1 Introduction

The origins of the modern manifestation of alternative/appropriate dispute resolution (ADR) in Australia are firmly grounded in a concern to improve access to justice (Access to Justice Advisory Committee, 1994). An aspect of the 1960s and 1970s access-to-justice movement was the establishment of ADR institutions such as ombudsmen services, specialist tribunals and community/neighbourhood justice centres (Law Reform Committee, 2009, p. 19). Then, in the 1980s and 1990s, the incorporation of ADR processes into more formal court structures was actively encouraged by governments as one solution to improving access to justice for the community (Access to Justice Advisory Committee, 1994, pp. 279, 300). In the subsequent three decades, ADR institutions and processes have become an accepted part of the Australian civil justice system.Footnote 1

Despite these developments, there remain many in the community who are unable to access justice (Law Council of Australia, 2018). Additionally, some practitioners and commentators have concerns about what form of justice is delivered in different ADR processes and whether ADR benefits some more than others. In this paper, we explore, within the Australian civil justice system, whether ADR developments have enhanced the community's access to justice and argue that, although ADR and access to justice are significantly connected, there is a need to ensure that developments in ADR focus not only on creating alternative processes for dispute resolution, but also on the quality of outcomes achieved through the processes. While there have been many ADR innovations, access to justice is still problematic in Australia and this, among other things, reveals the need for further research to better understand the connection between ADR and access to justice.

To place this discussion in context, the current range of diverse ADR institutions and processes in Australia are detailed and, in order to examine the impact of ADR developments on access to justice, relevant reports, data and research are detailed. The paper concludes by canvassing the need to have access to justice as on overarching objective of ADR processes. The first section examines the scope of ADR in Australia and the connection between ADR and access to justice.

2 ADR in Australia and access to justice

ADR refers to both institutions and processes. In Australia, the following definition of ADR is often referred to:

‘[A]n umbrella term for processes, other than judicial determination, in which an impartial person assists those in a dispute to resolve the issues between them. ADR is commonly used as an abbreviation for alternative dispute resolution, but can also be used to mean assisted or appropriate dispute resolution.’ (National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council (NADRAC), 2003, p. 4)

However, ADR can also describe organisations or fora that provide dispute-resolution services that are outside or coexisting with formal court processes.

An ADR process refers to a series of actions/interventions/steps taken by either the disputing parties or a third party to assist parties to clarify issues in a dispute or to arrive at a settlement or resolution of a dispute (Mohr, Reference Mohr1982).Footnote 2 Boulle and Field provide a matrix of dispute-resolution processes, identifying seven categories, including two with no third-party involvement: self-help and processes without impartial intervention (Reference Boulle and Field2017, p. 50). The other categories identified include: facilitative, advisory, determinative, transformative and blended processes (NADRAC, 2003, p. 25). According to the NADRAC, mediation and facilitation fall within the facilitative category; adjudication and arbitration are determinative processes; and expert/case appraisal and early neutral evaluation are advisory processes (2003).

The main processes of ADR include negotiation, early neutral evaluation, mediation, conciliation, expert appraisal and arbitration. Boulle and Field (Reference Boulle and Field2017) also differentiate processes based on their focus: prevention, interests, rights and power. Within each process, differences exist. For example, mediation is further categorised into evaluative, facilitative and transformative. Additionally, there is often a fluidity or overlap between different processes, and within each process; for example, fluidity exists when identifying hybrid processes such as ‘arb-med’ and ‘med-arb’. The differentiation between processes relates to issues around formality, the role of third parties, process elements, the level of control held by parties, whether there is a statutory basis or relevant industry scheme and process objectives. Other considerations include the underlying values of processes, such as self-determination and neutrality of third parties and others (Boulle and Field, Reference Boulle and Field2017, pp. 33–79; Sourdin, Reference Sourdin2016, pp. 4–7; Akin Ojelabi and Noone, Reference Akin Ojelabi and Noone2017).

Categorisation of ADR processes has implications for access to justice. These relate to, among other things, the level of control a party has over the process and outcome (Akin Ojelabi, Reference Akin Ojelabi2019b). In some processes, parties who are better resourced, repeat players or more articulate may have greater control, while other processes may provide better access to justice due to low costs, timely resolution and support from third parties. Determinative processes remove decision-making control from parties and, in some cases, the procedure for decision-making is also determined by a third party based on applicable procedural rules. Where rules are rigid, and a party is not experienced in resolving disputes or is without resources, barriers to access to justice may be present (Akin Ojelabi, Reference Akin Ojelabi2019a).

Advisory processes are usually not determinative. The final outcome may be influenced by consideration of parties’ circumstances and the effect of any outcome on parties’ relationships. The outcome is usually based on negotiation between the parties upon receiving the third party's advice. Decision-making control is left to the parties, albeit influenced by the third party's advice.

Finally, facilitative processes are those that require the third party to remain neutral or impartial with no input into the content and outcome of the dispute. The third party is expected to use special skills to facilitate the discussion between parties that is particularly about needs and interests rather than positions. Facilitative processes may be used to support parties to reach an agreement prior to any dispute arising and achieve a preventative goal. Decision-making in facilitative processes is usually within the parties’ control. Like other categories, the extent to which access to justice may be enhanced by these processes depends on the nature of the dispute, characteristics of the parties and the type and quality of the process. In addition, limited resources available to parties to support effective participation may reduce barriers to access to justice.

In Australia, processes exist across the various categories. Before proceeding to explore the connection between ADR and access to justice, however, it is necessary to clarify the meaning of ‘access to justice’ as discussed in this paper.

3 Access to justice

In the early 1970s, in Australia and other parts of the world, concern to improve access to justice came from a realisation by many in the legal arena that the liberal claim of a justice system that ensured ‘equality before the law’ was a mere formal right, with little substance and practical effect (Sackville, Reference Sackville1975). There was a recognition that many people did not have the resources (including legal representation) to access the formal justice system and consequently significant inequality before the law existed. Additionally, there were no appropriate fora or remedies for many disputes and claims to be resolved (Cappelletti and Garth, Reference Cappelletti, Garth, Cappelletti and Garth1978; Cappelletti, Reference Cappelletti1993; Woolf, Reference Woolf1996; Parker, Reference Parker2000).Footnote 3 Increasingly, there was a growing recognition that justice is a complex phenomenon, and consequently access to justice cannot be confined to accessing courts or tribunals. Justice is multi-faceted: ‘Ultimately, access to justice is not just a matter of bringing cases to a font of official justice, but of enhancing the justice quality of the relations and transactions in which people are engaged’ (Galanter, Reference Galanter and Cappelletti1981, pp. 161–162).

Adopting this perspective on access to justice involves considering how people navigate and are treated in the many transactions (with legal consequences) that comprise everyday life. It is in these encounters that ‘equality [or not] before the law’ is experienced by most people. This perspective was adopted by the Australian Federal Attorney General's Department in 2009:

‘Access to justice is not only about accessing institutions to enforce rights or resolve disputes but also about having the means to improve ‘everyday justice’; the justice quality of people's social, civic and economic relations … giving people choice and providing the appropriate forum for each dispute, but also facilitating a culture in which fewer disputes need to be resolved. Claims of justice are dealt with as quickly and simply as possible – whether that is personally (everyday justice), informally (such as ADR, internal review) or formally (through courts, industry dispute resolution, or tribunals).’ (p. 4)

Experiencing access to justice in everyday life goes beyond access to available institutions for the resolution of disputes. It is about the elements that make up everyday life, in transactions that are concluded, encounters with others, governmental and other institutions. Achieving everyday justice suggests there are certain norms that attend to interactions in different arenas and whether, ultimately, those encounters improve participants’ well-being or detract from it. As noted by the Productivity Commission (2014, pp. 85–86) and the Law and Justice Foundation (2012, pp. 180–182), unmet legal needs as a result of lack of access to justice can have significant negative impacts on individual well-being.

In 2014, the Productivity Commission canvassed a range of difficulties with defining access to justice but opted for a simplified approach. For the purposes of its inquiry:

‘[I]mproving “access to justice” in the context of civil dispute resolution means making it easier for people to resolve their disputes according to law by improving the capacity and capability of the justice system, and overcoming barriers to accessing the system. The “system” includes formal and informal institutions and processes, as well as information and advice.’ (Productivity Commission, 2014, p. 77)

In adopting this definition, the Productivity Commission concurrently narrowed the concept of access to justice to resolution of disputes according to law, whilst broadening the civil justice system to include formal and informal institutions, processes, advice and information. Arguably, a reference to ‘resolution according to law’ incorporates objective standards by which to assess access to justice, including the fairness of the terms of settlement. This means that access to justice, as defined by the Productivity Commission, is not limited to entering the system (formal or informal), but also includes the quality of outcomes: the point made here is that access to justice is not only about access, but also about justice, while also acknowledging that justice can be conceived in many different ways. As Cappelletti and Garth have noted, access to justice is about equal access to state systems for vindicating rights and resolving disputes, and also ensuring that outcomes achieved are just, with reference to both the immediate context, including the nature of the dispute and characteristics of the parties, and the broader social context (Cappelletti and Garth, Reference Cappelletti, Garth, Cappelletti and Garth1978, pp. 6, 64, 68–69; Moorhead and Pleasence, Reference Moorhead, Pleasence, Moorhead and Pleasence2003, pp. 1–3).

The conception of justice that attends to access to justice can, however, be broad. While it could be broadly referred to as social justice, it could also be compartmentalised into different conceptions of justice, including: procedural, distributive, relational and informational (Condliffe, Reference Condliffe2012, Chapter 5; Condliffe and Zeleznikow, Reference Condliffe and Zeleznikow2014). Different interactions lead to the need for different forms of justice and what is perceived as justice, or what is needed to address injustice, will differ from one arena of interaction to the other. As such, various justice conceptions are relevant in dispute resolution. Arguably, though, procedural and distributive justice are broad categories of justice that can accommodate most of the other conceptions that feature more prominently in the resolution of disputes and every interaction. Justice of the process is intertwined and has consequences on the justice of outcomes—that is, the result of any dispute-resolution procedure.

Whilst acknowledging the complexity in defining justice and generally agreeing with a broad definition of access to justice, in this paper, the focus is on the formal and informal processes available to help people resolve their disputes. In this context, access to justice is not only about gaining entry or having the opportunity to present one's claim, defend a right or to participate in dispute resolution; it also includes aspects of the process and the outcomes that result from such participation. To examine the connection between ADR and access to justice, it is helpful to understand the factors that limit access to justice.

3.1 Factors limiting access to justice

Whether access to justice is improved with ADR processes depends in part on how those who are disadvantaged fare in those processes (Noone and Akin Ojelabi, Reference Noone and Akin2014). It is argued that disadvantage is multidimensional and depends on space and time, rather than it being about specific individuals. The position in time of an individual and the space that a person occupies may make them more vulnerable to disadvantage (Brennan et al., Reference Brennan2017, pp. 639–640). Disadvantage is recognised as having many aspects and an individual can suffer from multiple forms of disadvantage (Law Council of Australia, 2018). It can result from age, poverty, discrimination, disability, poor health, geographic isolation, poor language skills, illiteracy, cognitive impairment, homelessness and a range of other factors resulting in a lack of/limited capacity (Law and Justice Foundation of New South Wales, 2012, pp. 5–6, 16).

Furthermore, numerous government reports and studies have identified that discrimination is endemic in parts of the Australian justice system: those who are indigenous, poor, disabled and live in rural and regional areas fare worse in accessing justice than others (Law Council of Australia, 2018). Empirical research conducted in 2008 revealed that people with a disability and single parents are twice as likely to experience legal problems; unemployed and people living in disadvantaged housing are also vulnerable; and indigenous people are most likely to experience multiple legal problems (Law and Justice Foundation of New South Wales, 2012). Over 3 million (13.2 per cent) Australians are living below the poverty line and one in eight adults lives in poverty (ACOSS, 2018). The group of people experiencing poverty the most are those relying on government income support.

This information is relevant in thinking about access and justice quality as people with multiple disadvantages may lack the capacity to meet a fundamental aspect of most prominent ADR processes, self-determination or party autonomy. Capacity can affect participation, informed decision-making, understanding of the process and the consequences of possible solutions to the dispute (Noone and Akin Ojelabi, Reference Noone and Akin2014). As such, the extent to which ADR processes may improve access to justice is dependent, as noted above, on the nature of the dispute, the characteristics of the parties and the extent to which resources are available to support the parties’ effective participation in the process. The next section focuses on ADR fora in Australia and implications for access to justice.

4 Australian ADR: diverse institutions, processes and access to justice

In Australia, dispute resolution has ancient antecedents in the indigenous community, but these approaches were not recognised by the colonial invaders (Boulle and Field, Reference Boulle and Field2017, pp. 84–88). Although the colonisers inherited and adopted the English common-law system with a focus on resolving disputes through formal court systems, as will be seen below, Australia was an early adopter of ADR processes.

In discussing the connection between ADR and access to justice in Australia, the context within which ADR processes were enshrined in the Australian Constitution for the resolution of industrial disputes is relevant. After a series of major industrial strikes in the 1890s that led to significant social disharmony, there was a growing community belief that, if employers and unions could not resolve their disputes, they should be required in the public interest to submit their competing claims to an independent third party for arbitration. Subsequently, industrial tribunals were established (Australian Industrial Relations Committee, 2006, p. 2). At the time of Federation in 1901,Footnote 4 the role of conciliation and arbitration in industrial disputes was enshrined in the Australian Constitution (s. 51(xxxv)) and later in the passing of the Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904 (Cth).Footnote 5 Within this context, the following factors are salient: the necessity for a change from a culture of violent, aggressive disputing and dispute resolution to a culture of collaborative, peaceful disputing and dispute resolution; the necessity for a process that could address systemic issues/public-interest issues but was also conciliatory and collaborative. The government at the time had an interest in stopping the violent and intractable conflict due to the economic implications of the then labour disputes, hence the reference to peace, order and good government in the Constitution (s. 51, Australian Constitution). While conciliatory, the process had to be compulsory and confer power/authority on the third party to bring the dispute to an end.

This legacy of seeking an alternative way of resolving disputes was reinvigorated in Australia in the 1960s and 1970s. Worldwide, there was a growing awareness in Western industrialised societies that, for many people in dispute, there was no viable or accessible dispute-resolution forum (Sander, Reference Sander1976). Two specific influences in the Australian context were the community justice movement and the call to civil justice reform from various stakeholders (including users of legal services, the legal profession, the judiciary and the government) (Astor and Chinkin, Reference Astor and Chinkin2002, p. 5; Spencer et al., Reference Spencer2019, pp. 4–21; Sourdin, Reference Sourdin2016, Chapter 1; Boulle and Field, Reference Boulle and Field2017, p. 91).Footnote 6

ADR in Australia has grown exponentially and undergone significant transformations since the 1970s. Multiple reviews have recommended increased use of ADR processes.Footnote 7 In 1994, the continued development of ADR to address access-to-justice problems was recommended by the Access to Justice Advisory Committee. ADR programmes were viewed as one solution to improving access to justice in the civil justice and family-law systems. At the time, the committee identified the advantages of ADR to include the provision of a broader range of remedies and the availability of cheaper and less formal processes (Access to Justice Advisory Committee, 1994, pp. 279, 300).

The variety and form of ADR institutions have grown to address disputes in many areas, including: family law, consumer and credit finance matters, tenancy, small business and consumer complaints. Concurrently, there has developed a diverse range of ADR fora in Australia: voluntary, compulsory industry-based and/or legislation-based, court-connected ADR utilising a variety of ADR processes. As King et al. noted, ADR has been ‘enthusiastically championed, criticised, modified [and] regulated’ (Reference King2014, p. 95).

Nonetheless, the origins of the modern manifestation of ADR processes in Australia are firmly grounded in a concern to improve access to justice, including the quality of justice for all in the community (Astor and Chinkin, Reference Astor and Chinkin2002, p. 3). The establishment of ADR institutions such as ombudsmen services,Footnote 8 specialist tribunalsFootnote 9 and community and neighbourhood justice centres to provide fora to resolve disputes not adequately addressed by the formal court system was prompted by this concern to improve access to justice (Law Reform Committee, 2009, p. 19; Boulle and Field, Reference Boulle and Field2017, pp. 92–94). These new organisations and fora utilised and developed ADR processes like mediation, conciliation and arbitration and various hybrids that have been subsequently incorporated into the formal court and tribunal systems, and legislated for use in relation to particular types of disputes including disability, small business, health and accident compensation (Akin Ojelabi and Noone, Reference Akin Ojelabi and Noone2017). ADR processes in the civil justice system, community and legislation-based are briefly discussed below, further highlighting the connection with access to justice.

4.1 ADR within the civil justice system

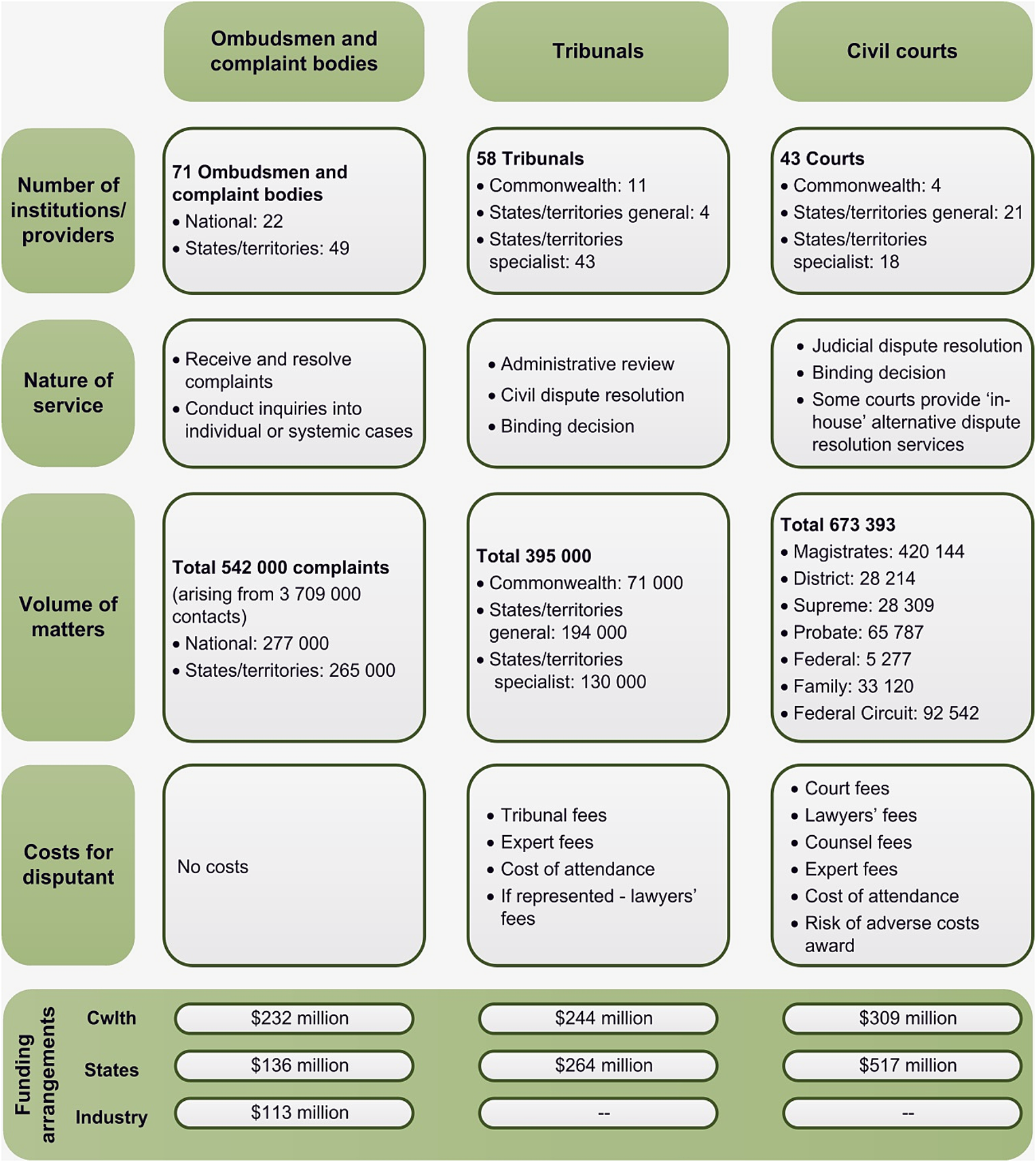

ADR processes have become an accepted part of the formal civil justice system in Australia.Footnote 10 Problems identified in the operation of the civil justice system including high costs of lawyers and use of courts, delay, uncertainty, fragmentation, the adversarial nature of litigation and a limited range of available outcomes are seen as alleviable through the use of ADR processes (King et al., Reference King2009, pp. 10–11; Akin Ojelabi, Reference Akin Ojelabi2019a). While ADR is not a panacea for access-to-justice problems encountered in the civil justice system, processes have been adopted and institutionalised within the system. Courts and tribunals now regularly require parties to use ADR processes either as a condition before accessing courts or as a result of a court order. Court-annexed or court-connected dispute-resolution schemes form a significant part of the Australian dispute-resolution landscape (Sourdin, Reference Sourdin2016, Chapter 8; Spencer et al., Reference Spencer2019, pp. 176–219). These processes may be compulsory or voluntary. In 2014, the Productivity Commission commented that the ‘federal, state and territory courts, statutory tribunals, government and industry ombudsmen and complaint bodies, and organisations and individuals offering alternative dispute-resolution services all form part of the civil justice mix’ as indicated in Figure 1 (Productivity Commission, 2014, p. 5).Footnote 11

Figure 1. The three major dispute-resolution mechanisms

The exponential growth of ADR within the civil justice system can be linked to the request made by the federal Attorney General to the NADRAC in 2008 to report on how to ‘encourage parties to civil proceedings to make greater use of ADR to overcome court and tribunal barriers to justice’ (NADRAC, 2009, p. ix). The NADRAC delivered a report that informed the Civil Dispute Resolution Act 2011 (Cth) (‘Civil Dispute Resolution Act’). The object of this act is to ensure that people take genuine steps to resolve disputes before instituting civil proceedings (NADRAC, 2009, pp. 142–149). Within the federal-court jurisdiction, ADR processes are encouraged with pre-action protocols that require parties to have taken genuine steps towards the resolution of disputes before commencing proceedings (Civil Dispute Resolution Act). Similarly, the purpose of the Civil Procedure Act 2010 (Vic) was to ‘facilitate the just, efficient, timely and cost-effective resolution of the real issues in dispute’ (s. 7(1)). ADR processes are also widely utilised by courts and tribunals within litigation proceedings.

While the use of ADR processes within the court system has grown exponentially, issues have been raised about the quality of those processes and the extent to which they enhance access to justice (Spencer et al., Reference Spencer2019, pp. 179–182; Noone and Akin Ojelabi, Reference Noone and Akin2014; Akin Ojelabi, Reference Akin Ojelabi2019a). Some of the issues identified in relation to access to justice relate to how mediators, for example, address power imbalances between the parties and ensure that parties participate effectively in the process. In addition, the extent to which court-connected mediation is adversarial due to the involvement of lawyers has been raised (Waye, Reference Waye2016; Rundle, Reference Rundle2015).

Regardless of the issues raised, the institutionalisation of ADR is based on the need to improve access to justice. An example is the use of judicial mediation in the Victorian Supreme Court in Testator Family Maintenance (TFM) proceedings. The court's Annual Report states that the use of judicial mediation saved 1,302 trial days in 2016–2017 and lowered costs for parties. The mediations were said to be ‘critical in providing access to justice’. The report further stated that ‘In TFM List mediations, the restorative justice approach, together with a no-fee principle ensure both access and reassurance and as such, represent a major benefit to the community’ (Supreme Court of Victoria, 2016/17, p. 46). Reductions in time and costs were also stated to be benefits of litigation-related mediation by court registrars (Supreme Court of Victoria, 2016/17, p. 47).Footnote 12

In addition to the use of ADR by courts and tribunals, federal-government agencies are required to take genuine steps to resolve disputes early. When legal proceedings are unavoidable, they are required to ‘model’ appropriate behaviour (Productivity Commission, 2014, pp. 295–296).Footnote 13 The 2014 Productivity Commission's Report on Access to Justice Arrangements endorsed further development of ADR processes within the civil justice system:

‘Court and tribunal processes should continue to be reformed to facilitate the use of alternative dispute resolution in all appropriate cases in a way that seeks to encourage a match between the dispute and the form of alternative dispute resolution best suited to the needs of that dispute. These reforms should draw from evidence based evaluations, where possible.’ (p. 294)

The above comment from the Productivity Commission indicates the need to ensure that ADR processes deliver in improving access to justice for parties who use them. While the processes now form part of the civil justice system, continued monitoring in relation to improving access to justice is required.

As illustrated above, the use of ADR within the civil justice system was enhanced through legislation. Additional aspects of legislation prescribing ADR processes are examined in the next section.

4.2 Legislation-based ADR and access to justice

In Australia, legislation has been significant in promoting the use of ADR processes to improve access to justice. It has been used to prescribe dispute-resolution procedures and processes in relation to specific types of disputes and to strengthen and regulate ADR (NADRAC, 2006, p. 2). The types of disputes subject to legislation include those involving the public interest, where there is significant power imbalance between parties, where the relationship between parties matter beyond resolution of the dispute and where significant costs will be incurred by using the adversarial court process.

One of the goals of legislated ADR is often to ensure a reduction in the level of stress and unpleasantness encountered by disputing parties, thus improving their experiences of access to justice. In family-law cases, for example, parties seeking parenting orders are required to have attended family dispute resolution (a form of mediation) before commencing proceedings (Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Act 2006 (Cth) (‘Family Law Amendment Act’)).Footnote 14 Legislation exists in several areas in relation to the use of ADR to resolve disputes.

Another example is a new law passed by the Victorian government in 2018, aimed at making it easier for matters filed in the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) to be resolved through compulsory conference and for agreements reached to be made enforceable.Footnote 15 The Explanatory Memorandum states the amended section 83(1) VCAT Act 1998 (Vic) ‘is intended to enable more widespread use of compulsory conferences across the Tribunal and, in turn, promote the early resolution of disputes, by permitting a wider pool of persons (such as mediators) to conduct compulsory conferences’.

Compulsory conferences provide the opportunity for parties to discuss options for resolution in private with the assistance of a third party. Where parties are unable to reach a resolution at the compulsory conference, key issues for determination at the hearing could be identified and procedural directions for the final hearing made. Under the new section 93(4) of the VCAT Act 1998 (Vic), agreements reached at the compulsory conferences may be formalised by the tribunal. This provision addresses any uncertainty that may arise in relation to the enforcement of settlement agreements, thus strengthening access to justice.

Legislated ADR processes tend to incorporate principles and goals that promote just outcomes while also imposing obligations on practitioners to ensure those goals and principles are applied. Examples of legislated ADR fora include disputes involving providers of mental health services and clients, those living with disabilities and service providers,Footnote 16 small businesses,Footnote 17 farmers and financial institutions,Footnote 18 human rights disputesFootnote 19 and accident-compensation disputes.Footnote 20 These disputes usually comprise a number of issues including power imbalances arising from lack of information, inability to participate in dispute resolution without sufficient support, costs, the need for timely resolution and significant public-interest matters. These types of legislated ADR interventions are aimed at improving access to justice; however, realising parliament's intentions requires continued monitoring to ensure that the processes do not result in further disadvantage to already disadvantaged parties (Akin Ojelabi and Noone, Reference Akin Ojelabi and Noone2017).

A recent investigation conducted by the Victorian Ombudsman (Reference Victorian2019) highlights the need for ongoing evaluation of how the use of ADR processes enhances or fails to support access to justice. Conciliation of disputes relating to injuries suffered at work under the workers’ compensation scheme,Footnote 21 and in particular those involving complex injuries or claims, was found to lead to further delays and costs. Agents representing employers attended conciliation with no intention of resolving the dispute in the hope that the affected worker would then abandon the claim due to the enormous cost of proceeding to litigation. The agents were found to maintain ‘unreasonable decisions during conciliation, that they knew would not hold up in court’ and were ‘unwilling to resolve disputes’ regardless of provisions of the Workplace Injury Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 2013 (Vic) (WIRC Act), which requires agents to withdraw unreasonable decisions that would not have the prospect of success at court and to take all reasonable steps to resolve the dispute. The report notes:

‘Many claimants outside of the force who are involved in psychological injury claims will accept less compensation or abandon their claim to avoid … stressors. The Association believes that the process of rejecting these cases is in the hope that members run out of leave, benefits, or money, so that they give-up, resign, or return to work and forget about the claim.’ (Victorian Ombudsman, Reference Victorian2019, p. 120)

While the issue does not relate to the quality of the conciliation process, it relates to the limited powers of conciliators. Conciliators in this scheme are unable to give directions to overturn an agent's decision regarding a claim where the agent can show an arguable case (ss. 293–294, WIRC Act). The effect of this is that 70 per cent of disputed claims that proceeded to court in 2017/18 were ‘varied or overturned’ (p. 9, paras 26–27). This, among other things, led the ombudsman to conclude that: ‘The system is failing to deliver just outcomes to too many people; agents continue to make unreasonable decisions, the dispute process is time consuming, stressful and costly, and Worksafe is too often unwilling or unable to deal’ (Victorian Ombudsman, Reference Victorian2019, p. 5).

While this is one example of impropriety in the use of an ADR process, research shows that repeat players may have an advantage in an ADR process (Galanter, Reference Galanter1974; Riskin and Welsh, Reference Riskin and Welsh2008; Erez-Navot, Reference Erez-Navot2015) and may not participate in the process in good faith. This points to the need to ensure that the process, type of dispute and characteristics of parties are considered in designing or selecting a dispute-resolution process with a goal of increasing access to justice.

A related example involves mandated family dispute-resolution processes that may also result in unfair outcomes if there is a power imbalance between the parties as well as a history of violence. In recognition of the potential for injustice to occur, much work has been done to design processes that are suitable for these types of matters.Footnote 22 The next section considers ADR within the community.

4.3 Dispute-resolution organisations and access to justice

In addition to the dispute-resolution fora listed in Figure 1, community and neighbourhood justice centres exist in all states and territories in Australia offering dispute-resolution services (primarily mediation), such as the Dispute Settlement Centre Victoria (Dispute Settlement Centre of Victoria, 2017), community justice centres in New South Wales (NSW Government, 2018) and Mediation Australia. These organisations assist in multiple disputes, including neighbourhood, family, workplace, committee and interpersonal (Boulle and Field, Reference Boulle and Field2017, p. 93).

In Australia, there are also a range of organisations offering dispute-resolution services specifically in family disputes (Relationships Australia, 2017; Better Place Australia, 2018). In 2006, sixty-five family relationship centres were established to support families in resolving post-separation disputes, including parenting agreements (Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Act 2006 (Cth)). More broadly, there are various areas of public ADR in Australia, such as statutory agencies’ dispute resolution, industry dispute-resolution schemes, public policy dispute resolution, commercial dispute resolution and internal organisation dispute resolution (Productivity Commission, 2014, p. 299; NADRAC, 2001, pp. 18–23).

Community justice centres were first set up by the NSW government in the 1980s with the hope that they would provide disputing parties with the opportunity to resolve their disputes outside of courts and without the need for legal representation. Community justice centres are also resourced to provide culturally appropriate services and services that meet the specific needs of people with disabilities (Williams, Reference Williams2005).

The advantages of resolving neighbourhood disputes through mediation are numerous, including costs savings, improved communication and eliminating stress associated with adversarial proceedings. Where neighbourhood disputes are not resolved in a timely manner, they may escalate and become more complex, and some might eventually be the basis of criminal proceedings (Mackay and Moody, Reference Mackay and Moody1996; Danzig and Lowy, Reference Danzig and Lowy1975)Footnote 23 as these types of disputes range from private nuisance issues to a range of ‘anti-social and criminal behaviour’, ‘featuring criminal activities, such as damage to property, physical abuse, threats and intimidation’ (Cheshire and Fitzgerald, Reference Cheshire and Fitzgerald2015, p. 101). Escalation of neighbourhood disputes makes the issues more complex and possibly with reduced access to justice.

ADR organisations involved in community dispute resolution provide quick and cheap access to justice for the resolution of neighbourhood disputes that may relate to fencing, noise, animals, boundaries and so on. The opportunity to resolve these disputes through non-adversarial ADR processes is thus invaluable, promoting community well-being.

4.4 Online dispute resolution and access to justice

Innovations in technology and a wide range of Internet-based ADR services also present many opportunities to enhance ADR and access to justice for those currently denied it (Susskind, Reference Susskind2013; Lodder and Zeleznikow, Reference Lodder and Zeleznikow2005; Cashman and Ginnivan, Reference Cashman and Ginnivan2019). The use of technology for the resolution of disputes is being developed in many jurisdictions including British Columbia, Canada and the UK.Footnote 24 There are many forms of online dispute resolution. More broadly, technology-assisted dispute resolution has been categorised into three types: supportive (e.g. online legal services), disruptive (e.g. artificial intelligence dispute resolution) and replacement (e.g. online mediation) technologies (Sourdin and Shanks, Reference Sourdin and Shanks2015; Susskind, Reference Susskind2013).

There are many examples of technology-assisted dispute resolution in Australia. Technology has been developed to support the resolution of family-law disputes (Bellucci and Zeleznikow, Reference Bellucci and Zeleznikow2006; Zeleznikow, Reference Zeleznikow2011). Australian legal-aid commissions are developing an online dispute-resolution process for divorcing couples where the technology can provide users with templates highlighting parenting agreements that have worked for other couples. Artificial intelligence will assess family-law-court decisions to show couples how judges generally treat disputes that are similar to theirs (National Legal Aid, 2017; Stranieri et al., Reference Stranieri1999). Furthermore, many courts and tribunals are now trialling technology-assisted forms of dispute resolution incorporating ADR processes. The VCAT, following recommendations from the Access to Justice Review (Victoria Government, 2016), explored the use of digital technology to improve access to justice. Online dispute resolution (ODR) was piloted in the 2018/19 financial year for disputes involving small businesses (VCAT, 2019, p. 16; Tan, Reference Tan2019, pp. 122–127), with a similar pilot undertaken by the NSW Civil and Administrative Tribunal (NCAT) in 2014 (Tan, Reference Tan2019, pp. 127–128).

While technology-enabled/assisted dispute resolution can improve access to justice and can be a very convenient and effective process choice for many disputants, it requires effective and sufficient safeguards (ADRAC, 2016b; Ebner and Zeleznikow, Reference Ebner and Zeleznikow2016; Sourdin et al., Reference Sourdin2019). For example, although there is significant potential for improving access to justice through the use of ODR and digital technology, it must be remembered that those most in need of assistance are often also the most disadvantaged. Almost 2.6 million Australians (10 per cent) do not use the Internet and nearly 1.3 million households are not connected (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2018). Given that certain groups in our community suffer more from lack of access to justice than others, it is also critical to ensure that the digital revolution does not impact them more than others.

There can be no doubt that there has been an increase in ADR processes being accessed by the community. What is much less certain is who accesses these processes, what happens when they do, what ADR processes are used, what are the users’ experience of processes and what are the outcomes? In other words, what is the nature of the ‘justice’ being accessed? While these are ‘new’ developments, continuing evaluation is required to ensure that processes improve access to justice and do not create new barriers to accessing justice for some groups within society. In addition, attention must be paid to ensuring that the type and nature of dispute and characteristics of parties as well as available resources to support effective participation continue to be taken into consideration in developing technologies for the resolution of disputes. The next section discusses factors that may enable continuing the improvement in access to justice through ADR.

5 Enhancing access to justice through ADR: some considerations

Since the 1970s, the exponential growth of Australian ADR institutions and organisations (both public and private) has meant that there are now significantly more options for people seeking to resolve disputes. As indicated above, recent reports have endorsed the connection between accessible ADR processes and fora and access to justice. The Australian Dispute Resolution Advisory Council (ADRAC) also supports the proposition that ADR is part of ‘access to justice’ and that the availability of effective ADR enhances access to justice, including for those most in need of it (ADRAC, 2016a). The number and range of institutions (including tribunals, ombudsmen and dispute-settlement centres) are an indication of the increased use of ADR (Productivity Commission 2014, Chapters 8–10). In its submission to the Productivity Commission, the Consumer Action Law Centre, a community legal centre noted: ‘Without industry ombudsman schemes, hundreds of thousands of people would have been left with no avenue for redress other than courts, or more likely, because of cost and other access barriers, would have been left with nowhere to turn’ (Consumer Action Law Centre, 2012, p. 315).

The benefits of ADR to individuals, government and society can be numerous. For individuals, the opportunity for self-determination in a non-adversarial environment is most salient and, for both individuals and government, the costs usually associated with dispute resolution are significantly reduced when non-adversarial processes are used (Productivity Commission, 2014, pp. 37–38). Other alleged benefits of ADR processes include time savings and case-management benefits for courts. This is not to mention the preservation and improvement of party relationships.

The growth in the variety of ADR processes and institutions available is a gain for access to justice. Processes and disputes can be appropriately matched, based on the actual needs and requirements of parties and the dispute subject matter. This is ADR. ADR is a term that has been developed to accommodate the view that ADR is not merely an alternative to the courts, but acknowledges the fact that some types of disputes may be best resolved using particular processes: the nature of the dispute, the availability of resources, the parties’ characteristics and the quality of the process matter. As King et al. noted, it is about the ‘need to find the best forum, whether adjudicatory or informal, for the parties and the problem, given available resources’ (Reference King2014, p. 96).

This approach may also support parties to achieve the best justice outcomes for their disputes, including a greater range of possible resolutions. ADR organisations or institutions now develop a variety of ADR processes that promote the objectives of those organisations or institutions relating to the form of the dispute and the parties involved. Some processes protect particular interests and promote specific principles of justice (Akin Ojelabi and Noone, Reference Akin Ojelabi and Noone2017, p. 5).

Greater use of ADR in appropriate cases is generally supported, although:

‘The capacity of ADR to resolve more disputes relies on improving general knowledge about ADR, providing triage and advice services, ensuring legal professionals consider and suggest ADR as an option to clients, and supporting the delivery of culturally appropriate and accessible ADR.’ (Productivity Commission, 2014, p. 302)

Another factor that could support the continuing enhancement of access to justice through ADR is to ensure that ADR practitioners are competent and experienced. There is a need for ADR organisations to ‘continue to develop, implement and maintain standards that enable professionals to be independently accredited’ (Productivity Commission, 2014, p. 307). While accreditation standards exist in mediation (National Mediator Accreditation System, Accreditation and Practice Standards, 2015), there are no accreditation standards applicable to processes like conciliation and other hybrid processes. The ADRAC is currently engaged in a project on conciliation. The project aims to clarify the extent to which conciliation is used, practitioners’ understanding of what conciliation is and matters relating to standards (ADRAC, 2019).

While practice standards are desirable and will improve outcomes, having a set of practice standards or professional code of conduct for ADR processes is problematic, as practitioners come from a variety of professional backgrounds and some offer ADR services in private capacities. The variety of disciplinary backgrounds has implications for how justice is construed by ADR practitioners and for the purposes of process design (Douglas and Batagol, Reference Douglas and Batagol2014). For instance, many lawyers (both barristers and solicitors) train to be mediators and lawyers’ professional organisations (including professional associations in Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia, Queensland and NSW, and Bar Associations in Queensland, South Australia and Victoria) accredit lawyers to be mediators. The legal professional associations actively promote the benefits of engaging mediators with lawyers’ skills and some law firms promote a specific focus on providing dispute-resolution services, including: mediation, arbitration and facilitation (e.g. McFarlane Legal, 2018).

Practitioners with a legal background will most likely construe justice as justice derived from the application of legal principles, while practitioners with engineering, social work, psychology and business backgrounds will most likely construe justice differently. This undoubtedly has implications for parties, as interventions by practitioners may be informed by values or principles that relate to their professional background. This can lead to inconsistencies in approaches and outcomes that may be obtained through similar dispute-resolution processes (Noone and Akin Ojelabi, Reference Noone and Akin2014).

There is also the need to ensure that users of ADR processes have relevant information regarding the processes and their obligations/roles in the processes (Field and Crowe, Reference Field and Crowe2017). It is not unusual for mediation participants, for example, to request the mediator for some advice in generating options for settlement when the mediators have an obligation not to provide advice in facilitative mediation processes. Lack of awareness of process, own roles and third-party roles may reduce the effectiveness of processes in facilitating resolutions – and ultimately have an impact on perceptions of fairness. This raises both procedural and substantive justice issues (Productivity Commission, 2014, p. 303). The extent to which appropriate resources are available to the parties may also impact on the justice obtained through dispute-resolution processes. Some agencies are already increasing parties’ participation capacities – including a detailed intake processFootnote 25 – but more work is required.

Other areas of importance include meeting the needs of specific groups of people or individuals including, such as people living with disabilities, those from culturally diverse communities and those with less access to infrastructure, such as technology (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong2015a; Reference Armstrong2015b; Akin Ojelabi et al., Reference Akin Ojelabi2011; Akin Ojelabli, Reference Akin Ojelabi2015; Productivity Commission, 2014, pp. 307–308).

Furthermore, the current varied and complex ADR landscape may create hurdles for disadvantaged parties and further hinder access to justice for those most vulnerable (Akin Ojelabi, Reference Akin Ojelabi2011a; Reference Akin Ojelabi2011b). Specific issues raised in relation to access to justice and mediation include the loss of public-interest law cases due to the mandated and private nature of ADR, inherent power imbalances, the informal nature of mediation and inequities (Noone, Reference Noone2011). Also, the mandatory nature of some ADR regimes can mean that inappropriate matters are referred to ADR, which then results in inequitable settlements or no settlement. This further increases the costs of dispute resolution and stresses for parties.

All of these issues have implications for the justice accessed in ADR. The Victorian Access to Justice Review recommended that: ‘All organisations which use or provide alternative dispute resolution processes should ensure the processes they provide are of a high-quality, with respect to both the fairness of the process and the fairness of the outcome’ (Victoria Government, 2016, p. 194).

ADR processes may be providing access to justice in relation to creating an entry into a dispute-resolution process, but the question of outcome justice is for each scheme or process to consider in light of the type and nature of disputes and parties for whom access is provided. As noted above, access to a forum is no guarantee for a socially just outcome. What constitutes a just or fair outcome is complex and may vary between parties, ADR practitioners and managers of ADR organisations.

Outcomes are usually recorded by ADR organisations in terms of settlement rates. As the Productivity Commission noted, often between 70 and 80 per cent of matters settle, although, without further data, it is not possible to assess the justice quality of these outcomes (2014, p. 288). Significant research in relation to the use of mediation in the Supreme and County Courts of Victoria was conducted in 2010. The research report discussed the issue of justice and measured procedural justice. It found that most disputants were satisfied with outcomes obtained and ratings for procedural fairness was high, but 73.7 per cent of defendants and 56.2 per cent of plaintiffs who were surveyed felt pressured to settle (Sourdin, Reference Sourdin2010, p. 112). Another survey showed that

‘people who finalised their disputes by ADR (through, for example, formal mediation, conciliation, or dispute resolution sessions) were “very satisfied” in 34 per cent of disputes, relative to 44 per cent being “very satisfied” in disputes finalised in courts and tribunals. However, there was a similar proportion between the two methods (75 and 72 per cent, respectively), that expressed satisfaction with the outcome of the dispute (stating that they were “very” or “slightly” satisfied).’ (Productivity Commission, 2014, p. 288)

Although these data are a small indication of parties’ satisfaction, they illustrate how little we know about ADR outcomes. In a research project that sought the views of mediators about justice, amongst those participants that agreed mediation should be concerned with justice, views diverged as to whether the focus should be on procedural or substantive justice. While some were of the view that the focus should be on procedural justice alone, others emphasised the relationship between procedural and substantive justice. A third group were of the view that mediation should be focused on substantive justice, particularly when it is a process that arises from the justice system (Noone and Akin Ojelabi, Reference Noone and Akin2014). It was clear from those interviews that the justice quality of ADR depends on several factors, including: the robustness of the intake processes; the skills, knowledge and experience of ADR practitioners; and the quality of support and information available to parties in ADR processes (Noone and Akin Ojelabi, Reference Noone and Akin2014).

Additionally, there is often an inherent tension between the obligations arising from the legislative objectives and the common understanding of mediation values (Akin Ojelabi and Noone, Reference Akin Ojelabi and Noone2017). When ADR practitioners have specific responsibilities under legislation to ensure substantive justice, like fair treatment and reasonable and fair outcomes, and to address systemic issues, discrimination and vilification, their obligations conflict with the principle that mediation practitioners should be third-party neutrals (concerned with procedural justice but not substantive justice) (Akin Ojelabi and Noone, Reference Akin Ojelabi and Noone2017). As such, the objectives of any ADR process are significant in the extent to which justice can be pursued. It is therefore important to consider at the onset what the objectives of any ADR scheme are, and to ensure that processes are designed and relevant resources are available to support parties to realise those objectives.

The next section considers the question of objectives more closely while also proposing that improving access to justice should be an overarching objective of all ADR processes and services. Access to justice should be an active principle in designing and implementing ADR processes, bearing in mind that access to justice is also about just outcomes. The importance of an overarching objective is discussed below.

6 An overarching objective for ADR processes

Given the need to ensure that processes are appropriate to type and nature of dispute while taking characteristics of parties and resources available to them into consideration, it is important to focus on access to justice as an active principle guiding the design and implementation of ADR processes. The objectives of ADR processes determine the justice focus and what type of justice is achieved. Where process designers consider issues of justice in formulating objectives, these become embedded in those objectives. The extent to which ADR processes deliver justice, and what type of justice it delivers, is therefore impacted by process objectives (Akin Ojelabi and Noone, Reference Akin Ojelabi and Noone2017).

The NADRAC in 2009 expressed the view that ADR processes should be fair, result in acceptable and lasting outcomes, and use resources efficiently. To summarise, the objectives of ADR processes, according to the NADRAC, are: efficiency, effectiveness, procedural justice and substantive justice. The outcomes, the NADRAC opined, should also be consistent ‘with public and party (including third party) interests’. Nevertheless, outcomes achievable will depend on multiple factors (NADRAC, 2009, p. 80). According to the NADRAC:

‘The nature of “acceptable” or “appropriate” outcomes … varies across different ADR processes and contexts. For example, particular responsibilities apply to family and child mediators with respect to protecting the interests of children, and ADR practitioners in statutory organisations often have responsibilities to support the objectives of relevant legislation. In NADRAC's view appropriate outcomes would be consistent in broad terms with both party (including third party) interests and public interests, although the balance of these interests may need to be determined according to the context and matter under consideration.’ (2001, p. 14)

In Australia, ADR process objectives range from general to specific – from legislative purposes, which become mandatory requirements for practitioners, to those that are merely exhortatory with no binding implications (Akin Ojelabi and Noone, Reference Akin Ojelabi and Noone2017). The objectives could be set at a higher level, such as the objectives of a justice system. In this sense, the dispute-resolution processes would be designed to support the goals of the justice system. This approach was noted by Tyler (Reference Tyler1989) in relation to the evaluation of dispute-resolution processes; rather than beginning with existing procedure, such an effort would ask what goals the justice system seeks to achieve and then examine the ability of different procedures to achieve them.

An example of such an overarching objective was conceived by Genn writing from a UK perspective. She argued that the civil justice system is a public good with four main goals: to contribute to socio-economic well-being by enforcing rights and other protections under the law; promoting social order and peaceful resolution of disputes; communicating and reinforcing societal values and norms; and, finally, supporting economic activity. Based on these objectives, Genn concluded that the ADR movement may result in a loss of ‘the language of justice in relation to a very wide range of issues affecting the lives’ of citizens’ (Genn, Reference Genn2012, p. 417). A response to addressing some of the concerns raised by Genn about whether ADR is achieving the broad objectives of the civil justice system – or the justice system more broadly – could be a focus on access to justice, particularly for civil disputes (Akin Ojelabi, Reference Akin Ojelabi2016).

Legislative-based ADR processes tend to incorporate justice principles and goals while also imposing obligations on practitioners to ensure those goals and principles are applied. In research that explored ADR organisations governed by legislation (fourteen relevant acts),Footnote 26 most of the legislation had overarching purposes of ensuring that legislative objectives are promoted or given effect. As such, the ADR practitioners could not be entirely neutral (Akin Ojelabi and Noone, Reference Akin Ojelabi and Noone2017, p. 12). For example, under the Mental Health Act (s. 244(5)), a dispute-resolution officer must promote the well-being of consumers of mental health services and identify potential service improvement in the ADR process (Akin Ojelabi and Noone, Reference Akin Ojelabi and Noone2017, p. 14). These objectives have a significant impact on the extent to which practitioners promote the justice of outcomes.Footnote 27 In canvassing for a governance structure for ODR, Ebner and Zeleznikow (Reference Ebner and Zeleznikow2016) noted:

‘a field with no governance, standards and norms either do not exist or are relativistic, subjective, flexible, less visible, and less binding. They are more likely to be applied by inside players in a self-serving manner …. A lack of governance reduces users’ trust, sense of security, and confidence that the dispute resolution process is fair.’ (p. 312)

While it is difficult to have a governance structure that applies to all forms of ADR, it is important that access to justice, including both procedural and substantive, are active principles in the design, implementation and evaluation of ADR.

7 Conclusion

To assess the connection between the variety of ADR institutions/processes and access to justice, there is a critical need for ongoing empirical and in-depth research that not only provides data, but looks at the justice quality of ADR processes and access to justice. Evaluations of new developments should ideally be regularly conducted and the processes reviewed in a rigorous and contextualised manner. However, a substantial issue in evaluating Australian ADR institutions and processes and access to justice is the lack of data and information on the use and benefits of ADR (Productivity Commission, 2014, pp. 286–287, 308). Multiple inquiries have noted that more data collection is required relating to settlement rates, factors that influence settlement rates, what happens when a dispute fails to settle, party satisfaction with ADR, perceptions of fairness and efficiency in terms of time and costs (Law Council, 2018; Productivity Commission, 2014; Victoria Government, 2016; Australian Law Reform Commission, 2000). Research evaluating the justice quality of ADR processes in Australia is often piecemeal and limited in size. Whilst service providers may conduct evaluations of processes and programmes on regular bases, the outcomes are not made public, and the confidentiality of some ADR processes makes evaluations difficult.

A contributing factor to the limited empirical research is a lack of funding. Government funding could be directed at supporting ADR research to provide much-needed data to improve outcomes for ADR participants and government.Footnote 28 An exception to this limited research funding has been in the family dispute-resolution sector, where a variety of studies have been undertaken, particularly by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) and under the auspices of AIFS and the Family Law Council. Regardless, there is still a call for additional research in relation to specific issues in the family dispute-resolution sector.

With improved data and research findings, those concerned with improving access to justice can work to ensure ADR institutions and process are accessible to all – and, in doing so, ensure the delivery of just outcomes. ADR's role in enhancing access to justice requires an acknowledgement that public resources should be invested in it, such as by way of legal-aid funding, the investment of resources in policy development and the implementation, research and funding of community-based ADR services (Law Council of Australia, 2018; ADRAC, 2016a).

The increase in the number and variety of ADR institutions and processes is one critical aspect of improved access to justice in Australia. More people can get assistance to resolve their disputes, although there are still questions about whether this access is shared equally within the community. It is also known that legal problems are concentrated in certain vulnerable and disadvantaged communities (Coumarelos et al., Reference Coumarelos2012), but it is unclear how these groups fare in accessing ADR institutions and participating in ADR processes.

If ongoing development of ADR processes is to remain connected to improved access to justice, it is critical for ADR processes to be designed and implemented bearing in mind the type/nature of the dispute, parties involved and availability of resources, and to have an overarching objective of promoting access to justice for those who use them. This requires constant evaluation of outcomes of those processes to ascertain the type of justice that is being accessed and whether the legislative objectives are being met. The lack of data and consequently rigorous empirical research, however, means currently such assessments cannot be made.

Conflicts of Interest

None

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the reviewers for their comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Legislation and cases

Accident Compensation Act 1985 (Vic)

Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 (NSW)

Civil Dispute Resolution Act 2011 (Cth)

Civil Procedure Act 2010 (Vic)

Commercial Tenancy (Retail Shops) Agreements Act 1985 (WA)

Disability Act 2006 (Vic)

Discrimination Act 1991 (ACT)

Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (WA)

Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (SA)

Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (Vic)

Fair Trading (Farming Industry Dispute Resolution Code) Regulations 2013 (SA)

Family Law Act 1975 (Cth)

Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Act 2006 (Cth)

Farm Business Debt Mediation Act 2017 (Qld)

Farm Debt Mediation Act 1994 (NSW)

Farm Debt Mediation Act 2011 (Vic)

Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth)

Justice Legislation Amendment (Access to Justice) Act 2018 (Vic)

Mental Health Act 2014 (Vic)

Racial and Religious Tolerance Act 2001 (Vic)

Retail Leases Act 1994 (NSW)

Retail Leases Act 2003 (Vic)

R. v. Kirby and others; ex parte the Boilermakers’ Society of Australia (1955–56) 94 CLR 254

Workplace Injury Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 2013 (Vic)