Introduction

The study of legal scholarship is an important task, not only for understanding the contribution of that scholarship to the development of positive law, but also to help understand the development of law as an academic discipline. In looking at the legal scholarship in Australia, there has been some review of scholarship,Footnote 3 but mostly as part of the considerable, though uneven, interest in Australian legal history. Notable exceptions are works by Chesterman and Weisbrot,Footnote 4 Barties,Footnote 5 SmythFootnote 6 and Murray and Skead.Footnote 7

The Australian legal academy has struggled as a late comer among Anglophone jurisdictions in developing a robust legal academyFootnote 8 and more recently, to position itself between the pressures of the institutions of higher education, the profession and the state.Footnote 9 These historical antecedents have maintained a particular pressure on Australia's legal scholarship to focus on black-letter, positive law. There is little empirical evidence, however, as to whether this positivist focus has been carried into the legal scholarship as represented in the academic journals, nor is there information on the areas of law which dominate the pages in those journals. Further, in response to the positioning of law teaching in universities, with their own focus on research apart from professional training, there is little knowledge of what the contribution of legal scholarship has been to the Australian university or beyond. To gain some insight into the position of legal scholarship in Australia, we examine and analyze the Sydney Law Review (SLR) as a case study of Australian legal scholarship.

We present our study in the five following sections. Section 2 offers a background and rationale for the study. Section 3 offers a justification for using citations to gain insight into the impact of academic law research to answer our three research questions: What areas of law are published more frequently? What methods of legal scholarship are more frequently used? What is the impact of the legal scholarship in the SLR? Section 4 sets out the research methodology and Section 5 presents the findings along with further meta-analysis. Section 6 offers our discussion and conclusions.

Background and Rationale

Australian legal scholarship, like legal scholarship in most English-speaking countries other than the USA with its student edited journals, is largely published in peer-reviewed journals. Accordingly, our research of Australian legal scholarship draws upon peer reviewed Australian law journals, which while often using students as sub-editors like the American system, the review and selection remains largely with the academics who run the journals.

Prior studies of Australian scholarship are somewhat peculiar in terms of review and assessment of scholarship: studies by Smyth,Footnote 10 Farrell,Footnote 11 Murray and Skead,Footnote 12 all take a personal focus. Their interest and focus is on authorship rather than on the substance of what is being published. This authorial focus leaves unanswered important questions of what topics are being researched and published and what methods and approaches are being used to advance knowledge. Without a clear sense of topics and methods it is difficult to understand the development of the discipline.

For a country of its size, for law, as largely a jurisdiction-based study depends on population size, Australia has a surprisingly large number of journals dedicated to law. A recent count placed the number at 157 journals. Among this group, Australia's leading general law journals are the Federal Law Review, Melbourne University Law Review, UNSW Law Journal and Sydney Law Review. These four journals of the leading law schools are arguably the outlets for the leading legal scholarship in the country: they are the only journals positioned at the top of all three of Australia's main journal ranking systems that take account of law,Footnote 13 namely, the Council of Australian Law Deans, the Excellence in Research Australia and the Australian Business Deans Council.Footnote 14 Accordingly, an investigation into the legal scholarship in Australia would do well to work within this group, and could reasonably expect to find intellectual leadership in terms of innovation in terms of topics and methods.

Although there are a number of different potential approaches to any such investigation,Footnote 15 including a broad survey of all four journals, we have decided to take a case study approach. Given the exploratory nature of the investigation, methodologically, we believe a closer examination of a particular case provides greater insight into the nature of the phenomenon under consideration, namely Australian legal scholarship, necessary at an early stage than a broader quantitative study.Footnote 16 This method, of course, has significant limitations, leaves much unexplored and many questions unanswered. A basic limitation is that like all case studies, it may not be representative or at all generalizable. By definition, a case study is not representative. Rather it is a method that aims to provide depth at the obvious expense of breadth.

Among the four potential journals, based on the length of publication, involvement of academics in its management and the aforementioned leading status, we determined that examining the scholarship in the Sydney Law Review (SLR) would be most appropriate. Of the four, it has the longest continuous history under its current masthead. It has been publishing as the Sydney Law Review since 1953. Further, it claims to be: “[among] Australia's most eminent academic law journals… devoted to publishing exceptional, timely articles that make an innovative contribution to legal scholarship and are of interest to a wide audience.”Footnote 17 Although many law journals may make the claim, the SLR is the law journal most highly cited by the High Court of Australia.Footnote 18

Over the last 67 years, interestingly, there has been no published review analyzing the SLR's articles identifying the focus of leadership among Australian legal scholars, nor what has captured the attention of the journal's editors and readers, nor how these contributions have fared in the intellectual life and development of the legal academy and beyond into the profession and society more broadly. Indeed, correspondence from the editors of the journal indicated that such a review is not considered legal scholarship and the journal would not expect to publish such. Nevertheless, such an analysis is important because it identifies the contribution of and direction from the law academy and facilitates consideration of what contributions law journals generally make to the academy and society at large.

In that regard, the burden on law journals is greater than the burden found on most scholarly journals, for in addition to the normal role of scholarly journals contributing to disciplinary knowledge, law journals are expected to be a forum for analysis, critique, and proposals for reform of the nation's laws and to provide insight into the practical problems faced by members of the profession and the courts.Footnote 19 These are not mutually exclusive obligations, for as RP Austin noted, quoting Rodell: ‘if we accept (as I do) that the object of such reviews is to publish writing on and about law that augments the general body of human knowledge, thereby adding to our understanding of law's operation in the world an understanding that may assist in the solution of real, even everyday, legal problems.”Footnote 20 Accordingly, conducting an analysis of the SLR's impact must take account of the dual roles—in the academy and beyond.

This article aims to provide a case study of legal scholarship in Australia by analyzing the content and impact of the SLR taking a sample of the journal's articles over the last ten years. It analyzes all the articles published in that period in terms of areas of law and methods of and approaches to legal research. It then identifies and analyzes the articles that have contributed the most to the SLR's impact over the last ten years, as it is assumed that these articles will contribute most to the shape of the discipline of law in Australia as they become the articles that scholars of the future will cite.

Our research questions are thus:

RQ1: What areas of law are published more frequently?

RQ2: What methods of and approaches to legal scholarship are more frequently used?

RQ3: What is the impact of the legal scholarship in the SLR?

This final question draws together the prior two by considering what strands of research are particularly productive or useful, and proposes areas for future research.

In terms of method broadly, from all articles published in the SLR in the period 2008–2018, we identified those articles that had been cited. We then further reduced our focus to those articles with the greatest impact as measured by citations. We selected from these the complete set of articles that have ten or more citations. This procedure led to a total of 31 of the 257 scholarly articles published between 2008 and 2018 for analysis. Finally, a sampling among these latter articles was considered in some detail to provide a brief critical analysis.

Citations as a Measure of Impact in Law

Citations have long been a measure of the value of knowledge contributions. Their use originates with the legal profession and can be traced back to 1743, when the legal profession started referring to other cases in judgments.Footnote 21 In 1860, there was a significant innovation in the management and use of citations as a result of the publication of the first case citation index. The index became exceedingly popular among lawyers because it helped to establish what the precedent was.Footnote 22

In the academy, the development of the use of citations was slower. The first citation indices were only developed in the 1950s by Eugene Garfield,Footnote 23 which indices were used to provide the platform for newer computerized databases such as the Science Citation Index (SSCI)Footnote 24 and more recent commercial providers such as SCOPUSFootnote 25 and Google Scholar.Footnote 26 Although there are significant pros and cons associated with this approach, also noted in the legal literature,Footnote 27 Google Scholar is the most objective and widely available, and hence will be used in this article.Footnote 28

The common view is that law is not a citation-based discipline. In other words, the value and impact of legal scholarship cannot be assessed exclusively or primarily by reference to scholarly citations. Rather, impact is better assessed by evaluation of specific uses such as a court's use, or reference in a policy or Policy Reform document. While this is certainly correct as far as it goes, it fails to provide sufficient recognition of law as an academic study in its own right which deals in matters of concern globally. As such, use of citations in scholarly literature is important in law but not an all-encompassing metric of the utility or impact of a scholarly article.

Our empirical bibliometric study of Australian legal literature is not unique.Footnote 29 Since the early 2000s, when the Australian government first entered into research assessment exercise, there have been studies utilizing empirical approaches to the discipline of law. At a high level, these studies have been problematic for law as a discipline because of the legal academy's dual role as well as its local, jurisdiction bound focus.Footnote 30 The dual role and local focus has meant that much of the work published in law journals garners little attention beyond Australia's borders. Indeed, why would an American judge working on a case be interested in a critique of Tasmanian tort law, except in the rarest of cases?

At a more basic level, a number of objections can be raised to using journal citation metrics in law. Professor Bowrey, in her recent study of metrics in law, commissioned by the Council of Australian Law Deans, documents the objections and issues carefully and comprehensively.Footnote 31 She notes that in addition to general concerns about the use of citations, as for example the use of unexamined, nominal approaches to citations, there are a number of Australian law specific concerns. In particular she notes that citations studies are “assessing impact with reference to ‘adoption’ of research by end-users.”Footnote 32 She goes on to point out that because of law's political nature, “Adoption of legal research was not considered a sound indicator of the quality of the research, but more related to political fit.”Footnote 33

Further, citations in law, as in other peer-reviewed disciplines miss important contributions in the grey literature. As Tilbury writes

grey literature such as evaluation reports, conference papers, abstracts, dissertations, clearinghouses, discussion papers, briefings, submissions, working papers, blogs and social media…. is not considered ‘quality’ and indeed often dismissed in academia. But should such material be marked down, if it is important to policy and practice? The value of grey literature has been advanced on the grounds that it makes a substantial contribution to public policy, education, commercial innovation and social development.Footnote 34

Such is surely the case in law where major contributions to shaping society can result from the court's adoption of a position or argument set out in a law journal but which may merely count as one citation in Google Scholar.

Finally, Bowrey notes that citations in law as in other disciplines do not tell the whole story. In her words “citation data provide only a limited and incomplete view of research quality.”Footnote 35

These issues and concerns, however, do not mean that citation metrics are useless in law. As Ramsay and Stapledon observe in their citation study of Australian law journals, “It can reasonably be assumed that a citation means an author has read the article and believes it to be of sufficient importance to refer to it in the author's own work.”Footnote 36 Indeed, there are useful historicalFootnote 37 and recent citations studies of Australian legal scholarship.Footnote 38 These studies examine use of legal scholarship by the Australian judiciaryFootnote 39 and Policy Reform CommissionsFootnote 40 through citation counts of scholarly work. These prior studies, reviews, and analyses, however, have a significantly different focus. None of them focus on the areas, methods, themes, and evaluation of specific, leading contributions to identify and evaluate their contribution to Australian legal scholarship. Identifying the areas and methods of scholarship of a leading journal provides insight into how the law discipline is developing, substantively as well as the impact of the contributions the profession and society more broadly at least by one measure. We turn next to consider method.

Research MethodFootnote 41

To answer our questions, a database was created using Harzing's Publish or PerishFootnote 42 software to identify all the articles published by the SLR in the period 2008–2018 and retrieve the citation data. This data was cleaned by checking for duplicates. The approach created data for 257 articles. To develop our profile of the SLR's output, all 257 articles were put into a spreadsheet and categorized by area and method, as explained below, and then ordered by citation count.

The most highly cited articles were then identified and run through Google Scholar to verify citation counts. The citation counts were used to identify the most influential articles as measured by the number of citations and citations per year. We relied on Google Scholar citations because it provides the widest net of citations. Other citation systems like Hein Online, Westlaw and SCOPUS focus on their own stable of journals.Footnote 43 Leading articles were confirmed using the AustLII citation function. Google Scholar data was preferred, however, as it provides “sufficient stability of coverage to be used for more detailed cross-disciplinary comparisons.”Footnote 44 Additionally, the data is freely available and is fast becoming a primary source of citation data as Google Scholar is increasingly being used by academic researchers as a primary search engine.Footnote 45

As noted, two major categories were created: ‘areas’ and ‘methods’ as these categories are fundamental to all legal scholarship. Each area of law is its own domain with distinct concerns, doctrines and rules, and each method responds to both interests of the researcher and the methodological considerations of the research project. Legal scholarship, with its diverse topics and methods is readily divided along these lines. Thus, all 257 articles were analyzed and categorized. Two of the authors individually reviewed and analyzed the 31 articles with ten or more citations and compared their categorizations of the articles with respect to both topic and method. The results were sufficiently similar to quell any concerns as to mis-categorizations or the categories themselves.Footnote 46

Area CategoriesFootnote 47

The SLR articles were initially categorized into the 32 areas of law scholarship (See Appendix) drawn from the Priestley 11, the 11 areas of law that are mandatory subjects of study for admission to legal practice.Footnote 48 To these initial 11 was added another 21 areas in consultation with two other Australian law scholars at the level of Senior Lecturer, representing the main or common areas of law scholarship and practice. Combined these 32 categories were then reduced as the data showed a very high representation of only five areas accounting for nearly 50% of all the articles. These common areas were constitutional, crime, labor, evidence, and administrative law.

While the initial 32 areas reflected the broad range of areas of interest to the law academy and practice, they are not equally represented in the SLR. A critical caveat must be introduced here: much of the knowledge of how the different law journals in Australia work is informal. We do not have any formal information about either the range of topics and methods of submissions to the SLR nor any information about any preferences in the selection decisions as this information is not published. Due to the concentration of publication, only these five areas had sufficient quantity to warrant categories—a situation amenable to statistical analysis.

Methodology and Approach Categories

In terms of method and approach, the following six categories were created, again in consultation with Senior Lecturers in law: Doctrinal, Historical, Law and Society, Policy Reform, Comparative and Miscellaneous. For ease of reference, we refer to these different methods and approaches simply as ‘method.’ The substance and boundaries of each these categories are themselves rich bodies of literature and much legal scholarship includes some mixing of methods. The aim in the creation of these categories is not to deny that there is a mixing of methods; rather, for purposes of analysis it is necessary to create categories which are reasonable and useful. Each of these categories is described next.

Methodological Category 1: Doctrinal

Doctrinal research method is law's foundational method. As a method of research it is ‘[r]esearch which fosters a more complete understanding of the conceptual bases of legal principles and of the combined effects of a range of rules and procedures that touch on a particular area of activity.’Footnote 49 It draws on traditional legal methods of knowledge development, namely the advancement of legal knowledge by argument, using logic, analogy and inference.Footnote 50 The method was long ago described by Holmes in the context of Harvard Law School as follows: “The training of lawyers is a training in logic. The processes of analogy, discrimination, and deduction are those in which they are most at home. The language of judicial decision is mainly the language of logic.”Footnote 51

In terms of a methodological category, it is important to note that doctrinal articles usually have an historical element. They draw on decided cases, whether from the last year or centuries past, to identify and analyze rules and principles. The cases are described factually and either identify the peculiarities of history informing them, or argue that history is irrelevant to the principle or rule derived. Further, doctrinal articles are positivist. This positive view of law is both necessary and appropriate as law is a positive practice: that is to say, working with positive phenomena, the law posited by the legislature and courts. Finally, doctrinal articles seldom end with a mere summary of the existing position. In fact, what often motivates the analysis is the idea that some type of reform which is seen as necessary as a result of the law under analysis which has been demonstrated to be inadequate. Accordingly, although separate method categories have been created for ‘historical’ and ‘Policy Reform,’ it is understood that the broad church of ‘doctrinal’ method includes at least to some degree these two additional categories.

These articles examine, re-examine or re-order areas of law. Westerman describes this type of research as finding ways to fit new problems into the existing legal order using the accepted principles of the relevant area of law.Footnote 52

Methodological Category 2: Historical Method

This category is limited to research that uses historical methods and/or pursuing historical aims. The traditional methods and aims of history are presenting a clear and coherent narrative around events of the past, not necessarily proving causation,Footnote 53 while post-modern histories aim showing discontinuity and incoherence. Our category here embraces both. Where the phenomena under consideration are laws or their historical impact, the study will often aim to provide a new interpretation or solution which could be of utility to understanding a contemporary legal issue.Footnote 54 The main goal of scholars adopting an historical approach is ‘to find evidence, analyze its content and bias, corroborate it with further evidence, and use that evidence to develop an interpretation of past events that holds some significance for the present.’Footnote 55 Articles adopting this method, therefore, looks at the understanding of law through the analysis of historical data.

Methodological Category 3: Law and Society

Law and Society embodies a call for investigation of the interactions between law variously defined and society. It can be traced back to the 1960s and has been described as a field which “emerged from a critique of formal law coupled with a commitment to the progressive values of scientific methods and pluralist politics.”Footnote 56 The method draws upon social science methods to inform legal research. Researchers in this area do so because they consider understanding the social environment as crucial for an understanding of law itself.Footnote 57 Articles categorized here examine the effect of law on social phenomena or, in other words, the social effects of legal rules.Footnote 58

Methodological Category 4: Policy Reform

Policy Reform, while not a method but an approach, provides a useful category—in this case, based on genre. Papers in this methodological category are those papers using a variety of methods the aim of which is directly targeted at Policy Reform.Footnote 59 In other words, Policy Reform or Reform-Oriented Research described as ‘[r]esearch which intensively evaluates the adequacy of existing rules and which recommends changes to any rules found wanting.’Footnote 60 It is often positive in the first instance, examining and critiquing, but then taking on a normative turn, arguing for a range of reasons from theological to economic or ethical as to why the law ought to be changed. Additionally, this category needs to be distinguished from doctrinal research which often includes some recommendations for Policy Reform.

Methodological Category 5: Comparative Law

Several goals are pursued using a comparative approach. With a comparative method, law academics are better equipped to understand both their own local legal system and foreign legal systems.Footnote 61 Furthermore, these scholars can identify new legal issues and new solutions by analyzing other jurisdictions.Footnote 62 Comparative research can also help to achieve a theoretical goal. It extends the application of legal theories to different realms, creating new theoretical approaches to legal issues.Footnote 63 Finally, a comparative method promotes harmonization or unification of different legal systems.Footnote 64

Comparative method refers to the analysis of legal issues considering two or more legal systems or considering the law of two or more nations.Footnote 65 A comparative study, therefore, (1) engages in the study of valid law;Footnote 66 (2) ‘is hermeneutic – it takes the insider's view on all the legal systems studied’;Footnote 67 (3) ‘is institutional in that the knowledge of the law is embedded in the institutional structures of concepts, structures of thinking (especially mental maps) and organizations of the systems in question’;Footnote 68 and (4) ‘is interpretative – in that the comparative lawyer has to interpret both the target legal system and his or her own.’Footnote 69 Articles placed in this category were those explicitly engaged in comparative methods.

Methodological Category 6: Miscellaneous

This category was created for papers that fit readily into any of the previous methodological categories.

Analysis, Results and Discussion

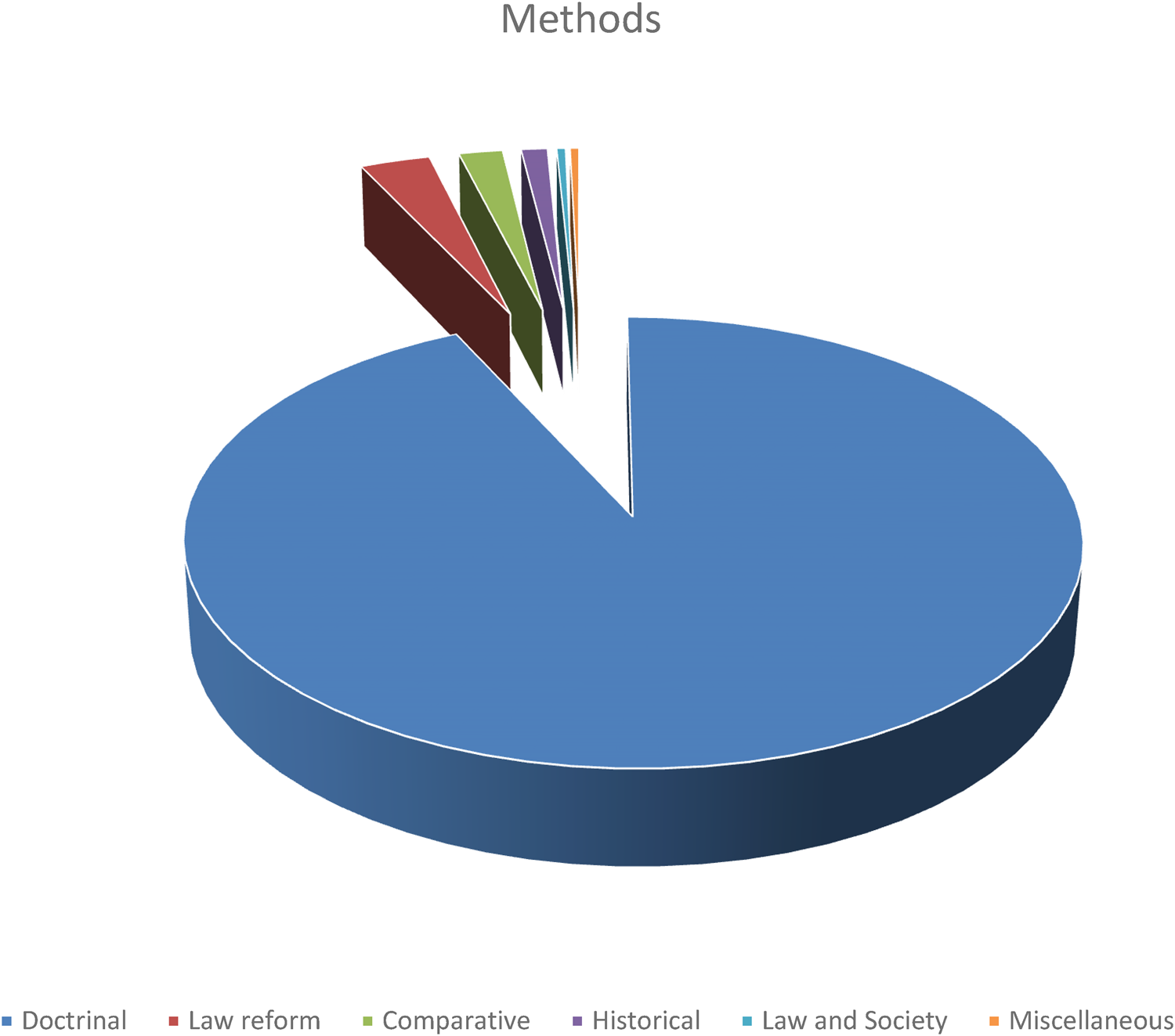

In this section we describe and analyze what the SLR has published. We investigate the journal's focus in terms of area and method and hypothesize possible reasons for these focal points. Overall, the data from the SLR can be presented in two charts: one representing areas and the other representing method. (See Figure 1 and Figure 2 below) What is immediately clear from these figures is the concentrations in both areas and methods.

Figure 1. Areas in the SLR

Figure 2. Methods

Areas

In terms of areas, a significant portion of the articles published by the SLR are in the area of Constitutional law. Combined with the next four area categories of crime, labor law, evidence, and administrative law, nearly half of the publications as represented in the chart are accounted for. (The sixth most common area ‘miscellaneous’, is a category without substantive meaning.) Accordingly, as noted, only five areas will be discussed. Further it should be noted that in some instances, the articles may deal with the interaction between two areas of law. For example, an article may deal with the interaction between human rights and criminal law,Footnote 70 or property law and criminal law.Footnote 71 In these instances, the articles were categorized and counted according to their dominant purpose—to make a contribution to criminal law or the other areas.

It is immediately evident, as noted, that constitutional law is an area of significant research interest among law academics.Footnote 72 Constitutional law may be an appropriate area of scholarly focus as constitutional law is the foundation for all other law. The power of our parliaments to enact legislation, the power of executive action and the powers of the judiciary to adjudicate all stem from our constitution. Accordingly, it could be argued that constitutional law is an appropriate focus of scholarship. Further, given the attention and interests of the courts, and especially the High Court of Australia in constitutional issues, there is a lot to write about; however, there is also reason to question whether constitutional law should be granted so much of a focus. As Bowrey noted in her review of Australian legal scholarship “Whilst it may be that Australian public lawyers are performing at a higher level by producing many more high quality law journal articles than all other Australian legal researchers and areas combined, the apparent ‘over-representation’ of public law suggests serious problems with the methodology used [in prior research] that one would have thought would have warranted further investigation.”Footnote 73 This concern is equally applicable in terms representation of topics in the SLR.

Investigating this focus further through empirical citation analysis provides further insight into academic interest and institutional public interest among the judiciary, in the Policy Reform commissions and in parliament through bills and acts. Further, it allows some exploration of the uptake of ideas in social discourse, and through social interest of addressing matters of concern to the general public who are recipients or subjects of the vast majority of law. We address each in turn.

In terms of academic interest, seven of the 32 most highly cited SLR articles are on constitutional law—discussed in greater detail below. Combined these seven articles account for 147 citations. This level of citation evidences a greater level of interest within the SLR for constitutional articles than any other area of law. Moving to consider the institutional role of the law review, we may ask: does this constitutional concern reflect the concerns of members of the legal profession or society at large? During the period in question, 2008–2018, there has been little broad constitutional debate, beyond the important Uluru Statement, which was not the topic of any article in the period. Nor was it the decade of Mabo, or other precedent setting cases which might pose significant challenges to the constitution or demand reform.

While the Australian Policy Reform Commission has recently issued a call to investigate advancing a range of constitutional reforms, it is not clear that these as a group are the concerns of the law academy as reflected in the SLR's scholarship—as noted by Bowrey above.Footnote 74 The constitutional issues raised by the ALRC are: Indigenous recognition, taxation and federalism. While these are areas in which legal scholars have published in the SLR, there is no trajectory visible or clear line of scholarship on these areas. Constitutional considerations appear to be concentrated on matters associated with the powers of the executive—certainly a matter of concern across Anglo governments broadly—but not of direct or immediate concern to Policy Reform Commissions.Footnote 75 It is not to argue that there have been no significant constitutional issues addressed in the pages of the SLR. For example, the powers of the executive have been reinterpreted and refined discussed by Appleby and McDonald,Footnote 76 in their powerful analysis of the implications of Williams v Commonwealth (2012) 86 ALJR 713. It may simply be, however, that there is not a stream of significant constitutional cases which would warrant a review such as former High Court Justice Michael McHugh's masterful overview of constitutional cases 1989–2004.Footnote 77

Regardless of how one interprets the evidence, the question put is whether constitutional law ought to be such a dominant concern among Australian law scholars, at least as represented in a leading journal such as the SLR. In the current social environment and era if, as Austin has stated legal scholarship is to serve a social function of “adding to our understanding of law's operation in the world an understanding that may assist in the solution of real, even everyday, legal problems”Footnote 78 a leading journal ought to attend to a wider range of everyday legal problems. For example, from a statistical perspective, approximately 50% of Australians deal with the consequences of relationship breakdowns and must rely on family law to reorganize their lives. Family law addresses issues such as child custody, property division, alimony and support payments. These areas of family law are far from satisfactory from many points of view. This common community problem is not well represented in the pages of the SLR, there being but one article addressing family law in the period.Footnote 79 It is not that pressing contemporary concerns are not represented in the SLR. For example, the SLR published a pair of relatively highly cited articlesFootnote 80 addressing the problems of water regulation, which is certainly a matter of great concern across the Australian community. Rather, the question is whether the topics of interest to the legal academy as represented in the SLR reflect the needs of the wider community.

Other non-constitutional law topics of wide social concern are not reflected in the legal scholarship published by the SLR. While all of these issues may well be covered in other high-ranking journals such as Griffith Law Review, University of Queensland Law Journal or Australian Journal of Corporate Law, where they are likely to get more attention and traction, there are matters which one might expect to be found in the SLR. For example, the present era is an era of massive social change: the rise of ‘shared economy’ platforms and related insecure employment, loss of private rights through new social media platforms and a level of corporate surveillance that would spark a revolution if it were conducted by government. Further, in this same period one of the pillars of the Australian legal system has been challenged: the right to freedom from detention without trial has been trampled in the case of asylum seekers. In addition, within the decade 2008–2018 Australia has had legislation overhauling decades of Australian labor practices, Workchoices and related corporate Policy Reforms; but these have not become hot topics in the pages of the SLR and nor has banking, despite the broad public need as evidenced in the recent Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry. It is not that the SLR has not published work on these topics, as Keyser's critique of detentionFootnote 81 and Handsley's response illustrate;Footnote 82 or ForsythFootnote 83 and GardinerFootnote 84 on labor demonstrate. Rather, the comment is that these major issues have not been significant themes of the scholarship in the SLR.

An alternative way to consider the topics of scholarly attention selected for publication in the SLR could be drawn from an examination of cases coming before the courts. In his ten-year analysis of matters in the NSW trial courts, Smyth identifies the quantities and areas of law as follows: “Criminal law accounts for 45 per cent of cases in the sample, followed by torts (17 per cent), procedure (9 per cent), contracts (5 per cent) and evidence (3 per cent).”Footnote 85 Further, in the same article, Smyth finds but a single citation of the SLR by the same courts.Footnote 86 In a separate study of citations by supreme courts, Smyth finds that constitutional law lags behind administrative law and commercial law by a considerable margin, 4.6 times. He provides the following citation data with the number of cases that cite law journal articles and the same information represented as a percentage of cases with citations: Administrative Law: 57.45% (n = 108); Commercial: 29.54% (n = 161); Constitutional: 32.71% (n = 35).Footnote 87 It is certainly not a requirement that the law academy nor the SLR nor any law journal reflect the burdens of the court.

Interestingly, the SLR, as a leading outlet for the Australian legal academy is silent on some of the most significant changes in the law academy itself during the period. Among the main developments in the era under consideration is the establishment of the JD as a first degree in law, following the American model.Footnote 88 As a full fee-paying degree, it has led some law schools to reconsider law shifting it from an undergraduate degree the LLB to a graduate program.Footnote 89 As Bowrey observes, this is an incident of neoliberalism distorting the legal academy:Footnote 90 one would expect such manifestations to generate greater consideration or at least some consideration in a leading, generalist journal.

Methods

We turn next to examine the methods preferred as evidenced by those selected by the SLR (again with the caveat that information concerning articles submitted is not publicly available). Displaying the data in graphic form, we see a high concentration in terms of method.

As Figure 2 illustrates, doctrinal method composes 93% of all the articles published in the SLR. That doctrinal methods should be the dominant method among Australian legal scholarship is unsurprising and so reflected in the SLR. Law reviews, like journals in other disciplines, are looking for contributions that add to the development of the discipline. Using the discipline's main method is the appropriate and expected. As a discipline, law looks to doctrinal argument and ordering for advancement usually through some type of extrapolation from existing positive law.Footnote 91 In the context of increased pressures for interdisciplinary and multi-disciplinary work, however, and the increasingly complex issues law is expected to address, one would expect to see some greater reflection of such in the pages of a leading law review at least to the extent that it represents the interests of the legal academy.

The second most common method is our category of ‘Policy Reform.’ It is surprising in its paucity. Representing only 3% of all SLR articles, one is struck by the view that law academics in Australia do not see themselves or at least their roles as driving or contributing to Policy Reform, a view that differs markedly from their American counterparts.Footnote 92 It is important to note here as elsewhere, however, that it is not clear whether this focus is the result of submissions or editorial selection. The third most common method is comparative law at 2%.

What is particularly surprising in this analysis, is the near absence of other methods including law and society and related sociologically informed research methods, as well as historical and interdisciplinary approaches. These methods, well established in other parts of the globe's legal academy,Footnote 93 make a significant contribution to law as a discipline as well as contributing to law's impact on both cognate disciplines and wider societal discourse. While this representation of methods may be that a combination of authors’ choices in selection of journals, preferring journals which promote these methods as well as SLR editorial decisions that lead to this outcome, it would not be unreasonable to expect a somewhat greater representation of the method in the SLR.

An additional consideration that can be drawn from the policy environment is that law in Australia, like the rest of the academy, operates in an environment where higher education regulation is driven by empirical measures. As Bowrey has discussed thoroughly, the Australian Research Council's ranking, Excellence in Research for Australia, is driven by metrics, including in its evaluation of law. While on the one hand, it could be argued that law has taken a disciplinary reasonable approach in opposing the metrics approach,Footnote 94 pragmatically, it could simultaneously improve some metrics by engaging more deeply with the social sciences.

With this background in areas and method, we turn next to analyze the leading articles in the SLR.

An analysis of these highly cited articles places constitutional law articles on top. They account for 11. The next most popular area is a Policy Reform with seven, followed by criminal with four. Contracts, property, corporations, and torts all have two articles each and administrative and trade law with one each. Interestingly, by far the most highly cited article is Brian Tamanaha's innovative “Understanding Legal Pluralism: Past to present, Local to Global”.Footnote 95 With 776 citations, it dwarfs all the other articles, which combined, do not quite equal it in terms of citations. It merits consideration at the very least as a contribution to the academic discipline of law.

Tamanaha's article, which we classified as using a ‘law and society’ method and ‘miscellaneous’ in terms of area, provides a framework to ‘examine and understand the pluralistic form that law takes today.’Footnote 96 Tamanaha does so by dividing his article into three parts: an historical part followed by a part laying out the foundational legal pluralism problem of identifying a coherent concept of ‘law,’ concluding with a part dedicated to developing a new approach to legal pluralism. Tamanaha is not shy about taking a broad-brush approach to history or the general argument. He sweeps through medieval history into Hindu and Muslim law, before shifting to a discussion of twentieth-century state building.

Moving through this historical survey he arrives at international legal pluralism. Next, Tamanaha turns to social science in law, divining two significant definitions of his topicFootnote 97 which he uses to argue to create a foundation for the use of social science in developing a framework for analysis. His framework involves ‘six systems of normative ordering’ and the dimensions and challenges that must be taken into consideration for each. He concludes with cautions noting “one must avoid falling into either of two opposite errors: the first error is to think that state law matters above all else (as legal scholars sometimes assume); the second error is to think that other legal or normative systems are parallel to state law(as sociologists and anthropologist sometimes assume).”Footnote 98 The caveat is apt because it draws attention to the insular nature of disciplines each with its own predisposition to grant primacy to its own lens.

What lessons could Australian legal scholars draw from Tamanaha's success? A speculative appraisal suggests that there are several drivers of that success. First, it identifies legal pluralism as a global phenomenon which is increasingly recognized in the legal academy. In other words, his topic has broad appeal and is timely. Second, the work is interdisciplinary, contributing to a variety of disciplines in addition to law. Third, it solves at least to some extent an increasingly important fundamental problem in law: publicly proclaimed law is not the sole power in force in most societies. Rather, there are usually several different systems at work. Finally, Tamanaha provides a useful framework for thinking about the law as increasingly interesting and important topic.

Tamanaha's highly cited article could also be used to inform editors in selection criteria. It is evidence of a strong interest in ‘law and society’ type methods. Further, they might consider the complexity in thinking about law that it represents. While not explicitly addressing issues of legal pluralism for Australia, such as the indigenous legal system or religious laws of Catholics, Muslims or Jews, Tamanaha's work provides a platform for researching and understanding potential approaches to the issues raised when addressing the ongoing challenges of legal pluralism in multicultural Australia. The success of this topically and methodologically innovative piece militates against the positivist, constitutional focus of the SLR.

The second most highly cited article is Edmond and Roberts’ work “Procedural Fairness, the Criminal Trial and Forensic Science and Medicine”Footnote 99—an article with 40 citations. In this article, which we classified as ‘doctrinal’ in method and ‘Policy Reform’ in area, the authors draw attention to a widening gap between science and law in the area of forensic sciences and the law of evidence. Prior to the gap, the authors argue, the two were understood to coalesce in serving criminal law's two aims of truth seeking, and fairness as guided by proper legal procedure. Recent advances in science have led to serious questions being raised with respect to the reliability of scientific evidence or testimony. Accordingly, Edmond and Roberts call for the careful consideration of such evidence and the potential of a “multidisciplinary advisory panel to review controversial forensic science techniques prior to their use in criminal proceedings.”Footnote 100

Edmond and Roberts’ article is of interest, like Tamanaha's, to a diverse and multidisciplinary audience that it engages. That audience includes judges, lawyers, prosecutors, scientists, and policy makers. It identifies an emerging problem and proposes a novel solution. Finally, from a theoretical standpoint it is well grounded in long standing legal principles—the truth seeking and fairness priorities of criminal law. Once again, it is multi-disciplinary engaging to some degree with both science, scientific discourse and problems encountered when attempting to bring them into the legal realm.

Next, in terms of citations is Allan and Aroney's “An Uncommon Court: How the High Court of Australia Has Undermined Australian Federalism.”Footnote 101 In this article, which we categorized as ‘doctrinal’ and ‘constitutional,’ the authors argue that by doing its utmost to adhere to the conservative, restrained, and traditional textual approach to interpretation, the court has produced such a perverse reading of the constitution, to the point that the federal government has been empowered such that the framers would not recognize the federation today. As Allan and Aroney put it: “none of the Constitutions’ framers would ever have imagined, back in the 1890's or in 1901, that a century or so later the Australian States would be so emasculated as they are today: that they would be so dependent upon the Commonwealth for their government finances; and that their policy-making capacities would be so contingent upon political decisions taken by the Federal Government.”Footnote 102 They criticize the judges for both their efforts to stick to literalism in one type of case (that dealing with federalism) as well as their efforts to update the constitution opting for looser interpretation in free speech. It is, as Allan and Aroney note, ironic that the judiciary would do so.

Their article has appeal to the legal academy and beyond because it deals with an obvious anxiety felt throughout the land, namely, the increasing reach of the most remote level of government, the federal level. Further, using as a case study the controversial Workchoices case,Footnote 103 the authors addressed a hot topic in the community. The legislation was divisive in the community (and one may assume, equally hot and divisive among the members of the academy and the profession) with one side of politics making it a signature piece of legislation and the other diametrically opposed. Further, labor law has historically been a significant area of law and legal scholarship in Australia given the historically significant labor movement. Accordingly, it is not surprising that Allan and Aroney's article has become among the more influential articles in the SLR. Rather than analyzing the rest of the highly cited articles, the balance of this section samples examines one article with citations in the 20s and another in the 10s.

Keyser's “Preserving Due Process or Warehousing the Undesirables: To What end the Separation of Judicial Power of the Commonwealth,”Footnote 104 with 22 citations delves deeper into the purposes and implications of the Chapter III in the context of Fardon v Attorney General (Qld). We classified the article as ‘doctrinal’ and ‘constitutional’. Keyser makes the case that the High Court failed to follow the Constitution and persuasively relies on traditional methods of argument and authority. He argues that the court erred in allowing the incarceration of Fardon in the absence of criminal trial and conviction. This article, like Edmond and Roberts’, draws attention to serious flaws in the development of Australian law. These flaws are disturbing as they undermine fundamental civil liberties associated with rule of law, and so represent a common concern to the general populace, the profession and the academy. Law scholars seek to integrate developments into existing legal frameworks and work as critics of the system, and decisions such as Fardon rightly demand attention through analysis and publication. In publishing a piece on this topic, the SLR fulfils its mission as a platform for public discourse.

Finally, McHugh's “The Constitutional Jurisprudence of the High Court: 1989–2004,”Footnote 105 cited but 10 times, is the Justice's inaugural Sir Anthony Mason Lecture, delivered 26 November 2004 in the Supreme Court of NSW. McHugh, in his article, which we categorized as ‘historical’ and ‘constitutional’, focused on methods of constitutional interpretation bringing in subtlety to identify and explore the different approaches of the Mason, Brennan, and Gleeson courts. McHugh's article is masterful in its deep grasp but light touch of the profundity of constitutional law and its implications for society. He takes the analysis to a higher level beyond simply the constitutional issues and case law to a level of the courts. And, as only a master of his level of skill can do, puts all the cases into their place, finding continuity and coherence across the decisions. As he puts it: “No doubt the style and tone of judgements in the Brennan and Gleeson Courts may make them seem more legalistic than those of the Mason Court. But, in terms of result, there does not seem to be an appreciable difference in the constitutional jurisprudence of the three Courts.”Footnote 106

This article has likely achieved its level of citations because it provides a good target: it would be disagreeable to those convinced that the Mason court was progressive while the Brennan and Gleeson courts were conservative and legalistic, and vice-versa.

Discussion and Conclusions

The foregoing analysis provides insight into the interests and focus of Australian legal scholarship at least as represented in the pages of the SLR. It reveals a focus on five areas of law: constitutional, crime, labor law, evidence, and administrative law. The strong focus on constitutional law leads to the suggestion there may be a concern among Australian law scholars on constitutional matters which may be beyond editorial issues of submissions and selection. To some degree an interest in constitutional matters among the legal academy is reflected in the slightly higher citations numbers for constitutionally focused articles. Given the low citation rate for the SLRFootnote 107 generally, however, it is hard to draw any certain conclusions—at least from the data. This finding reflects Bowrey's observation about law journals generally: “analysis showed that coverage across subject matter is very uneven with some specializations well served in journal choices, others having very few.”Footnote 108

Further, the analysis reveals a high reliance on doctrinal analysis. The analysis revealed that 93% of the articles adopted a doctrinal method. Again as noted, this methodological preference is hardly surprising as it reflects the core method of the discipline. What is surprising, however, is the level of work adopting this method, particularly in the context of increased pressure and need for interdisciplinary work and recognition that law is not a pure discipline unconnected to and independent of different systems of thought or inquiry.Footnote 109

These two observations concerning area and method lead to two proposals where there is an aim to increase impact on the academic discipline of law. First, in terms of areas of law, Australian legal scholars may wish to consider working in areas of social concern more obviously and directly touch upon the daily lives of many Australians such as family law, commercial law and banking. While doing so may draw articles away from other high quality specialist journals, if the SLR seeks to be a leading generalist journal, it could do so without harm. Further, it may be worthwhile to focus more on the types of issues appearing regularly in the courts, namely, crime, torts, administrative, and again commercial law. This wider range of topics would potentially increase the impact of legal scholarship, “the understanding of law's operation in the world an understanding that may assist in the solution of real, even commonplace, legal problems”—Austin and Rodell's concern.Footnote 110 It is not that constitutional law does not leave its mark on these areas; however, it does so more remotely in most instances. For example, constitutional interpretation of Commonwealth powers may not be immediately evident in terms of implications for how people experience government response to bush fires—a major concern in the 2019–2020 bush fire season which saw the federal government largely powerless as compared to the state governments. Nor is it a proposal to place the legal academic in the service of the profession. Rather, it is an effort to consider how our scholarship might be more usefully focused and how editors might consider selecting articles for publication.

Second, in terms of method, recognizing that we live in an era where law's authority in the academy and the prowess of its methods of argumentation are on the wane, law scholars and journals could consider drawing more interdisciplinary work, such as that of law and society scholars. The appeal of both of these proposals is evident from Tamanaha's article. Looking at the success of that article, Australian scholars with those skills and interests could engage more broadly with methods other than doctrinal methods. Indeed, as the sciences advance and open up new avenues for legal scholarship, a whole new type of research is being developed overseas, referred to as “New Legal Empiricism.”Footnote 111

The findings of our work lead to a criticism of law as a discipline more generally—not only for Australian law scholars, but for law scholars globally. As Westermann argues, law and its categories “are elements of the legal system and they are elements of the conceptual or theoretical framework used by the researchers. In legal doctrinal research, object and theoretical framework are identical the ‘how’ question is not recognized as a question that is sperate from the ‘what’-question, for the simple reason that the former collapses into the latter.”Footnote 112 As a result, the positive law analysis combined with doctrinal method is closed off to the broader scholarly community and society more widely. In this regard, law as an academic discipline is failing to adapt to changing ideas about the discipline of law and disciplines generally.Footnote 113 It could be argued that law's failure is evident in its relatively lower citation rates reflecting a lower level of acceptance of doctrinal methods among a wider populace including the scholarly community.

While it is easy to criticize law for these failures, it must be recognized that law's disciplinary knowledge is difficult and highly specialized on the one hand, and that citation counts are particularly problematic measures in peer reviewed disciplines such as law. It can be argued that doing doctrinal legal research is much like writing a judgment. Gageler, summarizing former High Court Justice Sir Frank Kitto's view, observes that legal research “involves very slow thinking. It has costs.”Footnote 114 But as Kitto himself observed: “It also has great systemic benefits.”Footnote 115 While certainly not music to the ear of metrics-driven regulators and managers, it is a reality of the discipline of law. It is a painstakingly slow, deliberative, and hermeneutical discipline. Law's knowledge at the core is not suited to empirical methods. Its knowledge is about what the norms, rules, and principles are or ought to be, and how those rules and principles express and reflect foundational concepts and values of a society.

As noted, a core limitation of our study, like all case studies, concerns its generalizability. A case study, by definition, is not representative. Rather it provides greater depth at the expense of breadth. To what extent the SLR represents the interests or publications of the Australian legal academy is not evident. Nor is our analysis a critique of editorial selection decisions: we have no data on what topics or methods are submitted, nor do we have data on the quality of those submissions. What our study does show is the nature of Australian legal scholarship as published in one of its leading outlets, the SLR.

A further limitation of our study is the reliance on citation counts as an impact measure. There is certainly a wide range of identifying and measuring impact. We have made that choice, as argued above, for purposes of using widely accepted measures for scholarly impact of academic disciplines. We do not claim that this is the only appropriate way to evaluate the contribution of legal scholarship; rather, that it is one way to make such an evaluation in the context of competitive higher education institutions.

Finally, articles do take time to attract attention and garner citations. Accordingly, it could be argued that articles published as recently as 2018 have not had enough time to garner citations reflective of their impact. While this is a valid argument, high impact articles usually start their citation patterns shortly after publication. Accordingly, even articles in 2018 that are likely to have an impact would have appeared in the over 10 category.

We have attempted to take a considered and reflective approach to our task. There are certainly those who may reflect differently, as for example, those who believe that the SLR's task is to push the boundaries of doctrinal scholarship. Certainly, legal scholarship, as evidenced in Tamanaha's work, has moved beyond doctrinal scholarship in the more rarefied areas of law, and publishing such work regularly would be incumbent upon a leading journal.

Reflecting on Australian legal scholarship, it is clear that Australia's law reviews have made contributions to the academy and beyond and created a competitive and diverse field for the scholarship. Editors, like the editors of the SLR, will need to continue to take strategic decisions about which types of articles to publish. The scholars of today and the future will look to the journals to see how they can and should respond to and embrace our rapidly changing times while maintaining law's perennial delicate balance between conservative preservation and progressive reform. Evaluating that contribution is and will remain a complex, contested and political task of the legal academy.

APPENDIX: initial 32 categories

1. Constitutional Law

2. Criminal Law and Procedure

3. Evidence

4. Labor Law

5. Administrative Law

6. Miscellaneous

7. Company Law

8. Human Rights

9. International Law

10. Torts

11. Ethics, Professional responsibility

12. Financial Law

13. Legal Theory and Pr

14. IP

15. Immigration Law

16. Property

17. Tax Law

18. Civil and Criminal

19. Remedies

20. Consumer Law

21. Contracts

22. Family Law

23. Bankruptcy

24. Alternative Dispute Resolution

25. Animal Law

26. Business Law

27. Civil Procedure

28. Environmental Law

29. Equity

30. Competition Law

31. Data Privacy

32. Legal Liability