Introduction

In accordance with the sovereign right of states to formulate and implement cultural policies and adopt measures (Article 5.1 of the Convention), the Parties are encouraged to develop and implement policy instruments and training activities in the field of culture. Such instruments and activities should aim at supporting the creation, production, distribution, dissemination, and access to cultural activities, goods, and services with the participation of all stakeholders, notably civil society as defined in the Operational Guidelines.Footnote 1

The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (Convention on Cultural Diversity) was ratified in 2005 by 148 states with only the United States and Israel voting against it.Footnote 2 It emerged in the context of a long-running “trade and culture” debate that had flared up again significantly in the late 1990sFootnote 3 and was initiated by non-profit initiatives—including the International Network on Cultural Policy, a forum of the cultural ministers of World Trade Organization (WTO) member countries, and the International Network for Cultural Diversity, an umbrella group for individual artists, national cultural non-governmental organizations, and activists—that feared a predominance of globalized artistic and creative products and services. It can be seen as a result of some previous acts in the fields of culture, trade, and heritage, such as, for example, the 2001 UNESCO Declaration on Cultural Diversity and was the first binding international convention in the cultural field.Footnote 4 Considered in the context of the international norm setting, the convention conflicts with the goals and values of free world trade represented by the multilateral trade rule-setting WTO and leaves out the subject area of intellectual property.Footnote 5 According to Mira Burri, the Convention on Cultural Diversity is the first legally binding, encompassing convention on culture, but it suffers from a “lack of binding obligations” and a confusing number of “soft” and non-binding recommendations, a “substantive incompleteness” with a missing focused framework of action, and an “ambiguous relationship with other international instruments” such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the General Agreement on Trade.Footnote 6 Still, it opens up a basis of legitimation for states and, thus, opportunities to specifically promote the diversity of cultural forms of expression.

Since 2007, after the convention came into force, the first monitoring instruments were created, and the first projects were initiated and implemented. As of mid-August 2020, 107 reported projects in the fields of awareness raising and capacity development include training and empowering artists, technology transfer, the mobility of artists and cultural and creative products, bilateral and multilateral cooperation, strengthening rights to arts and culture, and so on.Footnote 7 Due to the enormous complexity of the projects and the lack of empirical knowledge about their impact dynamics, the contracting states have enjoyed a great deal of freedom in the implementation of the convention, but it should be mentioned that the International Fund for Cultural Diversity can only provide limited funds for programming. Larger initiatives must be financed by and within the respective contracting states themselves.

Switzerland has responded to the call of the Convention on Cultural Diversity and has begun to develop programs to protect and promote the diversity of cultural expression in its country. In Switzerland’s federal democratic system, which is strongly subsidiarity based due to its many private foundations and numerous associations, the local regions are particularly important for the convention’s implementation. For this reason, the Swiss National Arts Foundation Pro Helvetia has developed a program called Cultural Diversity in Non-Urban Regions, which is designed to help the regions develop suitable implementation tools.Footnote 8 Within this program, the six cantons of central Switzerland have developed the concept of Regional, Cross-Cantonal Cultural Competence Centers. The main idea of this instrument is to build up capacity, knowledge, and participant structures that foster, renew, and mediate the regional peculiarities of Central Switzerland in a particular field of artistic activity. The respective competence centers are from the fields of literature, cultural events, folk music, and contemporary art.

The aim of this article is to discuss, using the example of an evaluation of four regional cultural organizations, the extent to which they show potential to develop into sustainable centers of excellence capable of promoting the diversity of cultural expressions (according to the Convention on Cultural Diversity) in their specific artistic field of activity. From 2016 to 2018, a program evaluation was carried out consisting of four case studies with an explorative character. In the following discussion, the methods, case studies, and results of the program evaluation are presented to generate implications for the systematic exploration of the question of whether, and under which conditions, the institutionalization and concentration of resources threatens or even fosters the diversity of cultural expressions.

Cultural diversity, regional governance, and regional cultural organizations

The concept of “cultural diversity” is based on the Convention on Cultural Diversity, which was first ratified in 2005. Accordingly, cultural diversity refers to the manifold ways in which the cultures of groups and societies find expression. These expressions are passed on within and among groups and societies.Footnote 9 States that have ratified the Convention are encouraged to foster cultural expressions along the whole value chain (creation, production, dissemination, and distribution) within the system of cultural production,Footnote 10 paying particular attention to women and social groups and including those “belonging to minorities and indigenous peoples.”Footnote 11 This rather fuzzy, open concept leaves a lot of space for interpretation and allows a great variety of state activism, leading to various kinds of effects and impacts.Footnote 12

A great challenge for states in the implementation of the Convention on Cultural Diversity is to find effective ways and governance modes to bring real changes in behavior among cultural actors. Here, local and regional government levels come into play since a high proportion of value creation and innovation in the cultural sector is produced at a local or regional level—for example, in the museum sector, tourism, or the economic development of small cultural businesses.Footnote 13 In the federal system of Switzerland, in particular, regions play an important role as most cultural policies are implemented on a cantonal and local level. Regional governance is complex, however, because it refers to tripartite forms of self-governance with players from politics, civil society, and the economy.Footnote 14 It becomes even more complex since cultural diversity is subject to rapid development through technological changes such as digitalization, the influence of globalized cultural practices, and specific immigrant cultures. Cultural diversity in the local regions is changing, and regional cultural organizations, which are key players in this setting, are being challenged to face these changes.

Regional cultural organizations are often characterized by grassroots work and are often based on voluntary engagement and small business entrepreneurs.Footnote 15 These regional and local governance systems are largely mixed-financed, self-regulating systems and, therefore, only partly controllable by the state. This complicates the implementation and monitoring of the Convention on Cultural Diversity. Nevertheless, within the regional culture production system, artistic products often have the character of “inclusive social goods.”Footnote 16 : The creative output is less concerned with high-priced high culture and more open to the amateur art, subculture and popular culture opportunities of artistic creation. This promotes democracy, a sense of community, and solidarity and provides a foundation for all kinds of cultural expression, artistic products, and performances.

The Swiss context and the idea of regional cultural competence centers

Switzerland is a semi-direct democratic federal republic and has an Anglo-Saxon, liberal tradition with a traditionally low government engagement in relation to gross domestic product.Footnote 17 The cantons (regional governments) and communes have authority over a wide range of matters and high autonomy. In this subsidiarity-based system, the federal government only takes on tasks that the cantons and communes cannot manage on their own. Culture has gained major importance in the last 15 years, especially with the entry into force of the first Culture Promotion Act in 2012, with the federal government becoming more involved in cultural matters, even though most decision-making power still lies with the 26 regions and the 2,250 communes.Footnote 18 The central government acts in close cooperation with the regional governments through the coordinating body known as the National Cultural Dialogue. The highly nested cultural governance interconnects with the steadily growing cultural and creative industries, the traditionally strong foundation sector, and the numerous cultural associations (like choirs, music orchestras, and theatres) that are highly organized into interest groups and professional associations.

Switzerland ratified the Convention on Cultural Diversity on 16 July 2008. A multilingual country, Switzerland, with its distinctive regional identities, views itself culturally as an extremely diverse country, and this diversity is also defined in the Swiss Federal Constitution.Footnote 19 This constitutional understanding of cultural diversity is often applied to the preservation of Swiss traditions, the country’s four languages, and regional customs. Despite, or perhaps thanks to, this firmly anchored understanding of cultural diversity, Switzerland is generally very open to implementing the Convention and has set up several legal instruments and action plans, including the Federal Law on Cultural Promotion and the Federal Action Plans on Cultural Promotion.Footnote 20 Since 2015, the Swiss National Arts Foundation Pro Helvetia has financed a program for the implementation of the Convention on Cultural Diversity in the Swiss regions (of which this research project is part). One of the main challenges in the system of Switzerland is transferring the Convention’s principles to a regional and local level.

Central Switzerland consists of the cantons of Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Obwalden, Nidwalden, and Zug. The region is, to an extensive degree, economically, socially, politically, and culturally heterogeneous and diverse. In addition to urban centers such as Lucerne, which attracts a great deal of international tourism and has over 80,000 inhabitants, and the globalized, small town of Zug, with 30,000 residents from 127 countries, there is a regional environment comprising, on the one hand, intact traditional village structures and, on the other hand, growing agglomeration areas where village life is threatened by a high turnover of residents. Within the scope of this study, we have focused on the non-urban areas. Cultural diversity in the Swiss regions is subject to many challenges. For example, the cultural region’s connecting elements are the Roman Catholic tradition and folk culture. However, as a result of high immigration rates (between 11.5 percent in Uri and 27 percent in Zug), a high integration capability has been demanded. Furthermore, although the region has the highest social capital rate in Switzerland,Footnote 21 membership in associations is declining, and it is increasingly difficult to recruit volunteers and committee members. In addition, like many places in the world, the region has been confronted with social trends such as digital transformation, individualization, and eventization (short-time engagement). Due to its self-governance structures, the large number of actors involved, and the scarcity of resources, cultural development is difficult to steer. The question arises as to how the diversity of regional culture can be sustainably promoted in light of these challenges.

The idea for the regional, cross-cantonal cultural competence centers was initiated by the coordination body of the Zentralschweizer Kulturbeauftragten-Konferenz (KBKZ), in which the six cultural offices of Central Switzerland are represented. In order to promote and strengthen their regional, often voluntary, work-based structures of material and immaterial cultural heritage, the decision makers have decided to pool resources in order to build up capacity in a targeted manner. As competence centers, the regional organizations under scope are meant to develop, collect, and convey specialist knowledge within their cultural fields or areas. In contrast to conventional cultural institutions or pure event organizers, competence centers should be involved in all cultural aspects of action along the whole value chain. Regional competence centers are thus more than a pure event venue; they are also a place of production and reflection, a network, and a contact point. With a broad knowledge in cultural production, they support the regional participants. Regional competence centers should be characterized by a clear, enduring, and sustainable organizational structure. Their employees and voluntary personnel should be professionalized networkers and promoters and actively implement the guiding idea of cultural diversity. These functions should be concentrated in a physical location, which is seen as the basis for creating a sustainable environment. A pooling of resources and simultaneous differentiation among the regional competence centers should ensure a purposeful promotion of cultural diversity within the region.Footnote 22

Research questions

However, the idea of the regional cultural competence centers needs to be considered carefully. It has to be asked whether the institutionalization process is actually beneficial or might in fact hinder cultural diversity. On the one hand, the pooling of knowledge and resources can counter the regional decline in voluntary resources, and a targeted approach can strengthen effective action. This approach reflects the idea of the resource-based view in organizational theory.Footnote 23 By bundling resources such as the coordination efforts between the many cultural operators, transaction costs in the regional cultural competence centers can be reduced.Footnote 24 With the development of core competencies such as knowledge in a particular cultural field or a concentration of specific products and cultural themes, region-specific products can be better placed in the globalized arts market.Footnote 25 On the other hand, there is a danger of destroying small-scale, decentralized organizational structures and centers of cultural creation that are so important for the production of culturally diverse audiences, products, and ideas. According to a critical view from a sociological, cultural production perspective, a concentration of knowledge and resources paired with “oligopolistic control” can lead to the homogenization of cultural creations and less diverse cultural products.Footnote 26 In this way, small-scale structures of cultural production might foster the diversity of cultural expressions and products. In this respect, the regional and local level is deemed to be a good starting point for the implementation of the Convention on Cultural Diversity.Footnote 27

Against this background, the following questions arise:

-

• Under which conditions can the Convention on Cultural Diversity be implemented at the regional level?

-

• Are existing regional arts organizations capable of fulfilling the role of a regional cultural competence center? What criteria must be met to fulfil such a role? What challenges do regional cultural competence centers face? What recommendations can be given for further organizational development in light of the Convention on Cultural Diversity?

-

• How do regional organizations promote cultural diversity? Are the means that are selected by regional organizations suitable for achieving this goal? What can arts organizations and projects do to foster the diversity of cultural expressions along the cultural value chain (mechanisms of production and participation)?

-

• What social and economic effects are expected to be generated and with what long-term impact? What evaluation criteria should be used to evaluate regional competence centers? What links exist between the cultural diversity initiative and its observed effects? What recommendations for the implementation of the Convention on Cultural Diversity at a regional and local level can be formulated for decision makers, organizations, and projects?Footnote 28

These research questions are the basis for evaluating the concept of regional competence centers in Central Switzerland. Six cantonal cultural offices (known as the KBKZ) work in cooperation and have selected four cultural organizations as potential regional competence centers, each handling a particular relevant cultural issue such as literature, cultural events, folk music, and contemporary art.

Methodologies and research plan

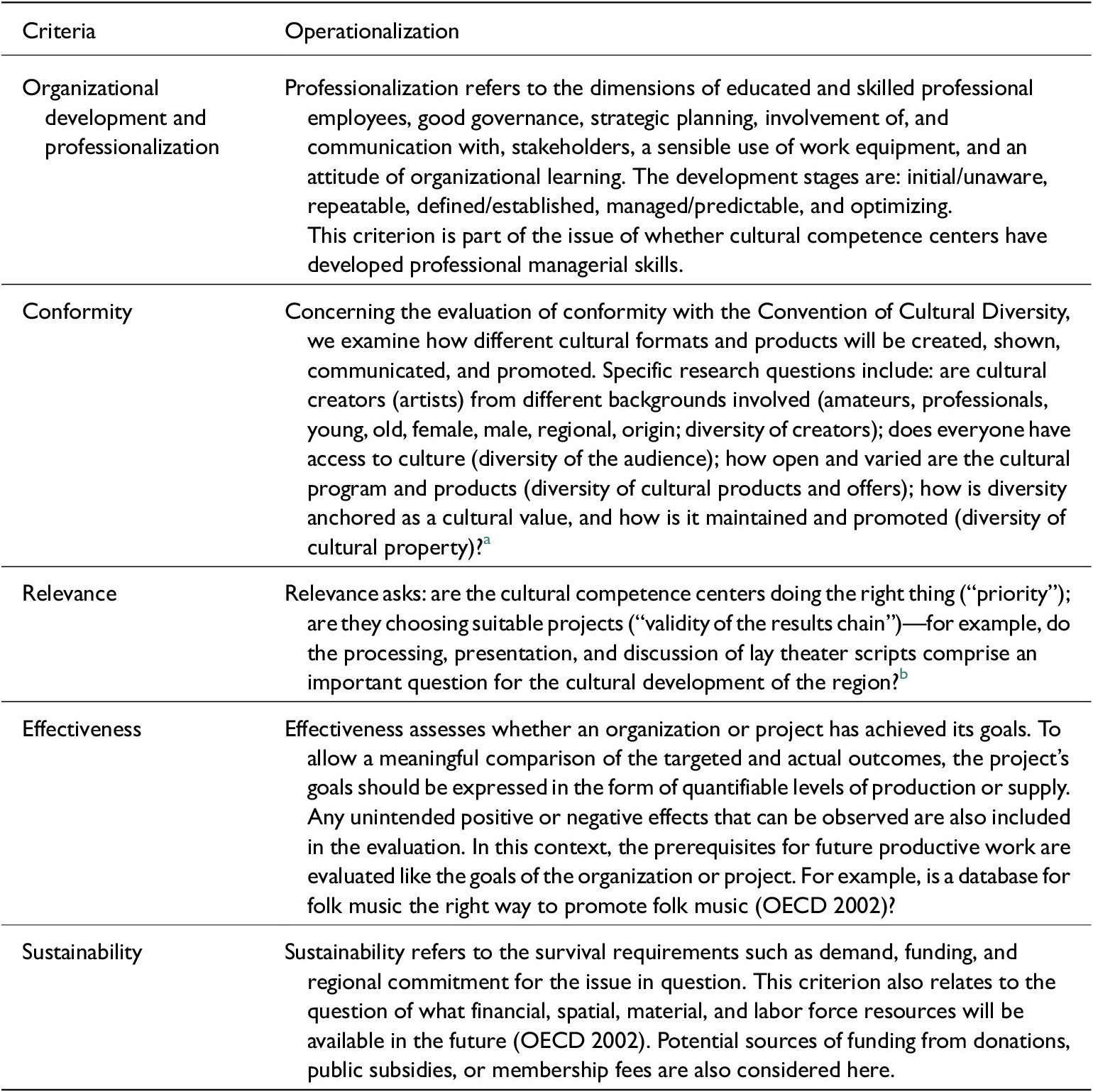

In the field of program evaluation, case studies have received some attention.Footnote 29 This research project has an evaluative case study character: “The case study strategy may be used to explore those situations in which the intervention being evaluated has no clear, single set of outcomes.”Footnote 30 To analyze the research questions, a purely deductive approach has not been chosen since the questions to be addressed are relatively new and unexplored. Instead, an evaluative, practice-oriented approach has been selected to capture the complexity of the topic. On the organizational level, a focused comparison of the four organizations was intended.Footnote 31 Due to the great variety of projects, a comparison at the project level, on the other hand, made less sense. Together with the public clients and cultural organizations, the following criteria were developed to assess the four cases: competence centers should (1) work professionally and develop their organizational managerial capabilities; (2) meet the criteria for creating diverse cultural expressions; (3) develop projects relevant for society and development of arts and culture; and (4) act in an effective and (5) sustainable manner. The criteria were operationalized as specified in Table 1.

Table 1. Operationalization of evaluation criteria

Notes:

a Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions, 20 October 2005, 2440 UNTS 311.

b Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Glossary of Key Terms in Evaluation and Results Based Management,” 2002, http://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/2754804.pdf.

Based on these clarifications, the evaluation concept was developed, which is based on a three-level evaluation model containing regional, organizational, and project levels. On the organizational and project level, the five criteria defined are used for evaluation. The regional level is seen as a reflexive reference framework proposing region-specific preconditions and external influences for the institutions and projects to be examined. Overall, unintended effects were taken into account. Data collection was performed using various evaluation tools and methods as listed in the research plan (Table 2).

Table 2. Research plan

The evaluation process lasted 2.5 years (ongoing evaluation). After the development of an evaluation concept in cooperation with the actors involved, an organizational assessment was carried out to determine the degree of managerial professionalization and the sustainability of the project’s organization. The pilot projects were developed on the basis of cultural diversity criteria set by the evaluators. Project proposals were then assessed for their regional relevance and further funded. The implementation of the projects was accompanied and evaluated according to qualitative and quantitative criteria with regard to their requirements for promoting the diversity of cultural expressions.

Objects of investigation: The cases

Four cultural organizations in the fields of literature, folk music, contemporary arts, and cultural events were tested for their ability to develop into regional competence centers. All four organizations are relatively small and have a maximum of three employees and an actively assisting committee. Their share of public funds lies between 50 and 70 percent. To ensure anonymity, the organizations are not explicitly named. Four specific developmental projects were defined as pilot projects with two aims: (1) to further organizational development and (2) to promote cultural diversity. The aim of the pilot projects was to promote and mediate diverse forms of cultural expression specifically in their respective fields in order to sensitize the employees of the cultural centers to these topics. The projects differ in their goals and cannot be compared directly.

Case 1: Literature

The Center for Literature and Language of Central Switzerland opened in 2014. In addition to readings and talks, literary and musical performances, and writing workshops, it also offers platforms for topic-specific discussions and a series of workshops. It is organized as an association and encompasses seven active board members and 220 passive memberships.

With the explicit intention of further developing itself as a regional competence center, the center developed a project involving amateur theater scripts. Central Switzerland has a unique tradition of high-quality amateur theater that ranges from amateur dramatics and productions by the independent theatrical scene to diverse outdoor events and the legendary “Wilhelm Tell” theater productions in Altdorf. Performed by amateurs, a large number of productions are based on plays by authors that are well known nationally or internationally and are staged by experienced, professional directors. Theater in Central Switzerland has an entry in the list of living traditions in Switzerland (Lebendige Traditionen in der Schweiz), which is funded by the Swiss Federal Office of Culture. Amateur dramatics in Central Switzerland reaches a broad and cross-generational audience, is anchored in communities, and plays an essential role in the cultural self-understanding of the region. Accordingly, the center has conducted a series of events concerning the writing and staging of amateur theater in Central Switzerland.

Case 2: Folk music

The rural region of Central Switzerland has a strong folk music tradition and an entry on the list of living traditions in Switzerland. The Center for Folk Music has existed since 2007 and handles all matters concerning Swiss folk music, including information and advisory services, courses and events, the promotion of folk music among children and young people, education in schools, teacher training, and research and documentation.

To develop the regional competence center, the organization established a national database on folk music, beginning with an inventory of the music by a well-known local folk musician. Since the turn of this century, the Swiss folk music scene has flourished, and there has been a growing interest on the part of the media. Promising young musicians have further developed their folk music involvement thanks to excellent training and their own abilities. The rebirth of this tradition is part of the renewal process. In the last few years, extensive musical material has been handed over to the Center for Folk Music to be preserved for posterity. For this reason, the Center for Folk Music has developed a digitally accessible database. The objective of this database, which is financed by the center itself, is to make available to the public, to conserve the music sheets, to build a basis for research, and to widely communicate and convey folk music. These goals are regarded as being necessary since folk music is often kept in private archives and is therefore difficult to access.

Case 3: Contemporary arts

The Association for Contemporary Arts is located in an industrial building under monument protection and was founded in 2004. The hall was built in 1921 and is an imposing building. The owner is the local municipal power company, which donated the hall for use in September and April. In recent years, the association has organized its own exhibitions and an art market each fall. The most important event in the calendar is an international performance festival that traditionally takes place on the second weekend of September. Since 2014, the association has entrusted an experienced performance artist with the artistic direction of the festival.

With a new performance project, the association wants to enter new territory and involve the local population and region more strongly in contemporary performance art. For the first time, the festival has left the industrial hall and moved into the center of the village, utilizing public and private rooms. The performances were given on the spot and reflective of particular local situations. This pilot initiative raises the question of whether the public and local culture can succeed in hosting the festival and be involved in future activities.

Case 4: Cultural events

For over 15 years, the Association of Cultural Organizers has been committed to a lively cultural event in rural Lucerne. Cooperation between event organizers started with the membership of four small theaters and has now expanded to 25 institutional memberships. They regularly meet, exchange and launch ideas, and jointly promote culture in the country. The association has set for itself goals to make cultural diversity in rural areas of Lucerne more accessible and to promote cultural concerns. Since 2007, the association has organized annual cantonal music festivals. Originally occupying a single day but now covering a period of 10 days, the association’s members present their programs. The role of the association’s organizers has been to collate everything in a joint event program and to ensure comprehensive media coverage.

For its tenth anniversary, the association was planning a very special jubilee program. For the first time to date, it was aiming to send audiences on different cultural tours to visit cultural events at various locations scattered throughout the cultural landscape. This pilot project should, if the response to the jubilee program by its members and the general public is positive, become more institutionalized and foster cooperation between the regional event organizers.

Findings of the program evaluation

All four organizations and their pilot projects were evaluated, which included 1,446 visitors, 93 events, 71 artists/formations, 48 media articles, eight art branches, and one database with over 16,000 records. The results are roughly summarized below according to the criteria to be investigated.

Organizational development and professionalization

Organizational development of the evaluated organizations was measured by an assessment tool for arts and non-profit organizations, which classifies the organizations into an organizational development stage based on an assessment of practice-proven items.Footnote 32 The development stages are: initial/unaware, repeatable, defined/established, managed/predictable, and optimizing. The following dimensions were assessed: strategic planning, operation management, good governance, educated/skilled employees, the use of work equipment, the involvement of, and communication with, stakeholders, and the attitude of organizational learning. The data collected was interpreted by the researcher and classified according to the tool containing diverse items. The organizations showed a different level of development with regard to the development of their managerial skills. The confidential results specified in the evaluation report included the stage of professional development for each organization, including recommendations for the improvement for each dimension.

Conformity with the Convention on Cultural Diversity

A workshop and interviews with key stakeholders have shown that the Convention on Cultural Diversity and its objectives, principles, and content were not well known at a regional level. It was confirmed that the preservation of Swiss traditions, the country’s four languages, and local customs were understood as stipulated in the Swiss Constitution. However, the idea of cultural diversity was shown to be unconsciously present in all of the organizations. For example, although participants were aware of the necessity to include immigrant cultures and to integrate cultural and technological change, the promotion and protection of cultural diversity had not yet been included as a guiding principle in any of the organizations in question and was being neither deliberately developed nor promoted. Nor was cultural diversity to be found in strategic objectives or implementation planning. For example, a variety of people (amateurs, professionals, young, old, female, male, local, Indigenous) were involved in all of the organizations. A targeted inclusion of specific groups, however, took place only in part. Similarly, management committees displayed some diversity, but this lacked clear direction. Furthermore, while, in theory, access to culture for all groups is supported by the organizations, this was not always the case in practice. For example, access to the venues for disabled people was not always possible. All of the organizations were open to all target groups, such as immigrants, but immigrant culture had a low priority in the cultural formats being produced and mediated. One criterion for the approval and financing of the pilot projects was that they should specifically promote the diversity of cultural expressions.

Regional relevance

The results of the project documents and interviews suggested that all four organizations were well or very well interconnected in the region and had developed a fine sense of what were considered to be relevant topics and projects. All developed projects concerned relevant regional topics, genres, and kinds of artistic expressions. Organizational and project priorities were well established, and, as far as is known, the preconditions of the projects were suitable for fostering the development of regional competence centers:

-

• With the workshop talks at the amateur theaters, the Center for Literature and Language has dedicated itself to a topic that is relevant to the region and has so far attracted little attention. By going out to the theaters, the center has opened up to a new audience group.

-

• The Center for Folk Music has promoted a regional folk music artist by tendering a competition. The reinterpretations of the folk music pieces have given rise to new artistic-creative forms and have included musicians of various musical styles. Additionally, through the competition, the database for Swiss folk music has been publicized.

-

• The program of the cultural events project can be described as being very diverse. Designed as a bus tour, the audience gained insights into different cultural genres and venues across the whole region.

-

• In the arts performance project, together with the village residents, a variety of artistic formats have been created and performed in different locations in the village.

Effectiveness

Although all of the organizations set missions and targets to gauge the effectiveness of their work, none of them have evaluated, or regularly evaluate, their own goal achievements or mid- or long-term effects. However, the organizations with professional management were in the process of gradually steering their activities and organizational measures toward a performance-oriented system. On the project level, all of the organizations were encouraged to choose indicators for the measurement of their targets. By using a logical framework approach, it was shown that the project objectives ranged from “have been achieved” to “have been very well achieved.” Nevertheless, recommendations for further improvement were made by the evaluator. Within the scope of the research project, only the foundations for effective action could be laid. Directed and unintended effects are to be measured “ex-post” in the long term.

Sustainability

The results suggested that some organizations had a good chance of running their businesses on a healthy resource basis in the long term. Provided that public funding is secured, these organizations have ample opportunities for resources and sponsorship, the organizational structures were stable, and the cultural topics reflected local needs. It was quite likely that the other organizations would achieve sustainable existence, which of course is uncertain due to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lessons learned and discussion

The arts are extremely significant modes of human interaction and expression, which should not only be organized from faraway places under purely commercial conditions. It is a healthy sign that the work of many artists is still embedded, in one way or another, in their local or regional surroundings.Footnote 33 Promoting cultural diversity at a regional level is a complex issue and a major challenge, which is certainly true owing to the complexity of the concept of diversity of cultural expressions itself. The 94-page UNESCO Operational Guidelines testify to this with the various criteria, indicators, and possible effects for consideration.Footnote 34 Thus, it is not surprising that each country is looking for its own way through the jungle of cultural diversity.Footnote 35 Additionally, the federal and subsidiary system of the Swiss government is a challenge when implementing international standards. The loose coupling between the federal state and the regional governments has led to transmission problems of regional services and effects at the federal level, from where impacts are reported to UNESCO. Due to its tripartite forms of self-governance with players from politics, civil society, and the economy,Footnote 36 there are limited possibilities of motivation, intervention, and control. Furthermore, in the consensual decision-making processes that are typical in Switzerland, especially those that are non-state processes, actors must also be convinced of the idea of the Convention on Cultural Diversity. In our experience, a complex concept such as the Convention requires considerable time for its norms to be diffused throughout the system.Footnote 37

Case studies, especially of an explorative character such as the present ones, are generally less objective and less quantifiable. For this reason, their representative meaningfulness is often questioned in terms of the robustness of the entire research strategy. In addition, case selection was provided by the client of the program evaluation, which could lead to systematic errors.Footnote 38 For further methodological development, relations between the criteria (configurations) as well as the causal mechanisms should be further examined. Moreover, the outcome of “diversity of cultural expressions” is not yet specified in this study—see, for example, the Stirling model as a mix of variety, balance, and disparityFootnote 39 —and should be measured in the case of a long-term evaluation. Nevertheless, these case studies, seen as preliminary or pilot studies, can provide valuable information for future practice in fostering cultural diversity as well as for program evaluation based on case study research.

Our research results indicate that existing cultural organizations are in fact able to mobilize all kinds of regional resources. Together with their partners, they are capable of developing regionally relevant projects. Cultural competence centers indeed collate knowledge and resources, and they serve as a platform for amateurs, professionals, volunteers, and cultural consumers. Through the promotion, reflection, and further development of regional characteristics, they create identification points for an original, authentic, and lively local cultural life. On the project level, many ways are shown in which cultural diversity could be promoted: events that take place outside the cultural organization open up new audiences; competitions of contemporary interpretations of folk music bring traditions to life and promote the development of new pieces of music; digital archives of cultural heritage create a new visibility for forgotten traditions; and the inclusion of the population in the development of performances creates identification and dedication to art.

Our study also shows that one major challenge with managing a local cultural competence center is the handling of vested interests. Although these networked structures testify to a high level of long-term commitment, they are at risk of excluding new and different impulses from within the region, thus preventing the sustainable development of contemporary cultural diversity. To break down these structures, the Convention on Cultural Diversity becomes necessary. With its principles such as “interculturality,” “freedom,” and “access to all,” the Convention promotes implementation concepts that foster an open-innovation culture along the whole arts production chain. The program evaluation has shown that these criteria must be imposed externally—for example, by public funding institutions—as the objectives of cultural diversity were not yet strategically implemented. If a cultural, regional competence center does not consistently adhere to the Convention on Cultural Diversity, a monopolization process is expected to take place, which will push other artists, cultural forms, and initiatives out of the regional market and thereby hinder inclusive regional identity processes. Furthermore, there is a risk that a homogenized, globalized, and commercialized culture would fill this gap.Footnote 40 The long-term effects of regional competence centers on the development of the diversity of cultural expressions remain open. For Central Switzerland, the present study defines the starting point (zero point) for a measurement of long-term effects being evident after five to ten years.

To serve as a role model, the findings of this evaluative research project are intended to be used in the development of a practical guide for decision makers in the Swiss arts sector when implementing the principles of the Convention on Cultural Diversity at a regional level and in arts organizations. This project emphasizes the participatory development of solutions together with the local actors. In this way, the community-based development of local cultural programs and their structures for civil society engagement have been strengthened. These aspects have not been into account sufficiently in the Convention on Cultural Diversity’s implementation and could create a balance to the “commercial logic”Footnote 41 and the legal protection of social rights mattersFootnote 42 in the current implementation recommendations.Footnote 43

The Convention on Cultural Diversity demands reporting duties, which are respected in practice by only half of the ratified states, and no sanction mechanisms exist. Therefore, the instruments to enforce the Convention are weak, but still, some effects already can be observed after a couple of years, mainly emphasizing the success of cultural products in the globalized digital markets and the capacity building of market-oriented mechanisms.Footnote 44 Take, for instance, Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink’s “Norm Life Cycle,” where norms are seen as “a standard of appropriate behavior for actors with a given identity” and are developed in a cycle where (1) norms emerge; (2) get widely accepted; and (3) are eventually internalized.Footnote 45 It is stated that the Convention on Cultural Diversity has “softened” the hard law of the WTO and has therefore found wide acceptance on the international level.Footnote 46 On the federal level of states, activities to implement cultural diversity policies have increased.Footnote 47 Now, through the multiple project activities of the states, of which one was presented in this article, the idea of a meaningful world of diverse cultural expressions has been gently introduced and has begun to be internalized by the citizens of the world.Footnote 48

Funding Statement

This project was financed and commissioned by the coordination body of the Zentralschweizer Kulturbeauftragten-Konferenz (KBKZ), in which the six cultural offices of Central Switzerland are represented, and the Swiss National Arts Foundation Pro Helvetia.