‘The theories which we accept at present have their roots in notions, which go back to the earliest ages’ (Arrhenius Reference Arrhenius1909, p. 260).

Introduction

The oldest attempts to solve the problem of the origin of life may be traced in various myths, religious beliefs and philosophical approaches. The development of pre-scientific and scientific knowledge led to the production of an abundance of hypotheses and theories, which are at times complementary or contrary to one another and which have been partially confirmed or even refuted by new scientific findings. Therefore, some explanations of the origin of life are merely of historical value nowadays. The development of the modern empirical search for the beginning of life dates back to the middle of the 20th centuryFootnote 1.

Generally speaking, the beginning of life on the Earth may be interpreted and explained in five main forms: (1) as the result of God's or some kind of supernatural creation act; (2) as the effect of the spontaneous and immediate process of transforming inanimate matter into an animate one (‘naive’ spontaneous generation); (3) as the effect of the physico-chemical evolution of matter taking place on the Earth (natural-scientific abiogenesis); (4) as the transference onto the Earth of life, which had previously arose on other celestial bodies or in cosmic places (panspermia); (5) lastly, there is the supposition that life is an eternal property of existence. This last thesis does not actually explain biogenesis, but rather refutes the nature of the question by asserting that life has no beginning at all.

Nowadays, the problem of the origin of life may be discussed from both a scientific and a philosophical perspective. The scientific approaches provide the basis for the philosophical analysis of the origins of life discussed in this paper. Nevertheless, the final scientific conclusions are always conditioned by the philosophical assumptions of the researchers and theorists working on this problem. The philosophical implications of these theories are worthy of detailed examination (on the subject of multiple relationships between philosophy and astrobiology: Chela-Flores Reference Chela-Flores2011, pp. 247–256).

The present scientific theories of the origin of life are developed on the basis of specialized biological, chemical, physical and astrophysical research results. Past attempts to explain the genesis of life were based on superficial casual observation (without the use of advanced scientific tools and research methods), so that may be classified as scientific explanations because they used the empirical method (i.e. observations) even though they did not use the more modern method of hypothesis testing. These theories bear witness to the complex historical development of the various explanations for the origins of life.

Biogenesis was presented as a hypothesis as early as 1897 when Richard Krzymowski (1875–1960) (Schröder-Lembke Reference Schröder-Lembke1982), a Polish emigrant's son living in the Swiss town Winterthur, published in the magazine ‘Die Natur’ his article entitled: ‘The essence of spontaneous generation’ (‘Das Wesen der Urzeugung’) (Krzymowski Reference Krzymowski1897). His conception of biogenesis was based on the idea of pre-biological natural selection and of early heterotrophy. Unfortunately, his article was largely forgotten; instead, scientists who presented similar conceptions almost a quarter of a century later, namely A. Oparin, J.B.S. Haldane, J. Alexander, C. Bridges, are considered the precursors of modern examinations of biogenesis. Nevertheless, in his last years Krzymowski was able to witness the emergence of the scientific discipline concerning the beginnings of life (protobiology) at the first international conference on this subject held in Moscow in 1957 (International Conference of the Origin of Life – ICOL). The amount of scientific scholarship dealing with this problem has been increasing since 1957. Between the 1957 and 2000, more than 150 theories of biogenesis were published; and recently the number has increased significantly (Ługowski Reference Ługowski2005, Reference Ługowski2008b, Reference Ługowski2010).

The multiplicity of old and new biogenesis theories merits some attempts at systematization. One reason is, of course, to bring some order among the various theories. But more importantly, such work might possibly produce some universal ‘key’ which could be useful for this purpose and independent from empirical research achievements. The proposal, I would like to present, assumes that philosophical premises play an important role in the construction of theories of the origin of lifeFootnote 2. Likewise, an examination of the philosophical implications of these theories, and the fact of identifying and describing them in an adequate way, may turn out to be essential as far as systematizing the multiplicity of scientific theories of the origin of life is concerned. I think that each of the theories in question is underlain by one of two main ideas, which have shaped both the past and the present views on the origin of life. These ideas are: (1) the idea of spontaneous generation and (2) the idea of panspermia. Both ideas evolved and underwent some essential transformations during centuries, but they both may also be traced in the modern natural-scientific proposals of solving the puzzle of life genesis. Therefore a ‘philosophical key’, which I propose, seems to be the most appropriate to systematize all kinds of theories on the origin of life. This paper offers a justification of this position.

Landscape of views on the origin of life: types of theories

The proposed classification of all conceptions of the origin of life is, first of all, conditioned historically, i.e. by the chronology of their emergence and by the approach towards the scientific results concerning the origin of life (‘vertical view’). The conceptions, which were proposed before the development of experimental method in its present sense and application to the question of the beginning of life (before the 1860s the origin of life was primarily of philosophical and religious interest and only exercised the minds of practicing scientists in an incidental manner) or which ignore the scientific findings completely, may be described as metaphysical onesFootnote 3. The conceptions, which arose within the modern and current natural science (as it was mentioned, Oparin's theory, with its strong roots in biochemistry, laid the foundations for modern approaches to the question, including some of the experimental approaches that have characterized research since the 1950s; cf. Kamminga Reference Kamminga1988, pp. 7–9), I propose categorizing as ‘scientific’. However, I assume that neither of them is completely free from the specific philosophical assumptions and pre-assumptions as well as from philosophical implications following from them. In other words, we may distinguish in these conceptions the scientific (empirical) level, which is usually the fundamental content of the conception and the philosophical level, containing the consciously or unconsciously adopted propositionsFootnote 4. This premise, of the indissolvable marriage of philosophy and science is evident from a detailed analysis of content of particular contemporary theories on the origin of life. This is a typical situation for science because empirical data (usually in the form of quantitative values) require adopting a theory for interpretation. In turn, a theory contains a series of assumptions. For example, underlying the theory of the self-organization of proteins (Kauffman Reference Kauffman1993) is the explicit philosophical belief that self-organization should be regarded as a natural, original ownership of complex systems and considered at least as important a source of order in the animate nature as natural selection. ‘I've always wanted the order one finds in the world not to be particular, peculiar, odd or contrived – I want it to be, in the mathematical sense, generic. Typical. Natural. Fundamental. Inevitable. Godlike. That's it. It's God's heart, not his twiddling fingers, that I've always in some sense wanted to see’ (Levy Reference Levy1993, p. 128). In turn, in the theory of comet pond (Clark Reference Clark1988) implies that life could have arisen as a result of a sequence of events unlikely (‘an extremely-low-probability sequence of events’) and is sufficient because it would only take a single comet carrying relevant biochemicals to bring about the development of life on Earth. Furthermore, metaphysical explanations as to the origins of life still hold purchase in contemporary society: Schools in Texas still teach creationism in their educational curricula and we can find the supporters of the creationist vision of the beginning of life (for example, in modern version as ‘Rational Design Hypothesis’; Shiller Reference Shiller2004).

Another important distinction between all the conceptions of life genesis is the scope of their theories: do they seek to answer the question of the origin of life on the Earth? or the origin of life in the Universe (‘horizontal view’)? The two questions may either be treated separately, or we may assume that the beginning of life on the Earth is the beginning of life in the Universe (in the latter case, we have another philosophical assumption). Both fundamental distinctions of the conceptions of the origin of life mentioned above, after overlapping them, outline the general areas, in which particular types of conceptions of biogenesis may be situated.

Thus, we have: (1) the area of metaphysical conceptions explaining the emergence of life on Earth (M-E); (2) the area of metaphysical conceptions explaining the origin of life in the Universe (M-U); (3) the area of scientific theories explaining the emergence of life on Earth (S-E); (4) the area of scientific theories explaining the origin of life in the Universe (S-U). The above distinctions are not mutually exclusive and, thus, allow for interrelations between the distinguished areas and between the types of theories of the origin of life situated within them (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Types of theories.

We should begin our discussion with the metaphysical conceptions, as they are the earliest in the history of human thought. This group contains: (1) the conception of life pre-existent in conjunction with the idea of panspermia (old version); (2) the conception of creation of life on Earth; (3) earthly spontaneous generation – within the area of conceptions concerning the beginning of life on Earth; and (1) the conception of age-long character of life; (2) the conception of creation of life (in the Universe); (3) cosmic spontaneous generation – within the area of conceptions concerning the origin of life in the UniverseFootnote 5. Historically, primitively knowledge of inanimate and animate matter, and its beginning was limited to the simple observation of facts placed in observed nature. Then was added reflection of thoughts, according to the progress of scientific knowledge about observed facts, which needed interpretation. Mentioned concepts are of metaphysical type, because their central part is a metaphysical idea of spontaneous generation of animate matter from inanimate one or belief in the existence of eternal life, which is as old as the entire material reality. We should note, at this point, that the conception of creation of life may be the explanation of its existence both in the Universe and merely on the Earth, depending on the place, to which the act of creation is attributed. Moreover, we have to differentiate between two forms of creation, in accordance with traditional theological approaches, into direct and indirect creation. This distinction is important for outlining the possibility of negotiating the fundamental propositions of metaphysical conception with the scientific conceptions (and will be discussed it in greater detail later)Footnote 6.

The scientific conceptions may also be divided into those concerning the emergence of life on the Earth and those, which concern the origin of life in the Universe. Chronologically speaking, we may distinguish the following within the former group of conceptions: (1) the natural-scientific earthly abiogenesisFootnote 7; (2) the natural-scientific bilinear abiogenesisFootnote 8; (3) the pre-existence of life in conjunction with neopanspermiaFootnote 9. Within the area concerning the origin of life in the Universe, we may situate cosmic abiogenesis.

The primary spontaneous generation (also called ‘naive’) comes from ancient times, mainly from Aristotle's views; it contains the conviction that the specific (sometimes even quite complex like fishes, frogs or insects) living organisms may emerge suddenly and spontaneously in the favorable environment circumstances. This view was maintained for centuries because, as late as the 19th century, some micro-organisms were thought to be able to emerge in this way. Depending on the place, to which we attribute the spontaneous generation, we may distinguish the earthly spontaneous generation and the one, which took place within the Universe, i.e. the cosmic (extraterrestrial spontaneous generation). ‘Naive’, spontaneous generation is – most generally speaking – a view, according to which living creatures come into being spontaneously and voluntarily from inanimate matter. It should be noted that such a broad formulation of the idea of spontaneous generation, however, does not show significant differences that occur in understanding it. The basis for these differences is constituted by different definitions of what should be considered inanimate matter, and what – animate matter. A thorough consideration of the arguments that have been offered in the history of research into the nature in order to justify the idea of spontaneous generation, and an investigation into the modern debates and controversies concerning this idea allow discovering a variety of interpretations of the view of a spontaneous and voluntary origin of biological organisms. The variety was formed together with the development of the scientific empirical method and with the participation of philosophical concepts explaining the way the animate world functions. With time, the idea of a spontaneous origin of organisms underwent many transformations, first consisting in limiting the range of its application (from macroscopic organisms with complex structure to relatively simple microorganisms), then in a change in its understanding, and finally to questioning the very idea. Also the way changed, in which the possibility of the occurrence of spontaneous generation in the nature was motivated. However, it seems that the very core of this idea, which contains a general thought about transformation of matter leading to the origin of living organisms, is still maintained in the contemporary natural science.

Abiogenesis is the term sometimes used as a synonym for spontaneous generation; that is, abiogenesis means life coming from nonliving matter. Similar terms have been used to refer to spontaneous generation of life at the submicroscopic level, such as neobiogenesis, biopoiesis and eobiogenesis. Using different names for spontaneous generation just adds to the confusion, not to the understanding. Biogenesis rather means life coming from living matter. In contrast to spontaneous generation, the law of biogenesis is a thoroughly documented law of biology (cf. Sagan Reference Sagan1974; Moore Reference Moore1976, p. 65). The natural-scientific abiogenesis, in turn, is the collection of numerous particular protobiological theories – the proposition on the gradual, process way of the emergence of life in the Universe, being realized through the gradual and complex physico-chemical transformations – is common for all of themFootnote 10. Depending on where the particular stages of this process take place, we may talk about the earthly, cosmic or bilinear abiogenesis (as far as bilinear abiogenesis is concerned, its initial stages are thought to take place also in the cosmic space, but ultimately the life emerged on the Earth). Therefore, they differ in their natural-scientific level, particularly in the place of the process of the emergence of life, while the same philosophical element may occur in each of them. That is why, taking into account the content of particular theories of the origin of life, we may distinguish three fundamental types of philosophical level underlying the natural-scientific views (the implications from them), hence, it is possible to propose three variants of abiogenesis theory: (1) meta-information abiogenesis – the theories, which refer to some form of universal integration principle, i.e. to ‘the design’, ‘the eternal order’, the law governing the course of all the processes within the UniverseFootnote 11 or the theories assuming the eternal existence of biological informationFootnote 12; (2) mechanistic-chance (eventist) abiogenesis – the theories based on the assumption of the chance emergence of the first living thing, because of the lucky coincidence of natural circumstances and physico-chemical regularities favourable for the emergence of lifeFootnote 13; (3) abiogenesis as a self-organization of matter – theories, which adopt the evolutional way of understanding the emergence of qualitatively new systems and which point to regularities governing the process of their development, among which the crucial element is the natural tendency of matter to organize itself into more and more complex structuresFootnote 14. All three types of abiogenesis theories may be further differentiated, but this falls beyond the scope of the present paper (Ługowski Reference Ługowski2008a; Schwartz Reference Schwartz2009). Placed in an historical context abiogenesis may be understood as the development and transformation of the idea of ‘naive’ spontaneous generation, because there still present the basic idea of the transformation of inanimate matter to animate one.

What concerns the mode of explanations of the transition non-life into life in the current theories of the origin of life a great variety of solution have been observed: chance information of the first information-carrying molecule; chance formation of the first autocatalytic loop; physico–chemical interactions; mineral prescription; the universal law of integration; self-organization explained in physico-chemical terms; biochemical self-organization; environmental self-organization spin-glass formalism; broken symmetry and the abiogenesis as a cosmos-earth joint venture. The differences between the theories, however, as well as current controversies in the scientific community (RNA-world first, thioester world first, inorganic pyrophosphate first, proteinoid first, primitive metabolism first, thermosythesis first, etc.) were shown to be dependent of several much more profound methodological and ontological assumptions underlying the origin of life studies.

The last of the four groups of the origin of life theories, i.e. the pre-existence of life in conjunction with neopanspermia, also dates back to ancient times, but its contemporary versions not only assume that life may move through the Universe at some specific historical moment, but also reached, the Earth, in its very simple form where it found the circumstances favorable for its development. Recent research focuses on the specific circumstances and mechanisms responsible for the wandering of life throughout the universe (Seckbach et al. Reference Seckbach, Chela-Flores, Owen and Raulin2004; Schulze-Makuch & Irwin Reference Schulze-Makuch and Irwin2006; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Hicks, Chyba and McKay2006). The last years brought some direct evidence that the process of chemical evolution in the molecules of cosmic dust contained in the nuclei of comets reached already quite advanced stages. Inorganic fraction of cometary dust contains the catalysts suitable for creating from the organic substances in connection with water all the required precursors of the molecules of proteins and nucleic acids. Moreover, the dust particles, due to their porosity, create the natural compartments for the evolving molecules of organic substances, replacing in this way the protocellular membrane. What is lacking in the planetary line of prebiological evolution is the molecule of proto-RNA relatively separated from the environment. Exactly this may be offered by the cometary ‘male’ line of prebiotic evolution. A bilinear scenario of the origin of life resulting from the combination of characteristics of both lines of chemical evolution, divergent from physical and complementary from biological point of view, is satisfactory when thermodynamics is concerned, whereas no other formerly presented monolinear conceptions could fulfil this requirement. According to this conception for the transition from simple organic substances to primitive cells very short time is required, which correspond with the lately accumulated paleobiochemical evidence in favour of the ‘geological eternity of life’. This is the first substantial conception of prebiological evolution referring to the direct empiric evidences. Probably we will never get any samples of the primary terrestrial atmosphere or of the primary ocean, none the less we have results of direct analysis of the inorganic and organic fractions of cometary dust. The last circumstances may not be so important from philosophical point of view as the former, but it will probably have considerable value for the scientists.

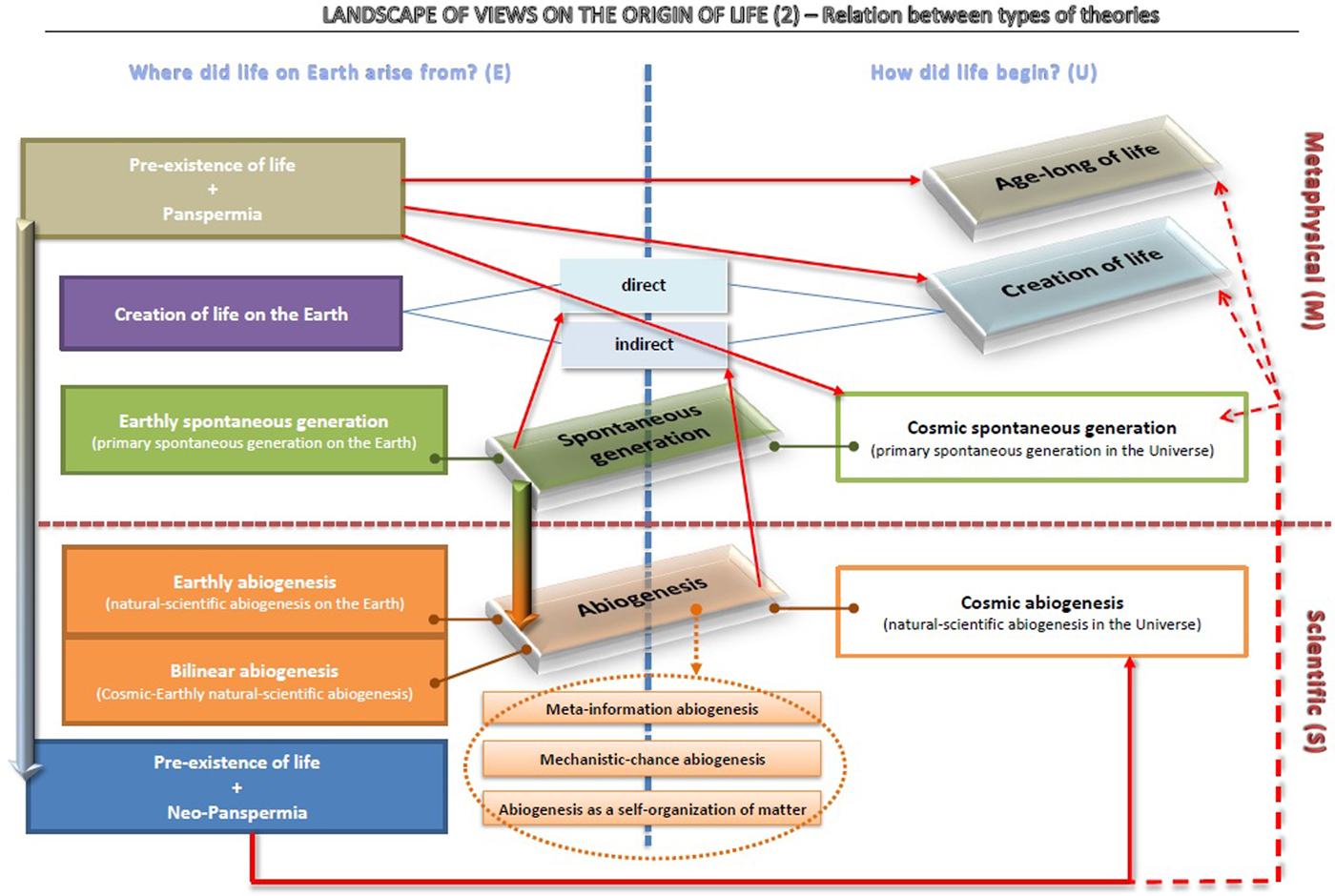

Landscape of views on the origin of life: relations between types of theories

The scheme outlined by the proposed classification of the types theories explaining the origin of life acquires additional importance when we consider interrelations between particular types of conceptions. These interrelations exist not only between particular types of conceptions within one of the areas mentioned (metaphysical or scientific) and between the types of conceptions concerning the problem of the emergence of life on the Earth and in the Universe (respectively: M ↔ S; E ↔ U – ‘vertical’; ‘horizontal’), but also between the conceptions coming from different areas (M ↔ E; M ↔ U; S ↔ E; S ↔ U – ‘vertical-horizontal’). All these interrelations allow us to witness not only the historical development of human thought on the origin of life but also the interrelations existing between various modes of thinking about the emergence of life (metaphysical, scientific, philosophical-scientific) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Relation between types of theories.

When examining the interrelations just mentioned, we may note that:

(1) Adopting the metaphysical conception of pre-existence of life leads towards accepting either its age-long character or its creation by a supernatural force (outside the Earth) or cosmic spontaneous generation; such a solution, in turn, forces us to introduce the conception of panspermia (nowadays, neopanspermia) as the way of reaching the Earth by the existing/created/generated life.

(2) Adopting the conception of creation, as far as the origin of life on the Earth is concerned, is equivalent to adopting a conception of creation as a whole, and the act of creation may be direct or indirect one. This second version of creation is possible to complementary reconciliation on the basis of philosophy with the theory of abiogenesis, because indirect act of creation can be understood as the hidden mediation of supernatural action in the processes of nature and by the nature.

(3) The pre-existence of life in conjunction with neopanspermia requires referring also to the cosmic version of abiogenesis; yet, we may refer to the explanations, which are strictly metaphysical in character: i.e. to the creation or to the age-long character of life or to the cosmic version of spontaneous generation.

(4) Panspermia is being continued nowadays in the form of contemporary natural-scientific neopanspermia and can be consistent both with the scientific theory of abiogenesis and with the metaphysical ones. Thus transformed idea of panspermia (neopanspermia) is still useful and helpful for the proponents of cosmic abiogenesis.

(5) Nowadays, the idea of spontaneous generation finds its continuation in the natural-scientific abiogenesis theories, occurring in the form of earthly, cosmic and bilinear abiogenesis; this relationship is indicated by the presence of the fundamental proposition on the transformation of the inanimate matter into the animate one within abiogenesis theories. Differences lie in the way the mechanism of this transformation is explained (cf. Farley Reference Farley1977; Harris Reference Harris2002). Nowadays explanation of the mechanism and course of this transformation is the task for protobiology and its abiogenetic theories.

(6) The direct creation of life might complement the idea of spontaneous generation as a sudden and spontaneous transformation of the inanimate matter into the animate one. The direct creation intervention of God may be responsible for this transformation, as God makes the inanimate matter into the animate one.

(7) The indirect creation of life may complement theories of abiogenesis, because the latter indicates the complex physico-chemical process leading towards the emergence of life, which, from the viewpoint of understanding creation, may be seen as an indirect creation act. The intermediate elements can be understood as physico-chemical transformations, which take place in coexistence with the Creator's will and involvement.

(8) All three variants of natural-scientific abiogenesis (the meta-information abiogenesis, the mechanistic-chance abiogenesis and abiogenesis understood as the self-organization of matter) may function within each of the types of abiogenesis (the earthly, cosmic and bilinear one) and they may be combined through the idea of panspermia (in the version of neopanspermia) in the case of cosmic abiogenesis.

Presented above relations demonstrate that there are two fundamental trends in the thinking and the searching for the origins of life: earthly beginnings of life and the cosmic origins of life. In addition, we can see that the acceptance of particular solution at the scientific level generates questions of a philosophical nature: what is the essence of these processes that on the plane of natural regularity enabled the formation of life.

In the presence of a number of competing theories of the origin of life a ‘philosophical key’ to systematize them referring to their philosophical assumptions and premises seems to be more useful and versatile than sorting them by e.g. due to the place of origin of life or the specific scenarios for its beginning.

Recapitulation

We may draw the following conclusions from the proposed systematization of the types of the beginning of life conceptions as well as from the interrelations between them:

(1) The contemporary theories of the origin of life, regardless of the specific empirical-scientific solution of the main problem, which they propose, contain in their extra-scientific (philosophical) level the continuation of either of the two fundamental ideas concerning the origin of life, i.e. the spontaneous generation (nowadays in the form of natural-scientific abiogenesis theory) and/or panspermia (nowadays, in the form of neopanspermia theory). This is evident when we analyze assumptions present in these theories and used methodology. The strategies adopted to seek solutions are often dictated by existing problems with which existing theories cannot handle. A similar situation occurred in the 19th century, when the fall of spontaneous generation by Pasteur's experiments resulted in the necessity to seek a way of other explanations of the origins of life, and recalled then, among others, to the concept of panspermia. Currently visible is to draw in the bilinear theories of the origin of life.

(2) Metaphysical conception of indirect creation can be consistent with the philosophical level of each of the three contemporary variants of abiogenesis conception as well as with neopanspermia, whereas this is not the case with the conception of the age-long character of life. This makes it possible to seek complementarity between theological and scientific image of the origin of life.

(3) The philosophical level (philosophical basis) is irreducibly present in each theory of the origin of life, if it is a theory and not just a loose collection of scientific findings and results. At the root of the abiogenesis theories there are three basic premises: (1) the possibility of primary formation of the organic compounds; (2) the possibility of further evolution of these compounds; (3) immutability fundamental laws of nature over time. Thus we can also say about philosophy of the origin of life. The general situation in the philosophy of the origin of life is similar to that in protobiology itself: there is no theory of the origin of life without problems. The same statements can be made about the philosophy of protobiology: none has a monopoly on truth in this game. To be able to recognize the ‘duality’ of particular theory on the origin of life, it is necessary to understand its double philosophical/scientific genealogy.

(4) The presence of the empirical level and the philosophical level within the contemporary natural-scientific theories of the origin of life requires, on the one hand, making the clear distinction between them (because of their methodological diversity) but on the other hand, requires the consciousness of their interrelations and conditions, which are of a great significance for the ultimate and comprehensive solutions of the problem of life's beginningsFootnote 15.

(5) The philosophical basis or implication, which is always present in theories of the origin of life, indicates that this problem is not just the strictly scientific one; it is a philosophical problem, too; thus it cannot be fully solved merely through referring to the empirical aspect of biogenesisFootnote 16. In philosophical perspective remains question, how to explain the fact of life. The main problem of biogenesis in philosophical aspect becomes the answer to the question whether indicated by science material elements and mechanisms of the natural gradual changes could cause the emergence of life as a new quality in nature, irreducible to it antecedents. At this point, it becomes possible different answers, referring to the accidental (chance) formation of life, the specific form of the creation of matter, or initial equipment the matter with the ability to self-organization.

Conclusions

What makes protobiology attractive from philosophical point of view is its deep internal tension, caused by the duality of its philosophical roots. Protobiology is born both from the spirit of the Hegelian and Comte'an metaphysics. And in spite of several declarations of scientists that it is possible and needed to be free of metaphysics the question is not how to reject one of them, but should instead be how to be conscious of both. Only by keeping in mind such a double philosophical genealogy of the origins of life studies it is possible to avoid several paradoxes: order without order, information without information, beginning without beginning, commonly claimed to be inherent to all theories and to overcome some stereotypes, like e.g. on the crisis of the chemical evolution of life theory caused by the discovery of geological eternity of life.

The question of philosophical basis for the origin of life theories and discussions on philosophical implications show that the view, according to which the ‘mature’ science may (and should) be free from philosophical conditions, the view promulgated seriously by the professional philosophers of positivist orientation, still finds its supporters among the researchers themselves. The very act of initiating the scientific research of biogenesis constituted the philosophical turning point in two fundamental aspects. In its ontological aspect, it required resignation from an understanding matter as a passive substance. In its methodological and epistemological aspect, it meant a shift from the scientific patterns connected with classical physics and a move towards the patterns proposed by evolutional biology. The ontological foundation of contemporary research on biogenesis is the attitude known as processual holism (Ługowski Reference Ługowski2010, pp. 170–171ff). The essence of processual holism consists of: (1) autodynamism, i.e. the conception of active matter; (2) holism, i.e. an interpretation of nature as a system with interrelated elements affecting one another; (3) historicism, i.e. the fully historical approach towards the evolutional process that takes into account the variability of the elements and mechanisms of evolutionFootnote 17.

Theories remain theories but the significance of the changes that have taken place in the evolution of scientific knowledge should not be undermined. Natural scientists themselves, (at least those with the best philosophical awareness, such as Ch. de Duve, S.A. Kauffman) express the essence of processual holism in the following formula: life is the natural emergent property of the matter. The assumption that life emerged from matter based on physical mechanisms of self-organization is not a ‘passive ingredient’ of all these theories. Understanding this formula is important for anyone who seeks to comprehend the place of living creatures (and his own) within the process of universal evolution. This is also essential from the viewpoint of science development. Unfortunately, not all scientists realize it. There are also those, who consciously and deliberately construct the biogenesis theory on the basis of opposite assumptions (a chance, a meta-information, a design – for instance: J. Monod, E. Mayr, F. Crick; Fry Reference Fry1995, p. 391ff).

Not all the debatable issues and differences, as far as the origin of life is concerned, should be treated as equally important, in the sense that this or that solution may affect further course of the research upon biogenesis. For instance, the dispute over the place of the emergence of life (and there is a wide range of proposals here: from the grains of cosmic dust, through atmospheric aerosols and clay minerals, up to hydrothermal vent under the bottom of the sea) does not necessarily lead towards the selection one option and elimination of all others. Such controversies should be described as inessential. However, it seems important whether the researchers will be willing to accept in a conscious manner the fundamental premise of the research on biogenesis, i.e. the claim for the ability of matter to organize itself (self-organization) or maybe, negating their research practice, they will accept the following maxim: ‘Protobiology is a science, which entirely dispenses with philosophy’ (implicitly: ‘other than that of mine’).

Acknowledgements

I thank editor David Dunér and the anonymous referees for many helpful comments.