Prologue

An aguila dorada beats its wings and lifts off a twisting sapodilla tree branch overlooking the ruins of the once-mighty jungle kingdom of Palenque. It rises above undulating hills and past the majestic strongholds of the western hemisphere's greatest ancient civilization. It soars past stonework cut to perfection without modern tools, glides past 1,000-year-old solar calendars whose ancient timekeeping rivals the modern atomic clock. The eagle heads west and passes cerulean rivers cutting through emerald jungles plunging into the fissure of the Sumidero Canyon. Thermals lift the eagle to the high, dusty plain of Monte Alban and it turns north. It approaches the eternal spring of Cuenavaca and then over the frenetic megalopolis of Cuidad de Mexico. It glides above the imposing Teatitulaican and then drifts through the pastoral Bajío. The world's two biggest oceans flank the sides of her long north/south country. The air grows warmer as she traverses the spine of the Sierra Madre. The mountains flow down and dissolve into verdant jungles which, in turn, edge right up narrow beaches with crashing blue waves. The Sierra Madre then gives way to wild, tawny country, filled again with canyons, mesas and then ends at the Rio Bravo. The national symbol of Mexico is traced over a rich tapestry of topography, cultures, economies, history, and mixture of peoples. Reflected in this diversity is Mexico's stunning contribution to world jurisprudence: the Amparo.

Introduction

Footnote 1Mexico's dynamic and resilient jurisprudence can be viewed through the lens of the matchless and paradoxical amparo. A problem existing in all democracies is how to elevate, enforce, and maintain document-granting rights to its citizens. “La constitución no solo controla el poder público, lo crea.”Footnote 2 Idealistic words existing on paper do not change policy and society without the force of law behind them. Mexico's transformative solution to this issue was the creation of a judicial device, the amparo trial, to challenge an unconstitutional law.

Mexican society places a high value on tolerance and flexibility and the amparo's history reflects those ideals. Since its formation, Mexico's judicial branch has withstood changes in the government, the development of new jurisprudential philosophies, and conflict between liberal and conservative powers for ideological supremacy, presidencialismo, two foreign invasions, a puppet emperor, the reign of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI),Footnote 3 revolutions, and the wholesale re-writing of its constitution. The collision of idealism, realism, and normative beliefs underscore nearly every development in the arc of judicial policymaking. Throughout this turbulence has been a steadfast commitment to social justice issues and protection for citizens against centralized governmental intrusion, although there has been an uneven application to the population.

Mexico can be a country of contradictions because even with a guarantee of constitutional rights and equality, the amparo is, and has been, almost entirely used by elites. Historic limitations of the scope of a successful amparo trial meant that law was only unconstitutional for the individual entity that could (afford to) challenge it. Delving further into contradictions, the originating state of constitutional guarantees at the time of the amparo's creation, recognized an active slave trade. A legacy of inconsistent and disparate treatment courses throughout Mexican jurisprudence, particularly with the amparo. In other words, access to justice is not evenly distributed among Mexico's citizens.

Amparo's simplest definition is “to protect.” At its very core, amparo produces protection or relief from the majestic powers of the federal government. After 170 years of jurisprudence, almost 500 constitutional revisions and wholesale governmental changes, the principal of amparo has remained constant – it is a judicial instrument for relief from governmental overreach. It is a beloved institution, but one that remains obtuse and difficult to define and frame within the law.Footnote 4 It is an esoteric study and elusively described.

Despite difficulty in defining the scope of amparo, other nascent hemispheric democracies adopted it and amparo now exists in 17 other countries. It serves as an extraordinary remedy and no comparable mechanism exists in the common law tradition.Footnote 5

Amparo, however, got separated from its noble origins along its expansion over the decades of use. Conceived as a simple measure for harnessing the power of the state, amparo morphed into a hyper-technical, procedure-laden, bureaucratic landmine-filled legal specialty available almost exclusively to the wealthy. Objectively viewing docket numbers, at one point prior to more recent reforms, the amparo existed almost singularly as a jurisprudential tool for wealthy corporations and individuals to protest against certain taxes. The amparo made a dramatic departure from its original and intended purpose of protecting basic human rights.

Changes to amparo, the chief protective device of constitutional rights, is only possible because of Mexico's intrinsic liberalism. Mexico's system of federal governance has never been backwards looking. Mexico's policymakers, law professors, judges, and politicians have a legacy from the earliest days of the new republic of adapting and transforming to meet the moment for their country. At times their efforts have been to create a more equitable republic; and at other times, changes have been made to mollify stakeholders so power could be maintained by elites. Mexico's lengthy history of neo-liberalism permits its judiciary, politicians, and other stakeholders to critically examine orthodoxies and reject or modify those that no longer serve their intended purpose. This embrace of change allows a critical look at the legal system.

While the amparo's humble beginnings gave way to an enormously technical legal process, amparo also morphed into an exception in law that became the rule. It grew into an unwieldy, esoteric mass that made up the overwhelming majority of the federal court system's entire docket. The amparo's origin story begs questions: who needed protection, from whom and why?

A (Brief) Origin Story

Amparo's beginnings do not start with the modern Mexican state, or even with the Spanish invasion and occupation of Mexico-Tenochtitlan. The concept of a sovereign being subordinate to written text spans millennia. In the euro-centric legal tradition, the Magna Carta is often regarded as a touchstone for this concept, and it is (likely) the oldest known document that puts an earthy (not heavenly) system of laws superior to the ruler.Footnote 6 Magna Carta, however, is thousands of years younger than the oldest surviving legal texts such as the Code of Hammurabi. The ancient Babylonian Code of Hammurabi details in writing various crimes with corresponding punishments and is a well-preserved legal code showing an ancient, advanced civilization.Footnote 7

The Code of Ur-Nammu,Footnote 8 however, predates the Code of Hammurabi by thousands of years.Footnote 9 These instruments were likely borne out of leverage from the people seeking their creation, as it is likely that most people throughout history would chafe under an arbitrary system in which laws and rights are unknown to anyone but the sovereign (and his whims). This theory of why those in power rarely unilaterally decide to share power with the masses absent a compelling reason is borne out in the case of the Magna Carta. The English King John desperately needed tax money from large landowners to fund a long war and the large landowners required something in return.Footnote 10 Magna Carta's concept of Habeas Corpus (to “release the body”) received specific mention in an early draft of the Mexican Constitution.

Equity in society is a universal concept that long predates the modern Mexican state. The rule of law existed in the area now known as Mexico long before the European arrival. The Maya and Aztec empires had highly developed written laws. Although most written records showcasing the highly advanced nature of Mayan civilization were destroyed by the invading Spanish, what little remains reveals a codified and structured legal system replete with judges and attorneys.Footnote 11

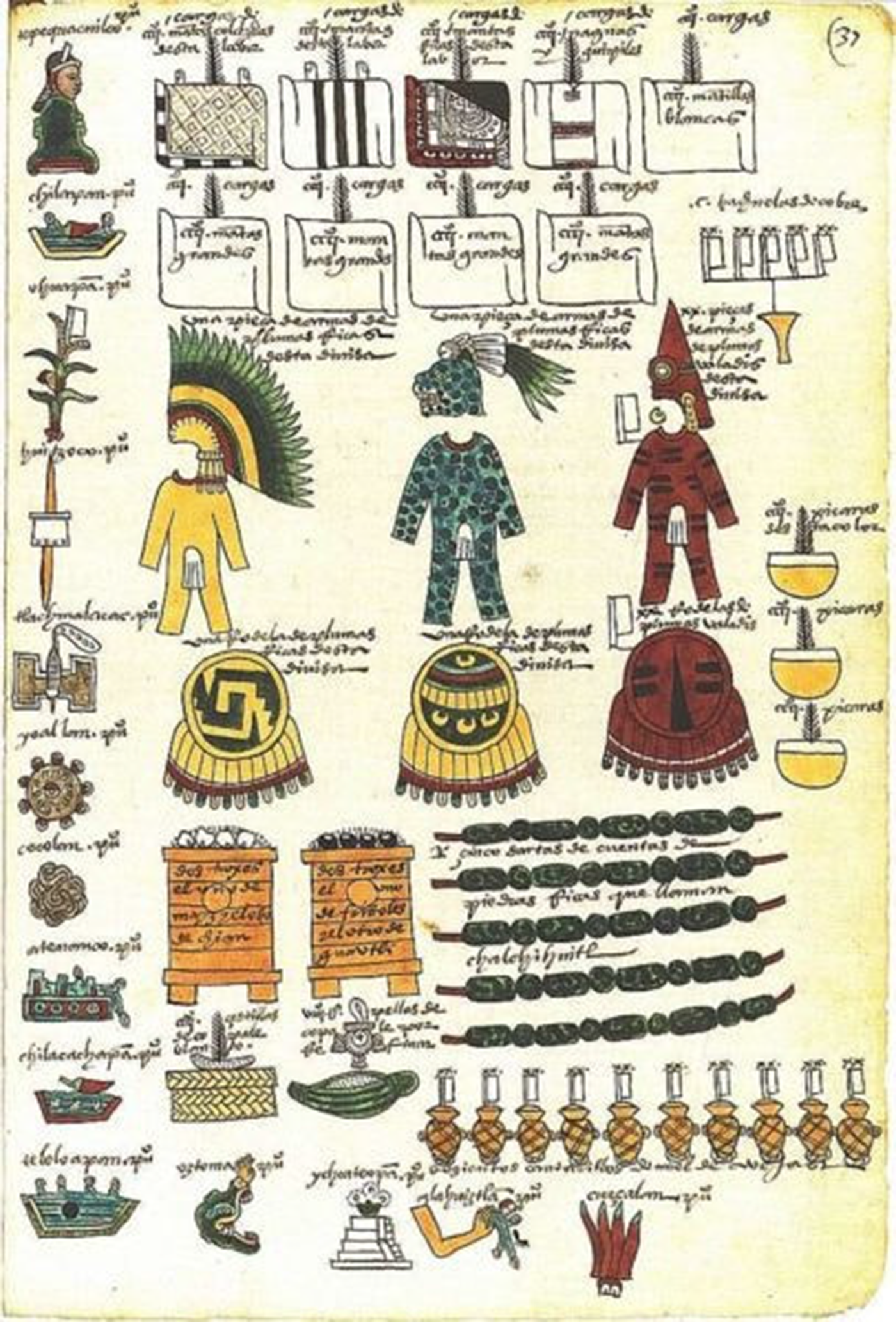

More remains known about Aztec law due to it occurring closer to the occupation by Spaniards and (a few) surviving contemporaneous accounts. Primary sources of Aztec law existed in great numbers but were tragically destroyed by the Spanish because they were viewed as “heretical.”Footnote 12

One of the most visual of these records, the Codex Mendoza,Footnote 13, exists because a viceroy of New Spain ordered a written account of life under Aztec rule including their laws and rituals.Footnote 14 The significance of Mayan and Aztec laws show a millennia's-long heritage of a functioning legal system of published laws. The land which would become Mexico thus had a long tradition of development and fidelity to written laws.

Mexico is the second oldest constitutional republic in the world that does not include monarchies.Footnote 15 Self-governance after independence from Spain took many forms as competing visions of government sought supremacy and power. As the leaders of the new country pondered the form of government, they considered the concept of judicial review. Judicial review is, most simply, a court analysis of the constitutionality of laws enacted by the legislature. Judicial review became a concept important to new democracies and Mexico had the advantage of considering models from both European democratic republics (particularly France's) and the United States of America's Constitution. Consideration of various forms, however, did not lead to adoption as seen in the analysis of the Mexico's view of the U.S. Constitution.

Mexico's first Constitution sought to install institutional guardrails to guarantee constitutional compliance by creating a fourth branch of government, the Supremo Poder Conservador.Footnote 16 Supremo Poder Conservador would serve as the constitutional bulwark or ombudsman. Its mandate was to “nullify acts of executive, legislative and judicial branches which were contrary to the constitution.”Footnote 17 This short-lived design ended in abject failure as the Supremo Poder Conservador dissolved after five years and zero constitutional interpretations.Footnote 18

The Mexican Constitution draws much inspiration from the 1799 French Constitution. The founders of the new country repelled away from dictatorships and monarchies and sought equality among its citizens rather than a stratified class system. Mexico's northern neighbor, the United States, also drew heavily from French democratic inspiration and planned its government before Mexico wrote its constitution, but it is a mistake to think that Mexico borrowed much from the United States, “[Mexico's] federalism in 1823 and 1824, since such a process has nothing to do either physically or politically with the North American model…”Footnote 19 The concept of judicial review, in some form, took purchase in the embryonic stages of Mexican government.

Innovation often begins at a smaller level before moving into the mainstream, and public policy changes evolve in much the same way. Individual states (in the United States of America) as change agents have been likened to “laboratories” of democracy.

“It is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.”Footnote 20

This principal of policy innovation beginning at the state level before proceeding to national politics is also seen in the rise of the amparo.

The first half of the 1800s was a time where the U.S. and French constitutional republics were discovering what performed as good governance and what did not work. International observers such as Alexis de Tocqueville studied the U.S. system and offered keen insights with a neutral view. Alexis de Tocqueville's seminal work Democracy in America, deeply influenced the amparo's creator, Manuel Crescencio Rejón.Footnote 21 One concept from de Tocqueville in particular resonated deeply;

“When the judge attacks a law in an obscure debate and concerning its particular application, he in part hides the importance of the attack from the public view. The purpose of his decision is only to defend a particular interest, but the law only feels wounded by chance… Only gradually and under the repeated effects of jurisprudence does it succumb…”Footnote 22

Rejón was then instrumental in placing the inaugural amparo in the Political Constitution of the State of Yucatán in 1841.Footnote 23 A mere sixteen years later, Mariano Otero wrote the amparo into the Federal Constitution of 1857.Footnote 24

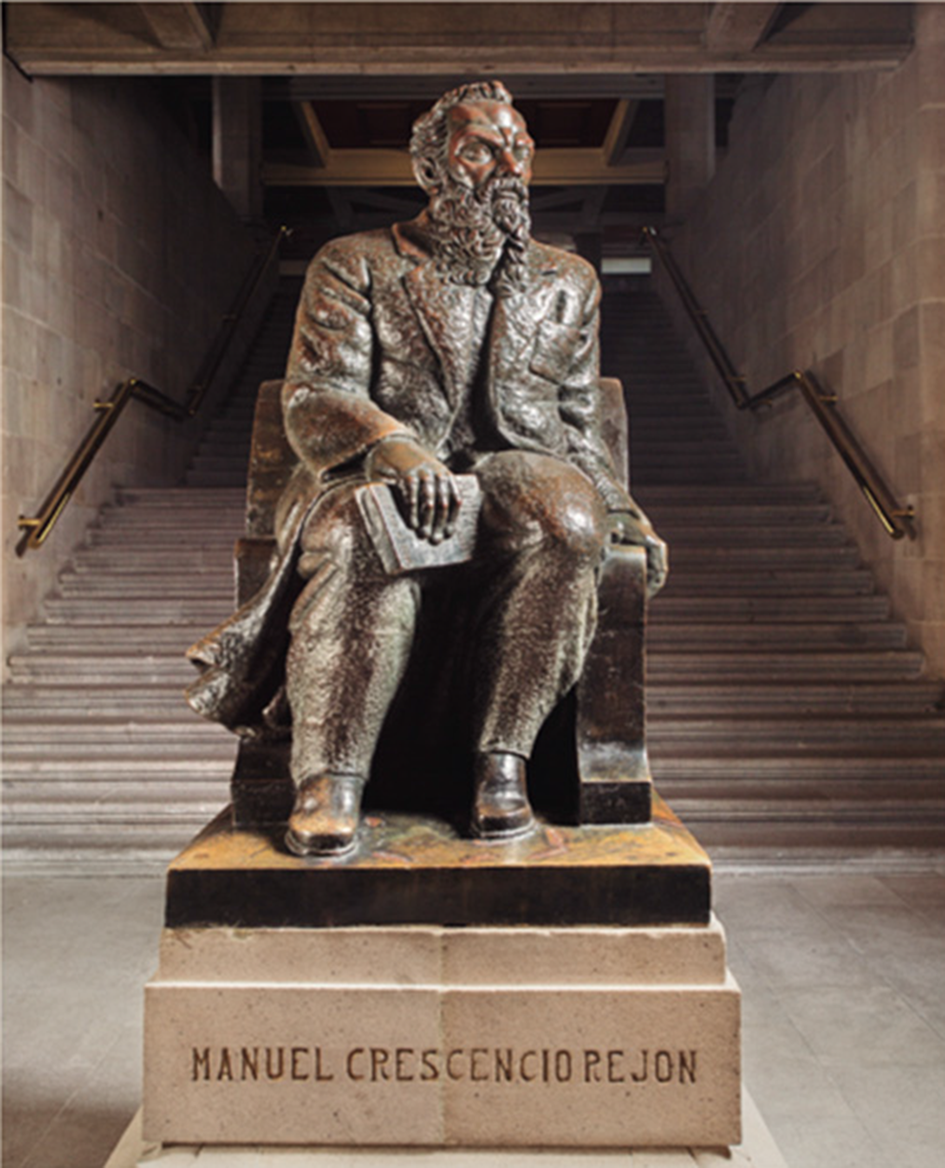

The Mexican Supreme Court building showcases the titans of Mexican jurisprudence. As a visitor enters the building they are faced with three ascending foyers.Footnote 25 At the right of this photograph is a bronze statue of Mariano Otero, credited with ensuring the placement of the amparo trial into the 1847 Federal Constitution.Footnote 26

The centerpiece of the three foyers, however, and where the visitor's eye naturally falls, centers on a bronze statue of a seated Manuel Crecenicio Rejón. Rejón is commonly considered to be the “father of the amparo trial.”Footnote 27 Rejón's wanted to create a device to separate “good intentions” vs. “guarantees” with courts reviewing governmental rulings that contradicted the Constitution.Footnote 28

While Rejón and Otero are most closely associated with the amparo, other commentary believes that the amparo's development should include other critical figures in the formation of the rule of law in Mexico's early government such as Pérez FernándezFootnote 29 and Durblán. Footnote 30 In order for the constitution to maintain supremacy over the government, constitutional guarantees had to rest in the hands of the citizens themselves.Footnote 31

Mexico selected a political system of a federal republic in 1824.Footnote 32 This choice followed a period of great unrest, so procedures for assuring fundamental rights were sought.Footnote 33 Amparo's beginnings arose from an outlying province with transient leverage over the centralized federal government in Mexico City. The federal government was concerned about maintaining its geographical footprint as the Yucatán had broken away from the federal republic and several provinces agitated to leave.Footnote 34 Faced with the prospect of other splinter provinces, and the crumbing of the Republic, the central powers in Mexico City eventually yielded to the demands of amparo's inclusion as a guarantor of rights.Footnote 35

The Yucatán had to be accommodated to maintain the Republic. The Yucatán province at the time of the amparo's creation was far larger than its current state boundaries. The Yucatán in the 1840s included vast other territories including, “Campeche, Quintana Roo and part of Tabasco.”Footnote 36

For an oversimplified explanation, the Yucatán government agreed to rejoining the federal republic providing several demands were met: abolishing the death penalty for political crimes, and freedom of religion. And it also demanded the amparo which would guarantee constitutional rights. This exchange was hastened by additional externalities as the federal republic provided military support from Mexico City for use in the Caste Wars.Footnote 37

The Yucatán's situation was somewhat unique in Mexico due to its geographical distance from Mexico City and the high degree of autonomy it had enjoyed under Spanish rule. The province's natural wealth, enviable position in the Caribbean and access to shipping and natural resources made it essential to keep it in the Republic.Footnote 38 The Yucatán was thus a province that had natural leverage which other provinces/states may not have been able to wield. In short, the federal government could ill afford to lose the Yucatán, and so amparo became enshrined in the federal Constitution because of an unusual set of circumstances unlikely have been replicated anywhere else. Yet, despite the idealism of its written law, the reality in the Yucatán fell far short of equality – the Yucatån had an active slave trade at the time.Footnote 39

Amparo made little impact in its first years of existence owing in part to its novelty and to profound governmental upheaval. The Liberal party in Mexico suffered a number of ideological defeats in the mid-1800s. Emerging from turmoil and political upheaval, there was hope for relative peace in which the constitution could be finalized. This hope was dashed due to foreign interference and the puppet reign of Emperor Maximillian.Footnote 40 This was a time of great upheaval in North America. Across the border, the United States had broken apart and was literally at war with itself over the issue of slavery.

Borrowing the Yucatán's Constitution, Mariano Otero's proposed inclusion of amparo on the federal level was almost universally approved in the 1847 Acta Constitutiva de Reformas.Footnote 41 This entry of the amparo onto the federal level eased its entry into the Constitution itself in the decade that followed. These efforts sought to make the constitution more liberal.Footnote 42 This is somewhat remarkable given the domestic unrest and which was completed during a time of great unrest with one commentator noting that was signed almost within earshot of the cannon fire of the “abusive American invader.”Footnote 43

What Rights are Protected?

Mexico's commitment to human rights is explicit in the mission statement from the Mexican Supreme Court: “[our] main function is to defend the Federal Constitution and protect human rights.”Footnote 44 The specific rights protected by amparo have evolved along with Mexico's constitutional changes and reforms. Constitutional rights are specifically enumerated and include, for example, equality among sexes and races; free, secular education; access to healthcare; freedom of petition and assembly; and, inter alia, several provisions dealing exclusively with Mexico's indigenous populations.Footnote 45 Rights have increased from the first versions of the Constitutions and with additional rights bestowed there is a greater likelihood with rights being infringed.

The current Mexican Constitution distinguishes Rights (Art. 35) vs. Obligations (Art. 31) vs. Responsibilities (Art. 36) of Mexican citizens.Footnote 46 Rights are privileges bestowed by the mere act of existence as a Mexican citizen. The obligations of Mexican citizens are affirmative duties that demand compliance by virtue of citizenship. Examples of the obligations of Mexican citizens include educating their children, paying taxes, and assisting with national defense (if called upon).Footnote 47 The responsibilities of Mexican citizens is a slightly more nebulous concept, as responsibilities include registering for taxes and holding public office, and voting (if desired).Footnote 48

Judicial Review

The concept of judicial review created tension in Mexico throughout its early years. Ambivalence between strong federalism and strong socialism existed causing strife resulting in federalists winning the 1847 conflicts (discussed supra). Federalism in Mexico takes the form of top-down, unified with a strong centralized control emanating from Mexico City.Footnote 49 Fear of judges overwhelming the power of the legislature lead to compromise on its application, the result of which is so-called Otero formula. The Otero formula sought to limit the application of a granted amparo to the party seeking judicial relief so there was no generalized change in law for others. If there were a sequence of consecutive trials on the exact same issue and the rulings were identical, a triggering mechanism for changing the law becomes activated.

Liberal ideology went head-to-head with conservative notions and emerged triumphant in the drafting of 1857 Constitution. The 1857 Constitution follows a federalist path where individual states had autonomy.Footnote 50 This new Constitution sought to upend the social order and traditional legacy powers in Mexico society and the amparo an acknowledgment of the political reality of the moment.Footnote 51

Executive power has been wielded unevenly over various sexenios. At different times, presidential administrations fired the entire Mexican Supreme Court and replaced them with more “reliable” jurists. This phenomenon has been referred to as “Facultades metaconstitucionales”Footnote 52 The amparo served as a critical bulkhead against an imperial presidency, “[t]he importance of the judiciary is somehow placed in a paternalistic situation. Mexico and the writ of Amparo is the champion of state abuse protection.”Footnote 53

Limitations

Amparo proceedings are expensive and time consuming. Hiring and retaining competent legal counsel to file a writ of amparo and marshal the claim through the appellate process is costly and often slow. The price of legal representation to prosecute an amparo appeal is a barrier to entry for most. Although litigating a constitutional social justice right for an individual is among the most rewarding acts an attorney can do, very often it is not remunerative and may even cost the attorney or law firm money in expenses and opportunity costs. The typical amparo litigant is an entity with sufficient funds (often well-capitalized corporations). As such, although the amparo is technically available to all, it is not practicably accessible to all due to costs. Despite the existence of a wide-reaching law guaranteeing constitutional rights, it falls short for the average citizen as seen in various rankings such as the World Justice Project which lists by state with rankings of access to justice.Footnote 54

Some of the criticisms of amparo have been mitigated during the last twenty years as Otero formula has been tweaked. The application of amparo prior to the reforms was that no stare decisis existed once a law had been ruled unconstitutional to the movants.

Other criticisms have been that amparo contributes to federalism because the federal courts are the final arbiter of all constitutional remedies through amparo.Footnote 55 State-level courts do not have the authority or jurisdiction to adjudicate the constitutionality of matters.Footnote 56 All judicial inquiries regarding the constitution, thus lead back to federal court in Mexico City.

Prior to recent changes, a successful amparo challenge essentially created an individualized or private law. If a litigant prevailed in their constitutional challenge of a law through an amparo trial, the law would no longer apply to them, but the overall construct of the law remained in effect. The law still applied to the rest of the population at large (assuming the Otero formula had not been triggered). The removal of the law's effect from an individual or entity would drive other, similarly situated individuals still subject to the law, to seek relief from the law as well. Since the final authority on the Constitution rests with the Supreme Court, if a party had means, they could enjoin the disfavored law by filing an amparo and then continue appealing adverse judgments until the terminal court's final ruling or dismissal. This gambit effectively buys time. Opportunity costs are tougher to measure, because for every amparo considered by the higher courts means that every other amparo is not being considered at the same time. The backlog of amparos is a boon to those who can afford to wait on rulings.

The Amparo can serve as a brake on governmental power even during times of great regime stress. The foremost scholar of amparo law suggested that amparos should be filed, especially during times of martial law or extraordinary police powers or otherwise during state of national emergencies, so that a record can be made about official conduct and the amparo should be considered a transparency tool and a judicial relief instrument;

“…the writ of habeas corpus and the right to amparo should be admitted, filed and processed so that, at the behest of those affected, judges and courts can examine the constitutionality and legality of the acts or provisions taken in said situations of emergency without prejudice that can sometimes include indirectly controlling the constitutionality of general norms on which said concrete measures are based.”Footnote 57

Although fundamental human rights exist in the Mexican Constitution, these rights were not always forthcoming to the public. In the pivotal year of 1968, following crackdowns of student protesters and social justice uprisings, a fully functioning amparo, faithful to its constitutional rights guarantees, could have mitigated the power of the state, yet,

“it's effectiveness was clearly impaired not only by the constraints imposed on it by the legal ordered itself and by actual court operation, but also by the ideological and organizational environment of the existing political system.”Footnote 58

A lack of diversity among the judiciary is also an institutional limitation. A judicial system in a democracy needs to reflect the people living within it. The judiciary's demographic composition does not mirror the Mexican population. In 1968, the population of Mexico was approximately 50 million people, and there were 128 federal judges, only one of which was a female.Footnote 59 While nearly 20 years later in 1984, women made up less than 7 percent of all district judges and less than 6 percent as Circuit judges.Footnote 60 Robust protection of all citizens’ fundamental human rights protection should be assumed with a judiciary so lopsidedly male.Footnote 61 El deficit meritocratico is both a real and imagined issue relating to the selection and qualifications of the judicial ranks. Some observers call the selection and placement of judges to be an “elite circulation system.”Footnote 62

Adoption by Other Countries

Appealing legal concepts and philosophies can be contagious. Mexico is a thought leader in the Spanish-speaking world by virtue of its massive population and economy. Mexico's procedural guarantee of constitutional rights has been embraced and implemented by 17 other countries throughout the southern hemisphere. The following countries have some form of amparo (in order of adoption): El Salvador, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, Panama, Costa Rica, Argentina, Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, Peru, Chile, Uruguay, Colombia, Dominican Republic.Footnote 63 And UNESCO's recognition of Amparo states that:

“In Latin America, constitutional history shows that the influences of the Mexican writ of amparo are also found in the constitutional legislation of countries in the region, such as El Salvador, which incorporated it following the debates held by its Constituent Congress in 1886, where there are clear references to the Mexican model of individual protection. Similarly, in Honduras and Nicaragua, where it appeared for the first time and was recognized in their respective Constitutions of 1894. Later, during the first half of the 20th century, the writ of amparo was introduced into the Constitutions of Guatemala in 1921, Panama in 1941, and Costa Rica in 1949.”Footnote 64

The amparo does not exist in identical form in the various countries that have adopted it, but rather it has been adapted to fit the parameters of each sovereign country's judicial system. Amparo in the various countries is used to protect a spectrum of rights and privileges, ranging from political, human rights, civil, economic, political, ecological, acts and even, in some places, omissions.Footnote 65

Changes to Amparo

The Mexican Constitution has shown remarkable flexibility since its inception. Normative and cultural beliefs have progressed in Mexican society and amparo has reflected the stakeholder differences. Since its creation, Mexico's Constitution has been changed, reformed, and modified hundreds of times. Three separate constitutions have existed in Mexico's history.Footnote 66 The current constitution, largely known as the 1917 Constitution, did not begin from tabula rasa, as it largely tracks the 1857 constitution in order of articles and text although, at times, it augments and clarifies certain clauses.

Constitutional dynamism may be baked into the Mexican political DNA. The soul of liberalism is an openness to change. Mexico went back and forth between a republic and constitutional monarchy from 1810 to 1824.Footnote 67 The early constitution was regarded as temporary and future revisions were expected.Footnote 68 Changes to Mexico's constitution have accelerated in recent decades, the phenomena known as hiperreformismo demonstrates a spike in amendments and decrees involving the Constitution.Footnote 69 For example, since 1995 the Mexican Constitution has been amended in excess of seventy times.Footnote 70 By one count, 84 percent of the Constitution has been amended and a mere 22 articles have been left without subsequent changes or modifications.Footnote 71 A side effect of revising (or re-writing) the Constitution is harbored bitterness from the losing side, such as:

“[t]he leaders of the revolutionary movement against the Diaz regime were convinced that the Constitution of 1857 had been used by self-seeking politicians for personal ends and that its provisions had contributed toward the domination of the country by a self-constituted oligarchy.”Footnote 72

Others might argue that any document amended so often and so dramatically bears little resemblance to a foundational decree of inalienable rights. The dynamic or flexible nature of the Constitution may have more to do with necessity than a commitment to flexibility, as one astute observer of Latin American politics acidly remarked, “[t]here is no good faith in America, nor among the nations of America. Treaties are scraps of paper; constitutions, printed matter; elections, battles; freedom, anarchy; and life, a torment.”Footnote 73

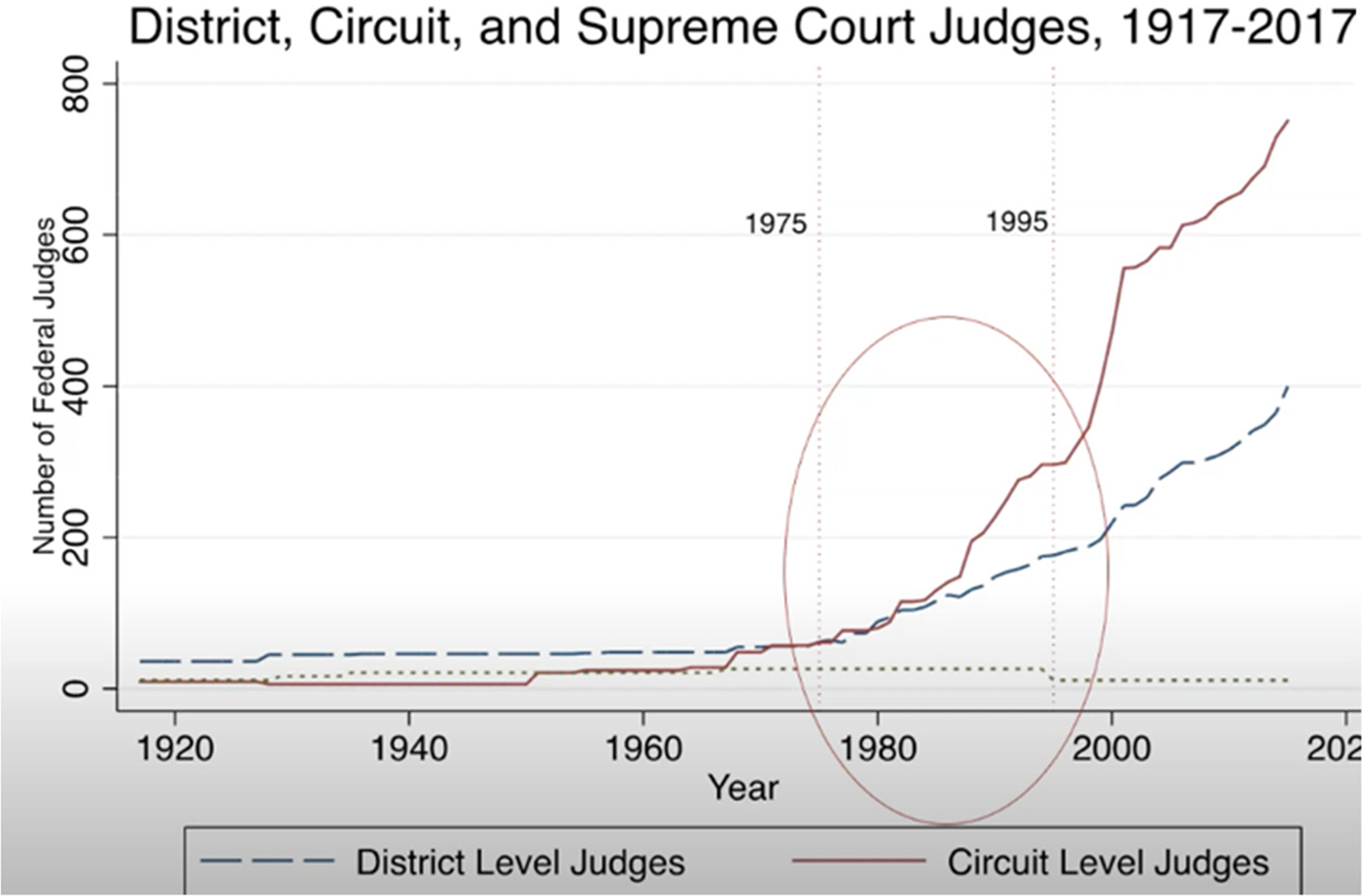

Mexico is second only to New Zealand in the number of amendments to its constitution.Footnote 74 Yet, this fluidity and neo-liberal openness to change is what allows the revision and clarification of the amparo process. While another sovereign country's constitutional guarantee mechanisms may be sacrosanct and impervious to change, Mexico blazes its own path and permits its institutions to grow and adapt with a changing world and population. An exponential rise in the number of District and Circuit court judges between 1980s and 2020 reflects a sea-change shift in population, but also with a deepened judicial bench there are more potential challenges to existing law.Footnote 75

Systemically, the structure of the courts grew as well as their jurisdictions. The Mexican Court system is a vast sprawl with thirty-three different subsystems and additional administrative courts.Footnote 76 Reforms in the mid-century were instituted not on subject matter, but to aid in backlogged dockets. In order to deal with an exploding caseload of amparo suits, a second layer of appellate review called the collegiate courts was created. This relieved strain on the Supreme Court but added another layer of appellate review, potentially prolonging final justice and increasing costs to litigants.

Changes to the amparo process are unsurprising when viewed against changes to the rest of Mexico's governmental apparatus and the changes (perhaps forced) by demographic and cultural shifts. The current state of the judiciary is far from ideal, yet there is cause for some optimism. Meritocracy emerged from a history of insular judicial selections. Neoptism is decreasing among the courts. The so-called “pacto de cabelleros” largely ended with the inception of the Judicial Council.Footnote 77 Patronage is decreasing as is clientelismo. Competency and merit as criteria for assuming a court position is increasing. Differing perspectives from the bench flourish as the judicial makeup grew and became more consistent with the population. All of this has occurred during a meteoric rise in the number of federal judges.Footnote 78

The PRI's decline as the dominant force in Mexican politics opened up new opportunities for the non-elites. The demographics of law in Mexico have changed and will be dramatically different in future generations. Even now there are more women than men studying law in Mexico.Footnote 79 The granting of more Cédulas profesionales de Licenciature en Derecho will ensure a vastly modified judicial composition as those attorneys gain experience and grow into their careers. Despite increased educational opportunities, total equality in the law has not been achieved as many female attorneys and judges report being marginalized, harassed, or otherwise diminished by male colleagues. Replacing mindsets and attitudes more incrementally at first and then once a tipping point is reached, cultural changes can come quickly. Overall, the judiciary's demographic changes appear to be on a positive arc.

Despite cause for positivity regarding the trendline of Mexican courts, storm clouds loom over judicial independence. The current presidential administration is accused of seeking to undermine and diminish judicial authority by extending the term limits of Mexican Supreme Court Justice and extending the term of the Judicial Council, which oversees the federal court system;

The legislative power, with López Obrador's blessing, is clearly violating the autonomy of the judicial power…destroying the separation of powers and breaking the constitutional order,” said María Marván, a legal scholar at Mexico's National Autonomous University. “It's a disgrace.”Footnote 80

This development, combined with other moves to diminish independence of other governmental oversight entities, may be a harbinger of further changes to the judiciary – or may end up being a much more limited issue.

Conclusion and the Future of Amparo

The story of the amparo does not have an ending. The idealism of amparo's charter has not diminished over the last 170 years. Changes to the amparo over the last twenty years show a dramatic willingness to adjust the procedural tool to accommodate the needs of the modern Mexican state. This adaptability is manifest in the Mexican identity – at times due to necessity, and at others because flexibility is a trait valued in Mexican culture. The Mexican Supreme Court currently offers up a succinct definition of amparo trials:

[it] is a form of constitutional review and the only jurisdictional procedure available to defend citizens from human rights violations, although authorities can promote it in special situations. It is used to declare laws, acts and omissions of the authority unconstitutional.Footnote 81

Amparo's stated mission of defending human rights is not fully reflected in the docket numbers of amparos filed. As the political system in Mexico opened up gradually from the 1970s through 2000, the amparo itself was transformative. Mexican (and hemispheric) jurisprudence and the institution itself has changed along with the changing role of the Mexican courts.

Modifications to the constitutional appeal have been made to promote trade and international investment while maintaining the core guarantee of the rights of its citizens. Access to justice remains an issue in Mexico (as almost everywhere with open courts) and ensuring broader applications of judicial rulings can help alleviate only the wealthy, or well-connected being able to challenge official state actions. As these words are written Mexico is plunged into a constitutional crisis regarding the independence of the judiciary. While the results of this issue will be unknown for some time, a certainty exists in the form of the resilience of Mexico's judicial system.

Mexico's crowning contribution to world jurisprudence was born out of a political tempest and has withstood wholesale changes to institutions and the politics around it. Some form of the amparo will likely exist long into the future and remain both an ideal to challenge an unconstitutional law and a beacon of hope for Mexican citizens.