Western Christianity had expanded through waves of missions to China since the early seventh century. The first missionary presence was attested by the existence of Nestorians in Chang'an during the early Tang dynasty, and the second propagation developed during the Yuan empire.Footnote 1 However, the previous two waves disappeared soon after the fall of the respective dynasties. Only the third one gained some footing in the Ming China empire through the relentless efforts of the Catholic missionaries during the sixteenth century. In relation to this background, the Augustinians sent by the Society of Jesus (better known as the Jesuit order)Footnote 2 contributed to the early reception of Christianity in Late Imperial China. Among these theologians, Francis Xavier (1506–1552) was the proto-China Jesuit and perhaps one of the most important Spanish pioneers in Asia. He sailed to Japan, landing in Kagoshima on the island of Kyushu and later travelled to Kyoto, to make Japanese converts to Christianity.Footnote 3 It is a pity that Xavier fell sick and died on Sancian 上川 island (only fourteen kilometers from the mainland) in December 1552, leaving a missionary dream for China that would only be fulfilled by later Jesuits, Michele Ruggieri (1543–1607) and Matteo Ricci (1552–1610), who viewed Xavier's effort through a largely hagiographic lens. After these pioneers, more Jesuit missionary followers, such as Alphonse Vagnoni (1566–1640) and Giulio Aleni (1582–1649), and subsequently, much later, the Protestant missionaries Robert Morrison (1782–1834) and William Muirhead (1822–1900), settled in China, introducing Augustine to Chinese Christians and translating his writings.Footnote 4 However, the early Jesuit introduction of Augustine has sparked controversies among modern scholars. Some critics note that there are many inaccurate formulations in these missionaries’ introduction of Augustine. On the other hand, other scholars are of the opinion that these inaccuracies are actually not misrepresentations, but rather follow the method of “cultural accommodation” or “adaptation” developed by Alessandro Valignano SJ (1539–1606) and Matteo Ricci.Footnote 5 I shall first explain this controversy and the competing positions.

Controversies on the Early Chinese Biography of Augustine

Zhou Weichi, a famous Chinese Augustinian scholar of modern times, argues that the Jesuits contributed the earliest introduction of Augustine to a Chinese audience, but their translations include a number of inaccuracies and even misrepresentations, which misled Chinese congregations in certain ways.Footnote 6 In a recent article in Chinese (“A Chinese Biography of Augustine in Ming and Qing China”),Footnote 7 Zhou finds that some legends about Augustine, such as the anecdotes of “St. Augustine and the Seashell” and “Augustine's conversion in Milan,” were the earliest records of the story of Augustine circulating in China and that his biography, Confessions, was also translated into Chinese by later Jesuit followers.Footnote 8 However, these introductions and translations by the early missionaries in Ming and Qing China, Zhou argues, contain obvious flaws. I shall address his comments in the following.

First, the introduction of anecdotes about Augustine by the early Jesuits was often too simple and ambiguous, so that Chinese readers might not even know who this person “Augustine” was. For example, in Tianzhu shengjiao shilu 天主聖教實錄 (The True Account of God), Michele Ruggieri 羅明堅 adopts an ambiguous term “an ancient Saint” without referring to “Augustine” by name.Footnote 9 In his Child Education 童幼教育, Alphonse Vagnoni 高一志 simply asserts that “one day, in reading some of the works written by Paul and the Apostles, he was suddenly enlightened and soon converted from heretical teachings to the divine knowledge”Footnote 10 to refer to the occasion of Augustine's conversion in Milan. Like Alphonse Vagnoni, Giulio Aleni 艾儒略 interprets this event in a similar way, “he [Augustine] became conscious of the empty nature of the world and thereafter converted to the monastic life.”Footnote 11 Zhou Weichi comments that these cases of paraphrasing by the early Jesuits caused unnecessary ambiguities for their Chinese audience in identifying “Augustine”; these ambiguous expressions also indicate an obvious attempt to block the congregation's access to the intellectual world of Augustine.Footnote 12

Second, the translation of Augustine's biography by these Jesuits involves a number of errors. For example, the Italian Jesuit Giovanni Andrea Lobelli's (1610–1683) account in which “after reading the works of St. Athanasius, Augustine converted to Christianity and was baptized as a Saint.”Footnote 13 Zhou Weichi points out that Augustine's knowledge of St Antony (ca. 250–350) came from the Latin translation by Evagrius of Antioch, rather than reading Athanasius's Greek work, Life of Antony.Footnote 14 In addition, Alphonse Vagnoni wrote the first Chinese biography entitled Sheng Aowusiding shengren xingshi 聖奧吾思定聖人行實 (The Life of Augustine), which was published in 1629 in Hangzhou. This biography includes 1,900 Chinese characters.Footnote 15 Zhou Weichi comments that errors are evident in Vagnoni's paraphrased text, for example, he states inaccurately that Augustine was the only son of his familyFootnote 16 and that he was baptized on the second day after the garden conversion in Milan.Footnote 17

Last but not least, the translations of Augustine's biography include many misguided formulations – take Young John Allen's compilation “Augustine” (ca. 25,000 characters)Footnote 18 as an example, one that is regarded as the longest Chinese-language translation of Augustine in the Late Qing dynasty. An obvious feature of Allen's translation of the Confessions is that he addresses the issue of how Augustine was set free from the bondage of pagan worship and converted to Christian belief. Zhou Weichi points out that Allen adopts the case of Augustine to persuade some Buddhist believers (Allen refers to them as idolators) to convert to Christianity, but Allen misrepresents the Roman empire as having a serious problem in its preoccupation with “Buddhism.”Footnote 19 A similarly arbitrary translation can also be found in Timothy Richard's Biography of Augustine (1901).Footnote 20

Based on the above analysis, Zhou Weichi argues that while early Catholic missionaries contributed to the propagation of the story of Augustine in China, a number of misrepresentations in their texts reveal arbitrary translations that detract from the historical “facts” of Augustine's life in the Western narratives, thus causing considerable difficulties for Chinese readers in their understanding of Augustine. In other words, the early reception of Augustine in the Chinese context, through the lens of an abridged and inaccurate interpretation, presents a selective, fragmentary and even misguided character in their approach.

Some critics, however, refer to other sources to demonstrate that these inaccurate formulations are not misrepresentations, but instead convenient reworkings as a result of “indigenization” or “accommodation.” Nicolas Standaert, R. Po-chia Hsia, Audrey Seah and the Japanese scholar Sumiko Yamamoto emphasize this feature by foregrounding the strategy of the translations as an approach to “indigenization.” In the Handbook of Christianity in China, Nicolas Standaert argues that the early Augustinians followed the accommodation method in relation to both the external aspects and the inner values of the Confucian elite culture.Footnote 21 According to Standaert, the Jesuits attempted to achieve the acceptance of Christianity by the Chinese-Confucian literati with a strong missiological intention, so they had to examine the features of the traditional Chinese faith first, such as Confucian ancestor worship. Within the tradition of Confucian worship, Matteo Ricci and his followers considered their rites of worship as licit. “The reason why these [Confucian] rites were morally admissible was that they were isolated in their individual entity from surrounding superstitions,” therefore, “Ricci and most of his successors redefined these [Confucian] rituals not as idolatrous or religious but as ‘civil’ and ‘political’ and thus acceptable for the Church.”Footnote 22 Under these conditions, the accommodation method might be applicable. An important aspect, Nicolas Standaert argues, is the problem of language:

An important aspect of the accommodation method was the use of native languages, to which was related the question of the words to be used for key-theological terms. The controversy about whether to choose, like in Japan, a Latin transliteration or a Chinese term lasted within the Society of Jesus until the early 1630s and ended with the decision to use Chinese names. The acceptance of the terms tian and shangdi for the Christian God was based on an interpretation of the Chinese Classics as containing a relatively pure monotheism. Most members of the mendicant orders, who arrived later in China, agreed on the general policy of accommodation by insisting on the knowledge of Chinese language.Footnote 23

According to the language accommodation strategy, it does not seem difficult to understand why Michele Ruggieri, Matteo Ricci, and later Jesuits adopted traditional Chinese terms from the Classics for key theological terms, as in the case of talking about the story of Augustine. Standaert argues that the accommodation policy to which early Augustinian missionaries adhered, however, was subjected to great challenges by a new generation of Jesuits who criticized Ricci's approach of adapting to Confucianism and Chinese rites. The result of the abandonment of such an “accommodation” policy, accordingly, was the so-called Chinese Rites Controversy, during which the Catholic mission experienced irreparable setbacks during the Kangxi 康熙 emperor period (1662–1722).Footnote 24 Standaert thus concludes that if we say that the method of “accommodation” or “adaptation” is a “thesis,” the attitude of rejecting the Confucian worship rites and the relevant terms could be described as an “anti-thesis,” so that a conflict between “thesis” and “anti-thesis” runs through the early reception of [Augustinian] Christian theology in history as a constant feature.Footnote 25

In line with Nicolas Standaert, other international scholars such as Po-chia Hsia, Audrey Seah and Lars Peter Laamann share the view that accommodation plays a significant role in the early reception of Christianity in China through the efforts of the Augustinians. In sketching an outline of the early Catholic missionary history in China, Po-chia Hsia argues that “any dialogue between cultures could only bear fruits on the basis of equality and mutual respect; thus, the Jesuit missionaries would first need to immerse themselves in the Chinese language, literature, history, and civilization before they could attempt to convert the Chinese.”Footnote 26 Po-chia Hsia notes that Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci employed Chinese Buddhist and Confucian terms in their own Chinese language works, although there is an obvious difference between them (that is, Ruggieri accommodated to Buddhism, while Ricci espoused a Confucian-Christian alliance against Buddhism).Footnote 27 Audrey Seah emphasizes further that even Matteo Ricci adopted the role of a Buddhist monk and lived in a Buddhist temple Xian Hua Si 賢華寺 (“Temple of the Flower of the Saints”; this ambiguous identity worked to the Jesuit's advantage).Footnote 28 Lars P. Laamann adds that the accommodation method that Ruggieri and Ricci employed was adopted from the Jesuit experience in India and Japan. They put the method into practice for the conversion of the Chinese, especially leading scholar-officials and members of the imperial clan.Footnote 29 Therefore, using native religious sources such as Buddhist and Confucian terms to convey Augustinian teachings became an important approach to converting the Chinese to Christianity through the efforts of the early Jesuits.

A renowned Japanese scholar, Sumiko Yamamoto, who devoted many years to the study of the history of Christianity in China, explains further the “accommodation” strategy in her work History of Protestantism in China: The Indigenization of Christianity (2000).Footnote 30 According to Yamamoto, ethnicity and embeddedness comprise the basic elements of “indigenization.” For the first element of ethnicity, the basic truth of Christianity does not change according to the time, region or ethnic group, though this is not to say that the forms which the understanding and practice of the teachings took could not be changed, as the universal truth takes concrete form.Footnote 31 In the case of the propagation of Augustine's theology, when it entered the Chinese context, preaching could be carried out in various ways so that the basic teachings would be within reach of the congregations. For the second element of embeddedness, Yamamoto explains that this can be understood as “putting down roots.”Footnote 32 This means that Christianity became deeply embedded in Chinese soil and was thus reborn and nurtured. Yamamoto notes that China had developed sophisticated systems of religion such as Buddhism and Confucianism before the coming of the early Jesuit missionaries. How should native Chinese believers abandon their former lifestyles and accept the new Augustinian system of thought and belief? Yamamoto explains that a foreign religion could become closely attached to the hearts, lifestyles, and organization of its adherents, thus assuming an indispensable existence for them,Footnote 33 as in the case of Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci adopting the external costume of Buddhism or Confucianism in order to become embedded within the indigenous culture.

Concerning the debate over whether the Jesuits misrepresented the message of Augustine in the propagation of Christianity in China, it seems that both positions offer correct insights, but they do not explore the underlying reason for the Jesuits’ preference for a writing style which combined Augustine's story with indigenous religions, nor as to why Augustine was taken as an example for Confucian intellectuals. Keeping in mind this dispute, let us turn to some early Chinese documents to examine the contextualization of Catholic theology in its encounters with traditional Chinese religious values.

The Early Chinese Manuscripts of Augustine and the Strategy of the “Confucian–Christian Synthesis”

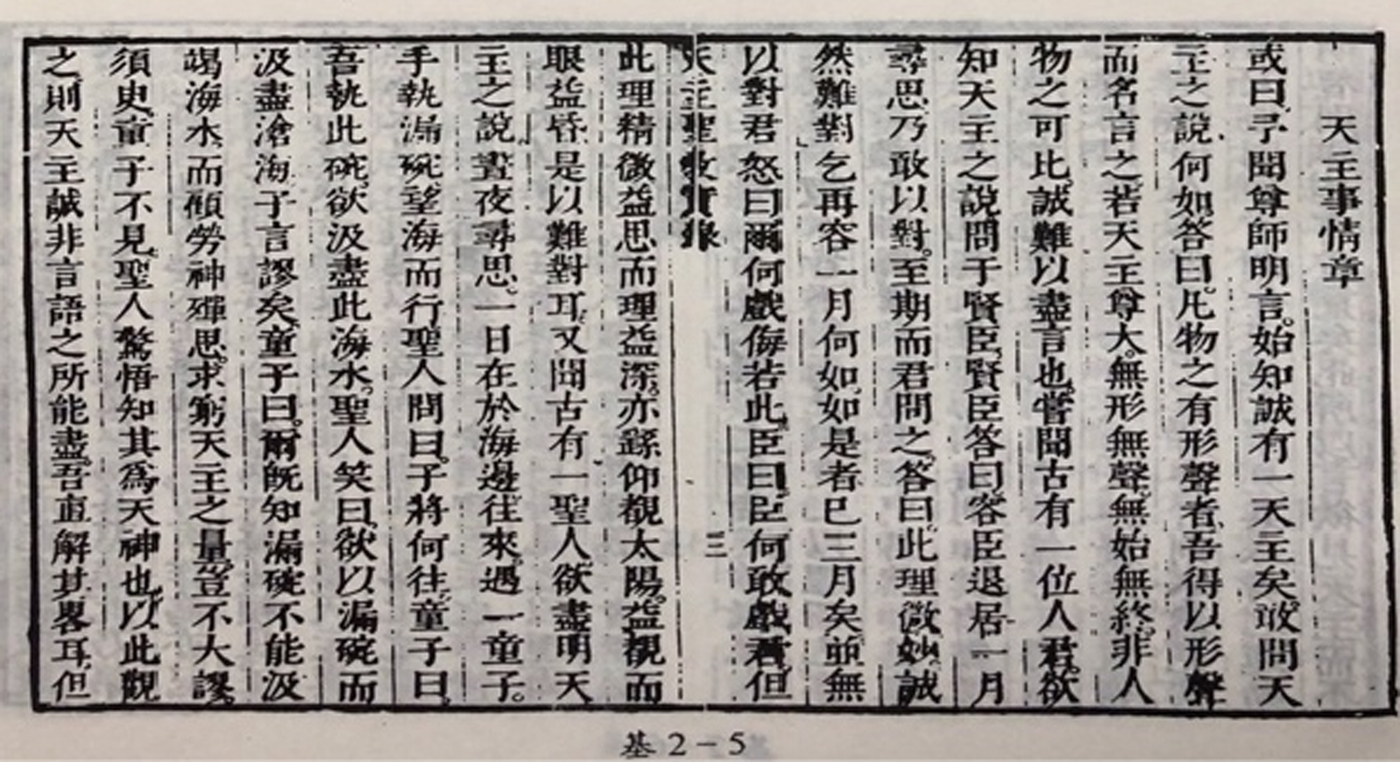

On a recent visit to China's most renowned theological institution, the Nanjing Union Theological Seminary, I found a few manuscripts in the library pertaining to Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci's early preaching of Augustine.Footnote 34 Taking Ruggieri's account of the story of “Augustine and the Trinity” as an example, let us look at the background from which Ruggieri introduces Augustine to Chinese readers. The story begins with a dialogue:

Someone asked me, “I heard from the master that there is a God, the Lord. May I ask what is the teaching of the Lord?” I [Ruggieri] answered, “If things have substances or sounds I might have names to call them by, but the Lord is honorable, no figures nor sounds, no beginnings nor endings, which cannot be matched by common people, so that it is difficult to define. I heard that there was an emperor who wanted to know the teachings of the Lord and he asked the minister. The minister replied, ‘Please forgive me while I meditate for a month’… After three months, the minister still had no words with which to answer him. The emperor became angry, ‘How can you tease me like this?!’ The minister answered, ‘How can I tease you, your Majesty? Only because the Truth (Li) is so delicate, thinking more on it, and the Li seems more profound; just as we look up at the Sun, the closer we look, our eyes grow fainter. Therefore, it is difficult to answer.”

After this dialogue, Ruggieri moved to the story of Augustine and the Trinity in the same paragraph:

I have also heard of an ancient Saint. He hoped to explore the mystery of the Lord, pondering by night and by day. One day, he walked along the seashore and met a little child running with a hopper. He asked, “Where are you going?” The child answered, “I am emptying the sea into this hopper.” He smiled, “Trying to fill the pit with all the water in the sea – it is impossible to do that!” The child responded, “You know that it would not be possible to empty the sea into this hopper, so why do you attempt to pour the mystery of the Lord into your mortal mind? Isn't that absurd?” The child then vanished, leaving the Saint astonished. He therefore knew that the child was an angel. From this story, we know that the mystery of the Lord cannot be expounded in human words.Footnote 35

This text, shown in Figure 1, adopting the Confucian writing style of the dialogue between the emperor and the minister, attempts to connect the doctrine of the Christian God with the Neo-Confucian theory of Li 理. It is not difficult to detect that Ruggieri used some terms from Cheng-Zhu Lixue 程朱理學 (Cheng-Zhu School), which were often used to describe the metaphysical features of Taiji 太極 (the Supreme Utmost), such as “no figure nor sound” (wuxing wusheng 無形無聲) and “no beginnings nor endings” (wushi wuzhong 無始無終), to refer to the Christian Concept of the Trinity. Ruggieri also used the Confucian concept of Tianshen 天神 (Heavenly gods) to refer to “angels.” In relation to this picture, Ruggieri outlined the figure of “Augustine” as a Confucian saint Shengren 聖人 in his text.Footnote 36 This contextual comparison between the Confucian and Christian concepts of God shows a “Confucian–Christian synthesis” in employing Confucian terms to refer to the Christian faith. This method of synthesis was also echoed by Ruggieri's companion, Matteo Ricci, in his Catechismus Sinicus.Footnote 37

Figure 1. A Ming Dynasty script of Michele Ruggieri's Confucian account of the Christian God and “an ancient saint” (Augustine). In the collection of the Nanjing Union Theological Seminary (image by the author).

In line with the “synthesis” method, the accommodation of terms becomes clearer in later translations of the Qing Manchu dynasty. In 1884, William Muirhead (1822–1900) translated ten chapters of Augustine's Confessions and published them under a Chinese title Gusheng renzui 古聖任罪.Footnote 38 This is regarded as the first Chinese translation of Augustine's Confessiones, even though it is an abridged version with only 12,000 characters. An obvious feature of this edition is that Muirhead adopted the Chinese calendar and Confucian formulations such as “ancestors” (sheng jiao liezu 聖教列祖, referring to the Church Fathers), “upright inside and elegantly outside” (chengzhong er xingwai 誠中而形外, referring to virtuous Confucians in the “Zhongyong 中庸,” The Doctrine of the Mean) in addressing Augustine, as stated in his prologue:

I address an ancient Western saint named Augustine, who was born in the twentieth year of the Eastern Jin emperor Mu (Dong Jin Mudi 東晋穆帝), and was prominent as the most brilliant saint among the ancestors (shengjiao liezu 聖教列祖) in Algeria. While reading the classics during his youth, he indulged in lusts and passions. When an adult, he was touched by the Holy Spirit and received instruction from a tutor. Thus he repented and converted himself to the Heavenly truth … In the tenth year of Emperor Wen (Wendi shinian 文帝十年), rebellions arose in the Empire. He was exhausted by his ministries and passed away at age seventy-six … I have translated his book Confessiones, since the author [Augustine] held himself upright inside and elegantly outside (chengzhong er xingwai 誠中而形外) …Footnote 39

Muirhead's strategy of accommodating Confucian terms offered a useful model for his Missionary Society companions such as Joseph Edkins (1823–1905), Alexander Williamson (1829–1890), and the American Methodist Young John Allen (1836–1907). Allen published a compilation entitled “Augustine” at the end of 1895. This abridged version was collected in his series of Zili mingzheng 自曆明證 (Conversions), which addressed how some “pagan” Christians had converted from other religions to the Trinitarian faith.Footnote 40 An obvious feature of Allen's translation is that he addresses the issue of how Augustine was set free from the bondage of pagan worship and converted to Christian belief. He refers to Buddhism as an idolatrous religion and adapted the case of Augustine to persuade some Buddhist believers to convert to Christianity. Allan's translation incorporates a contextualized theology to interpret the Roman Empire as having serious problems with Buddhism.Footnote 41 It is therefore a vivid case of Allen following Ricci's missionary strategy of allying with Confucianism against Buddhism, in the mode of “Confucian–Christian synthesis,” to explore the balance of Confucian orthodoxy and Christian-Maitreyan beliefs.Footnote 42 While one of the targets of the conversion would pertain to Chinese Buddhists, the interreligious details of the faith which caused conflicts between Buddhism and Augustinian theology are beyond the scope of this study.Footnote 43

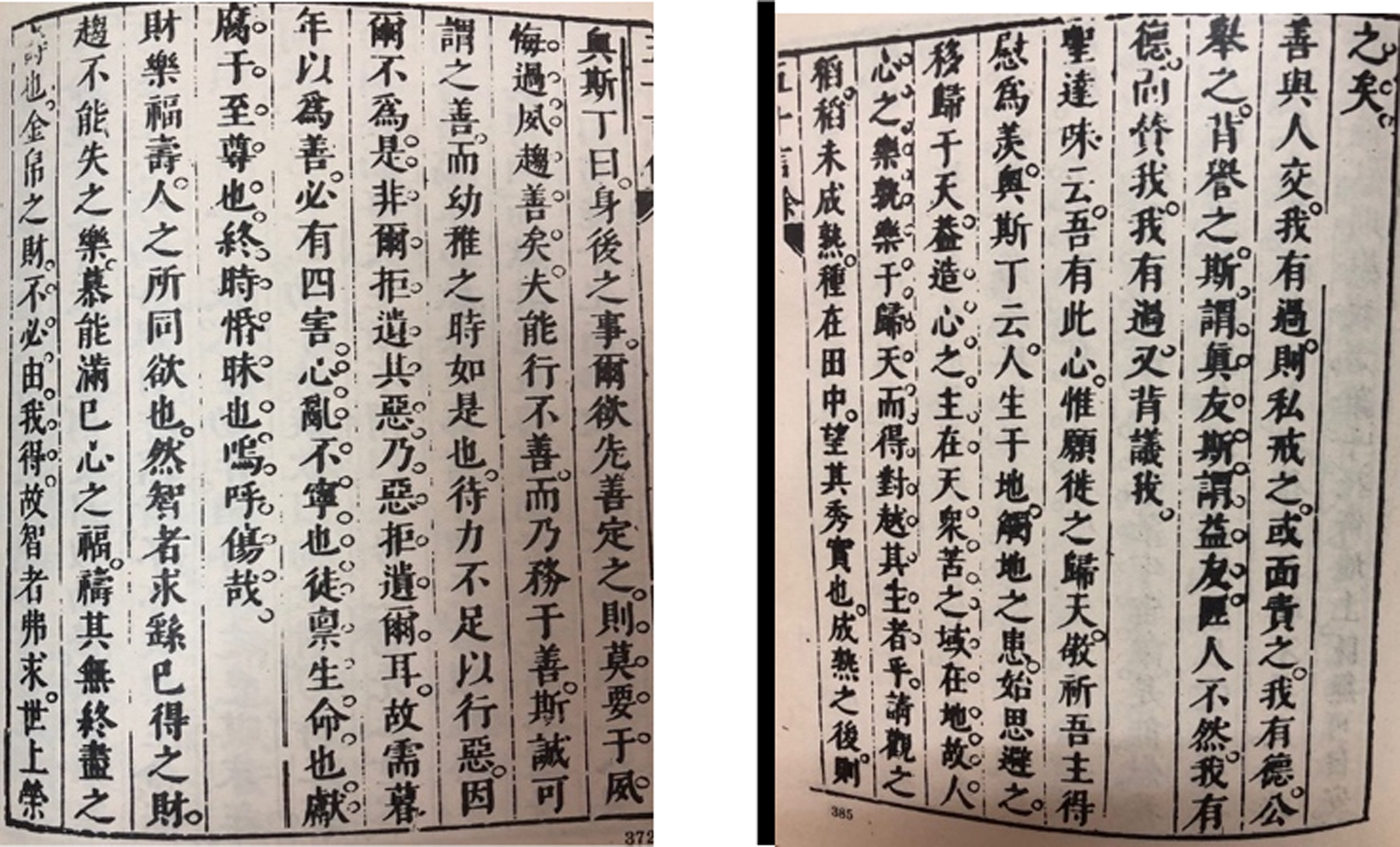

The “Confucian-Christian synthesis,” for the Jesuit missionaries, did not mean the abandonment of the orthodox Christian faith when employing Confucian terms and concepts. On the contrary, the purpose of adopting the case of Augustine was to propagate the core values of the Christian faith with no alterations. In other words, the Jesuit missionaries had to learn Chinese and conform to the indigenous context in ways consonant with Christianity, so as to be able to proclaim the Maitreyan faith as an insider. In a manuscript written in the Ming dynasty Wushi yan yu 五十言餘 (Fifty Proverbs and the Remnants, 1645), I found some paragraphs relating to Augustine's theory of sin and the two cities.Footnote 44 It was formulated by Giulio Aleni (Airulue 艾儒略, 1582–1649) in a Confucian writing style, as shown in the documents in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The Ming dynasty manuscript in the collections of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana and the Nanjing Union Theological Seminary (image by the author).

In the first section of the manuscript shown in these documents, Aleni introduced the model of Augustine, emphasizing the significance of conversion to the congregations:

Augustine states that it would be better that you choose goodness before the things [final judgements] after this life. It is not right to convert late to confess and follow goodness. If your behavior was often evil, but trying your best to be good, it is indeed good itself. This often happens in one's early years. When you are not able to do evil, it is not because that you are good or have left evil behind, but the evil left you. Therefore, if you convert late, only when you are old, it will lead to four bad things: perturbation of the soul, wasting the time of life, leaving a corrupted soul to the Supreme Good [God], and eternal fatuity. This is a great pity! (wuhu shang zai 嗚呼傷哉).Footnote 45

After explaining the urgency of conversion, Aleni raises the concepts of good and evil in Augustine's account of the two cities, as shown in the second section of the manuscript above:

Augustine states that human beings, born in the terrestrial city, were often perturbed by worldly matters. They started to set themselves free from these issues and moved toward the Heavenly city. While our Lord, who created and renewed the soul, lives in Heaven, all the sufferings are in this world. Thus the joy of the soul, isn't it to go to Heaven and participate in the Lord?… The earthly souls have been corrupted and polluted. They devoted themselves to worldly matters rather than the higher goodness, why?… This world is not the home of eternal happiness, but instead is filled with fear, or distress, or temptation. Living in this life, the soul is not able to be consoled even for a moment … For a person, being evil, I am so delighted that he could convert to the good, however, he is still tempted by evil. If a person is good, although this is praiseworthy, I still worry he could turn back to evil again … Entrusting hope to his earthly city, he could never be in real security.Footnote 46

How to set oneself free from the perturbation of the soul devoted to worldly matters, and moving from egoistic desires (especially the passion for domination) to the love of God is the theme of Augustine's late magnum opus, The City of God, which he summarizes as the encounter with two cities, amore sui and amore Dei. Aleni's clarification is in line with this theme, but involves some terminology from the Four Books (sishu 四書), such as the idioms “One thrives and survives under suffering and hardship, and withers if left over-protected and contented with the current situation” (shengyu youhuan siyu anle 生於憂患死於安樂) from Mencius. However, Giulio Aleni's intention is not to be committed to Confucian values. He points out that due to “fears” (kongju 恐懼), “sufferings” (youhuan 憂患), and “temptations” (youhuo 誘惑), the souls of human beings in this corrupted world cannot attain the impassible good state (impassibilitas) once and for all. Thus, orienting the mind toward the heavenly city rather than the terrestrial world of sufferings (zhongku zhi yu 衆苦之域) is what the ancient saints or philosophers pursued. Portraying Augustine's theory of the two cities in this Confucian manner, Giulio Aleni stresses the urgency of baptism; he expects the congregations to convert to Christian values of goodness and the promised city of Heaven as soon as possible. It is thus not difficult to see that Aleni employed the method of the “Confucian-Christian synthesis” in his missiological practice, making a skillful connection with Confucian terminology.

On the basis of the above analysis of these documents, we can observe that a “Confucian–Christian synthesis” played an important role in the early Jesuit translations, which promotes the accommodation of Christian values in the Chinese religious context. This “synthesis” is not an eclectic position combining the coinciding views of Confucian and Christian worldly values, but instead it stands by the very nature of Catholic dogmatics in adopting a convenient way of preaching.Footnote 47 As was the case of introducing the Roman Empire as a place of Pagan “Buddhist” worship, which is not a misrepresentation, but rather a wise strategy of propagating the gospel to a greater number of Chinese people, encouraging them to follow the example of Augustine. In what follows, I shall go a step further to ask why Augustine was chosen by the Jesuits in dealing with the conflict of Confucian and Christian values in their missionary practice.

The Role of Augustine in the Encounter of Confucian-Christian Values

Augustine being taken as a spokesman by the early Jesuits was not confined to the fact that he was one of the supreme Latin writers of Western Christianity and one of the most influential figures in the history of the Catholic church,Footnote 48 but also because he experienced a conversion and provided a model of how to deal with heresies and pagan (Stoic philosophical) doctrines in his life. His experience is thus of particular importance for missionary work in China. Taking his refutation of the Stoic and the Platonic philosophers as an example, let us first look at Augustine's consideration of the conflicts between philosophical and theological values.

Before his conversion in Milan, Augustine was influenced by various philosophical traditions, and two of them, Stoicism and Neoplatonism,Footnote 49 became the main sources in shaping his understanding of the role of intellectual control in moral deeds and virtue. However, after he became Bishop of Hippo, Augustine became gradually aware of the limitation of the functions of the will and reason, attempting to review those issues from a theological perspective. In other words, Augustine followed his predecessors’ philosophical framework in his early years, but he deviated from their position by offering a theological anthropology developed from a different perspective by reinterpreting the terminology and doctrines of his predecessors accordingly. Two pivotal theological concepts, original sin and grace, allowed his worldview to include various levels. (1) At the mundane worldly level, Augustine espouses a pessimistic orientation that is associated with the doctrine of original sin and he criticizes philosophers who “overrate” their personal powers and virtues, living in a state of “pride” (superbia) and egocentricity. Augustine argues that in the fallen condition, there is a weakening and distortion of human will, love, and rational power. That condition also reveals a perverse tendency (pondus).Footnote 50 (2) Augustine believes that the model of Christ established a righteous and undeflected value system that offers new criteria for evaluating human conduct. The philosophers themselves cannot become aware of their moral defects (for example, their arrogance) and depraved nature without an awareness of the uncontaminated values in Christ. (3) At the eschatological level, Augustine believes that two cities of men will be differentiated. One will be saved by the grace of Christ and enter the City of God with purified values and recovered cognitive abilities, receiving the gifts of grace and participating in God in eternal rejoicing. The other (without redemption) will remain in the sinful state together with the Devil and receive eternal punishment from God.Footnote 51

Therefore, in comparison to the philosophical framework, it is evident that Augustine displays a pessimistic view toward mundane life, and he believes that an external power is required to change a depraved nature into a higher state. Furthermore, Augustine has complete confidence in supranatural grace, and concludes that divine love will generously bestow gifts not limited to restoring the distorted human condition. These supranatural gifts are certainly limited to the elect, with the majority remaining under the righteous wrath of God toward our fallen humanity. Thus, the theoretical foundation for his worldview is formed by the assumption of a perverted human pattern of living and a faith in an equitable divine value system as well as eschatological fulfillment.

This transitional background makes Augustine one of the most suitable candidates for dealing with the conflicts between Christian and Confucian values. Like the Stoics and the Platonists, Confucianism also endorses a correct, intellectual control that promotes moral acts and virtues. However, Confucianism does not confess the overwhelming power of original sin as well as the role of grace in the cure of the intellectual functions. The missionary work in China, in an important sense, lies in the conversion from Confucian values to the theological synthetic worldview. Although the metaphysical assumptions in the Stoics and Confucianism are different, neither of them confesses the following points which are crucial in Augustine's theological anthropology (in his refutation of the philosophical framework): (1) the overwhelming power of original sin leads to a condition of misery; (2) humans cannot save themselves by their own powers because their values and thinking are corrupted; (3) the Saviour is not infected by original sin and is a model of true value; (4) in order to redeem the depraved condition, the Saviour voluntarily enters the human reality and participates in human life as a sign of divine love and as a gift of grace; (5) the Saviour has sufficient power to deliver fallen humans from both their suffering and their perverted condition. These five crucial points in Augustine's theological doctrine represent general Christian values, which cannot be found in any Confucian documents. Moreover, these points, together with the theory of the weight of the will and love (pondus voluntatis et amoris), composed the inner structural conflicts between Confucianism and Christianity.

Therefore, the role of Augustine, in this structural conflict between Confucian and Christian values, is how to adapt in order to persuade the common Chinese laity and the scholar-officials to accept the above five dogmatic points and the theological synthetic worldview. Considering Augustine's experience of parting from his earlier philosophical paradigm (following the Stoics and the Platonists) and the change to the soteriological view of his later theology, his conversion, from the perspective of the Jesuits, is a good model for Chinese congregations, as we have seen in the paragraphs by Giulio Aleni (Airulue 艾儒略), who explained the theological view of the corrupted soul and the will in the name of Augustine. Therefore, St. Augustine was considered an additional advantage for propagating the Christian faith by the Catholic theologians, not only because he made an intellectual transition from a secular philosophical paradigm to a theological scheme of values, but because it also follows that his experience of conversion had an immeasurable effect in encouraging pagan believers to convert to the Christian faith.Footnote 52

Concluding Remarks

While Augustine stands out as one of the most influential Church Fathers in the West, China has not been blind to him historically. Rather, Augustine played a significant and fascinating role in the early reception of Christianity in China through its introduction by Jesuit missionaries. Some critics such as Zhou Weichi astutely observe that several paraphrasing errors occurred in the translation of Augustine into the Chinese context, such as the Roman Empire being portrayed as a place of pagan worshippers of “Buddhism.” However, what he does not say is that these inaccuracies reflect the accommodation and indigenization of Augustinian theology in the Chinese religious context. This phenomenon of the transformation of terms is understood by other researchers such as Nicolas Standaert, R. Po-chia Hsia, Audrey Seah, and Sumiko Yamamoto, but they do not explain why and how Augustine was taken as an advantageous symbol in dealing with the conflicts of value in the Confucian–Christian encounter. For the indigenization of Augustinian theology, a strategy of “Confucian–Christian synthesis” was employed by the missionaries. This means that they attempted to reach a balance between assimilation and independence with respect to Augustinian traditions in a foreign religious context. From this perspective, the alleged paraphrasing “misrepresentations” demonstrate a considered writing style, achieved through adopting the terminology of the Chinese native language and an accommodation to the indigenous religious modality.

In the strategy of the Confucian–Christian synthesis, the thesis is not confined to the adaptation of the external aspects such as terms and ceremonies, but involves the deeper connotation of converting faith and values. Instead of considering ancestor worship in the Confucian tradition as illicit, the early Jesuits such as Michele Ruggieri, Matteo Ricci, and their successors refined the Chinese rituals not as idolatrous but as civil phenomena that could be acceptable to the church. This monotheism makes the dialogue between the Confucian worship of heaven (tian) and the Christian faith in God (shangdi) possible. As distinct from Confucianism, Augustine observes the world through the lens of original sin, describing the world as a distorted and miserable reality. In this picture, he introduced a significant concept, the weight of the will and love (pondus voluntatis et amoris), in his dialogue with his predecessors. His values with regard to his theological anthropology consisted of a perverted human living pattern, faith in an equitable divine value system, and eschatological fulfillment, which contributed to the Confucian understanding of the natural order and the promise of the future kingdom. Augustine's theological doctrine attracted much attention from both the elite and commoners, and there was a resulting sharp growth in the number of Christians in Chinese society, from an estimated eighteen persons in the year 1585 to 217,000 at the beginning of the eighteenth century.Footnote 53

To summarize, Augustine was considered an additional advantage in the early propagation of the Catholic faith in China, in which the strategy of the Confucian–Christian synthesis (with a missiological feature) was adopted by the Jesuit missionaries as a potential method for dealing with the issues of the accommodation of terminology as well as the conflicts of faith and values in the indigenization of Christianity in the Chinese context.