THE GETTY OBJECTS

Introduction

Description

In 1975, the J. Paul Getty Museum (Getty Museum) acquired a set of silver and gold objects (objects 75.AM.54–61; Figures 1–8). Footnote 1 The objects consisted of a silver service of three cups (two of these, almost identical, had removable cup liners with handles; the third cup was in a different shape but had a similar Cupid motif), a jug with a satyr’s head on its handle, a ladle, and a jar/“psykter” (wine cooler), as well as a gold diadem and a gold ring (hereafter, this set of objects, including the jewelry, will be referred to collectively as “the silver service”) The museum does not know where or when the service was found, raising the possibility that they may be the product of illicit excavation and/or smuggling. Footnote 2 The objects seem on a stylistic basis to be of Roman origin, perhaps dating to the late Republic or early Empire, with comparanda from as far apart as Italy, Thrace, Syria, Turkey, and Sudan. Footnote 3 Without reference to further information about these items, therefore, it is impossible to be more precise about the objects’ origins, dates, or meanings.

Figure 1. A silver cup (JPGM 75.AM.54). Reproduced by permission under the J. Paul Getty Museum Open Content program.

Figure 2. A silver cup (JPGM 75.AM.55). Reproduced with permission under the J. Paul Getty Museum Open Content program.

Figure 3. A silver cup (JPGM 75.AM.56). Reproduced with permission under the J. Paul Getty Museum Open Content program.

Figure 4. A silver jug with the head of a satyr (JPGM 75.AM.57). Reproduced with permission under the J. Paul Getty Museum Open Content program.

Figure 5. A silver ladle (JPGM 75.AM.58). Reproduced with permission under the J. Paul Getty Museum Open Content program.

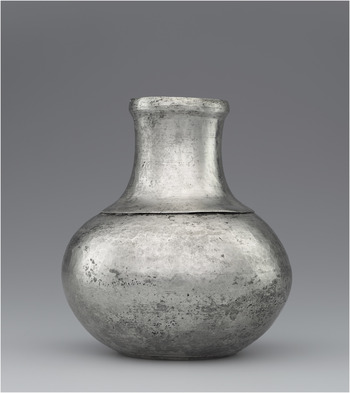

Figure 6. A silver jar or “psykter” (JPGM 75.AM.59). Reproduced with permission under the J. Paul Getty Museum Open Content program.

Figure 7. A gold diadem with inlaid glass/stones (JPGM 75.AM.60). Reproduced with permission under the J. Paul Getty Museum Open Content program.

Figure 8. A gold ring with a stone carved with the head of Polykleitos’ Doryphoros (JPGM 75.AM.61). Reproduced with permission under the J. Paul Getty Museum Open Content program.

From the time when the Getty Villa re-opened following its renovation in January 2006 up until the re-installation of the collection in 2017–18, these objects were on display in Room 105, which was dedicated to “luxury vessels.” The text accompanying this display of objects 75.AM.54–61 summarized the museum’s claims regarding the objects almost since their acquisition 42 years ago:

Vessels and Jewelry from a Burial: This group of vessels and jewelry is thought to come from a burial. It was found with a gold coin minted in Asia Minor (present-day Turkey) by the Roman general Mark Antony in 34 bc. The coin helps date the objects to the middle of the first century bc. The silver set was for serving and drinking wine; all that is missing is a large bowl for mixing wine with water and a strainer for filtering out sediment. The pieces belonged to someone wealthy enough to be buried with an expensive collection of silver as well as costly jewelry.

The purpose of this article is to investigate the specific origin(s) of the Getty objects, with the aim of providing the greatest possible precision. It will particularly consider the question of the objects’ relationship to the gold coin mentioned in the museum’s display text. The coin was notably never acquired by the Getty Museum, either at the time it purchased the silver service or at some later date. Yet the claimed relationship between the Getty objects and the coin is apparently one of the few pieces of evidence that could help us to understand where the objects were originally found and (as the museum itself notes) to identify their date. If, indeed, they were found in Asia Minor and date to the end of the Roman Republic, they would be among the first pieces of silver solidly attributed to this region that could confirm the importance of such items in that time and place and their suitability as grave goods.

This study is by no means the first attempt to clarify the origin, collection history, and ancient significance of objects that appear to have been associated with looting. A landmark investigation of this kind was carried out in the 1990s by Malcolm Bell, III, who was able to build a convincing case that a different set of silver, acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art between 1981 and 1984, had actually been illegally excavated around 1980 or 1981 from a Hellenistic house known today as the House of Eupolemos, in the ancient Sicilian city of Morgantina. Footnote 4 This silver had likely been made in Syracuse, was carried to Morgantina, and eventually buried in a period of siege in 211 bc during the Second Punic War. In successfully reconstructing the history of the Morgantina silver, Bell was able to rely on contemporary second-hand rumors of the silver’s discovery, its artistic style, his deep knowledge of the site, the work of the American expedition to the site since 1955, the recovery of an ancient legal document naming a son of Eupolemos (thus matching an inscription on one of the silver pieces), and the support of the Italian government to excavate and identify the actual find-spot of the silver. Can such an investigation be profitably accomplished for the Getty objects and the gold coin? Can we, in fact, expect that these kinds of recontextualizations are likely, or even just possible, for the vast number of other artifacts in public and private collections whose excavation went unrecorded? This article will also explore the answer to that question.

Historical Context for the Getty Museum and the Acquisition

At the time of the museum’s acquisition of the objects under investigation here, the organization was still under the control of its founder, J. Paul Getty, although he had already been living permanently in the United Kingdom for two decades. Since 1973, the museum’s curator for antiquities had been Jiří Frel, a Czech art historian who had previously worked at the Princeton University Art Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Frel’s responsibilities included identifying and purchasing major pieces for the museum collection, but before Getty’s death in June 1976, Frel had to have his choices confirmed by Getty. Footnote 5 After this date, Frel was under the supervision of the museum’s Board of Trustees. He continued in his role as chief curator until 1986 (though he was placed on paid leave after 1984). Footnote 6 Frel’s departure from the museum was reportedly related to an investigation by the US Internal Revenue Service of donation practices, in which he was said to have supplied falsified and inflated valuations of objects that the trustees had refused to buy. Donors would use the false valuations to claim substantially higher charitable deductions on their tax returns, and Frel would gain works he desired for the museum’s growing collection.

Publications

Introduction to the Public and Display of the Objects in the 1970s

The silver service’s first recorded display at the Getty Museum was on 1 June 1976—just five days prior to J. Paul Getty’s passing—as part of an exhibition of recent acquisitions. The exhibition brochure, written by Frel, contained at least one error as well as a story regarding the silver’s date that differed from the one later promulgated by the museum. Frel stated that “[t]hese 8 pieces were all found together in one grave, along with a coin of Mark Antony from 31 bc. … [The vessels] were made in Alexandria about 75 bc.” Footnote 7 As noted above, the coin that was linked to the silver actually dates to 34 bc. It is unclear whether the attribution of the vases to Alexandria or to a burial context were stories that Frel had received from the seller or his own deductions about their origin.

The connection to Alexandria and, indeed, to a single workshop for all of the vases, except the psykter, was restated in the fourth edition of the museum’s illustrated guide, written by Frel. Footnote 8 Likewise, the link to the gold coin (again given a date of 31 bc) was noted. Particularly interesting is the fact that this text states that a “plastic cast” of the coin was put on display in the same case with silver service. It is not known when the cast was removed from the display or why this happened (see discussion below, “Further Information about the Coin”). The image accompanying this text illustrated object 75.AM.55, showing that its liner and handles were intact but that the tarnish on the cup’s surface had not yet been cleaned.

Silver for the Gods

In 1977 and 1978, the jug (75.AM.57) was part of the traveling exhibition Silver for the Gods: 800 Years of Greek and Roman Silver. This show took place at the Toledo Museum of Art, the Nelson Gallery (today the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City), and the Kimbell Museum of Art in Fort Worth. The entry on the jug in the exhibition catalogue was written by Andrew Oliver, Jr. Footnote 9 With regard to its origins, Oliver said only that the jug’s provenance was unknown but that it had been “acquired in Lebanon.” Footnote 10 Oliver said that the jug had been purchased “with a ladle, two jars, and a pair of cups, all of silver, and a gold ring and diadem.” An explanation for the “second jar” may be that it is the same vessel as the third cup, though this is a strange nomenclature for what is clearly an open vessel. Alternatively, Oliver may not have seen the entire set at the time of his writing this catalogue entry and may have been relying on someone else’s (perhaps Frel’s?) flawed description.

Oliver’s Article

In 1980, Oliver published a full analysis of the Getty silver service that appeared in the museum’s own research journal. He called the service “a set of ancient silverware that ranks with the best of Greek and Roman silver ever to enter an American museum.” Footnote 11 To date, this article offers the most complete description and analysis of the set. It also included important information about the previous history of the objects as it was known (or claimed to be known) by the museum. Oliver wrote:

Before coming to Malibu, the objects are known to have been in Beirut, and the museum possesses papers from the department of antiquities of Lebanon authorizing their export. Beyond that, however, nothing is known for certain about their origins except that the silver and jewelry must have come from a site—surely a tomb—inland from the northeast shores of the Mediterranean, and not from Egypt, Greece, or Italy. Footnote 12

Oliver thus stated that the objects had been legally acquired, even though the location of their discovery was apparently unknown. No explanation for the lack of a find-spot was given. Neither was there any discussion of the objects’ collection history prior to their acquisition by the Getty Museum, including how long the objects had been in Lebanon prior to entering the collection. The name of the collector, gallery, or dealer from whom the purchase was made was likewise not given in Oliver’s publication nor was the price or the location of the purchase stated.

Early in the article, Oliver gave an expanded version of the story that was later told in the museum’s wall text, saying: “An aureus of Mark Antony, struck in Asia Minor in 34 bc and alleged to have been found with the silver and jewelry, could not be acquired by the museum but is represented here by a plastic cast.” Footnote 13 Neither the original coin nor the cast was shown in any of the images in the article. According to Oliver, the original coin could not be purchased by the museum because it had been sold at an auction in Munich in 1973—indicating, in other words, that if the coin had been available the museum would (or at least might) have tried to buy it together with the other objects. Footnote 14 As a source for the 1973 sale, he cited a catalogue published by the numismatic auction house of Gitta Kastner. Footnote 15 Since it was difficult to determine the date or the specific origins of the Getty objects from their style, the coin formed a critical component of Oliver’s interpretation of them. He characterized the aureus as the traditional payment for the ferryman to Charon, the land of the dead. Footnote 16

Also for the first time, an argument concerning the origins of the silver was presented in a scholarly publication. The argument did not attribute the silver to Alexandria, as Frel had previously done. Instead, Oliver linked the assemblage of a silver service, gold adornments, and a gold coin to a few archaeologically excavated and published burials containing the same typological ensemble of grave goods found in and around modern Kayseri (ancient Caesarea) in Turkey. Footnote 17 The first tomb, excavated in 1940 at Beştepeler, contained gold jewelry, silver vessels, and an aureus minted by Julius Caesar in 46 bc (unpublished, but reported by Oliver to have been on display in the Kayseri Museum in 1974). Footnote 18 The other tomb, which was found in a park called Gültepe, adjacent to the Kayseri Museum, was excavated in 1971 in advance of the construction of a hospital building. The tomb was a built chamber within a tumulus called Garipler. It housed the remains of a young woman buried with gold and silver objects, which were published by the local museum director, Mehmet Eskioğlu. Footnote 19 An aureus of Augustus (given a date of ad 15 by the excavator) was found as well. In another publication, Eskioğlu also mentioned a second tumulus at Beştepeler that was subject to a rushed excavation in 1960 and was found to contain a gold coin. Footnote 20 Oliver noted that a jug in the Kayseri Museum (Inventory no. 2144, unpublished, no find-spot given by Oliver) has “a plain body and tall, narrow neck” similar to the “least refined” of the Getty silver vessels, the so-called psykter. Footnote 21 Finally, Oliver stated that “fragmentary remains of bronze vessels were also said to have been once associated with the [Getty] group,” although he did not offer further information about these objects’ disposition, history, and location or a source for this information and claimed relationship, and it appears that the museum did not acquire them. Footnote 22

Pfrommer’s Article

In a 1983 discussion of formal connections between Greek and Roman silver table vessels, Michael Pfrommer (then of the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut in Istanbul) mentioned one of the cups (object 75.AM.55) and the jug with the head of a satyr (object 75.AM.57), again in the museum’s journal. When introducing the cup, Pfrommer said it was “from Lebanon” and cited Oliver’s 1980 publication. Footnote 23 Initially, the jug was only said to be in the museum’s collection and was not even linked to the cup described earlier. Footnote 24 Slightly later, however, Pfrommer remarked that “the findspot (Fundort) [of the jug] is Lebanon.” Footnote 25 It is unclear, however, whether these statements represented a new story promoted by the museum, a misunderstanding by Pfrommer of Oliver’s discussion of the objects’ provenance, or a disagreement by him with Oliver’s conclusions.

Künzl’s Article

In 1997, Susanna Künzl wrote an article for an exhibition catalogue on the form and function of Roman silver table services, including among her examples the Getty service (the Getty service was not a part of this show, which took place in Cologne). With regard to the set’s origins, she stated clearly that its find-spot was unknown, though she also repeated the claim that it was found with a coin. Footnote 26 She was convinced on formal grounds that the silver formed a set and, in fact, that they had all been the product of the same workshop. Künzl noted particularly that the three cups not only had Cupid motifs but also that their feet were “identical.” In reality, the molding on the stem of the taller cup is somewhat smaller than those on the other cups, but perhaps this observation is overly precise in the context of ancient craftsmanship. In any event, one could point to the so-called “Solomon-Bocchoris” silver cup in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (object 24.971), which also has an extremely similar foot but was excavated at Meroë in the Sudan, far from any suggested find-spot for the Getty service. In a related footnote, Künzl underlined the formal similarities of the jug, cups, and ladle in their “secondary details, such as the handle-attachments and feet,” which she saw as indicative of a single workshop. Footnote 27 She did not mention the psykter (which is arguably quite different in style from the other vessels) or the set’s relationship to the jewelry.

The Ring

In 1992, the Getty Museum published a catalogue of its collection of gems and finger-rings written by Jeffrey Spier. Footnote 28 The ring that was part of the silver service appeared in this publication and was even featured on its front cover. Footnote 29 The ring features a cut stone decorated with a profile head from a famous classical sculpture, the Doryphoros (“spear-bearer”) by Polykleitos of Argos (active in the fifth century bc). According to Spier, this ring is the only known example showing this subject on a gem. He suggested comparisons with works by known Greek gem carvers of the first century bc, such as Gnaios and Solon, but he did not specifically attribute it to one of these artists. Regarding the ring’s origins, Spier repeated the mention of the coin first put forward by Oliver and accepted Oliver’s conclusion, saying: “[It] is said to be from a hoard containing late first-century silverware, a gold diadem, and a gold aureus of Marc Antony with his son Antyllus. … The coin, which was in mint condition, suggests a date for the burial of circa 34 bc. Provenance: From Asia Minor.” Footnote 30

Summary of Public Descriptions of the Service’s Provenance and Acquisition

The lack of footnotes or other citations for the statements made by Oliver about the objects’ origins and their relationship to the coin appear to indicate that his source(s) for information came from within the museum itself, either from staff such as Frel or from the documentation that accompanied the objects. Footnote 31 Oliver has recently stated in a personal communication to the author that he never examined any export documents, however, leaving Frel as his sole source for this information. Spier cited Oliver’s publication and a previous publication of the ring in the museum’s 1988 guide to the collections that repeated the same information. More recent guides to the collection (2002 and 2010) are no different. The fact that these publications’ appearance in venues owned and operated by the museum suggests that the assertions made within them about the objects purchased and owned by the museum are something more than scholarly—they are official institutional statements. The agreement of the display text describing the objects with Oliver’s and Spier’s writings confirms this interpretation.

More Recent Information about the Origin of the Getty Objects

New official information has appeared recently regarding the history of the Getty objects. In response to questions from the author about the objects in 2012, the Getty Museum stated that they had been acquired from Antike Kunst Palladion, a Basel, Switzerland, gallery owned by Gianfranco Becchina. Footnote 32 Becchina is an Italian citizen who has been implicated in the smuggling and sale of looted antiquities, especially from the south of Italy and Sicily. His name appeared in the famous “organigram” recovered by Italian police in 1994 that listed participants in the illicit antiquities trade and their relationships to each other. Antike Kunst Palladion and Becchina’s storerooms were raided by police on several occasions beginning in 2002, leading to the seizure of thousands of objects as well as his archives. He was tried and convicted by an Italian court in 2011. Footnote 33 Becchina sold objects from other parts of the ancient world besides Italy, including the eastern Mediterranean and Near East. The Getty Museum alone counts at least 110 objects of Near Eastern origin purchased from Antike Kunst Palladion in its online catalogue, including a set of 33 Parthian silver and gold vessels and jewelry dating to the second century ad, which were acquired in 1981. Footnote 34

Oliver stated in a personal communication to the author in 2013 that he believed that Frel had seen the coin with the service and jewelry at Antike Kunst Palladion. Unfortunately, Becchina’s archive has not been published, but two scholars in possession of copies of it have confirmed that three of the objects purchased by the Getty Museum—one cup, the jug with a satyr on its handle, and the ladle—appeared in four photographs (Figures 9–12). Footnote 35 Additionally, a stamp apparently made from the stone in the ring also appeared in its own photograph (Figure 13). These pictures appeared consecutively in the archive. This fact could indicate that they formed a set, but it could just as easily indicate that Becchina was simply marketing them as a set—or it may not have any significance at all. In the images, the pieces have not yet been restored. The jug (the only piece from the service for which two pictures appeared in the archives) showed a piece of adhesive tape across its belly, perhaps indicating a hole (Figure 10). The jug and cup both showed signs of tarnish. Two decorative flanges that extend outwards from the bowl and handle of the ladle in the Becchina photograph were at some later period bent back to attach to the bowl rim. The cup (object 75.AM.54, with the image showing what the museum refers to as “Side B”) is missing its handles, indicating that its liner was not inserted at the time the photograph was made. Footnote 36 None of the other pieces from the service acquired by the Getty Museum appear in the Becchina archive. The coin likewise does not appear anywhere in the documentation seized by the Italian police.

Figure 9. Image of object JPGM 75.AM.57 from the archive of Gianfranco Becchina, seized by Italian police (courtesy of Christos Tsirogiannis).

Figure 10. Image of object JPGM 75.AM.57 from the archive of Gianfranco Becchina, seized by Italian police (courtesy of Christos Tsirogiannis).

Figure 11. Image of object JPGM 75.AM.58 from the archive of Gianfranco Becchina, seized by Italian police (courtesy of Christos Tsirogiannis).

Figure 12. Image of object JPGM 75.AM.54 from the archive of Gianfranco Becchina, seized by Italian police (courtesy of Christos Tsirogiannis).

Figure 13. Image of stamp made from object JPGM 75.AM.61 from the archive of Gianfranco Becchina, seized by Italian police (courtesy of Christos Tsirogiannis).

THE GOLD COIN

It is time now to consider what other information exists about the gold coin that the museum claimed is associated with its objects. It is certain from the references in the Getty Museum’s publications and other sources that the coin exists. It is less certain that the coin actually is related to the silver service, but, if it is, it may be of great significance for unraveling the story of the Getty objects prior to their purchase by the museum.

Description/Historical Context

The coin is a particularly rare Roman gold coin of a type known as an aureus (Figure 14). Footnote 37 It was made by a military mint that traveled with Mark Antony while he was on campaign in Asia Minor and Armenia in the spring and summer of 34 bc (the campaign was described by Dio Cassius in his Roman History). Footnote 38 The coin features Antony’s head in profile facing right on the obverse and the head of his son, Mark Antony Junior (nicknamed Antyllus), facing right on the reverse. The coin represents the earliest appearance of a father and son on Roman coinage. There are reportedly no more than 10 extant coins from this issue, and this particular example has been recognized in several publications as the finest one. The mint condition of the coin seems to indicate that it was hardly used prior to its deposition. As Spier noted in 1992, it stands to reason that the coin would not have moved far or been used for long. If it was buried with the silver service, this would seem to indicate that the service was deposited somewhere in or near Asia Minor or Armenia quite soon after 34 bc.

Figure 14. A gold aureus minted by Mark Antony in spring/summer of 34 bc while on campaign in Asia Minor and Armenia. Mark Antony on the obverse, Mark Antony Junior (aka Antyllus) on the reverse (formerly in the Hunt Collection; current whereabouts and ownership unknown; courtesy of acsearch.info, https://www.acsearch.info/).

Sale History

As with the Getty objects, the history of the coin is complex, involving a published set of documents and claims by various people involved in the story. This article will therefore first explain what was claimed by the museum to have happened as well as what was recorded in print when the coin appeared in various publications. It will then discuss what other information has since emerged as part of this investigation regarding the coin’s journey from one collection to another. As previously noted, Oliver stated in 1980 that the coin was not available for purchase by the Getty Museum in 1975 with the silver service because it had been previously sold at an auction. The coin was indeed offered for sale at an auction held by Gitta Kastner in Munich in November 1973, where it comprised Lot 212. Footnote 39 This seems to have been the first appearance of the coin in public view. The catalogue entry for the aureus, written by the numismatic scholar Peter Robert Franke, noted its extreme rarity as well as its mint condition, with only a small scratch on the reverse side. No information was offered regarding the coin’s origins or its collection history, nor did Franke connect the coin to a set of silver and gold objects. Footnote 40 The anticipated price was 200,000 Deutsche marks (roughly US $75,500 at the going exchange rate, which was approximately equal to the individual values of several of the objects in the silver service). Footnote 41

Following the auction, the coin did not appear again in public until 1983, when it was shown as part of a collection assembled by Nelson Bunker Hunt and William Herbert Hunt, two brothers who were the scions of a Texas oil fortune. The exhibition, entitled Wealth of the Ancient World, displayed the objects acquired by the Hunts over a period of no more than five years of collecting. Footnote 42 The catalogue entry for the aureus makes no mention of its collection history or find-spot. No relationship was claimed to the objects, which had, by now, been in the Getty Museum’s collection for almost eight years. This fact appears all the more unusual because Oliver’s article describing the purported relationship had appeared in a major scholarly publication disseminated by the museum three years earlier, and Arthur Houghton, then assistant curator of antiquities at the Getty Museum, had written the introduction to the section of the catalogue regarding the Hunts’ coin collection. Footnote 43

The Hunt brothers were forced to sell their collection when they were declared bankrupt by a court following an ill-fated attempt to corner the global market in silver. The collection, including the aureus, was sold at Sotheby’s in New York in June 1990 (the original estimate for the aureus was US $50,000–70,000; it was sold for US $104,500). Footnote 44 Once again, no mention was made in the catalogue of the coin’s origins or of a connection to the Getty objects. It was sold again a year later at Bank Leu in Switzerland (“[f]rom a distinguished American collection”; the original estimate was 120,000 Swiss francs, and it sold for 140,000 Swiss francs). Footnote 45 The most recent public sale of the coin seems to have been in March 2010 at Numismatica Ars Classica in Zürich, where a telephone bidder purchased it for 450,000 Swiss francs (with an original estimate of 250,000 Swiss francs). Footnote 46 The coin’s current whereabouts are unknown.

Once again, in none of these more recent sales was any statement made about the original find-spot of the coin or the possibility that it might be connected to a set of well-published objects in the collection of a prominent museum. Footnote 47 It is not clear why coin collectors have apparently remained ignorant of the Getty’s claims about the coin. In discussions with well-informed coin dealers during the research for this article, none claimed previous knowledge of the Getty’s story, and several expressed surprise at it. Catharine Lorber, the author of the catalogue entries for the coins in the 1983 Hunt collection show, said:

I have to express some skepticism about the alleged provenance of the aureus. It strikes me as odd that this fascinating information was not divulged either to Peter Robert Franke or to me, when it would have added to the allure of a very rare and valuable coin. Coin dealers always want lengthy text to accompany especially important coins, even if there is nothing interesting to say. It’s therefore hard to believe that they would have suppressed this particularly interesting information, which beyond enhancing the coin might have facilitated the sale of the treasure. Footnote 48

Jeffrey Spier, who mentioned the coin in his publication of the Getty ring, is known to have been active in the numismatic trade. Footnote 49 But Spier’s knowledge of the claimed relationship between the coin and the service also did not become widespread. Indeed, on the basis of Lorber’s statement, it even seems unlikely that dealers and collectors know, but disbelieve, the story promoted by the Getty Museum since the existence of the claim (however untrustworthy) would augment the notoriety and worth of the coin and, thus, would likely have appeared in sales catalogues or other publications. Footnote 50

Further Information about the Coin

As it turns out, even the coin’s initial appearance on the market is shrouded in secrecy. The Getty Museum and several scholars have claimed that it was not acquired by the museum because it was sold at the 1973 Kastner auction. In reality, as confirmed both by Kastner’s subsequent publication of achieved prices and by a personal communication from Peter Robert Franke in 2013, the coin certainly did not find a buyer at this auction. Franke noted that the official consignor of the coins for the Greek and Roman part of the auction was another Munich dealer, Egon Beckenbauer. However, Franke stated in a letter that there were rumors that the coins (especially “the best pieces,” though, as he put it, “which ones?”) were actually consigned by one or more Turkish sellers. Footnote 51 Although he could not vouch for the authenticity of these rumors, contemporary discussion apparently centered on a gentleman called by the name “Mister Fuad” or something similar.

A well-known antiquities dealer in Munich in the second half of the twentieth century was a Turkish citizen named Fuat Üzülmez, owner of Artemis Galerie. Other dealers who worked with Üzülmez, such as Bruce McNall (co-owner of Summa Galleries; see discussion below, “Bruce McNall”), were used to calling him only by his first name. According to the journalist Suzan Mazur, Robert Hecht’s daughter called him “Uncle Fuat.” Footnote 52 In articles in Connoisseur magazine in 1988 and 1990, Üzülmez was linked by Turkish journalists to organized crime and the illicit trade in antiquities from that country, and he was the subject of investigations by police for those alleged activities. Footnote 53 In April 1975, German police discovered a suitcase full of coins, gold jewelry, and a terracotta vase belonging to Üzülmez at the Frankfurt airport; it was seized and turned over to the Turkish consulate. Footnote 54 It seems at least possible—perhaps even likely—that Üzülmez and the “Mister Fuad” remembered by Franke are the same person.

An unexpected, but relevant, development occurred when the author made a request to the Getty Museum in 2013 for information regarding the “plastic cast” of the coin reported by Oliver to be held by the museum. The museum responded that the cast could not be located. Footnote 55 The Lebanese export document described by Oliver also could not be found. An investigation of the relevant files by curatorial staff, however, did reveal that the museum had received a letter, dated 1 December 1975, from a certain Pierre Nonnweiler of Brussels who offered to sell the aureus. Footnote 56 The Nonnweiler letter stated that it was a response to a letter by Frel of 10 November 1975. Footnote 57 It is worth noting that the Getty possesses a letter from Antike Kunst Palladion dated 1 September 1975, stating that it had sent the silver service from Switzerland to Malibu. Footnote 58 This transaction, therefore, must have been completed slightly earlier, presumably in August. In making reference in his letter to photocopies of the Kastner catalogue previously provided to Frel, Nonnweiler stated that he possessed the coin and was willing to sell it for 300,000 Deutsch marks (roughly US $120,000 at the historical rate). Footnote 59 The denomination of the sale price in marks rather than Belgian francs might well indicate that the coin (or its true owner) was still located in Germany.

From Nonnweiler’s letter, it appears that Frel was trying to acquire the aureus in November 1975. Footnote 60 Yet the museum clearly did not purchase the coin from Nonnweiler following his offer. One possibility why the coin was not bought is that J. Paul Getty was not interested in collecting them; there has even been a suggestion that he did not like them because of their ancient association with death. Footnote 61 In a personal communication in 2017, Spier revealed that Frel had written a description of the museum’s collection in the 1980s, though it was never finished. In his discussion of the silver service, Frel wrote:

[J. Paul Getty, who] had only moderate sympathy for English or even French silver, was similarly luke-warm about ancient silver … A modest but good set of six pieces (jug, ladle, three cups, strainer) appeared on the market. Getty liked the photographs and still more one cup shown to him on approval and had transmitted to the dealer the recommendation to purchase the whole set. The set cost far more money than Getty intended to spend. Negotiations were protracted for one year and then for another … Getty liked it very much, enjoying the fact that it was a complete set, but he refused categorically to spend any money for the aureus which went with the set. This was not to save money, but because the set came from a grave and the coin was in the dead man’s mouth to pay the ferryman, an idea that did not appeal to Getty. Footnote 62

There is substantial pertinent information in this passage, though Frel’s documented activities (such as those that led to his forced retirement) require it to be treated with caution. For example, he stated that the (unnamed) dealer showed six items, not eight. The ring and diadem were not mentioned anywhere in the text nor was one of the two jugs. At the same time, a strainer—perhaps confused with the ladle (though it has no holes)—was stated to be present. Footnote 63 The extent of the negotiations seems to push Getty’s first awareness of the setback to 1974 or possibly even 1973. Frel clearly claimed that the aureus “went with the set,” which was “complete.” This completeness may have meant that Frel understood that all of the silver vessels in the original tomb were for sale together, not that all items found in the tomb were present, if we recall Oliver’s reference in 1980 to unacquired “fragmentary bronze vessels.” Footnote 64 The mention of the coin being “in the dead man’s mouth” may simply have been a broad generalization of ancient practice, but if it actually transmits the story of the burial that went with the silver service and/or with Marc Antony’s aureus, it is worth noting by contrast that Eskioğlu had identified the deceased person in the Garipler tumulus at Kayseri as a young woman, and the associated gold coin was found not in the mouth but, rather, “nearby.” Footnote 65

With regard to the coin, Frel’s text seems to indicate that Getty refused to purchase it when he bought the service; again, likely around August 1975. But this cannot account for the coin’s subsequent availability from a different source in November and December (perhaps even as early as October, given the date of Frel’s letter, as cited by Nonnweiler). It is hard to imagine Getty would reconsider a decision he had made only a few months earlier, and Nonnweiler’s letter makes no claim or acknowledgment of a relationship between the coin and the silver. Did Frel bring it to Getty’s attention as being associated with the set only when Nonnweiler offered it? Was he trying to acquire the coin only because he wanted a major numismatic collection at the museum? Footnote 66 If so, why did he continue to promote the story of a connection between the silver service and the coin after Getty failed to buy it, and why did he not acquire it following Getty’s death in 1976?

Bruce McNall

After Nonnweiler’s failed offer of the aureus to the Getty Museum, the coin found its way into the Hunt collection. Almost all of the works collected by the Hunt brothers, including the aureus, were bought from Summa Galleries, a Beverly Hills business owned by Bruce McNall and Robert Hecht. Footnote 67 McNall had begun as a coin dealer, then later partnered with Hecht, who acquired art in Europe and sent it to California for McNall to sell. Footnote 68 McNall has stated that he sold the aureus “for at least $100,000” to the Hunts sometime around or after 1981 and, moreover, that he had received the coin from Üzülmez (from whom he had received many other objects). Footnote 69 The possibility thus emerges that Nonnweiler’s 1975 letter was part of an effort by him, together with Üzülmez, and perhaps also Becchina, to maneuver looted antiquities into public collections via multiple avenues, so that the objects’ illicit origins would be disguised. This possibility seems all the more likely since a long relationship has been documented between Becchina and Nonnweiler. Footnote 70 The Italian prosecutor Paolo Ferri referred to this strategy as “triangulation” in the cases of dealers like Becchina and Giacomo Medici. Footnote 71

McNall stated that he did not know Pierre Nonnweiler (and there is no evidence to show that he did). McNall further stated that he was unaware of the Getty Museum’s claim of a link between its objects and the coin. This point is surprising since a close relationship has been documented between McNall and Frel in the period following J. Paul Getty’s death. McNall and Hecht sold many objects to the Getty (at least 70 are still in the collection, according to a search of the museum’s online catalogue). According to the reporting of journalists Jason Felch and Ralph Frammolino, Frel also worked with McNall on his previously mentioned scheme to have wealthy Angelenos (including well-known celebrities) purchase objects from Summa Galleries and donate them to the museum. Footnote 72 In many cases, it seems the donors never even received the objects from Summa; instead, they went directly from the gallery to the museum. In this way, Frel was able to collect objects that he found desirable but that he could not convince the new Board of Trustees to purchase. These artworks frequently had illicit, or at least mysterious, origins. Frel also allowed McNall to place objects available for purchase from Summa on display in the galleries of the Getty Villa, where he would bring prospective buyers for visits. The close contacts between McNall and Frel again raise the question: if McNall had the coin in the late 1970s or the early 1980s, and if the story linking the coin to the silver service was true, why was Frel unable (or suddenly unwilling) to acquire it?

2017 RESPONSE FROM THE GETTY MUSEUM

Export Permits

The Getty Museum’s 2017 response to the author’s queries also revealed the existence of the Lebanese export permits first mentioned by Oliver. Footnote 73 The museum said that the papers were found separated from the documentation for the silver service in a file belonging to an unrelated object. The documents, originally in Arabic but with signed and stamped official translations in French, were provided to the museum by Antike Kunst Palladion in a letter dated 1 September 1975. Footnote 74 The letter was signed “R.J. Becchina” (probably indicating Ursula Juraschek, Gianfranco Becchina’s wife, who went by the name “Rosie”). Footnote 75 The permits are the only ones from Lebanon known to be in the museum’s possession. Footnote 76

At this point, it may not be surprising to the reader that these documents raise more questions than they answer. Footnote 77 Rather than a single permit that concerns only the objects acquired by the Getty Museum, plus the coin, there were two separate permits plus associated documents, with vague descriptions that seem to include some of the objects in the silver service while omitting at least one of them. They also include several other objects that were not bought by the museum and that may or may not have been associated with the service when it was discovered. No mention is made in any of the documents of a find-spot for any of the listed objects. The permits were signed by “Dr Hareth al-Boustani” and bear stamps from the Directorate-General (Dr Hareth Boustany was the director of the Beirut Museum, and the permits bear notes stapled to them, in English, reading: “Please observe the stamp of the Museum of Beirut,” which was presumably an addendum by Antike Kunst Palladion for the Getty Museum). Footnote 78

The first document dates to 18 March 1974 and is listed as Export Permit no. 39. It begins by stating that the pieces on the document belong to Hassan Tawil, living in Rue Bechara El-Khoury in Beirut, and that they will be sent through customs at the Beirut airport. It also notes that the Directorate-General is not certain that the pieces mentioned in the permit are authentically ancient. An associated document states that the pieces were “sold to Hassan Tawil or John Nawad” at an address given as Hotel Jura, Basel, Switzerland. The seller’s name is not given. The permit itself is vague, stating that it covers “11 petite pièces en bronze, 5 pièces d’or, 4 statues en argile, 1 pièce en argent” (“11 small pieces in bronze, 5 pieces of gold, 4 clay statues, 1 piece in silver”). Footnote 79 The associated document goes on to clarify some of the included items: “[C]uillere en argent avec manche decoré; bague en or avec pierre tête masculine, diademe en or orné de pierres, statue Assyrienne poterie, vase en bronze, pelle en bronze” (“[S]ilver spoon with decorated handle; gold ring with stone [showing] a male head, gold diadem adorned with stones, clay Assyrian statue, bronze vase, bronze shovel” [items from the silver service in boldface]).

The second permit dates to 10 May 1974 and mentions only Hassan Tawil, with the same Basel address as before. The permit, no. 61, cites “5 pièces en argent diverses de genre et d’époque” (“5 pieces of silver of different types and periods”). The sale document clarifying some or all of the objects reads as follows: “2 coupes en argent decorées avec anses, aiguillere en argent antique sans decore, vase en argent sans decoration, vase forme coupe” (“2 decorated silver cups with handles, antique silver needle without decoration, silver vase without decoration, vase in the form of a cup”). One more document is from the Directorate-General of Customs and confirms to airport customs officials that the objects for the second permit had gone through the proper export protocols. Footnote 80

Unfortunately, none of the permits or associated documents unequivocally mention the silver jug with the head of a satyr or the aureus. Footnote 81 The “vase without decoration” may refer to the psykter. Included with the permit documents supplied by Antike Kunst Palladion were 10 photographs, illustrating each of the eight pieces individually, as well as one photo for each pair of handles for the cups (as these seem to have been detached at the time the photos were made). These photos each had a stamp from the Lebanese Directorate-General of Antiquities on the reverse, presumably indicating that they had been shown and verified at the time of the issuance of the permits. The photo of the jug in this set of photos was identical to one of the photos in Becchina’s archive (Figure 9), but the photo of the ladle was different, possibly showing that it had not yet been cleaned prior to coming to Switzerland (in Becchina’s image, the tarnish is gone from the handle [Figure 11]). The photo of the cup (object 75.AM.54) shows side B/A heavily encrusted or tarnished. Becchina’s photo shows side B, which is cleaner, but part of side B/A is visible and shows the encrustation, seeming to indicate that this vessel had not been cleaned before the permit pictures or Becchina’s archive pictures were taken (Figure 12).

The dates on the permits suggest that Becchina could not have shown the silver to J. Paul Getty (except perhaps in photos) prior to May 1974. Frel’s story about the negotiations (discussed earlier) claimed that the aureus was included with the set by this point. Yet neither the coin nor its cast was shown in any photos, raising doubts about its connection to the silver and about whether Becchina ever possessed it. The full relationship between the permits and the photos supplied by Antike Kunst Palladion (and those in the Becchina archive) likewise remains slightly mysterious. Specifically, why is the jug not mentioned in the permits even though it appears in a photo stamped by the Directorate-General, yet that same photo is in the Becchina archives as well as another one showing the vase in clear disrepair prior to conservation? What implications do these confusing facts have for our understanding of the service as a unified set?

The “Plastic Cast”

In its 2017 response, the museum also revealed that, although the whereabouts of the coin’s “plastic cast” were still unknown, a photograph of the cast had been discovered (Figure 15). The picture does appear to represent a cast made from the specific coin from the Kastner auction and the Hunt collection, or a facsimile of it, though there appear to be cracks in the cast. According to Jeffrey Spier, the photograph had been made by the museum, but nothing more was known about it, including the date it was made. The museum did possess, and even displayed, the coin cast at one point, as demonstrated by its mention in the 1978 guide to the collection. According to the guide to the first exhibition in 1976, however, it was not on display nor was it even mentioned. Did the cast come with the silver service in September 1975? If so, it would have allowed Frel and/or Getty to confirm that the coin offered by Nonnweiler a few months later was the same one Becchina claimed went with the set and the same one offered at the Kastner auction. Following this line of thought further, we may imagine that Becchina told Frel and Getty that the coin existed and that he did not have it because it had sold at auction but that he knew who did have it: Nonnweiler. Indeed, according to Christos Tsirogiannis, an affiliate researcher of the Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research at the University of Glasgow, Becchina’s archive reveals that he was in correspondence with Nonnweiler at least between 1974 and August 1978. Footnote 82 This may have been the original method of triangulation concocted by Becchina, Üzülmez, Nonnweiler, and perhaps also Frel. Footnote 83 On the other hand, if the cast arrived between 1976 and 1978, its presence may have been enough to convince Frel that he did not need the original, thus explaining why he stopped trying to acquire the aureus.

Figure 15. Photographs of the “plastic cast” of the Antony/Antyllus aureus in the J. Paul Getty Museum collection (reproduced by permission of the J. Paul Getty Museum; no inventory number; cast now reported lost).

Getty Conservation Reports

The Getty Conservation Institute performed routine conservation checks on all of the pieces in the service in 2015 and 2016. The author was permitted to examine these notes in 2017. According to the notes, some of the pieces required treatment at this time—cleaning and/or repair—while the reports on other pieces indicated prior service to reattach sections. The objects that required the most extensive attention seem to have been objects 75.AM.54, 56, 57, and 59 (one of the pair of cups, the tall cup, the jug, and the psykter). In the first case, extensive cleaning was needed, and this work revealed that the cup liner had adhered to the outer cup casing. Inside, the inner portion of the cup casing appeared to have never been cleaned, and it included accretions that may have included dirt from the original deposition. Similar traces of accretions appeared in smaller quantities on several of the other vessels. It appears that no sampling was done of this material. The other three items all showed signs of having been reconstructed using an adhesive that ultimately failed: the foot of the tall cup became detached; the jug handle became detached; and the neck and rim of the psykter separated from the lower part of the vessel. The tall cup also apparently had a single handle originally that was indicated by a hole for its attachment; the conservator noted that the handle’s absence may have been caused by damage during burial or excavation. These notes therefore give some indication of the state of the artifacts when they were discovered. The photographs that accompanied the export permits show that major repairs were made to the items before they arrived in Switzerland, that these repairs may not have been done entirely professionally, and that the repairs were not accompanied by treatment of the surface encrustations or tarnish on the silver items in the service.

QUESTIONS

A variety of questions, some already noted, are raised by the different stories associated with the Getty pieces and the gold coin. These questions relate both to assertions made about their collection histories and to gaps in the stories. The primary consideration, however, is to what extent the questions impact our ability to understand these objects, their meanings, their significance, and the context in which they were created, used, and deposited.

The Silver Service and the Gold Coin

Perhaps the most important question that is raised is whether the evidence supports the Getty Museum’s story regarding a relationship between their objects and the coin. Arguments in favor of believing the museum’s claim of a link to the coin rely on accepting that Frel had passed up the opportunity to purchase an object he clearly desired and that he apparently believed was linked to other objects already in the museum’s collection, even after J. Paul Getty’s death and even though it was easily available to him from Nonnweiler or McNall. It also relies on the fact that coin dealers and collectors have almost willfully ignored the claimed link for more than 40 years, despite the increase in value and interest such a link would provide. Arguments in favor of discarding the museum’s claim, on the other hand, include:

-

• the coin’s failure to sell at the Kastner auction, despite repeated later claims to the contrary;

-

• the contemporary rumors that it was consigned to that auction by Üzülmez, a dealer who had been implicated in the contemporary illicit antiquities trade;

-

• the likelihood that Nonnweiler’s letter falsely claimed that he possessed the coin;

-

• the report that the coin passed from Üzülmez through the hands of McNall, another discredited dealer, into the Hunt collection;

-

• the fact that no images or other contemporary documentation have yet emerged to show that the silver service and the coin were ever in the same location;

-

• the fact that photographs of only three of the objects from the service appear in Becchina’s archive, while the aureus was absent from the same documents;

-

• the fact that the Lebanese export permits appear to describe some of the objects but that they divided them into at least two groups exported at different moments, while omitting at least one object from the service as well as the coin; and, of course,

-

• the fact that no published description of the coin over at least a 37-year period (1973–2010) has ever mentioned the silver service, apart from those put forth by the museum. Nor does it appear that any coin dealer, collector, or scholar (apart from Spier) was ever aware of the Getty’s story. Footnote 84

It is certainly tantalizing to believe that the coin and silver were found together in a late Republican tomb in central Turkey, smuggled out of the country through Lebanon by Üzülmez and/or his associates, divided, and offered at auction (the coin) and sold or transferred to Becchina (the silver service). As the research presented here unfolded, it initially appeared that this would be the correct story. Demonstrating a clear link between the coin and the silver might even have bolstered a case for restituting the silver to Turkey.

Given the weight of the arguments listed above, though, it now appears that the museum’s claim cannot be trusted. Thus, there is no reason to believe that the coin is in any way related to the Getty’s silver service. Indeed, as a result of this investigation, the museum now agrees that the evidence to connect the coin to the silver is “very tenuous.” Footnote 85 The coin has turned out to be (in the apt phrase of one of this article’s anonymous reviewers) nothing more than a red herring. In an ironic twist, and despite the likelihood that these items were illicitly excavated and smuggled out of their country of origin, the recognition of this particular red herring means that the increased obscurity of the silver service’s real history now likely insulates the museum from a claim of restitution from Turkey or any other nation.

In the summer of 2017, the Getty Museum removed any mention of the coin from the text that accompanies the re-installed display of the service. The text now reads: “These eight objects of exceptionally fine workmanship were probably found together in a tomb. The silver vessels formed a set for serving wine. The thin gold diadem decorated with garnets and glass likely adorned the body of the deceased.” No statement is made about the possible find-spot of the service. The museum has maintained its interpretation of dates for the items in the service (“50–25 bc”), despite the fact that the coin was the only clear evidence to suggest such a potentially narrow range of years. Perhaps, most notably, the museum has apparently declined the opportunity to discuss the background of their acquisition of the silver service or the change in its interpretation of the service relative to the coin. This seems unfortunate as it would have been an excellent chance for the museum to educate a public audience about the ways in which institutions like the Getty Museum used to operate in the art market and the changes that have been made in recent years, particularly in light of the excellent work being carried out by the museum’s provenance research team.

The Origins of the Silver Service

In addition to concerns over the dating and geographic context for the silver service, our level of skepticism regarding the service may need to be raised even further. For there is now no reason to believe even that the objects acquired from Antike Kunst Palladion have any relationship to each other. Footnote 86 As previously noted, only three of the pieces (plus an impression from a fourth piece) clearly appear in Becchina’s archives, and there is no text description of them or reference to them in these documents—only photographs. Perhaps most importantly, the associated export permits do not provide a clear picture of the service as a unitary set. The three cups in the “set” share formal similarities, especially Cupid motifs, that could certainly connect them to each other, but, otherwise, there is simply no independent evidence to support the identification of some or all of these objects as a group. Footnote 87 This is not to claim that they cannot be, or must not be, a group; rather, it is simply to clarify precisely what may be said about them with any confidence: almost nothing. Andrew Oliver’s 1980 discussion of a possible find-spot around Kayseri, Turkey, was an exemplary display by a master scholar of the use of stylistic details and research in the form of obscure, but compellingly grounded, comparanda to make a case that entices readers to believe that we might be able to reconstruct these objects’ histories, even without knowing who found them or when and where they were found. Likewise, Susanna Künzl’s theory that the silver vessels were made by the same workshop (discussed above) remains essentially speculative in the absence of clear information that they were even found in the same or similar location.

A stylistic comparison with other known works introduces still greater complications. There are, in fact, numerous possible comparanda for the two elaborate cups in the service (objects 75.AM.54–55). Two silver cups in the same shape, but with a known find-spot, came from Boscoreale, Italy (today in the Louvre), and a third, already mentioned, was from Meroë in Sudan (Boston Museum of Fine Arts, object 24.971). These items, therefore, do not narrow the potential location of discovery for the Getty service. Three more silver cups, recently acquired by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (object 1997.83), the Princeton University Museum of Art (object 2000-356), and by the collectors Leon Levy and Shelby White in New York, respectively, are virtually identical to the Getty cups in the shape of the bowl and have similar handles. Footnote 88 All three have a Greek name, Sisimis (Boston and New York) or Sis (Princeton), inscribed on their feet, perhaps linking them to each other. Footnote 89 The stem and feet of the three cups have markedly different moldings from the Getty cups, and they include floral decoration on their feet. They also feature Cupid-like (albeit wingless) putti who stretch their arms up and across their bodies. The paucity of extant ancient silver, however, makes it impossible to know how frequently these motifs were used, even by the same workshop. The Boston, Princeton, and New York cups all lack published find-spots, and the Boston Museum of Fine Art reports on its online catalogue that it acquired its cup from Robert Hecht. Footnote 90 Michael Padgett, curator of antiquities at the Princeton museum, wrote that Hecht was not the source of his institution’s cup, but he declined to indicate who the seller was, stating that it is the museum’s policy to withhold that information. Footnote 91

Two more cups, again without a known find-spot, were also in the Levy-White collection, one with the name Sisimis (or similar) incised on its foot, but these had high-swung kantharoid handles and a different treatment of the foot from the trio published by Oliver. Footnote 92 Finally, in 2003, Cornelius Vermeule published yet another silver cup (missing its handles, stem, and foot) with the same shape as the cups with handles in the Getty service. This cup was in “a private collection in southern California … known to specialists in Greek and Roman plate for a number of years. … [and] said to have been found in the lands of Roman Imperial Parthia” (the Parthian homeland was in northeastern Iran, but in the early Roman empire, the boundaries of their territory included parts of modern Turkey, Syria, Jordan, Armenia, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan). Footnote 93 Vermeule compared the privately owned cup to another one in the Toledo Museum (object 1961.9; no find-spot; “place of origin: Ancient Rome, from Asia Minor”). Vermeule’s conclusion was that the California cup was made in a Phrygian city—that is, western inland Asia Minor—in the Augustan or Julio-Claudian period, but given the lack of find-spots for both this example and the Toledo comparandum, there is simply no secure evidence on which to base this argument. Indeed, a list (not necessarily comprehensive) provided to the author by Andrew Oliver included 35 Roman silver cups attributed to the first century bc or the first century ad—though not the two in the Getty service—that had emerged on the American art market. Footnote 94 Of these, only two (5.7 percent) had known find-spots: the cup from Meroë and another one from Vicarello, Italy, in the Cleveland Museum (object 1966.371). If the Getty cups are included, the percentage of grounded examples out of all early imperial Roman silver cups in the United States drops to 5.4 percent.

The reality, unfortunately, is that because the Getty silver service and the aureus came to market without a collection history or a find-spot; because they are associated with dealers known or alleged to traffic in illicit antiquities; because the silver service was acquired by a curator who was documented as having actively broken both laws and ethical guidelines in the name of building a world-class collection, and the aureus by collectors who were unconcerned with a lack of transparency with regard to the origins of their purchase; and because hardly any similar examples have a known find-spot either—for all of these reasons and in spite of the presence of apparently authentic export permits—the Getty silver service and the aureus of Mark Antony and Antyllus now can tell us practically nothing about the ancient Mediterranean, except merely that these objects existed. With the collapse of the Getty Museum’s story about the silver service and the coin, our hope of understanding the service’s provenance, its date, and the objects’ relationship to people (and other objects) in the distant past simply evaporate.

Although it is true that we can study the style, iconography, and manufacture of these objects, as many scholars have done, this information is ultimately not very useful to art historians and archaeologists if we cannot also say where or when they were made or why. We are left unable to identify, for example, whether what might appear to be stylistic similarities signify chronological contemporaneity, archaizing tendencies, the influence of one period or artist on another, or simply pure coincidence. Comparison with another well-known category of ancient artifacts—painted Athenian pottery—shows the problems faced by Roman silver. J.D. Beazley’s famous attributions of artist names to Athenian vases in the twentieth century were only useful for understanding the development of painting and the ancient Athenian pottery industry because we can be sure from scientifically recorded finds and scientific sampling of clay sources and vessels that the vases were made in Athens and because there is enough other corroborating archaeologically sourced data to mostly confirm their chronological seriation.

Otherwise the system is a house of cards—guesswork that has been given a veneer of logic and authority. In classic articles on the intellectual consequences of the art market’s esteem for antiquities in 1993 and 2000, Christopher Chippindale and David Gill demonstrated this loss of critically important contextual information when looted antiquities are acquired through the legitimate art market. Footnote 95 Elizabeth Marlowe’s recent study of the “core” works of Roman art history, many of them having surfaced in unclear circumstances, further demonstrates the problems that such objects create for scholarly understandings of the past. Footnote 96 Gill also criticizes, primarily together with Michael Vickers, the effect of the modern art market on the study of painted Greek pottery as artwork, relative to the objects we believe to have been much more highly prized in antiquity—silver and gold plate. Footnote 97 The unfortunate fact is that it is currently almost impossible to make clear comparisons that would elucidate the relationship between ceramic and metal art production, not only because the vast majority of metal vessels were recycled into other objects but also because almost none of what does survive has a known find-spot and, therefore, a clear date or context for its production and use.

Attempted (but Failed) Recontextualization: Worth the Effort?

In the case of the Getty silver and the aureus, even though it was possible to learn a great deal that was previously unknown about these objects over the more than four years of painstaking research, such as Nonnweiler’s offer of the coin to the museum in 1975 or the rumors circulating around the Kastner auction in 1973, we are ultimately left with a story whose foundation is made of quicksand. This experience suggests, then, that Malcolm Bell’s success during the 1990s in reconstructing the provenance of the Morgantina silver is likely the exception rather than the rule. Even the existence of an archive of documents collected by a dealer involved in the trade of looted antiquities; the seizure of that archive by law enforcement authorities; and the cooperation of the museum that acquired the group of objects from the dealer, which allowed this researcher to examine the relevant files, is not sufficient in this case, or (one would therefore have to surmise) in many similar cases where less information is preserved, to re-establish the original find-spot of this group of objects. In this way, the intellectual consequences of collecting antiquities signaled by Gill and Chippindale are all the more starkly underlined.

Even what has been learned in this case is largely due to the particular willingness of some (but not all) knowledgeable parties to speak on the subject, since there is little published or archival material that can be brought to bear on it (hence, the reliance on “personal communications,” rather than on documents, to add important details to the story as well as the frequent use of words and phrases such as “reportedly” and “stated to be”). There is very little that can be stated with full confidence about the silver or the coin. The Getty silver service is thus a prime example—and a depressing reminder—of what has been lost due to looting and the desire to collect ancient objects even when they have no find-spot or collection history. The Getty Museum’s recent exhibition of the Berthouville silver, whose nineteenth-century discovery and ancient context are well understood further emphasize this loss. Footnote 98 The Berthouville set, a third-century ad cache from Normandy, France, consisting of a mixed set of vessels apparently dating to several periods, was found in a sanctuary. It speaks eloquently to the ways in which ancient Roman worship practices, tradition, and luxury could intersect, even in rural parts of far-flung provinces. Nothing like that is now possible with the Getty silver or the coin.

At the same time, there is some value in attempting to reconstruct the histories of ungrounded objects wherever some evidence might exist. In the case of the coin, it appears possible, and perhaps even likely, that it was looted from a Turkish context and offered for sale with several other looted coins (including the finest example of the earliest known coin in the world). Footnote 99 As for the Getty silver, we have learned how little we can trust the stories put forward by dealers, even when the objects in question are accompanied by legitimate export documents. It also hints at what was previously known about networks of dealers who worked together to try to move objects into collections, now showing that this might have happened irrespective of whether the objects were actually related to each other. This will be an important subject for future researchers to consider further as they examine the trafficking of illicit antiquities and the possible invention of false relationships to create desire among collectors. Finally, this example shows that even the presence of legitimate export documentation is not clear proof of a licit origin. In this sense, a failed recontextualization is valuable mostly for showing what we still have to learn about what we do not know.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

I am extremely grateful to Malcolm Bell, III, David W.J. Gill, Carla Antonaccio, and Christos Tsirogiannis for reading various early drafts of this article and offering their sage advice. I also thank the Alexander Bauer and the International Journal of Cultural Property’s anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and comments. Any errors remain my responsibility alone. In addition to the numerous scholars, art dealers, and numismatic experts cited in the text and footnotes below, thanks must also be offered to Jeffrey Spier, Claire Lyons, Assaad Seif, Anne-Marie Afeiche, Nicole Budrovich, Judith Barr, and Christopher Lightfoot for their assistance with various aspects of this investigation over the years. Finally, I would like to take this opportunity to thank Mavrick Gaunt, a student in my ART 260 course at Chapman University in the fall of 2012, who took part in a class exercise to study unprovenanced objects in the J. Paul Getty Museum collection. Gaunt drew my attention to the unusual story linking the silver service to a gold coin that was not in the museum but, instead, had found its way into a private collection owned by Nelson Bunker Hunt and William Herbert Hunt (Spier Reference Spier1992, 95). This information motivated the investigation whose results form the basis for this article.