1 Introduction

Mediation as a social process is elegantly simple: two people who disagree turn to a third for help. Yet its adoption by contemporary Western justice systems raises complex questions: who is responsible for mediation outcomes and by which criteria should they be evaluated? This paper considers an important strand in current debates: how fair and how just are mediation outcomes? Perhaps equally importantly: who is entitled to decide what constitutes justice?

Much of the critical scholarship on mediation comes from the legal academy (see literature review in Section 2 below). Given lawyers’ key gatekeeping role in disputes, this scholarship has been influential in fuelling scepticism about a process that places decision-making authority in the hands of ordinary people (Irvine, Reference Irvine2010). Concern about non-lawyers’ ability to deliver just results seems to start early in a legal career. A first-year law student wrote: ‘One of the major drawbacks of mediation is that lay people are in control of justice’ (Irvine, Reference Irvine2015). Indeed. A few months of legal education were clearly sufficient to set this nascent professional apart from ‘lay’ people (Erlanger and Klegon, Reference Erlanger and Klegon1978).

My purpose is not to rerun arguments about mediation's superiority or inferiority to litigation. Rather, it is to draw attention to the reflex dismissal of non-lawyers’ capacity for justice. Induction into the legal profession seems to efface the swathes of history, philosophy and literature (not to mention war) animated by the human sense of justice and injustice. Ignorance of legal rules becomes ignorance, full stop. The justice system can be considered a ‘regime of truth’ (establishing what is true, how to distinguish true from false and who has power to make that judgment) (Foucault, Reference Foucault1980, cited in Shiner, Reference Shiner1982, p. 384). ‘Those who occupy the lowest status in the various institutions and conditions of life – the patient, inmate, prisoner, welfare mother, labourer, student – all find their knowledge discounted’ (Shiner, Reference Shiner1982, p. 384). To this list could be added the lay litigant (Quintanilla et al., Reference Quintanilla, Allen and Hirt2017).

How might we view the outcomes from a justice event in which the primary decision-makers are not legally trained? Rather than dismissing mediation as second-class justice (Frey, Reference Frey2000; McGregor, Reference McGregor2015), I propose extending the ambit of its promised empowerment and self-determination to include outcome justice. First, I review themes from the scholarly literature on mediation and justice, noting practical and philosophical concerns, before describing alternative/appropriate dispute-resolution (ADR) developments in Scotland, one of the jurisdictions least receptive to such processes. This paper then draws on the early findings of an empirical study into the justice reasoning of lay mediation participants. The sample is small, but it is not the purpose of qualitative research to draw conclusions about wider populations. It aims, rather, to explore complex and difficult questions in a way that is credible, authentic and critical (Whittemore et al., Reference Whittemore, Chase and Mandle2001; Webley, Reference Webley, Cane and Kritzer2010). The participants shed new light on ordinary people's thinking about fairness and justice.

This paper's intention is twofold: first, to draw attention to the richness of lay people's justice reasoning, countering its simplistic characterisation as ‘subjective’ or self-serving; second, to suggest that mediation outcomes resulting from that reasoning warrant serious consideration within the justice system. That is not to say that they are immune from error or injustice, but rather that these decisions are generally animated by many of the same considerations judges apply in civil cases: fairness, retribution, restitution, proportionality, teaching someone a lesson and even making a public example of them (Maroney, Reference Maroney2012).

I conclude that critiques of mediation's justice capabilities have focused too narrowly on conformity to legal norms, particularly given the impossibility of accurately evaluating outcomes without running a full trial (Menkel-Meadow, Reference Menkel-Meadow, Cane and Kritzer2006). A broader conception of justice, acknowledging non-legally qualified people's interest in and capability for justice reasoning, is more likely to judge mediation on its own terms, as animated by principles of empowerment and self-determination (Fuller, Reference Fuller1971, p. 315). I will argue that mediation provides an alternative normative order by offering ordinary citizens a forum to negotiate not only the outcomes to their disputes, but also the criteria by which those outcomes are evaluated. Natural-law theory, rather than legal positivism, may provide a way of conceptualising results arrived at through human rationality.

2 Mediation and justice

When mediation was first adopted by Western justice systems, expansive claims were made regarding its benefits: it would be faster, less expensive and more inclusive (Sander, Reference Sander1985), more democratic (Bush and Folger, Reference Bush and Folger1994; Mayer, Reference Mayer2012), gentler (Bok, Reference Bok1983), more empowering (Beer and Packard, Reference Beer and Packard2012) and would help to preserve relationships (Moore, Reference Moore1986; Haynes and Haynes, Reference Haynes and Haynes1989). It quickly spread across the US, thanks in part to Sander's (Reference Sander1985) vision of the ‘multi-door courthouse’.

Such ringing endorsements provoked an inevitable backlash; at around the same time, a number of academic commentators held mediation up to a more critical light. This wave of scholarship is captured in Abel's (Reference Abel and Abel1982) collection, ‘The Politics of Informal Justice’, though others entered the fray (Nader, Reference Nader1979; Auerbach, Reference Auerbach1983; Fiss, Reference Fiss1984; Delgado, Reference Delgado1988; Luban, Reference Luban1995). Many of the scholars most critical of alternatives to the formal justice system were equally critical of the system itself, influenced by the critical legal studies movement. Their arguments, most of which remain ‘largely unchallenged’ (Roberts and Palmer, Reference Roberts and Palmer2005, p. 9) are set out below.

At the heart of academic critiques lies the accusation that alternative forms of dispute resolution fail to deliver justice, providing instead ‘poor justice to the poor’ (Abel, Reference Abel and Abel1982, cited in Cappelletti, Reference Cappelletti1993, p. 288, fn. 19). More recently, a prominent UK scholar asserted:

‘It does not contribute to substantive justice because mediation requires the parties to relinquish ideas of legal rights during mediation and focus, instead, on problem-solving …. The outcome of mediation, therefore, is not about just settlement it is just about settlement.’ (Genn, Reference Genn2012a, p. 411, emphasis in original)

In assessing the purported justice of dispute-resolution processes, the adversarial system and resultant judicial determinations tend to be presented as the gold standard (Nader, Reference Nader1979; Fiss, Reference Fiss1984; Luban, Reference Luban1995). Lawyer-negotiation, the mainstay of the justice system, is tolerated as ‘bargaining in the shadow of the law’ (Mnookin and Kornhauser, Reference Mnookin and Kornhauser1979). Mediation, however, is portrayed as a rogue process: unregulated, private, informal and, potentially, unfair (Frey, Reference Frey2000; Genn, Reference Genn2012b). Four persistent critiques can be identified in the literature: (1) informalism, (2) sources of norms, (3) confusion of fairness and justice, and (4) the distinction between procedural and substantive justice.

2.1 Informalism

The first wave of critical thinking about ADR tended not to distinguish mediation from other non-court processes such as arbitration; all were seen as ‘informal’. While informality had its attractions, critics were quick to point out its drawbacks.

2.1.1 Neutralising conflict

Nader argued that consumers were short-changed by informal processes, whose case-by-case approach left systemic abuses by powerful corporate interests unchallenged and unscrutinised (Nader, Reference Nader1979). Others were concerned about losing the deterrent impact of such scrutiny (Singer, Reference Singer1979; Budnitz, Reference Budnitz1994). Abel claimed: ‘informal institutions neutralize conflict by responding to grievances in ways that inhibit their transformation into serious challenges to the domination of state and capital’ (Abel, Reference Abel and Abel1982, p. 280). From this perspective, processes designed to reduce or resolve conflict play into the hands of elites whose interests lie in maintaining the status quo. Similar concerns are voiced by those who see mediation aiding neoliberal efforts to privatise and depoliticise the justice system (Resnik, Reference Resnik2002; Cohen, Reference Cohen2009a). Such critiques come from the left, political home of the critical legal studies movement (Delgado et al., Reference Delgado1985). They raise questions of their own: must a process deliver social equality to be considered just? And is that standard applied to courts and tribunals (Silbey, Reference Silbey2005)?

2.1.2 Expanding the reach of the state

Abel discerned a more sinister side effect of well-intentioned efforts to empower communities through mediation. Authorities could thereby ‘seek to review behavior that presently escapes state control’ (Abel, Reference Abel and Abel1982, p. 272). Harrington (Reference Harrington and Abel1982, p. 63) employed almost the opposite logic to assert that referrals to mediation amounted to ‘delegalisation’, expanding the reach of the state by removing these matters from judicial scrutiny. Others accused governments of seeking to co-opt mediation (Menkel-Meadow, Reference Menkel-Meadow1991; Engle-Merry, Reference Engle-Merry and Merry1993; Coy and Hedeen, Reference Coy and Hedeen2005), although such views may underestimate mediation's potential to support resistance to state power (Mulcahy, Reference Mulcahy2000).

2.1.3 Removing protection from the disadvantaged

Critics were also concerned about the loss of procedural protections, claiming that informal processes ‘provide advantaged plaintiffs with a sword to enforce their rights while denying disadvantaged defendants an equivalent shield’ (Abel, Reference Abel and Abel1982, p. 296). Engle-Merry observed judges and lawyers framing low-value disputes as moral dilemmas, ‘offering lectures and social services rather than protections or punishment’ (Reference Engle-Merry1990, p. 1). Grillo (Reference Grillo1991) made a highly influential claim that mediation's informality particularly disadvantages women and minorities (Menkel-Meadow, Reference Menkel-Meadow1997). Others have reached similar conclusions (Delgado et al., Reference Delgado1985; Noone and Akin Ojelabi, Reference Noone and Akin2014), although Reda (Reference Reda2010) distinguishes feminist critiques of mediation from ‘first-wave’ critiques such as Abel's in their focus on individuals rather than structure.

2.1.4 Loss of law

Fiss added a further complaint about the loss of legal formality: we lose the benefit of public judgments in developing societal norms, ‘reducing the social function of the lawsuit to one of resolving private disputes’ (Fiss, Reference Fiss1984, p. 1085). These sentiments have been echoed by scholars concerned about diluting the courts’ function in enunciating public norms (Luban, Reference Luban1995; Weinstein, Reference Weinstein1996; Resnik, Reference Resnik2002; Perschbacher and Bassett, Reference Perschbacher and Bassett2004; Cohen, Reference Cohen2009b). Fiss's arguments have been revived by UK academics (Genn, Reference Genn2012b; Mulcahy, Reference Mulcahy2013) and adopted by senior judiciary (Leveson, Reference Leveson2015; Lord Thomas of Cwmgiedd, 2015; Ryder, Reference Ryder2015). All deplore the potential harm caused by diverting cases to ADR and an ‘anti-adjudication and anti-law discourse’ (Genn, Reference Genn2012a, p. 409). Genn's views convinced the Scottish Civil Courts Review to limit judicial encouragement for mediation (Irvine, Reference Irvine2010).

This argument follows a seam of US scholarship on the ‘vanishing trial’, even though its author concedes that the reduction in full hearings is ‘not confined to sectors or localities where ADR has flourished’ (Galanter, Reference Galanter2004, p. 519). The vanishing trial has been critiqued for reflecting the justice industry's prejudices: ‘Like medieval astronomers who mapped the Earth as being the center of the universe, most professionals in the legal system – including lawyers, judges, and legal scholars – place the courts in the center of the world of conflict resolution’ (Lande, Reference Lande2005, p. 199).

This brief survey of the first wave of mediation critics highlights a range of issues bearing on justice and injustice: does mediation allow the powerful to evade scrutiny, bring government into more of our lives, work against the powerless and undermine a functional litigation system? Two unarticulated premises seem to underpin them all:

1 The legally disadvantaged – lay, unrepresented, poorly educated or simply poor – lack the ability to assert their own needs and to produce results that are fair and just. This empirical question will be discussed in Section 2.3.

2 The courts are the appropriate source of normative authority to be applied in disputes. This is both a political and a philosophical matter and will be discussed in the next section.

2.2 Legitimate sources of norms in litigation and mediation

In common-law systems, courts derive norms from two principal sources: legislation and judicial precedent. Both claim authority. Parliaments can point to their electoral mandate, courts to the logic of legal reasoning in real cases (although this has been questioned: Schauer, Reference Schauer2006). In principle, things are equally clear-cut for mediation. Norms pertaining to outcome come from the parties and the mediator's role is confined to process (Haynes and Haynes, Reference Haynes and Haynes1989; Mayer, Reference Mayer2012; Moore, Reference Moore2014). In this vision, whether a settlement is just or unjust is none of the mediator's business: the principle of self-determination leaves parties free to arrive at any outcome they choose (Stulberg, Reference Stulberg2005). Scholars, however, have questioned the empirical reality (Greatbatch and Dingwall, Reference Greatbatch and Dingwall1989; Coben, Reference Coben2004) and theoretical desirability (Rifkin et al., Reference Rifkin, Millen and Cobb1991; Astor, Reference Astor2007; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer2012) of mediator neutrality.

An alternative approach would be to see mediators as a potential source of normative guidance. Riskin contrasts the ‘facilitative’ style, where mediators assume parties can solve their own problems given a helpful process, with the ‘evaluative’ style, where mediators with legal expertise believe their evaluation will help parties achieve settlement (Riskin, Reference Riskin1996; Reference Riskin2005). The evaluative/facilitative debate has had huge resonance within the mediation community (Wall and Chan-Serafin, Reference Wall and Chan-Serafin2014; Rubinson, Reference Rubinson2016). An alternative view is that wider social norms guide parties’ decision-making (Waldman, Reference Waldman1997; Belhorn, Reference Belhorn2005). Waldman divides mediators into ‘norm-generating’ (‘disputants … generate the norms that will guide the resolution to their dispute’) (p. 708), ‘norm-educating’ (mediators provide normative guidance but parties ultimately decide) (p. 727) and ‘norm-advocating’ (mediators ensure outcomes conform to legal or regulatory norms) (p. 745). Both Riskin and Waldman acknowledge that mediators may change style from context to context, suggesting a situational dimension to any mediator guidance.

Some see legal information or advice as the guarantee of informed consent (Nolan-Haley, Reference Nolan-Haley1999; Korobkin, Reference Korobkin, Moffitt and Bordone2005). For others, this is impractical and wrong: if anything trumps self-determination, even the mediator's sense of fairness or justice, party autonomy is compromised (Stulberg, Reference Stulberg1998; Bush and Folger, Reference Bush and Folger2005). A key battleground in these debates is the appropriate source of normative guidance in mediation. Scholars have tended to assume that such guidance can only come from the ‘juridical field’, characterised by Bourdieu as ‘the site of competition for monopoly of the right to determine the law’ (1987, p. 817). It includes judges, lawyers and jurists: ‘an entire social universe which is in practice relatively independent of external determinations and pressures’ (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1987, p. 816). It may conceivably include lawyer mediators providing evaluative guidance.

Little attention has been paid to parties themselves: what weight, if any, should be granted to their justice judgments? Do they look to mediators to inform them about social and legal norms? Or do they see themselves as best placed to select the standards by which mediation outcomes should be evaluated? Put more simply, can we, should we and do we trust lay people to decide what is fair and just?

2.3 Justice and fairness

2.3.1 Etymology

Much of the discussion above employs the terms ‘fairness’ and ‘justice’ interchangeably. Yet the two English words have distinct tones of meaning. ‘Justice’ derives from French and Latin, languages of the king and the court, of authority and officialdom. ‘Fairness’, on the other hand, is a Norse word originating in the visual qualities of a longboat's ‘fair’ payload (Wilson and Wilson, Reference Wilson and Wilson2006). It is everyday and self-evident, not dissimilar to reasonableness (Wheeler, Reference Wheeler2014). Anyone may have a view on fairness, whereas justice embodies the means by which the state applies and enforces the law: it is the prime Aristotelian virtue (Reid, Reference Reid2008), the ‘virtue of the magistrate’ (Aristotle, Reference Aristotleno date). Fairness, then, is ‘bottom-up’ – a universal urge but subjective standard; justice is ‘top-down’, emanating from societal elites yet aspiring to set universal standards.

Most have little difficulty in accepting that ordinary people understand fairness, while regarding justice as the domain of legal professionals (a view echoed in Bourdieu's (Reference Bourdieu1987) critique of the juridical field). Little wonder, then, that critics express concern when legal systems adopt processes allowing lay people to determine outcomes – a role hitherto reserved for state-appointed judges.

2.3.2 Criteria for evaluating justice and fairness

Some scholars see litigation as the benchmark for the quality of justice achieved in mediation (Sabatino, Reference Sabatino1998; Frey, Reference Frey2000); others see the two processes as alternatives, justice in court coming from ‘above’, mediation being more ‘horizontal’ (Hyman and Love, Reference Hyman and Love2002, p. 160) or ‘justice from below’ (Stulberg, Reference Stulberg2005, p. 5). A related debate asks whether mediators should tilt the justice playing field to protect the ostensibly less powerful party. Responses range from not at all (Stulberg, Reference Stulberg2012) through a relatively thin vision in which mediators intervene where agreements ‘are so one-sided and unfair that they shock the conscience’ (Waldman and Akin Ojelabi, Reference Waldman and Akin2016, p. 423) to acceptance of mediator influence to ensure compliance with legal norms (Carmichael, Reference Carmichael2013). Like their critics, those defending mediation's fairness credentials appear to echo ‘the complacent assumption among jurists that state law is the most influential source of normative order in society’ (Tamanaha, Reference Tamanaha2019, p. 173).

Even where attention is paid to non-legal norms, the mediator is often presented as a guarantor of fairness, while parties’ views are characterised as subjective (Hyman, Reference Hyman2014, p. 34) or merely the opinions of ‘lay’ people (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1999; Shestowsky and Brett, Reference Shestowsky and Brett2008). Colatrella proposes twin standards: first, an outcome ‘is “fair” if the participants deem it acceptable’; second, the mediator must find it ‘sufficiently and substantively fair too’ (Reference Colatrella2014, p. 715). Waldman differentiates ‘self-determination theorists’ from ‘social norm theorists’, the latter less optimistic about the human capacity to reach just decisions and more concerned about inequality and power (Reference Waldman2004, p. 250).

2.4 Procedural and substantive justice

Genn's complaint about mediation focused on its capacity to deliver ‘substantive justice’ (2012a, p. 411). This describes the outcome of a process; the fairness of the process itself is known as procedural justice. Across multiple cultures and contexts, procedural justice is a more reliable predictor of party satisfaction than substantive justice (Brockner et al., Reference Brockner2001; Lind, Reference Lind, Greenberg and Cropanzano2001; MacCoun, Reference MacCoun2005; Solum, Reference Solum2005; Tyler, Reference Tyler2006; Bollen et al., Reference Bollen, Ittner and Euwema2012; Nolan-Haley and Annor-Ohene, Reference Nolan-Haley and Annor-Ohene2014). Despite critiques of its conclusions on the grounds of confirmation bias (Silbey, Reference Silbey2005), attribution errors (Collett, Reference Collett, Hegtvedt and Clay-Warner2008) and research design (Creutzfeldt and Bradford, Reference Creutzfeldt and Bradford2016), this research offers evidence of what people value in dispute-resolution processes:

1 Voice: the opportunity to present views, concerns and evidence to a third party (Brockner et al., Reference Brockner2001; Lind and Arndt, Reference Lind and Arndt2017).

2 Being heard: the perception that the ‘third party considered their views, concerns and evidence’ (Welsh, Reference Welsh2001, p. 820).

3 Treatment: dignified and even-handed (MacCoun, Reference MacCoun2005).

Unsuccessful litigants are more likely to rate themselves satisfied when they believe they have been fairly treated: ‘fair procedures are a cushion of support against the potentially damaging effects of unfavourable outcomes’ (Tyler, Reference Tyler2006, p. 101). Welsh (Reference Welsh2001) believes mediation can offer a procedurally fair experience, leading parties to feel valued and respected.

2.5 Conclusion: a critical response to the critics

These scholarly debates should give pause to even the most starry-eyed mediation enthusiasts. A recurring concern is that participants with the least bargaining power will end up with ‘less’ than they would have received from a judge. Does this mean that mediation should not be practised when one party is disadvantaged in some way? How would disadvantage be measured? Below-average income? Failing to attain a certain educational level? The range of potential disadvantages could include gender, cultural heritage and structural factors like occupying a lower place in an organisational hierarchy (Delgado et al., Reference Delgado1985; Seth, Reference Seth2000).

One contextual factor often overlooked by mediation's critics is that those with the least power and resources are also unlikely to fare well in the courts (Wexler, Reference Wexler1970; Sarat, Reference Sarat1990). It is not simply a matter of income poverty: Galanter famously set out the range of practical and systemic challenges faced by ‘one-shotters’ pitched against ‘repeat players’ in litigation, severely limiting the courts’ redistributive capacity (1974, p. 97). Sandefur (Reference Sandefur2008) identified a range of complex, interrelated factors limiting poor people's successful use of legal institutions, including social status, feelings of disentitlement and previous negative experiences. Studies highlight the impact of poor or no representation on outcomes (Seron et al., Reference Seron2001; Yoon, Reference Yoon2009; Quintanilla et al., Reference Quintanilla, Allen and Hirt2017). In an imperfect world, mediation may deliver less than perfect justice, but so may litigation and other processes touched by the logic of the market.

The notion of obtaining ‘less’ raises further problems. By what criteria should outcome be evaluated? And by whom? To ensure that the disadvantaged do not do worse at trial, a mediator would require a judge's legal knowledge and the means to take evidence under oath and probe competing accounts. One may as well run the trial.

And, if the mediator does tilt the playing field to protect the ostensibly weaker party, inescapably, s/he tilts it against the other party. Mediation's critics have paid little attention to ‘advantaged’ participants; here again, how to measure advantage? Rhetoric on this issue often juxtaposes a poor, unrepresented individual with a major utility or multinational bank. But legal claims can equally involve two small businesses; or a self-employed tradesperson and a retired professional couple; or a company in financial difficulty and a late-paying customer. Who is disadvantaged and, once again, who should decide? More pragmatically, if mediators make efforts to support one party, how will the other party view a process that claims to be consensual yet seems weighted against them?

Most problematic of all is that the ‘less’ critique fails to judge mediation on its own terms. Mediation claims to empower participants to make informed choices. This goes beyond simple preference: mediators generally invite people to choose not only the outcome to their dispute, but also the criteria by which that outcome is evaluated (Waldman, Reference Waldman1997). This complex form of thinking involves finely tuned judgments about personal and community norms as well as factors like expectation, risk, commitment and personal resources. Little attention has been paid to that thinking.

Mediation scholarship appears to have fallen into the habit of assuming that ‘lay’ people's lack of legal knowledge effaces their capacity for thinking about substantive justice. Studies involving participants tend to focus on factors such as satisfaction, improved relationship and procedural justice (Wissler et al., Reference Wissler2002; Eisenberg, Reference Eisenberg2016; Charkoudian et al., Reference Charkoudian, Eisenberg and Walter2017). Where substantive justice is considered, the views of lawyers predominate (Genn et al., Reference Genn2007), fulfilling Bourdieu's prediction that the juridical field maintains its monopoly through ‘the disqualification of the non-specialists’ sense of fairness’ (Reference Bourdieu1987, p. 828).

It is thus timely to investigate the thinking of non-legal actors in disputes where they are the decision-makers. Small claims, with its preponderance of unrepresented parties, provides an ideal setting. The study described below took place with people referred to mediation in Scotland's civil courts. The research question is: ‘What is the place of justice in the thinking of small claims mediation participants?’

3 The study: Scotland

Scotland is an unusual jurisdiction. A nation with a 1,000-year history (Davis, 1999, pp. 263–265), union with England in 1707 meant that, for almost 300 years, Scotland had its own legal systemFootnote 1 without its own legislature (Smith, Reference Smith and McCormack1970) until 1999, when the Scottish Parliament was re-established. Its highest civil court is in London. Scots law, with roots in European canon and civil law (Reid, Reference Reid2008), has thus been overlaid with judicial decisions reflecting the English common-law tradition and is now generally categorised as a ‘mixed’ legal system (Reid, Reference Reid2003; but see Osler, Reference Osler2007).

Scotland also stands apart from a striking recent development across the common-law world: the growth in ADR (King et al., Reference King2014). Despite the passage of the Arbitration (Scotland) Act 2010, only twenty-two arbitrations took place between July 2013 and June 2014 in a country of 5.4 million people (Auchie et al., Reference Auchie2015). And, after positive early endorsement of family mediation, including confidentiality legislation (Civil Evidence (Family Mediation) (Scotland) Act 1995), judges and much of the legal profession have shown indifference or hostility towards general civil mediation (Ross, Reference Ross and Alexander2006; Ross and Bain, Reference Ross and Bain2010; Clark, Reference Clark2011). In contrast to the Woolf reforms in England and Wales, the last major review of Scottish civil justice rejected judicial encouragement for ADR (Scottish Civil Courts Review, 2009, pp. 172–173; Irvine, Reference Irvine2010). Mediation is attempted in less that 1 per cent of non-family civil litigation (Civil Justice Statistics in Scotland 2015–16, p. 62). A senior Scottish judge (now on the UK Supreme Court) typifies judicial attitudes: ‘it would not be right to require persons who wish a legal solution of their dispute to participate in a process which is far from pure in its application of legal principle’ (Lord Reed, 2007, cited in Irvine, Reference Irvine2012).

Nonetheless, some within the justice system favour greater use of ADR. In 2013, the Law Society issued guidance to the effect that solicitors should be able to advise clients on ADR options (Law Society of Scotland, Guidance in relation to Rules B1.4, B1.9: Dispute Resolution). Scotland's Employment Tribunals have offered judicial mediation since 2009. A small-claims mediation scheme has existed in Edinburgh Sheriff Court since 1998. And, in 2016, new rules came into force requiring judges to encourage ADR in actions of up to £5,000 (Act of Sederunt (Simple Procedure) 2016, SSI 2016/200) – a significant and surprising innovation (Irvine, Reference Irvine2016).

What lies in the future for ADR in Scotland is hard to predict. The Simple Procedure rules were followed by similar encouragement for ADR in commercial actions (Court of Session Practice Note 1 of 2017 – Commercial Actions, p. 11). Yet this is absent from the general civil procedure rules (Scottish Civil Justice Council, 2017) and a 2013 review of the costs of litigation managed to avoid a single reference to ADR in its 334 pages (Taylor, Reference Taylor2013). There is evidence that wider debates about the efficacy and fairness of ADR have influenced Scottish policy-makers (Irvine, Reference Irvine2010). There has, however, been a notable lack of empirical research into mediation in Scotland's civil justice system.

To address this gap, I initiated a qualitative study of small-claims mediation in Glasgow and Edinburgh Sheriff Courts. The pilot phase took place in 2016 under the older small-claims rules. Sheriffs (judges) referred cases to mediation at a procedural hearing; parties were encouraged but not compelled to take part. The full study, including parties referred to mediation under the new Simple Procedure rules, is currently underway.

3.1 Methodology

A philosophical difficulty is engendered by applying social-science methods to matters falling within law's domain. Law seeks to provide a normative system applicable to everyday life (McCoubrey and White, Reference McCoubrey and White1996). It is prescriptive. Its epistemology is deductive, enabling those skilled in its methods to deduce what is just in particular situations (Halpin, Reference Halpin2006).

Justice is both a psychological and a legal concern. However, insofar as courts and other legal actors seek binding rules from justice events, they engage in a form of ontological transformation (Teubner, Reference Teubner1989): subjective judgments about disputes become sources applicable across whole societies and, in the process, acquire objectivity. The doctrine of legal precedent crystallises this transformation, providing a public good argument for dispute resolution via courts: ‘from the moment a body of precedents is formed, an unlimited number of individuals can make use of this legal corpus and derive from it the entire diversity of attendant utilities’ (Bilsky and Fisher, Reference Bilsky and Fisher2014, p. 82). The doctrine of legal positivism, seeing law as rules, reinforces the idea that justice can only come from official sources (Farrell, Reference Farrell2006; Dwyer, Reference Dwyer2008; Samuel, Reference Samuel2009).

Social science, whether realist or idealist, tends to reject normativity in favour of description. Its epistemology is inductive (Ritchie et al., Reference Ritchie2014): phenomena need to be observed prior to the development of theory and principles. The constructivist turn sees the social world as produced by social interaction, and subject to revision (Grix, Reference Grix2010). Thus, the empirical study of legal matters faces a challenge that is both principled and practical: how to avoid diminishing either law's deductive, normative approach or the inductive, descriptive tradition of the social sciences. Legal scholars run the risks of a closed system, uncorrected by empirical data. And social scientists risk discounting legal ontology, missing law's normative intentions (Pavlakos, Reference Pavlakos2004). The study described in this paper can be located within empirical legal studies (Menkel-Meadow, Reference Menkel-Meadow, Cane and Kritzer2006; Hillyard, Reference Hillyard2007; Webley, Reference Webley, Cane and Kritzer2010; Epstein and Martin, Reference Epstein and Martin2014), defined as ‘the study through direct methods of the operation and impact of law and legal processes in society’ (Genn et al., Reference Genn, Partington and Wheeler2006, p. 3).

The complexity of the research question (examining both justice and thinking about justice) lends itself to a qualitative approach: semi-structured interviews (King, Reference King, Cassell and Symon2004; Ritchie et al., Reference Ritchie2014, p. 4). In this interpretive tradition, reality is viewed as subjective, and mediated by senses and consciousness. Language does not simply describe the world, but shapes our view of what can exist. Meaning is not discovered; it is constructed by ‘interaction between consciousness and the world … truth is a consensus formed by co-constructors’ (Scotland, Reference Scotland2012, p. 12). Interviews explored the life history of disputes, from their inception in ‘naming, blaming and claiming’ (Felstiner et al., Reference Felstiner, Abel and Sarat1981) through the raising of court action and the experience of mediation to resolution or otherwise.

Participants were individuals taking part in small-claims mediation in Scotland's two largest courts (Glasgow and Edinburgh Sheriff Courts). During the pilot phase, I conducted five face-to-face interviews. None of the cases had a value greater that £3,000. Three concerned unpaid bills, one goods and services, and one a landlord/property-agent dispute. Three settled and two did not. Three participants were male and two female. None was legally represented in mediation, although one employed a lawyer for court hearings.

Interviews lasted an average of forty-six minutes and were semi-structured. They were recorded, transcribed, then analysed using thematic analysis (Miles et al., Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldana2014). The goal of this approach is to build theory rather than to test it, so as to remain open to new insights emerging from the data (Ajjawi and Higgs, Reference Ajjawi and Higgs2007).

3.2 Findings

These are grouped into themes and illustrated by extracts from the data. Four follow justice issues identified in the literature review: procedural justice, fairness and justice (goals), fairness and justice (evaluation) and the limitations of mediation. A fifth, unanticipated, theme emerged and is included for its explanatory power in relation to mediation's success: participants’ self-presentation.

3.2.1 Procedural justice

Researchers have generally been willing to cede to lay people the capacity to determine the fairness of a process (as distinct from its outcome): most procedural justice research is conducted with non-lawyers (see Section 2.4 above). Before examining substantive justice, it is valuable to consider whether participants believed they had been fairly treated; Welsh (Reference Welsh2002) sees this as a baseline or minimum standard for mediation.

These Scottish participants appeared to believe their voice had been heard. One said: ‘It gave me an opportunity to put my point across.’ However, being heard by the mediator was less important than being heard by their opponent:

‘It gave an opportunity cos, prior to that point, you, you're not having conversations directly with the other party.’

‘I can't remember who spoke first but we both did speak and we spoke quite a lot, you know what I mean.’Footnote 2

This runs counter to much procedural justice research, in which the legitimacy of a process turns on the behaviour of an authority figure/decision-maker (though see Nesbit et al. (Reference Nesbit, Nabatchi and Bingham2012) for a similar finding). In a process in which parties are themselves decision-makers, fairness may depend more on the opportunity to be heard by one's counterpart.

3.2.2 Fairness and justice – goals

Respondents were asked about their goals for raising or defending a small claim. Their answers reveal a wide range of considerations, including pragmatism, principle, complaints handling, risk, hassle, precedent and even the public interest, similar to those of represented parties in Relis's (Reference Relis2007) study of Canadian medical-negligence mediation.

For example, one participant appeared to have some form of precedent in mind: ‘Those judgements collectively, if they're used properly, can actually improve things.’ A business defender, whose case had not settled, spoke of the importance of good complaints handling:

‘You know, kind of … are we being responsible? Have we been professional? Because sometimes we do things wrong and if we do things wrong I think that it's fair that we have to offer some form of compensation for it.’

Another participant reflected a principle embedded in Scots law: restitution, where a person harmed by another is restored to the position they would otherwise have enjoyed: ‘I'm quite happy to take … not be out of pocket from what I intended.’

3.2.3 Fairness and justice – evaluation

At the heart of the research lies the question of substantive justice: did lay people see the mediation outcome as fair and/or just? Interviews employed both terms given their rather different meanings (see Section 2.3.1 above). As well as discussing fairness, participants were asked the direct question: ‘Did you get justice?’ One woman, who settled for considerably less than she claimed, replied: ‘I think I got more than justice. I think I got, em … I don't want to say teach him a lesson but, you know he, he needed to learn that he can't just get away with things.’

This statement reflects not so much a punitive motivation as a didactic one: people learn lessons from justice events and the financial penalty drives the lesson home.

If the other party was seen as particularly blameworthy, for example a professional who should adhere to higher standards, the punitive motivation was fiercer:

‘I'd actually said to the lawyer … look even if this costs me £5000 it doesn't matter because what they have done is despicable …. And this woman's a lawyer, she should know better. Well, had she been a lay person, I might have taken a different view.’

This response echoes findings that medical-negligence claimants sought a large monetary award not (or not only) for compensation, but to punish and deter errant doctors (Relis, Reference Relis2009).

At the same time, a distinctive feature of mediation is that outcomes are consensual. No matter how strongly one party feels, they must also convince the other to settle. The punitive urge could thus be tempered by pragmatism and a sense of reasonableness:

‘Did I feel that he could have gone a bit further? Well, I took a view – it's reasonable we're meeting in the middle, can he be squeezed any more? And knowing [Defender] I thought, well, you could well squeeze him and he'll go the other way. So a bird in the hand.’

‘there was justice. Absolute justice, if there is such a term, would have been that I would have got the full amount.’

Unsurprisingly, mediators played a part in brokering these settlements. One response chimes with US research revealing mediators’ focus on lowering client aspirations:

‘the only reason I think anyone would accept a vastly reduced sum, because that's what it is, in mediation would be because the mediator's saying, look, when you go to court, it's a 50/50, there's no guarantees (LAUGHS) one way or the other … and it's probably not worth the aggro …. You'd be as well accepting it.’ (Wall and Kressel, Interview, Reference Wall and Kressel2017)

This excerpt illustrates the complex decision-making that unrepresented people face in mediation. They must juggle their sense of how much they are entitled to, the practical challenges they face in recovering it (‘the aggro’), the risk of failure (‘no guarantees’) and the effort already expended in getting the other party to offer anything at all – the sunk costs of time spent on the case.

One source of the concern that lay people will settle for ‘less’ is the view that natural sympathies will cloud their judgment in ways to which judges are inured (Maroney, Reference Maroney2011). Participants did demonstrate signs of empathy, but responses indicate a careful weighing-up of competing factors rather than a straightforward emotional reaction: ‘I felt he was quite vulnerable and he was quite … he'd just got a, a new baby and … I just thought, well, he's learned his lesson basically, he'll not do that in a hurry again.’

Another described how the defenders, a medium-sized company, had sent a young graduate to represent them. Apparently, this influenced his decision to mediate: ‘I thought – this lad's wet behind the ears, this could be a good thing to go for it (LAUGHS).’

Such tactical considerations may seem unconnected to either fairness or justice, but will be recognisable to legal professionals versed in the idea of litigation as a game (Galanter, Reference Galanter1974; Bok, Reference Bok1983). Unrepresented people can also take a strategic view of dispute-resolution processes.

3.2.4 Mediation's limitations

One participant with a positive view of the outcome nonetheless spoke of wishing for a more public setting:

‘one slight regret I've got on that moral issue of somebody challenging their terms and conditions and such like in court and getting them to understand it … there was a lack of, em, ombudsman type services that could have done a quasi-legal review … there was this jump from the one to one, sort of, between myself and the company … then the next redress had to be at the small claims level rather than at a level beneath. And that was a gap I felt.’

This small claimant echoes concerns about ADR's privacy and the loss of a public declaration of norms (Section 2.2 above). He suggests that an ombudsman scheme, a ‘level beneath’ the courts, could ensure that companies are publicly named and shamed to discourage them from repeating offending behaviour. While this perspective highlights a troubling issue for mediation, it underlines the point that ‘lay’ people's justice reasoning extends beyond their immediate interests.

3.2.5 Fairness and justice – self-presentation

As well as reporting what is said, qualitative research emphasises the work language is doing: ‘the world is made, not found’ (Pearce, Reference Pearce2006, p. 7). Respondents do not simply relate objective facts; they co-construct, with the interviewer, a version of reality that may fulfil other purposes. This was evident in participants’ statements about the fairness of their own actions:

‘I said, this is where I will meet and I said, I think this is fair. I said, I will meet in the middle and it's £500.’

‘It's made me feel as if I'm, eh, quite a nice person, to be quite honest with you. I'm fair … it's my personal position, you know what I mean. I, I dislike social injustice. I really dislike it. So I'm quite thingmyFootnote 3 on things like that.’

‘I didn't chase them for the 5 hours delay. I chased them for the extra cost beyond that which … which had been incurred.’

Here, the respondent demonstrates his own fairness by describing what he could have sued for but didn't. Mediators often hear this sort of self-justification. It speaks of the need to be seen as fair, not only by others, but also in one's own self-image; these may be factors in the eventual outcome.

Participants tended to provide arguments for evaluating their own behaviour, potentially attempting to convince the interviewer (‘the tribunal of the man without’) and perhaps themselves (‘the tribunal of the man within’) (Smith, Reference Smith1759/1976, pp. 130–131) of their fairness. They were thus evaluating not only the outcome, but also their own contribution to it, and answering a question not put to them: ‘What kind of person are you?’ This species of question has been found particularly influential in motivating people to participate in mediation (Sikveland and Stokoe, Reference Sikveland and Stokoe2016, p. 247). It may play an equally strong role in achieving settlement. By the time disputes reach the courts, parties may not care what their adversary thinks, but probably want to be seen in a good light by the mediator. Clearly, they also want to see themselves in a good light.

3.2.6 What do the findings tell us?

These findings contradict the idea of mediation as simple horse-trading between two financial positions; rather, it is a complex web of factors and people. In the next section, I propose ways of conceptualising ordinary people's justice reasoning.

4 Discussion: how might we account for lay people's answers to questions about justice in mediation?

4.1 The social construction of fairness and justice

Ordinary citizens faced with the opportunity to negotiate substantive outcomes to their disputes described a wide range of criteria to explain or justify their decisions. These included: recompense for loss; punishment of bad behaviour; teaching someone a lesson (deterring future poor behaviour); holding businesses to account; pragmatism (how far the other party can be pushed); risk of further proceedings; empathy for the other party; reasonableness; and the urge to be, or be seen to be, a fair person.

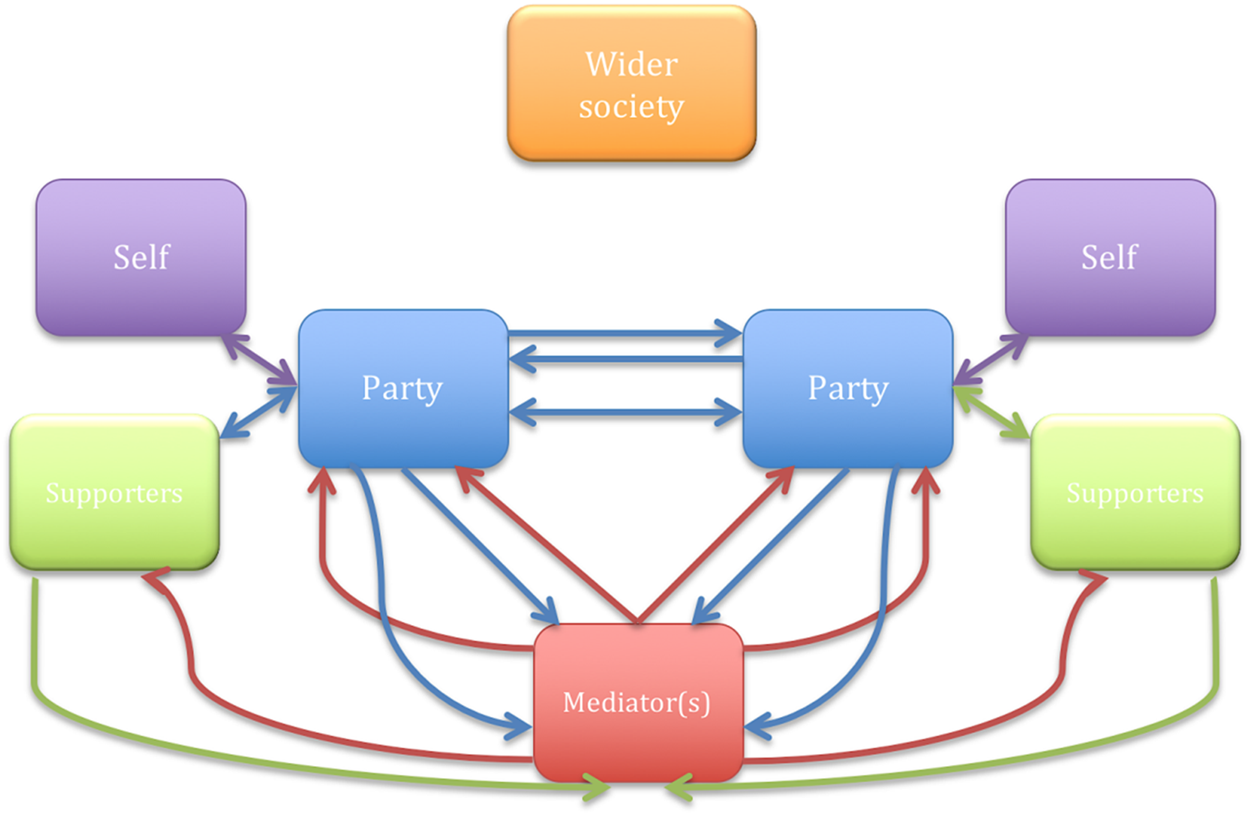

In Figure 1, this complex matrix of decision-making is conceptualised as a multiparty negotiation. Parties negotiate with the mediator; the other party; their supporters; the wider community; and, to an extent, themselves. All of these conversations may be one-way (monologue), two-way (dialogue) or include three or more parties (facilitated dialogue), and may be private or public. Wider society is also shown. One practice model, narrative mediation (Winslade and Monk, Reference Winslade and Monk2002), overtly acknowledges the impact of societal discourse on possible outcomes.

Figure 1. Matrix of fairness and justice negotiation

In this negotiation process, as in real-world litigation, fairness is not fixed. It is a social construction (Macfarlane, Reference Macfarlane2001; Paul and Dunlop, Reference Paul and Dunlop2014) refined through discourse: the interaction provided by the mediation setting. Court judgments are also socially constructed (Silbey, Reference Silbey2005; Schauer, Reference Schauer2006; Finnis, Reference Finnis2011). Judges often disagree in significant cases and minority reports present plausible counter-arguments. Judicial opinions are addressed as much to the wider legal system as to litigants.

Judges, however, are disinterested participants in legal disputes. By contrast, the model above presents mediation as a multiparty negotiation involving interested parties (litigants, representatives, supporters) and a disinterested facilitator (the mediator). Does this prevent it from arriving at just outcomes? While the results have been characterised as ‘subjective’ (see Section 2.3.2 above), Seul (Reference Seul2004) argues that negotiated settlements are capable of producing outcomes that are as just, from a societal viewpoint, as those produced by trials. Sturm proposes that court-ordered conflict resolution by non-legal actors can result in ‘efficient, fair, and workable norms’ (Reference Sturm, Neilson and Nelson2005, p. 50).

4.2 Implications for theories of justice

Justice overlaps with, but is not identical to, legality (Gardner, Reference Gardner2018). While the ‘shadow of the law’ plays an important part in lawyer-negotiation (Mnookin and Kornhauser, Reference Mnookin and Kornhauser1979), justice exists outside the legal system. Society could not function if the courts had to be consulted on every decision touching on fairness and justice, and the adversarial system has long encouraged negotiated settlements (Galanter, Reference Galanter1988). Mediation parties may indeed be ill-informed about legal rules; participants in the present study made little mention of the law. They appealed to ethical or moral norms: holding bad behaviour to account; achieving restitution; teaching the offender a lesson; behaving fairly; discouraging others from behaving badly. They also displayed tactical awareness (not unlike legal practitioners): exploiting inexperience, not provoking resistance, assessing the costs and benefits of continuing the dispute.

Alasdair MacIntyre once complained that academic philosophy had become so complex that most people believed it had nothing to offer them: ‘The attempted professionalization of serious and systematic thinking has had a disastrous effect upon our culture’ (Reference MacIntyre1988, p. x). That accusation could equally be levelled at law and lawyers. The professionalisation of serious and systematic thinking about justice is not a new endeavour (Pound, Reference Pound1944), but it may blind us to other sites of justice reasoning.

Critical work on ADR, emanating largely from the legal academy, tends to replicate the hierarchical structure of the justice system itself: ‘superior’ courts at the top, supported by a pyramid of appellate and ordinary courts; below them, another pyramid of legal professionals; at the bottom, ‘lay’ people (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy1982; Arthurs, Reference Arthurs1985). Those people's capacity for serious and systematic thinking, or indeed any thinking about justice, is generally regarded through a lens of paternalistic concern. Raz noted law's claim to ‘provide the general framework for all aspects of social life’ (Reference Raz1975, p. 154). In this view, if non-lawyers do think about justice, it is only to advance their own cause or avoid trouble.

The law's hierarchical logic may derive from another era when its purpose was ‘to ensure deference by the lower orders to the world-view of the higher’ (Arthurs, Reference Arthurs1985, p. 6). Galanter also notes ‘the pretensions of the official law to stand in a relationship of hierarchic control to other normative orderings in society’ (Reference Galanter1981, p. 20). It seems oddly out of step with contemporary democratic societies where each vote carries equal weight and little deference remains. Mediation's early pioneers made great play of its egalitarian and democratic credentials (Menkel-Meadow, Reference Menkel-Meadow1991, p. 6). Critics, however, have tended to portray this as naive, warning that empowering ordinary people to make their own decisions would simply lead to exploitation of the vulnerable (see Section 2.1.2 above). The idea that lay people might be capable of producing just results seems not to have occurred to them, far less that those results may have derived from a set of norms that includes, but is not limited to, the law.

This may be because jurisprudence, the theory of law, struggles to account for ‘bottom-up’ normativity. The hierarchical universe set out by Arthurs is evident within legal positivism with its efforts to derive rules from a ‘basic norm’ (Kelsen, Reference Kelsen1967, p. 46) or ‘ultimate rule of recognition’ (Hart, Reference Hart1961, p. 100). One of legal positivism's avowed goals is to keep law separate from everyday moral reasoning, to study what law is rather than what it ought to be (Kelsen, Reference Kelsen1934, p. 477). Non-lawyers’ views about fairness and justice are thus rendered interesting but irrelevant.

The ancient natural-law tradition may prove more apt in conceptualising lay people's thinking about justice. The idea of discerning how just the law is goes back at least to the time of Plato (Rommen, Reference Rommen and Hanley1936/1998), but it was the Roman jurist Cicero who most clearly articulated the role of human reason in this endeavour:

‘True law is right reason in agreement with nature; it is of universal application, unchanging and everlasting; … We cannot be freed from its obligations by senate or people, and we need not look outside ourselves for an expounder or interpreter of it.’ (Reference Cicero and Keyes1961, III, xxii)

Cicero sees law as deriving from everyday moral reasoning rather than superior to it. Later, natural-law theory is associated with religion, but rationality remained central. Scots law's founding father, Viscount Stair, declared ‘Law is the dictate of reason’ (Stair, Reference Stair1681, 1, 1, 1). As Europe secularised following the Enlightenment, the role of reason in justice was articulated afresh. Adam Smith saw our sense of justice as innate and mysterious: ‘somehow or other, we feel ourselves to be in a peculiar manner tied, bound and obliged to the observation of justice’ (1759/1976, p. 80). Later, natural lawyers lend support to the idea that moral reasoning about justice precedes rather than derives from legal rules. Fuller refers to ‘the morality that makes law possible’ (Reference Fuller1969, p. 89).

This paper does not seek to revisit the complex debate between natural-law theory and legal positivism. A natural-law approach, however, does have potential in accounting for the role of justice in mediation. It links reason and justice, and brings both to bear in evaluating substantive legal rules (as do contemporary lawyers, claims Gordon (Reference Gordon1999)). It seems a good fit with mediation models that place the parties as decision-makers and express faith in human rationality (Irvine, Reference Irvine2007). Other approaches may also prove fruitful, such as identity theory (Stets and Osborn, Reference Stets and Osborn2008), the notion of moral community (Deutsch, Reference Deutsch, Coleman, Deutsch and Marcus2014) or Gilligan's (Reference Gilligan1982) ethic of care/ethic of justice dichotomy.

4.3 Limitations

The small sample means further investigation is needed to test its conclusions (the full study of twenty-four participants is underway). Scotland's new Simple Procedure rules mandate greater judicial encouragement for ADR (Scottish Statutory Instruments, 2016). Thus, they create ideal conditions for enriching our understanding of ordinary people's thinking about a justice event in which they are primary decision-makers. Further research should examine non-lawyers’ thinking about justice in other contexts and cultures.

5 Conclusion

Scotland provides a distinctive backdrop for the empirical study of mediation and justice. Its legal institutions have until now provided little encouragement for alternatives to litigation. It is therefore a useful setting in which to consider the perspectives of mediation participants with few preconceptions and a distinct lack of lawyer briefing.

Despite Genn's (Reference Genn2012a) ringing dismissal of mediation as having anything to do with justice, the concept is central to much mediation and conflict-resolution literature. The formal justice system is a key battleground, with critics alleging the process dilutes cherished values like the right to a fair trial while appearing to empower individuals. While lay people's views have been widely canvassed on procedural justice, researchers have tended to leave substantive justice to lawyers. Genn et al.'s (2007) study devotes nine pages to lawyers’ views on mediation and three to those of the parties.

If we are to account for ordinary people's thinking about justice, we need a thicker description than the lay/professional distinction. To characterise that thinking as subjective is to grant legal rules an objectivity belied by the existence of courts and disputes. Natural-law theory, with its emphasis on human rationality, may provide a foundation for conceptualising non-lawyers’ justice reasoning; legal positivism seems likely to reject that reasoning as failing to emanate from or contribute to legal rules (Gordon, Reference Gordon1999).

To return to the question posed in the title, the lay people in this study seem not to consider ignorance of legal rules a barrier to achieving justice. They have their criteria for evaluating whether they got a fair result; Figure 1 characterises this as a complex internal and external negotiation. As for whether they got justice, most conceded mixed feelings: on the one hand not ‘absolute justice’, on the other ‘more than justice’. I do not suggest that lay people's thinking on justice should supplant legal rules. Mediation does, however, offer an opportunity for justice to be co-constructed between disputing parties, advisers, mediators, the courts and wider society.

Conflicts of Interest

None

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Prof. Jane Scoular and Dr Saskia Vermeylen at the University of Strathclyde for their feedback on an earlier draft of this paper.