. She is currently pursuing her master's in microwave communication from the Indian Institute of Engineering, Science and Technology, Shibpur, India.

Balaka Biswas obtained her Ph.D. degree from Jadavpur University, Kolkata in the year 2018 with DST-INSPIRE fellowship. Her field of research is the design and development of several ultra-wide band antenna using fractal geometries. Currently she is working toward her post-doctorate research in IISER, Mohali. She was also working as a senior research associate under scientist pool scheme at CSIO-CSIR, Chandigarh with the collaboration of SCL, Mohali for 3 years. She has more than 5 year of academic experience and 20 publications in reputed SCI listed international journals and international and national conferences. Her recent research is in the development of electrically small antennas for bio-medical application. She serves as a reviewer of different reputed international journals such as IEEE Access, IEEE Transactions on Antenna Propagation, AEUE International Journals, MOTL, Frequenz, Journal of Electromagnetic Waves and Applications etc. She is a life member of IETE, ISSE and Indian Science Congress Association.

Balaka Biswas obtained her Ph.D. degree from Jadavpur University, Kolkata in the year 2018 with DST-INSPIRE fellowship. Her field of research is the design and development of several ultra-wide band antenna using fractal geometries. Currently she is working toward her post-doctorate research in IISER, Mohali. She was also working as a senior research associate under scientist pool scheme at CSIO-CSIR, Chandigarh with the collaboration of SCL, Mohali for 3 years. She has more than 5 year of academic experience and 20 publications in reputed SCI listed international journals and international and national conferences. Her recent research is in the development of electrically small antennas for bio-medical application. She serves as a reviewer of different reputed international journals such as IEEE Access, IEEE Transactions on Antenna Propagation, AEUE International Journals, MOTL, Frequenz, Journal of Electromagnetic Waves and Applications etc. She is a life member of IETE, ISSE and Indian Science Congress Association.

Ayan Karmakar obtained his M. Tech (electronics & telecom engineering) degree from NIT-Durgapur. Currently he is working in SCL/ISRO, Chandigarh as a scientist-SE. His research interests include the design and development of various passive microwave integrated circuits and antennae using silicon based MIC, RF-MEMS and THz-technology. He has authored one technical book named “Si-RF Technology” from Springer and has more than 40 publications in refereed journals and conferences, He serves as a reviewer in top-tier international journals, such as IEEE Access, RF-MiCAE, Springer, EJAET, etc. He is a fellow of IETE and a life member of the Indian Science Congress Association and ISSE.

Ayan Karmakar obtained his M. Tech (electronics & telecom engineering) degree from NIT-Durgapur. Currently he is working in SCL/ISRO, Chandigarh as a scientist-SE. His research interests include the design and development of various passive microwave integrated circuits and antennae using silicon based MIC, RF-MEMS and THz-technology. He has authored one technical book named “Si-RF Technology” from Springer and has more than 40 publications in refereed journals and conferences, He serves as a reviewer in top-tier international journals, such as IEEE Access, RF-MiCAE, Springer, EJAET, etc. He is a fellow of IETE and a life member of the Indian Science Congress Association and ISSE.